“Rethinking and Repositioning transformation within the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT)’s One Smart Vision 2030 Strategy”

“Rethinking and Repositioning transformation within the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT)’s One Smart Vision 2030 Strategy”

Rethinking and Repositioning transformation within the Cape Peninsula University of Technology

One Smart Vision 2030 Strategy

5 AUGUST 2021

MODERATOR

Ms Brightness Mangolothi

Director: HERS-SA

A transformation webinar on “Rethinking and repositioning transformation within the Cape Peninsula University of Technology’s (CPUT’s) One Smart Vision 2030 Strategy” was held on 5 August 2021 as part of the Vice Chancellor’s Transformation Seminar Series organised by the Centre for Diversity, Inclusivity and Social Change in the Vice Chancellor’s Office.

The webinar was moderated by Ms Brightness Mangolothi, Director: HERS-SA.

Director: HERS-SA

The objectives of the seminar were:

• To reposition transformation within CPUT’s One Smart Vision 2030 Strategy;

• To unpack the idea and practice of transformation in the higher education context from a number of perspectives; and

• To rethink and reposition decolonization as an academic project and in relation to issues of visual redress and responsiveness to local, national and global contexts.

The transformation webinar was held as the first in a series of virtual seminar series which sought to create a space for engagement and critical thinking on the topic of transformation to promote a student-centered environment at CPUT.

Prof Chris Nhlapo Vice-Chancellor: CPUT

Transformation as a form of social change is a complex process entailing the interaction of many, various factors along a desired trajectory. In order to foster transformation effectively, a heuristic and critical framework must be developed which recognises the multidimensionality, interconnectivity and interrelational nature of the kind of change being sought. The complexity and widespread nature of the transformation challenge being faced also requires that CPUT, as an institution which cannot be divorced from the society in which it is embedded, adopts a multistakeholder approach.

For CPUT as a university of technology, the issue of transformation should be seen in the context of the development of the higher education sector since the introduction of democracy in 1994, as well as in relation to the establishment of a national system of innovation since then. The post-school sector has shifted from a racialized and fragmented framework to a more integrated one featuring 26 public universities which are categorised as either “traditional”, “comprehensive”, or, like CPUT, as universities of technology. The process of integration has also seen the establishment of 50 technical and vocational education and training colleges (TVETs) and widespread workbased training under 21 Sector Education and Training Authorities (SETAs). The establishment of employment-oriented further education was bolstered in 1996 with the production of a White Paper on Science and Technology. This document gave life to the idea of a national system of innovation, which is now part of the public discourse, and has fostered the establishment of a framework for

development at both the regional and provincial levels within which CPUT operates.

Although the pursuit of an integrated South African system to promote innovation has stalled over the past 30 years relative to the advances made in other countries with comparable economies, such as India and Brazil, the national higher education system in general is mature and quite developed. In this context, CPUT must attend not only to its internal dynamics, but also to its larger role in the post-school education and training (PSET) system. Furthermore, as an African university, CPUT must not only pursue knowledge for its own sake but also for the amelioration of the conditions and lives of ordinary men and women. In this regard, it must be fully committed to participating in the nation’s social transformation, economic modernisation and upskilling.

Accordingly, transformation at CPUT should help the university to become an anchor institution in society; enhance its

contribution to the PSET sector in terms of original and applied research; and align its goals more closely with those established at the national level for higher education. In this regard, the institution’s demographics indicate that significant progress has already been made. There are more women than men at CPUT; and there are four female deans to two male deans. However, much remains to be done in relation to efficiency, good governance and Africanisation at the institution. Greater efforts should be made to decolonise the curricula and address epistemic violence; promote equitable success; improve facilities; create more equitable representation among the academic staff; and enhance social inclusion across the institution. CPUT must take action to produce greater transformation even as this entails embracing uncertainty. Only in this way can it take control of its future and become the leading technological education body in Africa, as well as an anchor institution which contributes to local economic development and the national system of innovation.

Student-centeredness is crucial to the implementation of the principles of oneness and smartness that underpin CPUT’s One Smart Vision 2030. The university’s philosophy of student-centeredness can mean many different things at different points in the life of the institution. In relation to the university’s administration, it entails shifting control into the hands of the students rather than the administrators. In this respect, if the focus of the university as a social space is for students to engage and study, then they should not be spending hours waiting in queues outside administrators’ offices. Smart systems can be deployed to ease the administrative burden and free students from such queueing.

