The Art & Film Issue

February / March 2025

62

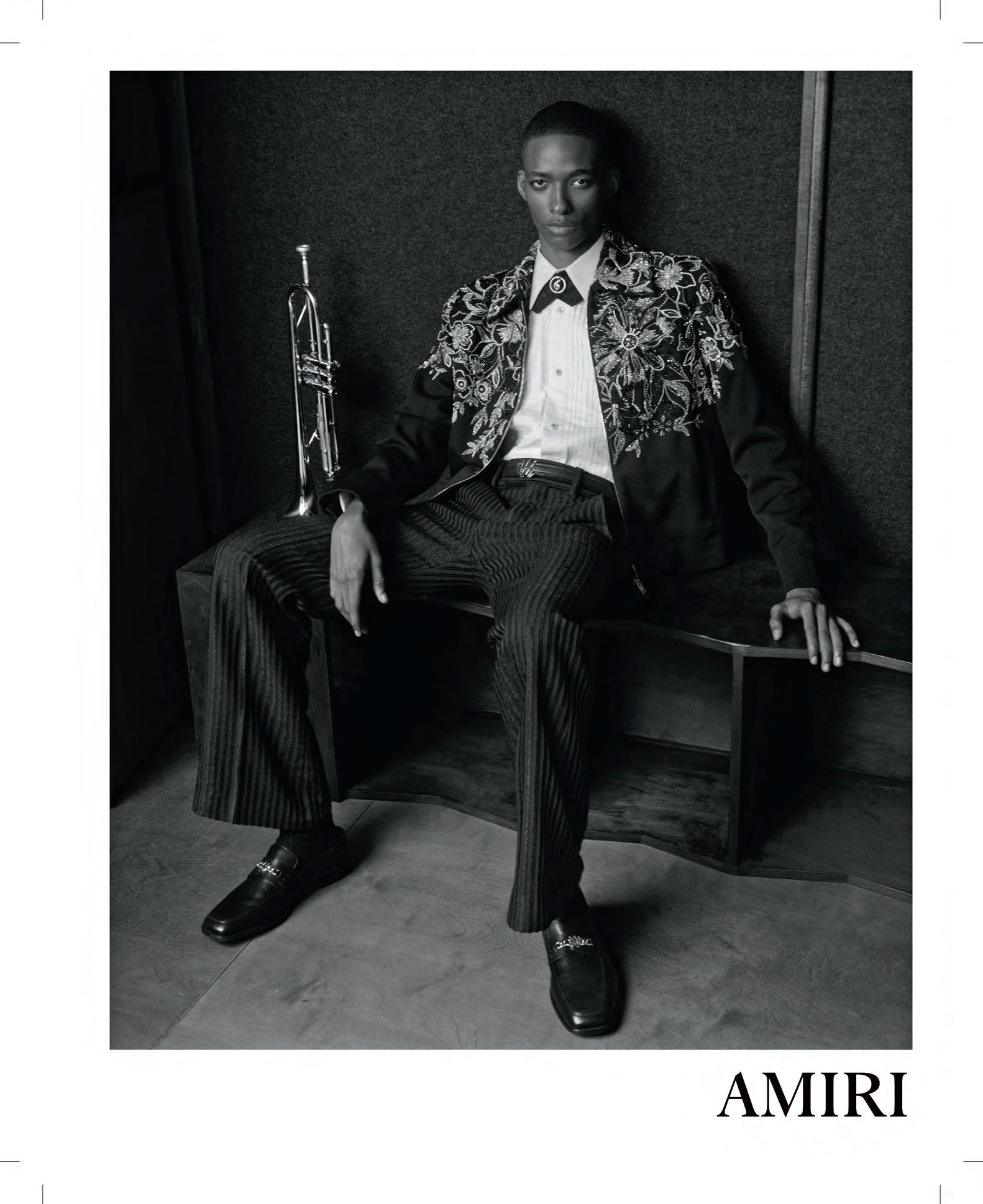

ALICE COLTRANE’S ETERNAL NOW

At the Hammer Museum, a new exhibition takes on the legacy of the legendary jazz musician and devotional leader.

A BRAZILIAN ARTIST TAKES NEW YORK

This spring, the Guggenheim will open a show dedicated to the kaleidoscopic oeuvre of Beatriz Milhazes. 64

66

74

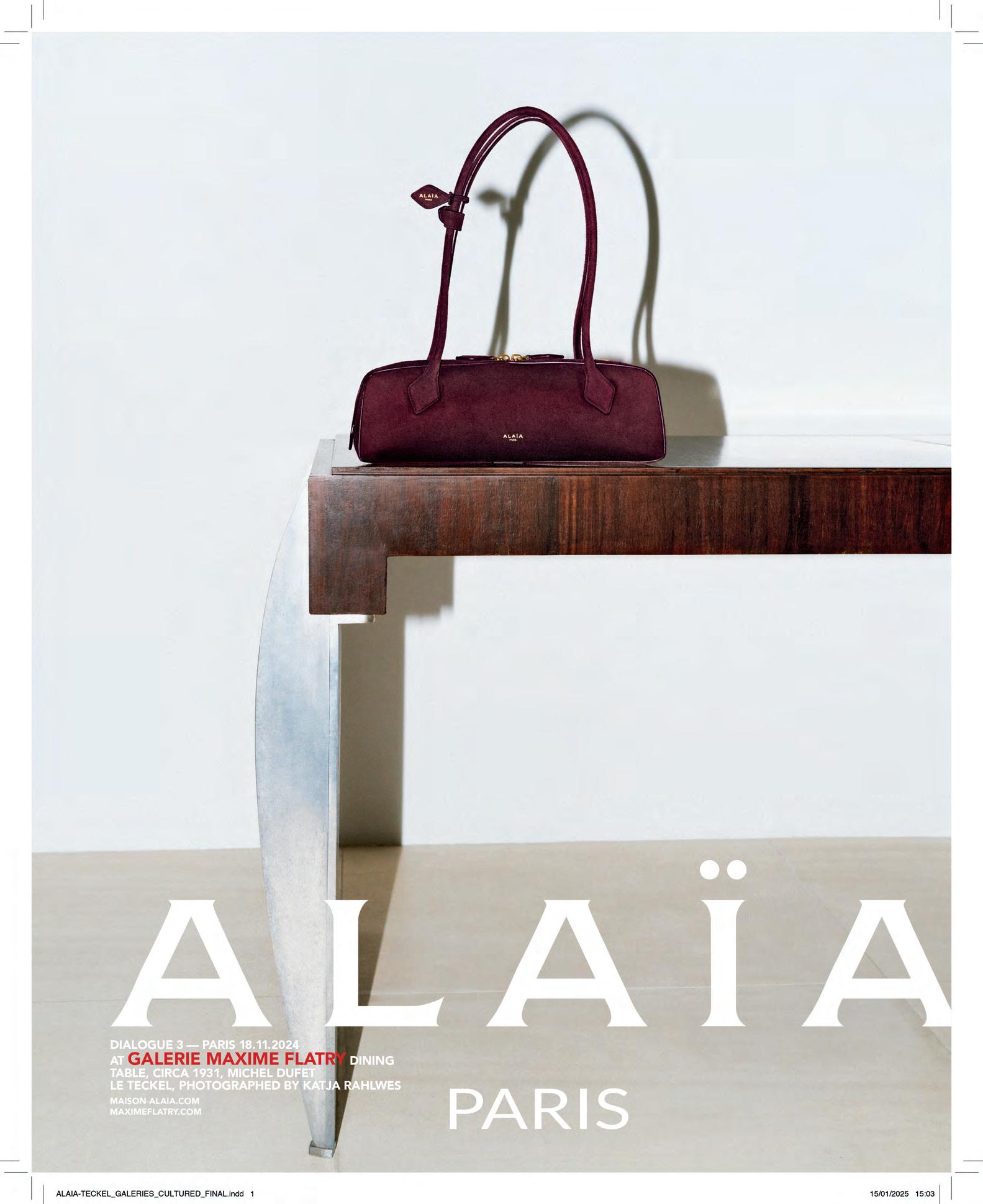

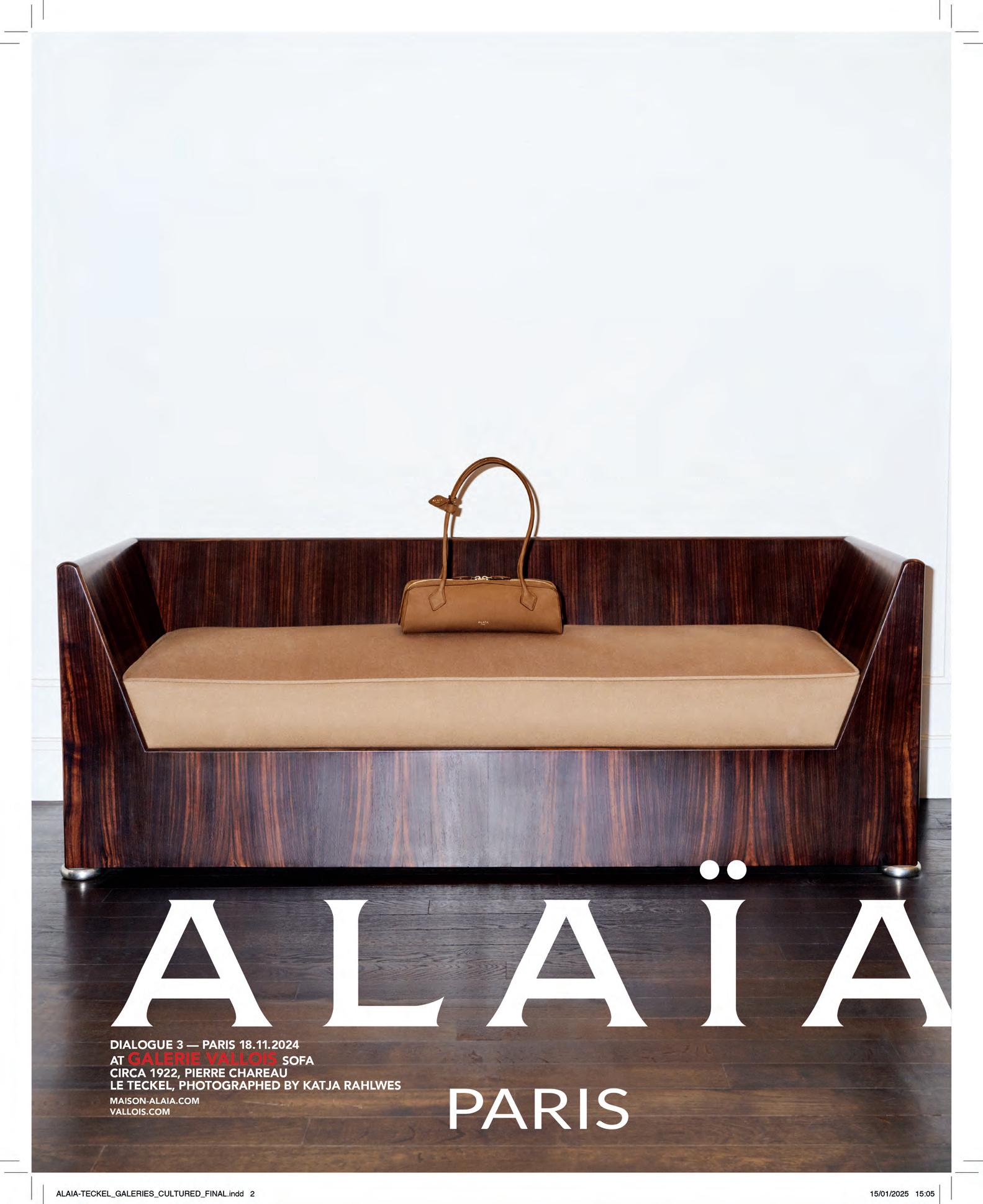

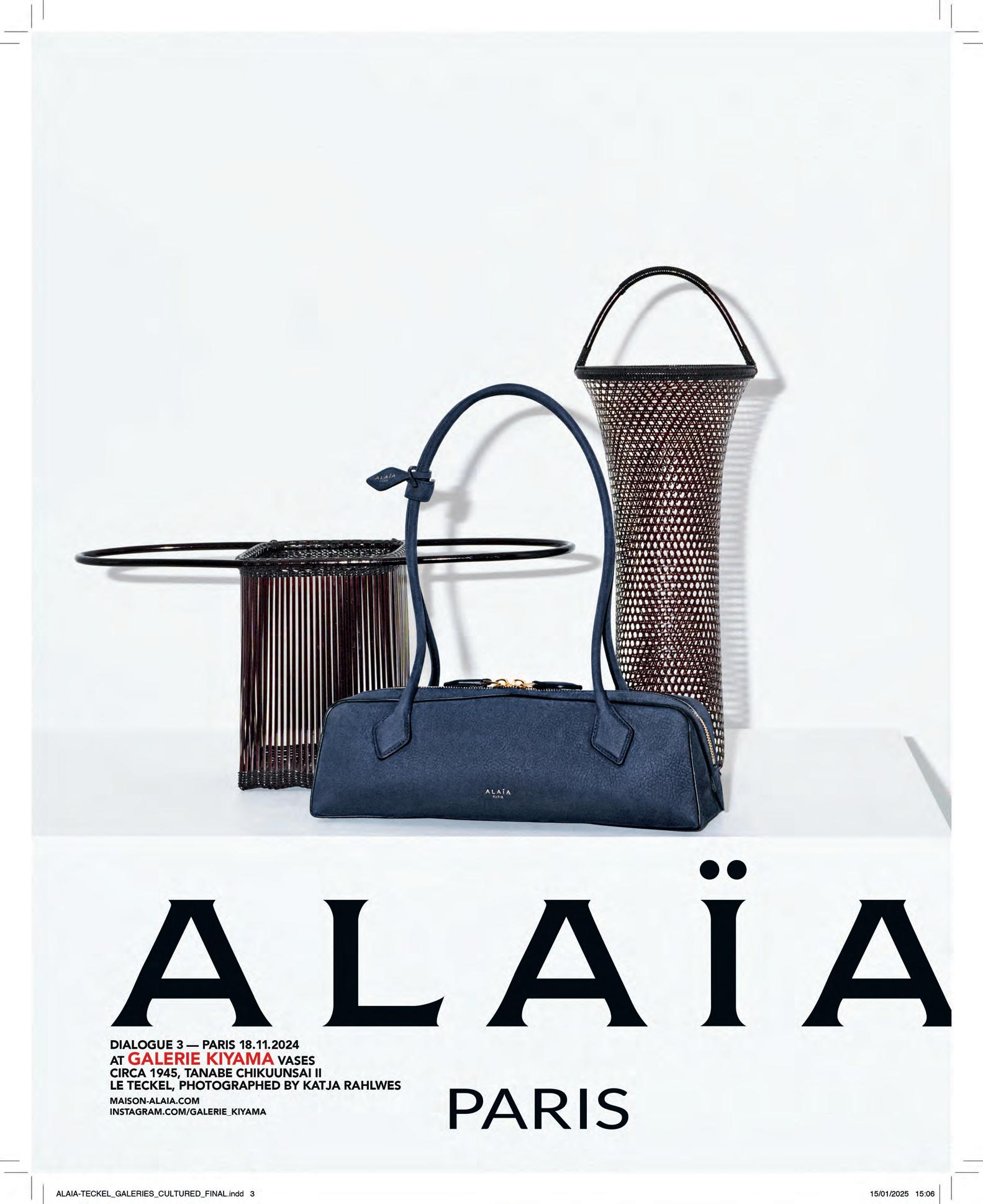

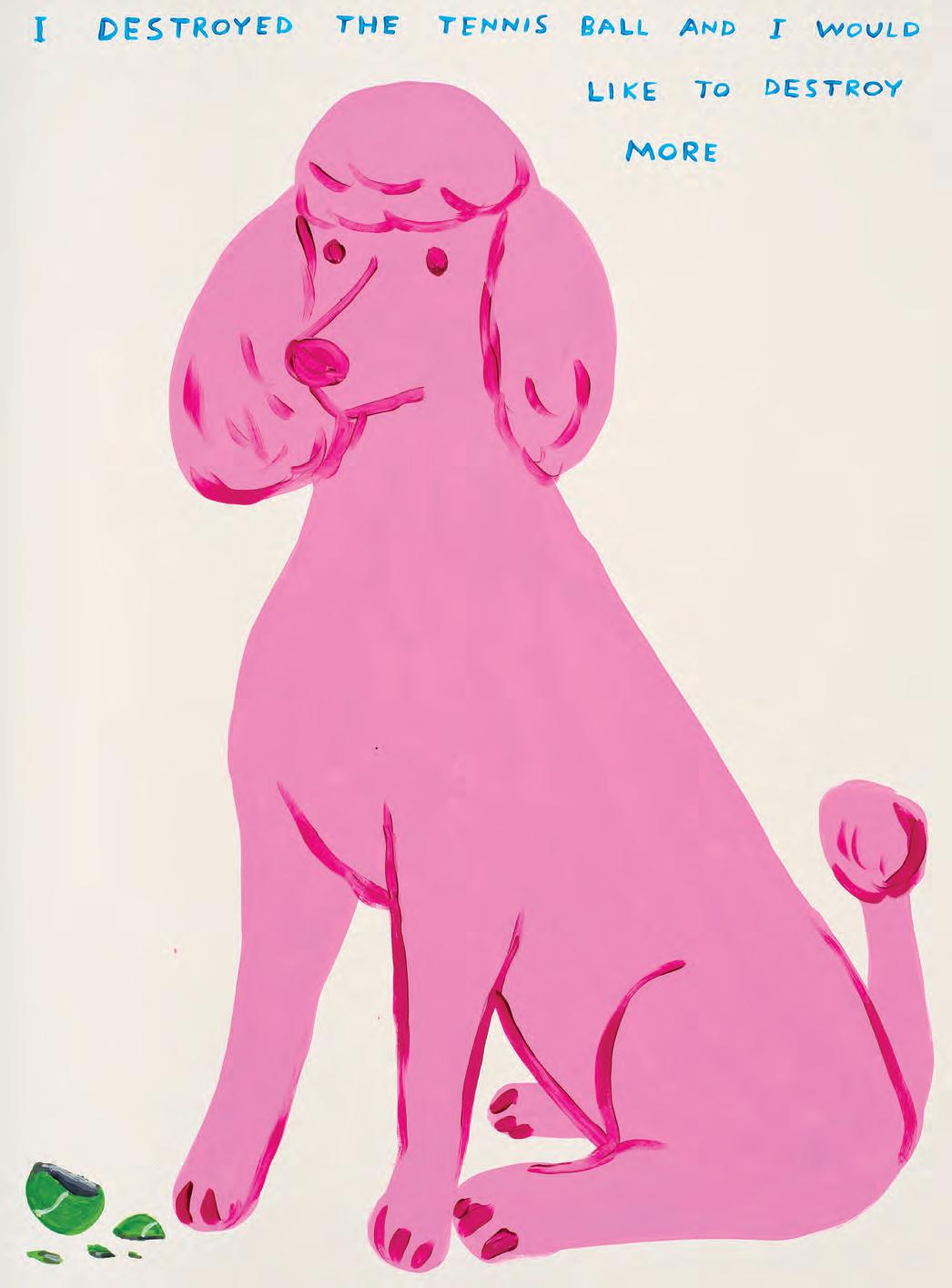

FASHION ON A LEASH

The adage goes that pets look like their owners—but when it comes to the fashion world, where appearance is the highest form of expression, the connection runs even deeper.

IGNORANCE IS BLISS—UNTIL IT’S NOT

In her latest film, Magic Farm, artist Amalia Ulman takes Chloë Sevigny and Alex Wolff down to Argentina.

LOVE ME, LOVE ME NOT

Writer-director Cazzie David’s latest project, a romantic comedy run amok, examines the dark side of modern relationships. 76

78

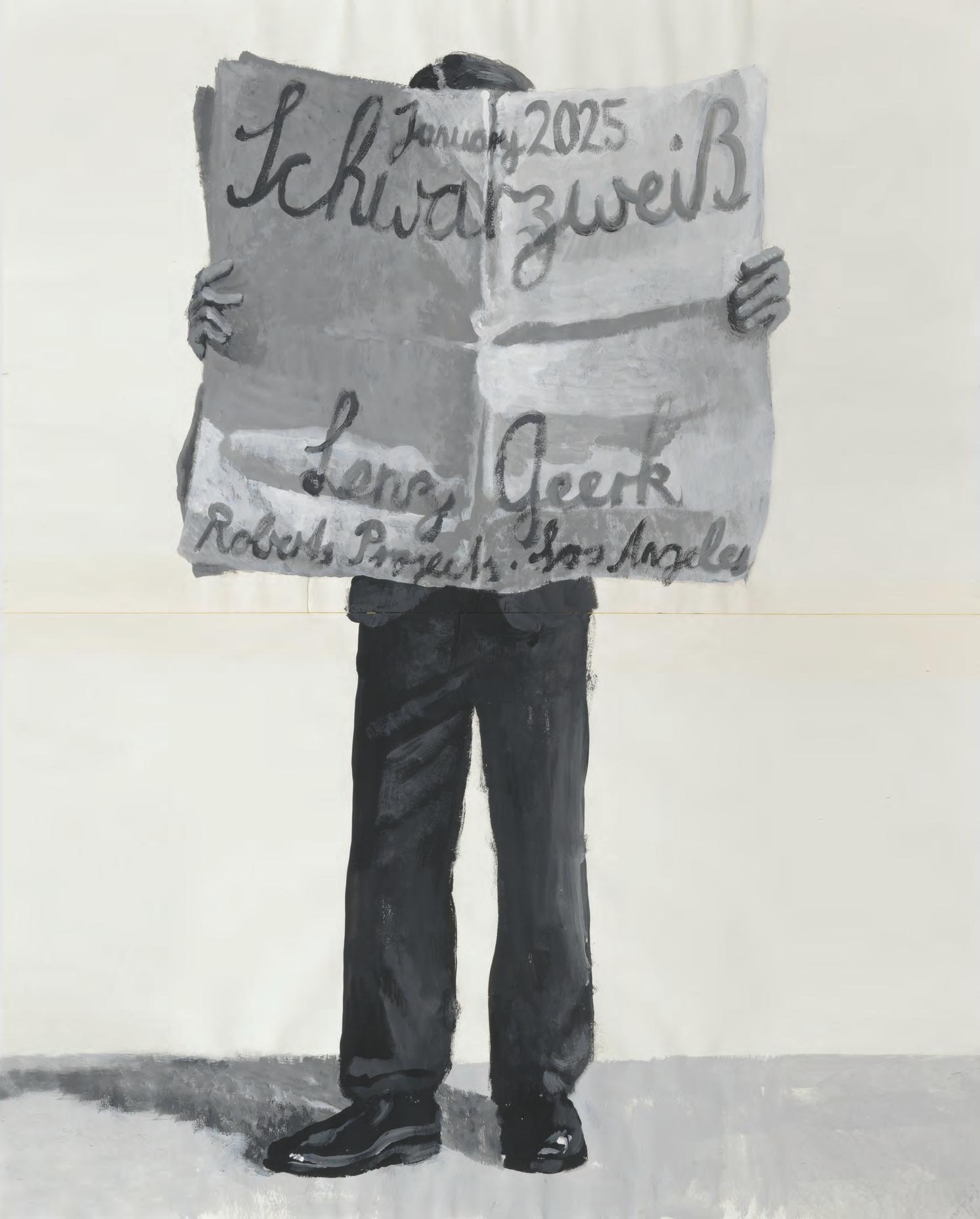

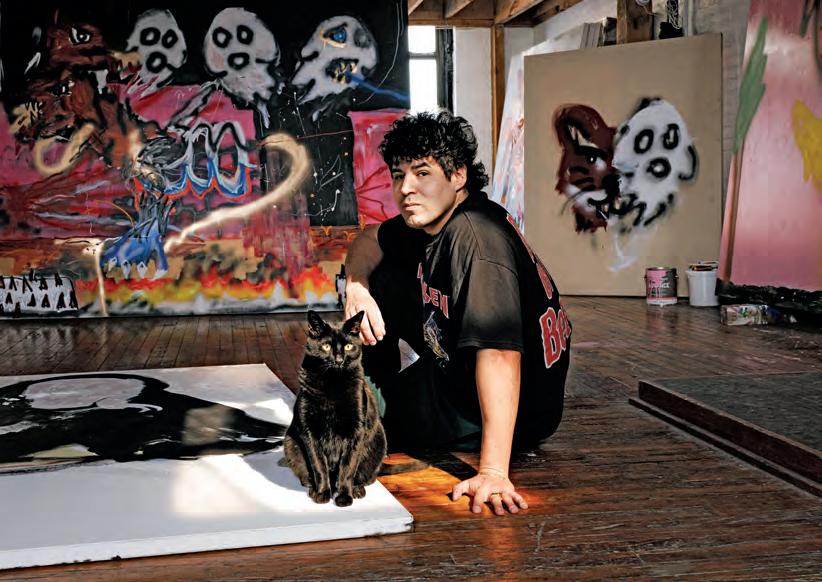

ROBERT NAVA LEARNS HOW TO HOLD BACK

The artist, who found fans and detractors during the recent market boom, cautiously returns to the art-world stage.

