1 minute read

Perspective

My Body, My Self

After a series of miscarriages, I lost trust in my body. A compassionate photographer helped me regain it.

By Zoë BRiglEy

On a frosty, winter day, I drive down to Clintonville with my passenger seat piled high with lingerie, stockings, underwear. You’d be forgiven for thinking that I’m on my way to an assignation. But no, this is an appointment with myself and a woman with a camera, and it is to test how far I have come in learning to love my own body. I am about to pose completely nude in front of a stranger.

It has taken many years to come to this moment of reclaiming my body. At the time of this appointment, I am recovering from a miscarriage. I have had four miscarriages in total, and the doctors have never been able to explain why, despite all the tests. It is a great joy to me that out of six pregnancies, my two sons did survive. But still, I have in the past blamed myself for the losses and asked why my body had to fail while others’ succeeded. I have never been a churchgoer, but there were times when I began praying because I was so afraid that my body would let me down again.

My lost pregnancies are not the only time I have felt my body was hijacked. It began as a teenager with body dysmorphia, a condition where a person cannot stop thinking about flaws they perceive in their body, which may be minimal or invisible to other people. I didn’t know it then, but I was suffering from quiet bor-

Zoë Brigley

derline personality disorder, a condition that causes not only body dysmorphia but also extremely low self-esteem, fear of abandonment and mood swings. My experience was different from regular borderline personality disorder, because there were no angry outbursts. Instead, I turned a withering dislike on myself. Looking in the mirror, I believed I was monstrously ugly, although I know now that I was just an average, awkward teenage girl.

The condition often causes people to go to great lengths to prevent abandonment or separation. At age 14, I fell under the spell of an older man who would exploit that tendency. The abusive behavior started only when I was completely dependent on him, and it meant having sex whether I wanted to or not. For a long time, because of my disorder, I couldn’t leave him, no matter what he did. Despite the coercion and violence, I thought I would die if he left me, so I sacrificed my body, and it was mine no longer.

But I did escape, with the support of family and friends. I reclaimed my body. I fell in love and got married and was happier than I’d ever been. When I first moved to America from the UK, I was pregnant, and everything was in place to create the beautiful life I dreamed of. Then, in the second trimester, I had a miscarriage. Shattered, I had to rebuild myself with only my partner to lean on, no family or friends in the new town. And the miscarriages kept coming.

During those high-risk pregnancies, my body was not my own: poked, prodded, probed and tested. These were the days of bed rest and fetal movement checks, of trying to do everything right, of regulating everything that went near my body. I got through it by thinking of the babies. There was nothing I would not have done for them, and that motherlove made me strong. I thought I could weather anything, but when my sixth pregnancy ended with a second trimester miscarriage, the old grief returned. I felt like I was being haunted by what had happened to me as a teenager. All these feelings suddenly appeared again. Had my body failed me? Was it marked forever by what had happened to me? Would I never escape it?

But I tried to be brave and asked myself: If I couldn’t have the child I had wanted, what new story could I write for my body and my life? The first step was to remember that my body was not failing me; in fact, it was sustaining me every day. Whatever it had suffered, and despite the miscarriages, my body was doing its best. I started swimming, the water bringing me physical sensuousness. I took up aerial hoop classes, amazed at what stunts I could teach my body to do, how strong it became with practice. And then, at just the right moment, Kate Sweeney came into my life.

After following Kate’s Instagram feed, I found myself looking out for her nude or semi-clad photographs of women of all shapes, colors and sizes. I noticed them hanging in Virtue Salon, the vegan hairdresser where I have my hair cut. Kate minimally edits them, and though she draws on fine art—Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus” or Goya’s “La Maja Desnuda”—Kate’s women are more defiant. Their bodies are fleshy, pendulous, freckled, cheeky, but not contorted for the male gaze—not tense, not self-conscious. Kate’s photographs rely on a trust that the male gaze—assessing, measuring, judging—cannot provide. “I just thought, these women are so beautiful,” Kate tells me during the shoot, “and I real-

ized that if I found beauty in all these different women, I should start to extend that same kindness to myself.”

Like me, Kate suffered as a teenager from body dysmorphia, in her case linked to an eating disorder. “It wasn’t even that I felt like my body was bad,” Kate tells me later. “I just wanted to disappear. We have to change the message that the more attractive you are, the more valued you are.” Kate is Columbus-born and -raised, though she spent some years in New York. When she found herself in a toxic relationship with a man she describes as “a gaslighter,” she returned to Columbus and began taking photographs of women in the local community. Like a magic antivenom, Kate’s photographs take us on the journey that healed her: In seeing how beautiful real women are, we also come to terms with ourselves.

On the day of the shoot, I am determined to accept my body, even when naked. I am terrified, but Kate welcomes me into her cozy house and leads me to the studio with her beautiful rolls of colored paper backdrops. She asks me what music I would like to listen to and she shows me her camera, which is purposefully small and unintimidating.

We try lots of shots in different dresses and lingerie. She helps me to overcome my shyness by talking me through poses. And none of it feels sexualizing, because it is not the male gaze looking at me, but the female gaze, and so I don’t worry about what I look like—it feels like acceptance rather than having to perform. “I’m so grateful and honored that so many women trust me,” says Kate. “I wish that all women would document their bodies. Because aging is a privilege, and to see how the body changes is really cool.”

But I am a 38-year-old and have had two children, and when the time comes to take off all my clothes, I am nervous. And why is it so hard? Why does it feel frightening to be under someone else’s eye? A minute before, in my underwear, I was completely comfortable. Why, I ask myself, is this suddenly so scary? I lie down in front of the camera, and it feels painful in a good way, like massaging a sore place. I can’t say that I feel ashamed or proud—just vulnerable, and I realize that I am still looking to other people for approval, when I need to find that approval within myself.

The final part of the process only happens some weeks later, when the photographs arrive. I look at the nude shots and laugh that in some pictures I do look absolutely terrified. But I take this as a sign of bravery—that I did something hard despite the fact that it scared me. In others, too, I look calm and hopeful, at one with myself, and I take that as a victory, because that is where I aim to be. I look at my body completely naked, and I quite like myself. I remember what Kate said to me before I left: “You see? The body can be art.”

I realize now that before the shoot I would hardly ever actually look at my own body, probably because I did not feel pride or joy in it. I look at it now with compassion. I take care of it. I pay attention to it. I dress it carefully. To some extent, I have learned to love it, and when I walk out the front door, I feel happier in my own skin.

If I—who believed myself to be a monster—can love my body, then probably you can too. What if we were to say that our bodies are beautiful just as they are? What if we embraced our bodies as unique? What if we refused to be controlled by images that are an illusion of digital enhancement, that were never achievable in real life? What if we too did the work of Kate’s magic photographs and noticed the beauty of real bodies around us? Could we perhaps glimpse the power and beauty in ourselves?

It’s a mindset that could change our lives completely, if we could just say: This is my body, and it is amazing. ◆

2

3

Cookie SHeet

This city is awash in great cookies, with more being dreamed up every day. We gathered together some of our favorites from area retail bakeries, onlineonly bakeries and one nonprofit kitchen.

1 Vegan ginger-molasses cookies from

Dough Mama

2 The gluten-free Monster cookie and

Oatmeal Cream Clouds from Bake

Me Happy

3 Snickerdoodle and peanut butter cookies from Sassafras Bakery 4 A selection of cookies from Freedom a la Cart’s annual Cause Cookie campaign (for every $25 donated to

Freedom a la Cart, you receive a box of a dozen holiday cookies; donations support survivors of human trafficking) 5 Almond cookies from Belle’s Bread 6 A variety of Lion Cub’s Cookies 7 Italian rainbow cookies from Amy’s

Rainbow Cookies 5

2

4

3 4 4

4

4

6

Year of the

Baker

People across the U.s. took refuge in baking this year, filling their kitchens with the smell of sourdough breads, French pastries and other doughy indulgences. We talked to Central ohio retail bakers and home bakers alike about why they bake, about technique and about baking through a pandemic.