In the teaching and learning space, studentcenteredness entails shifting the balance of power from the supervisors and lecturers to the students in terms of resources, access to information, egos and the pedagogy itself. The principles of diversity and inclusivity are fundamental principles that should shape the politics of learning. Much was learnt by the institution in this regard under the Covid-19 pandemic as it prioritised saving lives and exhorted staff to “leave no student behind”. Although the slogan became something of a cliché during this period, efforts to realise it led to a deeper understanding of who the students are and their backgrounds. In seeking to provide education digitally to everyone, the university grappled not only with the issue of inequitable access to technology and connectivity due to economic circumstances and/or a lack of proper infrastructure in some of the students’ neighbourhoods – but also the issue of student living environments which were not conducive to learning, for example, as a result of overcrowding or the threat of violence.

These material realities became quite evident during the pandemic and were increasingly taken into account by supervisors and lecturers in their pedagogic practices as they sought to ensure that learning took place. Recognition of these realities also produced a new view of how technologies may need to be implemented to ensure equitable access, particularly in relation to digitally provided education. So, for example, the university purposefully adopted a low-tech approach to ensure genuinely democratic educational provision under the pandemic. In this regard, one of the lessons for CPUT’s One Smart Vision 2030 has been that technology cannot be embraced at

Teaching and Learning

the expense of the students and who they are and where they come from, or more broadly at the expense of poor and marginalised communities, if it is to produce genuinely inclusive developmental benefits.

Meanwhile, work has continued in support of the university’s role as an institution which is actively engaged in its society and which seeks to meet the needs of its students. Much of this work has been undertaken over a long period already. These efforts have included involving students in community-related work as part of the university’s function as an anchor institution among local communities. For example, during the pandemic, CPUT adopted a proactive role as a vaccination centre, with students from the Department of Nursing Science in the Faculty of Health and Wellness Sciences working to keep local people safe and inoculating hundreds of individuals from neighbouring communities against Covid-19. The university has also launched a number of initiatives to address and combat gender-based violence (GBV) within the institution and beyond the campus gates.

In seeking to produce teaching and learning that resonates with student experiences, CPUT is working to forge and implement a more inclusive language policy, working within faculties on the ground floor to this end. It has further launched a curriculum renewal project, as part of which it is starting to develop new qualifications.

The aim is to decolonise curriculum in line with the kind of university CPUT is seeking to become and the kind of graduate attributes it would like to engender. The institution is also attending to the so-called “second curriculum”, that is the surroundings, the places outside the classroom, such as the social spaces and libraries, where learning also happens.

Another key focus for the institution is the provision of student support services and educational programmes that foster employability and entrepreneurship, producing graduates who can make a contribution to the economy. The approach is to develop engagement among students, industry and staff, encouraging them to work together as a collective. The university is also seeking to foster a more inclusive intake. For example, it has launched a programme that supports the teaching of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) to pupils in neighbouring schools. In addition, it has held workshops for pupils in District Six to let them know about CPUT.

The One Smart Vision 2030 has provided new impetus to all these efforts, including through the establishment of a range of dedicated student-support programmes offering work experience, mentorship from tutors, educational engagement from peers, and employment and leadership opportunities. In addition, the university is increasingly looking at how data analytics may best be deployed to help students in new ways – for example, in identifying and addressing any educational challenges that they may face at an early stage.

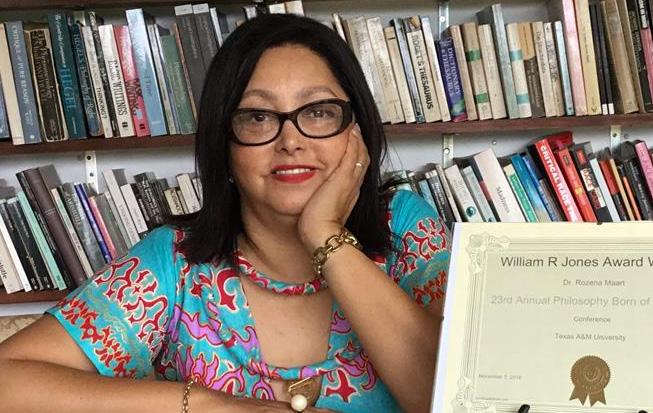

Prof Rozena Maart

UKZN Academic and Transformation expert

In seeking to shift the geography of reason for students, it is crucial that they come to know African thinkers. They will be better equipped to be producers of knowledge if their lecturers have considered the buried history of South Africa and seek to share this understanding with them – an intellectual history that may be found in the thinking of Steve Biko, Anton Lembede and Charlotte Maxeke, and the pan-Africanist political philosophers who inspired them, including WEB Du Bois 1 and Frantz Fanon. Maxeke, for example, travelled to the United States (US) in late 1800s where she became the first black South African women to acquire a PhD in philosophy while studying under Du Bois. The intellectual tradition is a rich one, informed by diverse influences both old and modern, including Black existentialism, the writing of AfricanAmerican philosopher Leonard Harris and the thinking of Indian post-colonial theorist Gayatri Spivak.

