EDITED BY STEPHEN XU, MIRANDA WOMACK, EMMA YANG, MOKSH JAIN, VIHAAN HARI, AND TARUN SIVAKUMAR WITH PROFESSOR JEFFREY J. YOUNGER

DESIGNED BY JOCELYN CHEN AND SNEHA RAO

EDITED BY STEPHEN XU, MIRANDA WOMACK, EMMA YANG, MOKSH JAIN, VIHAAN HARI, AND TARUN SIVAKUMAR WITH PROFESSOR JEFFREY J. YOUNGER

DESIGNED BY JOCELYN CHEN AND SNEHA RAO

NYU STERN STUDENT VOICES

VOL. 12 / SPRING 2025

Front cover: The Woolworth Building is a 792' landmark skyscraper located at 233 Broadway in New York City, completed in 1913. Once the tallest building in the world, it is renowned for its neo-Gothic design, ornate detailing, and its status as one of the city’s most historic and beautiful structures.

Front and back cover taken by Alexander Thomas-Tikhonenko, a junior (Class of '26) majoring in Photography & Imaging at New York University's Tisch School of the Arts, with a minor in Business, Entertainment, Media, and Technology.

ROHIT DEO

Dean of the Undergraduate College

Distinguished Service Professor of Business and Professor of Statistics

New York University Stern School of Business

In an era defined by both unprecedented challenges and boundless possibilities, the pursuit of innovative solutions has never been more critical. The Call presents a compilation of student essays that address some of the most pressing issues of our time through a variety of lenses, including technology, sustainability, health, social equity and others.

To that end, I invite you to explore how cacao trees might help mitigate the ecological tolls caused by oil palm plantations, the availability of microfinance opportunities in Rajasthan, an analysis of geothermal power in Texas, and the ways in which AI is being used to reduce food waste, among others. Indeed, this collection truly represents the belief that “big problems require bold innovation,” which rings through from each page.

I hope these essays not only inform but inspire you to envision how we might create a better future together. I am incredibly proud to lead the NYU Stern Undergraduate College and to work with some of the finest business students on the planet who are already creating positive change for a better tomorrow.

Welcome to this journey of exploration and possibility.

In the spring of 2024, we focused on Amazon in the first unit of the course as an illustration of the complexity of the relationship between business and other societal institutions, considering its competitive market positioning, labor relations, and carbon footprint. Then, in the second unit, we explored a series of challenges and opportunities that face many businesses around the world, including the transition to a carbon-neutral economy, the creation of a socially just workplace, the engagement with political controversies, and the deployment of artificial intelligence. Finally, we worked in the third unit to develop business strategies that can create economic, social, and environmental value for stakeholders, including sustainability strategies, circular strategies, social entrepreneurial strategies, and strategies that connect individual agency with value for society.

The Business and Society course is the first course in the Social Impact Core Curriculum. No other undergraduate business program in the world gives students the occasion to think critically about these important issues in such depth and at such length. We have been undertaking these efforts for more than twenty years at NYU Stern because we believe that business leaders today and in the future need to be capable not only in the functional core disciplines of marketing, finance, accounting, management, and operations but beyond that, leaders need to understand the overall purpose of business in and for society and be able to engage in critical reflection and dialogue when stakeholders disagree about or call into question the value that business can and should create for society.

Clinical Professor of Business and Society Richman Family Director of Business Ethics and Social Impact Programming

All 650 first-year undergraduate students are thus well on their way, both in terms of their study of business and also in terms of their careers as business leaders capable of leadership in these uncertain and polarized times. They are encouraged to think critically, engage in critical dialogue with each other, and explore innovative possible solutions to the seemingly intractable, grand challenges facing our global society. They give me hope!

I want to thank the contributing authors and editors of this publication for their excellent work. I also want to thank Mara van Loggerenberg, the senior associate director of social impact programming, for her efforts in optimizing this course every year. Finally, I thank my faculty colleagues, whose intelligence and empathy in the classroom help support all of our students through the learning process.

Onward!

BY CORBIN CANAVARROS

The article highlights the significant employment challenges faced by individuals with disabilities, particularly those with paraplegia, who experience a much higher unemployment rate than non-disabled people. The author proposes that Neuralink’s braincomputer interface (BCI) technology, specifically through its PRIME study, could be expanded to include workforce training, enabling participants to improve their employment prospects by learning to operate digital tools essential for remote work.

With over 70 million adults in the U.S. reporting a physical disability, efforts to improve their livelihoods should be at the forefront of society’s mind.1

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the 2023 U.S. unemployment rate for people with disabilities was 7.2 percent – over twice the 3.5 percent unemployment rate for people without disabilities.2 Additionally, the BLS reported that only 22 percent of people with a disability were employed, compared to 66 percent for those without a disability.3

People living with disabilities are confronted with a harsh reality: finding employment is an unfair challenge. According to the CDC, high rates of unemployment among people with disabilities directly contribute to “adults with disabilities reporting experiencing frequent mental distress almost 5 times as often as adults without disabilities.”4

In addition to the challenges faced by disabled individuals, a cost estimate from IBISWorld Industry Reports suggests that unemployment amongst people with disabilities cost American taxpayers $109B in 2024 through welfare and other public support programs.5 The figure on p.08 shows the high cost alongside the economic productivity foregone due to this group not contributing to the economy and the personal toll paid by the 519,000 unemployed

working-age people with disabilities (Figure 1).

Governments and other humanitarian organizations have become aware of the significant damage that unemployment causes for people with paraplegia. As a result, several initiatives have been carried out to improve the issue. Unfortunately, multiple studies have proven these efforts ineffective.

For example, a random controlled trial of over 20,000 individuals with spinal cord injuries (SCI) found that ‘supported employment programs,’ which include employment training, facilitated favorable employment outcomes among subjects post-SCI. While such assistance would help readjustment in theory, the results were varied. The rate of returning to work post-SCI for the individuals surveyed was approximately 29 percent, indicating that supported training was ineffective in reaching employment for the majority.10 This study highlights that programs designed to improve employment outcomes for people with paraplegia do not necessarily achieve the desired employment outcomes.

A paper in the International Journal of Social Determinants of Health and Health Services also found that unemployment rates among people who experienced SCI remained relatively

similar between countries with stronger or weaker public support programs for these individuals. In fact, the study found that income levels before injuries were actually the strongest predictor of returning to employment post-SCI.11 This statistic may prove that public programs designed to improve employment outcomes for individuals with SCI are not impactful enough. Another effort to improve employment outcomes for people with disabilities is Google Glass. This innovation from Google offers a “wearable, voice-and motion-controlled Android device that…displays information directly in the user’s field of vision.”12 Initially advertised as an “Assistive Technology”13 device, the glasses held promising potential to enable people with disabilities to complete jobs their disabilities prevented them from doing. However, poor results led Google to stop production less than a year after starting.14

With the results of these two studies and the story of Google Glass in mind, it leads to the question of why those with paraplegia experience low rates of employment despite programs designed to assist them in finding employment. To answer this question, a study in the Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology focused on people with paraplegia. The study found that the most common reason for lack of employment was “the state of health and disability,” placing this

Figure 1: Bureau of Labor Statistics employment figures6

number at 64 percent. Nearly a fifth of the respondents reported: “workspace environments which were not barrierfree and therefore not accessible without great effort.”15 Given this study, one could argue that the challenges in completing work and physical transportation to a workplace are the most common reasons why people with paraplegia experience low rates of employment. Yet, despite these hurdles, a novel opportunity exists to address this issue.

While previous attempts to improve employment rates for individuals with paraplegia have led to minimal improvement in employment outcomes, brain-computer interfaces (BCI) show promise in enabling people with paraplegia to join the workforce. BCIs are “computer-based systems that acquire brain signals, analyze them, and translate them into commands, relayed to an output device to carry out a desired action.”16 Neuralink, a BCI company founded by Elon Musk, states, “We are currently focused on giving people with quadriplegia the ability to control their computers and mobile devices with their thoughts.”17 Neuralink has made significant steps toward accomplishing this goal through its Precise Robotically Implanted Brain-Computer Interface (PRIME) study, which aims “to enable people with quadriplegia to control external devices with their thoughts, thereby restoring digital autonomy.”18 After receiving FDA approval for in-human testing, Neuralink surgically implanted a fully developed BCI device in a human with quadriplegia, enabling them to control a computer with their eyes and play online chess against other humans.

The results of Neuralink’s PRIME study indicate significant promise in enabling people with paraplegia to

“Neuralink has made significant steps toward accomplishing this goal through its Precise Robotically Implanted BrainComputer Interface (PRIME) study, which aims ‘to enable people with quadriplegia to control external devices with their thoughts, thereby restoring digital autonomy.’ ”

gain employment by enabling them to operate computers seamlessly. In this light, Neuralink should expand the objectives of the PRIME study to include workforce training as a central component for all participants seeking employment. Implementing workforce training for participants of the PRIME study would place Neuralink in a position to reduce unemployment for people with paraplegia, all while benefiting relevant stakeholders. Specifically, adding this component to the study would put Neuralink in a position to benefit society by enabling participants of the PRIME study to enter the workforce at much higher rates.