80

82

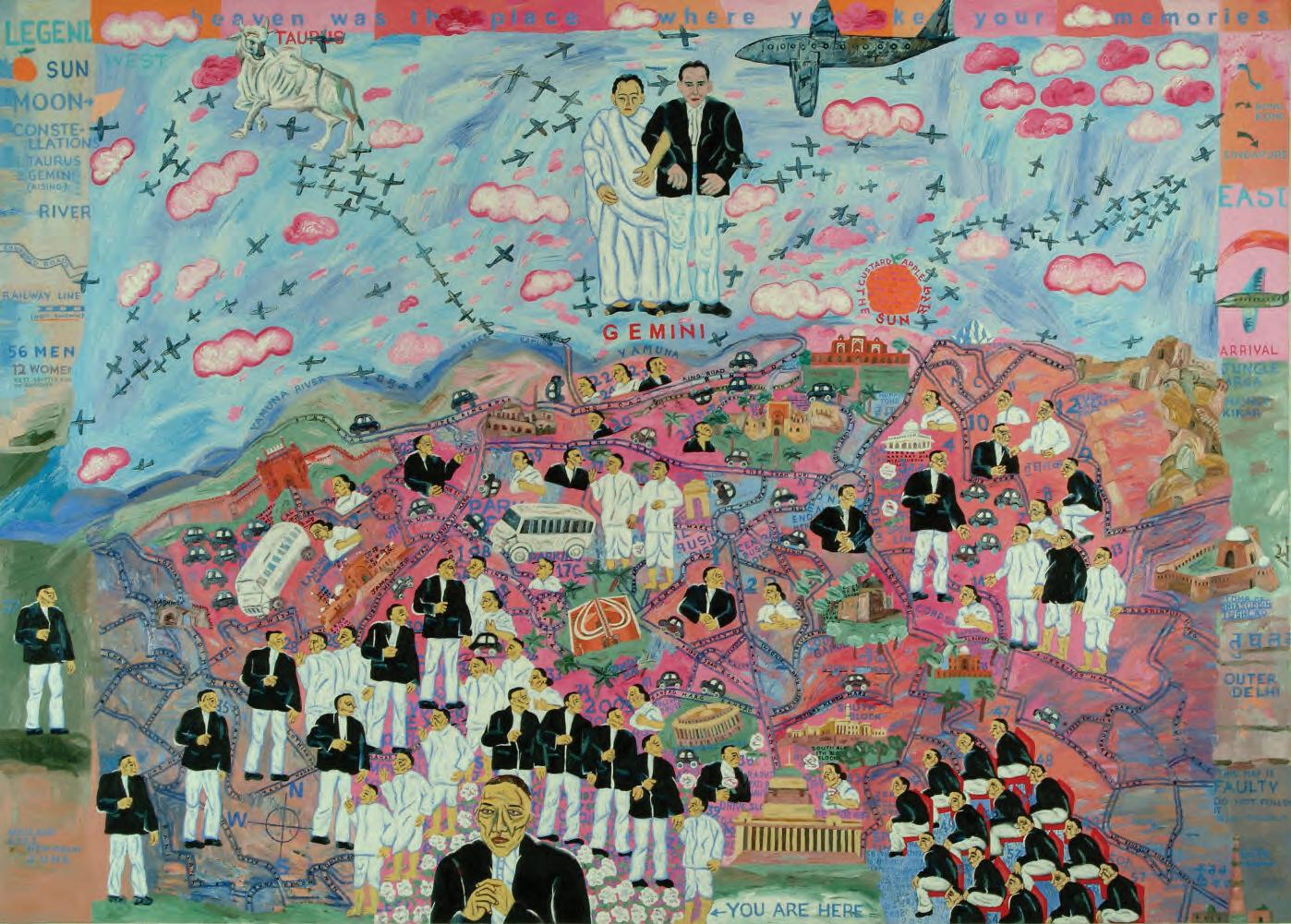

BELIEVE, AND DOUBT AGAIN

Serpentine’s spring exhibition, Arpita Singh’s first solo outside of India, celebrates the singular artist’s six-decade journey.

THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING PIPPA

Our critic remembers the singular body of work and life left behind by the late Pippa Garner.

84 ALL TOGETHER NOW

88

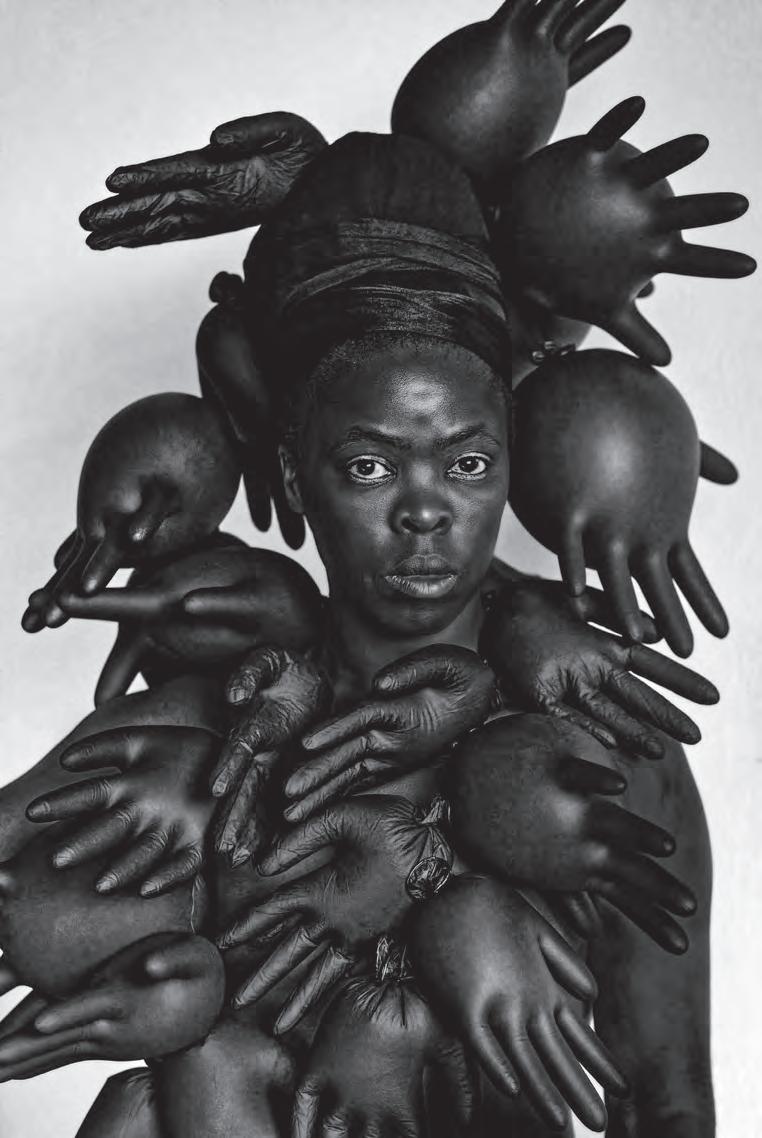

MALCOLM PEACOCK IS THIS YEAR’S YOUNG ARTIST PRIZE WINNER

The New York–based artist was selected by a panel of jurists composed of Legacy Russell, Ruba Katrib, and Kelly Taxter.

For this year’s edition of Frieze Projects, eight Angeleno artists hold a mirror to the city that inspires their work.

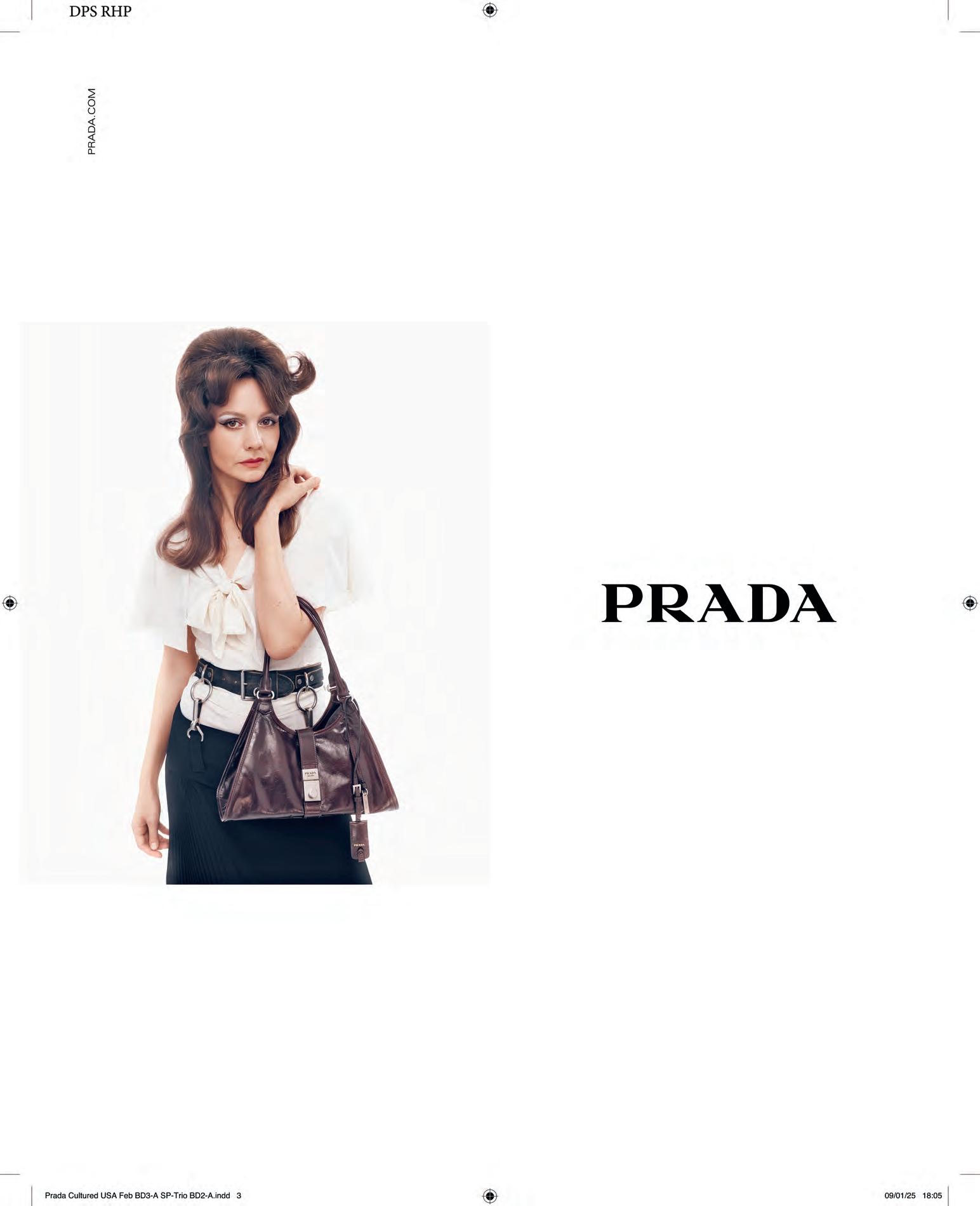

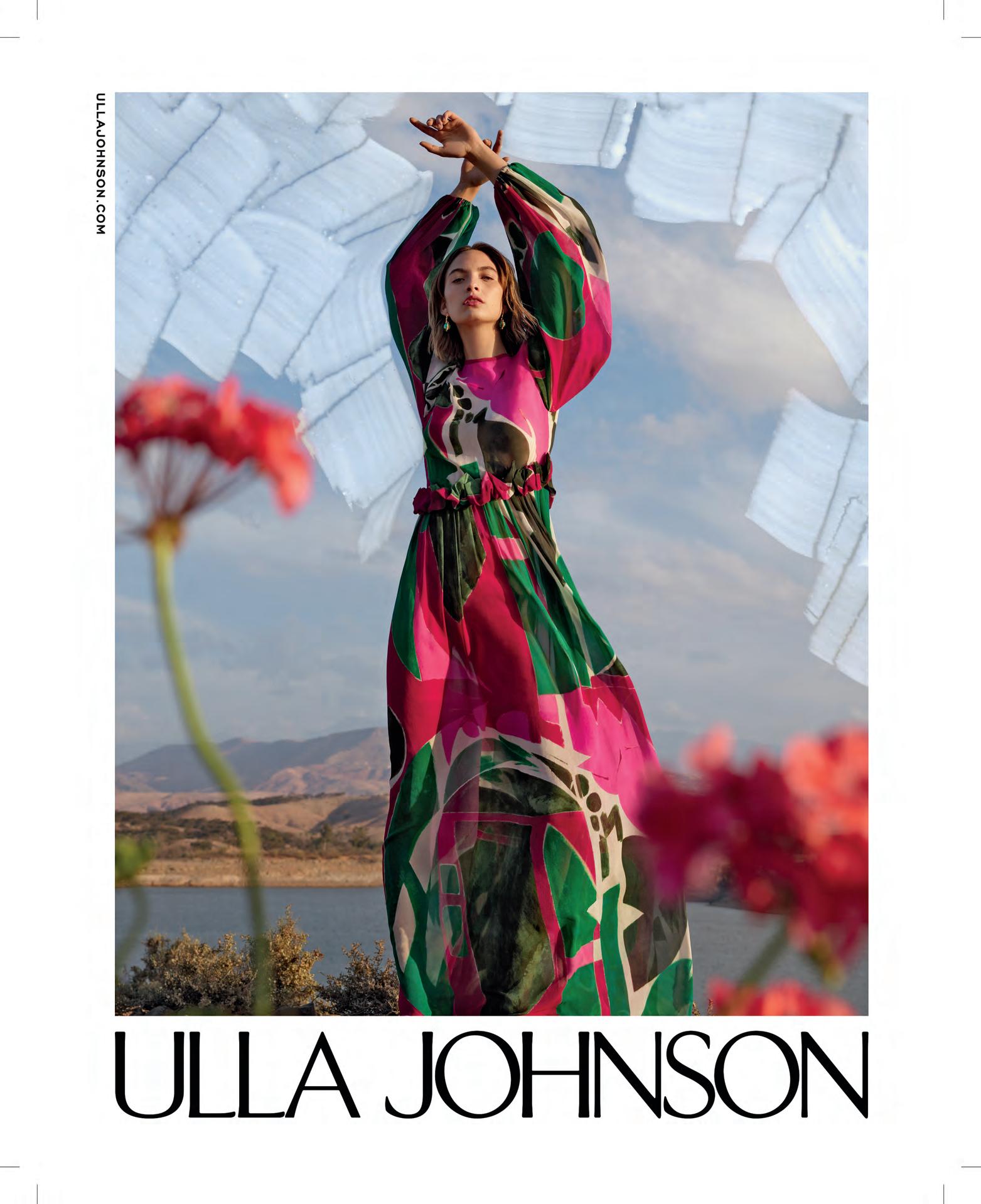

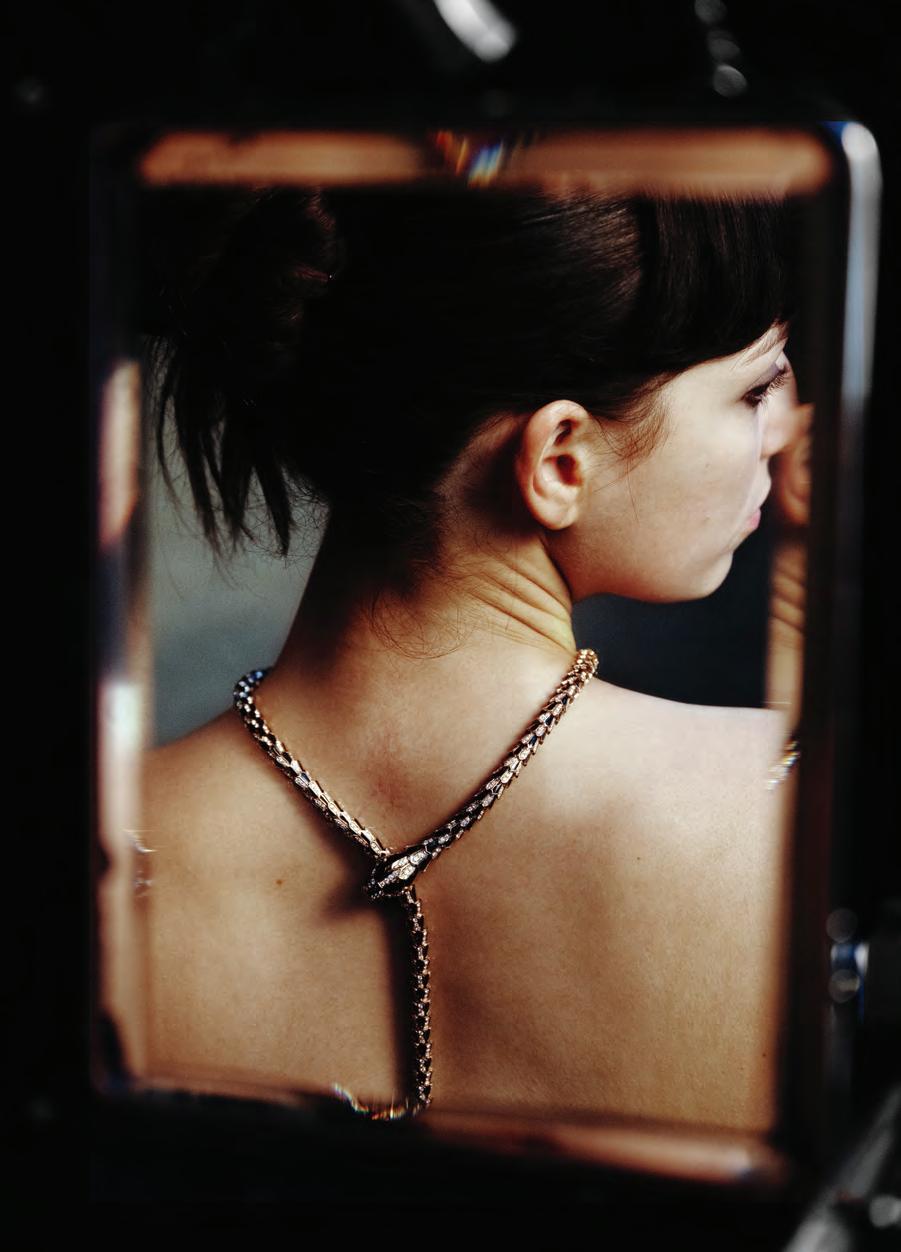

90 FERNANDA TORRES PHOTOGRAPHED IN NEW YORK BY JEREMY LIEBMAN WEARING A DRESS BY ISSEY MIYAKE, NECKLACE BY TIFFANY & CO., AND SHOES BY JIMMY CHOO.

PERMISSION TO PLAY

In 1998, Del LaGrace Volcano brought four friends to London’s Hampstead Heath—a wellknown cruising ground—for a photo shoot. Thirty-seven years later, the images are being given a new life with Queer Dyke Cruising.

February / March 2025

TEAM SPIRIT

As comedian Aidy Bryant prepares for her second run as host of the 40th annual Film Independent Spirit Awards, she calls up fellow two-time host Nick Kroll for some last-minute advice.

NATASHA ROTHWELL BARES IT ALL

A decade into her career, the White Lotus actor and How to Die Alone creator is renewing her commitment to challenging herself—and the film and television industry—at the same time.

ON ARTISTS’ TIME

For the newest edition of its Artist Series, Movado enlists Derrick Adams.

CULTURED’s co-chief art critic talks to the collector and gallerist about buying a Van Gogh and starting a museum on Mars.

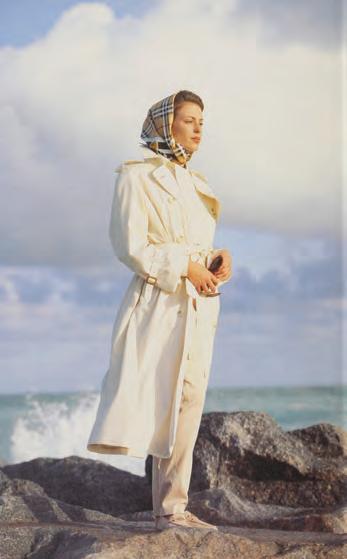

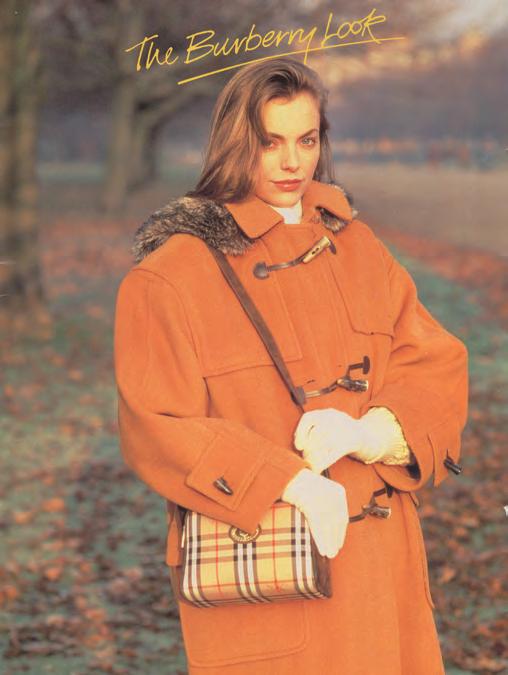

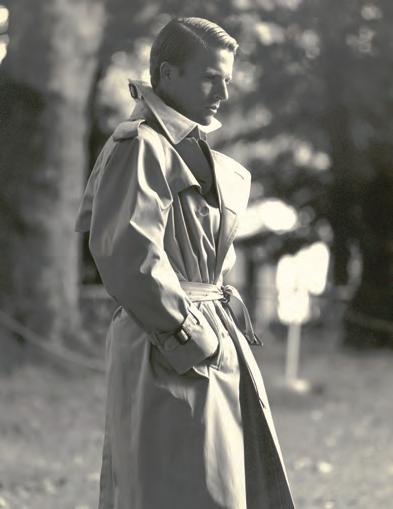

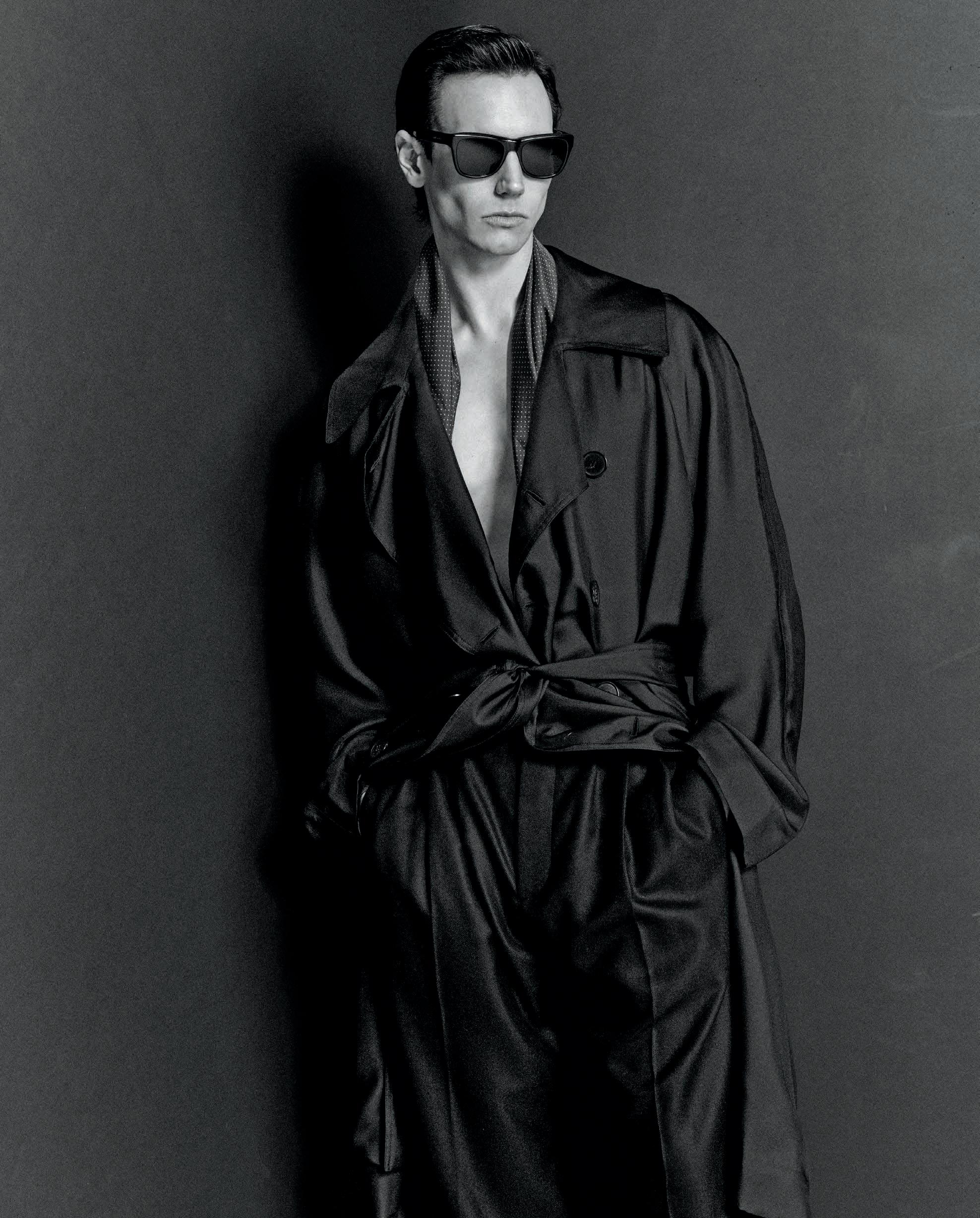

POSH DRENCH OF THE BURBERRY TRENCH

One writer dissects the outer garment’s undying glamour.

