CLARITAS

A JOURNAL OF CHRISTIAN THOUGHT

Why Isn’t Learning Fun Anymore?

Defying the Data

Lessons in Water: A Manual, or, How to Keep from Drowning: A Memoir

is the Latin word for “clarity,” “vividness,” or “renown.” For us, Claritas represents a life-giving truth that can only be found through God.

Cornell Claritas is a Christian thought journal that reviews ideas and cultural commentary. Launched in the spring semester of 2015, it is written and produced by students attending Cornell University. Cornell Claritas is ecumenical, drawing writers and editors from all denominations around a common creedal vision. Its vision is to articulate and connect the truth of Christ to every person and every study, and it strives to begin conversations that involve faith, reason, and vocation.

Cornell is not a place that prides itself much on mystery. In fact, much of the school’s branding revolves around its ability to vanquish mysteries.

“Cornell researchers solve mystery of mass turtle die-off,” reads the headline of a veterinary school promotional article. [1] “Cornell is one of the few institutions in the world with the range of expertise and depth of commitment necessary to address the issues facing our world today,” the University wrote in a blurb for its newest fundraising campaign. [2]

The Christian view of mystery is much different from the dominant one at Cornell. A prayer often recited by Catholics and Anglicans before communion goes, “The mystery of faith: Christ has died, Christ has risen, Christ will come again.” That is, the central tenet of Christian belief is a mystery. This is radically different from how Cornell tends to view knowledge. Can you imagine Professor Thomas stepping onstage in Bailey Hall and saying, “Behold, the mystery of microeconomics …?”

This doesn’t mean Christians shy away from science. At dinner with the Claritas staff, Praveen Sethupathy, a Christian professor at Cornell, said discovery is beautiful, but a mystery is a “sacred secret.” We should learn about the created world, but some things, like the sacrament of communion or what happens after we die, cannot be understood through double blind trials.

And in a Cornell context, we miss out when we neglect mystery. Cornellians have built instruments to detect water on other planets, but finding life in the cosmos can’t tell us the meaning behind them. [3] Discovery without a belief in mystery can rip the enchantment out of creation—the sentiment echoed in Walt Whitman’s poem where the speaker leaves an astronomy lecture to look up in silence at the stars. [4]

On November 3, 1997, bleary-eyed Cornellians walking to their morning classes squinted at McGraw Tower, where a pumpkin had been speared on the clock tower’s pointy top overnight. It took months for drone-wielding undergrads to confirm the pumpkin was even a pumpkin, and how the pumpkin got there remains a mystery. [5] I find the pumpkin story symbolically rich—for months, Cornellians were confronted with a reality they couldn’t explain every time they gazed upward.

I hope our scribbles on these pages make you think about things you cannot fully understand. And I hope our poems and essays help you “gaze upward” to a truth no pumpkin can—that behind all these mysteries is a God beautifully at work.

[1] “Conservation CSI: Cornell researchers solve mystery of mass turtle die-off,” Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, 2017. https://www.vet.cornell.edu/ news/20170306/conservation-csi-cornell-researchers-solve-mystery-mass-turtle-die

[2] “About the Campaign,” To Do the Greatest Good: The Campaign for Cornell University. https://greatestgood.cornell.edu/about/

[3] Tyagi, Srishti, “Cornell Astronomers Developed Instrument for Discovery of Water on Sunlit Moon,” Cornell Daily Sun. https://cornellsun.com/2020/12/09/cornell-astronomers-developed-instrument-for-discovery-of-water-on-sunlit-moon/

[4] Whitman, Walt, “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer,” 1867.

[5] Friedladner, Blaine, “Pumpkin prank perpetrator puzzle persists 20 years later,” Cornell Chronicle. https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2017/10/pumpkin-prank-perpetrator-puzzle-persists-20-years-later

Why Isn’t Learning Fun Anymore?

Annina Bradley rekindling my dormant curiosity by knowing God’s character

הרוח הקודש Hannah Master ruach ha-kodesh (the Holy Spirit)

Life, Death, and Dirty Dishes David Johnson escaping our apathy towards life’s struggles

It Takes Three to Tango the Trinitarian basis for true friendship

Christopher Ho Kim

The Face of Faith Jeffrey Huang

For Time to Stand Still Eliana Amoh leaning on God in the face of distress Will This Be on the Final?

Joaquin Rivera why the Bible is relevant for our stressful lives

A Los Cielos Mi Alma Vieja Matt Pang to the heavens is my old soul’s fate

Get Off Your Freaking Phone: The Definitive Answer to the Problem of Suffering

Frank Fang

Shrouded in Mist overcoming anxiety for an uncertain future Maximilian Yap

Defying the Data how I found God after being raised in America’s most secular city Seika Brown

Hidden Michelle Liu

Lessons in Water: A Manual, or, How to Keep from Drowning: A Memoir Nate Lo

When I was young, I ran on the playground with my shoes untied. I raced raindrops on car windows and watched ants carrying crumbs with amazement. I wanted to know why the grass became damp with morning dew—why the stars burned like little fires in the sky. No question was too big to ask, no mystery too great to ponder.

By high school, however, my childlike wonder had dwindled. Pursuing knowledge became sitting at a desk with a textbook and pencil in hand— scribbling answers and dusting away eraser shreds. If I put the time and effort in, I’d succeed on an exam. I’d check off a box. I happily set goals and achieved them, but was no longer so easily entranced by the intricacies of the universe.

Entering college, I felt myself moving further from my once-unquenchable curiosity. Still uncertain about what I wanted to study, I felt an urgency. My investment in knowledge turned financial. Instead of experiencing the joy and gratitude that comes with the privilege of learning, I became preoccupied with questions about my future career path and purpose. Taking classes began to feel like trying on clothes. What fits nicely? I sensed that whatever major I committed myself to would be an all-encapsulating, binding identity.

Taking classes began to feel like trying on clothes. What fits nicely?

I wasn’t alone feeling this way. The Cornell student body enters campus with diverse intellectual interests, attracted by the words “Any person, any study,” and departs mostly filling jobs in finance and consulting. Most Ivy League universities follow this trend. [1] An increasing number of students are abandoning their unique aspirations to instead find comfort in financial stability and well-respected careers.

Over the course of a short decade, my own purpose for gaining knowledge had shifted from a genuine love of discovery to a preoccupation with my own security and self-fulfillment. Internally, I longed to learn for an end that wasn’t material. I hadn’t yet recognized that the pursuit of knowledge could be abstract—that by changing the posture of my heart, the ways in which I absorbed new information could be enhanced.

According to Saint Augustine, whose desire for knowledge was insatiable, what one loves impacts one’s knowledge and understanding. [2] From a Christian

perspective, rightly-ordered “loves” can illuminate greater understanding. A love for God strengthens our desire to pursue knowledge by sparking within us an all-consuming desire to understand Him and become acquainted with His character. Because we believe God to be the creator through and for which all things were made, a love for God naturally translates to a desire to understand the greater mechanisms of the universe. [3]

A recent sermon I listened to spoke precisely to this idea. [4] There is an owner of gravity. A creator of thermodynamics. An author of languages. If God’s character is embedded in the physical laws of motion, the design of chemical molecules, and revealed in the syntax of literature, then seeking to understand all the complexity that surrounds us means interacting with His glory. This may seem lofty when you’re studying organic chemistry at 2 AM, and all you can think about is how your laptop keyboard would make a very comfortable pillow. But the point is, when we consider the intricate and intentional design of our world, we no longer flip through textbook pages apathetically, but instead hunger for understanding.

If God’s character is embedded in the physical laws of motion, the design of chemical molecules, and revealed in the syntax of literature, then seeking to understand all the complexity that surrounds us means interacting with His glory.

Additionally, possessing a knowledge of God calls us to abandon any identity founded in a declared major or scholarliness. Instead, we are welcomed into a new identity as followers of Christ, forever unchained from needing to worry about educational achievements or the merit of our future careers. In the Gospel of Matthew, God rhetorically

Annina Bradley | rekindling my dormant curiosity by knowing God’s character

Annina Bradley | rekindling my dormant curiosity by knowing God’s character

asks why we worry, turning our eyes to beauty in nature: “And why do you worry about clothes? See how the flowers of the field grow… If that is how God clothes the grass of the field, which is here today and tomorrow is thrown into the fire, will he not much more clothe you – you of little faith?” [5]

Re-focusing my attention on God’s promises and steadfastness grants me a freedom to learn without anxiously dwelling on how covered content might practically serve me in the future. As I still stand at a crossroads of intellectual development and embark on the years of college ahead of me, I find comfort knowing that I don’t have to have my life fully mapped out. It has already been carefully crafted, etched into time by my creator.

