By Jeremy Nobile

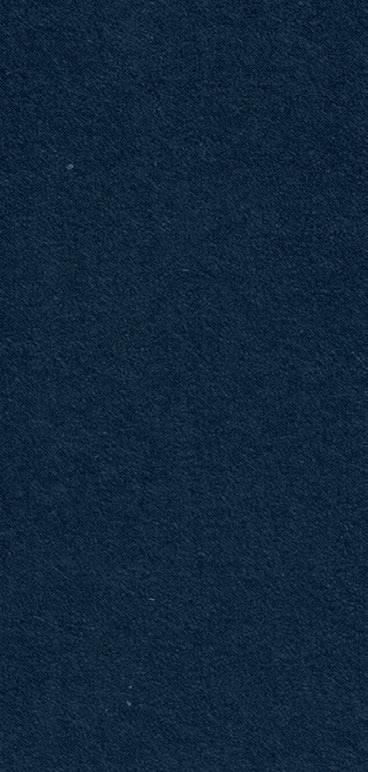

With manufacturing now underway at Cleveland Whiskey’s long-simmering expansion project along the Flats South Bank, founder and CEO Tom Lix’s ambitious vision for the craft distillery is be-

ginning to take shape — though there is still much work to be done.

“It feels great,” said Lix, surveying the renovations completed so far just to move into the historic riverfront building once home to e Consolidated Fruit Auction Co. more than 100 years ago. “At the same time, I still feel the weight of what we have yet to do.” is is the start of a big new chapter for Cleveland Whiskey, which relocated to its new campus near Collision Bend at 601 and 501 Stones Levee in July.

By Joe Scalzo

Anyone who has watched Guardians closer Emmanuel Clase over the last four years has probably had two thoughts:

◗ is guy is amazing.

◗ How long before he’s pitching in New York?

A crowdfunding platform called Finlete is giving Clevelanders a chance to profit off their fatalism, offering investors the chance to earn up to 3% of Clase’s future MLB earnings. Finlete is selling 300,000 shares

See CLASE on Page 16

After lots of building rehabilitation,

the distillery began making new products at 601 — formally known locally as the Malcom Building — in September. Now begins the tasks of scaling up production and preparing for a growth spurt.

See WHISKEY on Page 16

CRAIN’S FORUM: An algal bloom crisis in Toledo pushed Michigan and Ohio of cials, scientists and activists into action. Ten years later, progress hasn’t been easy. PAGE 8

By Stan Bullard

Shortly after Tom Einhouse joined the maintenance sta at Playhouse Square Foundation in 1980, he was repairing something — he cannot recall exactly what because sta often xed many things then — and asked if there were any nails available.

He was presented with a can of nails, all rusty. "I thought, 'Is this the best we can do?' " Einhouse recalled.

In those days, a few years after a community outcry saved two of the theaters from demolition, the quest to restore Cleveland's 1920s vintage theaters was low-budget stu . Today, as Einhouse is set to retire at year's end as vice president of facilities and maintenance, the nonpro t is in a far di erent place than where he started 44 years ago.

e organization now has a $93 million annual budget, ve artfully restored historic theaters with busy schedules and a ranking as the nation's second-largest performing arts center.

“Tom has been at Playhouse Square so long, it’s like he’s been a xture there,” said Kathleen Crowther, president and executive director of the Cleveland Restoration Society, where Einhouse serves as a life trustee. “Tom is excellent at managing lots of details but cutting through the noise to push something further.”

Describing Einhouse as a xture is telling.

Following directions set by four presidents at the foundation, he implemented plans for tasks as various as the restoration of elements of the theaters to putting in a streetscape designed to let people know they were in

the theater district. e streetscape job included the landmark chandelier hanging over Euclid Avenue. e idea behind it was a placemaking e ort based on giving people who might

not attend events in the theaters a sense of them as, in a phrase, chandelier rich.

Einhouse talks about what it was like to stand inside the chandelier as it was installed and look

working on theater restoration projects, which Shepardson did around the country.

“We traded chandeliers,” Einhouse said, re ecting the puzzlesolving aspect of restoring old playhouses with, when possible, surviving relics that might t in various places today. However, he does not know how many chandeliers there are at the vetheater complex.

“Too many to count,” he said. Einhouse became involved in Playhouse Square by happenstance. A friend asked him to help crew a rock concert in the late 1970s. It was so much fun to be around the theater, he got the bug to get more involved. A business graduate of what is now Baldwin Wallace University, Einhouse at the time was selling products to architects. He did not enjoy it. So he jumped at the

Playhouse Square job.

Jules Belkin, who co-founded Belkin Productions with his late brother, Mike Belkin, remembers Einhouse from that era.

“We were working at Playhouse Square just after it was on the verge of being torn down. We did concerts to try to help them out,” Belkin said in a phone interview. “Tom was like part of the family. He was quiet and reserved. He liked to get involved in new things. It’s no surprise he went as far at the foundation as he did.”

Among the many jobs Einhouse took on at Playhouse Square, one that he describes with grati cation was working on the lobby of the Mimi Ohio eatre. e original lobby Italian Renaissance lobby from 1921 was re-damaged and ravaged by neglect. When the theater was restored, the lobby was covered with drywall and painted pale green.

“Before that, you could stand in the lobby and look outside,” he recalled.

“One day (former Playhouse Square CEO) Art Falco came into my o ce with a black and white photo of what the Ohio’s lobby originally looked like. He asked if we could bring it back,” Einhouse said.

e ensuing quest would take Einhouse, already known as Playhouse Square’s archivist, to Columbia University in New York City to study plans by the building’s architect, omas Lamb.

“We had to scrape it down to the bare walls,” Einhouse said. Molds were made to reproduce the ornate ceiling, which were cast separately in plaster panels. Construction workers then installed them on the ceiling of the huge lobby. Long-lost murals were produced.

Pointing to a decorative column in the lobby, Einhouse said its nal exterior was formed from plaster. “ at’s much less expensive than replacing the original eight mahogany tree trunks that were here,” he said.

e $5 million project was accomplished in 10 months.

“When I hear people look at this lobby and say, ' ey don’t make them that way anymore,’ I like to point out that we can. We did it in 2016.”

Je Greene, chair of EverGreene Architectural Arts of New York, was the architect on that lobby renovation along with other works at Playhouse Square. He said Einhouse was hands-on and eager to nd pragmatic solutions while setting the bar high for projects.

“We were once at a meeting at my house and the lights went out,” Greene recalled. “Tom went down

as director of its annual fund.

“I used to joke that I raised money and he spent it,” she said. Cindy Einhouse plans to join Tom Einhouse in retirement in April when she will step down as president and CEO of Beck Center for the Arts in Lakewood. Together the two plan to form their own so-far unnamed consultancy related to their arts and building backgrounds.

“I’m retiring from Playhouse Square, not from life,” he said. Einhouse will continue to represent Playhouse Square on the Downtown Cleveland Alliance board. He previously chaired the

“Tom was like part of the family. He was quiet and reserved. He liked to get involved in new things. It’s no surprise he went as far at the foundation as he did.”

Jules Belkin, co-founder of Belkin Productions

in the basement and started guring out how it worked and how to x it. I thought, 'Here is an executive who gets right into what needs to be done.’ “

Part of that, long before the big capital projects came on, was his original “do what it takes” job at Playhouse Square. e job also shaped his life. Einhouse met his future wife, Cindy, there in 1981 where she was working as a receptionist in her rst job after graduating from college.

“I saw this cute maintenance guy washing windows,” Cindy Einhouse recalled in a phone interview. ey were married in 1983. She moved through several jobs at the foundation, at the last serving

Downtown Cleveland Improvement Corp. board, the property owner-led component of the downtown special improvement district.

A Lakewood native who continues to live there, Einhouse served on the Lakewood Planning Commission and Lakewood School Board. Einhouse said his experience with the western suburb’s planning commission helped him in relations with Cleveland o cials by giving him an appreciation for factors a city must consider, as opposed to those of his own organization.

