21 minute read

Black migrants see nothing in Tapachula but racism and a dead end

By Shahid Meighan July 27, 2022

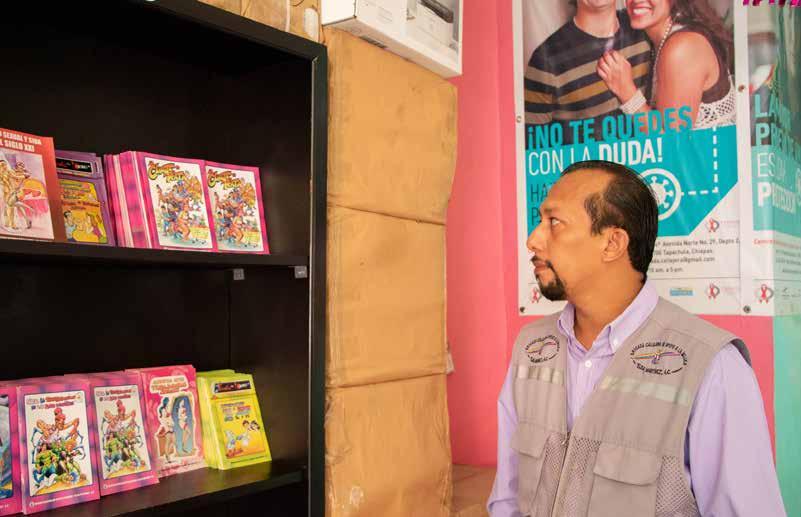

TAPACHULA, Mexico – The wide street leading to the Instituto Nacional de Migración is lined with bright and bold murals affirming the human rights of all people without regard to their country of origin.

However, many of the hundreds of Black migrants from Africa and Haiti who daily wait outside the office of INM say immigration officials, and the Mexican government in general, have failed to live up to those words.

Migrants from across the globe can be seen on this street, clutching folders with immigration documents, hoping to expedite appointments with INM that are scheduled six to eight months out.

Without proper documentation from Mexico, they’re stuck in Tapachula, more than 1,200 miles south of their U.S. destinations.

But particularly among Black migrants, the tension, anxiety, frustration and, in a growing number of cases, anger, are the only things more palpable and intense than the humid heat. They believe that their applications for humanitarian visas or asylum, which would potentially allow them to pass through Mexico or find legal work and assistance, are being delayed because of the color of their skin.

Because of these delays, many migrants and their families sleep in parks near the INM building or just outside it, hoping to save their place in line for a chance to make their cases to immigration authorities.

“We are suffering here! We don’t have no money, we sleep out in the street!” said Sidike Kamora, 17, a migrant from Liberia among the throng waiting outside the INM office one afternoon.

“They only take white people,” he said. “I don’t know why Black people suffer everywhere, when you go inside you only see White people. It’s not fair.”

In 2019 and ’20, Mexican authorities detained more than 10,000 African and Haitian migrants passing through Tapachula on their way north, according to a report by the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan organization that conducts research and analyses regarding world migration and provides insight into migration policies for countries around the world.

Migrants from Cameroon, Congo, Eritrea and other parts of Africa are fleeing violence, political instability and persecution. Haitians have left their island nation – already the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere – in waves since an enormous earthquake in 2010 that killed more than 200,000 people. After another earthquake in 2018 and the assassination of Haiti’s president last year, Haiti has descended into chaos, where kidnappings are common and local gangs, vying for territory and power, shoot it out in the streets.

Before 2019, most migrants entering Mexico through its southern border were detained and issued an exit permit requiring them to leave the country within 20 to 30 days. However, in the summer of 2019, then-U.S. President Donald Trump threatened Mexico with stiff economic tariffs if the country did not take serious action to halt migration into the United States.

In response, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador deployed the Mexican national guard to enforce what has been referred to as an ad-hoc immigration policy that essentially uses Tapachula as a holding bay, thereby preventing migrants from continuing north.