For several reasons, Neuralink’s PRIME study is ideal for implementing workforce training to improve patient employment outcomes. First, PRIME’s focus on enabling individuals with paraplegia to operate computers with their eyes comes at a time when, according to a McKinsey report, workfrom-home and digital gig-economy trends indicate that opportunities to make a living while remote are at the highest level in history.20 By training PRIME participants on how to operate email, word processors, video-call platforms, and various other digital services, Neuralink can improve the patient’s workforce skillset and significantly ease employment challenges for people with paraplegia. In addition to the technical feasibility of this change, PRIME is also ideal for implementing workforce training due to its logistical structure. The first 18 months for participants of the PRIME study include weekly monitored in-person and remote training on using the BCI to operate

a computer, utilizing exercises of operating different websites.21 This format would enable Neuralink to iteratively adapt workforce training to the patients’ demonstrated abilities, simultaneously allowing the company to collect more data for the PRIME study.

While some may doubt the efficacy of workforce training, as suggested above, “62 percent of people with SCI who had gainful employment had participated in vocational re-integration measures, while only 38 percent of the unemployed group had taken advantage of such support measures.”22 While workforce training is not 100 percent effective in enabling people with paraplegia to join the workforce, it does provide significant benefits.

Another concern some may have surrounding the implementation of workforce training in Neuralink’s PRIME study is employment opportunities for low-skill or uneducated people. While it is true that work-from-home trends have favored educated professionals, there is evidence that even low-skill or loweducation workers can make a good living through work-from-home gigs.23 Thus, concerns that implementing workforce training into the PRIME study would only benefit skilled or educated workers are invalid.

Workforce training in the PRIME study also benefits Neuralink. The company’s increase in its ESG efforts will serve to improve its public image. Part of the company’s mission aims to “create a generalized brain

interface to restore autonomy to those with unmet medical needs today and unlock human potential tomorrow.”24 Implementing workforce training into the PRIME study aligns with this goal and qualifies as ESG action through positive social impact. In addition, this initiative has financial incentives. Professor Tensie Whelan, Director of NYU Stern’s Center for Sustainable Business, states that 58 percent of corporations that invested in ESG initiatives experience positive results.25 Having faced criticism for its tight control over results from the PRIME study,26 Neuralink is in a position where demonstrating a commitment to social good is critical. As such, Neuralink’s public figure founder and CEO, Elon Musk, should leverage his public platform to bring awareness to the company’s efforts in the paraplegic employment space.

On top of improving Neuralink’s public image through investment in ESG, implementing workforce training into its PRIME study would enable Neuralink to make a measurable contribution to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. A study in Nature found that “AI may act as an enabler on 134 targets across all SDGs, generally through a technological improvement, which may allow it to overcome certain present limitations.”27 With the capacity to leverage its artificial intelligence capabilities, Neuralink can specifically address the UN’s eighth and third SDGs, which focus on employment and generally improved well-being,28 all the while making progress toward improving the devastating reality of high unemployment for people with paraplegia.

Despite the promise of regaining many abilities lost through paralysis, including the ability to work, some patients and members of the public may assume this process would be expensive. However, due to Neuralink’s extensive venture capital backing and the nature of the PRIME study, all costs associated with participating in the PRIME study are covered by Neuralink. With that in mind, there is no reason to believe that implementing a workforce training component changes the structure of the study and causes participants to have to pay for the service.

Another concern surrounding implementing workforce training into the PRIME study is whether employers want to hire individuals with paraplegia, even if they can work on computers. While this is a valid concern since significant discrimination

exists towards individuals with disabilities, a rise in work-fromhome and emphasis on ESG amongst corporations mitigates this concern.

A study in the Journal of Personalized Medicine found that the most common barriers to employment for people with spinal cord injuries are “transportation issues, physical inaccessibility, lack of accommodations, and discrimination by employers.”29 Three out of four of these reasons would be directly mitigated by working from home, a practice which is growing in popularity.30 The fourth concern, discrimination by employers, is rapidly declining, demonstrated by the fact that a historically high 65 percent of Fortune 500 companies list hiring more individuals with disabilities as a component of their ESG goals.31 In addition to this evidence, it follows logically that if participants of Neuralink’s PRIME study can fully operate computers, companies experiencing labor shortages (75

percent of American companies)32 would want access to a larger pool of potential employees. The concern that employers would not want to hire individuals who have undergone the suggested training in Neuralinks PRIME study may be insignificant.

Integrating workforce training into Neuralink’s PRIME study offers transformational societal benefits. By enabling individuals with paraplegia to work, Neuralink will help alleviate substantial emotional and financial burdens from the families of people with paraplegia, enhancing both economic independence and family well-being. Increased participation in the study due to increased employment opportunities would provide richer data and accelerate advancements in brain-computer interface technologies, potentially bringing forward the timeline for broader neurological solutions.

Furthermore, incorporating individuals with paraplegia into the workforce fosters a more inclusive society. Their unique perspectives can drive innovation and increase economic output, enriching the workplace diversity crucial for problem-solving and creativity. Neuralink’s initiative could transform the lives of many, paving the way for a society where every individual’s potential is recognized and valued and technological advancement aligns with human aspirations for a more equitable world.

1. What ideas in this paper affected your thinking about disabled people and their employment?

2. What various societal changes have made this idea more feasible than in the past?

1 “CDC Data Shows over 70 Million U.S. Adults Reported Having a Disability.” CentersforDiseaseControlandPrevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/ s0716-Adult-disability.html.

2 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024, February 22). Persons with a disability: Labor force characteristics summary - 2023 A01 results. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/disabl.nr0. htm.

3 Persons with a disability: Labor Force Characteristics - 2023. (n.d.-a). https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/disabl.pdf.

4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, November 20). The Mental Health of people with disabilities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/ features/mental-health-for-all.html.

5 IBISWorld - industry market research, reports, and Statistics. IBISWorld Industry Reports. (n.d.). https://www.ibisworld.com/us/bed/federalexpenditure-on-disability-benefits/4867/.

6 Persons with a disability: Labor Force Characteristics - 2023. (n.d.-a). https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/disabl.pdf.

7 professional, C. C. medical. (n.d.-b). Quadriplegia (tetraplegia): Definition, causes & types. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/ symptoms/23974-quadriplegia-tetraplegia.

8 Budd, M. A., Gater, D. R., & Channell, I. (2022, July 20). Psychosocial consequences of Spinal Cord Injury: A narrative review. Journal of personalized medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC9320050/#B42-jpm-12-01178.

9 Ibid.

10 Nowrouzi-Kia, Behdin, et al. “Prevalence and Predictors of Return to Work Following a Spinal Cord Injury Using a Work Disability Prevention Approach: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Trauma, vol. 24, no. 1, 19 July 2021, doi:10.1177/14604086211033083. SAGE Journals, journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/14604086211033083.

11 Ona, Ana. “Disability, Unemployment, and Inequality: A Cross-Country Comparison of the Situation of Persons With Spinal Cord Injury.” International Journal of Social Determinants of Health and Health Services, doi:10.1177/27551938241235780. SAGE Journals, journals. sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/27551938241235780.

12 “Google Glass.” IoT Agenda, TechTarget, www.techtarget.com/iotagenda/ definition/Google-Glass#:~:text=Google%20Glass%20is%20a%20 wearable,inputs%20to%20provide%20relevant%20information.

13 “Google Glass Used as Assistive Technology: Its Utilization for Blind and Visually Impaired People.” ResearchGate, 2017, www.researchgate. net/publication/318733023_Google_Glass_Used_as_Assistive_ Technology_Its_Utilization_for_Blind_and_Visually_Impaired_ People#:~:text=In%20this%20point%20of%20view,Glass%20and%20 Cloud%20Platform%20functionality.

14 “Google Glass Used as Assistive Technology.”

15 Sturm, Christian. “Promoting Factors and Barriers to Participation in Working Life for People with Spinal Cord Injury.” Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/ articles/PMC7745479/.

16 “A Brain-Computer Interface (BCI).” PubMed Central (PMC), National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pmc/articles/PMC3497935/#:~:text=A%20brain%2Dcomputer%20 interface%20(BCI,carry%20out%20a%20desired%20action.

17 “Neuralink.” Neuralink, www.neuralink.com/.

18 “PRIME Study Progress Update.” Neuralink, Neuralink Corporation, www.neuralink.com/blog/prime-study-progress-update/.

19 “Neuralink.”

