Kiaora, and welcome to the June Edi on of Supplyline. We are half way through the year already, and coun ng down to our 50th Anniversary Conference in September and beyond that to Christmas 2024. The year is just passing by.

We have a huge amount of informa on in this edi on. Ar cles, adverts and updates rela ng to on-going projects that the Execu ve Body is involved in. More importantly, in this issue of Supplyline is the informa on around vo ng for the NZSSA President and Execu ve member’s roles for the next term. Paul Moody our Secretary, has done a lot of work around this. The vo ng will be available on-line for NZSSA Members so please read the informa on carefully.

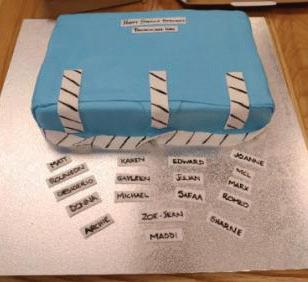

Donna Dador from Southern Cross Hospital has shared some photos of her staff celebra ng World Sterilisa on Day. The cake made to look like a wrapped set is amazing. Very crea ve and in keeping with what we do. Thank you for Donna and her team for sharing these photos.

If there are any other units that have celebratory occasions and would like to share photos and informa on, please send it through to me and I’ll include it into Supplyline. Would love to see what other areas are doing and celebra ng.

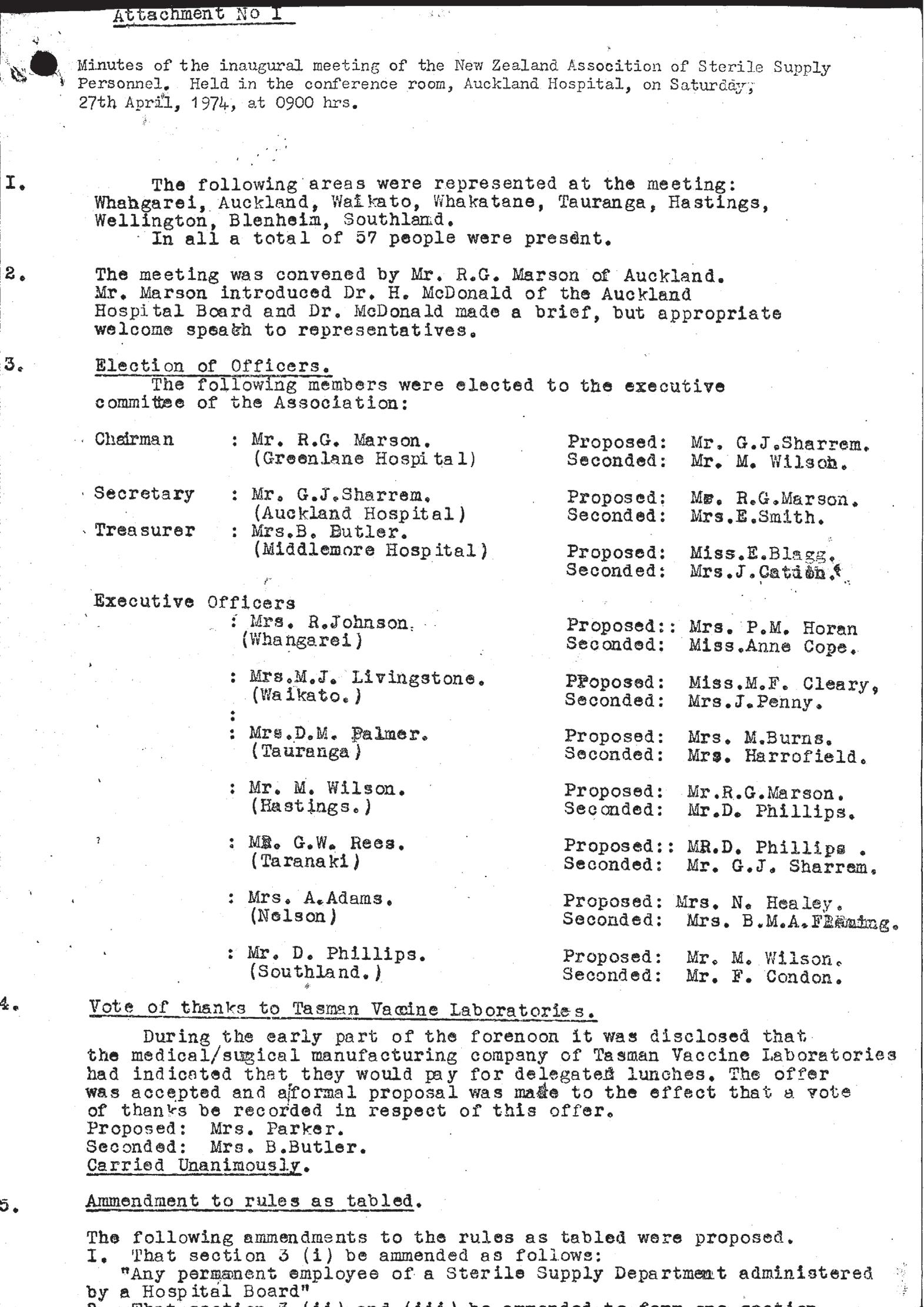

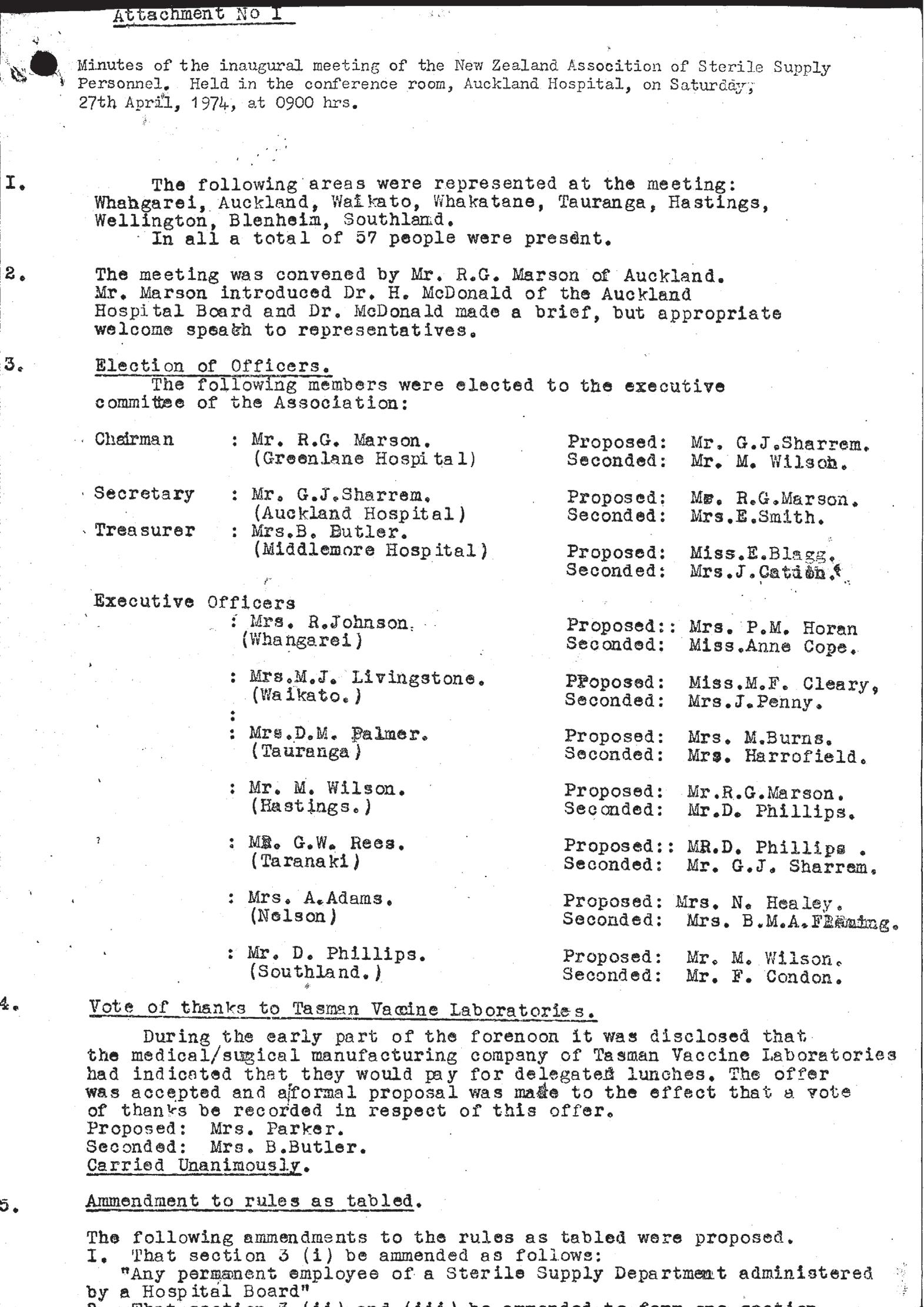

As I men oned above, it is our 50th Anniversary this year. Such a huge achievement, we should be extremely proud of this. We have come a long way in this profession from being thought of as ‘glorified cleaners’, to being the professional body for reprocessing RMDs. Our 50th Anniversary conference in September is an opportunity to acknowledge and celebrate how far we have come.

Take care and hope to see many of you at the NZSSA Conference in September.

Ngā mihi

Aileen Derby Editor NZSSA Supplyline

Welcome to the winter edi on of your journalSupplyline.

This edi on is our largest yet, therefore lots for you to read.

I am excited, who else is excited to celebrate 50 years of the NZSSA. Not many professions can claim they have been around that long. When I started in theatre many moons ago CSSD staff were effec vely the “dishwashers or cleaners” No one was expected to have knowledge and qualifica ons and did what they were told without knowing why. Even myself as a theatre nurse never really knew what CSSD was about un l I took over the manager role. Look at you all now. You are educated professionals, you have a voice and can make decisions on what is best prac ce. The profession and each of you have come a long way.