The Biden administration has attempted to reverse some Trump era policies that kept migrants stalled in Mexico, and in June the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Biden can stop the Migrant Protection Protocols, known as the “Remain in Mexico” program, but it’s not clear what immediate effect the ruling will have for migrants now stuck in Mexico.

Although all migrants in Tapachula have been affected, Black migrants say they face additional hurdles: racism and xenophobia.

Their claims are supported in an October 2021 report by the Migration Policy Institute. “African

Migration Through the Americas” found that African migrants face unique challenges compared with migrants from Latin America.

“African migrants face myriad difficulties rooted in differences between their nationalities, languages spoken, religions practiced and their race and ethnicity and those of the societies through which they travel,” the report said. “Racism, a lack of interpretation and translation services, and a lack of understanding of cultural and individual practices make transit and longer term settlement particularly difficult for African migrants in the Americas.”

Lawyers and human rights activists who are on the ground in Tapachula say immigration officials prioritize migrants from Spanish speaking countries. Black migrants complain they’re routinely targeted by police and immigration officials during nighttime roundups of unauthorized immigrants, leaving them terrified to go out after dark. When tensions build and the migrants protest this treatment, they are accused of being violent. Dozens of protests and demonstrations have broken out in Tapachula, and videos show the Mexican national guard using force against mostly Black migrants.

“They don’t care about Black people,” said Frantz Joseph, a migrant from Haiti who now works for the Haitian Bridge Alliance, an advocacy group that provides services to Haitian migrants in Tapachula. “I don’t understand what’s going on, but there’s no privilege for Black people here.”

Current and former government officials in Tapachula defended the government’s treatment of Black migrants. They said the system is simply overwhelmed and lacks resources, including translators who can help those who don’t speak Spanish.

Last November, the Mexican government held a conference on the mistreatment of migrants, sponsored by Mexico’s commission for refugee assistance (known by its Spanish acronym COMAR), in which it denounced racism and xenophobia aimed at migrants.

“People in transit have historically faced prejudices and stigmas that have caused the normalization of false beliefs that are an attempt to justify them receiving unequal treatment and injustice,” the commission said in a news release. “Their vulnerable situation increases because of the language and attitudes of xenophobia that they experience in this country.”

The news release said the government is committed to eradicating stereotypes, prejudices and stigmas against migrants – through training and education.

In mid-July, COMAR responded to Cronkite News’ request for comment.

“On the part of COMAR, there is no difference in treatment for those seeking access to the refugee recognition process,” COMAR official Cinthia Perez Trejo said in an email. “Their reception and attention is the same according to the law, which determines for us what actions must be carried out in order to process a case. Aside from that, if there is any indication of something that could be interpreted as discriminatory treatment, there are procedures within the office of the Secretary of Governance of Mexico for sanctioning any public official who commits such acts.”

Disparate treatment reported

“The process is fast for Central American migrants. They are seen within two or three weeks. But for Haitian migrants, it’s slower,” said Melus Morvensky, a Haitian migrant who arrived in Tapachula with his family on Sept. 15, 2021.

Morvensky sits on a bench opposite his family, looking at the park behind him and just trying to pass the time. His daughter, 2½, prances around as her mother makes sure she doesn’t wander too far from the group.

“She’s been sick with diarrhea, and a fever,” said Morvensky, gazing at the girl with concern. He couldn’t afford the doctor’s visit plus the medication she needed.

Morvensky, along with his wife and two children, left Haiti because of political and economic strife. Their first stop was Chile, where they lived for about five years before leaving because work was hard to find and neither he nor his wife had the necessary work permits.

“If you don’t have residency in Chile, you don’t have work, you have nothing,” he said. They decided to try their luck by traveling to Tapachula, with the goal of eventually settling down in the United States.

However, like the tens of thousands of other migrants stuck in Tapachula, Morvensky discovered the immigration process was slower and more complicated than he expected. By early March 2022, he had been waiting five months for his first appointment with COMAR.

