Spring 2023 Vol. 10, No. 1 Culture

OUR VISION

A campus that witnesses the subversive person of Jesus and accepts the reality of the Gospel.

2 | vol. 10, no. 1

OUR MISSION

To proclaim the life and power of God's truth to the Columbia community and beyond through diverse Christian voices and ideas.

The Witness | 3

Timothy Kinnamon

4 | vol. 10, no. 1 Table of Contents 06 The Walk Daniel Campos-Rojano 07 Reflection between the Old and New Natalia Espinoza 10 Eucharistic Revival and Catholicity

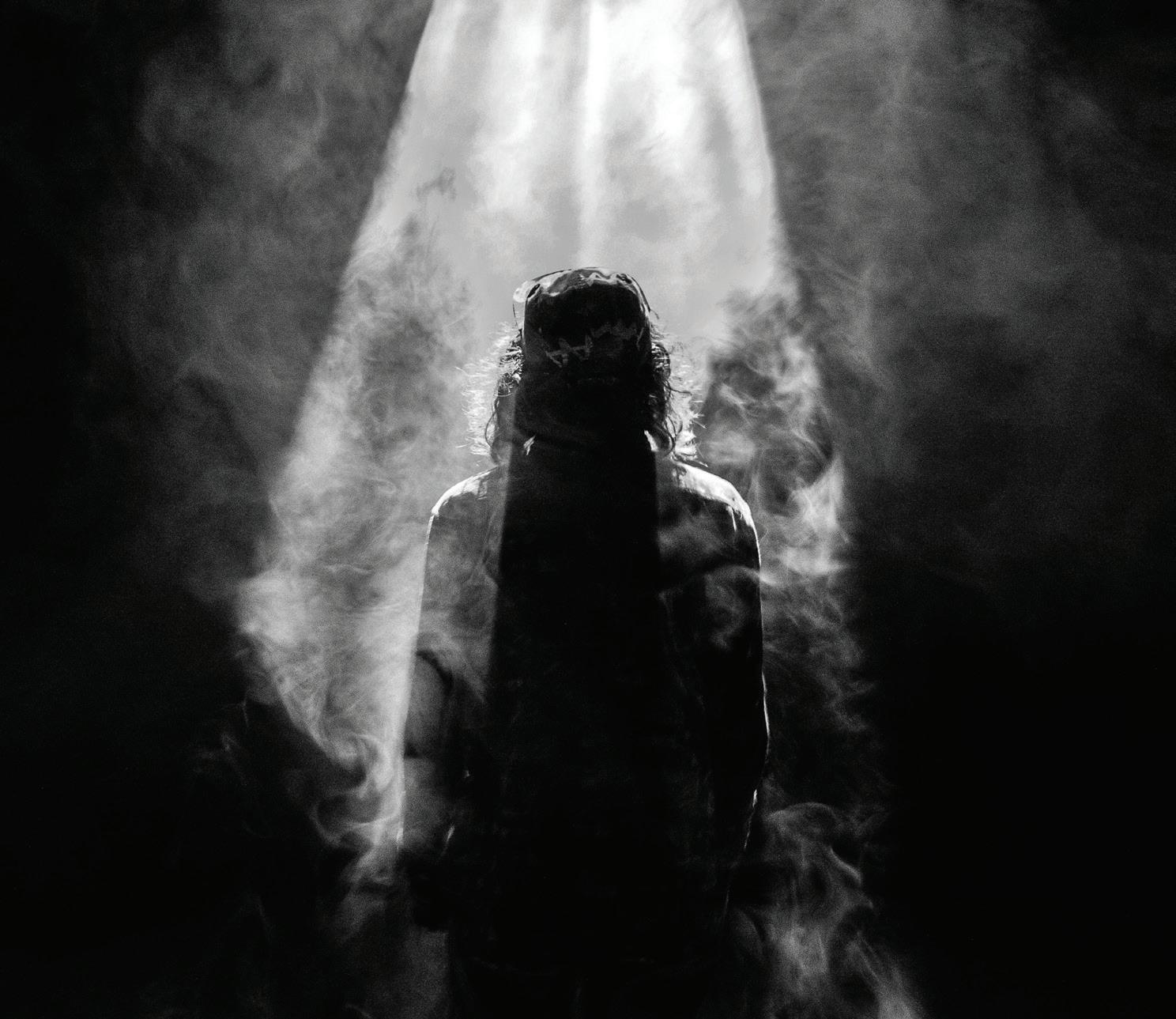

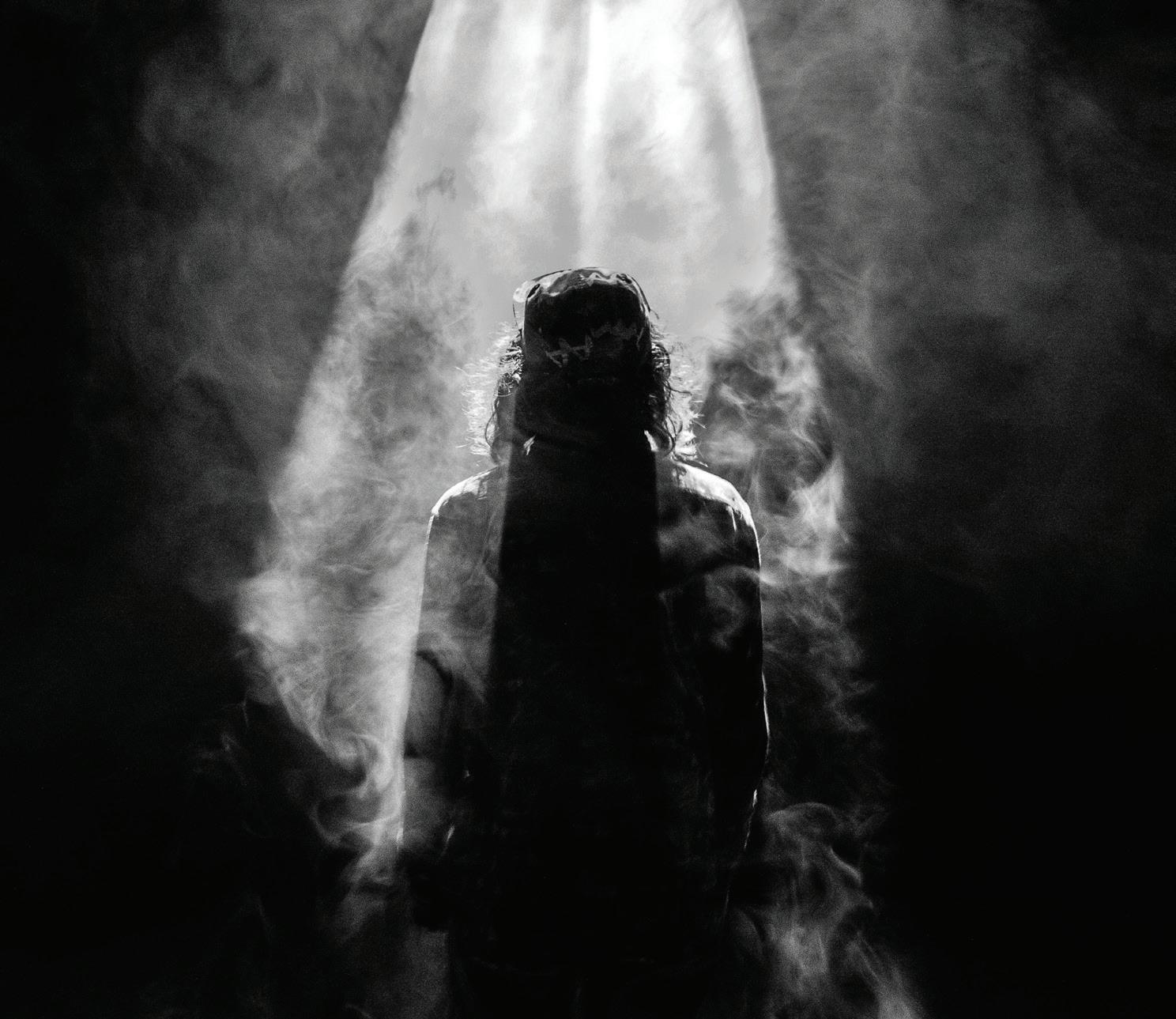

Martyr Nature

19 In the Midst of Death, We Shall Live Allegra Nshuti 15 Cultivating Joy, Accepting Unhappiness

Kelley

Vintage Culture

Finding Rest in Stress Culture

Contra Christendom?

For Self and Same

Lorenzo Garcia 22

Thomas Harris

Benjamin

25

Gustavo Alcantar 28

Ashley Kim 31

Benjamin Brake 38

EDITOR IN CHIEF

Elizabeth Huang

MANAGING EDITOR

Ben Kelley

PRINT HEAD

Victoria Choe

BLOG HEAD

Dorothy Zhang

DESIGN HEAD

Annie Son

WEB HEAD

Mandy Jenkins

PODCAST HEAD

Ardaschir Arguelles

SOCIAL MEDIA HEAD

Natalia Espinoza

PRINT

Annie Son | Benjamin Brake

Chase Chumchal

Jean Shin | Tony Kim

BLOG

Ashley Kim | Michael Manasseh

Gustavo Isaac Alcantar

DESIGN

Dorothy Zhang | Lucy Collins

Michael Manasseh | Tony Kim

PODCAST

Joel Kattady | Rory Wilson

Technician: Jonah Dewing

Producer: Natalia Espinoza

Design and Editing:

Lucy Collins | Silas Link

Dear Reader,

If you google the term “culture,” you will find more definitions than you can count on one hand with each individual meaning hosting its own subset of bullet points. You will find keywords such as “social behaviors,” “customs,” “arts,” “institutions,” “norms,” “knowledge,” “ideas,” “beliefs,” and so on. It is an elusive and slippery term that seems to encompass practically every area of daily life.