20 “What Is the Gig Economy?” McKinsey & Company, www.mckinsey. com/~/media/mckinsey/featured%20insights/mckinsey%20explainers/ what%20is%20the%20gig%20economy/what-is-the-gig-economy.pdf.

21 Prime-Study-Brochure.pdf. (n.d.-b). https://neuralink.com/pdfs/PRIMEStudy-Brochure.pdf.

22 Sturm, Christian.

23 “The Power of Gig: Shaping the Future of Work.” Awign Blogs, blogs. awign.com/the-power-of-gig-shaping-the-future-of-work/.

24 “Neuralink.”

25 Whelan, Tensie. Director, Center for Sustainable Business, NYU Stern. NYU Stern, 2021, mediasite.stern.nyu.edu/Mediasite/ Play/8ed20fa956524a6481b92d9c1aff7e881d.

26 Dellatto, Marisa. “Neuralink Monkey Deaths and Human Trials.” Vice, 21 Apr. 2023, www.vice.com/en/article/wxjp9q/neuralink-monkey-deathshuman-trials.

27 Vinuesa, Ricardo, et al. “The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.” Nature Communications, vol. 11, no. 233, 13 Jan. 2020, www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-14108-y.

28 Scott, Louise, and Alan McGill. “From Promise to Reality: Does Business Really Care about the SDGs?” PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2018, www. pwc.com/gx/en/sustainability/SDG/sdg-reporting-2018.pdf.

29 Budd, M. A., Gater, D. R., & Channell, I. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pmc/articles/PMC9320050/#B42-jpm-12-01178.

30 “Remote Work Statistics.” USA Today, www.usatoday.com/money/ blueprint/business/hr-payroll/remote-work-statistics/#:~:text=Just%20 over%20one%2Dthird%20of,remote%20on%20a%20hybrid%20 setup.&text=More%20than%20one%20in%20five%20Americans%20will%20work%20remotely%20by%202025.&text=According%20 to%20a%20survey%20we,least%20three%20days%20a%20week.

31 McGowan, Jon. “72% of European Companies Include Disability in Their ESG Sustainability Reports.” Forbes, 30 Apr. 2024, www.forbes. com/sites/jonmcgowan/2024/04/30/72-of-european-companies-includedisability-in-their-esg-sustainability-reports/?sh=4fe2a89367ef.

32 “Labor Shortage Stats.” Exploding Topics, www.explodingtopics.com/ blog/labor-shortage-stats.

Photo Credits:

• Jordan Nicholson/Disability:IN–Page 09

“I had been interested in brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and wanted to learn more about how they could be used to benefit society. I felt the nature of the rapidly developing BCI industry provided a robust platform for an examination of the intersection of science, business, government, and society.”

by Talia Lerner

ThisarticlediscussestheinaccessibilityofhealthyfoodintheBronx.Theauthor,TaliaLerner, proposesapartnershipbetweenBronxWorksandlocalbodegastoimproveaccesstonutritiousfood andincreaseconsumerawarenessthrougheducationalinitiativesandmarketingstrategies.

Out of all five boroughs in New York City, The Bronx ranks concerningly high in obesity, poverty, and low educational attainment, according to the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.1 Poverty and low education rates lead to unhealthy food choices and, ultimately, obesity.2,3 Conversely, affordable products and awareness of nutritional value can elicit healthier food choices.4,5

Since the early 2000s, schools, government entities, and community nonprofits have introduced countless strategies to improve health outcomes in this area, but to little avail. Living healthily in The Bronx is difficult because corner stores, known as bodegas, are the most convenient one-stop shop for Bronxites, but they stock a myriad of primarily unhealthy food.6 While non-profit organizations like BronxWorks work with bodegas to transform their product selections, these small businesses lack the financial incentives to provide healthy consumer

initiatives. Without consumer demand, a switch to healthier food risks lower profit margins, posing a difficult choice for bodega owners.7

To combat obesity in the Bronx, a synergistic partnership between BronxWorks and bodegas can popularize healthy foods while boosting interactive non-profit outreach to educate consumers on the importance of healthy lifestyle changes. This initiative elicits a positive feedback loop, generating profits for bodegas and creating meaningful, sustainable change.

Current measures to enhance the nutritional value of bodega offerings already exist under government initiatives, but problems mitigate their effectiveness. The rules primarily target bodegas that already have refrigeration and other equipment needed to carry perishable goods, ignoring bodegas that lack such infrastructure.8 Additionally, many government policies operate

off the idea that the Bronx is a food desert–it’s not.9 However, according to the National Library of Medicine, it is a food swamp with more access to nutritionally void foods than nutritious foods.10 Bodegas in the Bronx outnumber supermarkets by approximately a 35-1 ratio, and most residents rely primarily on bodegas for their food needs.11,12

BronxWorks and other nonprofits operate alongside government initiatives to promote a healthy Bronx community. Following a lifestyle-based strategy, they lead cooking classes, operate a community kitchen, run farmers’ markets, and hold educational events to encourage sustainable lifestyles in the borough. BronxWorks sometimes reaches out to in-need bodegas to help them transform their product selection. In the past, they’ve helped one store acquire a cooler and aided them in advertising their healthier products, albeit on a small scale.13

Despite initiatives to improve bodega product selections, these

convenience stores still remain notoriously unhealthy. Experts from New York University and the non-profit Bronx REACH found that “the density of corner stores is associated with an increased likelihood of consuming high-energy foods…and an increased risk of obesity among children and adults.”14 This finding dates to 2016, an entire decade after the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene launched its “Healthy Bodegas Initiative.”15

Currently, the interests of BronxWorks directly oppose corner stores; the non-profits seek better health for the community, while bodegas resist change in their interests of keeping revenue flowing. Most corner store owners reference low demand and a lack of refrigeration as two barriers to entry into the healthy food market.16

As a non-profit organization genuinely interested in making a

positive impact on the community, BronxWorks could expand its operations with bodegas to set them up for success through equipment acquisition and produce sourcing. Firstly, they will supply bodegas with the necessary equipment and shelving. Helping bodegas acquire fridges and other storage needs alleviates the fixed-cost burden that otherwise makes bodegas reluctant to switch their stock selection.17

They could also help connect corner stores to affordable produce, focusing on stocking seasonal produce alongside other sourcing to meet related needs. Seasonal produce is cheaper than non-seasonal fruits and veggies and is more likely to come from local farms.18 Besides the economic allure of stores buying local seasonal products for retail, these practices stimulate the local economy and promote sustainable practices.

However, at such a large scale, BronxWorks and bodegas can’t rely solely on local sources. To optimize the

quantity and price of orders, they could use what researcher Sara John calls a dynamic sourcing model in the public health whitepaper, “Balancing Mission and Margins: What Makes Healthy Community Food Stores Successful.”19

Labeled as an identifier of successful healthy stores, this model encourages diverse sourcing to minimize inventory costs or shopping different vendors seeking the best prices on goods to enable competitive pricing.20 Diverse sourcing could include alternative options like gleaned produce – leftover produce that isn’t economically viable for farmers to harvest – and opportunity buys – sales of products at highly reduced rates. In this example, bodegas can source food from local farms, national vendors, gleaned produce, and occasional opportunity buys.

Acquiring equipment for bodega use and helping them source products allows bodegas to possess higherquality stock. On average, these community stores carry lower-quality fruits and vegetables than their

supermarket counterparts.21 Consumers would feel more inclined to purchase corner store produce if it looked appealing at the very least. Bolstering quality will prompt customer satisfaction, which will increase the probability of repeat purchases and benefit the store.

In return for assistance from BronxWorks, bodegas will transform into the exclusive hub for nonprofit resources and serve as mini venues for community events and cooking demonstrations. BronxWorks currently uses non-food-related businesses (e.g., nail salons, laundromats, etc.) as an outlet for pamphlet distributions of the health/wellness resources they offer. Resources include assistance for eligible residents filing for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits (SNAP). Offering such posted useful information exclusively to bodegas will retain convenience for consumers and grant more community power to bodegas. People who don’t usually visit bodegas will need to visit them to access this information, thus increasing the store’s foot traffic. At the same time, people who already frequent bodegas will notice these enticing resources and have a greater chance of interacting with the organization.

Bodegas would also provide a

venue for cooking demonstrations and educational events that BronxWorks already holds. Most of BronxWorks’ cooking demonstrations and samplings occur at farmer’s markets and independently hosted events. I suggest they move the bulk of these interactive demonstrations into bodega spaces. They can also hold these events in front of the bodega storefront, weather permitting.

Such demonstrations will teach people how to cook with in-season produce that they may otherwise feel unfamiliar with, de-mystifying unapproachable or hard-tocook vegetables. Situating these demonstrations in or around the bodega storefronts, which carry the included ingredients, will help promote purchasing.

Cooking demonstrations and samples of healthy recipes can effectively encourage people to buy these corner store products. Consumers need to experience first-hand how delicious healthy dishes can taste. A marketing strategy at its core, cooking demonstrations represent an impactful nutritional intervention.