Much of Einhouse’s work at Playhouse Square has involved the minutiae of getting building and

other projects done.

Danny Barnycz, chief creatologist at the Barnycz Group of Baltimore, worked with Einhouse on streetscape projects and the new theater marquees nished earlier this year. He said that after larger decisions were made by the board and president, he and Einhouse worked up ow charts of steps needed and vendors or people to contact for each stage of the project.

“Einhouse knows something I wish real estate developers would learn,” Barnycz said. “Time is the killer of all good ideas. Make decisions. Developers say they want meetings to nd the best designer and, after selecting them, pay no attention to their recommendations. Not so Playhouse Square.”

Like others, Barnycz praised Einhouse’s skill as a communicator and being able to work with diverse types of people. “When we were installing the arches at Playhouse Square, Tom made sure the people who would maintain them knew how they were put together. He’s great at getting stakeholder buy-in.”

Joe Marinucci, who recently retired as the head of what’s now Downtown Cleveland Inc., also worked with Einhouse at Playhouse Square. When the foundation was creating a small park and stage at the intersection of Huron Road, Euclid and East 13th Street — giving Playhouse Square an actual square — there was a stint of bad weather, and masons were falling behind.

“Tom suggested that we buy them lunch to keep the construction workers on-site,” Marinucci said. “We met our deadline."

By Paige Bennett

Dr. Christine Alexander-Rager will continue serving as MetroHealth’s president and CEO through next year.

The health system’s board of trustees voted Tuesday, Oct. 8, to promote Alexander-Rager to the role effective immediately. She has held the position on an interim basis since late July when the board voted to terminate President and CEO Airica Steed’s contract immediately and without cause.

icine physician, has been with Cuyahoga County’s safety-net hospital for almost three decades. She previously served as MetroHealth’s interim chief physician and clinical executive, overseeing the health system’s clinical enterprise.

“Dr. Alexander-Rager cares deeply about this institution, our employees and our community,” MetroHealth Board of Trustees Chair Dr. E. Harry Walker said in a prepared statement.

Alexander-Rager’s contract will run through 2025, according to a news release issued by MetroHealth.

of roles with MetroHealth, including 14 years as chair of family medicine. She founded the health system’s School Health Program, a collaboration with area school districts that brings in-school clinics and services to students and families.

“There is no group of caregivers more devoted, more caring and more committed to patients and to our community than MetroHealth’s 9,000 caregivers,” Alexander-Rager said in a statement. “It is an honor to be leading them and to be guiding our health system into the future.”

Crain's has reached out to the board to inquire about their intentions for lling the role once Alexander-Rager's contract expires.

Alexander-Rager, a family med-

“In her 27 years at MetroHealth as a primary care physician, she has always put our patients’ well-being at the center of every decision, every initiative and every moment of care. Her vision for MetroHealth and her deep commitment to our mission make her the ideal leader to guide us forward.”

Throughout her career, Alexander-Rager has held a variety

Alexander-Rager earned her medical degree from Ohio State University’s College of Medicine & Public Health. She completed her residency in family medicine at Philadelphia’s omas Je erson University Hospital, along with fellowships in family medicine and obstetrics and academic medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s St. Margaret and Mercy hospitals.

By Paige Bennett

e Buckeye State is home to some of the best children’s hospitals in the Midwest, according to U.S. News & World Report’s 20242025 rankings.

Cincinnati Children’s and Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus tied for rst place in the region in the latest version of the well-known rankings.

Cleveland Clinic Children’s and UH Rainbow Babies & Children’s shared third place, with Akron Children’s taking No. 15 (tied with Michigan’s Corewell Health Helen Devos Children’s) and Dayton Children’s Hospital taking No. 19 (tied with Kentucky Children’s Hospital and Children’s Nebraska).

All six Ohio hospitals ranked in the top 50 nationwide for behavioral health, a new ranked speciality added to this year’s report that looks at programs addressing mental health challenges and developmental problems in children and adolescents.

Nationwide and Cincinnati Children’s nabbed spots on the Honor Roll, a list of 10 hospitals that earned the most points for being highly ranked in many specialties. U.S. News & World Report did away with ranking Honor Roll hospitals numerically, a move that has come amid criticism that the ranking system incentivizes hospitals to prioritize certain specialties to increase their scores.

e organization has not ranked health systems on its Best Hospitals’ Honor Roll numerically since 2022. Cleveland Clinic was the only Ohio health system

to be placed on the 2024-2025 Honor Roll, which came out this past summer.

U.S. News & World Report has been evaluating pediatric hospitals since 2007. e media company evaluates children’s hospitals in 11 pediatric specialties including cancer, orthopedics and cardiology and heart surgery.

is year, the organization worked with RTI International, a North Carolina research and consulting rm, to analyze data from 108 children’s hospitals and surveys from thousands of pediatric specialists.

Four Ohio hospitals (Nationwide, Cincinnati Children’s, Cleveland Clinic Children’s and UH Rainbow Babies) ranked in the top 50 programs nationwide for all 11 pediatric specialties.

Cincinnati Children’s took the top spot for cancer, gastroenterology and GI surgery and pulmonology and lung surgery. Nationwide took fourth place in nephrology and gastroenterology

and GI surgery.

Cleveland Clinic Children’s ranked No. 9 for cardiology and heart surgery; No. 12 for neonatology; No. 17 for gastroenterology and GI surgery; No. 22 for orthopedics; No. 26 for diabetes and endocrinology; No. 28 for urology; No. 30 for neurology and neurosurgery; No. 31 for cancer; No. 39 for pulmonology and lung surgery and No. 43 for nephrology.

Meanwhile, UH Rainbow Babies & Children’s received No. 9 for neonatology; No. 12 for diabetes and endocrinology; No. 13 for orthopedics; No. 15 for pulmonology and lung surgery; No. 24 for urology; No. 30 for cancer; No. 30 for nephrology; No. 25 neurology and neurosurgery; No. 42 for gastroenterology and GI surgery and No. 42 for cardiology and heart surgery.

Akron Children’s Hospital ranked No. 20 for orthopedics; No. 38 for neurology; No. 43 for diabetes and endocrinology and No. 50 for neonatology.

By Judy Stringer for Crain’s Content Studio

Good customer relationships are never more important for a small business than during times of economic uncertainty or challenges like supply chain bottlenecks, escalating operational expenses and increased pricing pressure.

e same holds true in banking, according to Kurt Kappa, senior vice president and chief lending o cer at First Federal Lakewood. When banks and business owners develop deep and collaborative partnerships, companies are not only more likely to access favorable loan and credit products faster, but they also can leverage the nancial institution’s expertise and networks to weather economic storms.

And, Kappa said, no one does relationships better than community banks.

“Everyone says they’re a relationship banker,” he explained. “But that means di erent things to di erent banks. At bigger banks, their job is to bring deals in and move on to the next one. We bring deals in, and we nurture them, we grow with them, and we are their partner. at’s our relationship vision.”

Kappa joined First Federal Lakewood’s Commercial Lending Leader Scott Gnau in a Crain’s Content Studio Executive Roundtable recently to explore the essential role community banks play in supporting Northeast Ohio businesses. e conversation highlighted community banking’s personalized approach to lending and key factors small businesses should consider when choosing a banking partner.

Getting to

Personal relationships are a key di erentiator for community banks, the executives said.

“We want to know everything about the business that we possibly can, really starting from top down,” Gnau said. “Who the team is, who

the decisions makers are, what the operational needs are, what the capital needs are, where the business is trying to get to, and on and on.”

is customer-centric approach allows community banks to o er tailored nancial solutions that meet the unique needs of local founders and entrepreneurs, he said. It also positions them as trusted business advisors and coaches.

“We are meeting with them on a frequent basis to ensure everything is working properly as they continue to grow or helping to overcome any obstacles that spring up along the way,” Gnau said, noting that nancial advice, cash management solutions

“We

bank, First Federal Lakewood is owned by the depositors within its 20 Ohio-based branch communities, which, Kappa noted, creates a sense of ownership and a shared interest that fosters even stronger connections.