The purpose of this journal is to explore the cultural characteristics of the Columbia experience, observe the effects this culture has on its students, and proclaim how the Gospel speaks to its greatest needs. Throughout these pages, you will find pieces that touch on topics including identity, language, mental health, the environment, the economy, and the notion of a “Christian culture.” This issue is for those who find themselves yet again taking advantage of Butler’s nonexistent closing time and feel more familiar with fear than joy (check out pages 15 and 28). This issue is for those who are looking to rediscover their awe of our campus’s beauty (page 22!). This issue is for you.

Thank you so much for picking up a copy of The Columbia Witness, and on behalf of our team, we hope that you will enjoy reading it as much as we have enjoyed creating it.

God Bless,

Elizabeth Huang Spring 2023

The Witness | 5

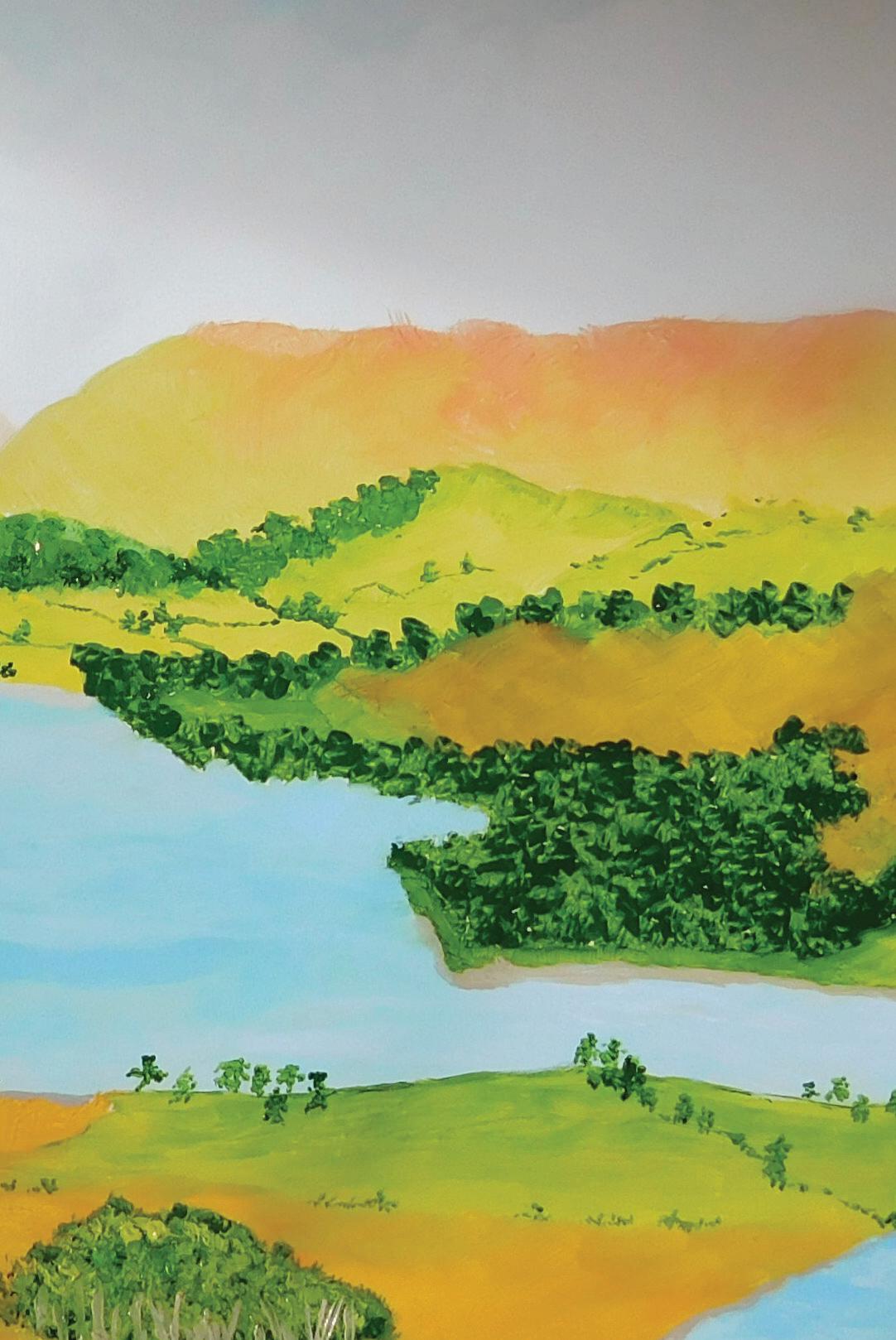

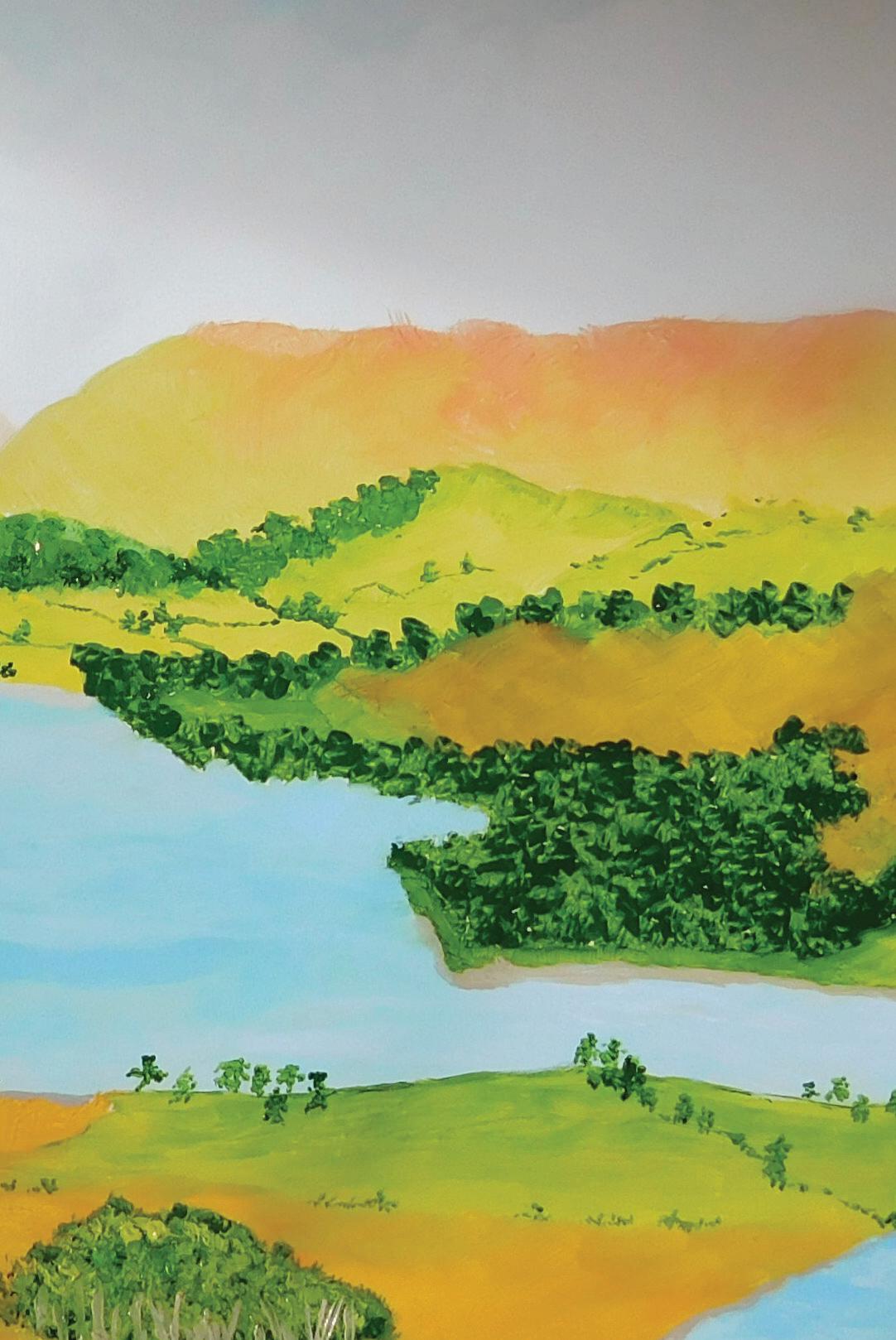

Cover art by Annie Son

The Walk

Daniel Gustavo Campos-Rojanos

Meter: Sapphic Strophe ¯ ˘ ¯ | x ¯ // ˘ ˘ ¯ ˘ ¯ ¯

Dē Puerō Turbulentō Arborēs firmās, trepidās aquās nox pācat et dulcῑs venerēs huiusce fortem et immēnsum Deum ob rēs amantis arbore vērā.

Quōmodo adloquar, trepidāns timōre, per stilōs meōs studiōsa verba in scholā affirmāns pietātem et rectum ecce Deum esse?

Vῑdimus gents, populōs ruentῑs nūntiāre et daemōn benedῑcere Eum iam; cūr ego stāns hῑc, dubitem tendῑ cum ceterῑs nunc?

6 | vol. 10, no. 1

¯

¯

¯ ˘

¯ ¯

˘ ¯ | x ¯ // ˘ ˘ ¯ ˘ ¯ ¯

˘ ¯ | x ¯ // ˘ ˘ ¯ ˘ ¯ ¯

˘

On a Turbulent Boy Night calms firm trees, trepid waters, And the sweet loves of this boy, Loving a strong and boundless God on account of his circumstances in the true tree

How should I address, trembling in fear, The zealous words through my style In class, affirming that gentleness and goodness behold!, are God?

We have seen nations and people rushing To announce that even a devil already speaks well of Him; Why should I, standing here, hesitate to be extended with the rest now?

