NORTH AMERICA EUROPE ASIA CARIBBEAN OCEANIA

NORTH AMERICA EUROPE ASIA CARIBBEAN OCEANIA

June/July/August 2024

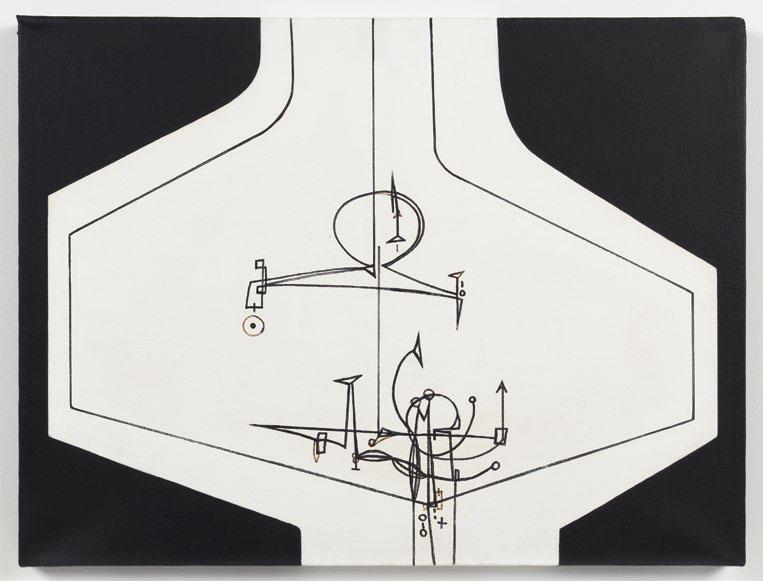

FOR MATTHEW BARNEY, ART-MAKING IS A CONTACT SPORT

The visionary artist is embarking on a world tour with works springing from his 2023 film, Secondary.

A RISK, NOT A RECIPE

This summer, two European shows secure artist Martha Jungwirth’s status as a singularly deft articulator of the painterly process.

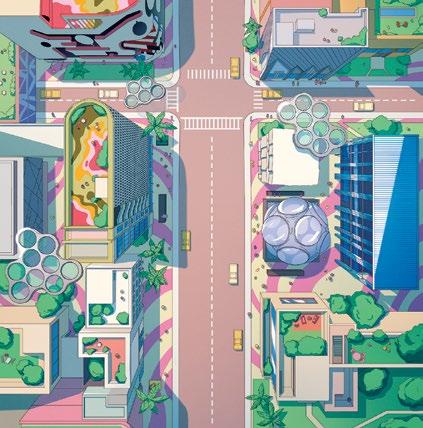

NINA CHANEL ABNEY’S LABYRINTH OF FALSE COMFORTS

With her most colossal show yet on view at Jack Shainman Gallery’s The School through October, the artist is cementing her place in the contemporary canon.

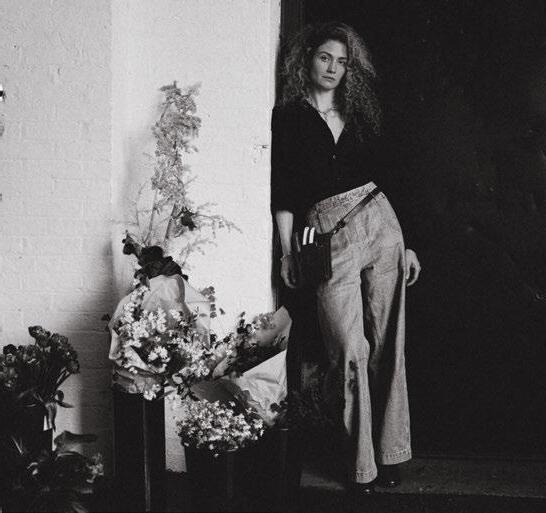

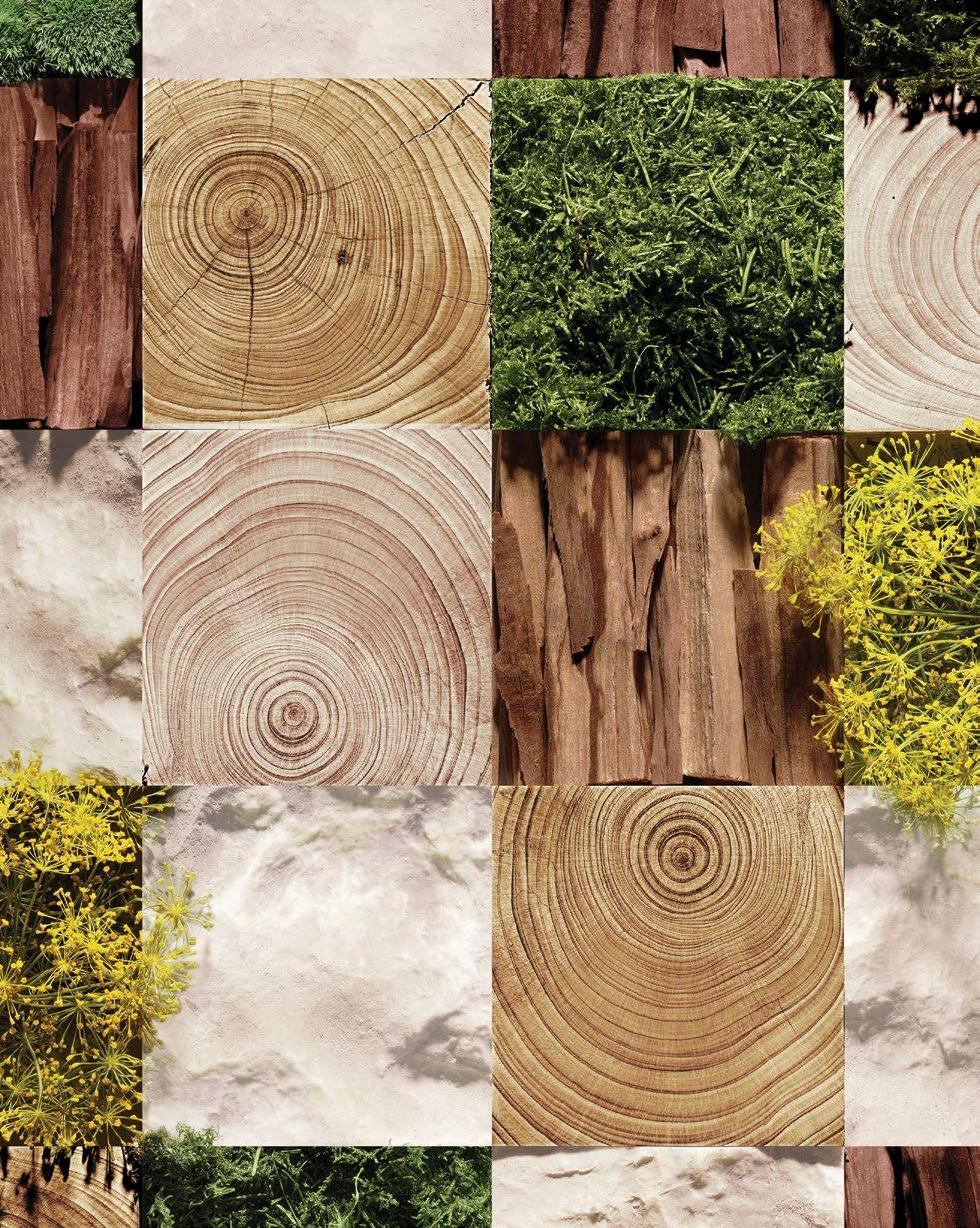

HAVE YOUR FLOWERS AND EAT THEM, TOO

Florist Alex W. Crowder’s botanical “laboratory,” Field Studies Flora, pays tribute to childhood afternoons spent in nature.

58

A GRAND VISION COMES TO LIFE: CIPRIANI

With the construction of a gleaming new tower in Brickell, Mast Capital CEO Camilo Miguel Jr. leaves a lasting mark on his coastal hometown.

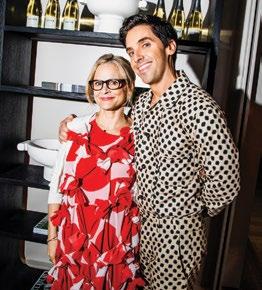

IT’S A MARTHA STEWART SUMMER

The patron saint of good living offers CULTURED ’s Design Editor-at-Large, Colin King, a peek inside her seasonal rituals.

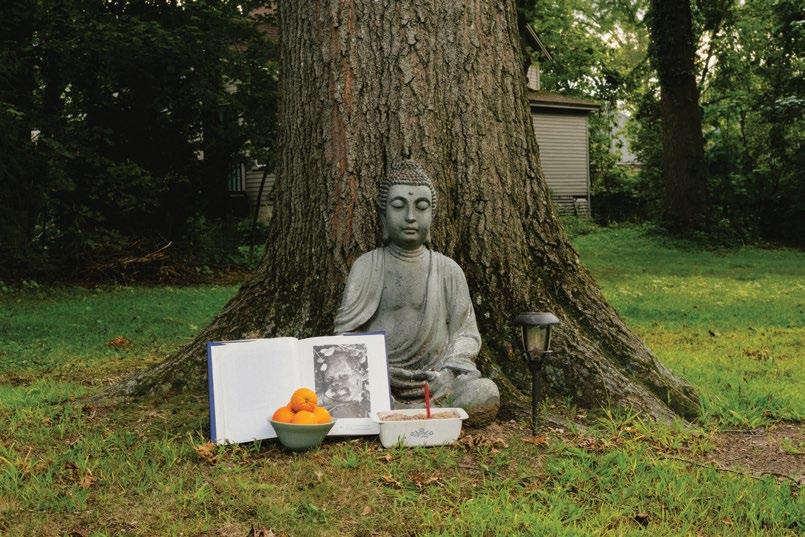

OBSESSIONS: DURGA CHEW-BOSE

For this issue, one writer selects a treasured cultural artifact and holds it up to the light, reflecting on the revelations it has sparked and the nostalgia it conjures.

60

66

THE CULTURED REPORT

Look back at the blowout celebration of the inaugural CULT 100 issue, with a little help from our friends.

LOUIS VUITTON STEPS INTO THE LIGHT

The house’s Master Perfumer Jacques Cavallier Belletrud teamed up with Pharrell Williams to create LVERS, a bright scent that pays homage to sunshine.