This isn’t the first time immigration authorities in Tapachula have been accused of favoring migrants who speak Spanish. Black migrants repeatedly claim that immigration authorities, notably the INM, will confiscate or destroy their immigration documents alleging they’re fake. In more extreme cases, Haitian migrants say, they are threatened with deportation to Guatemala or physically assaulted by the national guard. Others are pressured to pay money to these authorities or run the risk of being arrested and even deported. Although some of these claims are shocking, historians and civil rights advocates say Mexico has a long history of racism toward Black people.

Slavery and Afro-Mexicans

According to Colin Palmer, author of “Slaves of the White God,” which examines the history of Blacks in Mexico from the 1500s, Africans initially were brought to colonial Mexico as slave labor to replace Indigenous laborers, who had been decimated by smallpox, diphtheria, measles and other European diseases unknown in the New World.

“The introduction of African slaves into Mexico was in part a response to the labor shortage stemming from the decline of the Indigenous population during the 16th century,” Palmer wrote. “Spanish mistreatment of the Indians and a number of disastrous epidemics contributed to this demographic catastrophe.”

Although Mexico formally outlawed slavery in 1837, the Spaniards left behind a legal caste system that put Africans and their descendants at the bottom of society. (Graphic by Hector Adames, Associate Department Chair at the Chicago School of Professional Psychology)

As the Indigenous population continued to plummet, the Spanish increasingly needed a new labor source to work in its silver mines and sugar cane plantations. To solve the labor shortage, the Bishop of Chiapas, Bartolome de las Casas, a Spaniard known for his opposition to enslaving Indigenous people, suggested importing Africans. In 1521, the first

African slaves touched the coast of Mexico in what today is the state of Veracruz. According to Origins, a website created by historians at Ohio State University, the prevalent belief at the time was that Africans were hardier and less susceptible to disease and death.

Data from SlaveVoyages, a collaborative website that logged the transatlantic and intraAmerican slave voyages dating from the 14th century, at least 153,000 Africans were imported into what was then called New Spain, which at its peak covered all of Mexico, Central America and the Isthmus of Panama.

Slavery in Mexico formally was outlawed in 1837, 16 years after Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821. But even with the abolition of slavery, the Spanish left behind a legalized racial caste system, a hierarchy determined by familial ancestry, according to a 2009 article by Herbert G. Ruffin, an associate professor of African

American studies at Syracuse University. At the bottom of this hierarchy were African slaves and their descendants. By law, Africans were barred from holding many positions within Mexican society and generally held no power or standing, the article states.

In many ways, the remnants of that caste system still are evident in Mexico. For example, Black Mexicans, who now mostly live in the coastal states of Veracruz, Oaxaca and Guerrero, finally were able to self-identify as AfroMexican in the 2015 intercensal survey and the 2020 national census, but only after repeatedly petitioning the government. In 2019, the Mexican constitution was amended to officially recognize AfroMexicans. However, even with these advancements, Afro-Mexicans still must deal with racial discrimination. In a 2014 study published in the Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, a quarter of Mexicans said they would not rent to a person of African descent, and darker skin overall often is associated with a lower quality of life in Mexico.

“It’s very difficult,” Morvensky said through a Spanish translator. “I can’t spend too much time thinking about (discrimination). The most important thing is how we can survive here.

How do we buy food? Pay rent?”

Morvensky said he briefly worked as a vendor at a supermarket, but he was paid only 150 pesos a day –equivalent to $7 – which is Mexico’s minimum wage.

Seeing no hope for a future where he can provide for his family in Tapachula, Morvensky still is waiting for his appointment with COMAR to receive the documentation to move to other states in Mexico in order to find work.

Finding work, however, may be the least of Morvensky worries. He must also hope that neither he or any of his family members are arrested by Mexico’s immigration authorities and taken to any one of Tapachula’s numerous detention facilities.