Now, the rhythm of life—hustle and bustle with nothing but a protein bar for breakfast-type days—can make it so easy to get swept away by all of the things that deceptively promise to sustain us; stable careers and flow-chart plans might keep us afloat. It takes courage to live life as we are called to in Romans 12:2. “Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind.” [6] If we aim to live set apart, God promises to change the lens through which we view the world, fundamentally transforming our priorities and the way we think. All of our pursuits, including that of knowledge, become ignited with purpose.

I return to the image of my younger self—frantically curious, turning over river rocks and building castles in the sand. Today, when I step outside, surrounded by trees ablaze with fiery color, my wonder is sparked with reason. For there exists a God who wrote the very laws that allow the sun to set and rise again. Knowing Him compels me to seek an understanding of the world He created in order to better steward it.

Certainly, not every moment of my education will be pure fascination and enlightenment, sunshine and sitting on benches with a good book and a perfect breeze. Mid-term season will come with its anxieties; long readings and problem sets might still bring dread.

Yet, standing upon this hilltop of vast opportunity, I can daily reflect on the privilege it is to receive a formative education. When a seminar discussion carries on after class or a complex topic finally clicks, something of God’s character might just be revealed.

“Almost our whole education has been directed to silencing this shy, persistent, inner voice” C.S Lewis wrote. [7] If all of us maintain an innate desire to learn and discover, let us louden the inner voice Lewis speaks of and let curiosity fuel our academic interactions. Let this voice reverberate across campus like the McGraw Tower chimes, transforming the way we collectively pursue knowledge.

Annina Bradley is a first-year from Boise, ID presently studying Government and French. Any time you might find her exploring trails, consuming delicious food, making aesthetic Spotify playlists, or studying outside if it’s above freezing. She commonly publicizes that Idaho is more than just the potato state.

[1] “Outcomes: Careers after Cornell.” College of Arts & Sciences.

[2] Augustinus, A. De Trinitate IX - X. (Circa AD 400).

[3] Colossians 1:16, (NIV)

[4] Muñoz, Isaís. Pastor at Grace Community Church. Cornell Class of ‘15.

[5] Matthew 6:28-30, (NIV)

[6] Romans 12:2, (NIV)

[7] Lewis, C.S. The Weight of Glory and Other Addresses, 1941.

Today, when I step outside, surrounded by trees ablaze with fiery color, my wonder is sparked with reason. For there exists a God who wrote the very laws that allow the sun to set and rise again.

The low kettle gurgles under plump evening sun

As I prepare a cup of comfort, And tongues of the steam follow To my final place of rest, Smooth mug of soft tea.

Then as I sit upon my rest

The draft sets upon me, Rustling curtains and Nipping at fingertips, Incessantly reminding me of my weakness.

I stared then at the dancing drapes Befuddled that they could betray me, For were they not cowering from the very purpose For which they were made? Why, oh God, can this cool breeze reject it so?

And so I pondered the drapes— What a thing they were to taunt me: Made for simple purpose To bring respite in daytime. But now they else greet wind, celebrating its arrival.

With raucous abandon they dance Taking gusted shape; Do they not abandon their post? Does the sun not revel In their naked unwitting sculpture?

Would that I could be— For Lord, what purpose do I serve Here in this quiet; To whom do I bring respite? To whom am I so attuned to greet?

For that is the higher good, Is it not so?

That such drapes were meant to only cover The barren from heat; Then to shirk such purpose for the wind.

For surely these drapes were cut clear Made for their purpose Why can it not be for me, oh Lord? How can even they lay aside their shade For the vanity of wind?

And in this moment my cup overfloweth And the Spirit of God came upon me;

Hot tea splashed on my lap and The sweet steam startled my nose.

And the tongues spoke A lilt in my ear, “Smell the drape-thru wind; The sun will yet meet shade. Shudder not my invitation.”

I maneuvered through the dense crowd in Barton Hall, barely managing to reach my group of friends at the front of the stage. Although I had never heard of lovelytheband or Indigo De Souza, I resolved to make the most of my firstever Cornell homecoming concert. The lights came up, and De Souza began to play.

“Dirty the dishes, stack them higher We’re not gonna wash them, we’ll throw them away”

Okay—I get it. Who likes doing the dishes, anyway? But then the song continued:

“Kill me, slowly, outside that diner That we like to go to When things were okay” [1]

she struggles with the inevitability of death and the seeming emptiness of life.

Now, perhaps struggle isn’t quite the right word as De Souza doesn’t seem to fear or resist death. On the contrary, she invites it (“Kill me, slowly”). However, her acceptance of death is detached from any meaningful journey or story.

In contrast to Bilbo, who welcomes death as the next step in a purposeful journey, De Souza’s acceptance of death is more aptly described as a resignation.

As a counterexample, consider the words of “Bilbo’s Last Song,” published by J.R.R. Tolkien to imagine the thoughts of Bilbo Baggins, the protagonist of The Hobbit, when he is facing death:

“Day is ended, dim my eyes, but journey long before me lies.” [2]

In contrast to Bilbo, who welcomes death as the next step in a purposeful journey, De Souza’s acceptance of death is more aptly described as a resignation, grounded in the meaninglessness of this life and whatever lies beyond it. But give her credit for innovation–her reluctant resignation stands in stark contrast to the sentiments of the vast majority of literature throughout human history.

for immortality. For a more recent example, consider Voldemort in the Harry Potter series, who splits his very soul into seven pieces, attempting to become immortal after the death of his mother. Gilgamesh, Galahad, and Voldemort cast their lot with Welsh poet Dylan Thomas:

“Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” [3]

This is what was so bizarre about the concert— it was as if students drew together to collectively relinquish the fight against suffering.

This is what is so curious about De Souza. In contrast to this rage against death, she responds with a Laodicean “lukewarmness.” [4] And this is what was so bizarre about the concert–it was as if students drew together to collectively relinquish the fight against suffering.

These lyrics from “Kill Me” illustrate what emerged as a recurring theme in De Souza’s music. In other numbers, such as “Home Team,” “Sick in the Head,” and “How I Get Myself Killed,”

The history of literature shows humans have always been scared to die, being full of stories that illustrate intense and painful emotions associated with mortality. We are afraid, and we do mind. In the 2100 BC Epic of Gilgamesh, the protagonist goes on a failed journey to achieve immortality after losing his close companion. In the same spirit, Sir Galahad’s quest for the holy grail, which became popular legend in the 13th Century AD, was a quest

Arguably, attempting to avoid death is an act of faithlessness. The characters–Gilgamesh, Galahad, and Voldemort–all experienced loss and hardship in their lives. They did not believe that God or anything outside themselves had cared for them during their life or would care for them in death. So, they took their mortality into their own hands. This impulse to not trust God’s hand in death is a perennial struggle, and one that C.S. Lewis articulates in A Grief Observed:

“They tell me H. [Lewis’s deceased wife] is happy now, they tell me she is at peace. What makes them so sure of this?….

‘Because she is in God’s Hands.’ But if so, she was in God’s hands all the time,

and I have seen what they did to her here. Do they suddenly become gentler to us the moment we are out of the body? And if so, why? If God’s goodness is inconsistent with hurting us, then either God is not good or there is no God: for in the life we know He hurts us beyond our worst fears and beyond all we can imagine. If it is consistent with hurting us, then He may hurt us after death as unendurably as before it.”

Lewis takes the characters’ philosophy to the logical extreme, even blaming God for suffering, before eventually finding catharsis:

“Sometimes it is hard not to say, ‘God forgive God.’ Sometimes it is hard to say so much. But if our faith is true, He didn’t. He crucified him.” [5]

In the end, Lewis arrives at the conviction that we do not need to resist death. Because God himself preceded us in death, he proved that he will care for us in death. However, the testimony of literature is that, for millennia, people have feared death and, therefore, frantically tried to secure their own future.

So, perhaps De Souza’s philosophy is not as novel as it initially appeared but is simply the logical extension of older ideas. Previously, we asked the question, if death is mysterious, why allow ourselves to die? While we lacked faith that we would be cared for in death, we had hope that we could find reward in continued living.

The problem of the avoidance of death has been supplanted—or rather supplemented—by the avoidance of life.

Now, we ask the hopeless question, as an anonymous post in the Cornell subreddit put it: “Why bother to live?”

