11 minute read

STEPPING UP

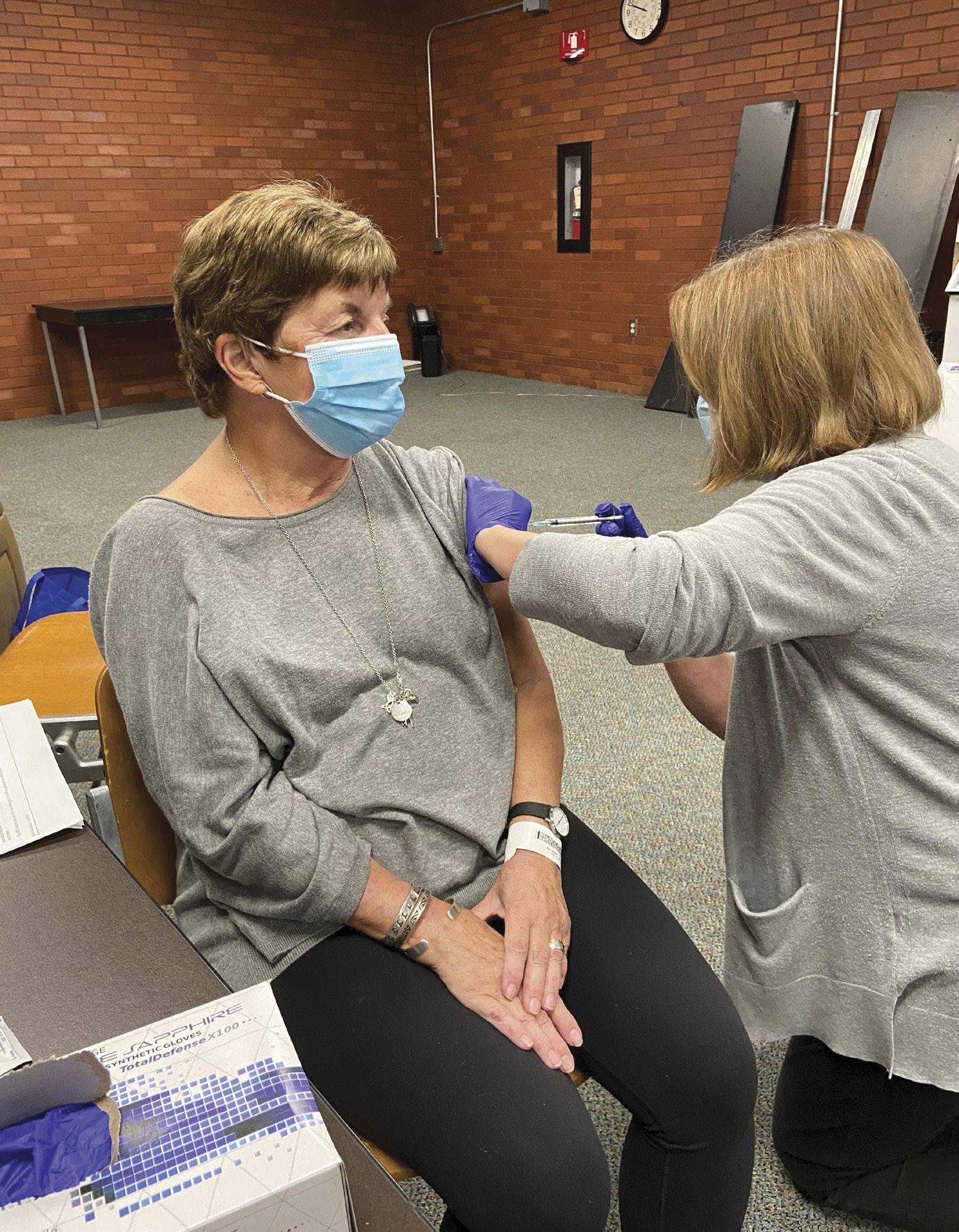

Holly Garden, left, along with Jan and Chuck Mader are involved in vaccine trials for COVID-19.

Local volunteers and researchers participate in clinical trials to find a COVID-19 vaccine.

BY SANDRA GURVIS

LAST SUMMER, WHEN JAN MADER of Clintonville learned that AventivResearch was looking for volunteers for a COVID-19 study for the Pfizer vaccine, she jumped at the opportunity.

“In early March, before the quarantine lockdown began, my sister caught COVID-19 on a plane coming back from New York City,” she recalls. “She lost her sense of taste and smell and was having trouble breathing. But she didn’t want to leave her animals so she stayed at home [and didn’t go to the hospital].”

Jan, a long-time equestrian, who cares for her horse,

Tango, as well as several other pets, could certainly relate. “It was terrifying,” she says of her sister’s ordeal.

Jan’s husband, Chuck, is a former pharmaceutical sales representative and is now retired. He had different reasons for enrolling in the clinical trial. “For me, the motivating factor was my age,” says Chuck. “The older you are, the higher your risk.” Although Jan is still in her 60s, Chuck is in his early 70s. The CDC reports that people ages 65-74 are five times more likely to be hospitalized and 90 times more likely to die than people in the 18-29 age group. Eight out of 10 deaths due to

COVID-19 in the U.S. are people who are 65 and over.

