15 minute read

Baxter's Garage Tells All

Article And Photos By: Kevin Baxter

Advertisement

in this month’s article I will tell you how you can uncover hidden acceleration in your engine build, but note, it’s not for everyone because there can be negative effects that you may not find too appealing. There will be a little science and physics to discuss because I want you to fully understand what’s at play before you make a buying decision.

Crank shaft lightening seems to be a recent trend in the mainstream yet it goes back to the days the first bikes and cars were modified to go faster. The concept nothing new but I get several calls a week from people asking about it.

Let’s start with the basics. We first need to get our terminology correct to fully understand the physics of what’s going on inside the engine case. Many people will interchangeably call the rotating assembly in the bottom of the engine a flywheel or crank shaft. Technically speaking, we should call it a crankshaft assembly because it consists of multiple pieces, two of which are flywheels, one on each side joined by a crank pin. In simple terms, we have two flywheels assembled to make a crankshaft assembly. Every reciprocating engine has a flywheel of sorts, even steam engines. There

is a science to determining what the weight of a flywheel should be. Factors such as operating range, intended RPM, number of cylinders, power output, the engines intended use, and load all play a factor.

I’m sure you’ve seen old hit and miss single cylinder engines that have huge flywheels on them. The flywheel(s) are large to help govern RPM but also because of their weight, they store a large amount of kinetic energy which is the energy of motion. In physics terms, flywheels use the conservation of angular momentum to store rotational energy which is proportional to the product of its moment of inertia and the square of its rotational speed…but that’s probably going a little too far. To simplify and better explain, flywheels are large counterweights, designed to stabilize and slow down RPM response. This slow and safe stability offers RPM comfort while riding through traffic or cruising in a steady RPM range down the highway. A heavier flywheel or crankshaft assembly will make an engine run smoother and provide a little extra push to assist the engine during normal operation while under load. The trade-off is that the extra weight can also create a parasitic

loss that may reduce your rate of acceleration.

All other things being equal, an engine with a lighter flywheel or crankshaft will generally accelerate much faster. It will be more responsive to quick rider input or RPM changes. It will also decelerate much quicker under load. This is great in say, road racing environments where riders go into corners fast and brake as late as possible then blast out of a turn. This could also be advantageous in very light vehicles where you want a near immediate response to rider or driver input.

The downside is if you have a heavier bike or heavier rider or more often find yourself in moderate or steady state riding like touring, it will make the engine feel jerky. You might also notice a substantial increase in fuel consumption because you no longer have the assistance of inertia to help you spin the engine over during those times you are on and off then back on the throttle. You wouldn’t really want a light crank in an engine that is being used primarily for pulling or where low-end torque is a focus because the extra weight increases reciprocating momentum and can, in fact, help the lower portion of the RPM range of the

engine, especially engines that have a manual transmission behind them where you’re on and off the throttle during gear changes.

It is fair to say crankshafts don’t normally operate at constant rpm. They are either accelerating or decelerating. Their resistance, in either case, includes static weight and dimensional landscape (stroke length, location and distribution of mass, and other factors). Technically speaking, in a dynamic environment, crankshafts are continually changing potential energy into kinetic energy. If it is lighter, it will increase your rate of acceleration and deceleration, but this doesn’t always equate to an increase (or decrease) in horsepower. In the photos you will see two crankshaft assemblies. As we do with all of our custom engines, we install custom built crankshaft assemblies that suit you and your riding style perfectly. Engine size, RPM riding range, compression ratio, and cam shaft are just a few factors that determine the design

specifications.

Both of these have H beam, rods, both have been balanced. Both have been plugged, trued, and welded at the crank pin. They will also receive a tapered main bearing. Both of these assemblies are 4.375” stroke and would fit inside a 2007 and later twin cam “A” engine but they couldn’t be more different when it comes to the details.

One has been lightened quite a bit having material precisely removed from the flywheel halves and along the inner edge of the wheel. The owner of this motorcycle is light weight. He mostly rides one up. He rides in the mid to upper RPM range and wanted this engine to respond like we would expect a lightened crankshaft assembly to operate.