The Witness | 7

Reflection between the Old and New

Natalia Espinoza

The first time I heard someone speak in tongues, my body curled up in a way I never felt before, the way a snake’s skin recoils when preparing to shed a part of itself. The woman sat at the altar, spitting words, a conglomerate of hymns and expressions in both her Native Dominican Spanish and broken English. She yelled out words I’d usually hear my mother and grandmother say over the phone whenever someone from the DR needed prayer, spitting out exclamations: “¡Saca los demonios en el nombre de Jesúscristo, Señor!”1 among others. This woman’s words became wobbly, like an unstructured building in an earthquake, as she spat out words my brain could not understand. Upon my questioning, my mother, sitting on my left, informed me that what I witnessed was none other than the work of the Holy Spirit in a newly repented sinner’s life. The speaking was part of what confirmed her passage as a Christian and her newly acquired seat in the City of God. I continued watching as the rest of the congregation joined her. Ten, twenty, fifty, maybe a hundred people began chanting with her in this alien language, crying and screaming to Señor for healing and redemption from a barrage of topics, including drug abuse, fatherlessness, and gossip. The music began to caress my skin. Though I was young, I knew this was an awesome and striking experience, hearing the proof of God’s salvation shot from the mouths of my little Latino community. So much so, my mouth began to open ever so slightly, wanting to join, and in my head, asking God “Please save me too.”

But then, nothing happened. My mom told me after the service I’d speak in tongues one day. All Christians do.

Growing up in an Old Church, I was never one to blindly believe revelations suddenly given to someone by dream, word of mouth, or any standard charismatic actions most pentecostals have copyrighted. A funny example includes when someone told my ex-boyfriend that I would be his future wife, whereas another person told me the opposite (the latter prophesied correctly). During my most formative years, I was taught that Pentecostalism maintains a faith in God that other denominations lack. Acts 2 was imprinted onto my head, and I understood that the Lord blesses people with gifts so that His goodness would be evident to the world. I knew the gifts of the spirit are a manifestation of God’s goodness, yet I could never figure out why I felt embarrassed as a witness.

8 | vol. 10, no. 1

1 “Save me from the demons in the name of Jesus Christ, Lord.”

I felt ashamed whenever my peers would whip out purple and red silk flags, waving them while dancing all throughout the aisles, and why I always stood to myself when the conga line for Jesus began to wrap itself around the main church room. As a kid in the Old Church, I knew I was a Christian, I just needed more time to bloom. Eventually, I’d understand why I was so different from everyone else and I’d be able to delight in the Lord’s presence with grandiose colorful reactions–and speak in tongues, just like everyone else.

But I never did speak in tongues. I never wanted to force it, so everytime I felt “something,” I opened my mouth and said “ahh” as if asking God for a taste. I couldn’t hear beauty in these jumbles of words or understand why I couldn’t, especially when all of my adolescent Christian friends, their parents, and grandparents, and newly saved Christians were able to. After many fiery years bargaining with God, being prayed on with a dozen hands over me, and asking the Holy Spirit to anoint me, it never happened. If I cannot engage with this incredible central component to my Church’s identity, can I even call myself a Christian at all?

I’ve always liked linguistics, and having grown up in a Spanish speaking household, it’s fascinating seeing the ways in which both standard American culture and Hispanic immigrant culture bleed into each other. Standard Americans12 tend to speak in a way as not to offend, sprinkling in “pretty pleases” and “if you must, would you please be able to…” and many more in order to avoid direct statements, which can be misconstrued as rude. Hispanic culture is generally the opposite. You want something: you ask for it directly. You don’t beat around the bush and you certainly don’t do it to make the other person feel like they are not being spoken to in a rude way. This is one of the reasons Pentecostalism blew up in Latin America in the past century.3 When you want healing from a severe health crisis and financial security after fleeing a dictatorship, you command the Holy Spirit to come down and help now. A more stable sect of stable American/Dutch Presbyterianism tends to dedicate more effort toward religious study and common sense when considering right from evil, and ultimately, how they perceive God.4

I never realized how striking my Americanness and my Hispanicness bled into the way my family and I practiced Christianity until I attended my first Presbyterian service ten years later during my first year of college. The service was static, yet pumped like a heartbeat. The lights dimmed and everyone in the congregation bowed their heads as the pianists and violinists began their jams, as a woman in a long formal floral dress sang. The hymns were available to us on paper when we entered the church, along with an organized list of what would commence throughout the remainder of the service–including an infant Baptism. Despite thinking that this is beautiful, I felt a similar recoil in my skin. The style of worship, the organization, the emphasis on hymns and personal one-on-one connection with God without the grandiose dance moves or tongues, I couldn’t help but think that I was doing something wrong. Obviously if these people were different, either they just did not love the Lord enough, or they were simply do-

2 Obviously there is no such thing as a “standard American.” In my piece, I refer to a general type of American who can trace their background in this country for three more generations.

3 Based on an article from Pew Research by David Masci:Why has Pentecostalism grown so dramatically in Latin America?

ing it wrong. But curiosity won its battle over apprehension in my heart, and I continued going to a Presbyterian Church throughout my time in College, and occasionally visited Old Church whenever I went home.

In being able to call both of these Churches home simultaneously, I praise God that I was not as divisive over which side is more theologically correct than the other. I have theological reservations with both the Presbyterian and Pentecostal Church: in my experience the former can have a rigid view of the gifts of the Spirit, while the latter can idolize them. But in my reflection, I have found beauty in seeing how two slices of Christianity, and the cultures that swaddle the two have profoundly shaped my relationship with Christ. In my New Church, I am free to not feel uncomfortable whenever I do not wish to raise my hands, dance, or sing until I am blue in the face. I am free to discuss the academic sides of Christianity thoroughly with deacons and pastors, whereas such questions at Old Church were either unanswered, or unfortunately, discouraged.

But when considering my ethnic identity, I adore the zealous and direct attitudes with which my Dominican family has taught me to speak to our Father, especially whenever I pray in Spanish. Old Church was where my family and I were saved, and it is the Church that established the theological framework I have in my mind and that I have refined in New Church. And despite their differences, both Churches strive to edify and glorify the good news of the Gospel and truth of Jesus’ power over each and every one of our lives. How could I be opposed to that?

As I continue in my discipleship and journey to serve New Church, the more I realize how the same we can be despite the obvious cultural differences. The other day when the congregation became especially passionate during worship (with even a few hand raises!), I looked up and I saw walls, the singing, the prayer and worship. The beat of the worship caressed my skin, and when I closed my eyes, I thanked God how two places can be so different yet exactly the same.

Natalia Espinoza (CC’24) is a junior studying English Literature and Hispanic Studies. She enjoys philosophy, podcasts, linguistics, and traveling. Feel free to reach out to her at nne2107@columbia.edu.

The Witness | 9

4 “Racial and ethnic composition among members of the Presbyterian Church in America” by Pew Research Center.

The Primacy of the Eucharist, the Body of Christ, and the Vision of Catholic Eucharist Revival

Lorenzo Garcia

“My beloved is all radiant and ruddy distinguished among ten thousand… His body is ivory work, encrusted with sapphires… His speech is most sweet, and he is altogether desirable.”

-The Bride

(The Canticle of Canticles 5:10, 14b, 16a)

In the early 1950s in Communist China, a Roman Catholic priest was arrested by Communist soldiers and imprisoned in a house next to his parish church. Inside the Church, the consecrated hosts of the tabernacle were desecrated by Communist troops, who spilled them on the floor while looting the church. Soldiers barred the parishioners from entering the Church and threw the parish priest under arrest in an adjacent cell to stop him from celebrating the mass. Fortunately, the priest still had a view of the tabernacle of the church from his prison cell, allowing him to view the Eucharist each morning and night in adoration. The sense of desperation in the town was stifling, as the faithful were prohibited from celebrating the mass in union with each other.

In the midst of this persecution and hardship, on the night on the first day of his imprisonment, to the priest’s great amazement, a young girl known apocryphally as “Little Li” snuck past the guards by opening a window to quietly enter the sanctuary and consume one of the hosts with her mouth to the floor. She would secretly return each night for many days, visiting the church to regularly consume a host and maintain her devotion to the body of Christ. Tragically however, as she entered the sanctuary one night and had a consecrated host on the tip of her lips, a soldier discovered her and shot her, ending her life in a final and heroic act of communion with the Lord.1

For Catholics around the world, this story of “Little Li” is indeed the story of an exceptional martyr worthy of praise. The venerable Archbishop Fulton Sheen, for instance, described “Little Li” as the person who had most inspired him in his life to develop his singular devotion to the Most Blessed Sacrament. Even one of the soldiers on patrol in the town later claimed that if everyone had the faith of Little Li, there would be no remaining Communist soldiers. But, crucially, this story also centers on a virtue that all Catholics are meant to embrace, cultivate, and cherish: a pure and overflowing love for the Eucharist.

The Catholic Church recognizes and has always recognized the Eucharist from the time of the apostles as “the source and summit of the Christian Life” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1324). This recognition of its primacy among all of the other seven sacraments in the Church is due to the identity of the Eucharist as the truly present and substantial body of Christ. In an era of waning devotion to the Eucharist and a failure on the part of many Catholics to recognize the Eucharist as the body of Christ, a Eucharistic

10 | vol. 10, no. 1

1 Charlotte Allen, “Little Li: The Child Martyr of the Eucharist in China” (Benedict XVI Institute, 21 Sept. 2021).

Revival has emerged among the clergy and faithful laity across the United States in an attempt to revivify Catholic devotion to the Most Blessed Sacrament. But, this yearning for Catholic reinvigoration is not just a call to receive Christ in the body and in the blood and to proclaim the truth and power of the sacrament. It is also a matter of what the Eucharist symbolizes and truly is — a sign and assurance of “Catholicity,” or unity among the members of the Church in the body of Christ.