Visit columbusmonthly.com for a web extra on Lion Cub’s Cookies.

6

6 7

7

Rolling with the Times

How Resch’s Bakery has endured for more than a century

By Dave Ghose

Even more than usual, Resch’s Bakery is a study in the fine art of balancing change and tradition. Customers still pass underneath its familiar neon sign when they enter the East Side landmark—but now they also pass by new window placards about social distancing, online ordering and racial justice. Employees still prepare jelly rolls, birthday cakes, apple fritters and other baked goodies in the same meticulous German way— but now they do it while wearing masks and spaced 6 feet apart.

Frank X. Resch, the fifth generation of his family to run the bakery, calls the coronavirus pandemic the biggest challenge he’s faced since he took over the business after his father’s death in 2010. Yet Resch is confident he can make it through this crisis. After all, his bakery has survived two world wars, the Great Depression, urban flight, changing culinary tastes and even a previous global health catastrophe. The deadly influenza pandemic of 1918 occurred six years after two German immigrants, Frank A. Resch and his nephew Wilhelm Resch (Frank X. Resch’s great-grandfather), opened the first Resch’s on the South Side of Columbus. In 1960, Frank X. Resch’s father, Frank J. Resch, opened the current bakery at 4061 E. Livingston Ave., about 4 and a half miles east of the much smaller original location, which closed in the early 1990s.

Family lore doesn’t include anything on how the bakery overcame that earlier devastating outbreak. But Frank X. Resch does have a theory on what’s responsible for his business’ remarkable longevity: It’s become a family tradition to many of its customers. “They were brought here by their parents or their grandparents, and I think it’s become a comfort for them,” he says. “I kind of attribute our business to that. They grew up with us.”

To keep those longtime customers happy, the bakery doesn’t change things willynilly. It started as a small retail operation and remains one today, never jumping into wholesaling. Except during the heyday of Reeb’s Restaurant on the South Side of Columbus in the mid-20th century, Resch’s delicacies have never been available anywhere else besides its bakeries. Frank X. Resch started helping out in the business when he was 7 years old, first sweeping the floor and cleaning pans and then learning how to bake from his father and a German baker. Now, the current owner of the business and his most trusted managers—many of whom have worked for the business for decades—teach those same precise baking techniques to new employees, who often start at the bottom just like Resch did and then work their way up to bakers, cake decorators and other more critical jobs.

Yet Resch’s hasn’t exactly been standing pat. It’s doubtful the business would still be around if it hadn’t moved to the larger Livingston Avenue location six decades ago. Its most popular items have also shifted, from bread in the early days then to cakes and now doughnuts. “You listen to the customers, and they kind of tell you the way to go,” Resch says.

In late October, Resch stands in the bakery kitchen. It’s just before 8 a.m. on a Saturday, typically the busiest day of the week, and his team is hard at work preparing for the rush. The Buckeyes start their pandemic-delayed football season on this day, which means Resch expects to see more customers in the early morning before the game’s noon kickoff. Dreary weather also might increase sales. “When it’s hot and muggy, nobody wants to eat,” Resch says.

Opposite page, a photo of the original bakery; This page, clockwise from top, Nya Washington fills a box of doughnuts for a customer during a busy Saturday morning; a worker makes chocolate dipped doughnuts; freshly baked cinnamon rolls

Resch’s Bakery 4061 E. Livingston Ave., East Side, 614-237-7421

Resch watches an employee put the finishing touches on a tray of sugar yeast doughnuts, a more breadlike, hexagonshaped variety. “I’ll take those out, Matthew,” he tells the baker, before shuttling the tray to the front of the store. On a busy day, Resch joins the rest of the team in food preparation, helping out where he can.

Gary Diewald, the production manager for Resch’s, usually spends his Saturdays in the front of the store, making sure the shelves are stocked with cookies, cakes and other goodies. He also limits the number of customers in the store at a time and makes sure social distancing is maintained. “We’re trying to get people in and out as easily as possible,” says Diewald, who’s worked for Resch’s for 46 years.

When they enter the bakery, most customers grab a ticket from a dispensing machine and wait for their number to be called. But a handful instead pick up orders directly from a metal shelf next to the entrance and in front of a mural of the Black Forest region of Germany, where the Resch family comes from. This shelf is stocked with prepaid online orders, a new service. “We’ve had that for six weeks,” Diewald says. “It’s getting busier and busier.”

On Saturdays, Diewald sees a lot of familiar faces (though they’re masked these days) and gets to talk to longtime customers. And there are plenty on this day. A middle-aged man, standing in line outside the store, says he’s been coming to Resch’s since his childhood, when his mom would buy birthday cakes for him here. A white-haired woman, waiting inside the store, says she got her wedding cake from the original Resch’s on the South Side.

Cecil Jenkins has been a regular at Resch’s for 40 years, starting when his family lived in the Driving Park neighborhood of Columbus. Now, Jenkins lives in Pickerington, but he still stops by Resch’s at least once a week, usually on Saturdays, when the bakery offers special doughnut flavors, such as devil’s food and red velvet. “It’s worth the drive,” he says.

Eight Bakers Without Storefronts

Drawing inspiration from trips abroad, family histories and childhood nostalgia, these entrepreneurs inspire us with their baked creations and stories of determination.

By Erin Edwards and Emma Frankart Henterly

OhiO Pies

Emily Irvine wanted to work in food because she loved eating it. She remembers the bite that sparked the love affair. “It was a crème brûlée—the cracking of the top and the shards of caramelized sugar and the creamy cool vanilla custard,” recalls the Bexley native.

Irvine’s first job in food was at the Bexley Natural Market. “From there, I went onto farming. I worked on small organic farms for about 10 years,” she says. Despite no baking experience, she began working at local bakeries during winter breaks. With practice, she grew her confidence as a baker. “I had a business card, and I was making pies at home, but I don’t think I ever intended to do anything with it,” she says. In 2017, she launched Ohio Pies from her home full time.

Irvine is passionate about sourcing ingredients from Ohio farms for her pies, which range from maple pecan to blueberry to banana cream. She also uses Ohio grassfed butter in her flaky crust—the key to which is to “start with really cold butter in larger chunks than you would think.”

Why pie? Irvine says that none of the pies she tried locally stood up to the ones her grandparents used to make. “You can’t really compete with nostalgia,” she says.

Plus, she loves the challenge. “It is hard to make a good pie. There’s a lot more involved, because you have to get the crust right and the filling right,” she says. “I feel like I could keep doing this the rest of my life and always be learning new stuff and always keep getting better.”

Look for Ohio Pies every Tuesday at Bexley Natural Market (508 N. Cassady Ave.) or place your order at ohiopies.com.

Calvin Kim and his wife, Sasha, dove into the world of home bakers after discovering that Columbus lacked a sweet treat readily available in his home country of South Korea. That’s where the pair met, while Sasha was living there as an expat.

“While we were dating and living in South Korea, we tried some macarons in Seoul and really enjoyed them,” Calvin says. “But after moving to Columbus in 2014, we couldn’t find anything like the ones we tried [there].”

They went to Pistacia Vera, of course, and other local bakeries. But nothing matched the crispymeets-chewy shell texture and the abundant-but-not-too-sweet filling of Korean macarons.

Calvin started to experiment. “After lots of trial and error, I made a pretty decent salted caramel macaron recipe of my own,” he says. “Friends and family loved them and encouraged me to sell them. … I was more than confident that this business would go well.” In 2018, Calvin quit his full-time job as art director at an ad agency, and Mjomii was born.

The name—which is pronounced “meeyo-me” and means “subtle and delicious flavor” in Korean, Calvin says—is a blend of ideas from both Calvin and Sasha, who is herself half Korean and has a graduate degree in speech language pathology from Ohio State University. “The ‘J’ is the symbol for the ‘Y’ in the phonetic alphabet,” Sasha says.