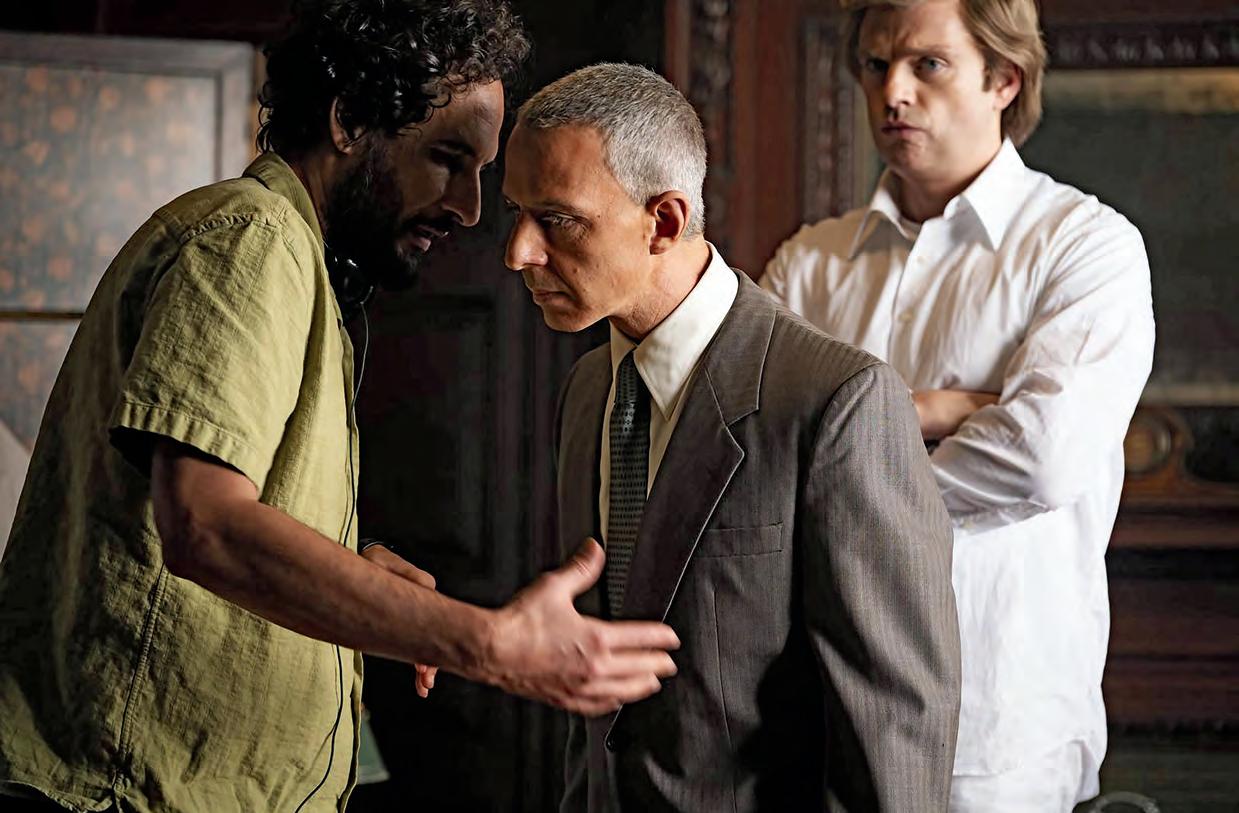

ALI ABBASI’S NERVES OF STEEL

The Danish-Iranian director is no stranger to challenging subjects. But The Apprentice tested his resolve.

FERNAN DA TORRES’S BEMUSED VICTORY LAP

The actor is already a legend in her native Brazil. Now, Hollywood is catching up.

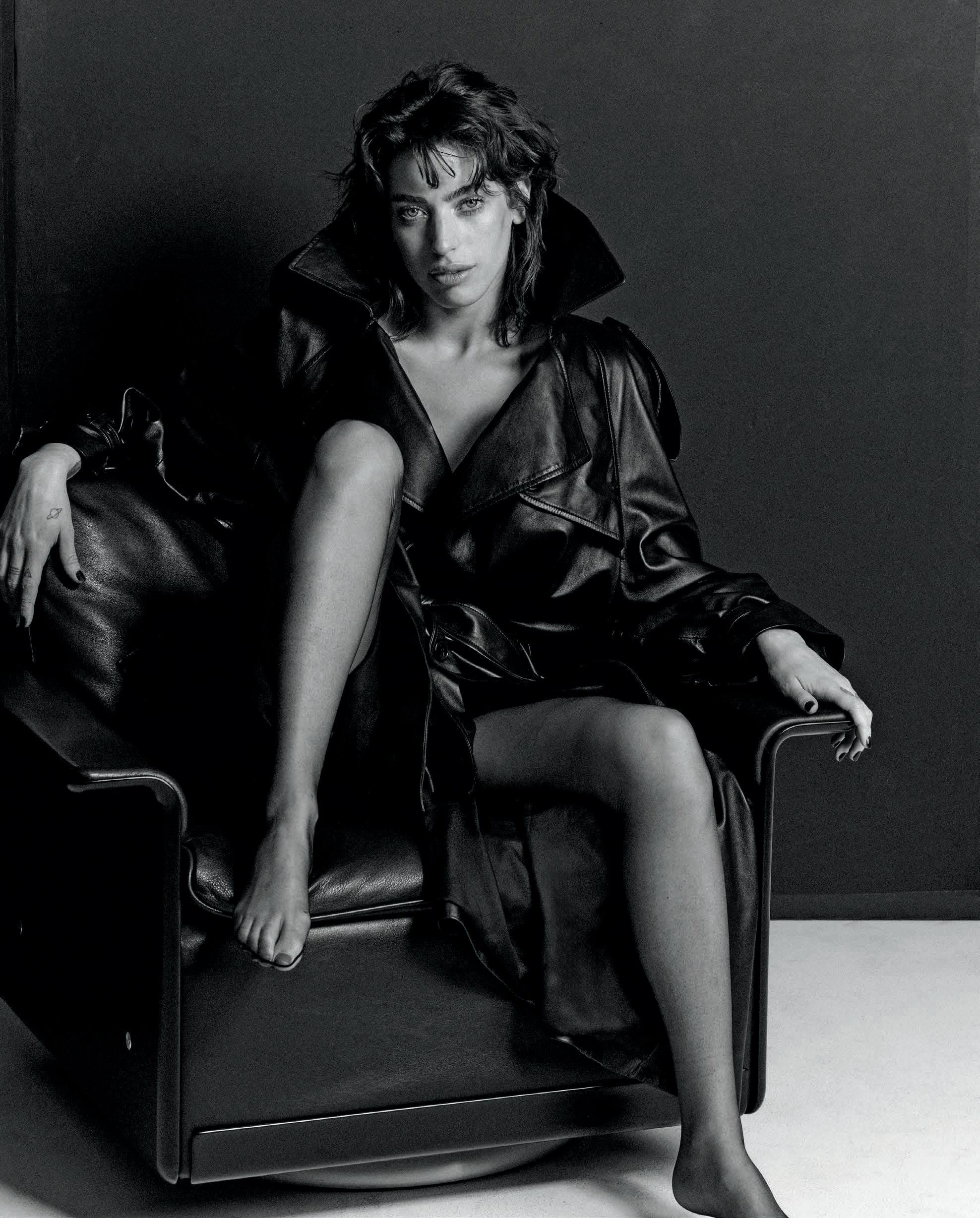

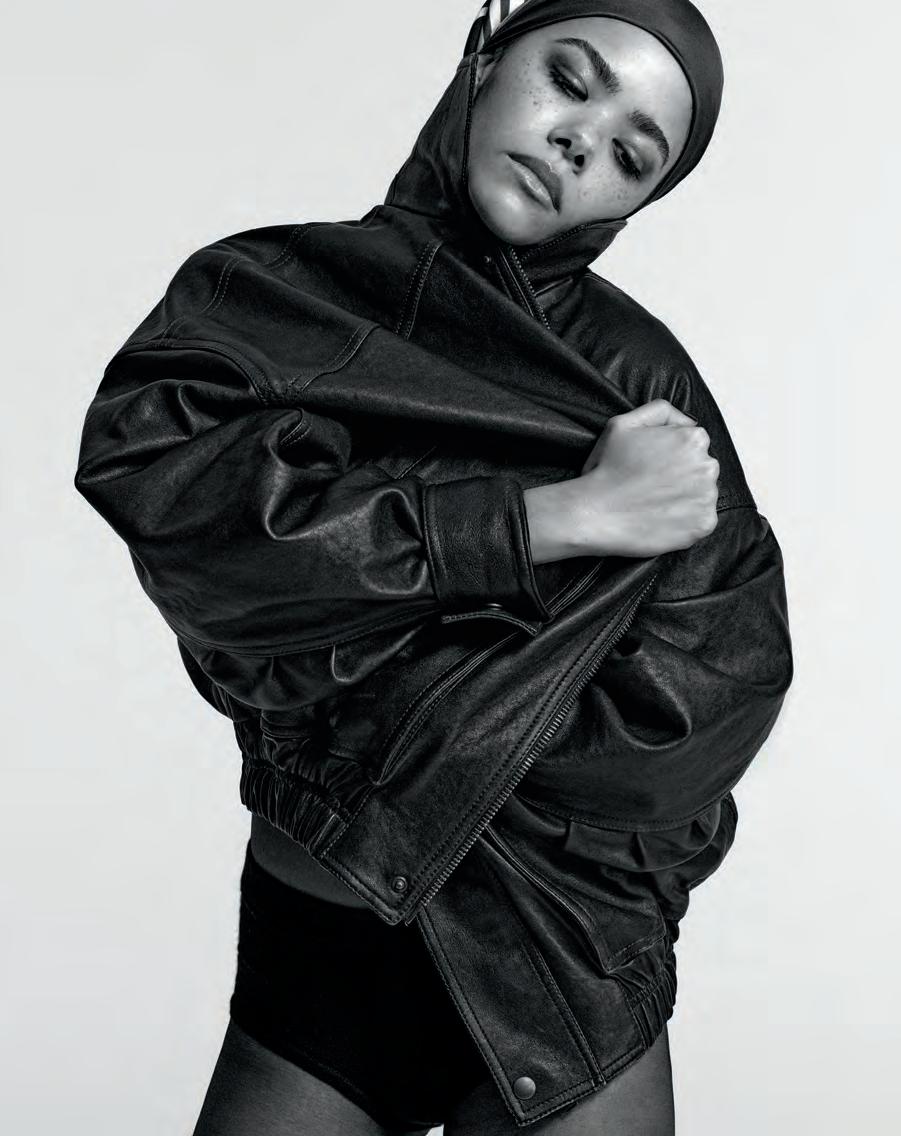

MARISA ABELA ON THE ART OF LOSING CONTROL

The 28-year-old actor holds her own against Cate Blanchett and Michael Fassbender in Steven Soderbergh’s new spy flick.