Not being beholden to investors also eliminates the “focus on quarterly dividends and stock prices and shortterm decision making,” according to Gnau.

“We’re always thinking about the long term,” he said. “O en that allows us to have a more competitive package to o er to a business owner, whether it’s through treasury management services or on the lending side. It just gives us repower and exibility.”

want to know everything about the business that we possibly can, really starting from top down ... who the team is, who the decisions makers are, what the operational needs are, what the capital needs are, and where the business is trying to get to.”

- Scott Gnau, Commercial Lending Leader, First Federal Lakewood

and help with things like business plan development are among the valuable resources community banks provide to their clients.

“We really want to pinpoint what keeps our clients up at night and then help them gure out how to solve that issue, or how we as a bank can provide contacts to potentially bene t the client,” he said.

e relationship tenor strikes a deeper tone with mutuality. As a mutual

at repower and exibility are on full display when accessing prompt funding is a make-or-break proposition – as it is for most startups and growing companies.

Gnau noted that certain banks like First Federal Lakewood have been designated Preferred Lenders by the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA), giving them the authority to make nal credit decisions locally

rather than waiting “weeks and weeks” for remote SBA loan o cers to review and approve applications.

Preferred Lenders have a history of e ciently processing and servicing SBA loans and have met the administration’s strict criteria for processing and knowledge of SBA policies. In addition to quicker servicing, Kappa said banks that have demonstrated such a high level of specialized expertise are acutely equipped to guide borrowers on speci c products such as the SBA 7(a) loan, which provides working capital to businesses with limited collateral, and 504s, which are designed for equipment and real estate purchases.

Selecting a community bank that is also an SBA Preferred Lender, the executive stressed, is a great way to get the bene t of both personalization and expertise.

“A lot of the big guys,” Kappa said, “don’t want to work on smaller deals” or might be afraid to take on an entrepreneur or an idea that is unproven, especially during these uncertain times when “many of them are tightening up their credit policies.”

“We don’t tend to have those issues because we know our customers, and we know what they’re doing and how they’re doing it,” he said. “It comes back to relationships and how we are truly here to help our customers grow so our communities can grow and thrive.”

To learn more about First Federal Lakewood’s community banking solutions, visit them online at FFL.bank.

The state has a record number of craft breweries, but closures are ticking up

Jeremy Nobile

After a long period of steady growth, the aches of a maturing market and a more challenging economic climate are contributing to some increased consolidation in Ohio’s craft beer industry.

“It’s tough out there, not trying to hide that,” said Shawn Adams, brewmaster and co-owner of Akronym Brewing. “And I think everyone is kind of going through the same things.”

After its debut brewpub in the Rubber City came online in the spring of 2018, Akronym opened a second taproom and full-service restaurant in summer 2022 in Medina.

For the rst year or so, business was solid. e beer, food and reviews were consistently good. And Adams believed the location bene ted from some pent-up demand as the world continued to emerge from the doldrums of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“But then it all just really slowed down,” Adams said. “Honestly, other than the economy, we really don’t know why. People are maybe tight on cash and don’t have a lot of free money to go out to dinner.”

While Adams declined to share details about nancials, he said sales are down “a lot” and costs are up across the board. Food, labor and beer ingredients are all signi cantly more expensive.

“And there is a limit to how much you can increase prices and still expect people to come,” he said.

As it tussles with these challenging dynamics, Akronym made the di cult decision to shutter its Medina outpost at the end of September after just two years of business. e craft brewery’s agship Akron brewpub remains open. And while Adams remains optimistic about the future, he frets about making ends meet until business picks up again.

“It’s tight. Everything is really tight. You’ve got to be really lean right now,” he said. “We are trying to make changes to (avoid closing entirely), but it’s rough out there for us.”

e brewery is looking at other ways to control costs and increase sales, including leaning further into self-distribution, though Adams said it’s challenging nding the time and people to support that.

Scores of craft brewers are grappling with the same challenges as Akronym that have been carrying on for quite some time now.

at includes Akron’s R. Shea Brewing Co., which shut down in March after several last-ditch efforts to keep a oat, and Pulpo Brewing Co., which closed its Willoughby taproom in September after four years of business.

Pulpo, which continues to operate its remaining brewpub in Crocker Park, chalked up its con-

solidation to part to higher brewing costs, while R. Shea was dealing with all these aforementioned challenges plus increased costs on debt as interest rates increased.

As of the end of September, there were 441 craft breweries in operation across the state, according to the Ohio Craft Brewers Association.

at continues to be a record number for the Buckeye State, where the population of breweries has been growing faster than the national average.

Ten years ago, Ohio counted 117 craft breweries — so compared with today, the state’s number of breweries has skyrocketed by 277%.

rough the last ve years (2019 to 2023), the state has seen a relatively consistent average of nearly 47 new brewery openings and 14 closures annually.

at includes 45 openings last year and 20 closings.

e rate of new openings seems to be slowing, however, and the pace of closures is ticking up. As of the end of September, there have been 31 brewery openings and 23 closures in the state, according to the OCBA.

e largest number of closings

in recent memory was 20 in 2023, so closures this year already have eclipsed that.

ese aren’t exactly dire numbers. But they do underscore the challenges in the industry today.

“It is unreasonable for people to expect that openings like we’ve seen, nearly 50 a year, continue and hardly any would close,” said OCBA Deputy Director Justin Hemminger. “ at is an unrealistic expectation for a maturing market.”

As far as what’s driving closures, he emphasized that there are some key themes, but no one driving issue.

“We are seeing a combination of factors leading to closures,” Hemminger said. “Some are over expansions or nancial leverage issues. And some are just people who want to retire.”

“It is a tough climate,” he added, “but we aren’t sounding alarm bells. is is literally what happens to any market that has seen the kind of growth craft beer has seen that comes into maturity and starts to level o .”

An expectation that craft brands may struggle in this environment could create M&A opportunities for companies like e Brew Kettle, which has been in the market for other craft brewers to add to its portfolio, like Akron’s Lock 15.

segment of adults — particularly younger imbibers —who are simply drinking less or opting for other beverage options, such as seltzers, ready-to-drink canned cocktails and non-alcoholic alternatives.

“While there are more craft beer consumers than ever before, what we are seeing in our consumer data is that craft drinkers are drinking craft less frequently than they have in years past,” Gacioch said. is trend has been inspiring established craft brands to either refresh their product portfolios with new o erings that appeal to ckle drinkers or regroup and focus on core brands.

Great Lakes Brewing Co. is doing a bit of both simultaneously in a bid to appeal to both older and younger consumer segments. “ ere was a time when a brewer could dictate what was going to happen,” said GLBC co-CEO Steven Pauwels. “ ose days are gone. If we can’t sell it, there’s no reason we should be making it.”

More regional craft businesses, such as Great Lakes Brewing Co. and Fat Head’s Brewery, may have the size, scale and volumes to o set these challenging economic and industry dynamics. But they’re still feeling the pinch.

Fat Head’s owner Matt Cole said his company is e ectively at today. And in a down market, he’s feeling pretty good about that. e brewery has been working particularly hard to control costs and improve e ciencies in this economic climate.

Nationwide, the volume of beer produced across the craft ecosystem dipped 1% last year, according to the Brewers Association.

Excluding an anomalous 2020 — when production declined due to the pandemic — 2023 marked the rst annual decline in craft production since the trade group began tracking this data in the mid-1980s.

Total beer production decreased last year by 5%, while 4.5% of all craft breweries in the U.S. closed.

Notably, the Midwest had the toughest year for craft production compared to all other regions with an annual decrease of 6%, according to BA economist Matt Gacioch. Production in Ohio was down 5%.

“It was suburban breweries nationwide that saw the best year in terms of production changes,” Gacioch said. “And for Ohio, that was actually rural areas.”

is underscores the general viability of the neighborhood taproom business model and the opportunity for breweries in lessfragmented areas to win market share.