1 Du Bois is known for his work on double consciousness, that is, how the black man sees himself and how he sees himself being seen

At the same time, the current efforts to promote transformation and decolonisation in pursuit of the university’s Vision 2030 and as part of its efforts to create “One Smart CPUT” comes at a critical moment in the wake of a pandemic which has inhibited “in-the-flesh” contact and communication since March 2020. In this regard, the present discussion is taking place in an environment in which the personal has been largely removed. This is a challenge, since the “in-the-flesh” and personal are crucial to any drive to achieve genuine transformation.

Accordingly, and in an effort to produce a truly transformative discourse, I must tell my own story. I was born and brought up in the District Six area of Cape Town and was influenced by black consciousness as a child after I and my family were forcibly removed to Lavender Hill in 1973, when I was 11. My name, Maart, meaning the month of March, also indicates a history of oppression, marking the point of enslavement of one of my ancestors. My grandfather was a Xhosa man from the Eastern Cape. His past and that of his ancestors speak to the history of colonisation in South Africa: the Dutch

had colonised Bengal, Indonesia and Mauritius before they arrived in the Cape with the intention of exploiting the labour of the enslaved from these colonies to establish a halfway station on the way to India. The plan was that this station would provision their ships and feed the local colonisers. My grandmother was a Hindu of Bengali and Indonesian heritage who was not allowed to marry my grandfather, with whom she had 10 children (although she did so in later life). My grandmother was a September and my grandfather was a Maart. I have never changed my name, although others have.

When I talk about the history of the forced removals undertaken by the apartheid regime, I am talking “in the flesh” as someone who was and remains affected by them. Every year on August 4, the anniversary of my family’s forced removal to Lavender Hill, I come out in psychosomatic hives. Even before the forced removals, as a young child, I saw the psychological and physical damage wrought by apartheid in my community. Thus, I talk about the “politics of the flesh” – the material impacts of apartheid which affected me as a child and which persist to this day.

In a similar vein, it is no accident that the anti-apartheid South African Student Organisation (SASO) emerged through the agency of Biko and so many other young men who were afforded the possibility of education in the non-European section of the former University of Natal Medical School, where matters of the flesh and materiality were central concerns. In this regard, it is noteworthy that the revolutionaries and thinkers who continue to inspire us at this point in our lives in South Africa include and are influenced by Biko, Fanon and Che Guevara, who were all medical doctors. These scholarpractitioners understood that the material conditions under which we live determine how we exist in the world as well as the length of our lives. Indeed, when Biko talks about materiality, he draws on the work of the German physician and philosopher Karl Jaspers who pioneered

the biographical method of psychiatric practice. In this context, Biko not only reflects on the racialisation and usurpation of consciousness which we continue to experience in the afterlife of apartheid, he also presents a critical method which we can apply to understand our history – a method that emphasises the importance of analysing the kind of history which we are taking into the present and with which we envisage the future. In this regard, I am here to share my own experience, my own personal history, in part as an example of how an existentialist approach can be employed to meet the demands of pedagogy in our current situation.

After Nelson Mandela was elected president in South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994, the government which he led sought to actualise the vision of the Freedom of Charter which was penned

in 1955. Forty years later, in 1995, the Education White Paper 1 on Education and Training started the process of addressing education in line with the principles espoused by the Freedom Charter. In July 1997, Professor Sibusiso Bengu, who was the minister of education at the time, noted that the transformation of the higher education system should reflect the changes in South African society and should strengthen the values and practices of its new democracy. He said that such transformation was “not negotiable” but that the journey to achieve it would be hard. The position adopted by the government was that transformation of higher education was required to redress past inequality; to serve a new social order; to meet pressing national needs; and to respond to new realities and opportunities. In this spirit, the 1995 White Paper outlined a framework for change in

which higher education was to be planned, governed and funded as a single national coordinated system, thus overcoming the fragmentation, inefficiency and inequality which were among the legacies of the past; and with the goal of creating a learning society that could release the intellectual and creative energy of the whole population towards meeting the goals of reconstruction and development.

