4 minute read

In focus: Migrants languish in Mexico’s chaotic immigration system

By Taylor Bayly Sept. 22, 2022

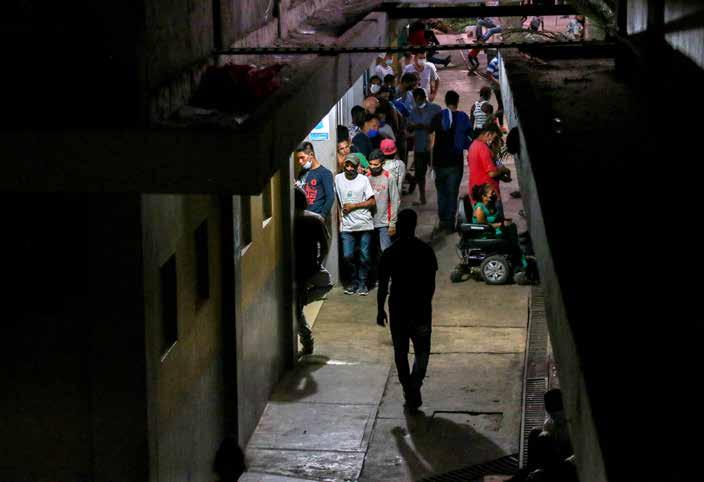

TAPACHULA, Mexico – Migrants have gathered in the thousands in Tapachula, seeking to apply for asylum or humanitarian visas to stay in Mexico or continue their journeys north. Protests outside Mexico’s immigration office have become more frequent as applications bog down and migrants struggle with limited access to social services and basic needs.

A young man sits clutching his immigration paperwork in front of a National Guard barricade that separates migrants from the National Migration Institute office in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 7, 2022. Tens of thousands of people, from Africa to Central and South America, have arrived at Mexico’s southern border seeking asylum from persecution, political instability and a lack of economic opportunities. Immigration policies have left people stranded and vulnerable as the massive backlog of immigration and asylum applications only grows. (Photo by Taylor Bayly/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

An official with National Migration Institute reaches to inspect a migrant’s paperwork on March, 8, 2022. Refugees often wait months for their scheduled appointment at INM, where immigration officials will determine whether they have sufficient evidence to make an asylum claim. Only a small fraction of those waiting are granted an interview each day, and they aren’t allowed to continue traveling north without the documents.

A woman rests her head on her paperwork and a metal barrier that prevents refugees from spilling into the street outside the federal immigration office in Tapachula, Mexico, on March, 8, 2022. There are a handful of migrant shelters in Tapachula, but occupancy requirements and overcrowding restricts access and forces many to sleep on the streets or in parks. Those who can afford apartments face rent hikes meant to price out migrants, especially Haitians. Migrants who choose to work under the table without permits are vulnerable to exploitation by their employers. (Photo

Reino Fuentes arrived in Tapachula, Mexico, in early February, having fled from persecution in Venezuela with his wife and young son. In 2021, Human Rights Watch concluded that Venezuela is facing a “severe humanitarian emergency, with millions unable to access basic healthcare and adequate nutrition.” The same report noted that Venezuelan authorities and security forces targeted opponents through extrajudicial executions, forced disappearances and torture. Photo taken March 8, 2022.

Daniela Cisneros and her young child, Mesias, rest outside the National Migration Institute office in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 8, 2022. Most migrants here will seek entry to the United States, and many will apply for asylum or refugee status. According to the Migration Policy Institute, nearly 12,000 people were granted refugee status in the U.S. in 2020, which represents a tiny fraction of the current 1.7 million immigration cases backlogged in U.S. courts. (Photo by Taylor Bayly/ Cronkite Borderlands Project)

Protesters walk toward a barricade of Mexican National Guard members on March 4, 2022, outside immigration offices in Tapachula, Mexico. Some shout and make threatening gestures, others drop to their knees and raise their arms in a sign of nonviolence. Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador formed the National Guard in late May 2019, to replace the federal police force, which was largely seen as corrupt. López Obrador then quickly deployed thousands of guardsmen to Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala. Human rights organizations criticized the mobilization, with Amnesty International arguing that the deployment of some Mexican security forces coincides with “an increase in human rights violations and in levels of violence.” (Photo by Taylor

A migrant lobs a chunk of concrete at national guardsmen in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 4, 2022. Migrants dislodged pieces of loose concrete from a sidewalk and bashed them against a curb to break it into smaller pieces. Guardsmen threw the pieces back at the migrants; it wasn’t clear whether anyone required medical attention. (Photo

Migrants in Tapachula, Mexico, attempt to reach a consensus on the strategy of the protest on March 4, 2022, with some migrants trying to restrain others throwing chunks of concrete at security forces. Many of the migrants are from Haiti, which was devastated by a magnitude seven earthquake in 2010 – forcing thousands to relocate to Central and South America. Since the loosening of COVID-19 travel restrictions and the 2021 assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse, many Haitians –both in Haiti and abroad – are traveling north seeking humanitarian visas and asylum status. Haitians made up nearly 40% of all migrants seeking protection in Mexico in 2021. (Photo by Taylor Bayly/ Cronkite Borderlands Project).

At the height of the demonstration in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 4, 2022, protesters hold a stainless steel chain to form a line in front of the National Guard barricade. In 2019, then-President Donald Trump announced that migrants traveling north through Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala would be required to first apply for asylum in those countries before being eligible for asylum in the U.S. The policy drew criticism from advocacy groups, as these countries lack the capacity to shelter migrants. The Biden administration ended the agreements in February 2021.

Migrants in Tapachula, Mexico, yell at members of the national guard in a tense confrontation on March 4, 2022. According to Human Rights Watch, it’s common for Mexican cartels, criminals and “sometimes police and migration officials to … rob, kidnap, extort, rape or kill” migrants traveling through Mexico. Many migrants in Tapachula allege that Mexican immigration officials accept bribes from migrants to fast track asylum applications.

A member of Mexican security forces in Tapachula, Mexico, braces her shield as the demonstration escalates on March 4, 2022. More than two-thirds of all refugee applications filed in Mexico come from Tapachula, where the lack of access to shelter, health care, economic opportunities and safety leave many desperate and vulnerable. (Photo by Taylor Bayly/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

As brush fires die and the migrant demonstration ends on March 4, 2022, members of the National Guard continue to defend the immigration office in Tapachula, Mexico. Two weeks later, Tapachula’s immigration office suspended its operations after staff members were injured during a violent altercation with migrants, according to a UNICEF report. As of March 19, there were an estimated 30,000 people in Tapachula applying for asylum or humanitarian visas. (Photo by Taylor Bayly/Cronkite Borderlands Project)