This unity has been the distinctive bedrock for two millennia of Catholic Eucharistic theology. Catholics from the time of the apostles have affirmed that the Eucharist is the body of Christ. The fifth century Church Father St. Augustine, in his Sermon 272 on the Eucharist, claimed that the responses of the laity during the mass, during which the body of Christ is offered to the Father as the true sacrifice of Calvary, affirm not merely the reality that the bread is the body of Christ but also confirm the members of the congregation in their identity as the mystical body of Christ:

When you hear “The body of Christ,” you reply “Amen.” Be a member of Christ’s body, then, so that your “Amen” may

ring true! But what role does the bread play? We have no theory of our own to propose here; listen, instead, to what Paul says about this sacrament: ‘The bread is one, and we, though many, are one body.’ [1 Cor. 10.17] Understand and rejoice: unity, truth, faithfulness, love.

To say “Amen” when the priest consecrates the bread as the body of Christ is, in Augustine’s view, to recognize one’s identity as a member of that very “one, holy, Catholic, and Apostolic” body of Christ which one is about to receive, which is the Church herself according to the Nicene Creed. In Augustine’s words, “Remember: bread doesn’t come from a single grain, but from many…Be what you see; receive what you are.”2

The Church, although composed of different members, is a unified whole which must remain cohesive to remain fertile, and each time the faithful receive the Eucharist even today, they reunite and reconfirm themselves in that identity as the members of that very body of Christ given up on calvary for the sins of the world.

This paradox of the body as at once the unified whole of believers and also the Eucharist forms the very 2 Augustine, Sermon 272 on the Eucharist.

The Witness | 11

“When you hear “The body of Christ”, you reply “Amen.” Be a member of Christ’s body, then, so that your “Amen” may ring true! But what role does the bread play? We have no theory of our own to propose here; listen, instead, to what Paul says about this sacrament: ‘The bread is one, and we, though many, are one body.’ [1 Cor. 10.17]

essence and heart of a Eucharistic understanding of the Church that is attempting to be revived in the modern day. This is, notably, the Pauline position on the nature of the Church found in the First Letter to the Corinthians. St. Paul writes, “For just as the one body is one and has many members, and all the members of the body, though many, are one body, so it is with Christ. For by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body – Jews or Greeks, slaves or free – and all were made to drink of one Spirit” (1 Cor. 12:12). And because the body which the baptized faithful form as a community is this mystical body of Christ, it is therefore with complete condemnation and impropriety that one partakes of the Eucharistic body of Christ unworthily: “Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord” (1 Cor. 11:27). For a member of the body of Christ to profane “the body and blood of the Lord,” as Paul notes, through receiving the Eucharist without the proper disposition means that a man “eats and drinks judgment upon himself” (1 Cor. 11:29) by despising the body of Christ, an act tantamount to persecuting one’s Christian brethren who themselves form parts of the body of Christ. It is an act of disunity which threatens the very fabric of the whole of the church.

The unity which is reflected in the Augustinian view of the Eucharist as the body of Christ, a formative part of his rejection of the Donatist heresy, which disavowed any subordination to the hierarchical, ecclesiastical

structure of the Church, has echoed throughout the centuries in the words of Catholic theologians due to Christ’s perennial words, “This is my body, which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me” (Luke 22:19). St. John Chyrostom notes that these words of Christ, by the divine power to effect this mysterious substantial change, manifest at every mass in which bread and wine are consecrated into the body and blood of Christ: “It is not man that causes the things offered to become the Body and Blood of Christ, but he who was crucified for us…. The priest, in the role of Christ, pronounces these words, but their power and grace are God’s.”3

The later Thomistic view of the Eucharist is centered primarily on love, and the Eucharist is, in the words of St. Thomas, the “Sacrament of Love” and the “consummation of the whole spiritual life,” or “the end of all the sacraments.”4 As the Fathers of the Fourth Lateran Council affirmed: “His [Jesus’s] body and blood are truly contained in the sacrament of the altar under the forms of bread and wine, the bread and wine having been changed in substance, by God’s power, into his body and blood, so that in order to achieve this mystery of unity we receive from God what he received from us.”5 As the Catholic Church would later re-affirm following the Second Vatican Council, Christ humbled himself to receive our humanity so that we could be raised up to receive his divinity [CCC6 460].

3 St. John of the Cross, In proditionem Judae, 83.

4 St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Tertia Pars, Art. 1, Q. 3.

5 Fourth Lateran Council Decrees, Canon 1.

6 This abbreviation, “CCC,” is meant to signify the

12 | vol. 10, no. 1

“

The Church, although composed of different members, is a unified whole which must remain cohesive to remain fertile, and each time the faithful receive the Eucharist even today, they reunite and reconfirm themselves in that identity as the members of that very body of Christ given up on calvary for the sins of the world.

For Catholics, the Eucharist is therefore intimately connected with trinitarian theology and our identity as children of God, but what does this have to do with the push for Eucharsitic revival? Without an understanding of the multivalent and essential power of the Eucharist and the theology underlying its significance, devoted Catholics are powerless to effect real change in the attitudes surrounding the Eucharist. No wonder the United States Council of Catholic Bishops, on Corpus Christi Sunday, June 19, 2022, announced a new “vision” of the Eucharistic revival in the United States which centers on the attempt to develop a firm relationship with Jesus Christ in the Blessed Sacrament and to foster unity among Catholics7: a 2019 study reveals that only 69% of US Catholics actually believe in the real presence of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist.8 We may well wonder how much of this is due to the lack of effective catechesis and to the lack of an appreciation for the body of Christ within Catholic households and dioceses. If the Eucharist truly is the body, blood, soul, and divinity of our Lord Jesus Christ, per Catholic doctrine [CCC 1374], then it is more precious than any other material thing in the entire world. To not teach one’s children about the power of the sacrament and what it truly is is not only a dereliction of duty but also a complete tragedy.

This is because if the Eucharist has been the bedrock of the Catholic faith, how much of a tragedy is it that the majority of Catholics cannot proclaim their full-hearted endorsement of Catechism of the Catholic Church.

7 “National Eucharistic Revival: A Grassroots Response to God’s Invitation” (National Eucharistic Revival: A Grassroots Response to God’s Invitation); Service, Catholic News, “Eucharistic Procession Takes Christ, His Gospel through Manhattan’s Streets” (Our Sunday Visitor, 14 Oct. 2022).

8 Pat Marrin, et al., “Pew Survey Shows Majority of Catholics Don’t Believe in ‘Real Presence’” (National Catholic Reporter).

its veritable presence? How greatly therefore should present-day Catholics who are in the midst of a Eucharistic revival yearn for the Eucharist? We should yearn for communion with our Lord, and invite our friends, family members, and colleagues to the everlasting banquet. We should yearn for the Eucharist completely. This is a standard which is hard for any imperfect, finite creature to achieve perfectly in this life, but which Catholics around the world must strive towards wholeheartedly. We should follow St. Ignatius of Antioch’s great acclamation of the power of the Eucharist to preserve us even to the point of martyrdom: “I have no taste for corruptible food nor for the pleasures of this life. I desire the bread of God, which is the flesh of Jesus Christ, who was of the seed of David; and for drink I desire his blood, which is love incorruptible.”9 This should be on our minds every time we step foot into a church to celebrate the liturgy. For Catholics, our joy should be in the eternal offering of the body and blood of Christ to the Father at each mass, and our love of the son’s magnificence must be immediate and complete.

This is the vision of Eucharistic revival. And with it, I daresay Catholics will change their families, their dioceses, and the world, fulfilling the apostolic mission of our Lord to always “do this in memory of me” (Lk 22:19). We must remember the words of St. Thomas Aquinas, when he says in his everlasting Eucharistic hymn Adoro te Devote:

9 Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Romans, 7:3.

The Witness | 13

“We should yearn for communion with our Lord, and invite our friends, family members, and colleagues to the everlasting banquet. We should yearn for the Eucharist completely.”

“O memoriale mortis Domini, Panis vivus vitam praestans homini, Præsta meæ menti de te vívere, Et te ille semper dulce sapere.”1

If our Lord humbled himself to accept to be fully present in a piece of bread because he desired to be with us so greatly, we must humble ourselves to proclaim his sweetness to those who so desperately need Him, fully present in the Eucharist, until He comes again. “Jesu, quem velatum nunc aspicio, Oro, fiat illud quod tam sitio: Ut te revelata cernens facie, Visu sim beátus tuæ gloriæ. Amen.”2

1 “O thou our reminder of Christ crucified/Living bread, the life of us for whom he died/Give this life to me then: feed and feast my mind/There be thou the sweetness man was meant to find.”

2 “Jesus whom I look at shrouded here below/I beseech thee send me, what I thirst for so/Some day to gaze on thee, face-to-face in light/And be blessed forever with thy glory’s sight. Amen.”

Lorenzo Garcia (CC’23) is a senior studying History and Philosophy. He is involved in the Catholic Ministries and enjoys hiking. You can reach him at ltg2117@columbia.edu.

14 | vol. 10, no. 1

Cultivating Joy, Accepting Unhappiness

In October of 2022, less than a month ago as I write this, the American Psychological Association published a feature article by Zara Abrams entitled “Student Mental Health is in Crisis.” Abrams’ report on the prevalence of mental health issues on campuses is grim — 60% is her most conservative estimate of what proportion of students experience a “mental health problem.” Abrams writes that students’ mental health is worsening “by nearly every metric.” Columbia is no exception. According to the most recent available Columbia Student Well-Being Survey, administered in 2020, which screens for mental illnesses, one in four students screened positively just for anxiety and depression. Moreover, a study from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that New York City experiences one of the highest levels of “misery” out of all major cities in the nation. Topping it off, Gallup’s Life Evaluation Index found that a record level of Americans evaluated their lives poorly enough to be categorized as “suffering” in July of 2022. More and more we appear to be developing a culture in which suffering is the norm.