Siglo XXI

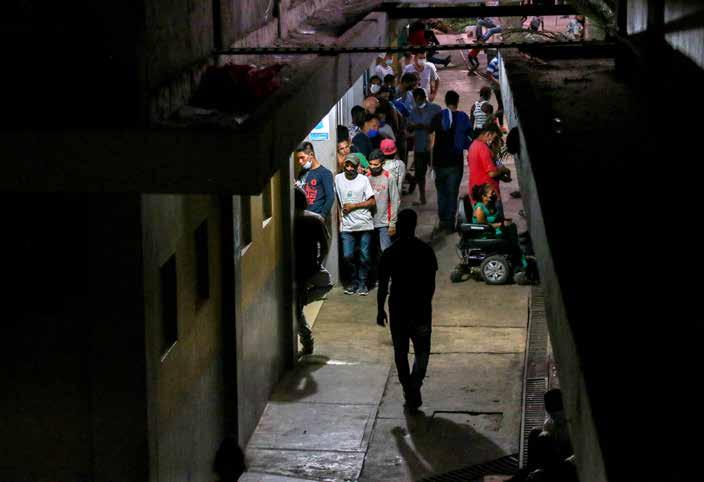

The city’s main migrant detention facility, Tapachula Estacion Migratoria, known locally as Siglo XXI (Spanish for “21st century”), sits off a narrow road surrounded by grass and brick walls. At its front doors, people pace anxiously back and forth, waiting to hear about the condition of friends and loved ones inside.

According to the Global Detention Project, a nonprofit that promotes the human rights of those who have been detained for reasons pertaining to their immigration status, Siglo XXI has a standard capacity of 960 detainees. However, multiple reports, including from the Migration Policy Institute and several news networks, have reported that the facility faces severe overcrowding and flea infestations.

A report by the project in February 2021 also lists instances of discrimination experienced by Black immigrants in detention facilities in Mexico.

“In Mexico, for example, Africans have experienced worse detention conditions than other migrants and are more easily targeted for extortion,” the report states. In more serious cases, it says, African migrants are regularly denied food until all migrants from Spanish speaking countries have eaten first.

In a separate report, conducted by researchers for the Black Alliance for Just Immigration, Black migrants were told that detention was necessary for the regularization of immigration status in Mexico, but “this isn’t the case” for non-Black migrants. Black migrants also tell of denial of water and medical care and general abuse from jail officials.

“Black people are dying in detention and the Mexican officials do not even care enough to allow us access to proper medical care” the report quoted one detainee.

Naseri Loderick, an immigration and human rights attorney in Tapachula whose work has focused on getting migrants released from Siglo and other lockups, said the facilities regularly violate international law and human rights. He contends that migrants should not be arrested solely because of their immigration status.

“On which grounds are you detaining someone for an ordinary paper he does not have?” he asked while standing outside Siglo XXI. “You cannot detain someone that doesn’t have any papers because at the end of the day, migration is a civil issue, not a criminal one. Nobody should be punished for not having an ID card.”

Loderick recounted some of the complaints he hears from clients and other migrants at Siglo.

“Every time I talk to a client,” he said, “I ask them three important questions: Have you eaten, have you been able to contact your consulate in your home country, and have they informed you of your rights as a migrant? The answer to all of these is always no.”

Loderick said detention officers often help Central American migrants fill out paperwork and explain it to them, but that courtesy is not offered to Black migrants, who may not fully understand the process because of language barriers.

“They will take the time to teach Central American migrants about the process, and they will tell them to do it and to do it now,” Loderick said.

Asked about his personal experience with racism in Tapachula, he became emotional.

“Because I’m a Black man myself … they don’t even respect me,” he said. “So you can imagine a migrant who doesn’t even speak Spanish, who doesn’t even know his rights.”

Loderick said serious international intervention is needed, and soon, before the situation gets worse.

“I am calling on the entire international community, the European Union, the United Nations, African Union, because it really is an issue,” he said. “People die. People lose their lives for a simple reason that we have the solution to.”