As for the other crankshaft assembly, the owners of this bike ride mostly two up. They spend their time touring. They wanted an engine that would operate smoothly for their leisure rides in the twisties and on long highway or back road stretches as well. They also primarily ride in the lower range of the RPM scale. Each of these crankshaft assemblies

have a specific purpose and goal.

One other aspect of crankshaft design to consider is knife edging. This is where the outer edges of the wheels are cut in at a taper. The purpose of doing this is to reduce turbulence in the engine case. Most of those effects however, really only happen at extremely high RPM. The vast majority of riders on the street will never even feel the difference on a crank that has been knife edged or hasn’t. I hope this better explains the pros and cons of crankshaft assembly lightening. Bottom line, there is no engine that is perfect for everyone, but there can be a perfect engine for you. To view the video on this topic and other technical topics as well, subscribe to my YouTube channel at www.youtube. com/kevinbaxter. As always, take care of yourselves and each other.

Kevin Baxter Baxter’s Garage

it was nearly 1am, dark, dusty, cold and quiet when Anton and I made the final transition from dirt to pavement. Eyes blurry and teeth chattering, we exchanged a tired glance of acknowledgment that we had officially conquered the 1,217 miles that is the Road of Bones. As the dust settled, both literally and metaphorically, the gravity of what we had accomplished began to set in, but that is not where this story begins. To fully understand and appreciate what we had done we need to reflect back to 7 days in the past.

In the early hours of the morning, 4:30 am, when the sun was already well into the sky in this northern region of Russia, the dark night sky only presents itself for a couple of hours in the summer months, we finished loading our motorcycles to catch the 6am ferry out of Yakutsk. There are no roads to this near Arctic city, so a ferry ride across the Lena River is your only real option. The one-hour boat ride would take us to the town of Nizhnii Bestyakh and the terminus a quo of the Road of Bones. After a quick top off of the fuel tanks, we headed into the unknown. Neither one of us had done extensive research, so there were a lot of unanswered questions that we would soon find the answers to. The only thing we looked into extensively was the distance between fuel stops. Which we determined was, on average, about 150 miles, with the longest stretch being 250 miles. Outside of these

assumptions, we had nothing but the warnings of others to base our beliefs on what the road had in store for us. Regarding warnings, both of us had been told repeatedly that the likelihood of either of our bikes actually making it to Magadan, the final destination, was slim to none. I remember hearing things about lack of suspension, ground clearance issues, how open belts were a terrible idea, blah, blah, blah. I’ve learned over the years to ignore most of what the naysayers have to offer and carry on with my business.

Anton was receiving similar warnings regarding the inherent unreliability of his 32-year-old Russian-built two-stroke Izh Jupiter 5. What the critics weren’t taking into account, however, was his uncanny ability to fix about anything with a toothpick and duct tape. Anton is essentially a Crimean McGuyver. All of this inherently then begs the question of why. Why were either of us going to such great lengths to ride one of the most formidable roads on the planet on bikes that are absolutely not built for this type of adventure? For myself, the answer is easy. For one, it’s the only bike I own, and two, after nine months and 31,000 miles on the road finishing my around-the-world journey on what is arguably one of the most challenging roads on earth seemed like the obvious decision. What better way to test your mental and physical stamina. I also have to admit that I wanted to find out if it was even possible on a bike like mine, I knew there was a chance that I might reach

a point that forced me to turn back, but I found that prospect to be unlikely. I also enjoyed the idea of being the first person to ride a chopper to Magadan. I can not verify this claim, but I think the likelihood of it being accurate is reasonably high.

Anton was tackling this road for equally absurd reasons. A group of friends back home bet him that his little Izh would never make it from his home in Crimea to Magadan…and back. He has proven them wrong, and just to up the ridiculous factor a bit, he opted to not only ride that two-stroke smoke machine to Magadan and back, but he decided to do it while pulling a homemade trailer built from a sidecar. This is one of the main reasons why, when I met Anton in Krasnoyarsk, I immediately recognized him as a perfect travel companion for the Road of Bones. We would both be slow on equally inappropriate motorcycles, with the likelihood of many time-consuming breakdowns being a real consideration.

