THE EVOLUTION OF HARI NEF

KELLY AKASHI / J. SMITH-CAMERON / WILLY CHAVARRIA / JUDY CHICAGO / ELLA EMHOFF / HODAKOVA / OTTESSA MOSHFEGH

LESLIE ODOM JR. / NICOLAS PARTY / JACK PIERSON / MICKALENE THOMAS / RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA / EMMA SELIGMAN / SABLE ELYSE SMITH

KELLY AKASHI / J. SMITH-CAMERON / WILLY CHAVARRIA / JUDY CHICAGO / ELLA EMHOFF / HODAKOVA / OTTESSA MOSHFEGH

LESLIE ODOM JR. / NICOLAS PARTY / JACK PIERSON / MICKALENE THOMAS / RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA / EMMA SELIGMAN / SABLE ELYSE SMITH

BEYOND BELIEF

DINING SHOPPING CULTURE

DESIGN

miamidesigndistrict.net/beyond-belief

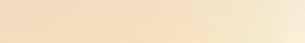

Future residences located at:

10245 Collins Avenue, Bal Harbour, FL 33154

ORAL REPRESENTATIONS CANNOT BE RELIED UPON AS CORRECTLY STATING THE REPRESENTATIONS OF THE DEVELOPER. FOR CORRECT REPRESENTATIONS, MAKE REFERENCE TO THIS BROCHURE AND TO THE DOCUMENTS REQUIRED BY SECTION 718.503, FLORIDA STATUTES, TO BE FURNISHED BY A DEVELOPER TO A BUYER OR LESSEE. RIVAGE BAL HARBOUR CONDOMINIUM (the “Condominium”) is developed by Carlton Terrace Owner LLC (“Developer”) and this offering is made only by the Developer’s Prospectus for the Condominium. Consult the Developer’s Prospectus for the proposed budget, terms, conditions, specifications, fees, and Unit dimensions. Sketches, renderings, or photographs depicting lifestyle, amenities, food services, hosting services, finishes, designs, materials, furnishings, fixtures, appliances, cabinetry, soffits, lighting, countertops, floor plans, specifications, design, or art are proposed only, and the Developer reserves the right to modify, revise, or withdraw any or all of the same in its sole discretion. No specific view is guaranteed. Pursuant to license agreements, Developer also has a right to use the trade names, marks, and logos of: (1) The Related Group; and (2) Two Roads Development, each of which is a licensor. The Developer is not incorporated in, located in, nor a resident of, New York. This is not intended to be an offer to sell, or solicitation of an offer to buy, condominium units in New York or to residents of New York, or of any other jurisdiction where prohibited by law. 2023 © Carlton Terrace Owner LLC, with all rights reserved.

60

RULES TO LIVE BY CULTURED asks six sartorial voices to share their advice for a life well and luxuriously lived.

A WELL-ADORNED HAND

With a string of museum collaborations on the way, Los Angeles–based designer Jess Hannah Révész dives deep into the art historical canon, crafting jewelry with a will to endure.

FOR MICHAEL STEWART, THE BODY IS A LANDSCAPE

The London-based designer’s sculptural fashion label, Standing Ground, built its credo on Irish mysticism, fantasy classics, and an intuitive approach to craft.

78 80 84

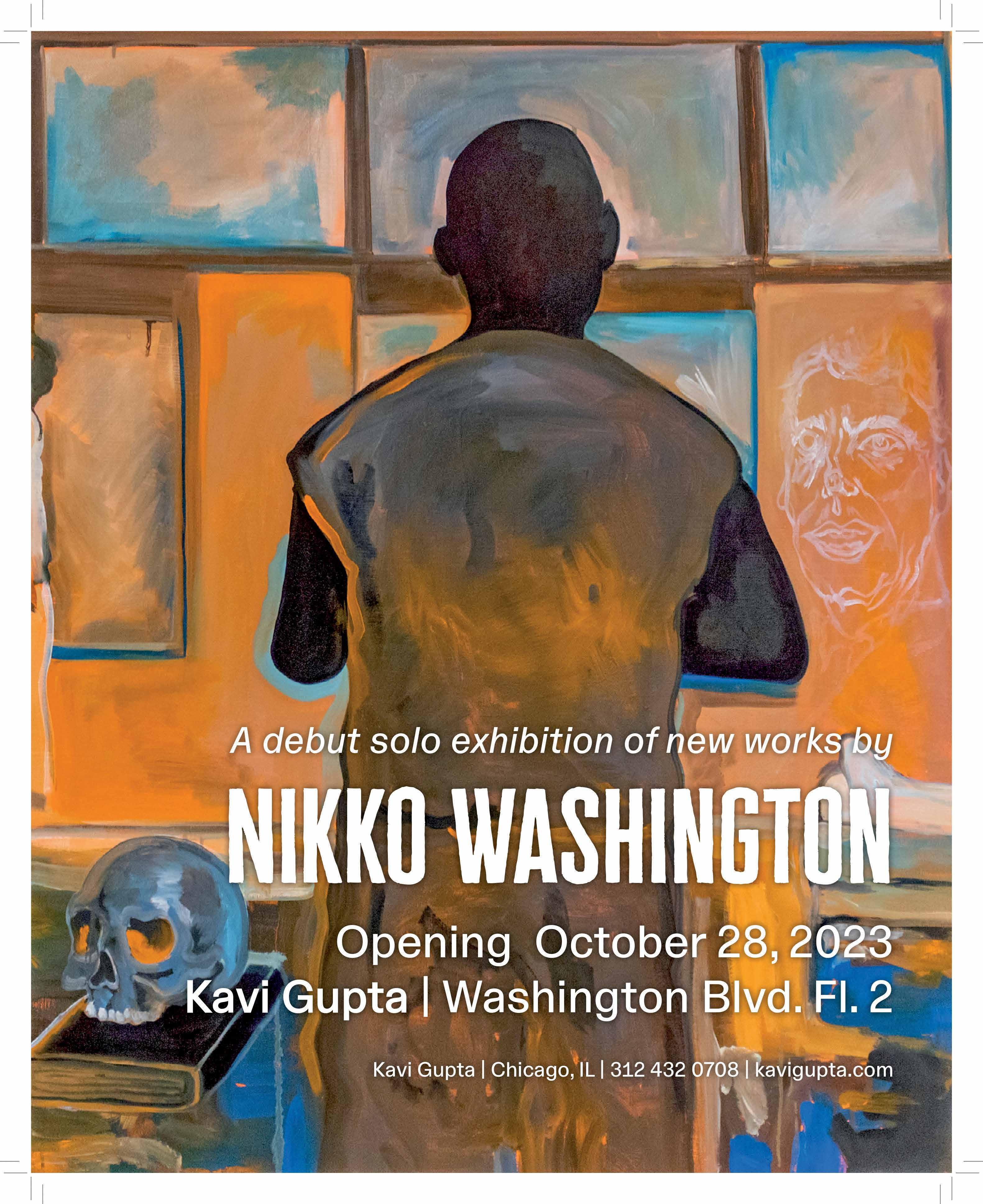

PAINTING FOR THE END TIMES

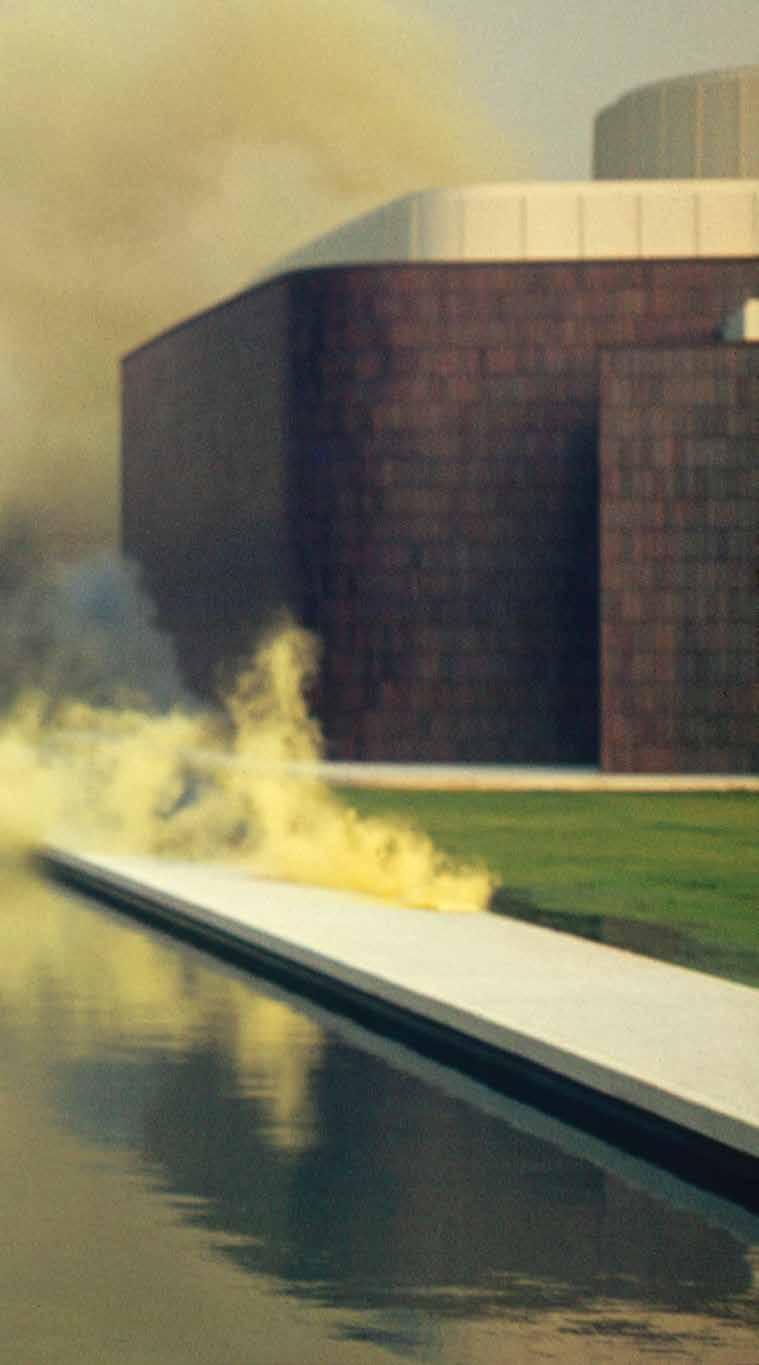

WE ARE IN THE SOUP NOW Rirkrit Tiravanija’s inaugural U.S. survey, “A LOT OF PEOPLE,” will fill MoMA PS1’s halls this October.

KELLY AKASHI’S TIME MACHINE

The Los Angeles–based artist’s galaxyspanning practice will be honored with two West Coast exhibitions this season.

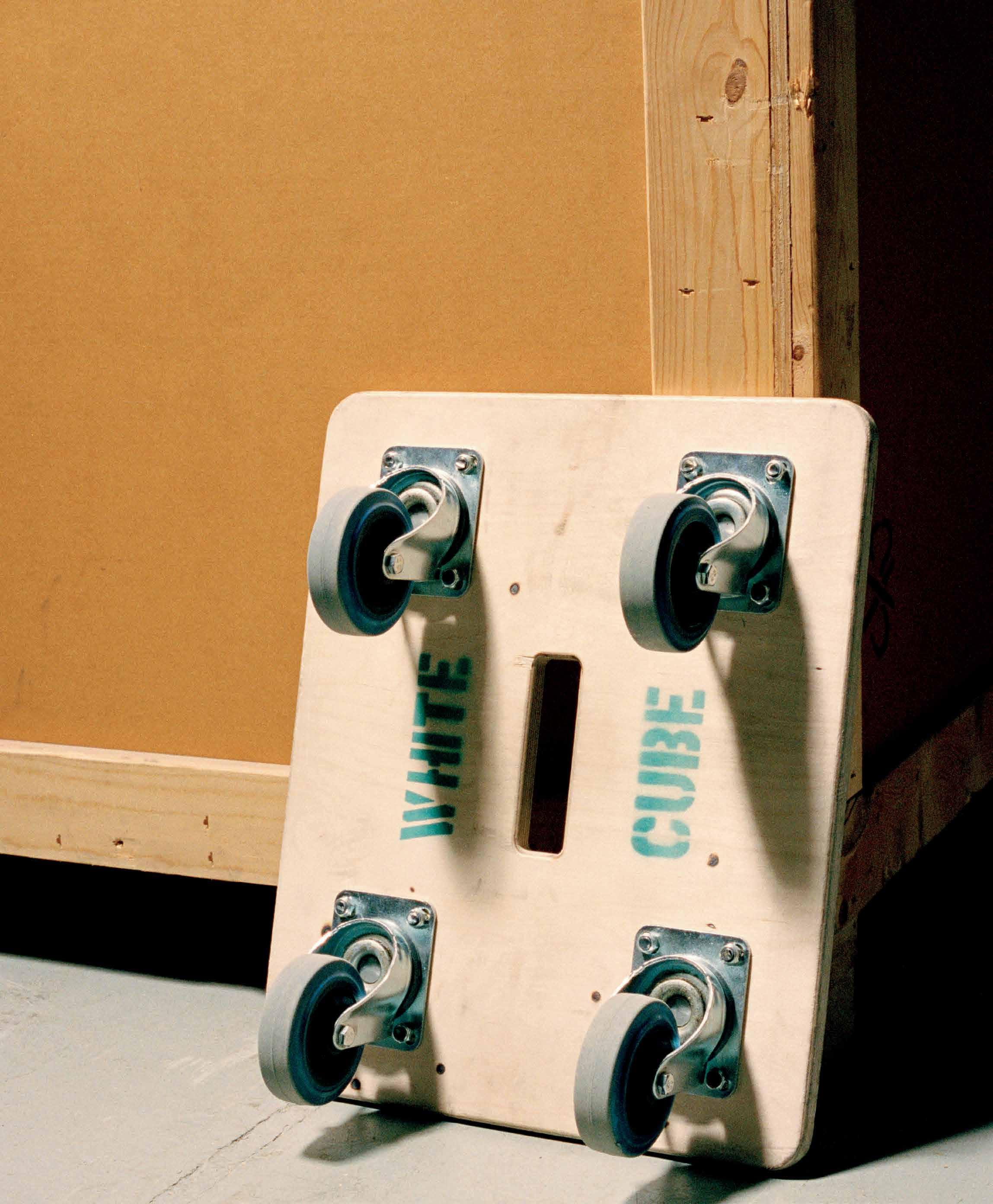

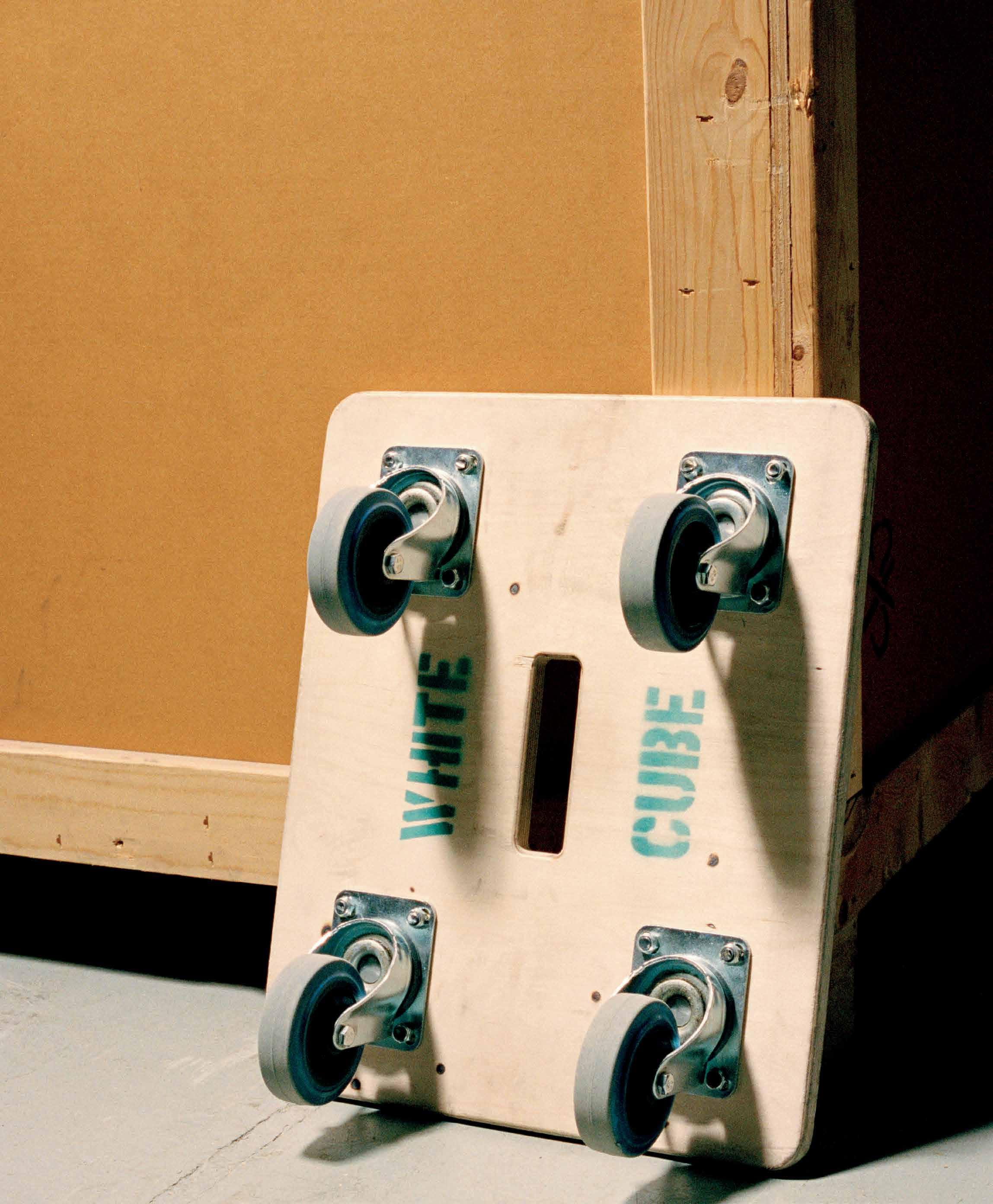

WHITE CUBE HAS FOUND A HOME IN NEW YORK. JUST DON’T CALL IT AN OUTPOST

The British gallery opens its first permanent U.S. branch with an inaugural group show.

88 90 98 104

THE FOREIGN AND THE FAMILIAR

Whether in her art-filled West Village townhouse or in her namesake clothing line, Veronica de Piante weaves together subtle references from her global upbringing to mesmerizing effect.

CONTENTS September 2023

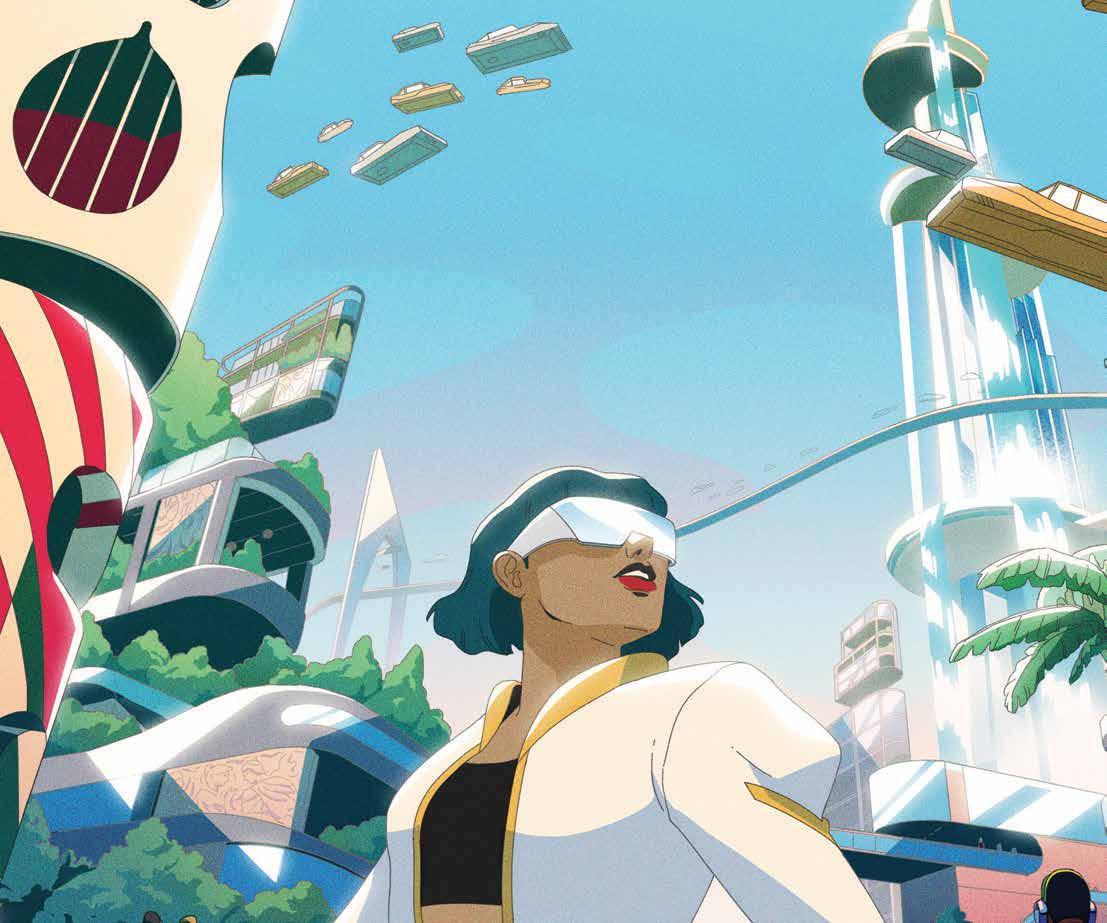

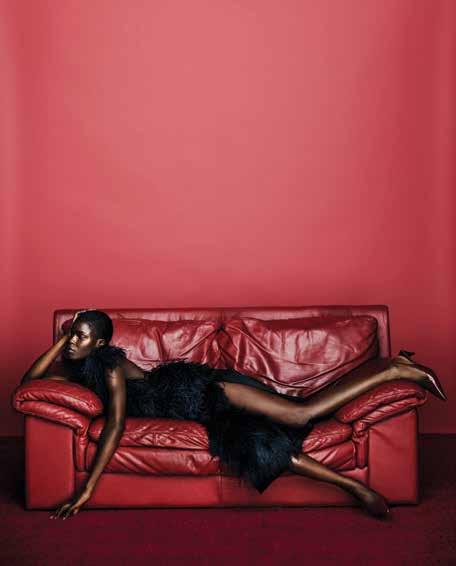

Hari Nef wears a full look by Marni. Photography by Torso Solutions. 42 culturedmag.com

Swiss artist Nicolas Party’s latest works, on view at Hauser & Wirth in New York until late October, imagine epochs before and after mankind.

CONTENTS

September 2023

A SEAT AT THE TABLE

With the newly inaugurated Mickalene Thomas Scholarship at the Yale School of Art, collectors Carmine Boccuzzi and Bernard Lumpkin are offering one lucky student a chance to become the artist’s newest mentee.

ARE YOU LISTENING?

The full breadth of Judy Chicago’s work is finally getting the art world’s unmediated attention.

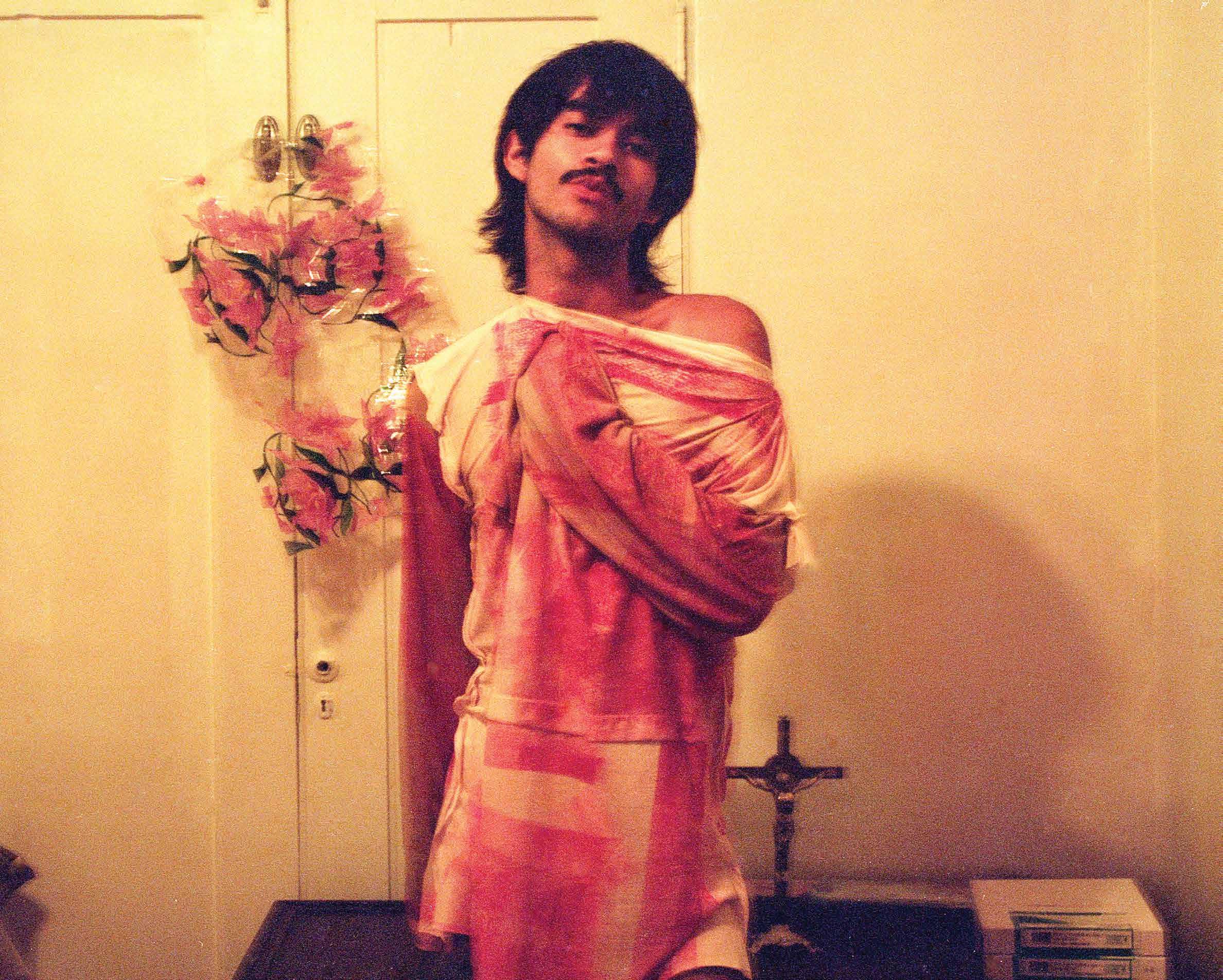

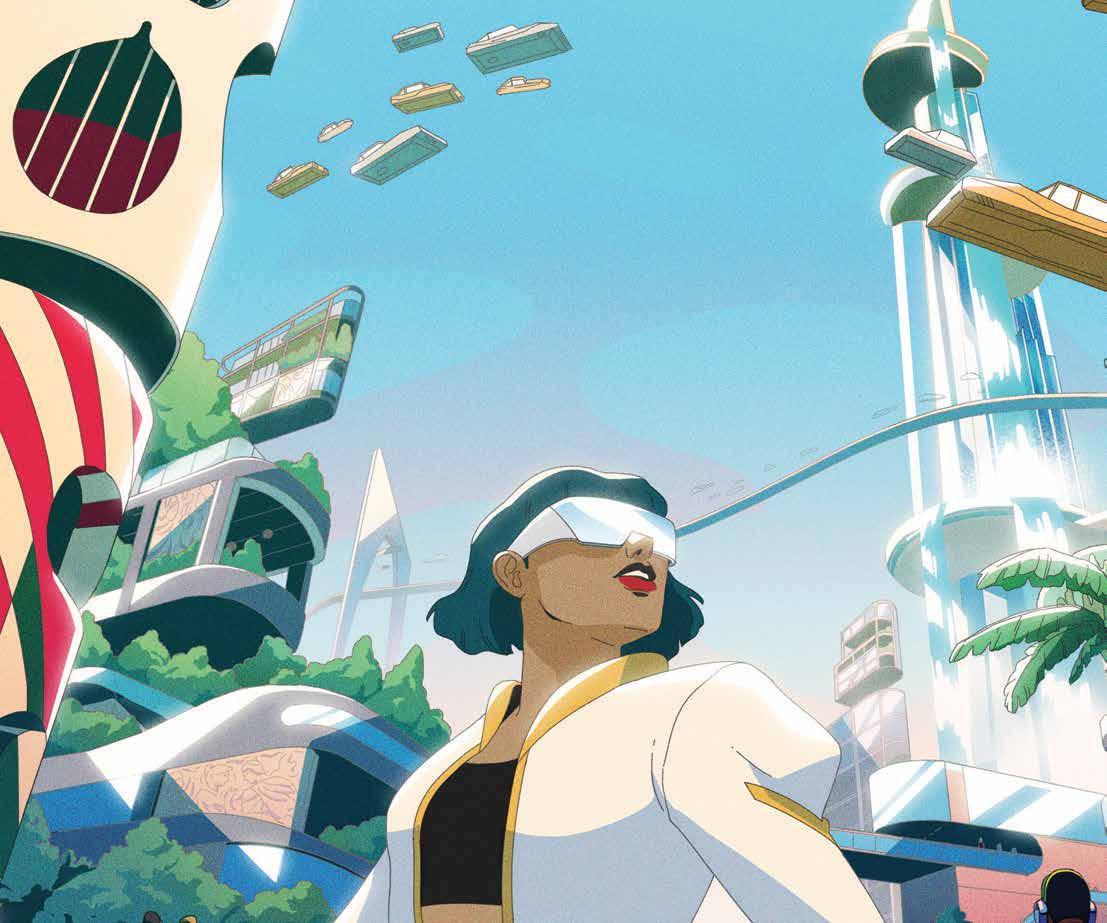

MEET THE NEXT GENERATION OF BREAKOUT DESIGNERS

The work of this year’s breakthrough designers—Lu’u Dan, Hodakova, DJ Chappel, and Zoe Gustavia Anna Whalen—captures the feeling of moving through our flawed, topsy-turvy world.

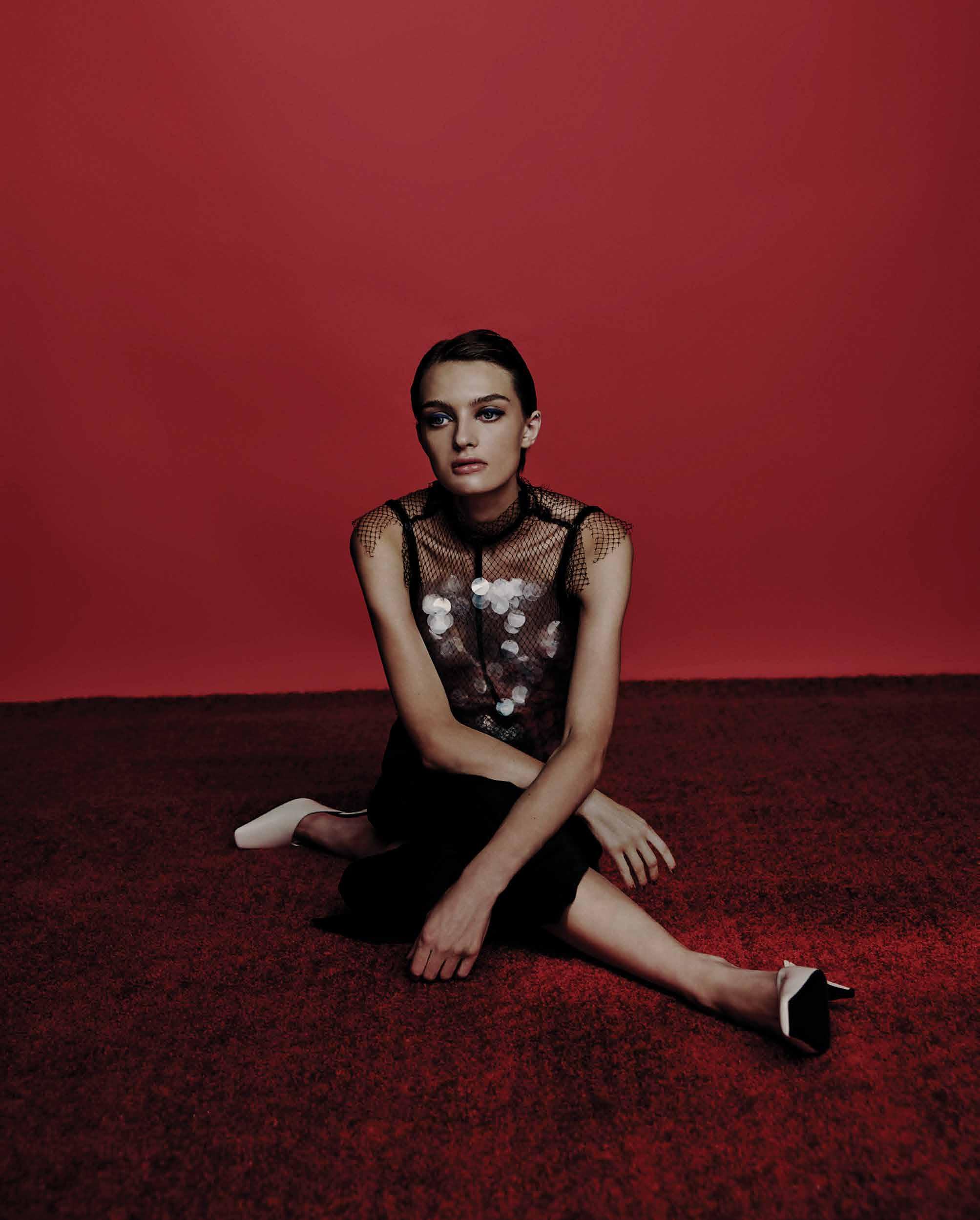

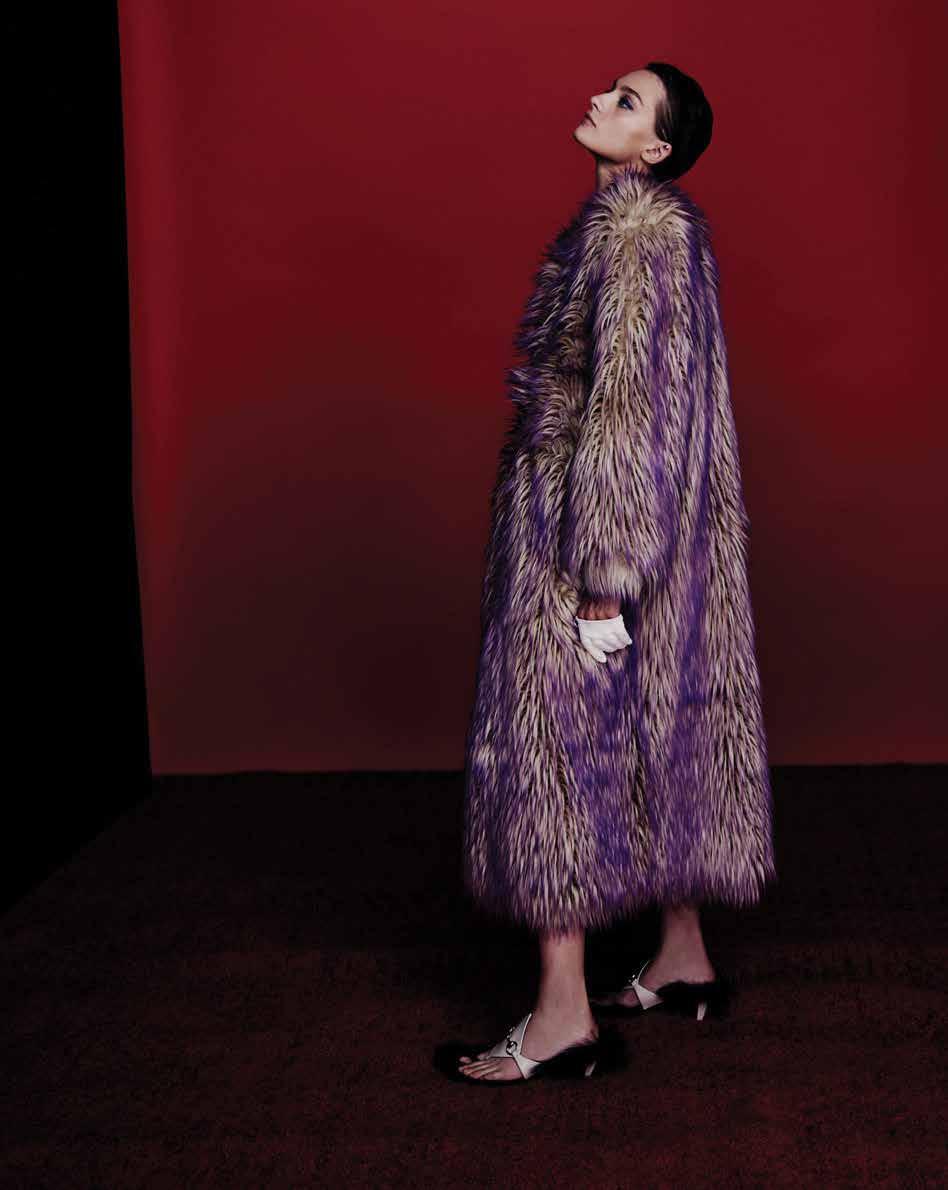

GUCCI’S NEW ERA

The Italian house’s Fall/Winter 2023 Women’s collection brings a vast archive to life in fresh and colorful ways.

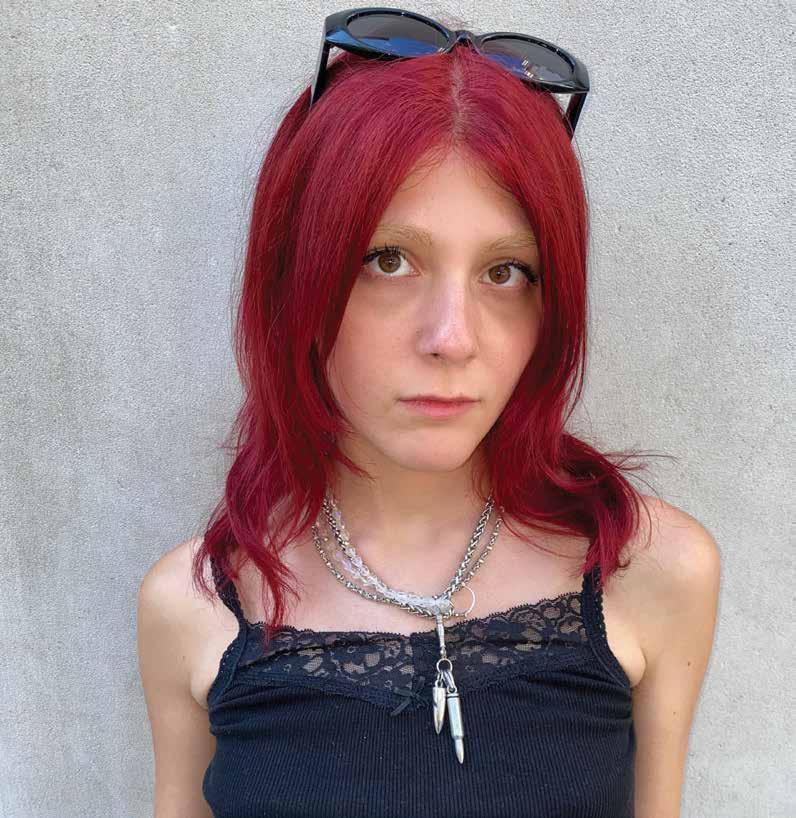

HARI

NEF BY TROYE SIVAN

As the actor prepares for a busy fall, Hari Nef calls up the pop icon Troye Sivan for a conversation about the strength of their friendship and the art of saying less.

THE FALL PLAYBOOK

Five discipline-spanning artists reflect on their journeys into a new era of their practice.