Studies prove that spreading nutritional information alone isn’t enough to enact change.22 Instead, combining informative interventions with modeling and encouragement of “positive ‘to-do’ behaviors”23 has the potential to create successful

change in fruit and vegetable intake. Another study from the Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior demonstrates the favorable effects of cooking demonstrations on dietary intake, nutritional education, and health outcomes. In agreement with this proposal, these researchers emphasize the need for community leaders to more astutely address economic barriers (like the price of food) to ensure effective results.24

Furthermore, bodegas should reincorporate past small-scale successful advertising strategies to market its stock effectively. A “Don’t Stress, Eat Fresh” marketing campaign from 2018 to 2019, led by Bronx Bodega Partners Workgroup, launched various advertisements in and around bodegas to encourage healthy eating.25 MESH Design and Development, the chosen design firm, created the joint marketing campaign with input from community voices. They created ads on public fixtures, buses, and geofencing around stores. Metrics gathered from the geofencing revealed an above-average level of interaction with the locationbased digital advertisements.

The participating bodegas also saw increased sales from the “Don’t Stress, Eat Fresh” project. Los Hermanos Bodega experienced a 50 percent increase in purchases after shifting to produce alongside this marketing campaign.26 Other government initiatives reported increased sales by participating bodegas.27 Advertised products led to an increase in purchases and profits compared to non-advertised products.28 This proves that bodegas can collect profits from healthy food – a crucial point for the initiative’s success. Bodega owners will only undergo inventory makeovers if they can see additional profit or, at the very least, avoid losses.29

This innovative, bodega-benefiting campaign occurred on a small scale; 53 bodegas participated in in-store advertisements. Approximately 15 of these 53 participated in the geofencing initiative. Expanding this virtual advertising strategy to include more

stores in the future may produce similar levels of engagement and encourage dietary improvements.

As part of the initiative, bodegas might also slowly increase the prices of select unhealthy foods to force buyers away from health-harming products. As bodegas shift to varied product selections, they might also incrementally increase prices for unhealthy products and place nearperfect substitutes beside them; for example, they might place grilled chicken breast meat near deli chicken meat and sweet fruit varieties like mangoes or bananas next to sugar-laden fruit products. Customers, noticing these price changes alongside marketed healthier alternatives, will be further incentivized to choose the latter.

Within this narrative lies a major benefit for sustainable bodegas: they can capture a growing market share of

On a side note, bodega owners also make up a part of the community. Unlike big corporations and food chains, they’re small business owners living in the Bronx. Therefore, they possess an innate “need and desire for a store to increase healthy food access.”31 While their businesses hinge on profits, the desires of small businesses overlap with community well-being– they just need to realize the possibility of achieving both profits and food access.

When working with bodegas of the Bronx, BronxWorks needs to keep a few things in mind. Corner stores make up a key stakeholder in the borough, integral to the community’s collective identity and culture. Clear and continuous recognition of the

consumers on the importance of healthy eating to drive them to purchase fresh foods. Bodegas know that if they stock fresher food, they must have appropriate consumer demand. BronxWorks knows that if they elicit these changes in bodegas, they must work harder to educate consumers to avoid bodega disenfranchisement -something they’re already interested in and actively embarking on. By doing these two things together, both sides achieve happiness and attain a clear incentive to do their part in this cooperative mission.

Another point to consider for BronxWorks outreach relates to the cultural authenticity of bodegas. Established by the Hispanic community, bodegas represent so much more than a corner store; they symbolize diversity, unity, and belonging. BronxWorks mustn’t

“...PARTNERSHIP

health-minded consumers. One bodega that expanded its selection to fresh salads in 2018 calls growing consumer demand the catalyst for this new offering.30 Other stores that introduced nutritious food alongside marketing support saw increased sales from the stakeholder value created. Healthy food and profits are not mutually exclusive.

Should the government continue nutritional literacy programs alongside the interactive model offered by BronxWorks, people will feel increasingly drawn to healthy products. Plus, the dangers of diseases related to obesity already circulate through school health classes, nonprofit mission statements, and widely-read NYC government statistics. It is the age of public health awareness, and bodegas must respond to this collective community stakeholder sentiment.

“unbreakable bond” bodegas have with the community must occur to effectively value their existence and work with them, not against them.32 When nonprofits try to scale, their “branches” should “grow down and out” to foster a foundation for subsequent outward scaling.33 If BronxWorks tries to scale its bodega initiatives without establishing personal connections with bodega owners, it will fail to grow outwards. Regular meetings with bodega owners and listening to their unique values and interests will make corner stores feel supported, not attacked.

By establishing a deeper relationship with bodegas, BronxWorks can reach a common ground with them and find a confluence of interests. In this scenario of synergistic interests, BronxWorks and bodegas can unite by educating

alienate certain demographics by removing access to culturally significant products deemed “unhealthy.” Instead, they should make sure cooking demonstrations shine a light on beloved cultural dishes in the community. At the same time, they can suggest how to prepare them in healthier ways for disease prevention.

To include other stakeholders in the discussion, BronxWorks should encourage a variety of cultural groups to volunteer to keep content geared towards the diverse borough. A variety of faith and ethnic-based collectives in the Bronx have interests in improving health.34 In line with this big idea of connecting with outreach targets, regular community meetings with different cultural community leaders (supplementary to the aforementioned bodega-owner meetings) ensure all

stakeholders feel heard and appreciated. Other stakeholders include healthcare facilities and schools. Both of these entities support healthy eating initiatives. Hospitals provide obesity treatment programs and healthy lifestyle training, including NYC Health + Hospitals’ bariatric services and Lifestyle Medicine Programs. Schools make efforts to provide healthier lunches and teach nutritional education. Efforts to combat obesity through this proposal may alleviate some financial and social burdens these entities currently face in combating the epidemic.

Similar to many sustainability

ventures, this initiative includes startup costs for store equipment, new food sourcing, and marketing efforts. Government grants and investors can help provide a main source of funding for these expenses. Additionally, BronxWorks must expand its volunteer force and staff to meet the demands of such growing outreach. If bodegas seek gleaned produce and opportunity buys, additional trained employees will need to work on scouting deals from local and national vendors. Bodega owners might also acquire sourcing and procurement training from BronxWorks experts and conduct these steps themselves.

Because of the nature of the issue, results from this initiative will take many years to show. Statistics

1. How might government support this initiative?

2. What are the challenges to this initiative?

regarding obesity itself cannot improve overnight; permanent weight loss is a long lifestyle process, and establishing healthy habits doesn’t happen overnight. It may take generations to break the current obesity trend because of its deep connection to systemic socioeconomic disparities.

Nevertheless, we can track changes by carefully evaluating buying habits, consumer purchasing power, and revenues. Are people buying more produce, whole grains, and legumes? Do they have more choices when considering their budget constraints? Are bodega revenues increasing or decreasing, and can this change be attributed to nutritious food purchases?

In conclusion, this proposal creates a deeper relationship between bodegas and BronxWorks through synergistic activities. BronxWorks will take measures to help bodegas introduce healthy products and promote on-site interactive marketing. Bodegas will advertise BronxWorks resources, increasing store foot traffic and outreach for the non-profit. These efforts will effectively change the buying habits of corner-store-reliant consumers, promoting good health and obesity mitigation over time. In such a scenario, calls to action for sustainability converge with the bodega’s interest in business prosperity.

3. In addition to gleaned produce and opportunity buys, what other approaches may reduce costs for bodegas?

1 Naidoo M, Traore K, Culp G, King L, Lopez C, Hinterland K, Gould LH, Gwynn RC. “CommunityHealthProfiles2018MapAtlas;TheNew YorkCityDepartmentofHealthandMentalHygiene,” 2018.

2 Millar, Helen. “What to Know About Obesity and Poverty.” Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, 25 Apr. 2023, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/obesity-andpoverty#:~:text=What%20to%20know%20about%20obesity%20 and%20poverty&text=Research%20suggests%20poverty%20has%20 links,time%20to%20engage%20in%20exercise.

/ TALIA LERNER

3 Sart, Gamze, et al. “Impact of Educational Attainment and Economic Globalization on Obesity in Adult Females and Males: Empirical Evidence from BRICS Economies.” Frontiers, Frontiers, 30 Jan. 2023, www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/ fpubh.2023.1102359/full.

4 Kern, David M, et al. “Neighborhood Prices of Healthier and Unhealthier Foods and Associations with Diet Quality: Evidence from the MultiEthnic Study of Atherosclerosis.” International journal of environmental research and public health vol. 14,11 1394. 16 Nov. 2017, doi:10.3390/

ijerph14111394.