“I am very familiar with the protocol and procedure of clinical studies,” Chuck continues. “The studies are run with such detail and care that I knew that the vaccine would be relatively safe.”

The Maders, as it turns out, are part of the clinical trial that produced one of the first notable COVID-19 vaccines, created by the drug giant Pfizer in conjunction with researchers at BioNTech. The company was the first to announce in early November that its vaccine was at least 90 percent effective.

Close on the heels of the Pfizer effort is another vaccine by Moderna, which announced that it was nearly 95 percent effective a week following Pfizer’s announcement. (In later weeks, Pfizer said its vaccine had a 95 percent effective rate, too.) On Nov. 20, Pfizer filed for emergency FDA approval. Moderna was close behind, filing for emergency approval on Nov. 30.

For those fascinated by the politics of competitive science, this is a story unfolding in real time.

UNPRECEDENTED SPEED The onset of COVID-19 has pushed scientific research to astonishing speeds. Of the more than 3,500 federally-funded COVID-19 studies, 196 are clinical trials relating to a vaccine, according to clinicaltrials.gov.

The number varies, depending upon the source, but there are 150 to 200 vaccines in development globally.

While the Pfizer/BioNTech trial includes approximately 44,000 people worldwide, in Central Ohio, Aventiv is a company that is watching over 300 par-

ticipants in a blind study. The Maders don’t know whether they’ve received the real vaccine or a placebo.

“Given its large and diverse population and potential for high rates of infection, we knew that Columbus would be an ideal place for a study,” says Dr. Samir Arora, Aventiv’s president and medical director. He and his company have been involved in over 200 clinical research trials that involved proposed treatments for hypertension, diabetes, obesity, pain, asthma, COPD and more.

“Although we have a database of some 40,000 patients, the community’s response to the COVID vaccine study has been tremendous, with volunteers from as far away as Michigan, West Virginia and other states,” says Arora. “COVID has hit minorities especially hard so we have worked towards enrolling a proportionate number of Black and Hispanic volunteers.”

Regardless of who or what is being studied during a clinical trial, “certain protocols remain in place,” explains Dr. Susan Koletar, director of Ohio State University’s division of infectious diseases and principal investigator for the AIDS clinical trials unit at OSU.

Koletar, who has worked for more than 30 years in clinical trials, is also working on a COVID vaccine project with Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. The trial is part of a larger effort co-developed by the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca pharmaceuticals with about 30,000 volunteers. OSU’s portion of the trial involves 500 adults. On Nov. 20, AstraZeneca announced that its vaccine also had close to a 90-percent effective rate, too, although the results of the AstraZeneca study were undergoing close scrutiny at press time.

TAKING PRECAUTIONS Although the AstraZeneca/University of Oxford effort was paused in September after a participant fell ill, it has been fully resumed, including at Ohio State. In late November, OSU was looking for a mix of healthcare workers and those at high risk of exposure, such as teachers, first responders, college students, factory workers and restaurant employees as well as those 65 and older for its AZD1222 COVID-19 vaccine study.

Such starts and stops are fairly common in clinical trials, notes Koletar. “People should be comforted by the fact the scientific community takes responsible action when things don’t go as planned,” she adds. “These trials are done in phases, with a lot of preclinical work.”

Depending upon the condition being studied as well as numerous other factors, trials usually have three to four phases, with a certain number of people in a control group receiving a placebo. According to the World Health Organization, Phase I studies usually test new drugs for the first time in a small group to evaluate a safe dosage and identify side effects. Phase II involves a larger number of participants, investigating details such as a maximum tolerated dose, the optimal schedule for giving the product and whether the participants’ immune systems are having the desired responses.

Phase III studies are conducted on larger populations and in different regions and countries. Phase III is often the final step before a new treatment is approved by the FDA. “In Phase III, scientists address questions such as, ‘Does this product prevent new infections? Or if people do become infected, does

Patricia Iams, 73, of Upper Arlington was the first person to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine trial at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Dr. Susan Koletar, director of OSU’s division of infectious diseases, is overseeing a 500-participant clinical trial for the AstraZeneca vaccine.

A lab tech at the University of Miami processes blood samples for the Moderna study. The Moderna vaccine was developed with funding provided by the National Institutes of Health.

the product help them control the infection so that it doesn’t become severe disease?’”explains the Coronavirus Prevention Network.

Optional Phase IV studies may take place after a country approves a vaccine, depending on whether there seems to be a need for further testing in a wide population over a longer timeframe.

With the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, clinical trial patients received two vaccines 19-23 days apart during Phases II and III. A certain number of the first 6,000 subjects in the overall study were required to report any symptoms for seven days after each vaccine.

“Those patients, as well as the patients that were not a part of that daily reporting, are just required to report whether or not they have had any symptoms of COVID at least weekly, or as needed,” explains Grazia Cannon, a sub-investigator with Aventiv. Questions during the reporting phase pertained to possible immunological reactions, including their highest temperature of the day, redness, pain, swelling at the injection site, fatigue, headache, vomiting, muscle aches, joint pain and more.