[6] The problem of the avoidance of death has been supplanted—or rather supplemented—by the avoidance of life.

Carefully with the plates!

De Souza is right about this much: Dirty dishes stink. They beckon us to perform a monotonous and unrewarding task. Indeed, caring for “tomorrow” often entails suffering. But there is a better way to approach our plates than simply discarding them.

Perhaps rolling up our sleeves and leaning into the messiness of life is an act of faith, or at least an act of hope, grounded in the conviction that the sun will rise, and that we will be invited to live another day. In the Hebrew Scriptures, even God is described as setting a table for his people, and to have done so in the very presence of enemies. A set table is a symbol of hope.

This logic can be extended. When the shingles on our house are in disarray and in need of repair, they remind us that we have been given shelter. When we lament inclement weather, we are reminded of the gift of seasons, sky, and sun. Lewis, despite facing bullying in school, losing his mother to cancer, and experiencing the horrors of the second world war, was able to be “Surprised by Joy.” At Cornell, when we struggle to get our desired classes during preenroll, we are reminded of our daily opportunity to study far above Cayuga’s waters.

This is a politics of resignation—“Kill me, slowly” enshrined in law—not compassion.

Sustaining hope amidst suffering is an urgent task, even as a matter of policy. Beginning in March, 2023 Canada will expand access to “assisted dying” (formerly known as assisted suicide) to those suffering from mental illness. [7]

This is a politics of resignation—“Kill me, slowly” enshrined in law—not compassion. Compassion is telling a friend or family member who is suffering or has lost hope that we value them, we affirm their dignity, and we need them—no matter their circumstances.

[9] Tolkien, J.R.R., “The Hobbit: Bilbo comes to the Huts of the Raft-elves” 1937, The Tolkien Estate.

When we are tempted to despair, Bilbo Baggins’ faith in the future is the wisdom that we need:

“Chip the glasses and crack the plates!

That’s what Bilbo Baggins hates! So, carefully! Carefully with the plates!”

Even when life stinks, we always have choices. Resisting resignation is no simple task, but those who believe our world belongs to God can care for today and fearlessly face the future, for tomorrow already has been made secure.

David Johnson is a freshman from Ithaca, currently intent on studying Electrical and Computer Engineering. He enjoys the outdoors through running, hiking, and skiing. During inclement weather, or just “weather” as he’s come to know it, David can be found reading, playing chess, or solving all sorts of puzzles.

[1] de Souza, Indigo, “Kill Me”

[2] Tolkein, J.R.R., “Bilbo’s Last Song,” 1990.

[3] Thomas, Dylan, “Do not go gentle into that good night,” 1947.

[4] Revelation 3:14-16

[5] C.S. Lewis, A Grief Observed

[6] “What’s the point of life”, r/cornell, Reddit, 2021. https:// www.reddit.com/r/Cornell/comments/qu7gio/whats_the_point_ of_life/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

[7] Carnahan, Ashley, “Canada expanding assisted suicide law to the mentally ill,” 2022, New York Post.

[8] ‘Album art for “Any Shape You Take” (2021) by Indigo de Souza’, indigodesouza.com/home, accessed 12/4/2022.

[9] Tolkien, J.R.R., “The Hobbit: Bilbo comes to the Huts of the Raft-elves” 1937, The Tolkien Estate.

There is a dance studio on the corner of 193rd Street and 47th Avenue in my hometown of Auburndale, New York with a pink and black sign that reads “Dance Creations by Laurie.” The sign hangs above the door sagging out of old age, but the energy from inside rejuvenates the building with a constant flow of vibrance.

Every Sunday, on my way home from church, I would pass by that studio and catch glimpses of the elegant dancers. There was something about the pointe shoes, barres, and marley floors that mesmerized me week after week. And as time passed, my desire to dance grew.

I never had the courage to ask my parents for dance classes, though. The financial obligations of being a performing artist was a contributing factor to that decision, but I also felt a social pressure to not engage with something that would be considered non-masculine. So I kept the chambers to my burning desire creaked open with the hope that the little oxygen I secretly gave it would keep it alive. But at the beginning of high school, that door shut.

My high school had “afternoon options” where students were able to choose how they wanted to spend two hours of every weekday, whether it be sports or some other activity. And because most of the school was a part of some team sport, I felt obligated to do one as well. But that was when my friend Avery* convinced me otherwise.

Avery was a cross-country runner whose dad was the head coach of the varsity soccer program. He was by all means an athlete. So when he approached me one night with the idea of joining the dance team for the spring season of afternoon options, I was surprised. Had he known about my obsession with dance? Maybe I had mentioned it once in our many latenight conversations?

As I sat on the dusty blue couch in the common room of our dorm, I expressed my concerns to him about joining the

dance team: being labeled with stereotypes, making a fool of myself trying to learn for the first time, and the lack of men in the group to name a few. But the more I talked, the more he seemed convinced that we should do it together. Who cared about stereotypes? As long as we were confident in our identities, it wouldn’t matter. Who cared if we looked like fools? We were there to learn, and failing is a part of that journey. Who cared if there weren’t enough men? We could be the ones to bring more in. Avery encouraged me to at least try, and if I didn’t like it, I didn’t need to do it again. Through that conversation, he had opened the door in my heart and rekindled the dying embers. I ended up joining the dance program and absolutely loved it.

We became close friends that season. And as I reflected on my relationship with Avery, I realized that the reason we grew close wasn’t because we both hated and felt embarrassed in the fact that we were the only guys on the dance team. Instead, it was that we each had a love for dance, and our individual passions helped to fuel that of one another’s.

There is something very human about the ability to gather and develop relationships over shared passions or experiences—we in college especially have a tendency to do so. We bond with one another about the misery in prelims, the joy of getting a “classcancelled” email, or our collective disdain for pre-enroll. When I first came to Cornell,

I found myself asking questions about how I wanted to form my relationships. So I turned to the Bible, specifically the story of David and Jonathan, for guidance in how I sought them.

The story of David and Jonathan is one that I regard as the pinnacle of human friendship in the Old Testament. David was a shepherd boy from the town of Bethlehem who God had anointed through Samuel to become the second king of Israel. And Jonathan was the firstborn son and heir to the throne of Saul, the first king of Israel. (In fact, Saul saw David as a threat to his kingdom and wanted to kill him out of jealousy.) Despite the circumstances, David and Jonathan were both men who loved the LORD, and the LORD was with them both.

1 Samuel describes their relationship in the following way: “the soul of Jonathan was knit to the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul” [1]. The two made a covenant, and their relationship remained strong to the point where Jonathan risked his life for David in 1 Samuel 20:30-33 when David is a fugitive, running from Saul’s murderous hand. The covenant made in 1 Samuel 18:3 is shown again later on when Jonathan says, “ ‘May the LORD take vengeance on David’s enemies’ ” [2]. And they also make a covenant to look after each other’s descendants.

Then in 2 Samuel 1, David learns that Jonathan was killed in a battle against the Philistines, and he mourns the death of his beloved friend. He writes the following lamentation: “I am distressed for you, my brother Jonathan;/ very pleasant have you been to me;/ your love was extraordinary,/ surpassing the love of women” [3].

Isn’t what David wrote surprising? Queer theorists argue that the aforementioned verses are a testament to some hidden erotic love between the two. But the non-existence of Biblical evidence for any romantic love between David and Jonathan and the unlikelihood of such a relationship lead me to believe that it was nothing more than a friendship.

And that is the beauty of David and Jonathan’s relationship. They were able to

find true, deep-seated love for one another. A love so powerful and pure that causes people two millennia later to argue if they were homosexual. They were nothing but loyal to one another, each keeping their ends of the covenants they made together. Jonathan saw to it that David inherited the throne, and David looked after Jonathan’s children when Jonathan passed away.

So how did such a relationship form? It was because both men centered their lives on an eternal and divine relationship— the first and everlasting relationship in its most holy and pure form, the same relationship that actively affects our lives today, the one between God and Himself through the Trinity.

The Trinity refers to the single God who exists in three persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. The Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are not each a separate god, and God does not choose to take one form over another. Rather, they are three persons who exist in one being in perfect unity.

It is the perfect dance, the perfect relationship, where they flow in harmony each simultaneously being the leader and the follower of the dance.