This year we are celebra ng those 50 years in style in Auckland. Are trades are all coming on board to join us and we would love you the technicians to make this the best conference ever.

As you may all be aware this is the year that you the members have the opportunity to vote for your execu ve

to lead the profession through the next three years. All details of nominees and how and when to vote are in this edi on. I am very pleased to see that we have some new members who are willing to step up and join the execu ve as well as some exis ng members of the team.

In order to vote you will need your membership number which is available to you on line on the NZSSA website. Please make sure that your email address is current in order for vo ng informa on to be sent to you.

The NZSSA is s ll receiving applica ons for equivalency cer fica on from overseas applicants as well as from those overseas origina ng technicians who are working in New Zealand and are seeking equivalency in order to obtain a residency visa. We expect that there will be a lull in the process while Health NZ/Te Whatu Ora are taking longer to approve vacancies.

On that note it is important to state that Sterile Technicians may be Allied Health professionals, however we remain as clinical front line staff. This was affirmed to be by the NZ nursing council when I had to submit my senior nurse por olio to them a year ago. I asked the ques on “as a qualified sterile technician and a registered nurse am I considered clinical”?

The response from the NZNC was that my CSSD role

was clinical and that through the reprocessing of surgical instruments I was providing indirect clinical care to the pa ents. Therefore remember if anyone tries to tell you otherwise, correct them, as without CSSD staff in the periopera ve clinical arena there will be no surgeries occurring.

Aileen Derby and I recently a ended a workshop presented by Pharmac. They had leaders from relevant professions a ending to discuss reusable medical devices including instruments, sterilisers, washers etc. Going forward they will seek our input on new devices that companies wish to register and hospitals may wish to use. They are being very proac ve. Unfortunately it appears from that mee ng that a TGA equivalent for NZ is s ll a way off

Aileen and I also a ended one of the regular scheduled mee ngs with the Ministry of Health for self-regula ng professions. These are chaired by The Chief Allied Professions Officer for NZ Dr Mar n Chadwick and Lauren Hancock, Senior Advisor to the CAPO. At this mee ng we had a presenta on rela ng to the HPCA and poten al changes that could occur. They are looking at regulated and self- regulated professions and it could mean we become regulated or they will introduce new categories of regula on. The work is only in the early stages but it looks promising.

Take care of yourselves

Shelagh Thomas President/NZSSA

We care for each other, showing kindness and empathy in all that we do.

We are commi ed to fi nding future focused solu ons and take personal responsibility to be be er every day.

Our diversity is our strength, we back each other and work together in partnership.

We are commi ed to doing the right thing by ensuring equity and hauora are at the heart of everything we do.

The current execu ve term is due to end in September of this year, and we have a host of new candidates looking to join the Na onal Execu ve and take on the role of President. Our cons tu on defines the execu ve as comprising ten members: the President, the Secretary and eight other members and they serve for a period of three years so please take the me to read the biographies below and learn a li le about each volunteer before exercising your vo ng rights!

This year vo ng papers will be sent out via an email link and will also be available through the associa on website (www.nzssa.org). You have two weeks to complete the vo ng form (but don’t wait, make an informed decision now) and will need to supply your name, email address and associa on membership number to ensure your vote is valid.

You will be asked to vote on two independent categories:

Category 1 – Associa on President

There are three candidates running for the role of

President. You have ONE vote for this category. Place your vote alongside the name of the candidate you believe will best serve the associa on over the next three years.

Category 2 – Members of the Execu ve

There are ten candidates wan ng to join the next execu ve team. You have NINE votes for this category. Place a vote alongside the names of up to nine candidates you believe will best serve the associa on over the next three years. You do not have to use all nine votes.

Note that votes in category one have no bearing on outcomes in category two and vice versa. If you want a candidate to be President but also think they should be an execu ve member then you need to vote for them in both categories.

To help with your decision each candidate has supplied a short statement as to why they wish to serve on the Na onal Execu ve. These are presented below in alphabe cal order on a first name basis.

Choose one of the following three candidates.

I have worked in the sterilising field for over 40 years now star ng as a CSSD Assistant in a small public hospital in Te Kui . During the 40 years I have had a variety of roles, including Technician, Deputy Manager, Educator and Manager.

Currently I am the Manager of the CSSD at Coun es Manukau District in Auckland. There are two CSSD’s in Coun es Manukau District, one at Middlemore Hospital and one at Manukau Health Park (MHP). We are currently part of a project where four more theatres are being built at MHP, as well as a new PACU and a new CSSD.

I have had the privilege of having been on the NZSSA Execu ve body previous to my current tenure, and served as both Secretary and President. I then had a break before being nominated as an Execu ve Member in our last elec on process.

For the last 2 ½ years I have served on the NZSSA Execu ve Body as the Vice President. I’ve been involved in a number of interes ng projects including being the Editor of Supplyline, se ng up a complaints process, self-regula on and looking at competencies for sterilising personnel to name a few. This year I’m on the Conference commi ee for what will be an exci ng occasion – our 50th Anniversary conference.

The world of sterilising prac ces and standards has come a long way and it’s been a honour to have been part of that. I’m looking forward to seeing what comes next, both in my own workplace and with the NZSSA.

Thank you

Hello to everyone reading this. I have wri en a li le bit about my vision for moving the NZSSA forward and why I think I would make a good NZSSA President.

My vision for the NZSSA moving forward

Currently the NZSSA is moving forward in the right direc on with the self regula on process, I would like to see this con nue and the NZSSA become the regulatory body for all reprocessing of reusable medical devices ac vi es throughout New Zealand. I would also like to strengthen our rela onship with government departments to help our industry get more recogni on for the work that we do, which in turn may help with pay parity discussions in the future. I belive it is important that the rest of the healthcare industry understands and respects our contribu on to the pa ent journey and understands how important our role and industry is.

The NZSSA has been established for 50 years and in that me it has grown to become what it is today, the NZSSA has moved the direc on of this industry forward since its establishment and I want to do my part to help it con nue to move forward.

I have been in this industry for 15 years now and I am here to stay, I am here to help grow the industry, I am here to help it gain the respect it deserves, I am here to ensure the pai ents receive the best possible care that we can provide.

My name is Mar n Bird. I am the manager of Sterile Science Department at Dunedin Hospital, and I have been an execu ve member for 4 terms, and with nearly 30 years prac ce experience behind me I have networked extensively throughout New Zealand and Australia which has enabled me to accumulate great resources, mentors and specialist knowledge.

I am confident that I have the leadership skills, qualifica ons, experience and commitment that the role of President of the New Zealand Sterile Science Associa on requires, and I believe that this is the next progressive step within the Sterile Sciences industry.

Thank you for considering me for the Sterile Science Execu ve.

Choose up to nine of the following ten candidates to form the remainder of the Execu ve commi ee.

I have worked in the sterilising field for over 40 years now star ng as a CSSD Assistant in a small public hospital in Te Kui . During the 40 years I have had a variety of roles, including Technician, Deputy Manager, Educator and Manager.

Currently I am the Manager of the CSSD at Coun es Manukau District in Auckland. There are two CSSD’s in Coun es Manukau District, one at Middlemore Hospital and one at Manukau Health Park (MHP). We are currently part of a project where four more theatres are being built at MHP, as well as a new PACU and a new CSSD.

I have had the privilege of having been on the NZSSA Execu ve body previous to my current tenure, and served as both Secretary and President. I then had a break before being nominated as an Execu ve Member in our last elec on process.

For the last 2 ½ years I have served on the NZSSA Execu ve Body as the Vice President. I’ve been involved in a number of interes ng projects including being the Editor of Supplyline, se ng up a complaints process, self-regula on and looking at competencies for sterilising personnel to name a few. This year I’m on the Conference commi ee for what will be an exci ng occasion – our 50th Anniversary conference.

The world of sterilising prac ces and standards has come a long way and it’s been a honour to have been part of that. I’m looking forward to seeing what comes next, both in my own workplace and with the NZSSA.

Thank you

Kia Ora, my name is Antony Owens, and I have been involved in the Sterilisa on Sciences field since January 2002. I have a keen interest in educa on and following comple on of my Degree in Management in 2004, I a ained the Cer ficate in Sterilisa on Technology in 2006, and completed the Diploma in Sterilisa on Technology in 2022.

I have been the Sterilisa on Department Team Lead at Southern Cross Gillies Hospital since 2015, and fully enjoy the challenges the role encompasses and the interdepartmental rela onships it provides, especially with the Theatre Services Manager and wider Hospital Team.

I am passionate about Sterilisa on, its importance in the pa ent’s journey, the work we do, and the con nual professional development for those who work in the area each day. My passion is quality management within sterilisa on, and ensuring the educa onal pathway provides opportuni es and challenges to encourage people to choose sterilisa on as a career, whilst ensuring those who work in sterilisa on have a visible pathway to progress.

Outside of sterilisa on I have been Chairman of a Football Club in Auckland for the past several years and hold a number of OFC/NZF coaching qualifica ons. Being involved in the running of a football club, and many hundred members, always presents a challenge but it is a fantas c way to contribute to my community. I am also very pa ently learning the Samoan language, thanks to my very pa ent partner!

I am currently employed as SSD Coordinator and Health & Safety Coordinator at Evolu on Healthcare Royston Hospital in the lovely Hawkes Bay. I have obtained the NZ Level 4 Cer ficate in Sterilising Technology through Toi Ohomai in 2021 and am currently studying towards obtaining my NZ Level 5 Diploma in Sterilising Technology. I hold a degree in Social Sciences, and a post-graduate (Honores) degree in Criminology, have a cer ficate as Ambulance A endant and am a qualified Enrolled Nurse.

