THE NEW PROVOCATEURS

September/October 2024

CRASH AND BURN

Artist Sara Cwynar’s new film takes on car culture, to dizzying effect

HUDSON VALLEY HERO

Design and lifestyle maven Jenni Kayne opens the doors of her latest passion project: a blissful retreat in upstate New York.

GARTH GREENWELL’S THIRD ACT

With his first two novels, the author made his name as an unfiltered, intoxicating alchemist of gay physicality. His third book sees him enter new territory.

DRESS UP

The costume designers behind three major fall releases share the stories, challenges, and inspirations behind their most revealing looks.

FLESH, MUSCLE, BONE, AND SOUL

Architect Elizabeth Roberts and fashion designer Cecilie Bahnsen compare notes on creating opportunities for “accidental beauty.” 66 68 70 72 78 80

82

Over the last decade, Hong Kong–born couturier Robert Wun has made a name for himself by embracing the laboriousness and precarity of his craft.

NOT TOO PRECIOUS

THOMAS HOUSEAGO’S GRAVITY AND GRACE

The artist went through hell to find peace. His latest show in New York captures the journey with wrenching sincerity.

86

88

92

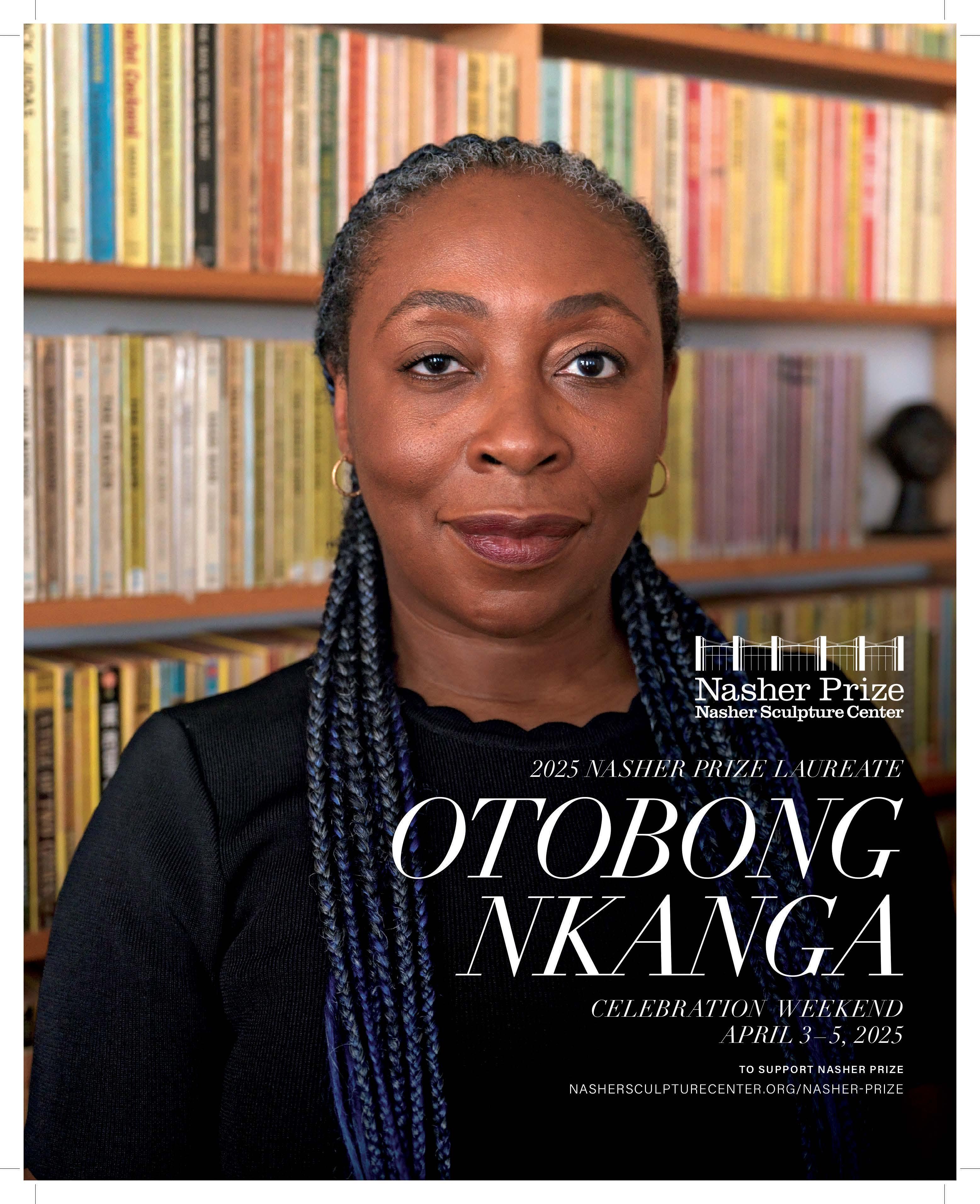

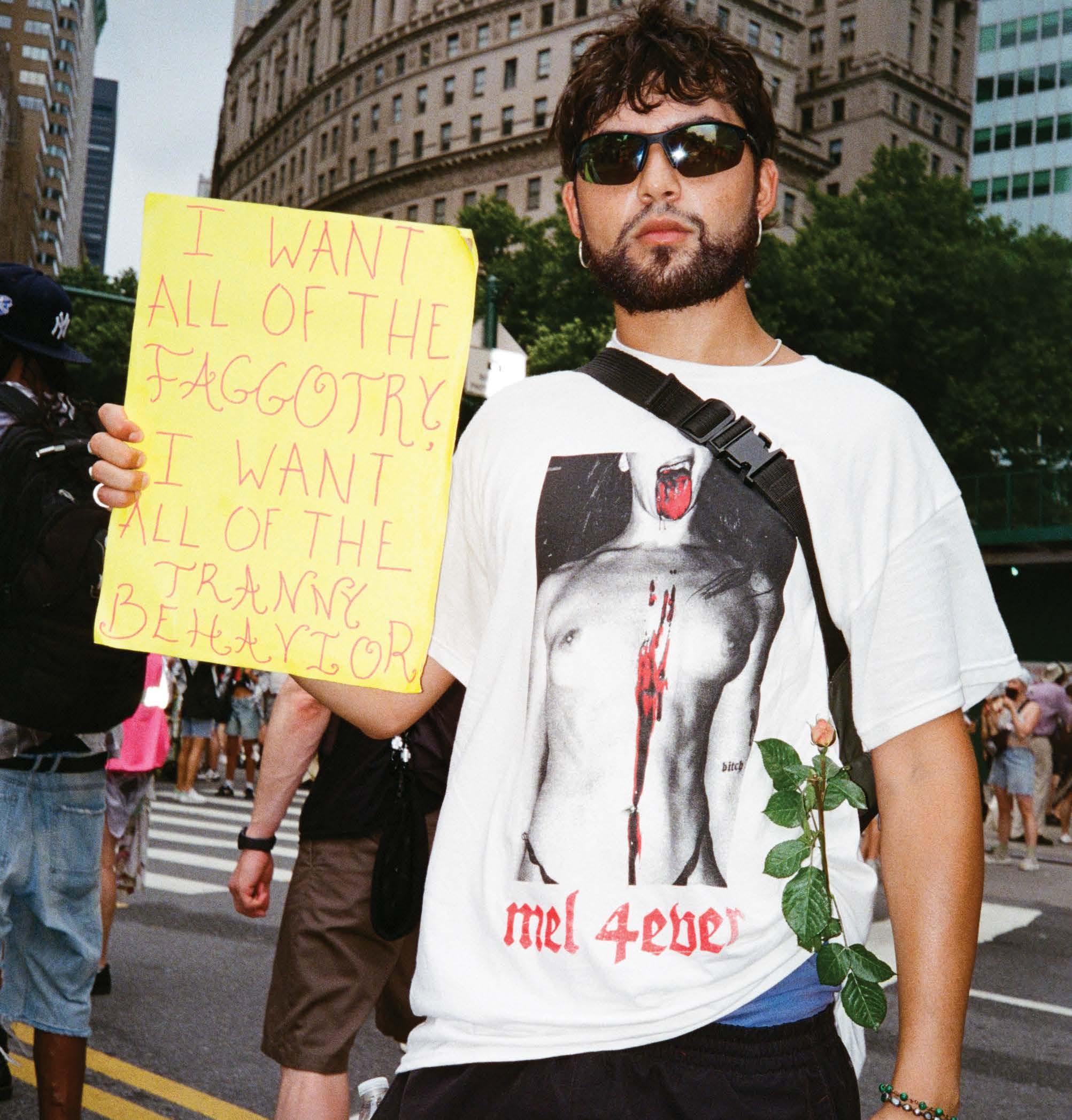

MEANS OF PROVOCATION Victor

Barragán and Betsy Johnson make work that tests the culture’s appetite for extremity.

MERIEM BENNANI’S TRAGICOMIC SWAG The artist sits down with her longtime co-conspirator Orian Barki to discuss her ambitious exhibition at the Fondazione Prada.

THE HEAD, THE HEART, AND THE HANDS This fall, Yvonne Wells’s renegade practice is encapsulated in a new monograph and two exhibitions.

AN ARTIST GETS HIS DUE Thomas

94

96

Schütte hasn’t had a major U.S. museum exhibition in more than two decades, but his influence looms large. A new MoMA show is setting out to prove it.

LET’S MANIFEST José Esparza Chong

Cuy and Guillermo Ruiz de Teresa are steering the Storefront for Art and Architecture toward its next chapter.

September/October 2024

98 100

102

106

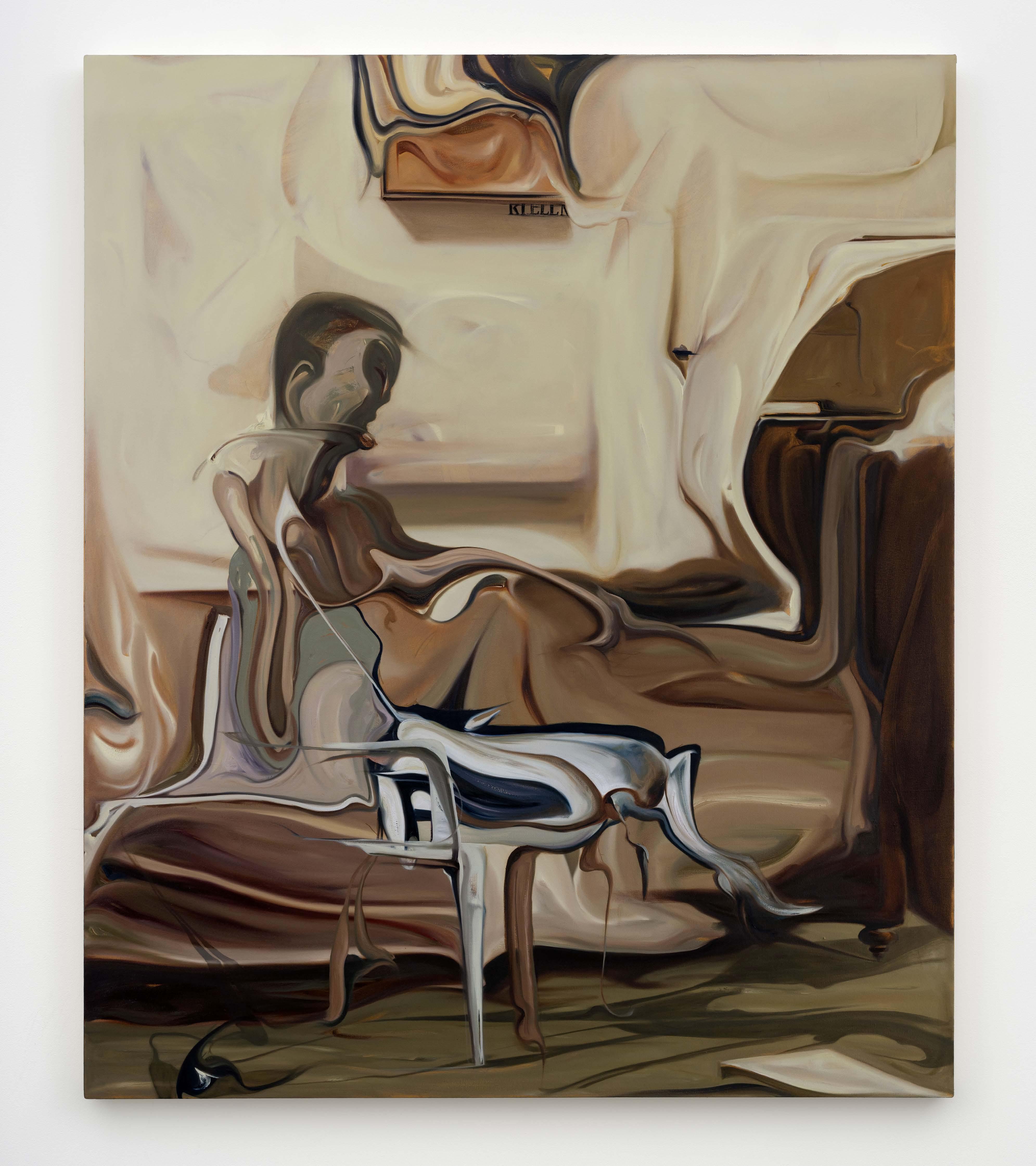

MAJA RUZNIC’S SPECULATIVE FICTIONS

Following her inclusion in the 2024 Whitney Biennial and a knockout solo show at Karma in New York, the New Mexico–based artist is bringing her ethereal paintings to Berlin.