But there are still the ongoing challenges of shifting consumer dynamics. is includes a growing

While the beer portfolio has been shrunk, the core focus remains on hop-forward IPAs that Fat Head’s has become known for — and which happen to be some of the most popular styles in Ohio. At the same time, he’s brewing fewer doubles and imperials, which are both more expensive to make and have higher price points.

“We even reduced pricing on some products to increase velocity and make it more a ordable for people,” Cole said, which shrinks the margin earned on those products.

Fat Head's and Akronym are on di erent ends of the craft spectrum. But they’re both optimistic about the future.

“Craft beer still has a great following as long as you can put a good, quality product out there at the right price point and get the right community behind it,” Cole said. “I still think that is a formula for success.”

But in an increasingly challenging and crowded craft market, winning those customers and maintaining a viable business is not an easy battle.

“People need to support local businesses and try to stay away from the chains,” Adams said. “Go out to dinner. Buy some beer from the local places that you like. If you don’t come out and support them, it’s going to be tough.”

Like many Clevelanders, I’m a die-hard Browns fan. Yet, my love for the Browns runs just a bit more personal than fandom. With family ties to the Browns — as my grandfather, Dr. Vic Ippolito, was the original team physician for the Browns — the Browns have been a staple in my family even before I was born.

And then I developed my own love for the Browns as I grew up. ere is no better feeling than watching the Browns run out of the gauntlet on Sundays, wearing the orange and browns, and the Cleveland faithful cheering and woo ng in unison for their favorite NFL team.

When I rst heard of the Browns’ potential move to Brook Park and the pitch for a domed stadium, I was skeptical of the idea of moving out of downtown Cleveland and away from the lakefront. All my memories as a Browns fan take place at what is now Huntington Bank Field, with the Cleveland skyline in the background.

As a member of the community, as well as a Browns fan, I evaluated both options about the future of the Browns stadium. I considered what was best for this passionate fan base, as well as our local residential, business and civic communities in Cleve-

land proper and the broader Northeast Ohio region.

And then, I visited Allegiant Stadium in Las Vegas for the Browns matchup against the Raiders. I was blown away by the rstclass amenities and what their stadium had to o er to fans. ere is an ease of entering and exiting the stadium with the tens of thousands of fans in attendance. e concourses o er all fans a premium experience throughout the building, including concessions and entertainment, with a stage for a live band that performed at halftime. e dome over the eld provided protection from the intense weather elements for a pleasant viewing experience of the game, while also amplifying the cheers of a stadium full of fans, including thousands of fellow Browns fans.

My experience at Allegiant Stadium made what I originally believed was a dicult decision an easy one for me — Brook Park would change the game in Cleveland and Northeast Ohio for the fans, the community and businesses. A new domed stadium will provide the opportunity for world-class amenities at Cleveland Browns games, massively improving the game entertainment and overall experience for fans.

e economic impact a new domed stadium would have in the city of Cleveland cannot be understated. From the numerous large acts that would have the opportunity to use a venue of its size, to the number of visitors outside of Ohio that they would attract, Cleveland needs a largescale, year-round venue to compete with other markets in the Northeast and Midwest. e development in Brook Park and the proposed entertainment district would be a transformational project for Northeast Ohio and o ers the opportunity to attract blue-chip companies to the area.

And the benefits of building a dome in Brook Park is only half the story — moving

At University Hospitals, we take our commitment to our community seriously and are grateful for your ongoing support in this rapidly changing world. Together, we’ll continue to treat patients like family, find new treatments and cures, and prepare the next generation of caregivers. Join others who are helping advance the science of health and the art of compassion by leaving their legacy.

To learn more, contact our Gift Planning Team: UHGiving.org/giftplanning | 216-983-2200

the stadium off the lakefront will unlock a massive opportunity for both the Northeast Ohio community and its economy to find a higher and better use for our prime waterfront real estate. Combined with the other great investments in downtown, this is a generational opportunity to transform our region, and I don’t want to see it go to waste.

Browns fans, we all want to see Cleveland succeed on the eld on gameday and push our region forward. We can do just that by supporting the e orts in Brook Park to make a new world-class domed stadium the long-term home for our favorite NFL team, the Cleveland Browns.

An algal bloom crisis in Toledo pushed Michigan and Ohio of cials, scientists and activists into action. Ten years later, progress hasn’t been easy. | Dan Shingler

It’s not easy being green.

at’s surely the case for our Lake Erie, where green (or blue) clouds blooming in the summer are telltale signs of algae that can and have threatened the lake’s health generally, and with it the 12 million or so people in the U.S. and Canada who rely on the lake for their water. at includes 17 cities with populations of more than 50,000, including Cleveland and Toledo, and smaller cities in Southeast Michigan like Monroe — but not Detroit, which is upstream and pulls water from the Detroit River or Lake St. Clair, which has algae issues similar to Lake Erie.

Ten years ago, about half a million of those people lost their water, when algae-produced toxins forced Toledo to tell residents it was not safe to drink for nearly three days. Suddenly

an entire city and its service area had no tap water to bathe, cook or run businesses. at was a shock. It shocked the city of Toledo, the region, the state and much of the nation. It woke people up to the vulnerabilities of the lake and our dependence on it to meet our basic needs.

Environmentalists and others hoped the Toledo algae water crisis would be a shock that ignited action, like the 1969 re on the Cuyahoga River. at now-legendary incident in Cleveland prompted creation of the federal Environmental Protection Agency.

But, while we had the will to keep rivers from catching re again back then, it remains to be seen if we have the will to keep a lake from becoming poisonous.

So far, say those studying Erie, we haven’t

exed enough muscle to live up to commitments made in the wake of the 2014 Toledo water crisis.

A year after Toledo’s infamous “do not drink order” went out, on June 15, 2015, the governors of Ohio and Michigan, along with the premier of Ontario, agreed to help the lake by cutting the phosphorous sent to it 40% by 2025.

Today, none of them is anywhere close to meeting that commitment.

“I haven’t seen any concrete numbers, but I have heard we’re about a quarter of the way there,” said Emily Kelly, agriculture and water coordinator for the Ohio Environmental Council, who is based in Port Clinton on the lake. Michigan is not meeting those goals, either; nor is Canada, say those who monitor the e orts to cut phosphorous.

A chief reason achieving the cut is so di cult, they say, is that the phosphorous is coming from what are known as non-point sources.

In other words, there’s not just a few factories and water treatment plants along any given stretch of coastline that is the problem — those have almost all been addressed, many decades ago after the U.S. EPA was formed.

Today’s phosphorous comes from the land itself and enters the lake via virtually every stream and river that feeds it, especially after a heavy rainfall washes more phosphorous o the land and into those waterways.

And that’s because phosphorous is the chief ingredient in fertilizer. So, the burden has largely fallen on farmers and the agricultural industry to change practices.

Many farmers have made e orts to better manage their fertilizer applications and participate in programs like the H2Ohio program or Michigan’s Lake Erie Domestic Action Plan.

But it hasn’t moved the needle enough for states to come close to meeting their goals.

“Our wastewater treatment plants have largely hit the 40% reduction they’ve promised; (agriculture) has not,” said Tim Boring,

director of the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development.

Not that his state hasn’t been trying. Boring said he and his department work hard to help farmers better monitor their elds and measure the phosphorous that’s on the ground before applying more.

“ is is what responsible farm management looks like, and we need to be doing more of it. at’s soil testing, following fertilizer rec-

ommendations, things like this,” Boring said.

But at the same time, farming and farms have been changing. Farms have become bigger to remain economically feasible. Many farmers have also engineered their elds with underground tiling that’s meant to help remove water. ose tiles enable farmers to access elds that might otherwise be too wet to farm during particularly rainy springs, but they also enable phosphorous to migrate from the

eld to the nearest stream or river and eventually the lake quicker than before.

“You quickly get into the dynamics of how we engineer farming today,” Boring said, “which a lot of times gets in the way.”

Ohio’s been working hard, too — and it has to, because of its outsized in uence on what goes from the Maumee River into Lake Erie’s Western Basin. at’s the lake’s hot spot for shing and recreation, and also where the shallow water

enables algae to produce large blooms and just-as-large problems.