Mjomii’s flavors have a decidedly Asian influence; think taro cream, walnut and red bean, black sesame and even soy—though you’ll also find flavors like chocolate orange, raspberry and salted caramel, the flavor that started it all. When asked whether Mjomii offers other treats, Calvin cryptically replies, “Not yet.”

Order online for pickup or mail delivery at mjomii.square.site, or find the macarons at the German Village Makers Market on Dec. 6.

Mjomii owners Sasha and Calvin Kim

Matija Breads

Matt Swint doesn’t mince words about how COVID-19 affected his wholesale baking business: “I got slaughtered.” Beloved by local chefs for its focaccia and ciabatta, Matija Breads went from 20 active customers a month to four when Ohio’s dine-in ban took effect.

Matija (named for Swint’s Italian grandfather) has survived in part because of its size. “If I had been a larger [business] and lost all my customers at once, I don’t know what I would have done. [Being small] makes you extremely nimble,” Swint says.

The pandemic’s silver lining was that it allowed Swint to take a breath and look critically at his business, which runs out of a commissary kitchen. Since its inception, Matija had remained hyper-focused on a small menu of Italian breads. “I realized a lot of people want brioche and … seeded rolls. It’s OK to be the guy that makes rolls, which I didn’t want to be. I wanted to be Dan the Baker [see Page 40]. I wanted to be the guy that makes all the pretty loaves,” he says. Swint still makes beautiful breads, but he has expanded his offerings to better cater to his clients’ needs. (He now makes rolls.)

In recent months, Matija has staged a comeback. “I picked up Ray Ray’s [Hog Pit]. To be honest, that saved the company,” Swint says. He also signed up three of the city’s newest restaurants: Cleaver, Rye River Social and Emmett’s Café.

Swint is sure about one thing: There is plenty of room in Columbus for other bakers like him. “You can’t have enough [bread] bakers in this city,” he says. “The more the merrier. … We need to have something that combats all the doughnuts and pie places.”

Look for Matija Breads on local menus at Katalina’s, Sassafras Bakery, Rye River Social and Emmett’s Café, among others.

Three BiTes BaKery

A professional baker for

six years, Isabella Bonello worked at Pistacia Vera and Fox in the Snow Café before launching her own cottage bakery, Three Bites, a year and a half ago as a side business.

When the pandemic began, Bonello was working in the corporate baking department at L Brands. When the company no longer needed birthday cakes and pastries for meetings, Bonello’s department was eliminated. In August, Three Bites became her full-time focus. “I think the one thing that would set Three Bites apart is it’s not just a hobby; it’s what I’ve spent years developing,” she says, explaining that her goal is to open a retail bakery someday.

Through her website and local makers markets, Bonello sells pastry assortment boxes with treasures as far ranging as pan de coco, Chinese five spice shortbread, brown

butter rum cake and jalapeño cornbread. She also sells custom cakes. “I always include shortbread cookies of some flavor in every variety box I do, and it is consistently some people’s favorites. I also love doing savory stuff. Pastry doesn’t always have to be sweet,” she says. Bonello takes baking inspiration primarily from her family’s background, which is Italian and Filipino. Because of those influences, her pastries aren’t too sweet, featuring a lot of nuts and fruits, and not too big.

“Whenever you go to Europe, a lot of the desserts, a lot of their pastries, they’re not too big. I feel like that’s something, at least in Columbus, that’s lacking. Everything is kind of the size of your head,” she says. “I really believe that you’re allowed to have sugar, you’re allowed to have butter. It’s just you only literally need like three bites.”

To order assorted pastry boxes or custom cakes, visit threebitesbakery.com.

Pastries from Three Bites Bakery; inset, Isabella Bonello

Kennedy’s KaKes

Baking is a skill handed down to Adrian Jones by her grandmother and mother. Using their recipes as a foundation, Jones started Kennedy’s Kakes (named after her own daughter, Kennedy) in 2009 as a part-time business from her home kitchen.

“I just took a leap of faith and started selling the things that people always asked me for, and it was my pound cake that my mom made and sweet potato pie,” says the baker and cake artist. “And it evolved into what I’m doing now. I would’ve never thought wedding cakes. It was just traditional desserts in the beginning, but my own business is something I’ve always wanted to have.”

Pâtisserie LaLLier

A Luck Bros’ latte with Pâtisserie Lallier baked goods; inset, Michelle Kozak

Mention French pastry in Columbus and Michelle Kozak’s name is often one of the first to come up. Her baking business, Pâtisserie Lallier, is treasured by those craving fresh pain au chocolat, fruit tarts, madeleines and even meticulously made confections that fill Advent calendars during the holidays.

After immersing herself in a monthlong pastry course at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris in 2009 (“for fun”), Kozak launched a small-scale cottage bakery from her Grandview home. In 2010, she started selling her pastries at Clintonville’s Global Gallery Coffee Shop. Two years later, after taking intermediate and advanced pastry courses, she traded her job in banking for the more solitary, creative life of a full-time baker.

“I think people are always surprised when they come over to see how small it is and how much I’m able to produce from it,” Kozak says about her galley-style kitchen, which affords her only a 4-footwide workspace. (She uses a table and a baker’s rack in the dining room as well.)

Before 2020, Kozak had never had an online marketplace. When the COVID-19 outbreak began, Kozak ceased selling her pastries at the farmers markets she had attended for years and instead shifted to online orders and porch deliveries in Clintonville, Upper Arlington and Grandview as well as distanced drop-offs at Global Gallery. She says her fans—some of whom date back to her early days at the Clintonville Farmers Market—have followed.

To place an order with Pâtisserie Lallier, visit patisserielallier.com.

About six years ago, Jones went full-time, and a year ago, she moved Kennedy’s Kakes into a commercial kitchen in the YWCA Downtown. “Even though I was making a profit, it never seemed outrageous enough to have my own kitchen or my own building. I was just too scared to do that,” she says. “The opportunity came to me, and I really felt like I just closed my eyes and stepped out. It’s been amazing.” This year, Jones was primed to have one of her busiest years yet, with 26 weddings on the calendar. She’s ended up with less than half that number because of the pandemic. It was a wakeup call.

Now, you don’t have to be a bride or groom to feel like one. Jones offers tasting boxes to anyone, filled with various cake flavors as well as special items like macarons and cookies.

Visit kkakes.com to order custom celebratory cakes, pound cakes, cupcakes and more.

Kennedy Goolsby, left, with her mother, Adrian Jones

Jan Kish-La Petite FLeur MoonFLower BaKery

For 40 years, Worthington baker Jan Kish has been delighting Central Ohio with her whimsical, extravagant wedding and celebration cakes. But there’s more to Jan Kish-La Petite Fleur than meets the eye.

“I have a degree in English from Oxford in England, and I wanted to teach,” she says. But while in the U.K., the quaint tea shops caught her eye.

After Oxford, Kish studied at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris and England and L’Académie de Cuisine in Maryland but ended up working as a surgical assistant at Ohio State University. During the decade she spent at OSU, she launched a catering business, La Petite Gourmet, on the side. She later opened a restaurant/catering business in Upper Arlington called La Petite Fleur.

“I would come home [from work] and do catering. It was exhausting,” she says.

By 1990, Kish decided she’d had enough of the retail scene: the guesswork of trying make just the right amount of product, the staffing demands. “The thing that I really wanted to do, which was the cakes, I was getting so far away from,” she says. Instead of leaving the industry, Kish went back to being a home-based baker.

Today, about 85 percent of the cakes she creates are for weddings. She’s also created confections for clients ranging from Oprah Winfrey to President Bill Clinton; among her favorites, she says, is a stunning creation for John Glenn’s 95th birthday in 2016. It featured a globe with a moving shuttle tracing the path of his orbit and a firework designating his launch point from Cape Canaveral.

For Kish, baking is about “looking at cake as an art form—a good, edible art form,” she says. “You eat with your eyes first. … But if the taste doesn’t follow up, it’s a huge disappointment. You’ve got to make sure one equals the other.”