So how was the actual ride? Brutal. The level of difficulty was everything I expected and often times much worse. The most challenging aspect of the ride was the fact that the conditions were ever-changing. The moment we began to feel comfortable with one element it would change, and we would suddenly have to adjust our riding style. The road would shift from hardpack dirt to deep sand in the blink of an eye, then deep loose rocks, then mud, then washboard, then back to hard-pack dirt, and so on. Bear in mind that all of these conditions were to the extreme, and the ease of the hard-pack dirt sections were short-lived and almost a tease that I quickly learned to not appreciate. My experience was that the brief areas of reprieve would come at a high cost, and the better the reprieve, the higher the cost later. For example, a 10-mile section of good road (to be taken with a comparative grain of salt) would be followed by 50 miles or more of the worst road you’ve ever seen. The reason the road was so bad could vary, of course, but I found the most challenging to be the loose rock sections, with mud being a close second. Fist-size stones blanketing the route proved to be a near unmanageable wrestling match between man and machine. Ruts worn into the loose stone track added an extra layer of difficulty. If you took your eyes off the road for even a moment and caught the edge of one of these ruts, you would quickly find yourself sliding sideways down the road, fighting to keep the bike upright and get back into your track of choice. Choosing the path to the far right was always the right choice to allow room for the occasional passing truck carrying a plume of dust in its wake so thick you had to come to a complete stop to wait for visibility to return. These dust clouds were so thick that visibility would drop to nearly 10 feet. Think these conditions sound bad? Let’s talk about the mud.

We had been warned many times that

rain would be our worst enemy, and the warnings proved accurate. It was on our second day that we found ourselves staring headlong into what appeared to be a sizable storm system. Dark clouds veiled the sky, and strong winds battered the surrounding trees. Bolts of lighting reached the soil not far from where we stood. With no choice but to carry on, we braced ourselves for the worst. As expected, the falling skies turned what would have otherwise been a relatively easy section of road into a slicker than snot mud bog. The sticky top layer flung itself and stuck itself to everything. The slippery bottom layer made it nearly impossible to keep the bikes upright. We both took our turn dropping our motorcycles in an effort to maintain forward progress and spent some time clearing the muck from between our tires and fenders. Progress was slow, dirty, and exhausting but progress was made nevertheless.

It was moments like these that I think we both secretly wanted. The challenges of rocks, mud, sand, river crossings, and exposure to the elements. The higher the difficulty and risk, the higher the reward and sense of accomplishment. A person doesn’t embark on an adventure such as this because it is easy. They embark on a challenge such as this for precisely the opposite. Had we found optimal conditions, I think we both would have been disappointed, wishing we

had been pushed seven days. Each day ranging from 15-18 hours of gut-punching challenges. One monumental challenge was accepted and accomplished.

Reaching Magadan was a little bittersweet. It marked the end of a 9-month 32,000-mile journey around the globe, leaving me feeling a bit sad yet laced with an overwhelming sense of accomplishment. I would spend a few days in this Far East port town preparing my motorcycle for shipment to Manzanillo, Mexico, where I will fly to retrieve it in a matter of weeks. From Manzanillo, I will meander my way back north and eventually pull into my driveway in Longmont, Colorado, where this adventure began. It will be at that point that the ride will officially come to an end, and planning for the next adventure will begin. To everyone who supported me throughout this endeavor, I want you to know that I greatly appreciate it, thank you. The number of people that opened their doors to me, fed me, or helped in some other way to make this all possible is staggering and a testament to the kindness of humankind in all parts of the world.