“We’ve seen great engagement from the agricultural community. We’ve seen more than 2.2 million acres signed up and over 3,000 producers participate,” Ohio Agriculture Director Brian Baldridge said of the H2Ohio program. “In the Maumee watershed we’re seeing almost 50% of the acres” participate.

Most of the phosphorous washing off farmland comes in the form of commercial fertilizer, but these days a lot of it comes from manure, too, specifically pig manure. Many farmers have turned to raising pigs, often in addition to their crops, to make their farms profitable. The manure is used as fertilizer and spread on fields.

Since operations with more than 2,500 hogs require permits and are regulated by the state, a lot of farmers raise fewer than that at operations termed “minus-ones” because they can have as many as 2,499 hogs at once, but never 2,500.

e pig manure contains more nutrients than regular fertilizer, and is often far cheaper. “We’re putting about 25% on in the form of manure and the rest is commercial fertilizer,” Baldridge said.

ere’s controversy around whether such livestock operations, often dubbed Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations, or CAFOs, are having an outsized inuence on phosphorous in the lake.

Some environmentalists point to them as chief culprits in the algae problem. Manure is cheap or even free, they say, so farmers have little to no incentive to conserve it.

But Baldridge said the data he’s seen indicates otherwise.

“We track phosphorous sales. … We have seen a decrease in phosphorous purchases, so we know there is less phosphorous being purchased,” Baldridge said. “And we still think manure is only 25% of it.”

Some prominent lake scientists say they tend to agree with that, including omas Bridgeman, a professor of ecology at the University of Toledo and director of the Lake Erie Center. He’s as steeped in the water of Lake Erie as nearly anyone, say many who watch the lake closely.

“Some of the environmental groups want to blame everything on the animal operations. … I’m skeptical of that,” Bridgeman said. “Yes, CAFOs came in, but they were still in low numbers in the late 1990s and early 2000s. I don’t think there were enough CAFOs to have caused what we saw back then.”

But if it’s not from pig manure, where is all of this phosphorous still coming from if we’re reducing usage?

A big part of the problem is the complexity of the many systems at work. Farm elds, wetlands, streams, rivers and lakes are not test tubes and pipettes in laboratories. Water and the phosphorous in it ows through those natural features at unpredictable rates that are determined by the makeup of the soil, how many plants are growing in the soil, the topography, arti cial and natural barriers, whether there are wetlands and how good those wetlands are, and, last but not least, precipitation. When a molecule of phosphorous enters Lake Erie at the mouth of a river in the summer, it was probably applied to a eld that spring, experts say — but it also could have been applied the previous year, or many previous years earlier.

A really heavy rain, for example, might cause ponding or ooding in areas that haven’t been that wet in years. When that happens, phosphorous that’s been in that dirt for a long time can be dissolved, picked up and added to the lake and its problems.

But there are other reasons to believe the biggest contributor to an August algal bloom was fertilizer applied that spring, said Tom Zimnicki, agriculture and restoration policy director at the nonpro t Alliance for the Great Lakes in Chicago, which has eld o ces in Michigan and Ohio.

“You’re talking about legacy

phosphorous. Even if we stop adding phosphorous to this farm, so much is going to keep running o . at’s probably true to a certain extent. ere is legacy phosphorous,” Zimnicki said “But there was a year, 2018 to ’19, when the spring was so wet that farmers couldn’t get out to plant and fertilize … and that had an immediate e ect on the lake that same year.”

When it comes to reducing phosphorous, Baldridge and Ohio have some extra responsibility heaped on them due to geography. Not only does Ohio have a lot of coastline lled with farms on Lake Erie, but it also farms near the lake’s Western Basin, which is where most of the algae problems are caused and take e ect.

While the lake is fed in the west by the Maumee and Detroit rivers, it’s the Maumee that causes algae blooms, said UT’s Bridgeman.

“ e water coming in from the Maumee is only about 3% (of the lake’s water) but it contains about 50% of the nutrients,” Bridgeman said. “ e Maumee River has 10 to 20 times the concentration of nutrients as what the Detroit River has. If we could shut o the Maumee River, Lake Erie would not have a bloom. It would be clear, like (Lake) Huron is.”

at’s because, while the Detroit River is mostly carrying cleaner water from deeper upstream lakes, which typically don’t have algae or phosphorous issues, the Maumee is carrying water it gathered from hundreds of thousands of acres of Ohio farmland. Farmland in Michigan — mainly in Hillsdale and Lenawee counties — and in Indiana also is part of the Maumee watershed.

Ironically, that same land was what once protected Lake Erie and kept its water clean. Much of it used to be the Great Black Swamp, which was about 1,500 square miles of wetlands. Before it was drained and turned into farmland in the late 1800s, the swamp extended from Toledo to nearly Fort Wayne, Indiana, and made up the lake’s shoreline from Toledo to Catawba Island.

In other words, today our lake is essentially functioning with its kidneys removed, say environmentalists and lake scientists.

No 'silver bullet'

Now, Ohio is trying to replace those kidneys, at least in part, by developing new wetlands. H2Ohio has so far funded the creation of more than 180 new wetlands along the lake and drainage areas, the program reports.

But those don’t have near the size or scale that the Black Swamp had and will help but will not solve the problem, some say.

“It’s a tool. e problem is everyone thinks there’s a silver bullet for this problem in the lake, but there’s not,” said Chris Winslow, a sh biologist and director of the Ohio Sea Grant program at Ohio State University’s Stone Lab. “Some wetlands do a good job of absorbing nutrients, some do not.”

But they do help, he said, and Ohio o cials say they work hard to determine how to best design and build wetlands so they will slow the water and hold it long enough for plants in the wetlands to take up the phosphorous.

e costs keep rising, though.

Joy Mulinex, executive director of the Ohio Lake Erie Commission, which includes the directors of six state agencies, including Baldridge, said Ohio budgeted $270 million for H2Ohio in its 2023 biennial budget that expires next year. Previously, it put $172 million in the 2019 budget, and another $168 million in 2021, she said.

Mulinex’s commission is one of the partners in the state’s H2Ohio program as well.

ough Ohio is not on track to reduce its phosphorous as promised, Mulinex said improvements have been made and the state at least has not had any repeats of what Toledo went through.

“Lake Erie is a multi-use resource for the state. It provides drinking water for 2.8 million Ohioans. Since 2014 we have not had any additional problems providing drinking water for residents in Ohio,” she said, “so that’s certainly been a good step forward.”

But one reason that Toledo and other cities have been able to avoid a repeat of 2014 has little to do with the quality of the lake water they take in, and a lot to do with how such cities treat their water.

After 2014, Toledo spent more than $500 million upgrading water treatment facilities, adding ozone and carbon treatments and other methods to kill algae and remove toxins.

Buoys loaded with sensors alert operators of algae before it gets to the city’s water intake three miles o shore, so operators know what’s in the water and how to treat it.

Toledo commissioner of plant operations Andrew McClure said the city should be able to handle such an outbreak if it occurs again.

“We probably already have,” he said, noting that there have been big blooms since 2014 that the city handled with relative ease.

Toledo was already preparing for a top-to-bottom upgrade of the plant in 2014, said McClure and the plant’s chief operating o cer, Brian Loudenslager. So, it just needed more improvements and added processes than originally thought.

“ ere was already a plan to update just about every inch of the infrastructure we had here prior to the do-not-drink advisory of 2014,” Loudenslager said.

It did increase the costs, though. McClure said the city had been planning to spend $400 million for which it secured bond funding.

Fortunately, the state provided a low-interest loan to cover the extra $100 million, he said.

To be fair, 2014 was a rare conuence of many events that ended up causing Toledo’s problems. Heavy rainfall led to a large bloom of blue algae, which, unlike green algae, creates toxins in the form of cyanobacteria. (Green algae can still cause problems, like dead zones in the lake, however.)

Wind blew that algae past Toledo toward Cleveland, then the winds reversed and pushed it back to Toledo in higher concentrations. It was also the dreaded blue algae that produced the toxins, so many suspect the runo that year

also contained a lot of nitrogen, upon which such algae thrives.