68

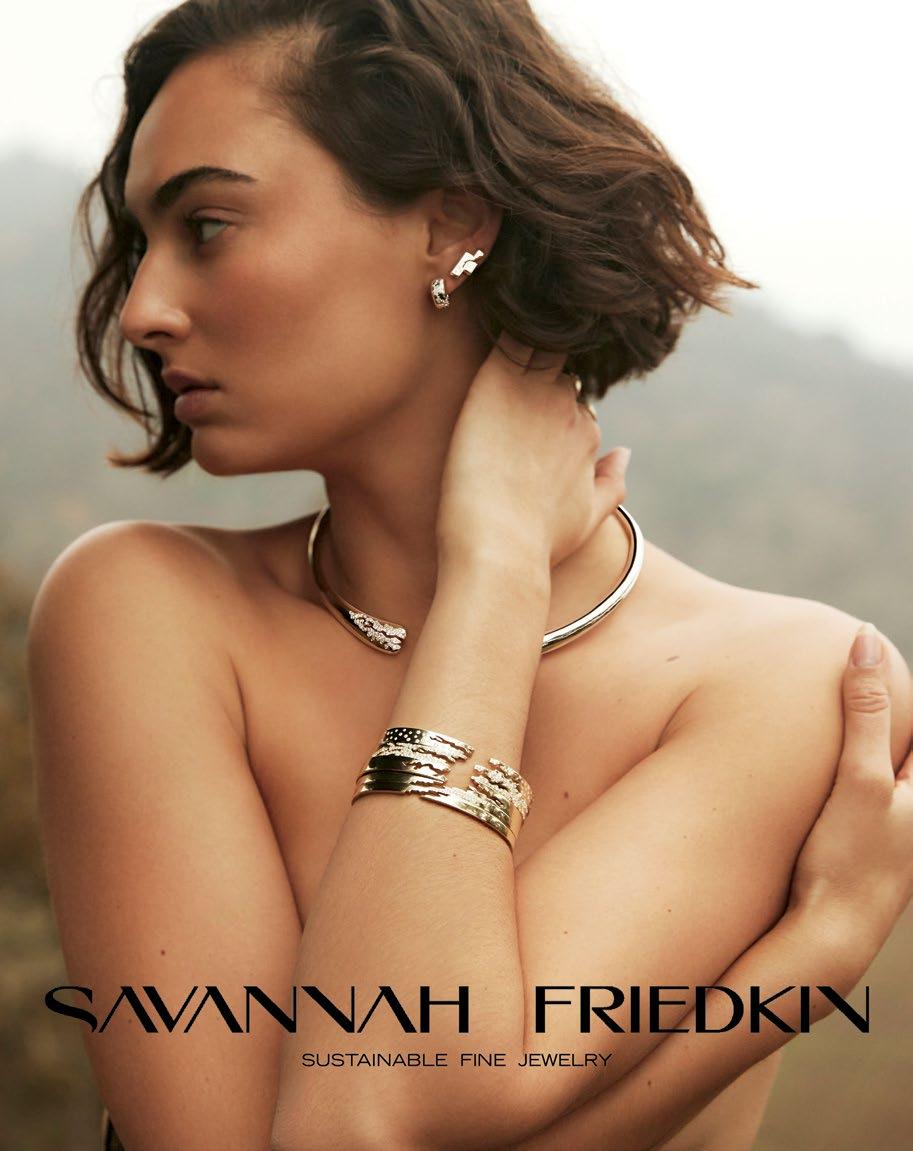

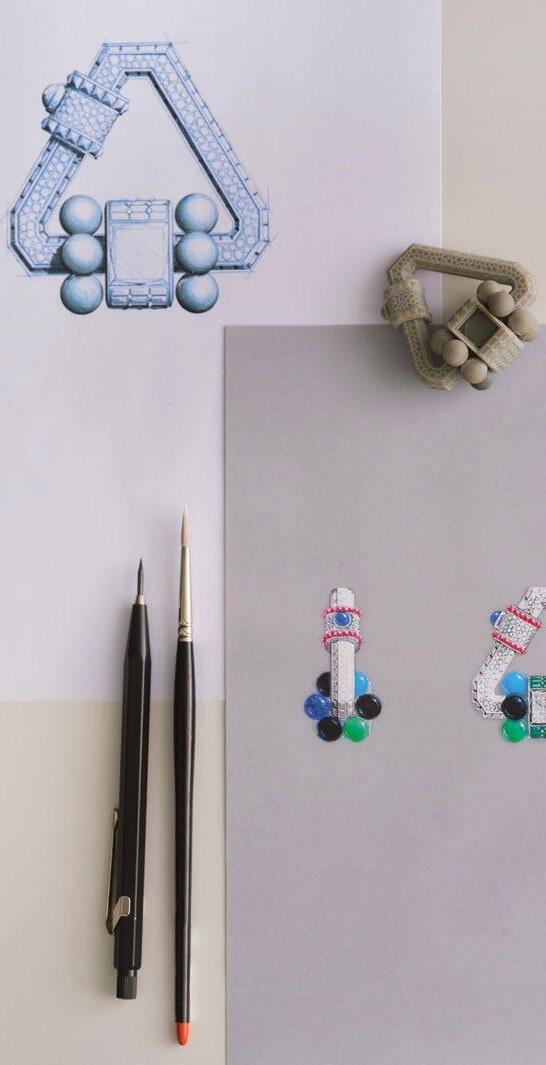

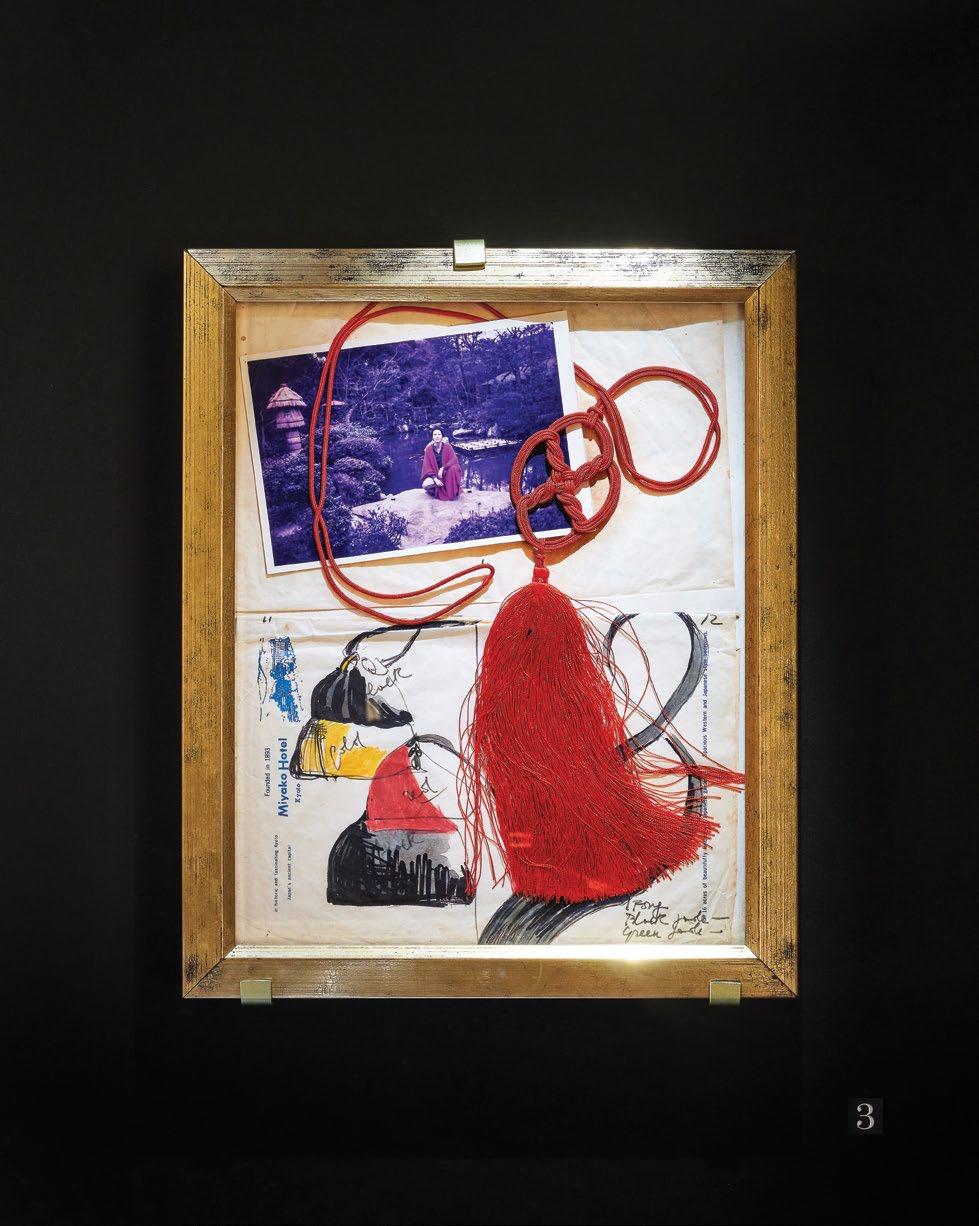

JEWELRY AS OBJECT AS JEWELRY

Jewelry is imbued—perhaps more than anything else we wear—with potent emotional power. These designers are blurring the line between wearable art and treasured object.

June/July/August 2024

76 78 82 84

BEAUTY IN THE BROKEN PIECES

When jewelry designer Savannah Friedkin founded her eponymous brand this spring, she set her sights on two goals: environmental sustainability and personal significance.

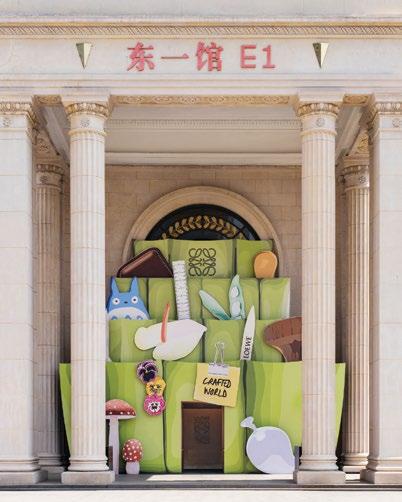

IN LOEWE’S FIRST-EVER EXHIBITION, CRAFT IS KING

The Spanish fashion house’s traveling proto-retrospective, “Crafted World,” charts its history with a cheeky, detail-oriented eye and a strong dose of optimism.

A FRESH TAKE ON A TIMELESS MEXICAN ART FORM

Seven years since its founders crafted their first batch of tequila for a friend’s wedding, LALO remains committed to being the drink that brings friends together.

STANDING ON THE PRECIPICE

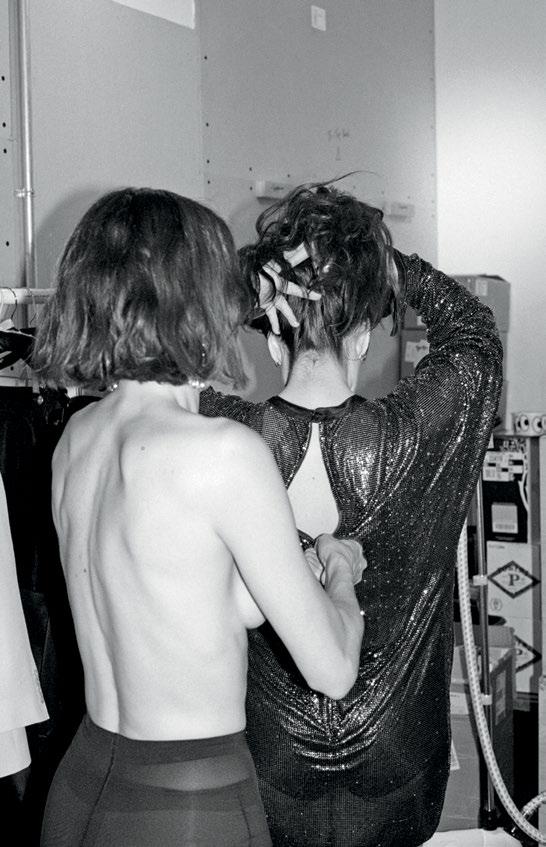

In the whirlwind year since Steve O Smith debuted his master’s thesis collection, his designs have made the red carpet rounds. Up next? Learning to stay still.

90

94

98

MEET THE REGULARS

Five New Yorkers reflect on how they attained the city’s most coveted accolade.

THE BELLY OF THE BEAST: WHERE THE ART WORLD EATS

Podcasting It-boys Nate Freeman and Benjamin Godsill share an insider’s list of establishments—from the down and dirty to the white glove—that feed the art world.

ART CRITICISM IS IN CRISIS. THESE THREE WRITERS AREN’T GIVING UP

A trio of writers representing three different approaches to criticism compare notes on the state—and the promise—of the discipline.

103

116

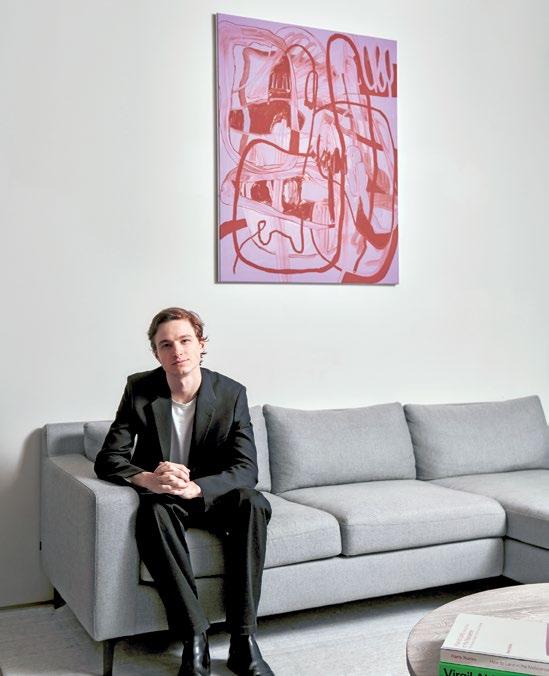

YOUNG COLLECTORS 2024

Art collecting is, above all, an act of faith. The 10 individuals on CULTURED’s seventh annual Young Collectors list show us what comes after that leap.

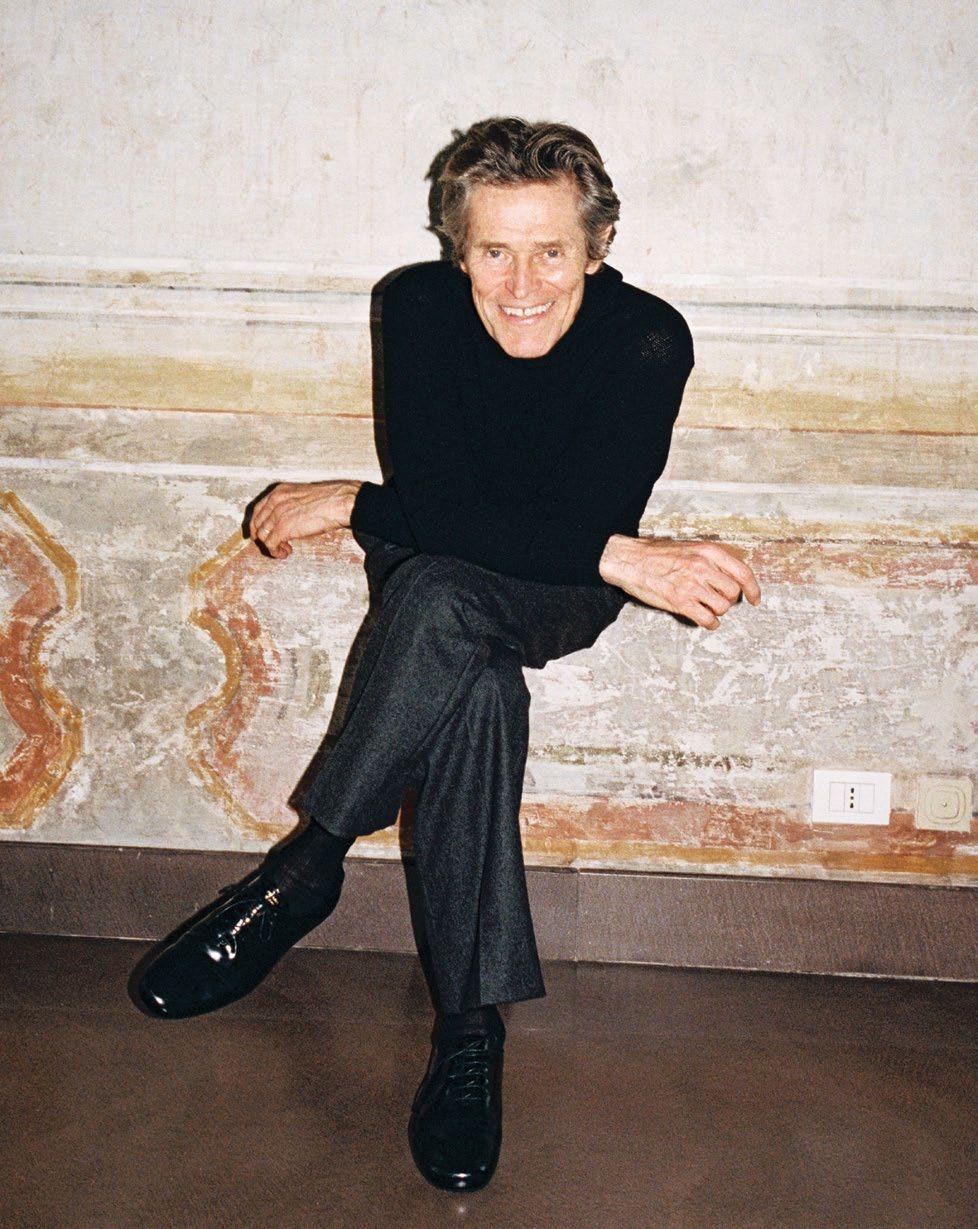

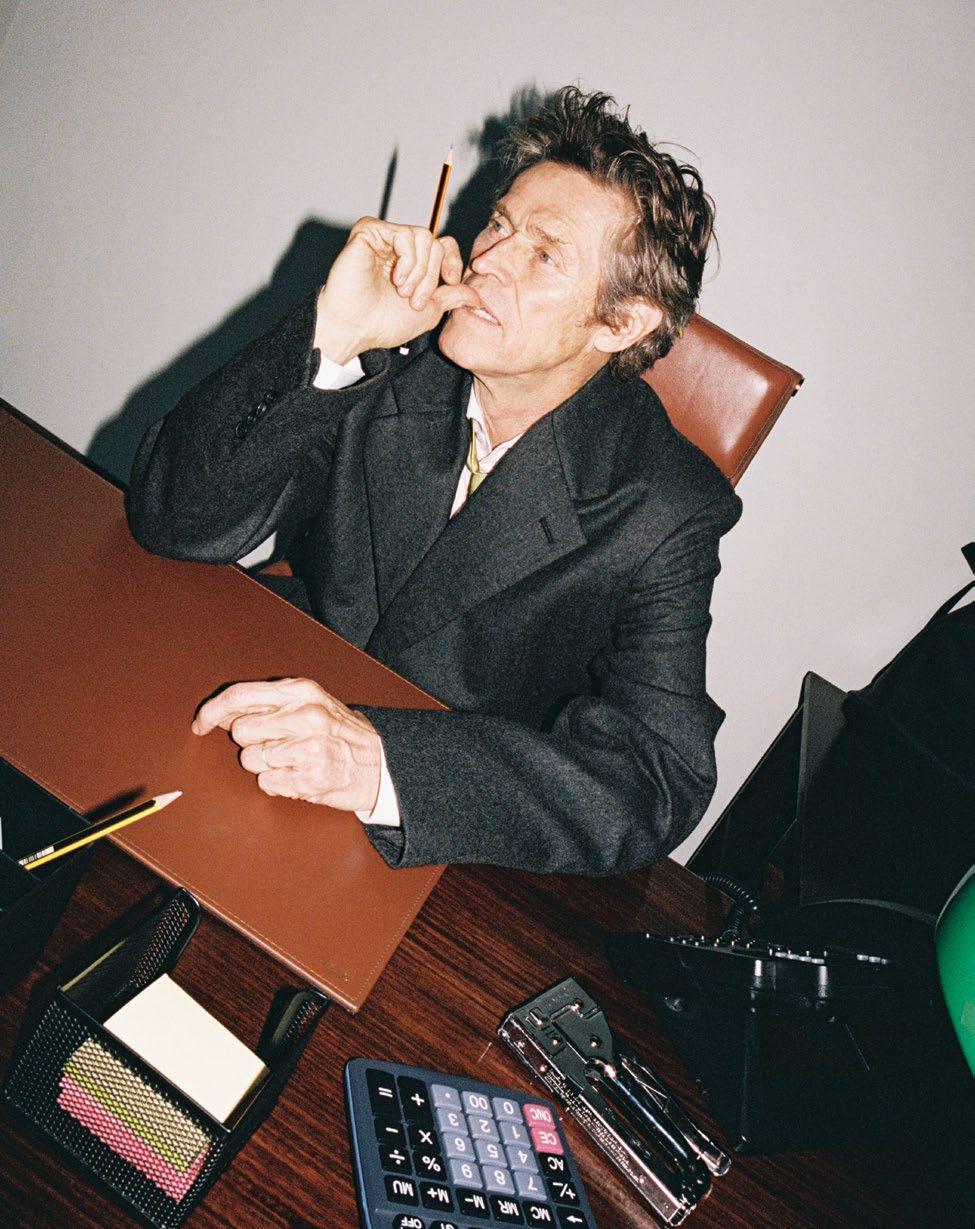

WILLEM DAFOE AND MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ ON DEATH, DIRTY JOKES, AND ENDLESS DEDICATION

Though the pair loom large in their respective art forms, they know one another on a much more intimate scale.