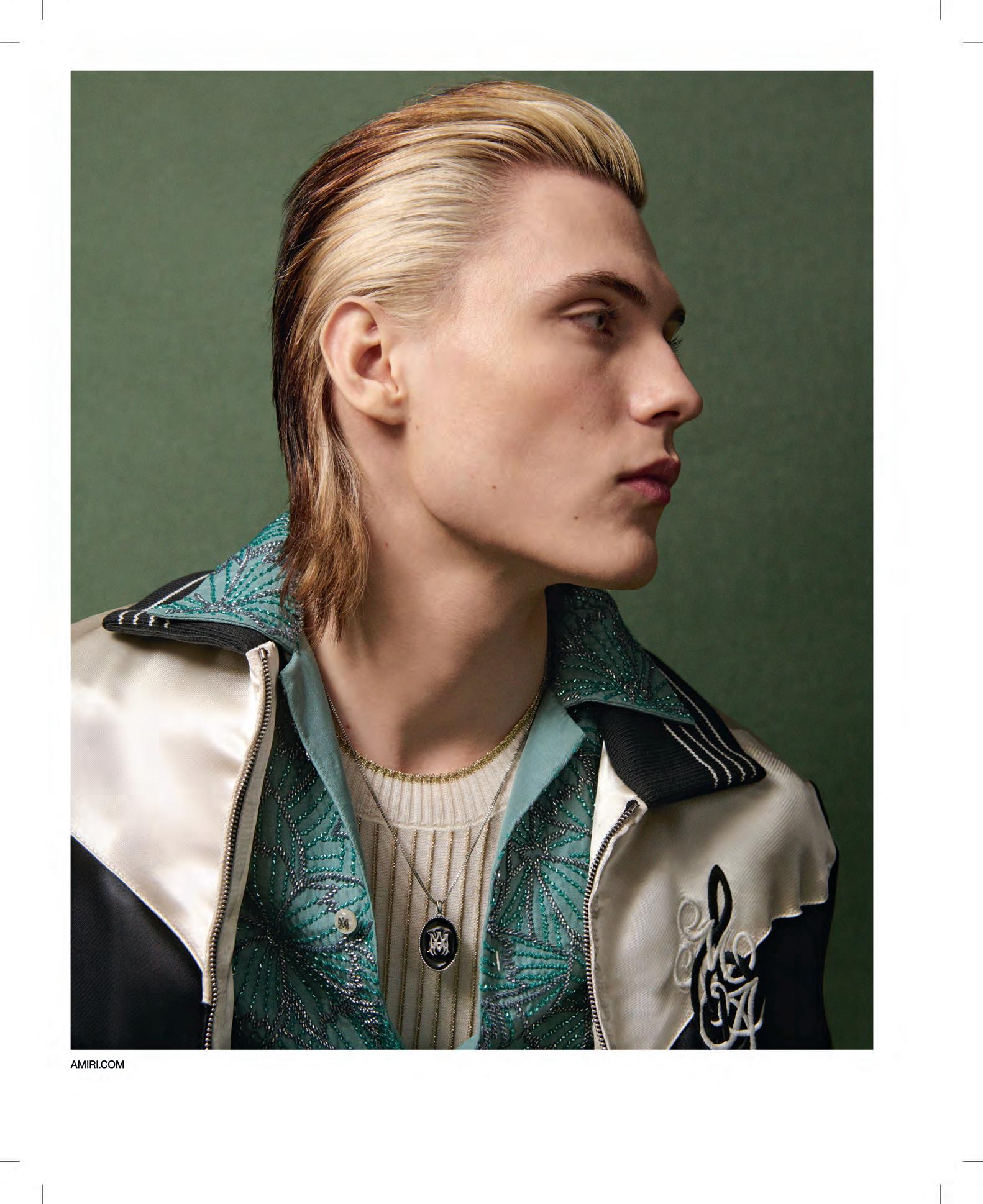

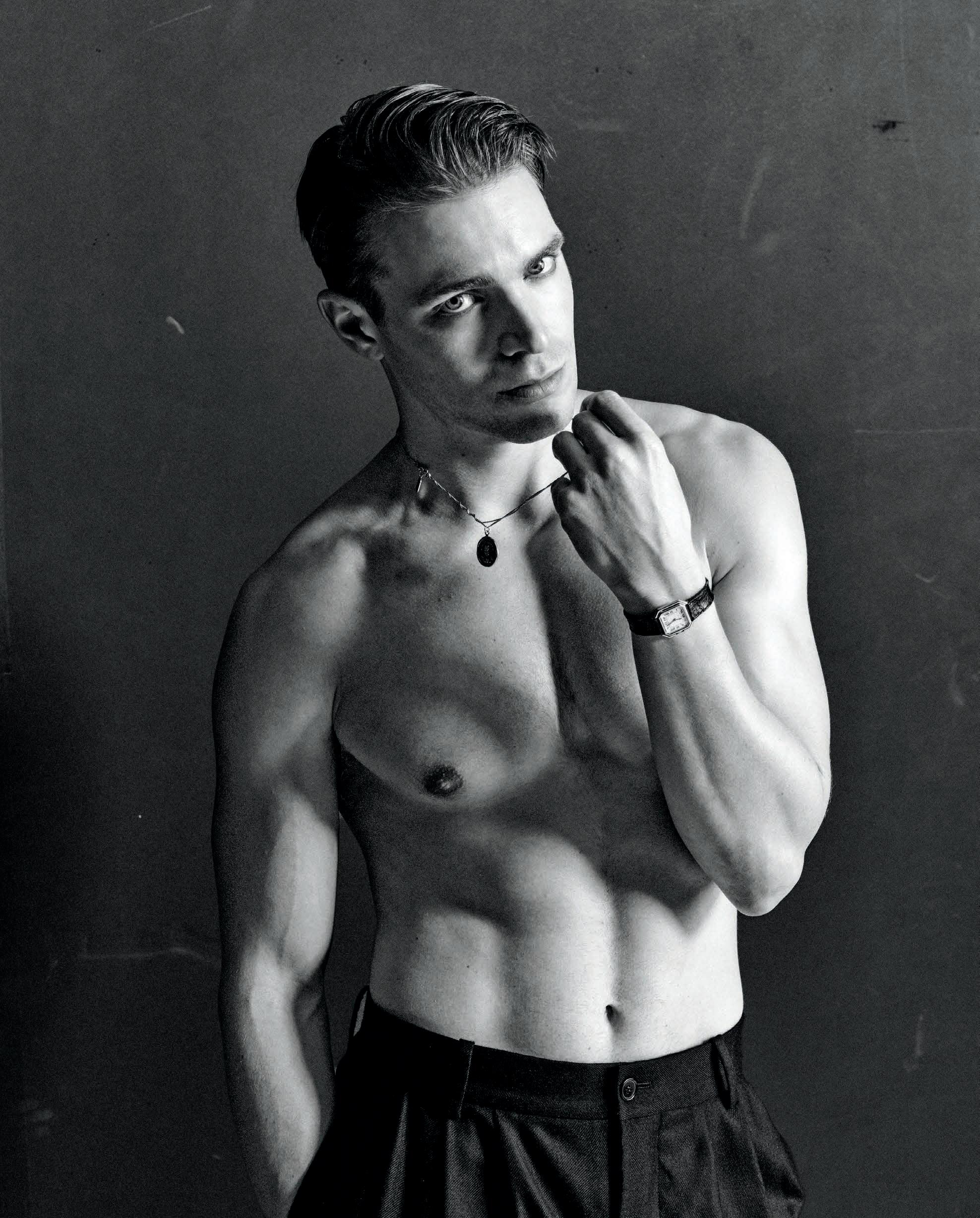

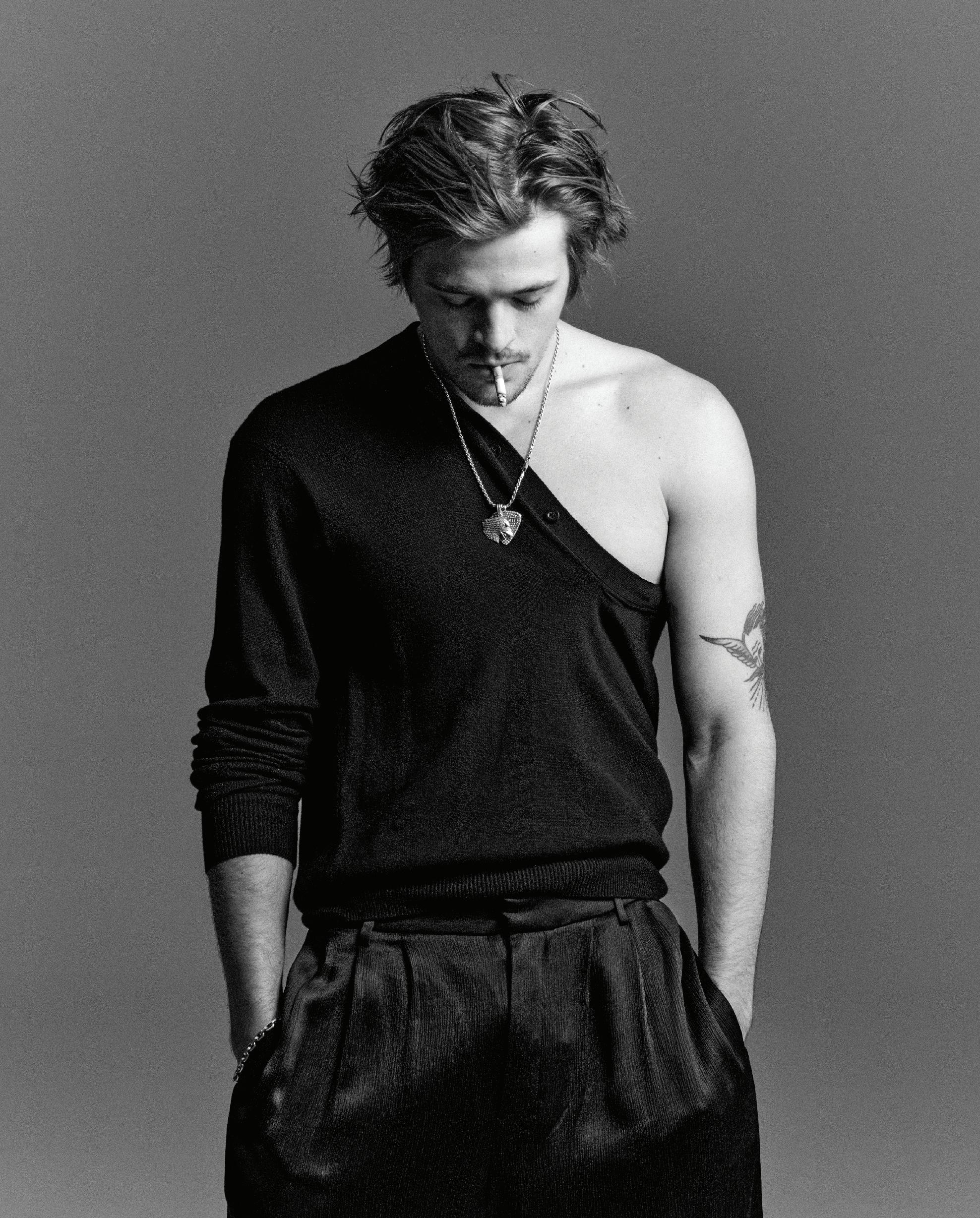

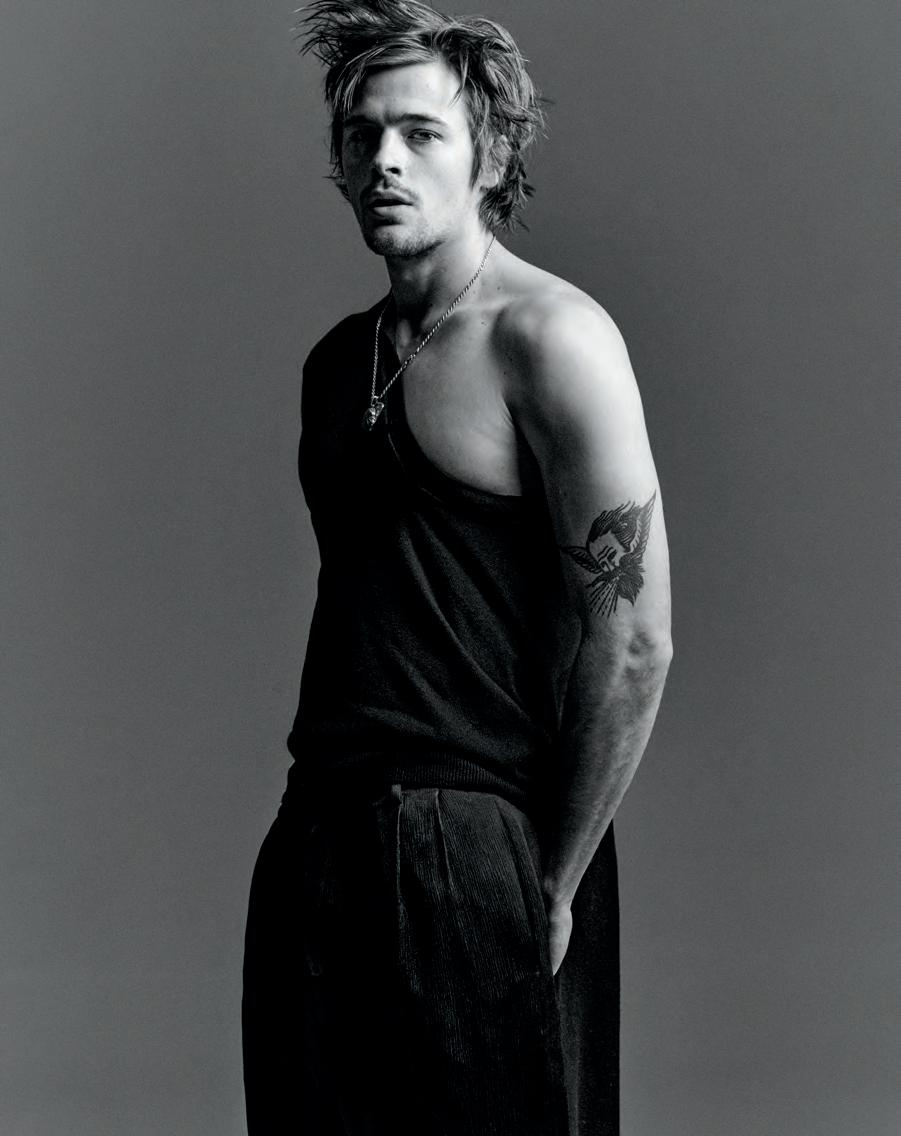

HOLLYWOOD’S NEW GUARD

In a culture quick to dole out attention, true fame—that alchemic mixture of mystique and staying power—feels more elusive than ever.

February / March 2025

148

152

158

162

LUCA GUADAGNINO’S GRAND DESIGNS

The filmmaker picks the brain of an artist he’s long admired—German photographer Thomas Ruff.

THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS

Following the breakout success of his latest film, Anora, Sean Baker has solidified his status as the consummate outsider-insider.

CALL HER DADDY

In her zeitgeisty follow-up to 2022’s Bodies Bodies Bodies, director Halina Reijn skewers the sexual topography of middle age.

FLEA MARKET TREASURES FIND A HOME IN THIS HOLLYWOOD HILLS OASIS

Benjamin Trigano’s Los Angeles home, a 1933 construction teetering over Lake Hollywood, is defined by its eclecticism.

170

THREE FASHION CRITICS ON THE FUTURE OF THE FIELD

CULTURED hosts three leading voices —Tim Blanks, Vanessa Friedman, and Rachel Tashjian to compare notes on the changing landscape of fashion journalism.

176

182

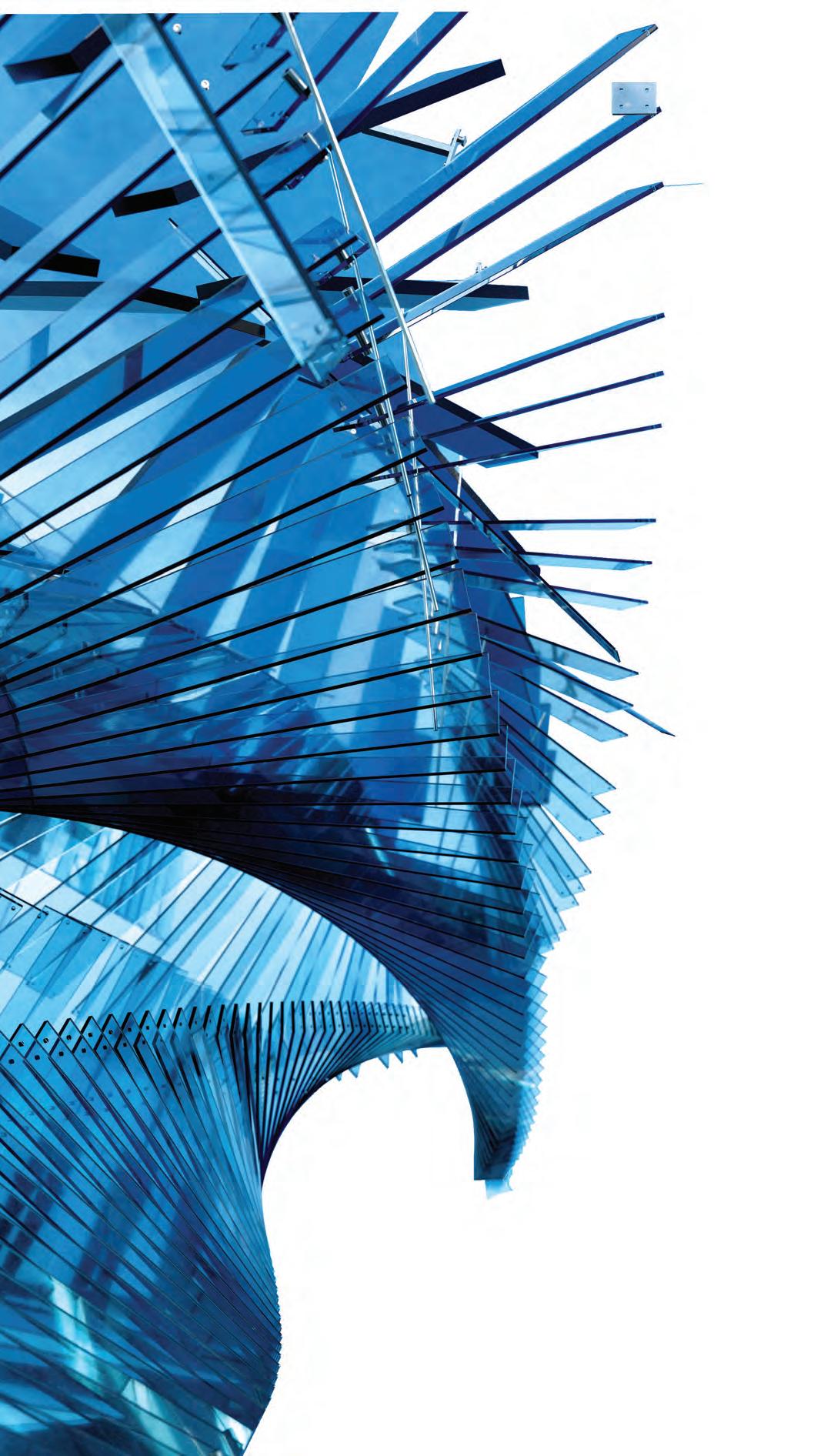

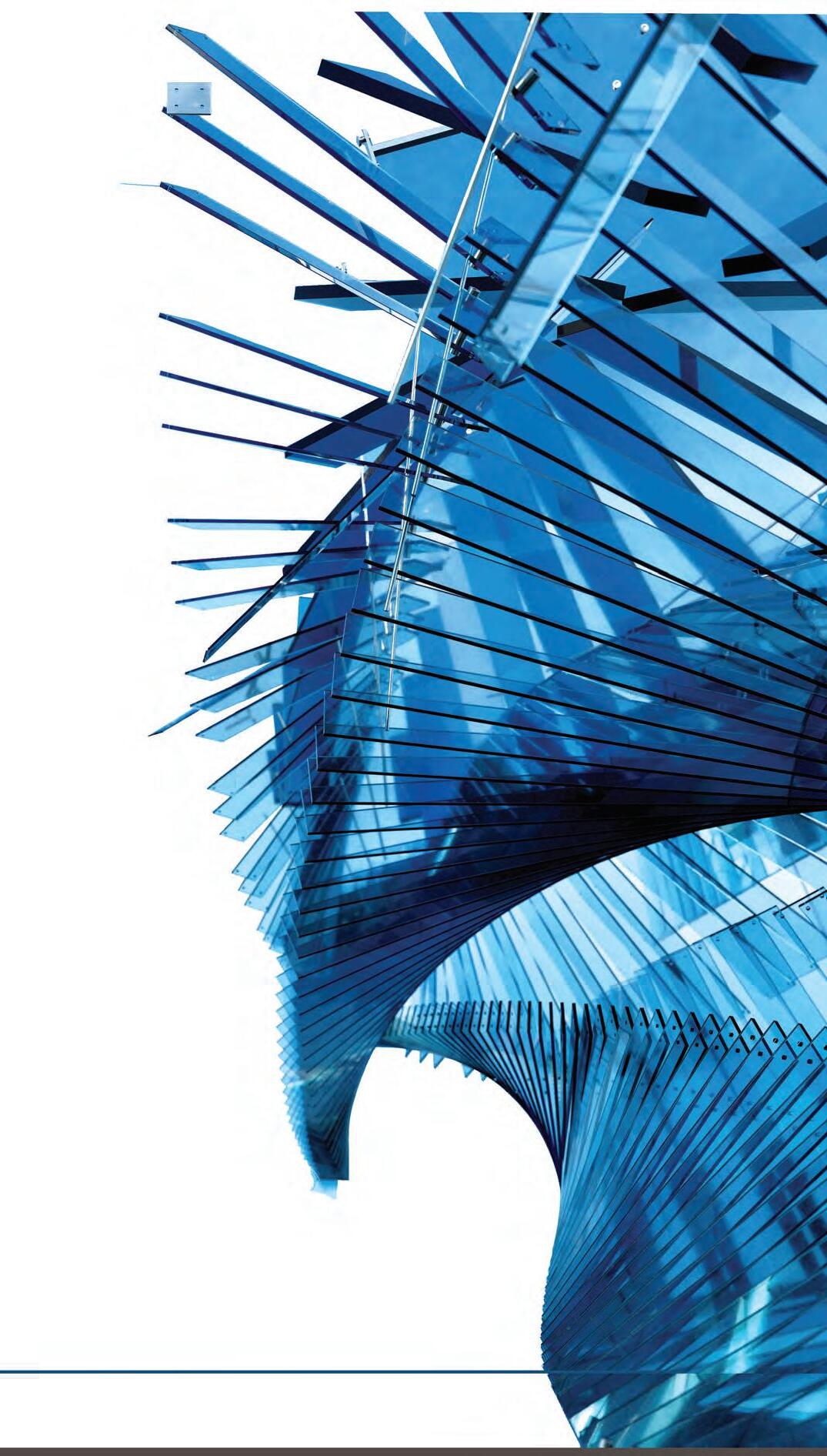

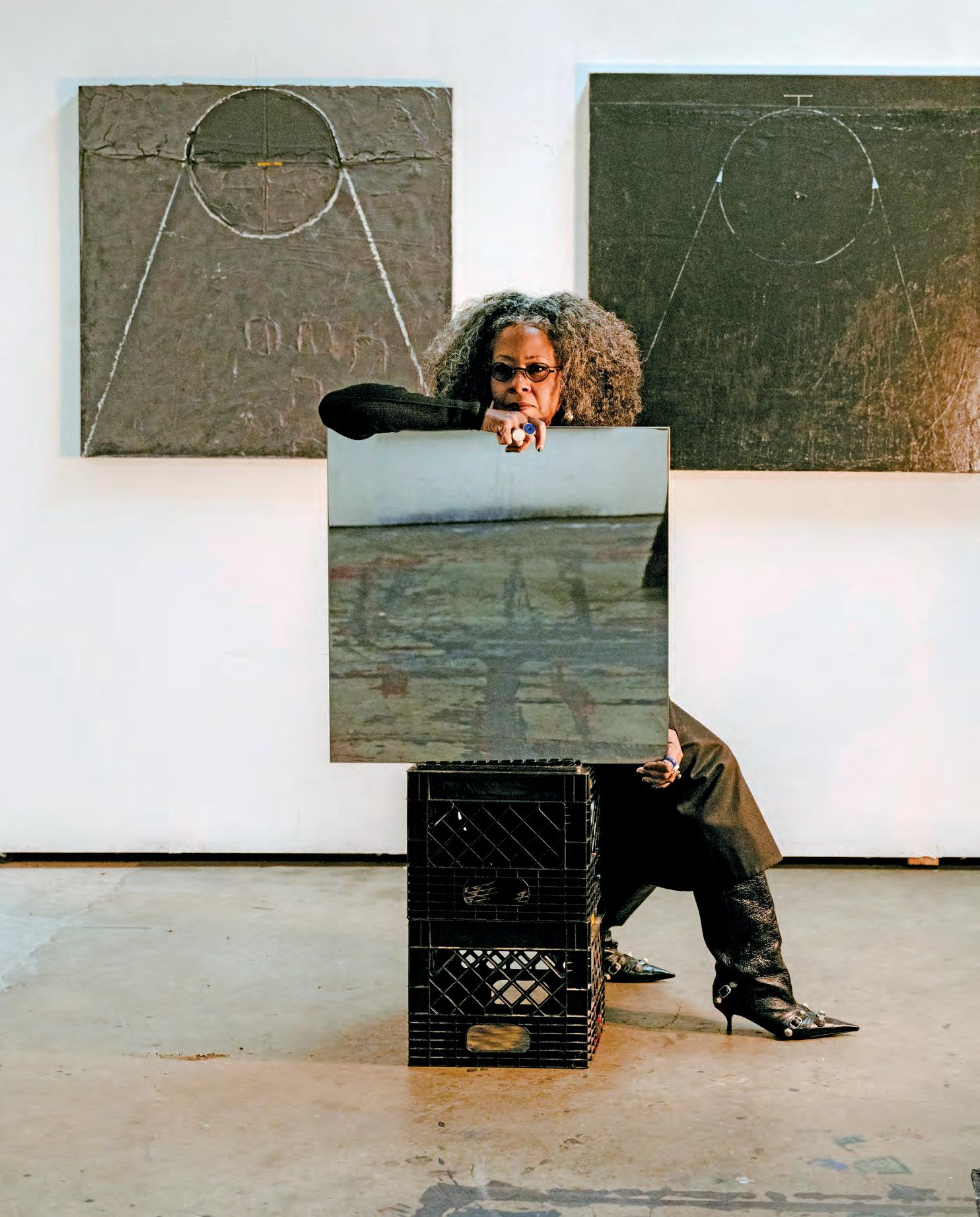

SURVIVING AB STRACTION, ONE SCULPTURE AT A TIME

This spring, Torkwase Dyson will bring her transhistorical, sensory-forward touch to two New York institutions: the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Brooklyn Bridge Park.

IT’S OUR HOUSE

Artist Alvaro Barrington and Ferragamo

Creative Director Maximilian Davis compare notes on translating cultural authenticity into something tangible.

188

192

198

ADAM PEN DLETON AND KWAME ONWUACHI DREAM ON

The visual artist and chef, who share a penchant for pushing boundaries in their respective mediums, discuss food as art and art as food.

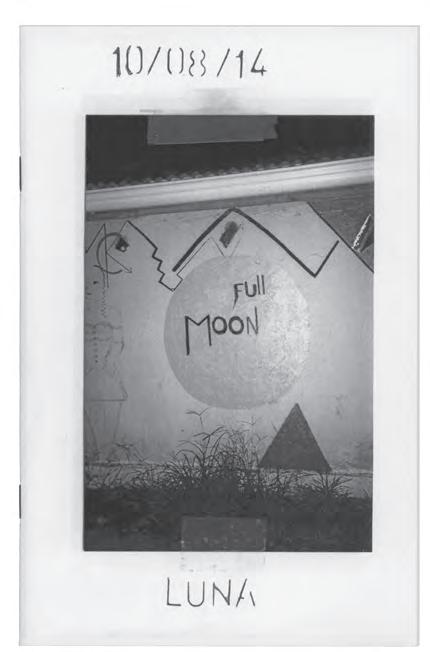

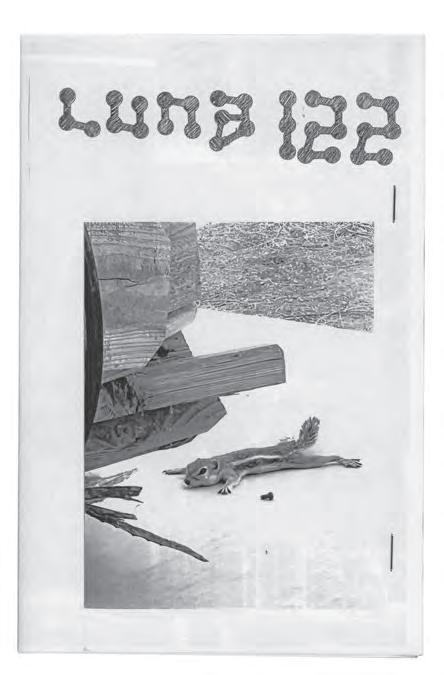

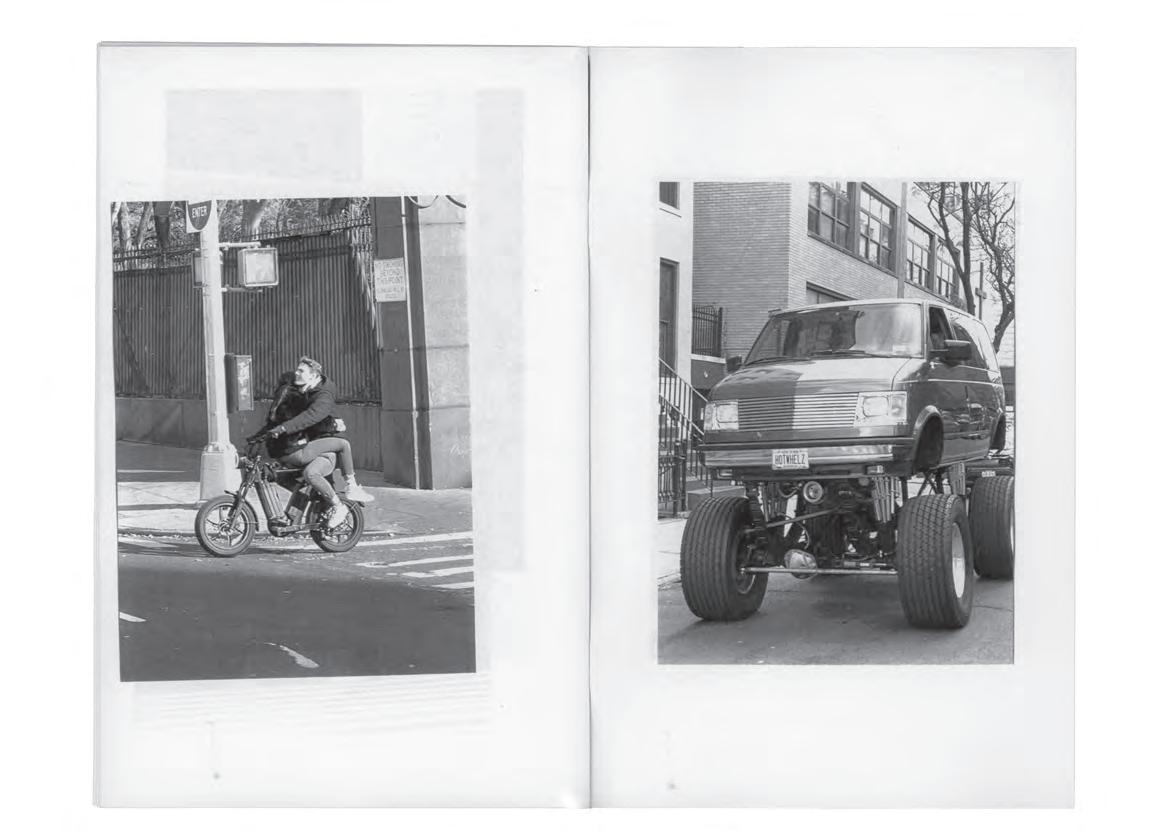

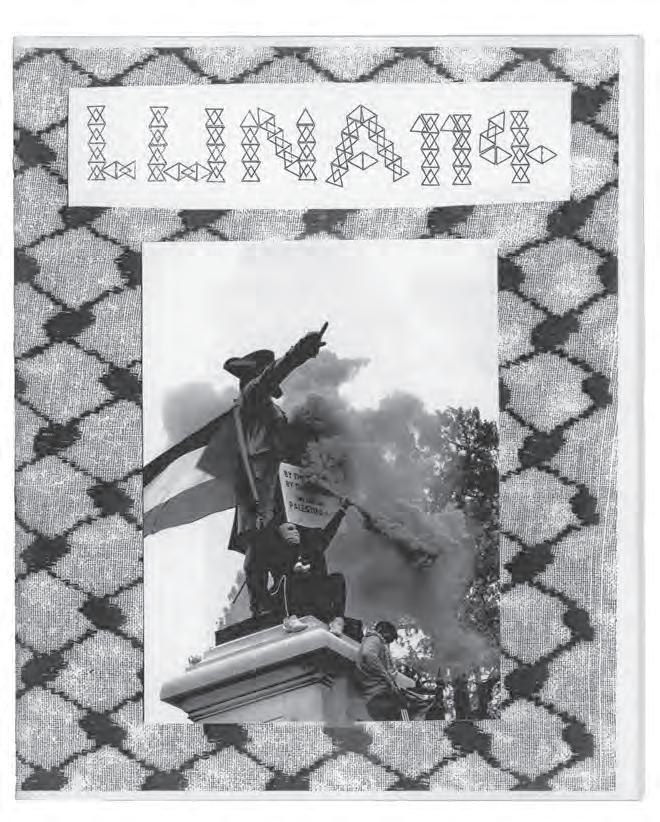

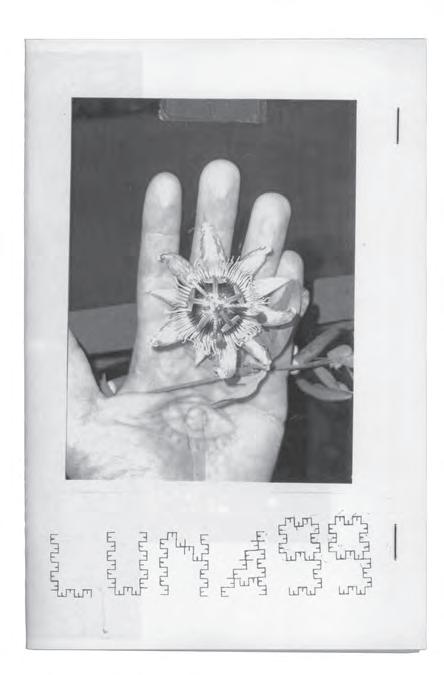

ASKING FOR THE MOON

Cult zine-maker Lele Saveri’s decade-long ode to the lunar cycle gets the monograph treatment.

