Voyages

Chronicles of the Cruising Club of A merica

Chronicles of the Cruising Club of A merica

Welcome to another edition of Voyages!

This collection of articles chronicling CCA members’ voyages on the sea brings many fresh, engaging, and thoughtful perspectives.

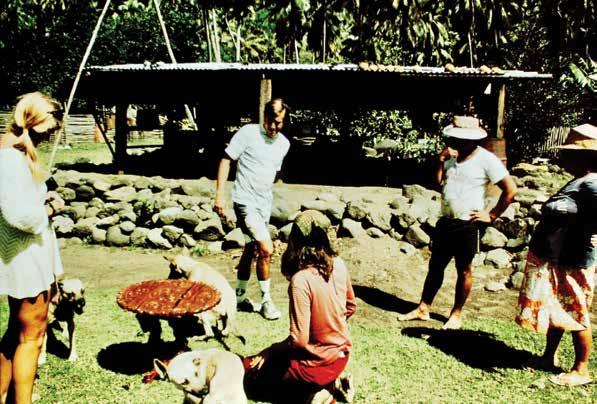

Nico Walsh retraces the wake of legendary sailor and explorer Eric Hiscock in Scotland, where our members will soon join the Royal Cruising Club, Clyde Cruising Club, Irish Cruising Club, Western Highlands Yacht Club, and Ocean Cruising Club for the first CCA Scottish cruise since 2010. From the other side of the planet, Robert Hanelt recounts his family’s 1970s voyage aboard their Skylark in French Polynesia. Sheila McCurdy offers a teaser from her upcoming book on the history of the CCA, High Seas and Home Waters, with tales of club leaders, members, and frivolity following World War II. Jil Westcott and John Bell summarize a wealth of information on various weather phenomena in the Mediterranean.

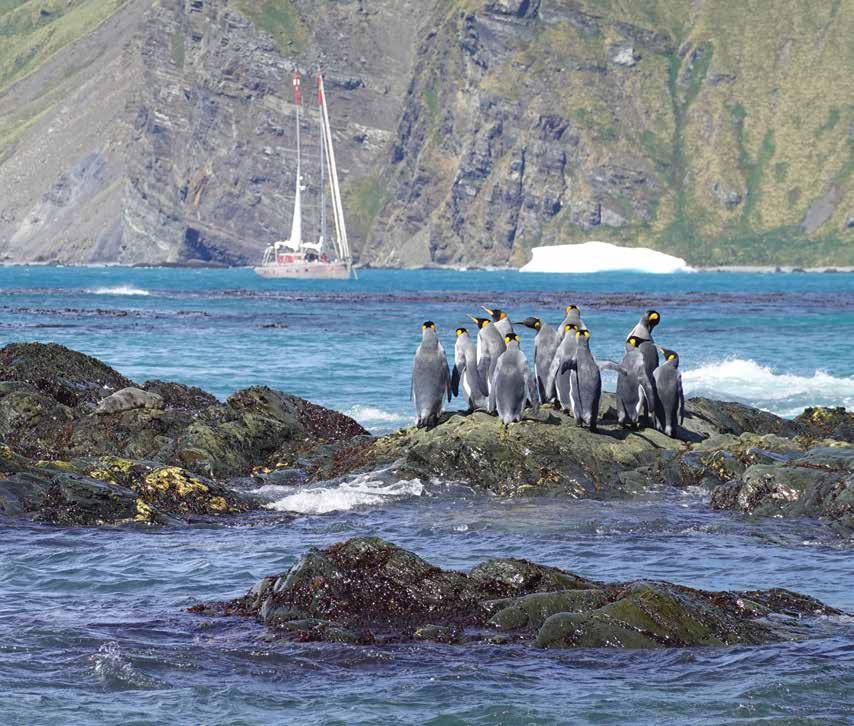

Bill Barton logs his multi-year endeavor to return to Inuit communities in Labrador, despite mechanical challenges and other setbacks. Farther north in Greenland, David Conover reports on a rendezvous with the legendary arctic exploration schooner Bowdoin. From the opposite end of earth on South Georgia Island, Skip Novak blends history, science, and seamanship in his narrative about a scientific expedition to survey wandering albatross populations. You’ll be amused by author R.J. Rubadeau’s recounting of his voyage to the outer reaches of Chile, where disaster seemed to be lurking around every headland. Prepare to be amazed by the high-latitude adventures of 2024 CCA Blue Water Medalist Liev Poncet, written by Ellen Massey.

Melissa Hill recounts sailing with her husband and two young children from the Pacific across the Indian Ocean to South Africa. The Pacific is also the setting for Bill Strassberg’s account of meticulously analyzing and repairing a defective propeller in the Galapagos and for Behan Gifford’s report of assessing major rudder damage on Johnson Atoll, a remote

island that cannot be accessed without U.S. Air Force authorization. Simon Currin, immediate past commodore of the Ocean Cruising Club, shares a wonderfully insightful story of his recent cruising in the Tuamotu archipelago.

Lydia Mullin, onboard reporter aboard the ill-fated Alliance in the 2024 Newport Bermuda Race, brings you into the midst of that near-disaster, where the excellent preparation, training, and seamanship of both rescuers and evacuees paid off with no major injuries or loss of life. Gary Forster shares his story about bringing younger, less-experienced sailors aboard for offshore experience in the Block Island Race. Jill Hearne reminds us that voyaging under power is very much part of the fabric and history of the CCA, and comes with some welcome advantages, especially as we age and wish to continue our adventurous use of the sea.

You will enjoy book reviews of Randall Peffer’s coffee-table book about the maxi Windward Passage during the golden age of maxi racers by R.J. Rubadeau; Lin Pardy’s story of her life afloat and dealing with life’s changing currents by Gretchen Biemesderfer; and Skip Novak’s latest book on his 50 years of sailing the world’s oceans by Peter Plumb.

This summary does not do justice to the time, effort, and inspiration these authors and editor Dan Biemesderfer have put into this issue, but I hope it will entice you settle in your favorite chair and delve into their stories. You’ll be richly rewarded and glad you did!

Finally, Elizabeth and I send our best wishes to you wherever your sailing adventures take you!

The Cruising Club of America is among North America’s foremost resources on offshore cruising and racing and, together with the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club, co-organizer of the legendary Newport Bermuda Race. The club is comprised of more than 1,356 accomplished ocean sailors who willingly share their cruising expertise with the greater sailing community through books, articles, blogs, videos, seminars, and onboard opportunities. Ocean safety and seamanship training through publications and hands-on seminars is a critical component of the club’s national and international outreach efforts. The club has 14 stations and posts around the United States, Canada, and Bermuda, and CCA members are actively engaged with the next generation of ocean sailors as they look forward to the club’s second century of serving the offshore sailing community. For more information about the CCA, visit cruisingclub.org.

Bermuda * Boston * Buzzards Bay Post * Gulf of maine Post * narraGansett Bay Post

Bras d’or * ChesaPeake * essex * florida * Great lakes new york * PaCifiC northwest * san franCisCo * southern California

cruising club officers

Commodore – John R. Gowell

Vice Commodore – A. Chace Anderson

Secretary – Patricia Ann Montgomery

Treasurer – Kathleen M. O’Donnell voyages editor

Voyages Editor – Daniel R. Biemesderfer voyages@cruisingclub.org voyages committee

Editor of Final Voyages – David P. Curtin (BOS) Past Issues Manager – Cindy Crofts-Wisch (BOS/BUZ)

Editorial Advisors: Dale Bruce (BOS/GMP), Doug Bruce (BOS/GMP), Lynnie Bruce (BOS/GMP), John Chandler (BOS/GMP), Doug Cole (PNW), Max Fletcher (BOS/GMP), Bob Hanelt (SAF), Cameron Hinman (PNW), Amy Jordan (BOS), Charlie Peake (NYS), Krystina Scheller (BDO), Brad Willauer (BOS/GMP)

editors emeritus

Alfred B. Stamford, 1962-1974; Charles H. Vilas, 1974-1988; Bob and Mindy Drew, 1988-1994; John and Nancy McKelvy, 1994-1999; John and Judy Sanford, 1999-2002; T.L. and Harriet Linskey, 2002-2010; Doug and Dale Bruce, 2010-2017; Zdenka and Jack Griswold, 2017-2021; Amelia and Robert Green, 2021-2024 design and layout

Daniel R. Biemesderfer; Claire MacMaster, Barefoot Art Graphic Design; Tara Law, Tara Law Design; Hillary Steinau, Camden Design Group proofreading

Daniel R. Biemesderfer; Virginia M. Wright, Consultant; Editorial Advisors

printed by

J.S. McCarthy Printers, Augusta, Maine cover photo

Tazzarin and iceberg in Labrador – photo by C. Newhall

copyright notice

Copyright 2025, The Cruising Club of America, Inc.

Copyright 2025, respective author(s) of each article, including any photographs, drawings, and illustrations. No part of this work may be copied, transmitted, or otherwise reproduced by any means whatsoever except by permission of the copyright holders.