126

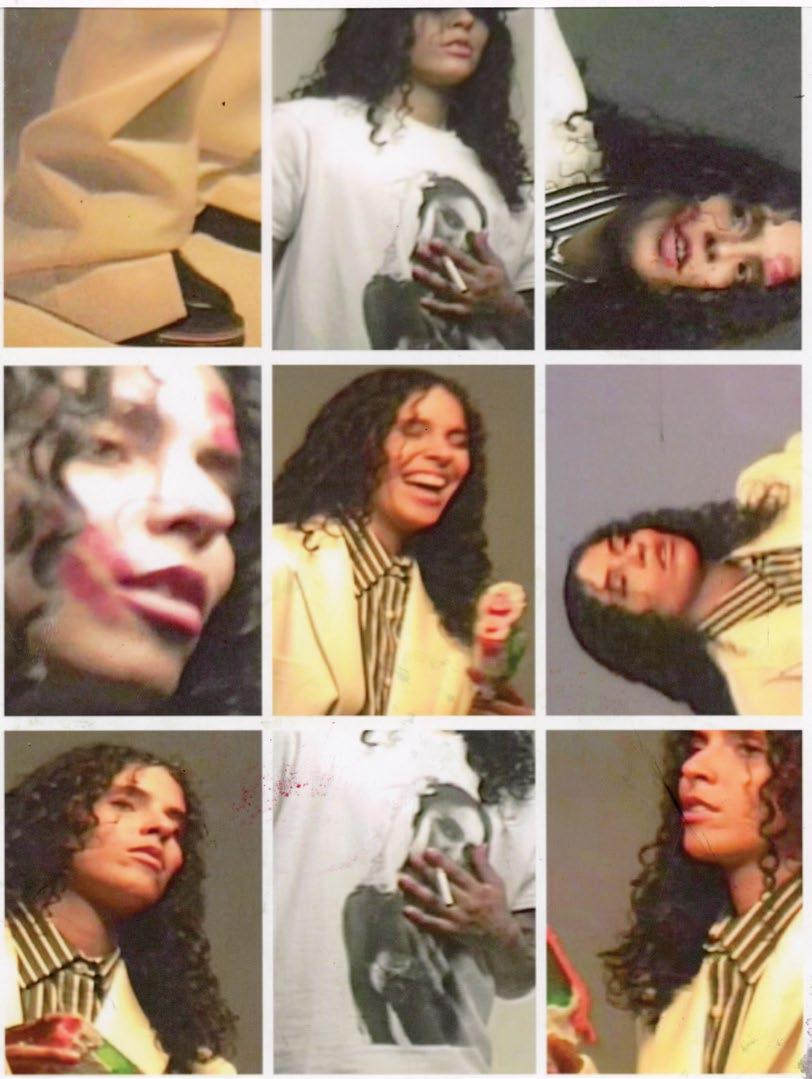

As New Jersey–born 070 Shake prepares to release her third album, she has decided to pull back.

June/July/August 2024

162 134 140 154

In 1972, Stephen Shore drove across America. A never-before-seen trove of his flashsoaked photographs pays homage to the meals he ate along the way.

Photographer John Yuyi conjures a surrealist dreamscape with Tokyo’s dense visual landscape as her canvas and Chanel’s 2023/2024 Métiers d’art collection as her muse.

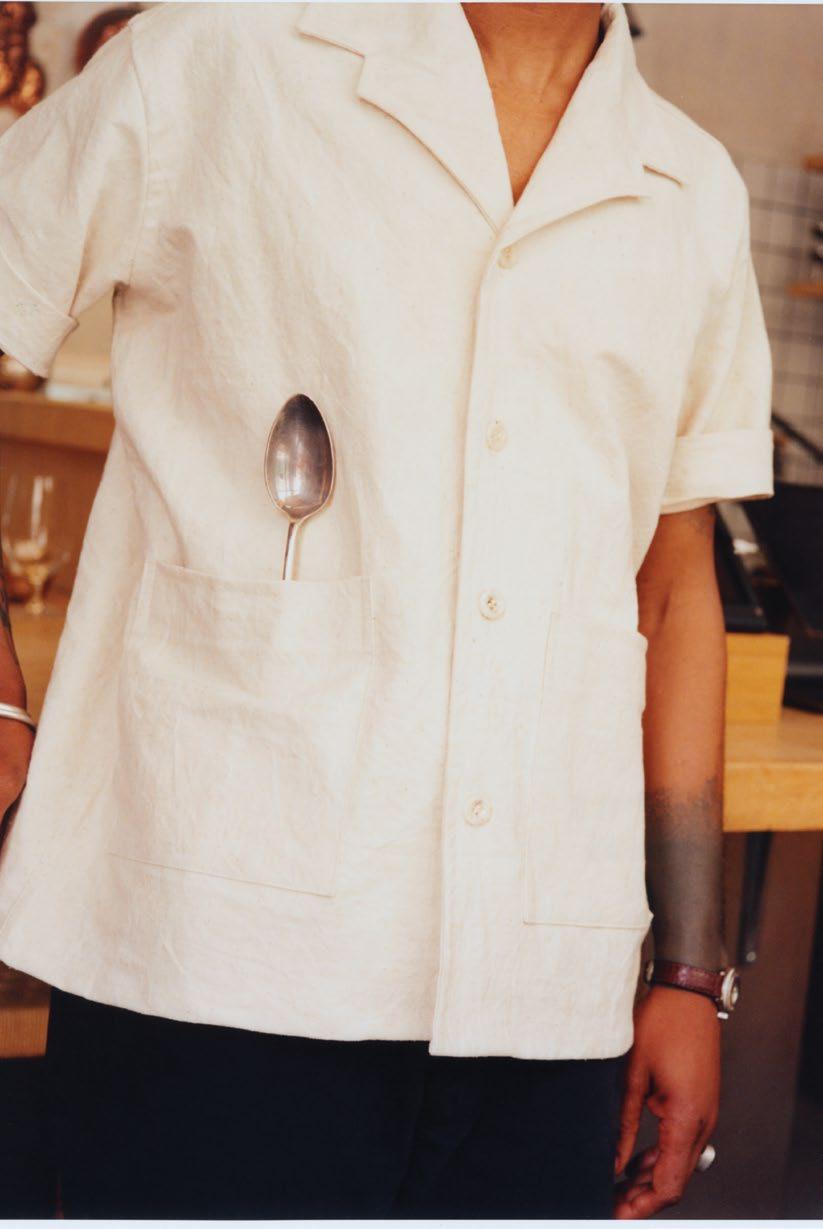

After taking on the outdoor adventurer and the suburban dad, the sartorial set has turned its focus to the culinary uniform. CULTURED asked six chefs to weigh in.

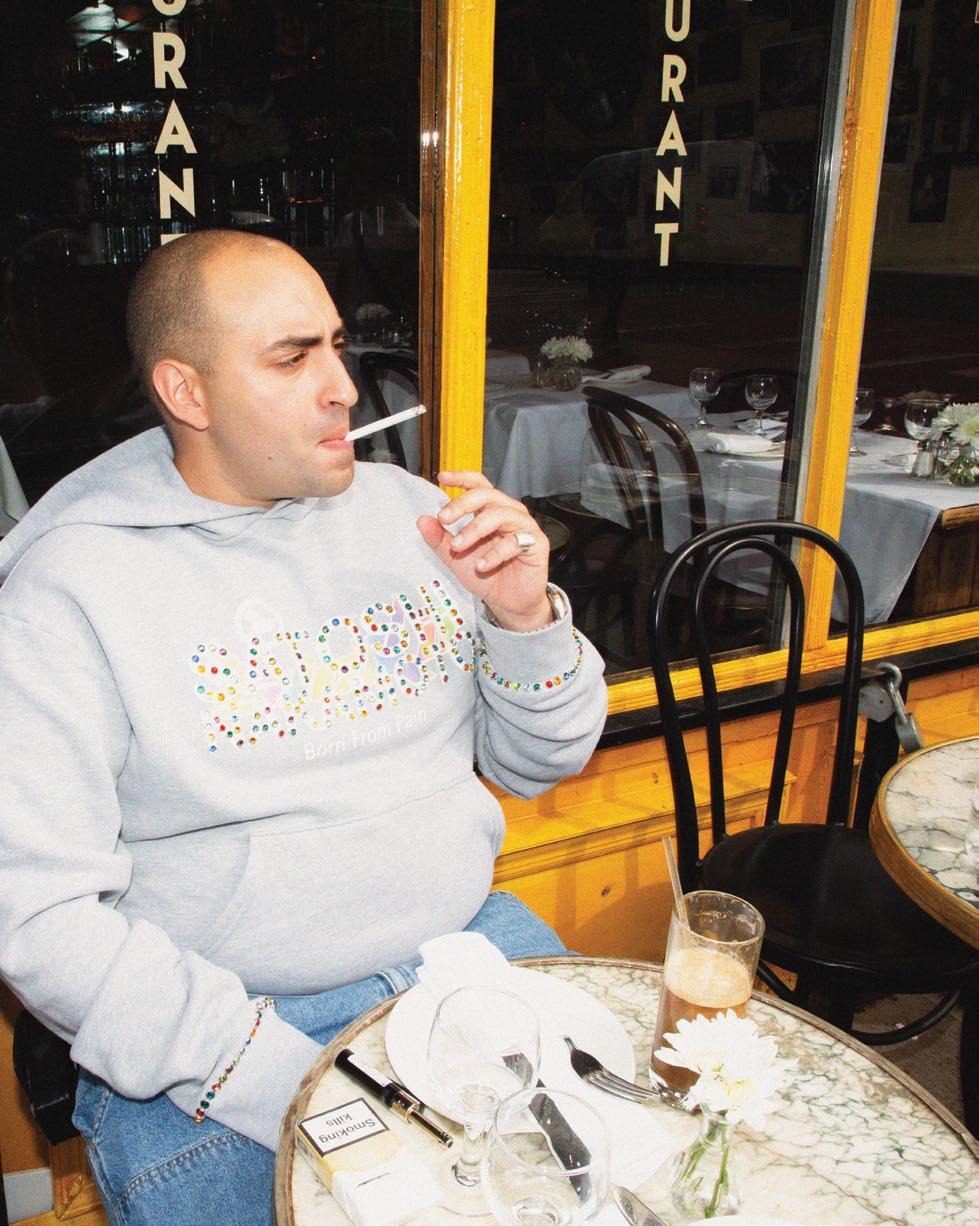

Nate Freeman and Benjamin Godsill sit down with the chef-restaurateurs behind three establishments that have earned the art scene’s enduring trust.

170

EVERYTHING, EVERYWHERE, ALL AT

Photographer Tyler Mitchell returns to his roots this summer with his first Atlanta exhibition, “Idyllic Space,” at the High Museum.

178

TIFFANY & CO. TOUCHES DOWN IN TOKYO

The American luxury brand is out to tell its own story with more ambition than ever before. A new exhibition in Japan proves it.

186

Forty years after debuting Wheatfield, the artist is reviving it in the American West.

192

Writer Ocean Vuong weaves a tale of two Julys with his first public foray into photography, examining the eerie plasticity of time.

204

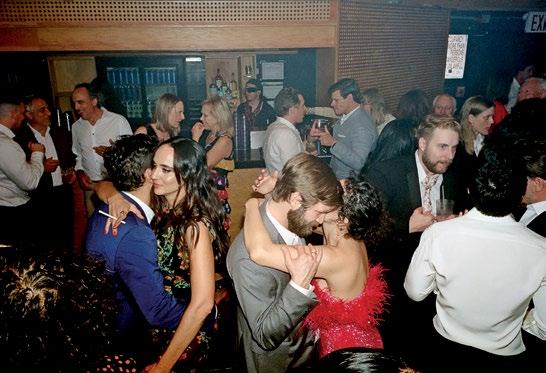

Three years after meeting, Abbi Jacobson and Jodi Balfour dedicated their wedding to the feeling of jubilant, sweaty revelry.

210

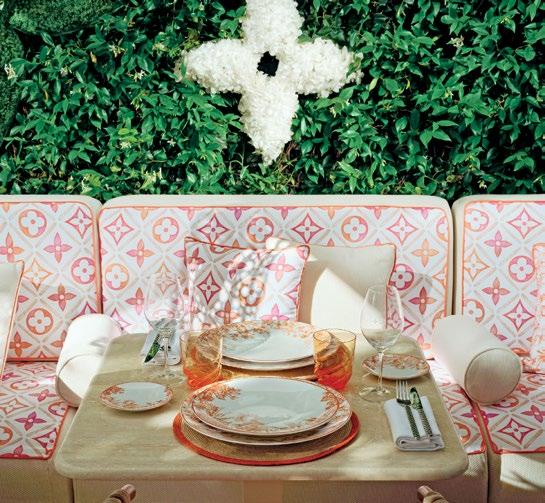

Louis Vuitton’s global culinary outposts prepare for their busy summer season with a new array of tableware in hand.

I’m thrilled to be releasing CULTURED’s first Art and Food issue. Summer is, after all, about indulgence, adventure, and togetherness—the very things we turn to food for.

But above all else, the issue is dedicated to an appetite for more. In the few months since our CULT 100 issue and celebration, we truly have not stopped pushing forward—hosting more events with our partners, publishing more issues, and reaching more readers than ever before.

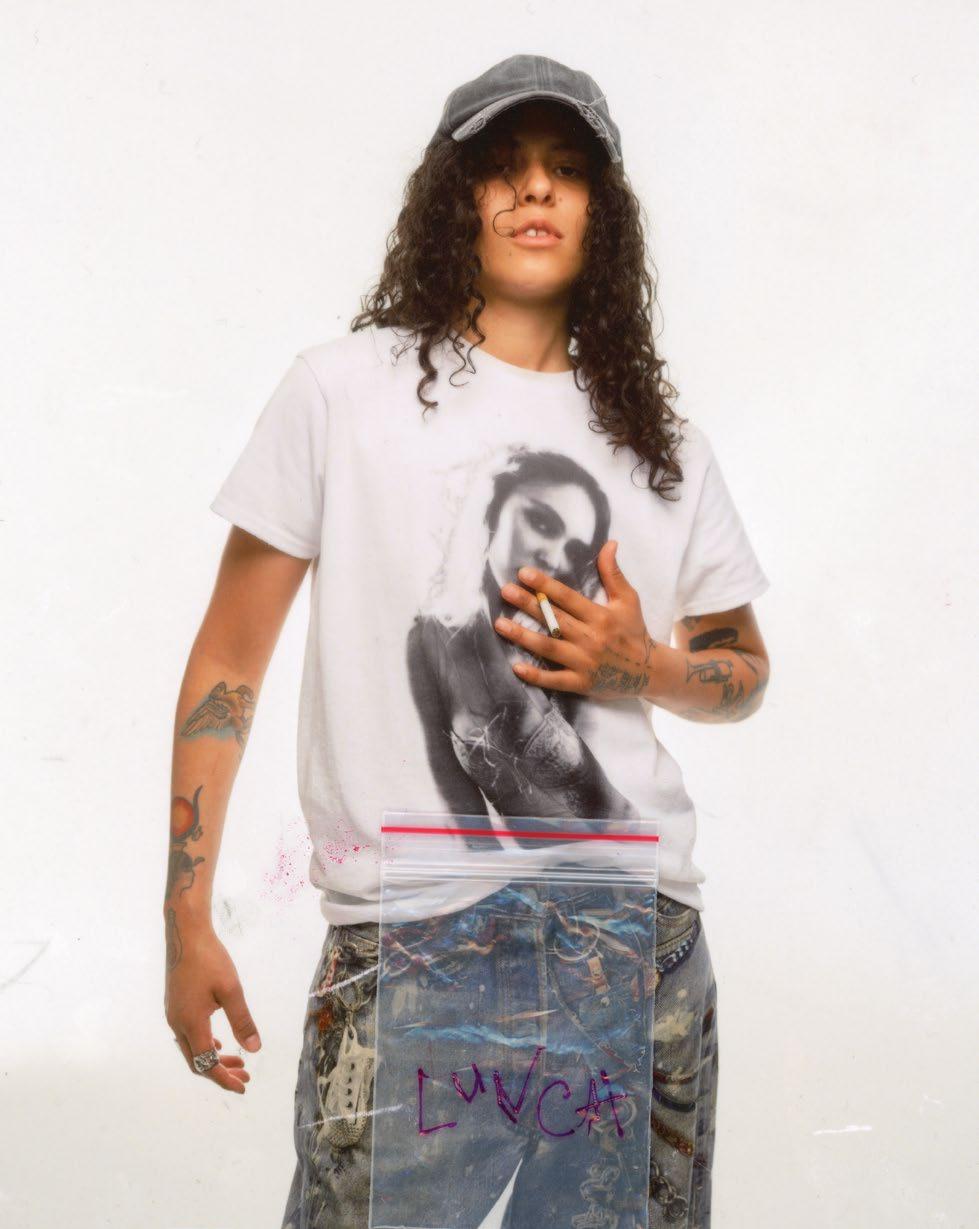

Nobody understands this better than our issue’s cover stars, actor Willem Dafoe and musician 070 Shake. At 68, Dafoe—shot in Rome by Anton Gottlob and in partnership with Prada—has no plans to rest on his laurels. The magnetic performer has nine films in production this year, and Yorgos Lanthimos’s Kinds of Kindness freshly released this month. In his cover feature, Dafoe is asked by his friend Marina Abramović when they’ll both stop working. The actor replies, “Maybe we’re just donkeys, and work is the carrot being dangled in front of us. It’s worked out pretty well for us so far.” Musician 070 Shake—profiled by the incredible J Wortham and shot in Los Angeles by Alana O’Herlihy— is a newer name in the American cultural canon, but no less significant in our current moment. While many of her Gen Z peers make music to suit an algorithm, Shake has isolated herself from the noise to create Petrichor, her forthcoming album. “I hope people will welcome it like a burst of rain in a drought,” she says, “that they’ll be thirsty for and invigorated by it.”