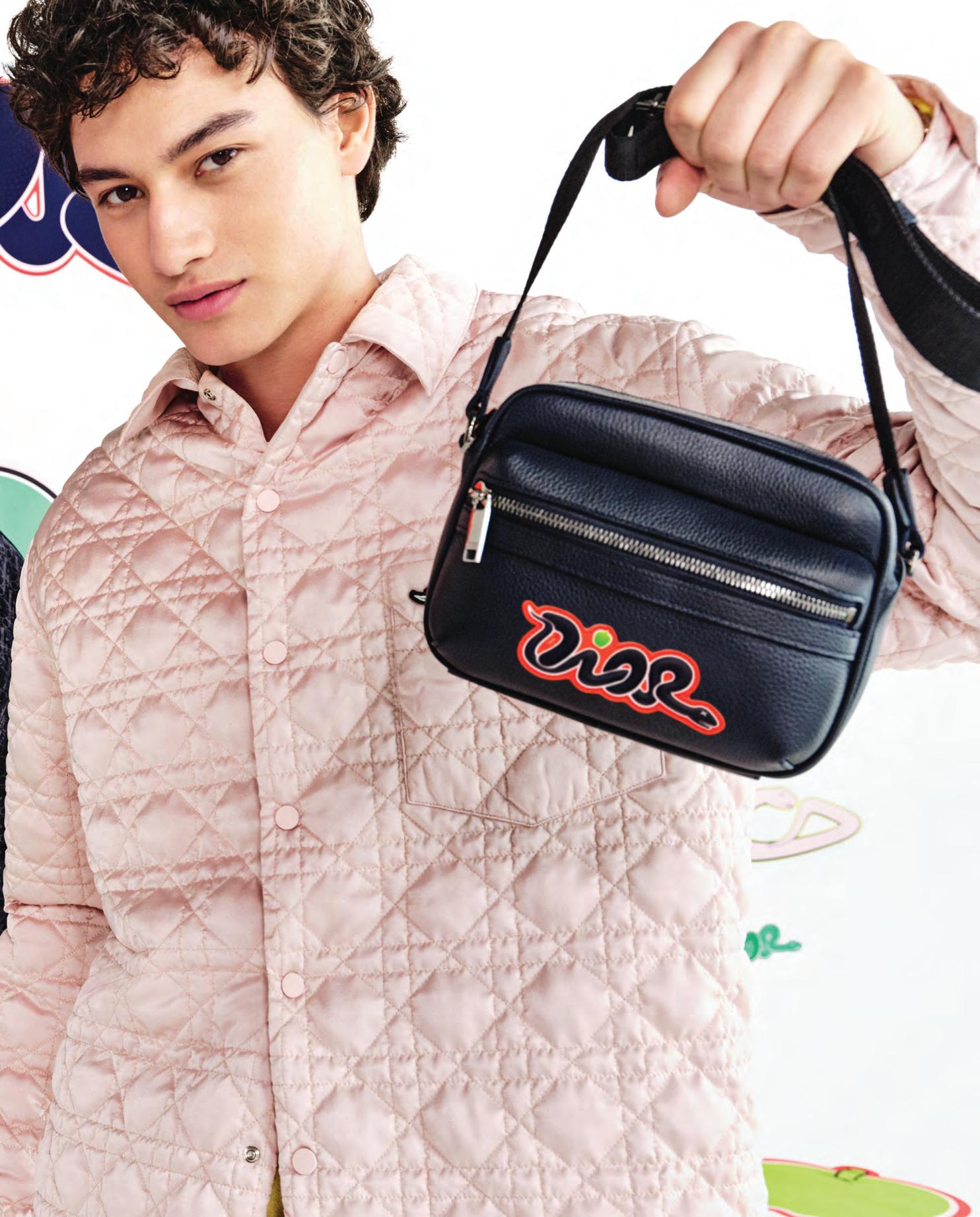

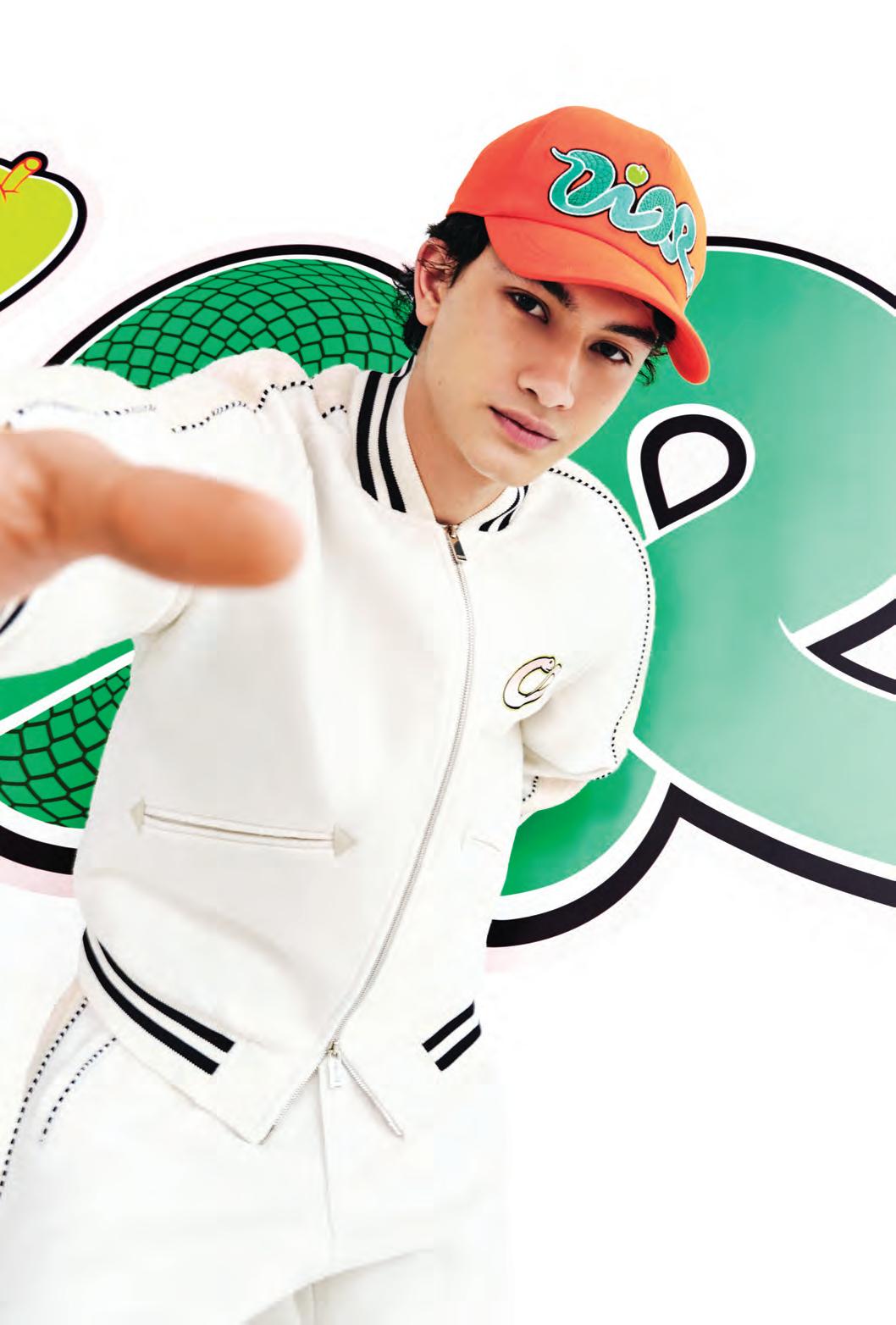

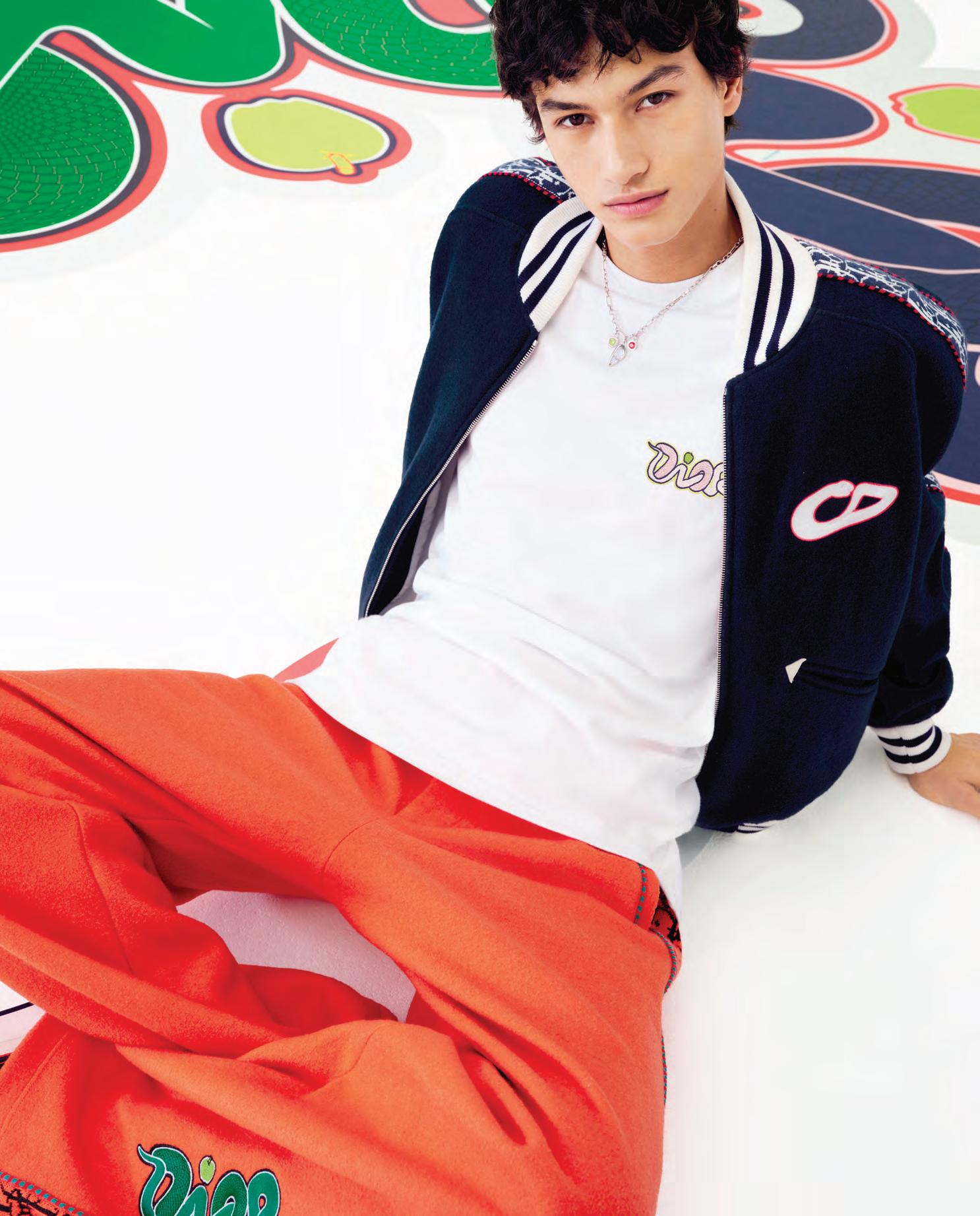

NAME BRAND

Dior’s latest capsule collection blends the indomitable spirit of its founder with KAWS’s high-octane flair—all under the watchful eye of creative director Kim Jones.

This issue was put together under extraordinary circumstances. Los Angeles has been one of CULTURED ’s home bases for over five years. In January, as wildfires tore through the city, so many of the artists and creatives featured in these pages and throughout the magazine’s history lost homes, studios, and their life’s work.

Against that heartbreaking backdrop, we assembled our annual Art & Film issue—a love letter to two of Los Angeles’s most potent cultural forces. We spoke to artists forging ahead for this year’s edition of Frieze Los Angeles, to actors who continue to love and fight for a place in the annals of cinematic history, and to curators at the city’s museums and galleries.

“In light of the fires that have caused such inconceivable devastation in Los Angeles, giving and sharing things that can hold memory feels more important than ever,” says artist Claire Chambless, who will be showing an LA-focused work as part of Frieze Projects, in the issue. As you’ll see in these pages, the city’s creative community is resolute—art will still be made in LA no matter what.

“IN LIGHT OF THE FIRES THAT HAVE CAUSED SUCH INCONCEIVABLE DEVASTATION IN LOS ANGELES, GIVING AND SHARING THINGS THAT CAN HOLD MEMORY FEELS MORE IMPORTANT THAN EVER.”

—CLAIRE CHAMBLESS

The same can be said of Hollywood. The industry remains committed to celebrating the year in film with a slew of awards shows in American cinema’s spiritual home. This issue’s cover stars—director Luca Guadagnino, and actors Fernanda Torres, Marisa Abela, and Cristin Milioti—are leaving indelible marks on the industry from both near and far.

In Lisbon, Torres told writer Raven Smith about her star-making turn in I’m Still Here. In Milan, Guadagnino sat down for a conversation with one of his favorite photographers, Thomas Ruff.

“I think it’s a rarefied experience, being met by a serious work of art in any medium,” he told the artist. “But we always have hope.” In London, Abela, a rising star, gave us an inside look at her new film with Steven Soderbergh, while Milioti met CULTURED in New York to discuss a career spent leaping from theater to television and back again.

We hope you’ll spend some time with this issue, no matter where in the world you find it.

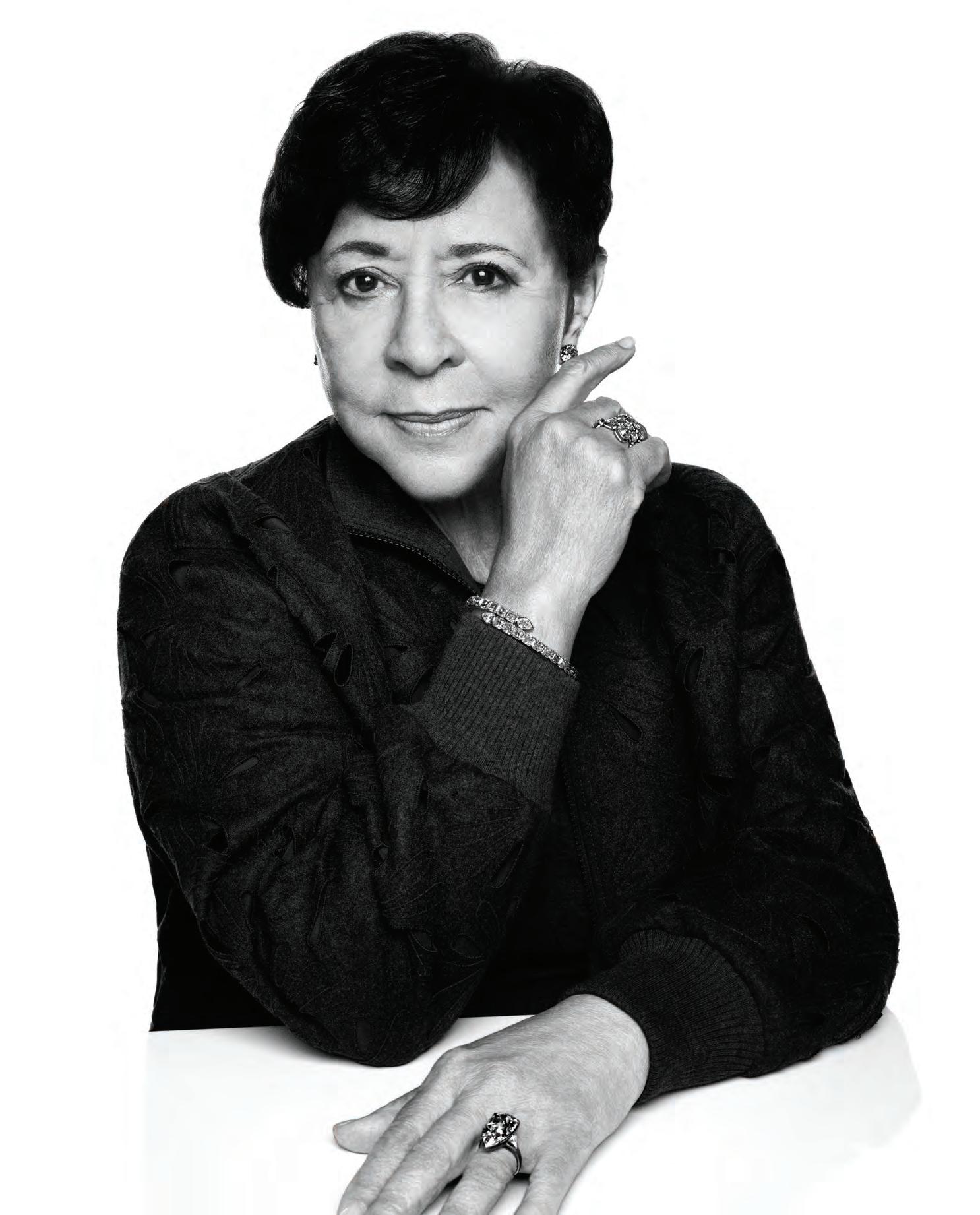

Sarah G. Harrelson Founder and Editor-in-Chief

@sarahgharrelson | @cultured_mag

Writer

Who do you enlist to speak to a director currently in the throes of promoting a box office hit? A writer who has recently turned to filmmaking herself. Durga Chew-Bose—author of the 2017 book of essays Too Much and Not the Mood and contributor to The Guardian, GQ, and other publications—is currently preparing for the summer 2025 release of her directorial debut and festival circuit darling, an adaptation of Françoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse. Ahead of the rush, Chew-Bose sat down with Halina Reijn, the filmmaker behind Bodies Bodies Bodies and last winter’s Babygirl. “Catching up with Halina during her whirlwind Babygirl tour was an education in staying candid and heartfelt amid the chaos,” says Chew-Bose. “Halina is so committed to her art, instinctive and free. Her curiosity comes from a place of compassion.”

Writer

“Thank goodness I watched all of Industry over one snowy week this winter,” says writer Haley Mlotek, who spoke to actor Marisa Abela for this issue. “This is surely a sign that no excessive binge-watching ever goes unrewarded.” Abela first broke through on the high-octane finance drama before leading last year’s Amy Winehouse biopic Back to Black and joining Steven Soderbergh’s latest thriller, Black Bag, out next month. “I leapt at the chance to interview Marisa—who played my favorite [Industry] character, Yasmin— when the opportunity came,” continues Mlotek, whose own industry breakthrough, No Fault: A Memoir of Romance and Divorce, drops this month.

Writer

Liana Satenstein has been examining the wardrobes and iconic garments of the sartorial set for more than a decade. The former Vogue senior editor (now contributor) is the creative behind #NEVERWORNS, a hybrid Substack, podcast, and YouTube channel that helps visitors “learn something about responsibly shopping as well as getting the most out of your closet.” For this issue,

Satenstein took on a garment that fills the closets and coat racks of half of New York: the Burberry trench coat. “It-items fade, but the Burberry trench stays,” she says. “It’s the ultimate classic, and it can give any messy look some blasé posh polish. Long live the Burb piece. In fact, get drenched in it!”

Stylist

As a stylist, creative director, beauty editor, and more, Dione Davis has seen the fashion industry from every angle. Her editorial projects—with Vogue Netherlands, Numéro, and more—prize sleek tailoring and immersive settings. For this issue, Davis turned her attention to I’m Still Here star Fernanda Torres, catching the Brazilian actor in the Financial District’s new cultural hub WSA. “The shoot captured Fernanda unwinding post-event with looks as polished as her scene partners,” says Davis. “Prada evoked Old Hollywood glam, and the airy Ferragamo jumpsuit paired with Tiffany jewelry balanced elegance and movement.”

“The shoot captured Fernanda unwinding post-event with looks as polished as her scene partners.”—Dione Davis

With its powerful combination of Triple RGB-laser, Leica Summicron zoom lens, and Leica Image Optimization (LIO™), the Leica Cine Play 1 delivers stunning 4K images with exceptional brightness and vivid colors.

COLE WILSON

Photographer

Photographer Cole Wilson captured the industrial glory of artist Torkwase Dyson’s Beacon, New York, studio for this issue. “We threw on an old Art Ensemble of Chicago record to kick things off, followed by some Coltrane and Brian Eno,” the photographer recalls of the shoot. Wilson—who has shot for Adidas, The New Yorker, Reebok, and others—traveled from his base in Kingston to meet Dyson on a snowy winter day. “I think the music helped us both. From the get-go, Torkwase

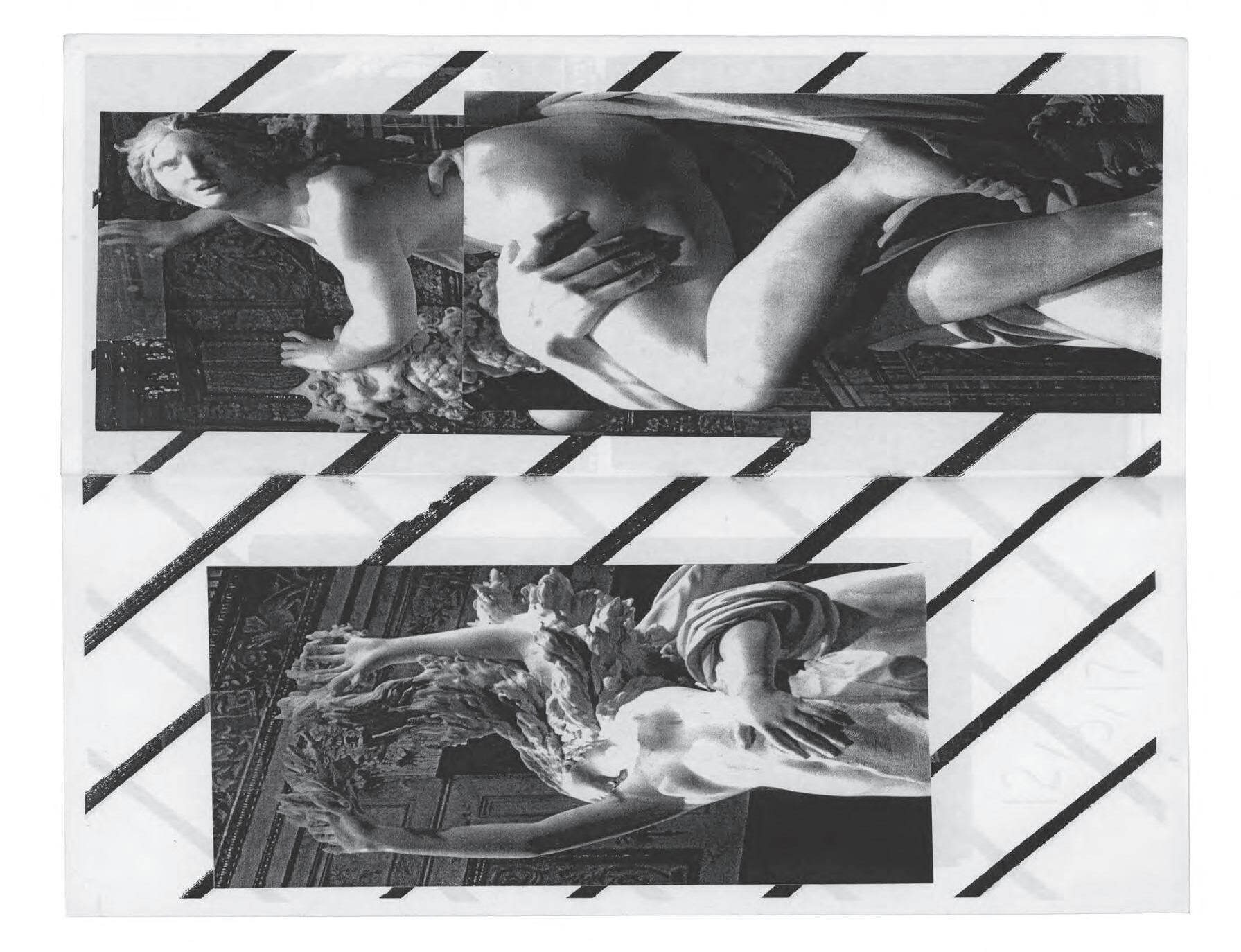

THOMAS RUFF Artist

“I want to deconstruct, in a way, these kinds of official images, these official lies,” Thomas Ruff told director Luca Guadagnino when the two sat down in conversation for this issue. The statement could easily serve as a thesis for the artist’s long-standing practice. First emerging in the 1980s as part of the Düsseldorf School, Ruff has torn apart both photographic conventions and political propaganda in his sharp, blown-up imagery. Series like “d.o.p.e.” and “nudes” likewise put our hidden proclivities—sex and drug-induced trips—on display. His work is held in the collections of institutions including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, as well as that of his longtime fan Guadagnino.

