COVID-19 and the heart

CORONAVIRUS DISEASE Q & A

Justin Trivax, M.D. Staff Interventional Cardiologist Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak

Without available data, public health officials offered the only method known to “flatten the curve” − strict social isolation. And it began − our new normal. Schools were closed. Restaurants were shut down. Social distancing and masks were mandated. Office visits transitioned from examining and engaging with patients to exploring the world of telemedicine and the annoyances of echoing, lagging, pausing, and troubleshooting. But just as we learned how to deal with the office visits, we have all started to understand that this will be the new norm as the virus continues to restrict our lives. Considerable unknowns regarding how to test, when to test, and which way to test patients, treatment of the virus using pharmaceuticals without robust efficacy data, and how to manage the consequences of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19), only rubbed salt in the proverbial COVID-19 wound. While there are still many questions about the future of COVID-19, over the course of the last year, our knowledge regarding the disease has increased exponentially, particularly regarding the cardiovascular system. Since March 2020, I have chronicled some of the questions I’ve fielded about COVID-19, cardiovascular disease, treatment options and vaccines. These include:

Q: “Am I at high risk for getting COVID-19?”

in public to limit the spread of respiratory droplets when coughing, sneezing, or talking. Hand-washing and good overall hygiene are also paramount to decreasing the spread of COVID-19. The only way to avoid contracting the virus is to avoid others by strict isolation which may be recommended for patients who are at highest risk for getting sick if they contract the virus.

Q: “Am I at high risk for getting sick with COVID-19?”

A: Many non-cardiac conditions increase the risk for severe illness when diagnosed with COVID-19, including morbid obesity, cancer, chronic kidney disease, immunocompromised state (on steroids or chemotherapy), diabetes mellitus and current smokers. With regard to cardiovascular-specific conditions, patients with heart failure (weakened heart muscle function) and coronary artery disease (heart attack, prior coronary artery stents or prior bypass surgery) are at higher risk for severe illness if hospitalized, with a two-fold increase in mortality.

Q: “I have atrial fibrillation. Does this increase my risk of getting sick from COVID-19?”

A: Over six million people in the United States have an

(continued on page 2)

INSIDE THIS ISSUE From Beaumont Physicians and Allied Health Professionals W inter Issue 2020

A: There are limited data demonstrating that any group of individuals is at an increased risk for contracting the virus. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends everyone wear facial coverings or masks COVID-19 and the heart 1 The anxiety and cardiovascular disease connection 4 Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: A potential ......... 5 heart attack trigger in young women Cardiac MRI: A new look into your heart ..................... 6 Common Q & A ............................................... 7

COVID-19 and the heart

(continued from page 1)

abnormal heart rhythm called atrial fibrillation, which is treated with blood thinners to prevent stroke. While there are no data suggesting increased risk from atrial fibrillation alone, abnormal heart rhythms are a common manifestation of COVID-19. Patients with atrial fibrillation should remain on all of their prescribed medications to prevent complications, including stroke.

Q: “My friend told me that she developed broken heart syndrome from COVID-19. What is this condition?”

A: Stress-induced cardiomyopathy, often referred to as broken-heart syndrome, occurs during times of significant emotional or physical stress. For reasons unknown,

Broken-heart syndrome is reversible with appropriate medical therapy –with no lasting heart damage, but beware, it tends to recur in onethird of patients if faced with a similar degree of stress.

Q: “Can COVID-19 injure the heart muscle?”

women over 50 are particularly susceptible to this condition.

COVID-19 infection is certainly a time where there is a significant adrenaline surge and hormonal changes which may result in a weakening of the heart muscle. Patients typically present with signs and symptoms of a heart attack and the diagnosis of broken-heart syndrome is made by excluding blockages in the heart arteries during a cardiac catheterization.