This issue represents the fruits of many other labors, too. Actors and newlyweds Abbi Jacobson and Jodi Balfour share the ways that food and festivities marked milestones in

070 Shake photographedinLos AngeleswearingGucci.Photographyby AlanaO’Herlihy.

Dafoe photographedinRomewearingPrada.PhotographybyAntonGottlob.

their relationship; chef and writer Emma Leigh Macdonald explores the resonance of the chef uniform in contemporary culture; and Stephen Shore unearths a trove of never-before-seen dinner shots from his American Surfaces series. Ocean Vuong, one of the CULT 100 issue’s cover stars, makes his photography debut with a series that weaves two fateful July weeks (one spent with his mother and one following her passing) into one beautiful meditation. Nate Freeman and Benjamin Godsill—hosts of the podcast Nota Bene and notorious gourmand-gossips—join us as section editors, crystallizing years’ worth of martini insights and rounds on the art-fair circuit into a series of interviews with art-world-approved restaurateurs, and a definitive insider’s list of eateries across the world.

Summer is, after all, about indulgence, adventure, and togetherness the very things we turn to food for.

Among the untold hours we spend in edit meetings, planning events with treasured partners, and feeding an ever-expanding hunger for new cultural fare, I do all I can to ensure that everyone on my team takes the time to nourish themselves: diving deep into reading, attending openings for the artists we support, and getting together (whenever geography allows) as a group to share our thoughts and findings over a meal. There’s nothing quite like gathering around a table.

I hope this issue fills you up.

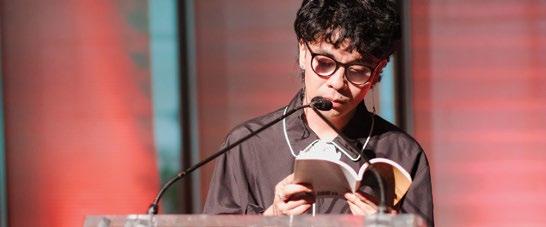

OCEANVUONG Photographer and Writer

“It’s a deep pleasure to debut my photo work with CULTURED.”

MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ Artist

“The only time that I would wake up at 6:30 in the morning for a Zoom conversation is to talk to Willem Dafoe,” admits Marina Abramović. The Yugoslavian artist, now 77, has created an impressive oeuvre of boundary-breaking works of art throughout her decades-long career. Known primarily for her performance pieces, Abramović has in recent years ventured outside the fine arts and into opera—with a little help from Dafoe, who starred in her operatic debut The Seven Deaths of Maria Callas. “He is a real friend, and I would do anything for him,” she says of CULTURED’s cover star. “We always have a good time together.”

“The only time that I would wake up at 6:30 a.m. for a Zoom conversation is to talk to Willem Dafoe.”

“It’s a deep pleasure to debut my photo work with CULTURED,” says Ocean Vuong, poet, novelist, and now, photographer. For the first time, the New York and Northampton, Massachusetts–based literary icon is venturing outside the written word with a stunningly intimate photo essay. Known for best-sellers including On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous and Time Is a Mother, Vuong is finally ready to unfurl his photography before the public. “The CULTURED team has collaborated with me throughout the entire process, working to showcase these images with dignity, respect, and poise— and I’m really proud of what we’ve achieved,” he shares.

Photographer

In 1972, photographer Stephen Shore embarked on a road trip across the United States, compiling the hundreds of snapshots he took along the way into his seminal American Surfaces monograph. Nearly 20 years after the tome was first published by Phaidon, Shore is still sifting through his trove of 35mm film rolls. “On this trip, I kept a visual diary photographing every person I met, every hotel room I stayed in, every town I drove through, and every meal I ate,” he recalls. For CULTURED’s inaugural Art + Food issue, the prolific image-maker shared a series of never-before-seen pictures from his odyssey.

TYLER MITCHELL Photographer

Beyoncé, Harry Styles, Dua Lipa: Tyler Mitchell has peered through his lens at some of the biggest names in the industry. The New York–based photographer has traveled a long way from his roots in Atlanta, but this summer, he’s due for a homecoming. The city’s High Museum is showing “Idyllic Space,” a deep dive into the practice of the first Black artist to shoot the cover of Vogue. “It’s a momentous occasion to be coming back to Atlanta in this way, to the museum I grew up visiting,” he shares. “I want this exhibition to celebrate the city’s DNA and history in a poetic way.”

“It’s a momentous occasion to be coming back to Atlanta in this way, to the museum I grew up visiting.”DURGA CHEW-BOSE Writer

“Any chance I get to rewatch Olivier Assayas’s Summer Hours, I take it,” says Durga Chew-Bose. The Brooklyn-based writer and filmmaker penned a passionate ode to the 2008 film for this issue. Elsewhere, she’s contributed writing to GQ, The Guardian, and Rolling Stone, among other publications, and released an essay collection, 2017’s Too Much and Not the Mood. Her forthcoming directorial debut, an adaptation of Françoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse, stars Chloë Sevigny. “[Summer Hours] is an education in storytelling, in how to quietly accumulate narrative with a potency that lingers long after the credits roll,” she adds. “I love its use of objects as counsel. I love its use of summer as the most bittersweet season.”

DOMINIQUE SISLEY Writer

DOMINIQUE SISLEY Writer

“Steve O Smith is one of the most innovative young designers working today,” asserts Dominique Sisley. “He captures the provocative, boundarybreaking spirit of London fashion at its best.” For this issue, the writer caught Smith ahead of his debut at this year’s Met Gala, working overtime in his studio to prepare his disruptive garments. “The man himself was so warm, and his brain seems to move at 1,000 miles an hour,” says Sisley, who is senior editor at AnOther and Dazed, and freelances for the likes of The Guardian, Elle, and The Face.

“Summer Hours is an education in storytelling, in how to quietly accumulate narrative with a potency that lingers long after the credits roll.”

There is no greater proof of one’s status as a longtime New Yorker than being singled out from the hordes by a favorite bartender, tailor, or waiter. Gaining “regular status,” as Annie Armstrong puts it, is no simple feat—“There is no one path to this coveted prize,” she asserts. In this issue of CULTURED, the writer and reporter speaks

Art Advisor and Writer respectively, Co-Hosts of Nota Bene podcast

“Half a lifetime of hard-earned caloric research went into getting it down on paper—not to mention all the air miles and jet lag,” says New York–based art advisor Benjamin Godsill of his work on this issue’s chef interviews and art-world restaurant guide. Along with his Nota Bene podcast co-host, writer Nate Freeman, Godsill spoke with the restaurateurs behind some of the art world’s most significant gatherings and compiled the ultimate list of eateries the industry swears by. “The reality is, good artists go to good places to eat,” says Freeman. “You can’t talk about the art world without talking about where everybody gets lunch.”

“Half a lifetime of hard-earned caloric research went into getting it down on paper—not to mention all the air miles and jet lag.” —Benjamin Godsill

with several New Yorkers about how they attained regular status at their favorite restaurants. Elsewhere, Armstrong specializes in reporting on the contemporary art ecosystem, and helms Artnet News’s cult gossip column, “Wet Paint,” a breakdown of art-world happenings both comical and jaw-dropping.

JOHN YUYI Photographer

“It was definitely an adrenaline-filled day in Tokyo,” says John Yuyi. For this issue, the Taiwanese photographer met with Japanese actor and model Serena Motola for a saturated, rain-soaked shoot in Chanel’s latest Métiers d’Art collection. “On a day that had been super sunny all week, it rained and the weather became much colder, but the reflections on the wet glass and the pedestrians holding umbrellas were unexpectedly cinematic,” she recalls. The photographer has previously lent her lens to the likes of Gucci; Heaven by Marc Jacobs; and In Memory Of…, a 2023 monograph.

MARA VEITCH Executive Editor

ALI PEW Fashion Editor-at-Large

COLIN KING Design Editor-at-Large

REBECCA AARON Senior Creative Producer

ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT Senior Editor

SOPHIE LEE Editorial Assistant

JACOBA URIST New York Arts Editor

CAT DAWSON, DEVAN DIAZ, ADAM ELI, ARTHUR LUBOW, HARMONY HOLIDAY, GEOFFREY MAK, SARA ROFFINO, NICOLAIA RIPS, LAURA MAY TODD, EMMA LEIGH MACDONALD, LIANA SATENSTEIN, JOHN VINCLER Writers-at-Large

PALOMA BAYGUAL, BRYAN BEDOLLA, COLLIN COLAIZZI, DANIELLE MILLER Interns

SARAH G. HARRELSON Founder, Editor-in-Chief

JULIA HALPERIN Editor-at-Large

TOM MACKLIN Casting Director

SIMON RENGGLI, CHAD POWELL Art Directors

HANNAH TACHER Junior Art Director

JAYNE O’DWYER Assistant Editor

BERT MOO-YOUNG Senior Photo Retoucher

EVELINE CHAO Copy Editor

DOMINIQUE CLAYTON, KAT HERRIMAN, JOHN ORTVED, YASHUA SIMMONS, KAREN WONG Contributing Editors

ALEXANDRA CRONAN, KATE FOLEY Contributing Fashion Directors

GEORGINA COHEN European Contributor

CULTURED Magazine 2341 Michigan Ave. Santa Monica, California 90404 ISSN 2638-7611

CARL KIESEL Chief Revenue Officer

LORI WARRINER Publisher

DESMOND SMALLEY Director of Brand Partnerships

SOPHIA FRANCHI Marketing Coordinator

CARLO FIORUCCI Italian Representative, Design

ETHAN ELKINS, DADA GOLDBERG Public Relations

PETE JACATY Prepress/Print Production

JOSÉ A. ALVARADO JR., SEAN DAVIDSON, SOPHIE ELGORT, ADAM FRIEDLANDER, JULIE GOLDSTONE, WILLIAM JESS LAIRD, GILLIAN LAUB, YOSHIHIRO MAKINO, LEE MARY MANNING, BJÖRN WALLANDER, BRAD TORCHIA Contributing Photographers

SIENNA FEKETE Podcast Editor

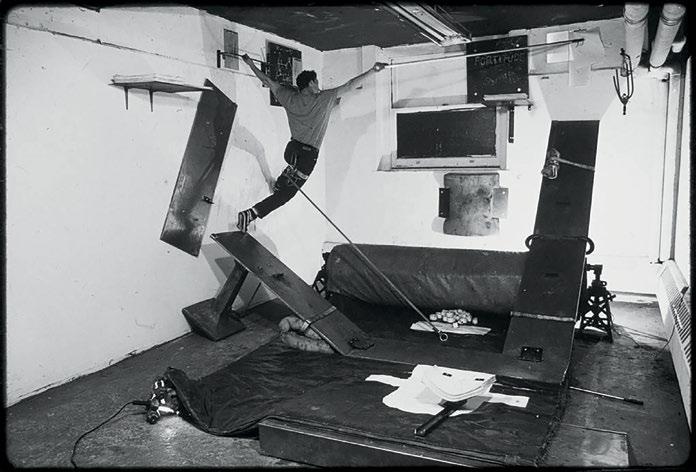

THE VISIONARY ARTIST LOOKED BACK TO HIS FOOTBALL PAST, AND A MOMENT THAT CHANGED THE SPORT FOREVER, FOR HIS 2023 FILM SECONDARY. WITH A SUITE OF NEW EXHIBITIONS, THE MASTER OF EXTREMITY IS TAKING THE NEW WORK IT GENERATED ON A WORLD TOUR.

By ELLA MARTIN-GACHOTAmerican football has only made one appearance at the Olympics, during the Summer Games that took over Los Angeles in 1932. The reasons for its disqualification are myriad; among them are an incompatibility of timing (a week-long break is required between professional matches), the sport’s propensity for injury, and the fact that the United States would undoubtedly win out. But the game will leave its mark in another way during this summer’s Olympic Games in Paris. A 20-minute Métro ride away from Arena Paris Sud—the venue that will host volleyball, table tennis, weightlifting, and handball competitions—Matthew Barney will populate the Fondation Cartier with his meditation on the sport and its discontents: “Secondary.”

At the heart of the exhibition and its titular five-channel film is an incident that shook the American pastime to its core. On August 12, 1978, during a preseason game between the Oakland Raiders and New England Patriots, defensive back Jack Tatum’s shoulder pad slammed into wide receiver Darryl Stingley’s helmet, leaving him paralyzed for life. Now an art-world avatar best known for his extreme performances and canonical video works, Barney was then an 11-year-old youth league quarterback, and, although he didn’t see the impact happen live, it haunted him. “I

watched the replay over and over in every halftime show and broadcast that happened throughout that year,” he recalls. “That’s how I absorbed it—a kind of relentless replay.”

Secondary, which made its U.S. debut in Barney’s former Long Island City studio last spring, doesn’t so much reenact the moment of impact as reimagine it through a series of exacting and abstracted somatics. Over an hour, the camera follows as Barney and 10 other performers—in the roles of Stingley, Tatum, Raiders owner Al Davis, a referee, an anthem singer, and a handful of additional players—move through training, game-day drills, and the elaboration of sculptural props (weights, protective headgear) with painstaking precision.

The film is a vessel for a suite of concerns— including America’s fictions, physical decay, ritualistic violence, the production and preservation of memory—but it is never a condemnation. “I’m not really interested in the work functioning as a kind of judgment,” Barney explains. And he doesn’t see the story’s cultural DNA as a roadblock for European audiences either. “I’m always looking for a way to take the specificity of my narrative and to make it more universal, to broaden the entry points into the work.”

That outward thrust is pursued in the Fondation Cartier exhibition and a quartet of satellite gallery shows (at Gladstone, Sadie Coles HQ, Regen Projects, and Galerie Max Hetzler) with a new series of ceramic sculptures that crystallize a sense of resistance and brittleness. Barney sees the pieces as an inquiry into the ways materials exhibit stress, like a form of sculptural reflexology. Rounding out the Cartier exhibition are a selection of the artist’s early “Drawing Restraint” videos, in which he constricts his movements with a slew of apparati while making drawings. For the occasion, he will stage a new iteration with Raphael Xavier, the breakdancer who played Tatum in Secondary, attached to a resistance training bungee cord.