This trend has been accompanied by an alarming decrease in the number of Americans who self-identify as Christians. The Pew Research Center estimated in 2020 that 64% of Americans were Christians. In 1990, that number was above 90%. If current trends continue, Christians will make up less than half of the country by 2070. A 2021 study from Gallup concluded that less than half of Americans consider religion to be a “very important” part of their lives, although that same study found that nearly 70% of Americans were Christian, and church attendance was even more abysmal, with less than 30% of Americans regularly attending a worship service. Even among professing Christians, an alarming amount of people are relatively uninvolved in the church. Numbers can only tell us so much and none of this suggests that the increase in mental illness and misery is caused by the apparent decrease in faith. There are, after all, a number of causes that are concomitant with the increased suffering that we are witnessing: better mental health diagnostics and increased awareness, the opioid epidemic, homelessness and unemployment rates, the effects of the pandemic, etc. No, there is a more pressing question here than why these things are happening. When people suffer, they search for a stable source of hope for comfort. 2 Corinthians 4:16-17 tells us that Christ offers a hope beyond all comparison and Matthew 25:35-40 encourages Christians to comfort those who are suffering. Why then, are people not running in droves to the Church and to Christ? Why are they doing the opposite?

The answer lies, at least partially, in American Christianity’s cultural ineptitude at expressing and confronting suffering. We have no script for dealing with pain. Cultures have scripts, or a prescribed method for handling a situation, for all phases of life from dating to education to worship to grieving. Christians are no exception. Yet, the church in America does not seem to have a framework for handling suffering. Worship music is almost universally happy, pain is frequently viewed as an unfortunate side effect of a fallen world, and when we pray for those who suffer we do so almost exclusively for non-Christians. The implicit message is shallow and superficial: that Christ’s mercy and God’s blessings are so abundant that a faithful Christian will always be happy. This message feeds the lie that a good God will not allow suf-

The Witness | 15

Benjamin Kelley

16 | vol. 10, no. 1

fering. Consequently, one of the top reasons that Americans, including influential atheist Bart Ehrman, leave the Church is because of their suffering.

But the Bible does not promise that we will not suffer or that we will always be happy. Job is tested by God with suffering and is rewarded with immense blessings after lifting up his pain honestly in prayer. In Psalm 88, the psalmist proclaims that “my companions have become darkness” (read: darkness is my only friend), and these are considered to be words breathed by the Holy Spirit. Christ, terrified of his imminent crucifixion, is encouraged by an angel to pray “in agony” until his sweat becomes “like great drops of blood” in Luke 22. Christ’s words in this moment are telling: “Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me. Nevertheless, not my will, but yours, be done” (Luke 22:42). Time and again the Bible confirms that pain is difficult and should be taken before God prayerfully and earnestly, and that suffering, though it is a result of sin, is a part of God’s plan: “Count it all joy, my brothers, when you meet trials of various kinds, for you know that the testing of your faith produces steadfastness” (James 1:2-3).

But what does it mean when James says to count suffering as joy? This “joy” is not quite the same as blind happiness. Hebrews elaborates on the meaning of joy in 10:34 when the author writes that “you joyfully accepted the plundering of your property, since you knew that you yourselves had a better possession and an abiding one,” and in 12:2, when the letter describes Christ as the one “who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame.” The second verse tells us that Christ felt shame, not happiness, during the crucifixion, and Luke’s account confirms that he desperately desired to avoid the cross, and yet he was joyful. Joy, then, is different from the feeling of happiness. Both the first and second verses show that joy springs from the hope of things to come: freedom from pain, heavenly treasures, etc. This hope, this joy, requires the acknowledgment of the depth of suffering that we face. Christians, then, ought to be joyful even when they cannot be happy.

The Witness | 17

What, then, does it look like to express deep discontent with suffering while remaining hopeful and joyful? The best template — the best script — is given to us in Lamentations. The book of Lamentations is a collection of five poems, written as laments, that describe and respond to the horrific destruction of Jerusalem by Babylon that ended the Jewish state and religious traditions until their revival decades later. The first poem describes what has happened to Jerusalem and confesses the sins of the people before God while the second expounds on God’s justice in dealing with the city and her people. The third poem continues these themes by describing how God has personally afflicted the author, until it turns in verses 22 and 23: “The steadfast love of the LORD never ceases, / his mercies never come to an end; / they are new every morning; / great is your faithfulness.” The poem goes on to exhort Israel to return to the ways of God and begs for justice for their enemies. The last two poems round out the book by describing the injustice done to Israel by Babylon, calling for their punishment and finally, returning to the miserable condition of the captive Israelites and mourning their demise. The book ends on a hopeful note: “Restore us to yourself, O LORD, that we may be restored! / Renew our days as of old – / unless you have

utterly rejected us, / and you remain exceedingly angry with us,” (Lamentations 5:21-22). Confident in the steady nature of God’s love and the security of His promises, the author boldly asks God to restore His people.

This is an incredible, God-given script for handling suffering. The elements of Lamentations’ response to suffering found here are acknowledgement of loss, confession of sins, affirmation of God’s justice, praise for God’s steadfastness, prayer for justice, and the expression of hope. Noticeably absent is an expression of happiness. The dominant images are, frankly, terrifying. Yet, the grief of the author is transformed into an audaciously triumphant hope in the assurance of God’s promises and a strong encouragement to the people of Israel to persevere. There is indeed a balm in Gilead!

The author of Lamentations has many reasons to rest securely in this hope, but we have even more. The Israelites looked forward to the restoration of Jerusalem and the temple, but we are promised a heavenly city, and the Holy Spirit lives among us even now. Israel awaited a mysterious Messiah, but we have seen Him, the Christ born of a virgin, crucified for our sins, raised from the dead, and ascended into heaven! Moreover, we know Him intimately and He knows us even better. We have seen how God keeps

His promises. When He says in Revelation 22 that we will see a city where the river of the water of life flows and where the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations, what can we do but rejoice? We do not need to shy away from suffering — it is no threat to the goodness of a God who promises such a complete peace and blessed life in the restored creation. Instead, we can bring our suffering before God with complete honesty, singing a joyful song as we hope for better things to come.

The Church is slowly beginning to develop a healthier approach to suffering. Contemporary hymns are engaging and responding to suffering and despair more and more. Pastors preach openly about mental health and the spiritual benefits of praying through the Psalms, which articulate our experiences, good and bad, far better than we can. Mercy ministries are receiving more attention from congregants and theologians alike. But there is a long way to go in repairing our broken culture. Fixing it begins with recognizing and articulating the problem, then looking to Scripture for models of holy lament. Americans are crying out for comfort from their troubles. Let’s answer their call.

Ben Kelley (CC’25) is a sophomore studying Political Science and Statistics. He appreciates literature, weird history, and the Midwest. You can email him at btk2117@ columbia.edu.

18 | vol. 10, no. 1

“Christians, then, ought to be joyful even when they cannot be happy.”

In the Midst of Death, We Shall Live

Allegra Nshuti

Igrew up in the church. My parents were Roman Catholic Christians. I would not say that their faith belonged to me at any certain point in time, but I was always happy to tag along when they went to church. It wasn’t really that we had a choice: we had to go to church on Sundays. We had to sing in the children’s choir and before each Mass; each one of us was given a coin or two to put in the woven baskets when the time of offering came. It took a lot of willpower not to keep the coins and buy candy afterwards! To put it in a few words, I was passive about it.

When I went off to boarding school, my passiveness to things partaking to Christianity, which seemed like an established routine for everyone, continued. I was enrolled in a priest school, and we had to go to Mass almost every day. I had gotten baptized at the age of 2, but then, all my friends were getting their other sacraments. I decided to join the Sacrament school too, hoping that, at least at the end of the year, I would get to have my family visit, bringing with them good food and congratulating me for my courage. I really want to say that this was not my sole reasoning, but it was. I got the Sacrament of Confirmation and the Sacrament of the Eucharist, my family came bringing with them banana cakes, and congratulated me for becoming a well-growing Christian. That is what Christianity meant to me for a big part of my life, until at some point everything changed.

At the end of 9th grade, I changed boarding schools. I was not very good nor attentive in class, so the Rwandan Ministry of Education appointed me to go study in a not-so-top-level nun school. It was a threehour trip by bus from my hometown and you could only have friends and family visit for 3 hours once a month. This did not bother

me in the slightest since I was already used to not seeing my family and doing my own thing. I remember vowing while sitting in the packed bus that I would make myself into a new person and write a different story on the blank page titled “Allegra’s A’ Level Years.” I remember being very determined, fueled by the hate and resentment I had for my old self; I had to be a different person, no matter what it cost me. I did become a different person, but it was nothing that I did.

In Psalm 127:3, David writes, “behold, children are a heritage from the LORD, the fruit of the womb a reward.” To those who grew up surrounded by a Christian community, this verse might be familiar. Children are a heritage from the LORD and should be consecrated to the care and service of the LORD God, Him who created them. Because of this, children born to Christian parents have the precious chance of growing up with the knowledge and fear of the LORD.

Like me, they attend service every other day, say their prayers before they eat, or any other variation of these acts of faith. They grow up being used to the Holy things of God, and rightly so. The Gospel according to Matthew records an incident where little children were brought to Christ so that He should lay His hands on them, a symbol of blessing (Matthew 19:13). The disciples tried to send them away by rebuking the people, but Jesus cried out, “Let the little children come to Me and do not hinder them, for to such belongs the kingdom of heaven.” This statement from the LORD informs us of our rightful duty to bring those who are born of us to the LORD for He demands that we do so; Christian parents, like my own, ought and must do so. Conversely, it is a bad thing to be a hindrance to anyone and keep them from seeing and coming to the LORD.