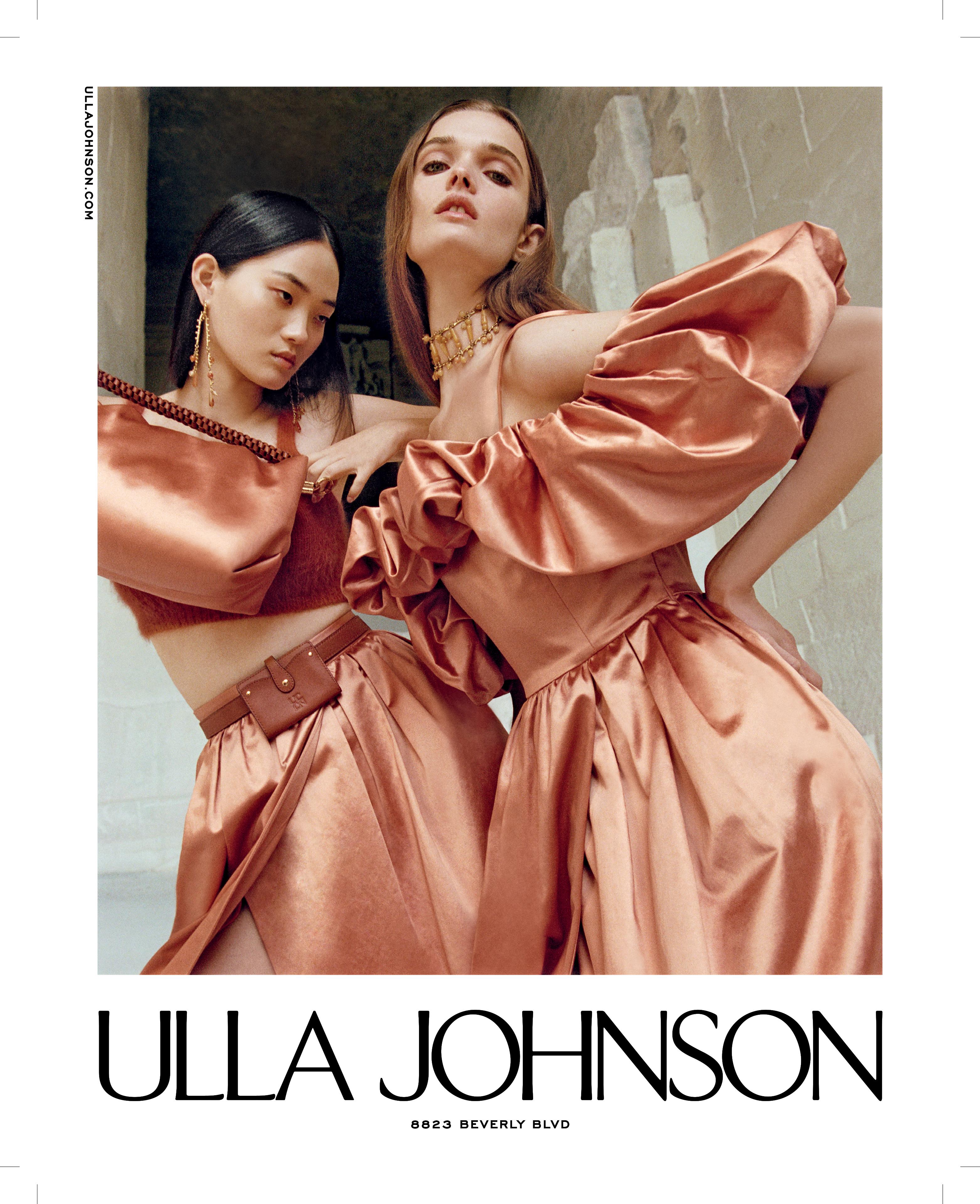

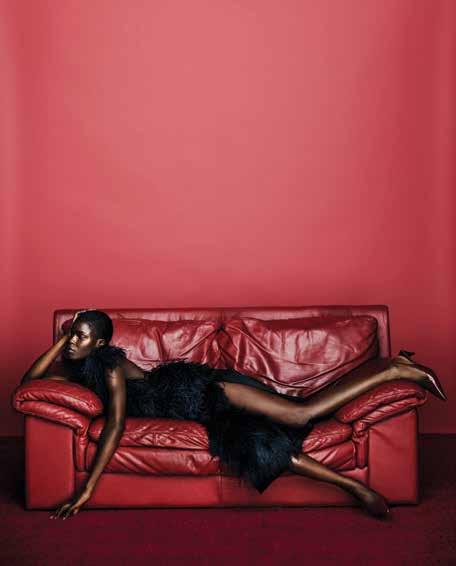

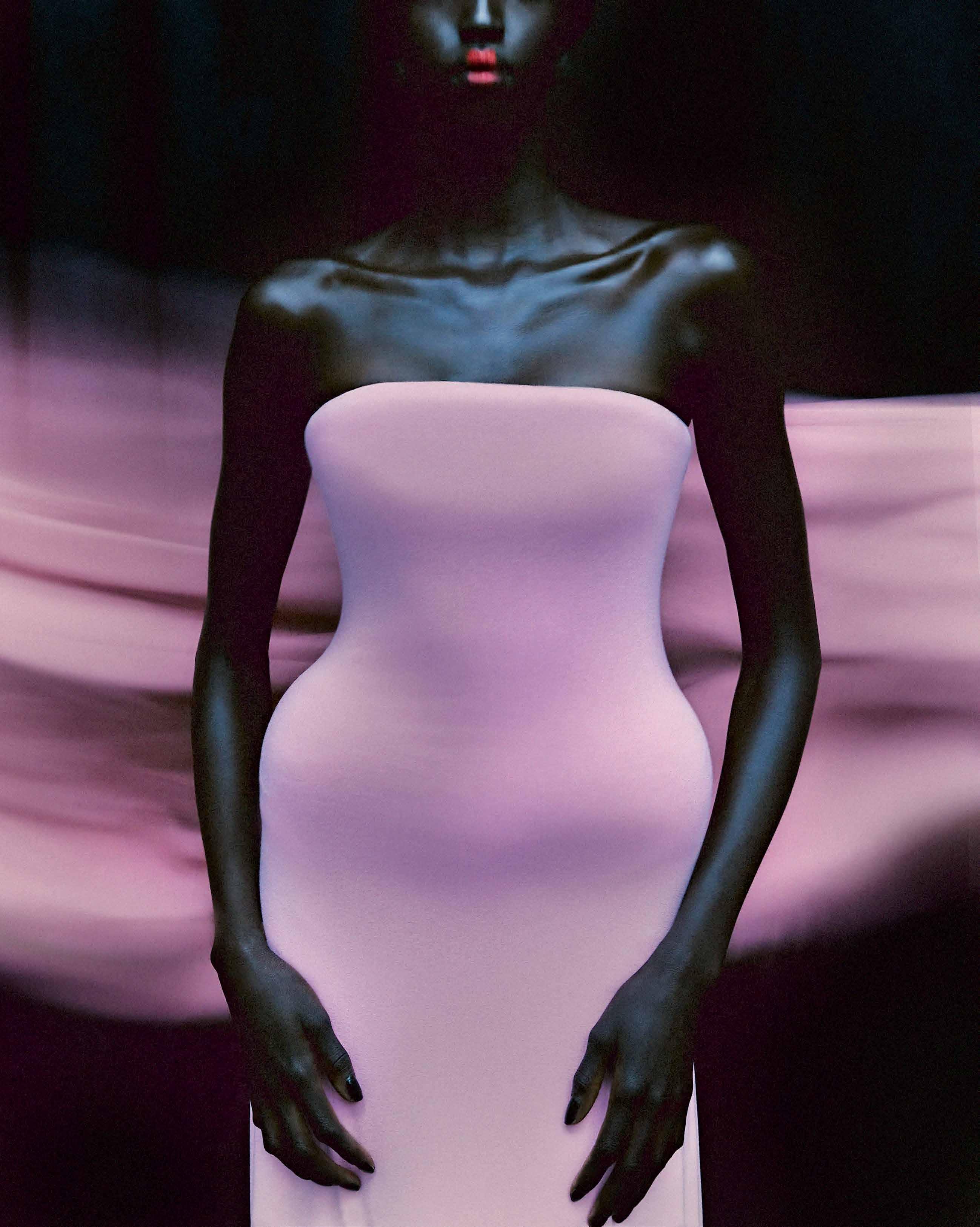

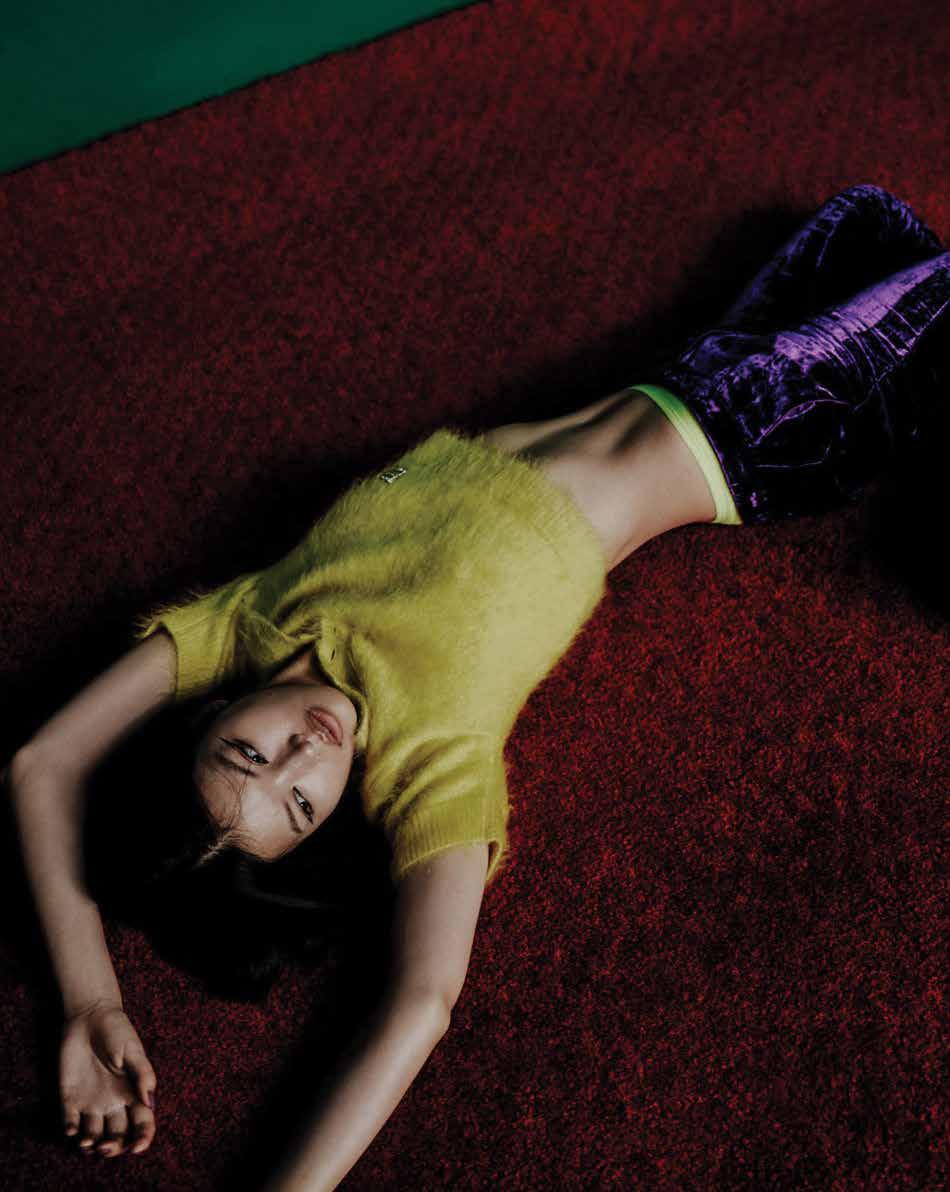

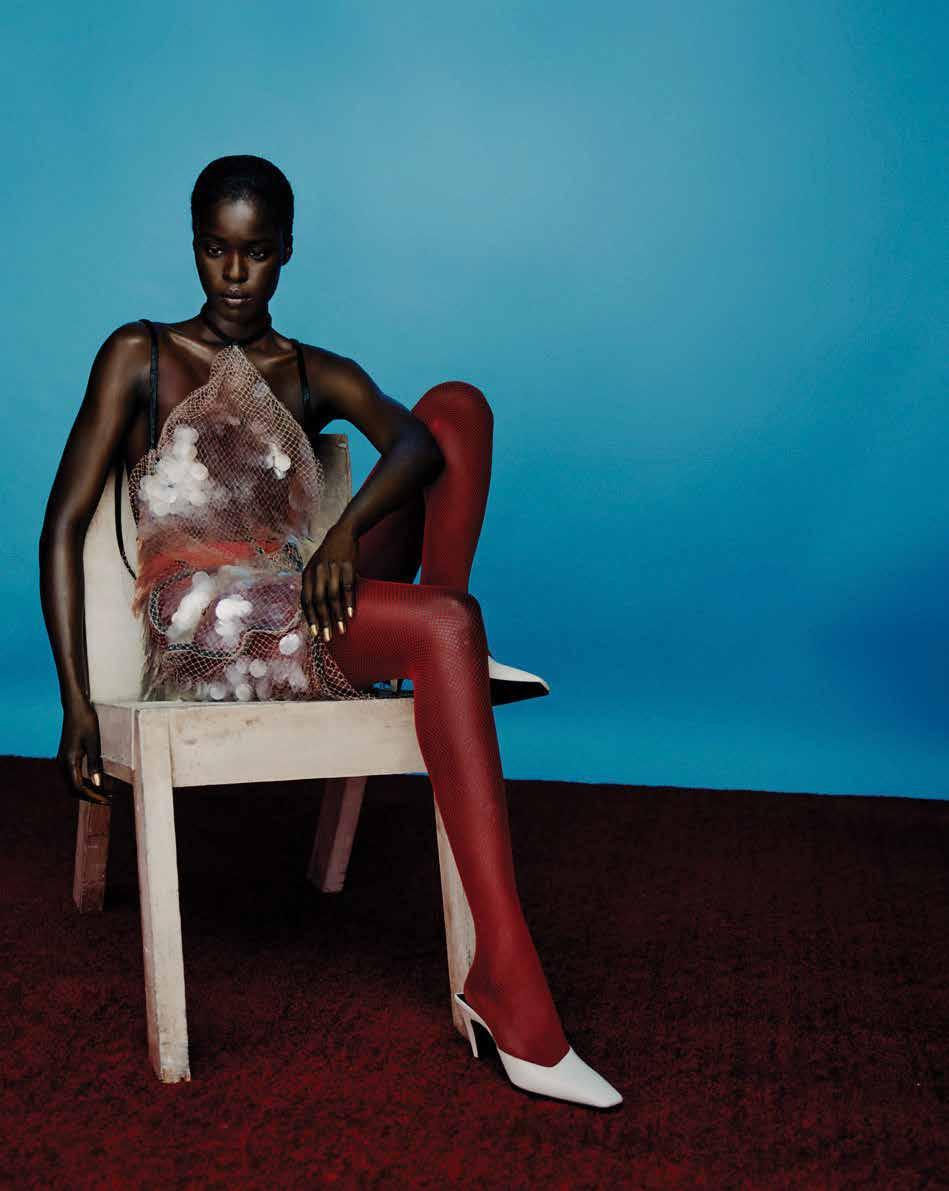

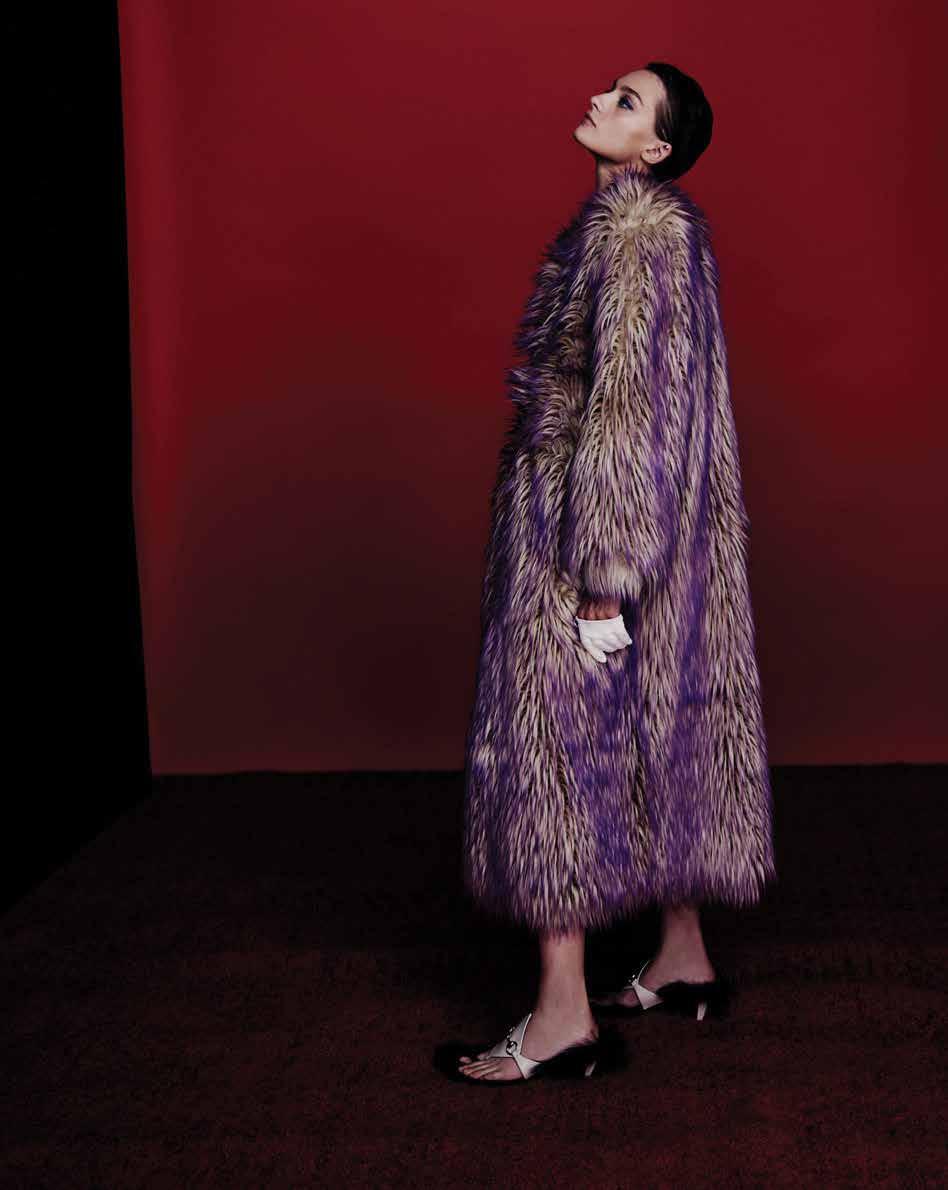

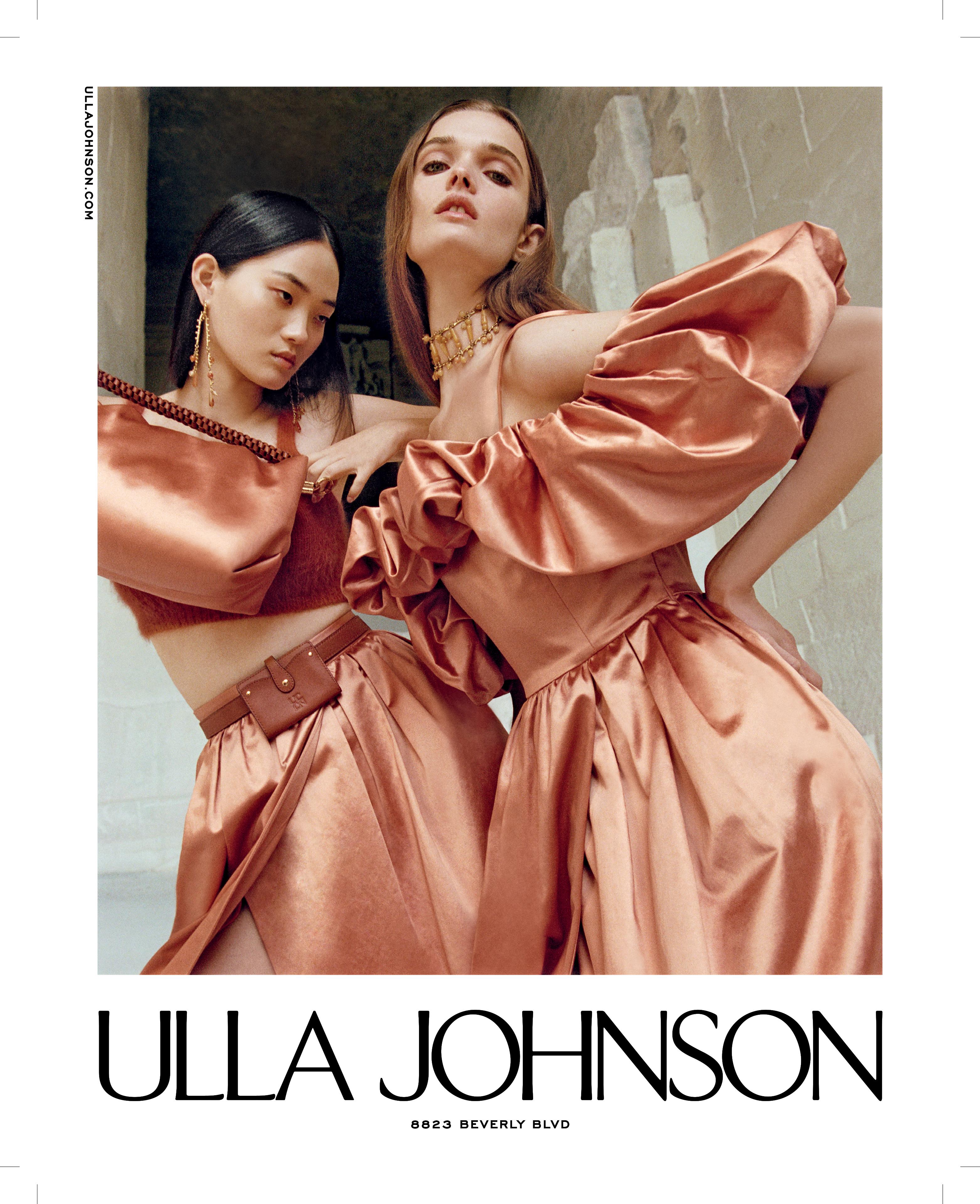

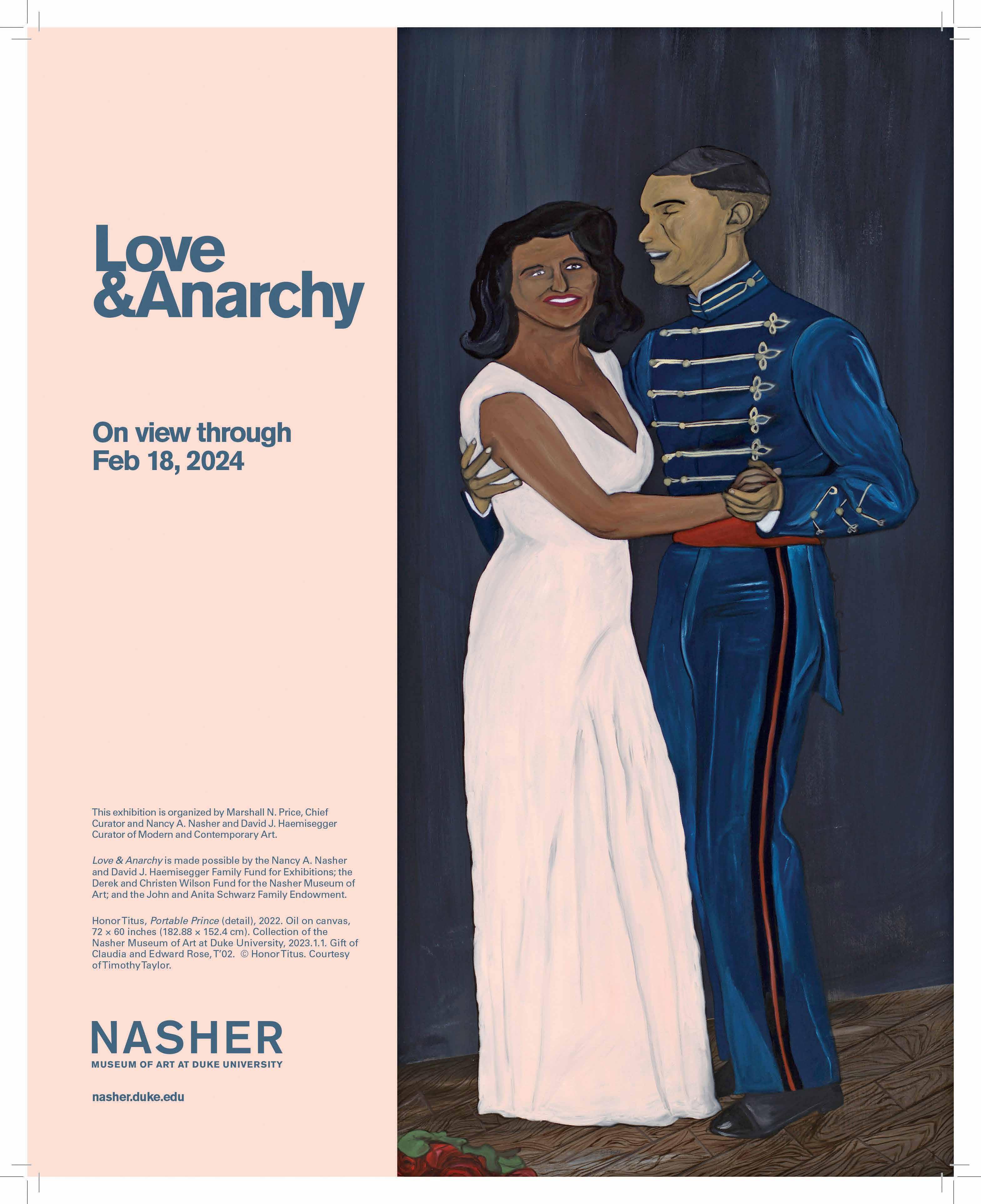

Julia Belyakova and Isha Senghore wear full looks by GUCCI. Photography by Drew Jarrett.

110 112 115 126

44 culturedmag.com

138 148

CONTENTS

160

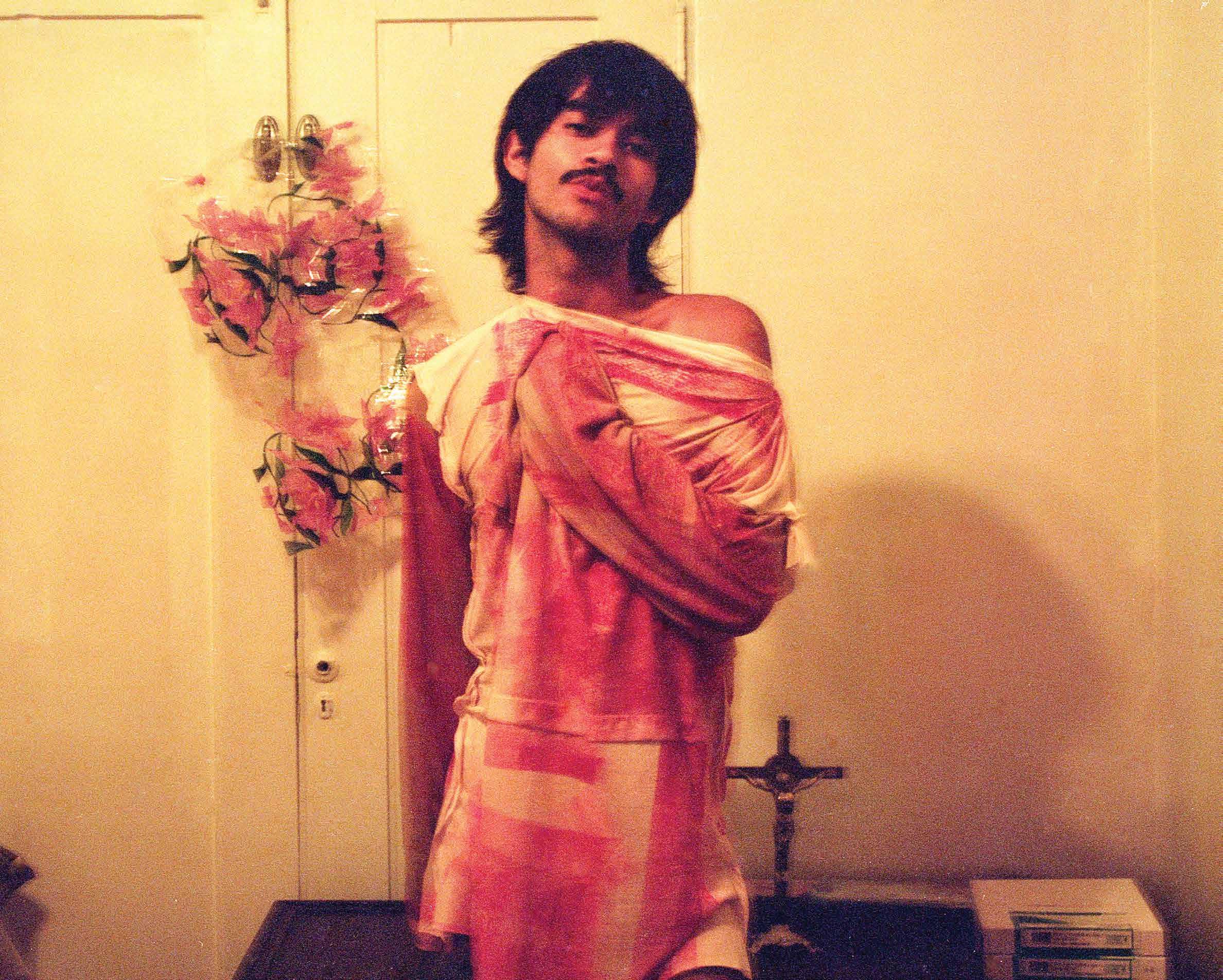

YOUNG PHOTOGRAPHERS 2023

The 11 individuals featured in CULTURED ’s inaugural Young Photographers list treat images like diaries, manifestos, recipes, and field studies.

172

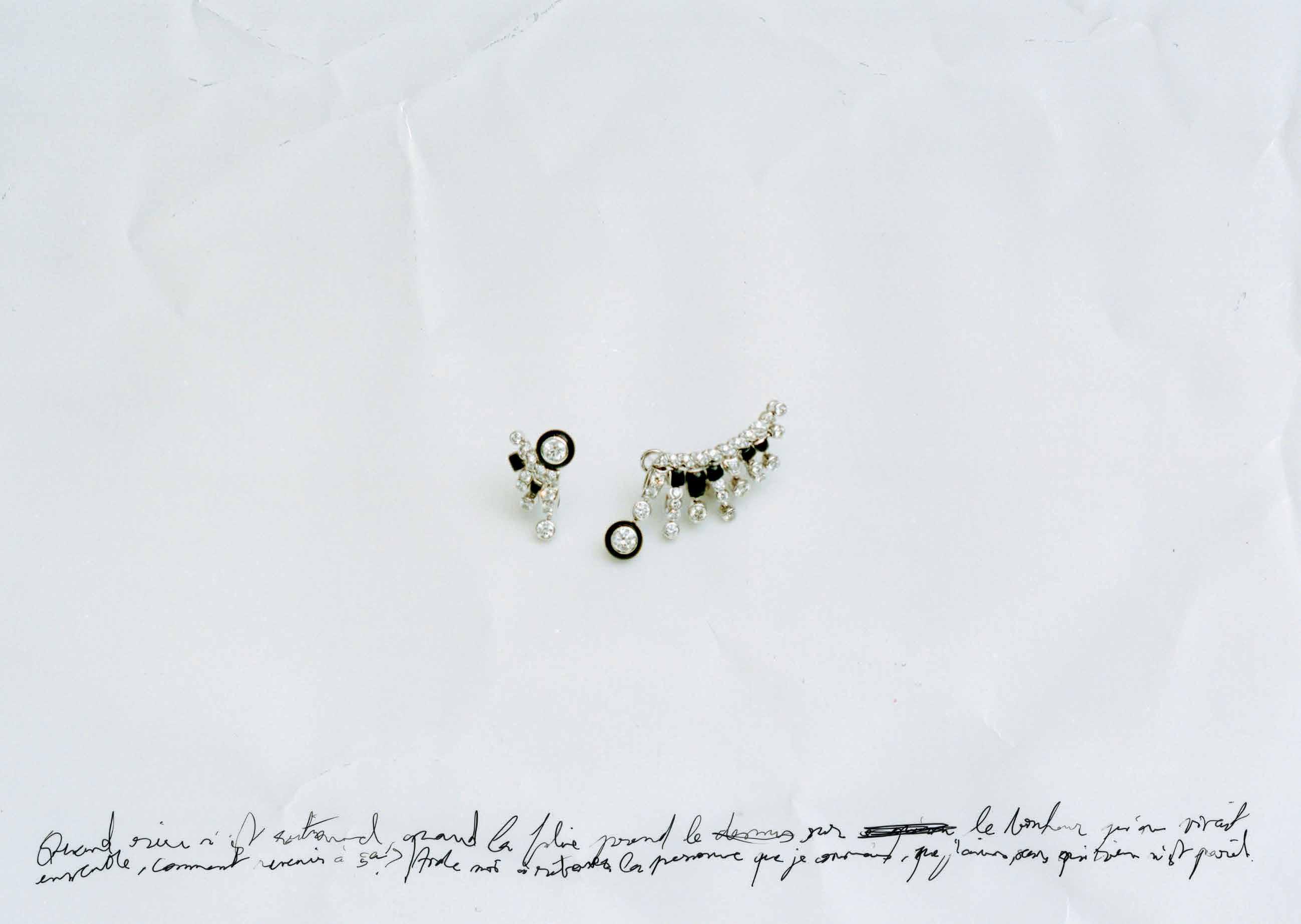

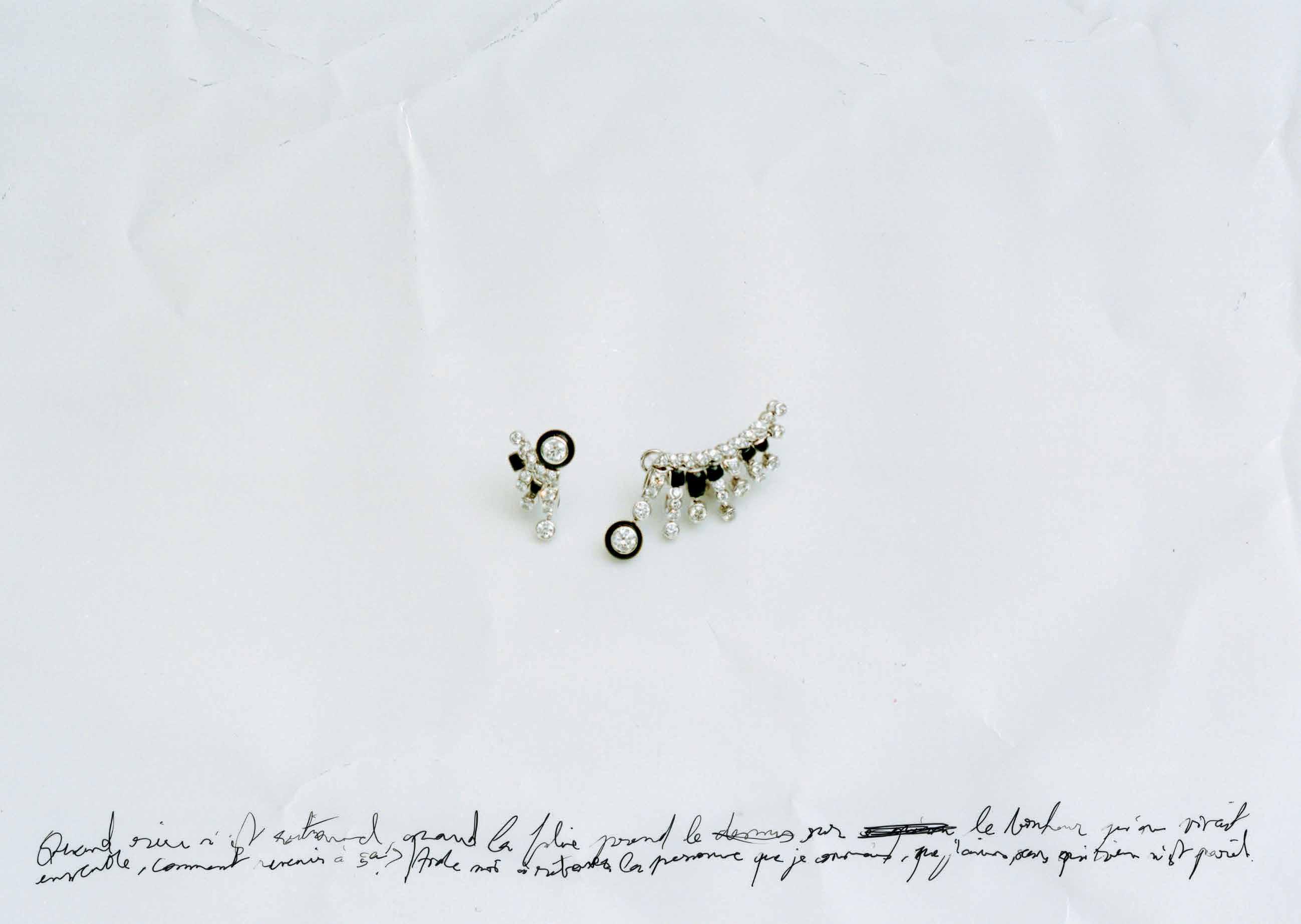

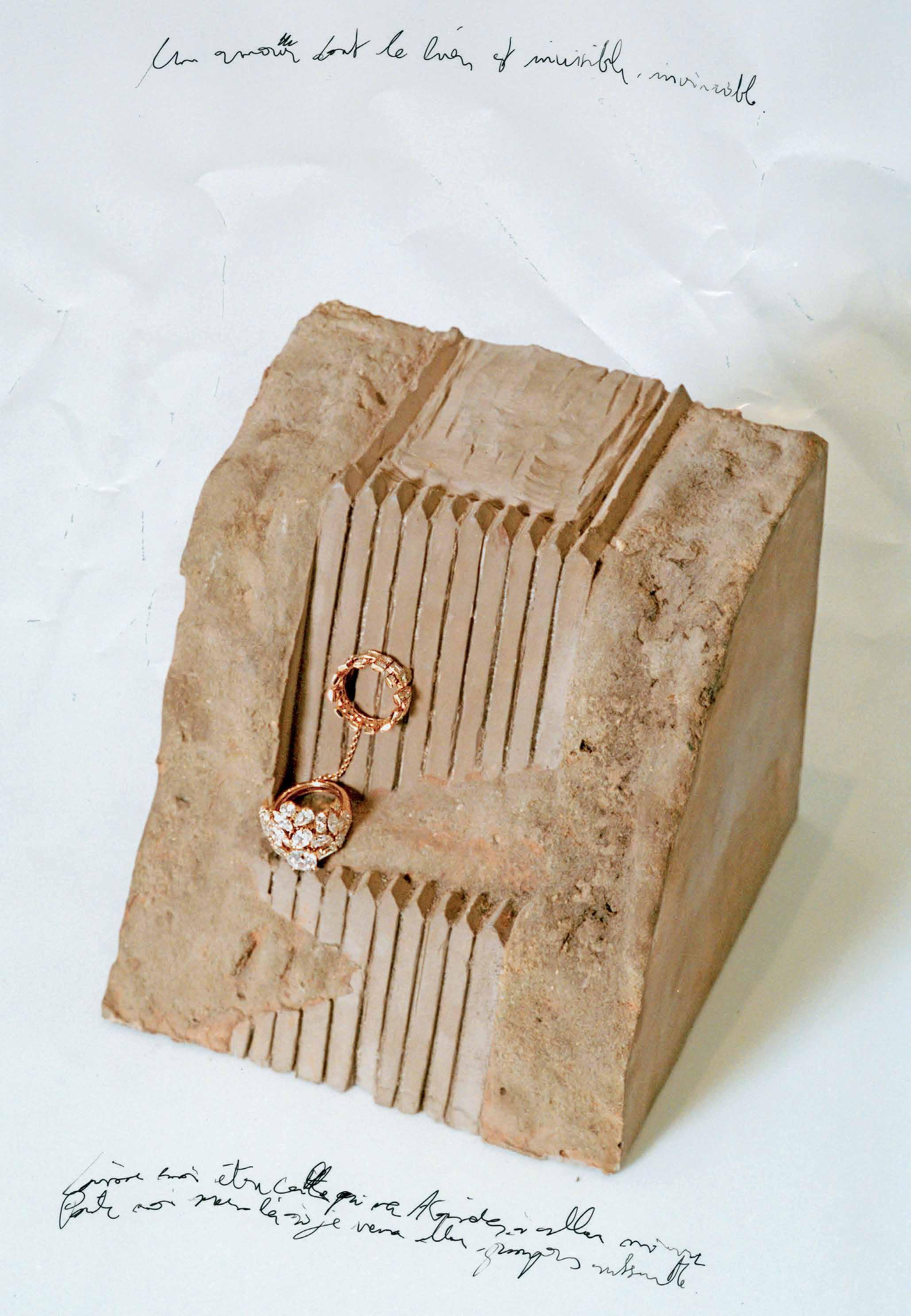

THE TIES THAT BIND

In the spirit of Tiffany & Co.’s new collection, six New York creatives reflect on the role of chosen family—the people we discover in the wild and keep with us—in making a life, and making work.