The holy relationship amongst the Trinity is described in Tim Keller’s King’s Cross: The Story of the World in the Life of Jesus as the Father, the Son, and the Spirit each centering on the others, adoring and serving each other as they infinitely seek one another’s glory. “[They] are characterized in their very essence by mutually self-giving love. No person in the Trinity insists that the others revolve around him; rather each of them voluntarily circles and orbits the others” [4]. It is the perfect dance, the perfect relationship, where they flow in harmony each simultaneously being the leader and the follower of the dance. And they are able to do so because God Himself is the perfect being.

Pretend that you are at a wedding where everyone but you has been dancing all night. Your friend notices that you’ve been

sitting alone, not participating in any of the festivities. You explain to him that you don’t find joy in dancing because you’ve never danced before. You are afraid to dance in front of everyone. Regardless, he takes you by the hand and starts dancing with you. At first, you’re hesitant: you don’t know where or even what the beat is. But your friend always manages to make sure you’re having a good time, and more importantly, he doesn’t make you look like a fool. And at the end of the night, you are happy that you were able to dance with everyone else.

Likewise, when it comes to the divine dance of the Trinity, we are not to simply sit on the sidelines and be mere observers. Instead, we are to fully partake and learn the rhythms and intimacies of it—we were made to do so. More importantly, God cares about us and wants us to dance with Him. And we are to be in a constant dance with God. We are to center Him in all that we do for that will bring us true joy and happiness.

However, we are human. We are atrocious at dancing. We frequently lose our balance and get off rhythm. We mess up. But that is the beauty of being with the best dancer. God is able to catch our mistakes and pull us back in. He is able to make up for every lost step and get us back on the rhythm when we can’t hear the beat. As long as God is at the center of it all, as long as He is the one leading it all, we can trust that our dance with Him is harmonious, and we can trust that we are learning and doing the best that we can.

So how should our relationship with one another reflect our relationship with the Trinity?

As college students, we have a tendency to make a lot of our relationships selfcentered. We look to others for what they are able to provide us—help with classes, access to parties, networking connections to name a few—and others do the same to us. And when we try to center our relationships on ourselves, we are teaching one another an imperfect dance.

Think about two people tangoing. Often there is a leader who leads with subtle gestures, and there is an understanding that the follower will follow them. Together, they are able to form an elegant dance. Now, what if the leader didn’t know what they were doing? Then, there would be an inability to coordinate their movements. This is what it looks like when we try to center our relationships around us. Because we don’t know how to dance perfectly, we have an incomplete knowledge of what the dance is supposed to look like. As we try to teach others to dance, those issues are then exacerbated. However, if we all learned from the same source, the truest source, then we would be able to dance better together. And we can see this in David and Jonathan’s mutual love and passion for God resulting in their stability with one another.

To the reader, there is a conflict in David and Jonathan’s relationship, and understandably so. David is the one who God anointed to take over the throne, and Jonathan is the one who is supposed to inherit the throne. If their relationship was reflective of many of ours today, a selfcentered relationship, this conflict would have most likely resulted in a war for the throne. But because they both loved the Lord and put Him in the center of their lives, they understood God’s greater purpose. Jonathan was able to give up his right to the throne because he knew that God chose David, and he is able to admit to David in 1 Samuel 23:16, “ ‘You will be king over Israel, and I will be second to you.’ ” [5]. And that is how they formed such a strong relationship with one another. Each knew of the one true and eternal love, and it flowed from God to one another.

When we place God at the center of our lives, and when we first focus on our dance with Him, we are able to form selfsacrificing, soul-knitting, covenant-making relationships that help uplift others instead of ourselves. God is our teacher and our best dance partner. And if we acknowledge that, then all of our relationships will be closer to that of the Trinity. But, because we are not perfect, our relationships will not be perfect.

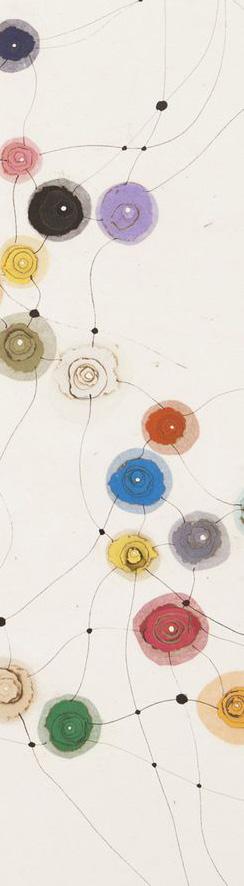

[8] Denervaud, Caroline, “Fugue” Exhibit in Lawson, Kate, “Caroline Denervaud’s Paintings Are a Dialogue Between Art and Dance” Sight Unseen, 2021.

For it is only if we are in Christ, we can show the love and mercy that God had first shown us, and we will be able to forgive just as He taught us.

There will be times when we fail to place God at the center, so we fail to uplift one another, and instead we hurt each other. In those times, we must first reenter our lives in God. For it is only if we are in Christ, we can show the love and mercy that God had first shown us, and we will be able to forgive just as He taught us.

My relationship with Avery has by no means been perfect. There were times when we hurt each other. But our mutual passion for dance helped us to keep our relationship strong. And though we no longer physically dance together, the

relationship we built from those four years is one that still lasts strongly today.

So if our relationships can be fortified through temporary passions like dance, how much stronger would they be through everlasting ones?

Christopher Ho Kim is a sophomore from Auburndale, NY majoring in Biology and Society with a double minor in Philosophy and Religious Studies. In his free time, you can find him writing and producing music, reading about theological and clinical bioethics, or enjoying musicals and plays.

*name changed for anonymity

[1] 1 Samuel 18:1 English Standard Version

[2] 1 Samuel 20:16 English Standard Version

[3] 2 Samuel 1:26 English Standard Version

[4] Keller, Timothy. King’s Cross: The Story of the World in the Life of Jesus. New York: Riverhead Books, 2011.

[5] 1 Samuel 23:16 English Standard Version

[6] Luke 17:3-4 English Standard Version

[7] Rothenstein, Ella.“The Inkblot Test”, PSYCHOBOOK 2016

[8] Denervaud, Caroline, “Fugue” Exhibit in Lawson, Kate, “Caroline Denervaud’s Paintings Are a Dialogue Between Art and Dance” Sight Unseen, 2021.

Jeffrey Huang

Jeffrey Huang

On the many-sided die, I focus on specific faces. My mind remains filled with desperate traces. Scribbles in shades of black As if the Spirit provided no truth nor slack. My brain bursts at the seams With my own dreams. I plan my time But fail to rhyme Rhythm with reason And activities to the season.

The mystery is that Scripture provides seeds of faith. When I feel the wraith Of missed chances and ghosts of joys, I plant the seeds that God employs. I relax since he sees my thoughts. I discern the truth when he connects the dots.

Jeffrey Huang is a sophomore CS major from Albany, NY who enjoys coding, taking walks, staying up-to-date on cryptocurrency and tech news, and listening to city pop music.

Jeffrey Huang is a sophomore CS major from Albany, NY who enjoys coding, taking walks, staying up-to-date on cryptocurrency and tech news, and listening to city pop music.

“I’ve got this! Is Cornell really that hard? I’m actually not as stressed out as I thought I would be!” Those were my thoughts during the first two weeks of college. The following weeks humbled me real quick as I struggled to keep up with biology problem sets and realized that my studying techniques wouldn’t only have to encompass memorization, but practical application too.

I have always juggled different tasks, and I have good time management skills, so I assumed the transition to college wouldn’t be hard. I thought I could manage a job, my social life, school work, sleep, and a relationship with Christ, but I didn’t consider that things won’t always go my way. I had a mindset of self-dependency going into Cornell, and it’s really easy to have that mindset when everything is going fine. Viewing life through this lens was easier because I had never been to college or experienced the Cornell culture. I am a

planner and often forget about my need to rely on God and His timing. The Old Testament book of Joshua analyzes this mindset and shows God’s power to interrupt our plans with mysteries and miracles.

Joshua chapter 10 starts with the inhabitants of Gibeon, an ancient Canaanite city about five miles north of Jerusalem. [1] The Gibeonites had become allies with powerful Israel and established themselves as a great city. But suddenly, they found themselves in an unfavorable situation with AdoniZedek, the king of Jerusalem, who had gathered together the five kings of the Amorites and their troops to wage war against Gibeon because they saw Gibeon’s growth as a threat. Gibeon’s fortunes changed with little warning.

Similarly, once I got to Cornell, I also found my life suddenly becoming hectic, confusing, and stressful. Things weren’t going the way I had planned them.