4 Destination Disko Bay by David Conover, Boston, Gulf of Maine Post

18 Eulogy for Alliance by Lydia Mullan

28 Pulling Your Prop in Exotic Places by William Strassberg, Boston, Gulf of Maine Post

36 Rachas in Estero Las Montanas by R. J. Rubadeau, Boston, Gulf of Maine Post

44 South Georgia Albatross Survey by Skip Novak, Great Lakes Station

54 Crossing the Indian Ocean by Melissa Hill, Great Lakes Station

62 Actually It’s Not Dark Over Here by Jill Hearne, Pacific Northwest Station

68 Chinese Bread and Chinese Fair in French Polynesia by Robert Hanelt, San Francisco Station

74 Tazzarin — North to Nunatsiavut: A Voyage to Newfoundland, Labrador and the Inuit Lands by Bill Barton, Boston Station

86 Tuamotu 2024 by Simon Currin, Boston Station

92 Rudder Woes on a Micronesian Detour by Behan Gifford, Pacific Northwest Station

100 Channeling Eric Hiscock by Nico Walsh, Boston, Gulf of Maine Post

108 Weather for Cruisers Heading to and in the Mediterranean by Jil Westcott and John Bell, Boston, Naragansett Bay Post

116 Pay It Forward: The Block Island Race 2024 by Gary P. Forster, New York Station

122 A Profile of Our 2024 Blue Water Medalist, Solo High-Latitude Sailor and Southern Ocean Circumnavigator Leiv Poncet by Ellen C. Massey, Boston Station

130 History of the CCA – History of the CCA After World War II by Sheila McCurdy, Boston Station

134 Book Review – On Sailing — Words of Wisdom from 50 Years Afloat by Skip Novak

Review by Peter S. Plumb, Boston, Gulf of Maine Post

135

Book Review – Westward Passage: A Maxi-Yacht in Her Sixth Decade by Randell Peffer

Review by R. J. Rubadeau

136 Book Review – Passages: Cape Horn and Beyond –Sailing Through Life’s Changing Currents by Lin Pardy

Review by Gretchen Dieck Biemesderfer, Essex Station

138 FINAL VOYAGES Salutes to departed members. Edited by David Curtin, Boston Station, Buzzards Bay Post, and Daniel Biemesderfer, Essex Station 158

On this expedition, the past does not leave all at once, nor does the future arrive at once.

My Good Hope 56-foot aluminum sloop ArcticEarth is meeting up with the 103-year-old Arctic research schooner Bowdoin today on a dock in Ilulissat on the western coast of Greenland, 220 miles north of the Arctic Circle. We are preparing to sail farther north into Disko Bay as

By David Conover, Boston & Gulf of Maine Post

a two-boat convoy for several days. The mood is keen excitement and curiosity all around. In addition to the joys of being on a small boat in these waters, I have a job to do, a commission from the Maine Maritime Academy (MMA) to record digital still photographs and motion-picture video of a timeless icy

The seal-hunting competition begins and ends on the rocks in front of the Lutheran Zion Church. Built in 1779, it is the oldest church in Greenland.

seascape and the Bowdoin, the oldest active Arctic research boat in the world and official sail vessel of the state of Maine, doing its thing. Ten rapidly seasoning students and a professional tall-ship crew are aboard the Bowdoin, ably led by Captain Alex Peacock. They are the most recent of the MMA staff, students, and

academy supporters to have cared for this vessel over the last third of its noteworthy life. Onboard ArcticEarth as expedition leader, I have assembled a naturalist and Arctic writer, an environmental lawyer, a retired professor and former captain of the Bowdoin, and our skipper, Magnus Day, and his mate, Julia Prinselaar.

Ilulissat is 1,900 miles away from the boats’ home waters of Penobscot Bay, Maine, but both places are within one oceanic region, the northwest Atlantic. I like to think of Baffin Bay and the Gulf of Maine as the same neighborhood in the context of the whole planet. In that spirit, my general question on our own travels back and forth between the two is “what are the local Arctic happenings that have global resonance?” ArcticEarth is beginning the fourth mission of the summer, one of the 22 expeditions we have hosted since launching our specialty charter operation in 2020.

Today is June 21, Greenland National Day as well as ullortuneq (the “longest day of the year”) for the Inuit and others who live here. The occasion has been maintained as a day of celebration and identity by Greenland ever since its island people began navigating a course away from Denmark and towards self-rule in 2009. Among the festivities in town today, residents are boarding the Bowdoin to look around and take a step into the past. With their iPhones, they take pictures of the sails, the ice-bucket lookout aloft, the high bow, and other special features for this purpose-built boat. One hundred years ago, residents of Ilulissat visited the same vessel, captained by Donald MacMillan, and were curious and intrigued by his collection of “modern” scientific and media equipment. Perhaps their curiosity in the 1920s — their step into their future — was a crossroad with those visiting the Bowdoin today. Back then, the Ilulissat locals were almost exclusively Inuit who hunted and fished from qajaqs (kayaks). Today, in the era of the new Arctic, the locals are a mix of Inuit, Danes, Filipinos, South Africans, and Sri Lankans, many drawn from the global economy as laborers and managers to construct one of three international airports on the west coast of Greenland that will soon host direct flights to and from the United States and Europe.

Earlier this morning, before the Bowdoin arrived, I was up on the hill in town with current shipmate Andy Chase. We first met in the early 1980s when Andy sailed with the Sea Education Association (SEA) as a third mate on the well-known Westward in the early ’80s, and I was a slightly younger student learning

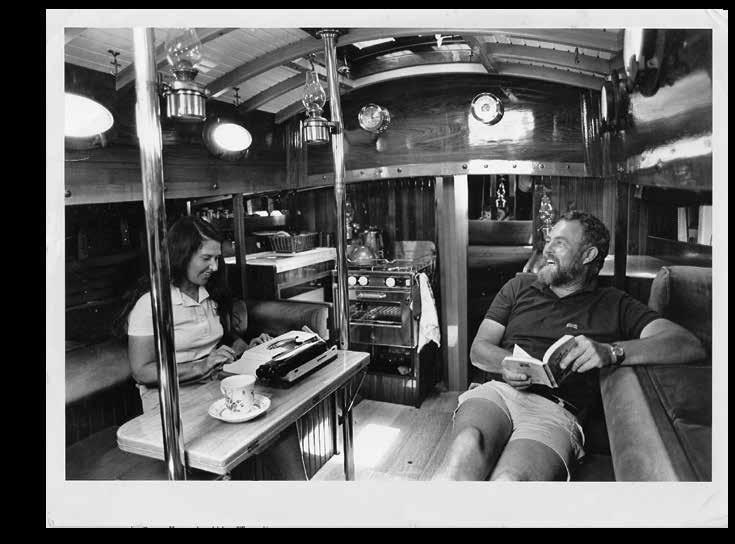

celestial navigation and researching a term paper in the archives of the Mystic Seaport Museum. The topic of the 20-pager was — ironically — the Arctic schooner Bowdoin, named after the college I was attending. I wrote about the boat’s construction at the Hodgdon Brothers boatyard of double-framed/doubleplanked white oak for the hull and a 5-foot-wide band of Australian greenheart (or ironwood) at the waterline. I noted that the rig had no topmasts nor bowsprit to keep sailors safely close to the deck. The vessel details interested me, but my underlying motivation for the paper was a fascination with ice, isolation, and self-reliance within a small group on a boat. These had also been topics of interest to my adventurous parents, who had raised me and my three siblings on boats and near the water. My interest in science and the new Arctic came later.

Little did Andy Chase know at the time, but he would go on to play a pivotal role integrating the Bowdoin into its sail-training role at MMA, keeping it active and also keeping it connected to its northern roots for the next 35 years. He is on board ArcticEarth for this trip to provide historical perspective. From the rooftop of a four-story Great Western hotel on top of the hill, Andy scans the horizon with binoculars, eager to be the first to see the wooden masts and signature ice bucket of the vessel that he captained to Greenland himself in 1985 and had stewarded for many years prior to retiring as a professor of marine transportation from Maine Maritime last spring. So far, he sees only low-level fog and the tops of massive and steady ice drifting out of the nearby Sermeq Kujalleq (Greenlandic), also known as Jakobshavn Glacier (Danish). This is one of the fastest-moving glaciers in the world. Ice flows into the sea at an average rate of 60 feet per day. I have my long lens trained elsewhere, on a few light fiberglass speedboats already in view in the foreground. About eight to ten are idling off the shoreside Lutheran church. Having the opportunity to be in Greenland on National Day several times over the past 20 years, I knew what was coming. Sure enough, a gunshot. “Look,” I point out to Andy, “they are beginning the competition.” Most of

the outboards throttle up and zoom north through the ice at a pace that feels perilously bold to my piloting sensibility. One boat slips quietly south around the corner, however, into the fjord of the Sermeq Kujalleq. With no sighting of the Bowdoin, we decide to stroll down towards the church to confirm what I anticipate we will see next: a ritual of identity.