182

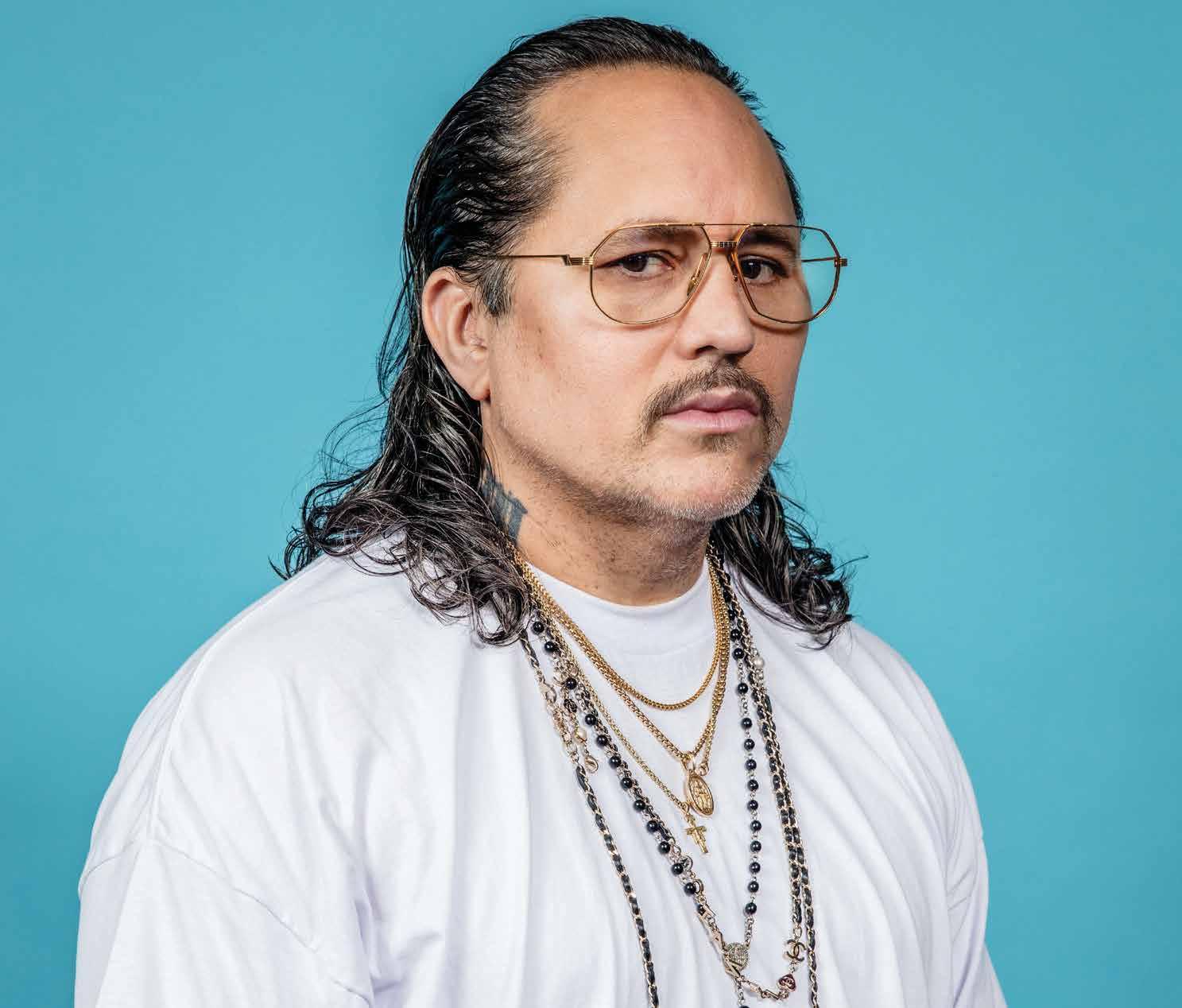

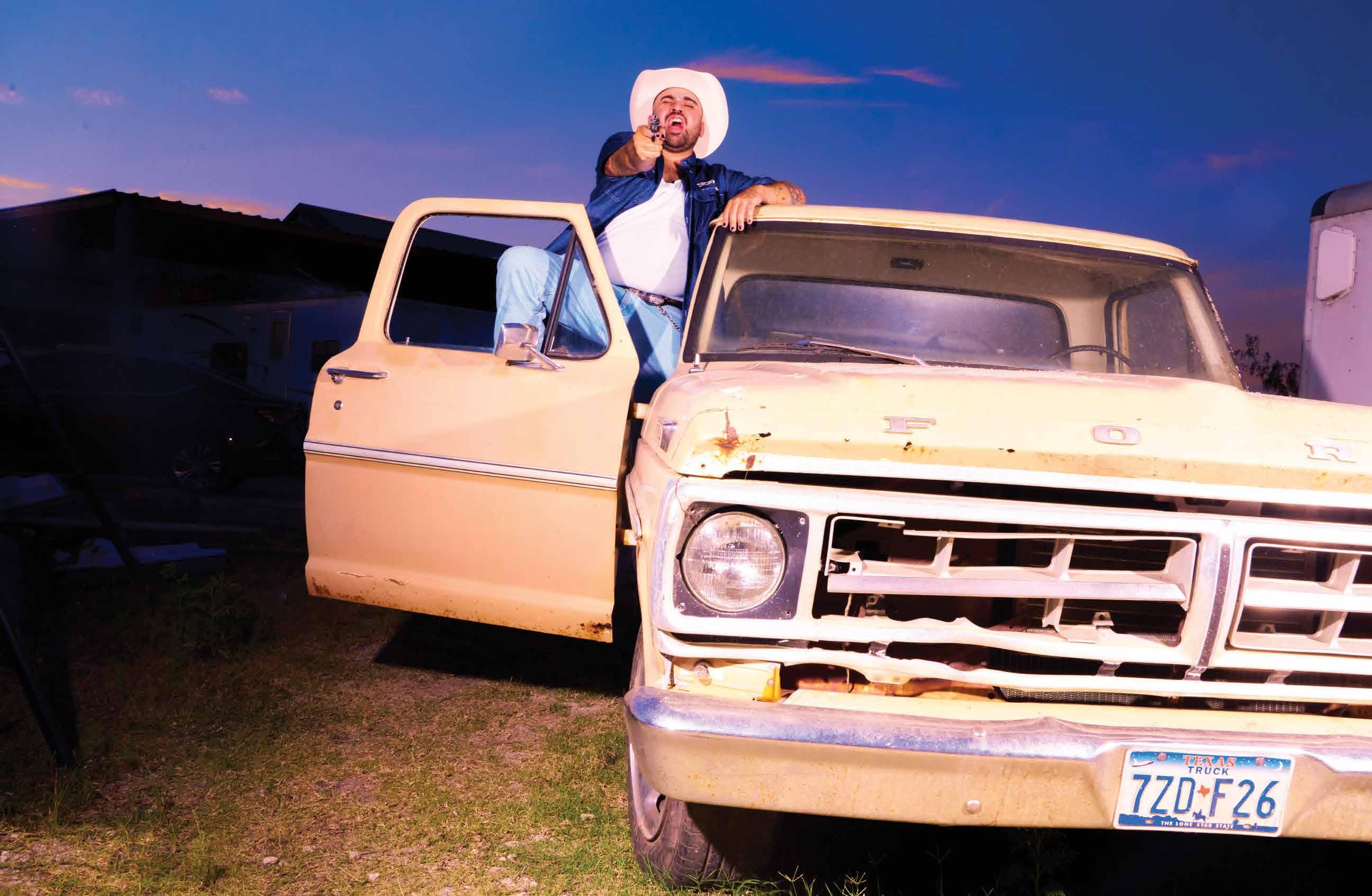

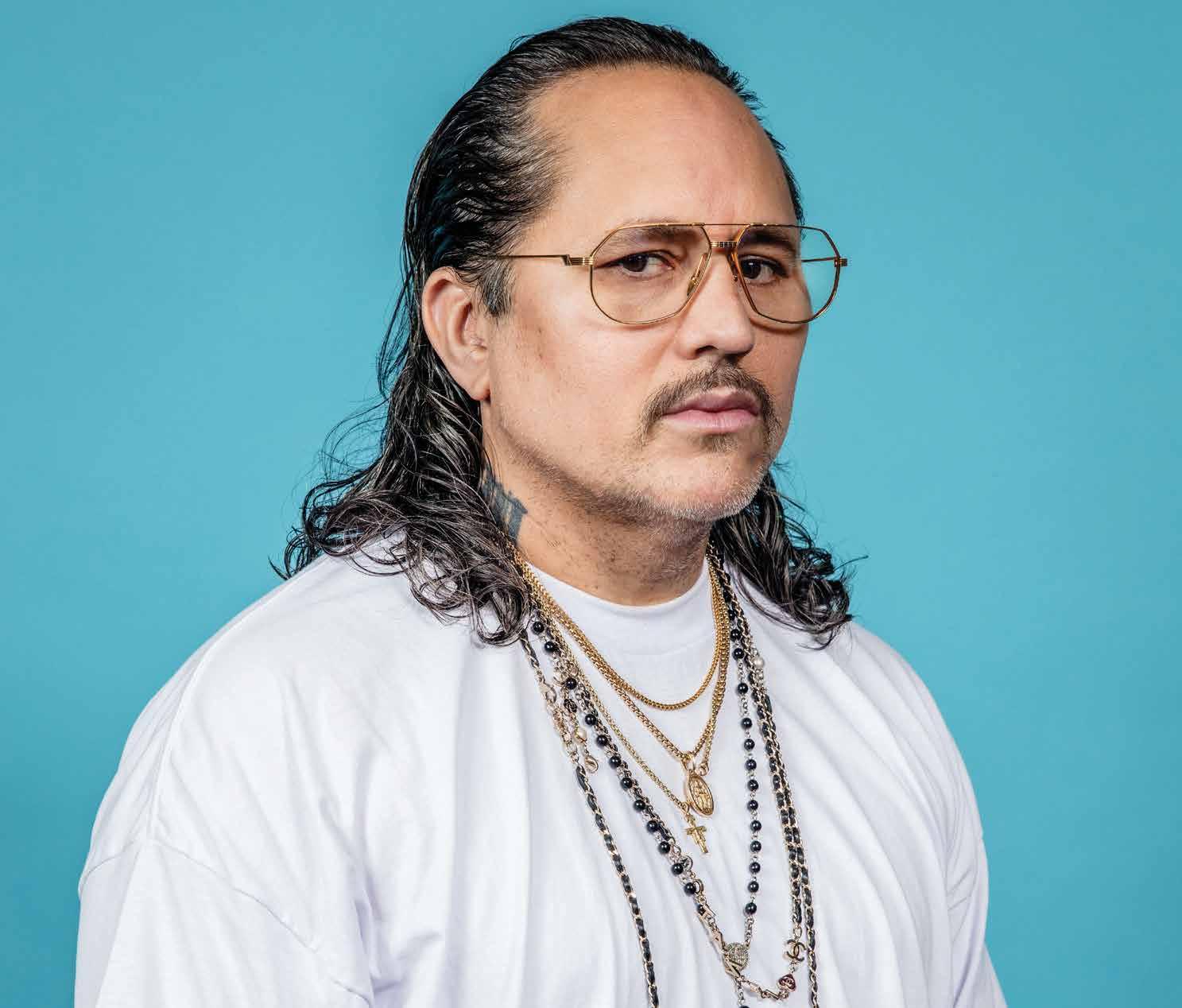

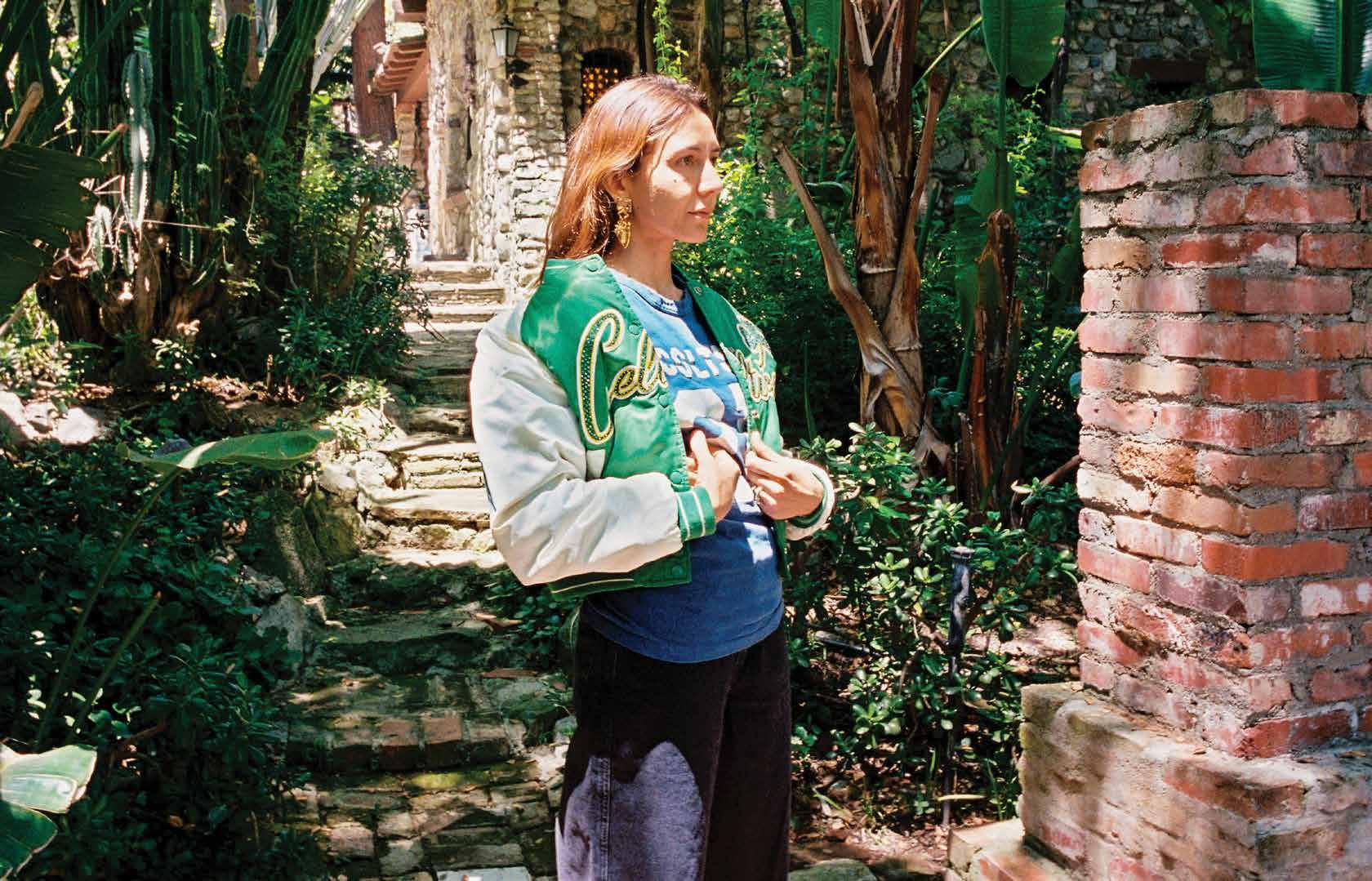

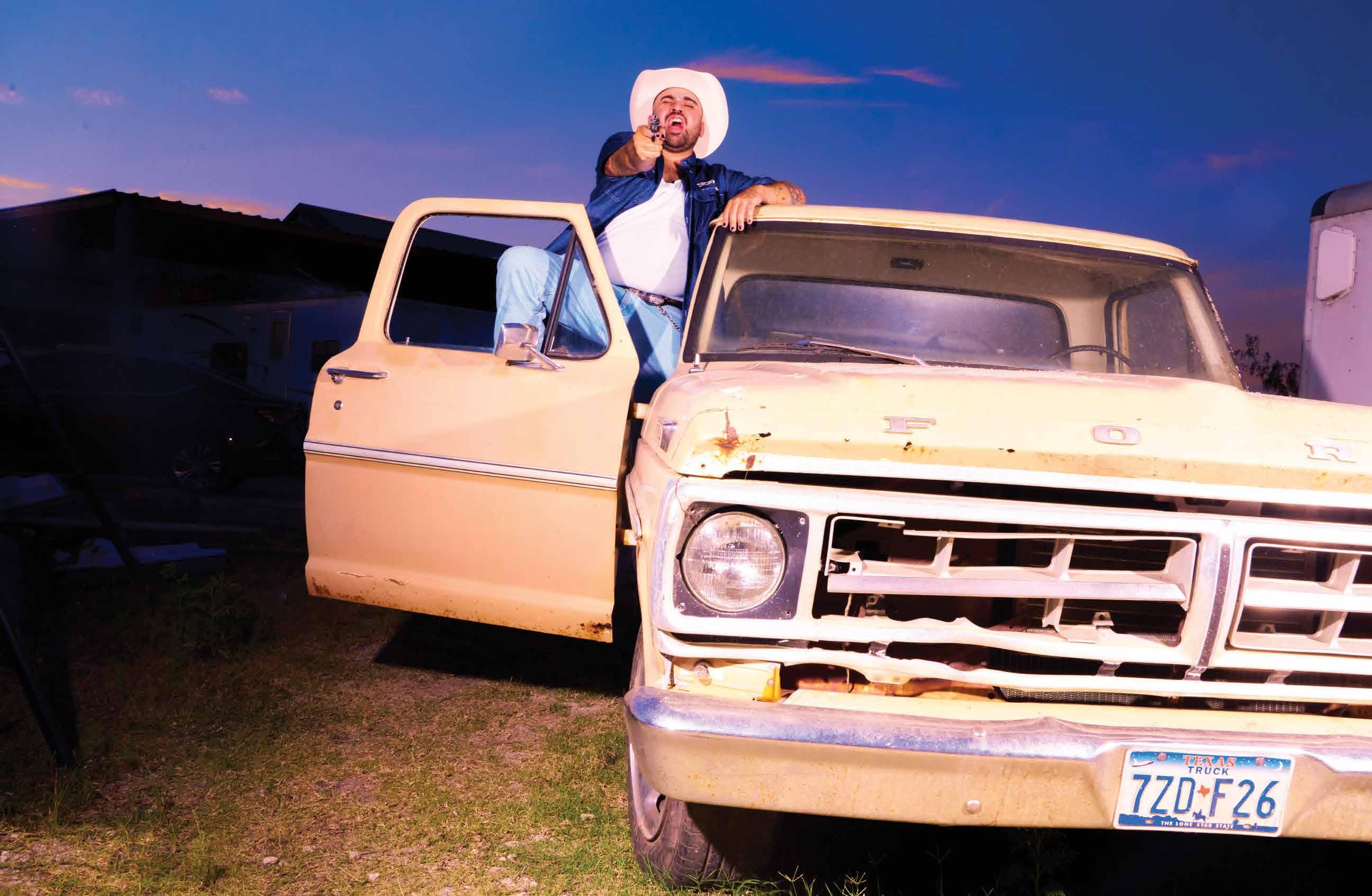

WILLY CHAVARRIA’S AMERICAN PLAYGROUND

The New York–based designer shows CULTURED the places, and the people, that shaped his Spring/ Summer 2024 collection.

188

Veronica

196

STITCHES IN TIME

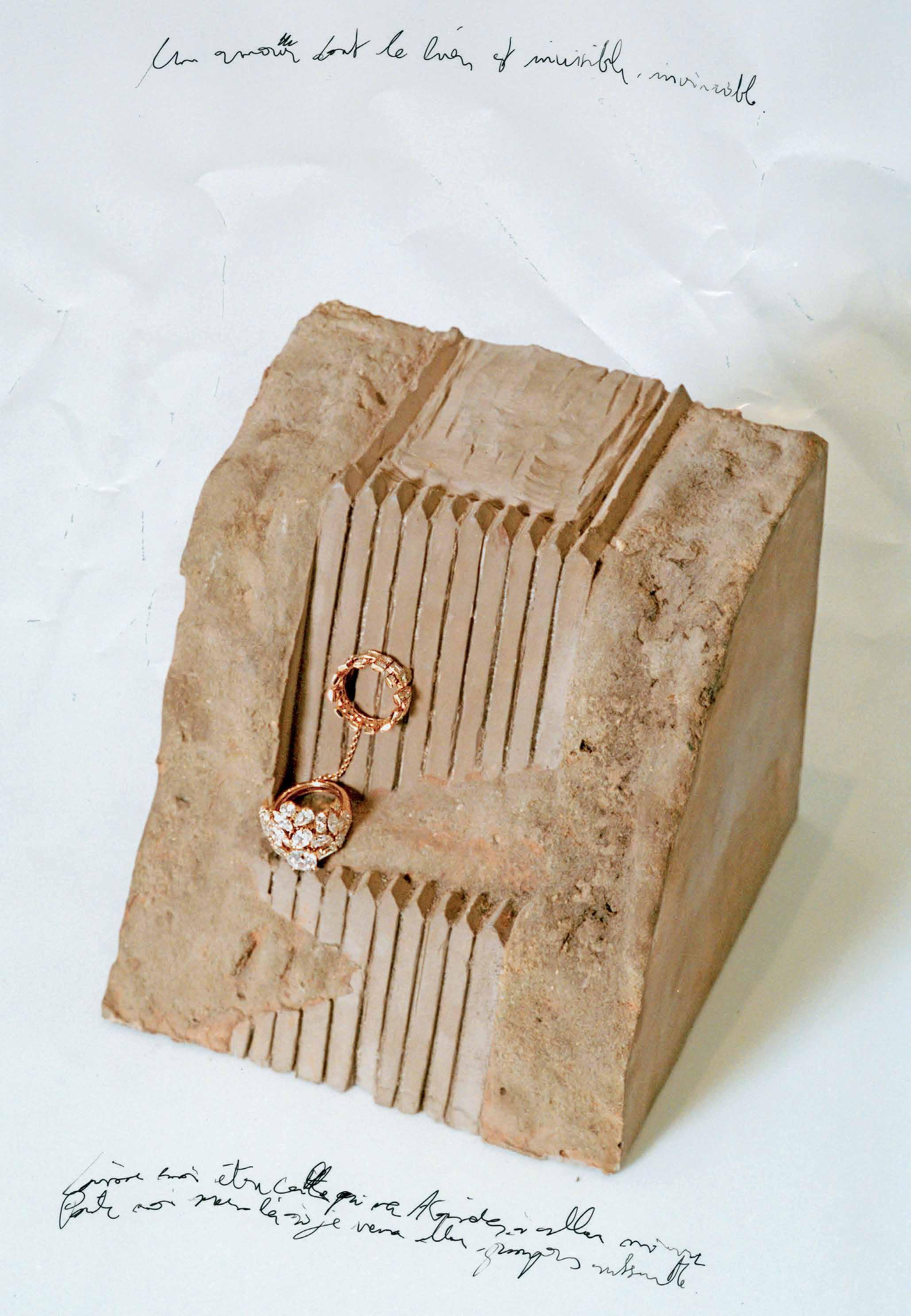

Chanel’s Fine Jewelry Creative Studio Director Patrice Leguéreau translates the ethos of the house’s signature textile into this season’s high jewelry collection.