Chuck Mader had a sore arm and a fever of 100 degrees for 24 hours, while Jan experienced no reaction whatsoever.

Another Central Ohio study participant, massage therapist and former teacher Holly Garden, 63, described the shot as “a quick twist, that later hurt like an SOB.

“But I did a pre-emptive strike with Advil and it went away,” says Garden. “I did have quite a reaction to the second injection—fever, aches and so forth. I don’t think a saline injection placebo would have caused those symptoms.”

VACCINES HAVE CHANGED The first vaccine ever developed was in 1796 for smallpox. Historically, most vaccines take years to produce and involve injecting a small amount of whatever formidable virus into its formula so that the person taking the vaccine develops an immunity to the virus.

Times have changed, though.

Today, researchers have the ability to create treatments and vaccines faster than ever before because some vaccines are rooted in biotechnology, which is the genetic manipulation of micro-organisms. In the case of both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, genetic coding in the vaccine helps a person develop the ability to fight the disease because their body develops antibodies to the spike protein in COVD-19. The genetic code for the entire COVID-19 virus has not been put into the vaccine.

Finding a COVID-19 vaccine has been a global challenge, and 2020’s research efforts have produced several different types. The World Health Organization initiated a worldwide vaccine development effort with a goal of distributing two billion doses by the end of 2021.

Although vaccines generally take years to develop, there are a few reasons why the COVID-19 vaccine has come faster. In part, there have been massive financial contributions made by governments worldwide, including a $9.5 billion commitment from the U.S.

In addition, those working on the COVID-19 vaccine benefit from genetic discoveries that are being studied to fight other diseases. For example, the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, known scientifically as mRNA vaccine candidate BNT162b2, uses a technology developed during clinical trials for cancer that has never been licensed for any disease.

If approved by the FDA, this vaccine is on schedule to be the first mRNA vaccine approved for human use. Pfizer anticipates producing up to 50 million vaccine doses in 2020 and 1.3 billion doses by the end of 2021.

Moderna’s Phase III study for its mRNA-1273 vaccine has enrolled most of its 30,000 volunteers and is on track to deliver at least 500 million doses per year beginning in 2021.

Both Pfizer and Moderna are hoping to use their vaccines on those with the highest risk first. Both companies, however, are focusing on the manufacturing and distribution challenges that lie ahead for the mRNA vaccines that must be kept frozen for some amount of time.

The freezing requirement for vaccines produced by Pfizer and Moderna could make their distribution more difficult, especially to places without advanced medical facilities. Further complicating matters is that Pfizer vaccine must be kept far colder (-94 F) than Moderna’s (-4 F). Think subzero Antarctica versus your basic pharmaceutical freezer.

ADENOVIRUS VACCINES The coming Johnson&Johnson vaccine (JNJ-78436735) has shown great promise though it, like the University of Oxford/AstraZeneca effort, is developed differently and made from a common cold virus. Such vaccines are called viral vector vaccines in which the adenovirus is the vector, in this case.

Johnson&Johnson anticipates that, if proven to be safe and effective, the first batches of a COVID-19 vaccine will be available for emergency use authorization in early 2021, according to a press release issued by the company.

The sheer volume of vaccines needed worldwide means that each of these four efforts—vaccines by Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca and Johnson&Johnson— could become major players in the business of COVID-19 vaccines.

VACCINE CONCERNS How long a vaccine will be effective against COVID-19 remains to be seen. Arora of Aventiv expresses concern over their acceptance among the general population. “Some surveys have said that 40 percent of respondents will not take the vaccine when it comes out,” he says. “Some people have a fear of vaccines that goes against the technology and research behind them.”

Yet vaccines will help restore freedom and peace of mind to a pandemic-weary population. “People are very social creatures,” notes OSU’s Koletar. “Social distancing is hard on the world. Kids who come to college don’t want to stay in their dorm rooms all the time.” And while many people wear masks, that gets old as well. “No one likes barriers,” she continues.

Local participants in the Pfizer clinical trial see their efforts as contributing to the greater good. “Of course there is some element of risk,” says Garden. “But God has taken care of me so far and the whole process, including learning about the virus, is fascinating to me. Plus telling people that you’re doing a virus vaccine study makes a great story.”

Chuck and Jan Mader also feel that their active lifestyle continues to provide them with physical resilience that others of similar age may not have. “Just about every day we go out to the barn, and between taking care of that, the horses and other animals, it’s a lot of physical work,” Jan says.

The three local participants don’t know yet whether they’ve had the vaccine or a placebo. “My question as a participant in the study is: Will we now have an option to get the vaccination if we had the placebo?” Jan asks. “Will they unblind the study so we can know?”

Either way, she wants to be sure that she’s vaccinated against COVID. “When I tell people that I’m getting the vaccine, they say, ‘Aren’t you afraid?’’ Jan continues. “Not really, not after I saw what my sister went through. And if it means I’m going be around to hug my grandkids, I’m happy to do it.” ✚