“Who is a Greenlander?” Natuk Olsen, an Inuit/Dane friend from Nuuk, had received this comment from a faculty reader of her doctoral dissertation. Natuk’s topic was the impact of a rapidly changing climate on the diet and identity of Greenlanders. A valid question, I thought with the new Arctic in mind, but one that seemed to exasperate Natuk as she told me about her research over coffee at the university back in 2017. “Here we are all Greenlanders,” she had said, “Inuit, Danes, yes, but also fish and whales and the plankton they feed upon, and seals.” Her words stuck in my mind, and by the time Andy and I reach the shore today, a freshly killed seal is being cut up on the rocks. The speedboat that went south had returned with this bounty within an hour, the undisputed winner of this year’s seal-hunt competition in Ilulissat. Raw bite-sized pieces of its liver were already being distributed to all who wanted a taste. Andy takes a nibble, but I decide to pass on the temptation this time — as a Mainer, I have my own diet and identity, which includes childhood memories of wildly overcooked liver and other essential animal organs

highly valued by my mother but not as much by her four kids. I do appreciate the historic role of fresh liver for the Inuit, however. Liver was the highest source of vitamin C historically available in these high latitudes prior to the limes and lemons now shipped to markets at exorbitant prices. “Beyond nutritional basics, we establish our identities as Greenlander humans by eating Greenlander seals in the fullest sense of community,” Natuk had explained. Seal-catching competitions on National Day are popular in many of the larger 50 (or so) settlements along the west coast. The winning hunters — and the losing seals — are whisked off to each town’s barbecue, with leftovers distributed for consumption among the community.

The Bowdoin eventually does arrive at the dock, and I am soon interviewing two students. One is Lucas, an engineering student with a focus on power generation. He reports, “It was mind-blowing to get up for watch one day and see that there’s ice out there!” The second student, Nicho, is in MMA’s ocean sciences program, hoping to graduate and get a job providing technical marine support on research vessels at Woods Hole. On a tour below decks, Nicho pulls out his laptop to share measurements from the conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) measurements that he and his student colleague, MacKenzie, have conducted en route to Greenland from Maine. They will also be collecting eDNA samples with kits that ArcticEarth and the Ocean Genome Atlas Project

Liver was the highest source of vitamin C historically available in these high latitudes prior to the limes and lemons now shipped to markets at exorbitant prices.

provided (OGAP was a partner on a science mission in 2023 and also our first science mission this year). These kits will reveal any DNA shed by any passing marine life, from the largest whales to the smallest plankton. I wonder if these students have ever considered plankton as fellow American citizens, vital to their American identity?

Ilulissat is culturally rich, but after a few days here, we are itching to head out to explore the region to the north — ideally under wind power. The next morning is windless in Disko Bay.

Typical. Approximately 80 to 90 percent of ArcticEarth’s transit time within fjords and bays in the summer is light to no wind. Usually, it either blows directly out of the fjord or directly in. On this morning, Andy and I film aboard Bowdoin, while Magnus skippers ArcticEarth up ahead. Captain Peacock is grateful for Magnus’ years of ice-piloting experience — with ArcticEarth and with many previous vessels in the high latitudes, including Skip Novak’s Pelagic fleet. Our goal today is Equi Glacier in the northeast corner of Disko Bay. The two boats travel well together. Bowdoin is 88 feet overall, but the overhanging

transom and bow only extend the waterline length when the vessel is under sail and laid over a bit. Otherwise, under power and upright, the two boats have matching cruising speeds between 6 and 6.5 knots on average. Primary intership communication is VHF, with Starlink in the wings. For the daily gam, both boats have inflatable tenders that can be easily launched from deck. Andy Chase relays that the most frequent rig underway for the Bowdoin historically has been engine with foresail alone, sheeted centerline. Wind power was most useful when making the longer passages outside the fjords and bays where wind is more likely. The sails reduce the need for burning — and carrying —lots of diesel fuel on the longer haul legs around Nova Scotia and Newfoundland to and from Greenland and Labrador. This advantage of sail for passage-making is one that ArcticEarth also enjoys. The average five-month seasonal distance logged is 4,500 nautical miles, of which 35 percent is wind-powered.

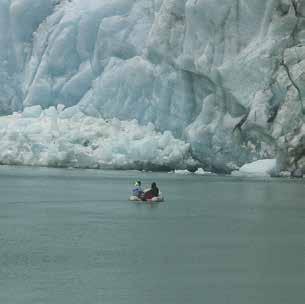

After two days, the convoy rounds a peninsula and heads southeast into a fjord increasingly thick with bergy bits, brash, and bigger bergs. The source is the Equi Glacier, deep within this fjord and the place where an occasional thunder and wave heralds the most recent ice to break off the great Greenland ice sheet. Shipmate and friend Philip Conkling writes, “Although an eerie calm engulfs us, the periodic glacial roars convey an uneasiness to the scene’s spectral beauty.” This is Philip’s fourth

trip to Greenland. The first three trips were with the businessman Gary Comer on board Turmoil, and led to a 2010 book titled The Fate of Greenland. With contributions from oceanographer Wally Broecker, glaciologist George Denton, and climatologist Richard Alley, that book lays out the evidence and process of abrupt climate change. ArcticEarth has provided boat support this year and in 2022 to another scientist who contributed to the understanding of abrupt climate change and more recently to the understanding of what is in the meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet. But the expeditions of Paul Mayewski and the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine are another story.

After several hours of headway, we gaze upon the broad face of the Equi Glacier. It is now only a few miles away, even though the distance looks like it is just a few hundred meters. The difficulty gauging distances by eye is one of many remarkable features when sailing in this landscape, where the massive scale of reference objects must be carefully balanced by tools like the radar or the chart plotter or — even better in an area where charts are often inaccurate — a simple handheld rangefinder. This tool is considered “essential” on board ArcticEarth by skipper Magnus and Julia. We are now pausing within the thickening brash ice, and students on the nearby Bowdoin are completing a CTD cast. Where will we anchor to rest? A forecast indicates we might be in for some active wind from the southeast.

Magnus and Alex decide the convoy will head to the fjord’s nearby leeward shore. It is 10 p.m. The late-hour sunlight is on the low end of its descending arc, a filmmaker’s dream light. Until August 13 at this latitude, the sun will never drop fully below the horizon. As shadows lengthen, I launch the drone and fly alongside and over the Bowdoin. I want to see its distinctive hull shape from this angle. Most vessels see their greatest beam length roughly halfway between bow and stern. For the Bowdoin, designer William Hand slid that aft 10–15 feet. This beam at this point means that the hull continues to push brash ice away from the vessel when underway for a longer time than if the beam was at the halfway point. Why go to all this trouble? Because ice is less likely to hit the propeller. That very real damage is the Achilles heel of small vessels piloting through ice. ArcticEarth has a spare prop and can also swing up the keel and rudder to make a swap-out repair ourselves.

The crew anchors, and we enjoy a late meal, mussels mariniere, thanks to this evening’s chefs, Philip and Sean Mahoney. They collected the feast on the beach yesterday. A bit later, groggy and catnapping in my bunk, I awake to a freshening breeze. Greenland’s version of a descending — or katabatic —wind has arrived. A similar wind can be seen in other parts of the world: the bora in the Adriatic, the Santa Anna in southern California,

the Barber of the South Island in New Zealand. In Greenland, the air falls off the Greenland ice sheet into a deep temperature differential. This evening in this anchorage, the katabatic arrives with a blast. Within 10 minutes, wind speed increases from 0 to 40 knots. ArcticEarth has 400 feet of half-inch chain and a 121-pound Rocna anchor. We are holding fast. A hundred yards away, the Bowdoin has two 500-pound fishermen’s anchors, with ¾-inch chain. They start to drag on the first one, so their crew readies the second anchor. That one holds. Anchor watch continues through the light of 1 to 10 a.m. The wind moderates.

Andy Chase notes that “the MMA students are growing in ways that they may not even recognize, but their parents and friends will see it when they get home.” I ask Andy to speak more about why sail training on a traditional ship is of value. “There are many reasons,” he says, “but one simple one is that young folk these days have lost their sense of direction. I don’t mean psychological or spiritual, I mean actual compass direction.” For the convoy today, the compass direction is northwest, even though we navigate with true direction only (on ArcticEarth, we use true at all latitudes, just to keep things consistent and simple). The formerly ice-choked fjord has been blown clear, so the convoy hoists sails and heads towards Atta, a snug harbor and a small settlement of camps.

Our time in convoy with the Bowdoin will soon be wrapping up. Captain Peacock has his sights set on traveling a bit farther north on his own, across the 70th parallel, before turning south for Maine. We wish to explore a fjord that ArcticEarth has never visited before heading around the southern tip of Greenland and then north towards Scoresby Sound on the east coast. The convoy says our respective good-byes, Julia presents some of her fresh-baked muffins to the Bowdoin cook, and we reposition our boat. The goal today is a trip to a nearby channel where the birds and an occasional spouting whale appear active at a distance. What is happening? A light rain begins. Little do we know the biggest surprise of the whole trip is just ahead.