Pressure rising

The Cronkite News Borderlands Project witnessed multiple protests while in Tapachula in March, including one that turned violent. Black migrants set fires in the streets, threw rocks at police and national guard. They held their hands crossed over their heads, symbolizing the breaking of chains. Protesters said they desperately wanted to leave Tapachula so they could provide for their families.

Earlier in the year, one of the INM offices in Tapachula was temporarily shut down because of a skirmish that broke out in which some INM employees were injured. The office has since reopened for operations.

Andrew Bahena, a researcher for the Coalition for Human Immigrant Rights, or CHIRLA, a Los Angeles organization that advocates for immigrant rights, gave some insight behind the protests.

“The protests are always about the tramites (formalities), the bureaucratic processes not working, and people always protesting the length of time that they need to wait to go through the process,” Bahena said. “That’s what it’s always about, how bad the conditions are here in Tapachula and the fact that some people just don’t want to be here.”

And when it comes to Black migrants in particular, Bahena said, the blowback for protesting these conditions is swift and harsh. Black migrants are “proven leaders” in these movements and demonstrations, he said, and as a result have suffered disproportionate violence at the hands of Mexican authorities or migration officials.

“There’s like this hierarchy of migrants. The good migrants are the Guatemelans and the Cubans,” Bahena said. “But then you get to the Black migrants and it’s immediate hostility. And then when you take into context that they’ve been there for a while and they start to demand better treatment. Like, if you’re already starting from super hostile, just imagine how quickly that escalates.”

And it has escalated. Countless videos showcasing clashes between migrants and the national guard have gone viral, even after President Lopez Obrador promised a more humanitarian approach toward migrants in Tapachula.

African migrants, recognizing that they have no one to rely on but themselves, at one point in 2019 created an ad-hoc group to mobilize and address their treatment at the hands of authorities in Tapachula. The Assembly of African Migrants released a list of accusations and demands against the Mexican government. The accusations ranged from rampant racism and extortion at the hands of state forces to outright violations of human rights and cases of repression by the national guard and immigration authorities. Their demands included urgent humanitarian aid to Black migrants, free and safe passage to other states in Mexico or to the United States and Canada, and international protection for those who choose to stay in Mexico.

Despite the group’s list of strongly worded grievances, not much has changed in Tapachula. The Assembly of African Migrants no longer is active. African and Haitian migrants continue to stick together in enclaves around the city, pooling resources to survive as they anxiously await the day they can leave Tapachula.

In mid July, UNHCR, the United Nations agency for refugees, said it was taking steps to improve conditions for Haitian migrants in Tapachula, including providing

Creole translators to COMAR and helping COMAR expedite appointments.

Although the situation looks bleak, some migrants, like Djiby Samb from Senegal, vow to maintain hope and a vision for a future beyond Tapachula.

“There’s nothing else we can do here but wait and pray for a blessing from Allah. But we are strong, and we are going to get through this.”

By Athena Ankrah Aug. 1, 2022

TAPACHULA, Mexico – Around the world, millions of people are leaving their homes to seek refuge or asylum in safer, more prosperous countries. From Syria and Ukraine to Venezuela and Haiti, about 82.4 million people who have been forcibly displaced must leave everything they’ve known to seek a better life.

Tens of thousands of them end up in Tapachula, an ancient city of 350,000 people less than 20 miles from Mexico’s border with Guatemala. It’s also more than 2,000 miles from Nogales, Sonora, on the U.S. border.

Tapachula is a gateway into Mexico for thousands of migrants moving north every year. Many have plans to reach the U.S., but all have to wait in Tapachula for Mexican immigration offices to process their requests for documents to work in the country or leave the city.

The crush of migrants and refugees is overwhelming the immigration system, so it often takes months to get the necessary appointments with them. While the process grinds on, public parks are sleeping grounds, local shelters are at capacity and tensions seem only to rise.

In Tapachula, the site of one of the largest humanitarian crises in the Western Hemisphere, about a third of those stranded are younger than 18, according to UNICEF.