A: There are three different types of heart injury associated with COVID-19. The first is related directly to the arteries supplying blood to the heart. During a severe infection, levels of inflammation increase resulting in a collapsing of the major coronary arteries, irritation of the walls inside of the artery, and clotting inside of the arteries. These blood clots can completely block blood flow to the heart muscle. Symptomatic patients present with a heart attack and are typically taken emergently to the cardiac catheterization laboratory to open the collapsed artery; however, outcomes are generally poor due to the intense cascade of inflammation and clotting. The second mechanism is due to a supply-demand mismatch. With low oxygen levels, increased heart rates and higher metabolic demands, the heart is simply over-worked. This is treated by improving oxygen levels (with oxygen), hydration, and tempering the virus. Diagnosis is often made with blood tests and is seen commonly in patients with severe disease. The third type of heart injury associated with COVID-19 is direct infiltration or invasion of the virus into the heart muscle. This may lead to a weakened, stiff, and/or dilated heart muscle. Patients can be symptomatic with heart failure or have no symptoms at all. This diagnosis is typically made by cardiac ultrasound (echocardiogram) or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.

Q: “What is long-COVID?”

A : Most people recover from COVID-19 with fatigue and shortness of breath for a few weeks after the acute infection, which eventually resolves. Unfortunately, a small percentage of patients experience crippling fatigue, debilitating chest pain, shortness of breath, depression, joint pain, headaches, and difficulty with mentation and concentration several weeks after the acute phase of the viral syndrome. This has been coined, “long-COVID,” and the reasons why some people have this post-viral syndrome and others do not remain unclear. There is no specific treatment for this syndrome, nor do we know what the long-term implications may be, which oftentimes results in further anxiety and distress in this patient population.

Q: “What can I take to prevent cardiovascular complications related to COVID-19 infection?”

A: I always recommend a healthy lifestyle with a diet rich in vegetables, fruits, and whole foods. Patients should continue with standard recommendations of routine aerobic exercise with 30 minutes of moderate aerobic activity five days a week for a total of 150 minutes per week. While data regarding vitamin supplementation are not robust, (continued on next page)

2

vitamin C, vitamin D, and zinc have been gaining traction based on theoretical benefit. Vitamin C 500 mg is a potent antioxidant, reduces inflammation, and may help fight all viral infections. Vitamin D at doses of 2,000 to 5,000 IU daily may decrease the inflammatory cascade and prevent the inflammatory storm seen with severe cases. Zinc at doses of 220 mg twice daily is routinely used in hospitalized COVID-19 patients to decrease viral replication. Although none are touted as a silver bullet, data suggest that supplementing a healthy diet with these vitamins may result in less severe symptoms and shorter disease duration.

Q: “Should I get my flu shot this year?”

A: Having one pandemic is enough! A rise in both influenza and COVID-19 would certainly overwhelm our healthcare system. It is thought that the flu vaccine may not only protect against the influenza virus but may also trigger the body to produce an immune response that may fend off COVID-19. Early studies reported a relation between those who received flu shots with a lower risk of getting COVID-19. If there are no contraindications to the influenza vaccination, the CDC recommends everyone over six years of age should get a flu shot.

Q: “My son had COVID-19 in August 2020. He wants to get back to playing hockey. Is this safe?”

A: The cardiology community wants our student athletes back on the playing field, but resumption of competitive sports should require medical clearance. Decision making for diagnostic testing should always occur on a case-by-case basis. Those athletes who are symptomatic and test positive should not participate in aerobic exercise. When asymptomatic, there should be a two-week period of rest without resumption of exercise. After that time, one needs medical clearance, which would be at the discretion of the athlete’s healthcare provider. Evaluations may include office-based studies (electrocardiogram, blood work, echocardiogram) and possibly exercise stress testing for a more definitive risk assessment. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI of the heart) is the most accurate imaging modality for assessment of heart damage, scarring, or inflammation related to the virus. In a recent study (Rajpal S, JAMA Cardiology 2020), among athletes who recovered from COVID-19, 15% had cardiac MRI findings suggesting heart muscle inflammation. Certainly, for collegiate and/or professional athletes, this may be considered to understand risk of resuming strenuous exercise. For athletes returning to competitive sports living with teammates, friends, or family who had COVID-19, one may consider screening with antigen testing to determine the likelihood of asymptomatic infection as well as medical clearance prior to participation.

As we continue to navigate through this ever-changing pandemic, we must learn from our mistakes, embrace new data, and err on the conservative side. In the meantime, stay safe, protect yourself and listen to your body. An emergency is still an emergency, a heart attack is still a heart attack, and a stroke is still a stroke. Our hospital and emergency services remain ready to evaluate and treat you with open arms… and with appropriate personal protective equipment.