Five of us launch the Bombard Commando tender and head for the channel. On the charts of our Garmin (Navionic), our Olex (user-generated), and our iSailor (Wartsila), this channel connects our fjord with a much larger inner fjord. A lot of sea life must pass through. Thus the collective naturalist question aboard concerns capelin, the small northern fish that are still actively schooling, much to the pleasure of the seabirds and whales of Disko Bay. Will they be concentrated and running through this channel en route to the spawning beaches within the inner fjord? As we get closer, we see that a singular humpback is swimming towards the channel. We follow. The current flowing through the channel is against us and building as we get closer to the entrance. Soon our headway over the bottom is nil. The whale continues, obviously carrying a little more horsepower in its glorious flukes and pectoral fins than our Yamaha 9.9HP. Magnus steers us

to the beach, where we jump ashore and make way with our iPhones and binoculars. The latter will not be necessary, it seems, since the spouts are just 20 feet off the channel’s beach. I am seriously regretting my decision to leave my camera on ArcticEarth due to the rain and the departure of the Bowdoin. But also — paradoxically — I’m feeling free from the imagemaker’s imperative to “shoot shoot shoot.” It has always been critical to jump back and forth between life’s balcony and life’s dance floor. I take a breath and walk closer to the spout.

Whales are some of the most photographic creatures I know, from above or below the water. The curves have been majestically honed by movements up and down through the seas over many millennia. The skin textures and tones are rich. The eyes liquid, gateways to the infinite. The movements are surprisingly quick for such a mass. Notwithstanding these attractions, a whale is technically “un-photographable … literally impossible,” the whale illustrator Richard Ellis told me once in an interview, setting the context for his own visual renderings, “If you are close enough to see all the detail of the skin texture, the eyes, and all,” he said, “you are too close to frame the whole creature without distortions of a wide lens. And if you are far enough away from the whole whale to see its entirety, the water is often too murky and you also miss the detail. Out of water, the body is unsupported by the water column and distorts. Hence, the impossibility of photographing or filming the true and complete whale. Illustrations are necessary.” The explanation is persuasive and also jives with what underwater cameramen have told me. A mysterious gap will always exist between whale recorder and recorded whale. As I get closer and closer to the whale, I sigh in the pleasure

of knowing that the unrecorded world is alive and well. This pleasure and reality lasts about 10 seconds.

Philip, Sean, and Andy all remark on the pungent smell of the fishy exhales as we walk downwind of what looks like a moderately sized humpback.

I’ll let Philip describe what happens next:

Everyone takes out their iPhones hoping for a shot of this spectacle when the whale surfaces again within 15 feet of the shore chasing capelin, which are flipping themselves out of the water to avoid the open maw of the humpback. None of us has been this close to a feeding whale before, and we are all stunned and exhilarated.

The feeding whale rolls on its side and swims back out into the channel, where it is whisked out toward the mouth of the gut, where it blows and then submerses again, cruising the interface between the fast-moving existing current and the slower-moving back eddy at our feet. We watch as the humpback repeats its previous maneuver chasing the capelin ahead of its gaping mouth until it lunges again to the surface and shots its giant baleen-edge mouth on another gulp of capelin. The screaming, wheeling fulmars

are diving just slightly beyond the arc of the turning whale to pick up any stragglers.

It is a mesmerizing spectacle that we cannot get enough of. Over and over and over the whale cruises back out to the entrance to the gut, blows once, submerges, and then cruises back within 10–15 feet of the shore. Because the water along the edge of the gut is only 15–20 feet deep, we watch it refine its technique. When it first submerges at the mouth of the gut, it swims the first 100 yards at cruising speed of 4–5 knots. Then it flicks its powerful flukes once or twice to triple its speed over several lengths as it shoots forward while using its flippers like giant underwater wings of a pterodactyl. The surface of the water is dappled with fleeing capelin as the giant maw of the whale breaks the surface expelling the water from the sides of its baleen for another mouthful of capelin. The humpback repeats this underwater ballet almost 100 times during the next hour and half. Everyone puts away their cameras except for David who has sent back to the boat for his tripod and big camera and keeps filming the ballet to capture every thrilling image.

Never in life, we all agree, have we witnessed anything more heart-stopping in nature. Thank you, Greenland.

Only later do I realize that this set of Greenland images got away due to a combination of rain on the lens, poor light, and too many creative risks with focus and depth of field. For some reason, this loss does not upset me.

Our time with the humpback is over. ArcticEarth pulls anchor and slowly heads back out to Disko Bay.✧

David and his two sisters and brother grew up around boats and the mountains, inspired by the adventures of their parents Connie and Deedee Conover (CCA members). After college, with a 100-ton USGC license, David skippered a 51-foot aluminum sailboat, completed two transatlantic crossings and five years as an educator at the Hurricane Island Outward Bound School in Maine. With Christopher Knight of the New Film Company, he co-produced a film for NRK Norway about Arne Brun Lee and the 1990 Two-Star transatlantic race, during which he and Arne were dismasted. For three decades, he has led Compass Light Productions, producing over 30 films in the Arctic and over 600 films worldwide for Discovery, PBS, and National Geographic. Compass Light has been ranked among the Global Top 100 Production Companies by Realscreen. David and his family recently completed 43 years of service as seasonal caretakers for the Curtis Island Lighthouse in Camden, Maine.

hours later,

Lydia Mullan | Reprint courtesy of SAIL Magazine

“Mayday, mayday, mayday. This is J/122 Alliance ... We’ve suffered catastrophic damage; the boat is sinking. There are nine souls aboard.”

If you spend any substantial amount of time on the water, you’ll hear a lot over the VHF. Swearing, squabbling, scolding … eventually, you’ll think you’ve heard it all. But there is nothing quite like hearing the haunting ancient turn of phrase, “nine souls aboard.” Especially when you’re one of the nine.

The 53rd Newport Bermuda Race began auspiciously enough on June 21, 2024, with hundreds of boats — racers and spectators alike — cheerfully crowding Narragansett Bay, shouting back and forth to friends and rivals while circling the start line. Our boat, the J/122 Alliance, slipped among the throng, excited to get our racing season’s biggest offshore event underway.

A boat with an Irish harp emblem and green and orange racing stripes skirted by us, and my teammate called out to them. “Hey, what are you drinking, Guinness or Jameson?”

“Heineken!” someone shouted back, eliciting a laugh from both crews.

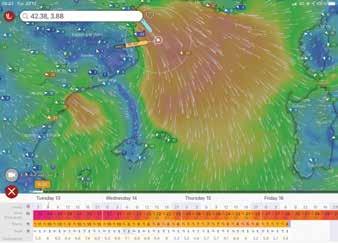

We didn’t know it at the time, but by race’s end we were going to be very friendly with that boat.

Our crew of nine consisted of Alliance’s owners, person in charge Eric Irwin (60) and navigator Mary Martin (61); watch captains Sam Webster (30) and Connor O’Neil (31); tech expert Bill Kneller (71); chief morale officer Eddie Doherty (56); assistant navigator Julija O’Neil (33); bow assist Mary Schmitt (22); and me (29), the bow person and on-board reporter.

Six of the nine were engineers, and the majority of us had sailed more than 1,000 offshore miles together. The boat was fastidiously maintained, and we’d met regularly during the offseason to prepare for the race, complete with pop quizzes and hours of assigned of lectures on weather, routing, safety, and more. Though the race only requires 30 percent of the crew to have offshore Safety at Sea certifications, almost all of us had been through the 15-plus hours of online coursework and the in-person, hands-on

“I felt it as much as I heard the screeching, metallic bang-bang! I tried to get the boat stabilized, but the wheel moved strangely in my hands, like there was not quite enough tension on it. Snapped rudder cable? Parted mainsheet track? Imminent dismasting?”

training. We had every reason to believe it would be a challenging but successful race, and for the first 36 hours, that’s exactly what we had.

Though we weren’t expected to enter the Gulf Stream until 10 p.m. on the second day, we started seeing signs of it that afternoon. The meandering midocean river of warm water has its own local climate, generating a cloud pattern similar to what you might see over land. First it was just a hint of fuzziness on the horizon, then the clouds started to take shape into massive heaps with clean, distinct edges. Within a few hours, we started to see sargasso weed that had drifted across the stream into the cold northern waters.

At the time of our crossing, the Gulf Stream had a large meander that we were aiming for to make a short, fast crossing, but it had also spit out eddies that made a minefield of swirling current surrounding the stream. Mary M. positioned us to slip into one of them at just the right angle to slingshot us onward.

I was on watch from 6 to 10 p.m. for our approach to the

Gulf Stream, and by the time I handed off the helm, we were in it for sure, the warm tropical air filling our sails and 4 knots of current churning below us. After my watch, I couldn’t help staying on deck to hang out for a bit, arrested by the view.