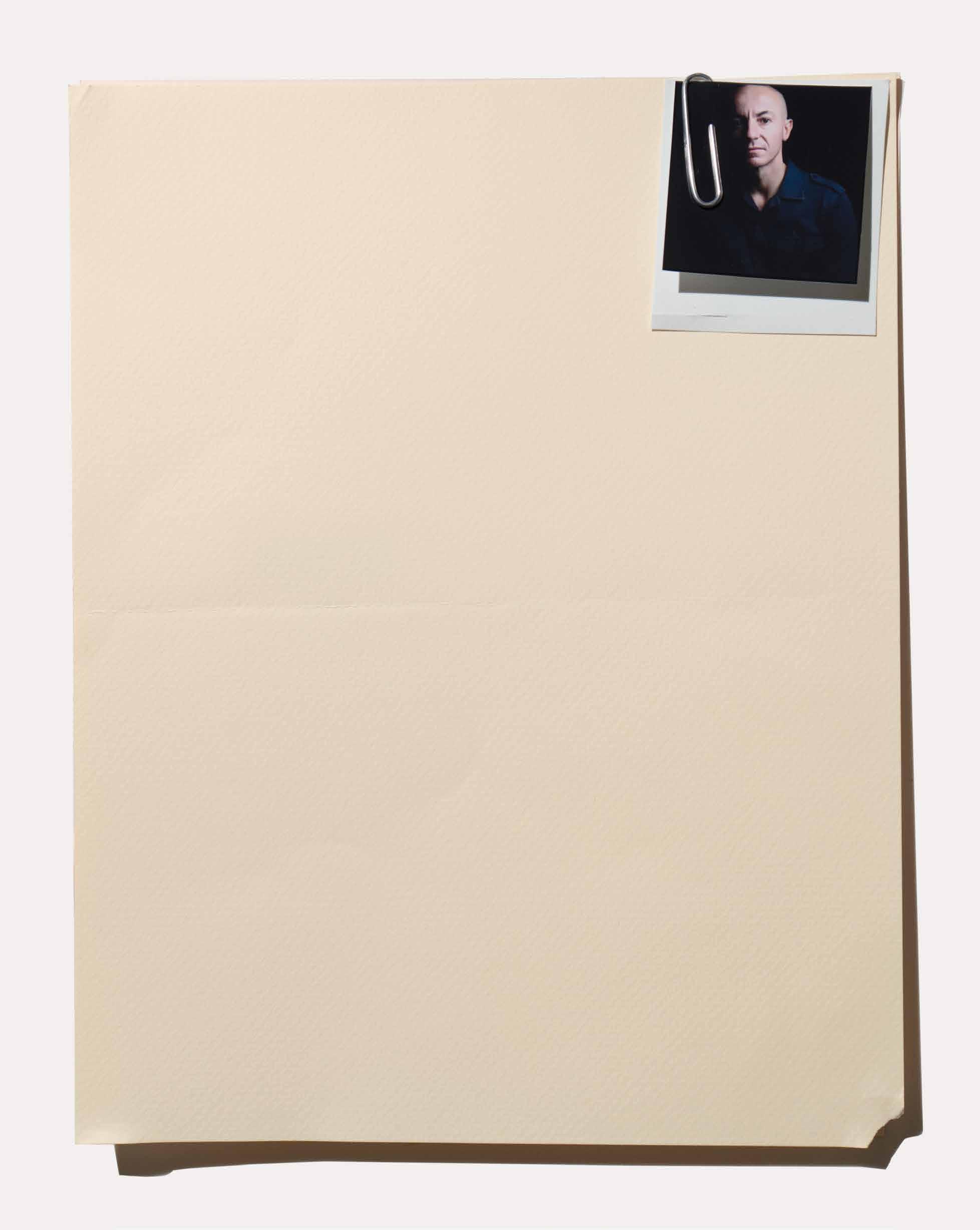

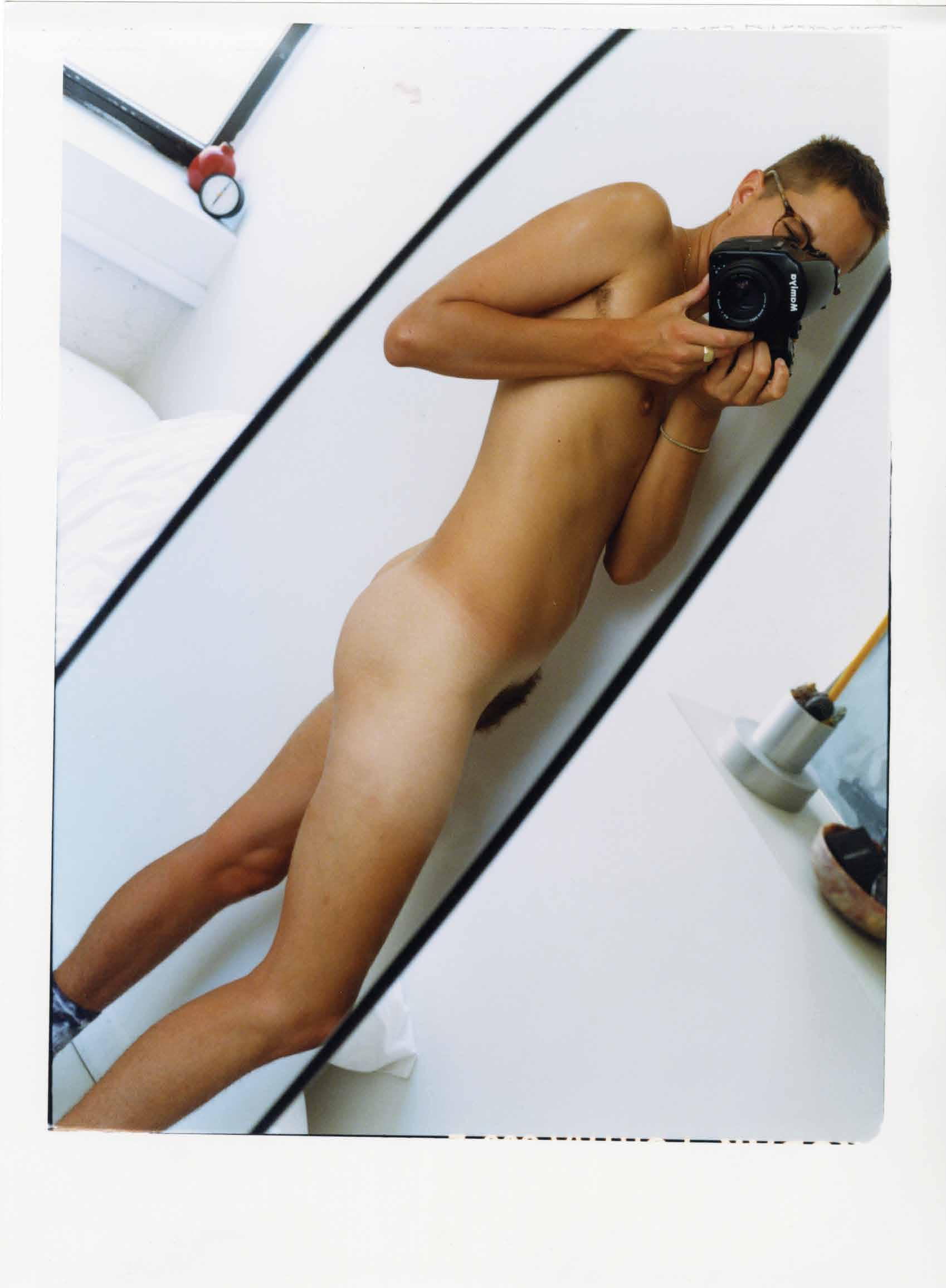

THE RETURN OF THE MAIL-ORDER MAN

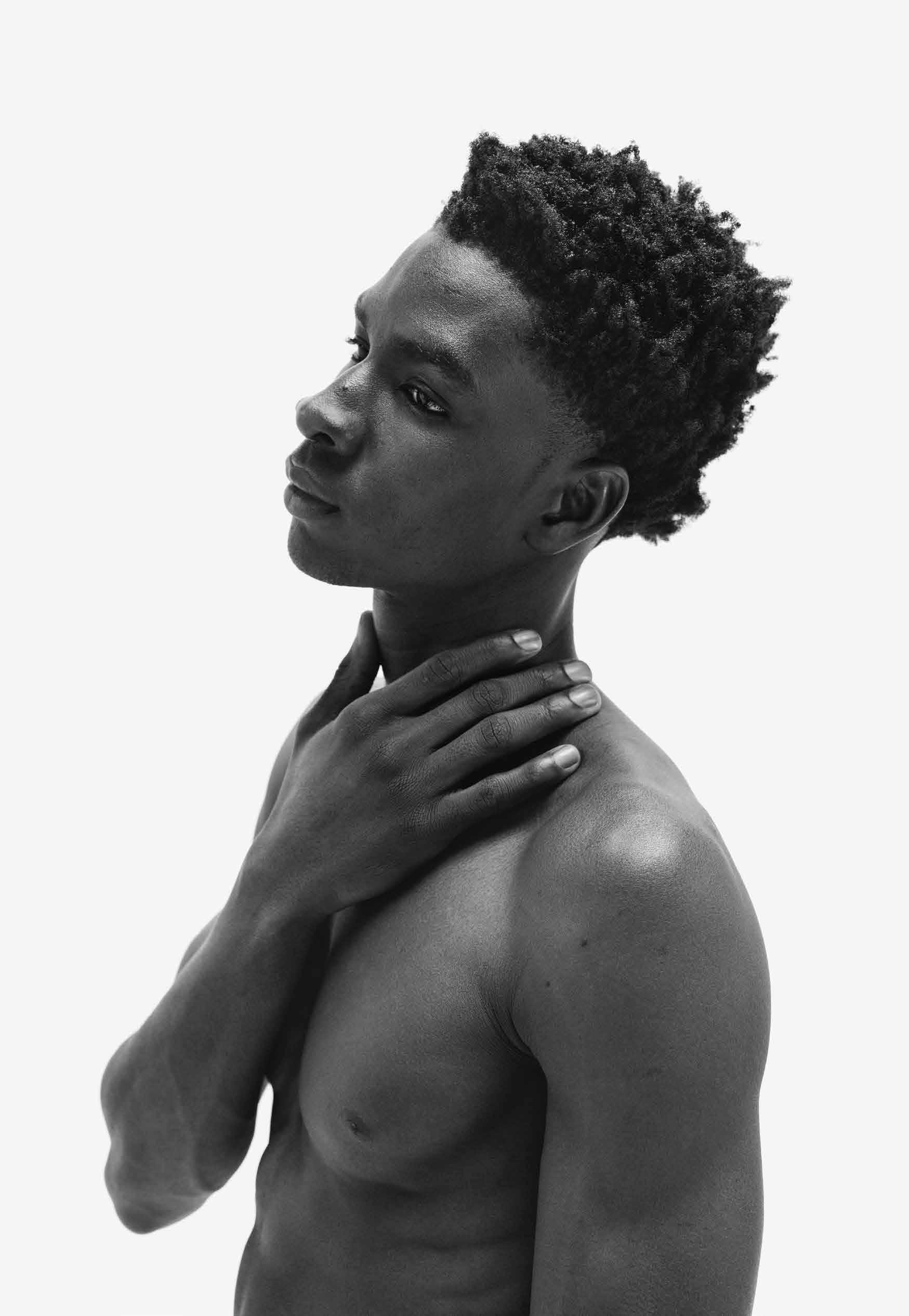

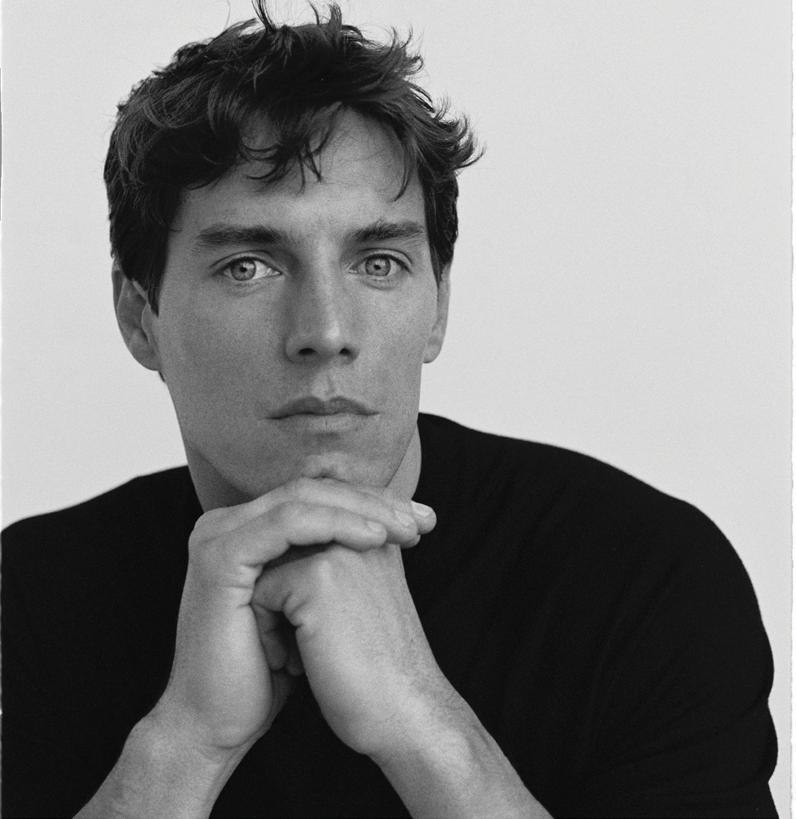

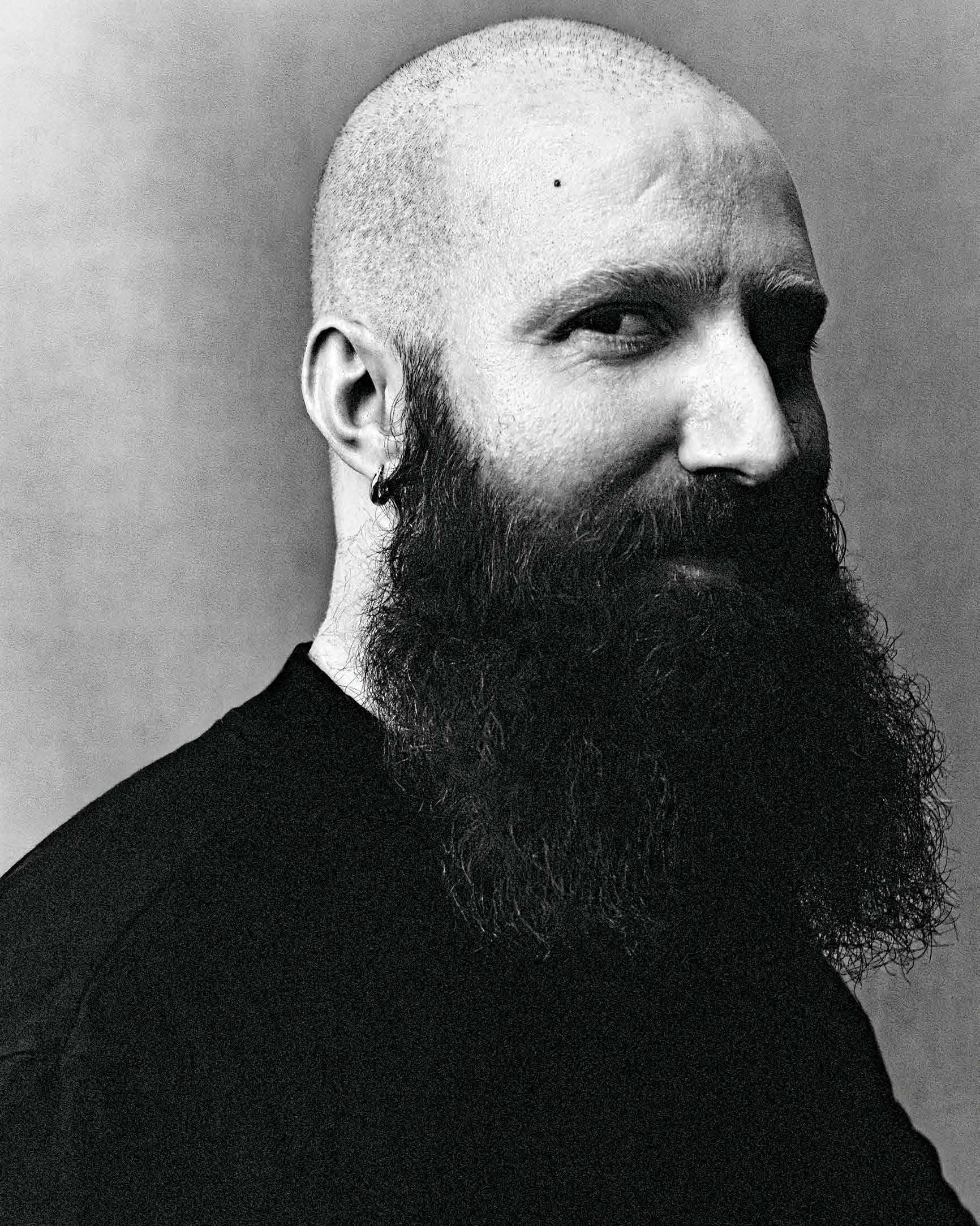

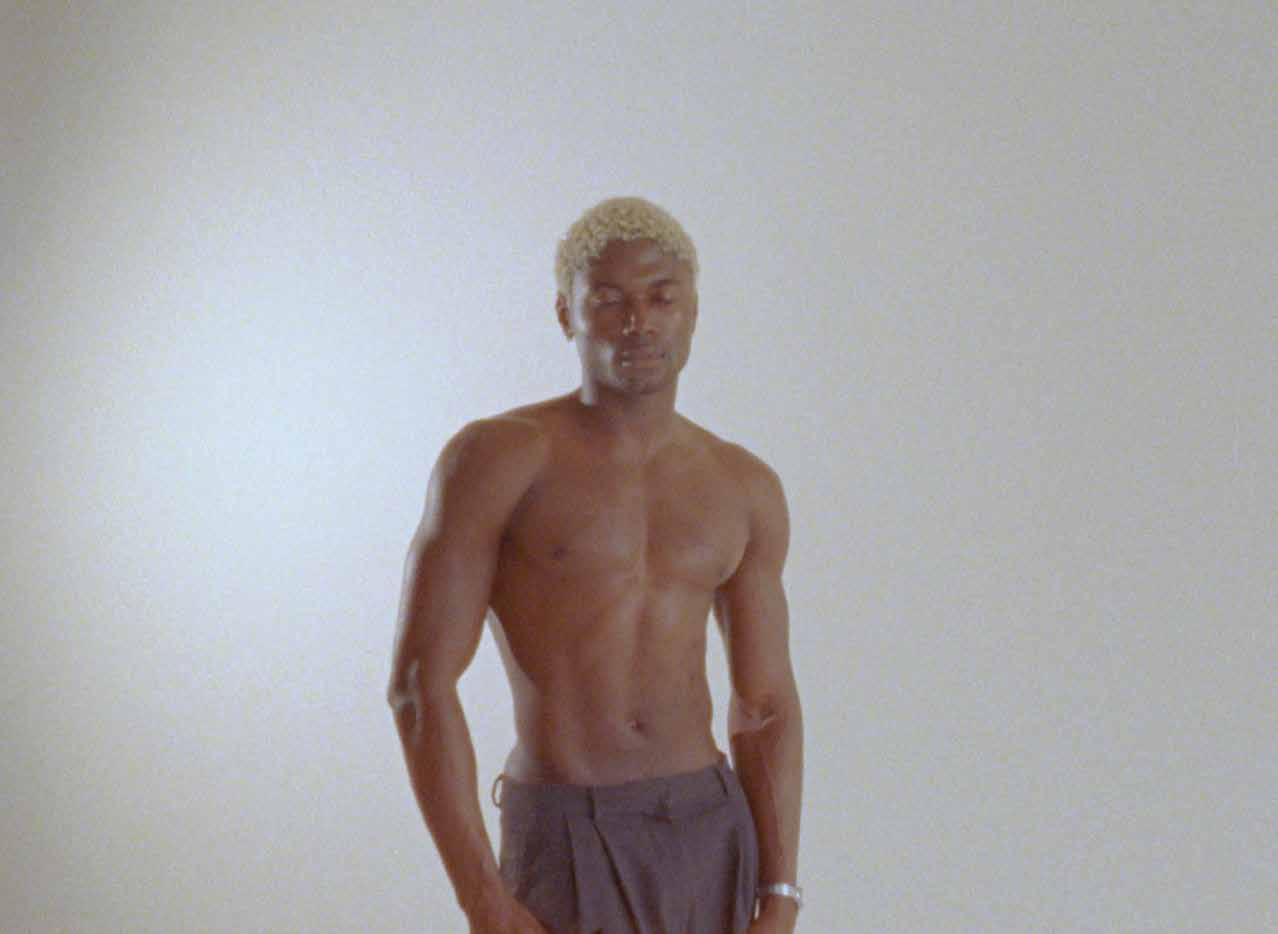

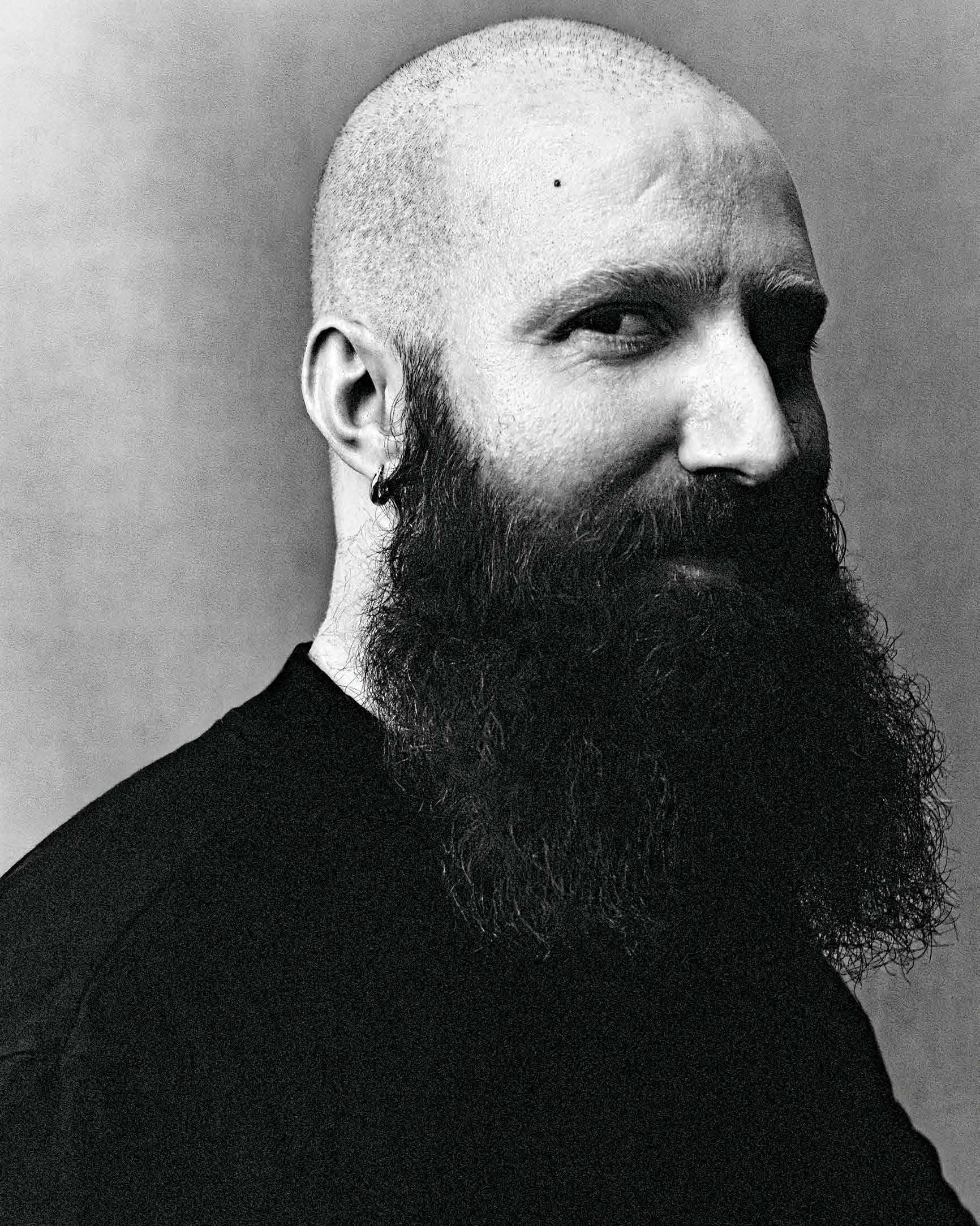

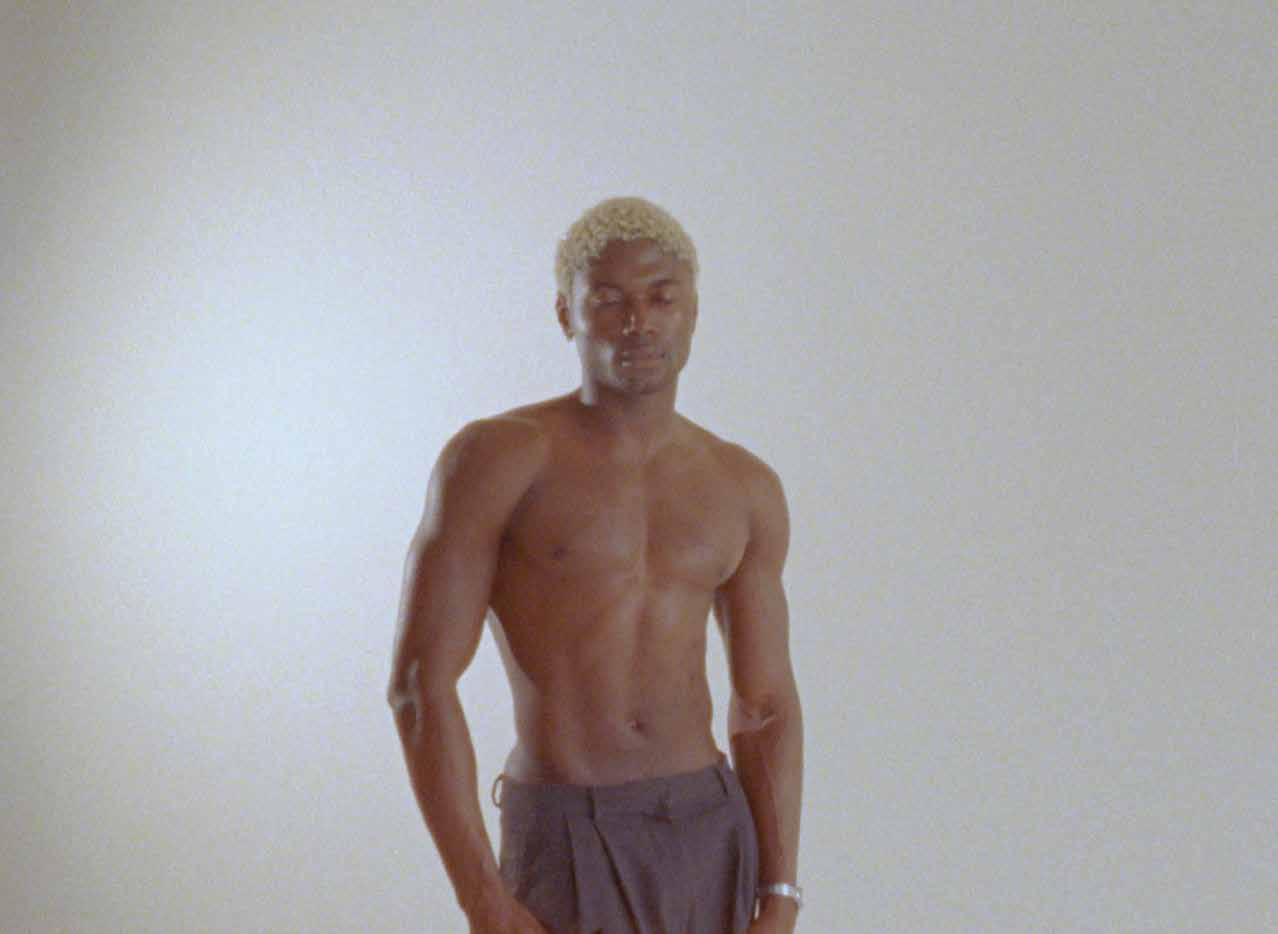

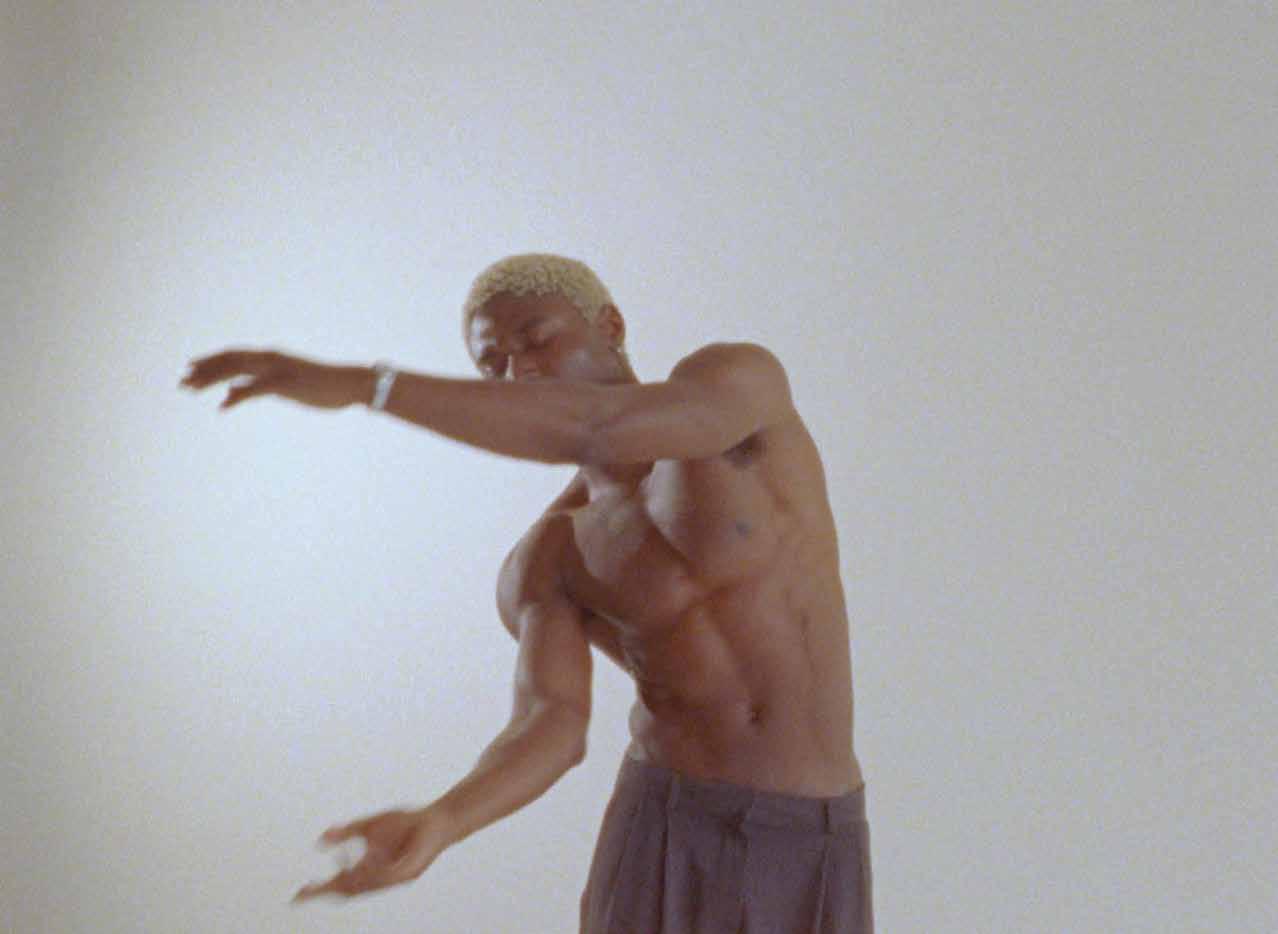

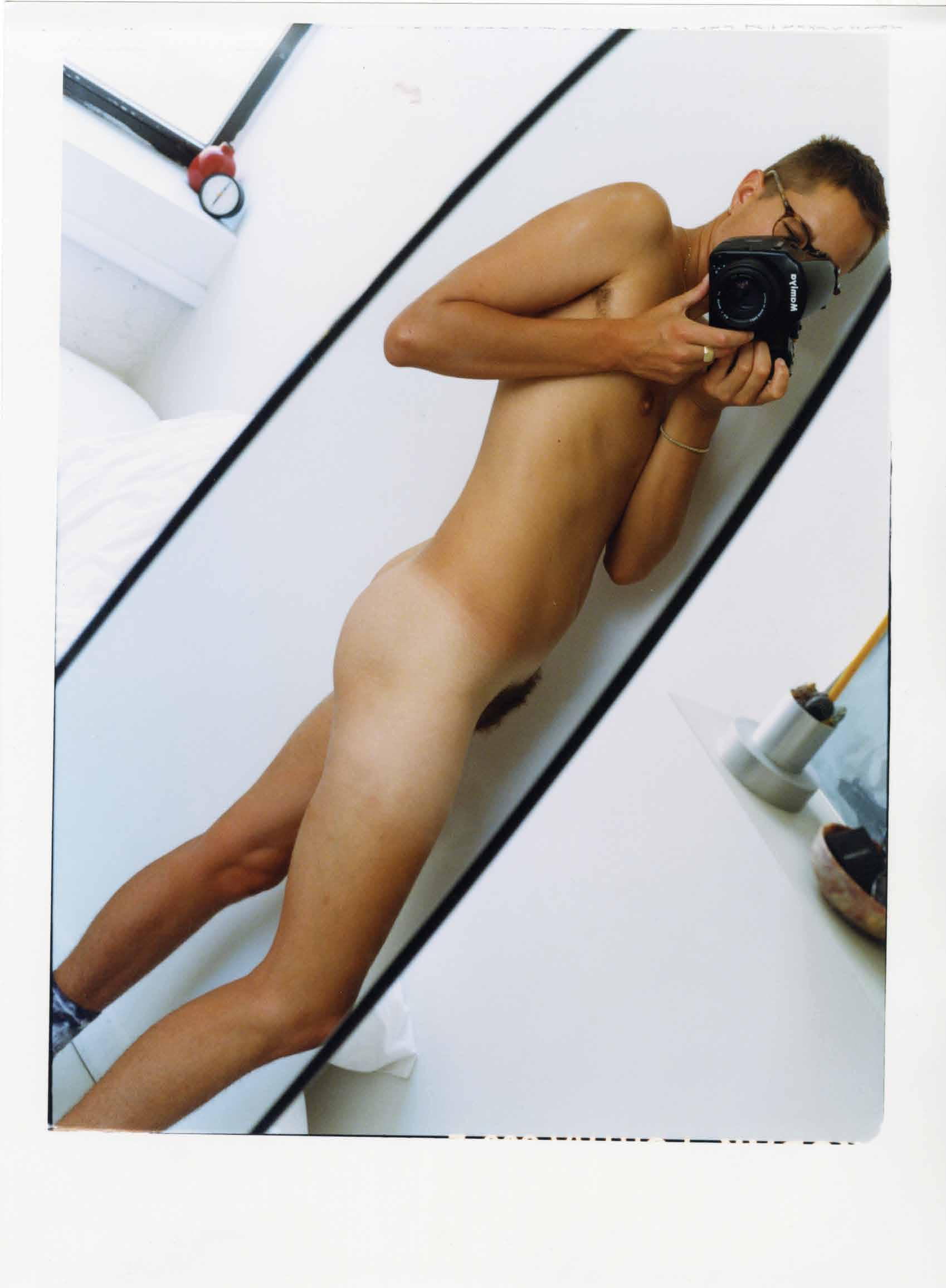

Jack Pierson, the Massachusetts-born artist known for his unflinchingly intimate male portraits, enters fresh territory with a new job title and a photographic challenge.

200

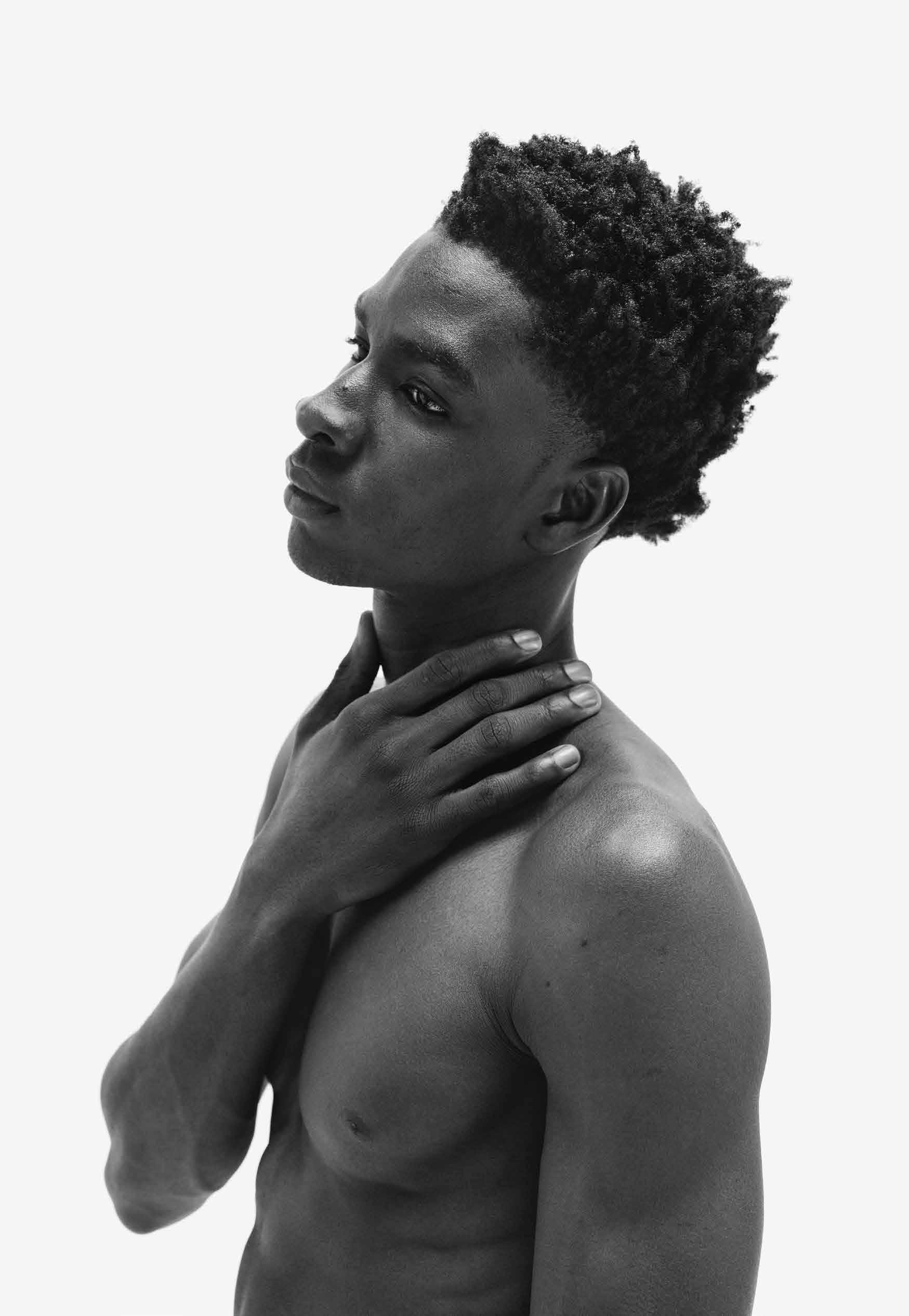

A NEW YORK MOVEMENT

Dance Reflections, the nascent festival supported by Van Cleef & Arpels, is bringing a coterie of world-class performers to the city this fall.

48 culturedmag.com

September 2023

de Piante’s West Village townhouse. Photography by Björn Wallander.

GÜNSELI YALCINKAYA Writer

Online communities are Günseli Yalcinkaya’s obsession—and her profession. The Londonbased writer, researcher, and cultural critic is the features editor at Dazed and the host of Logged On, a monthly podcast series exploring all things Internet culture. For this issue, Yalcinkaya profiled the designer behind one of London’s buzziest fashion labels. “Standing Ground is futuristic and mystical, unique and alien,” she says. “Its conceptual backbone— unusual silhouettes and craftsmanship—is exactly what makes Michael Stewart one of the most exciting emerging talents out there.”

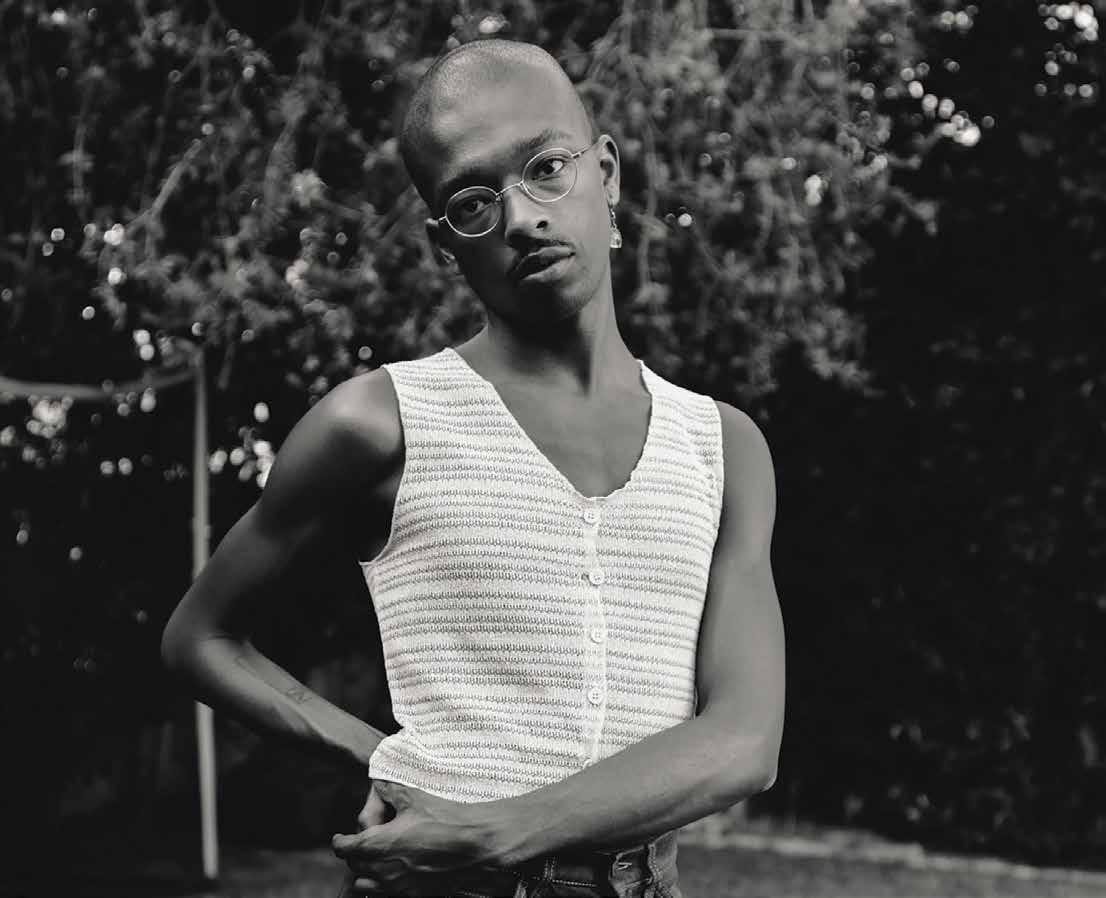

MYLES LOFTIN Photographer

Myles Loftin knows the power of visibility. The Brooklyn-based artist, storyteller, and creative collaborator is driven by a desire to show up for under- and misrepresented groups, and his work is characterized by its intimacy and a playful sensibility that unites viewer and subject. “It was an honor to photograph Mickalene Thomas for this issue,” he says of his shoot with the artist in celebration of her new namesake scholarship at the Yale School of Art. “She’s incredibly talented and influential. We shot this feature at the home of collectors Bernard Lumpkin and Carmine Boccuzzi, where a piece of Thomas’s work— from her MFA thesis—hangs on the wall.”

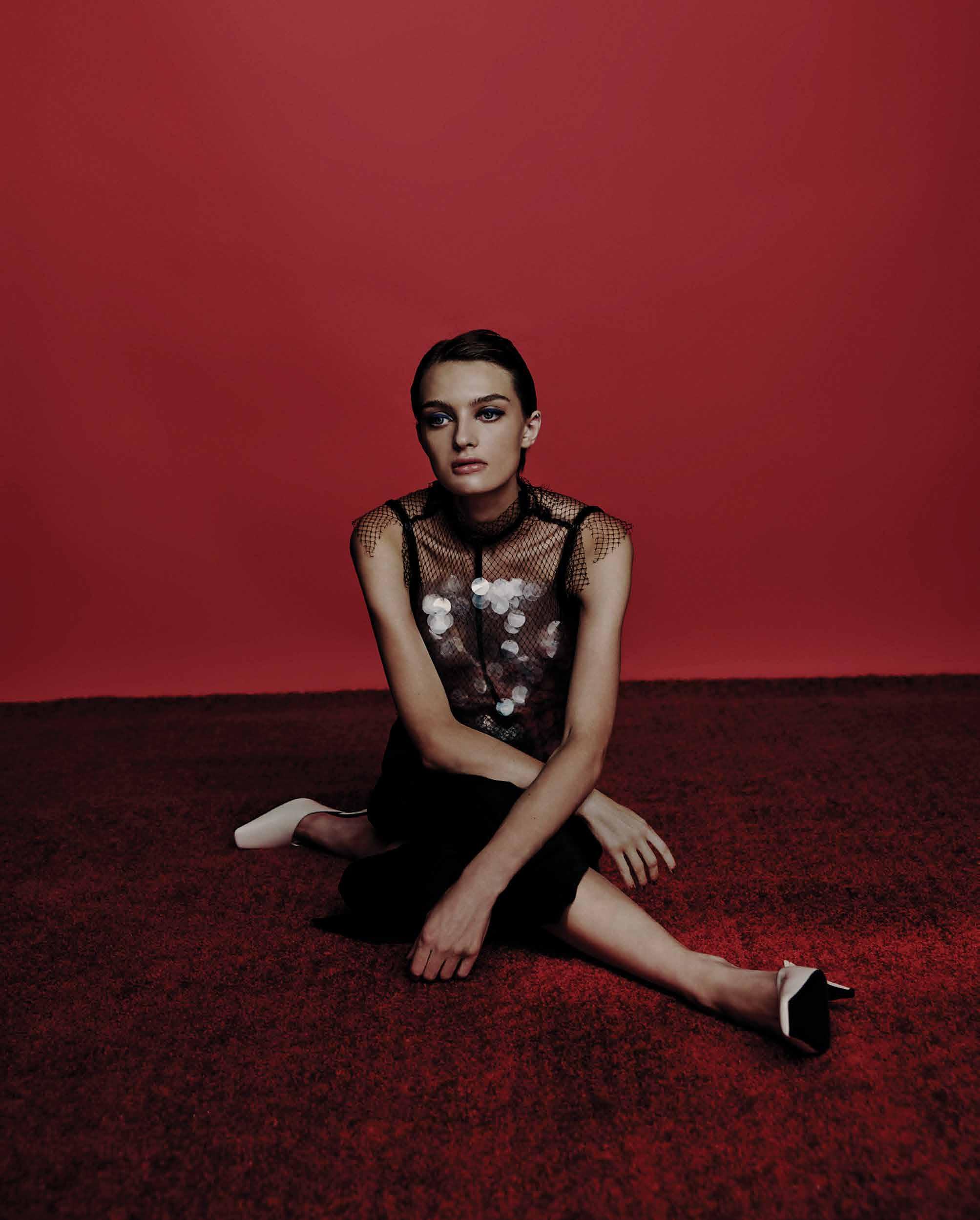

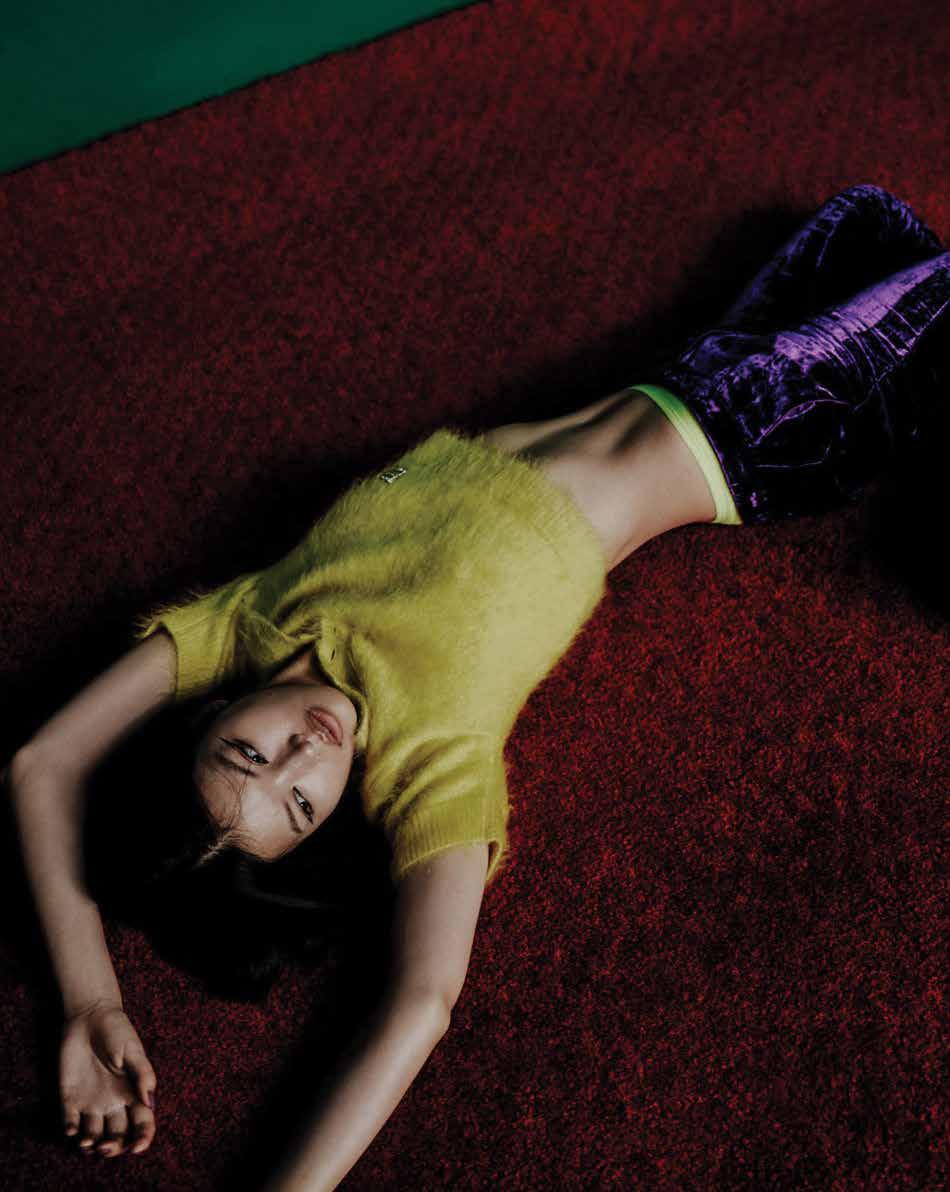

DREW JARRETT Photographer

Drew Jarrett’s creative philosophy, which embraces the imperfections of analog and takes a unique approach to light, has led to sustained demand for his work in the fashion and fine art spheres. The U.K.-born photographer, now living in upstate New York, has been taking pictures professionally for over 25 years, and his extensive oeuvre has been exhibited in London, New York, and Tokyo. Jarrett has also published three books: 1994, Guinevere, and Jungle Dreams. Jarrett shot one of two cover features for this issue—a bold red color study in partnership with Gucci. “I reference painters, artists, and music and then turn it into my vision. I grab a color, a shape, and textures,” explains the photographer.

“The whole team on this project was brilliant.”

50 culturedmag.com

CONTRIBUTORS

GÜNSELI YALCINKAYA, IMAGE COURTESY OF GÜNSELI YALCINKAYA; DREW JARRETT, IMAGE COURTESY OF DREW JARRETT; MYLES LOFTIN, PHOTOGRAPHY BY DENZEL GOLATT.

CONTRIBUTORS

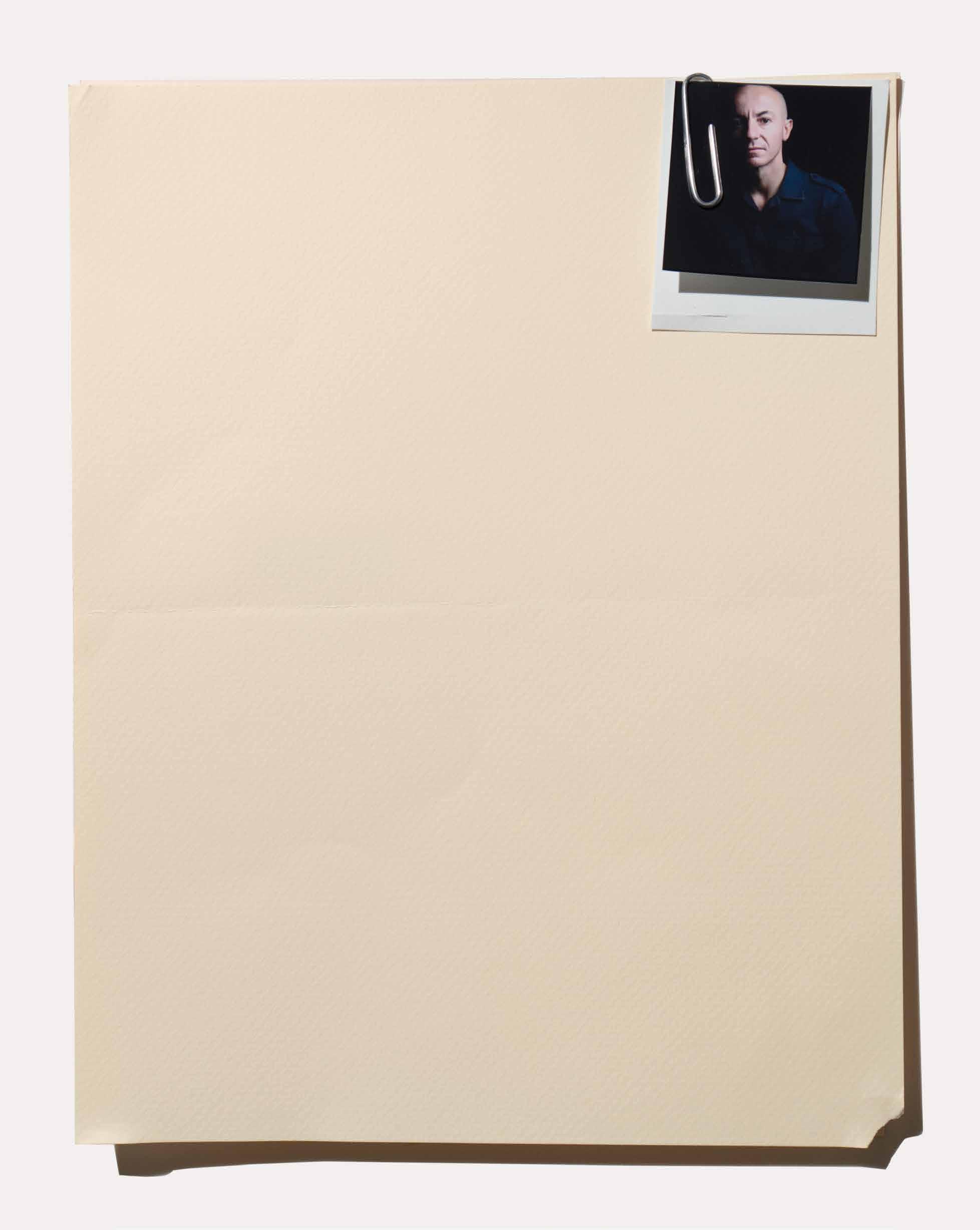

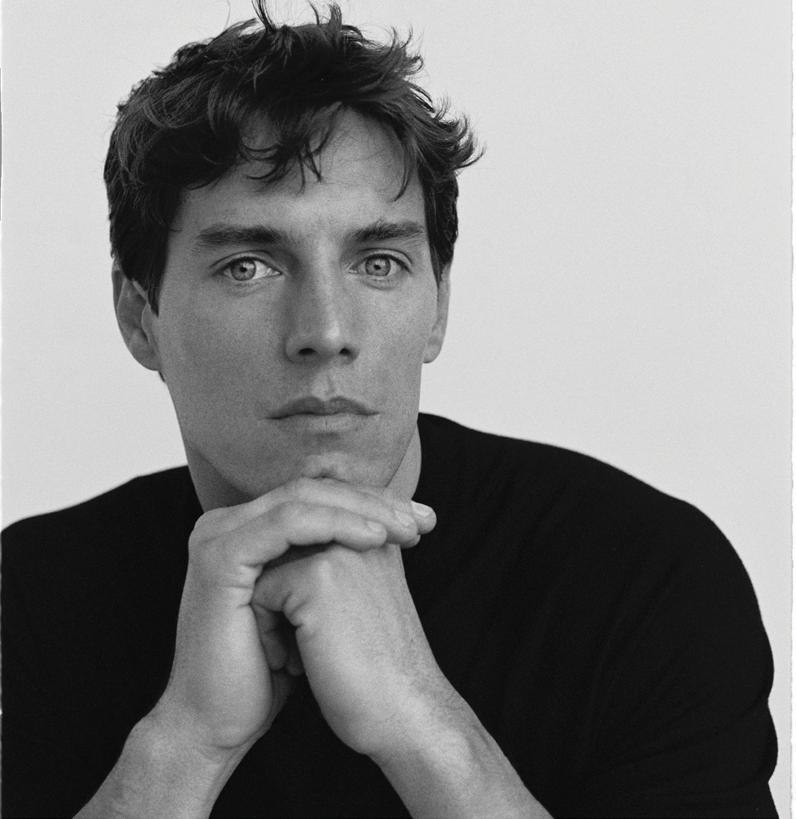

Jack Pierson came to New York via Massachusetts, and works across the mediums of photography, collage, sculptural assemblage, and installation. The artist made a recent move to Lisson Gallery, and will be staging his first show there, titled “Pomegranates,” in New York this fall. For this issue, Pierson contributed a number of photographs that reveal his unique interpretation of the nude form. “I just wanna show what I’ve been up to [and] look at what could be next,” says Pierson of the show. “It’s all about looking. The whole show will be a labyrinth, an exhibition where you wander around in big spaces and little spaces and find the next thing to look at.”

LYNETTE NYLANDER Writer

Lynette Nylander lives at the intersection of fashion and youth culture. The writer, editor, and creative consultant is currently the editorial director of Dazed. She has also held senior leadership positions at the likes of Alexander Wang and Pat McGrath Labs, and has consulted for brands including Gucci, Calvin Klein, and Nike. “I shared some tips on how I sartorially approach my day-to-day, which I probably contradict on a daily basis,” the London-born, New York–based creative says of her contribution to this issue. “I’m very much a ‘do as I say, not as I do’ type of gal!”