In addition, when talking about those who will believe in Him (His disciples), call-

ing them to be like children, He solemnly warns them (and us) saying, “Whoever receives one such child in my name receives Me, but whoever causes one of these little ones who believe in Me to sin, it would be better for him to have a great millstone fastened around his neck and to be drowned in the depth of the sea” (Matthew 18: 5-6). It is, therefore, necessary, and just for those who believe to always pray and teach their children things that pertain to their LORD and Savior.

However, they are dangers and snares that spring forth when righteousness is sought. Like in the Parable of the Weeds, where “a man sowed good seed in His field, but while His men were sleeping, His enemy came and sowed weeds among the wheat and went away” (Matthew 13:25). So, we should not sleep, O soldiers of Christ, until in our own hearts, “we gather the weeds first and bind them in bundles to be burned but gather wheat into [His] barn” (Matthew 13:30). Examine your heart, Christian, and see if your childhood Christianity — one you inherited — is not a mere flaunt and lie. For though it is encouraged, it can never be inherited. The path to Christ is one that you must start alone. See if you truly have the LORD as your Lord, not just a fact-of-life that your parents raised you up with. I say this because I was the same.

He was never mine until I begged and cried beneath His Cross, begging for a drop of His blood to fall on me and cleanse me of my sin. He was never mine, until like Pilgrim, I read and was convinced of the fatality of the burden I still carried even though I had received all my sacraments and recited all my prayers. He was never mine. He was never given to me by parents, even though I am thankful that through them I saw glimpses of an all-too terrifying fire that awaited to swallow up my perishing “pretty-good child”

The Witness | 19

soul. For, at the time, I did not know that as I sang and joyfully skipped to church, I was walking to judgment and that for every song of hope I heard, a thousand blades pierced my souls for I was not a partaker in that hope. No, I was condemned. And so, you might be. Therefore, “Examine yourselves to see whether you are in the faith” (2 Corinthians 13:5). The test is this, “we appeal to you not to receive the grace of God in vain” (2 Corinthians 6:2). If truly, you have received it.

No matter is as important to settle as this one, for it partakes of a life that will never end. A joy that will always be full, or unending torment. Yet, it is so easy to overlook, and think of it as folklore designed to make people afraid and submissive to authority. “We close our minds and spit back in the face [of one who calls out for repentance (John 1:23)], calling lies whatever is new to our ears and unfamiliar to our eyes, or maybe just seems too steep for our thinking to grapple on” (Apuleius 3).

Yet the clock ticks, time flies by, and the Truth of Old shall not wither with time, but He shall stand gloriously unscratched on that day, calling to Himself each soul for a judgment long due. The days are coming and are at hand where you will go the same way you came, alone and naked, a river before you that has swallowed up souls to Hades. But for those who believe in Him who walks on water, He who split the Red Sea, there is a hope that can only be described as glorious and merciful. We have hope that though we are weak, He is strong, and shall lay their hands in His and know that death has no sting, for through Him, death becomes the

gate that leads them to eternal life and glory. What hope is this? How wonderful, how glorious, that sinners are treated thus. But glory be to God, who loved the world and gave His only begotten Son for its redemption (John 3:16).

There is no bigger danger that I have encountered in the Western world than how death is so meticulously hidden from the eyes of the populace. It is so well hidden that when it does come, people are taken back by it. They tremble for a moment and the thought hits them, even if it is for a little while, “this could be me!” It is important to say that it not only could be you, but it also will be you. The Western world captures life as a series of well-planned steps. You go to school, get into a good university, have a career, have a family, raise your children, grow old, and then retire. But there is a step that is not discussed. Death.

It takes the awareness of the end to be able to live truly and knowingly. Knowing that “thee are not immortal,” and that though you spit at it, there is a spiritual world, a judgment at the end of this that religion and spirituality so boldly proclaims, but that the intellect of the unwise rejects. It is not ”media vita, in morte sumus,” as the nihilist so boldly cries out. The saving grace and mercy of Christ Jesus my Lord speaks of a truth that will not grow old nor kneel. It affords the believer the right to say this: “In the midst of death, we shall live.” Christian, “were the whole realm of nature [yours], they would be an offering far too small. Love this amazing, this divine, demands your soul, your life, your all.”

Allegra Nushti is a first-year student (CC‘26), originally from Kigali, Rwanda. She is infinitely grateful to God for His Son, and wishes to share what she knows of Him wherever the Lord wills her to go.

20 | vol. 10, no. 1

“

Examine your heart, Christian, and see if your childhood Christianity — one you inherited — is not a mere flaunt and lie. ”

The Witness | 21

Martyr Nature

Thomas Harris

Bounded by heaven, surrounding the damage, Endless evergreen hedge of divine protection, White and red roses, sown by the Sacraments, Budding from the Earth in untold dimensions.

Responding to those who express repentance, Harvesting arrows and guarding its entrances, Throwing gold idols straight off of the ledges, Stargazing angels did headstands on its edges.

The shout in scorn demands for her slow death. Thousands of thorns jammed into her forehead. The lost sheep decreed her a porcupine demon, The Pentecostal dove that descends onto Jesus.

22 | vol. 10, no. 1

The mystery of faith is like a mustard seed grain, An exercise of strength until her expiration date. What remains will decay around the end of days, The misery of pain flaming martyr nature’s fate.

Taken for granted and treated with insignificance, An empty space on her back to carry her cygnets. The sting of the honey bee surrenders everything. Her bravery is her form of dedication to the King.

Pure deer that pan the water get sold to slaughter. Antlers ravaged the traps that fooled her daughter. Endangered elephants hunted down for their ivory For the sake of completing an elaborate altarpiece.

Thomas Harris (SEAS'25) is a senior studying Applied Mathematics. He is also a poet currently working on his second collection “Star Sweeper.” You can reach him at thh2117@columbia.edu.

The Witness | 23

Vintage culture

Abehavior becomes culture the moment it possesses power and influence over our habits, social relationships, and most importantly, our conscience. If it is hindered, suppressed, or thoroughly prevented from possessing such an impact, then is it really culture, or simply a context specific behavior performed when desired? Alas, as we attempt to identify culture in the present day, we are at pains to grasp something which holds such sway over us. Many of the spiritual practices and belief systems we encounter in our coursework or pursued out of general curiosity are often presented to us through a looking glass. Theologians, secular philosophers, economists, and political theorists are rendered as mere artifacts in a museum, displayed solely for our study and observation. What follows is an appetitive behavior, a study solely for the sake of accumulating and consuming knowledge. A broader discipline or framework to orient the purpose of our study beyond knowledge is lacking. As a Catholic undergraduate majoring in economics, I often try to determine how ideas encountered in my coursework seriously challenge, complement, or justify my faith and morals. Fellow Christians I know do the same. After all, our university defines economics as the study of how society allocates its resources and the

consequences of such decision-making.1 It is the latter responsibility which seems to draw religious concerns most fervently. Examining the outcomes of societal decisions elevates our attention to higher considerations, presenting moral issues to our conscience when evaluating consequences appearing neither apparently good nor evil. In an annual Wall Street Journal Christmas editorial written in 1949, Vermont Royster writes,

“There was the tax gatherer to take the grain from the fields and the flax from the spindle to feed the legions or to fill the hungry treasury from which divine Caesar gave largess to the people… There were executioners to quiet those whom the Emperor proscribed. What was a man for but to serve Caesar?... most of all, there was everywhere a contempt for human life. What, to the strong, was one man more or less in a crowded world?”2

In our modern world, capitalism incentivizes, under the penalty of destitution, the spending of our time on its various labors and goods. As much as one may be

1 “CC Bulletin Economics,” https://bulletin.columbia. edu/columbia-college/departments-instruction/economics/.

2 Vermont Royster, “In Hoc Anno Domini,” Wall Street Journal.

free to choose or decide for others investment allocations, employment opportunities, or degrees of education, we are free to choose mainly what capitalism incentivizes or devalues through its prices and rates of return. Is capitalism, as we observe it today, our new Caesar? What, to the wealthy, is one man, one child, more or less in an affluent, efficient world?

Great thinkers past and present often narrate a state of nature in their writings to elucidate the purposes of both inanimate and animate things. A state of nature serves the purpose of examining what reality was like before a certain thing was created or introduced. We examine what deficiencies, obstacles, or questions confronted the state of nature and predated the thing in question. If something is new to a state of nature, we assume it was created or introduced to solve or counter an issue or question. While there are many cases where inanimate objects were created by chance or accident such as the microwave oven, penicillin, dynamite, etc., many of these inventions and innovations retain a use-value that bestows on them a purpose and meaning to encourage their perpetuation after their discovery. These uses may not only be material, but may also be religious, political, or sentimental. However, a state of nature supposes nature itself exists already. As Christians, we

The Witness | 25

Gustavo Alcantar

believe nature itself to have been created by God. Our origin point in examining the purpose of things should therefore be God himself.

Society’s domination by the market is thus not a product of man’s nature, since humanity’s natural inclination is not to barter. This was not the Creator’s command. Rather, bartering is an artificial means to satisfy mankind’s essentially social nature; it serves to increase one’s social status or maintain social relationships. If we are essentially economic beings, human activity would have been oriented from the Beginning towards what achieves maximum exchange/monetary value. This understanding justifies the rendering of human activity, namely labor, as first and foremost merchandise in the capitalistic context. It is something bought and sold by every human being.