That far from land, the night was a deep black, and the sky was mottled with dramatic, heaping clouds backlit by the strawberry moon. Then the bright, clean light would break from the roiling cloudscape and, like a curtain whisked off a bird cage, we would have light. A moment later, blackness again.

When I returned at 2 a.m., it was to the same but more. The sea state had increased with the current, and though I know every sailor, like every fisherman, is liberal with estimating sizes, when standing at the helm on the high side, the waves often broke the horizon from my line of sight. At just a bit over 5 feet myself, I estimated the waves to be at minimum 7 to 8 feet.

In their handoff, the previous watch had mentioned the conditions made for tiring driving, so I suggested to Connor that we do short shifts. He agreed, and with Bill beside me

trimming the main and Connor and Julija on the rail ahead of him, I took the helm.

Thirty minutes later, Connor asked if I needed a break, but I was enjoying the waves. We weren’t slamming, and the sea seemed to be steadily urging us onwards. The boat was well balanced, and I didn’t feel overpowered. This was precisely the kind of gorgeous night sailing you go offshore looking for.

“Give me 10 more minutes,” I said.

Ten minutes later, he asked again.

“Ten more,” I repeated.

And then — sometime in that fateful 10 more — the impact.

I felt it as much as I heard the screeching, metallic bangbang! I tried to get the boat stabilized, but the wheel moved strangely in my hands, like there was not quite enough tension on it. Snapped rudder cable? Parted mainsheet track? Imminent dismasting?

In a heartbeat, everyone was moving. Connor was shouting, “All hands! ALL HANDS!” and Bill was at my feet, pulling up the panel for the rudder compartment.

“We’ve lost steering! Get the jib down!”

Below, Eric was awake in an instant, crawling to the back of Sam’s berth to examine the damage where water was already surging into the boat. As a career naval officer in the submarine force including command of a submarine, he’s more than trained to assess and respond to water ingress emergencies. Mary M., a Massachusetts Maritime Academy alum with her own career as a naval contractor, called back to him from the nav desk.

“Am I calling for a pan-pan or a mayday?”

There was a beat of silence before Eric said, “This is a mayday.”

Up on deck, Bill had made the same assessment.

Having dealt with a more minor flooding issue the previous season, we knew the quirks of our pumping system well, and Sam was able to get 4,000 gallons per hour of pumping capacity up and running in just a few minutes, buying precious time for help to reach us as Mary M. communicated with the Coast Guard and nearby boats. The good thing about being in a race is there are always boats nearby.

The whole exercise was executed with a sober diligence that perhaps belied the severity of our situation. People often say to me, “You must have been so scared,” but the truth is, I wasn’t. I don’t think any of us were. We snapped straight into mitigation mode. We had been trained for this, we’d taken our courses, we’d done our homework. The only focus was on managing the situation so that a crisis didn’t devolve into a tragedy — there was no time for fear.

As we began rotating below to secure the essentials from our personal belongings, Eric asked me to get some photos of the rudder compartment topsides. Sam was already back there, and we crouched at the transom to peer in. Fiberglass shards were everywhere, and water was slopping around, but it was clear to see what was wrong. The upper rudder bearing was ripped from the boat, and the lower bearing housing was cracked open, leaving a jagged, submerged hole with the heavy rudder post

still oscillating back and forth through it. The J/122 doesn’t have a watertight bulkhead that could’ve stopped the water, and even if we could’ve packed the hole around the rudder post to slow down the water, there was no safe way to steer the boat without doing more damage. The collision mat we’d practiced setting up was useless. The pumps could not keep up. We were hundreds of miles from land.

From the sound and power of the impact, it was obvious we’d hit something massive and manmade. But how could we have only hit the rudder and not the front of the boat or the keel? In the sea state, we were sailing at an angle to the waves, surfing down them fast but not head-on. The object was waiting for us in the trough of the wave, submerged and invisible in the night. The keel had glanced off it before the rudder took the full brunt.

I didn’t have long to marvel at the mortal wound, and after I’d taken a quick video of the damage, it was my turn to go below.

For all of the hours and days that I had spent on Alliance, she looked alien to me that night, lit like an operating room with glaring white lights I’d never seen on before. What had always been a hushed red cocoon after dark was jarringly stark and bright.

I triaged my cameras, drone, and mics and Tetris-ed all the priorities into one backpack. My passport and phone were already with everyone else’s in the ditch bag, but I had to find my credit card and driver’s license.

I dug through my personal bag, past the carefully packed

clothes adorned with the logos of various teams and programs that I had accumulated over years. None of that was coming with me. In the moment, I didn’t think twice about it, just glad that precious life-raft space was being allocated for my cameras. In fact, the only sentimentality spared was for my backup spray pants. As I scanned the salon for anything I’d forgotten, I saw them clipped in their place on the clothesline, and I was struck with the almost surreal realization that they would still be there when the boat hit the seafloor. They would never be unclipped.

Back on deck, Eric called for Sam and Connor to deploy the life raft. The conventional wisdom is that you should never step down into a life raft, instead staying on your ship until it’s so low in the water you can step across or up. But we were using the life raft to transfer to another boat that Mary M. had been in contact with, and they were close enough that it was time to start offloading Alliance.

The 7-foot wave state that I’d been enjoying so much an hour earlier was a danger now. Alliance was buoyed up and then dumped off the crest of a wave while the life raft struggled to keep up, its built-in drogue fighting all the way. Trying to keep it under control, Sam and Connor played tug-of-war against the ocean itself.

But the boys held fast as Bill, Mary S., and Julija got in, and we handed gear down to them. Eric asked me to run through the boat and take a final round of videos of the damage for the insurance, and then it was my turn to disembark.

We’d practiced getting into a life raft before, but every

single one of us fell when we hit the bottom. It’s not a floor, just a tarp over water. We each pitched forward, carried by our momentum, often crushing the people already in the raft. Because the transfer had to be done in one quick step with little takeoff room and even less landing room, I couldn’t say what a better strategy would’ve been. But if you ever have to take that step yourself, remember that a little tumble may be part and parcel of the transfer, and the last thing you want to do in that moment is hurt yourself or someone else.

Once I was in the life raft, Eric heaved three bricks of emergency water to me. Over the VHF we’d heard that the boat headed for us was only provisioned for seven people, so bringing water for our crew of nine was critical. Eddie had also dumped out my personal bag, filled it with protein bars and almonds, and tossed it into the life raft too. (Later there would be time for much consternation over the fact that neither the gummy bears nor the rum made the cut.)

In 1,000 miles sailed with Sam, I had never heard panic in his voice, so when he sounded tight and pained as he said they couldn’t hold onto the life raft any longer, time was up.

I think Eric and Mary M. would have wanted to be the last people on Alliance in the final moment with her, but with Sam and Connor already positioned to hold the life raft and with the strength it was taking them to manage it, safety won out over pride of place, and they climbed past the boys into the raft. Then they made the precarious leap, and we were off.

The silence in the life raft was stony and tense. Something dug painfully into my legs. Everyone was soaked, half in the lap of their neighbor, half under a pile of gear. Later, we’d watch footage from another boat’s perspective and see ourselves spinning and hurtling over waves, so impossibly small in that black night. When we got to shore, it was the memory of that half hour in the life raft that stayed with me.

If you ever have to get into a life raft, hope that it’s with strangers, because there is nothing quite like seeing your friends there.

Andrew Haliburton sat at J/121 Ceilidh’s nav desk at 3 a.m., tracking the other boats in their fleet. Suddenly, an alarm flashed on his screen. It looked like a man overboard.

Having navigated for multiple winning Transpac campaigns, Andrew was no stranger to seeing an emergency alert pop up on his AIS. Typically it was followed by a quick call from the boat saying that everything was fine, and it was an accidental trigger. He waited for the call, but it never came. A few minutes later, a new icon popped up — an EPIRB. There was no accidental triggering of an EPIRB. This wasn’t one person; this was a whole crew in trouble.

He rushed to alert Austin Graef, the 29-year-old helmsman, and called for all hands. Jim Coggeshall, the boat’s owner, and the other four members of their crew rushed to help. The stricken vessel was just 2 miles directly upwind of them, and they changed sails in a hurry to adjust course.

It wasn’t long before they could identify running lights that had to be their target. Andrew breathed a sigh of relief. From what they’d heard from Alliance over the VHF, it’d sounded like there was a possibility that the boat would be gone by the time they reached its last known location. But running lights would give Austin something to steer by and the crew of Alliance a hope of being rescued. In a sea state that was at least twice as high as a life raft was tall, it would have been nearly impossible to spot the raft on its own.

As they got closer, Ceilidh’s crew stripped the boat of any lines that could potentially drag overboard to foul the prop and fired up the engine. Austin’s brother, RJ, prepared a line to throw out to the life raft while their father, Rick, got out a spotlight to illuminate their target. Jeremy Marsette kept a lookout

Left: Sixteen people on a J/121 is a tight fit. (Eddie Doherty photo) Right: Bill Kneller tries to get some rest in the sail-bag heap.