“Natasha spoke about vulnerability, creative expansion, and her deliberate approach to representation in the industry. I watched her embody the very qualities she champions in her work.”

—Rachel Cargle

was engaged and excited to collaborate with me to make images that felt unique and authentic. She was excited to do something out of the ordinary and came ready with ideas to discuss together.”

“From

the get-go, Torkwase was engaged and excited to collaborate with me to make images that felt unique and authentic.”

RACHEL CARGLE

Writer

“Talking with Natasha Rothwell was a master class in authenticity,” says writer Rachel Cargle, who sat down with the actor to discuss her recent ascent in Hollywood. “She spoke about vulnerability, creative expansion, and her deliberate approach to representation in the industry. I watched her embody the very qualities she champions in her work.” Cargle, for her part, has been pursuing equity through her own Loveland Foundation, which offers free therapy to Black women and girls, and through her recent programming series For Those Who Gather. In 2023, she released her first book, A Renaissance of Our Own, a memoir and manifesto on reimagining oppressive societal structures.

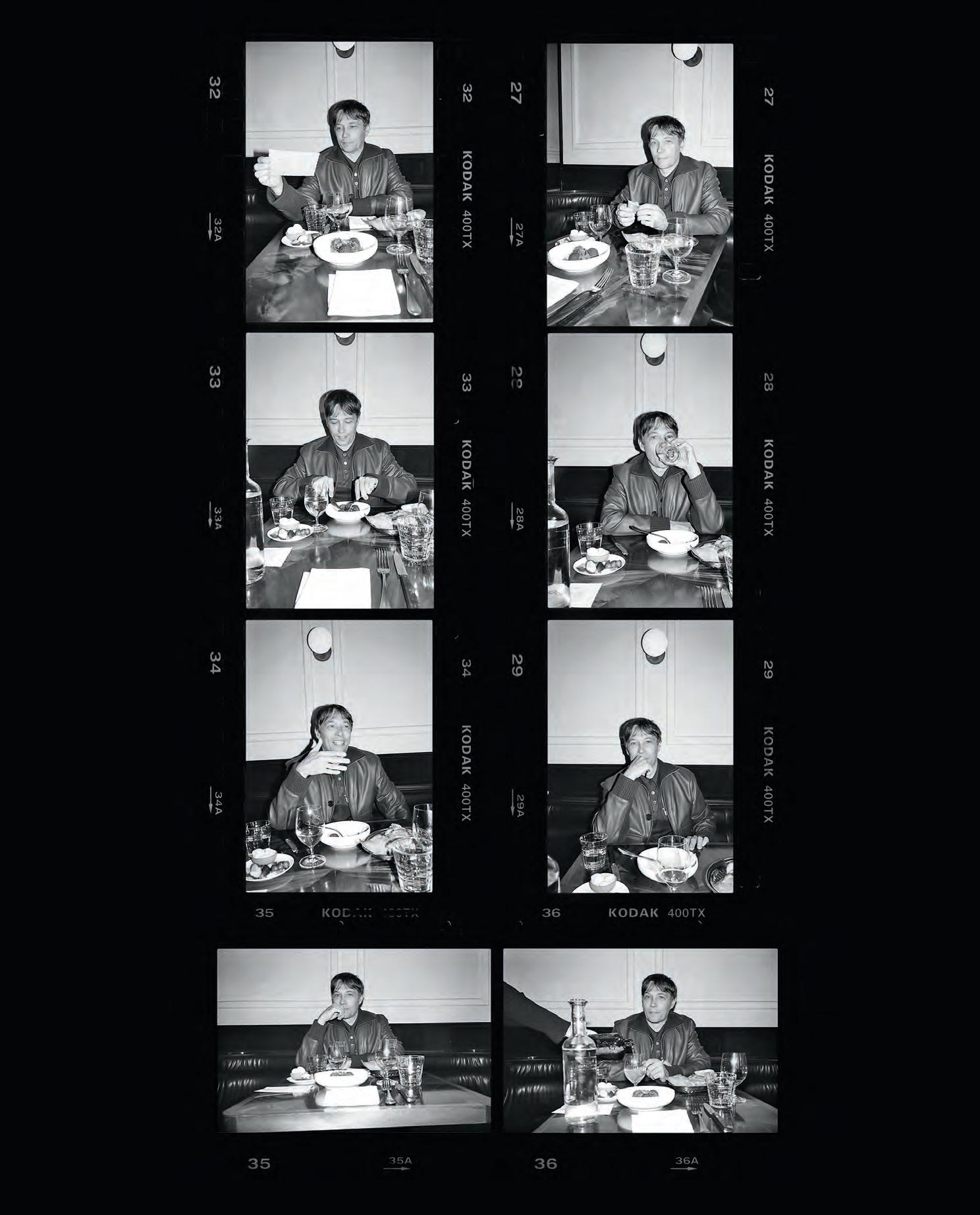

ANDREW DE FRANCESCO Photographer

“I wanted these portraits to underscore how seamlessly Hong Gyu Shin incorporates art into his everyday life,” says photographer Andrew De Francesco of the gallerist and collector he shot for this issue. De Francesco has worked with clients as disparate as the Standard, the United Nations, and Carolina Herrera, bringing the warmth of film photography to this

ELENA SAAVEDRA BUCKLEY Writer

“I love trying to understand a phenomenon as it’s taking shape, and that’s what it felt like watching Anora,” says Elena Saavedra Buckley, who spoke with director Sean Baker for this issue. Elsewhere, Buckley serves as a senior editor at Harper’s Magazine and has written for The Paris Review, The New Yorker, and other publications. “Baker’s brash but deceptively simple movie became a sensation and then an object of scrutiny, but no one, it seemed, could agree on exactly what to criticize about it,” continues Buckley. “Then Baker himself became the confusing phenomenon—a long-hustling, innovative director cresting into seemingly inevitable stardom, with audiences enthralled and confused at his refusal to easily moralize. I loved talking to him for CULTURED as he stumbled into this new reality.”

range of projects. That adaptable sensibility made the photographer a fitting choice to shoot Shin’s collection, which features works by artists from across centuries, including Van Gogh, Balthus, and others.

“By engaging with his collection as effortlessly as he does,” says De Francesco, “Shin adds a human element to what most of us see as rarefied and sublime.”

STAPLETON Photographer

The art-filled home of collector Benjamin Trigano is nestled in the hillside above Los Angeles’s Lake Hollywood. For this issue, photographer Rich Stapleton visited the rambling, seven-floor abode to shoot a few sun-soaked images of the interiors and Trigano’s collection. “Benjamin’s home is fascinating,” he says, “a treasure trove of sorts. Collections of eclectic art and objects [are] scattered around the house: matchboxes, marbles, cookie jars, chess sets.” Stapleton is the co-founder of Cereal magazine, and his latest photography book, Penumbra, was released last year.

RAVEN SMITH Writer

“Interviewing Fernanda was a dream,” says writer Raven Smith of his subject for this issue, Brazilian actor Fernanda Torres. “She’s so easy and effortless, frank and direct, which speaks to her seasoned career.” Smith shares a similar set of qualities across his various magazine columns and books—his most recent output, Raven Smith’s Men, followed two years after his 2020 bestseller Raven Smith’s Trivial Pursuits. Of his feature for the issue, the Vogue columnist says, “It’s both exhilarating and reassuring that Fernanda is finally getting so much attention outside of her homeland!”

SARAH G. HARRELSON Founder, Editor-in-Chief

MARA VEITCH Executive Editor

JOHN VINCLER Co-Chief Art Critic and Consulting Editor

ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT Senior Editor

SOPHIA COHEN Arts Editor-at-Large

DELIA CAI Culture Writer

JACOBA URIST New York Arts Editor

KAREN WONG Contributing Architecture Editor

COLIN KING Design Editor-at-Large

ALEXANDRA CRONAN

KATE FOLEY Fashion Directors-at-Large

GEORGINA COHEN European Contributor

KRISTIN CORPUZ Social Media Editor

NICOLAIA RIPS

CAT DAWSON

DEVAN DÍAZ

ADAM ELI

ARTHUR LUBOW

HARMONY HOLIDAY

LAURA MAY TODD

EMMA LEIGH MACDONALD

LIANA SATENSTEIN Writers-at-Large

EMILY DOUGHERTY

DOMINIQUE CLAYTON

RACHEL CORBETT

KAT HERRIMAN

JOHN ORTVED

SARA ROFFINO

YASHUA SIMMONS Contributing Editors

JULIA HALPERIN Editor-at-Large

JOHANNA FATEMAN Co-Chief Art Critic and Commissioning Editor

ALI PEW Fashion Editor-at-Large

JASON BOLDEN Style Editor-at-Large

SOPHIE LEE Associate Digital Editor

CRISTINA MACAYA Editorial Assistant

MINA STONE Food Editor

EMMELINE CLEIN Books Editor

SPECIAL PROJECTS Contributing Casting Directors

EVELINE CHAO Senior Copy Editor

ROXY SORKIN Lifestyle Columnist

SIMON RENGGLI CHAD POWELL Art Directors

HANNAH TACHER Junior Art Director

JAMESON BALDWIN Production Coordinator

CAROL SMITH Strategic Advisor

MAYA BODDIE

GIULINA BRIDA

MADISON COLLINS

NICOLE HUR

KATIE KERN

DANIELLE ORTIZ

STEPHANIE WONG Interns

CARL KIESEL Vice President, Chief Revenue Officer

LORI WARRINER Vice President of Sales, Art + Fashion

DESMOND SMALLEY Director of Brand Partnerships

HAILEY POWERS

Marketing and Sales Associate

CARLO FIORUCCI Italian Representative, Design

ETHAN ELKINS

DADA GOLDBERG Public Relations

AMANDA GILLENTINE

Marketing and Partnerships Consultant

PRIYA NAT Sales Consultant, Home + Travel

PETE JACATY & ASSOCIATES Prepress/Print Production

BERT MOO-YOUNG Senior Photo Retoucher

JOSÉ A. ALVARADO JR.

SEAN DAVIDSON

SOPHIE ELGORT

ADAM FRIEDLANDER

JULIE GOLDSTONE

WILLIAM JESS LAIRD

GILLIAN LAUB

YOSHIHIRO MAKINO

LEE MARY MANNING

BJÖRN WALLANDER

BRAD TORCHIA

Contributing Photographers

February/March 2025

VSF DALLAS

“ALICE’S

Jonny Greenwood of Radiohead has cited her as an influence. She shared the stage with musicians as disparate as Carlos Santana and Pharoah Sanders. Along with her contemporary Dorothy Ashby, she introduced one of music’s most ancient instruments, the harp, into the jazz canon. Yet, during most of her lifetime, Alice Coltrane’s contributions were not considered part of the jazz canon themselves, eclipsed by the monument that was her husband, John Coltrane. That’s changing, according to curator Erin Christovale. “I feel like, in recent years, her output is being recognized by a larger audience and her impact as an individual … is taking form,” she says. “Alice’s music and cultural legacy transcend time and space.”

At the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, the curator has orchestrated “Alice Coltrane, Monument Eternal,” the first institutional exhibition dedicated to the late jazz musician and devotional leader’s legacy. Alongside rarely or never-before-seen pieces from her archive—including letters, unreleased recordings, and video footage—are works by 19 American artists that flesh out her world and impact.

“Monument Eternal,” on view through May 4, takes its title from Coltrane’s 1977 book of the same name, which elucidated her spiritual beliefs and musical practice, particularly as one of jazz’s few harpists. The show mirrors the text’s themes with three sections: Sonic Innovation, Spiritual Transcendence, and Architectural Intimacy. Works, both new and archival, from the likes of Rashid Johnson, Jasper Marsalis, Cauleen Smith, Martine Syms, and more fill each space.

“Alice was such a multivalent being, so there’s so much to learn,” continues Christovale. “Those who are more familiar with her jazz career will also have the opportunity to learn about her time as a spiritual guru and the Sai Anantam Ashram that she ran for decades in Agoura Hills. Those who are more familiar with her spiritual journey will be able to sit with her full discography and learn more about her musical musings.”

The museum’s typically hushed galleries will also come alive with music throughout the run

of the show. Performances every Sunday are a nod to Alice’s weekly services at the Sai Anantam Ashram, with Jeff Parker, Mary Lattimore, and more slated to make a showing. Christovale put together the program with help from Music Curator Ross Chait—and a little inspiration from Coltrane’s own community. “I started at the source,” Christovale reflects on the show’s genesis, “her incredible family, jazz community, and students of her ashram. You learn so much about a person through the photos, letters, books, and other traces they’ve left behind.”

THIS SPRING, THE GUGGENHEIM WILL OPEN A SHOW DEDICATED TO THE KALEIDOSCOPIC OEUVRE OF BEATRIZ MILHAZES.

By Katie Kern

“Art has the power to make human ties stronger and help us think, feel, and look at things differently,” says Beatriz Milhazes. “Art can change people, and people can change the world into a better one.” In New York this spring, the artist’s humanistic worldview will be at the center of her first solo exhibition at the Guggenheim, whose permanent collection features a sextet of works by the Brazilian artist.

Time spent with Milhazes’s intricately collaged paintings unveils hypnotic abstractions, undulating arabesques, and playful riffs on floral motifs. Synonymous with the Rio de Janeiro native’s practice is her innovative “monotransfer” technique, developed during experiments with acrylics in the ’80s. Milhazes creates designs on transparent sheets, which

are then transferred to canvas, producing reversed images. “A good process is when you create a dialogue with the work,” she remarks. “You cannot force something to happen nor follow what the picture is suggesting to you. Time and focus are the two main elements.”

“ART CAN CHANGE PEOPLE, AND PEOPLE CAN CHANGE THE WORLD INTO A BETTER ONE.”

In “Rigor and Beauty,” drawn from the Guggenheim’s holdings and key loans, and opening March 7, Milhazes traces this dialogue from the ’90s all the way to works completed as late as 2023. Throughout this artistic chronology, her influences—spanning Brazilian folklore, the decorative arts, regional spiritual

traditions, and artistic movements like Op Art and abstraction, as well as the work of Henri Matisse and Piet Mondrian—loom large, with Milhazes absorbing and interpreting their disparate styles into her own signature. Today, her oeuvre is as relevant as ever, evidenced by her recent inclusion in the 2024 Venice Biennale, created in collaboration with her fellow Brazilian, the curator Adriano Pedrosa. The Guggenheim exhibition will be an indispensable introduction for audiences who might not know her yet. “It is amazing the way these works will meet each other and how a strong and special confrontation is created,” Milhazes says of seeing the breadth of her career collected at the museum. “The superposition of layers of paint, an environment of colorful compositions, will diverge from a dark, melancholic atmosphere to an intricate, dense, multicolored one. There are almost 30 years between them.”

THE ADAGE GOES THAT PETS LOOK LIKE THEIR OWNERS—BUT WHEN IT COMES TO THE FASHION WORLD, WHERE APPEARANCE IS THE HIGHEST FORM OF EXPRESSION, THE CONNECTION RUNS EVEN DEEPER. HERE, FIVE SARTORIAL HEAVYWEIGHTS INTRODUCE CULTURED TO THEIR ANIMAL COMPANIONS.

Karl Lagerfeld’s Birman cat Choupette and Thom Browne’s dachshund Hector directly inspired some of their owners’ most beloved designs. Is it any surprise, then, that the pets of fashion-industry icons lead especially stylish and luxurious lives? From sirloin beef jerky to car rides to Southampton, the perks of being a fashion pet are legion. In the following pages, meet the beloved dogs (plus one turtle) of designers Emilia Wickstead, Tory Burch, and Laura Kim; PR extraordinaire Lucien Pagès; and T Magazine Editor-in-Chief Hanya Yanagihara.

How did you find each other? My father was having a late-life crisis and answered a Craigslist ad. Before my mother could say anything, he was paying Fred’s previous owner $250 and loading him into the back of the car.

What’s the most expensive thing your pet owns? He has a doghouse that my cousin built for him; he sleeps in there every night.

What’s Fred’s favorite pastime? Pacing around the lawn eating cactus leaves. He loves visitors—especially children.

His favorite place to be? Beneath the cup-and-saucer bush. It’s shady and dry there.

His snack of choice? Hibiscus flowers.

Most mischievous behavior? He continually humps a large rock; my parents have named the rock Wilma.

What fashion icon (dead or alive) does he channel? Quentin Crisp.

What nicknames does Margot respond to? None. She loves her full name.

What’s the most expensive thing your pet owns? Her leather, pleated collar. It matches the tone of her curls, and it has a gold heart with her name engraved on it.

Her favorite pastime? She trots instead of walking.

Her most cherished accessory? The red velvet bow attached to her collar.

Her favorite place? Hyde Park, or at the top of the staircase waiting for the children to arrive home from school.

Her snack of choice? Fresh chicken.

Most mischievous behavior? Sleeping in bed like a human—under the covers with her head on our pillows.

What fashion icon (dead or alive) does she channel? Katharine Hepburn. The hair, the poise, and the attitude.

How did you find each other? It was literally meant to be. We originally got Chicken for my mother when we thought her standard poodle was about to die, but that didn’t happen until much later, so Chicken became ours. A few years ago, we lost Chicken for three days, which was very traumatic. Slim was Chicken’s therapy pup. Slim came to save her and all of us.

What’s the most expensive thing your pets own? Me.

Their favorite pastime? Taking naps on our bed and car rides to Southampton.

What is one fashion trend your pets have pioneered? Hopefully none.

Their most cherished accessory? A Bode dog bed with hand-drawn illustrations. It was a gift from a friend.

Their favorite place? Their cave/bed. They run for it at night.

Their snack of choice? Chicken: chicken. Slim: salmon.

How did you find each other? It was an obsession. We were just waiting for the right time.

What nicknames do your pets respond to? Baby.

What’s the most expensive thing your pets own? An Hermès tent.

Their favorite pastime? Sleeping. Pugs are really lazy.

Their favorite place? Our house in the Cévennes in the south of France. They have a garden there where they can run free.

Most mischievous behavior? Jumping on the table to eat smoked salmon.

What fashion icon (dead or alive) do your pets channel? Marius channels Valentino.

What’s one fashion trend your pets have pioneered? They hate clothes. They are naturally trendy.

What nicknames does King respond to? Snuggie.

What’s the most expensive thing your pet owns? Me.

His most cherished accessory? His Hermès collar.

His snack of choice? Homemade sirloin beef jerky.

Most mischievous behavior? He puts his toys away every night—but he only does it when no one is watching. When guests come to visit, he carefully selects a few and brings them out to show off.

What fashion icon (dead or alive) does he channel? Richard Gere.

SHONO MARCH 8 – MAY 11, 2025

Sponsored by

Additional support from Jordan Schnitzer and the Harold & Arlene Schnitzer CARE Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, California Arts Council, the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia, and Amazon.

Media Partners: Artnet, ArtReview, C Magazine, Canvas Magazine, Cultured Magazine, frieze Magazine, Here Media, KGAY Palm Springs, GayDesertGuide and 103.1 MeTV FM, LocaliQ, part of The Desert Sun and Desert Magazine, Palm Springs Life Magazine, Terremoto, and Visit Greater Palm Springs.

desertx.org @_desertx

In her latest film, Magic Farm, artist Amalia Ulman takes Chloë Sevigny and Alex Wolff down to Argentina.

In Amalia Ulman’s new film, Magic Farm, a Vice -like crack team of documentary filmmakers—incarnated by the likes of Chloë Sevigny, Alex Wolff, and Ulman herself—land in rural Argentina to shoot a piece about a local musician, only to realize they’re in entirely the wrong country. In the midst of our protagonists’ frenzied reaction to the news, little thought is dedicated to the locale they’ve come to in their search for viral content: a community suffering the consequences of harmful crop spraying. So absorbed is the film crew in their city slicker woes that they fail to notice the turmoil around them—children are born with chemically-induced physical defects; agricultural planes zoom overhead, sending the locals running for cover; and coughing fits are shrugged off like spring allergies.

This trick, of backgrounding the foreground of a narrative, is one Ulman, an Argentine-Spanish video and performance artist, previously employed in her 2021 directorial debut, El Planeta . That film premiered at Sundance Film Festival, and last month, Magic Farm followed in

its footsteps. Ahead of its wide release later this year, the artist spoke to CULTURED about her approach to skewering our collective sense of moral detachment.

Did you think much about the parallel between making a film about a crew traveling to Argentina to shoot a movie, and doing the same thing yourself?

In a way, I enjoy making fun of myself. The crew and everyone involved in the story reflect elements of people I know and love. The critique of that style and hipsterism is also a critique of myself, which I think makes it more accessible and relatable.

Tell us about the cinematography of the film. There are a lot of scenes shot with unusual lenses, saturation, and other editing techniques.

I’m inspired by a lot of the beautiful things happening online and on TikTok, especially concerning editing. We even used CapCut for

some of the editing and transitions. The animal camera footage was inspired by a YouTube account I love, where someone in China attaches a camera to their cat.

Filmmaking is still a young art, even though the rules often feel rigid. The Internet today can feel like a dumpster, but there are beautiful things if you know where to look. I’m especially drawn to moments when people are unaware they’re making art—that’s when something magical happens.

What do you hope audiences take away from the film?

The film shows how superficial this hipster culture is when compared to the larger, looming problems that affect everyone. At some point, we’ll all have to face those deeper issues.

That’s the message of the film: There’s something more significant happening beneath the surface, and it’s something that connects us all.

norton.org

Features approximately 40 works, on loan from The Hispanic Society Museum & Library for the first time in over 100 years, exploring Sorolla’s lifelong connection to the sea.

Through April 13, 2025

Sorolla and the Sea was organized by The Hispanic Society Museum & Library with support from The Museum Box. Leading support for this exhibition at the Norton was provided by Judy and Leonard Lauder, the Fiddlehead Fund, and Lynne Wheat and Thomas Peterffy. Major support was provided by the George and Valerie Delacorte Endowment Fund, the Mr. and Mrs. Hamish Maxwell Exhibition Endowment, The Fanjul Family and Florida Crystals Corporation, and the KHR McNeely Family Fund.

Additional support was provided by Frank Yu, the Gioconda and Joseph King Endowment for Exhibitions, and Anonymous.

bocamuseum.org

This treasured exhibition features 57 priceless masterpieces from the 16th and 17th centuries by some of the greatest artists in history including El Greco, Diego Velasquez, Bartolome Esteban Murillo, and more.

Through March 30, 2025

Splendor and Passion: Baroque Spain and Its Empire was organized by The Hispanic Society of America, with support from The Museum Box. This exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

Sebastián López de Arteaga, Saint Michael Striking Down the Rebellious Angels [detail], 1650-1652, oil on copper. Courtesy of the Hispanic Society of America, New York.

SEE SO MUCH MORE THAN YOU CAME FOR

When you’re busy enjoying art at countless museums and galleries in The Palm Beaches, that white sand stroll may shift to tomorrow’s to-do list.

Filmmaker Cazzie David’s latest project, a romantic comedy run amok, examines the dark side of modern relationships.

After captivating audiences at SXSW last year, Cazzie David’s I Love You Forever is set for a limited theater release on Feb. 14—darkly comedic timing befitting a darkly comedic film that plumbs the murky depths of emotionally abusive relationships.

A writer, actor, and essayist, David has honed a distinctive voice that blends wit with poignant, often uncomfortable truths. Her 2020 essay collection, No One Asked for This, further cemented her status as a writer with a keen eye for the absurdities and nuances of modern life, relationships, and the messy contradictions of adulthood. Whether dissecting the pitfalls of romance or the chaos of quotidian interactions, David’s work is equal parts biting and reflective, with a refreshingly unflinching slant.