Order a custom cake or cupcakes by visiting jankish.com. For Dublin resident Pearl Althoff, baking just fits into her lifestyle. “Ever since I can remember, I’ve been in the kitchen helping my mom, helping my grandma,” she says. “It’s always been something that’s brought me joy.”

So it’s probably no surprise that when she transitioned from fifth-grade teacher to stay-at-home mom in 2017, she turned to baking as a creative outlet. Around the same time, Althoff—a 10-year vegetarian at that point—became vegan.

After talking to a vegan friend and watching documentaries like “What the Health” and “Cowspiracy: The Sustainability Secret,” she decided to take the plunge. “Those [films] really just opened my eyes to a lot of the conditions that the animals are in, and also the workers who work in farms and the slaughterhouses,” she says. “I really wanted to align my actions with what I felt was important.”

To that end, baking became something of a mission. “I really wanted to bring awareness to how good vegan food can be—especially baking,” she says.

It wasn’t until after Althoff’s husband, Rick, surprised her last year by building a website for her fledgling endeavor that she decided to go all in on the home bakery. She named it Moonflower, after a native bloom in Sanibel, Florida, where she and Rick married.

Unlike many businesses, Moonflower has blossomed during the pandemic. “People kept calling, asking for food,” Althoff says. “It’s been really refreshing to have the support of your community at a time like this.”

Order Moonflower Bakery’s cakes, tarts, pies, cookies and more at moonflowerbakery.com.

Pearl Althoff

Home Sweet Home

Built Pastry’s Devon Morgan shares advice on starting your own cottage bakery.

By Erin Edwards

When Devon Morgan was furloughed in March from her job in restaurant sales, she started baking up a storm—like a lot of people. It came easily to the longtime Columbus pastry chef, whose professional pastry experience includes Eleni-Christina Bakery and Hilton Downtown Columbus.

Then, Morgan took her baking one step further: She launched Built Pastry, a cottage bakery, food photography and consulting business.

For a while, Morgan had been considering the idea of starting a business to help other people open their own bakeries. Selling her own baked goods was an obvious way to spread the word about her consultancy. This year, with just a small mixer and her kitchen’s one oven, Morgan has produced a variety of cookies, quick breads, focaccia, crackers and other goodies for pop-ups and markets like the German Village Makers Market.

Ohio doesn’t keep statistics on how many home bakeries launch every year, but bakers I spoke to in Central Ohio say they’ve noticed an explosion of new businesses, as hobbyists and professional bakers alike have pivoted out of necessity amid the pandemic.

In Ohio, two options exist for baking and selling baked goods from a home kitchen: a cottage bakery and a licensed home bakery. According to the Ohio Department of Agriculture, cottage bakeries may sell items that “do not require refrigeration, such as breads, cookies and fruit pies.” Although a license is not required, cottage bakeries are subject to strict labeling requirements.

Home bakeries, on the other hand, are subject to regulatory oversight and allow for the baking of cheesecakes, custardfilled doughnuts, pumpkin pies and other “potentially hazardous bakery items that need refrigeration.” In addition, licensed home bakeries may not have pets in the home or carpet in the kitchen. They are also subject to inspection.

Thinking of launching a bakery from your own kitchen? Morgan shares some advice. ◆ “You can be a cottage bakery and not do the farmers markets or the pop-ups, but it definitely is a way to have a consistent form of income and also a way to kind of get your name out there,” she says. But first, do your research. Although cottage bakeries in Ohio do not require an operating license, some farmers markets require you to carry insurance. ◆ To sell your baked creations, you must carefully label them. “The very first market that I did, I tried to use Avery labels—which are everywhere—and it was a total disaster,” she says, explaining that the wording would end up crooked

or cut off. She ended up investing in a label printer, which saved her valuable time. “My biggest piece of advice is, find a good label maker.” ◆ Rein in your menu. When she started out baking for pop-ups and markets,

Morgan say she “wanted to bake all the things.” Don’t try to do too much. ◆ “Make sure that you have a vision of how you want to set up your table at farmers markets and that you have enough containers to hold your products,” Morgan says. “I think that it’s so important to visually make people want to come to the table.” ◆ Keep track of your receipts for tax purposes. All of those pans, spatulas and labels can be written off. You can find Built Pastry online at builtpastry.com.

Daniel Riesenberger makes croissants at his Grandview bakery.

Making Croissants with Dan the Baker

People line up every weekend at Daniel Riesenberger’s Grandview-area bakery, Dan the Baker, for artisanal breads and outstanding croissants. Besides the traditional butter croissant, he also makes chocolate croissants, ham and cheese croissants and seasonal varieties like summertime tomato and fontina. Here, Riesenberger explains in his own words his elaborate process and offers a warning to home bakers before they attempt to mimic his methods. “There’s so many more fun things you can do with your life than make croissants at home,” he says. “Go support your local croissant artist, because they are crazy people.” dan-thebaker.com —Brittany Moseley

Making the sourdough is the first thing

I do. I build the sourdough overnight, let it ferment. Once I come in the next morning, I’ve got the first step done. I also have croissant scraps from previous batches. I don’t make my croissants without scraps, because it tastes really good to have the extra fermented dough in there. It adds extra richness. You pull your scraps, then you start your leaven.

When my leaven’s ready, which is the next day for me, I’m ready to mix the dough. Then, I pull the dough out of the mixer and form it into the correct size blocks that are 4 kilos, or a little more. Each block of croissants is a book, and each book makes 45 to 50 croissants. I freeze mine so they don’t ferment before they’re processed. As soon as I’m done with the croissants that night, which is usually five hours or so of freezing time, I put them in my cooler, just to keep the fermentation locked down.

Laminating is the process of incorporating the butter in the dough. Laminating uses a sheeter, which is basically a set of rolling pins that has two conveyor belts on either side of it and a handle in the middle that allows you to crank the thickness down of the rolling pins. It’ll convey the dough back and forth through those rolling pins at a precise thickness and allow you to manipulate the dough and butter into the correct size and dimensions. It’s like 4.2 kilos of dough and a kilo of butter. I like to let the blocks sit in the freezer for about a week. Then, I let them thaw. You send a block through the sheeter to get it to the full-size length, which is about 18 inches by 70 inches. If it’s for butter croissants, cruffins or ham and cheese croissants, I divide the block lengthwise down the middle using a croissant bicycle, a multi-wheeled cutter. I put those two halves on top of each other, which makes it easier to cut two at once. Then, I put all of the triangles in the cooler. Later, I take them out of the cooler, separate them and shape all of them. Once the croissants are shaped, I leave them out overnight.

The next morning, the croissants are doubled or even tripled in size. They get an egg wash. It gives them the sheen that is so customary. A croissant without egg wash is like you’re not wearing clothes. You don’t look right. You can’t step out like that.

They go in the oven for about 20 minutes. I bake mine pretty hot because I want them to spring up well, and I also love the caramelized flavor in the dough. I always go for a darker color on the bake, which I know is sometimes divisive. People are like, isn’t that burnt? I’m like, this is delicious. Caramelization is the flavor.

A World of Baking Brilliance

Exploring six of Central Ohio’s best hidden-gem bakeries

By Nicholas Dekker

We’ve long swooned over macarons from Pistacia Vera, cinnamon rolls at Fox in the Snow, cruffins and sourdoughs from Dan the Baker. Here, we highlight a half-dozen other bakeries that deserve your attention, with delicacies ranging from All-American red velvet cupcakes to Turkish simit.