Yet, understanding labor in this way regards its social benefits as secondary and irrelevant in a wealthy world. This commercial redefinition of labor constitutes a reduction of society, which should fundamentally be based upon the social relations which unite individuals and are meant to frame one’s actions, one’s labor, towards higher things. When social bonds are subordinated to the market, a specter of meaninglessness haunts us. We are no longer governed by unifying, edifying, and natural social frameworks but rather individualistic, transactional, economic ones. Hence, we often struggle to identify larger social frameworks in our modern world which bind us together and which lie outside commercial principles, those which cost nothing but our devotion. Those who ultimately suffer from such a lack of overarching social principle seem to be the poor, who are at an economic disadvantage but cannot rely on society at large. They must beg for private charity, relying on the generosity of those who adopt, whether by faith or secular altruism, some social morals which persuade them to administer to the poor. Hence the paradox of Margaret Thatcher, “Who is society? There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families and no government can do anything except through people and people look to themselves first.”3

3 Thatcher, Margaret. “Interview for ‘Woman’s Own (No Such Thing as Society).’’ [Margaret Thatcher Foundation: Speeches, Interviews and Other Statements.

The human person, with his or her inalienable rights, is by nature open to relationship. Implanted deep within us seems a call to socialize and interact with others. To do otherwise seems unnatural, a rejection of our gift of life and the call to be stewards over the creation God has entrusted to us. In the first two chapters

“Today there is a tendency to claim ever broader individual — I am tempted to say individualistic — rights. Underlying this is a conception of the human person as detached from all social and anthropological contexts… Unless the rights of each individual are harmoniously ordered to the greater good, those rights will end up being considered limitless and consequently will become a source of conflicts and violence.”5

Indeed, underpinning modern economic theory is the assumption that human beings have insatiable desires. The common quip taught to remember this is the catchphrase, “More is Better.” While we must understand that human concupiscence may tend towards the cardinal sin of greed, it should not be catered to. Instead, modern microeconomic theory is an assortment of methods optimizing resources to best satisfy this desire. Of course, there is mention in our coursework of “negative externalities,” negative consequences of allowing unrestrained economic competition to take place. What these externalities actually are, in an otherwise increasingly objective field, is yet very much in dispute.

of Genesis, the Creator remarks how all that He has created is good, with one exception. He remarks, “It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him a helper fit for him.”4 While this is the widely understood reason for the creation of women, it also seems to point us towards an important teaching on what God envisions humanity must be. For this reason, Pope Francis has remarked,

London. 1987].

4 Genesis 2:18.

A final recourse we may have to identify a binding social framework may be found in law. Where the “good” is a societal end, rather than society itself, there are laws established on wisdom and virtue towards such end. The law, then an accessory to a moral code, should be a method of self-evaluation as to whether one is following what is “good.” It should not be a means to solely evaluate one’s actions as to whether someone else is harmed or offended. Society’s increased commercialization is a demonstration of the latter, necessitating so much concern for others but to advance our own vanity, economic interest, or avaricious curiosity, that deeper moral reflection would cease. Struggle for a societal good is restrained in favor of keeping an economic, societal peace and equilibrium. Even David Hume, a staunch proponent of early market capitalism, remarked, “what we frequently performed from certain motives, we are apt likewise to continue mechanically, without recalling on 5 “Address of Pope Francis to the European Parliament,” https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/ speeches/2014/november/documents/papa-francesco_20141125_strasburgo-parlamento-europeo.html.

26 | vol. 10, no. 1

every occasion, the reflections, which first determined us.”6 Some, like Hume, believe law to have a merely instrumental purpose in securing societal maintenance. Illegal actions are deemed unlawful insofar as they disrupt society. While this seems like a novel idea, what is excluded from this belief are laws which constitute moral ends. For in

ciety itself, not a societal good. Law, having lost a moral mandate, is no longer a legislated moral code orientating society toward what is deemed “good.” If law, therefore, is society’s instrument, then it should also please society beyond maintaining order. Capitalism seemingly produces luxury and refinement capable of bestowing greater societal pleasure than an ascetic legal order founded on natural morality. Thus, the law works instrumentally. It becomes subservient to the capitalism which greatly satisfies the appetitive, recurring, material desires of our society. When this alteration takes place and no precedence is given to moral ends, so too does anything else associated with such ends. Since the interest and happiness of human society are seemingly aligned with the technologies, flavors, and trinkets of capitalism, then this framework becomes the “ultimate point” where all previous custom and law must end.

such framework, laws which legislate moral ends are therefore not considered laws, since they concern themselves with ideals rather than instructions of practical execution. A legislated moral code is not included within this calculus because such a framework likely entails what are deemed impractical metaphysics or naïve ideals. By reframing a legal system as such, by excluding legislated moral ends, law is instrumentalized towards a productive, practical end benefitting so-

David

What results is a gratification of a consumerist, individualistic solitude which seems to stray away from God’s intention. Its end is to expand our access to privacy by enforcing peace sometimes at the expense of righteousness, incentivizing consumption instead of sacrifice, and prioritizing privatized wealth over intentional charity. While it is certainly difficult to conceive of ways in which we may reconstruct, reform, or revolutionize society to halt this rate of change, it is always our duty to orient our conscience to God. While we may find ways to enforce custom and incentivize a good life, we should never attempt to control the deliberate actions of others. This is true regardless of whether the law is material or moral in nature. The law and framework of society are made up of incentives and consequences but are not individual decisions or thoughts already made. Therefore, the importance of prayer and reflection must be emphasized to orient our lives toward God, others, and the universal Church. Something as simple as this remedy is enough to make us cognizant of the perverse incentives which may pervade our commercial society, and make us more attuned to higher things.

The Witness | 27

6

Hume, An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals, [Oxford University Press, 975], p. 203.

Gustavo Alcantar (CC’24) is a junior studying Economics. Contact him at gia2107@columbia. edu.

Finding Rest in Stress Culture

Ashley Kim

I’ve always felt like I belonged in New York instead of Southern California. A host of little things about my hometown irk me: people walking slowly, sand at the beach, flip-flops in public. More broadly, I’m compatible with a lifestyle that’s fast-paced and goal-oriented, not laid-back. What’s the use of sunbathing? Or smelling the roses?

In other words, my personality is a stereotype of Columbia’s stress culture. I’m not alone: I know countless other students, like me, are chronic perfectionists and workaholics, whether or not we admit it — and whether or not we see such tendencies as harmful. But recognizing the presence of stress culture isn’t revolutionary; I’ve heard the term in relation to Columbia long before stepping foot on campus. Labeling a tendency isn’t enough. It isn’t enough for me to realize that perhaps one of the reasons I was drawn to Columbia was because of its stress culture. Why was a self-destructive environment attractive to me in the first place? Why are we so aware of

our own dangerous inclinations, yet unable to change? And what is it about stress that makes it so irresistible?

We tend to think about stress culture like an external threat, but it’s actually more like an addiction. The danger lies not only in outside pressure, but internal compulsion. It is much the same with other addictive patterns of behavior, including eating disorders.

When I tell people I struggled with an eating disorder, multiple people have responded, “Your self-control is just too strong.” Or, “My self-control isn’t strong enough to have that problem.” I understand the reasoning. If self-control is simply the ability to rein in impulses and desires, such as hunger, anorexia must be self-control gone to the extreme. It is true that starving requires a certain level of restraint around food that’s easily confused with self-control. But to paint a simple spectrum with, say, anorexia on one extreme and binge eating on the other, is to fatally misunderstand self-control, as if the

28 | vol. 10, no. 1

solution to anorexia is to engage in a little binge-eating and the solution to binge-eating is to become a little bit anorexic.

Rather, the primary issue in both forms of disordered eating is a loss of self-control. In my descent into a full-blown eating disorder, I reached a certain point where scrutinizing my body and counting calories were no longer deliberative decisions but compulsions driven by fear. Though a part of me felt I had gained a sense of control over my body, in truth, I was being compelled — controlled — by fear. And this fear arose out of my desire to be beautiful in the eyes of the world. Obeying your own desires is not freedom when those desires are ultimately suicidal.

The Bible describes my experience better than I can: “But each person is tempted when he is lured and enticed by his own desire. Then desire when it has conceived gives birth to sin, and sin when it is fully grown brings forth death” (James 1:14-15). What was the root of my obsession with losing weight? The answer is self-control — not an overabundance, but a lack. Hence, recovering meant restoring a biblical sense of self-control.

Instead of succumbing to “the desires of the flesh” (Galatians 5:17), the Christian is called to a new and better way: “But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control; against such things there is no law” (Galatians 5:22-23; emphasis added). A biblical understanding of self-control is a refusal to give in to our natural desires. It is a quality born out of the work of the Holy Spirit and thus, consistent with God’s design.

Unmoored from the Word of God, our conception of self-control quickly becomes blurry. If we accept a worldly definition, such as, for example, “the ability to control one’s emotions, desires, and reactions, esp. in difficult situations; control of oneself,”1 gaps of subjectivity remain. While I was deeply entrenched in an eating disorder, almost nothing was more frightening than gaining weight. I wasn’t stupid; I knew that continuing to starve myself would only lead to negative health effects and eventually, if nothing changed, death. Yet as long as I dwelled on

1 Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), s.v. “self-control, n.” www.oed. com/view/Entry/175174?redirectedFrom=self-control.

an incomplete view of self-control, I could convince myself that my physical health was a necessary sacrifice to achieve satisfaction with my body. Without an objective standard of right and wrong, beneficial and harmful, I found no logical reason to recover. If I was certain that my personal happiness depended on being underweight, why was it so bad to harm myself? Wasn’t my happiness more important than my physical health?

Even worse, popular culture sends contradictory messages. Though eating disorders are generally regarded as detrimental, and though people generally agree that health and wellness are more important than outward beauty, many models and celebrities with the “ideal body” are underweight or otherwise unhealthy. To be sure, culture is not homogeneous, and it may very well be two distinct groups promoting these conflicting ideas. But perhaps such a dissonance is part of the reason why more anorexics die of suicide than starvation.2 The world may offer two choices — starve or recover — but neither can promise holistic redemption, a recovery that cares for both body and soul.

True recovery, for me, only became possible once I saw that self-control is not the sacrifice of myself for the sake of my desires, but the sacrifice of my desires for the sake of a Savior who demonstrated his superior love by dying for me. Only then could I be free from hopelessness and fear.