Although their execution and results diverge, the connection between the ongoing series and 2023 film is clear: Barney is taken with the formal aftermath of transgressing a physical limit and understanding both the risk and catharsis that lie beyond it. He knows that where there is pain, there is an audience ready to behold its visual collateral. We are all too ready to watch the extreme on replay without paying the price of experiencing it.

“I

WATCHED THE REPLAY OVER AND OVER IN EVERY HALFTIME SHOW AND BROADCAST THAT HAPPENED THROUGHOUT THAT YEAR. THAT’S HOW I ABSORBED IT—A KIND OF RELENTLESS REPLAY.”

OVER THE LAST SIX DECADES, MARTHA JUNGWIRTH’S ARTISTIC PRACTICE HAS TEETERED BETWEEN IMPULSE AND INTENTION. THIS SUMMER, TWO EUROPEAN SHOWS CEMENT HER STATUS AS A SINGULARLY DEFT ARTICULATOR OF THE PAINTERLY PROCESS.

At 84, Austrian artist Martha Jungwirth has faced down blank canvases—or one of the many nontraditional surfaces she makes her incisive, unpasteurized marks on—for over six decades. Two expansive European shows, on view through September at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and Venice’s Fondazione Giorgio Cini, prove that the painter has more marks to leave—and a constellation of concerns, both formal and contextual, to fuel them.

AT THE END OF YOUR 1988 POEM “THE APE IN ME,” YOU WROTE, “EGO-SHIFT: IS WHAT I CALL THE MOMENT AT THE END OF / PRIMITIVE THINKING AT THE AGE OF SEVEN WHEN TEACHERS / START DRILLING RULES AND DRIVE OUT THE FAIRY-TALE AGE.” DO YOU FEEL THAT YOUR ARTISTIC CAREER HAS AFFORDED YOU A WAY TO ESCAPE THOSE RULES AND STAY IN THE “FAIRY-TALE AGE”? You don’t quite manage to stay in that

fairy-tale age, but as an artist you naturally have other roots that link you to your childhood—creativity and imagination. Other people may have to discard or neglect these roots because their lives are focused on the practical. As an artist, you can escape societal rules by setting your own.

YOUR GUGGENHEIM BILBAO RETROSPECTIVE INCLUDES WORK UP UNTIL 2023. WHAT HAS YOUR STUDIO PRACTICE LOOKED LIKE IN RECENT YEARS, AND WHAT WERE YOU SURROUNDING YOURSELF WITH IN THE MAKING OF THOSE NEWER WORKS? I surrounded myself with good art and traveled to see exhibitions. I’m constantly looking at “old” art. In recent years, great painters like Goya or Manet have become much more interesting in terms of our era. Goya is one of the most important artists of all, especially in our current state of affairs, because he painted entire series on war and the catastrophes

associated with it. And I find Manet interesting as a painter. His 1880 painting L’Asperge is one that you will never forget for the rest of your life. Manet also painted the shooting of Maximilian in Mexico, drawing on the shootings in Goya’s paintings. Especially in a rather bleak time, from pandemic to war, I have been thrown back to artists who leave a lasting impression.

SPONTANEITY IS AT THE CENTER OF YOUR WORK. I’M THINKING OF ANOTHER LINE IN “THE APE IN ME”: “LEAVE VISIBLE THE PAINTING / PROCESS, NO RETOUCHING, RISK NOT RECIPE. NON FINITO.” HOW DO YOU CREATE THE CIRCUMSTANCES TO REMAIN SPONTANEOUS AS AN ARTIST, AND TO CONTINUE TO SURPRISE YOURSELF? By painting and seeing what kind of “blotch” I can create. I constantly surprise myself when I’m working, but of course you have certain ideas about quality. In the course of painting you have to return to those ideas.

“As an artist, you can escape societal rules by setting your own.”

TRAVEL, NATURE, AND LITERATURE HAVE BEEN LIFELONG INSPIRATIONS FOR YOU. WHAT RECENT ADVENTURES HAVE MARKED YOU? Above all, I saw a lot of exhibitions. The German title of the exhibition “Herz der Finsternis,” at Palazzo Cini in Venice, references Joseph Conrad’s famous novel Heart of Darkness, which I read as a young woman. It tells the fictionalized story of a Belgian steamboat expedition up the Congo River, exploring the brutality of European colonialism in Africa at the time. An important impetus for my new works in Venice came from reading the book Africa, in Chains [Afrika, in Ketten, a compilation of work published in German] about colonial history by the French writer and journalist Albert Londres. His descriptions gave me the idea to visit the Musée de l’Histoire de l’Immigration at the Palais de la Porte Dorée, a building that was constructed for the last Paris Colonial Exhibition in 1931. It was against this thematic background of colonialism, exploitation, and migration then and now that the series of pictures entitled “Porte Dorée,” now on view in Venice, was created.

WHAT ARE YOU EXCITED TO DO NEXT?

To keep painting!

WITH A RAPIDLY GROWING SPHERE OF CREATIVE OUTLETS, AND HER MOST COLOSSAL SHOW YET ON VIEW AT JACK SHAINMAN GALLERY’S THE SCHOOL THIS SUMMER, THE ARTIST IS CEMENTING HER PLACE IN THE CONTEMPORARY CANON.

By ELLA MARTIN-GACHOTWhat does it mean to be a monument in the making? At 43, Nina Chanel Abney is the rare artist who has earned the elite seal of institutional approval—with prized commissions from the likes of the Lincoln Center, work held in the collections of art world megaliths like MoMA and the Whitney, and an excess of solo shows under her belt—while remaining strikingly approachable, even popular.

In 2024, the NCA Extended Universe includes collaborations with Jordan, Timberland, and EA Sports; New Yorker magazine covers; and even a thousand-piece puzzle—a constellation of design initiatives that will soon be formalized under the name of Super Cool Studios.

“Humor has always been more than a mere stylistic choice—it is my weapon and my shield.”

Abney is inviting you along for the ride, but on her own terms. The Illinois native has navigated the expectation for contemporary artists, especially artists of color, to be funambulists of sorts with a crucial instrument in tow. “Humor has always been more than a mere stylistic choice—it is my weapon and my shield,” she says. “It

disarms, ensuring that the first interaction with my work is one of accessibility rather than confrontation. Yet, beneath this initial engagement lies a labyrinth of complexity.”

Implied in that maze is the farrago of themes Abney has probed throughout her two-decade-long career—from the weight of racial stereotypes to the velvet hammer of latent homophobia.

In her work, which is rooted in painting but has pushed past the canvas in recent years, Abney lays these subjects out with a trickster’s touch: “I aim to lure viewers into a space of false comfort, then confront them with a reality that is anything but comfortable.”

The New York–based artist’s tradition of sitting with the trouble, instead of just depicting it, continues this summer with a colossal show at Jack Shainman Gallery’s Kinderhook outpost, The School. “LIE DOGGO” pairs a brand-new series of paintings with Abney’s first foray into sculpture, an interactive digital art installation (the fruit of an inaugural residency with CryptoPunks, an NFT collection), and expansive murals taking advantage of the site’s architecture.

With it, she continues to forge her place in art history and offer visitors the visual vocabulary to start to understand it—if they stay and think awhile.

Photography by Marisa Langley

GROWING UP, ALEX W. CROWDER SPENT HER FREE TIME IN THE FOREST. NOW, SHE’S THE FOUNDER OF DESIGN-WORLD DARLING FIELD STUDIES FLORA—A BOTANICAL “LABORATORY” THAT DRAWS ON CHILDHOOD MOMENTS OF WONDER TO CREATE OTHERWORLDLY ARRANGEMENTS.

By ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT Photography by ANASTASIIA DUVALLIÉAs a child growing up in the Ozarks, Alex W. Crowder’s imagination came alive in the woods and fields near her home, where she’d forage for plants, assembling offerings to fairies and wildlife.

A few decades later, the same adoration for the natural world is at play with Field Studies Flora, her New York–based botanical “laboratory.” “We’re trying to invite people into new ways of seeing,” the florist explains.

Sourcing her materials from within 150 miles of her Brooklyn studio, and with the support of a crew of foragers and farmers, Crowder assembles her meticulous living sculptures— mementos of nature’s ever-changing tides (and tastes). “I often say I want to be the Alice Waters of floristry,” she says with a laugh. Oyster mushrooms, kale, and geraniums are all the foundations of her edible works, assemblages that reimagine what we think of as florals. (One of her favorite ways to surprise a client? Incorporate an edible.)

With curiosity as its compass, Field Studies Flora approaches its craft as an opportunity to bask in nature’s abundance. “I want people to broaden their horizons,” Crowder concludes. “Be intentional about what goes into your meal and your floral arrangements. Sometimes the two things can be the same.”

“I often say I want to be the Alice Waters of floristry.”

—ALEX W. CROWDER

Cultivating Dreams

OSGEMEOS: Endless Story

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Washington DC

Opening September 29, 2024

New York

June 22–August 16 2024

MAST CAPITAL CEO CAMILO MIGUEL JR. HAS BORNE WITNESS TO A TRANSFORMATION IN THE LANDSCAPE OF HIS COASTAL HOMETOWN. WITH THE CONSTRUCTION OF A GLEAMING NEW TOWER IN BRICKELL, THE MIAMI NATIVE LEAVES A LASTING MARK.

“Growing up in this vibrant city and witnessing its evolution into the dynamic coastal metropolis it is today has been an extraordinary privilege,” says Camilo Miguel Jr., CEO of Mast Capital, about his hometown of Miami. Since he founded the development company in 2006, both the firm and the Floridian city have undergone a stunning evolution. The funding behind Mast Capital’s expansive portfolio has surged into the billions, and recent years have seen venture capital funding in Miami do the same.

Most recently, Mast Capital secured a $600 million loan to build Cipriani Residences Miami, a glass-paned, 80-story tower in the Brickell neighborhood.

The project is hotelier and restaurateur Cipriani’s first ground-up residence within the U.S., and the confluence of Miami style and Italian influence has resulted in a breezy construction, outfitted with sleek lounges, penthouses, and speakeasies that encourage indoor-outdoor living. Here, Miguel Jr. offers his insight into the changing landscape of the cultural mecca, straight from a man who has seen—and built—it all firsthand.

What is one thing you wish non-locals knew about Miami?

CAMILO MIGUEL JR.: Miami offers an unparalleled array of experiences, from its breathtaking beaches and rich cultural institutions to its distinctive fashion districts, art-adorned streets, and thriving culinary scene that stands unrivaled.

“Once a corridor of office buildings serving commuters, Brickell has evolved into a vibrant, multifaceted waterfront community with a walkable live-work-play lifestyle.”

—CAMILO MIGUEL JR.

The city provides virtually any experience one could desire, all within convenient proximity.

How have you seen Brickell change over time, and how do you expect this project to impact the local area?

MIGUEL: Brickell has undergone an incredible and elevating transformation over the past decade. Once a corridor of office buildings serving commuters, it has evolved into a vibrant, multifaceted waterfront community with a walkable live-work-play lifestyle.

Developments like Brickell City Centre have introduced high-end shopping and dining, while enhanced transportation options like the Brightline have increased accessibility. Cipriani Residences Miami builds on this evolution with its sleek, all-glass design and luxurious lifestyle.

How will your $600 million loan, the largest single-tower construction loan obtained in Florida thus far, be reflected in the scale and scope of this project?

MIGUEL: Securing a $600 million loan for Cipriani Residences Miami is reflective of the strength of our organization and signifies a major milestone highlighting its tremendous success to date, due to the immense demand for ultra-luxury condominiums in the Brickell area with certainty of delivery.

We have assembled top-tier architectural and design talents to bring this vision to life … embodied in the project’s bespoke residential offerings, five-star culinary experiences by Cipriani, expansive floor plans with curated interiors by 1508 London, and a distinctive curved façade by Arquitectonica.

What do you think makes Miami a particularly fruitful location for development? Have you seen conceptions of the area change over the course of your career?

MIGUEL: Miami has ascended as one of the world’s most desirable places to live, attracting global celebrities and notable companies alike, solidifying its reputation as a credible business and financial hub. The city’s economic evolution, driven by a diversified business landscape, positions it for sustained success.

Today, Miami represents the epitome of a booming metropolitan area, rich in cultural diversity and vibrancy. Our real estate market is the hottest in the country, and buyers now recognize Miami as

“Today, Miami represents the epitome of a booming metropolitan area, rich in cultural diversity and vibrancy.”

—CAMILO MIGUEL JR.

much more than a haven for warm weather and favorable taxes, but also as a socially and culturally thriving city.

How do you work with Cipriani and the architectural team to see a project of this scale through from start to finish?

MIGUEL: Cipriani’s brand identity has been meticulously integrated from the project’s

inception, capturing the essence of the original Harry’s Bar in Venice while ensuring a timeless design. Four iconic firms have brought Cipriani Residences Miami to life, each contributing international perspectives and expertise that uniquely qualify them to realize this extraordinary vision.

How does this project speak in particular to the types of residents you are seeing move into the Miami area?

MIGUEL: Cipriani Residences Miami is designed for the thousands of C-suite executives and high-level employees relocating to Brickell as companies like Citadel, Blackstone, Apple, Google, and Microsoft expand their presence. We cater to these discerning buyers by offering intimate, exclusive experiences with private dining, lounging, and meeting spaces in a highly curated, club-like environment. Our speakeasy and the top-tier luxury of the Canaletto Collection on the upper floors, featuring priority amenities and custom furniture packages by 1508 London and Cipriani, epitomize the elevated lifestyle the residences offer.

THE PATRON SAINT OF GOOD LIVING OFFERS CULTURED’S DESIGN

EDITOR-AT-LARGE, COLIN KING, A PEEK INSIDE HER SEASONAL RITUALS.

“I ADMIT THAT I READ THE COMMENTS WHEN I HAVE AN EXTRA MOMENT OR TWO. IF IT’S SOMETHING REALLY OUTRAGEOUS, I’LL ANSWER. SOMETIMES I HAVE TO RESTRAIN MYSELF BECAUSE I DON’T WANT TO GET INTO TROUBLE.” —MARTHA STEWART

Martha Stewart really needs no introduction. When we speak, the 82-year-old media mogul and doyenne of all things domestic is sitting outside her Bedford estate in a parked Polaris. It’s not even lunchtime, and she’s already tended to her farm, taken several appointments, moved some furniture, done Pilates, and delivered bagels to either her team or her animals (it’s unclear whom she means by her “gang”). As she prepares to release her hundredth book this year, Stewart found a rare moment in her exceedingly packed schedule to chat about the current “Martha-sance,” why she doesn’t DM, and the secret behind her famous dinner parties—all while attempting to take a photograph of a chipmunk in her garden.

COLIN KING: There’s been an undeniable “Martha-sance” recently. How do you feel about your place in the zeitgeist?

MARTHA STEWART: That’s a nice word! I’ll have to add that to my vocabulary. It’s fun because I hope to lead the way in terms of our thoughts about geriatric people—one can continue to be productive, useful, and creative if one keeps going and has personal drive. People appreciate that. A lot of people my age and even younger admire the fact that I am very energetic. So that’s what it’s all about.

KING: I’m one of those admirers! You’re the queen of personal branding. How would you advise someone looking to start or evolve their own brand?

STEWART: Everybody’s trying to make a brand these days. Even children are making brands. It’s quite extraordinary. When I started in 1982 with my first book, it was much more difficult to make a bestseller that would become an essential part of the American kitchen. A few people had done it, but not to the degree that they’re doing it nowadays. Last year, I think there were 20,000 cookbooks published. I don’t know how many cookbooks were published in 1982, but I would venture to guess it was less than 500.

KING: Your personal Instagram is incredible —it gives us a glimpse into your life and your interests, and there’s such a sense of enjoyment there.

STEWART: I’ve been a proponent of social media ever since it started. I adopted Twitter

immediately, loved it, and invested in it. The same with Instagram; I was an investor in the pre-Meta company, and I tried very hard to understand everything they were doing. I visited their offices and spoke at some of their conferences. I don’t always agree with what’s happening online, because it’s taking up an awful lot of our time. I sat on a plane the other day, and I don’t think there was one person out of 400 who wasn’t glued to their phone before we took off.