However, the documents from this period, as with many others produced during the national liberation struggle, failed to address the issue of agency. This is a crucial omission given that a document or the allegiance pledged to a particular document, or even the production of legislation, does not guarantee that the sought-for change framed in words is going to take place. In this regard, the state can legislate for or against almost anything but it cannot legislate for the adoption of particular attitudes. Indeed, the anticipation of such attitudinal change has been one of the greatest impediments to transformation in South Africa – after 1994, we expected attitudes to change and they didn’t. My position is that one of the reasons for this is that the attitudes themselves have not been called into question and the issues of the kind of work we should be doing and the agency through which this should be undertaken have remained largely unaddressed.

In talking of the power and importance of autobiography, I must invoke the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who is a key figure despite what he says about Africans – that we have no memory because we do not speak European languages. Many radical thinkers, especially those who have produced black consciousness and PanAfrican ideologies, refer to Hegel and his idea of the phenomenology of the mind or the spirit.

The concept is crucial in that it proposes an understanding of reality that is based on the agency and consciousness of the individual. It is for the individual to take stock of who they are, where they come from, how they have entered the country that they now call home, and how their belonging has been secured in the Constitution. In this regard, I must say that I am not a fan of the Freedom Charter. Robert Sobukwe walked out of a key meeting at which the Freedom Charter was being forged and rejected the document as offering a false idea of “freedom” – a conceptualisation that was predicated on securing the position of the coloniser rather than liberation from the coloniser.

Similarly, in the present debate on decolonisation it is important that we ask ourselves why we are engaging in this process, in other words from what and from whom are we seeking to decolonise ourselves. Questions must also be asked about the nature of the process, that is, how the decolonisation efforts are being undertaken. In whose language and framed by whose culture?

Such questioning is crucial, given that, to date, the decolonisation efforts have failed to remove the coloniser. Few white South Africans have taken on the responsibility of recognising both morally and ethically that their livelihoods and belonging derive from the actions of their forefathers who came into the Cape uninvited, even though these same contemporary South Africans remain, as Biko noted, “beneficiaries” of this past and agents of the system it established. In this regard, it is not enough simply to declare that you are a white South African. As critical race studies scholar Paul Gilroy notes, it is not so much who you are, but where you are at; and, in South Africa, that entails recognising that the privileged position of 10% of the population who own 88% of the land and wealth is a product of historical racism.

In this regard, the country is still living in the afterlife of apartheid. Transformation remains necessary because the redress that led to and succeeded the introduction of democracy in 1994 has not been equitable or even in the interests of the majority, of the masses. It was based on negotiation politics. But negotiation cannot and should not be the basis for the advancement of fundamental human rights. No woman should be expected to tell her rapist: “Don’t rape me every day, just rape me once a year!” So, 25 years later, we now need to look at how to reshape the trajectory.

In this regard, decolonisation should not be seen as an ivorytower academic project, or about decolonising the curriculum in isolation; it is about recognising that democracy was introduced in South Africa on the basis of inequality. Historical racism does not go away overnight. It is a legacy which remains part of the present problem.

In addressing this legacy, transformation will never be a smooth path. It entails asking personal questions. So, for example, if you have a friend or partner who does not take ethical responsibility for their position of privilege in this society, you know there is a problem. A certain level of self-consciousness is required; and although the selfexamination and self-interrogation required to attain this may not come easily, it is entirely necessary given the country’s history.

Shortly after joining the University of KwaZulu-Natal in 2011, I held an event to celebrate Biko’s legacy at which I learnt that a number of “freedom’s children” did not know who he was. As a result, a Steve Biko education project was launched engaging pupils from 14 local high schools in an effort to understand what was being taught about him and to foster an understanding of his contribution to the country as a scholar-activist who drew on the négritude movement, including the works of thinkers such as Aimé Césaire, Léopold Senghor and Léon Damas. Biko’s theorisation of black consciousness as a form of self-reflection and as a way of understanding how one lives in the world can usefully inform contemporary efforts to make South Africa the kind of country in which we want to live. If we are to advance decoloniality and accept our ethical responsibility to take up transformation, we must look inward as well as outward.

In reflecting on the democratic dispensation established under the Constitution as well as CPUT’s One Smart Vision 2030, it is important to recognise that any document can make promises, but it is the implementation of that document which determines whether it will produce the better life that it envisages. In this regard, close consideration of the strategy that CPUT plans to adopt to implement its vision is necessary.