My main objec ve in the working environment is to con nually be er myself and grow, gaining knowledge through experience in a wide variety of fields, to enjoy what I do and use all my skills and talents. I have a passion for health & safety, problem solving, audi ng, processes, learning and training people.

Personally, I am friendly, love animals, socialising, fundraising for chari es and watching rugby. I value respect, integrity, honesty, empathy, kindness and fairness.

I would appreciate the opportunity to serve as Execu ve Member for the NZSSA - to learn and specialise in the profession, contribute to the growth of the profession and the wellbeing of members, advoca ng for them and informing them.

Thank you for the opportunity.

I am Charanjeet Kaur Sidhu and I am currently working as a Quality Facilitator for CSSD, Health New Zealand Coun es Manukau, covering two sites, Middlemore Hospital CSSD and Manukau Health Park CSSD. I have about 15 years of experience working in CSSD.

I started as a CSSD technician at Auckland City Hospital, and have held roles of Ac ng Shi Co-ordinator, CSSD Supervisor, Ac ng CSSD Manager, and now CSSD Quality Facilitator. I have grown step by step in my career by learning through courses and by experience.

Being in a quality role, I go through the standards and take quality implementa on and quality improvement ini a ves for the unit.

NZSSA is a sterile sciences organisa on for the whole country. Being on the execu ve commi ee, I would be able to share my knowledge around the standards and the challenges with the quality improvement ini a ves. It would also give me an insight how NZSSA works, understand the changes happening in sterile sciences and think big for the country as a whole.

Life is too short to be anything but happy, the more you enjoy and love your work ,you become a be er version of yourself. A lot of great outcomes are by-product of loving what we do.

Hi, I’m Donna, A highly mo vated SSD Manager with change maker mindset and passion for quality improvement ini a ves.

A Nurse by heart and an SSD technician by choice. I have come to terms that although I am not working beside a pa ent assis ng them personally, I am s ll taking part in their journey to recovery by providing safe, sterile, and quality instruments for their surgery.

I wish to join the NZSSA to be able to connect to more people and further my professional development. To be able to learn informa on, share and promote educa on to my fellow SSD professionals.

I have a bachelor’s degree in nursing, holder of level 7 Health Services Management diploma, Completed Level 5 steriliza on cer ficate and am currently enrolled for the Diploma in Sterilizing technology Level 5. I genuinely believe that educa on is the key to achieving a safe and quality service for every pa ent.

My skills include a proac ve approach to change and quality improvements, sensible and resilient, able to blend in and adapt to diverse cultures and environment as evidence by previous employments in other countries such as Philippines and Singapore.

Kia Ora

Hello, my name is Jenny Carston and I work in the Periopera ve department of our hospital as the team leader for the CSSD department, Hauora a Toi Bay of Plenty. Although I am based on the Tauranga site, I provide professional advice and support for the team on the Whakatane site. I have been on the Execu ve Commi ee for the last I think 17 years and have been in the sterilising field for 27 years. I enjoy what I do and have no ced that over the last few years, we are finally ge ng a voice, especially through Pay Equity and now a lot of the hospitals realize that without us they cannot perform their cases in theatre and as I remember back when I first started 27 years ago and a ending a wage nego a on HR saying anyone can do our job we are just cleaners. I would like to see that person now and ask him does he s ll feels the same a er all these years.

We are finally ge ng the voice we need and with everyone behind NZSSA with more members obtaining registra on, I see greater recogni on of our specialty and a be er understanding of the importance of our role.

I am the Manager for the Sterile Sciences Unit- Acute & Elec ve Surgical Services, here at Palmerston North Hospital. I started working in the SSU back in 2004.I wanted a change, and a trainee technician role came available. I found the work interes ng and rewarding and it quickly changed from “a job” to something I could see becoming a career.

I became the Manager 3 days before the Covid lockdown back in 2020. Naviga ng a new posi on in an unknown and changing health environment wasn’t without its challenges, but with help from a great and suppor ve team – here I am- s ll here four years later. With the support from the NZSSA, our Sterile Science Technicians are now recognised as professionals within the Surgical Services family. I would like to see the encouragement of con nued educa on so Technicians can con nue to build the important profile we deserve within healthcare.

Outside of work, when I am not being a taxi to my 5 children, I work for MPI as a Fishery Officer, conduc ng recrea on fishery compliance inspec ons.

Thank you for considering my nomina on for a posi on on the execu ve commi ee of the New Zealand Sterile Sciences Associa on (NZSSA). I am honored to have the opportunity to con nue serving in this capacity.

As a current execu ve member, I have found great sa sfac on in my role, par cularly in assessing registra on applica ons. This responsibility allows me to gain insight into the ongoing educa on efforts of sterilising staff across New Zealand. Addi onally, I am privileged to witness the exemplary work of talented technicians, which underscores the dedica on of our profession within the healthcare sector.

With over 30 years of experience in Sterile Services, encompassing both public and private sectors, I bring a wealth of prac cal knowledge to the table. My journey has seen me serve as a sterilising technician and, currently, as the manager of the sterilising facility at the University of Otago Faculty of Den stry.

This role has been fascina ng and fulfilling, as it has afforded me the opportunity to bridge the gap between den stry and reprocessing standards, ensuring alignment with both office-based and hospital standards.

In conclusion, I am driven by a passion for advancing the field of sterile services and empowering others to deliver the highest quality of care. I am eager to collaborate with fellow commi ee members to address challenges, share best prac ces, and elevate the standards of our profession. Thank you for considering my candidacy, and I look forward to the opportunity to contribute to the NZSSA’s mission.

Ngã mihi Kelly Swale

My name is Mar n Bird. I am the manager of Sterile Science Department at Dunedin Hospital, and I have been an execu ve member for 4 terms, and with nearly 30 years prac ce experience behind me I have networked extensively throughout New Zealand and Australia which has enabled me to accumulate great resources, mentors and specialist knowledge.

I am confident that I have the leadership skills, qualifica ons, experience and commitment that the role of Execu ve of the New Zealand Sterile Science Associa on requires, and I believe that this is the next progressive step within the Sterile Sciences industry.

Thank you for considering me for the Sterile Science Execu ve.

Nga mihi, Mar n Bird

I am seeking to be re-elected to the execu ve team of the NZSSA.

Why? The answer is PASSION

I am passionate about our profession and ensuring that it con nues to grow and develop and move forward into the future.

I am passionate about educa on for sterile technicians and for them to be recognised for their hard work both professionally and financially.

I am passionate about every hospital in New Zealand achieving and maintaining levels of excellence in sterilising technology and adhering to the standards without compromise.

I am keen to carry on working on projects that I am involved with for the associa on and see them come to frui on e.g. the scope of prac ce and competencies document for sterile technicians.

In my tenure on the execu ve to date we have achieved a lot including:

• Close links with the Ministry of Health

• Recogni on as a self-regulated profession

• Involvement in Pay-equity process

• Sterile Technicians added to the immigra on green list

• Introduc on of level 5 Diploma of Sterilising Technology

I have 17 years’ experience working as an SSD manager and my experience in that role has given me skills which I can use as an execu ve team member.

I have been the president of the NZSSA since I was thrust into the role in 2012. It is now me for someone else to take the lead and I am happy to work in the background offering support to whoever takes my place as president.

Please vote for me to be an execu ve team member.

Thank you

Steriking Reinforced Rolls and Roll Holder

Original Article

Brian Kirk

Corresponding author: Dr Brian Kirk

Brian Kirk Sterilization Consultancy Group Ltd 10 Harcourt Place Castle Donington Derby DE74 2XJ U.K.

Bkirk0256@outlook.com

Conflict of interest:

The author is an independent researcher and director of Brian Kirk Sterilization Consultancy Group Ltd. Prior to establishing his company he worked for 3M Health Care. This study was carried out by Brian Kirk Sterilization Consultancy Group Ltd and funded by a research grant provided by 3M St Paul, USA.

Citation: Kirk B. Detecting vaporised hydrogen peroxide sterilization (VH2O2) process failures in clinical settings using chemical indicators. Zentr Steril 2020; 28 (6): 334–343

Manuscript data:

Submitted: 8 September 2020

Revised version accepted: 10 November 2020

Summary

Background: VH2O2 sterilizers are used to process heat sensitive medical devices. Chemical Indicators (CIs) are often used to monitor such processes.

Aim: Determine the ability of VH2O2 CIs to indicate when sterilizers were operated according to recommendations (pass) and when operated with unsuitable loads or processing cycles (fails).

Method: Studies were conducted in sterile processing departments (SPD) in -

tance colourimetry were used to assess CI colour change when placed inside loads which were within or exceeded the weight limit for a STERRAD® NX100 EXPRESS process (SPD1) and then a different load in EXPRESS or STANDARD NX100 processes (SPD2). Findings: Shinva®, gke® and Terragene® CIs gave slight differences in colour change in different test conditions. The Shinva and Terragene CIs were interpreted as passes. The gKe CI gave an aquamarine colour which could have been interpreted as Pass (chosen) or Fail. Differences in col-

observed in the three indicators, some

Steris-Celerity®, Steris-Verify®, 3MTrimetric® and SPS® CIs differentiated recommended from not recommended loads and processes giving visual pass or fail results and differences in E but with differing levels of accuracy and precision. The ASP® CI gave similar observable and measurable differences but all were passes when compared to the reference colour.

The Steris-Celerity and Steris-Verify CIs showed observable and measur-ferent positions inside one pack but not the others. The Trimetric and SPS CIs showed observable and measurable positions in all packs.

The ASP CI showed similar differentia-

The 3M-Trimetric had the greatest accuracy and precision indices.

Conclusion: CIs help provide an assurance of sterility for VH2O2 sterilization processes. New loads or processes introduced into an SPD should be subject to help identify non-uniform conditions within packs. Routine monitorof incorrect loads or processes and can help detect process failures in clinical settings.