KING: Who is the last person you DM’d?

STEWART: I do not DM. You know why? Because I still love the telephone. If I want to talk to somebody, I call them and I leave a message. Probably 95 percent return them. With DMs, that percentage is much lower. I have so many DMs on my Instagram, and I’ve never looked at them. I refuse. I admit that I read the comments when I have an extra moment or two. If it’s something really outrageous, I’ll answer. Sometimes I have to restrain myself because I don’t want to get into trouble.

KING: How do you feel about the design world today?

STEWART: Wait, I have to take a picture of this chipmunk. I’m sitting outside, and one of my evil chipmunks is sitting on the edge of a beautiful flower pot. I’m going to get its picture right now.

[Martha accidentally hangs up while trying to photograph the chipmunk.]

KING: Did you get the picture?

STEWART: I’m sending it to you right now.

KING: [Laughs] Great! You recently returned to the cover of Sports Illustrated for its 60th anniversary issue. How has it felt to tap into a new facet of your image, and what are your thoughts on the “summer body”?

STEWART: Well, everybody wants to look good while they’re sitting at the pool, windsurfing, or paddleboarding. So it’s time to shape up a little bit, starting, like, right now. That’s not the only reason I go to Pilates three times a week and kill myself, but it’s certainly healthy and appealing to many people. Everybody should take care of themselves physically. It will add to longevity,

good health, and non-absenteeism at work.

KING: So, if you spontaneously have a free summer day, how are you spending your time?

STEWART: I garden! I have a huge garden in Bedford and a huge garden in Maine. My days begin and end with gardening, and with animal care. I do have help, but I still oversee the operations of the farm. Today is Friday, and I had a lot of appointments this morning—a visit with the septic tank man, a viewing of a new electric lawn mower. Then I moved a tremendous amount of furniture into a house on the property that I’m trying to make into a guest house. And what else did I do today? I went to Pilates. What time is it?

KING: It’s only 12:45 p.m.

STEWART: I’ve done a lot today.

KING: Can you walk us through organizing one of your famous dinner parties? Who are your first three calls to?

STEWART: I’m actually organizing an important dinner for a historic vintage of the champagne Krug. It’s going to be about 24 people, and I’m doing it in a dining pavilion near my pool that’s really picturesque for a dinner party. The first call is to my chef-slash-caterer, Pierre Schaedelin, to ask if he’s available. The second call is to someone I trust, to ask them to assist me that day. The third is to Susan Magrino, my publicist, with whom I discuss most things. If she likes the idea of the whole thing, then we proceed. Oh, and the flower man!

KING: Complete this sentence: “It’s not a Martha Stewart summer without…”

STEWART: It’s not a Martha Stewart summer without my grandchildren, my daughter, and a house full of friends in Maine.

KING: What’s one thing you’d still like to achieve?

STEWART: Immortality!

KING: What is your biggest contribution to culture?

STEWART: I have taught people to look at their homes not only as shelter, but as a place to enjoy. What we have created in terms of information and inspiration has been valuable to a very wide audience. For that, I’m really grateful.

“I HOPE TO LEAD THE WAY IN TERMS OF OUR THOUGHTS ABOUT GERIATRIC PEOPLE— ONE CAN CONTINUE TO BE PRODUCTIVE, USEFUL, AND CREATIVE IF ONE KEEPS GOING.” —MARTHA STEWART

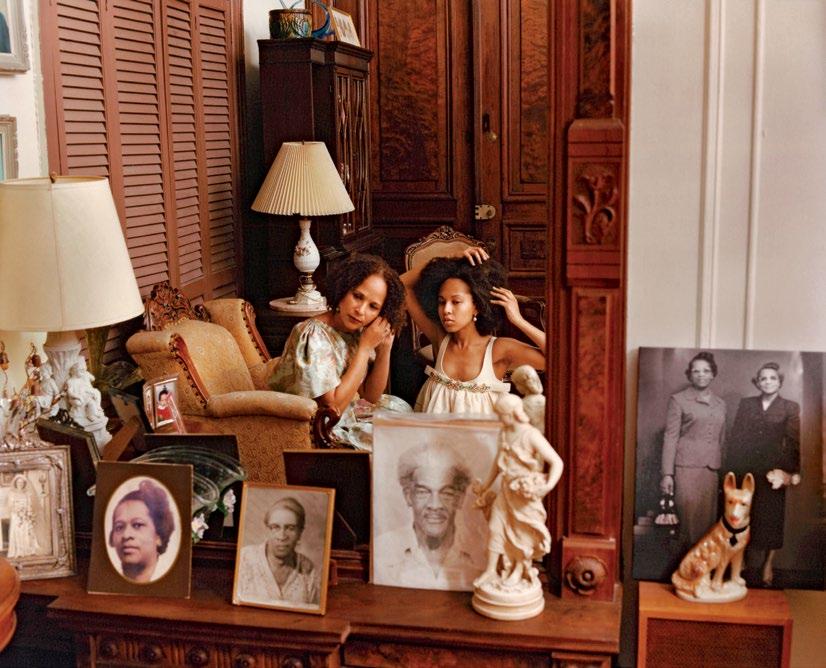

For this issue, one writer selects a treasured cultural artifact and holds it up to the light, reflecting on the revelations it has sparked, the nostalgia it conjures, and the deep-seated urges it articulates.

IN HER WRITING, DURGA CHEW-BOSE REVELS IN THE MINUTE. STANDING ON THE PRECIPICE OF HER OWN FILMMAKING DEBUT, SHE EXPOUNDS ON THE HUMID MELANCHOLY OF OLIVIER ASSAYAS’S 2008 FILM SUMMER HOURS.

A little over a year ago, I found myself wandering the beautiful chaos of Paris’s Marché aux Puces de Saint-Ouen—a garage-like maze of mid-century design, chrome and orange flourishes, teak tables and chairs, and catch-all dishes on every surface. I was in search of stuff —the kind that would adorn the French villa where my debut film, a contemporary adaptation of Françoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse, is set.

I was accompanied by my production designer, François-Renaud Labarthe, an artist whose work has, over the years, influenced me greatly. He is a master of just-so clutter, of building rich worlds with everyday charm. A desk must have piles, a bookshelf must have sun-faded spines, a summer movie must have al fresco dining.

This brings me to Olivier Assayas’s Summer Hours, one of my favorite movies, brought to life in part by Labarthe. The 2008 film, which is about memory and loss following the death of a family’s matriarch, delicately captures intergenerational conflict—not with dramatic strokes, but with a meditative touch that exposes sentimentality’s hold on our relationship to time.

When I think of Summer Hours, I see the color green, almost garish in the midday light.

“When I think of Summer Hours, I see the color green, almost garish in the midday light. I see a lonesome blue prior to nightfall. I see the doors left open to accommodate a breeze.”

I see a lonesome blue prior to nightfall. I see the doors left open to accommodate a breeze. I see the large silver-leaf serving plate Juliette Binoche admires in one of the movie’s most tender moments. I see teenage grandchildren occupying a crumbling country house one last time. I hear the names “Louis Majorelle” and “Josef Hoffmann,” designers whose furniture plays a significant role in the movie—as vehicles, as metaphors. I see a family’s future

neglecting its past, and how summer’s glare accelerates the fading process while reviving old secrets and ghosts.

Summer, I feel, is best enjoyed in the dark. By virtue of sheer contrast, the season blooms in a movie theater—growing wild, tangling itself into our imagination as something fresh and bittersweet. The movie ends. You leave the theater, forced to squint.

In 1978, Banana Republic was established to dress travelers headed out on safari. The brand’s current iteration is a far cry from its outfitter origins, trending more urban chic than great outdoors.

Banana Republic Home, a recent arm of the over-40-year-old label, intends to bridge the gap between the two worlds. The new line— which debuted last year with an array of bedroom, living room, and dining room

furniture, as well as lighting and home décor—is perfectly suited to a breezy, indoor-outdoor lifestyle, a reimagined revival of the brand’s founding ethos.

Last April, guests at CULTURED ’s CULT 100 party—which honored the magazine’s inaugural list of 100 changemakers across the creative industries—had the opportunity to experience the best of BR Home, the event’s exclusive design partner, in person.

Nestled in the Renzo Piano–designed atrium of New York’s Morgan Library and Museum, a curated selection of BR Home pieces played host to many an intimate moment, with the likes of Moses Sumney, Kelsey Lu, and Quil Lemons reclining on an oversized white couch. When the night came to an end, guests departed their cozy respites adorned with merino wool pillows and throws, making their way back into the urban jungle.

by Krista

It only took a single year on the market for the Lost Explorer, a boutique mezcal brand, to become the “world’s most-awarded mezcal.” Among its recent accomplishments, the Oaxacan spirit line, founded in 2020, served as the exclusive mezcal partner of CUTURED’s CULT 100 event—a testament to its creative spirit and ingenuity.

Guests of the magazine sampled the fruits of the brand’s lavishly awarded labor firsthand this past April. At a bar nestled in the booklined halls of the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, the Lost Explorer plied guests with samples of artisanal spirits, accompanied by delicate slices of apple and chocolate. The Lost Explorer’s sustainably made, small-batch agave spirits celebrate the biodiversity of its Mexican homeland.

“Mezcal had an almost mystical allure to me—the provenance of the plant, the artisanal craft, its relationship to the people of Mexico and mother earth.”

—DAVID DE ROTHSCHILD

This ethos reflects co-founder and conservationist David de Rothschild’s enduring dedication to pushing the environmental movement toward inclusive and inspiring new heights.

“It had an almost mystical allure to me—the provenance of the plant, the artisanal craft, its relationship to the people of Mexico and mother earth,” de Rothschild has said of his own discovery of mezcal. Thus, the Lost Explorer was born, quickly bringing on a multigenerational family of distillers to oversee the process, and planting three wild agaves for every one they hand-harvest. “The human-nature balance is like no other and it is the truest form of a spirit. It still fascinates me,” he added, “to the point where I have become somewhat obsessed by it.”

The first major U.S. exhibition of Vivian Maier, a mysterious artist looking for the extraordinary in the depths of the ordinary.

and culture.

The exhibition is supported by Women In Motion, a Kering program that shines a light on women in arts Image: Self-Portrait, New York, NY, 1954 © Estate of Vivian Maier, Courtesy of Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, NY

It is the rare brand that sends out an 814-page book as a runway invitation. That is exactly what Valentino did last year when it mailed copies of Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life to guests ahead of its men’s Spring/Summer 2024 show.

The Italian fashion house has continually reaffirmed its dedication to supporting contemporary wordsmiths, a relationship that began when Valentino himself took Diana Vreeland as one of his most influential muses.

For a 2021 campaign, the brand gave literary heavyweights Donna Tartt, Ocean Vuong, and Raven Leilani a simple prompt: Fill a single

The Italian fashion house has continually reaffirmed its dedication to supporting contemporary wordsmiths.

blank page with their musings on the poetry of fashion. More recently, Valentino partnered with CULTURED for the magazine’s CULT 100 event last April, fêteing an inaugural list of 100 cultural figures in the worlds of art, film, food, fashion, and literature. Vuong, one

of the issue’s cover stars, took the stage for a reading from his second poetry collection, Time Is a Mother, wearing a Valentino look from the men’s Spring/Summer 2024 collection.

In May, Valentino’s decades-deep commitment to the printed word led to the house’s support of the International Booker Prize ceremony, accompanied by a pledge to send 500 sets of the shortlisted books to libraries across the United Kingdom. The purpose of the partnership was simple, according to Maison Valentino CEO Jacopo Venturini: to “strengthen the house’s deep connection to the world of literature.”

Aspen Ice Garden JULY 30AUGUST 3 2024

Intersect Aspen Art and Design Fair returns to the Aspen Ice Garden this summer, presenting a dynamic mix of modern and contemporary art and design.

Running for over a decade, the fair has seen newfound energy and excitement under the management of Intersect Art and Design, now in its fourth edition. Committed to building community and connectivity, Intersect offers opportunities for dialogue, engagement, and inspiration through its cultural partnerships, programming, and curatorial vision.

For more information visit intersectaspen.com

Shown: Mixed media and resin work by Aurel K. Basedow; candlesticks and urn by Andrea Marquis; and console with cabinets by Gary Magakis. Courtesy of the artists and Todd Merrill Studio.When Louis Vuitton Men’s Creative Director Pharrell Williams debuted his Spring/Summer 2024 collection last year, it was a lightbulb moment for the house’s Master Perfumer Jacques Cavallier Belletrud.

Naturally, he supposed, Williams would have a bold idea for a fragrance. He was right: LVERS, the product of a recent collaboration between Williams and Cavallier Belletrud, is inspired by light itself.

The fragrance is bright and cheery, with notes of cedar to ground it and touches of sandalwood and bergamot to add warmth and zest. Galbanum—the unlikely star—provides a wild greenness that captures the positive, masculine vibe Williams and Cavallier Belletrud set out to create.

It’s daylight made manifest.

“Making perfume is all about showcasing the beauty of the raw ingredients and finding the balance between emotion, imagination, and reality.”

—JACQUES CAVALLIER BELLETRUD

Photography by

Louis Vuitton

Photography by

Louis Vuitton

“Pharrell asked me, ‘What does sunlight smell like?’

This fragrance is a poetic and metaphorical version of the answer

to that question.”—JACQUES CAVALLIER BELLETRUD

Jewelry is imbued—perhaps more than anything else we wear—with potent emotional power.

In the best of cases, it can be hard to know where a well-made piece of jewelry ends and an art object begins. Designers increasingly

seek not just to answer this question, but to play in the space it creates, the tension between intimacy and distance adding new dimension to their craft. Blurring the line between wearable heirlooms and everyday objects, five creators reveal their findings.

BY ALI PEW“Jewelry-making felt like a natural extension of my design inclination, a creative epiphany of sorts. I found that immersing myself in the atelier, sculpting metal and molding wax, provided the best means to define my artistic language.”

—CHARLOTTE CHESNAIS

Objects become offerings in the hands of Alighieri’s Rosh Mahtani, evoking life’s arc through carefully crafted metals. A silver skeleton barrette is the delicacy of mortality made manifest, and an homage to the beauty of precarity.

“Ritual plays a big part in my life, and jewelry is very ritualistic. We wear certain pieces to remind us of a person, to make us feel brave, to symbolize a relationship or a time in our life.”

—ROSH MAHTANIMixing surrealist flair with humorous aplomb, Sophie Buhai reconceives personal keepsakes as covetable treasures. A joint holder and a flask become artful adornments as worthy of an evening out as being passed down.

“There was a time when it was common to have beautiful everyday objects —a well-made silver pen, a lighter, a cigarette case. We can still do that today, in a modern way.”

—SOPHIE BUHAI

One of the last century’s most iconic and enduring It-girls, Elsa Peretti’s designs for Tiffany & Co.—homages to the humility and purity of life’s origins—are sculptural works in their own right. With a simple bean-inspired pillbox, Peretti masters the jewelry-object divide, creating a piece at once intimate and functional.

PSYCHIC STAMINA

JUNE 1 JULY 26, 2024

Cartier Libre crafts embodiments of the unexpected. A carabiner undergoes a glowing metamorphosis, becoming a watch dappled in snow-set diamonds—at once beautiful and functional.

“Each creation could easily stand on its own as a beautiful piece of jewelry, but we’ve fit movements where they don’t necessarily ‘belong.’ The watch’s presence is part of the surprise.”

—MARIE LAURE CÉRÈDE

When jewelry designer Savannah Friedkin founded her eponymous brand this spring, she set her sights on two goals: environmental sustainability and personal significance.

By ALYSON KRUEGER by JESSE GLAZZARD

Savannah Friedkin has long felt a calling to design fine jewelry. “It’s a form of self-expression,” she muses. “I’ve never owned—or seen—a piece of jewelry that honors all of the unique facets of what makes me beautiful: the broken pieces, the twists and turns in my life.”