Belle’S Bread

1168 Kenny Centre Mall, Northwest Side, 614451-7110 Tucked into the Japanese Marketplace at Kenny Centre, French-influenced Belle’s Bread often flies under the radar, but Food & Wine named it one of the best bakeries in the country this year. We think they got it right. The shelves are stocked with beautiful fruit Danishes, textured melon rolls, yeasty doughnuts filled with sweet bean paste and adorable rolls drizzled with Nutella to make kitty faces. What to order: Start with the melon rolls, Danishes and custard cream rolls.

cakeS and more

4969 N. High St., Clintonville, 614-430-8811 Starting as a home bakery and adding a Clintonville storefront in 2011, Cakes and More hides a few surprises up its sleeve. Though specializing in artfully decorated cakes, a visit to its retail shop highlights the “And More” part of the name: brownies, cake pops, cookies, a dense layered confection called Brazilian Whisper and even empanadas. The little pockets, made daily, are stuffed with chicken, cheese, veggies, shrimp and other fillings. What to order: Don’t miss the alfajores—two delicate, buttery cookies with a layer of dulce de leche in between.

J’S SWeet treatS and Wedding cakeS

1540 Parsons Ave., South Side, 614-906-8888 Owner Juana Williams has made a name for herself with intricately decorated wedding cakes (her buttercream frosting earns special accolades). Her brick-walled shop entices guests with more treats like soft chocolate chip cookies, vanilla cakes, banana pudding with homemade whipped cream, pound cakes, brownies, cheesecakes and more “edible art,” as Williams calls it. What to order: Williams’ red velvet cupcakes with cream cheese icing

Salam market & Bakery

5676 Emporium Square, North Side, 614899-0952 You might get distracted by the butcher shop or by the shelves stocked with goods from around the Middle East, but follow your nose to Salam’s back counter for freshly baked goods like pita bread and halal meat pies. The latter often sell out, so arrive early. The warm, golden pockets are filled with a variety of meats and veggies, such as chicken, cheese, lamb kebabs or falafel. What to order: meat pies, in whatever flavors are offered that day

Spicy cup café

1977 E. Dublin-Granville Road, Northwest Side, 614-547-7117 Spicy Cup (formerly Panaderia Guadalupana) is one of the city’s most notable Mexican bakeries. Its glass cases are bursting with beautiful pastries, cakes and savory selections. Guests can pick up a tray, grab a pair of tongs and load up with sugar-dusted churros, colorful cookies, cream-filled doughnuts and turnovers stuffed with guava or pineapple. Compared to their American counterparts, Mexican pastries tend to be lighter and less sweet. What to order: the lightly sweet conchas— an airy, rounded bread noted for its shell-like patterns on top

tulip café (inside Espresso Air) 25 N. State St., Westerville, 216-394-6849 Turkish dishes are hard to come by in Columbus, but Tulip Café is seeking to rectify that. Though Tulip Café doesn’t have its own retail shop, you can find its delicacies regularly at Uptown Westerville’s Espresso Air coffee shop and at local farmers markets. Look for honey-drenched baklava with pistachios or walnuts, Turkish delight, or simit: circular, bagel-like breads crusted with sesame seeds. What to order: the buttery and flaky borek with feta, ricotta and parsley worked into the layers ◆

“H ere’s the story of my family,” Beverly D’Angelo tells me. “I grew up in a household that was based on one thing: love.” It is mid-July, and I am listening to the actress, singer and native Upper Arlingtopassionate. She is fond of saying: “Everything I’ve done is because I’ve loved someone.” She tells me this over the phone, speaking from her Los Angeles home, where the coronavirus lockdown seems to have put her in a reflective mood, eager to talk about nian recount her life. She talks about her her life and loves, personal and professional. I have a list parents—still famous in certain circles of old of probing questions in front of me, but I don’t refer to Columbus: former WBNS executive and all-around media them too much. D’Angelo is something of an open book, bigwig Gene D’Angelo and his wife, Priscilla. “I grew up going to surprising places I might not have asked about. witnessing an amazing love affair,” Beverly says with the At the same time, her excitement about life—who she’s flair for the dramatic that I will come to recognize. known, what she wants to do, and, yes, even where she When you write about the movies as I do, it’s a depressing came from—is contagious. When I ask if she remembers fact of life that stars—even really big ones—rarely live up to some of her haunts back home in Ohio, she exclaims: “The their on-screen personas. The exceptions stand out: When Chef-O-Nette! The Goodie Shop! Are you kidding?” I interviewed him a few years ago, Robert Redford had that In the five decades since D’Angelo left Upper Arlington same charm and sharp perception that we expect from him behind—at the earliest possible opportunity, as she tells on-screen. So did Warren Beatty, who, though he never it—she has fostered an image as a rebel. She blazed her trail actually agreed to an interview with me, exuded a certain as a singer in Canada, appeared in a rock ’n’ roll version shambling, distracted magnetism in a brief phone call. of “Hamlet” on Broadway, starred in five Vacation movies, Beverly D’Angelo, though, is the biggest outlier. If you’ve married (and divorced) an Italian duke, became, at 49, the seen her in her best roles—as a hippie in the musical “Hair” mother to twins fathered by Al Pacino, and took parts in or as Patsy Cline in “Coal Miner’s Daughter” or as Chevy many so-so movies mainly distinguished by her presence. Chase’s foil in the Vacation comedies—then you already And now, in the midst of the pandemic, she’s plotting her have a good sense of what she’s really like: She’s smart as a latest project: a one-woman autobiographical multimedia whip, quick with a comeback, by turns emotional, funny, show in which she will try to explain it all. In fact, I feel as