Introduction

Sterile medical devices, either single use or re-usable, must be sterilized by a validated sterilization process [1,2]. High temperature steam is used for re-usable metal surgical instruments.

Keywords

EN ISO 11140-1

Type 1 and 4 chemical indicators

VH2O2 sterilization

Sterilization routine monitoring

Sterilization performance qualification

Detecting process failures

Low temperature processes employing ethylene oxide gas, low temperature steam with formaldehyde vapour and more recently vaporised hydrogen peroxide (VH2O2) are used for medical devices made of heat sensitive materials [3]. International standards describe validation and routine control for some sterilization processes [4,5 and 6]

VH2O2 processes; these are in development [7]. In the absence of a specific process standard, EN ISO 14937 applies [8]. However, VH2O2 is now one of the most popular processes employed in health care facilities.

ed on a substrate, which respond to de-

Table 1: A list of CIs tested in the study.

ProductType

A – ASP® STERRAD® Chemical Indicator Strip (14100)

Stated Values (SV) VH2O2 conc (mg/l) / T (°C) / t (s)

12.3 / 50 / 360 Dark Red to Orange /Yellow Orange printed on CI

B – Shinva® vH2O2 label (010104) 1a N/ARed to Yellow Six reference colours from Red to Yellow in IfU

C – Steris® Celerity® HP Chemical Indicator (PCC074)

D – Steris® Verify® HPU Chemical Indicator (PCC061)

E - 3M® Attest®

VH2O2 Tri-Metric® Indicator (1348)

F – gke® Steri-Record® CI for VH2O2 (C-V-P-6)

G – SPS Medica®l

VH2O2 Indicator Strip (GPS-250R)

12.3 / 50 / 360 b Red to Orange/ Yellow Orange printed on CI

12.3 / 50 / 360 Magenta to Yellow Yellow printed on CI

45.1 / 50 / 60Blue to PinkNone

42.3 / 50 / 360 Light Blue to Light Green blue to light green in IfU

42.3 / 50 / 360Dark Pink to Bluenone

H – Terragene® Chemdye® VH2O2 CI (CD40) c 42.3 / 50 / 360 Purple to dark green / blue to greenc

Green printed on CI. Five ref colours from purple to light green in IfU (not the same green)

Interpretation instructions

“Bar changes from red to colour indicated by comparator bar [orange] or lighter” printed on CI.

Orange or lighter (towards yellow) is a Pass (ref chart)

An arrow pointing from the indicator strip to the reference colour printed on the indicator. “If the indicator colour matches the orange reference colour or is lighter…” in the IfU.

“Accept only if magenta circle turns yellow” printed on CI

“Any pink in accept zone is a pass” printed on the CI

Blue to green. “If the indicator dot remains purple/blue or has not turned to the final colour completely” in IfU.

“Indicator turns BLUE when exposed to VH2O2 during the sterilization process” printed on CI

“The indicator must turn to the reference colour for considering that the indicated conditions were met” in IfU.

A list of CIs tested in the study including their stated values, specified colour change, presence or absence of a colour reference on the CI or in the Instructions for Use (IfU) and a description of the manner in which the colour change should be interpreted as printed on the CI or contained in the IfU.

a: The Shinva packaging and accompanying technical sheets did not specify which type therefore it was assumed that because it was an adhesive label for attachment to the outside of packs it would be a process indicator of type 1.

b; The Celerity indicator is claimed to be a type 1 which according to EN ISO 11140-1 has defined SVs as shown.

c The Terragene Chemdye tested were provided in a foil pouch and had a purple starting colour (see 15),

® Acknowledges registered trade marks

The requirements for six types of CIs

Type 1, process indicators, usually placed on the outside of a pack to indicate that it has been processed. Type 2 for special tests. Type 3 are single variable indicators having limited utility. Type 4, 5 and 6 are multi-variable, integrating and emulating indicators, having different performance requirements according to EN ISO 11140-1 and are related to manufacturer’s claims. This latter group are used as internal indicators, placed inside individual load items to assess attainment of sterilizing conditions at the point of placement. Some guidance recommends the routine use of such indicators [11,12] and the WHO surgical safety check list [13] mentions their use as part ofthe informaof every pack” before use.

Unlike steam sterilization, which provides a high overkill, and wide utility, VH2O2 processes are designed for loads. It is vital that manufacturers recommendations are carefully followed. However, in a busy sterile processing department it is possible to inadvertently process a device or load in a sterilization cycle which is not recommended by the manufacturer. It is also possible to use inappropriate accessory items and sterile barrier systems which can, individually or in combination compromise process ef-strument sets can potentially detect process failures when used routinely or when conducting performance qualis compatible with the intended sterilization cycle.

An earlier study [15] characterised eight CIs for VH2O2 sterilization processes to give a pass or fail result when tested according to the methods in EN ISO 11140-1 and also to detect changes in the individual process variables time, temperature and VH2O2 concentration. In this study the same cohort of CIs were used in clinical settings to characterise their performance when sterilizers were operated according to recommendations or when operated with unsuitable loads or sterilization processes. In addition, the ability to

Zentralsterilization | Volume 28 | 6/2020

detect differences in processing conditions inside individual packs was also evaluated.

Methods

Chemical Indicators.

CIs, purchased from commercial sources, are shown in Table 1 along withour change characteristics, colour of any reference present and a summary of the instructions for interpretation. All CIs were stored in their original packaging equilibrated to ambient conditions before use (ca. 20 to 25 °C and 30 to 50% rh).

Products A to D and F to H had indicator ink printed on a substrate. Product E had indicator ink printed on a substrate covered with a polymer sheet with gaps cut along its length. Beyond the “accept line” the overlying sheet enclosed the ink creating a small gap through which VH2O2 penetrated to effect colour change.

Evaluation of CI colour change.

The methods described previously [15] were used to evaluate colour change.

eter (X-Rite eXact Standard spectrophotometer,https://www.xrite.com/categories/portable-spectrophotometers/ exact ) with an aperture of 1.5mm and white light illumination and expressed as International Commission on Illumination, (CIE) L*,a*,b* coordinates [16].

The variable E, which is a measure of the visible appearance of a colour, was then calculated for each CI sampleferences (p=<0.05) between values of E for sample groups of CI products exposed to different conditions was then determined using ANOVA and t-test calculations (the values of E from different products not being directly comparable). The values of E were then plotted

Colourchange was also judged by visual observation in bright daylight by a west facing window and categorised as pass or fail according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and, if provided, by comparison with a colour reference. From these observations two values were calculated [17]. Accuracy, representing a measure of whether the CI reported a correct result whether pass or fail and precision, the proportion of

true passes as a percentage of the total of true passes plus false passes (maximum=1).

The variability of the measurementstometer were found to have a standard deviation of <0.1 units of L*, a* and b*.

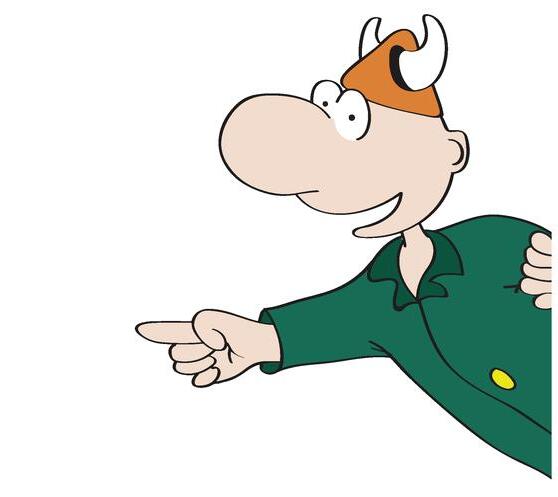

Test Conditions Employed in Clinical Settings

Tests were carried out in ASP® STERRAD® NX100® VH2O2sterilizers (https://www.asp.com/product/terminal-sterilization/STERRAD-100nx) operating either EXPRESS (4.85 kg /10.7lb maximum loading weight) or STANDARD (9.7kg/21.4lb) cycles at two different sterilization processing departments in hospitals in the USA. During exposure the VH2O2 concentration was measured using an on-board UV spectrophotometer and then reported as an integrated variable, area under the curve (AuC or dose) with dimensions mg.s/L.

Three standard loads were employed in department 1 (Xi, DV1, DV2) each exposed to an EXPRESS cycle. A fourth load was used in department 2 exposed to either an EXPRESS (StE) or STANDARD (StS) process as follows;

Xi – DaVinci Xi Endoscope set with mounting tray and lid (Intuitive Surgical Inc, USA https://www.intuitive.com/en-us/products-and-services/da-vinci), double wrapped in a non-woven polypropylene sterilization wrap secured with a 15 cm length of VH2O2 indicator tape (3M

1A)

DV1 – A DaVinci Si probe mounted on pillars within an Aescuand 2 bottom) container, weighing

DV2 – As for DV1 but with two DaVinciSiprobes,weighing

StE or StS – A Stryker camera system (Stryker 1588 AIM Pendulum Camera Head with Integrated Coupler) in an Aesculap rigid half DIN

1D) (three replicate sets) weighing 5kg/11lb exposed to either an EXPRESS or STANDARD process

The instructions for the STERRAD sterilizer recommend maximum loading weights for the EXPRESS and STAND-

ARD cycles. Based on this information and the information in the instructions for the medical devices tested the loads processed in test condition Xi and StS are recommended whereas those processed in test conditions DV1 and DV2 (excess weight) and StE (inadequate exposure time) are not recommended. One might expect CIs to provide a pass indication in the Xi and StS and a fail in DV1, DV2 and StE.

Triplicate samples of each CI were included in each

were conditioned for 45–60 minutes to ambient conditions (ca. 24 °C, 30%rh) between uses. Test loads were placed on the lower shelf in the sterilizer (random orientation unre-

ther EXPRESS or STANDARD processes as described above. Immediately after processing the cycle record was recovered and relevant data noted, the load temperature measured and the CI samples recovered, placed between tissue paper and secured in sealable polythene bags. Colour measurements of CIs were made within 3 days of exposure.