The focus of the strategy is to promote human-centricity through a community of smart people at the institution who

adhere to a philosophy of ubuntu. The “smartness” dimension focusses on technological developments. The vision statement talks about how CPUT plans to transform its students with the support of world-class researchers who will inspire cutting-edge knowledge-production and innovation. However, in order to implement the “smartness” dimension of the vision, the university will need to interrogate more closely what the next phase or decade of technological change on the continent will bring, bearing in mind the importance of the human dimension and equitable development in deciding the kinds of future technology that it wishes to promote.

The values of CPUT – kindness, restoration, unity, passion and accountability – will be central to the realisation of the institution’s One Smart Vision 2030 and the processes of transformation and decolonisation that this will necessarily entail. In this regard, the first question that should be asked is: What are we thinking? Do all of the staff know what the students are thinking? Are all staff members acquainted with the different ideologies and politics of students across the spectrum, including those inspired by black consciousness and Pan-Africanism, as well as those underpinning the political programmes of parties and political groupings such as the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and Black Lives First (BLF). In seeking to answer these questions, greater understanding may be fostered about the ways of rethinking that are required to produce genuine transformation.

In this regard, one of the problems faced by South African students is that the curriculum itself has not changed that much since apartheid, although its elements have been shifted around. In addition, a number of key challenges relating to the pedagogy of teaching and learning have persisted. For example, how can students be expected to be Africans and South Africans in the fullest sense of these identities, if they are not learning African and South African knowledge? What forms of identity are being promoted in a system which privileges the received pronunciation acquired at Model-C schools over African languages? The message is clear: Black students are expected to become members of a new, modern group of black people, as their former cultures and identities are denied, along with the history of South Africa.

In response to such an immediate threat, we must be mindful and ask ourselves where and what we are thinking. For example, can we realistically claim that it possible to think freely in places and at institutions where we dare not even think? In whose language are we thinking after all? To what extent is our thought actually being shaped by imposed rules of grammar and punctuation? Such questions must be asked given the use of English as the language of colonisation – a language through which the settler sought to regulate the native by forcing them to express themselves in particular ways.

With the adoption of English as the medium for pedagogy, the expectation is that the population should think in

the language of the coloniser; and, as Fanon says, when someone thinks in the coloniser’s language they are upholding the civilisation of that language. This dictum is not intended as a prohibition against speaking the coloniser’s language, whether that be, for example, French or English, but rather an expression of the idea that languages – especially European ones – are created as vessels for their civilisation.

In this context, it is unsurprising that many South Africans find it difficult to express their views on the operation and perpetuation of racism, which is a crucial aspect of any system of white domination. It is difficult not because we cannot find the words to say it but because we are constantly reminded that we don’t speak properly, that we must tone it down. However, as someone seeking to tell the truth, to tell my truth, I cannot and should not mince my words. Indeed, although I and my co-workers pursuing transformation cannot rewrite the Freedom Charter or the Constitution, we have an ethical and moral responsibility to tell the truth as we see it – and in identifying the challenges that we face in the afterlife of apartheid to take what action we can.

In taking action it is important to learn from the past, including the mistakes that our forebearers made. One of the biggest of these has been the production of the belief that, since 1994, we actually have freedom. We tell our children all the time that they are “freedom’s children”. However, some of my students ask: “But where is my freedom?” The question is posed because freedom is an absolute. So, when those in power say, “here is a little bit of freedom and you can have the rest in 10 years’ time as long as you behave yourself”, they are making a false claim. The illusory nature of the freedom on offer becomes apparent the moment that the students show a little bit of discontent. They are condemned by the country’s academic leadership as “hooligans” and told to toe the line. But

this is a leadership which has forgotten or fails to understand that the national liberation struggle was actually pushed forward by student protests – and that without their student bodies, universities have no future.

So, we need to think about how we think. How are we making meaning of the world? As we reposition ourselves, what are we repositioning from? What does the repositioning mean? We should not accept mere cosmetic change, as many students have realised; and we must understand the range of options for repositioning from among the spectrum of political and ideological positions which are present on CPUT’s campuses, including those with which we may not be that familiar.

Transformation has and will always be an aspiration, particularly for those who have committed themselves to changing their universities through changing the ways that they teach and the ways that students learn. As the students have made plain through the #KingGeorgeMustFall protests at the University of KwaZuluNatal, the #RhodesMustFall protests at the University of Cape Town and the nationwide #FeesMustFall protests, they are not prepared to be confronted by the remnants of apartheid – unlike their parents and grandparents who, as pupils, were given the day off every April 6 so that they could celebrate the arrival of Dutch colonist Jan Van Riebeek in Cape Town.