But, until the lake is cleaned up further, rare events could happen again — possibly more easily as climate change warms the lake. Toledo needed to be ready long before that happened, and was, McClure said.

Since then, the city has become an adviser to others, with cities such as Akron and Erie, Pennsylvania, as well as states such as Oregon and Iowa, coming to Toledo to learn about methods to treat water impacted by algae and toxins. Other plants are gearing up to handle similar issues, on the lake and elsewhere.

But, like everyone else, what McClure and Loudenslager really hope to see is a cleaner Lake Erie. Just like farmers don’t want to use more fertilizer than they have to for good yields, water plants like Toledo’s would prefer to use fewer chemicals and processes to treat water.

Will it ever happen? ere’s not a lot of consensus, even among those who know the lake and its issues the best.

In Toledo, Bridgeman still has heart, and hope, but he’s been disappointed.

“Unfortunately, I’m probably less optimistic than I used to be,” Bridgeman said. “Following the Toledo water crisis of 2014 I thought, ‘Now people are going to pay attention and now something will happen.’ But it’s been 10 years and we haven’t made that much progress. … I think it’s going to take more than H2Ohio. I hate to say this, but it’s probably going to take more regulation on farming to force practices that will result in less nutrient runo ."

Erika Jensen, executive director of the Great Lakes Commission in Ann Arbor, is a bit more positive.

“I’m hopeful. I continue to see investment in this issue. Folks care a lot about Lake Erie and want to be good stewards of the environment while also supporting our farmers and the role that ag and food production plays in the region,” Jensen said. “ ere are a lot of smart people working on this issue. We’ve learned a lot, and I think if we continue on the path that we’re on we’ll see more progress.”

But perhaps the Ohio Environmental Council’s Emily Kelly has the best outlook, one shared by nearly everyone involved in the algae issue. To her, it’s not a matter of optimism or pessimism, it’s a matter of doing something or not.

“If we don’t do something now it really will be worse in the future as climate change continues and the lake warms. ey’ll just become larger. We’d see larger blooms now if we hadn’t taken measures,” Kelly said. “So, I have a lot of hope. I wouldn’t be in this line of work if I didn’t. Ohio really has made some great strides in addressing harmful algae blooms from point sources, but we have a lot more to do.”

Ohio succeeds when Lake Erie — its most treasured natural resource — succeeds. But as long as harmful algal blooms threaten our Great Lake, we will lag behind other states in providing our residents with safe drinking water, recreational opportunities and a strong economy.

toxic algae. While Toledoans should take great pride in their Great Lake, many to this day still avoid drinking their tap water.

Approximately 11 million people, including 3 million Ohioans, depend on Lake Erie for the water they consume each day. Lake-related activities contribute over 150,000 jobs to the state, many in tourism. In fact, more than 11 million tourists visit Ohio’s Great Lake annually, contributing over 30% of Ohio’s total tourism-related dollars, valued at $15 billion annually.

But each summer, we continue to brace ourselves for the severe impact of harmful algal blooms on Lake Erie’s Western Basin: Beach closures that drive away families and tourists. Canceled outings for anglers and kayakers. And concern about the quality and safety of Ohioans’ drinking water. is August marked the 10th anniversary of the Toledo water crisis, when half a million people lost access to clean drinking water for nearly three days due to

e Toledo water crisis was met with bold declarations of action by elected o cials and government agency leaders. In 2015, the governors of Ohio and Michigan, along with the premier of Ontario, made commitments to reduce phosphorus inputs to Lake Erie by 40% by 2025. Yet we failed to meet the interim targets set for 2020, and current data suggests that achieving the 2025 goal is unlikely.

In 2019, Gov. DeWine and the Ohio state Legislature established H2Ohio, a comprehensive water quality initiative aimed at tackling long-standing issues of water pollution — including harmful algal blooms. e Ohio Department of Agriculture plays a pivotal role in H2Ohio, leading e orts to reduce phosphorus runo by incentivizing farmers to adopt proven, science-based best management practices.

To date, 1.8 million acres of land have been enrolled in voluntary nutrient management plans. ese plans allow farmers to tailor conservation practices to

As we continue to witness the harmful e ects of phosphorus runo and algae blooms in Lake Erie, a pressing question emerges: How can we build a sustainable future that prioritizes environmental health and social justice?

e answer begins with the community — those who live alongside the lake, drink from its waters, depend on its health for their livelihoods and strive for a just and lasting peace.

e work of the Junction Coalition exempli es how grassroots, community-driven e orts can transform the environmental justice landscape. is transformation unites people, fosters dialogue and promotes active community engagement.

By empowering residents with the skills to take on these roles, we ensure that the solutions to environmental challenges come from within the community itself — creating a bottom-up approach to sustainability driven by the people.

maximize both agricultural productivity and environmental stewardship. Additionally, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources has invested over $130 million in creating or enhancing over 150 wetland projects, particularly in the Western Lake Erie Basin, to lter out harmful pollutants before they reach the lake.

We commend Gov. DeWine for the success of the H2Ohio program. Yet in order to match the scale of the problem and restore our great Lake Erie this decade, Ohio needs bolder investments, stronger wetland protections and more aggressive nonpoint pollution reduction strategies from our state leaders.

According to our recent report, co-authored with the Alliance for the Great Lakes, getting ahead of the problems will require signi cant, sustained additional funding along with major increases in conservation practice adoption (both by several orders of magnitude annually) and, in some cases, shifting the types of conservation practices. To do this, we must e ectively collaborate with stakeholders across agricultural, environmental and scienti c communities to ensure that we meet our goals to preserve Lake Erie for future generations.

Ohio thrives when Lake Erie thrives — and the health of our economy, our environment and Ohioans depends on it.

e Junction Coalition empowers residents to recognize that the best way to predict the future is to create it. When environmental crises arise, the Coalition serves as a unifying force, strengthening relationships between citizens, government and environmental agencies, while giving voice to those most a ected by Lake Erie’s contamination.

At the core of the Junction Coalition’s mission is a deep commitment to workforce development, which is essential to building environmental resilience and economic opportunity. By investing in the education and training of residents, we equip them with the skills needed to become active stewards of the environment. e Junction Coalition’s unique approach fosters both community ownership and responsibility while also creating pathways to employment in the expanding green sector.

The Junction Coalition’s work exemplifies the power of this approach. Through fostering community engagement, the Coalition has helped to build trust between residents and public officials, ensuring that decisions about Lake Erie’s future are made with the participation of those most affected. Their efforts have advanced environmental justice and contributed to holistic social and economic justice in the region — one grounded in collaboration, shared responsibility and mutual respect.

The Coalition’s bottom-up approach addresses the environmental crises we face as a unified community. Rather than imposing top-down solutions that often do not reflect the needs or realities of the people, the Junction Coalition demonstrates that true change happens when the community is empowered to lead.

By coming together, sharing knowledge and investing in one another, we can create a future in which both Lake Erie and the people who depend on it thrive.

By investing in the education and training of residents, we equip them with the skills needed to become active stewards of the environment.

Jobs in environmental services, water management, public utilities and ecological resilience are critical to maintaining a healthy Lake Erie. These roles provide tangible economic, health and environmental benefits, while also inspiring imagination and hope within the community. As we continue to embrace sustainable practices, these industries will be vital to both the preservation of our natural resources and the creation of a thriving regional economy.

As we look to that future, we must continue to prioritize workforce development and community engagement as central pillars of our efforts. The health of Lake Erie is not just an environmental issue; it is a matter of justice, equity, fair distribution of services and shared responsibility. By equipping residents with the skills and opportunities to become environmental stewards, we can build a sustainable and just future for all.

Through collaboration and a commitment to environmental and social justice, we can transform Lake Erie from a symbol of environmental crisis into an opportunity for growth, empowerment and peace. This is not merely about saving a lake; it is about saving a way of life. The Junction Coalition’s efforts are about ensuring that all people have the opportunity to thrive in a world where both the environment and the community are nurtured and protected.