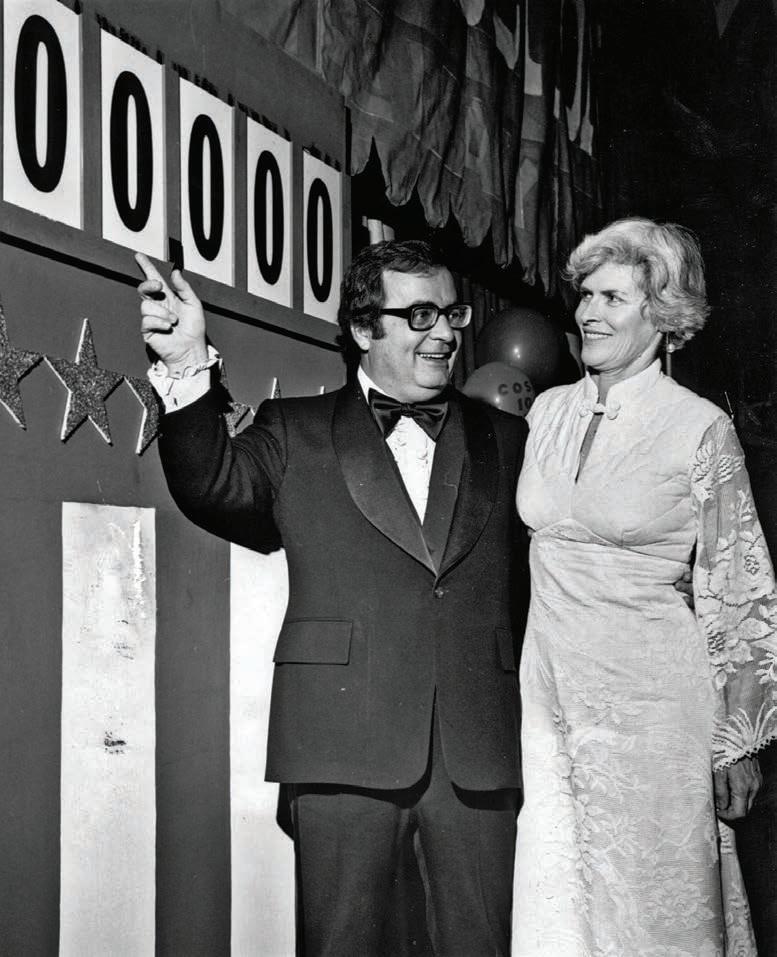

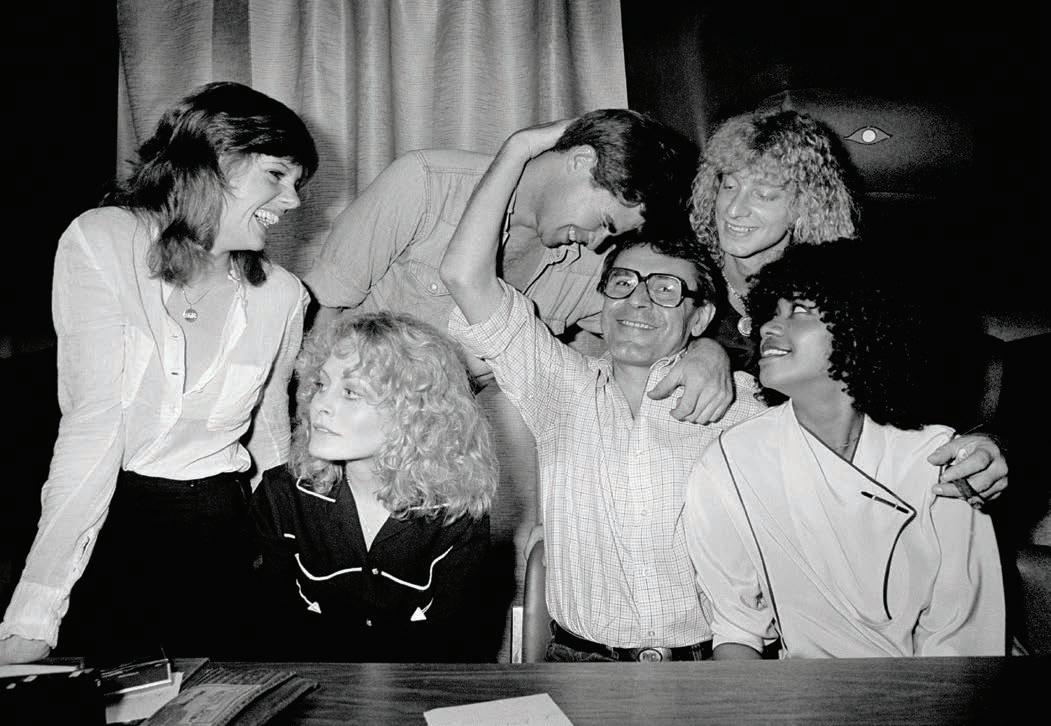

Clockwise from left, D’Angelo at her Los Angeles home; her parents, Gene and Priscilla D’Angelo in 1977; a school photo from 1960–61; D’Angelo with Milos Forman (glasses) and the cast of “Hair” at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival

though she’s done just that by the time I hang up from that initial interview—two hours after I picked up the phone.

D’Angelo’s screen identity is bawdy but cultivated, passionate yet unafraid of being the butt of a joke. “She has great, really complicated qualities,” says Stephanie Zacharek, the film critic of Time magazine. “She’s really earthy in some ways, but she’s also very sophisticated.” Despite such strengths, D’Angelo’s career—not as distinguished as those of peers like Jessica Lange or Debra Winger—has been a source of some regret for her admirers. In 1992, the late Pauline Kael, the legendary New Yorker film critic, summed up the consensus view, saying, “She’s really a symbol of what’s wrong with movies right now. How could an actress so beautiful and talented not get cast in better films? God, is it really possible that people like some of the women they cast nowadays more than Beverly D’Angelo?”

There were, of course, good parts. Her performance as Patsy Cline in “Coal Miner’s Daughter” landed her a Golden Globe nomination—what should have been the first of loads of nominations and awards. But D’Angelo was never again nominated for a Golden Globe, and never, ever nominated for an Oscar. “Part of it was me,” she says today. “I resisted being branded. To this day I do. It’s very, very difficult for me to identify myself in a way that feels constrictive.”

Instead, D’Angelo made odd choices and left turns. In 1983, after “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” she signed up to appear in a raucous comedy starring Chevy Chase as suburbanite Clark Griswold, “National Lampoon’s Vacation.” The movie racked up enormous box-office receipts, and D’Angelo’s performance as Ellen Griswold, Clark’s levelheaded but pugnacious spouse, personified the prototypical movie mom for a generation. There was a trio of sequels, plus a reboot. “I know she made a ton of them and people always kind of say, ‘Oh you know, poor Beverly D’Angelo—stuck in those comedies,’” Zacharek says. “But she’s really good in them. … I’m not crazy about Chevy Chase in general, so to me, she makes those films so watchable and enjoyable.”

D’Angelo took the work seriously, modeling Ellen in the Vacation comedies on Priscilla and even incorporating her mother’s full name in the last film in the series, 1997’s “Vegas Vacation.” When Clark and Ellen renew their vows, she gives her name as Ellen Priscilla Ruth Smith Griswold. “Ellen is the devoted wife—the thick and thin,” D’Angelo says.

Top, a still from “National Lampoon’s European Vacation”; bottom, D’Angelo as Patsy Cline in “Coal Miner’s Daughter”

D’Angelo’s 1981 marriage—her only—to a member of Italian nobility, a duke named Lorenzo Salviati, also contributed to her blasé attitude about career advancement. She told People magazine that she met Salviati the previous year after attending a series of parties, the sort where “you carry a spare cocktail dress and get home a day later.” For D’Angelo, though, becoming a duchess—seeing firsthand “deep, heavy-duty, multigenerational wealth”—made jockeying for position in nouveau riche Hollywood even less enticing. “I lived a life of royalty,” she says. “I’d come back to Hollywood and I’d see all these people striving to get a Bentley and trying to speak mangled French to order something in a fancy restaurant—and I’d think, ‘I have this.’” The marriage lasted 15 years.

Fellow actors sing her praises. “She’s thoroughly enjoyable,” says actor Michael O’Keefe, who co-starred with D’Angelo in a farce directed by “A Hard Day’s Night” helmer Richard Lester, 1984’s “Finders Keepers.” “She’s hilarious. She’s completely whacked-out, in the right way.” But marquee movies remained out of grasp. When Hollywood made a whole movie revolving around Patsy Cline, 1985’s “Sweet Dreams,” they cast Jessica Lange. A pattern was starting to emerge: Beverly D’Angelo was more interesting and inventive than the movies that surrounded her. But Zacharek says that’s OK. “Every time she shows up, she just opens up this little bit of magic,” she says. “And when you think someone has done that, really during the course of a long career, that’s actually valuable.”

Not that movie stardom was top on the list of D’Angelo’s goals anyway. When she was a teenager, she just wanted to be a cheerleader. The second oldest—and only daughter—of Gene and Priscilla’s four children, D’Angelo and her family were longtime residents of the wealthy, WASPy suburb of Upper Arlington. Naturally, D’Angelo tried out for the ultimate wealthy, WASPy activity as a sophomore at Upper Arlington High School: cheerleading. She felt pretty good about her chances, too.

“My audition was great,” D’Angelo remembers today. “I got everybody so excited. My jumps were good. I was really made to be a cheerleader. I was so cute and everything.”

But it was not to be: The shoo-in was named a mere alternate. “I think—and it’s just my theory—but I think the reason that I was made an alternate cheerleader, and not the bigdeal cheerleader, was because, statistically speaking, there’s always a cheerleader that gets knocked up,” D’Angelo says. “They probably looked at me like, ‘That’s the one.’”

Her story begins at the Beverly Manor Apartments, where her parents were living at the time of her birth in November 1951. Family lore has it that her first name was inspired by the building, but she also heard that she was named after a drummer who had been a friend of her father’s. She prefers the second version.

In August 1949, Gene—a first-generation Italian-American who first made his living as a musician—and some buddies got dressed up to go to one of Upper Arlington’s swimming pools. There, the fellas reckoned, they would encounter wealthy, attractive members of the opposite sex. “He walks in, zoot-suited up, to that swimming pool and sees my mother,” Beverly says. “He said the bathing suit was gold. She said it was silver. They both told me this story many, many times. He walked up to her, and he said, ‘Are you seeing anybody?’ And she said, ‘Yeah, a couple of guys.’”