“We were a huge inconvenience to Ceilidh. We had more than

doubled the number

of people on their already at-capacity boat. They were so gracious with us, sharing everything they could, from food and clothes to deodorant and sleeping space.”

while Ryan Mann pulled out his phone to record.

“We did that first pass where we could see into the life raft,” Austin recalls, “and just seeing the look of nine people huddled up inside, it’s giving me goosebumps. I will never forget that.”

In the dark and the sloppy waves, he could barely see what he was aiming for, just trying to get Ceilidh as close as possible without running over the raft. RJ’s first two tosses didn’t make it. The third did, landing squarely in the hands of a distant figure reaching precariously out over the water.

With the line secured on both ends, RJ and Rick tried to reel the life raft in but to no avail. Even with Andrew’s help, it was too much drag. They ended up wrapping the line around their primary winch and grinding it in, inch by inch. To Andrew, the raft looked impossibly small, and as Rick and RJ started pulling people out of it, it was almost cartoonish to see so many bodies lifted from such a tiny space.

RJ reached down into the life raft as person after person handed him their tether to hook onto the back of the boat. Then, he and his father would each grab a hand at exactly the right moment and haul them over the chasm of churning black water to safety.

In the cockpit, Ryan took down the names of everyone recovered from the life raft, nine souls in all.

The Archambault 40 Banter, whose crew was good friends with Alliance’s, had also diverted to assist, and they were circling Ceilidh, preparing to take on some of the refugees. But in all the

bashing against the transom, one of the life raft’s tubes had been punctured. There was a second of hesitant deliberation about what to do next before RJ cut in.

“We are not putting anyone back in that life raft; no one is going off this boat.”

The grim reality of the situation set in. We were in for a long ride to Bermuda.

* * *

The combined Ceilidh-Alliance crew convened on the rail just as dawn broke, saying tentative hellos and exchanging names as the sun rose over a very different scene than it had set on.

Somewhere behind us, Alliance pinged on the tracker one last time.

“Are you OK?” Sam asked me.

“Oh yeah, how are your ribs?” Bill said.

“What?” I asked dumbly.

“You could’ve broken a rib hitting the wheel that hard.”

I felt around for tenderness. “I’m OK. I don’t think I hit the wheel.”

Sam stared at me dubiously for a moment. “You put a dent in it.”

There is a unit in the Safety at Sea course titled Being a Good Victim, which outlines all the things you should do if you go overboard to improve your miniscule chances of being located and recovered. But they failed to mention what happens

in the days after you’re recovered. What happens when you put nine wet, exhausted, traumatized people onto a boat that is underway, hundreds of miles from shore and still trying to function as a racing team?

We were a huge inconvenience to Ceilidh. We had more than doubled the number of people on their already at-capacity boat. They were so gracious with us, sharing everything they could, from food and clothes to deodorant and sleeping space. We all tried to stay out of the way as much as possible, but there was just nowhere to be that wasn’t underfoot. The three berths

Above: On the final approach to Bermuda, the author takes a photo with the combined crew (note the handprint-shaped bruise from being hauled out of the life raft. Left: RJ Graef, left, and Rick Graef race a crowded boat towards Bermuda.

in the salon were in constant use, as was the aft cabin and a little crawl space behind the head that Austin and RJ had dubbed “the condo.” Still, there were usually three additional people lying in a heap of sails on the floor, sleeping if they were lucky.

I spent most of my rest time all the way forward, where my nausea was soothed by the cool trickle of water dripping down from the forward hatch onto my face. Small mercies, and all that.

We kept a rough watch schedule to free up space below, but other than sitting on the rail, there was nothing to do. No time to decompress or process everything that’d happened. Just long hours to sit and think.

The conditions remained relatively the same for the next few days, and Ceilidh continued taking a beating from the waves. At one point, a shout for RJ wrenched me from an uneasy doze. Through the forward hatch, I could see one of the stays bouncing listlessly against the jib. I watched as they scrambled to fix it, weirdly unable to muster any sense of urgency. Later, the rudder bearing started sheering off bolts, and again RJ was up in an instant, making repairs. Still, I existed in a numb daze.

Their crew worked tirelessly to keep the boat in good shape and get us all back to shore, with the Graefs sleeping no more than 45 minutes at a time as they traded off the helm for days, and the others supporting them and trying to keep up a sense of normalcy for the rest of us.

The last night was the worst. We were slamming, and I lay on the floor in the sail-bag heap next to Bill and Eddie.

“Are we worried about the water dripping around the mast?” I asked.

“Lydia, I’m worried about a lot of things,” Eddie said in a small voice.

“Yeah.”

“I’ve been thinking about how they have an ten-person life raft.”

I nodded even though he couldn’t see me in the dark. It’d crossed my mind as well.

“If something happened to Ceilidh, I’d be in the water.”

“Me too,” I said.

“Yeah. Pretty much all of us.”

When I couldn’t take lying still anymore, I headed up on deck to wait out the night. It took about five minutes to be completely soaked through by the waves. Sam was huddled beside me, trying to avoid the worst of the water coursing down the side decks. Even though he was right next to me, I couldn’t seem to speak. I would’ve done anything for a hug in that moment, but instead I curled in on myself, numb with misery and the adrenaline crash.

Mary Martin (Bos) and Eric Irwin (Bos) were co-owners of Alliance. Mary learned to sail as a teen in New England where she attended the Massachusetts Maritime Academy. She has a career in the Navy as a civilian engineer/project manager. Mary has been a boat owner since 1986, and has extensive (25 years) one-design and near-shore racing along with two previous Bermuda races. Eric is a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy (USNA) and learned to sail through the USNA offshore sail training program. Eric was a career submarine officer. He has extensive (20 years) one-design and near-shore racing and has participated in five Bermuda races and one transatlantic race.

But as it always does, the eastern sky began to lighten, and what had been only darkness took shape with the dawn. A triumphant shout went out: “Land ho!!”

After days of open ocean in every direction, Bermuda was in sight.

An exhausted elation rang through the boat as we crossed the finish line and turned for the harbor. Austin passed out in the cockpit immediately while the crew around him shared a celebratory sunrise beer — it was, indeed, Heineken.

We strung up Ceilidh’s battle flag and a token Alliance flag below it and were met by friends with laurel wreaths at the dock. There were tears of relief and gratitude and sadness. It’s all a blur of hugs and photographs now.

In the hours and days after getting back to shore, I must have said a thousand times that though I hated to phrase it this way, it could not have happened to a better team. We were prepared, aware, and vigilant. We maintained our composure, and we all made it out alive.

And in Bermuda, at an evening party, the crew of Alliance danced. The band strummed up a song I knew, something exuberant and old school. Everyone was dealing with our ordeal differently, but for one golden moment, time slowed down, and I saw the laughing faces of my teammates and friends, safe and happy, and reveling in the tropical night air. Someone grabbed my hands and swung me around, laughing. There were people all around me, jumping and swaying.

It was suddenly too much, too loud. I needed air.

I broke from the crowd to walk down the dock, alone for the first time in days, the noise of the party dimming behind me. When I passed Ceilidh, I faltered, an unexpected sob ripping through me. And then I was on my hands and knees, vomiting into the dark water below, still carrying the weight of being one of nine souls, a weight I may carry onto every boat I sail for the rest of my life.

Lydia Mullan is the managing editor at SAIL Magazine, editor of Multihull Power and Sail, and the former media manager for Cole Brauer’s historic 2023/24 circumnavigation. In her seven years with SAIL, she has published over 300 articles, including the boating industry’s best adventure essay and the best article about a woman in boating as recognized by Boating Writers International in 2024. She is a 2024 graduate of the Magenta Project.

Sailors involved with a rescue during the Newport Bermuda Race discuss the takeaways, big and small.

By Lydia Mullan

Editor’s note: During the Newport Bermuda Race this year, the J/122 Alliance struck a submerged object in the Gulf Stream in the middle of the night, suffering damage that caused her to sink (see “A Eulogy for Alliance,” SAIL magazine, October 2024). Fellow racers aboard Ceilidh, a J/121, and Banter, an Archambault 40, responded to Alliance’s mayday, and while Ceilidh took on the entire nine-person crew from their life raft, Banter stayed close by until everyone was safely in Bermuda. In September, US Sailing awarded the responding crews its Arthur B. Hansen Rescue Medal. SAIL managing editor Lydia Mullan was a member of Alliance’s regular crew and spoke with others about key takeaways from the sinking.

From its onset, the J/122 Alliance program was designed for learning. It created opportunities for talented young sailors to participate in offshore races alongside veterans, held scores of training days to prepare and foster crew dynamics, and enriched the on-water experience with supplemental educational materials. We learned countless lessons on seamanship and the practical skills of running a boat. In the wake of Alliance’s sinking, boat owners Mary Martin and Eric Irwin, along with crew members from the boat that rescued and carried us to Bermuda, share the program’s final lessons.