Results

Table 2 shows the test conditions employed and the VH2O2 AuCs reported by the sterilizer. The average AuC when using test condition Xi in the EXPRESS cycle in department 1 was

when using test condition StE and StS in the EXPRESS and STANDARD cycles in department 2 were statistically differ-

ible interpretation, as a fraction of the total number of CIs used in the respective test condition and the accuracy and precision of all observations.

Table 3 shows examples of each of the indicators colour change when exposed to the conditions described in table 2.

Figure 1 shows the location and notation of each group of CIs within load Xi, DV1, DV2 and StE/StS. Figure 2 shows the value of E for combined data sets (left+middle+right and edge+centre) in each test condition (table 2). Figure 3 shows the data sets for CIs placed in the left, middle and right po-

which were exposed to the ASP STERRAD EXPRESS process. (middle line) the range of values (whisker extremes) and theterns indicate statistical differences (SD) in values of E but not visible differences. Shaded boxes show both SD in values of E and observable differences in CI colour (see table 3).

Discussion

The response of the CIs.

Any given colour can be expressed by three coordinates L*, a* and b* and the addition of these three coordinates to give a value termed E is a numerical representation of the appearance of that colour (16). L* represents the lightness or darkness of a colour but the coordinates a* and b* represent the actual colour in terms of red (+a*), yellow (+b*), green (-a*), and blue (-b*). CIs will often have a dominant a* or b* coordinate and changes to these values may repre-

Table 2 : Visual interpretation of the colour change indicated by CIs exposed to the test conditions shown. Results are expressed as the number of Fail results within each replicate group when interpreted according to the manufacturers instructions ie comparison with a colour reference printed on the CI or in IfUs or as instructed by IfUs. The accuracy and precision, expressed as a percentage, of each set of indicators expresses a value related to the proportion of false and true pass and fails (see text)

Test Condition Location Within Tray AuCd (mean, range) (mg.s/l)

Xi. Xi Probe / ASP STERRAD EXPRESS cycle Left 1237 (9211453) 0/100/101/101/101/100/100/100/10

Middle0/100/102/101/102/100/101/100/10

Right0/100/101/104/102/100/100/100/10

DV1. One DaVinci probe / ASP STERRAD EXPRESS cycle Left 874 (7631146) 0/100/107/1010/1010/100/106/100/10

Middle0/100/107/1010/1010/100/107/102/10

Right0/100/105/1010/1010/100/106/100/10

DV2. Two DaVinci probes / ASP STERRAD EXPRESS cycle Left 838 (695965) 0/100/107/1010/1010/100/107/100/10

Middle0/100/108/1010/1010/100/107/100/10

Right0/100/107/1010/1010/100/108/100/10

StE. Stryker Camera probe / ASP STERRAD EXPRESS cycle Centre 1760 (15971971) 0/100/10 2/1010/1010/100/108/100/10

Outer Edges 4/200/2017/206/2020/200/2020/200/20

StS. Stryker Camera probe / ASP STERRAD Standard cycle Centre 6902 (66427371)

0/100/100/100/100/100/100/100/10 Outer Edges

0/200/200/200/100/200/200/200/20

a. Product F was extremely difficult to interpret with all CI colours being a similar turquoise / aquamarine /blue-green and therefore could be interpreted as a pass or fail.

b. The reference colour printed on CI H varied in depth of green some being much darker than others thereby giving rise to possible misinterpretation.

c. CIs C, D and E gave colour changes very close to their endpoint when exposed to test condition Xi making absolute interpretation of the result difficult. The following observations were interpreted as fails. Product D had a very slightly observable magenta ring around the central yellow portion. Product C was a red/yellow colour rather than the reference orange. Product E had a slightly mauve colour in the accept zone rather than the described pink.

d. AuC is the area under the VH2O2 concentration curve measured from within the chamber. Test condition Xi was significantly higher (p≤0.05) than test condition DV1 and DV2 which were equal.

sent a more sensitive means of evaluating change. However in terms of visual appearance changes in individual coordinates cannot be observed. For this reason expression of colour change using values of E and their differences is more representative of observed colour

Products B and H gave visual passes (except for 2 fails with H) in all test conditions with slight or no differentiation by visual interpretation (table 2 -

cult to interpret with all CI colours being a similar aquamarine which could be interpreted as pass (chosen) or fail. Some statistical differences in the values of E between loads and processes recommended by manufacturers and those not recommended were observed.

in low accuracy and precision values (table 2). Product B was a self adhesive label which was presumed to be catego-

rised as a process indicator for adhesion to external surfaces of packs. The green reference colour printed on product H varied in colour from one indicator to another giving rise to potential misinterpretation (see table 3).

Some samples of products C, D, E and G gave a colour change very close to their endpoint when exposed to test condition Xi making visual interpreta-

had a very faint but observable magenta ring around the central yellow portion interpreted as fail. Product C was a red/ yellow colour rather than the reference orange. In some cases product E had a slightly mauve colour in the accept zone rather than the described pink. Product G had inconsistent colour change across its indicator strip making interpretation -

solved by instructional material with examples.

Products C and D, were in general able to differentiate loads and processes recommended by manufacturers (Xi and StS), giving mostly visual passes, from loads and processes not recommended (DV1, DV2 and StE) giving a high proportion of, or all, visual fails (table 2 and

higher values for accuracy and precision. Numerically, SDs in values of E were not-

entiate between the conditions occurring at location left, middle right within load Xi, being visually similar and numerically not SD. However the group both visually and numerically differentiated edge to centre differences in test condition StE, although differences in E

Products E and G, were able to differentiate recommended loads and processes (Xi and StS) giving a high pro-

Table 3: Examples of the colour change indicated by CIs exposed to the test conditions shown (also see table 2). For product A the indicator colour in the final two rows had changed to a very light yellow which photographic reproduction has not detected.

Xi. Xi Probe / ASP STERRAD EXPRESS cycle Left

DV1. 1 DaVinci probe / ASP STERRAD EXPRESS cycle Left Middle

DV2. 2 DaVinci probes / ASP STERRAD EXPRESS cycle Left Middle Right

StE. Stryker Camera probe / ASP STERRAD EXPRESS cycle Centre Outer Edges

StS. Stryker Camera probe / ASP STERRAD Standard cycle Centre Outer Edges

For footnotes a to c see table 2

Figure 2: The values of E for CI sample sets A to H (table 1) when used in different test conditions.

Xi – Xi Probe in bespoke case exposed to EXPRESS Cycle

DV1 - One DaVinci Probe mounted in a metal sterilization container exposed to a STERRAD EXPRESS cycle

DV2 - Two DaVinci Probes mounted in a metal sterilization container exposed to a STERRAD EXPRESS cycle

StE - Stryker Camera Probe mounted in a sterilization container exposed to a STERRAD EXPRESS cycle

StS - Stryker Camera Probe mounted in a sterilization container exposed to a STERRAD STANDARD cycle

Open boxes showing different fill patterns indicate statistically significant differences in values of E but not visible differences . Shaded boxes show significantly different values of E and observable differences.

When the values of a* for product B were tested for significant differences all the indicators were statistically different. All other indicators had the same levels of statistical difference irrespective of comparing E, a* or b*.

When the values of a* for product D were tested for significant differences indicators from load Xi were equal but differed from indicators in load StE.

Zentralsterilization | Volume 28 | 6/2020

Figure 3: The values of E for CI sample sets A to H (table 1) when placed in positions left (L), middle (M) and right (R) of the Xi Probe container (figure 1A) and in positions edge (E) and centre (C) within the Stryker Camera probe container (figure 1D) and then exposed to an ASP EXPRESS cycle.

Open boxes showing different fill patterns indicate statistically significant differences in values of E but not visible differences . Shaded boxes show significantly different values of E and observable differences.

When the values of b* for product H were tested for significant differences the indicators located in the edge position in the StE cycle were statistically different to the values for indicators located in the centre position.

When the values of a* for product B were tested for significant differences the indicators located in the Xi load were significantly different to those located in the edge and centre positions of the StE load. Zentralsterilization | Volume 28 | 6/2020 341

In such circumstances the monitoring system associated with the sterilizer may show a reduction in chamber VH2O2 concentration but might not

conditions at location left, middle and had numerical SDs) and edge to centre

tiate between the different test conditions and the different locations with-

from 4 fails in the edge location of StE

reference orange colour. This was relighter in hue.

Colour Interpretation

colour blindness or stress levels, and environmental factors such as the lev-

might aid, but can also confuse inter-

these factors may lead to an incorrect-

within each instrument set, which has

ance documents [11, 20]. The results of using a range of monitoring systems, rather than relying on one, the information from which add to the overall sterility.

The value of type 4 versus type 1 and are designed to show that the load

Sterilizers using VH2O2 usually meas-

vs 7s;[10]) they will offer limited val-

to bring about a colour change in the the AuC measured in the chamber and

cantly different E values in different loinhomogeneous conditions. This may be due to changes in VH2O2 concentra-

rower window in the test conditions

have been encountered.

assurance of sterility for VH2O2 sterili-

tion involved very close scrutiny to de-

lowed observation of differences in E

the instruments and might be in subdued light so many indicators exhibit-

than ideal conditions are therefore more valuable than others which do not.

of

when routinely monitoring VH2O2 sterilizers and medical devices give recommen-

Zentralsterilization | Volume 28 | 6/2020

A, E and G showed visual and/or SD

tion in load Xi. CIs A, C, D, E and G all

middle clearly indicating differences in

surance associated with a load and in-

vices, sterile barrier systems or acces-

es between conditions measured in thecluding non-uniformity. Routine moni-

of VH2O2 is discussed in national guid-

to recommendations. Of the CIs exhibitthey were a valuable aid in detecting

cating failures due to incorrect loading

ble of indicating non-uniformity of ster-

ilizing conditions within instrument sets and would prove useful in PQ studies in addition to routine use for detecting sterilization failures. Of the CIs tested, the 3M-Trimetric had the highest accuracy and precision indices in terms of correctly detecting failures.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr Marco Bommarito, Mr Sandy Riley and Mr Lawrence Talapa of 3M USA for their support.