5 Mackenbach, Joreintje Dingena. “Healthy Eating: A Matter of Prioritisation by Households or Policymakers?: Public Health Nutrition.” Cambridge Core, Cambridge University Press, 26 Feb. 2021, www.cambridge.org/ core/journals/public-health-nutrition/article/healthy-eating-a-matter-ofprioritisation-by-households-or-policymakers/6D5AEC30531ABE0C70 C8810883397E30.

6 Kiszko, Kamila, et al. “Corner Store Purchases in a Low-Income Urban Community in NYC.” Journal of Community Health vol. 40,6 (2015): 1084-90. doi:10.1007/s10900-015-0033-1.

7 Dannefer, Rachel, et al. “Healthy bodegas: increasing and promoting healthy foods at corner stores in New York City.” American Journal of Public Health vol. 102,10 (2012): e27-31. doi:10.2105/ AJPH.2011.300615

8 NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. “CEO Internal Program Review Report” for the Healthy Bodega Initiative.” DOHMH, 2008. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/opportunity/pdf/BH_PRR.pdf.

9 Elbel, Brian, et al. “Assessment of a Government-Subsidized Supermarket in a High-Need Area on Household Food Availability and Children’s Dietary Intakes.” Public Health Nutrition 18.15 (2015): 2881–2890. Web.

10 Cookesey-Stowers et al. “Food Swamps Predict Obesity Rates Better Than Food Deserts in the United States.” National Library of Medicine, November 2017. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/14/11/1366.

11 Rozner, Lisa. “‘Food Deserts’ Remain Big Problem in More than 2 Dozen New York City Neighborhoods.” CBS News, CBS Interactive, 13 June 2022, www.cbsnews.com/newyork/news/food-insecurity-remains-bigproblem-in-more-than-2-dozen-neighborhoods-in-new-york-city/.

12 Mackenbach.

13 “As Part of an Effort to Combat Obesity and Diabetes in Low-Income Communities, City Harvest and Bronxworks Help a Local Bodega Purchase a Cooler.” BronxWorks, 12 May 2021, bronxworks. org/2019/04/30/as-part-of-an-effort-to-combat-obesity-and-diabetesin-low-income-comunities-city-harvest-and-bronxworks-help-a-localbodega-purchase-a-cooler/.

14 Kiszko.

15 NewYorkCityHealthyBodegasInitiative, www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/ downloads/pdf/cdp/healthy-bodegas-rpt2010.pdf. Accessed 7 Dec. 2024.

16 Kiszko.

17 Ibid.

18 “What Produce Is in Season during the Winter Months?” OSF HealthCare, 26 Oct. 2022, www.osfhealthcare.org/blog/produce-in-season-duringthe-winter/.

19 John, Sara, et al. “Balancing Mission and Margins: What Makes Healthy Community Food Stores Successful.” International journal of environmental research and public health vol. 19,14 8470. 11 July. 2022, doi:10.3390/ijerph19148470.

20 Ibid.

21 “Online Food Shopping Exploded during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Can It Catch on with Bodegas?” NYU Steinhardt, Center of Health

and Rehabilitation Research, 8 Jan. 2024, www.nyu.edu/about/newspublications/news/2024/january/online-food-shopping-exploded-duringthe-covid-19-pandemic--can-.html.

22 Pem, Dhandevi, and Rajesh Jeewon. “Fruit and Vegetable Intake: Benefits and Progress of Nutrition Education Interventions - Narrative Review Article.” Iranian Journal of Public Health vol. 44,10 (2015): 1309-21.

23 Ibid.

24 Apatu, Emma, et al. “Cooking Classes: Are They Effective Nutrition Interventions in Low-Income Settings?” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, Elsevier, 1 July 2016, www.jneb.org/article/S14994046(16)30139-7/fulltext.

25 Jay, Mikey. “Bronx Bodega Partners Workgroup Don’t Stress, Eat Fresh Marketing Campaign.” Institute, NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 31 May 2019, institute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/ BBWDontStressEatFreshCampaign1-pagerBxDelegationApril2019.pdf.

26 Moura, Paula. “Ad Campaign Helps Bodegas Promote Healthy Food.” Mott Haven Herald, Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism, 12 Mar. 2018, motthavenherald.com/2018/02/25/ad-campaign-helpsbodegas-promote-healthy-food/.

27 Kiszko, Kamila et al.

28 Mikołajczak-Degrauwe, Kalina, and Malaika Brengman. “The influence of advertising on compulsive buying - The role of persuasion knowledge.” Journal of behavioral addictions vol. 3,1 (2014): 65-73. doi:10.1556/JBA.2.2013.018.

29 Healthy Bodegas (HB) A Program of the New York City Department of Health & Mental Hygiene (DOHMH): CEO Internal Program Review Summary, New York City Department of Health & Mental Hygiene, 23 Feb. 2010.

30 Pem, Dhandevi, and Rajesh Jeewon.

31 “What Produce Is in Season during the Winter Months?” OSF HealthCare, 26 Oct. 2022, www.osfhealthcare.org/blog/produce-in-season-duringthe-winter/.

32 “Bodegas in New York City: A Rich Tapestry of History and Culture.” NYC Moments, 23 Jan. 2024, nycmoments.nyc/nyc-culture/bodegasnew-york-city-rich-history-culture/#:~:text=Bodegas%20in%20 NYC%20Culture,beside%20Eastern%20European%20canned%20 goods.

33 Nardini, G., Bublitz, M. G., Butler, C., Croom-Raley, S., Edson Escalas, J., Hansen, J., & Peracchio, L. A. (2022). Scaling Social Impact: Marketing to Grow Nonprofit Solutions. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 41(3), 254-276. https://doi.org/10.1177/07439156221087997.

34 “Faith-Based Outreach Initiative.” The Institute for Family Health, Bronx REACH, institute.org/bronx-health-reach/our-work/faith-basedoutreach-initiative/. Accessed 4 May 2024.

Photo Credits:

• Wikiwiki718/Wikimedia Commons–Page 12

• Jeff/AdobeStock–Page 14

• Silvio Pacifico/Bronx Times–Page 16, 18

“When looking over the 17 SDGs, I was inspired and intrigued by “good health and well-being.” As someone committed to letting passion fuel all my academic endeavors, I geared my project towards this SDG to captivate my business interests and interest in physical wellness. Dietary issues in the Bronx require a multi-disciplinary solution, transcending just food or economic policy.”

By Jeffrey Gao

AuthorJeffreyGAo’spAperexplores A sustAinAble ApproAchtopAlmoilproduction. heproposes intercroppinGoilpAlmswithcAcAotrees,whichcAnreduceenvironmentAl dAmAGe,suchAsdeforestAtion AndbiodiversitylosswhileofferinGeconomicbenefits.