ANTHEA HAMILTON AND SYLVIE FLEURY’S MATERIAL RECKONINGS

The two artists meet for the first time to unpack the ebbs and flows of their parallel practices and what they treasure about them.

INSIDE JEWELER OLIVIER REZA’S UPTOWN SANCTUARY

On New York’s Upper East Side, the French jewelry designer surrounds himself with works as precious as the gemstones he curates for his family maison.

MORGAN STEWART MCGRAW TRUSTS HER GUT

At home in Beverly Hills, the designer’s exacting eye has fostered an art collection as worldly as its steward.

108

112

116

THIS IS A HOME—NOT A MUSEUM

Nicole Hollis’s new book is dedicated to the subtle alchemy that unfolds when design meets art.

A LITTLE STRANGE, A LITTLE SEXY

Fresh off his win of the prestigious ANDAM award, the Australian designer Christopher Esber is already back to the grindstone.

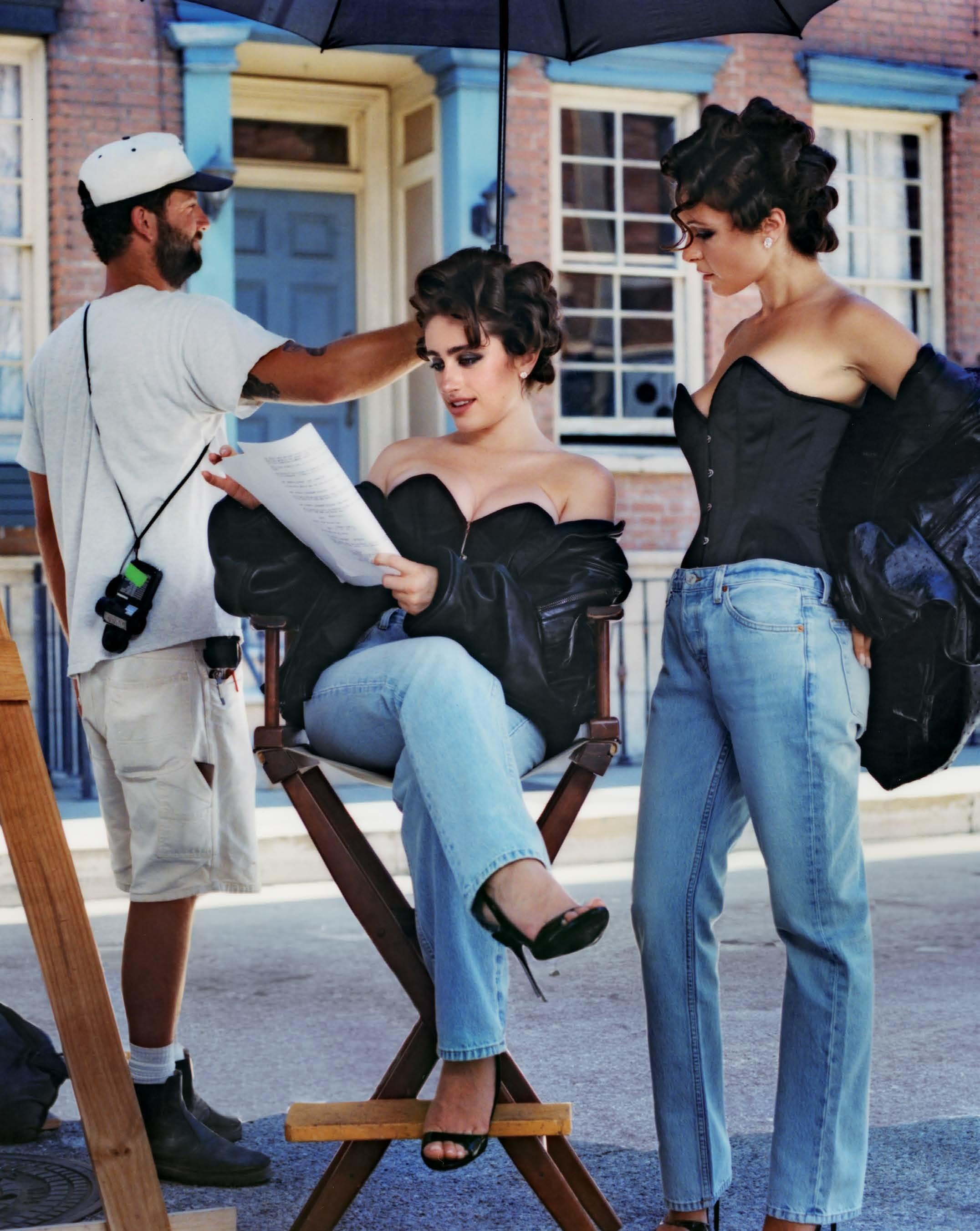

LISA TADDEO AND SHAILENE WOODLEY ON SEX, LONELINESS, AND THREE WOMEN Lisa Taddeo sits down with Shailene Woodley, who stars in the TV adaptation of the author’s breakout book.