Impact of healthy lifestyle factors on life expectancy

According to a recent report that evaluated the impact of five lifestyle factors on life expectancy in the U.S. population, including 30 minutes per day (or more) of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, life expectancy at age 50 was 7 to 8 years greater in the most physically active cohorts of men and women.

(Source: Circulation, July 2018)

Coffee for cardiovascular protection and longevity

An increasing body of data indicates that coffee consumption is associated with dose-dependent reductions in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Coffee also reduces the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Daily consumption of 2 to 5 cups of coffee with caffeine intake up to 400 mg/day appears to be safe and is linked with the strongest beneficial effects for most health outcomes.

(Source: Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, May-June 2018)

3

PSYCHOSOCIAL ISSUES

The anxiety and cardiovascular disease connection

Daniel C. Stettner, Ph.D. LP

Licensed Psychologist Great Lakes Psychology Group

The frenetic pace of today’s modern world creates anxiety, distress, depression, and a variety of mood disorders that negatively impact our daily life and health. Moreover, this appears to be exacerbated by modern-day technologies, and the countless communications that we are bombarded with at all times of the day (and night). Accordingly, the lifetime prevalence of developing any anxiety disorder in the United States now exceeds 25 percent ( Archives of General Psychiatry, June 2005). In particular, decreased heart health and increased cardiovascular disease risk are likely outcomes when we ‘bottle up’ our emotions and feelings.

A meta-analysis of initially healthy individuals with high levels of anxiety found an elevated risk of developing heart disease and cardiac death, independent of other variables (Journal of the American College of Cardiology, June 2010). Moreover, humans are ‘hard-wired’ to experience anxiety. As past hunters and gatherers, people were highly vulnerable to danger from predators and natural disasters, so “real” or “perceived” stress instinctively set into motion emotional and hormonal changes that can adversely impact heart health, both acutely and over time.

In response to stressful situations, the body’s sympathetic nervous system becomes activated by the sudden release of specific hormones, including adrenaline and noradrenaline. This “flight or fight” response evolved as a survival mechanism, enabling individuals to react quickly to life-threatening situations. However, chronic activation of this stress cascade, without the originally intended “antidote,” that is, physical exertion (i.e., running away), is believed to take a toll on the cardiovascular system.

Patients with known cardiovascular disease are typically supported by a team of health care providers committed to helping them to reduce their risk for future cardiac events. Moreover, it appears that managing stress and anxiety is paramount to a holistic approach to optimizing cardiovascular health. Unfortunately, most stressors are situational and unavoidable. Thus, it is reasonable to ask ourselves, “How can I become a better ‘stress manager’ to protect my health?” Fortunately, several proven strategies can help you manage your psychologic and emotional responses to stressful situations to mitigate the potential negative impact on your cardiovascular well-being.

STRATEGY 1: Be mindful about handling anxiety

Consider the following strategies to manage anxiety, embrace self-care and adopt conflict management:

• Taking good care of oneself is not being selfish –rather, it is self-care.

• Avoiding an anxiety-evoking concern or person typically makes us even more uncomfortable over time. Conversely, addressing it directly encourages self-advocacy and issue resolution.

• Being assertive is not synonymous with aggression.

• This is your life. If you don’t work on managing it better, who will do it for you?

STRATEGY 2: Plan ahead

Routinely reflect on these questions to facilitate a more proactive approach to stress management:

• What is coming up in the week ahead that may evoke stress?

• What do you need to do to feel more comfortable about these issue(s)?

• What could you do to be more assertive about addressing the issue(s)?

• Who is the person that you need to deal with in handling the stress? What is the best way to approach him/her? (continued on page 8)

4

FROM THE EDITOR FROM THE CHIEF Simon R. Dixon, MBChB Chair, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine; Professor, OUWB School of Medicine Dorothy Susan Timmis Endowed Chair of Cardiology

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: A potential heart attack trigger in young women

As she walked to the parking lot after her nursing shift, “Sue” started to experience chest pain and dizziness. She was otherwise in good health so these symptoms were clearly abnormal. In the emergency room an electrocardiogram showed signs of an acute heart attack. Sue underwent emergency heart catheterization which revealed total blockage of the left anterior descending coronary artery, an artery supplying the front of the heart muscle with blood and oxygen. However, there was absolutely no evidence of plaque build-up (atherosclerosis) in the heart. So, what caused Sue’s heart attack?