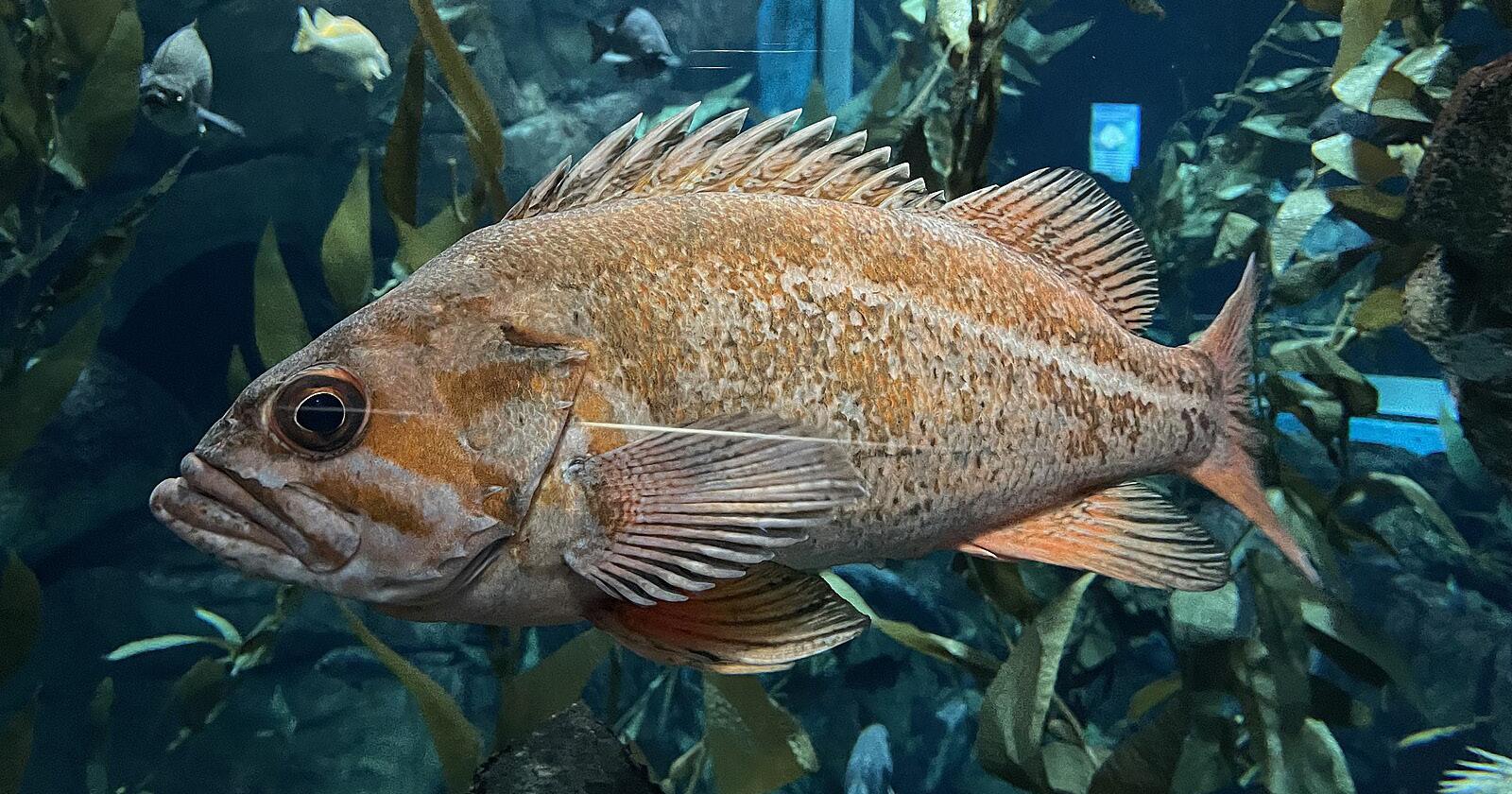

Palm oil seeps into our everyday lives, from things like chocolate and shampoo to others such as lipstick and biofuel. Today, it is the most popular vegetable oil in the world, found in over 50 percent of supermarket packaged products.1 Unfortunately, because oil palms grow in tropical climates, farmers often destroy tropical forests to clear land for oil palm plantations. Consequently, the expansion of these plantations has become the largest driver of deforestation in Indonesia–the world’s premier palm oil producer–accelerating climate change and threatening endangered species.2 Korindo, a Korean-Indonesian conglomerate that operates eight plantations, is a major contributor to this issue.3 In 2018, Greenpeace accused the company of clearing 11,120 hectares (approximately 43 square miles) of forests across five plantations.4 The worst occurred at PT Papua Agro Lestari (PAL), Korindo’s plantation in Indonesia’s Boven Diogel Regency, where the company destroyed 5,190 hectares of forests, an area the size of Manhattan.5 Palm oil producers like Korindo face few incentives to slow their expansion because they do not bear the full costs of deforestation. Meanwhile, existing solutions, such as certification programs, struggle

to balance the interests of palm oil producers, environmental activists, and other stakeholders.

To prevent further deforestation in PT PAL, Korindo can intercrop oil palms with cacao trees, boosting the company’s overall yield without expanding its land use. By growing both crops on the same land, Korindo also creates a more biodiverse ecosystem that is better at sequestering carbon, reducing the externalized impacts of palm oil production. With the recent surge in cocoa prices, this strategy is sustainable but has become economically viable as well, opening a new opportunity for Korindo to alleviate the environmental impacts of palm oil production.

The expansion of oil palm plantations releases significant greenhouse gas emissions, accelerating climate change. Many forests cleared by Korindo lie on carbonrich peatlands, which release vast amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere when drained. From 2013 to 2015, the increase in land used for palm oil production contributed 1.4 percent of global CO2 emissions, releasing an average of 500 million tons of CO2 emissions per year.6 The resulting climate change disproportionately impacts Indonesia, with the World Bank estimating that rising sea levels will submerge 95 percent of Jakarta’s coastal areas by 2050.7 Yet, neither palm oil producers nor consumers face the costs of frequent natural disasters and rising sea levels. Instead, the Indonesian government and its people bear these costs.

Beyond CO2 emissions, palm oil deforestation also severely impacts biodiversity, threatening at least 193 species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.8 Orangutans are one of the most affected, as lowland forests, their primary habitat, are ideal locations for oil palm plantations due to their flat topography and fertile soils.9 After decades of palm oil deforestation, Indonesia’s Sumatran Orangutan is now a critically endangered species,

numbering fewer than 15,000.10

Beyond environmental consequences, this loss of biodiversity harms Indonesia’s ecotourism industry, which represents 35 percent of the country’s tourism sector.11 A decline in tourism, which accounts for nearly 5 percent of Indonesia’s GDP, would hinder the country’s economic development and increase rural unemployment.12

Nevertheless, palm oil producers continue to build new plantations in lowland forests as they reap the economic benefits of the land without incurring environmental and social costs. This dynamic enables them to sell palm oil at reduced prices, further driving demand for their unsustainable production practices.

Existing solutions, such as the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil’s (RSPO) certification program, struggle to balance the diverse interests of the stakeholders involved. However, producers argue that the cost of obtaining the certification outweighs any benefits gained from a higherpriced “certified designation.”13

Economist Yu Leng Khor estimates that the price premium for certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) is only between $2.50 and $3.50 per tonne, negligible compared to palm oil’s current price of $863 per tonne.14 As such, only 20 percent of global palm oil production is certified, and Korindo has yet to become an RSPO member.15 Palm oil producers lack the economic incentives to seek RSPO Certification, limiting the program’s efficacy.

This low adoption rate places the RSPO in a dilemma between lowering or raising its certification standards. On one hand, environmental groups such as Greenpeace criticize the RSPO for allowing producers to signal sustainability without meaningfully changing their practices; over half of the palm oil producers accused of deforestation are members of the RSPO.16 On the other hand, enforcing strict standards to satisfy environmental groups could further drive palm oil producers away from becoming RSPOcertified, particularly smallholders who

“lack both the information and the degree of organization that certification demands.”17 Their small scale means that certification costs would consume between 5 and 14 percent of their revenue.18 If the RSPO agrees to environmental groups’ demands, it risks barring smallholders from certification, further hindering the program’s adoption.

Although the RSPO Certification attempts to mitigate the industry’s externalized costs through sustainability standards, it fails to alter the misaligned incentive structure that drives continued deforestation. Smallholders lack the resources to obtain certification, and larger companies like Korindo have few financial reasons to pursue it. To address this shortcoming, intercropping oil palms with cacao trees presents an environmentally and economically effective solution.

Environmentally, Korindo can implement this strategy to utilize its existing land in PT PAL more efficiently. Both oil palms and cacao trees thrive in similar climates: high temperatures, humidity, and rainfall, as found in PT PAL.19 The two crops do not compete for the same resources – oil palms require full sunlight, whereas cacao trees thrive in partial shade – so planting shorter cacao trees next to taller oil palms would not disrupt the growth of either crop.20 A recent study found that an oil palm and cocoa intercrop achieved a high land equivalent ratio (LER) of 1.44.21 In other words, if Korindo cultivates oil palms and cacao trees on separate plots, it would require 44 percent more land to achieve the same yield as it would by growing both crops on the same plot. Therefore, the company can boost its overall yield without requiring additional land.

Beyond the environmental benefits

of efficient land use, intercropping oil palms with cacao trees would also allow Korindo to capitalize on the recent surge in cocoa prices. Heavy rains and disease outbreaks have significantly disrupted cocoa production in the Ivory Coast and Ghana, which together produce 60 percent of the world’s cocoa supply.22 This supply shock has driven cocoa prices up to $10,282 per tonne, nearly quadrupling from last year.23 In contrast, palm oil prices have remained relatively stable at $863 per tonne.24 Consequently, based on the yield per hectare of each crop, a hectare of land now generates $6837 producing cocoa, compared to $2943 producing palm oil.25 By converting a portion of PT PAL from palm oil cultivation to cocoa production, Korindo could maximize its revenue without expanding its land use.

Assessing whether this strategy will increase profitability is more challenging, as the costs depend on Korindo’s implementation and local market conditions. However, given the similarities in cultivation inputs between oil palms and cacao trees, the two crops have comparable unit economics. A study conducted in

Indonesia’s Asahan Regency found that palm oil and cocoa production had gross margins of 76 and 79 percent, respectively, over 25 years.26 If Korindo executes the strategy effectively, it can boost revenue and improve overall profitability while promoting environmental responsibility.

Korindo’s plantation workers also benefit from more stable and diversified income sources. With a correlation coefficient of 0.05 over the past year, palm oil and cocoa prices are virtually uncorrelated.27 This property could protect farmers against crop-specific risks, as a drop in the price of palm oil could be counteracted by a surge in cocoa prices and vice versa. Moreover, the strategy also creates a steady flow of work since the peak harvest season for palm oil is from August to September, while cocoa harvests occur from March to July and again from September to December.28 By maintaining both oil palms and cacao trees, Korindo and its workers have harvests almost year-round, granting a steady stream of income.