I realized I needed help, but I didn’t first turn to God. I tried to figure things out

on my own by seeking social validation, but I was constantly placing myself in situations and relationships that I didn’t feel comfortable in. I thought I would be able to control my narrative and eventually make things right—but all of my efforts were driven by fear. The men of Gibeon also felt fear when they rushed to Joshua to plead for help against the Amorites.

I tried to figure things out on my own by seeking social validation, but I was constantly placing myself in situations and relationships that I didn’t feel comfortable in.

I finally got to a point where I accepted that I wasn’t making progress in my effort to thrive in college. That’s when I realized that when my way doesn’t work, God’s way will. When the men of Gibeon went to Joshua for answers, Joshua sought the Lord’s advice, and the Lord most definitely came through! The Lord reassured Joshua that his army would be victorious over the Amorites.

Eliana Amoh | leaning on God in the face of distress [3] “The Moon,” 2017, National Aeronautics and Space Administration.Then the Lord allowed Joshua and his army to be victorious by putting the Amorite army in a great panic. This was a way of the Lord showing the importance of letting Him work instead of pursuing our own means. Wait, there’s more! The Lord caused a hailstorm that killed a majority of the Amorites. God then ends it all by doing the impossible. As the Lord gave the Israelites victory over the Amorites, Joshua prayed to Him in front of all the Israelites to have the sun stand still. The sun and moon then stood still until all the Amorites had been defeated.

Don’t confine yourself to your own limited timeline. Understand that God is timeless and that what He has planned for us is beyond our limitations. Throughout my college journey, I’ve allowed God to steer me in a completely different direction than I thought to the point where I am even changing my major. I’ve allowed God

to help me be patient in meeting people and developing friendships, so I feel as though I’m developing a strong support system. So, the moral of the story— trust God!

Eliana Amoh is a freshman in the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences from Maryland. In her free time she enjoys hanging out with friends and family, watching social documentaries, singing, watching basketball, or casually repping the DMV—and no she is not referring to the Department of Motor Vehicles.

[1] Joshua 10

[2] “Moon Jar,” Joseon dynasty (1392-1910), Korea, Art Institute of Chicago.

[3] “The Moon,” 2017, National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

[4] “From the Sun with Love,” 2017, National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

[5] “Rising Sun,” 1780. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

In the days before a prelim, uncertainty fills the air. The same questions get repeated again and again during lecture. “Where is the prelim at? Is there partial credit? How again do you specifically answer that really basic conceptual question so that I get maximum points?” And how about those GroupMe chats? Everyone is obsessed with categorically memorizing exactly how to deal with every type of problem.

If we expand our lens to society as a whole, this need to be constantly up to date prevails in every area. Our textbooks have over a dozen editions published to keep up with changes. Last week’s news isn’t relevant anymore. And how many NBA 2K games are there by now?

In the midst of this rapidly changing society, I look to the Bible as the foundation of my life. Yes, the Bible—a book written over a span of 1600 years, with characters including a 5th century BC Jew, a 2nd century AD Roman slave, and a 15th century BC Egyptian Pharaoh, [1] none of whom seem to resemble my circumstances in the slightest. These letters, biographies, historical accounts, poems, and prophecies have been handed down in an unaltered form for centuries. I look to the Bible for guidance in every area of my life. This book, with its most recent components being at least 1800 years old, informs how I interact with others, how I approach my work, and how I view what happens in the world around me. Although new and different translations exist, there is no Gospel of John 2022 DLC (never before seen chapters included!).

Is the Bible still relevant? Should the teachings of Jesus, a man from 2000 years ago whose teachings were directly addressed to some shepherds, craftsmen, and fishermen from a bygone Roman Empire, apply to me, a college student with 21st century problems? If God is truly omniscient and all powerful, why

couldn’t he just update his Word for our current lives, so we don’t have to keep guessing about what he would want? Yes, we have pastors, Christian books, and prayer, but why can’t God directly address and clear up the mystery about questions in my life about my career or relationships, or societal problems at large like COVID-19 or the war in Ukraine? Perhaps this is even proof that a creator does not exist, or if he does, that he does not care much for the world.

But could not this rather be cause for joy? Does our society’s constant drive for more information really make us less stressed? In considering the consumerist nature of our society, I think of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, a dystopian novel written in stark contrast to the brutal authoritarianism of the more famous 1984. In Huxley’s world, the main instrument of control is not inflicting pain, but the continuous availability of pleasure. Everyone’s desires are instantly gratified, and all struggle and pain are removed and replaced with a planned-out life of ease. The writer Neil Postman concisely describes the despairing conclusion that results from such a society: “Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism…[He] feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance…[He] feared that we would become a trivial culture.” All around us we see evidence that Huxley’s world is colliding with our world. We are surrounded by endless distractions and the call to embrace the newest trendy thing. Is this the kind of outlook that should be influencing our faith? Part of us may enjoy the rush of all the constant “newness”, but it may very well be trivial and overwhelming.

Rather, the unchanging and universal stories of the Bible present us with a way to separate our minds from the chaos of culture and ground ourselves in timeless wisdom and truth. Yes, the Bible was

addressed to an audience thousands of years ago, but how different are we from those shepherds and fishermen? We all have basic needs of hunger, thirst, shelter, and clothing—and we work to remedy those needs. We all live under the shadow of physical threats— war, oppression, disease, and natural disasters. And we face not just physical problems, but those of the mind as well.

Greed, anger, and lust afflict us still. We want feelings of love and comfort and strive to achieve them through building friendships and working towards success in life. Is the “twenty-first century problem” of an ECON 1110 prelim really a unique issue? Think of the questions involved: “Should I spend time overstressing on this or not?” “Why do I need to learn this?” or “How can I cope with this uncertainty about what is going to happen?” These are the very same questions that I am sure Noah felt

as he was given the task of building a massive ark without understanding its purpose.

Rather, the unchanging and universal stories of the Bible present us with a way to separate our minds from the chaos of culture and ground ourselves in timeless wisdom and truth.

Although the shape and form may differ, the problems and joys that we

the Bible, they were not super men of virtue. Moses murdered a man in cold blood. [3] David also committed murder, and followed it up by sleeping with his victim’s wife. [4] Jesus’ disciples ran away when he was arrested by the Romans. [5] These Biblical characters were not heroes, but mere humans. In the same way that a novel is attractive because of its relatable characters, the Bible is even more so. There are a host of characters that share our struggles.

And what makes Christianity so unique is that all these stories are anchored on one overarching narrative. There is purpose and continuity in everything in the Bible, and that continuity extends to us. Although new scripture is not being added to the Bible, Scripture has made it clear that the generations to come were to continue what was laid out in the Bible.

This story is centered on Jesus, God in the flesh, who came to Earth to experience core human struggles and overcome them. He felt pain, hunger, thirst, temptation, and ultimately one of the cruelest deaths imaginable, but through it all, lived a perfect life focused on ministering to those around him. Hebrews 2 says, “For because he himself has suffered when tempted, he is able to help those who are being tempted.” [6] We can look to the human characters in the Bible and feel their pain and learn from their wisdom, but we can also look to Jesus who felt our pain and temptations yet conquered them in a way that no one has done since.

enemies, and wars would break out. Then, the Israelites would cry out to God for help. God would then send a leader who would help them, and after defeating their oppressor, would try to set them on the right path with more laws. Although what happens next is obvious, to illustrate with the words of God himself, “[The Israelites] hear what you say, but they will not do it; for with lustful talk in their mouths they act; their heart is set on their gain.” [7] And then the cycle begins afresh.

I’m sure our professors can relate. In countless lectures, they tell us what we need to know for the exam. They give us homework so that we can practice our skills. They tell us to study consistently. And then when the test comes, people don’t do well. There’s something about us that makes us just not listen.

The Old Testament is full of these laws, with whole books like Leviticus being exhaustive lists that affect every aspect of life, including in-depth descriptions of how to perform sacrifices, what to eat, and specific colors and numbers of stones that have to adorn priestly garments. Even as a modern reader, my mind is overwhelmed by the vast number of laws. How much more overwhelmed would I be if I were to actually be governed by thousands of strict statues?

It’s not about the actions anymore, but the heart behind our actions that the Bible is concerned with.

face are not much different than what one might have faced 2000 years ago. Around 600 BC, the prophet Habukkuk lamented that “Destruction and violence are before me. Strife and contention arise…For the wicked surround the righteous; so justice goes forth perverted.” [2] Clearly, we have not really solved any core human issues in a definitive way, and the Bible is all about these core issues.