References

1.Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of the council of 5 April 2017 on medical devices , amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC, 5th May 2017

2.Submission and Review of Sterility In(510(k)) Submissions for Devices Labelled as Sterile. Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff, January 21 2016, Food and Drug Administration, Washington, USA

3.Block, S.S. (ed), Sterilization with ethylene oxide and other gases. In Disinfection, Sterilization and Preservation (4th ed). London, Lea and Febiger, 1991: 580–95.

4.EN ISO 17665, Sterilization of healthcare products – Moist Heat – Part 1: Requirements for the development, validation and routine control of a sterilization process for medical devices, 2006, CEN-CENELECManagementCentre: Avenue Marnix 17, B-1000 Brussels

5.ENISO 11135, Sterilization of healthcare products – Ethylene Oxide – Requirements for the development, valida-

tion and routine control of a sterilization process for medical devices, 2014, , CEN-CENELECManagementCentre: Avenue Marnix 17, B-1000 Brussels

6.ENISO 25424, Sterilization of healthcare products – Low temperature steam and formaldehyde – Requirements for the development, validation and routine control of a sterilization process for medical devices, 2014, CEN-CENELEC Management Centre: Avenue Marnix 17, B-1000 Brussels

7.ISO/CD 22441 Sterilization of health care products – Low temperature vaporized hydrogen peroxide – Requirements for the development, validation and routine control of a sterilization process for medical devices, 2019, International Standards Organisation, Geneva.

8.EN ISO 14937, Sterilization of healthcare products – General requirements for characterization of a sterilizing agent and the development, validation and routine control of a sterilization process for medical devices, 2009. CEN-CENELEC Management Centre: Avenue Marnix 17, B-1000 Brussels

9.EN ISO 11138 Sterilization of health care products – Biological indicators –Part 1: General requirements, 2017, CEN-CENELECManagementCentre: Avenue Marnix 17, B-1000 Brussels

10.EN ISO 11140-1, Sterilization of health care products – Chemical indicators –Part 1: General requirements, 2014, , CEN-CENELECManagementCentre: Avenue Marnix 17, B-1000 Brussels

11.ANSI/AAMI ST 58.:2013 Chemical sterilization and high-level disinfection in health care facilities , 2013, Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation, 901 N. Glebe Road, Suite 300, Arlington, VA 22203 USA.

12.UK Dept Health, National Decontamination Program, Theatre Support Pack, 2009. Dept Health London.

13.World Health Organisation, WHO surgical safety checklist, 2009. WHO, Avenue Appia 20, 1211 Geneva

14.Talapa, L, Vaporised Hydrogen Peroxide V H2O2 Sterilization; riding atop a new wave, presentation at IAHCSMM 2019 annual conference April 27th to May 1st, Anaheim, CA2019.

15.Kirk, B. Evaluation of a number of chemical indicators for monitoring vaporized hydrogen peroxide (VH2O2) sterilization processes. Zentr Steril, 2020; 28 (4): 208–217.

16.The International Commission on Illumination(Commissioninternationale de l’éclairage), CIE L*,a*,b* colour standard, 1976, CIE Central Bureau, Babenbergerstraße 9/9A, 1010 Vienna, Austria

Precision–https://en.wikipedia.org/

18.Hurlbert A, Pearce B, Aston S. All illuminations are not created equal: The limits of colour constancy. In: 38th European Conference on Visual Perception (ECVP). 2015, Liverpool, UK: Sage Publications Ltd.

19.Van Doornmalen, J.P.C.M, Hermsen R-J, Kopinga, K. Six commercially available class 6 chemical indicators tested against their stated values. Central Service 2012 (6): 400.

20.Scottish Health Technical Memorandum 01-01, Decontamination of Medical devices in a Central Decontamination Unit: Part E Sterilization by Hydrogen Peroxide or Ethylene Oxide. NSS Health Facilities Scotland, 2019.

Zentralsterilization | Volume 28 | 6/2020 343

Conference Dinner: Thursday 26th September Dinner theme: Fashion, Style, Music, History, and Events of 1974.

Right items, delivered to the right place, at the right time

Torin & T-DOC, you can ensure availability of items for each surgery as well as ensure surgical case carts or setup trolleys are delivered with the right RMD’s, implants, and consumables at the right place and at the right time.

With Torin and T-DOC working together as one you can improve delivery for surgeries whilst:

• Reducing strain on hospital staff

• Keeping track of your equipment

• Providing real time updates and progress

• Reducing impacts on patient while improving the patient experience

www.getinge.com/anz For more information email sales.nz@getinge.com or call 0800 143 8464

Donna Dador and her team celebrated SSD Sterilisa on Day back in April 2024. Above are some pictures from that celebra on.

By JeyJeyarajah

SterileServicesUnit,WaikatoHospital,Hamilton

ThereprocessingstandardAS5369:2023requiresthefollowingasmanagement responsibilitiesofaSterileSciencesUnit[SSU].Theresponsibilitytoimplementrequirements ofAS5369:2023andrelevantnominativestandards,implementingpoliciesandprocedures, supervisionofdailyactivities,ensuringthestaffeducationbyformalorientation,training,and development,andensuringappropriateresourcesareavailableforreprocessingtheReusable MedicalDevices[RMD]accordingtothestandardrequirementsaretheresponsibilitiesofthe personwhoisresponsibleforthefacility.Thus,therolesofaSSUmanagerincludeoperational management,strategicmanagement,andleadership.

TheoperationalmanagementskillsofanSSUManagerinvolveconvertinginputsintoproducts andservicesbyaneffectiveandefficientprocess.Itensuresthataprocessdeliversaproduct orserviceatanexpectedqualityatthelowestcost.Thus,theoperationalmanagementofa reprocessingserviceincludesplanning,organizing,directing,andcontrolling.Effectiveplanning canbeachievedbyimplementingpolicies,educatingandempoweringstaff,monitoringto ensuretherequiredtargetsaremet,andensuringqualityimprovementachieved.Thetasksfor organizingincludeorganizingsufficientqualifiedstaffandadjustingsufficientresource requirements.Thetasksfordirectingincludeallocatingstafftoensuresmoothoperationsofthe processandallocatingrequiredresourcestomanagechanges.Finally,tasksforcontrolling includeverificationofthecosts,andauditingtoensuretheprocessadherestotheQuality ManagementSystem[QMS](Theopenuniversity).Therefore,itisessentialfortheoperations managertoeffectivelycarryoutthedutiestoestablishandmaintainacomprehensivestaff traininganddevelopmentprogram,effectiveleadershipandteamcommunication,teamwork, andstrategicallymanagedHumanResourceManagement[HRM].

Traininganddevelopmentareprovidedbyanorganizationtoimprovetheknowledge,skills,and attitudeoftheemployeeswiththeexpectationtoimprovegrowth,productivity,stability,talent pool,andjobsatisfaction,andreduceaccidents,mistakes,waste,andsupervision(Surbhi, 2019).SSUtechniciansworktirelesslytopreventnosocomialinfectionsinhealthcare.The outcomeofsurgicalproceduresfundamentallydependsonthetaskscarriedoutbytheSSU technicians.Theymustbeeducated,trained,andempowered(Ricupito2009).Trainingis short-termanddesignedtoeducateanemployeetoperformaspecifictask.Ontheotherhand, developmentistopromoteanindividual’sleadershipskillsthroughalong-termlearningprocess (Murugesan,2011).TraininganddevelopmentmustbeaContinuousQualityImprovement [CQI]goalforthesuccessandenrichmentofanSSU.Theymustmeetthecurrentandfuture needsofanSSU.Strengths,Weaknesses,Opportunities,andThreats [SWOT]analysisisan excellenttoolforanalyzingthetrainingrequirementsforrefreshertraining(Milhem& Abushamsieh,2014).OthertypesoftrainingcanbeprovidedbytheAnalyze,Design,Develop, Implement,andEvaluate[ADDIE]model.HRMmustrecognizethestrategicgoalsoftheSSU

withtheaimofContinuousQualityImprovement(CQI)andproductivity(Milhem& Abushamsieh,2014).

Softskillsareequallyimportantasformaleducationandlearningskillsfortoday’sjobmarket. Employeeswithexcellentsoftskillscanincreaseproductivitytoadifferentlevel.Softskillsare notpartofthelearningstrategy.Theyarepartofabusinessperformancestrategythatenables anemployeetoacquireanddevelopknowledgeandskillsthroughsocialcapital(DeakinCo, 2017).

EffectiveleadershipcommunicationisrequiredtomaintainandcontinuouslyimproveSSU.A supportiveleadershipstyle,behaviors,andcommunicationinfluenceorganizationalculture,the learningclimateofanSSU,processimplementation,adherencetoQMS,andrelevant standards(Knoblochetal.,2019).Themostimportantsoftskillsofleadershipcommunication areearningtrust,empathy,andgoodlisteningtoengagewiththeteammemberseffectivelyto implementchanges(SpriggHR,2021).Listeningisimportantforrelationshipsforboth managersandnonmanagers.Manageriallisteningcontributestoemployeemotivation, recognition,andproduction.Managerswhohavegoodlisteningskillscanpromote organizationalcultureamongemployees.However,nationalcultureinfluencesthelistening behaviorofmanagersaswellasnonmanagers.Therefore,thereisaneedtounderstandthe nationalculturetoimprovegoodlisteningbehavior.Theglobeleadershipprojectidentifiednine leadershipdimensionsamongdifferentnations(Roebuckal.,2016).Thefollowingtable summarizesNewZealand’spositionin6dimensionsbasedonthe“6-DModel”(Theculture factorgroup).