As part of the warmest and shallowest Great Lake, the Western Basin of Lake Erie naturally has summer algal blooms. However, these blooms have been greatly exacerbated by nutrient loading from human activities and have become toxic. ese blooms are not only unsightly but can affect human and pet health because they are dominated by a kind of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) called Microcystis that make microcystin, which is a liver toxin, and sometimes include other blue-green algae that make neurotoxins that can a ect nerves. ese harmful algal blooms (HABs) create a surface scum that looks like spilled green paint, shading out organisms that live on the lake bottom and altering the ecology of the lake. HABs impair water quality of the lake — for example, during the 2014 Toledo water crisis, the city was without water for three days after toxins got into the drinking water supply, causing $68 million in damages, while impacting tourism, recreation, charter shing and home sales. HABs are estimated to cause about $50 million in economic damages in the U.S. each year.

e orts are beginning to pay o . HABs in western Lake Erie are largely driven by phosphorus and nitrogen loading from agricultural runo , particularly nutrient runo in the spring. e majority of the nutrient loading comes from fertilizer and the rest from legacy soil phosphorus and manure application. About half of the phosphorus and nitrogen load to the lake comes in through the Maumee River, from its watershed in Ohio, Michigan and Indiana. In 2015, Ohio, Michigan and Ontario signed the Western Lake Erie Basin Collaborative Agreement, in which they agreed to a 40% reduction in the phosphorus load to the lake by 2025.

In Ohio, Gov. DeWine signed a statewide plan, H2Ohio, into law, which supports farmers in implementing nutrient management practices and funds wetland restoration e orts. Farmers receive economic incentives to implement best management practices, including developing voluntary nutrient management plans, twostage ditches, drainage water management, subsurface phosphorus placement, and other measures.

o through a natural ltering process, reduce ood risks, and provide wildlife habitat. ODNR has funded 171 wetlands to date. Likely due to these management practices, spring nutrient loads in the Maumee River appear to be declining. Michigan largely contributes to nutrient pollution in western Lake Erie through wastewater treatment plants in the Detroit area and through agricultural runo in the River Raisin watershed. Michigan already has achieved signi cant reductions in wastewater inputs through optimization actions and upgrades.

However, monitoring by the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) and the National Center for Water Quality Research at Heidelberg University (Ohio) shows that critical spring nutrient loading in the River Raisin appears to be increasing, as opposed to the decrease in the Maumee River, highlighting the need to implement best management practices in agriculture in Michigan.

ganizations, including the Michigan Quality of Life (QOL) Agencies, which include the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (MDARD), EGLE, and the Department of Natural Resources, have partnered to implement Michigan’s Domestic Action Plan and adaptive management e orts in the western Lake Erie watershed. eir goal is to achieve the nutrient reduction goals set by the 2012 Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement.

Current priority e orts include the work of QOL agencies, such as MDARD’s partnership with the Alliance for the Great Lakes and others to increase water quality monitoring and modeling e orts. e goal of the monitoring is to better understand how nutrients ow through these watersheds so that we know where to focus our e orts with projects like regenerative agriculture and best management practices that build soil health and protect water quality.

complete eld-scale agriculture inventories that can assist with onfarm decision-making. DNR is focusing on protecting, restoring, and creating wetlands that capture agriculture runo and provide important ecosystem services, including enhancing wildlife habitat and recreation opportunities in Michigan’s portion of the western Lake Erie watershed.

Taken together, the combined state e orts from Ohio and Michigan are a solid foundation on which to build future e orts to resolve the growing issue of HABs in Lake Erie. Getting increased farmer participation to implement best management practices in priority subwatersheds is now the key to moving forward and continuing to make progress.

Fortunately, over the past decade, we have taken action to reduce these inputs that cause harmful algal blooms, and these

e Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) funds restoration and creation of wetlands (as the entire watershed used to be a swamp) to reduce nutrient run-

In Michigan, the focus is on monitoring and implementing best management practices to begin to bring down agriculture's contribution to HABs. Several or-

In addition, EGLE’s nonpoint source program is providing technical and nancial assistance for watershed management planning and implementation, and is working in partnership with western basin Conservation Districts to

A recent study completed by University of Michigan graduate students showed that this progress can be made by focusing on changing culture and personal attitudes combined with making government programs easier to access and better funded. Although it will take time to reduce Lake Erie’s HABs back to small, nuisance blooms, early results from new management practices are showing promising trends.

August marked the 10th anniversary of when residents of Toledo awoke to urgent warnings not to drink or use their tap water because of toxins from Lake Erie’s harmful algal bloom. is year the bloom peaked at over 600 square miles with toxins present throughout the summer season.

Tom Zimnicki is agriculture and restoration policy director for the Alliance for

While Ohio is unlikely to see another drinking water emergency like in 2014 — due to increased testing and monitoring requirements — algal blooms will persist into the foreseeable future.

the Great Lakes.

Algal blooms are not just an aesthetic issue — these blooms have real human health and economic impacts, costing the Lake Erie economy over $270 million a year, according to a 2019 study. Our

own analysis at the Alliance for the Great Lakes showed that a family of ve in Toledo is paying roughly an additional $100/year on their drinking water bill just to monitor and treat drinking water for harmful algal blooms.

To combat these blooms, both Ohio and Michigan committed to reducing phosphorus — the main driver of bloom formation — 40% by 2025, a goal that neither state will meet. Michigan has made considerable progress in reducing phosphorus from wastewater treatment plants — cutting phosphorus from Detroit’s Great Lakes Water Authority by over 400 metric tons per year.

However, both states have largely failed to deliver quanti able re-

ductions from agricultural sources, the dominant land use in the Western Basin of Lake Erie watershed.

After years of work and hundreds of millions in taxpayer funds spent, the traditional approach of incentivizing voluntary best practices to reduce agricultural phosphorus entering Lake Erie has largely failed. Our research at the Alliance shows that farm conservation practices in Ohio and Michigan are woefully underfunded. Despite years of investment, the adoption rate of those practices is still far behind where it needs to be.

Moreover, Ohio and Michigan are nowhere near the scale of conservation practices needed across the Western Basin of Lake Erie to meet the 40% reduction targets using only the traditional, voluntary incentives they are currently employing.

We may never get a complete handle on agricultural phosphorus entering Lake Erie — or any

waterbody across the country — under current state and federal regulatory schemes, but there are ways to improve existing programs aimed at reducing agricultural pollution sources.

Launched in 2019, the H2Ohio program is the largest state funding source for reducing agricultural runo to Lake Erie. While this program has already invested hundreds of millions of dollars, we know that it is only a fraction of what is needed.

A long-term funding option must be established instead of relying on the biennial budget process that is subject to political whims and disputes. Future funding must also include greater accountability and transparency to ensure that the money spent on reducing agricultural pollution is leading to actual quanti able reductions of phosphorus. Comparable e orts across the Great Lakes

Basin must fund real outcomes.

If we are going to continue to use taxpayer dollars aimed at improving water quality, taxpayers need to feel con dent that progress is being made.

Algal blooms are becoming more pervasive across the Great Lakes Basin as pollution persists and climate change creates more favorable conditions for bloom formation. Increasing accountability, funding quanti able water quality improvements and targeting investments at highest priority areas are measures that all states in the Great Lakes Basin can and must take to address this problem. As water resource pressures build across the region and country, it is imperative to remember that our access to the Great Lakes, the world’s largest freshwater system, is only as useful as our ability to protect its quality for current and future generations.

Lake Erie has a bad reputation, dating back at least as far as Time magazine declaring it “dead” in 1970 and running a photo of a re on the surface of the Cuyahoga River. While “dead” is not a scienti cally accurate term, and the photo was actually from the 1950s, there is no doubt that the region’s industrial, commercial, agricultural and residential booms over the past two centuries left contamination that we are still cleaning up today and polluted the lake with excess nutrients that lead to massive algae blooms.