118

125

140

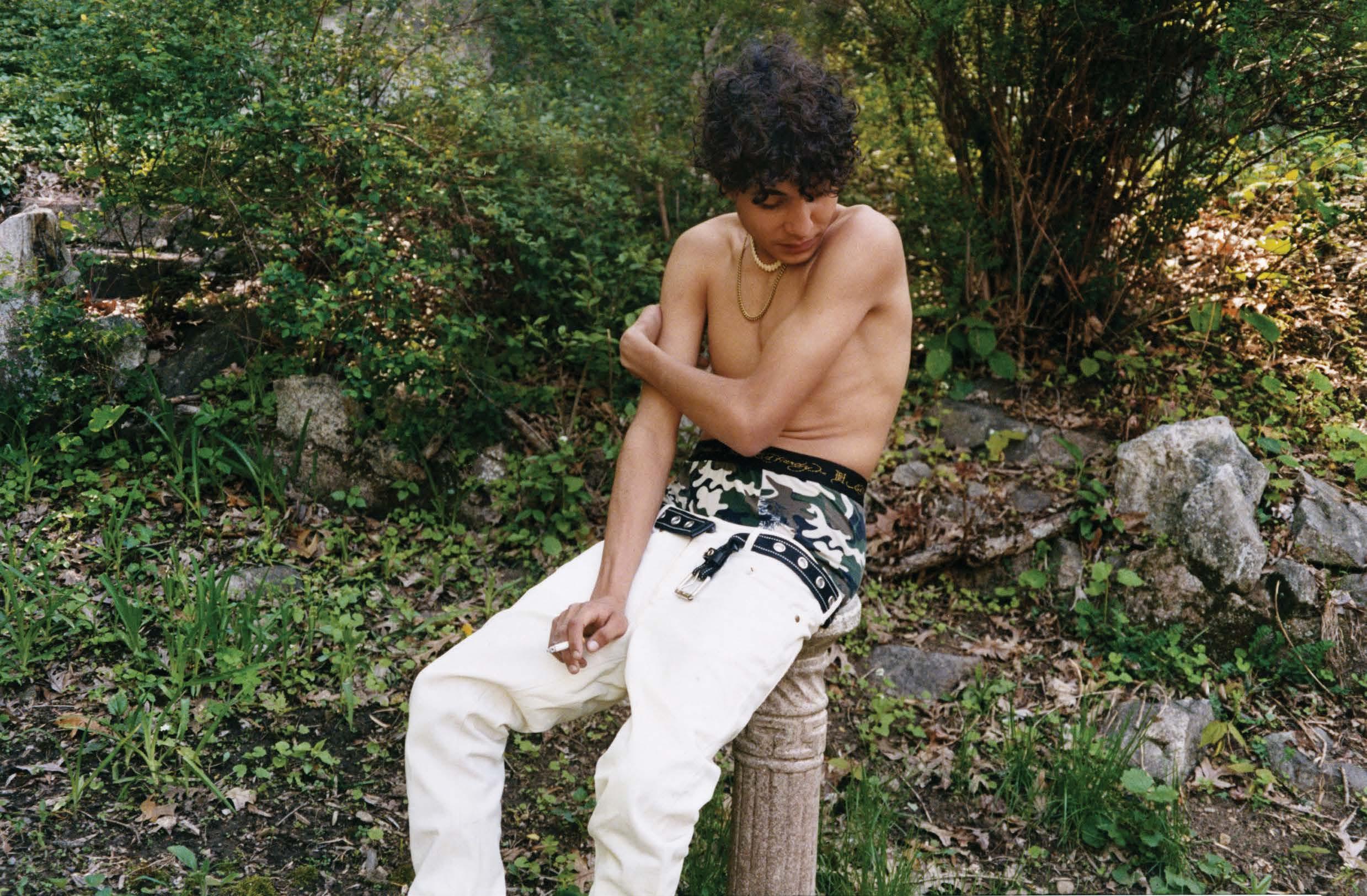

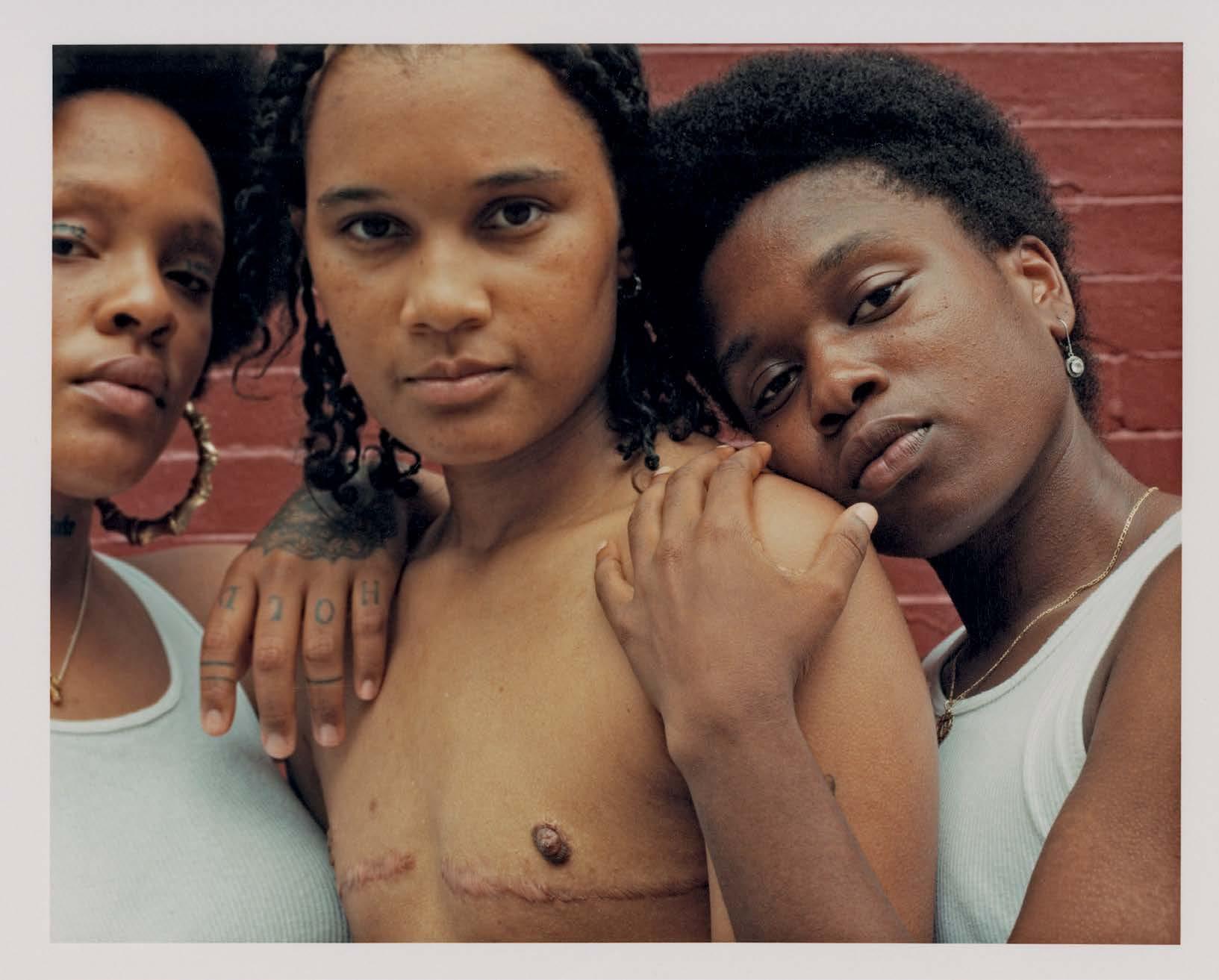

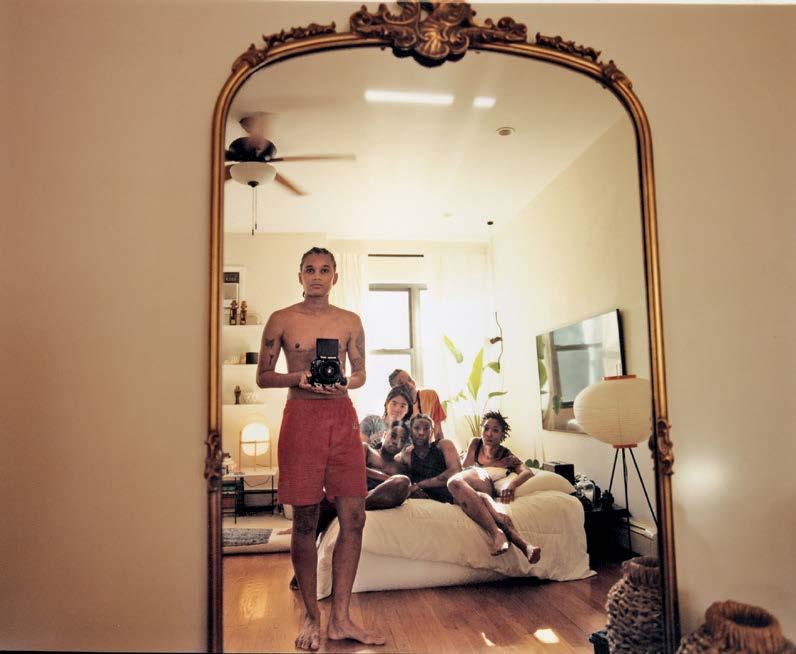

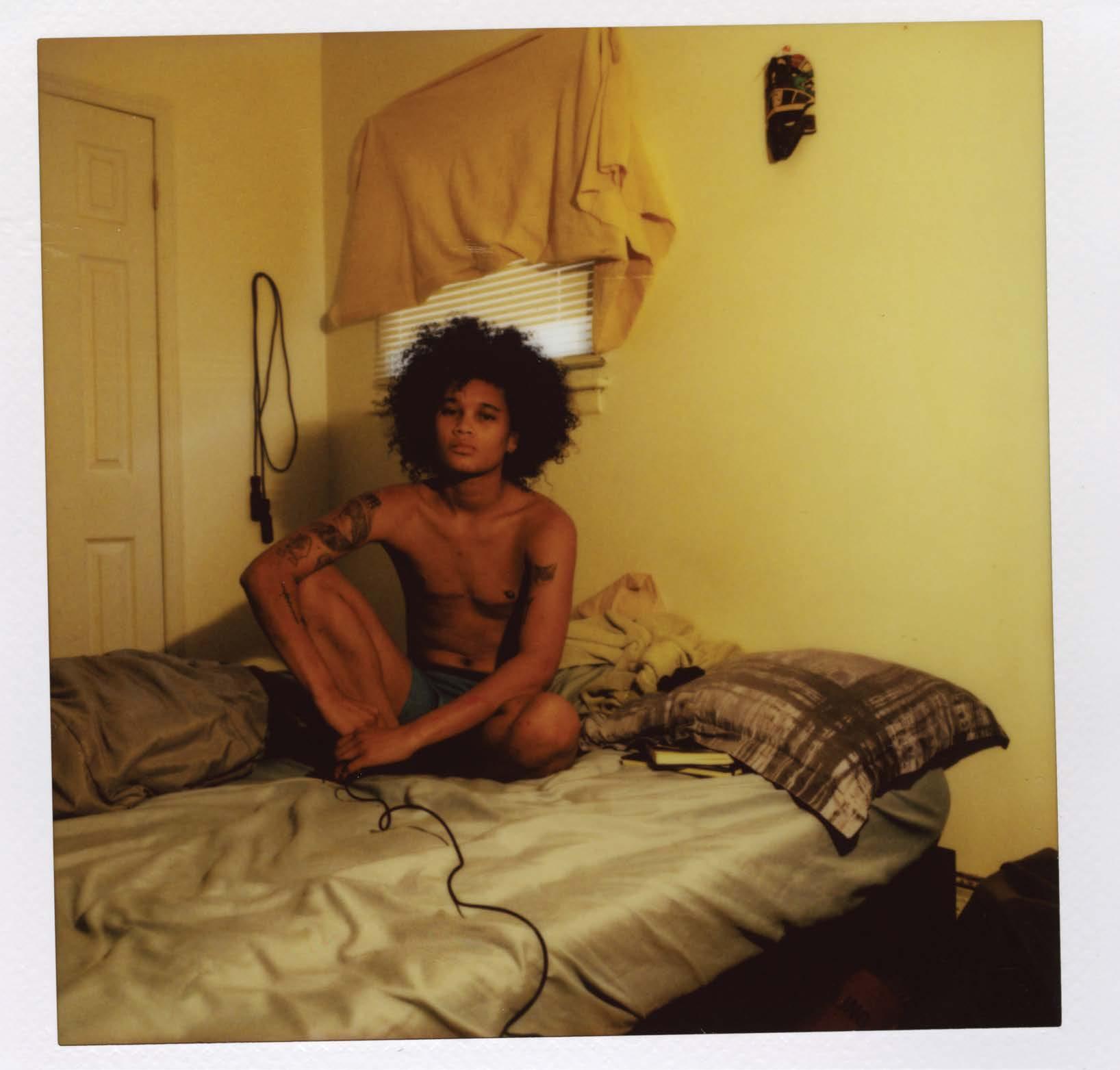

ZORA SICHER: THE ART OF INTIMACY

The photographer shares a collection of unpublished mementos—an homage to her admiration for the naked form.