Teamcommunicationisimportantfororganizationaltransformationandperformance.Team communicationisanexchangeofallinformationandinteractionstoachievetheteam’sgoal.It enablesteammembersnotonlytocollect,identify,interpret,andevaluatethedataand informationgeneratedduringthereprocessingprocessesbutalsoenablethemtointeractand exchangetheinformationtoachievetheirgoals(SpriggHR,2021).Acohesiveteamwith excellentleadershipandteamcommunicationworkinginalearningenvironmentwillmeetthe majorgoalsoftheHRMandorganizationalculture.Effectiveteamcommunicationinfluences performanceandmorale,betterteamcohesion,providesanidealenvironmentforCQI,and helpstoachievetheorganization’sgoals,highperformance,andproductivity(Hassall,2009).

Inconclusion,anSSUthatsupportscontinuoustraininganddevelopmentandlearning environment,excellentleadershipandteamcommunication,teamwork,andstrategically managedHRMwillenhanceproductivityandorganizationalculture.

TheStrategicmanagementskillsofanSSUManagerinvolveprovidingavisionforthe organization.Ourworldischangingrapidly.Thedemandtoimproveproductivityis ever-increasing.Theneedfor“rapidimprovementinefficiencybyaveryeffectiveprocess” requiresaclearvisionforchange.Strategicmanagementprovidesadirectiontotransforman organization’svisionintoreality.Itprovidescleargoalsforthestakeholders,enablesthe organizationtofulfilltheregulatoryrequirements,enablestheC-suitedecision-makersto understandtheenvironmentdoesnotchangeannuallyorperiodicallyhavetoberegularly reviewedandmadeadjustments,andprovidesleadership.Moreover,aclearvisionfromgood leadershipempowerseveryemployee(NewZealandManagement,2010).

Leadershipskillsarerequiredtoprovidechange.TheHealthQuality&SafetyCommissionNew Zealand,2016requiresthatleadersmustsetanexamplebydoingwhatisright,implementand supporttheimprovementofqualityandsafety,andguidethequalityandsafetyimprovements basedontheorganizationalandnationalgoals.Moreover,leadershiprolesinalllevelsofthe healthcaresystemhaveincreasinglybecomeimportanttoimproveefficiencyandproductivity. Thecontemporaryleadershiptheoriesofhealthcareincludegreatmantheory,traittheory, behavioraltheory[includesautocratic,democratic,andlaissez-fairestyles]contingency leadershiptheory,transactionalleadership,andtransformationalleadershiptheory(Kumarand Khiljee,2016).ThesearchforidealleadershipinSSUisdebatable.Thereareeightmajor attributesforSterileServicesleadership.Firstly,Leadershiprequiresanunderstandingoffuture trends.Theymustbeabletomakechangesthroughinnovation,insightfulness,andconfidence. Continuousimprovementrequireswinningthesupportandcommitmentofthestaff.Secondly, leadershiprequiresanunderstandingoftherolesoftheotherstaffandmakingchangesby qualified,competent,andskillfulleaders[credibility].Thirdly,thebestandbrightesttechnicians mustbemanagedbyconnectingandengaging.Leadersmustfulfilltheneedsofthe technicians,shareknowledgeandskillsandsomotivateandinspirethem(Jelks2019). Fourthly,leadersmustbeabletoinspireateamduringdifficultsituations.Theymustbeableto understandtheiremotionsandothers.“Peoplemayhearyourwords,buttheyfeelyourattitude” (Jelks2019).Tounderstandandmanageemotions,leadersmustcommunicatepositivelyand

possessexcellentinterpersonalskills,suchasemotionalandsocialintelligence.Fifthly,conflicts mayarisewhenmakingchanges,becausestaffmembersmaynotagreewiththechanges. Leadersmustbeabletoresolveconflictsbyunderstandingthereasonsfortheemotional discomfort.Theymustacknowledgeandexpresstheirconcerns,identifythemeanstoresolve conflicts,discusstheoutcome,andunderstandbygettingfeedback.Managingachangeand resolvingconflictsrequirepatient,persistent,andinsightfulleadership(Jelks2019).Sixthly, leadersmustinvolveallstaffmemberswhenmakingchangesbyusingqualitytoolssuchas brainstorming.Tosolveproblemsduringchangesleadersmustthinkcriticallywithanalytical skills.Seventhly,leadersmustactasrolemodelstobetrustedandrespected.Finally, leadershiprequiresadministrativeskillsforplanning,organizing,directing,andcontrolling (Ricupito2009).Themainattributesoftransformationalleadershiparetomotivateandinspire employees,overcomesocialandemotionaldiscomforts,andengagewithemployees. Transformationalleadersarecharismaticaswell.Therefore,anidealleadershipforanSSU manageristransformationalleadership.

Inconclusion,themainobjectiveofSSUmanagementistomaintainandcontinuouslyimprove theunit’sLeadership,Human,Physical,Social,andCulturalcapital(organizationalculture). Theorganizationalculturedependsonthevalues,beliefs,andbehaviorsofstaff,andinteraction ofemployeesandthemanagementstaff,andtheviewofthepublicoftheorganization.Agood organizationalcultureisstrongemployeerelationships,evidenceofmotivation,trustand integrity,excellentteamwork,innovation,andemployeeresilienceforchange(Jain&Jain, 2013).Moreover,theorganizationalculturemustmeettherequiredactionslistedundersection 3ofthe“frameworkforbuildingqualityandsafetycapabilityintheNewZealandhealthsystem” (HealthQuality&SafetyCommissionNewZealand,2016).Theorganizationalcultureofan SSUcouldbecomparedtoaplant.Thenitsleaves,flowers,andbranchesaretheunit’s mission,strategicplans,goals,website,anditsrecognizedstaffmemberswhomadesignificant contributionstoSterileservices.Thesearetheartifactsoftheorganizationwhicharevisibleto membersofthepublic.Itstrunkisthevaluesoftheunit,whicharethepolicies,procedures, records,andQMS.ThesearevisibletomembersofthepublicandSSUstaff.Itsrootsarethe assumptionsthatincludebehaviors,andbeliefsoftheemployeesthatarevisibleonlyto employeesonly.

References

DeakinCo,.(2017). Howmicro-credentialscanpreparepeopleforthefutureofwork https://www.deakinco.com›Resources

HealthQuality&SafetyCommissionNewZealand.(2016). Fromknowledgetoaction.

Hassall,S.L.(2009).Therelationshipbetweencommunicationandteamperformance:testing moderatorsandidentifyingcommunicationprofilesinestablishedworkteams.PhDthesis, QueenslandUniversityofTechnology.https://eprints.qut.edu.au

Jain,A.,&Jain,S.(2013).Understandingorganizationalcultureandleadership-enhance efficiencyandproductivity.TheJournalofManagementAwareness,16,(2),43 https://www.indianjournals.com/ijor.aspx?target=ijor:pr&volume=16&issue=2&article=004

Jelks,L.(2019).Employeeengagement!Managingoutbestandbrightestinsterileprocessing. HealthcarePurchasingNews,43,(12),34-37.

Knobloch,M.J.,Musuuza,J.,Safdar,N.,&Thomas,K.V.(2019).Exploringleadershipwithina systemsapproachtoreducehealthcare–associatedinfections:Ascopingreviewofonework systemmodel. AmericanJournalofInfectionControl, 47(6), 633–637.https://doi-org.ezproxy.toiohomai.ac.nz/10.1016/j.ajic.2018.12.017

Kumar,R.D.C,&Khiljee,(2016). Leadershipinhealthcare. AnaesthesiaandIntensiveCare Medicine, 17(1),DOI:63-65.10.1016/j.mpaic.2015.10.012

Milhem,W.,&Abushamsieh,K.(2014).TrainingStrategies,TheoriesandTypes. Journalof Accounting–Business&Management,21(1),12-26. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Khalil-Abushamsieh/publication/269165999

Murugesan,G.(2011). Humanresourcemanagement.

NewZealandManagement.(2010). Strategicmanagement:thestrategicplan–isitrelevant anymore? https://management.co.nz/article/strategic-management%C2%A0-strategic-plan-it-rel evant-any-more

Openuniversity.(n.d.). Understandingoperationsmanagement. https://www.open.edu DeborahBrittRoebuck1,ReginaldL.Bell2,

Roebuck,D.B.,Bell,R.L.,Raina,R.,&Lee,C.E.(2016).Comparingperceivedlistening behaviordifferencesbetweenmanagersandnonmanagersLivingintheUnitedStates,India, andMalaysia. InternationalJournalofBusinessCommunication,53(4),485-518.

Ricupito,G.(2009). Buildqualityleadershipforastrongerdepartment,organization. Materials managementinhealthcare, 18(1), https://www.researchgate.net/scientific-contributions/Gene-Ricupito-36621456

StandardsAustralia.(2023). Reprocessingofreusablemedicaldevicesandotherdevicesin healthandnon-healthrelatedfacilities (AS5369:2023). https://store.standards.org.au/product/as-5369-2023

SpriggHR,(2020).Theimportanceofleadershipcommunicationin2021. https://sprigghr.com/blog/leaders/the-importance-of-leadership-communication-in-2021/

Surbhi,J.(2019). HRsolutionsforexcellenceintrainingdevelopment. TheCultureFactorGroup.(2016).(n.d.). CountryComparisonTool.