But as someone who grew up committed to conservation—her father, Dan Friedkin, is the chairman and CEO of Friedkin Group, which owns Auberge Resorts Collection and champions conservation efforts in both Texas and Tanzania—she struggled to find a fine jewelry company that reflected her values. “It was clear to me when I was looking for my path in fine jewelry that there were very few brands, if any, that were focused on sustainability,” she says. “When a brand did claim to be focused on sustainability, their claims weren’t very transparent—or, on occasion, even consisted of misinformation.”

So, in the spring of 2024, she launched her own namesake brand for people who love the planet. Friedkin follows strict guidelines. For one thing,

she only uses earth-friendly materials, including recycled gold and carbon-neutral lab-grown diamonds. “Our diamonds are 100 percent traceable,” she says. “I have personally seen where they are grown, cut, and set.” Each supplier and manufacturer the brand employs undergoes an independent audit to ensure they comply with green standards.

But the pieces can’t simply be beautiful. They must serve as vessels for deep personal meaning. Broken, the first collection Friedkin designed, is reflective of “the resilience inherent in women. I believe the broken within all of us can be beautiful—and should be celebrated,” she adds. The pieces feature a crack motif, a message to the wearer that “the negative space in each of us, the things left unseen, are often some of the most beautiful and interesting elements.”

Next came Emergence, a collection inspired by wild plants that grow in the cracks of buildings or sidewalks. It’s an image that the designer finds powerful: “It reminds me of when you’re going through a difficult time, in a situation you

never thought you would be in. You take one step forward day-by-day, finding your path over time and eventually learning to flourish.”

SAV, the third collection, taps into a brighter facet of the human experience. Put plainly, it’s about “the simple and fun,” notes the designer.

Friedkin hopes that the more people interact with her work—she currently has a pop-up shop traveling the United States that will make stops at Hotel Jerome in Aspen; the Mayflower Inn and Spa in Litchfield County, Connecticut; the Barn, SoulCycle’s base in Bridgehampton; and Bowie House in Fort Worth, Texas—the more she can inspire people to share her approach to sustainable (and meaningful) jewelry-making standards.

“I believe the industry is in the process of a major shift,” asserts Friedkin. In the end, she muses, what matters most is that that one’s treasured jewelry “has zero impact on the environment and only positive impacts on human beings.”

“CRAFTED

“When you go in and look at 10 years of work, you’re sort of confronted with what you’ve achieved,” says Jonathan Anderson, the creative director of the fashion label Loewe. He was speaking over a midday roundtable in Shanghai this past March, the day before the opening of “Crafted World,” a fashion and art proto-retrospective that rather jubilantly charts the history and aesthetic universe of the Spanish label. It is the house’s first major exhibition, and is expected to travel the world in 2024.

The unveiling of “Crafted World” signaled the next chapter in Loewe’s evolving artistic saga: Since 2016, the company’s foundation has presented an annual Craft Prize for emerging designers, and the brand underwrote the 2024 Costume Institute exhibition “Sleeping Beauties” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It also speaks to luxury fashion’s increasingly ubiquitous forays into exhibition-style activations. Louis Vuitton, for example, has its own foundation in Paris, and Dior has a gallery space, tucked beside its Avenue Montaigne flagship, that presents seasonal edits of archival pieces and paraphernalia.

While the exhibition begins at Loewe’s conception—1846, making it the oldest house in LVMH’s portfolio—much of the show is dedicated to the tenure of Anderson himself, who took the helm in 2013 (an unusually lengthy run in this line of work). “I’ve sold this to the press so many times—that every collection is different and is something brand-new,” Anderson said, “but when I see them all together in the room, it’s very interesting to me

that there is a language in the make of the clothing. There is a language to it all, somehow.” The exhibition’s emphasis on Anderson-era Loewe is a good thing—and, in the opinion of this writer, his sentiment on the subject is quite humble. His oeuvre may feature its fair share of veers and wiggles, but it has always been fluent in one dialect: market-friendly, highly artful eclecticism that emphasizes artisanal excellence in all its forms.

It’s also Anderson who has propelled the house beyond the gilded confines of high fashion and into the cultural mainstream. This has largely been done through cleverly positioned partnerships—for example, with renowned animator Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli and the estate of Surrealist painter Maruja Mallo. The designer also costumed this summer’s Challengers, directed by Luca Guadagnino, and is releasing a few key pieces under the Loewe label. He inaugurated the aforementioned Craft Prize—the seventh edition of which debuted last May at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris—three years into his tenure at the brand.

Moreover, under the Irish designer’s leadership, Loewe has grown into a business worth more than a billion dollars—a degree of growth consistently underscored by the care and attention it takes to actually craft a product, versus churning it out in a factory. What other mass luxury designer in today’s market would sell a handmade leather purse in the shape of an elephant? (You can purchase multiple sizes at the “Crafted World” gift shop.)

“Loewe was very tight as a brand ... It had crippled itself somehow through the idea of being a luxury brand,” mused Anderson about the house’s uneven past. “But when I looked into the archive and thought about my own experience with Spanish culture, I realized there’s a lot of fun in it.”

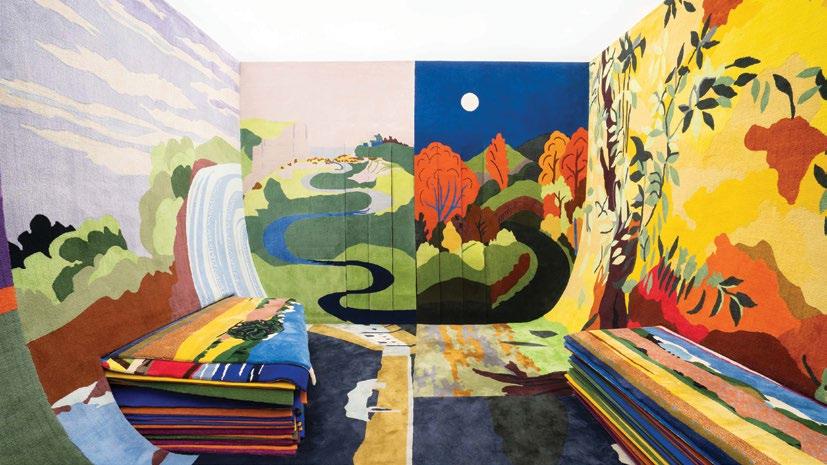

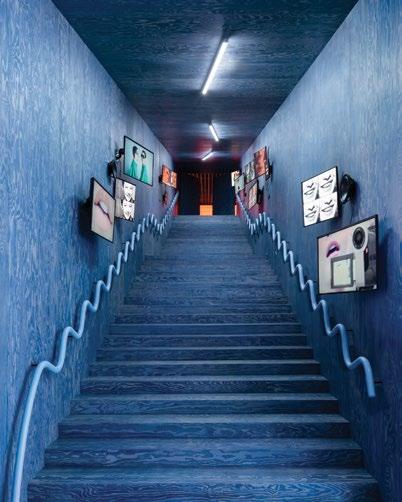

Fun—good humor, an embrace of loud color, and even a hint of whimsy and kitsch—is at the heart of Anderson’s Loeweverse and, by extension, “Crafted World.” Upon entry, a stairwell tunnel layered with screens blares out the correct pronunciation of Loewe (“Lo-eh-vay”). Upon reaching the other end, visitors are “confronted” with an installation of polychrome chambers presenting visuals including, but hardly limited to, Rihanna’s 2023 Super Bowl halftime-show look, the brand’s signature leather-intarsia “Puzzle” bags, toolkits used by craftspeople in Loewe’s Madrid workshops, and rare pieces from Anderson’s collaboration with Studio Ghibli. Elsewhere, viewers catch glimpses of rarefied machinery, such as leather-thrashing arms that test bags’ durability.

What becomes clear through these vignettes, at varying scales and levels of technical sophistication, is Loewe’s commitment to creating for and continually adding dimensions to this titular “crafted world.” When asked about his approach to and relationship with that narrative, Anderson concluded, “There’s something that becomes quite twisted. Craft almost becomes a character, in and of itself.”

“THERE IS A LANGUAGE IN THE MAKE OF THE CLOTHING. THERE IS A LANGUAGE TO IT ALL, SOMEHOW.” —JONATHAN ANDERSON

“LOEWE

HAD CRIPPLED ITSELF SOMEHOW THROUGH THE IDEA OF BEING A LUXURY BRAND. BUT WHEN I LOOKED INTO THE ARCHIVE AND THOUGHT ABOUT MY OWN EXPERIENCE WITH SPANISH CULTURE, I REALIZED THERE’S A LOT OF FUN IN IT.” —JONATHAN ANDERSON

“LO-WEH-VAY”

SEVEN YEARS SINCE ITS FOUNDERS CRAFTED THEIR FIRST BATCH OF TEQUILA FOR A FRIEND’S WEDDING, LALO REMAINS COMMITTED TO ITS SMALL-BATCH ROOTS—AND TO BEING THE DRINK THAT BRINGS FRIENDS TOGETHER.

BY JAYNE O’DYWER

by

Photography Pablo AstorgaThe art of gift-giving is a delicate one. Both intensely personal and, at times, performative, the practice calls on the giver to encapsulate a relationship. In 2017, LALO tequila co-founders Lalo González and David R. Carballido found themselves walking this tightrope when they attended a friend’s wedding in Guadalajara.

Rather than buying an object for the newlyweds, the two men decided to make their contribution in another way—by crafting a small batch of tequila for guests to imbibe during the festivities, becoming part of the day’s rituals and celebrations. It was the perfect answer to a very simple question: What do you give a friend?

“Mexico really is what’s next. It used to be Berlin, but fast-forward to today, and Mexico has taken over that role as a pioneer of new things.”

“We were starting to create this effect of, ‘You need to be our friend in order to have LALO,’ because we were not a big company… It became, by accident, something so exclusive,” says Carballido.

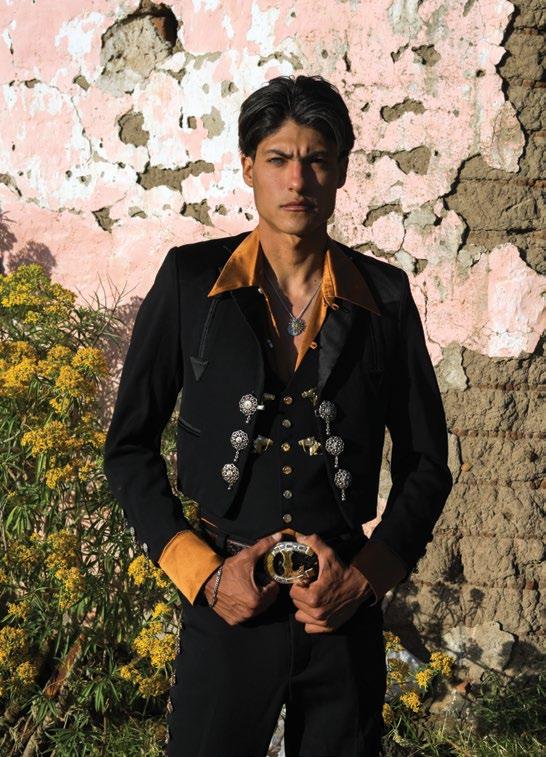

This thoughtful inquiry doesn’t just continue to steer the duo’s company. It also grounds their latest campaign, “See New,” an invitation to enjoy the flavors of modern Mexico and a sign of the brand’s evolution from craft leader to mainstream premium. “If you want magic to happen in your life, you have to go down a different road every day,” reasons Creative Director Antonio Navas. “When you do that, you’re breaking with routine.” Inspired by the striking photography of Flor Garduño, the bold compositions of José Clemente Orozco, and the lively architecture of Luis Barragán, the campaign features models posing against the vibrant backdrops of Mexico City, Guadalajara, Los Altos de Jalisco, and Valle de Bravo. All the better to situate LALO in the vibrant culture from which it was produced.

“Mexico really is what’s next,” asserts Navas. “It used to be Berlin, but fast-forward to today, and Mexico has taken over that role as a pioneer of new things.”

For “See New,” the brand tapped Mexican fashion designer Patricio Campillo, who dressed the models in his Charro outfits, the spread collars and horsehead waistcoat buttons adding both referential and reverent flair. All campaign videos are scored with music from a Mexican composer. At the center is LALO, in a sleek glass bottle with a label that speaks to the brand’s ethos—pure, elegant, and fresh.

While the brand has evolved over the last five years, González and Carbadillo have maintained their commitment to the

standard they set for themselves back in 2017—spirits made with care, as if for a close friend. It’s a nod to the family tradition that González’s grandfather—Don Julio himself—created three generations ago: to make tequila not only a premium spirit but also one that many would choose to drink. LALO, which contains no additives, combines only three ingredients: agave, deep well water, and champagne yeast, distilled twice to secure its rich flavor. In a market that pushes increasingly diluted tequila, and celebrity branding, LALO remains committed to its original calling—to be a spirit by Mexicans for Mexicans. “We enjoy the beauties of Mexico on a daily basis,” muses Navas. “When you go to Mexico, that’s when you say, ‘Okay, now I get why people can’t stop talking about it.’”

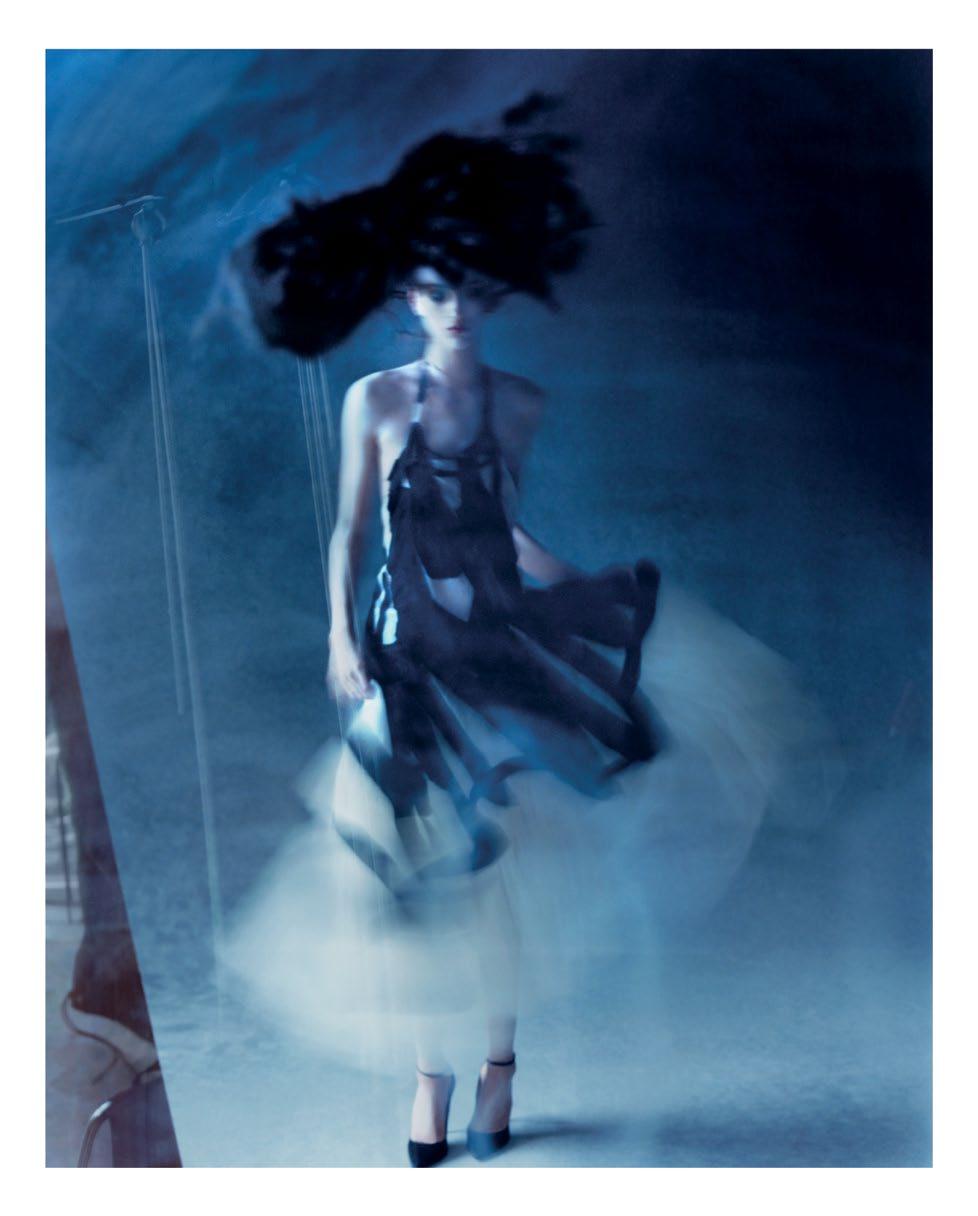

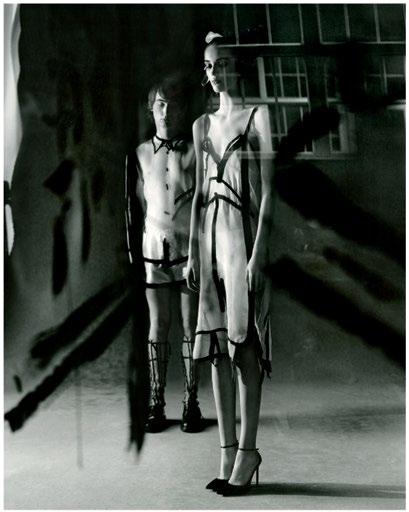

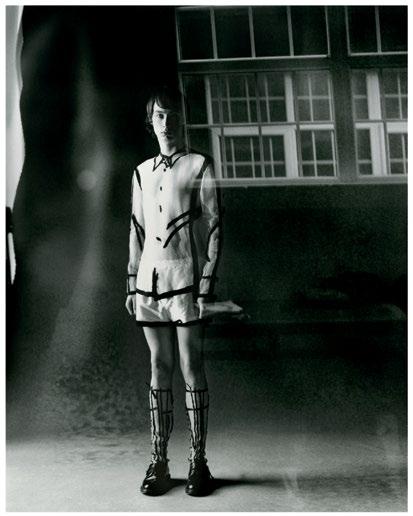

IN THE WHIRLWIND YEAR SINCE STEVE O SMITH DEBUTED HIS THESIS COLLECTION, HIS DESIGNS HAVE MADE THE RED CARPET ROUNDS. UP NEXT? LEARNING TO SIT STILL.