Sue’s cardiac event was caused by a condition called spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD), in which bleeding occurs within the wall of the coronary artery causing compression of the true channel. Sometimes a tear is also seen affecting the inner lining of the artery. Although SCAD is much less common than heart attacks caused by atherosclerosis, the condition is not as uncommon as originally thought. Most cases occur in young women (average age 42 years) without risk factors for heart disease. The condition is more common in the first few weeks after childbirth and may also be triggered by intense exercise or emotional stress. Fibromuscular dysplasia, a non-atherosclerotic and non-inflammatory disease of the arterial walls, has been associated with the occurrence of SCAD. Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion.

Most patients can be managed with medications alone, although a stent may be required in severe cases to restore blood flow to the heart muscle.

Cardiac catheterization is the best test to confirm the diagnosis of SCAD and typically shows narrowing in the downstream (distal) part of the coronary artery. Most patients can be managed with medications alone, although a stent may be required in severe cases to restore blood flow to the heart muscle. The good news is that most cases of SCAD will heal completely within a few weeks. Medically supervised cardiac rehabilitation with a conservative, moderate intensity exercise program is strongly encouraged in these patients. Close longterm follow up with a cardiologist is also recommended, as several studies have reported SCAD recurrence rates of 5 to 15 percent across a median follow-up ranging from 22 to 54 months (European Heart Journal, Sept. 2018).

So how is Sue today?

With the accurate immediate diagnosis, care plan and follow-up, Sue recovered well after her heart attack and was able to return to work within a few weeks. She subsequently had magnetic resonance imaging scans of her brain, neck and kidney arteries to identify other abnormalities of blood vessels and connective tissue diseases that may be associated with SCAD. She has maintained a healthy heart lifestyle, including regular exercise, and continues to do well 12 years after her cardiac event.

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD)

5

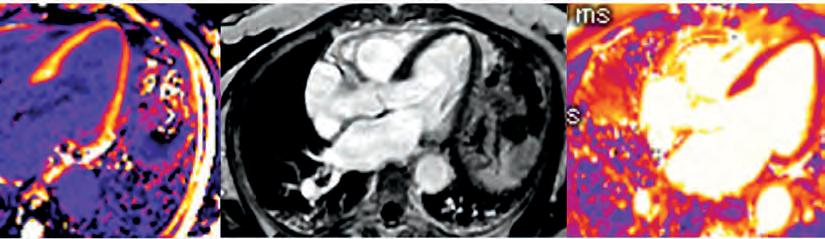

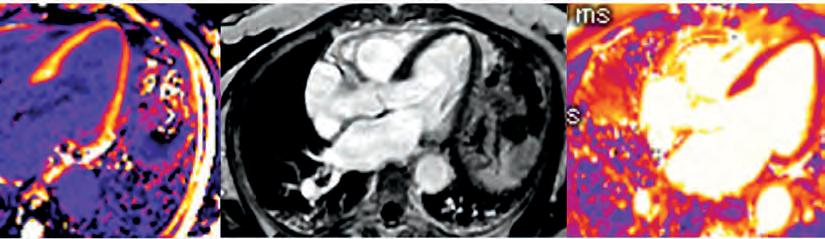

Cardiac MRI: A new look into your heart

Elvis Cami, M.D. Staff Cardiologist Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak

Cardiologists use varied noninvasive tests to study the structure and function of the heart muscle. One invaluable test, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), produces detailed images of the beating heart and major blood vessels that connect to it. This test helps cardiologists diagnose a wide range of conditions, including congenital heart defects, coronary artery disease, damage from a heart attack, heart failure, valvular heart disease, heart tumors, and diseases of the heart muscle and pericardium, the membrane surrounding the heart.

patient for therapy like valve replacement surgery at the appropriate time.