For more photos, follow me on Instagram @travelingchopper

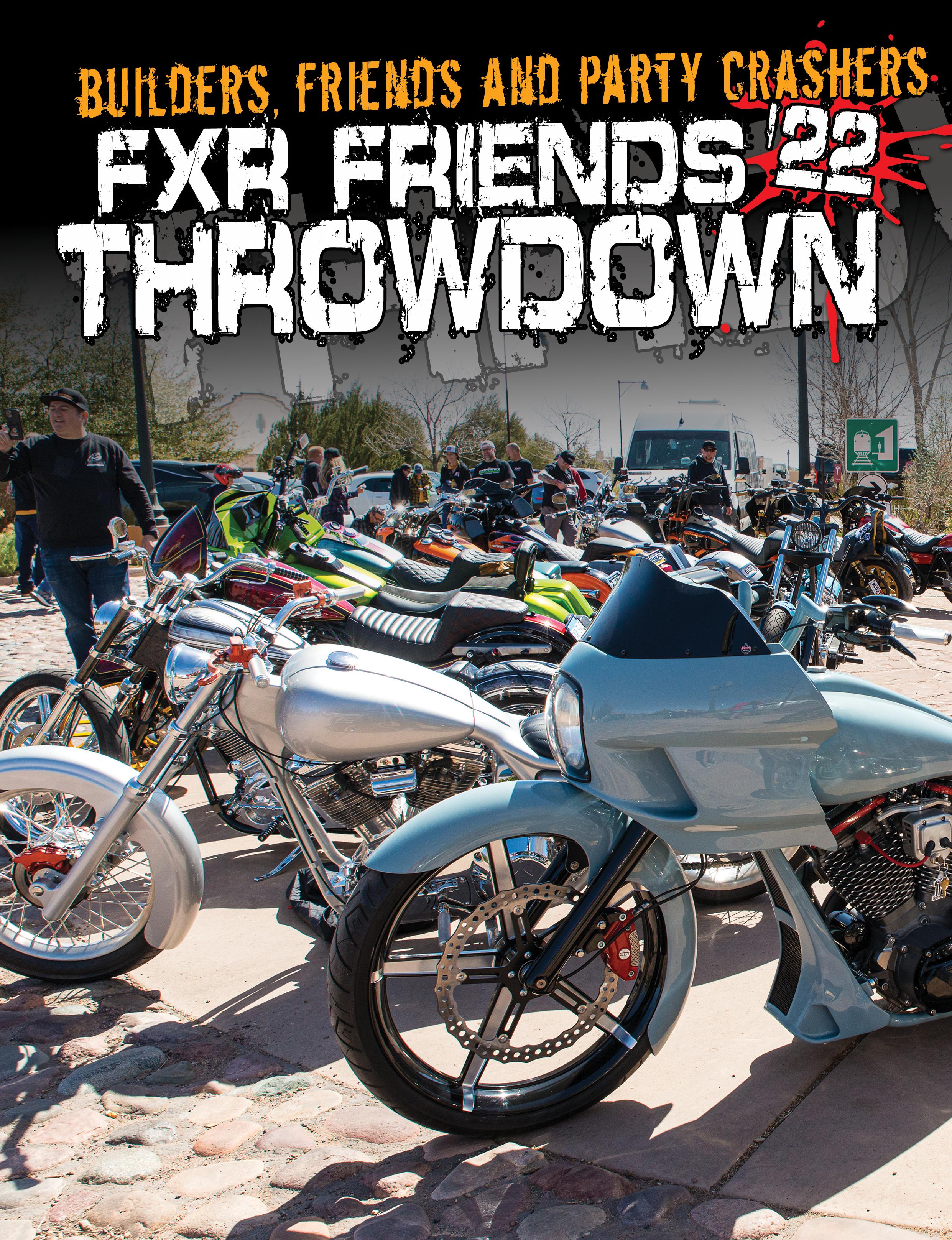

ason Mook is one of those builders who has gone about the business of motorcycles for so long now that you forget that he’s a part-time prizefighter. I don’t mean that in the literal sense but more in the way of his approach to the work. He goes to the gym, or shop in this case, day in and day out, trains, eats right, practices, and gets ready for the next fight, no matter if it is an amateur trying to improve their ranking or the special times when he gets on a major ticket. The story of the FXR Friends Throwdown was that major ticket, and you can read all about that in this same issue, but here and now, let’s take a look at the bike that started it all and the man who built it.

Like most of us, Jason started his love affair for customizing and

jwrenching on bikes in a little shop at his house. A two-car detached garage where he had a mini lathe, a selection of tools, a welder, and a couple lift tables. This was back when he lived in the Virginia Beach area, which seems a million miles away from the life he has made for himself in Deadwood, SD, but from humble beginnings, as they say… In any event, somewhere in that time, a friend convinced Jason to

Article By: Chris Callen Photos By: Melissa DeBord