ECOLAB HEALTHCARE ANZ

7A Pacific Rise, Mount Wellington, Auckland 1060, New Zealand

NZ: 0800 425 529 www.healthcare-nz.ecolab.com E: salesanzhc@ecolab.com

“Exploring

Hafiz Abdul Mannan

CSSD Technician

Hamad Medical Corpora on, Qatar

Abstract

For appropriate disinfec on and steriliza on, following professional recommenda ons and manufacturer's instruc ons is crucial in order to prevent crosstransmission of pathogens. Neglec ng this crucial step can lead to dire consequences, par cularly with the emergence of new pathogens and the use of complex medical devices. A search was directed using different search engines including google scholar, and PubMed to find ar cles on novel disinfec on and steriliza on methods. A number of promising disinfec on methods and steriliza on technologies have recently been iden fied. These include electrosta c spraying, which uses an electrically charged mist to evenly distribute disinfectant over surfaces, and new sporicides, which are specifically designed to kill bacterial spores that are especially resistant to tradi onal disinfectants. Addi onally, colorized disinfectants colorized disinfectants, “no touch” room and “con nuous room” decontamina on have been developed. Finally, a new steriliza on method for endoscopes has been developed. It is expected that these new technologies would greatly lower the risk of infec on for both pa ents and medical staff.

Keywords: steriliza on, disinfec ons and current trends.

Introduc on

Since the inven on of the germ hypothesis of disease by Louis Pasteur, medical science has advanced significantly. Since that me, preven ng and controlling of different microorganisms everywhere, par cularly in healthcare ins tu ons, has become the primary job of physician (1).

Hospital acquired infec ons are a global health concern. Hospital infec ons are es mated to affect about 1.4 million people worldwide, with 80000 fatali es annually. Due to microbial contamina on in the hospital specialized units, the occurrence of nosocomial infec ons rises. Pa ents are seriously threatened by the illnesses brought on by bacteria resistant to an bio cs, which are acquired in the opera ng rooms and intensive care units. The occurrence and dissemina on of microbial resistance are commonly associated with the presence of hot zones in ICU (2).

Nosocomial infec ons, par cularly surgical site infec ons (SSIs), are a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality following surgery. They rank as the second most prevalent type of infec on a er urinary tract infec ons (UTIs) and pose a primary challenge in the field of surgery. . Infec ons can originate from both external and internal sources, including the air, soil, dust and surfaces found in OTs. Microbiological environmental and procedural surveillance play crucial roles in infec on control programs. It provides the data according to the types and number of microbial flora (3).

Hospital acquired infec on effect five to ten % of all pa ents enlisted to the hospital in developed countries. They have an impact on quarter of hospitalized pa ents in low-income countries. Therefore, it is obvious that examining the hospital se ng is a central sec on of aver ng nosocomial infec on. Infected personnel, staff movement and outsider loads are the most important cause of droplet genera on. Inappropriate use of methods of microbial control is a substan al risk factor of SSI (4).

Implemen ng steriliza on and disinfec on measures is of utmost important to prevent the emergence and spread of microbial resistance in the health care areas. These areas are frequently recognized as cri cal zones owing to invasive procedures, extensive an bio c usage, and the risk of bacterial transmission among pa ents. To effec vely monitor the presence of microbial flora and detect any changing trends, it is beneficial to conduct microbiological tes ng of surface and equipment, as well as biological air sampling to assess the types and quan es of microorganisms present in the indoor air. By implemen ng proper measures to control air borne pathogens, we not only ensure the wellbeing of pa ents but also subsidize to the complete wellbeing of the hospital environment. Furthermore, it is essen al to establish a surveillance system and early warning mechanisms at the local, regional, and na onal levels in order to promptly iden fy signs of emerging or increasing microbial resistance (5).

Disinfec ng and sterilizing of medical instruments and environmental surfaces are crucial to avoid the spread of infec ons. Innova ve techniques and trends are con nuously evolving in healthcare setup. Processes for disinfec on and steriliza on are categorized into different types: cleaning, low to high-level disinfec on, and steriliza on (6).

Steriliza on eliminates all microorganisms from an object such as surgical instruments and implants that must be

sterile before coming into contact with sterile ssue or vascular system to prevent disease transmission. These objects should be bought sterile or sterilized using steam steriliza on, ethylene oxide, hydrogen peroxide gas plasma, vaporized H2O2, H2O2 vapor with ozone, or aqueous chemical sterilants if other techniques are ineffec ve (6).

A number of promising disinfec on methods and steriliza on technologies have recently been iden fied. These include electrosta c spraying, which uses an electrically charged mist to evenly distribute disinfectant over surfaces, and new sporicides, which are specifically designed to kill bacterial spores that are especially resistant to tradi onal disinfectants. Addi onally, colorized disinfectants colorized disinfectants, “no touch” room and “con nuous room” decontamina on have been developed. Finally, a new steriliza on method for endoscopes has been developed (6,7). This paper provides an overview of the latest technologies and developments of these processes.

New developments in disinfec on Electrosta c spraying

Within healthcare services, surfaces are disinfected using disposable wipes or disinfectant applied with a cloth. However, electrosta c sprayer devices that deliver electrosta cally charged droplets of disinfectant can be more effec ve. These droplets, a racted to surfaces, contain 0.25% sodium hypochlorite and reduce contamina on by microbes on uneven surfaces, such as

mobility aids, handheld devices, and wai ng area seats. The sprayer requires minimal precleaning/disinfec on, and chlorine has been found to reduce spores and plaque-forming units with short contact mes. Electrosta c sprayers can be used as supplemented technology to surface disinfec on with wipes in pa ent accommoda ons and for decontamina ng portable equipment on contact precau ons or all pa ent rooms. A trial found that adjunc ve UV-C light treatment with a room decontamina on device, and sodium hypochlorite delivered via electrosta c sprayer were all opera ve in lowering remaining health care-associated infec ous agents on floors and high-touch surfaces a er manual disinfec on. Instead of environmental services workers, research staff has conducted the current effec veness evalua ons (8,9).

Given that this technique relies on me culous applica on, it is plausible that if environmental service professionals use the sprayer and apply it less thoroughly than desirable, the electrosta c sprayer's effec veness might be inferior to that of UV-C (9).

Furthermore, more research is required to determine the level of cleaning and disinfec on required to guarantee efficacy in lowering microbial contamina on. This degree of cleaning and disinfec on may vary depending on the usage of disinfectants and electrosta c spray technology (9).

Figure 1: Summary of issues that should be considered when purchasing or using an electrosta c sprayer

-Disinfectant should be tested and approved by the EPA for use with an electrostatic sprayer(i.e. system consist of sprayer and disinfectant)

-Disinfectant safety (i.e. sporicicdal or non-sporicidal)

-Disinfectant safety (i.e. EPA category 2,3 or 4)

-Well-suited for irregular devices with multiple angles

-Spray distance

-Spray Application speed

-Spray Coverage

-Spray method (i.e. S-pattern with overlap)

-Contact time

-Quantity of water used and sprayer on surfaces

-Uniformity of spray or spray coverage

-Odor and persistence

Gram-posi ve, anaerobic bacteria called Clostridium difficile establish colonies the human diges ve tract when an bio cs disturb the balance of the gut microbiota. C difficile infec on (CDI) is a common infec on associated with health care, with 202,600 cases and 11,500 deaths in the U S in 2019 (10).

This spreads through the fecal-oral route. A study shows that hospital rooms where CDI pa ents are treated, and healthcare personnel who take care for those pa ents, are infected. A pa ent's chance of developing CDI increases when they are admi ed to a room where a pa ent with CDI has previously resided (11% prior occupant with CDI, 4% prior occupant without CDI, or 239% greater risk). The main measures to prevent CDI include decreasing use of CDI-precipita ng medica ons, placing CDI pa ents in isola on with gloves and proper hand cleanness, and using sporicidal agents for improved room disinfec on (11).

Several disinfec on strategies have been successful in reducing cases of CDI. Mayfield and colleagues found that room disinfec on with 1:10 hypochlorite directed to a significant reduc on in these infec on cases from 8 to 3 per 1,000 days in a transplant unit. However, when they reverted to using a quaternary ammonium compound, the infec on rate increased to 8.1 cases per 1,000 days (12).

Similarly, another study reported a noteworthy lower in CDI on one of two wards while using hypochlorite. Another study by Orenstein et al that used bleach wipes (0.55% ac ve chlorine) for both daily and terminal cleaning, demonstrated a reduc on in C. difficile on two wards for which C. difficile was hyper-endemic (13).

According to the recommenda ons of the Centers for Disease Control and Preven on (CDC), in the case of a C. difficile infec on, sporicidal disinfectants are o en used in pa ent rooms; nonsporicidal disinfectants are typically used in all other pa ent rooms (6).

However, numerous sporicidal chemicals have proper es that deject their use. For instance, sodium hypochlorite is destruc ve and may develop respira onal irrita on in personnel and pa ents. Perace c acid-hydrogen peroxide products are more stable in terms of materials compa bility but have been reported to cause eye, upper and lower airway irrita on in working staff (14).

A new disinfectant with 4% hydrogen peroxide was found effec ve in killing C difficile and other pathogens. It has good material compa bility, a 24-month shelf life, and a ready-to-use form. It can kill vegeta ve bacteria in 1 minute and C difficile spores in 5 minutes, but a study showed it can reduce C. difficile spores by 4.7-log10 in just one minute (15).

Colorized disinfectant

Opera ve disinfec on of surface is important in aver ng spreading of healthcare-associated pathogens. However, subop mal disinfec on is common, and studies show less than fi y% of high-touch surfaces are disinfected. Thoroughness monitoring can expand disinfec on, but it is difficult to endure. Surface disinfec on is crucial to prevent transmission of pathogens and is an important infec on preven on strategy. Although disinfec on interven ons have shown to be effec ve in dropping microbial load and healthcare-associated infec ons, many surfaces remain ineffec vely disinfected and contaminated (16).

A new disinfec on method involves adding a blue color indicator to the disinfectant. This helps visualize surface coverage and contact me for thorough disinfec on. The blue color fades a er 4 minutes. It can be dispensed through a lid device on any standard commercially available wipes container. This provides real- me visual feedback for staff and ensures complete surface coverage (17).