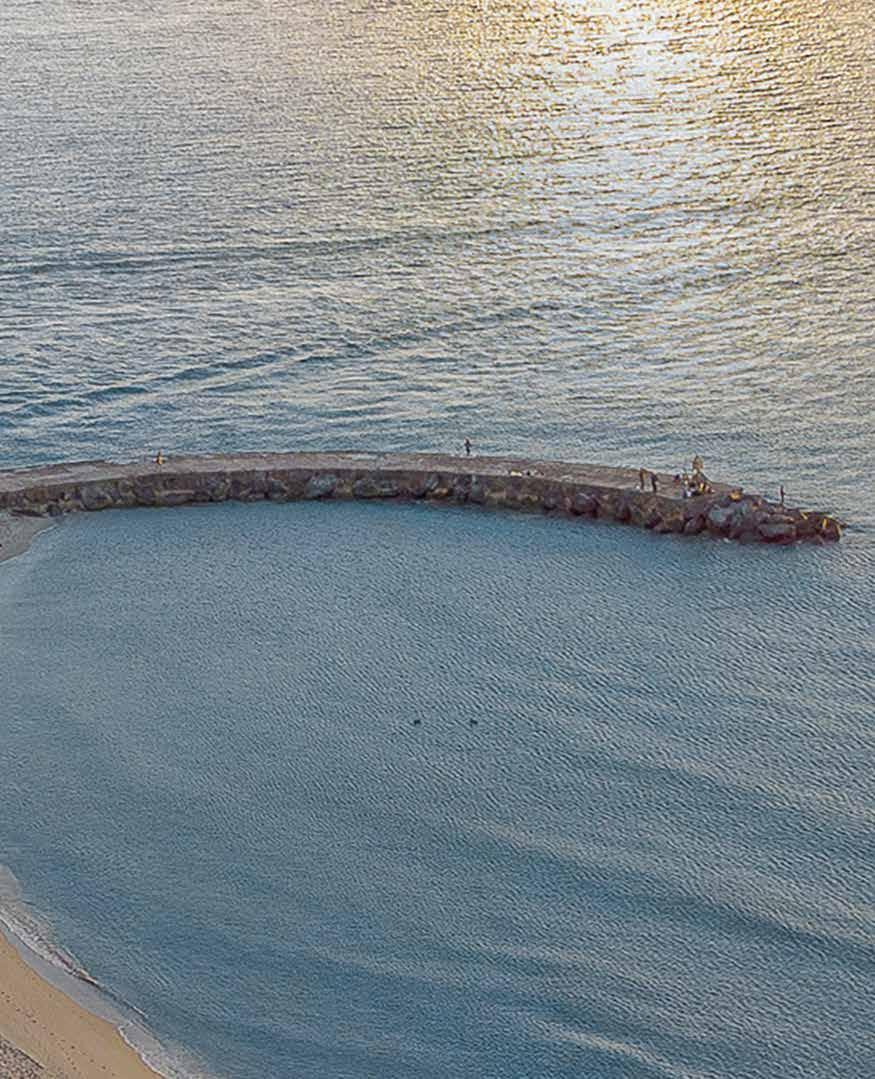

MARCOS FECCHINO Creative Producer

While growing up in Buenos Aires, Marcos Fecchino discovered his love for image-making. This passion inspired the young producer and creative director to move from Argentina to New York, where he opened his own agency, MF Studio. After more than a decade in the industry, Fecchino has contributed to the likes of Vogue, Vogue Italia, Man about Town, Harper’s Bazaar, and Numéro. Fecchino produced the Hari Nef cover shoot for this issue, which took place on a rainy day on Fire Island.

SUSAN YUNG Writer

Susan Yung covers dance, art, literature, and culture for publications including the Brooklyn Rail, Dance Magazine, and Chronogram. After working as the associate editorial director at the Brooklyn Academy of Music for several years, she coedited the book BAM: Next Wave Festival, and was associate editor of BAM: The Complete Works. For this issue, the Hudson Valley–based writer turned her attention to the Van Cleef & Arpels–supported Dance Reflections festival, exploring its impact on the New York dance community. “Delving into the work of these varied artists reminded me of all the wild creativity in dance around the world,” she notes. “I hope that a festival like Dance Reflections signifies the strong return of the arts in New York—on a collaborative, citywide scale.”

FECCHINO, IMAGE

OF

SUSAN YUNG, IMAGE COURTESY OF SUSAN

JACK PIERSON, IMAGE COURTESY OF JACK PIERSON; LYNETTE NYLANDER, PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARGOT BOWMAN; MARCOS

COURTESY

MARCOS FECCHINO;

YUNG.

36 culturedmag.com

JACK PIERSON Artist

52 culturedmag.com

LEICA M11 MONOCHROM

Street photography in New York with Andre D. Wagner

“I can point this camera at really anything and turn the moment into something inspiring for others. It’s just a beautiful and powerful thing.” Discover their story.

Boston | Los Angeles | Miami | New York | San Francisco | Seattle | Washington, D.C.

NICOLAS PARTY Artist

The Swiss artist—known for his familiar yet unsettling landscapes, portraits, and still lifes—has earned a reputation for challenging the conventions of representational painting. Nicolas Party’s work has been exhibited around the world, most recently with a solo show at Hauser & Wirth New York. His works are primarily created in soft pastel, an idiosyncratic choice of medium in the 21st century that allows for exceptional degrees of intensity and fluidity in his depictions of natural and man-made objects. For this issue, Party offered his own bold interpretation of CULTURED’s signature cover logo, and sat down with writer Katie White for a conversation about his latest exhibition.

CONTRIBUTORS

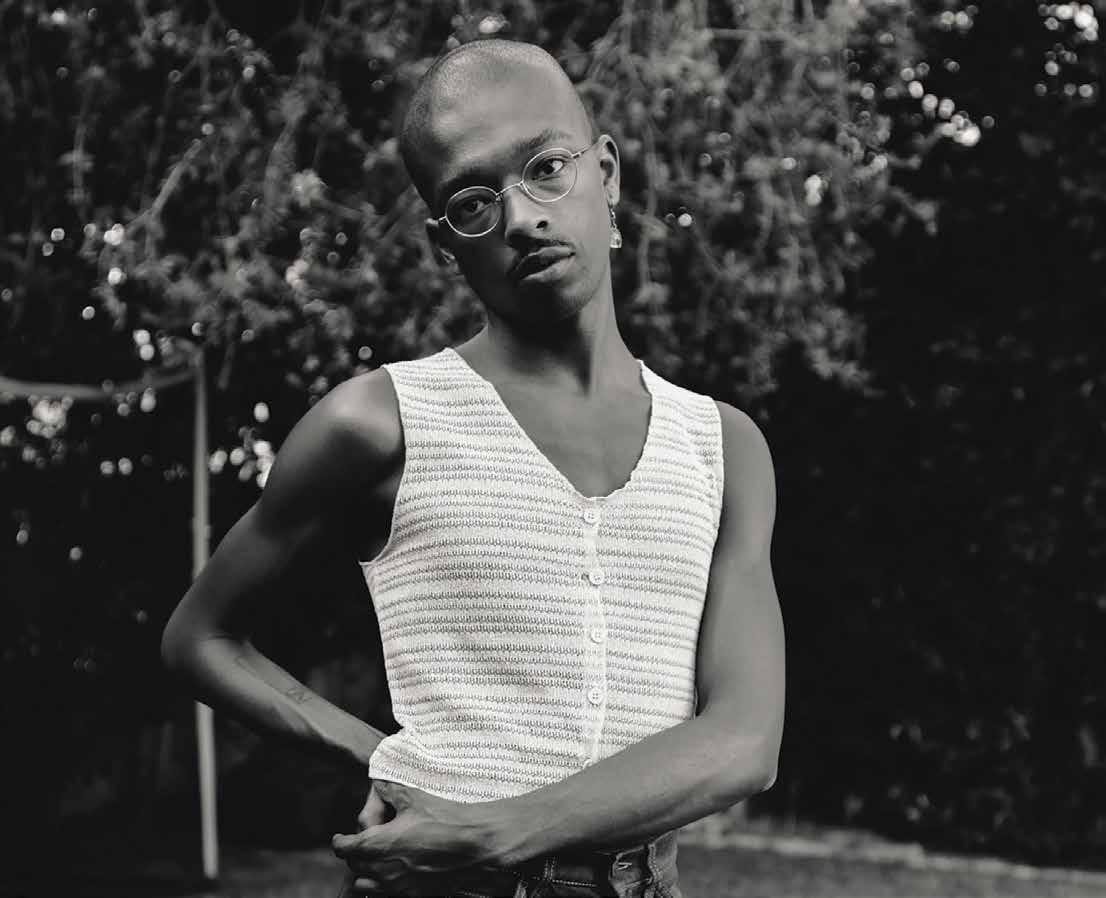

NIC BURDEKIN and LUCAS LEFLER Creative Directors

New York–based Nic Burdekin and Lucas Lefler are the cofounders of Image, a creative studio specializing in advertising and editorial at the intersection of culture and fashion. For this issue, Burdekin and Lefler directed a feature on the vitality of New York’s creative ecosystems. “We focused this shoot on considered portraits of artists in the city who are cultivating their own communities through their work,” they explain. As a team and individually, the duo have collaborated with brands and publications including Prada, Moncler, and Vogue, and have worked with talent including Bella Hadid and Doja Cat.

Writer

Ottessa Moshfegh is a Los Angeles–based fiction writer from New England. Eileen, her first novel, was shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Man Booker Prize, and won the PEN/Hemingway Award for debut fiction. My Year of Rest and Relaxation and Death in Her Hands, her second and third novels, were New York Times bestsellers. For this issue, she shared her rules for living a beautiful life. “Giving advice is always a personal reflection of the advice-giver,” she explains, “but I didn’t realize this until I was asked to write down some advice about how to live. That’s what I love about writing: When my thoughts and feelings are externalized into language, I can see myself more clearly.”

WILLY CHAVARRIA Fashion Designer

Willy Chavarria is a 2021 CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund recipient and 2022 Cooper Hewitt National Design Award winner. The Mexican American designer’s eponymous brand takes inspiration from recurring motifs in Chavarria’s community and the magic that he finds in the streets of New York. In this issue, Chavarria shares a glimpse of his adopted home: “I was so happy to work with my good friend, the incredibly talented photographer Stefan Ruiz, on this special feature,” he says. “I am excited to share these beautiful portraits of the people and places closest to me through Stefan’s unique and visionary lens.”

OTTESSA MOSHFEGH

NICOLAS PARTY, PHOTOGRAPHY BY STEVE BENISTY; LUCAS LEFLER AND NIC BURDEKIN, IMAGE COURTESY OF LUCAS LEFLER AND NIC BURDEKIN; OTTESSA MOSHFEGH, PHOTOGRAPHY BY JAKE BELCHER; WILLY CHAVARRIA, PHOTOGRAPHY BY STEFAN RUIZ.

OTTESSA MOSHFEGH

NICOLAS PARTY, PHOTOGRAPHY BY STEVE BENISTY; LUCAS LEFLER AND NIC BURDEKIN, IMAGE COURTESY OF LUCAS LEFLER AND NIC BURDEKIN; OTTESSA MOSHFEGH, PHOTOGRAPHY BY JAKE BELCHER; WILLY CHAVARRIA, PHOTOGRAPHY BY STEFAN RUIZ.

54 culturedmag.com

Founder | Editor-in-Chief

SARAH G. HARRELSON

Executive Editor

MARA VEITCH

Senior Creative Producer

REBECCA AARON

Casting Director

TOM MACKLIN

Associate Editor

ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

Editorial Assistant

SOPHIE LEE

Copy Editor

EVELINE CHAO

Junior Art Director

HANNAH TACHER

Contributing Fashion Directors

ALEXANDRA CRONAN, KATE FOLEY

Editor-at-Large

KAT HERRIMAN

New York Contributing Arts Editor

JACOBA URIST

Podcast Editor

SIENNA FEKETE

Contributing Editors

JULIA HALPERIN, LILY KWONG, MARTINE SYMS, FRANKLIN

SIRMANS, SARAH ARISON, DOUG MEYER, CASEY FREMONT, MICHAEL REYNOLDS, DOMINIQUE CLAYTON

Chief Revenue Officer

CARL KIESEL

Publisher LORI WARRINER

Italian Representative—Design

CARLO FIORUCCI

Interns

LAINE ALLISON

ISABELLA BARADARAN

CAROLINE BOMBACK

MARIA CLARA COBO

ELIZABETH COHAN

SOPHIE COLLONGETTE

MARIANA DE JESUS SZENDREY

AMELIA STONE

Prepress/Print Production

PETE JACATY

Senior Photo Retoucher

BERT MOO-YOUNG

CULTURED Magazine 2341 Michigan Ave Santa Monica, California 90404

TO SUBSCRIBE , visit culturedmag.com. FOR ADVERTISING information, please email info@culturedmag.com. Follow us on INSTAGRAM @cultured_mag.

ISSN 2638-7611

56 culturedmag.com

LETTER EDITOR from the

THE CREATIVE AND CULTURAL FORCES featured in this issue, our first September issue dedicated to the crossover between fashion and art, are technicians and craftspeople at their core. They are motivated by that big, unwieldy ideal we call art—but even as they pursue material and narrative sophistication, they leave space for the plain facts of life in a messy world to seep into the work.

As Coco Romack writes in the introduction to our roundup of breakout designers, the runway, much like the museum, the silver screen, and the still image, “can be a petri dish for larger social reckonings.” Our cover star, Hari Nef, is perhaps one of the best examples of this. A consummate actor, the young icon’s work eschews explicit political critique in favor of political realism, an attitude embraced by the extraordinary photographic duo Torso Solutions. In their first collaboration with CULTURED, the pair captured Hari, their former intern, in all her ethereal complexity.

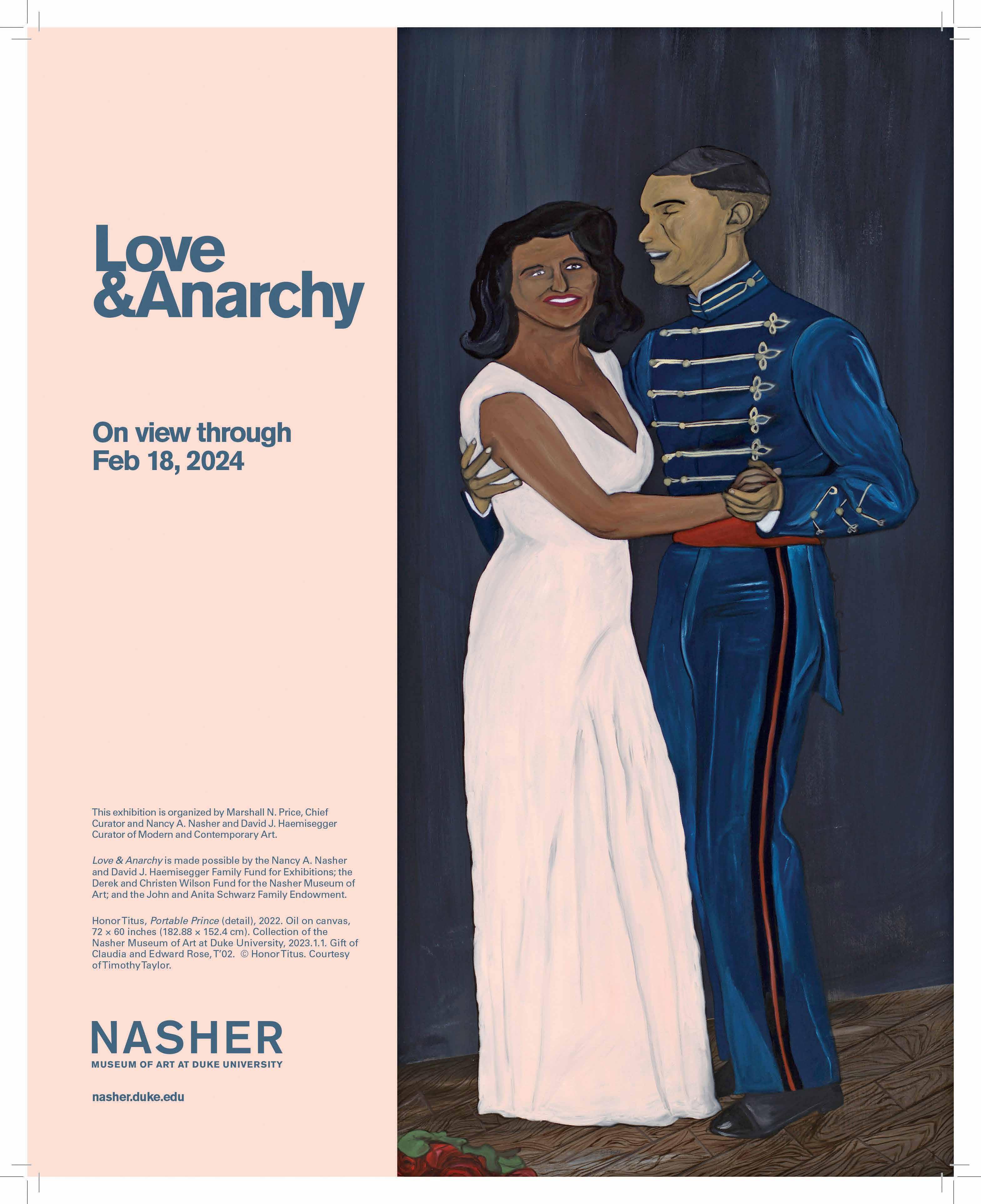

If Diana Vreeland—whose pearls of wisdom inspired our portfolio of advice for a life well-lived—taught us anything, it’s that more is always more. In that spirit, we are honored to present a second cover for this issue: photographer Drew Jarrett’s sumptuous color study featuring the upand-coming model Isha Senghore clad head-to-toe in Gucci. This cover is embellished with a psychedelic interpretation of our logo, courtesy of Swiss artist Nicolas Party, whose first solo exhibition at Hauser & Wirth opens in New York this fall.

During our interview earlier this month, the artist and photographer Jack Pierson shared something deeply touching with me that has become something of a touchstone, or talisman, for the issue: “I still believe in the power of an image, especially a printed image. Part of what makes me work to stay relevant as an

artist is the desire to have my work printed in magazines, because there is always that possibility of somebody ripping out that page and keeping it.” Jack’s words speak to the democratic value of publishing, and to the epiphanic encounters we can only have with printed matter. This is something that the 11 young image-makers featured in our inaugural Young Photographers list know well. While their peers are content with the endless scroll of digital imagery, each of these artists is driven, at all costs, to make tangible things. Rirkrit Tiravanija, Judy Chicago, and Kelly Akashi, three artists profiled in the issue, operate at the edges of material to craft work that seems to disappear, or is barely even there to begin with. In their formidable slate of upcoming exhibitions, we get the sense that the work on view is speaking to us directly, that its physical form is a conduit for a message from artist to viewer.

We hope you like the issue, and maybe even rip out a few pages.

Sarah G. Harrelson Founder and Editor-in-Chief @sarahgharrelson

Follow us | @cultured_mag

58 culturedmag.com

THE EVOLUTION OF HARI NEF

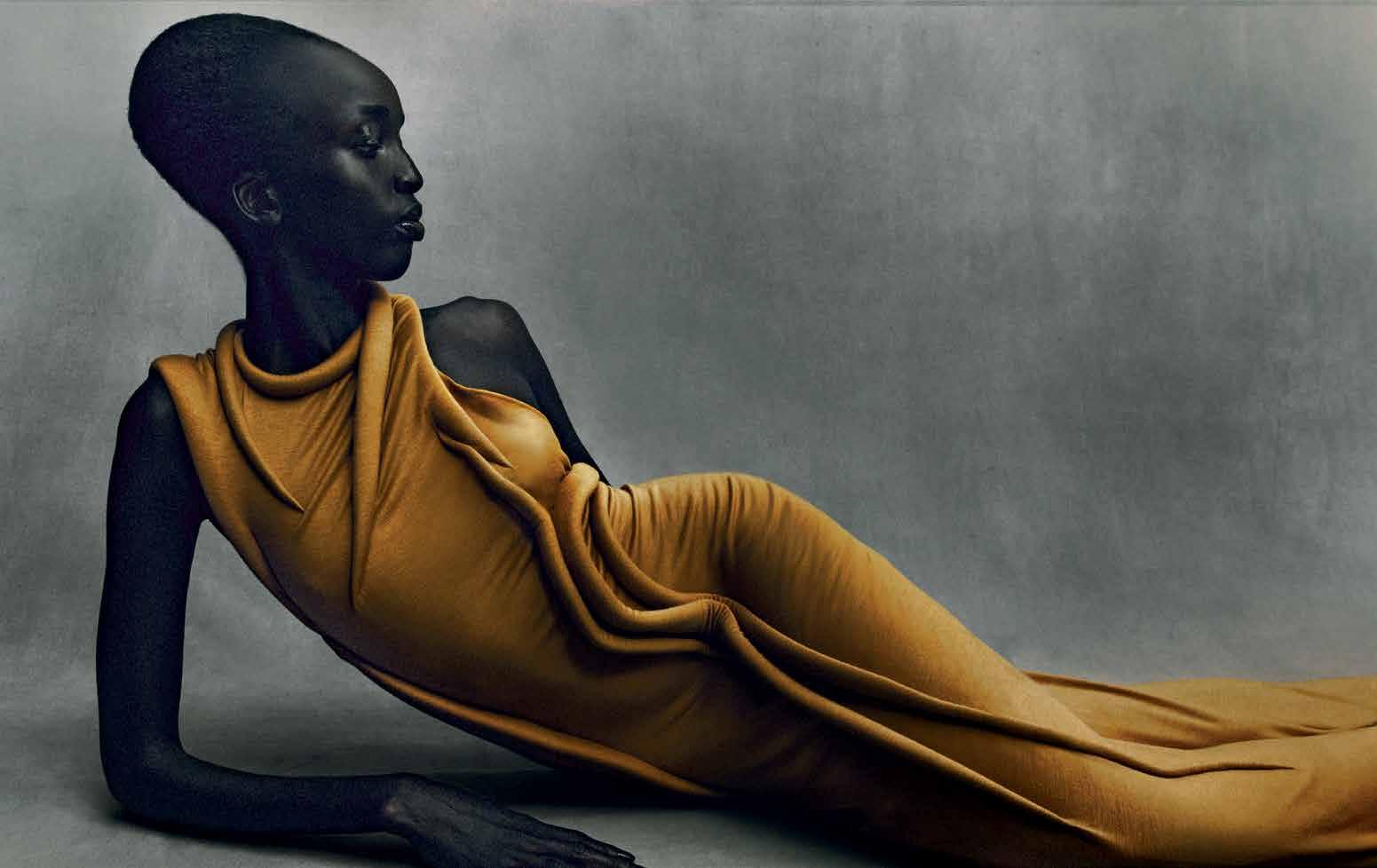

HARI NEF photographed on Fire Island wearing Rick Owens

Photography by Torso Solutions.

Styling by Malcolm Mammone

Produced by Marcos Fecchino.

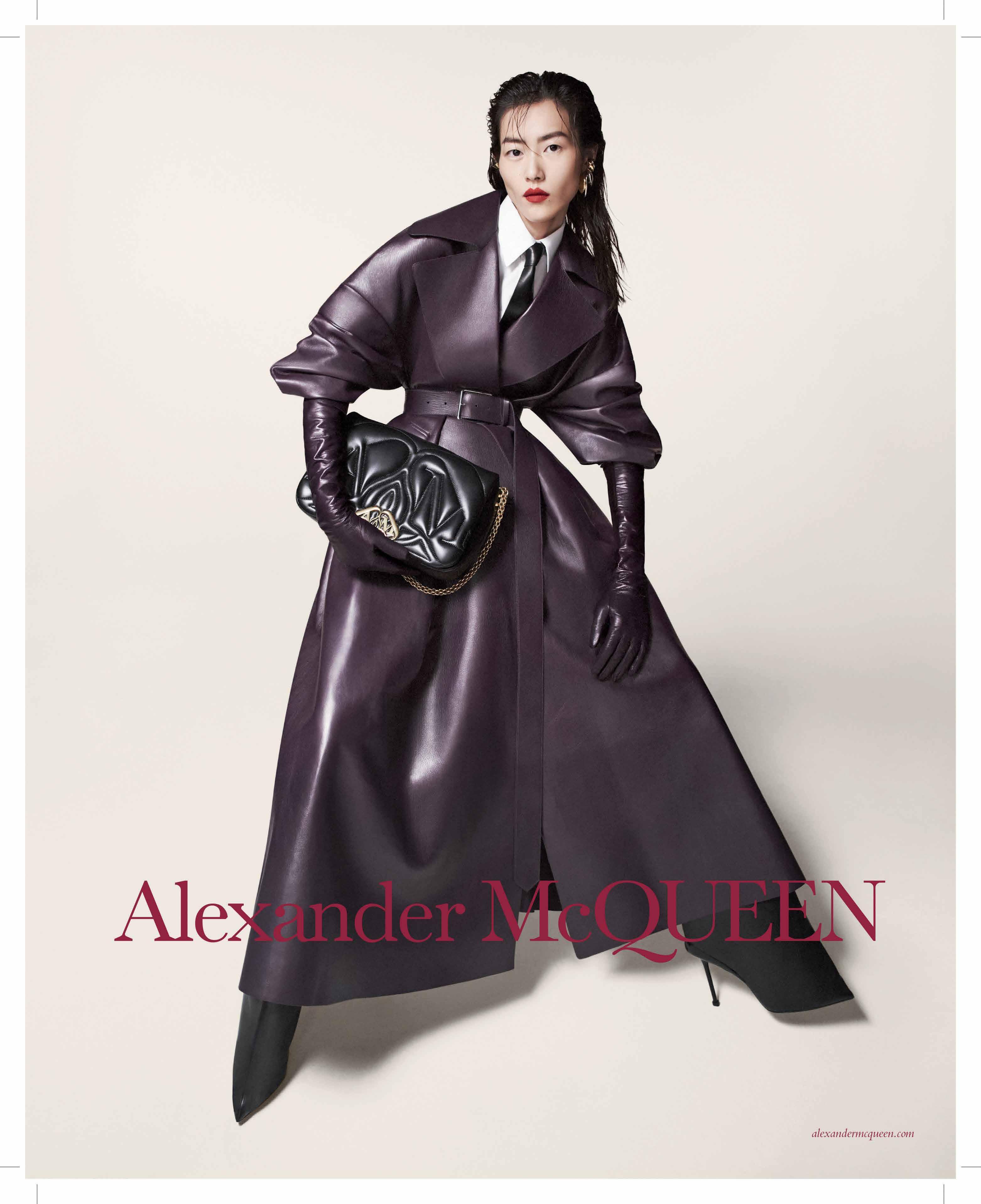

ISHA SENGHORE at IMG Models wearing Gucci

Photography by Drew Jarrett Logo design by Nicolas Party

KELLY

A RESURGENCE IN RED

SARAH HARRELSON AND ARTIST NAIRY BAGHRAMIAN AT THE CULTURED, ASPEN ART MUSEUM, AND TATA HARPER LUNCH TO KICK OFF ARTCRUSH.

AKASHI J. SMITH-CAMERON WILLY CHAVARRIA JUDY CHICAGO ELLA EMHOFF HODAKOVA OTTESSA MOSHFEGH HARI NEF

RULES TO LIVE BY

There are few fashion critics more infamous than DIANA VREELAND. Before her tenures at Vogue and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the legendary iconoclast launched her consummate advice column,

“WHY DON’T YOU,”

at Harper’s Bazaar in 1936. It ran for decades until her resignation, serving as a sumptuous call to action that was refreshing in its preposterousness and startling in its particularity. She endorsed gourmandise (“WEAR FRUIT HATS? CURRANTS? CHERRIES?”), fashionable ambidexterity (“TIE BLACK TULLE BOWS ON YOUR WRISTS?”), and baroque excess (“RINSE YOUR BLOND CHILD’S HAIR IN DEAD CHAMPAGNE TO KEEP IT GOLD, AS THEY DO IN FRANCE?”). Vreeland relished in the daily trifles and contradictions that define style, inviting her readers to forsake conformity in favor of spontaneity.

In her honor, CULTURED asked six sartorial voices to share their advice for a life well and luxuriously lived.

60 culturedmag.com

RULES TO LIVE BY LYNETTE NYLANDER

ALWAYS UNDERSTAND THAT WHAT IS FOR YOU WON’T GO BY YOU.

This has served me well professionally, personally, and romantically. It helps soothe the wound of not getting a gig you wanted, or when the vintage piece you went back for the next day was gone.

ALWAYS DATE THE FUTURE AND MARRY THE PRESENT.

Live in the freaking moment. Marry the hell out of today, and have a flirty relationship with what comes next. Treat the future like a casual fling, and don’t be dictated by it. What you know is that today is right here, right now.

ALWAYS BELIEVE IN THE POWER OF POOR TASTE!

I don’t want anything too glitzy with no chaser. I consider myself a lover of the dichotomy of high and low. Vintage Saint Laurent dress to visit the dosa guy in Washington Square Park—perfect! Monkey Bar, then Drag Race reruns after— ideal! My new one: I dream of de Gournay wallpaper to frame the thrifted photo I got for no money.

Lynette Nylander grew up with a mother who ironed her underwear. “She took immense pride in the way she put herself together,” says the London-born, New York–based fashion critic. “She thought it was important that I understood that as well.” For Nylander, who served as the creative and editorial director-at-large of CR Fashion Book and is currently the editorial director at Dazed, good style lies in its contradictions—a little high, a little low. Something delicate but “a little fucked-up.” And planning an outfit begins with a single piece. “I ask myself, New thing? Old thing? Tailored thing?” Armed with the answer, Nylander ventures into her closet, a former “apartment-engulfing fungus,” which she has since wrestled into a state of organized chaos. “The results can vary, but the beauty is that it all comes back to different parts of myself that I’m really comfortable with,” she says. “In the end, it’s the swag that sets a look off, never the brand name.”

NEVER SKIP COCKTAIL HOUR.

Do this as formally as you can. Bar coaster, the appropriate glass for your drink, and lots of chatter about the day’s comings and goings. This, I am sure, will add years to your life.

NEVER BE AFRAID TO DO THINGS ALONE.

There’s nothing sadder than not being able to be in your own company. Meals, vacations, theater shows, cinema trips. Know yourself, goddamnit.

NEVER SLEEP ON BAD SHEETS. CRIMINAL!

62 culturedmag.com

PHOTOGRAPHY BY SOPHIE FABBRI

RULES TO LIVE BY

J. SMITH-CAMERON

NEVER WEAR UNCOMFORTABLE SHOES

No matter how dazzling they are, you will look like a fool if you’re limping or stumbling. Once, Martha Raddatz had to hide my Manolo Blahniks behind the White House drapes while I padded around the Bidens’ Christmas party in flip-flops!

ALWAYS GET 8-PLUS HOURS OF SLEEP.

When I was a child, I hated to go to bed because FOMO. I was an insomniac from 25, when I got burglarized three times in a row, but a doctor figured out the right pill for me. Isn’t modern medicine a miracle?

ALWAYS MAKE SURE TO VOTE.

It is the shiniest, most influential right we have! Don’t let the bad guys win! Vote them out! And make every single one of your friends do it, too.

ALWAYS TRY NEW THINGS.

You may be cursing yourself at first, but I guarantee new adventures broaden your horizons and make you a more interesting person.

NEVER BE RUDE TO STRANGERS.

If it’s someone you know quite well—say, your landlord or Kieran Culkin— rudeness can be warranted, especially if handled with style and wit. But for goodness’ sake, be kind to the cashier, the lady who lives downstairs, the cabbie. Be polite with colleagues. They won’t catch on that you’re insulting them if you have lovely manners.

NEVER GET ON AN AIRPLANE WITHOUT A SWEATER.

AND PREFERABLY A LAP ROBE. Air travel costs a fortune and is bad for the environment, but on top of that they keep you and your dinner frozen.

When J. Smith-Cameron was growing up in South Carolina, prep was the fashion currency in her school’s hallways. Smith-Cameron sported knockoffs from Sears, until she and her best friend discovered the thrift store. The pair dug through piles of clothes to find embroidered shirts and bandannas, channeling hippie aesthetics a few years too late. They didn’t mind being off-trend, because they saw clothes as costumes. “And this was before I was a professional actor!” says Smith-Cameron.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY STEPHANIE DIANI

She’s carried this sense of sartorial play throughout her career, sporting styles as austere as her Succession character’s power suits and as sumptuous as the cobalt Carolina Herrera dress she was captured in for Vogue earlier this year. Off-camera, she’s tapped into old school glamour with nudging from her stylist Cat Pope. “I would never have had the balls to do that without her,” confesses Smith-Cameron. But as her onscreen personas know well, you don’t need balls to make an impact.

64 culturedmag.com

ALWAYS COMBINE BLACK AND NAVY.

JAMIAN JULIANO-VILLANI

ALWAYS BUY CHEAP LIQUOR.

You’re just going to PISS IT OUT. or Easter

BE WORRIED ABOUT LOOKING LIKE CHRISTMAS

NEVER

ALWAYS HAVE TRANSITIONAL SUNGLASSES for antisocial situations.

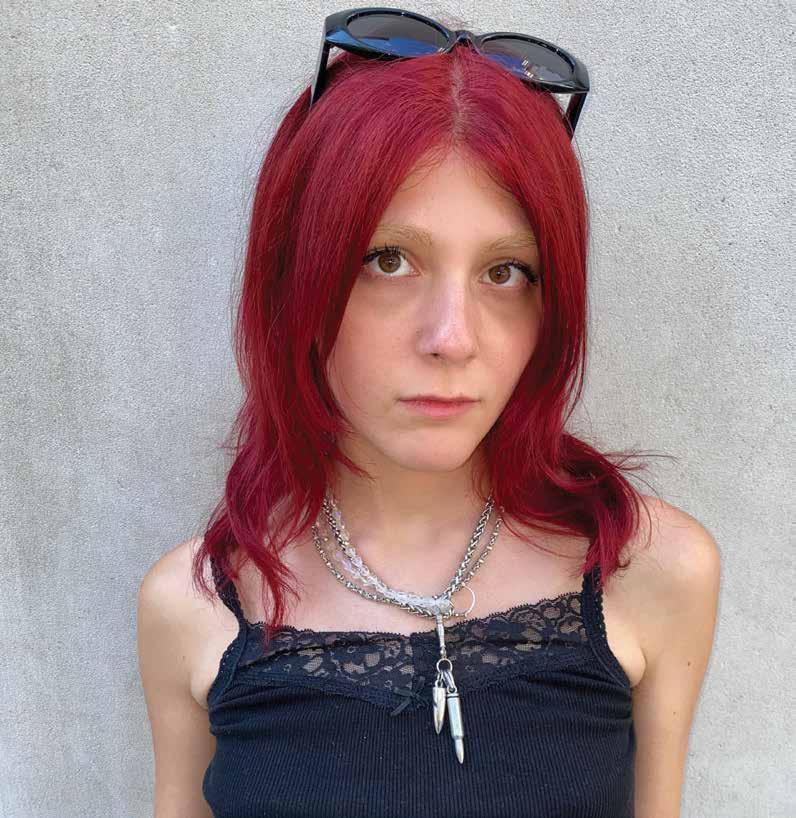

During her time as an art student at Rutgers University, Jamian Juliano-Villani dyed her hair green to avoid Thanksgiving. The New Jersey native knew her parents—a “guido beach boy” and “Carmela Soprano to a tee”—wouldn’t let her come home looking like that. She had giant plugs, too, “which is, like, the worst mistake ever.” Her deviant status didn’t stop her from being captain of the cheerleading team, though, and it is this balance of abrasive disregard for decorum and overachieving work ethic that has made Juliano-Villani an art world magnet. Her personal style penchants—“disgusting Stouffer’s-covered T-shirts” in the studio, “semi-professional fake Prada suits” at O’Flaherty’s, and miniskirts and knee socks when she needs to look like a “halfway decent human”—don’t make her any less noticeable. A fast-fashion apologist, Juliano-Villani loves the thrill of buying tons of things that she can lose immediately. But she’s not allergic to haute couture—her fever dream would be to inspire a Gucci and Mary Quant collab: “I have a whole line in my head, and they gotta pay attention.”

PHOTOGRAPHY BY ZOE CHAIT

NEVER ASK ADVICE FROM LAWYERS OR DOCTORS. They look for problems, not solutions.

ALWAYS SPRAY TAN TWO DAYS BEFORE THE EVENT.

NEVER FUCK ANYONE

WHO DOESN’T HAVE A CLEAN BLAZER.

66 culturedmag.com RULES TO LIVE BY

RULES TO LIVE BY

RACHEL TASHJIAN

ALWAYS HAVE A COCKTAIL DRESS IN TAFFETA OR NYLON

(THINK WINDBREAKER MATERIAL!) or a wool-and-silk blend, in the crispest and most dangerous black you can find. You can ball it up like dirty laundry in your suitcase or closet and shake it out for emergencies and languorous events alike.

NEVER FORGET TO DEVELOP AN UNHEALTHY OBSESSION WITH A SINGLE DESIGNER

Refuse to wear anything but their clothes for several years, enmesh your entire identity with the symbolism and semantics of their runway output, and then abruptly change your mind and move onto something else.

ALWAYS ASK MORE QUESTIONS THAN YOU ANSWER.

NEVER WEAR A LOGO OR WORDS ON YOUR T-SHIRT

OR SWEATSHIRT. Unless you are friends with the person who made it.

NEVER HESITATE TO IGNORE MEDIOCRITY.

ALWAYS DRESS YOUR TABLE,

living room, and bedroom as meticulously as you attire yourself. Create the YOU EXTENDED UNIVERSE—insist on personalizing your mentally sprawling domain.

ALWAYS WATCH AT LEAST FOUR MOVIES, READ AT LEAST THREE BOOKS, AND GO TO AT LEAST TWO MUSEUM SHOWS A MONTH.

Your outfits will be better, your accessorizing more attentive, and your weekends more extravagant.

In 10th grade, Rachel Tashjian wrote a short story about a woman going on a blind date. When her protagonist showed up, the guy was wearing Tevas, so she left. The New York–based fashion critic behind the beloved, and exclusive, “Opulent Tips” newsletter describes her latest stylistic era as “luxury bizarro,” citing brands like Loewe, the Row, and Alaïa, which, she says, produce strange and exquisite garments that have “a sense of connoisseurship to them.” Since she joined the Washington Post as a fashion writer in April, though, her vestimentary needs have shifted. She’s been working remotely, and mostly mulls over what to wear on walks with her dog, Ritz. You can find her in an assemblage of loose linens, silks, cottons, and, more often than not, an outré hat, hitting the New York streets with her canine companion.

68 culturedmag.com

PHOTOGRAPHY BY ZOE CHAIT

Awol E rizku Delirium Of Agony

8 – October 21, 2023 SEAN KELLY | NEW YORK

September

RULES TO LIVE BY OTTESSA MOSHFEGH

NEVER GO TO SLEEP WITHOUT AT LEAST ONE DOG IN THE BED.

If you don’t have a dog, invest in a good stuffie and give it a pet name such as Fluffy or Monsieur le Dog or Cutiepie. Just do this. Keep Cutiepie in the bed with you. We all need some companionship and protection while we dream.

If the source is a human being, compliment the person. Say, “Wow. You smell wonderful.”

Also, if the pharmacist at Rite Aid looks beautiful, tell her so, damnit. She deals with sick people all day who don’t give a shit about her, and she looks good. Say, “Wow, you look beautiful.” You’ll feel better immediately.

ALWAYS SEEK OUT FRIENDSHIPS WITH PEOPLE WHO ARE SMARTER THAN YOU.

IF YOU FEEL UNSURE OF YOURSELF, ALWAYS THROW OUT YOUR MIRRORS

Put a dark curtain over a window. Anytime you’d like to see yourself, go outside and get some fresh air. Hear the birds and the wind rustling the leaves. Stand before the darkened window and have a look. Your reflection will be far more optimistic when you see that you’re just another creature in the wild.

ALWAYS PLACE ANTIQUE PHOTOGRAPHS OF STRANGERS AROUND YOUR HOME.

Under the salt and pepper shakers. In the kitchen cabinet. Taped to the bathroom wall. Most people are dead. You are so lucky to be alive.

Ottessa Moshfegh embraces the edge. The Los Angeles–based writer’s characters swing from stupor to frenzy, riding out breakdowns and breakthroughs with languid flair. Her unique brand of psychological turbulence resonates—Moshfegh’s 2015 debut novel, Eileen, has been adapted into a film, out this December; and her 2018 follow-up, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, was met with rave reviews. At home in Southern California, Moshfegh fills her wardrobe with vintage finds that she rarely wears. Though her standard uniform is baggy jeans, a sweatshirt, and Puma slides, her eye for the idiosyncratic has paid off: Last year, the writer was invited to walk the runway for Maryam Nassir Zadeh at the Fall/ Winter 2022 New York Fashion Week. “It was a terrifying thing, being the conduit for these creations,” she recalls. For Moshfegh, clothes are objects of affection, vessels that embody the thrill of discovery. No surprise, then, that three rooms in her home are dedicated to their storage. “It is my hobby and my obsession,” she says, “And a bit of an addiction.”

PHOTOGRAPHY BY HANNAH TACHER

PHOTOGRAPHY BY HANNAH TACHER

70 culturedmag.com

IF YOU SMELL SOMETHING WONDERFUL, ALWAYS FIND THE SOURCE.

HELENA TEJEDOR

ALWAYS WEAR PAJMAS TO BED AFTER A NIGHT OUT.

It will make you feel more civilized.

ALWAYS READ THE NEWS,

even if it’s just one article a day.

ALWAYS WEAR NICE LINGERIE,

even underneath a hoodie. The key to feeling your best is dressing for yourself, not for others.