In looking at transformation in the tertiary sector, it is important to consider the components of education and how these should be reshaped so that better thinkers can be produced. To this end, critical thinking must be encouraged. For example, if students are unable to critique their lecturers, then the university is failing in its responsibility to equip the thinkers and leaders of the future with the understanding and skills required to take the country forward. In this regard, it must be remembered that students

are the backbone of every society and that, in South Africa, their engagement with their institutions and the nation at large is based on a tradition of scholar activism in which student and political movements derived inspiration from each other across time and space. Thus, the establishment of SASO as a part of the Black Consciousness movement was influenced by events taking place elsewhere, including the rise of Black Power in the US and the student protests on the streets of Paris in 1968; as well as by the earlier history of Pan-Africanism in South Africa which was shaped by the independence struggles in other parts of the continent and the thinkers in the négritude movement. In this context, pavement politics have been an important part of student activism for a long time; however, in contemporary South Africa, students are castigated as “unscholarly” when they to take to the streets to perform their discontent.

An important aspect of transformation is the relationship between race and place. Spaces which are conducive to learning must be created. When students walk down the corridor, they should be able to see images of African scholars such as Anton Lembede and Charlotte Maxeke, for example. Which is not to say that Marx, Foucault and other key European thinkers should not be taught, but rather that the myth that the knowledge historically produced in Europe is universal in nature should be deconstructed. So, for example, the bias in South African philosophy departments towards thinkers from just three countries – France, Germany and the US – should be corrected. There are 54 countries in Africa, all of which have produced important thinkers who are studied across the continent. For example, philosophy undergraduates at the Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar (UCAD) in Senegal, which boasts a 10,000 strong student cohort, study not only Senegalese thinkers, but scholars from across Africa who have made a contribution to life on the continent.

In considering how best to achieve transformation, it seems clear that transformation practitioners should not only produce a vision of their ideal destination, although that is crucial, they should also consider the steps that must be taken to arrive there. In this regard, CPUT should seek to create an educational setting that actively fosters the values that it espouses, such as unity, restoration and technological progress. Students thrive when they are learning in an environment which allows them to bring their own reading, their books by Lembede, Fanon and Biko, into the classroom even when these texts may not be on the book lists issued for the course in question. A comprehensive technocratic consciousness cannot be advanced without advancing and understanding the history of consciousness in South Africa more broadly. The aim should not be merely to equip students with a degree certificate, but rather to offer genuine education. This must entail recognising that students should learn their own history. To this end, the university should seek to establish an archive where students can go and take out a box, file or row of articles written by key African thinkers such Kenyan environmental and feminist activist Wangari Maathai or Ugandan political scientist Mahmood Mamdani. Such thinkers should not only be invoked as the heroes of student protests, they should be studied and their thought should be extracted as the basis for the further development and expansion of African knowledge.

In a sense, the task for CPUT is to move beyond seeing itself only as a university of technology and instead to seek to expand the thinking of its students more broadly, although with a focus on technological development. If higher education is framed in this way, the power struggles over the mission of higher education which have divided universities in South Africa may be resolved. In addition, the existing gatekeepers of the curriculum would no longer be able to denounce thinking by students with which they disagree. Indeed, their power as gatekeepers, which is founded on an exclusionary historical model for education, would be eroded. Instead of being criticised by lecturers for engaging in “unfeasible” forms of analysis, students would be invited to undertake their intellectual and educational journeys in the context of their own identities, cultures and histories.

In this regard, one way forward is to consider models informed by critical thinking or critical race theory. Critical thinking is undertaken when what is understood as “thinking” has failed to answer critical questions. In part, such failure can be because critical questions are not easy to answer. They can evoke uncomfortable or difficult responses.

Adopting a critical thinking approach, the university would have to be radical in its implementation of its One Smart Vision 2030 strategy. For example, critical pedagogy

demands that the buried history of South African scholars who are not generally taught must inform the curriculum. At the same time, as the case of Mahmood Mamdani at UCT showed, implementation of such an approach requires resolve. Prior to 1994, the university had asked Mamdani to devise a course on African studies. However, the course that he outlined contradicted academic expectations of the kinds of knowledge that were considered feasible for black students to learn. The course was refused and Mamdani, who is a world-renowned scholar, was forced to go. The case illustrates the depth of resistance to education that seeks to foster a particular kind of consciousness and awareness of who we are.

