5 minute read

Love in the Blitz

from CTJC Chanukah bulletin 2020

by CTJC

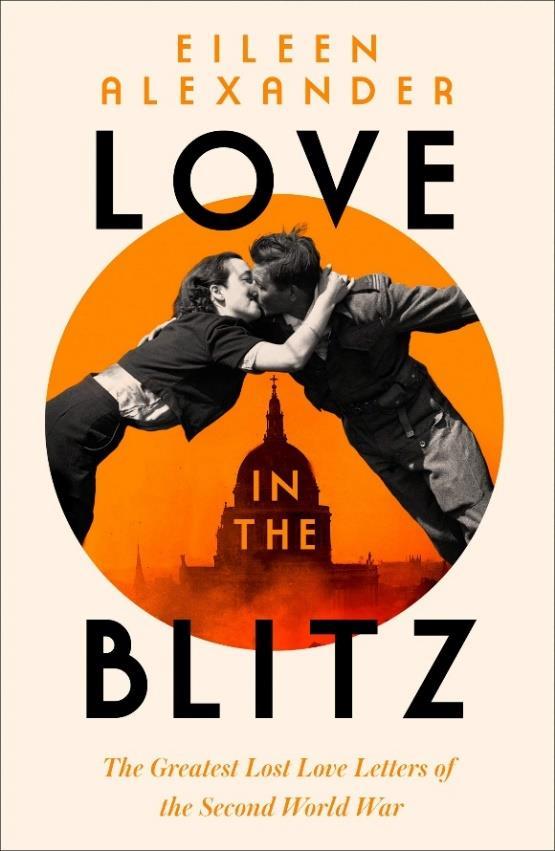

T h e gr e a t e s t lo s t lo v e le t t e r s o f t h e S e c o n d W o r l d W a r

by Eileen Alexander

Advertisement

Simon Goldhill

The best book recommendations come from friends who are passionate about what they have read. I first heard about Eileen Alexander from my chum, Oswyn Murray, an elegant, cosmopolitan, and now retired classics professor at Oxford. Over a glass of wine, he told me how he had been contacted by a complete stranger, who had come across his name in a collection of letters (it is always helpful to have a rare name like Oswyn, he reflected). Oswyn was described as dressed like a Red Indian and rushing about with blood-thirsty glee at a house-party: did he remember meeting a Miss Alexander in 1944, when he was a small child? This chance email has led now to the full publication of the letters, and it is a quite remarkable collection, called Love in the Blitz. Eileen Alexander was a Jewish girl, born to a wealthy family in Egypt, who came over to England in the thirties, and, in 1939, took a brilliant first at Cambridge in English. The story starts in Cambridge where she meets Gershon Ellenbogen from an orthodox Liverpool Jewish family, and, in the aftermath of a car-crash, they fall in love (they might have met at the Cambridge Jewish Society where they were both members). The book consists of the letters Eileen wrote to Gershon, as they are

separated first by brief parental disapproval and then by the circumstances of the war, as he is sent around Britain to be trained as a radio officer for the British intelligence, and then posted to Egypt for three years and more. She writes every couple of days and he replies, though his letters are lost. In her extraordinary prose, we get one of the most vivid pictures of the war I have ever read, not through military endeavours, nor through the Holocaust or other major arenas of suffering and despair, but through the eyes of a well-to-do Jewish girl with an active social life, an old-fashioned family, and a half-hearted career working for various branches of the civil service, where she met Oswyn Murray’s father. In her letters all sorts of familiar names burst into life. She was very close with Aubrey (Abba) Eban, whose books were so often given as Bar Mitzvah presents to my generation, and whose career as a diplomat became so well-known. Her portrait of him is repeatedly hilarious. She is friends with the Waley-Cohens, with Lord and Lady Nathan, the Daiches family from Edinburgh, Norman Bentwich (such an important Anglo-Jewish figure in the Mandate!), Horace Samuel, whose family firm became Decca Gramophone. And many others. Which is to say that she was from the very highest level of assimilated Jewish grandees in British society. Her mother was from the Mosseri clan, so you can add Egyptian royalty. She was also a special friend of Muriel Bradbrook, the mistress of Girton (who also taught my aunt, who was another Jewish woman who read English at Girton, just after the war) so we have the elite end of Cambridge life too. In every case, she writes with penetrating and often highly sniffy humour, sending her boyfriend snapshots of her life, from clothes to morals. It is the least stuffy book imaginable. Eileen was razor-sharp, except perhaps about herself. She was deeply and committedly in love, and we trace the love story through its more careful beginnings (is it too forward to call her boyfriend “darling”?), through her insistence that she would only have a full relationship with him when they are married, to their wedding and the birth of their daughter, which is when the letters stop as they manage finally to live together. When we meet her, she is just down from university and she writes with the thrilling insouciance and self-regard of a very smart student who is in love for the first time and wants to impress her

reader. She can be a bit of a pain, but as she matures so too does her reflectiveness.

Three strands were particularly revelatory for me. First, she describes the extraordinary tensions within a family under the pressures of the blitz. She lived at home with her parents until she was married at 26. The day-to-day stresses and boredoms clash against the genuine terror of certain awful nights of bombing and the constant thump of the antiaircraft guns on the top of Primrose Hill. We rarely see in literature what the long-term effects of the war were on personal relations in this mundane way: the spirit of the blitz was cantankerous, bitter, and tense as well as supportive and stiff-upper-lip. I wonder if Covid will produce anything so telling? I suspect not, thanks to social media and the collapse of the very idea of long, literate letter writing. Second, she describes what it was like to live through the war’s changing sense of social life in terms of being young and in love. There is a fascinating contrast with some of her friends who form all sorts of often disastrous sexual liaisons, and her own mix of passion and sense of moral fervour, and her discussions of how she expects and hopes that her boyfriend abroad will behave. Again, we are used to stories of wild romance in war. How interesting it is to see a different side so articulately and often painfully expressed: neither she nor her mother seem to have had any education in even basic anatomy. Her horror, at age 25, at seeing her first cut-away bra is a wonderful scene of youthful moral confusion. Third, it is hilarious to see the chaos of the wartime ministries in action. The everyday tales of confusion and hierarchy in her places of work are anatomised with flair and a surprisingly riveting cast of sharply observed characters. What keeps the book going, however, is not only the sheer intensity of her love (it’s a really romantic book) but the sheer joy of her prose. She uses capital letters galore, and underlinings, to give it spice and emphasis, and her mix of misery at Gershon’s absence, delight or dismay at her friends’ adventures, anger at the world and her parents, murderous rage towards and then pride in her brothers, hilarity at the people the war leads her to meet, and brilliant observational humour is a heady brew. Here, chosen almost at random, is her account of meeting an old friend who was trying to get her support for Cambridge communists: “She cited Eric Hobsbawm as a Pearl among Cambridge Page 11