It was not so hard to believe: Besides being beautiful, Priscilla Ruth Smith was born to a prominent old family. Her father, Howard Dwight Smith, was the architect who dreamt up the design of Ohio Stadium and other prominent structures around town. She had graduated two years earlier from Smith College, where she studied the violin. The couple eloped four months after the poolside encounter.

After plying his trade as a musician for the first seven years of Beverly’s life, Gene shifted gears in 1955, entering the broadcasting business and eventually rising to prominence as the chairman and president of WBNS-TV. Gene’s

success improved the family’s station, and while the children were encouraged to be creative, a certain dull conformity seeped in. “We purposely, growing up, would all buy the same clothes,” D’Angelo says. “We wore our hair the same. We spoke the same. We ate the same.”

While an Upper Arlington High School student, D’Angelo spent a summer in Italy. When she returned home, her suitcase was affixed with a sticker reading “Make Love, Not War.” The experience opened her eyes to the world beyond suburban Columbus, and it felt suffocating to return home. “It was like, if somebody had shown you how to fly, and then you were locked in a cage,” she says.

Her mother counseled her: “You’re soul-searching, but you don’t even have a soul yet.” Profoundly glum, she transferred to Whetstone High School for her senior year. Mostly, though, she lost herself in magazines and the places they took her to. “I read an article about Janis Joplin, and I kept rereading it over and over again,” she says. “It all became about getting to California.”

On the strength of her father’s media connections, D’Angelo did make it to California. Having participated in an art-study program during a subsequent trip to Italy, her father’s pull enabled her to get a job as an inker and painter at the Hanna-Barbera Animation Studio. She downplays her artistic talent; the real point was to be part of the so-called “summer of love.” Burrowing deeper into the counterculture, in the early 1970s, she pulled up stakes and moved to Canada. There, she indulged her lifelong secret wish to become a singer—you know, like Janis Joplin. “If you had a shopping list to check the boxes of who would be a revolutionary, countercultural-living flower child, it would be me,” she says.

After joining a musicians’ union as (of all things) a castanet player, she found herself singing jazz standards, from 6 until 11 p.m., in a topless bar called the Zanzibar Tavern in Toronto. “I wasn’t topless,” she says. “I sang in a long black dress, in between two girls on these oil drums with the tops cut off and plexiglass with a light that would shoot up and illuminate them as they danced in a G-string.” She adds: “I felt like I was Billie Holiday.” There were better gigs, too. She even sang backup with Ronnie Hawkins.

D’Angelo actively pursued singing, but she fell into acting. (“I never wanted to be Sarah Bernhardt,” she told Columbus Monthly in 1979.) But, while still abroad, she landed a part in a radio musical about Marilyn Monroe on the CBC, and she toured the provinces as Ophelia in a rock ’n’ roll version of “Hamlet,” first called “Kronborg: 1582” and later retitled “Rockabye Hamlet.” In 1976, just after the show opened on Broadway, D’Angelo told The Columbus Dispatch that being plucked from obscurity really didn’t surprise her all that much: “It all seemed very logical. I knew I could handle the music.” She says today, “For my mad scene, I strangled myself with a microphone cord and died onstage with fire alarms going off.”

Casting directors fell for her. Her first movie role came in 1977 with Woody Allen’s “Annie Hall,” in which she can be glimpsed—and briefly heard—in what amounts to a walkon. “He gave me my Screen Actors Guild card,” she says. Not long after, Milos Forman, the Czech director recently honored with an Academy Award for “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” was casting about for actors to appear in his film version of the hippie-themed musical “Hair.”

D’Angelo, seemingly made for the part, drew the director’s immediate attention, professionally and otherwise. A dinner date with Forman led to a love affair, which complicated the casting process. “There were more auditions, and even more auditions, because people started to know that I was having an affair,” says D’Angelo, who, overwhelmed, fled to London only to receive a pleading phone call from her boyfriend-director: “He said, ‘I need you,’ and I said, ‘As a girlfriend or as an actress?’ And he said, ‘Just come back—both!’” She came back. She got the role.

continued on Page 75

Beverly D’Angelo with Carrie Fisher in 2015

When the Killings Stopped

What a short-lived experiment on the south side of Columbus can teach a city struggling with gun violence

By Theodore Decker

For this marCh, they will head west, to the spot where a bullet ended the life of Jaleel Carter-Tate five days earlier.

It is Sunday, Oct. 4, and about 25 people have gathered at the Family Missionary Baptist Church on Oakwood Avenue, the starting point for this monthly plea for peace. A gusty storm front races toward Columbus from western Ohio, but no one talks of canceling the event, the 132nd march against gun violence held by a grassroots collective known as Ministries 4 Movement. Today marks 11 years of marching, through 44 seasons, and a discouraging weather forecast isn’t about to end the streak.

Carter-Tate was 25 years old when he died on the South Side on Sept. 29, in the 800 block of East Whittier Avenue. Columbus police were called before 10 p.m. and found him bleeding from a gunshot wound. He died on the scene, becoming the 116th victim of homicide in what is shaping up to be the bloodiest year on record in Ohio’s capital city.

The marchers stop at the spot where Carter-Tate fell. A nearby street sign has become a roadside memorial. Mylar balloons are tied in a tangle to the post, and crowded below is a cluster of stuffed animals. At first blush, they seem like an odd tribute to a man in his 20s, seated as they are among an assortment of liquor bottles. But teddy bears are common at memorials marking deaths that are as untimely as they are violent. They are futile bids to turn back the clock.

A few speakers step forward. One man says a dispute over a sports bet may have caused Carter-Tate’s death. If true, it is in keeping with the trend that most of these killings are not the result of the drug trade, as many would have you believe. They inevitably arise from what criminologists call “interpersonal disputes,” a catchall term for an array of petty beefs and more serious grievances that in some instances fester for years before exploding on the streets. A bumped arm in a packed nightclub leads to a spilled drink, then to words, and finally gunfire. Trash talk on social media inflames tensions between rival teens. A young boy sees his older brother killed and waits until he is grown, sometimes for years, to impose street justice on a shooter who avoided arrest.

But what happens if an outsider steps into these volatile situations, someone from the neighborhood with street cred, good intentions and impeccable timing? Vulnerable young people might regain control of their emotions, stopping themselves from acting on violent impulses. The people involved in this march can attest to the power of these interventions because, well, they’ve done them. Nearly a decade ago, they launched a short-lived pilot program called CeaseFire Columbus that coincided with a dramatic drop in violence in a 40-block section of the South Side.

This group was within striking distance of a strategy that, if it had been embraced by

CeaseFire Columbus leaders Deanna Wilkinson, Frederick LaMarr, Cecil Ahad and Dartangnan Hill outside Family Missionary Baptist Church

Minister Aaron Hopkins, left, and Rev. Frederick LaMarr lead a march against gun violence in November.

the city, might—just might—have saved Carter-Tate. Instead, they march in mourning.

Columbus is on traCk in 2020 to record its most lethal year for homicidal violence. In 1991, 139 people were killed. That was the height of the city’s crack cocaine trade, and that record stood for nearly two decades as killings hovered around 90 to 100 each year. Murders jumped in 2017 to 143, only to fall back in 2018 and 2019 before surging again this year.

In fact, the violence has soared to such levels in 2020 that Mayor Andy Ginther and his administration have been regularly addressing it, even during a year dominated by the coronavirus pandemic and weeks of racial justice protests.

In his fourth violence-related news conference of the summer, Ginther pledged $200,000 in federal money to each of four nonprofits, which in turn could pass some of the funds on to smaller groups.

Earlier in the summer, the mayor also announced the formation of violence intervention teams and outreach at hospitals. But the most promising development came in October, when the city announced it was partnering with David Kennedy, a professor of criminal justice at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City and the director of the National Network for Safe Communities. For $80,000, the city hired Kennedy to help suss out who and what is driving the city’s violence. That study is expected to take six months.