Nevertheless, and although it has not been possible to overturn the long history of masterdom and colonisation in South Africa in the few decades since the introduction of democracy, we should seek to envision a future of genuine liberation in which South Africa is part of a larger continent. This entails teaching the students not only about South African knowledge and history, but also about the broader continent. For example, many students are unaware of the massacres of the Herero in Namibia in 1903-1907 by the German Second Reich simply because this hasn’t been taught. In this regard, it is important to realise that the more we suppress African knowledge, the less able we will be to produce African knowledge.

African thoughts and ideas can only be cultivated if the ground for the creation of such knowledge is prepared. However, a better future for higher education can be achieved if we provide the right spaces and materials and if we put our minds together and ask ourselves critical questions about our history and our present – recognising that in order to create a better future we cannot forget our history.

All higher education stakeholders – managers, Council members, private-sector interests, the government, the staff and students – have a role to play in transformation. The #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall movements indicated the extent of the student drive to change the status quo, which will continue. Now, a measured approach to transformation is required at CPUT, based on a comprehensive review of the university’s policy documents, which are presented to all students when they arrive at the institution. To this end, a conference should be held to consider the existing policies and whether they speak to transformation and promote Africanism. Issues to be addressed at this conference and as part of the project to transform CPUT should include:

A review of the present language policy to promote African languages. Language plays a crucial role in shaping national culture, identity and history.

The establishment of a new curriculum with content centred on people’s education for people’s power. The aim should be to offer an African-centred and -relevant education.

A review of efforts to foster greater inclusion for disadvantaged groups at the institution and to ensure the production and promotion of black, conscious graduates. The current ageing reactionary generation of academics must be replaced.

Serious consideration of the students’ calls for free education. Education enables social justice and economic empowerment. If the system perpetuates the idea that only those with money can access higher education, while those who are poor are excluded, then it remains fundamentally untransformed.

A comprehensive survey of all colonial symbols and names at university with a view to eradicating them.

Mr Nanga Codana

SRC President

2

As President of the Student Representative Council at the University of Fort Hare, Robert Sobukwe explained the fundamental value of higher education. He said that it entailed identifying with the masses and producing graduates who could be of service to the nation, the continent and all mankind. In talking of transformation, we must be reminded of such African aspirations and how they can only be fulfilled through the implementation of radical policies that speak to the decolonisation of the mind. Both Chinua Achebe in Things Fall Apart and Steve Biko in I Write What I Like expounded the view that the meaningful total liberation of African people can only be achieved by decolonising the mind. In this context, there is a need to revive the black consciousness movement and promulgate knowledge of African history and culture in order to produce a brighter future. Meanwhile, at the institutional level, decisive leadership is required to dismantle epistemic violence, apartheid culture and western traditions; and to provide a strategic vision and plan for decolonisation in pursuit of black excellence and the university’s Africanisation.

Why do higher education institutions struggle so much to institute transformation in substantive fashion despite having transformation offices and frameworks? Is it a matter of consciousness?

In part the problem arises from the belief that documents, including transformation pledges, should structure our thinking. But documents don’t structure our thinking, they may provide a vision and they certainly offer an account of what a university intends to do and the path that it may seek to follow. Beyond this, policies and documents must be workshopped and discussed – and not just by a few people in a room – so that the underlying issues and challenges may emerge.

The problem also arises in part from widespread cynicism in society. The previously enslaved and oppressed communities have undergone so many changes with so few benefits to themselves that they have come to be wary of change, often seeing it as something that must be suffered. There is also a widely held belief in South Africa that is no need to change – that we are already conscious individuals and should not be called into question or that prejudice is an inevitable outcome of the country’s history.

However, another view is that change may be understood as offering an opportunity for growth – and that, in fact, we should be actively seeking to produce change in order to foster genuine transformation. Under this view, change doesn’t happen because somebody else does something, change starts with us. In this context, one of the reasons that it seems to be difficult to implement transformation is because this work entails recognising that in order to grow, we need to undertake self-examination and self-interrogation. We can’t just say: “I have a gay friend, so I can’t be homophobic”; or “I have won an award for teaching, so I do not need to listen to student concerns about working with me”. A crucial aspect of implementing transformation is to remember that the purpose is to produce a better future, which depends on creating better people. And a better person is necessarily someone who recognises that they have growth to do.