In an exclusive conversation with CULTURED, David reflects on the personal and creative forces behind I Love You Forever. She opens up about the challenges of creating multidimensional characters, navigating the fine line between humor and heartbreak, and why this film, in all its complexity, is her most intimate and daring project to date.

I experienced something in this vein and there wasn’t a lot to turn to in the aftermath. I wanted to make something that felt like a grounded, realistic portrayal of the feelings that swirl around emotional abuse. I talked to many people, and as I learned more, it became clear that it’s a kind of epidemic. I thought it was so crazy that there weren’t any movies that could help people to either feel seen or prevent themselves from getting into something like this.

At the same time, my writing partner and I wanted to write something that felt like a rom-com for our generation. It came together perfectly, because the textbook emotionally abusive relationship starts out feeling like a fairy tale or a once-in-a-lifetime love story.

Was there catharsis for you in making this film?

I think that will come when and if people can relate to this movie. I’m kind of waiting for that moment. It’s strange to have an experience and then direct that same experience on a set, but in the end, the film was an amalgamation of so many stories. We wanted there to be a glimpse of every manipulation tactic a person could have experienced in an emotionally abusive relationship—even a friendship—so that there’s something that almost anyone could relate to.

So many of the relationships in the film are heavily mediated by technology. That’s always something I’m wary of—it’s challenging to pull off a hyper-contemporary story in that way.

Hyper-contemporary movies, they’re such a bummer. Sometimes I’ll see a character in a show take a photo and be like, “La di da— posted!” No one has ever done that—come on! You take 300 photos, you craft a caption, and hours later you post it and delete it. I find those nuances to be really funny and touching, and they’re rarely portrayed accurately. But in the film, the phone has a major role—it becomes a leash linking Mackenzie to her boyfriend.

You seem interested in the idea of this film educating people. Many directors shy away from that.

I don’t want it just to feel informative—because that’s not a movie, it’s a PSA. But since I feel confident in the story—it has a lot of humor in it and it’s relatable to my generation—I’m happy if it also manages to teach you something. I think it has that educational potential because this is a subject that we have really inaccurate conversations about. If I had seen something like this when I was in high school, it could have helped.

“My writing partner and I wanted to write something that felt like a rom-com for our generation. It came together kind of perfectly, because the textbook emotionally abusive relationship starts out feeling like a fairy tale.”

—CAZZIE DAVID

By Rachel Corbett

The first thing I see in Robert Nava’s Brooklyn studio is four sets of bloody fangs. They appear in three different paintings of three different creatures: a shark, a dragon, and a roaring twoheaded tiger. Crudely rendered in acrylic and oil, these beasts can appear flat on a screen, but in person, they feel as if they could come to life at any moment.

The impulsive energy of his paintings is the product of Nava’s process. While he may deliberate on an idea for months and draw it over and over again in notebooks, he sometimes paints it in seconds. “It’ll be in muscle memory,” he explains.

Nava has been working to rein in his prolific tendencies, however, while awaiting his upcoming solo show at Pace in New York, which opens March 14. Surging demand for his work in recent years has pushed the artist’s auction prices as high as $715,000. But it’s often at precisely this stage of success that artists need to protect their careers the most. Nava has learned about the dangers of overexposure and is trying to practice patience. “But I’ll be honest,” he admits, “I feel like a Ferrari that only is allowed to go 40 miles an hour.”

“I FEEL LIKE A FERRARI THAT ONLY IS ALLOWED TO GO 40 MILES AN HOUR.”

Nava’s critics, and there are plenty, tend to see his paintings as a kind of adolescent effrontery, perhaps an intellectual insult and, taking into account his prices, an exorbitant gimmick. But while there’s an undeniably juvenile quality to Nava’s work, he speaks more in the guileless language of a child than that of a cynical teen. The satisfyingly swift execution of a painting, for example, is like “a flawless victory in Mortal Kombat.” Crits at Yale, where he earned his MFA, were like “gladiator matches.” And ultimately, he learned to fight with a “sword” in the art world, he says, like the young Spartan in the action movie 300.

While Nava bides his time until he can exhibit his next body of work, he has co-curated a show at Pace Los Angeles titled “The Monster,” on view through March 22, featuring artists he admires, including Huma Bhabha, Thomas Houseago, and Paul McCarthy. And he’s been playing a lot of Magic: The Gathering, where, he says, “an invitation to the imagination opens up.”

BY GIULIANA BRIDA

Arpita Singh’s canvases are untethered by anatomy. Figures stretch and shrink. Objects float, defying gravity. But the artist doesn’t see her work as belonging to the realm of fiction or fantasy. “For me it’s very real,” Singh declared in conversation with Serpentine Galleries Artistic Director Hans Ulrich Obrist. “In dreams, mostly things aren’t under your control. Here, things are … There is a law, but that law is according to me.”

For over six decades, Singh has remade the world in her vision—men in black suits multiply, sensuality flourishes, and the humble “dot and line” receive seven years of creative study.

This spring, Singh’s career will be the subject of “Remembering,” the artist’s first solo show outside her native India, opening at London’s Serpentine North Gallery on March 20.

Born in what is now the state of West Bengal in 1937, Singh didn’t foresee a life in the arts until her school principal nudged her along. “I didn’t know there was … a field called ‘art,’” she told Obrist. It wasn’t until her first year of college at Delhi Polytechnic that she visited an art museum, the National Gallery of Modern Art. Since emerging in the arts scene in the late 1960s, Singh has built a body of work that melds abstraction with traditional Indian court

painting. The latter has a long history of blending the mythological and the quotidian, an enduring aspect of Singh’s work.

“Remembering” spans large-scale oil paintings, intricate watercolors, and ink drawings. Her freedom of thought permeates the expansive show, in which recurring motifs— planes, fruits, and fragmented figures—evoke what Nietzsche described as the “eternal return,” a cyclical rhythm that feels at once personal and generationally universal. “I believe, then I doubt. I believe, and I doubt again,” Singh has said. “That’s the whole process of my work.”

POLAROIDS BY HANNAH TACHER

By John Vincler

Pippa Garner, who died at the age of 82 in Los Angeles on Dec. 30, 2024, was an artist whose work made its beholders more free.

Behind the prankishness of her absurd, tricked-out objects—cars with their bodies flipped, so they would appear to drive backwards; high-heeled roller-skates; a men’s “half-suit” that exposed the midriff—there was a yearning for transformation. The whole of her life was a revolutionary artwork.

Garner, raised as a boy in the Midwest, was restless and depressed in school, where she was often told what not to do rather than encouraged to explore her interests. Her parents saw her love of art and drawing and

encouraged her to study automotive design, so she headed off to Los Angeles’s ArtCenter College of Design. (Garner would be kicked out—for making early versions of her satirical objects that lampooned consumer culture and the fantasy of “easy living.”)

She was an art-world outsider for most of her career, choosing to present her work in popular magazines or on late-night talk shows where hundreds of thousands might see it rather than in industry-vetted venues. She sensed that she would never be taken seriously as an artist without showing regularly in galleries—though she would do just that, eventually. She had a floor to herself in last year’s Whitney Biennial, and at the time of her death, her work was on view in a pair of linked exhibitions—at Stars in Los Angeles and Matthew Brown in New York.

Garner may be remembered most, in this political moment, as a path-breaking transgender artist. In the early ’80s, she paid a sex worker on Hollywood Boulevard to tell her about her transition, and Garner learned how to acquire black-market estrogen before pursuing genderaffirming surgeries. She often compared the body to an appliance, a toy, or a car—why not tinker with it too?

She died a little more than a week before the recent fires started in Los Angeles, the city she called home. Garner liked it because it felt like she did, “a little off,” not growing the way anyone planned. She was never comfortable with the idea of a retrospective because she wanted to do new things. But we deserve one now. Garner still has much to teach us about the freedom of transformation.

Feb. 24–July 6, 2025

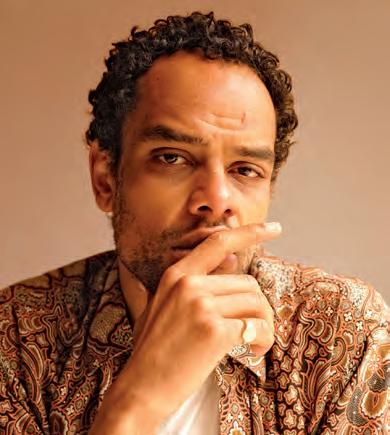

THE NEW YORK–BASED ARTIST WAS SELECTED BY THIS YEAR’S PANEL OF JURISTS, COMPOSED OF LEGACY RUSSELL, RUBA KATRIB, AND KELLY TAXTER, TO WIN THE PRIZE FROM CULTURED AND MZ WALLACE.

Malcolm Peacock, a New York–based artist and athlete whose participatory work captivates audiences with piercing questions about intimacy, power, and loss, is the winner of the 2024 Young Artist Prize. Presented this year by CULTURED in partnership with MZ Wallace, the award offers $30,000 to a promising talent chosen from the magazine’s ninth annual Young Artists list.

“Through his multidisciplinary practice,

Malcolm’s powerful work proposes different ways of being in the world,” say Monica Zwirner and Lucy Wallace Eustice, MZ Wallace’s cofounders and codesigners. “He explores feelings of connections, to others and to ourselves, which makes the work both timely and universal. We are honored to play a part in supporting his artistic journey.”

Peacock was selected from the 30 artists on this year’s list by a distinguished jury

composed of Legacy Russell, executive director and chief curator of the Kitchen; Ruba Katrib, chief curator and director of curatorial affairs at MoMA PS1; and Kelly Taxter, deputy director of Artists Space.

“Malcolm’s work—in performance, sculpture, installation, writing, drawing—resists spectacle or sensationalism,” says Taxter, “and reaffirms the quiet power of individuals and communities to create the realities they need and deserve.”

“I WOULD RATHER HAVE A DIFFERENT CAREER BEFORE I SETTLE.”

MALCOLM PEACOCK

A hulking tree trunk spent the winter in one of MoMA PS1’s galleries this year. Measuring eight feet tall and assembled out of foam, cement, wood, and over 3,000 braids of synthetic hair, the sculpted relic was punctuated by a sonic tapestry of recordings that immerse visitors in moments of “Black convening.” The installation was not a static sanctuary, but a continually evolving act of presence.

When we met ahead of its unveiling, the artist behind the work, Malcolm Peacock, was already calling Five of them were hers and she carved shelters with windows into the backs of their skulls a milestone piece. The Raleigh, North Carolina–born, Baltimore-raised artist began work on the installation last January, a few months into a Studio Museum in Harlem residency that the PS1 showing concluded, pulling from research on redwoods he’d initiated after two summers spent in the Pacific Northwest. It is the only artwork he made in 2024.

Peacock is well aware that most young artists would be warned against dedicating close to a year to a single piece. “Not when you’re 30,”

he tells me with a laugh. But that one-track mindset has paid off thus far. “I have made six things in the last five or six years for various group exhibitions, and endurance has played an essential role in bringing these works to life,” Peacock reasons. The Studio Museum residency is just the latest in a round of institutional attention—including the 58th Carnegie International Fine Prize and a duo show with Shala Miller at Artists Space—that the interdisciplinary artist has garnered since earning his MFA at Rutgers University in 2019.

When asked where he thinks the next five years will take him, Peacock doesn’t blink an eye. “I just want to keep moving like this,” he says. “I would rather have a different career before I settle.” Refusing to settle, or to settle down—that daily dissent grounds Peacock’s practice. Whether he’s braiding, leading breathing exercises, or running while reciting an inner monologue, the artist is interested in making the experience of effort—and the (often invisible) barriers to accessing rest and recreation—manifest.

One thing is certain: Working at the monumental scale the Studio Museum

residency offered has inspired Peacock to meditate on the opportunities that making a major—in all senses of the term—work can afford an artist.

His next project will see him apply that macroscopic lens to a historical event: the first transcontinental American ultramarathon, where 199 men attempted to cross the country by foot in 1928. The artist will focus on the experiences of the five Black men who made the journey and their reverberations a century later. “I’ll never forget how, in Nicole Miller’s To the Stars, Alonzo King says to his dance students, ‘The whole universe … wants to expand,’” Peacock notes, referring to the Los Angeles-based artist’s 2019 film. “Since completing Five of them were hers…, I’ve become excited about making more works that can speak to the notion of stretching what I know or believe I know to be possible. The word ‘possible’ can often be a barrier that is placed upon people. If there is a desire for agency in our lives, I think we must interrogate that word, its meaning, and its use.”

ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

FOR THIS YEAR’S EDITION OF FRIEZE PROJECTS, EIGHT ANGELENO ARTISTS HOLD A MIRROR TO THE CITY THAT INSPIRES THEIR WORK.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY ILONA SZWARC

In keeping with Frieze Los Angeles’s deep fascination with its sprawling metropolitan host, this year’s edition of Frieze Projects offers an insider’s glimpse at the city’s cultural topography. Curated by Art Production Fund, “Inside Out” presents a series of installations by artists with deep roots in the city, diving into the microcultures and ecosystems that make LA so confounding, so romantic, so fraught. “‘Inside Out’ reflects on place—how we navigate the spaces where we land,” says Art Production Fund Executive Director Casey Fremont.

“Emerging from these works, often with a touch of whimsy, are reflections on movement, migration, and physical and social mobility,” adds Christine Messineo, Frieze’s director of Americas. Indeed, the program’s participating artists—six of whom share the origin stories behind their Frieze Projects contributions here—represent a wide range of Angeleno attachments. Their respective installations offer a touching homage to a city that, even in the wake of ecological disaster, is forever blossoming.

Ozzie Juarez, Pásale! Pásale! Todo Barato!, 2025

“While studying art at Santa Monica College, I made the long trek [from South Central] each day—about five hours in total—on public transportation. As I traveled, I noticed the gradual transformation of the cityscapes around me—with each passing neighborhood, the environment shifted. I found inspiration in the contrast between these two worlds. For this year’s Frieze Projects, I wanted to bridge these contrasting realities.”

Greg Ito,

A Time to Blossom, 2025

“My Frieze Project began with an exploration of a recurring symbol in my work—a burning candle. Amidst the wildfires affecting our city, it evolved naturally into a new sculpture: a golden clock with flowers sprouting from its top, titled A Time to Blossom. This piece symbolizes hope, a reflection on time’s capacity to heal, and a testament to the

resilience and enduring spirit I believe thrives in Los Angeles.”

Jackie Amézquita, Trazos de energia entre trayectorias fugaces (strokes of energy between impermanent traces), 2025

“In researching the history of Santa Monica, I found intriguing stories … [including] narratives around the Kuruvungna Springs, now the site of University High School in West Los Angeles. The Tongva tribe consider these springs, flowing at 22,000 gallons per day, sacred. They continue to hold ceremonies there. This information led me to reflect on maps [for my Frieze Projects contribution], and how natives and non-natives have navigated and reshaped the land throughout history.”

Claire Chambless, Player, Non-Player, 2025

“Player, Non-Player questions the salvific nature of art acquisition by drawing attention to the symbolic nature of purchasing. The work follows a foraging or gift-giving model rather than monetary exchange—everyone has an equal chance to find and acquire a piece. If they do, they will get a handmade talisman. In light of the fires that have caused such inconceivable devastation in Los Angeles, giving and sharing things that can hold memory feels more important than ever.”

Madeline Hollander, Day Flight, 2025

“Day Flight originated from my experience learning to fly as a teenager. The work offers a guide to your body in relation to the plane, the wind, and LA’s recently ravaged landscape. While the panoramic views of the Pacific Palisades and Malibu are undoubtedly devastating, their harsh transformation is a reminder of the ephemerality and fragility of our environment and the acute reality of living with climate crises.”

Lita Albuquerque, Turbulence, 2025

“This [work] begins with the ruins below the convent I grew up in [in Carthage, Tunisia]. It continues decades later; when I started living in Malibu, I would collect rocks on Highway 1 and bring them to my studio in Venice, where I’d pour powder pigment on them to reflect what I felt was within them. If the Earth itself could speak, what would it say? Turbulence comes as a response to the fire storm that has devastated Los Angeles and the art community. The title embodies what we are feeling and what the Earth itself is expressing.”

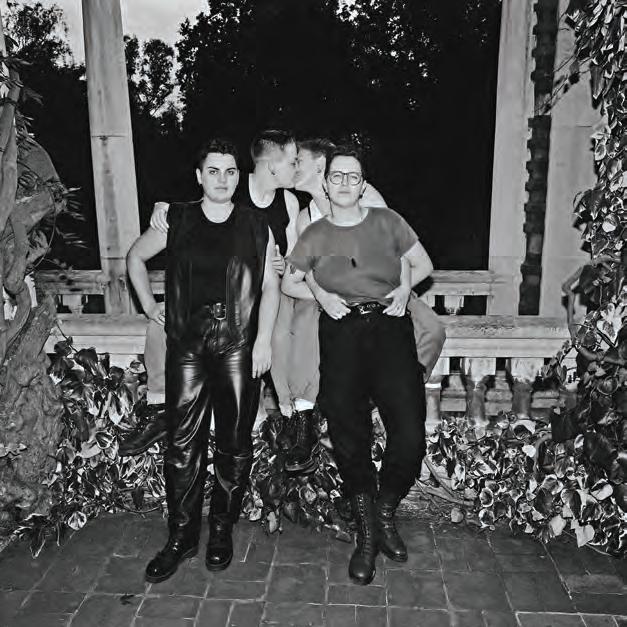

IN MAY 1988, SECTION 28, AN EDICT PROHIBITING LOCAL AUTHORITIES FROM “PROMOT[ING] HOMOSEXUALITY,” WAS PASSED BY THE BRITISH GOVERNMENT. THAT SAME YEAR, DEL LAGRACE VOLCANO BROUGHT FOUR FRIENDS TO LONDON’S HAMPSTEAD HEATH—A WELL-KNOWN CRUISING GROUND—FOR A PHOTO SHOOT. VOLCANO, THE AUTHOR OF SOME OF THE QUEER CANON’S MOST ICONIC IMAGES, HAD FALLEN IN WITH THE CHAIN REACTION CROWD—THE COLLECTIVE BEHIND THE WORLD’S FIRST LESBIAN BDSM CLUB. “IT WAS A SAFE SPACE FOR ROLE-PLAYING, LEATHER DYKES, MOTORCYCLE DYKES, MISFITS, AND TRANS WOMEN,” THEY REMEMBER OVER ZOOM. “THERE WAS A SORT OF GANG FEELING.”

AT THE HEATH, VOLCANO INVITED THEIR CO-CONSPIRATORS— JAYNE, ZED, KIM, AND SERENA—TO POSE, PLAYFULLY APPROPRIATING THE PROMISCUITY BETTER ASSOCIATED WITH GAY MALE CULTURE. THE RESULTING SERIES IS AN ODE TO THE PERSISTENCE OF PLEASURE AND POWER OF KINSHIP. THIRTY-SEVEN YEARS LATER, THE IMAGES ARE BEING GIVEN A NEW LIFE WITH QUEER DYKE CRUISING, PUBLISHED BY CULT BOOKSTORE AND PRESS CLIMAX. TO MARK THE OCCASION, VOLCANO SHARES A SNAPSHOT FROM THEIR ROMP IN THE PARK.

—ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

“[This series] was inspired by gay male sex culture. So you’ve got [these] big butch dykes ‘cruising’ in [Hampstead Heath], gay men’s territory, performing these scenarios in a kind of staged way. This group here—they were mixing it up. They were going to a lot of sex parties together, so it was real. It wasn’t like they didn’t know each other. But I [always] create a space where people can express themselves. I don’t give them a script—it’s more like, ‘Play yourself’…

I’ve always been interested in photographing what is unpredictable or random. When it comes together, it’s just magic. I’m interested in multiplicity, unpredictability, and precarity. A little danger, a little risk. But I want people to understand that I’m not making this work just for my family photo album. I’m making it for our album—for us. Photography is not just a job for me; it’s a calling, a destiny.”

AS COMEDIAN AIDY BRYANT PREPARES FOR HER SECOND RUN AS HOST OF THE 40TH ANNUAL FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS, SHE CALLS UP FELLOW TWO-TIME HOST NICK KROLL FOR SOME LAST-MINUTE ADVICE.

“AIDY, MY INSTINCT IS THAT I MET YOU WHEN YOU GOT ON SNL. UNTIL YOU’RE ON SNL, YOU’RE INVISIBLE TO ME.” —NICK KROLL

At most awards shows, hosts have earned a reputation for being thinly veiled roast emcees. Cameras pan to A-listers hiding behind their co-stars or opera gloves, and all manner of jabs are fired off liberally. But the Film Independent Spirit Awards demand a different touch. The annual event has cemented itself over the past four decades as a highly anticipated and refreshingly light-hearted celebration of rising and indie filmmakers. That crowdpleasing reputation has drawn a roster of buzzy hosts, including two of Hollywood’s most affable celebrities: Aidy Bryant and Nick Kroll.

Bryant will return on Feb. 22 for her second run on the Spirit Awards stage, while Kroll has helmed the festivities twice himself—alongside his sometime comedy partner John Mulaney—in the late 2010s. Ahead of the show, Bryant and Kroll took a break between rehearsals at New York’s Hudson Theatre (where the pair were among the cast of the live comedy reading series All In: All About Love) for a run-through of her forthcoming hosting appearance, where she’ll celebrate the 40th Anniversary of the Spirit Awards and entertain the creators and fans of 2024 favorites Anora, Sing Sing, The Substance, and more.

Nick Kroll: We have a lot in common—and not just hosting the Spirit Awards. We also share a love of big cups.

Aidy Bryant: I love drinking from my big cup.

Kroll: Mine is an Erewhon mason jar. No big deal. I am in constant fear of being dehydrated, so I drink out of these. Anytime I drink out of a regular glass, I’m embarrassed—like for the cup.

Bryant: Agree. If it’s not big, I don’t rock it. I also want to say I’ve never been to Erewhon.

Kroll: It is so funny how expensive it is. And we can find that funny because we’re America’s two biggest celebrities, and because we get paid the big bucks to host things like the Spirit Awards.

Bryant: How and when did we first meet? I don’t remember. Feels like I’ve just known you for a long time now, maybe 10 years.

Kroll: My instinct is that I met you when you got on SNL. Until you’re on SNL, you’re invisible to me.

Bryant: And since I’ve left, I’ve been invisible to you. I’m so grateful for this time together.

Kroll: Until you hosted the [Spirit Awards] last year. Then you became a central voice on Human Resources, my animated show.

Bryant: It was the honor of my life to be your employee.

Kroll: Thank you, as it was written in the contract for you to say so in any future engagements.

Bryant: You hosted the Spirit Awards with John [Mulaney] both times, right?

Kroll: Yeah, and he was later offered the chance to host the Oscars without me. I think that’s for the best.

Bryant: I wouldn’t want to do those. Would you?

Kroll: That was the fun of doing the Spirit Awards. I felt quite free, like we could kind of do whatever we wanted. Everyone is happy to be there; it’s a little more relaxed. The first year we hosted was 2017. The second time was in 2018, right after #MeToo.

Bryant: They said, “We need to put a voice to this. Who should host? Nick and John.”

Kroll: “Let’s get those two white guys back up there.” Both experiences were equally fun, but it felt more complicated the second year. How do you feel going into the second year?

Bryant: I had so much fun the first time that I guess that’s my only goal this time: to have fun again. The reputation of an award show host is that you gotta come in there and blow those fuckers away with your bazooka of hot takes and satirical burns. But I’m really thrilled to be there. I also really believe in the ethos of Film Independent.

Kroll: In that room, you really do feel a shared value system. Our job is to make lots of jokes but also, in this particular case, you’re not like, “I’m gonna fucking shred these people and their movies.” It’s such a big day for people—these are independent filmmakers who have spent years toiling to get their very niche films in front of people. Diminishing what they’ve done doesn’t sound like much fun.

Bryant: If you’re hosting the Oscars and the biggest celebrities in the world are there, you want to take them down a peg. I know one of the movies this year was shot in 11 days in the woods for like $10. I don’t need to be swinging a bat at that.

Kroll: We hosted the year that Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri was nominated. Frances McDormand was there, who absolutely rocks. Later at the after-party I saw her trying to sneak out with a jacket over her head. Normally, I’d think, Oh my God, that’s Frances McDormand, just leave her be, but since I’d been hosting, I felt a little entitled, like I was part of the scene.