A key strength of cardiac MRI is tissue characterization, which enables cardiologists to see if there is any scarring or swelling of the heart muscle, inflammation, or infiltration. It’s like a virtual biopsy of the heart, but with pictures! In patients with coronary artery disease, for example, an MRI can help predict how much cardiac muscle scar tissue there is and how the heart will respond to treatments like coronary artery stenting or bypass surgery.

Cardiac MRI is widely accepted as the standard for evaluating

How Cardiac MRI Works

Why Have a Cardiac MRI?

Cardiac MRI technology is ideal for patients complaining of shortness of breath, chest pain, or both, often with a significant family history of heart disease. For example, while an echocardiogram of the heart can reveal a ‘leaky’ heart valve, an MRI can precisely identify and measure the severity of the leaky valve in milliliters per heartbeat, enabling cardiologists to refer the

pump function and can help determine the underlying cause of heart failure (JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, Oct. 2017). Moreover, cardiac MRI is useful for diagnosing cardiac amyloidosis, a disease causing malfunctioning proteins to accumulate in the heart muscle, without performing a heart muscle biopsy. This can facilitate a rapid diagnosis and more immediate treatment.

Cardiac MRI uses a large magnet, radio waves, and a computer to generate two- and threedimensional images of the heart without exposing patients to ionizing radiation like X-ray or CT (computed tomography). As such, there are no risks associated with having an MRI and very few side effects. During a cardiac MRI, the patient lies on a table while images are acquired. The MRI machine emits loud noises as it takes pictures of the heart; however, this is completely safe. Patients are asked to hold their breath periodically for 5-to-15 seconds while images of the heart are obtained. This ensures that the heart does not move within the chest during imaging, which normally happens as the lungs inflate and deflate with each breath. Sometimes a contrast agent containing gadolinium is required during the exam to better visualize the blood vessels and heart muscle. Gadolinium is safe to use, but for patients who have kidney disease or are on dialysis, it is recommended that they discuss it with their nephrologist first.

Special Considerations

Some patients may feel claustrophobic inside the MRI machine. Specialized glasses can help and are provided by the MRI technicians on the day of the test. Anti-anxiety medications may also help with claustrophobia; however, patients (continued on next page)

6 CLINICAL

CARDIOLOGY

Robert N. Levin, M.D. Staff Cardiologist Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak

Q:I have diabetes. I saw an ad on TV for a drug called “Ozempic,” stating that the drug lowers heart disease risk in people with diabetes. Is this true?

A:There is now ample evidence that this class of drugs, known as glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues (GLT-1), decreases the risk of cardiovascular death, nonfatal heart attacks, and nonfatal strokes in diabetics

(SUSTAIN-6 Clinical Trial:Gov). Ozempic, or semaglutide, is a GLT-1 approved for treating Type II diabetes. The drug is injected under the skin once weekly; an oral (pill) version was also recently developed,

and can be taken once daily (Pioneer-6; New England Journal of Medicine, Aug. 2019). Other drugs in this class include liraglutide (Victoza), albiglutide (Tanzeum), and dulaglutide (Trulicity). In a recent outcomes trial, patients treated with GLT-1 had a 26 percent lower risk of death, heart attack, and stroke. Of note, most patients in this trial were also receiving blood pressure medications, cholesterol medications, and antiplatelet agents to concomitantly optimize other risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Side effects of this class of drugs include gastrointestinal disorders, such as possible pancreatitis, high levels of pancreatic enzymes known as lipase and amylase, an increase in heart rate, and possible worsening of diabetic retinopathy.

Cardiac MRI: A new look into your heart

(continued from page 6)

need to remain awake during the test to follow the technician’s instructions. If anti-anxiety medications are taken, transportation home should be arranged. The test typically lasts 45 minutes, whereas a more comprehensive test like stress cardiac MRI lasts about 60 minutes.

For patients that have a pacemaker or other metallic body implant, an MRI may not be the best test, as these devices can distort image quality. However, with advances in technology, cardiac MRIs can now be performed safely in many patients with pacemakers and defibrillators. Furthermore, most implants used today are considered MRI safe or MRI compatible. Patients that have an upcoming implant procedure (i.e., bone implant, neurosurgical implant, etc.) should ask their physician if it will be MRI compatible.