For Eric, the successful rescue of all nine crew members on Alliance can be traced to the founding ethos of the program. “When we bought the boat four years ago, we wanted to establish a solid foundation for everything: safety, navigation, crew development …. That solid foundation from the very beginning was key. Practice, repetition, muscle memory, all of that made a difference in an emergency situation,” he says.

“We recognized that we needed to learn. As new skippers of an offshore race boat, we had to,” says Mary. “We had offshore experience, but being the owners and in charge of the boat, we needed to ensure that we could safely race the boat offshore and be responsible for other people’s lives. We don’t take that lightly.”

Before the race, our team met monthly to discuss everything that goes into a race like this: navigation, weather, medical .... There was homework, and we were assigned pretty much every lecture, report, and presentation on the race that’s ever been posted online. We discussed in depth the lessons from the tragedy in the 2022 race, when 74-year-old Colin Golder went overboard and drowned. There were pop quizzes, and many of us were involved with preseason prep.

“We learned every year that we had the boat, and we carried those lessons forward. Last year we needed a bigger pump for another race, and we decided that the weight and space it took up was worth it to bring along on this race,” Mary says. In the end, having the extra pumping capacity bought extra time for our rescuers to get to us.

Some offshore crews are cobbled together with friends of friends, whoever can take vacation time, and maybe that one guy you don’t know too well but who checks the box for Safety at Sea or medical requirements. Alliance was not built that way. The majority of our Newport Bermuda crew had raced over 1,000 miles together, and

the rest had been building their experience through practice days. That intimate knowledge of the rest of the crew, their strengths and weaknesses, brought us closer, but it was also a huge asset when we were trying to secure the best outcome of our boat sinking in the middle of the night hundreds of miles from land.

“One of the first things that comes to mind is how important it is when talking about prep for a race — before you can even practice or think about emergency procedures — to talk about crew,” says Austin Graef, who drove the J/121 Ceilidh to Alliance’s rescue. “Picking your crew, knowing each other’s strengths, talking about roles and responsibilities based on each of our strengths — that matters. If I could go back, I’d have had more of those conversations beforehand.” As the responding vessel, he says, they had to quickly make a plan, and it was easiest for those who had regularly sailed together to fall into roles compatible with their skill sets.

3. It’s Not Just About Your Boat

“One of my biggest takeaways was just how unprepared I felt to rescue another boat,” remembers RJ Graef, Austin’s brother, who was also aboard Ceilidh. “You learn how to do the emergency stuff on your own boat, but you don’t practice being a first responder.”

“They teach so much in Safety at Sea, they teach you so much about responding to your own emergency situation, but they don’t teach you really anything about how to pick up people from a life raft,” agrees Austin. “Being in the recoverer role is a totally different situation.”

Aside from crew-overboard incidents, there isn’t much standard procedure for rescuing that you can practice ahead of time. Developing strong boat-handling skills, situational awareness, and level headedness will help.

4. Find What’s Familiar

The Safety at Sea course recommends not changing jobs in an emergency. If you’re used to being in one role, that’s where your muscle memory will kick in, and that’s where you’ll be best equipped to notice if the situation is deteriorating. Still, your job won’t necessarily be as simple as it usually is.

“One thing that stuck with me was pulling down sails in the middle of the Gulf Stream,” says RJ. “It’s not your standard takedown, the boom’s flying all over the place, and we had to tie it down, do an emergency flake just to get it out of the wind. Even the things you’re used to doing can be really different in an emergency situation.”

5. Mind the Lines (All of Them)

“One of the first things we decided we needed to do was de-rig Ceilidh,” Austin remembers of the moment they got into comms with Alliance. “The last thing we wanted to do was foul the prop in that circumstance. All of the lines, tweakers, everything got put away. We did keep our spin sheets neatly coiled in the cockpit to make sure we had a backup to the life-raft painter on hand just in case, but we were only thinking about all the lines our boat. We weren’t thinking about the life raft’s drogue.”

“The first pass, we stayed wide to assess the situation, and between the spotlight and the moonlight, we noticed it under the water. That was critical. It’s not long, but there was a chance it could’ve fouled the prop while we were circling the life raft to get to [Alliance’s crew]. Once we got eyes on it and knew which direction it was dragging, we could avoid it, but if we hadn’t spotted it, it could’ve taken out our engine in the middle of the recovery.”

6. Managing the Fallout

“You’re going through your own thing, but so is everyone else around you. Everyone’s coming to that situation from their own place, so it’s important to remember that,” says RJ. His brother agrees: “We all had a ton of adrenaline in our systems. We were all awake, calm, focused. And then as that adrenaline wore off, it impacted everyone differently. Some people needed extra rest; some people took longer for it to wear off. But you’re still in the heat of things. We’re still out on the ocean, it’s not over yet, and that’s where you need to adapt and be flexible.”

Small human comforts, though largely impossible when you have 16 people on a 40-foot boat for two days, mattered too. I was loaned a dry shirt to replace my wet one, and sunscreen and sunglasses were also generously shared. Though I was mostly too sick to eat, my crewmates, new and old alike, pressed snacks into my hands.

“Establishing relationships, adding that human element back in, helped us to not dwell on what had happened and bring back a positive attitude. I think that had a huge impact on both crews,” says Austin. “Understanding the human side of things is so important.”

7. Find Your Buddy

“The buddy-boat concept was critical for our situation,” says Eric. “The rescuing boat has all the stress and all the people onboard, and they may continue to need help as they’re getting safely back to shore.” The Archambault 40 Banter — owned and raced by the Gimple family, who are close friends of the Alliance crew — was close enough to respond to the sinking vessel and offer assistance. The plan was that they would take on half of the Alliance crew, but a popped tube in the life raft made that impossible. Still, their role wasn’t done. They stayed close by Celidh for the next 52 hours.

“We had Banter right by our side and had open comms with them throughout the race,” says Austin. “Had we broken something else, we knew that they were there, knew our situation, and could’ve gotten to us quickly if we needed help. It’s OK to ask for help.”

“Ceilidh knew to ask for a buddy boat, and also Banter with their Coast Guard background was not going to leave our side,” remembers Mary. “I don’t know if every other boat would’ve thought of that, but having support after our crew was recovered mattered.”

“Pack your toothbrush in the ditch bag,” says Mary. “Bring a change of dry clothes. If you’re wet and can’t dry out, you’re cold. And the importance of emergency water cannot be overstated. You can survive a few days without food, but you need water. We stored ours in bricks that weren’t too big to take with us, which was essential.”

“After the 2022 tragedy, the race committee really stepped up their expectations for boat communications, and that benefitted us,” Eric adds. “The response from the other competitors was excellent.”

“Don’t let things snowball out of control,” Austin says. “When Ceilidh was under stress from the conditions and the extra weight, things started to break. It’s so important not to skimp on parts and safety gear. If we hadn’t had a drill onboard, I don’t know what would have happened.”

“Preparedness isn’t being prepared for one thing, it’s being prepared for any situation,” adds RJ. Having strong foundational skills and a consistently high standard of seamanship is the only way to ensure that those basics will be rock solid when the unexpected happens.

By William Strassberg, Boston/Gulf of Maine

Penguins came by to visit at least twice a day. We were anchored off Isla Isabela, Galapagos, and had been there long enough to become a small part of the local ecosystem. Penguins fed daily on the small fish around us, and blue-footed boobies dive-bombed en masse with a whooshing sound as they whistled by us at mealtime.

Our 62-foot Visions of Johanna was eight months into an 18-month journey from New England to New Zealand. Before the Galapagos, we had enjoyed time in Cartagena, Columbia, San Blas Islands, Panama, and mainland Ecuador. After six weeks in the Galapagos, we began readying ourselves for a 1,900-nautical-mile passage to Easter Island. We were three (plus one). I was sailing with my spouse, Johanna, and our adult son, Gram Schweikert. We also had a stowaway, our granddaughter’s doll named “Dolly,” who was accidentally left on board during a family visit in Ecuador.

Our pre-departure mode is both an active approach and a state of mind. We review the voyage plan and develop final to-do lists with a 10-day calendar of systems and vessel checks for seaworthiness. Navigation and weather options are discussed and finalized as we extract ourselves from sightseeing and excursions to focus on the upcoming passage. We were figuring out how best to provision and bunker fuel and began a proscribed program of interior cleansing and engine-room inspection early on, rig and deck checks and bottom cleaning towards the middle, and final preparations, such as lashing anchors, moving outboard to the forecastle, dousing our awning, and stowing the dinghy a day or two before departure.