When Paris-based stylist Helena Tejedor hires a new assistant, she sends them a list of films to study. Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Millennium Mambo; Darren Stein’s Jawbreaker; Bigas Luna’s Jamón, Jamón… her curriculum is vast in its socio-geographical circumference, but each film taps into and interrogates shades of femininity, from the two-faced teen queen to the ennui-ridden club girl. Women, and what they wear, are as central to Tejedor’s career as they are to her sense of self. This is an obsession that she traces back to the womb. Her Spanish mother would tell Tejedor, “The chicest person is the one who knows how to dress for the occasion.” Naturally, the stylist rebelled during her teen years: The low-rise jean was her act of treason, Posh Spice her patron saint. In the time since, she’s cycled through wardrobes and achievements—fashion director of L’Officiel Hommes by 25, editorials in Vogue Italia a few years later, consultant to Helmut Lang and now Coperni—before landing on her current “effortless” and intellectual ’90s-inspired ethos.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY LÉON PROST

ALWAYS MAKE SURE YOUR SPELL ING IS IMPECCABLE, even if it’s a text message. Bad spelling is very unattractive.

NEVER TAKE ADVICE FROM ME. NEVER POST VIDEOS OF CONCERTS ON INSTAGRAM.

The sound is shit and the magic is lost. It’s like taking a picture of the moon.

NEVER WEAR MONOGRAMS;

it’s small-dick energy.

NEVER WEAR HEELS IF YOU CAN’T WALK IN THEM.

It’s a sign of weakness, and you’ll look stupid.

72 culturedmag.com

RULES TO LIVE BY

Celebrating 25 Years HOSTLER I BURROWS NEW YORK 35 East 10th Street New York, NY 10003 hostlerburrows.com LOS ANGELES 6819 Melrose Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90038 HB381 NEW YORK 381 Broadway New York, NY 10013 hb381gallery.com

A Well-Adorned Hand

TODAY, Egyptian pharaoh Hatshepsut is known as “the first great woman of history,” but her legacy was lost to time for centuries: obelisks torn down, temples walled up, and monuments defaced by her male successors. During a collaboration with the Metropolitan Museum of Art last year, Jess Hannah Révész fell into a deep Hatshepsut rabbit hole. “I became completel y obsessed,” she says. The 32-year-old designer—founder of the independent jewelry brand J. Hannah—created a capsule of rings and necklaces for the museum’s gift shops inspired by a cache of carved stone amulets found in the pharaoh’s tomb.

The ongoing partnership with the Met—which allows Révész to trawl the depths of the museum’s permanent collection and consult with its curators—has been a fruitful one for the designer, whose line of modern heirlooms takes many of its cues from art history. She sees her pieces— rings, pendants, and hoops constructed from recycled 14k gold and silver—as keepsakes whose value lies in their ability to endure. “I’m not trying to reinvent the wheel,” she explains. “I’m interested in designs that are timeless for a reason.” This reverence for talismans of the past has sparked a number of collaborations, including one with A24 (Révész is designing her own version of the vintage heart locket worn in Sofia Coppola’s forthcoming biopic Priscilla), and another with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art tied to an upcoming September exhibition.

Soon entering its 10th year, J. Hannah was born cottage industry–style in Révész’s college apartment in San Luis Obispo, California. The designer fell in love with metalsmithing when she fell out of love with school, learning the craft from a former jeweler who taught hobbyists out of her garage. “It was a bunch of older women—who were approaching it in a very chill way—and me,” she

recalls. When she surpassed the skills of her instructor, she moved on to a hybrid of YouTube and local courses. Révész set up a bench in her bedroom and started drawing up very specific Hanukkah wish lists—“flex shafts, pliers, and torch saws.”

It’s been a long time since she’s made jewelry herself. When demand for Révész’s designs outpaced her ability to make pieces with her own two hands, she relocated to a studio in downtown Los Angeles, recruiting a stable of veteran bench jewelers on Hill Street who could meet her sustainability demands at a larger scale. In the eight years since, J. Hannah has evolved to incorporate a line of cruelty-free nail polishes in subtle hues—a logical coda, says Révész, “to complement a well-adorned hand.” As the brand grows, she finds herself confronting the “less sexy” demands of her current role—content planning, payroll, and “emails, emails, emails.” But the polishes offer Révész a rare chance to float in the free-associative “soup” that is inspiration. “Compost,” a fecund green shade, is a luxuriant take on an infamously unappetizing Pantone swatch. “Ghost Ranch” is based on Georgia O’Keeffe’s earthy, arid palette. “Saltillo,” a faded pink, is inspired by the tip of her cat’s nose. “You have to be open to following that thread,” she says, “a flower I see on a walk, a button I see on a shirt that reminds me of a line I read in a book… Sometimes it sparks a good idea, and sometimes simply doesn’t.”

Recently, the designer has directed her energy toward a new creative endeavor: art objects for the home. Officially, the debut collection of J. Hannah lamps— elegant interplays of corrugated glass and metal released last August—represents an exploration of light through the lens of a jewelry designer. “But honestly, it’s simpler than that,” she muses. “I just want to make beautiful things that last.”

78 culturedmag.com

With a string of museum collaborations on the horizon, Los Angeles–based jewelry designer Jess Hannah Révész dives deep into the art historical canon, crafting pieces with a will to endure

BY MARA VEITCH

PHOTOGRAPHY BY MADDY ROTMAN

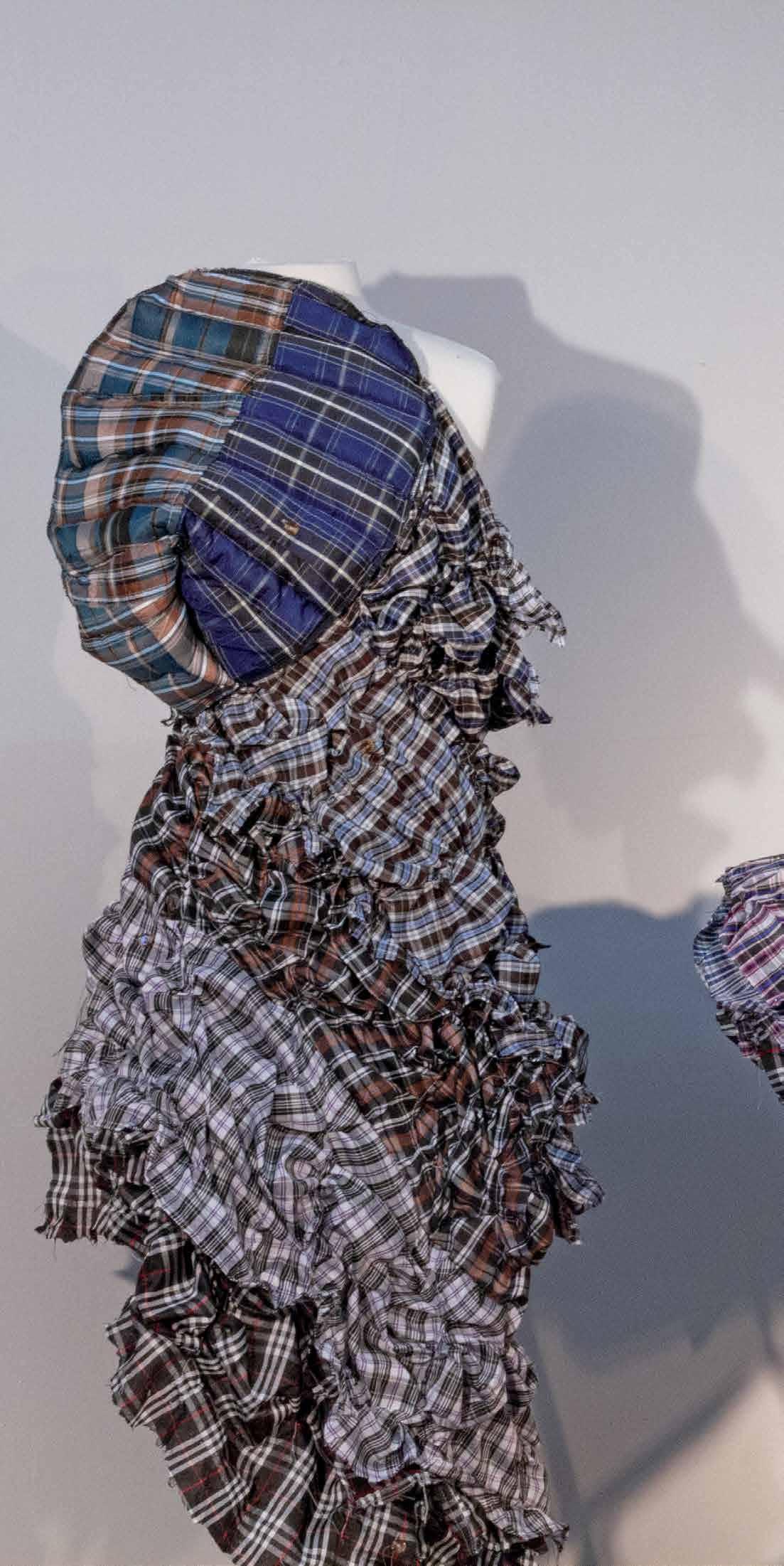

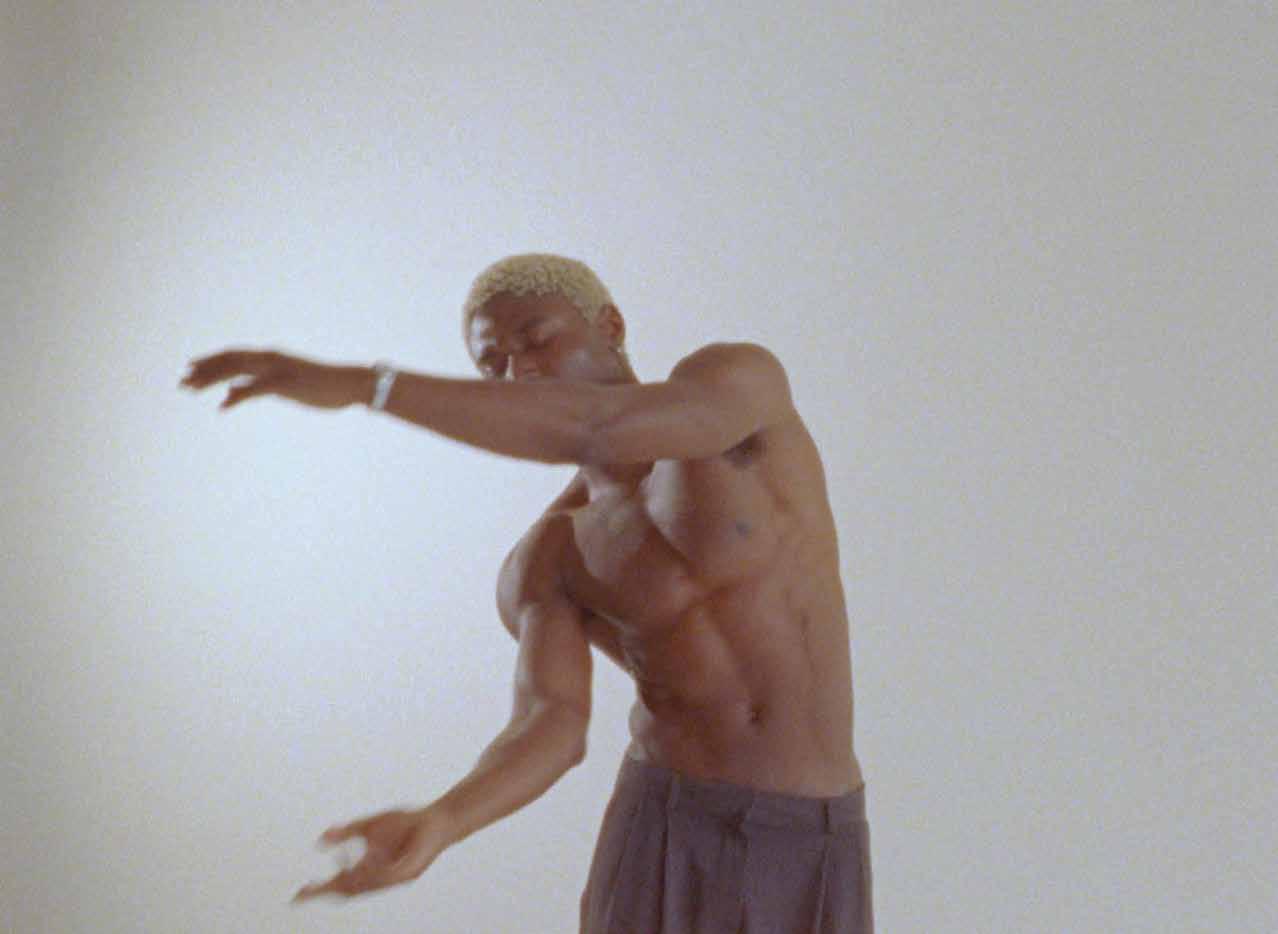

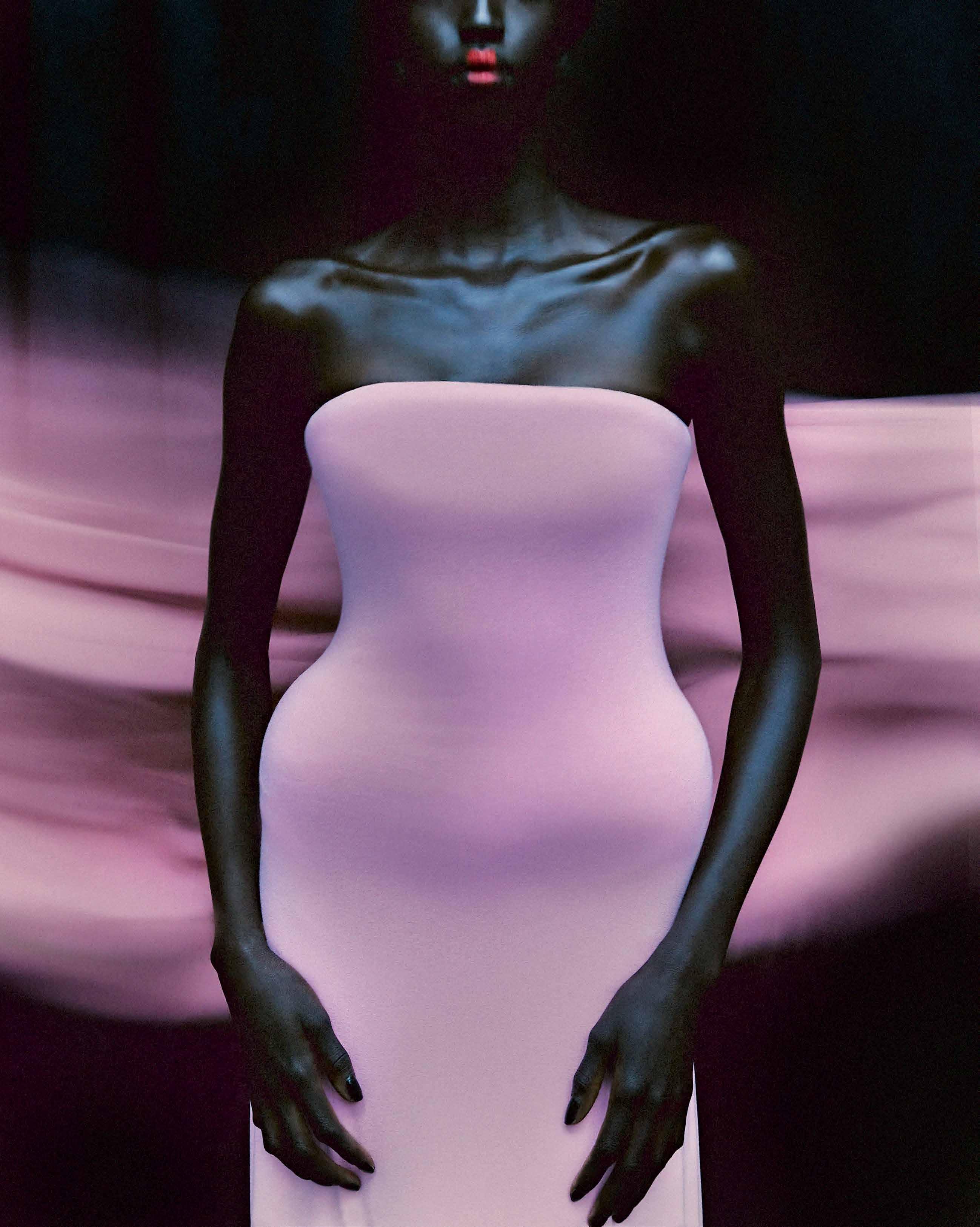

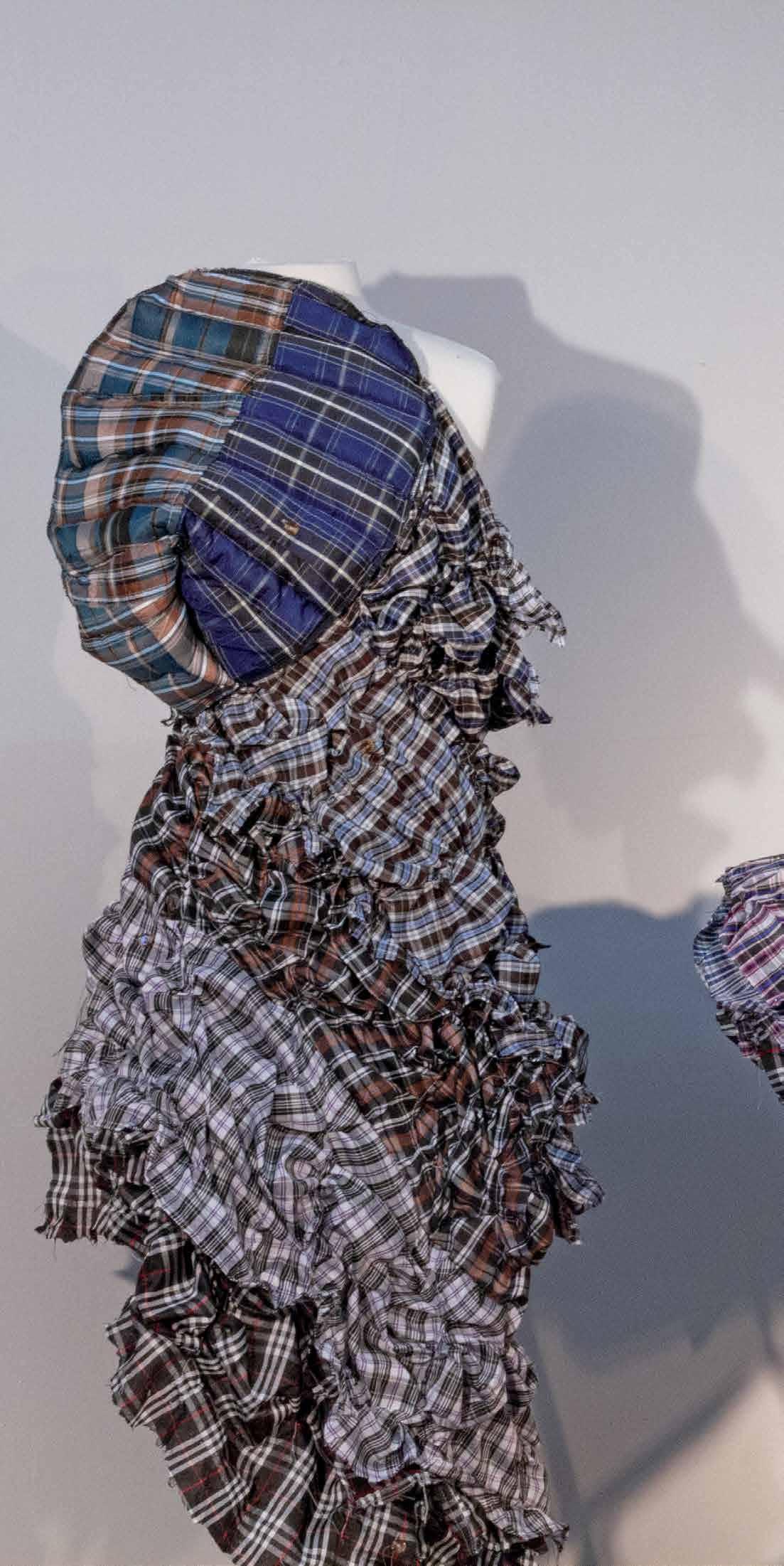

For Michael Stewart, the Body Is a Landscape

The London-based designer’s sculptural fashion label, Standing Ground, built its credo on Irish mysticism, fantasy classics, and an intuitive approach to craft.

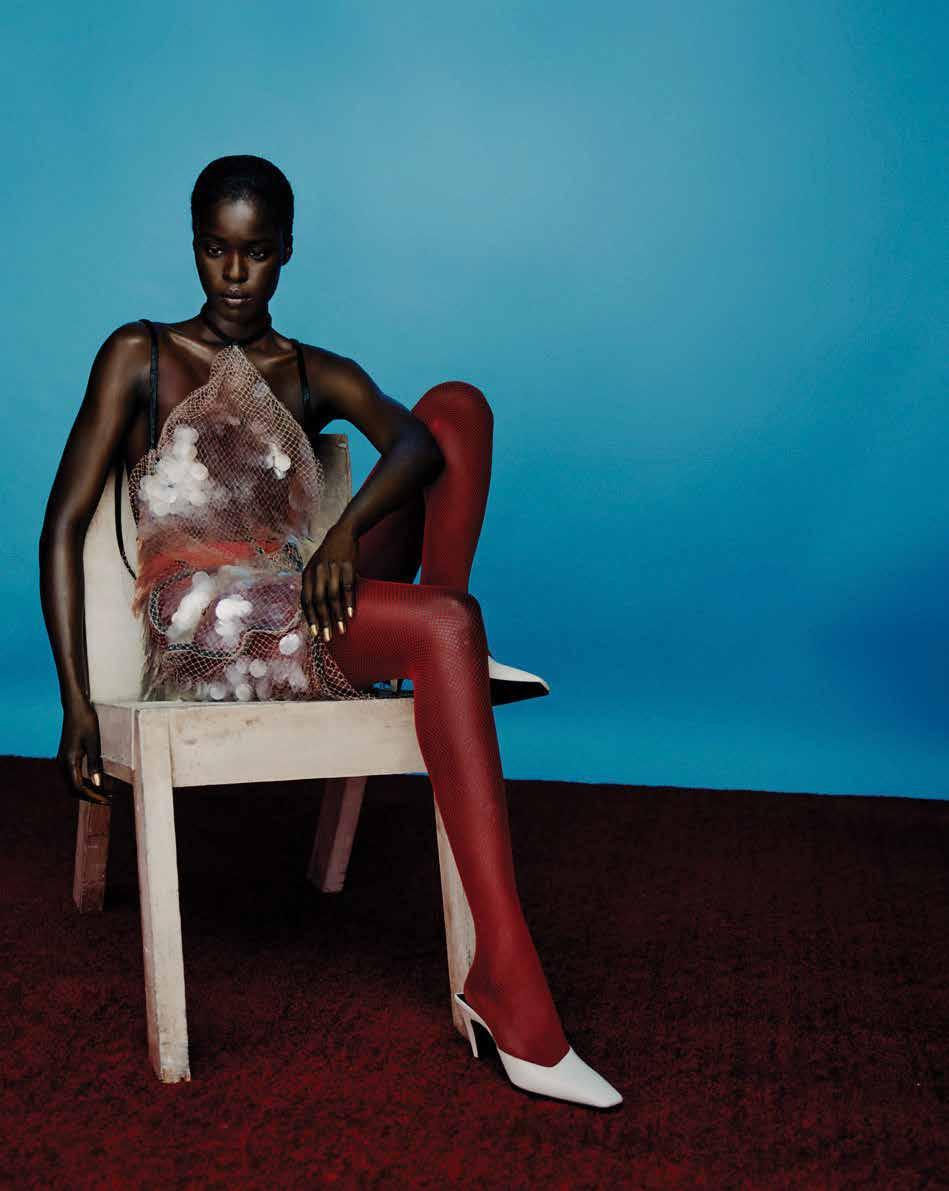

BY GÜNSELI YALCINKAYA PHOTOGRAPHY BY DANIEL ARCHER STYLING BY STUDIO&

80 culturedmag.com

ALL CLOTHING BY STANDING GROUND.

culturedmag.com 81

IRELAND’S STANDING stones and dolmens are the oldest remaining neolithic monuments in the country. For Michael Stewart, the designer behind London-based label Standing Ground, they are portals through time: stoic witnesses to the eons. He recalls taking frequent trips to visit them as a child, enchanted by the centuriesold mysticism buried deep within. “Ireland is a superstitious country, which is a good thing, because the dolmens have been preserved and protected over time,” he muses. “They’re feared in a way, so people don’t dare touch them.”

It’s no secret that Stewart’s connection to these megalithic tombs informs his brand’s name and modus operandi. Speaking from his new studio at the Sarabande Foundation in East London, he explains that the dolmens possess a transcendent quality, which he projects onto his own statuesque garments: deceptively simple creations that borrow from the futurism of sci-fi and fantasy classics, such as Lord of the Rings, to imagine evening wear, custom garments, and body ornaments that feel rooted in neither past, present, nor future.

After graduating from the Royal College of Art in 2017, Stewart established Standing Ground in 2022, before attracting the attention of Lulu Kennedy’s Fashion East incubator program, and making his London Fashion Week debut as part of the Spring/Summer 2023 shows. Remaining loyal to his source material of neolithic artifacts and figures, he freely admits to having done no new research since his master’s degree, and doesn’t use a mood board or sketches. Instead, Stewart takes an intuitive—and manual—approach to draping, sculpting, and craft, developing his own lines and patterns by hand to produce alien silhouettes that flow from and protect the body like topographic armor.

The designer is currently working on his third collection for Spring/Summer 2024, which expands on the dialogue between distant pasts and otherworldly futures. “It’s different to what I would’ve presented last February, which was very beautiful, but not as menacing,” he confesses. “I wanted to take some time to figure out what I was doing, and not pigeonhole myself.” This collection dials back the clock to pre-human times, focusing on primordial and fossilized forms to create uncanny garments that explore the relationship between objects and their surrounding environment. Imagining a world where ancient objects grow and shapeshift across each collection, the designs suggest a speculative place where humankind and nature are mirrors for each other—or, as Stewart puts it: “where the body is a landscape and the landscape is a body.”

82 culturedmag.com

“I wanted to take some time to figure out what I was doing, and not pigeonhole myself.”

Makeup by MACHIKO YANO

Hair by MOE MUKAI

Casting by AAMØ CASTING

Model NYAUETH RIAM

Fashion Assistance by FLORENCE THOMPSON

Makeup Assistance by KRISHNA BRANCH-MACKOWIAK

culturedmag.com 83

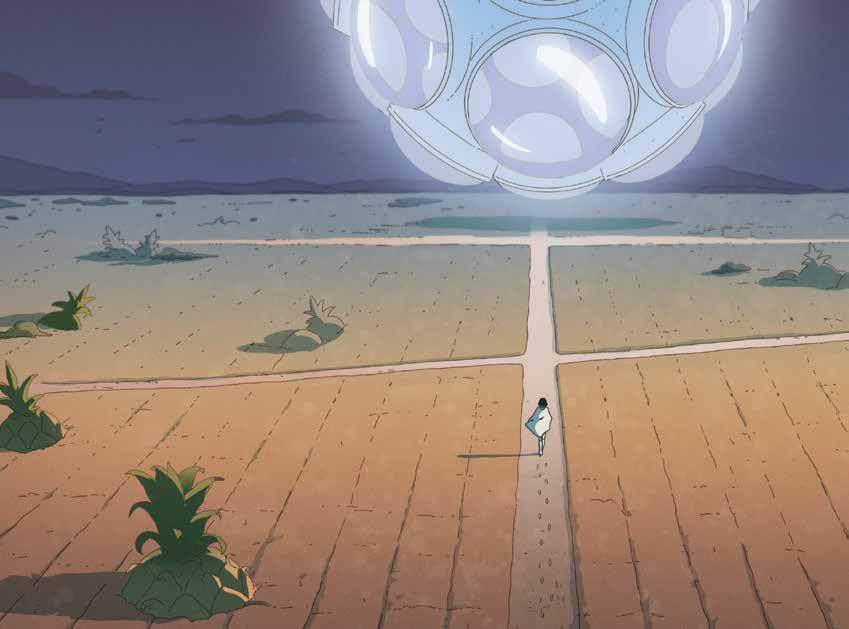

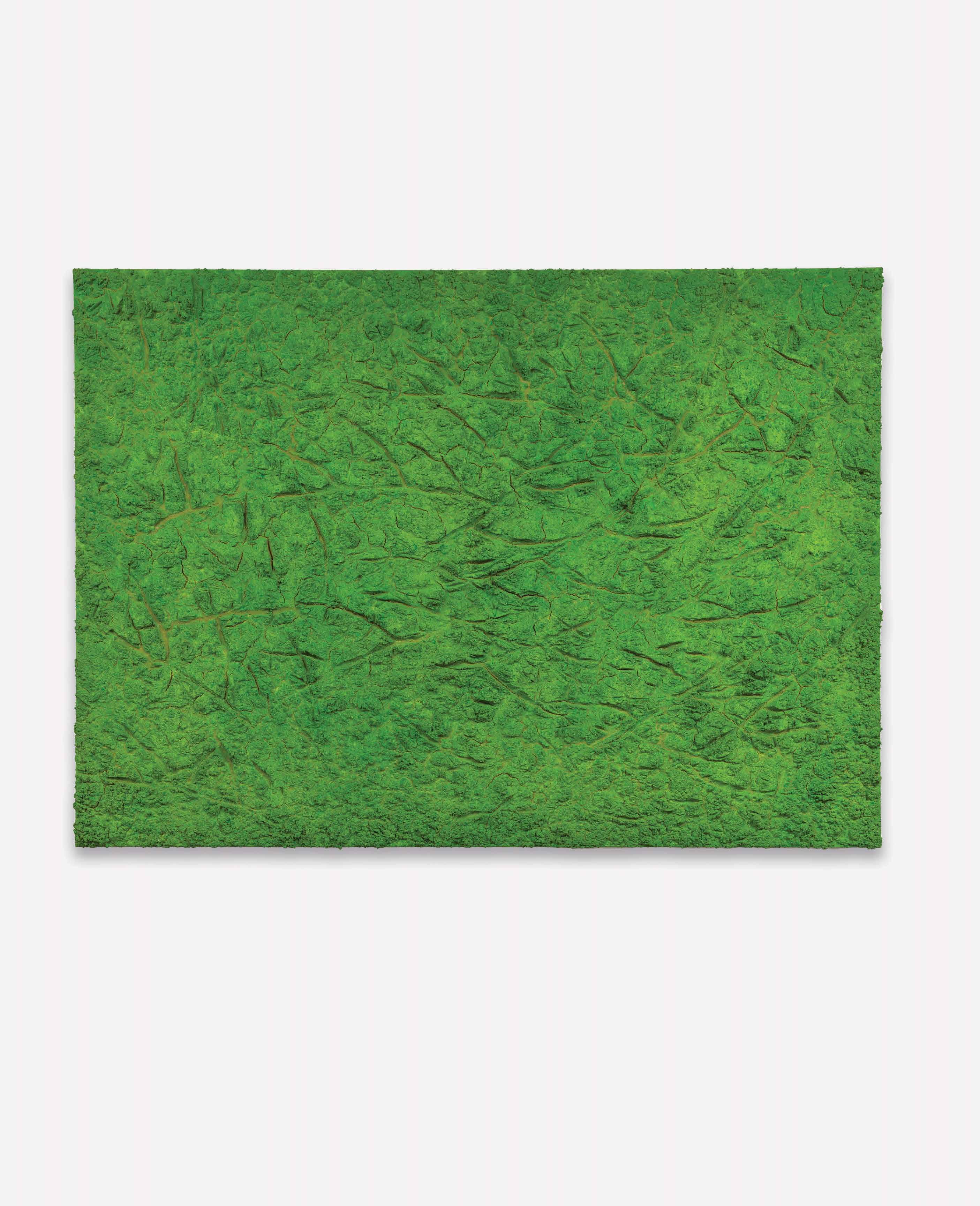

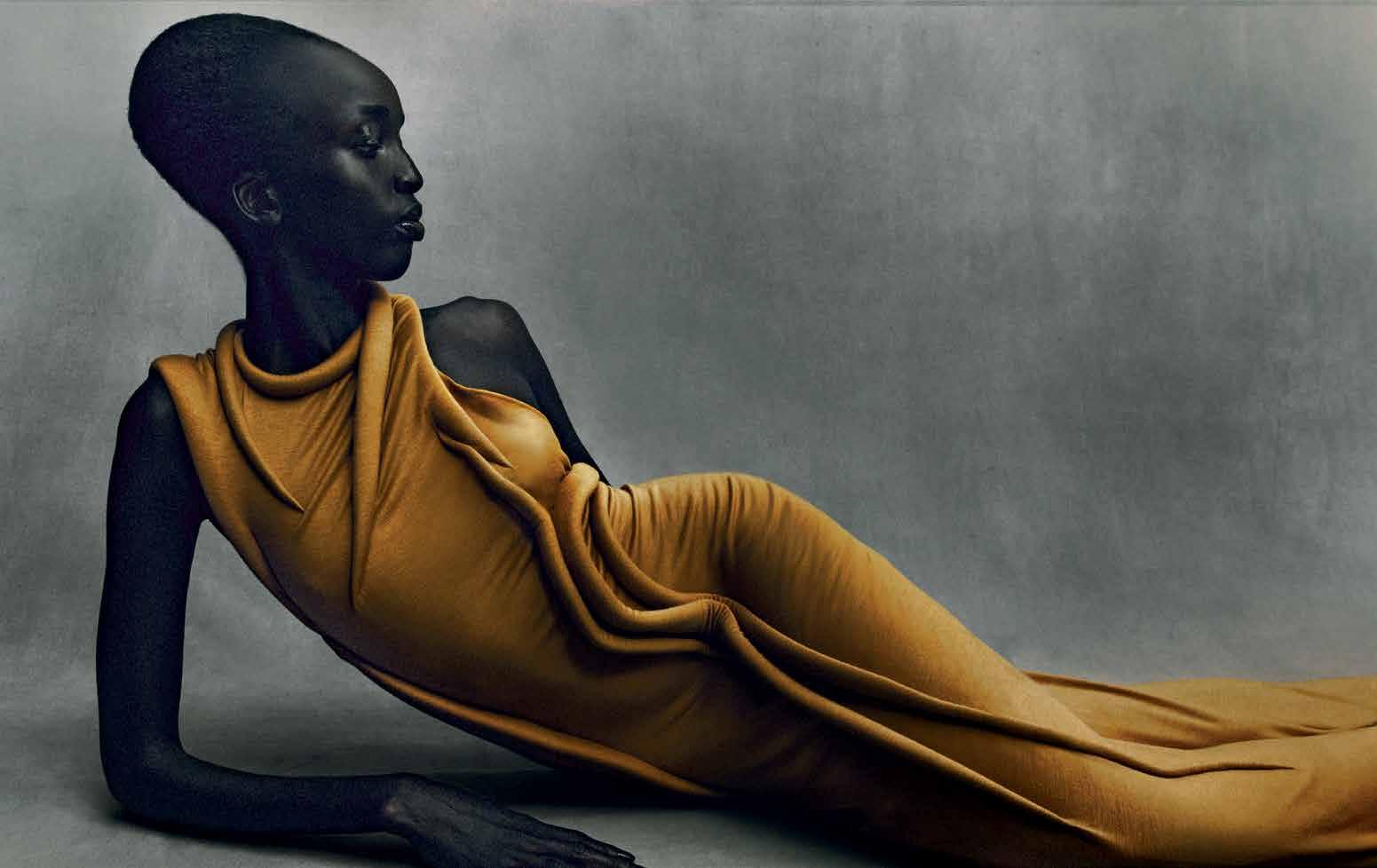

Painting for the End Times

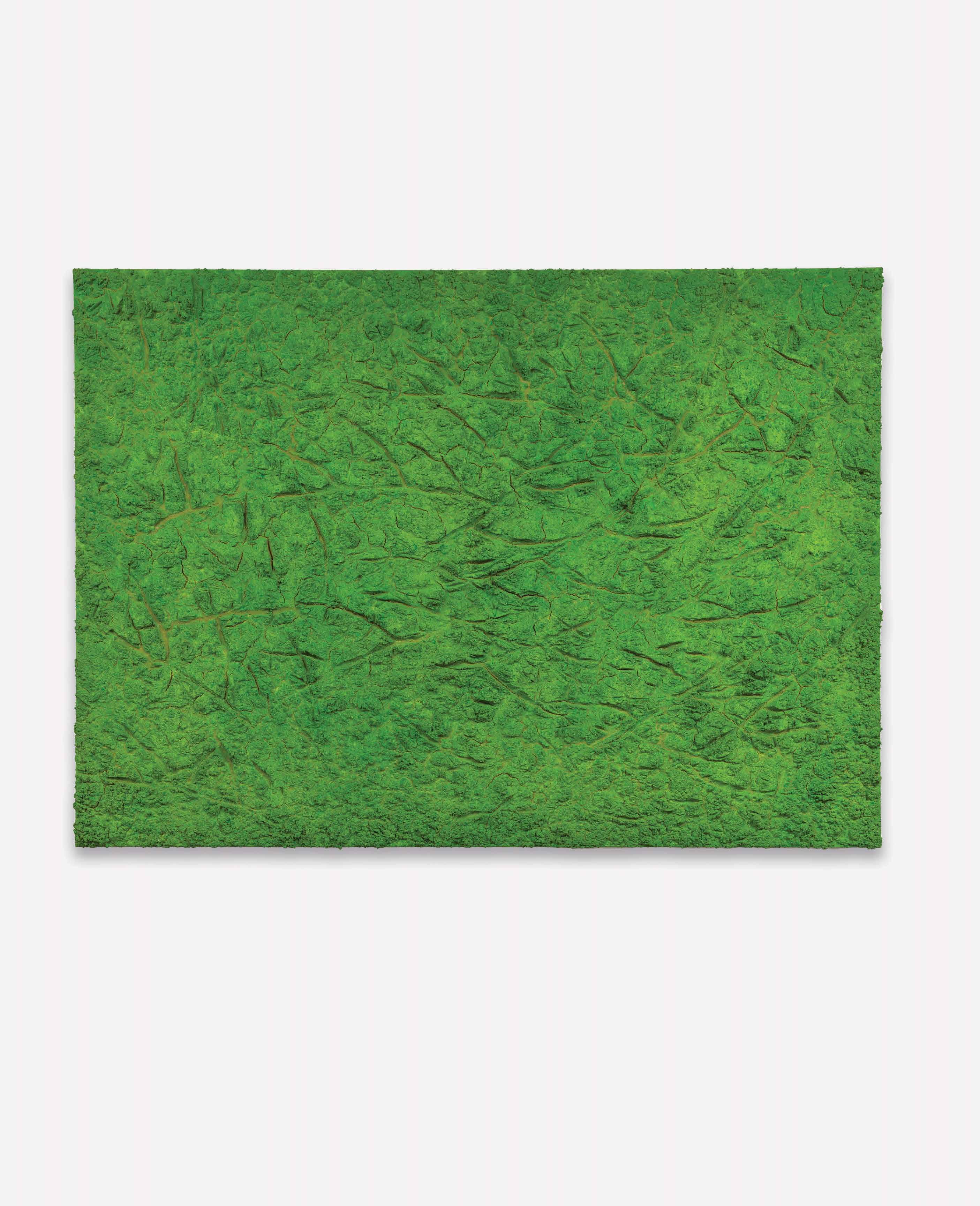

“The end of the world is not new,” says Nicolas Party. “We’ve been creating stories about floods and fires since our very beginnings.” The Swissborn artist is sitting in his Red Hook, Brooklyn, studio, surrounded by a small army of miniature dinosaurs—long-necked Brachiosauruses, by the looks of it—which he’s painted into petitely scaled oil-on-copper compositions. “I’ve been wanting to paint dinosaurs—monsters, really—for a long time,” he continues, with a glimmer of a smile. “Now that they’ve emerged, they’re actually quite small.”

Party is putting the final touches on these paintings for “Swamp,” his first solo exhibition with Hauser & Wirth in New York at the gallery’s 22nd Street location. Known for virtuosic pastel drawings that honor and challenge traditions of still life and portraiture, the artist seems to be grappling with the precarity of human life and our ecological crisis. These sentiments are captured succinctly in Triptych with Dinosaurs, 2023, one of several three-paneled “cabinets” included in the show. An infant, alien in its newness, occupies the composition’s central panel while peaceful-looking dinosaurs flank the child on either side, like a baby Jesus and angels. Party based the central painting on a photograph of his daughter, who turns one this fall. “Having a child makes you see time very differently,” he says. “Suddenly, people ask you if you have a will. I’m 43; fatherhood is happening a little bit later in life… I’ll only have her for so long. Dinosaurs are an iconic symbol of a creature out of time.”

For the artist, the extinct creatures hint at the possibilities of a post-human world. “First,

BY KATIE WHITE

there are these giant lizards, but shit goes down and the dinosaurs disappear. Then these overly smart monkeys emerge,” he muses. “I can’t help but wonder what will dominate when humans disappear.”