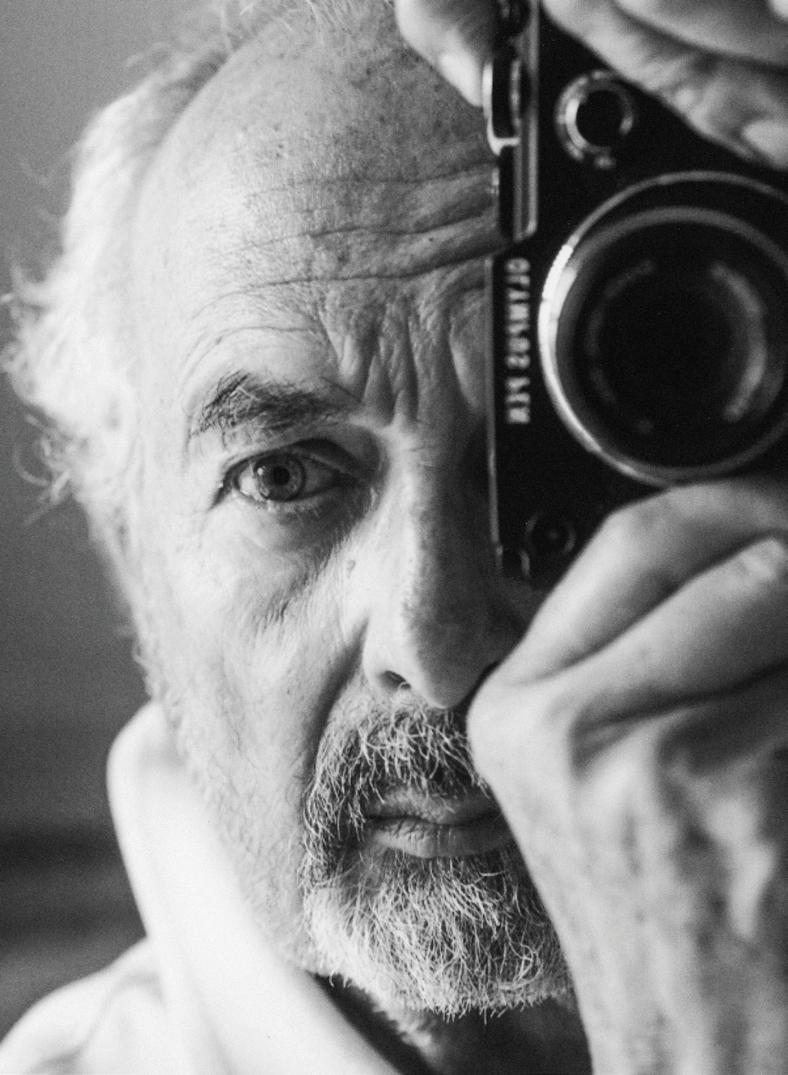

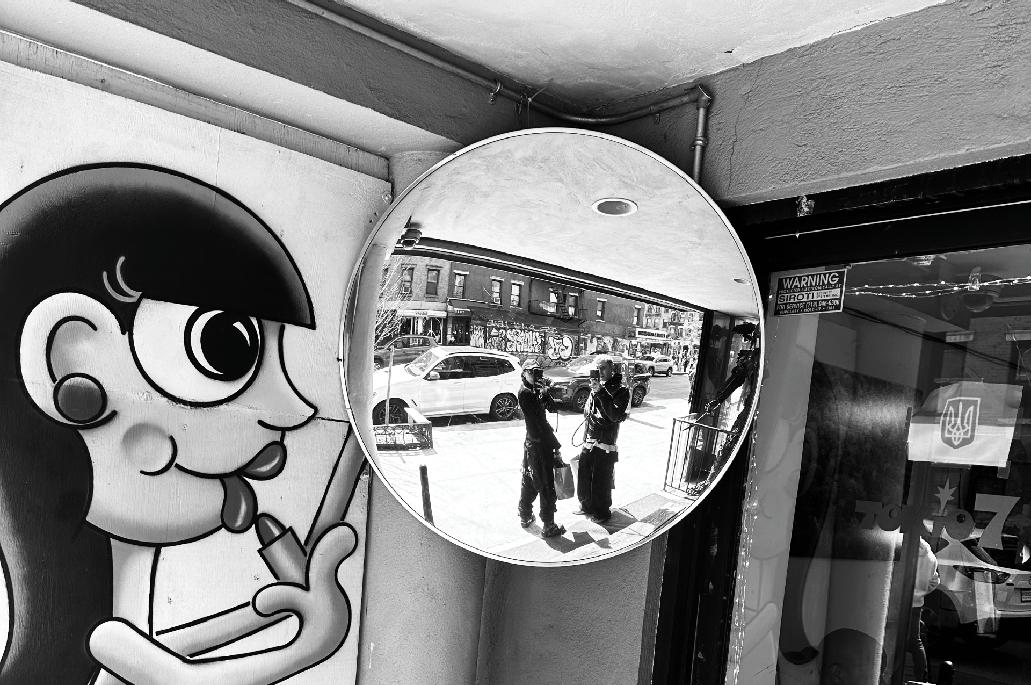

YOUNG PHOTOGRAPHERS 2024

All under the age of 35, this year’s class represents a microcosm of a vast and remarkable new generation of image makers.