Jesus also offers a better way for those struggling with stress, anxiety, and weariness.

Most of us at least understand that overworking is unsustainable in the long-run. Even if you could, hypothetically, pull two consecutive all-nighters in Butler and still ace your midterm, almost no one would consider it wise to try. For this reason alone, it’s worthwhile to invest in at least a few hours of quality sleep. You need rest to work. Yet the driving motive is still achievement: go to sleep to be rested to have a clear mind to perform to succeed. Rest becomes another task on the way to success. The implication is still, ultimately, that your fulfillment depends on achievement.

How does Jesus respond to our achievement-driven, results-oriented culture?

2 Bettina E. Bernstein et al., “Anorexia Nervosa,” Medscape. WebMD, February 28, 2020, emedicine.medscape.com/article/912187-overview#a6?reg=1.

“Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light” (Matthew 11:28-30). The rest that Jesus promises is an unshakable inner rest that we can work out of, not a transient, circumstantial rest that we must work to achieve. It is a rest that began on the cross, when Christ, having borne the sin of the world, proclaimed, “It is finished” (John 19:30). Christ’s finished work means that in him, we are completely and eternally forgiven, accepted and loved, and adopted into the family of God, never to be cast out. All who come to Jesus are freed from the insatiable demands of accomplishment because it is his work, not ours, that grants forgiveness and reconciliation with God.

This does not mean that our work is stripped of meaning. On the contrary, we are given a new purpose, a new yoke that is easy and a new burden that is light — glorifying God. Often, this translates into continued faithfulness to the seasons and stewardships he has given us, including striving for excellence in schoolwork. Yet it is not a work that hopes to one day enjoy the approval of God but a work that springs out of an enjoyment of his gracious love and desires to honor him in everything, including both toil and rest. Self-control, then, is not found in the workaholic. We do not push ourselves too far because our self-control is too strong, but because it is too weak.

Why do we willingly give ourselves to stress culture? It is because we are lured by our own desire for achievement. Desire begets fear, and fear is why I sometimes spend hours tossing and turning in bed, anxious about all the work that remains unfinished. But I am able to prioritize taking care of my God-given body because I know that he is both sovereign and loving. It is difficult to rest in such a truth because it takes humility to recognize my dependence and his greater sovereignty. Yet humility is freeing, allowing me to lay down my desire for success and rest in the care of my heavenly Father, who knows already what I need and promises to provide for me.

Consider the full context of a frequently quoted passage: “Humble yourselves, therefore, under the mighty hand of God so that

The Witness | 29

at the proper time he may exalt you, casting all your anxieties on him, because he cares for you” (1 Peter 5:6-7). How can you practically cast all your anxieties on Him? Not by abstractly imagining Christ carrying your burdens, but by humbling yourself. When we see the glorious grace of God, when we become aware of our own need, and when we recognize that control is not ours in the first place, we will find rest for our souls. When, armed with self-control against our own deceitful desires, we humble ourselves before Christ, we will discover a Savior who is far wiser, gentler, and greater than we are — a Savior who leads us into true and lasting rest.

30 | vol. 10, no. 1

Ashley Kim (CC’26) is a freshman in Columbia College majoring in English.

“ “

The rest that Jesus promises is an unshakable inner rest that we can work out of, not a transient, circumstantial rest that we must work to achieve.

contra christendom?

Benjamin Brake

Part I: The City of God and the City of Man

Despite the decline in Christian theist influence in Western modernity, some subcurrents in Christian thought today have nevertheless imagined all sorts of schemas for the enforcement of “Christian society.”1 Yet even in these contrived utopian imaginings, a certain intellectual problem emerges for the Christ follower: how does Christian practice, essentially defined by Christ’s eternal promise of our reconciliation with God via salvation, relate to the motivations of temporally-bound societies? To clarify, I take culture to be heteronomous onto its members, broadly speaking. By heteronomous, I refer to motivation for action which is externally imposed and “topdown.” That is to say, an individual who participates in a culture will be affected by that culture as they operate within it. Insofar as this occurs, the individual is rendered heteronomous, rather than autonomous, with respect to culture. This influence of culture is most obvious in the role of the state government, whose influence takes the form of political coercion. This heteronomous influence is also present, though perhaps more subtly, in civil society, where cultural norms and social mores influence the identity and choices of given members. The specific question remains as to what degree Christianity can be conceptualized in such heteronomous cultural terms while remaining true to its essence. Put another way, can there be a “Christian Culture”? I hold that Christian practice — due namely to its recognition of 1 Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, [Harvard University Press, 2007].

the secular realm, its categorical-apocalyptic conception of history, and its emphasis on the individual’s personal relationship to God — implies a trivialization of temporal motivations. Insofar as this is true, Christianity is not defined according to cultural heteronomous motivations, and so is not utilizable or justifiable by them, whether for political or social aims.

Christianity has a longstanding recognition of the legitimacy of the secular realm, where secularity is defined as absence of religious heteronomous imposition. Indeed, secularity is cemented in the essential Christian distinction between the heavenly and earthly realms, as famously instantiated in the words of Christ, “render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.”2 It has subsequently developed throughout much of Christian intellectual history, perhaps most notably in Augustine’s distinction between the “City of God” and the “city of man,” and likewise in Luther’s “Two Kingdoms” doctrine. And even at the height of Western Christendom in the Middle Ages, when this distinction was perhaps most dangerously blurred, there lingered still a perceivable engagement, albeit tension, between the realms of the secular and the Church, as so perceived (i.e. the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy), such that all of Western “Christian society” had still to struggle with this troublesome bifurcation.

Granted, insofar as Christianity is not Manichaeanism, insofar as the sovereign God reigns without a metaphysical chal-

2 Matthew 22:21.

4

lenger — and thus all other power, whether demonic or earthly, is but merely deviation from His will — then any and every “city of man” is ultimately subject to God’s will.3 What’s more, insofar as Christ universalizes the Good News, not only to the Jews, but to the Gentiles as well, then we expect and hope for some future history wherein this City of God is actualized for us all, as individuals and in relation to each other (i.e. as individuals relating in aggregate to form Christ’s Bride, the Church.)

Nevertheless, this future promise is clearly presented as distinct from the present earthly realm. Just as we delineate the City of God from the city of man, so we admit of distinction between the present history and the distant New History (the New Heaven and New Earth), with the latter only to emerge after Christ’s triumphal return. We must make no mistake: this world, at present, is not our home.4 Whatever might come to pass at some unknown future point regarding the final “advancement of the kingdom,” it is not actualized in earthly terms in our immediate history. A whole apocalypse stands between us and then.

Certain minority apocalyptic schools of thought such as the postmillennialists might challenge this precise point, insofar as they render the apocalypse causally dependent on our history here and now, and temporally connected to us in sequential, chronological terms. As in, they suggest that we act here and now, and so we usher in the City of God by virtue of our action. Besides the fact that their view is purported on a 3 Romans 13:1.

1 John 2.

The Witness | 31

unique interpretation of select verses — an interpretation which is highly debatable and novel in the broad swathe of Christian history — their occasional insistence on its alleged practical social and political implications suggests a deeper motivation of such framework. Their origin of motivation is not only in biblical interpretation of Revelation 20, but additionally concerns an implicit reorientation toward (and thus, erroneous obsession with) historical immediacy, with our earthly home as though it were our heavenly home.

Put simply, even if the apocalypse were to be ushered in after a string of Christian-dominated historical events manifesting in a “Golden Age” — where some percentage of the world’s humans were to become self-professed Christians, and/or some arbitrary percentage of modern governments were to be self-professed “Christian states” or members of a “Christian empire” (whatever such a strange concept might mean), there is no telling when or for how long such a condition would need to take place before ushering in the apocalypse, nor how many near attempts and failures there would actually be between the first approach towards utopic Christian perfection and the last. Because of the lack of any known historical endpoint, because we don’t know when Christ will return, use of such consequentialist logic to justify any given particular cultural movement is erroneous. Obsession with historical immediacy cannot rid us of that Christian apocalyptic marker: the categorical distinction between New Earth, on the one hand, and the present immediate earth, on the other.

For a time, this world is under the dominion of the Devil, and its inhabitants depraved.5 Indeed, every city of man is, to greater or lesser degrees, a city of Cain.6 And for those who wish to identify any visible Church as an analogue to Jerusalem, let us not forget that Jerusalem, too, for its days, was all too often a city of Cain in its tendencies towards depravity. This is our history, and the one in which Christ distinguishes Caesar’s dominion from God’s, wherein the Holy Spirit is sent to dwell in us individually, but Christ’s reign is yet to be instantiated externally. In

5 Ephesians 6:12, Psalm 51, Romans 3:20-23.

32 | vol. 10, no. 1

6 Fr. Matthew Baker, “The City of Cain and the City of Jesus,” https://www.eighthdayinstitute.org/the-city-ofcain-and-the-city-of-jesus.

the meantime, Christ’s Gospel trivializes all ambitions concerning historical immediacy.

It should almost go without saying, thanks to the apostles, that we Christians are not the same people as the ancient Israelites. Yet certain groups such as the “reconstructionists” seem to muddle this distinction, as if God’s particular mandates to the people of Israel in the Old Covenant — namely concerning theocratic heteronomous social governance — were unequivocal statements of some universal politik across Old and New Covenants.

To reiterate, our conception of the secular is informed by Christ who universalized salvation for us, just as he brought to light this distinction between the earthly and heavenly realms. The Christian is not so lucky as the ancient Israelite to have our particular political structure spelled out for us, nor our kings handed to us, nor our particular Levitical priesthood appointed for us. Instead, Christ is our King and our Melchizedekian High Priest all in one.7 And yet Christ is not here with us at present. So, we are left to engage the historically-immediate realm on secular terms.