Beyond this newly emergent fascination with the Mesozoic Era, Party continues, more familiarly, to engage with art history in other works. After paying homage to 18th-century pastel artist Rosalba Carriera with a recent installation at the Frick Madison, he has turned his attention to Rosa Bonheur, a 19th-century French painter famed in her lifetime for her highly precise portraits of animals. “Swamp” features four of Party’s uncanny androgynous pastel portraits, each juxtaposed with an animal pulled from Bonheur’s oeuvre.

“Rosa has been revisited recently through the lens of ecofeminism,” Party tells me. “That’s not a term that existed in the 19th century. Still, the way she depicted animals, and our relationship with them and nature, feels extremely modern. These kinds of anachronisms are central to this exhibition.”

Two new site-specific murals at the gallery elaborate upon Party’s alluringly luxuriant, yet apocalyptic visions. Extensions of both his “Swamp” and “Red Forest” series, the murals are intended to transport viewers into a churchlike moment of reverie. One, with red, blazing trees, inevitably calls to mind the recent Canadian wildfires. “Forest fires are one of the most visually striking events of our time,” he says. “I want the exhibition to have that kind of transcendent quality, rooted in today, but linked to the past. Frightening, but also beautiful.”

84 culturedmag.com

Swiss artist Nicolas Party’s latest works, on view at Hauser & Wirth in New York until late October, imagine epochs before and after mankind.

85 culturedmag.com

Portrait of Nicolas Party by Richmond Lam. Image courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

DON’T MAKE LUNCH. MAKE THUNDER.

RANGES | OVENS | COOKTOPS | VENTILATION | MICROWAVE DRAWERS | REFRIGERATORS

THORKITCHEN.COM MEMBER #COOKLIKEAGOD

Kitchen: a complete line of full-featured, superbly crafted, stainless steel warriors. Dual fuel, gas and electric options. 4,000–18,000 BTU burners. Infrared broilers. LED panel lights. Continuous cast iron grates. Heavy-duty tilt panel controls. Massive capacities. LightningBoil™ speed. Brilliant blue porcelain oven interiors. And more. The real value in pro-grade performance. © Copyright 2023 THOR Kitchen, Inc. | All Rights Reserved. 23TINT01-04-149355-1 WINE COOLERS | ICE MAKERS | DISHWASHERS | BBQ GRILLS | PIZZA OVENS

THOR

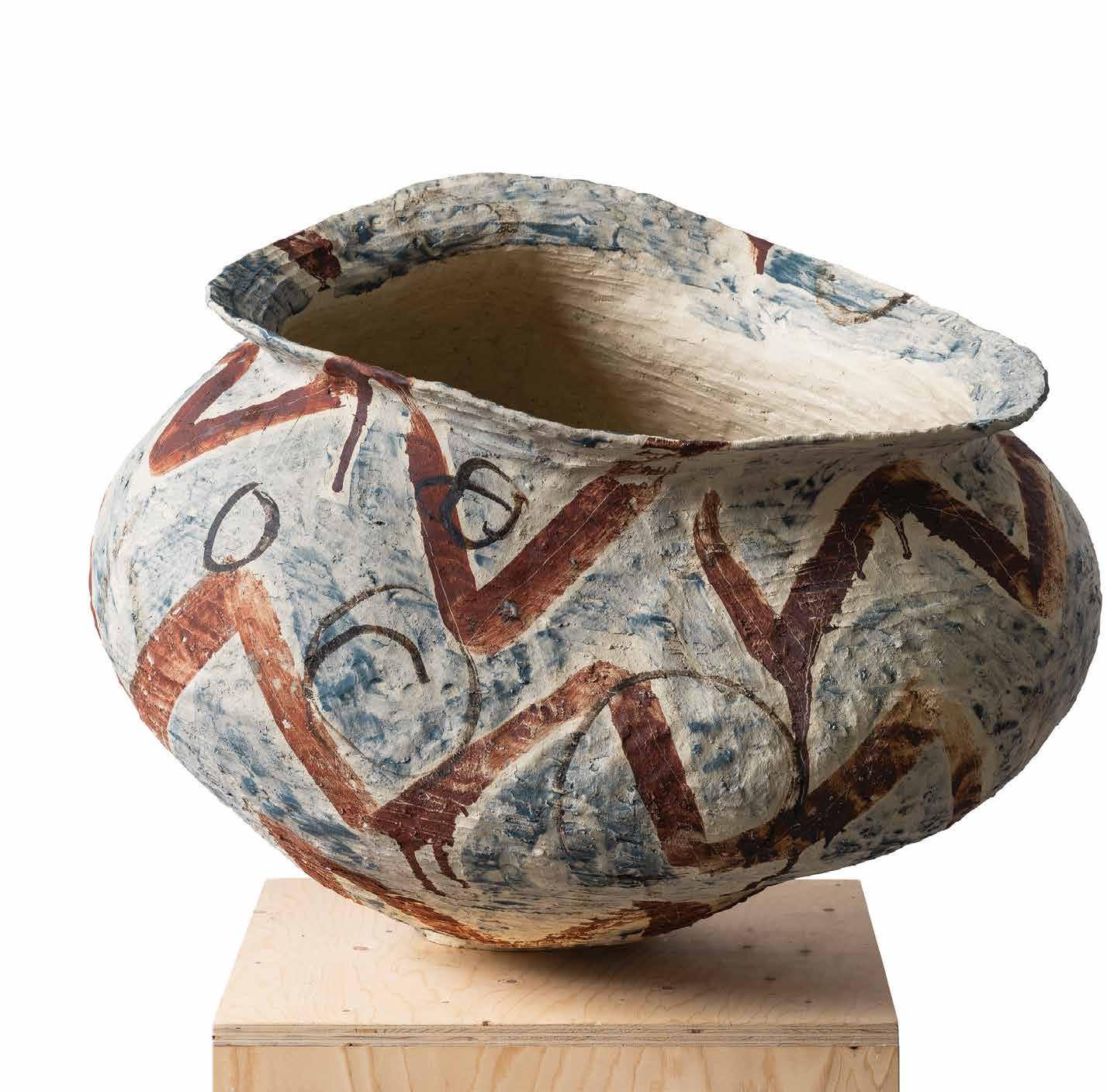

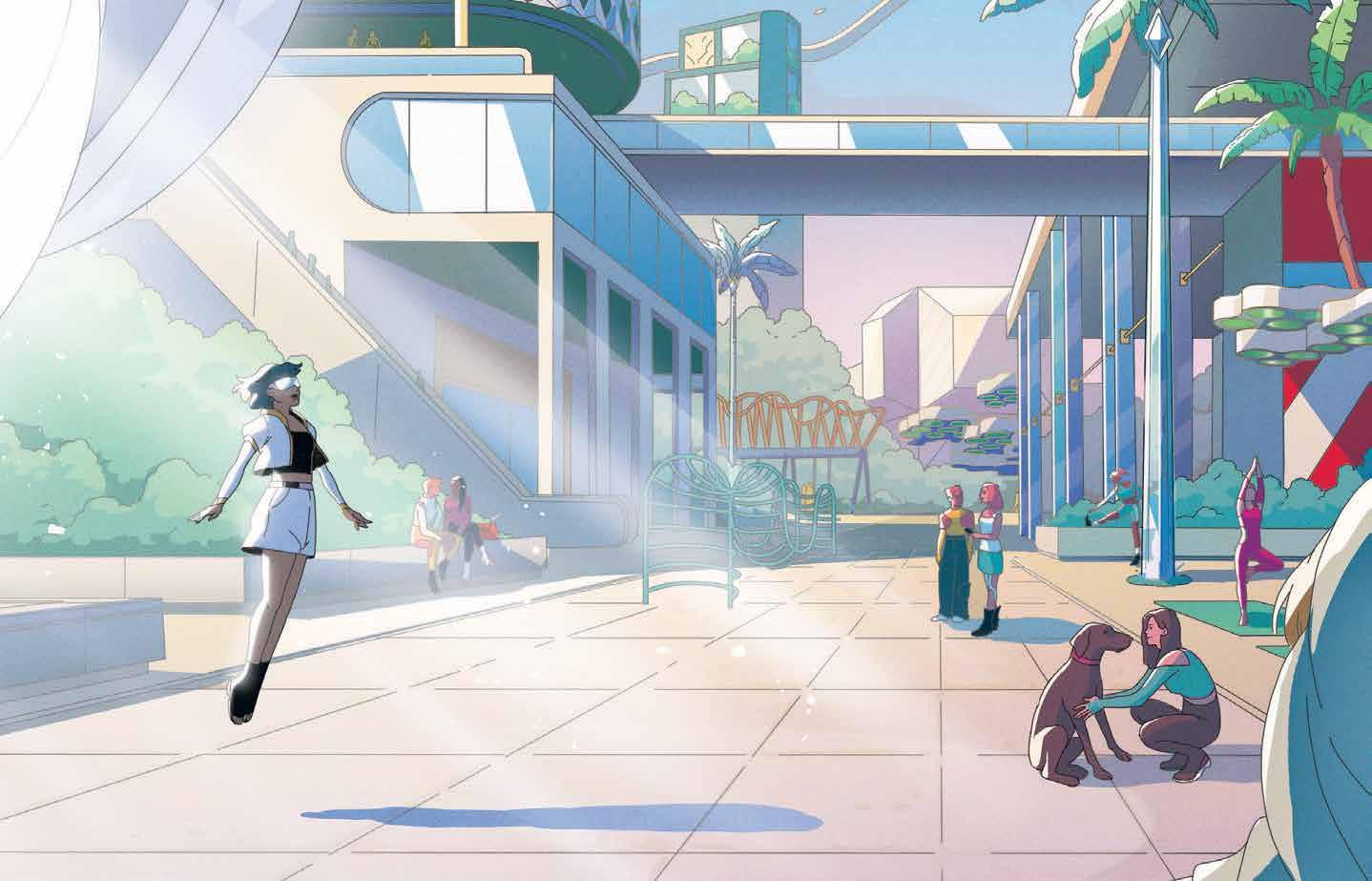

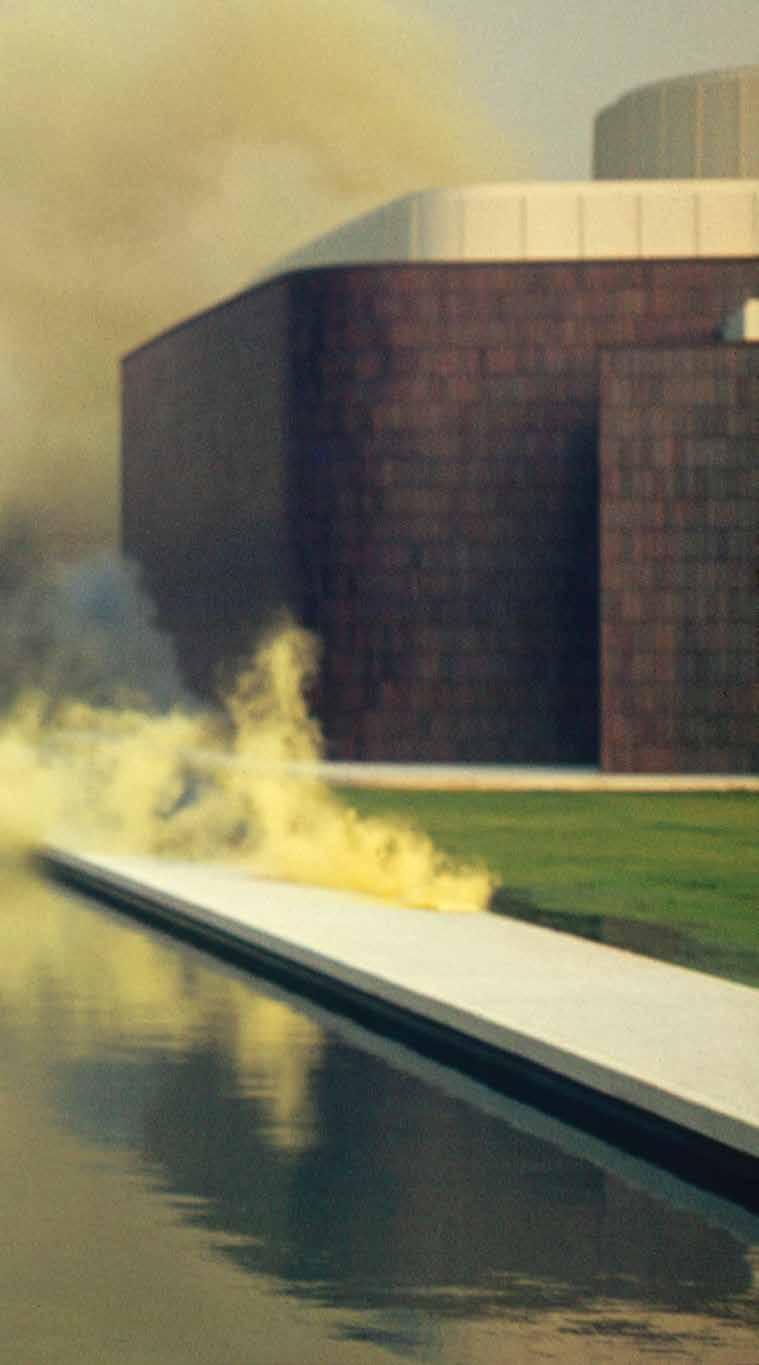

We Are

in the Soup Now

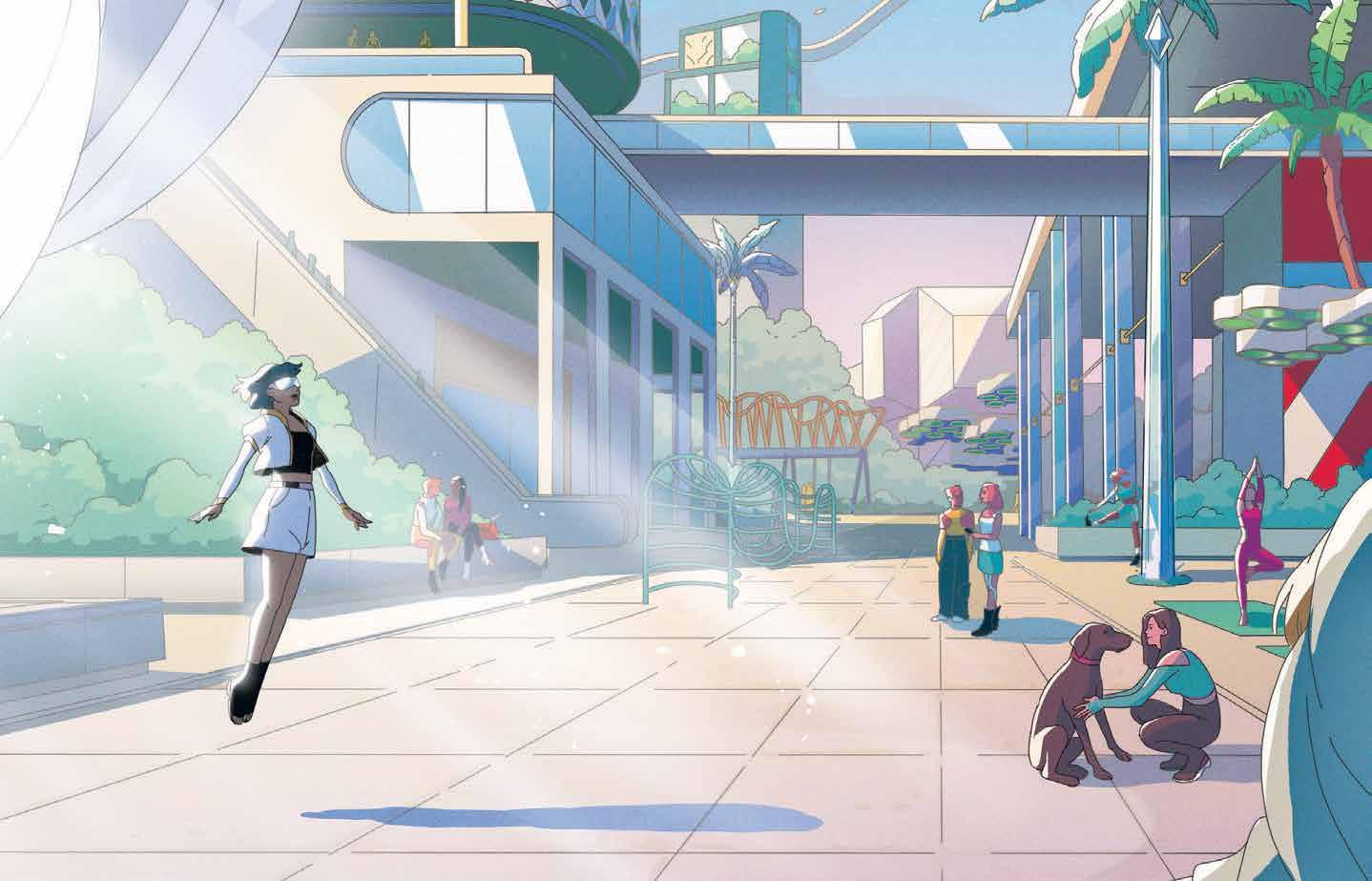

RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA’S INAUGURAL U.S. SURVEY, “A LOT OF PEOPLE,” WILL FILL MOMA PS1’S HALLS THIS OCTOBER.

THE EXHIBITION EXCAVATES FOUR DECADES’ WORTH OF WORK FROM ONE OF OUR ERA’S MOST CATEGORY-DEFYING ARTISTS, AND SHOWS US HOW MUCH WE OWE TO HIS PERIPATETIC PRACTICE.

BY KAT HERRIMAN

DIGESTION IS NEVER INSTANTANEOUS.

Its nature is process. It spans hours, sometimes centuries. For example, a meal of rice noodles dressed with tamarind sauce and peanut crumbs—served in February 1990 as one of artist Rirkrit Tiravanija’s early food works, untitled 1990 (pad thai) —was probably extruded through the intestines of participating New Yorkers overnight. But the radicality of the gesture remains deep in the guts of the art world, pervading our cultural biome and the way we see ourselves as artists and viewers. It is into these roiling bowels that curators Ruba Katrib and Yasmil Raymond dared to venture, bringing us “A LOT OF PEOPLE.” The MoMA PS1 show will be the inaugural U.S. survey of an artist who, for four decades, has actively worked against the shelf life of facts, objects, and identity by destabilizing (and simultaneously elucidating) the fungible borders between author and audience, material and idea, biography and lived experience.

When Marcel Duchamp asserted, in 1917, that a bicycle wheel or a toilet turned on its head was as much an artwork as a painstakingly crafted painting, he revolutionized art with the readymade and what theorist Thierry de Duve describes as “an attitude.” Decades later, mashing up the open-endedness of John Cage’s performances and the incisiveness of Michael Asher’s institutional interventions, Tiravanija converted attitude into action. In fact, countless people pissed in Tiravanija’s untitled 1996 (tomorrow is another day), a plywood replica of his East Village apartment installed at the Kölnischer Kunstverein in Cologne. Visitors also napped, bathed, and made out. My house is your

house. And what we do in it is art. The host didn’t even have to be there to say so.

It is this snout-to-tail embrace of the everyday that has made the Thai artist a canonical figure and an archival nightmare. Tiravanija’s artworks are often like recipes—so open to substitutions and the chef’s whims that they almost always scrape up against the Ship of Theseus paradox. When the work isn’t pillaging the world’s pantries, travel itineraries, and architecture, it tends to cannibalize itself. Take, for example, Tiravanija’s untitled 2017 (super 8), a piece composed of his earlier Super 8 films.

Out of this tangle of dates and materials, Raymond and Katrib have wrestled the artist’s output into coherent form. They had a running start thanks to archivists Jörn Schafaff and Jan Pfeiffer, who, in the late 2000s, created a fiveway categorization in their quest to organize a pile of work 20 years in the making. Each of these typologies—slogans, replicas, immersive installations, portraits, and stages—appears in the PS1 show. But the curators further distilled the practice into what Katrib calls “two, really two and a half, methodologies.” One of these concerns the part of Tiravanija’s practice that might loosely be called object-focused, including the aforementioned slogans, portraits, and replicas. The second methodology unfolds as a literal stage, where a series of participatory performances will take place. As for the halfmethodology: This is untitled 2011 (558 broome st. the future is chrome), the exhibition’s welcome mat, an immersive replica of the original Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, sans the beer. Instead there are ceramic bottles glazed with palladium

luster—a sober, one-for-one replacement therapy that the artist has grown to favor.

Most people familiar with Tiravanija tend to think of him as a relational aesthete and social practitioner, a teacher with a backpack of tricks and treats swinging between responsibilities and studios in New York, Berlin, and Chiang Mai. This exhibition doesn’t refute the wanderlust thread nor the patrimony of his students (he’s a longtime faculty member at Columbia University’s School of Visual Arts). It does add an interpretation that has been missing: Tiravanija the autobiographer, an immigrant and son of a Thai diplomat trying to make sense of his own narrative as both insider and outsider in a rapidly globalizing world. Perhaps its absence up until now can be accounted for in its prescience. Tiravanija’s diaristic yet flexible forms foreshadow the last decade’s fixation with gluing identity politics onto a slippery mass of exceptions—its failure to account for those individuals shuttling between worlds, as well as work that exploits those cracks in order to make new (w)holes. “I think that Rirkrit’s consistency will be what comes across most,” says Katrib of the exhibition. “The work is ultimately very personal.”

Tiravanija echoes this sentiment when I write to him about the upcoming survey. “It has been difficult,” he says. “I don’t think of my work in one context, in one place. The work has always been as much about the people and the place where and when it was made. But the work has directions; it has a spine of awareness and attentions. Perhaps in the end it’s all biographical, without the ego of one.”

88 culturedmag.com

Portrait of Rirkrit Tiravanija in 2021

Portrait of Rirkrit Tiravanija in 2021

culturedmag.com 89

by Daniel Dorsa. Image courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner.

The Los Angeles–based artist uses bronze, earth, hair, and plant matter to craft works that are at once deeply intimate and existentially out-of-reach.

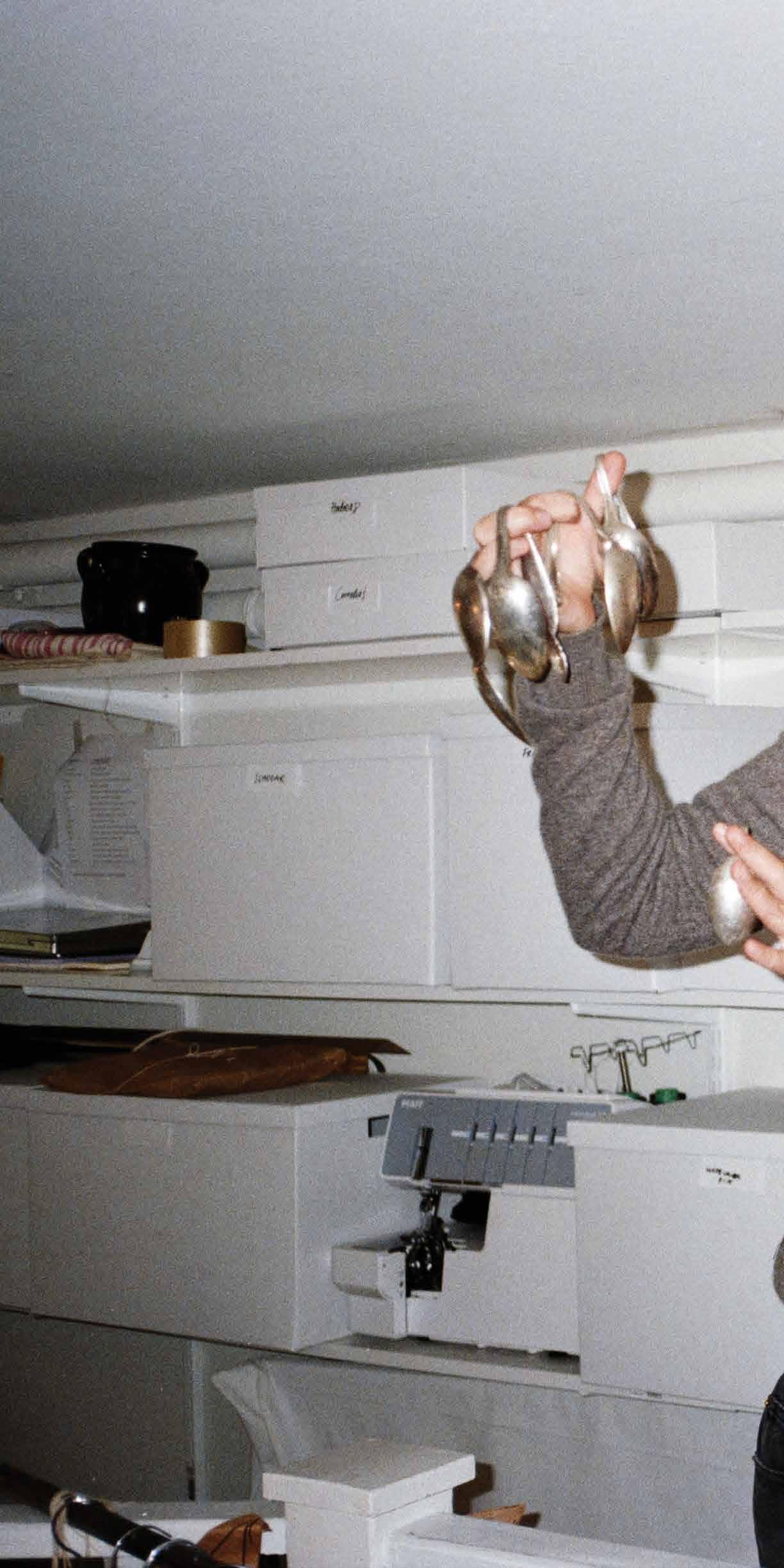

KellyTimeAkashi’s Machine

This fall, her galaxy-spanning practice will be honored with two West Coast exhibitions.

BY CATHERINE G. WAGLEY PHOTOGRAPHY BY BRAD TORCHIA

90 culturedmag.com

culturedmag.com 91

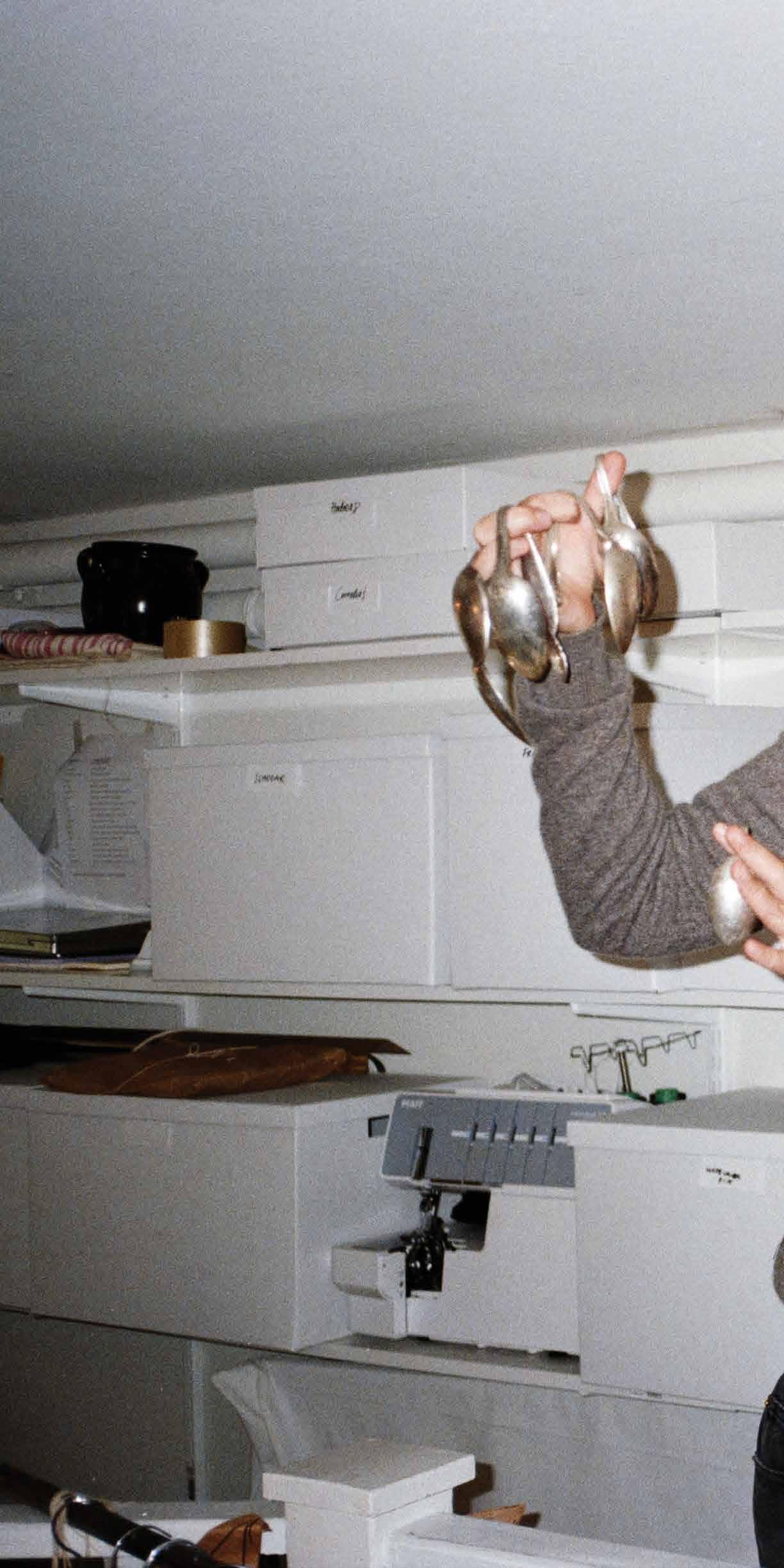

WHEN THE WORLD SHUT DOWN, Kelly Akashi took up stone carving. It was the spring of 2020, and the meditative, outdoor process felt well-suited to an era of isolation. Now, slabs of calcite, sandstone, and marble rest on sawhorses outside her studio, a converted garage in the unincorporated city of Altadena, just northeast of Los Angeles. Inside, there is more evidence of Akashi’s omnivorous appetite for craft traditions, which she uses to make art that manages to be both precise and indeterminate. A floor-to-ceiling shelving unit occupying a full wall of Akashi’s studio holds an array of colorful, pristine glass and bronze objects—snake-like tubes, yawning blossoms, and several expressive replicas of her own hand, a motif in her work.

Many of these pieces will never appear in exhibitions. “I try to be careful not to make any of my studies too precious,” explains Akashi. Some of them end up archived in labeled boxes, a record of the experiments that go on to inform completed artworks. “I always say the best time to make work is when I don’t have a bunch of deadlines,” she notes. “It’s really nice when there’s just no goal.”

In a moment when crushing economic pressures in most international art centers force artists to become results-driven, Akashi’s insistence upon open-endedness feels especially optimistic, as it underscores art’s ability to unfurl less direct, but still potent, modes of meaningmaking. Her circuitous way of working defines “Formations,” the first major exhibition of Akashi’s work, which opens at the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, in September. (It originated at the San José Museum of Art in September 2022 and then traveled to the Frye Art Museum in Seattle.) The show spans the past decade of Akashi’s career and treats her materials—photography, wax, bronze, glass, earth, fossils, medicine, plant matter—as part of a constellation.

In fact, the exhibition feels so coherent that it could be mistaken for a single installation. The golden rope Akashi has used for years drapes over walls, anchoring delicate-looking bronze body parts and glass orbs. Casts of flora bisect slabs of earth, or grow out of dirt mounds on the floor. Human hair extends from glass bowls. “It’s not this linear, dry narrative,” says Akashi. “It’s meandering. But meandering paths create a lot of volume, and loop back on themselves.”

Akashi’s family has deep roots in Los Angeles: Her grandfather ran a business in Little Tokyo, and her father grew up in Boyle Heights before the Japanese American family was forcibly interned during World War II. She grew up around the paintings her mother made in college, though when asked why she became an artist, Akashi often cites a 1996 copy of Spin magazine that featured photographs by Nan Goldin.

“There is an insistence on stories and relationships,” Akashi explained of Goldin’s appeal in a 2022 interview with fellow artist Julien Nguyen, featured in the “Formations” exhibition catalog. This pivotal encounter with contemporary photography led her to study the subject at Otis College of Art and Design, where she graduated in 2006. But, as she told Nguyen, “At some point, I started realizing maybe it was never really about photography.” Like Goldin, Akashi was interested in collecting, archiving, and connection-making; photography was just one way to pursue these urges.

By the time she received an MFA from the University of Southern California in 2014, Akashi had begun working with wax, bronze, and glass. The wax came first—during her first semester of graduate school, when her mother taught her candle making—and led her to make wax replicas of her own hands. A friend who worked at a foundry offered to cast them in bronze free of charge. “It’s a terrible thing he did for me,” she jokes,

“because now I’m hooked.” Glass came next, and over the years, Akashi has taken multiple trips to Pilchuck, an epicenter of the American studio glass movement. She spent the summer of 2022 learning glass-blowing techniques in Murano, Italy, a hub for glassmaking since the 1200s.

For Akashi, these ways of working are all extensions of the same impulse: to explore time and our inability to control it. The sculpture Pincer, 2017, included in “Formations,” consists of a pearl-hued, shell-like basin with small glass balls interrupted by disembodied bronze fingers at the bottom. This work helped Akashi begin to grapple with nonhuman perspectives and inspired her to research fossils. She has always used her own figure—through casts of body parts and materials collected from her life—as a threshold. With Pincer, she started to think about how to “situate the human timeline on these other timelines that are just as valid.”

In 2020, she traveled to Poston, Arizona, to visit the remains of the camp where her father had been interned in the 1940s. She knew that internees planted trees during their time there. “They’re these last witnesses of that time,” she says. “That’s why I wanted to go there initially, to see if there were any trees.” There were, and she made bronze casts of the branches she collected. In “Formations,” these sculptures lie across large pedestals of rammed dirt, intended to make viewers feel like they are immersed in the earth.

Over the past year, Akashi has become increasingly interested in outer space. So when Shamim M. Momin, director of curatorial affairs at the University of Washington’s Henry Art Gallery in Seattle, asked if she wanted to collaborate with any department at the university for an exhibition opening the week after “Formations,” Akashi suggested astronomy. In collaboration with astrophysicist Tom Quinn, she has been working on a simulation that shows the merger of the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies, which scientists predict will happen in approximately 4.5 billion years. In the simulation, the galaxies cross each other and then, propelled by gravitational forces, sling back and meld. “It’s so romantic and horrifying at the same time,” she says. “There’s something about getting people to see things that aren’t for us. They’re just things happening in the universe.”

92 culturedmag.com

culturedmag.com 93

Kelly Akashi in her Altadena studio.

Pooches-41©KáriBjörn

Explore the role our furry (and feathered) friends have played in culture and how they stand in as representations of status, power, loyalty, compassion and companionship through the perspectives of 24 global photographers.