Bottom cleaning is accomplished with both snorkel and dive gear and includes cleaning and checking speedo and thru hulls, propeller, and rudder. Our propeller is a self-pitching Autoprop propeller by Brunton, and we found an uncomfortable amount of play in one of the three blades during the check. We had been assiduous in Autoprop maintenance and greasing regimens. The propeller and blades were evaluated out of the water eight months earlier in Newport, Rhode Island, and in water recently at San Blas Islands, Panama. The new finding was of concern, and we immediately emailed questions to Brunton Propellers and their American distributor, uncertain about how worried we should be. Unfortunately, there were no replies, and three days later — two days before our planned departure — we contacted by satellite phone AB Marine in Rhode Island and Brunton Propellers in England. The news was not good: We were advised that the amount of play was worrisome; we should not set sail with the Autoprop as is. To make matters worse, they indicated the propeller could not be evaluated and checked in the water. It had to be pulled and examined after hauling at the

nearest boatyard. Not so easy.

Isabela is a nearly idyllic anchorage but not because of facilities and supplies. For instance, our fuel was purchased from tanks of an Ecuadorian fishing boat. In fact, there are no boatyard facilities anywhere in the Galapagos, and the nearest haul-out was on mainland Ecuador, over 600 nautical miles away. Mostly upwind.

Once the shock of the news passed, we began to devise a plan of attack. Distance voyaging, like ocean racing, brings out shortcomings in you, your boat, and your planning. Unfortunately, a propeller puller was not in our kit of onboard equipment. It is a simple piece of equipment, however, its concept is as follows: A plate with a threaded central hole lies aft of the prop over the central stub of the propeller shaft. A bolt is screwed through to contact the central stub to push the plate aft from the hub as the bolt is turned. Meanwhile, there is a second forward plate, bolted to the aft plate, with teeth that capture the propeller hub to pull it aft and off the shaft as the center screw is turned

The island’s mechanic shop had only rudimentary equipment but a very talented welder, Pachi, and an inventive mechanic, Jorge. We planned to design and construct a simplified propeller puller for the Autoprop by using a Brunton conical zinc as a template for threaded fixation holes. We also discovered a surprisingly well-stocked ferreteria (hardware store) and scavenged an assortment of suitable bolts and nuts. These islanders jumped to help us, and amazingly, we had a working model by 2 p.m. on day one, the day we received the bad news from Brunton.

The propeller is keyed and force-fit onto a tapered shaft. Now came the difficult part — conceptualizing how to remove the propeller underwater. On the hard, it would be relatively easy: Remove the terminal shaft nut, mark the prop location on

the shaft for later replacement, and attach the puller to break the hub free from the tapered shaft. Underwater this involved a small team of people, scuba gear, a bit of ingenuity, abundant good luck, and a boatload of patience.

We started straight away and donned our dive gear (Visions of Johanna carried gear and dive compressor). The first order of business was to remove the conical zinc anode and shaft nut. The zinc came easy, but after loosening the shaft nut locking screw, a 1¾-inch socket and breaker bar would not budge the shaft nut free. A longer lever arm was called for, and we discovered a new use for our emergency tiller arm, slipping it over the breaker bar. Next, we pushed the emergency tiller while positioned upside down with fins braced against hull, which turned the shaft nut, but the entire shaft moved with it Our hydraulic transmission required a shaft brake; the brake did not prevent

the entire shaft from rotating with the nut. A bit of spectra line in the engine room stabilized the propeller shaft, and finally, we broke the nut free. We swam the tiller round and round underwater, and the nut was off. This took about an hour.

With the shaft nut off, we were ready to remove the propeller. Version 1 of our prop puller fit well; the conical zinc did well as a pattern in ½-inch steel plate. Taps sized for the center-line hole were not available. It was necessary to weld an appropriately threaded nut over an oversized center hole in lieu of tapping. The steel plate and screws were fastened to the hub into holes that normally fastened the zinc. The center bolt was threaded through the nut for push-off but the propeller would not budge, even with our underwater acrobatics and emergency tiller lever arm. Tool shortages required the use of a drive reducer to fit the socket over the center bolt, and we eventually broke the reducer. After a quick lunch, we were over our disappointment and found a ½-inch breaker bar in town. We kept at it until we bent the steel center bolt and galled the threads to the welded nut. It was late, and we were spent after hours underwater. We called it a day.

The following morning, we brought the puller back to the shop, and a beefier center nut and bolt were welded into place. We refit v2.0 of the puller and had at it again. This time the new larger bolt sheared right at the nut. Sheesh! During fabrication, the bolt was used to align the new nut to the plate while welding, and the heat may have weakened the bolt. Fortunately, we had a backup bolt, and puller v2.1 was reinstalled after another round-trip dinghy and bicycle trip to the fabrication shop to remove the broken bolt from the nut.

Three’s a charm, and we had a fine sense of accomplishment as the hub finally popped free. Lines were tied to the prop, which was carefully backed off, minding the key. I filled my buoyancy control device for maximum buoyancy as the prop came free but still had a fast trip to the 20-foot sandy bottom before I and the prop were hauled up into the dinghy. We were feeling good, but also realized that this was the easy part. We still had to take apart and troubleshoot the Autoprop.

Autoprop blades fit onto threaded male studs on the propeller hub. After a tapered roller bearing and thrust race, the blade and bearing assembly are fit and tightened with an overlying locking nut and tab screw, all covered with a bearing cap and greased lip seal at the hub for water-tight security. We needed to undo all of this. After removing remaining growth and carefully to labeling each blade and bearing cap in the order of blade shimmy, we attempted removal of blade number one, with the most play. Removal of the bearing cap was difficult as we did not have the proper spanner tool. Self-pitching blades rotated and were difficult to hold steady without specialized (dis)assembly tools sold by Brunton; our juryrigged spanners would bend and twist out of the bearing-cap holes. Forced to be inventive, we needed to fabricate a custom spanner, but it was late, and we called it a day.

By 9 o’clock the next morning, we were back at Jorge’s shop with the blade carefully stabilized in a hydraulic press. A custom spanner was fabricated using a piece of flat-bar and an Allen key of the size to just slip into the bearing-cap holes. After careful measurement, Jorge carefully drilled holes in the flat bar and cut the Allen key in half, force-fitting them through the drilled holes. Voila, we had a custom pin-type spanner (Pachi later welded the pins in place and painted the part, but for now, it was serviceable). Using a 6-inch long pipe as a breaker bar, we managed to persuade the bearing cap off blade number one and finally had visibility inside the propeller assembly.

The next step was to remove the tab screw and locking nut, but something was wrong; the nut and locking screw were free to spin 180 degrees either way. The blade was clearly loose; now we had to figure out the problem. We studied illustrations in the user’s manual, carefully removed the bearings and blades, cleansed them of grease, and inspected the bearing surfaces for wear. All parts looked corrosion-free without signs of wear or water intrusion. We repeated the process for blades two and three. Blade two was fine, and blade three’s grease looked green and clean, with no signs of moisture at all. Overall, the initial inspection found nothing unusual, and we posited that we would be able to reassemble the propeller with existing parts and properly torque the nuts to remove any shimmy from the blades. At day’s end, we headed back to the boat to do a better job of cleaning, planning a final inspection in a more controlled environment than the outdoor machine shop.

Above: Positioning the propeller back onto the shaft.

Below: Turning the emergency tiller to tighten the shaft nut.

The following morning, we cleansed and reinspected the nearly pristine parts, focusing attention on the threaded stub as Brunton suspected a bent or damaged stub due to blade contact. It was then I had a eureka moment: With grease banished, I noted the thread pattern on the stub of the problematic blade one was offaxis and different than the others, appearing as a manufacturing issue. At last, we had an explanation of what was wrong: Blade one stud threads were off-axis, the overlying locking nut was cross-threaded and improperly torqued, and the bearings were never properly seated. The propeller was rarely run hard enough to cause a problem during New England summers, but with increased miles and some hard running during our voyage, the tab screw and locking nut became loose.

We sent photos to Brunton confirming that our hub was unusable and a replacement was necessary. This might not be a significant problem, but shipping gear into South America, particularly Ecuador, is fraught with difficulty. Ecuadorian customs are renowned as a black hole, able to swallow whole boat parts for two to four weeks or more. In addition, a large duty (30 to 50 percent) is paid, and declaring “Yacht in Transit” adds further delay with the requirement of a bond of the maximum possible duty, which may or may not be refunded months later.

We looked at other options. Personal experience informed us that hand-carrying parts via air was a good option, and we considered delivering the hub and blades to and from England for repair and reassembly, returning to Ecuador three days later. It would have allowed us to be onsite when Brunton engineers reviewed the hub and reassembled our propeller, but our Ecuadorian visas had expired during this (interminable) delay. We were allowed to stay on Isabella due to the situational understanding and good graces of the port captain, but upon exiting Ecuador, reentry would not have been allowed for nine months. That didn’t work!

We next looked into shipping a new hub to someone in the U.S. for transport to us in the Galapagos. This was our best option, and after broadcasting an internet-wide invite, a great friend and sailor from Vermont was willing to visit and fly the new hub to us. Machining the new hub took seven days, plus three more to ship it to the U.S. The flight to the Galapagos took two days, and on the afternoon of February 16, a month after our scheduled departure, Malcom and our new hub arrived in Isabela.