More than aesthetic concern, some species of algae in the blooms produce toxins that threaten humans, pets and wildlife. Each summer, the Lake Erie bloom makes regional and national headlines that reinforce the image that the lake is losing the battle. Fortunately, the reality is that, while signi cant problems remain, we have begun to turn the tide toward more e ective management of the issue.

Recurrent blooms in western Lake Erie motivated management strategy and investment at bina-

Casey M. Godwin works at the University of Michigan and the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research.

Mike Shriberg is with the University of Michigan, the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research and also Michigan Sea Grant.

tional, national, state and local levels. ose investments have enabled monitoring and safeguarding against threats posed by the blooms, including by NOAA, the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research (CIGLR) and the University of Michigan. Monitoring systems — from “smart buoys” to satellites — provide up-to-date, actionable information directly to water intakes and others reliant upon

the lake. We are seeing measured progress toward decreased nutrient inputs to the bloom-prone areas, but all indications are that we are unlikely to achieve the goals of decreasing phosphorus pollution by 40% by 2025, as originally planned.

Slow change in the watershed is compounded by interannual variability in weather and precipitation that alters how the lake responds to nutrients. Focusing narratives on year-to-year patterns — this was a bad year or a good year — confuses management e ectiveness with everything else we know, and don’t know, a ects the bloom.

While monitoring has improved greatly since the 2014 crisis in Toledo, and new programs are in place in Ohio, Michigan and Ontario to reduce the nutrients from agriculture that are the primary cause of the severity of the annual blooms, much of the changes being sought are behavioral, and thus take time to implement. For example, research on farmer behavior has shown that decreasing nutrient runo requires not only increased upfront costs for equipment and management practice changes, but also changes in cul-

ture and action that only come over time and from peer-to-peer knowledge transfer.

Change on nutrients and blooms has proven slow to develop, but there is progress and now is the time to accelerate our actions, not to take our eyes o the road ahead.

We must take a longer view by planning for and modeling the conditions coming decades from now. Tools and quantitative predictions guiding management to present were based on recent historical patterns of land use, climate, and precipitation, but this

leaves us critically underprepared as climate change rapidly transforms regional demographics, agricultural practices, and the lake itself. Future nutrients will not ow into Lake Erie of the past, so a long-view approach requires developing models of a lake and landscape that function di erently from what we have experienced. at may seem too daunting a task given the multitude of problems facing the lake, but it is essential if we are to achieve the long-term restoration outcomes the region demands.

By Kim Palmer

Cleveland Mayor Justin Bibb’s administration is preparing for the next and, arguably, most critical step in realizing the city's massive re-development of the downtown lakefront.

e preliminary step to create a New Community Authority (NCA), the rst inside Cleveland borders, passed city council late last month and is set for a November public hearing.

The NCA, the administration contends, is the best economic development tool to finance and operate the large-scale, infrastructure-heavy buildout of the underdeveloped lakefront.

“NCAs are new to Cleveland but not Ohio or Cuyahoga County,” said Jessica Trivisonno, senior adviser of major projects in the mayor’s o ce. “ ey are created to support public infrastructure projects because the NCA can, among other things, assess charges or fees on retail, hotel and property valuation within a set geographic area.”

If it passes, the NCA — known o cially as the North Coast Waterfront New Community Authority — will join the acronym-laden list of organizations, including the North Coast Waterfront Development Corporation (or NCWDC), charged with guiding the downtown lakefront development plan.

e real bene t of using an authority to assemble funding for the North Coast Waterfront Master Plan, Trivisonno points out, is the exibility the quasi-governmental agency has to tap into various -

nancing sources.

“A big bene t is that NCA charges are structured in a way that they can be nanced against, so the authority’s board can go out and get bonds immediately and use the future revenue to repay those bonds,” Trivisonno said. ere are currently about 55 NCAs across the state. e Columbus-Franklin County Finance Authority has helpednance more than $4.5 billion in public improvement and mixeduse property development in and around that city since 2006.

Cleveland’s waterfront NCA will be less expansive and more closely resemble Cincinnati’s Banks NCA, created for publicprivate development of 120 acres of central riverfront property along the Ohio River.

at NCA assesses a 1% amenity fee on food and beverage purchases made around the stadium district, generating about $500,000 annually now used for marketing and administrative costs.

Unlike other special tax and fee collection schemes — like Special Improvement Districts and Tax Increments Funding Districts — property owners and businesses must opt into participating, and each nancial agreement is separately negotiated.

An NCA allows exibility on fees which can be based on revenues from parking, food and beverage to added property tax.

“ e NCA allows property own-

ers to buy into the redevelopment and the improvement of the area,” Trivisonno explains. “ ere is no other mechanism in Ohio where you can make these types of sitespeci c charges. e city can't just add hotel charge in a speci c area, city council doesn't have that authority, but the NCA does."

All the additional charges, per Ohio law, must abide by the maximums laid out in the city’s legislation and be disclosed to the public. For example, a restaurant or hotel receipt will include a message about a 1% NCA charge.

If the measure passes council, the NCA could add these maximum costs: $5 per vehicle parking fee; $2 charge on admission or ticket; 5% on gross receipts (retail, food and beverage and/or tickets); 10% charge on hotel and 10 mils on the assessed value of a property.

“It's not something that can be changed afterward,” Trivisonno said. “ e maximums on the charges need to be spelled out however the actual charges are worked out in a separate agreement between the NCA and the entity being charged.”

e uses of any revenue collected by the authority, including revenue from the bonds that the NCA can issue for the project, must also be spelled out during the creation of the authority.

Revenue from the waterfront authority, according to the NCA ordinance, is eligible to be used for public infrastructure, including the creation of a land bridge, acquisition and utility work to support development activity,

parks, streetscape, multi-use paths, parking facilities, landscaping, and other improvements.

Public art, public space management and programing, shared services and NCA operation costs are also eligible, Trivisonno added.

Another unique feature of the NCA is that although the authority is de ned by geography, it does not necessarily need to be contiguous and properties can be added over time. An NCA also is separate from — and can exist alongside of — tax increment nancing and special improvement districts.

e eventual goal, according to Scott Skinner, executive director, NCWDC, is to include the lakefront spanning from Browns' stadium on the west to the end of Burke Lakefront Airport on the east.

e initial waterfront NCA boundaries, Skinner said, will begin with a portion of the eventual borders due to the complexities of negotiating di erences between landand submerged-land leases.

“ e parking lot land north of the stadium, Voinovich Park, Burke Lakefront airport parking, the Muni lots and Willard parking garage will be part of the initial footprint we're forming as part of the waterfront NCA,” Skinner said.

After the initial NCA boundaries are secured, two more phases will

be added in “quick succession” to include Huntington Bank Field, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the Great Lakes Science Center and the rest of Burke Airport.

e NCWDC non-pro t created by city council more than a year ago and led by Skinner will, if the legislation passes, act as the NCA’s administrative arm. e NCWDC will negotiate the individual fee and charge agreements with the lakefront private partners and collect on those agreements.

e nonpro t will not determine how any revenue or funding that stems from the issuance of bonds is spent, that responsibility lies with the NCA board of directors. State law dictates NCAs have at least seven members and the majority of waterfront authority board seats would be appointed by city council. Skinner said Cleveland’s board seats are designed to bring in a combination of expertise in development and nance and represent the wants of the city’s residents.

“ ree of the board members appointed by city council are there to represent the interests of present and future residents and business owners. One seat appointed by city council is there to represent local government and then three appointed by the developer (which in this case is the city of Cleveland) to represent the developer's interests,” Skinner said.

e Cleveland waterfront NCA ordinance is set to go before the city council in a public hearing on Nov. 12.

Soon after founding the business in 2009, Lix moved his small distillery to a Manufacturing Advocacy and Growth Network (MAGNET) facility in the city.

As the operation began to outgrow its modest workspace there, an expansion was set in motion.

In 2020, Lix disclosed plans to become an anchor tenant at a development marketed by CRESCO Real Estate as the Flats South Innovation District, a haggard industrial area along the Cuyahoga River that’s long been surrounded by decaying roads, dilapidated warehouses and piles of coal.