Consumer goods companies that buy palm oil from Korindo would also benefit from more streamlined and resilient supply chains. Because palm

oil and cocoa are often found together in products like chocolate, many palm oil buyers also purchase cocoa. Eight of the eleven major consumer goods companies that buy Korindo’s palm oil also use cocoa in their products.29 Instead of relying on separate suppliers, companies could source both ingredients from Korindo, simplifying their supply chains. Additionally, these companies would have a more reliable supplier, as intercropping enhances resilience to pests and diseases such as the cacao swollen shoot virus (CSSVD), a leading cause of the current cocoa shortage.30 The shade that oil palms provide for cacao trees reduces the severity of the disease,

with one study showing that even only 54 percent shade minimizes CSSVD symptom severity.31 If Korindo plants cacao trees next to oil palms, the cacao trees in PT PAL would be less susceptible to the same disease that disrupted cocoa production over the past year, allowing consumer goods companies to mitigate the risk of supply shocks.

Despite these benefits, there are risks associated with intercropping oil palms and cacao trees. Cultivating two crops simultaneously complicates crop management and requires specialized expertise. Sari Himanen, Senior Scientist at Finland’s Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, emphasizes that successful intercropping requires “better knowledge on the optimal mixtures for specific production goals and local conditions.”32 To bridge these knowledge gaps, Korindo would need to invest resources into training and developing its plantation workers. Additionally, it takes three to five years for a cacao seed to mature into a cacao tree capable of producing cocoa.33 During this period, cocoa prices could drop to a point where intercropping becomes unprofitable for Korindo, especially after factoring in the initial investment in training employees and cultivating cacao trees. However, Korindo can mitigate this risk by

selling cocoa futures and locking in a price at which it agrees to deliver cocoa in the future. For instance, the company can sell cocoa futures expiring May 2025 to secure a selling price of $7,885 per tonne a year from now.34 At this price point, producing cocoa still generates more revenue per hectare than palm oil. With these tactics, Korindo can optimize its land use, mitigate financial risks, and ensure a return on sustainable investment.35 Ultimately, by aligning economic interests with environmental goals and reducing externalized impacts, this strategy can balance the interests of different stakeholders and succeed where existing solutions have failed. For Korindo, the strategy allows the company to optimize the use of its existing land in PT PAL, reducing the need for further deforestation and capitalizing on the current cocoa shortage. Plantation workers can also diversify their income streams and gain stable, year-round employment. Meanwhile, consumer goods companies gain the opportunity to simplify and strengthen their supply chains. In these ways, the proposal corrects the failures of existing solutions, creating shared value for the palm oil industry’s diverse stakeholders.36

1. What “misaligned incentive structure” continues to drive deforestation?

2. What prevents governments from passing regulations restricting behaviors that lead to deforestation?

3. What other attempts have been made to curtail deforestation? How have they succeeded or failed?

1 “8 Things to Know about Palm Oil.” WWF, www.wwf.org.uk/updates/8things-know-about-palm-oil. Accessed 7 Apr. 2024.

2 Austin, Kemen G, et al. “What causes deforestation in Indonesia?” Environmental Research Letters, vol. 14, no. 2, 1 Feb. 2019, https://doi. org/10.1088/1748-9326/aaf6db.

3 Bellantonio, Marisa, et al. “Burning Paradise: Palm Oil in the Land of the Tree Kangaroo.” MightyEarth, Mighty Earth, stories.mightyearth.org/ burning-paradise/index.html. Accessed 5 May 2024.

4 Greenpeace International, 2018, Final Countdown, https://www. greenpeace.org/international/publication/18455/the-final-countdownforests-indonesia-palm-oil/. Accessed 5 May 2024.

5 Ibid.

7 The World Bank Group, 2021, Climate Risk Country Profile: Indonesia, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/700411/climate-riskcountry-profile-indonesia.pdf. Accessed 7 Apr. 2024.

8 Meijaard, E., et al. Oil Palm and Biodiversity: A Situation Analysis by the IUCN Oil Palm Task Force, 26 June 2018, https://doi.org/10.2305/iucn. ch.2018.11.en.

6 Searle, Stephanie. “Palm Oil Is the Elephant in the Greenhouse.” The International Council on Clean Transportation, 6 June 2018, theicct.org/ palm-oil-is-the-elephant-in-the-greenhouse/.

9 Jonas, Holly, et al. International Institute for Environment and Development, 2017, Https://Www-Arcusfoundation-Org. S3.Amazonaws.Com/Wp-Content/Uploads/2017/08/12605IIED.Pdf, https://www-arcusfoundation-org.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/ uploads/2017/08/12605IIED.pdf. Accessed 5 May 2024.

10 “Sumatran Orangutan.” World Wildlife, www.worldwildlife.org/species/ sumatran-orangutan. Accessed 7 Apr. 2024.

11 Ollivaud, Patrice, and Peter Haxton. “Making the most of tourism in Indonesia to promote sustainable regional development.” OECD Economics Department Working Papers, 7 Feb. 2019, https://doi. org/10.1787/18151973.

12 BPS-Statistics Indonesia, 2023, IndonesianEconomicReport, 2023, https://www.bps.go.id/id/publication/2023/09/21/ a62efbad86d18bc35581c33a/laporan-perekonomian-indonesia-2023. html. Accessed 5 May 2024.

13 “Does the RSPO Have a Future?” Thepalmoil.Com, 13 Jan. 2021, www. thepalmoil.com/does-the-rspo-have-a-future/.

14 Yu, Lengkhor. 2020, Sustainable Palm Oil: Trade and Key Players between Indonesia and China, https://www.proforest.net/fileadmin/ uploads/proforest/Documents/Publications/sustainable-palm-oil_tradebetween-indonesia-and-china-1-2-1.pdf. Accessed 7 Apr. 2024.

15 Yeo, Carol. “ACOP 2022: CSPO Production Hits 15 Million Mt Milestone.” Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), 29 Sept. 2023, rspo.org/acop-2022-reports-continued-progress-in-cspo-productionand-consumption-despite-global-disruptions-cspo-production-hits-15million-mt-milestone/.

16 Greenpeace International, 2018, Final Countdown, https://www. greenpeace.org/international/publication/18455/the-final-countdownforests-indonesia-palm-oil/. Accessed 5 May 2024.

17 Brandi, Clara, et al. “Sustainability Standards for Palm Oil: Challenges for Smallholder Certification Under the RSPO.” The Journal of Environment&Development, vol. 24, no. 3, 22 July 2015, pp. 292–314, https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496515593775.

18 Yu, Lengkhor. 2020, Sustainable Palm Oil: Trade and Key Players between Indonesia and China, https://www.proforest.net/fileadmin/ uploads/proforest/Documents/Publications/sustainable-palm-oil_tradebetween-indonesia-and-china-1-2-1.pdf. Accessed 7 Apr. 2024.

19 “Growing Cocoa.” InternationalCocoaOrganization, International Cocoa Organization, 14 Sept. 2021, www.icco.org/growing-cocoa/.

20 Ibid.

21 Khasanah, Nikmatul, et al. “Oil Palm Agroforestry Can Achieve Economic and Environmental Gains as Indicated by Multifunctional Land Equivalent Ratios.” FrontiersinSustainableFoodSystems, vol. 3, 21 Jan. 2020, https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00122.

22 Kimball, Spencer. “Cocoa Prices Are Soaring to Record Levels. What It Means for Consumers and Why ‘the Worst Is Still Yet to Come.’” CNBC, CNBC, 26 Mar. 2024, www.cnbc.com/2024/03/26/cocoa-pricesare-soaring-to-record-levels-what-it-means-for-consumers.html.

23 Refinitiv. Accessed 26 April 2024.

24 Ibid.

25 Fahmid, I M, et al. “Competitiveness, production, and productivity of

cocoa in Indonesia.” IOPConference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, vol. 157, May 2018, pp. 12–67, https://doi.org/10.1088/17551315/157/1/012067.

26 Nasution, S. K., Supriana, T., Pane, T. C., & Hanum, S. S. (2019). Comparing farming income prospects for cocoa and oil palm in Asahan District of North Sumatera. IOPConference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 260(1), 012006.

27 Refinitiv.

28 Christina, Bernadette, and Fransiska Nangoy. “Indonesia Palm Oil Industry Urges Government to Ease Export Curbs as Harvest to Worsen Oversupply.” Reuters, Reuters, 15 July 2022, www.reuters.com/markets/ commodities/indonesia-palm-oil-industry-urges-govt-ease-export-curbsharvest-worsen-2022-07-15/.

29 Greenpeace International.

30 Kimball, Spencer.

31 Andres, Christian, et al. “Agroforestry systems can mitigate the severity of cocoa swollen shoot virus disease.” Agriculture,Ecosystems& Environment, vol. 252, Jan. 2018, pp. 83–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. agee.2017.09.031.