Some kids traveling with parents or older family members are able to find space in one of the city’s shelters.

(To protect identities, everyone in this story will be referred to by first name only).

Carlos, 16, who’s from Honduras, is one of those fortunate enough to have a place to stay. In March, Carlos had been in Tapachula for a little more than a week, traveling with his 23-year-old cousin to join Carlos’ parents and sisters in Puebla, Mexico, further north.

“My case has been difficult, it was sudden, but with God’s help I’ve kept going,” he said.

Carlos spends his days at Hospitalidad y Solidaridad, a shelter for refugees and asylum seekers. He and his cousin walked from Honduras through Guatemala to Mexico in a day and a half.

“Two or three days ago, I had an anxiety attack or depression because I hadn’t had time to process everything that had happened,” he said. “Then it hit me; running out and not being like a locked up prisoner. But now, thank God, I have calmed down, and I have no choice but to come here … and because of the circumstances, I can’t return” to Honduras.

His parents and sisters, who had left home eight or nine months earlier to get permanent residence and documentation, also passed through Hospitalidad y Solidaridad on the way. At a picnic table outside the shelter, Carlos talked about what brought him here.

“Gang threats,” he said. “My dad apparently had problems with them, but it had been mostly because of misunderstandings. … And I had no choice but to come here to look for my dad.”

Directors at the shelter said Carlos’ father must come to Tapachula from Puebla to go through a formal family reunification process with immigration officials.

In 2021, Tapachula reported receiving more than 130,000 asylum seekers. The monthly number of refugee-status applications received by COMAR, the Mexican office for refugee assistance, went from about 6,000 in 2019 to almost 11,000 in 2021.

A large number of migrants stuck here are from Haiti. Some left their Caribbean nation recently, but many had worked in Brazil, Colombia, Chile and Venezuela over the past decade. In 2019, COMAR reported that less than 10% of asylum seekers were Haitian. By 2021, 51,000 Haitians were seeking asylum, making up nearly 40% of all such applicants in Mexico.

All migrants, but especially Haitian migrants, say it has been extremely difficult waiting in Tapachula for weeks, sometimes months, to get permission to stay and work in Mexico or continue to the U.S. or Canada.

“They sell us everything more expensive,” said Freddy, 42, a Haitian migrant who arrived in August 2021. “Even the house, the apartment. The rent is much more expensive because you’re a migrant.”

Freddy is one of two Creole translators working in Tapachula to help others through the Mexican immigration process.

“Most of them, you know, have been here for eight month, one year, so if you have no documents, you are not able to go to school, to get proper health care, you have nothing,” he said. “It’s like they tell you here: You are not a person.”

For parents of young kids, Freddy said, securing a safe place to sleep or even finding their next meal are daily challenges. And enrolling in school isn’t an option until their documents are in order.

“Not even 5% of migrant kids go to school,” Freddy said.

Haiti has seen more than its share of political and environmental disasters in the past year, including the assassination of Prime Minister Jovenel Moïse and an enormous earthquake, quickly followed by tropical storm Grace. An earlier wave of Haitian migration to South America was spurred by a 2010 earthquake that displaced more than 1.5 million people.

In southern Mexico, Haitian migrants face extreme xenophobia and racism from locals. Many Black immigrants say they face discrimination when looking for jobs, housing and immigration services. They also say Mexican officials help migrants from Spanish-speaking countries navigate the complex immigration system.

Officials in Tapachula defended the government’s treatment of Black migrants. They said the system is simply overwhelmed and lacks resources, including Creole translators.

Last November, the Mexican government held a conference on the mistreatment of migrants, sponsored by COMAR, in which it denounced racism and xenophobia aimed at migrants.

“People in transit have historically faced prejudices and stigmas that have caused the normalization of false beliefs that are an attempt to justify them receiving unequal treatment and injustice,” the commission said in a news release. “Their vulnerable situation increases because of the language and attitudes of xenophobia that they experience in this country.”