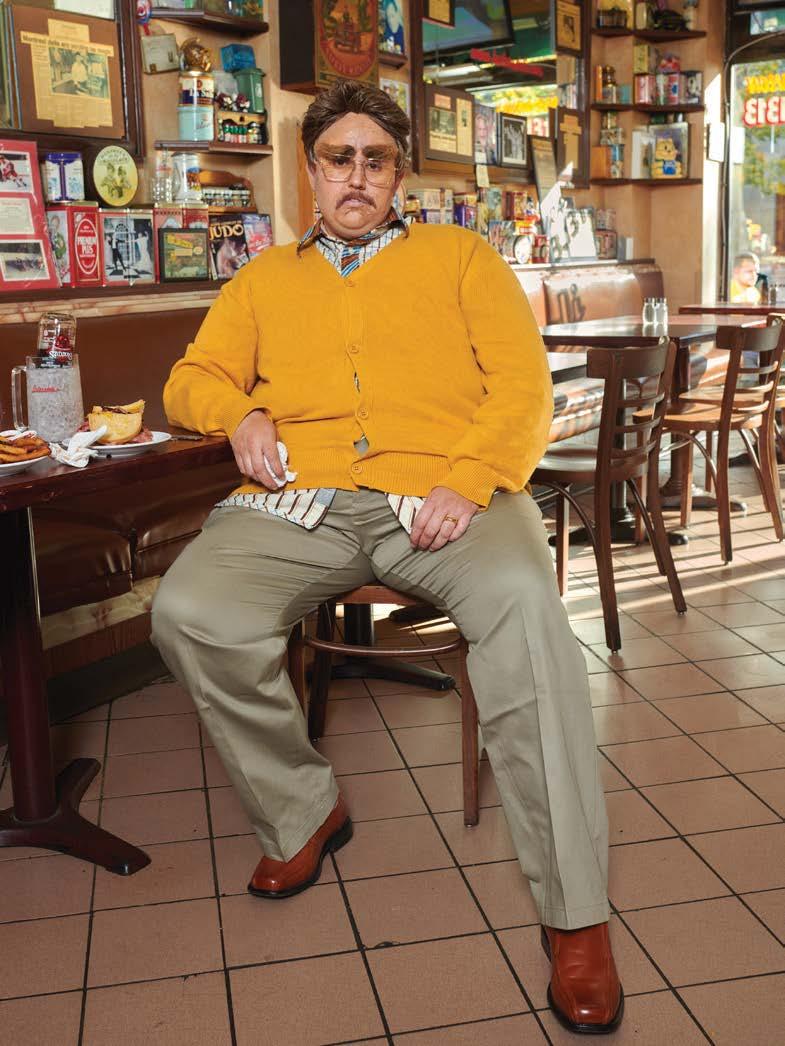

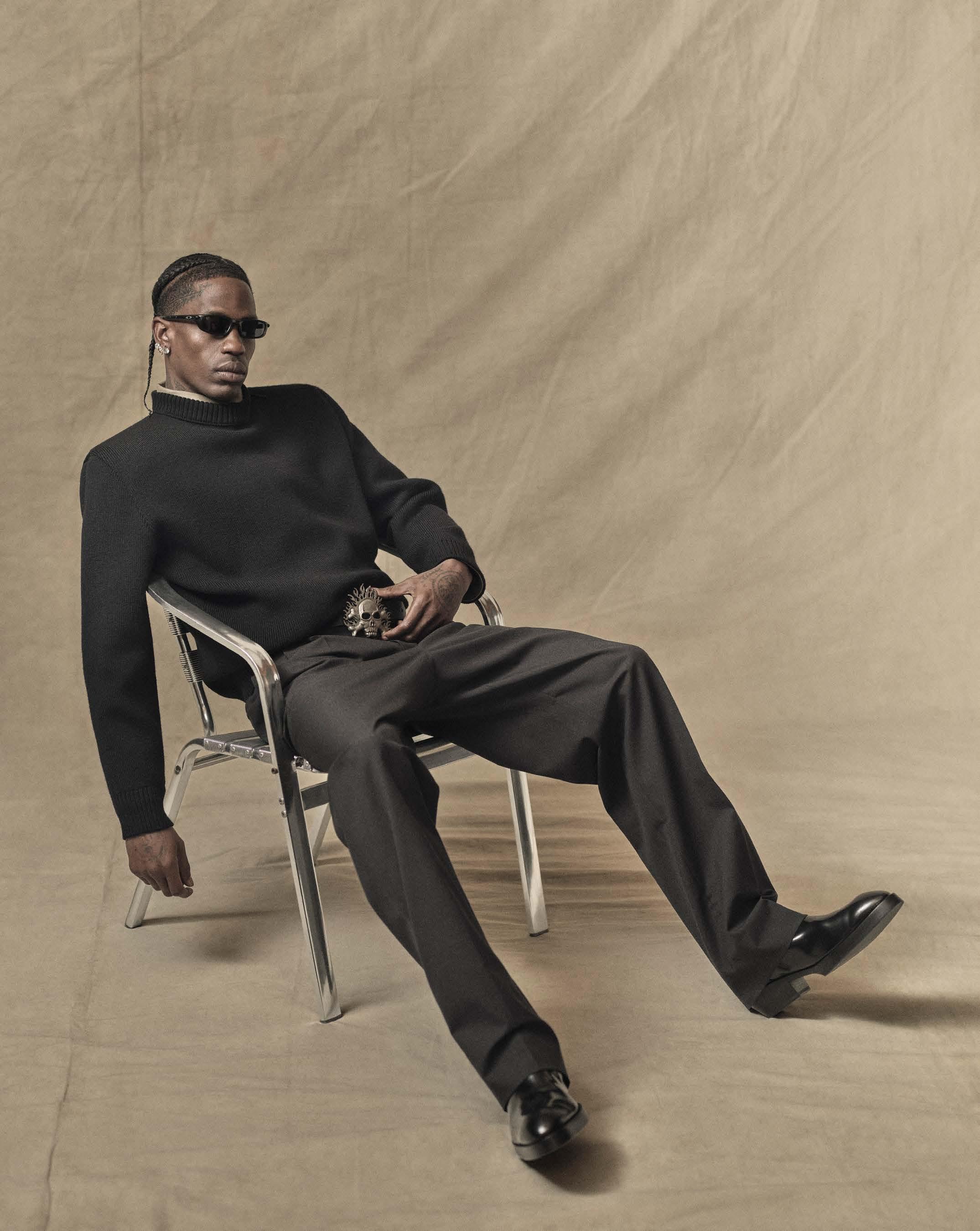