One of the reasons that it seems to be difficult to implement transformation is because this work entails recognising that in order to grow, we need to undertake self-examination and self-interrogation. We can’t just say: “I have a gay friend, so I can’t be homophobic”; or “I have won an award for teaching, so I do not need to listen to student concerns about working with me”.

How can we open up the difficult conversations that are required to institute genuine transformation within the university space?

As a society, we may need capacity building in how to listen critically to the views and opinions of others without taking offence or feeling threatened or becoming defensive. Such unpacking and understanding are fundamental to the implementation of democracy. Consciousness requires that uncomfortable conversations take place and entails an acceptance that disagreements will happen. There is a saying: “If you can’t fight your parents, you can’t go into the world.” This is something that I learnt myself, struggling with my mother, insisting that it was OK for me to join protest marches, that I didn’t need to be monitored all the time.

At the same time there is a core responsibility to the collective. For example, we are bound to programmes of action by our understanding that we belong. Within the community of educators and scholars, part of that belonging entails asking critical questions and recognising that we may be wrong; that we still have learning to do; that we don’t all come to the table fully formed. In this regard, it is important to acknowledge that it can sometimes be the difficult moments that produce personal growth and that such moments may keep coming. It is not an easy path and it requires commitment to walk it.

How can a university of technology find the time and space in its curricula to incorporate indigenous knowledge for the benefit of transformation, decolonisation and selfconsciousness when its main aim is to produce graduates who can follow instruction in the workplace?

There is time and place for everything. Part of the challenge is not to teach indigenous knowledge as something that is foreign, strange or unusual. Indigenous knowledge is on CPUT’s doorstep. Cape Point, Robben Island and District Six are key historical sites in the area. The Kaaps language which was developed by slaves from Java, Indonesia and Bengal is still spoken by many communities on the Cape. But there has to be a proper process and commitment to engaging with such knowledge. Members of the indigenous communities have to be invited to share their knowledge and the students and staff need to go into these communities with respect. The process must be top-down and bottom-up in order to engage with the indigenous culture on its own terms and partake of forms of knowledge which have been repressed.

In addition, there must be a creative

understanding of the benefits of the incorporation of indigenous knowledge into traditional fields of study, such as psychoanalysis. Rather than considering psychoanalysis in the European context as a field invented by Sigmund Freud through which the relationship between the conscious and the unconscious may be studied, I see it in an African context – as a way of interpreting and understanding different moments in the history of the continent. Thus, it may find as its subject matter Joseph’s interpretation of the dreams of Pharoah; the chanting, art and apothecary of the Khoi and San hunter-gatherers as an expression of their relationship with the earth; or the dream culture of historical and contemporary black and coloured communities. Such an approach to the study of psychoanalysis can offer important perspectives on ways of seeing and being in the world which would otherwise perhaps be lost.

A key question for CPUT in considering its trajectory for transformation is how best to create a better future for the institution and the country. A clearer understanding of the work of African political thinkers and untold stories of the past can indicate the path that needs to be taken and also foster hope that a country still riven by trauma as a result of its past may be healed.

Prof Driekie Hay-Swemmer

Executive Director Office of the Vice-Chancellor

In part the problem arises from the belief that documents, including transformation pledges, should structure our thinking. But documents don’t structure our thinking, they may provide a vision and they certainly offer an account of what a university intends to do and the path that it may seek to follow. Beyond this, policies and documents must be workshopped and discussed – and not just by a few people in a room – so that the underlying issues and challenges may emerge.

The problem also arises in part from widespread cynicism in society. The previously enslaved and oppressed communities have undergone so many changes with so few benefits to themselves that they have come to be wary of change, often seeing it as something that must be suffered. There is also a widely held belief in South Africa that is no need to change – that we are already conscious individuals and should not be called into question or that prejudice is an inevitable outcome of the country’s history.

However, another view is that change may be understood as offering an opportunity for growth – and that, in fact, we should be actively seeking to produce change in order to foster genuine transformation. Under this view, change doesn’t happen because somebody else does something, change starts with us. In this context, one of the reasons that it seems to be difficult to implement transformation is because this work entails recognising that in order to grow, we need to undertake self-examination and selfinterrogation. We can’t just say: “I have a gay friend, so I can’t be homophobic”; or “I have won an award for teaching, so I do not need to listen to student concerns about working with me”. A crucial aspect of implementing transformation is to remember that the purpose is to produce a better future, which depends on creating better people. And a better person is necessarily someone who recognises that they have growth to do.

+27 (0)21 959 6767 info@cput.ac.za

www.facebook.com/cput.ac.za @cput @wearecput www.cput.ac.za