I was like, “Franny! Franny!” She stopped, looked at me, and said, “Okay, I will talk to you.” I replied, “Great. I need you to know that you look so much like my therapist.”

Bryant: Do you remember how you prepared to host with John?

Kroll: We ran it a lot. I’m blown away and mystified by people who host these things and don’t run it. For you at SNL or for me with stand-up, you’re like, “I need to hear from an audience what’s working and what’s not working.”

Bryant: I can’t even fathom just looking at a piece of paper and then being like, “Great, this is what I will do.” Even if I’m selling myself out by testing material, it’s worth it to me. I just want them to have a good time. I’ll show hole if I have to.

Kroll: Do you plan to show hole at the show?

Brant: I’m thinking about it for sure—toying with the idea, toying with which hole.

Kroll: It’s a terrible turn we’ve taken here.

Bryant: Do you have constructive feedback for me based on my last performance?

Kroll: Picture the audience absolutely naked. But no, honestly I loved being in that room with people who spent a lot of their life force to make something that they really believe in. It’s a big day, and you just want to show them a good time. Plus, you can hit the Santa Monica boardwalk immediately afterwards.

Bryant: As soon as I finished hosting the awards last year, I hopped on my skateboard, got a corn dog, and just started cruising the beach for guys. Do you know how to skateboard?

Kroll: I do not. Do you?

Bryant: No.

Kroll: Fuck, next year.

“AS SOON AS I FINISHED HOSTING THE AWARDS LAST YEAR, I HOPPED ON MY SKATEBOARD, GOT A CORN DOG, AND JUST STARTED CRUISING THE BEACH FOR GUYS.” —AIDY BRYANT

“IT DOES, IN FACT, FEEL LIKE MY MOMENT.”

PHOTOGRAPHY BY BRANDON HICKS

STYLING BY MEAGHAN O’CONNOR

By Rachel Cargle

While the world catches up to the brilliance of Natasha Rothwell, she’s been “10 toes down” in developing characters and taking on roles that offer her, and her audience, a 360-degree view of what it means to be “whole” onscreen.

Since 2014, we’ve caught glimpses of Rothwell’s wit and wisdom as a writer on SNL and as Issa Rae’s hilarious friend Kelli on HBO’s Insecure. In recent years, her star has reached new heights with roles like Belinda, the loving and striving spa manager on the hit Max show The White Lotus, and Mel, a broke JFK airport worker who sets out on a journey of self-discovery in the Hulu series How to Die Alone, which Rothwell created.

“It feels like an expansion that I’m now allowing others to witness,” she shares over a recent afternoon Zoom. She apologizes as her black goldendoodle skitters by, leaning down to ruffle the puppy’s ears. Rothwell’s soft curls and deep brown skin glow on my laptop screen. She exudes the ease and intention of someone who has found their footing. “I’ve been feeling that growth for some time, and I think it does, in fact, feel like my moment,” she reasons.

Rothwell smiles as she speaks, but impostor syndrome seems to creep up on her midsentence. “I say that with a lot of trepidation because, despite my vocation, I can be pretty shy,” she admits. “It’s ultimately thrilling to be in this place where I’m garnering so much respect in my industry and having so many

more people exposed to my work. But taking up space as a fat, Black woman; as a creator; as someone who has, for her whole life, desperately wanted to be seen—that’s equally terrifying.”

Rothwell hasn’t let those feelings overwhelm her. As she developed How to Die Alone (a seven-year dream come to life), she let her full self show up—even the “unhealed parts,” as she puts it. In one scene in the season finale, her character strips down to her bra and panties on a public beach—a level of public exposure Rothwell has never faced in her personal life. Doing it on television added new layers of vulnerability, but she pushed through, feeling powerful and new when she emerged. “It’s painstaking,” she says. “You can only be as honest as you’ve been with yourself.”

She finds that her Emmy-nominated role as Belinda on The White Lotus is another opportunity to be a more expansive version of herself. As she heads into season three alongside a star-studded cast that includes Parker Posey and Carrie Coon, Rothwell challenges what audiences might expect from her screen presence. “When you walk through the world as a Black, plus-size woman, there are a lot of expectations people have based off of their preconceived notions of film and television,” she explains. “The mischievous side of me really delights in subverting those expectations.”

Rothwell was born in Wichita, Kansas, but spent her childhood on military bases around the world. Her father, who was in the Air Force,

and her mother, who worked in health care, fostered a sense of pride in whatever work she chose to pursue. Ultimately, it was theater, then the comedy circuit, that beckoned Rothwell. But it was never just about the stage. Her occupation as an actor has always been accompanied by a role as an advocate for the issues she feels are worth the fight: mental health care, voting, and media representation.

Those values pulled Rothwell into developing a production company of her own, Big Hattie Productions, named after the late Wichita-born actor Hattie McDaniel, who is best known for her Academy Award–winning role as Mammy in Gone with the Wind. Rothwell stumbled upon the film as a teenager working at Blockbuster. For the first time, she saw someone onscreen who looked like her.

“I saw the deference the other actors gave to her in each scene, and how she demanded the attention of every person that she engaged with in that film, and I saw very clearly why she won the Academy Award,” Rothwell says. “My production company is about subverting expectations, demanding that attention, and centering the voices that are often marginalized in the industry.”

When I ask Natasha where her inspiration is taking her next, she carefully avoids specifics but makes one thing clear: “I’m very picky about what I do; I’m very deliberate about the projects that I take on. [But] each one channels the spirit of Hattie McDaniel—the spirit of being so good they can’t ignore you.”

“WHEN

YOU WALK THROUGH THE WORLD AS A BLACK, PLUS-SIZE WOMAN, THERE ARE A LOT OF EXPECTATIONS PEOPLE HAVE BASED OFF OF THEIR PRECONCEIVED NOTIONS OF FILM AND TELEVISION.”

FOR THE NEWEST EDITION OF ITS ARTIST SERIES, MOVADO ENLISTS DERRICK ADAMS.

By Sophie Lee

The watch was uniform in color—black with a silver case, hands, and single dot topping the face, as if the sun had just reached high noon. When the Movado Museum Classic became the first dial to enter the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in 1960, Nathan George Horwitt’s design entered the canon of midcentury minimalism. Sixty-five years later, artist Derrick Adams is reimagining the timepiece for our era.

His is the latest in the Swiss watchmaker’s Artist Series. In the late ’80s, Movado inaugurated the project with the patron saint of Pop art, Andy Warhol, who splashed a black-and-white photo of New York across five interlinking watch faces. Collaborations with the likes of Proenza Schouler, Kenny Scharf, and James Rosenquist followed, each epitomizing the artistic tides of the time.

For this year’s edition, Adams has invited a suite

of his signature Cubist-inspired portraits onto five sleek 40-millimeter watches, washing or dotting the straps in harmonizing swaths of high-octane hues, as well as two wall clocks and a collector’s set. “ With his employment of distinct geometric shapes, bold prismatic colors, and fantasticaly intricate patterns, Derrick creates a visual language which is dynamic and iconographic,” says Studio Museum in Harlem Director Thelma Golden, a regular collaborator of Adams’s who first encountered his work when she included him in the institution’s 2003 show “Veni Vidi Video.” “It only makes sense that his artwork be displayed on a watch that can live up to these same qualities.”

Indeed, Adams’s depictions of Black joy and leisure have disrupted art-historical iconography for over two decades. Since his early inclusion in the Studio Museum group show, the Baltimore native’s work has traveled around the world, injecting the artist’s signature whimsy into spaces as disparate as a Long Island Rail Road station

in Brooklyn and the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris.

For Movado, a piece from one of Adams’s most well-known series, “Floaters,” capturing a day spent in the water, gets miniaturized, transporting wearers into the balmy insouciance of summer with one flip of the hand. Another featured work, Fashion Fair, dives further into abstraction, its blocks of color extending into the watch’s strap like a chromatic timeline. Each model is finished with a bespoke stainless steel caseback, leather strap, and presentation box evoking Adams’s ebullient universe. Across the watches, clocks, and collector’s set, only 125 numbered editions of each have been produced.

For Golden, the weaving of Adams’s visual language into the accessory space is an investment in more ways than one. “To have his work depicted on these watch faces,” she concludes, “is to be able to carry a piece of art history with you every day.”

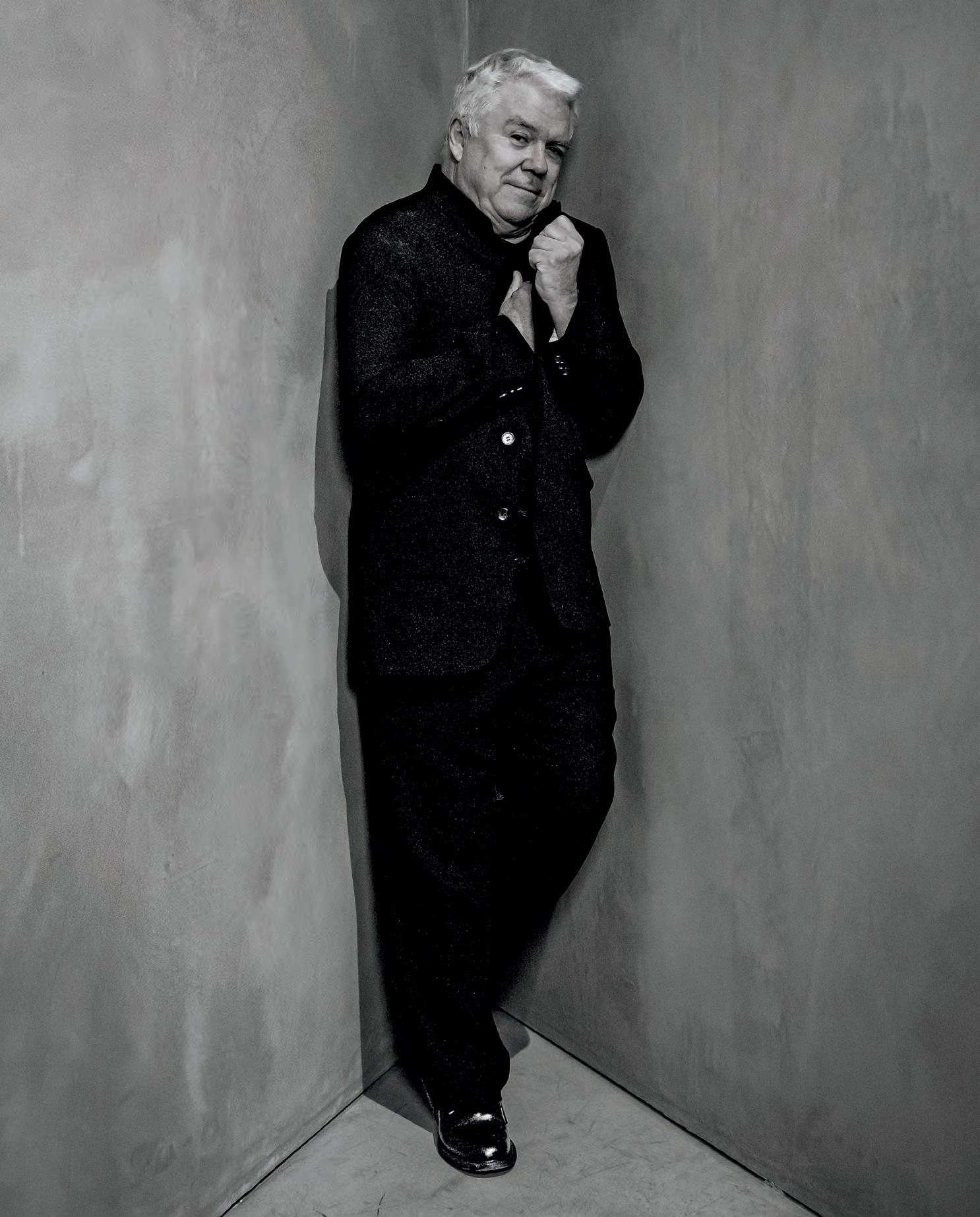

CULTURED’S CO-CHIEF ART CRITIC TALKS TO THE COLLECTOR AND GALLERIST ABOUT BUYING A VAN GOGH AND STARTING A MUSEUM ON MARS.

By John Vincler

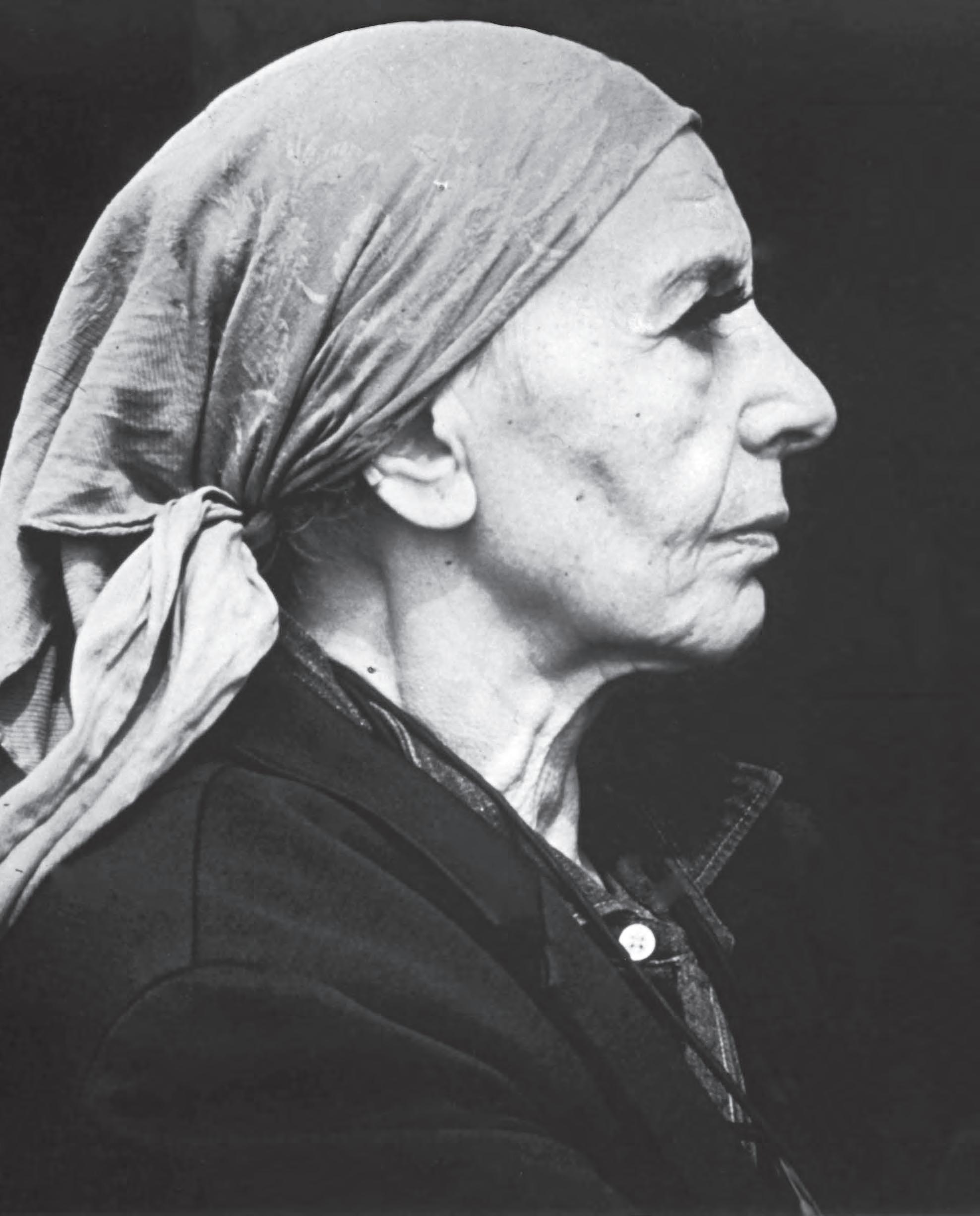

I thought Hong Gyu Shin was one of the most interesting figures in the New York art scene even before I was sitting at his dining table, looking at his newly acquired Van Gogh. The small canvas, Head of a Peasant, painted in 1885, depicts a woman in profile with her hair gathered up into a dark hat. In Shin’s crowded hang, it shares wall space with a wildly varied range of artists, including the 1980s street artist Richard Hambleton, a peer of Basquiat and Haring whose two “Shadowman” figures loom like apparitions overhead.

Anyone with deep enough pockets can buy a Van Gogh. But few Van Goghs go on to join such eclectic company. Shin, the South Korean–born proprietor of Shin Gallery on New York’s Lower East Side, snapped this one up last May at Sotheby’s for about half its low estimate of $1.5 million.

His floor-to-ceiling arrangement has the Van Gogh nuzzled below a larger Balthus of a topless redhead from 1947. They hang beside a Sam Francis painting from 1950 that looks as if a late Rothko ate a Joan Mitchell, with a gesturally painted yellow arch peeking out near the bottom of its darkly overpainted expanse. I snap a photo of a graphite drawing by Eugène Delacroix in a gilt frame near the ceiling to send to a friend who admires his journals. A sculpture of hand-carved oak and colored resin by Marisol, Portrait of Willem de Kooning, 1980, sits sentry before it all, incorporating cast copies of her subject’s hands. Shin’s apartment is like an eccentric—and packed—party of artists spanning across centuries.

“I RECENTLY REALIZED THAT HAVING A LOT OF MONEY IN MY BANK ACCOUNT WOULDN’T MAKE ME FEEL MORE SECURE.”

With continued buzz about a downturn in the market and galleries noticeably retreating into conservatism, I wanted to check in with Shin, who, after starting his gallery in 2013 between his sophomore and junior years of college, has never followed the crowd or faded into the background. (That same year, he bid $100 million on a then-record-setting Francis Bacon triptych at Christie’s. Although he didn’t win it, Shin immediately drew the attention of art-market machers.) In the gallery’s second year, he staged a show of photographs by the Viennese Actionist Rudolf Schwarzkogler and the Japanese photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, known for his erotic themes. The gallery was made to resemble a massage parlor, garnering coverage in the New York Post with the headline, “Horny guys seeking ‘happy ending’ fooled by fake massage parlor.”

Ten years later, Shin’s project has matured as it remains at the same (now expanded) location, with the main gallery on the first floor and a

project space, Shin Haus, which specializes in emerging artists, in the basement. I ask him if it has gotten any easier running a gallery. In fact, the stakes have only gotten higher. “At the start, if I made $5,000 in a month it seemed like a lot of money,” he says. Now, if that were all he made over several months, he would have to close.

When I inquire about his plans for the future, his answer catches me off guard. “My ultimate goal is opening a museum on Mars,” he says. I awkwardly shuffle my notes and write “Mars?” before asking, tentatively, if he is thinking about Mars pre- or post-human occupancy? He delivers his answer, “pre-,” in a manner that is at once charming, hilarious, and dead serious, with an implied obviously

I first met Shin when fact-checking my New York Times review of his 10-year anniversary show, “Amalgamation,” in 2022. Even then, despite his soft-spoken manner and clean-cut collegiate mien, he struck me as having the attitude of an artist rather than a gallerist or collector. He notes that he generally lives a humble existence, taking the train or riding Citi Bikes to traverse the city. He’s wearing a favorite cardigan he’s had since he was in high school. He spends much of his time in the gallery or surrounded by his collection at

home, researching an acquisition or planning a future show. He’s already achieved two of his personal dreams: to own a Picasso and, now, a Van Gogh. He acquired the Picasso, Femme endormie, an oil on canvas from 1933 barely larger than a postcard, during the pandemic.

He kept it by his bedside “so I could look at it at the start of the day and at night before I went to bed,” he tells me, adding with a laugh, “We basically slept together.” Then there was an opportunity to sell at a great price.

I assume that’s how he bought the Van Gogh, but he corrects me. “My bank account is like, total Buddhism,” he says. If a lot of money comes in, it quickly goes out. “I recently realized that having a lot of money in my bank account wouldn’t make me feel more secure.” Instead, he prioritizes having money only insofar as it helps him realize his projects.

Does Shin think of himself as an artist? “I express my artistic desires and ideas through curation, so each exhibition is, I think, my artwork,” he says. He sees himself as a storyteller who puts artists first: “They’re the ones who change the world.”

“I EXPRESS MY ARTISTIC DESIRES AND IDEAS THROUGH CURATION, SO EACH EXHIBITION IS, I THINK, MY ARTWORK.”

ONE WRITER DISSECTS THE OUTER GARMENT’S UNDYING GLAMOUR.

By Liana Satenstein

Whenever I wear my Burberry trench, I am showered with compliments. People love the poshness of it. The trench is the sleek antidote to any hangover or sartorial mess. An instant upper. A mainlining of heritage. After all, you can throw the roomy piece over anything. I don it over whatever slapdash slop I wear, and promptly transform into some clay-bird-shooting dame happily marooned in the Cotswolds. I wear my dark green trench in two different ways: undone and open in a deliciously louche, just-railed 9½ Weeks style, or knotted at the waist to give the body a tony feminine curve, a tie-it-together elevation.

Thomas Burberry, who founded the house in 1856, knew his way around weatherproof pieces. He made outerwear out of gabardine, a waterproof fabric woven so tightly that nary a droplet can permeate. Sure, waterproof pieces existed before, but the beauty of Burberry’s gabardine was that it allowed ventilation. He patented it in 1888.

Explorers and adventurers wore Burberry’s outerwear while floating across countries in hot air balloons or traversing Antarctica. Later, Burberry transformed his pieces into something not only waterproof but also warproof: He created coats for soldiers in WWI, complete with epaulets and D-rings and extra-large pockets for maps. This, as the name implies, is considered the origin of the classic Burberry trench coat, born in the literal trenches.

A 1923 advertisement makes the Burberry trench—the company was then named Burberrys—seem like the Holy Grail of outerwear. “When rain, drizzle or mist make an ordinary Overcoat feel like a wet blanket,” the tagline read.

But the trench coat is as fashionable as it is useful. Browsing through Vogues of yesteryear, I spotted a post-date-night Christy Turlington in an Arthur Elgort–shot editorial from 1998. In the image, Turlington saunters up the steps at Via Rodeo in Beverly Hills wearing a skimpy cream shift dress with a Burberry trench thrown over her shoulders like an engulfing shawl, her arms peeking out from under while she totes a dainty lady bag. Another image from 1986, in a tiny margin insert, shows a model in slacks and a trench with an umbrella under her arm and the caption “best weather/travel insurance.”

In an era of fast fashion and ever-churning trends, this coat is not an obnoxious It bag that will fade from the sartorial conversation next season, nor is it a pair of pants we risk growing out of. The Burberry trench is a perpetual classic because it is indispensable.

Today, it’s propagated into many silhouettes. Some are snappy and short, skimming the top of the hips. Of course, there is the standard, fail-safe ankle length. The color scheme is a muted rainbow of neutrals: verdant, rich countryside green; blue so deep it’s almost black; and beloved warm honey. I prefer the nontraditional dark green version, officially titled the “Long Cotton Blend Trench Coat” in “Military.” I leave the epaulets undone and the collar flipped up for a peekaboo of that prim house-check lining.

Pro tip: No matter how you wear it, never buckle the belt through the loops, but tie it so the straps delightfully fall at the sides of the body. Whether you’re model Kate Moss or explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, that’s the Burberry-approved look.

BY ELISSA SUH

THE DANISH-IRANIAN DIRECTOR IS NO STRANGER TO CHALLENGING SUBJECTS. BUT THE APPRENTICE TESTED HIS RESOLVE.

“There’s no upside to making a film like this,” Ali Abbasi says of his latest feature, The Apprentice, a biopic chronicling Donald Trump’s rise to prominence under the mentorship of Roy Cohn in the 1970s and ’80s. “If I were an American director, I might have passed [on it], too.”

Initially, the script, written by the journalist Gabriel Sherman, made the rounds among highprofile filmmakers like Clint Eastwood and Paul Thomas Anderson. Both declined, deeming it a business risk. Without any direct ties to the U.S., the Danish-Iranian Abbasi was a fitting choice. He first became aware of Trump in June 2015, on the day the infamous real-estate mogul descended the escalator of his Fifth Avenue skyscraper to announce his bid for president.