“The theory is that there is a small percentage of individuals committing the large amount of violent crime that is taking place in our community,” says Ned Pettus, the director of the city’s Department of Public Safety.

That is not a new theory, or one that is unique to Columbus. In fact, it was one of the foundations of CeaseFire Columbus, which was founded in 2010 and run by Ministries 4 Movement. Criminologists say gun violence is driven by a fraction of a percent of the population. A 2011 Ohio Attorney General study, conducted by Ohio State University, found that offenders convicted of three or more violent offenses accounted for less than 1 percent of the state’s population but a third of all violent crime convictions over nearly four decades.

Kennedy helped to pioneer a carrotand-stick approach to reducing gun violence in Boston in the mid-1990s, an effort that came to be known as the Boston Gun Project’s Operation Ceasefire. Once identified, those key players on the street are called in to meet with law enforcement and told they will be hammered relentlessly as long as they continue to engage in violence. But if they are serious about leaving street life behind, a vast support network will help them. As word of the Boston success spread, cities across the country adopted similar efforts.

There is no single formula for successfully reducing violence, but the most promising approaches are built upon a base acknowledgement that to reduce violence in any city, you must engage directly with those violent offenders. “That’s what characterizes everything that works,” Kennedy says.

During the oCtober marCh, Deanna Wilkinson speaks to the gathering about a 15-year-old boy killed recently on the East Side. Two years earlier, he’d participated in the Urban GEMS gardening program she began in 2015. The program started with a small garden beside Family Missionary Baptist Church but has expanded since, teaching children to grow and sell their own produce while building confidence, healthy choices and life skills. Many have grown up surrounded by violence.

“These are complicated lives,” says Wilkinson, a criminologist and associate human services professor at Ohio State University. She touches on the frustrations of violence prevention work, the occasional politics, the constant struggle for funding. “These young people are worth a lot,” she says. “Every time we lose one, we lose a huge part of our city.”

In 2007, Wilkinson brought together an array of city officials, law enforcement agencies, human service organizations, community activists and faith leaders to form the Youth Violence Prevention Advisory Board, a group meant to brainstorm solutions to gun violence. Through the board, she got to know better Tammy Fournier Alsaada, a leader of the People’s Justice Project. They joined with Cecil Ahad, a South Side activist known as Brother Cecil and the founder of Ministries 4 Movement, and the Rev. Frederick LaMarr, the pastor of Family Missionary Baptist Church. Both were doing their own work to provide mentors and positive role models for young men and boys at risk of falling into their neighborhood’s cycle of violence.

That group of four formed the core of what would become CeaseFire Columbus. “We were a really good team,” Wilkinson says.

“Dr. Dee, she had all the statistics, and she could do the numbers and paperwork,” LaMarr says. “Me and Brother Cecil, we had the boots on the ground.” Fournier Alsaada, Wilkinson says, had a strong drive and a special ability to distill conceptual research into plain English.

Ahad also had forged a relationship with Dartangnan Hill, a founder of the neighborhood’s Deuce-Deuce Bloods street gang who had tired of the violence. After Ahad’s nephew was murdered, the pair held in November 2009 what became the first neighborhood march. “It was Dartangnan who really introduced us to a lot of people, who opened a lot of doors up for us,” Ahad says.

This Columbus collaboration was inspired by the work of Dr. Gary Slutkin, a Chicago physician and public health expert who noticed gun violence spread like an infectious disease. Like Kennedy, Slutkin’s intervention efforts focus on reaching those who are most likely to spread violence, but his tactics differ from his fellow researcher. Slutkin’s initiative, Chicago’s CeaseFire (now called Cure Violence), avoids partnerships with law enforcement and instead relies on street-level violence interrupters who, because of their own history on the streets, carry respect and are able to defuse volatile situations before they lead to gunfire. Over the longer term, these interruptions accrue, reinforcing that violence is no longer “necessary” or tolerated. Caseworkers, meanwhile, support those who want out of the life, while community activists labor to change societal norms through public education campaigns and neighborhood marches.

In 2010, Wilkinson invited Ministries 4 Movement to implement a Columbus version of the Chicago model. Local leaders based their operations at LaMarr’s church and trained in Chicago. They drew up a detailed proposal for a pilot program and sought money to pay for it. They made a pitch to Mayor Mike Coleman’s administration and asked for $750,000, which would have paid for two sites for a year. “They are completely ready,” Slutkin said during a 2011 visit to Columbus. “They need government support.”

They didn’t get it. Coleman did not put the project into his budget and went instead in another direction, throwing his support and city money behind a Recreation and Parks program known as Applications for Pride, Purpose and Success. APPS sought to provide an outlet for young people at city recreation centers, along with mentoring, job training and high school equivalency. Its violence-prevention component stumbled in the first year due to infighting, but the city wrote off those troubles as growing pains and considers the program a success.

continued on Page 76

Top, Davontay Womak, left, and Terry Felder listen to Frederick LaMarr, center, with Cecil Ahad, right, in 2016; bottom, Ahad, right, speaks at the spot where 17-year-old Lamont Frazier was killed in 2013.

Home&Style

Q&A p. 54 | produCts p. 55 | home p. 56 | top 25 p. 62

54

AbundAnt SundrieS

A new shop opens in German Village.

Photo by tim johnson

A Pandemic Launch

An equestrian opens a German Village boutique

By SHERRY BECk PaPRoCkI

After a 20-year career in public relations, Barbie Coleman launched Urban Sundry Ltd. in December of 2017 with two online brands: Urban Sundry and Equestrian Sundry.

She also set up shop at local outdoor markets such as the German Village Makers Market and equestrian events throughout the Midwest. For the last two years she’s run a seasonal storefront, September through April, at the World Equestrian Center in Wilmington. People always asked when she was going to open a full-time, brick-and-mortar location. Coleman lives in German Village and, one day, she spotted a “For Rent” sign while driving in the area. That was in February of this year and, knowing this was the right space, she steered toward a move-in date of May 1.

Then the world shut down. “Believe it or not, there wasn’t a question of whether or not to keep going,” says Coleman. “I know only one direction and that’s forward.”

“I also have an incredibly supportive husband who said, ‘Do what you always do and make it happen,’” she recalls. “I’m the first one to say ‘challenge accepted!’ when things look tough.”

Given the pandemic during this holiday season, Coleman’s shop has regular hours but will also cater to those who want to schedule private shopping time.

You are happiest on horseback, according to your LinkedIn profile. Has owning a store changed any of that? I’ve ridden and showed horses for most of my life. For the better part of my professional career, I took a hiatus from showing, but I always had a horse and rode whenever time permitted. It is a happy place for me and I’m grateful that I’m still able to have a horse in my life. Horses challenge you, humble you and they most definitely give us more than we deserve at times. I’ve always said to people “what grounds you, will save you” and horses are definitely that for me. Once I opened my business, I stopped showing

Barbie Coleman stands in her German Village shop. Read more at columbusmonthly.com.

and now that I have the store, my riding schedule has certainly changed. I’m out the door at 6:30 a.m. most mornings to go ride before I open the store.

What did you do before you became a shop

maven in German Village? I worked in public relations for 20-plus years up and down the East Coast before moving to Columbus in 2010. I’ve done just about everything in public relations from working with small brands, global brands and even a few years doing society [philanthropic] public relations in Palm Beach. My specialty was crisis management so I always laugh that some of my best work is work I can’t talk about. I worked just as hard getting in The New York Times as making sure my client or company wasn’t in The New York Times. It can be a pretty thankless profession but I really loved the challenges and problem-solving it presented and the extraordinary experiences I had, the people I met and the places I traveled.

How does your past experience play into your current position as boutique found-

er? I never could have created my company and opened my store without those professional experiences and the people I worked with. As I was honing my craft as a PR person, I was also figuring out who I was. My whole world was my job and my identity was wrapped up in the failures and successes of whatever client or company I was working for. As I got to know myself and understand the person I really am—not the one everyone told me to be—I was able to start to see what was next for me. ◆