“FOR

BUT FOR ME, IT’S A WEAPON … I CAN DO WHATEVER I WANT, WHICH IS AMAZING AND LIBERATING.”—STEVE O SMITH

WHEN WE MEET, Steve O Smith is facing one of the biggest moments of his career. He’s zipping around his East London living room turned studio, chipping away at a dauntingly long to-do list. In a few days, his designs would make their Met Gala debut, appearing on actor Eddie Redmayne and his wife, Hannah Bagshawe. The space is suitably chaotic—a whirlwind of pins, paper, discarded fabrics, and tobacco dust. Lining the walls are images from his Fall/Winter 2024 lookbook, alongside his frenzied original sketches. “I do good work when I’m pissed off,” Smith lets out, gesturing toward his drawings. “I like to get into this state where it’s free-flowing, and I’m listening to music quite loudly and moving around. I’m always standing up—I never sit down to draw.”

It has been a transformative few years for Smith. After graduating from Central Saint Martins in 2022, the British designer, 32, has experienced a string of back-to-back pinch-me moments: His MA collection was swiftly spotted by stylist Harry Lambert, who called in his black-and-white figure suit for Harry Styles’s “Daylight” video. “It was quite shocking,” Smith remembers. (The same suit later made the fashion editorial rounds, appearing on the likes of Cate Blanchett.) But the designer’s most recent Fall/Winter 2024 collection— which was also his official debut—sees his work reach new heights of refinement. Crafted from black silk and organza, Smith’s pieces feel more like enchanted life drawings, scribbles lurching off the pages of his sketchbook and scrawling themselves onto the body. It tracks that his main inspirations for the collection were 20th-century caricatures and German Expressionism—namely George Grosz and his “sinister” drawings of the Weimar Republic.

“There’s something funny, a bit fucked-up about them,” he says, eagerly grabbing a book of the artist’s early sketches. He flicks through the pages, pausing to study a drawing of three angry soldiers. “There’s something borderline ludicrous about the entire concept, which is what keeps me entertained … It feels worryingly current.”

Smith was born in Amsterdam but brought up in the U.K. He studied fashion at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he learned basic craftsmanship, including how to fit, sew, and pattern cut. It was a sturdy yet traditional foundation, but when Smith returned to London to start his own line in 2017, it didn’t take long for him to hit a wall. “I’d been doing wholesale, but I wanted to go back to school because I felt like there was more potential,” he recalls. “And then the pandemic happened.” Burnt out from the “stressful and time-consuming” nature of wholesale, he began a master’s degree at Central Saint Martins— followed by a 10-week stint at the Royal Drawing School, where he rediscovered his childhood passion. “The tutors were like, ‘You’re doing something really interesting here, and you should try and translate that into what you’re making,’” he says, before laughing. “And so I did, with a lot of failures at first.”

Smith soon learned to surrender to his instincts. He flicks at a pile of papers on his worktable—hundreds of pages of drawings— and admits that he typically spends up to 12 hours a day doing rapid sketches, growing increasingly agitated in the process. “At a certain point, there’ll be an emotion in it,” he says. “The last few drawings I did, I was pressing so hard with the graphite stick that you could smell it. I was really attacking the

page.” He then applies this same process to his fabric-cutting, treating the material as an extension of the graphite. “I just start laying the fabric at the same speed that I was laying the marks down on paper, and then stitching them down.” The resulting designs, like his drawings, are pure id, alive with emotion and thrumming with energy.

The goal for the future, though, is to slow down. Smith admits that his natural state is to “move quickly forward,” but his main priority now is to give himself the space and time to nurture these more primal creative instincts. “I’m just able to draw and make the things I want to make, and I’m happy,” he says. “That’s partly from failing the first time around—I realized the things that I thought I wanted were not what I wanted at all.” His process may be slower and more intricate, but he sees it as a small price to pay. “For some people, creative freedom can be scary. But for me, it’s a weapon … I can do whatever I want, which is amazing and liberating.”

It leaves Smith with a blank canvas of possibility, an intimidating prospect for any designer. But for him, it’s a chance to dig deeper. With the chaos of the Met Gala under his belt, he’s planning a return to his sketchbooks and a “refinement” of the techniques he’s already mastered, particularly around form and gesture. That doesn’t mean he won’t be trying something new, though. The designer’s next collection, he notes elusively, will experiment with “tone”—a new territory—and a focus on color is on the horizon as well. But he doesn’t want to get ahead of himself. “Right now, I’m actually forcing myself to try and stay still, right where I’m at.”

BY ANNIE ARMSTRONG

BY ANNIE ARMSTRONG

FIVE NEW YORKERS REFLECT ON HOW THEY ATTAINED THE CITY’S MOST COVETED ACCOLADE.

Becoming a regular at a New York restaurant is an art. To earn the experience of walking into one’s preferred establishment and being greeted by name, seated immediately, and offered “the usual” is a trophy that very few have the tact, savvy, and dedication to win.

There is no one path to this coveted prize. Consider the SoHo resident who routinely brings ice-cold bottles of water to the host stand at Balthazar in search of preferential treatment, the start-up founder who sends late-night pizzas to the staff at Tribeca hotspot the Blond every few weeks, or the keto-dieter who ascended to first-name basis with a Union Square farmers market vendor by buying “illegal” raw milk under the table. Every regular has their own process, but a few time-honored rules of thumb emerge: Visit at least once a week. Order consistently. Leave a healthy tip, of course.

These days, the dominance of apps like Resy threatens to snuff out regular culture. Reservations have become a cottage industry, with enterprising college students selling coveted tables for thousands of dollars on a burgeoning secondary market. But fear not—you can still bypass the host stand the old-fashioned way. In the pages that follow, five New Yorkers dish on the rituals and relics of the regular lifestyle.

ARTIST, 35

NEIGHBORHOOD: CHINATOWN

RESTAURANT OF CHOICE: DIMES, 49 CANAL STREET

“Dimes is like a portal. I come here to get my matcha oat milk latte and a peanut butter cookie once or twice a week.

I remember hearing that Sabrina De Sousa [Dimes’s co-owner] was starting a place in Chinatown back in 2013. What we now know as Dimes Deli was just Dimes back then, and it was really cute. Dimes probably grew into something they didn’t intend for it to become, but that’s like art, or like anything organic— if you keep watering something and giving it love, it will grow.

The fact that this area was crowned ‘Dimes Square’ is tongue-in-cheek. I’m a pretentious motherfucker, I’m an artist. I love shit like this—the blending of the mainstream and subcultures. Dimes is a really interesting case study in that way.”

PHOTOGRAPHER, 44

NEIGHBORHOOD: CHINATOWN

RESTAURANT OF CHOICE: HALAL CART, BROADWAY (CHANGING LOCATIONS)

“I’m not trying to congratulate myself here, but I just happened to walk by this guy’s cart as he was being robbed. I made a video of it, helped him communicate with the police, and gave him Band-Aids and some antibiotic ointment. This was maybe a year ago. I felt bad for him because I had seen him getting hassled before. He’s kind of a sitting duck, and his cart’s earnings are his family’s whole income. This one time I happened to be there when it escalated.

So now, he moved his cart to SoHo, and I see him every day. We wave and he flags me down, ‘My friend! Take a drink! Have some food!’ Once in a while I’ll take a seltzer to be a good sport. His food is great. I get chicken and rice.

But really for me, it’s just a microcosm of the great pleasure of New York. I spend so much time in transit that, on some level, I’m a regular all over town. This is one of those great indications of that.”

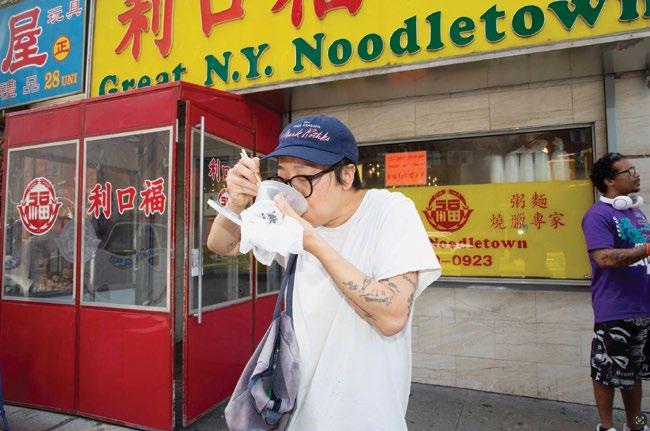

ARTIST, 46

NEIGHBORHOOD: BED-STUY

RESTAURANT OF CHOICE: GREAT N.Y. NOODLETOWN, 28 BOWERY

“My parents used to take me into Chinatown as a kid. As a teenager and later in my 20s, Noodletown was the late-night spot. As places changed and closed down, it went from a standard procedure, utilitarian restaurant to one of the best places around.

I go three or four times a month. If you have an adventurous friend, you can get the good stuff like soft-shell crab, and the crispy noodles are amazing.

If you’re by yourself, you get the noodle soup for eight bucks, and you’re in and out in 15 or 20 minutes. There’s a grouchy guy who knows me there, and a couple servers, but they leave you alone with your thoughts and your food. I get social anxiety sometimes, and it’s nice that they do not want to chit-chat at all. There’s this tension between sympathy and judgment sometimes when you eat alone, but that is not the situation at Noodletown.”

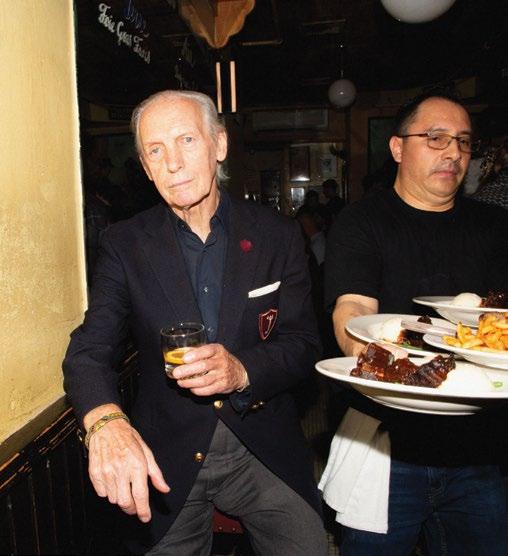

PAINTER, PHOTOGRAPHER, BARTENDER AT PAUL’S BABY GRAND, 74

NEIGHBORHOOD: EAST VILLAGE

RESTAURANT OF CHOICE: LUCIEN, 14 1ST AVENUE

“I’ve been coming here for 26 years, since it was a small, mom-and-pop French restaurant. You could always get a table, and there was no music. It has changed a lot since then. Zac, Lucien’s son, modernized it when he took it over and made it a very cool place. And I’m cool, so that’s why I’m here.

When I eat at Lucien, I usually have octopus and the French soup. It’s based on the Marseille soupe de poisson traditionnelle.

I worked here for a short time as a bartender, but I didn’t last long. I got fired by Zac’s mum. But it’s my local place, and I’m a Francophile. The food is awesome; it has never changed. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be in business.

I usually come twice a week. I’m a creature of habit; I never leave this eight-block radius. The only time I go Uptown is to go to Bemelmans Bar. When friends say to me, ‘Let’s go someplace besides your usual places,’ I ask, ‘Where?’ and they say, ‘Oh, a place on 17th Street.’ I’ll say, ‘No, I’m not going Uptown.’”

FASHION DESIGNER, “I FOUNDED THE BUSINESS 42 YEARS AGO, WHICH MAKES ME 39.”

NEIGHBORHOOD: TRIBECA RESTAURANT OF CHOICE: PASTIS, 52 GANSEVOORT STREET

“I’m at Pastis as much as twice a week. I always like to sit in a booth if I’m not with a larger group. I used to go to the old Pastis too —I loved it there, and I was sad when it closed.

I go to Balthazar, Pastis, and Minetta Tavern, and they’re all excellent. But I like the Pastis steak the best—it’s more like a hanger steak, and I like the big slab of butter on it. I also love to go for breakfast—it’s always very chill —but I probably go there for lunch the most. It’s easy for me to get there from my office.

I’ve been friends with Keith McNally [the restaurateur behind the original Pastis and partner in the new location] for a long time. I’ve known him since he was manager of One Fifth. These past few years I’ve gotten closer with him, and I certainly read his Instagram! He’s fearless. Very fearless.

Restaurants are better when they’re more personal. When I go to a restaurant and it’s impersonal, I don’t feel like going back.”

4 5 1 2

Podcasting It-boys Nate Freeman and Benjamin Godsill have had their fair share of martinis and sashimi on the concentric art fair, gallery opening, and biennale circuits. Here, they share an insider’s list of establishments—from the down and dirty to the white glove—that feed the art world.

When we started the podcast Nota Bene in 2021, our plan was simple: Hit “record” and gab about the global contemporary art world. We wanted to pull back the curtain (just a little) on an insider’s dialogue, the kind of hushed conversation that bubbles up between a dealer and a gadabout during a vernissage. It would be flush with market insights and art historical intel, but also witty and gossipy, cutting and incisive, unfiltered and unsparing—“the podcast version,” we called it, “of a boozy lunch at Sant Ambroeus.”

What we didn’t realize was that so much of the art world’s chatter would actually be about lunch.

This checks out. Where the art world eats isn’t just a part of the narrative, it is the narrative. The 600-person fundraising luncheons, gala dinners, billionaire breakfast meetings, post-opening cocktail buyouts—you can’t talk about artists and their dealers without talking about where they break bread.

So Nota Bene quickly became as much about food as art. In a typical episode, fair and biennale prattle quickly descends into unapologetically name-droppy litanies of chef-owners and menu items, or gut reactions to seating charts and canapes. There’s lingo: The secret phone number to bypass a booked-solid Resy page is called a “batphone.” When bigwigs are seated in Siberia, we point it out. This blend of the culinary and the contemporary arts has found its audience—our listeners (the jet setters and aesthetes) often admit to falling in love with the art world in part for its kinship with the finer things.