The news release said the government, and COMAR specifically, is committed to eradicating stereotypes, prejudices, and stigmas against migrants – through training and education.

In mid-July, COMAR official Cinthia Perez Trejo told Cronkite News in an email there is “no difference in treatment” for migrants seeking refugee status. Perez noted “procedures within the office of the Secretary of Governance of Mexico for sanctioning any public official who commits such acts.”

The U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) provides legal aid and other resources to some migrants, depending on their vulnerability. That office has said it is adding Creole interpreters, scheduling and facilitating appointments with COMAR, and building a labor integration program to alleviate some of the pressure.

We’re sitting in the small chapel outside Casa del Migrante Scalabrini Albergue Belén, a shelter that has exceeded its 150-bed capacity. It’s midday, and cots are strewn about the chapel floor and backpacks full of clothes fill the pews. Several families sit under the chapel roof in the rain.

Nati, 28, of Haiti, has been in Tapachula for nine months awaiting documents. She and her family were denied humanitarian visas in December, and had to start the application process over again. Those visas would have cleared them for travel through Mexico.

“It was difficult at COMAR because of so much waiting, they gave me a negative result. It was very difficult for us. … It’s like we are here with nothing because we have nothing, because we are without papers.” Nati said.

“When a Black person goes to get help, they don’t give it to you, and if you’re white, they do give it. I’ve asked UNHCR for help three times, all three times they’ve told me no.”

Nati, her husband, Panchi, and 2-year-old daughter Ana spent two years in Brazil before traversing the Darién Gap, the extremely dangerous jungle between Colombia in South America and Panama in Central America.

“We encountered many things, a lot of danger to get here,” she said. “In all the countries it was hard, but here it is the most difficult – everything takes longer. … This country has been the hardest. We have passed through ten countries and had the most difficulty here in Mexico. They (children) don’t understand that to get here we have come far, we have been in the jungle, in the rain, risked our lives – they don’t understand this.”

Nati and her family want to make it to Tijuana, south of San Diego, but all they’ve been able to do is wait and watch as others, mostly Central Americans, pass through the shelter.

“When you’re here you have to wait, appeal a case for another year – that’s going to be two years, and wait a year just to be told no. … It’s unfair,” she said.

In March, President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador

(known by his initials AMLO) visited Tapachula. As a couple hundred migrants protested outside the news conference tent, AMLO presented a plan to address the crisis by stimulating the economies of the countries of origin. An immediate solution to the mass of refugees sleeping in public parks wasn’t mentioned.

AMLO did commit to giving out 950 humanitarian visas to refugees (a status that takes months to achieve), but the National Institute of Migration and the U.N.’s humanitarian aid offices continue to draw crowds by the early hours of the morning, as thousands of refugees demand action.

All remain without work or clearance to leave the city; otherwise, they could be arrested and detained. Nati said she’s left with no options.

“All I can do is wait, and wait for them to give me another result,” she said.

Freddy said he and other Haitian refugees will be continuing to work together over the next few years to help one another to navigate daily challenges and parents detained at the migrant detention center known as Siglo XXI.

“We don’t want kids keep leaving on (their) own because a parent (is) in jail in Siglo XXI, we want kids able to go to school, so somehow we have to keep fighting,” he said.

Carlos said he’s hopeful for his future, with more opportunities for education in Tapachula than in Honduras.

The shelter where he stays has a minischool with a teacher who teaches kids and adults throughout the week.

“Personally, my goal is, first of all, to be with my parents. Second, finish the school cycle, go to high school and then study a trade,” Carlos said.

Until he reunites with his father, he’ll be in his room.

“In my opinion,” he said, “it is better to know people from afar. That is, to see them and how they behave. See them as they are and not interact so much with them. Because in my experience, in my life, I have had quite a few people who have hurt me.”

Despite stacked odds and untenable delays, young adults and child migrants in Tapachula have no choice but to remain resilient, still waiting and hoping to make it out of the city.