Cardiac MRI complements a wide selection of other imaging technologies available at Beaumont to evaluate the structure and function of the heart, including echocardiography, cardiac CT, fractional flow reserve derived from CT, myocardial perfusion imaging and positron emission tomography, or PET scans. When it comes to diagnosing heart disease and identifying treatment options, your cardiology team will help determine if cardiac MRI is the right test for you.

As always, it is recommended you speak with your health care provider regarding an optimal medication regimen for you. It is likely that there will be additional GLT-1 drugs in the future, considering the escalating size of the “market” comprised of Americans with Type II diabetes at elevated risk for heart disease.

Dog owners live longer after a cardiovascular event

In an 11-year study, compared with people who did not own a dog, dog owners had a 21 percent and 18 percent lower risk of dying after a heart attack or stroke, respectively. However, dog owners living alone fared even better. They were about 30 percent less likely to die after either cardiovascular event than non-dog owners living alone.

(Source: Bottom Line Health, Jan. 2020)

COMMON Q & A

7

The anxiety and cardiovascular disease connection

(continued from page 4)

• What is the particular problem that you must address?

• When is the best time to address the particular issue most effectively?

• Why are you anticipating an issue to be a source of anxiety?

• Where is this particular issue or problem going to be?

STRATEGY 3: Implement change

Use these tactics to enable needed change:

• Be assertive but respectful during issue resolution.

• Set deadlines for implementation and write them down, including identifying what the beginning, middle and end of the change process will look like.

• Rehearse what you will do to help you feel more in control.

• Take written notes to help you remember important details.

STRATEGY 4: Assessing the outcome

Finally, it is important to reflect back on the implemented change to gauge success and learn:

• Was your approach to the anxiety-evoking issue/person successful?

• What could you have done differently?

• What feedback did you receive from others about the change process and outcomes?

• What can you apply to new or similar situations in the future?

Our future health is directly impacted by how we think, feel and act TODAY. Making a focused, mindful effort to proactively manage stress facilitates issue resolution, improves communication, reduces anxiety and results in more productive relationships. The next move is yours – make a positive change today!

Invasive vs. conservative medical management for heart disease

According to recently presented data from the ISCHEMIA trial, selected patients with stable ischemic heart disease who were randomized to cardiac catheterization followed by coronary revascularization versus a conservative strategy with cardiac catheterization if there was failure of optimal medical therapy demonstrated similar cardiovascular outcomes over a 3.3 year follow-up. (Source: New England Journal of Medicine, April 2020)

STATE OF THE HEART LINE-UP

Editor-in-chief: Barry Franklin, Ph.D.

Co-editor: Simon Dixon, MBChB

Associate editor: Robert Levin, M.D.

Acquisition/copy editor: Jenna Brinks, M.S.

Managing editor: Brenda White

Designer: Paul Murch

PANEL OF EXPERTS

Clinical Cardiology: Aaron Berman, M.D.; Terry Bowers, M.D.; Kavitha Chinnaiyan, M.D. David Forst, M.D.; Harold Friedman, M.D.; Robert Levin, M.D.; Steven Timmis, M.D.; Daniel Walsh, M.D.

Interventional Cardiology:

William Devlin, M.D.; Abdul Halabi, M.D.; Phillip Kraft, M.D.; Steven Ajluni, M.D.; Justin Trivax, M.D.

Nursing: Anne Davis, RN

Pharmacology: Heidi Pillen, PharmD

Exercise Physiology/Fitness:

Kirk Hendrickson, M.S.; Roger Sacks, B.S.

Geriatrics: Cindy Haskin-Popp, M.S.

Psychosocial Issues: Dan Stettner, Ph.D.; Gene Ebner, Ph.D.

Electrophysiology: David Haines, M.D.

Cardiovascular Surgery: Frank Shannon, M.D.

Obesity, Diabetes, Metabolism: Wendy Miller, M.D.; Kerstyn Zalesin, M.D.

Enhanced External Counterpulsation Therapy: Kerstin Grafe, M.S.; Joyce Said, M.S.

Women’s Issues: Pamela Marcovitz, M.D.; Melissa Stevens, M.D.

To receive the State of the Heart e-newsletter, opt in at beaumont.org/heart

8