Although we revere the characters of

However, we shouldn’t be concerned with trying to see the Bible as a relevant, up-to-date, trendy guidebook/checklist to a “successful” life because that isn’t the point of the Bible. In fact, more than half of the Bible, the Old Testament, is a cycle devoted to showing that even God’s people couldn’t even resolve their own greed and affliction. The cycle begins with the Israelites, God’s people, falling into sin. They embrace corruption, mistreat the poor, and give into drunkenness. In the next part of the cycle, the Israelites would experience troubles as a result of their deeds. Their corruption would earn them many

That’s why the New Testament completes the Bible as an utterly revolutionary outlook on the obstacles we face. It is no longer how many laws we can correctly keep that matters, but how our heart is transformed. It’s not about the actions anymore, but the heart behind our actions that the Bible is concerned with. In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus gives a scathing rebuke to the Pharisees, the religious leaders of the day who were obsessed with the word of the Law, saying “Woe to you, teachers of the law and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You clean the outside of

the cup and dish, but inside they are full of greed and self-indulgence.” [8] At its core, the message of the Bible is quite clear. Go out into the world and make disciples, love God, and love your neighbors as ourselves. [9] A recent article in the Cornell Daily Sun talked about how the flood of social media distracts us from the beauty of the world around us. [10] Perhaps in the same way, we should not see the lack of new Scripture or direct words from God as a bad thing, but rather God’s way of telling us that all the beauty of His message is already before us.

I sometimes reflect on the fact that faith too can be treated as a commodity.

As I enter Temple of Zeus for my daily study sessions, I am always greeted by words from Cornell’s former president Hunter Rawlings: “Education is not a commodity but a genuine awakening of a human being.” As I walk past it, I sometimes reflect on the fact that faith too can be treated as a commodity. If

we view the Bible as just another set of guidelines or another self-help book out there, then what’s to stop it from being drowned in all the other commodities out there? Or maybe the Bible’s value as a commodity is really high, but not for its real worth in shaping you but rather for what it can get you in social circles.

Just like having the right internships and the right letter of recommendation to land us a new job, having read the right theological works and knowing just the right Christian answer to every question will make us feel valuable. But this is just more slavery to thoughts that we were supposed to be set free from.

Just as with education, we should seek inner awakening from God’s word, and it is that awakening that will equip us to live in the world around us.

Last fall, Claritas’ theme of the semester was “foundations,” and that is such a crucial pairing with this semester’s theme of “mystery.” In the area of mystery, Christians have to accept that life is chaotic and that there are many unanswered questions about the things past, the things present, and the things

to come. And that is where having a foundation in the unchanging Word of God comes in. Amidst all the change of the world, we should anchor ourselves to God’s word and not use it as a special manual to cure life’s problems, but as a way to cure our broken hearts so that we can better cope with life’s problems. Our struggles today are not trivial, but we should find consolation in the fact that they are all part of a larger story. A verse from the Jewish teacher Sirach sums up what our mindset should be: “Think about what is commanded you, for you do not need what the Lord keeps hidden.” [11]

Joaquin Rivera is a sophomore from Texas majoring in ILR and minoring in Classics. He likes to play piano, read random books he finds in the Cornell store, drink white chocolate steamers in Green Dragon, and tell everyone about Rome.

[1] Malachi, Malachi 1:1 (ESV), Onesimus, Philemon 1 (ESV), The Pharaoh, Exodus 1 (ESV)

[2] Habakkuk 1:3-4 (ESV)

[3] Exodus 2:12 (ESV)

[4] 2 Samuel 11 (ESV)

[5] Matthew 26:56 (ESV)

[6] Hebrews 2:18 (ESV)

[7] Ezekiel 3:31 (ESV)

[8] Matthew 23:25 (ESV)

[9] Matthew 28:19 (ESV), Matthew 22: 37-39 (ESV)

[10] Aaron Friedman, “Social Media: The Thief of Joy,” Cornell Daily Sun, October 6, 2022

[11] Sirach 3:22 (Eastern Orthodox Bible)

[12] Rood, Ogden Nicholas, “Modern chromatics: with applications to art and industry,” 1879. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[13] Bousch, Valentin, “Moses presenting the tablets of law,” 1532. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[14] “S. Maria in Trastevere, Ionic capital, volute, side elevation (recto) Unidentified, Ionic capital volute, construction diagram (verso)”, early to mid-16th century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[15] “Marble column from the Temple of Artemis at Sardis,” ca. 300 BCE. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[15] “Marble column from the Temple of Artemis at Sardis,” ca. 300 BCE. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[15] “Marble column from the Temple of Artemis at Sardis,” ca. 300 BCE. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The remains of my belov’d on my shoulder Light a feather, yet burdensome a boulder.

My child’s weightlessness makes this heart weary The viscous clothes on my back: bloody and teary.

Oh Lord my God, why have You forsaken me? Carnage and slaughter surge my world as the sea!

All my life, the earth never ceased to rumble I feel her delicate spine crack and crumble!

The Lord my rock, my redeemer? Love I can’t Taste or see, touch or perceive, but doubt I shan’t.

Oh Mija my daughter, tremble no longer Death defeated, Jesus prevails and conquers.

And with your mother please keep calm and just wait, Because to the heavens is my old soul’s fate.

Matt

El saco beis y tosco, encima del hombro rosa’o e hincha’o, esta cosa en el condenado saco... qué hermosa... Ahora, gris, verde, y frío la piel

Me duele el poco peso de mi ángel; mis pies rotos llevan a mi preciosa arriba; llora mi ropa viscosa de sudor y sangre en la tierra cruel

¡Dios! ¡La Cruz me ahoga y me baja! ¡Esta vida, Tus deseos me matan! ¡Siento su cuello se rompe y raja!

¡Mija! llenado de dolor, relaja ahora; y con tu mamá espera

and watching the Ravens dominate on Sundays.

Frank Fang

Frank Fang

After a long day of classes, I was sitting in Okenshields, scrolling through my Instagram feed instead of talking to any of the dozens of people around me because I really needed a “mental break.” I felt a deep and aching sense of existential dread as I noticed that I had lost 1 whole follower. Amidst my blinding fury, I downloaded the first Instagram unfollowers app I saw in the App Store. Without hesitation, I plugged in my dad’s credit card information to pay the $54.99 a year to see who unfollowed me. I would stop at nothing to uncover the identity of the insolent fool who decided that they didn’t need the false image of myself that I presented to the world in their life.

Why, O God, do you allow a good man to suffer?

I tapped on the unfollowers button and to my utter dismay, it was the girl that I followed after teaching her to use the ridiculously overcomplicated laundry machine in our dorm’s basement and never saw again. Why did she do that? I legitimately thought that the next time I saw her, I would ask her out to dinner at Morrison (maybe even sacrifice a guest swipe on her), go on a few dates, and then propose. We would live a beautiful, amazing life together with 2.1 kids and no drama at all just like God would want. Or something like that. Misery consumed me as my beautiful future disintegrated—reduced to ash and spite.

Why did God rip my future away from me?

I left Okenshields, my mind plagued by these questions. The colorful leaves were nothing but a blur in the tunnel vision of my confusion. I decided that

these questions and painful feelings were just too much to think about, so I figured now would be a great time to log onto Snapchat to take pictures of absolutely nothing and send them to the 78 people I hadn’t responded to yet. I angled my camera at Libe Slope and noticed how pretty the sunset was through my phone. My friends from back home would be so jealous to see the beautiful environment I’m in. I snapped a quick picture and buried my nose back in my phone because the OLED display on this little box had so much more vibrancy than the real-life beauty directly in front of me.

Why am I so attracted to mechanical light? Am I a man or a moth?

Consumed by betrayal, I felt compelled to tear my clothes, shave my head, and fall on my knees in the middle of the Arts Quad supplicating at the feet of Ezra Cornell.

As I mindlessly swiped, I noticed that it had been a few days since I had aimlessly tapped through the private story of this one guy that added me from a Cornell Class of 2026 GroupMe. On top of this, there was a timer next to our streak. Had I been removed from his private story? Why would he do this? I had a 97-day streak with him. I was three days away from reaching the 100-day milestone that defines true friendship and false friendship. Like a thief in the night, he had snatched away the hope of witnessing a 3-digit number next to the fire emoji. Why did God put it in his heart to destroy our friendship? Am I living out the story of Job on this forsaken day? Consumed by betrayal, I felt compelled to tear my clothes, shave my head, and fall

on my knees in the middle of the Arts Quad supplicating at the feet of Ezra Cornell. Unfortunately, I cared too much about what other people thought of me, and I would look weird. So, instead, with the fury of a thousand suns, I removed my betrayer from my private story too. I again questioned God’s fairness.