OPENING

SEPT 22

GET

TICKETS

October 20 - 22, 2023

Grand Palais Éphémère

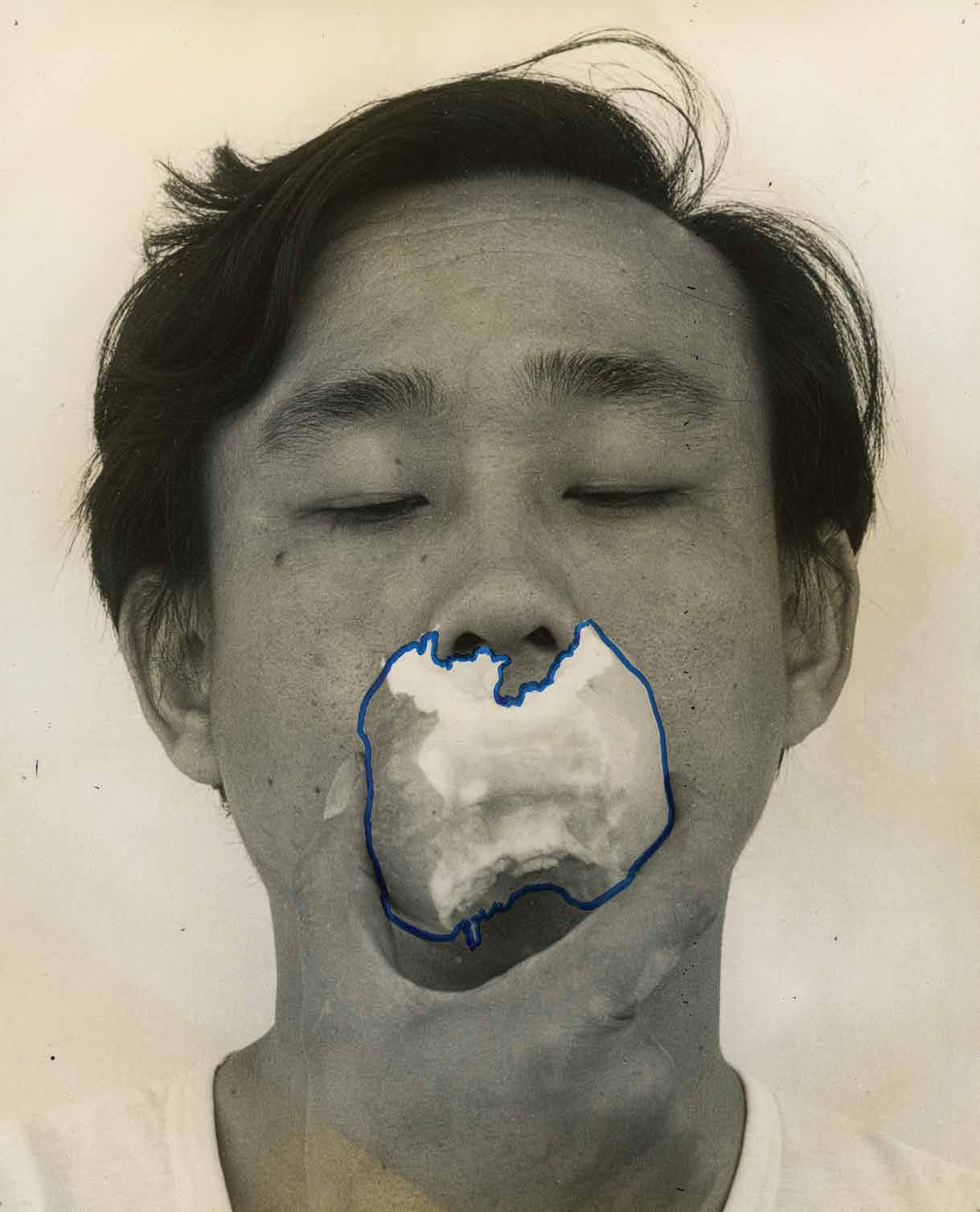

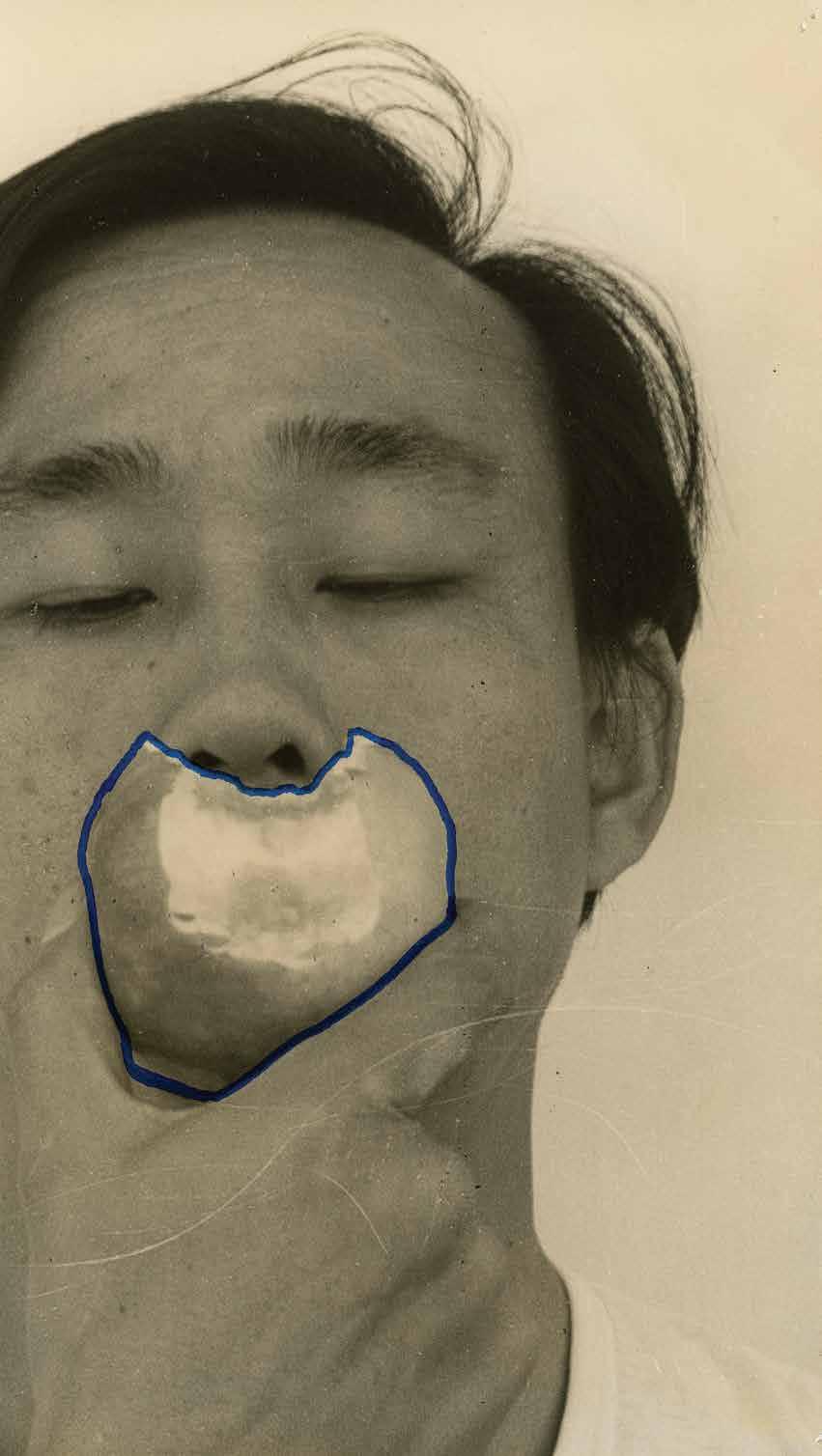

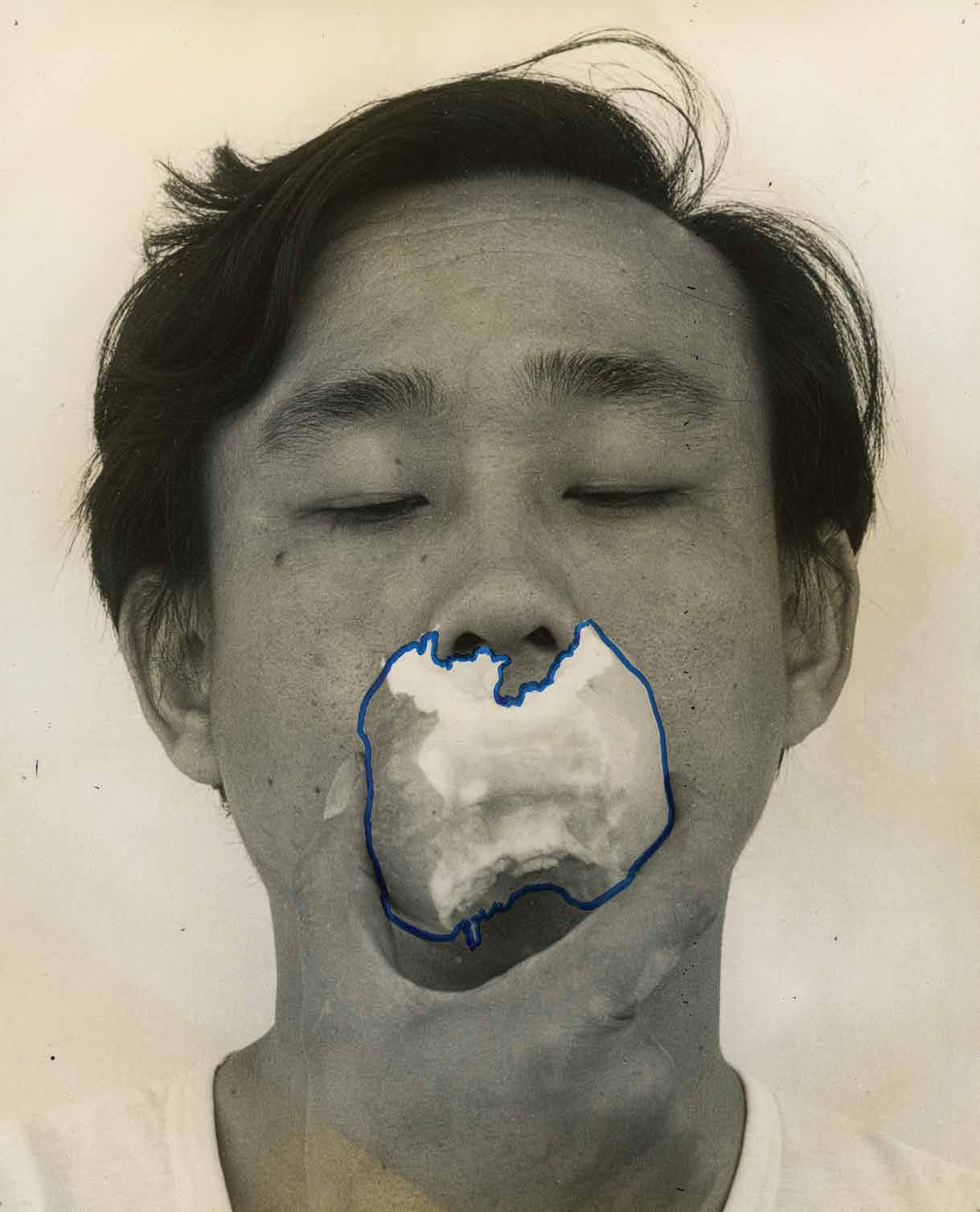

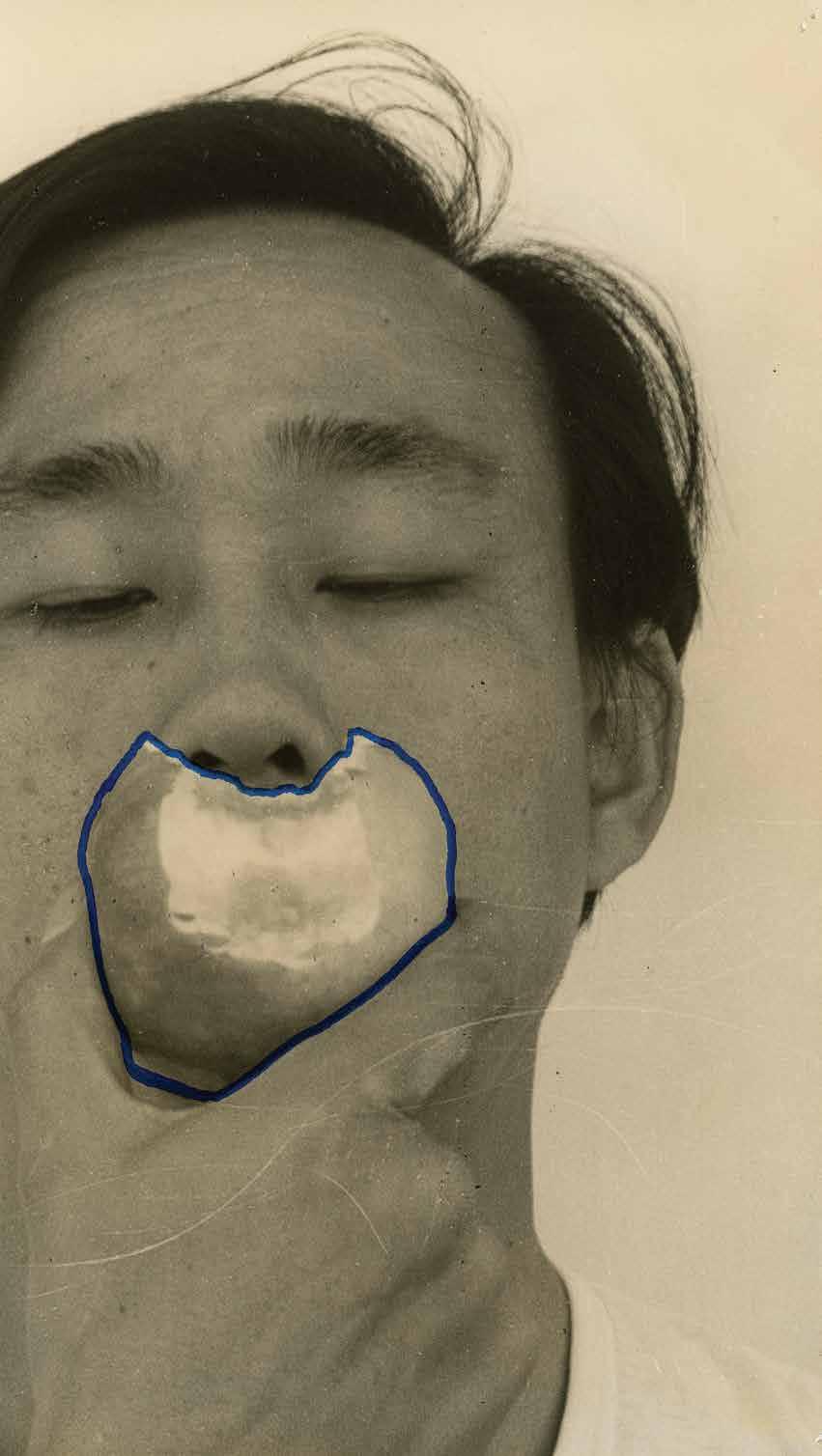

Sung Neung Kyung, Apple, 1976 (detail). Seventeen gelatin silver prints (framed) with marker pen, each 9 7/16 × 7 5/8 in. (24 × 19.3 cm). Daejeon Museum of Art. © Sung Neung Kyung.

Photos: Jang Junho (image zoom)

Sung Neung Kyung, Apple, 1976 (detail). Seventeen gelatin silver prints (framed) with marker pen, each 9 7/16 × 7 5/8 in. (24 × 19.3 cm). Daejeon Museum of Art. © Sung Neung Kyung.

Photos: Jang Junho (image zoom)

Young: Experimental

in

1960s–1970s

Only the

Art

Korea,

September 1, 2023–January 7, 2024

Tickets at guggenheim.org

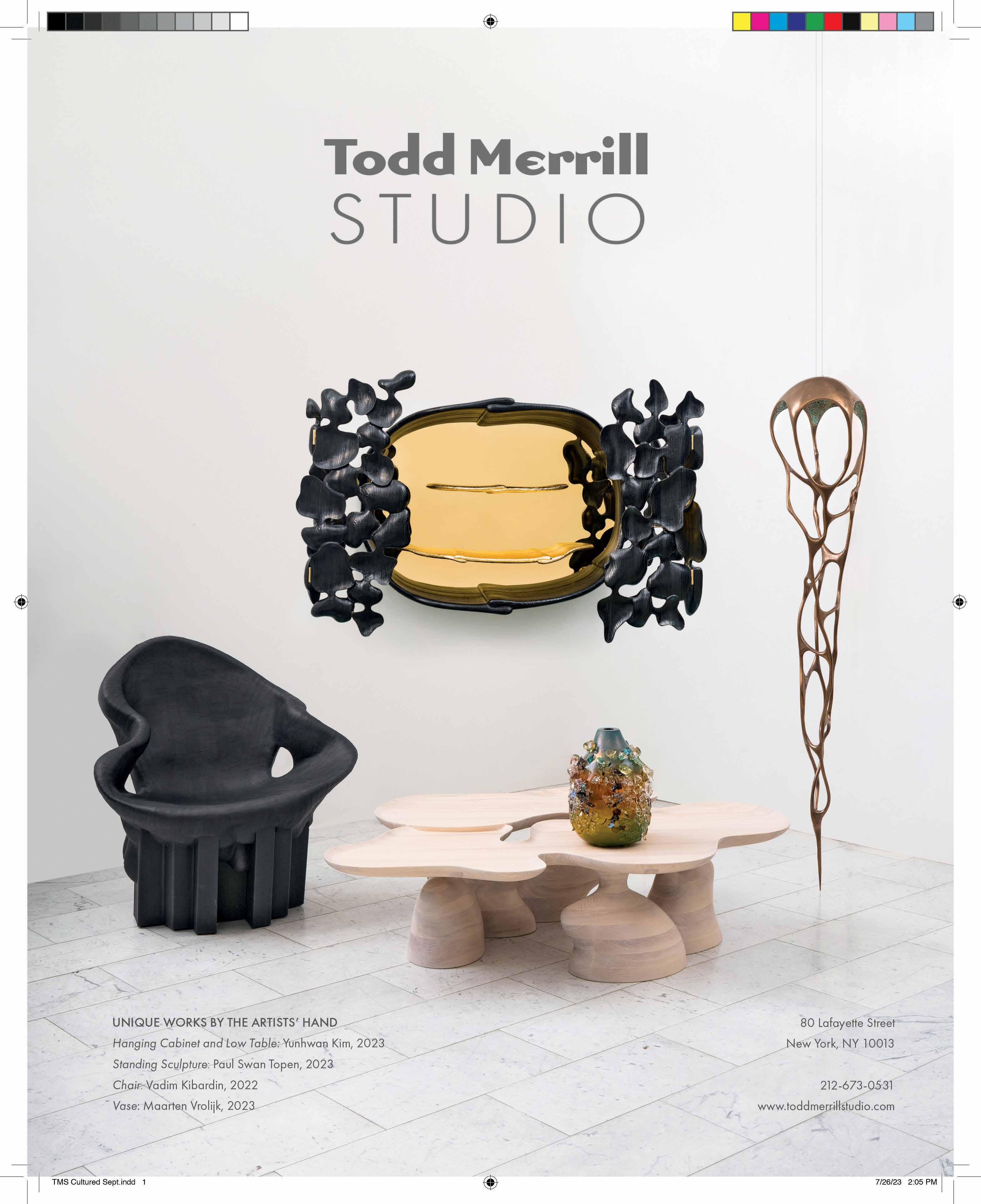

After Years of Searching, White Cube Has Found a Home in New York. Just Don’t Call It an Outpost.

THE ANNOUNCEMENT that White Cube would open its first New York gallery this year was met with nods, not gasps, by art industry insiders. More surprising was that the London-founded gallery had taken so long to plant a permanent flag across the pond.

“We’ve been talking about New York since I joined 17 years ago,” says Susan May, the gallery’s global artistic director, with a laugh. She points to White Cube’s slow, steady expansion across the U.S. in recent years: the 2018 opening of an office in Manhattan; the launch of off-site exhibitions in Aspen, Colorado that same year; and finally, the 2020 opening of a seasonal gallery in West Palm Beach, Florida.

When asked why Jay Jopling, White Cube’s founder, hadn’t pulled the trigger on a New York home until now, May says it came down to location. “The key thing was really to find the right space,” she says.

The British gallery will open its first permanent U.S. branch this October with an inaugural group show.

BY TAYLOR DAFOE

The wait was worth it. On Oct. 3, the gallery will open inside a former bank building on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, a stone’s throw from Central Park and blocks from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Guggenheim, and the former Whitney Museum building recently purchased by Sotheby’s. White Cube New York boasts three floors and 8,000 square feet of space, most of which will be dedicated to exhibitions. “There were a lot of locations in consideration,” says Caspar Jopling, White Cube’s director of strategic development and the founder’s nephew. One major challenge: The gallery wanted a site that hadn’t previously housed an art organization. “It’s a tabula rasa,” notes May. “It doesn’t have anybody else’s imprint.”

That a gallery named White Cube would be so picky about space is ironic. Then again, Jopling knows the importance of location more than most. In 1993, the then-upstart dealer scored a five-year, rent-free lease on a space in London’s tony St. James’s neighborhood. What distinguished Jopling’s outfit from other, stuffier spots in the West End was a penchant for of-themoment art and a novel policy on how it would be shown: No artist would ever exhibit more than once. Over the next eight years, White Cube played host to some of the era’s best talents, including Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst, and Gavin Turk.

The business has only grown since. Additional London branches opened in 2000, 2006, and 2011. A Hong Kong outpost came in

2012, followed by a Paris gallery in 2019, and one in Seoul earlier this year. (White Cube also operated a São Paulo space from 2012 to 2015.) Along the way, the gallery let go of its “one artist, one show” rule and built a stable of some 60 international artists, including Mona Hatoum, Anselm Kiefer, and Doris Salcedo.

White Cube’s newest arm will open just in time for its 30th anniversary. For Courtney Willis Blair, the gallery’s newly named U.S. senior director, all that history is top of mind. “For me, it’s really about the foundation of White Cube— what White Cube has been and what it continues to be,” she says. “How do we bring that to New York and then add on top of it?”

A former partner and senior director at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, Willis Blair developed a reputation for championing young, rigorous artists with strong points of view. Nine months into her new job, she has already put her stamp on White Cube’s roster, helping to recruit the Philadelphia-based interdisciplinary artist Tiona Nekkia McClodden, with whom she worked at her former gallery.

McClodden is one of several artists included in “Chopped & Screwed,” the group show that will inaugurate White Cube’s New York space this fall. Taking its name from the down-tempo, narcotized brand of hip hop popularized in 1990s Houston, the exhibition “looks at how artists are using a methodology of sourcing, distorting, and slowing down as a means to be transgressive, and to really think about the subversion or the dismantling of systems of power and systems of value,” explains Willis Blair. Artists like David Hammons, David Altmejd, and Julie Mehretu—along with others who are not represented by White Cube—will fill out the exhibition.

The show reflects both Willis Blair’s interests and something more: a distinctly American sensibility that is budding under her direction. It also shows the trust that Jopling has in his new home and hire. “This is not an outpost,” says May. “This is a major gallery for us. And it’s a major focus for us in terms of White Cube’s direction.”

98 culturedmag.com

Portrait of Courtney Willis Blair by Myesha Evon Gardner. Courtesy of White Cube.

“For me, it’s really about the foundation of White Cube— what White Cube has been and what it continues to be.

How do we bring that to New York and then add on top of it?”

—Courtney Willis Blair

David Hammons, The New Black , 2014. Painted wood (78.5 x 19.5 x 26 cm) | 30 7/8 x 7 11/16 x 10 1/4 in. © David Hammons. Photo © White Cube (Patrick Dandy).

culturedmag.com 99

Our rugs lie lightly on this earth. ARMADILLO-CO.COM NEW YORK LOS ANGELES SAN FRANCISCO SYDNEY MELBOURNE BRISBANE

The Global Forum for Twentieth and Twenty-First Century Collectible Design

October 18–22, 2023/ Paris, France/ @designmiami #designmiami designmiami.com

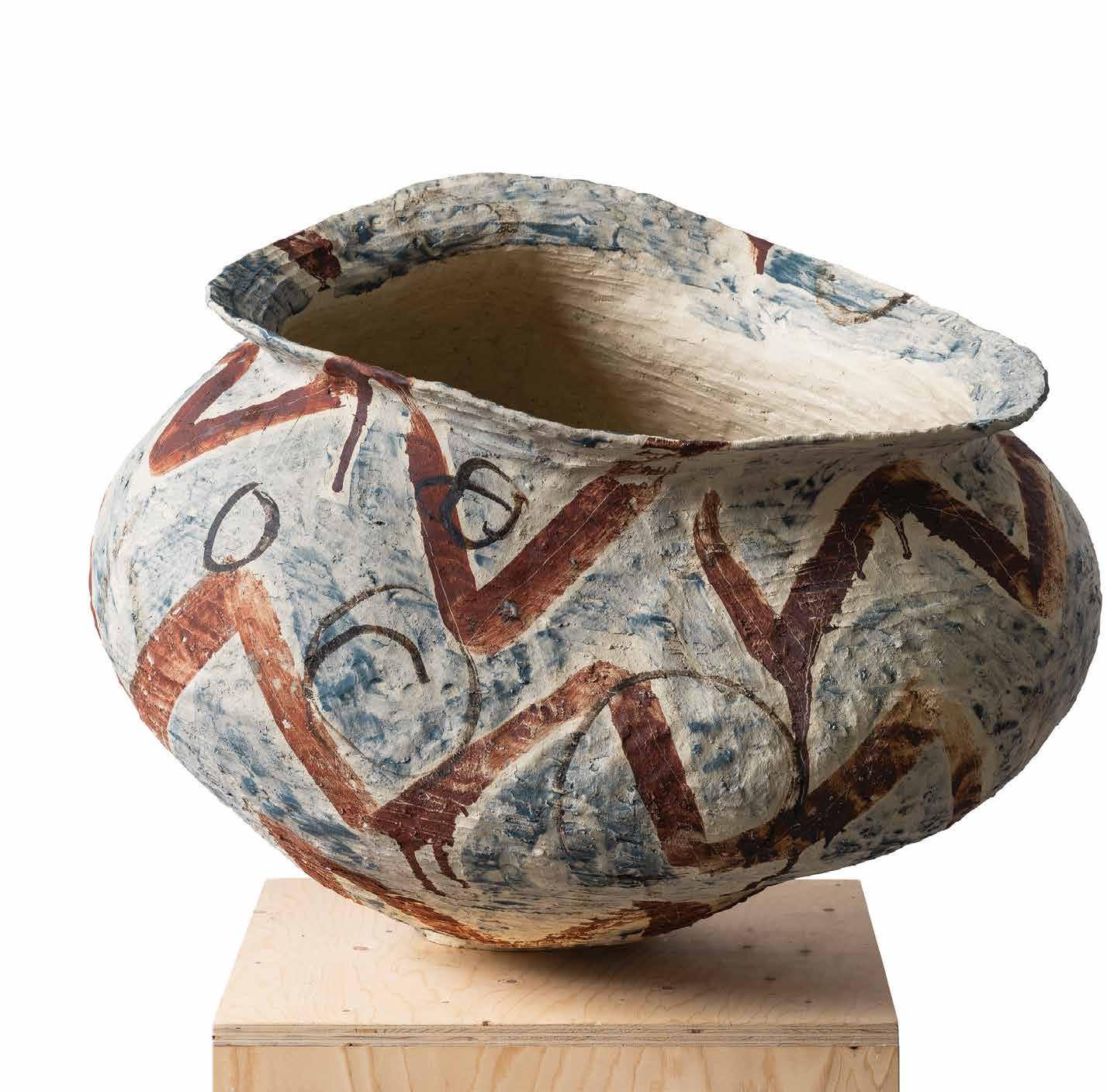

KAZUNORI

HUGARD & VANOVERSCHELDE/

HAMANA, 2022/ COURTESY OF PIERRE MARIE GIRAUD/ PHOTO COURTESY OF

thesalonny.com | @thesalonny Produced by Sanford L. Smith + Associates Image courtesy of Galerie Mathivet November 9–13, 2023 Park Avenue Armory New York City TICKETS AVAILABLE NOW

fernandowongold.com

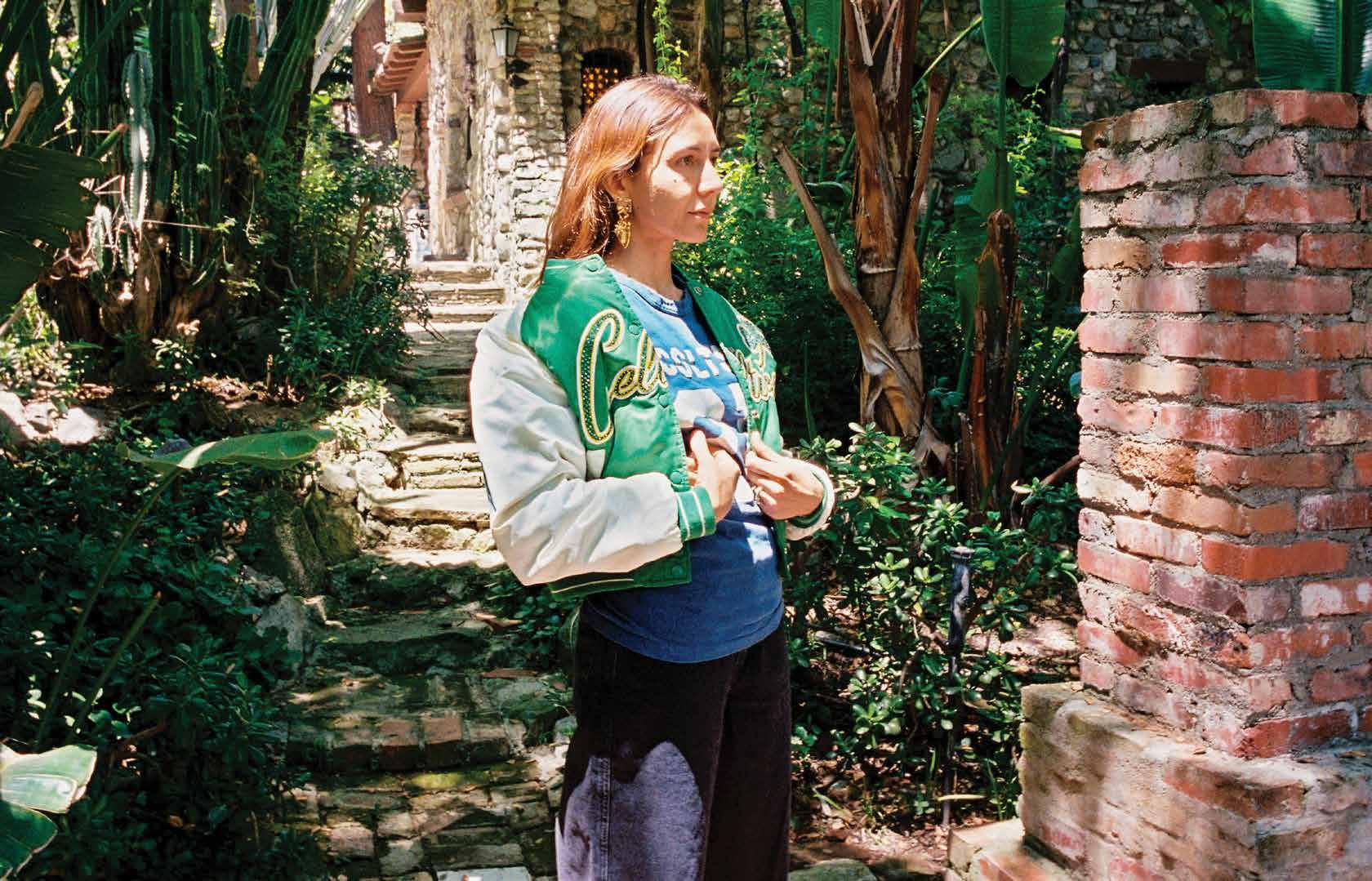

WHETHER ON THE ART-FILLED WALLS OF HER WEST VILLAGE HOME, OR IN THE FALL COLLECTION OF HER NAMESAKE CLOTHING BRAND, VERONICA DE PIANTE WEAVES TOGETHER SUBTLE REFERENCES FROM HER GLOBAL UPBRINGING TO MESMERIZING EFFECT.

By Ella Martin-Gachot

THE FOREIGN AND THE FAMILIAR

104 culturedmag.com

Photography by Björn Wallander

culturedmag.com 105

Gordon Parks, Ingrid Bergman at Stromboli, 1949; Arthur Leipzig, Subway Lovers, 1949; Bob Gruen, Mick Jagger with Guitar – Recording Studio, 1972

IN HIS 1750 WORK La Pamela, Venetian playwright Carlo Goldoni writes, “The world is a beautiful book, but of little use to him who cannot read it.” Veronica de Piante first encountered the godfather of the modern Italian comedy as a teenager studying for her A-levels in the United Kingdom. Today, the designer of her eponymous ready-to-wear line is sipping tea from a Snoopy mug in her sprawling West Village home, pining for a visit to the Venice of Goldoni’s era.

De Piante is no stranger to a suitcase. Born in Milan to an Argentinian mother and Italian father, the designer moved to Bahrain with her family as a child. Later, a career in media sales brought her to Lebanon, Nigeria, Egypt, and the Dominican Republic. This global fluency has made de Piante a deft translator—though she chooses to work with textiles over text.

The designer founded her brand, which is already carving out a niche in the crowded independent fashion landscape with sumptuous yet modern garments, in 2022—but de Piante traces its roots back to the mid-2010s. In 2013, Roberta Ventura, founder of the Social Enterprise Project in Jordan and a friend of de Piante’s, asked if she’d consider collaborating on a line of beachwear. Ventura’s ethical fashion and homeware line is crafted by artisans based in northwest Jordan’s Jerash camp, home to over 30,000 Palestinian refugees. It was then that the wheels began to turn for de Piante, who was still working in media sales. “I started to think, Well, how would I translate this into something more relevant to me? ” she recalls. “Because I don’t really wear kaftans.”

A move to New York from Switzerland in 2017, for her husband's work, was the catalyst that finally jump-started de Piante’s foray into fashion. With no formal training, she relied instead on instinct and a trove of personal experiences, juxtaposing nostalgic palettes and textures (think heavy knits, dark velvet, and chestnut and mahogany tones) with the minimalist edge of classic menswear. Aside from a poncho that clearly references her Argentinian heritage, the designer’s influences are mostly discreet. A pair of gaucho pants sourced in Buenos Aires, for example, provided inspiration for a shirt cuff with a long row of buttons. These sartorial footnotes are filtered through memories of family and loved ones. “It has to do with personality,” says de Piante. “I’m inspired by the way someone wears something, the way they make it their own.” She worked with SEP Jordan as well as family-run factories in Italy, New York, and Bolivia to craft the pieces. The fruits of this labor are manifested in the brand’s debut collection, launched last fall.

Cecily Brown, Unfurl the Flag, 2013; Pablo Picasso, Nu Assis, de Profil, 1947; Artwork by Fernand Léger

Rita Ackermann, Mama, Masked and Anonymous, 2021.

Cecily Brown, Unfurl the Flag, 2013; Pablo Picasso, Nu Assis, de Profil, 1947; Artwork by Fernand Léger

Rita Ackermann, Mama, Masked and Anonymous, 2021.

106 culturedmag.com

“IT HAS TO DO WITH PERSONALITY. I’M INSPIRED BY THE WAY SOMEONE WEARS SOMETHING, THE WAY THEY MAKE IT THEIR OWN.”

Creating a sense of home, whether in the form of a garment or a place, is an art that de Piante has perfected over a lifetime in motion. Sitting in the sunlit living room of her West Village townhouse, an 1855 structure originally divided into 12 studio apartments, she recalls her meticulous approach to renovating it—salvaging the structure’s wrought-iron balcony and original tilework, insisting that the windows retain their wavy, hand-crafted look. The resulting interiors feel more Saint-Germain than West Village, filled with design elements and objects that channel a reserved romanticism. De Piante’s art collection speaks the loudest.

In the living room, a Tracey Emin and a Cecily Brown neighbor drawings by de Piante’s three children. “I have to like it,” she insists. “I don’t actually care what it’s worth or who it’s by.” When asked what she likes, specifically, in a collection that includes works by Pablo Picasso, Shirin Neshat, Mirtha Dermisache, and Rita Ackermann, de Piante responds that the work has to

feel alive. She’s also drawn to an irreverent streak that manifests throughout her acquisitions, most of them by woman artists. The works on display complicate classical beauty, and their makers are funambulists who walk a delicate tightrope between nerve and daintiness.

The collection will see new walls soon. De Piante and her family are leaving Manhattan for London in the coming months. Though New York never quite felt like home, it will forever be the city that brought her brand to life, and where she learned that Veronica de Piante had been dubbed “the new name to know” by Net-a-Porter. The retailer will release the line’s key pieces in September, along with a new collection later this fall. “Of course, it’s incredibly flattering,” she says, smiling. “It gives me a lot of encouragement. But it almost feels like they’re talking about someone else. I set out to make beautiful clothes … I just want to keep it authentic. Maybe that means I’ll lose a few retailers, or have three boutiques instead of 10,” she muses. “But they will make sense to me.”

culturedmag.com 107

MAY 18, 2023–JAN. 7, 2024 1600 Peachtree St. NW Atlanta | scadfash.org

Photo courtesy of the artist

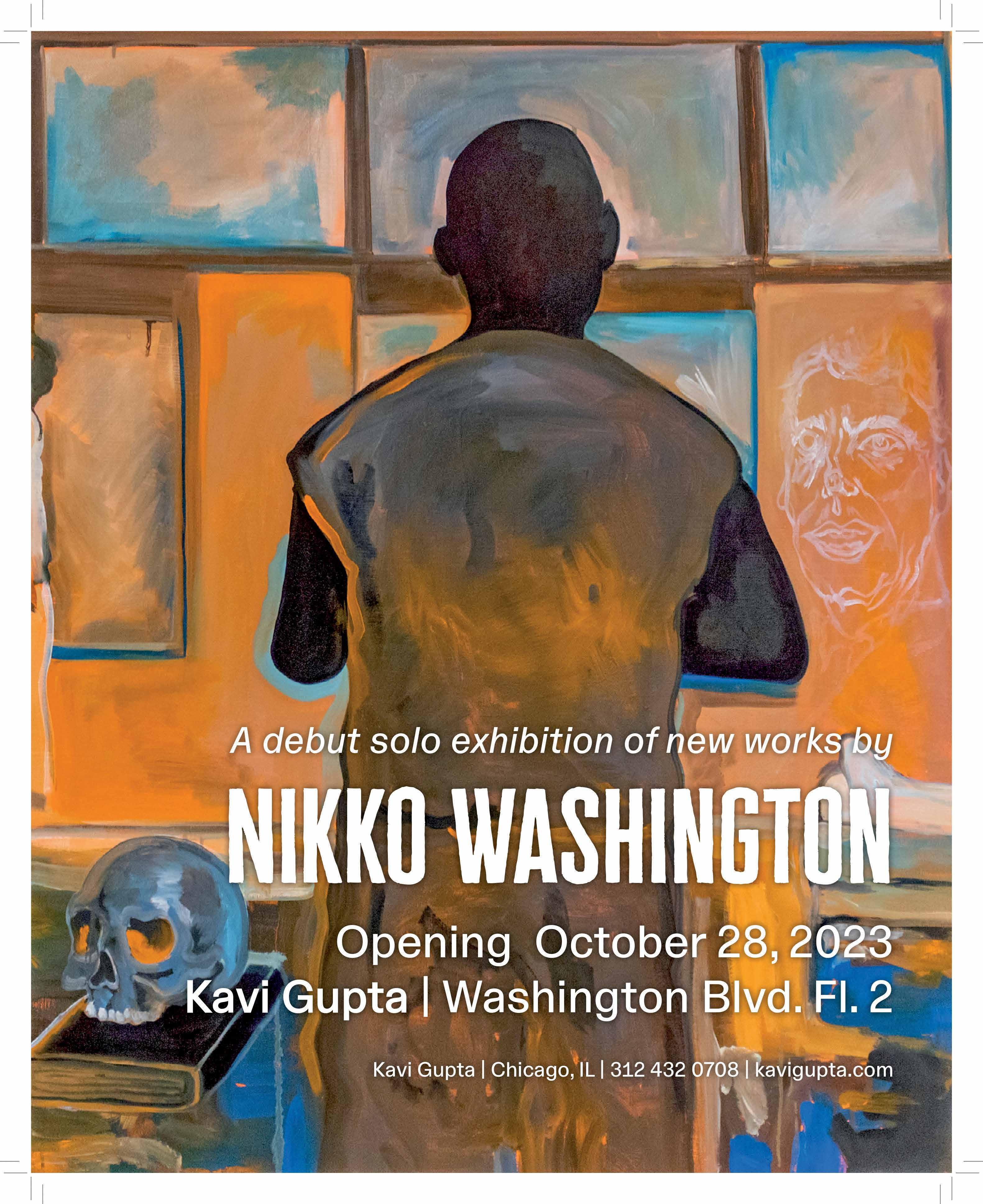

inaugurated Mickalene Thomas Scholarship

Photography by Myles Loftin

Art school is a rite of passage

for many promising talents, but the experience can often feel more like a dry run of the competitive art-world gauntlet than a safe haven for self-discovery and creative evolution. This year, three Yale alumni—attorney Carmine Boccuzzi, arts patron Bernard Lumpkin, and artist Mickalene Thomas—have committed to fostering the latter experience at their alma mater. Boccuzzi and Lumpkin first encountered Thomas as collectors of her work, which was later featured in the traveling exhibition “Young, Gifted and Black: The Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection of Contemporary Art.” It wasn’t long before the trio recognized their shared dedication to nurturing the careers of emerging artists— especially those who are often overlooked by prevailing art world institutions. This July, Boccuzzi, Lumpkin, and Thomas established the Mickalene Thomas Scholarship at the Yale School of Art. The monetary award, a culmination of their shared vision, also offers one student per year the opportunity to benefit from Thomas’s guidance and mentorship. The announcement of the artist’s eponymous scholarship is tied to this month’s opening of “Mickalene Thomas / Portrait of an Unlikely Space,” an exhibition co-curated by Thomas at the university’s art gallery. The show, which runs through the end of the year, juxtaposes pre-emancipation-era portraits of Black Americans with works by contemporary artists. To mark the occasion, the trio reunited for a conversation about building a legacy that honors the past as much as the future.

BERNARD LUMPKIN: Mickalene, you and I are part of an amazing community of artists, curators, educators, writers, patrons, and collectors who champion artists of African descent. We share a mission to elevate these voices in the contemporary art world, each using our own platforms and strengths. You have used your success to provide opportunities for others, which

resonates with me as a patron and collector. I aim to use the visibility I have—through my support of institutions like the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and the Yale School of Art—to inspire others to extend their support beyond merely acquiring work.

CARMINE BOCCUZZI: Bernard has shown me what can happen when you act as an art patron, support younger artists, and learn about how the world of today is tied into past historical moments and people. It’s enriching to be around people who care about art and art history, like when we went to see Mickalene speak at MoMA about the Matisse painting The Red Studio [1911]. You have both helped me think about building community and being in dialogue with other collectors.

MICKALENE THOMAS: It begins with likeminded people wanting to address a void. As Toni Morrison says, if you don’t have that place, create it yourself. Making space is vital to my practice, because creating art simply isn’t enough. I want to see others in my community grow, too. I never felt comfortable being the only one at the table. I want dialogue with peers—like Derrick Adams, Wangechi Mutu, Kehinde Wiley, and Clifford Owens—who also navigate these spaces and support one another. When I reached a point of influencing institutions, I realized I could use my platform to educate artists about community. No one wants to stand alone.

This instinct to make space is something we share. I first encountered you both through the Studio Museum in Harlem, and I was inspired by your efforts. Your support was never ostentatious—it was stealthy and genuine. You were always welcoming a diverse range of artists to your homes and championing our work, regardless of our career stage.

LUMPKIN: For you, art is not just a practice—it’s a way of advocating for change. You’ve engaged institutions like Yale to accomplish your wider vision of what an artist can do: this idea of the artist as citizen, advocate, activist. You’ve set an amazing example for a new generation of artists.

When Yale approached us, we were already supporting the School of Art program through scholarships and service on its task force. I had advised Yale on another project that Mickalene did there, a mural in one of the new residential colleges in honor of Pauli Murray.

A SEAT AT THE TABLE

110 culturedmag.com

With the newly

at the Yale School of Art, collectors Carmine Boccuzzi and Bernard Lumpkin are offering one lucky student a chance to become the artist’s newest mentee.

BOCCUZZI: The mural that Mickalene did at Pauli Murray College was so meaningful to me, because Bernard and I met as students at Yale. Murray got her higher law degree at Yale Law School, and I went to Yale Law School, too. Seeing what Mickalene did, which is so gorgeous and stunning, was a revelatory moment.

THOMAS: It’s interesting how life comes full circle. I had discovered Pauli Murray prior to being invited to create this mural, because I was researching African American women activists who were dealing with gender equality. She seemed like this nonbinary force, an activist and scholar who worked through the Civil Rights Movement. The fact that she became the first African American person to have a college in her name at an Ivy League school seemed like a great opportunity to celebrate her. She was a shapeshifter far ahead of her time—she was even an Episcopal priest. I consider her a distant mentor, influencing how I envision my own legacy.

LUMPKIN: That’s also reflected in the exhibition you’re curating at the Yale University Art Gallery this fall: “Mickalene Thomas / Portrait of an Unlikely Space.” Yale knew of our special relationship with you. The opportunity to join forces and support emerging artists, the university’s art program, and the mission of elevating artists of African descent felt unmissable to us. I hope it sets an example for other patrons and collectors to impact future generations of artists by supporting their education.

THOMAS: There are many things I imagined accomplishing in my life, but a scholarship was not on my list. When I received the phone call, I was speechless. It’s beyond the idea of a legacy. It validates my thoughts, actions, and beliefs. I know the struggles I had in school, so I hope other patrons follow your lead, because students need space to create without stress and compromise. The scholarship is a concentrated engagement with one student over their tenure at Yale. I’ve extended my mentor services to the recipient while they’re in school, and after school through my platform Pratt>FORWARD [a program at the Pratt School of Art]. The scholarship recipient will always have a home in me, and can rely on my team as advocates. Artists often find themselves in conflict because they lack this type of support to guide them.

LUMPKIN: What did mentorship look like for you as a young artist?

THOMAS: My mentor was Rahimah Lateef. She was a collector, friend, and supporter who introduced me to Carrie Mae Weems’s work. This became instrumental and transformative in my practice. Rahimah was also my first patron. When she needed to sell some work, she gave it to my

gallery, Lehmann Maupin. Bernard and Carmine ended up with this painting, Mary J. Me [2002], showing the serendipitous connections in my life.

LUMPKIN: We’re in a moment with increased visibility for Black artists—there’s more support and infrastructure. Yet we’re aware that we’re building for the next generation without knowing whether the world will be as receptive. Regardless, we will always be creating space and opportunities. While I often lead the conversation, Carmine’s partnership is integral. The best things happen with teamwork, and Carmine, your support and advocacy is invaluable.

THOMAS: You both have carved out space in monumental ways that enable artists like me to continue to achieve what we set out to do. Octavia Butler’s words come to mind: “All that you touch / You Change. / All that you Change / Changes you. / The only lasting truth / Is Change.” I know that the person who receives this scholarship will be incredible. They’ll take this opportunity and