32 Himanen, Sari, et al. “Engaging farmers in climate change adaptation planning: Assessing intercropping as a means to support farm adaptive capacity.” Agriculture, vol. 6, no. 3, 29 July 2016, p. 34, https://doi. org/10.3390/agriculture6030034.

33 Stevens, Alison Pearce. “How to Grow a Cacao Tree in a Hurry.” Science NewsExplores, Science News Explores, 3 Dec. 2019, www.snexplores. org/article/how-grow-cacao-tree-hurry.

34 Refinitiv.

35 “Return on Sustainability Investment (ROSITM) Methodology.” NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business, NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business, www.stern.nyu.edu/experience-stern/about/ departments-centers-initiatives/centers-of-research/center-sustainablebusiness/research/return-sustainability-investment-rosi. Accessed 5 May 2024.

36 Porter, Michael E., and Mark R. Kramer. Harvard Business Review, 2011, pp. 62–77, CreatingSharedValue.

Photo Credits:

• Olga/AdobeStock–Page 21

• Junaidi Hanafiah/Wikimedia Commons–Page 22

• Tanarch/AdobeStock–Page 23

• Mercury Studio/AdobeStock–Page 24

“The most surprising part of my research was realizing that intercropping isn’t just environmentally friendly—it actually makes better financial sense for producers... Interviewing the high school alum who first introduced me to this issue was especially rewarding; it felt full circle, as his insights brought my research to life and deepened my understanding of sustainable solutions.”

Joint Liability Groups, Social Impact

Bonds, and Synchronized Repayments

Author Aryan Luniya highlights how tailored financial mechanisms, such as Joint Liability Groups, Social Impact Bonds, and synchronized repayment schedules, can improve microfinance access and support socioeconomic development in rural Rajasthan. The paper suggests that aligning financial services with local conditions, such as agricultural cycles, can reduce default rates and foster sustainable growth.

The rural areas of Rajasthan experience severe financial marginalization, which hinders socioeconomic growth. In other words, many people do not have access to basic financial services, which negatively impacts the growth of agriculture and entrepreneurship. Due to their restricted lending capabilities, microfinance institutions (MFIs) frequently struggle to satisfy the demand for credit in rural areas. To improve financial inclusion in these locations, this essay looks into novel financial mechanisms that could strengthen the capabilities of MFIs. With synchronized repayment plans emerging as the most viable solution, the essay evaluates the implementation of Joint Liability Groups (JLGs), Social Impact Bonds (SIBs), and repayment plans synchronized with agricultural output cycles to successfully increase credit availability and foster socioeconomic development of Rajasthan’s rural communities.

A Joint Liability Group, or JLG, is a small organization of 4-10 individuals who mutually guarantee each other’s loans from a bank. The JLG offers an effective method of reducing loan defaults and directly impacting the availability of microfinance funding since loan success is based on the principle of borrowers in a particular rural setting holding each other accountable. According to the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), India’s overall growth rate stands at 44.86 percent in terms of the number of JLGs formed and 60.73 percent in terms of JLG loans disbursed in the past decade.1 While this group solution has already been implemented, there is still room for expansion. Since this is a model that has been tested already, it reduces the level of risk when it is applied to different settings across and outside India.

The JLGs that Arth Microfinance, a local microfinance institution in Rajasthan, has established are a prime example of generating shared value in microfinance. Economist Michael E. Porter explains, “Creating shared value, not just profit per se, must be the redefined purpose of the corporation.”2 By using JLGs in a manner that engages borrowers and creates a sense of social security, Arth Microfinance has strengthened its own financial sustainability and improved community welfare by strategically converting a societal need into a business opportunity.3 Ruchi Mitra, a director at Arth Microfinance, posits, “In Rajasthan’s remote villages like Barmer and Sikar, the problem isn’t just the absence of banking facilities but also the cultural norms that discourage women from engaging with financial institutions.”4 This credit not only helps poor women to grow economically but also improves gender equality, the status of women within the family, their health, and their education level -- thus creating shared value.5

The use of JLGs is especially important in Rajasthan’s rural hinterlands. Here, old informal credit systems frequently trap the impoverished in debt, and there are few regular banking services available. Nearly 4,000 villages in the state, each with populations of over 2,000, lack banking facilities, leaving out a large chunk of people from accessing the benefits of financial services.6

To combat this, Porter suggests that “Corporations can generate shared value by implementing policies and operating practices that enhance a company’s competitiveness while simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the communities in which it operates.”7 The incorporation of JLGs into this socioeconomic environment creates a compelling story of shared values, in which social improvement is both the engine and the beneficiary of economic progress, and aligns with Porter’s theory that long-term economic growth requires the alignment of corporate and societal interests.8

The Return on Sustainability

Investment framework (ROSI), a tool from the NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business, can be utilized in the context of Arth Microfinance to determine the concrete effects of JLGs on the organization and the community.9 Because members of a JLG have a mutual stake in one another’s creditworthiness, these effects range from better risk management to increased operational efficiency due to lower default rates and more efficient loan distribution procedures. A statement in line with ROSI principles was made during my interview with Arth Finance Director Ruchi Mitra, who said, “Our adoption of JLGs has resulted in remarkable repayment success due to trust, which is critical for our ability to extend further credit and stabilize our financial position.”10

Stronger communal relationships can result in operational efficiencies and social license, and these improved community ties translate into trust. In rural financial systems, where information asymmetry and efficient resource allocation challenges persist, trust is a vital resource. Strong community ties, made possible by JLGs, lead to a trust economy that eases the flow of resources and financial services and is essential to the success of any microfinance program.

Arth’s JLG model exemplifies a careful analysis of the area’s socioeconomic structure and a customized financial solution that fosters economic empowerment. This approach has a twofold advantage: members of a JLG are motivated to maintain group financial accountability, which creates a link between social cohesion and economic viability. Due to its provision of financial inclusion, this approach automatically complies with Sustainable Development Goal 1, No Poverty, and Sustainable Development Goal 8, Decent Work and Economic Growth, which promotes self-sufficiency and microenterprise. While JLGs have demonstrated substantial benefits in promoting financial inclusion and community cohesion, they are not without drawbacks. One significant disadvantage is the potential for increased social tension and conflict among group members. This arises particularly when individual members fail to meet their financial obligations, burdening others within the group to cover the shortfall. While this collective responsibility model effectively reduces default rates, it can strain interpersonal relationships and lead to social ostracization or even conflict.

Implicit bias, too, is inherent in human decision-making. As discussed by Anthony Greenwald in his exploration of implicit associations, such bias can influence group dynamics negatively. Greenwald contends, “The best theory of how implicit bias works is that it shapes conscious thought, which in turn guides judgments and

decisions.”11 For example, members may harbor unconscious biases against individuals based on socioeconomic status or background, affecting group cohesion and cooperation. Such dynamics can undermine the social cohesion that JLGs aim to build, ultimately affecting the group’s effectiveness and the overall stability of the microfinance initiative.

To mitigate social tensions within JLGs, a comprehensive approach focusing on group dynamics and support is essential. Careful selection of group members with similar financial behaviors and trust levels, combined with conflict resolution training, can enhance group cohesion. Regular, transparent communication and flexible repayment options can alleviate financial pressures and prevent conflicts. Additionally, establishing support networks, including access to emergency funds and financial counseling, and implementing routine monitoring and feedback mechanisms ensures that groups function effectively while providing a safety net for members facing difficulties. These strategies collectively help maintain harmony within JLGs and improve their overall success.

In social entrepreneurship, Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) are a novel method because they utilize an external party to increase the flow of funds, which is useful, especially when it comes to tackling the problems of financial exclusivity that are common in rural Rajasthan. SIBs can facilitate improved microfinance services by utilizing private resources for public benefit. This aligns with the interests of investors and the community, thereby positively influencing the socioeconomic environment of the region. The fundamental tenet of SIBs is that private investors finance developmental initiatives in anticipation of receiving a return on their investment, subject to the achievement of predetermined

social outcomes. This connects investor rewards with concrete community benefits and guarantees attention to quantifiable social outcomes. According to Information Technologist Samer Abu-Saifan, “Social entrepreneurship incorporates endeavors that are directly tied with the ultimate goal of creating social value.”12 SIBs do the same by linking financial success to social advancement.

The implementation of SIBs in Rajasthan may be primarily focused on increasing the accessibility of microfinance. For example, financial inclusion could be improved by providing financing to support the introduction of mobile banking technologies in isolated areas. Improved loan repayment rates

“...INDIVIDUAL MEMBERS FAIL TO MEET THEIR FINANCIAL OBLIGATIONS, PLACING THE BURDEN ON OTHERS WITHIN THE GROUP TO COVER THE SHORTFALL…”