Why did God allow so much suffering in one day?

Sick and tired of these questions and this pain, it was time to hit Helen Newman. If I could just get absolutely shredded, maybe I could get back at the people who damaged me. I chugged some creatine and some pre-workout, put my AirPods in because silence is uncomfortable, and turned on some Olivia Rodrigo since her entire album about a singular break-up really spoke to me and my situation. [1] I figured this would be a great time to max out on the bench. With an absolutely primal grunt that surely had the other gym-goers quaking in their GymShark apparel, I hit a new max. While I dapped my spotter up and yelled profanities and finally realized the true meaning of my suffering. Suffering allows you to get absolutely yoked.

To cut me and everyone else in the world some slack, we are fighting against a team of people (possibly Cornell graduates) in Silicon Valley getting paid to keep our eyes on their app for as long as possible.

....

Even though the caricature in this story is ridiculous, as soon as your hands put down this journal, it will likely be replaced by the $1,000 piece of corporate tech that your parents probably bought you. When we are inundated with classwork, clubs, and other responsibilities, we end up relying on shallow narratives even when we aren’t consciously aware of them. We believe that social media can be a substitute for human

interaction, and we unfortunately turn to technology for validation and comfort. I absolutely used to obsessively check the Instagram unfollowers app (I promise I didn’t spend $55 on it, though). I am a frequent victim of the doom-scroll and notice hours of my time going by that could be spent doing literally anything else. My vernacular in speech and text has become reduced to the trending catchphrases that the Internet deems comical. Finally and worst of all, my phone distracts me during conversations with the people in front of me. The human brain is not made to multitask. I cannot give my full attention to someone standing in front of me while judging someone’s political views on Instagram. To cut me and everyone else in the world some slack, we are fighting against a team of people (possibly Cornell graduates) in Silicon Valley getting paid to keep our eyes on their app for as long as possible.

Being on our phones is the utter opposite of a mystery. Phones are programmed to give us all the answers. We have access to almost all the information mankind has ever developed due to our phones. We would like to present ourselves on social media in the same way. The few posts and stories that we share are meant to encapsulate all the information about ourselves that has ever existed. We lie to ourselves and the world.

We can better understand how technology negatively impacts our day-to-day lives and our relationship with God through the story of Christ’s Temptation by Satan during his 40 days of fasting in the desert. During those 40 days of fasting, Satan presented Jesus with three different tests: quell his hunger by turning stones into bread, prove that He is the Son of God by throwing himself off a cliff to be saved by angels, and easily become king of the world by just bowing down to the devil. The devil only offered shortcuts. Turning stones into bread would satiate Jesus’s physical needs, but it would shorten

Jesus’s sacred fast. Being saved by angels would prove to all that He is the son of God, but that would also leave the necessary sacrifice unfulfilled. Bowing to Satan would hand the world to Jesus on a silver platter, but being the king of this physical world is nothing compared to being the King of Heaven. [2]

Similarly, our phones offer us those exact same shortcuts to gratification. They tempt us to find entertainment through brain-numbing scrolling in moments of boredom or procrastination. They deceive us to think that accumulating followers can be a substitute for complex, timeconsuming, yet rewarding relationships with our peers. They lie to us by telling us that likes, comments, and shares can easily help you achieve a feeling of validation. However, none of this will ever lead to anything worthwhile.

Truly meaningful relationships are forged when we take time to sit down and spend quality time with someone (without the interference of phones).

Being patient is difficult at Cornell considering the scarcity of time. Fortunately, we are actually very blessed to have long walks in between our classes. Getting off your phone and taking your earbuds out while walking the one mile to your 10 AM every morning might lead to a welcome encounter and conversation with someone. If you are not lucky enough to bump into someone you know, walking in silence gives you the time and space to talk to God. Truly meaningful relationships are forged when we take time to sit down and spend quality time with someone (without the interference of phones.) True joy that transcends quick hits of entertainment and distraction comes from time spent with God. True validation and purpose come from the fact that we are so intimately known by God and have the honor to devote our lives in worship to Him. We need to skip shortcuts from our phones and delve into the mystery and wonder of God. If Jesus walked into Okenshields with his tunic-clad

disciples, would anyone be scrolling through Sidechat or would everyone be in awe of the beauty in front of them? It’s time for another mental break. I wonder what Pete Davidson is up to.

Frank Fang is a First-year Biological Engineering Major from Abilene, Texas, which is the home of the Abilene Christian University Wildcats (scratch ‘em!). Frank can commonly be found crying in a fetal position next to his cello in the practice rooms of Lincoln Hall. When he is not crying, Frank enjoys hiking, finding new artists to add to his “Powerful Women that I’m attracted to” playlist, and thinking about the concept of working out.

[1] Olivia Rodrigo, Sour, 2021.

[2] Bridgetown, “Part 5: The Father of Lies,” 2015.

Bridgetown Audio Podcast. Podcast, audio.

[3] Kim, Minjung, “Predestination,” paper collage, 2012, In Seed, John, “Minjung Kim: Predestination,” Huffington Post, 2012.

Should I have done more applications? This question lingered on my mind as I waited for a reply from the 1 (one!) business club I had applied for. I only realised the depths of my folly when I talked with friends who had applied for five, seven, or even ten clubs. Those who were lucky received interview offers from half of the clubs they applied for. Failing to get into even the first round of interviews gave me a spectator seat to a busy September weekend, watching freshmen in navy and grey suits fill their Saturdays with coffee chats and preparing for interviews in Crossings Cafe. As I listened to a friend fret over slide decks and behaviorals, I was struck by the tension and anxiety in so many of my peers. Just why were we doing these applications?

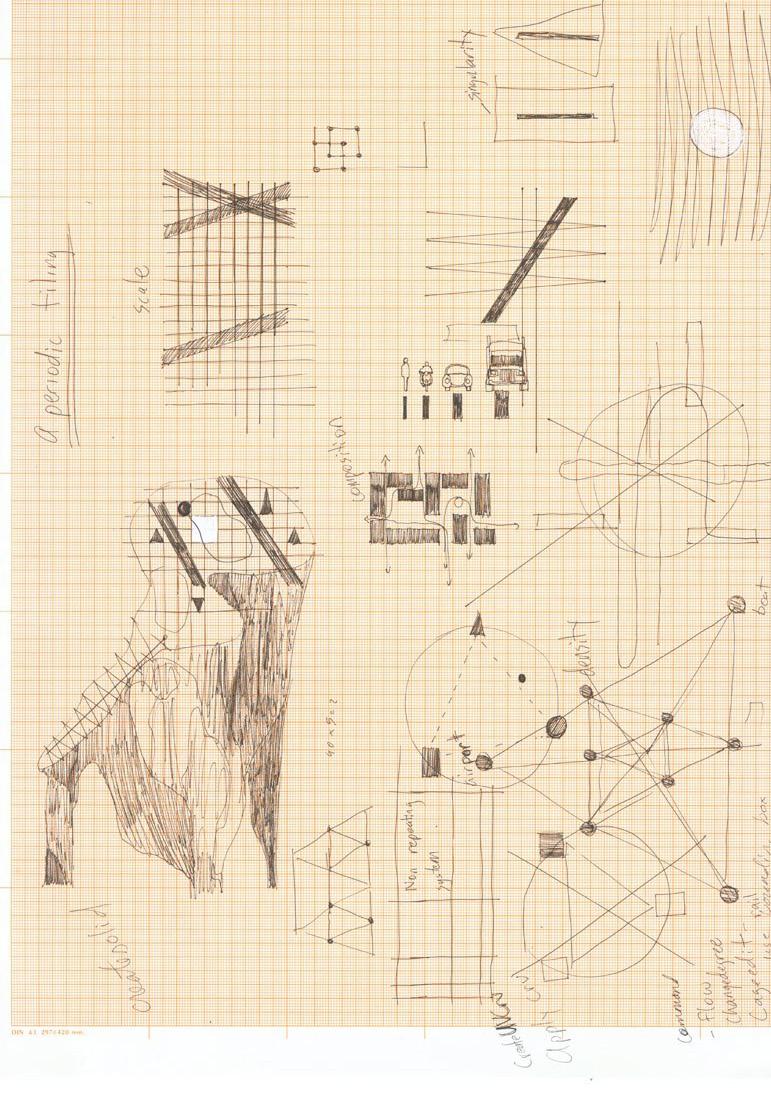

A recent article in the Cornell Daily Sun, “The Club-Catastrophe,” describes the fervour of club application season, the “cutthroat tension” to get into clubs that grant exclusive access to top firms. [1] Looking for security, certainty, and belonging, we throw ourselves into interviews and resumes, taking control of our own journey. I began to see how much of life I approached like this as the semester went on: problem sets, friendships, even what to have for lunch. In most situations, I overevaluated every angle to act accordingly to find the best solution. In class, we are encouraged to ask academic questions constantly and are equipped with the capacity to answer them. From the birth of stars to the biology of starfish, Cornell gives us scientific and logical tools to uncover new knowledge and eliminate doubt.

By contrast, we are less comfortable with the idea that there may be questions that are unsolved and unsolvable.

By contrast, we are less comfortable with the idea that there may be questions that are unsolved and unsolvable. Questions

about what lies ahead of us: What will my job be after I graduate? Who will be my next relationship? What is the purpose of my life?

I love reading because following the thread of a good story is often a welcome balm after searching for coherency and meaning in my own life. One of my favourite books is Mistborn by Brandon Sanderson, in which the author imagines a world shrouded in mist with magnetism magic and political intrigue. [2] I feel a yearning not only for a world so much more interesting than my own, but for the clear, almost simple challenges that each character faces. Even through every trial, I can see each character’s drive and purpose and how every event shapes their story, even if they do not know it yet. Because the ending is already written, I have a certainty that the author weaves each heartbreak and triumph into a satisfactory end.

Searching for the answers to big, lifealtering issues was part of what led me to Christianity and the way that it addressed problems without a clear answer. But even amidst the busyness of college life, in between CS problem sets and late-night parties, I’ve been surprised how many students ask the same questions and grow frustrated being unable to answer them. Talking late at night with a non-Christian friend, our conversation wound its way from French philosophers like Satre and Camus into discussions about morality and life. “What do you think happens when we die?” I asked. She shrugged her shoulders. “I don’t have a clue.”

To me, mystery—a lack of information that we cannot overcome, whose depths are uncertain and vague—is a part of our lives. Mystery is part of our experience of life. We do not often think about it, but our brains only hold a finite amount of knowledge. None of us really knows for sure what will happen tomorrow. Events come at us from unexpected angles; anything from the weather to a worldwide pandemic upends our plans. Even in the calmest of times, life can feel random and disconnected, just a meandering set of events.

The sense of the unknown is something of a looming spectre at Cornell, where our future horizons are blotted by mountains to climb. As students, we are starting to choose courses and careers, where we want to live, who we love, and what we believe. We cannot be sure that the choices we make about our future are good decisions, let alone the right ones. This uncertainty contributes to the anxiety and fear felt by Cornell students; Cornell’s 2020 mental health survey found that 75.5 percent of undergraduates were “moderately” or “very stressed” over concerns about the future. [3]

In the face of mystery, how do Cornell students respond? During my short time here, I would contend two behaviours by which students demonstrate our feelings about our unknown futures. The first is the academic pressure and constant busyness that Cornellians experience. Freshman orientation was my first exposure to this; new students pressed on the importance of “networking” with the clubs that would help you in which fields and how to best ace our interview processes.

Talking with upperclassmen confirmed that the obsessive preparation and stress-induced atmosphere persists beyond college. One junior related how when she got a job interview from Goldman Sachs, a friend remarked that people took weeks off school to prepare for interviews and would do anything for the chance to take a job there.

It’s not new that it is almost an expectation for Cornell students to drown themselves in work. Rather, I hope to highlight that why we work so relentlessly is partly to give us a sense of security and control. Studying can be pursued for its own pleasure, and I’m sure you, like me, know many friends who love what they do. On the other hand, how many more do we know that wring their hands over business fraternities and are elated over their summer internships? As more and more students turn to STEM fields over the humanities, college is a way for us to get a high-paying job and have at least some say in what our future life looks like. [4]

On the other hand, I imagine there are readers who would argue that the unknown future isn’t really a cause of concern for them or their friends. Who knows what’s going to happen anyway? Why waste breath on it? During my first time at a frat party early in the semester, I could see how appealing this approach was. With the strobe lighting, free-flowing drinks, and sweltering air pressing on my skin, the packed basement seemed like a tiny selfcontained world. All of the sensations made time seem to flow by—it was almost easy to ignore what was going

on outside or even what I had to do tomorrow.

I think most students at Cornell have had both these attitudes at one time or another. We want to plan out our future and be in control while sometimes

and His love for us. The most striking evidence of His sovereignty is how God the ruler came to earth, took the form of a Jewish carpenter, washed the feet of others and died a criminal’s death to redeem us from sin. 2 Timothy 1:9 says that God was the one “who saved

being able to ignore it entirely. Christians are in no way exempt from the same anxiety and fear as they face the future. In Ecclesiastes 3:21-22, the writer laments, “Who knows whether the spirit of man goes upward…Who can bring him to see what will be after him?” [5]

Yet there is a Christian response to uncertainty about the future that I think doesn’t put it all in our hands or lead us to ignore it entirely. When we consider a future outside our ability to understand it, our attitude can be grounded in a belief in a sovereign God. Christians believe not in a creator who made the universe and left it to run on its own, but in an actively intervening God. Rather than a watchmaker, He is like a father who gives life to a child and then raises him, or a caretaker who plants seeds in a garden and waters them to flourishing. God’s sovereignty encompasses His control over the future, His movement in our world

us and called us to a holy calling… which He gave us in Christ Jesus before the ages began.” [6] Even when many things about our future are unknown, we can know that God was planning our ultimate end from before the beginning of history.

It is His character as a God who is in control of all things that allows Christians to trust God over what happens in the future. But isn’t this faith in an unseen, seemingly silent God just another version of ignoring the future, throwing our hands up in the air and blindly trusting things will work out? Not at all! In his letter to the Romans, Paul, the primary author of the New Testament, argues “For in this

When we consider a future outside our ability to understand it, our attitude can begin grounded in a belief in a sovereign God.

hope we were saved. But hope that is seen is no hope at all. Who hopes for what they already have?” [7] Our faith is in an unseen person, but not in an unknown one.

The Bible is not just a theology or a history but an anthology of the many stories of God, working in the lives of ordinary people. One of my favorites is Naomi, a elderly woman who loses her husband and sons, without any hope of a family to carry on her legacy or to support her in her old age. She is left without a shred of security and is so moved that she asks to be renamed “Mara,” which is Hebrew for “bitter.” [8] Yet God is at work in her story, giving her a grandchild through her daughter-in-law, Ruth, and bringing a new family to her. All across the Bible, we see God active in the lives of His people, working for their good even when they cannot see it.

Even when it seems God fails, we can still be called to put our trust in Him. In Mistborn, the main character Vin talks with Sazed, a steward in charge of keeping her safe. As their plans seem to go awry, he counsels her with this: “Belief isn’t simply a thing for fair times and bright days...What is belief—what is faith—if you don’t continue in it after failure?”

We can draw on the consistency of God’s character, evidenced by what He has done in the past and knowing He will do the same in the future.

It is out of this place of security we can form an attitude that helps us deal with the vast mystery of what will happen to us. We can begin by fully accepting that we are limited, frail beings. For example, I love listening to rap music when I work out, but sometimes I think of the exquisite lies we tell ourselves to pump us up; we’re a god, we’re a beast, we’re invincible. I think about the line from Juice WRLD’s “Come and Go” where he says: “I try to be everything that I can / But sometimes I come out as bein’ nothin’ ”. [9] At the end of the day, we are unable to fully control our future but we can trust that there is someone who can. We don’t just have to

rely on our inner strength, but can fully lean on and trust God to know what job we will work on and who we will meet in the future.

We can also cast off our anxiety and recognise it for the unproductive and damaging emotion that it is. In Matthew 6, Jesus says,

“And which of you by being anxious can add a single hour to his span of life? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they neither toil nor spin, yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. But if God so clothes the grass of the field, which today is alive and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, will he not much more clothe you…?” [10]

Worrying and fretting does little to help us, only adds to our burden of stress, and can actively hamper our ability to plan for the future. We can rest easy that just as God beautifies birds and flowers, He infinitely more cares about our wellbeing and health. Our job is to reflect this love to those around us, leaving everything else in the hands of a loving God.