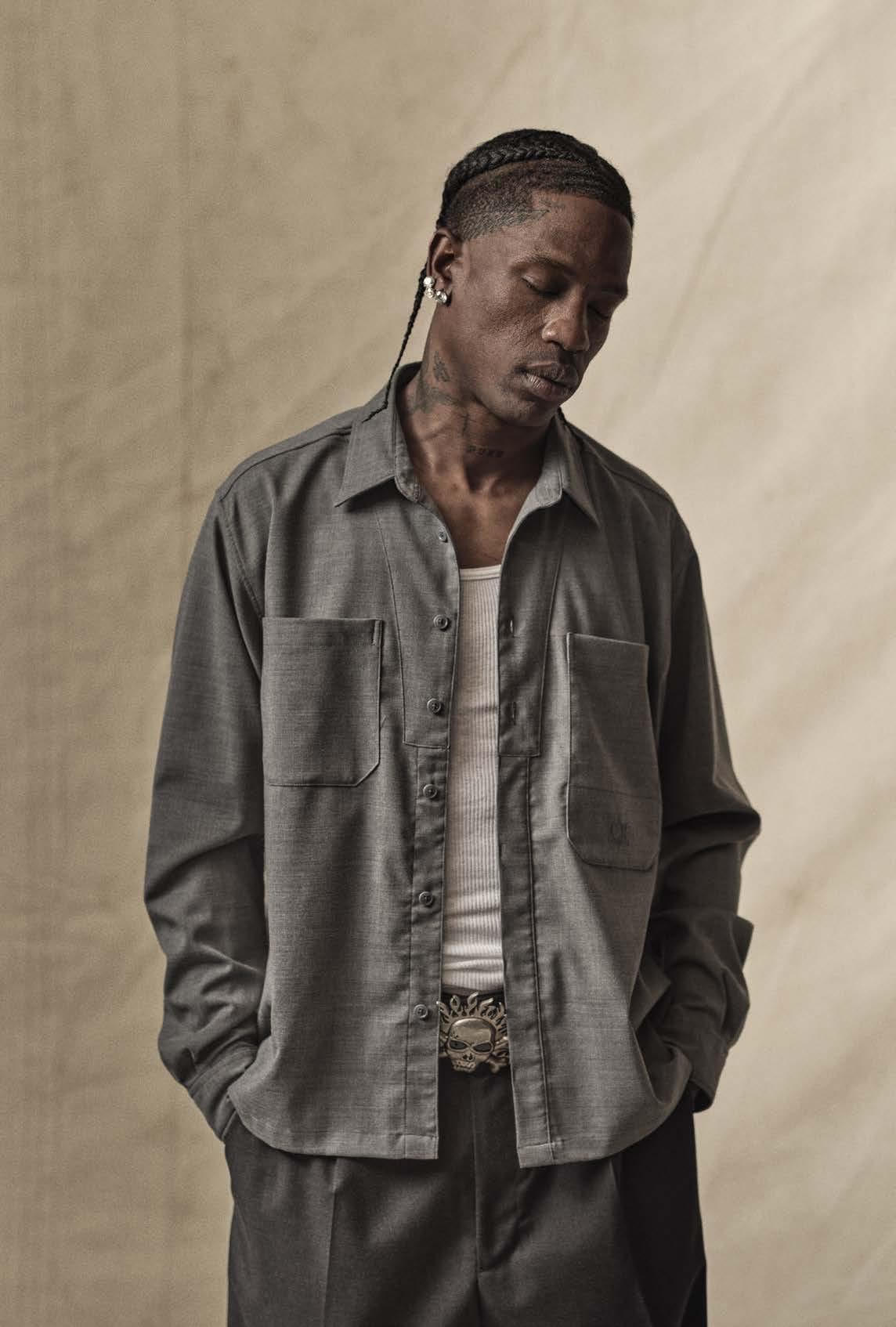

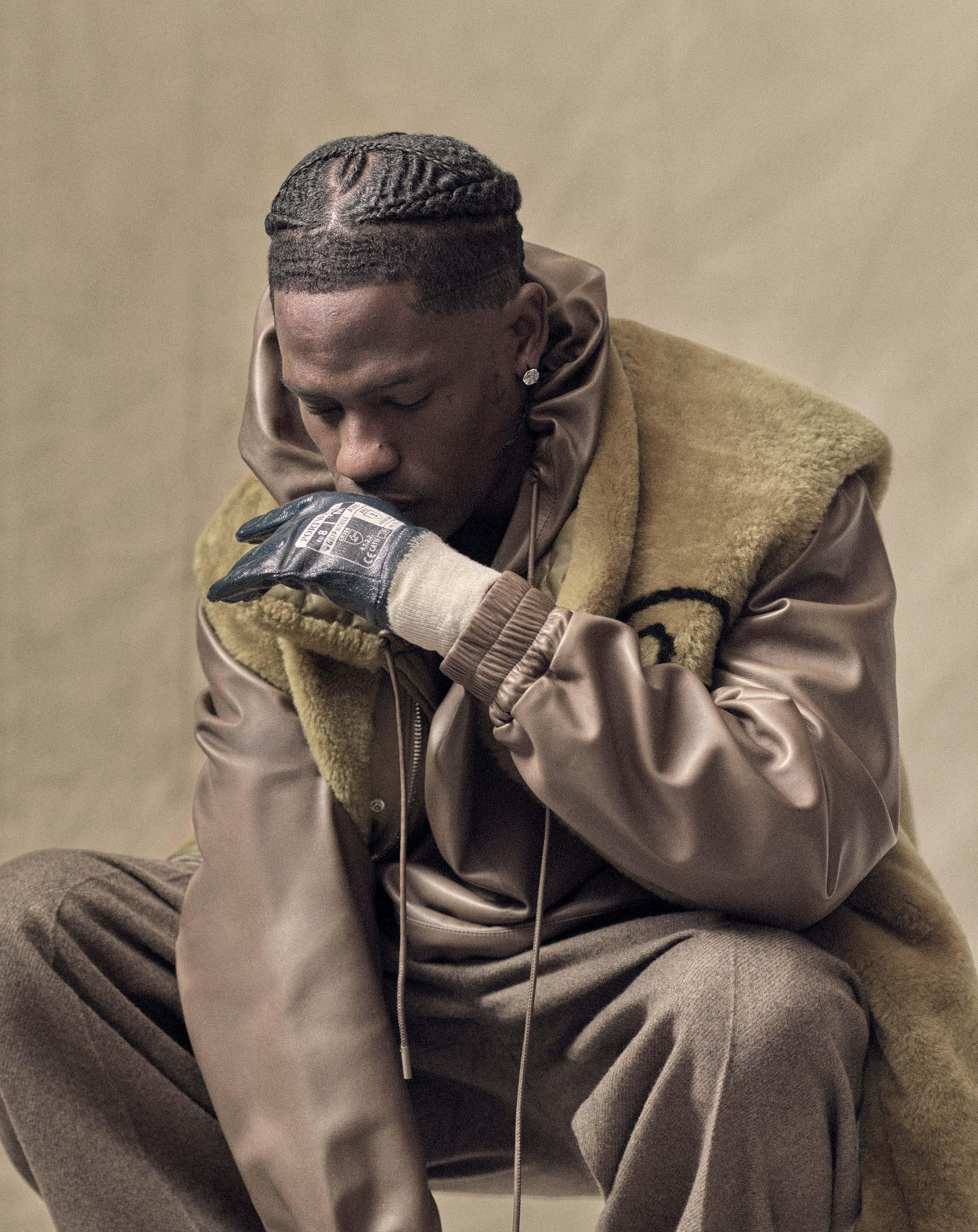

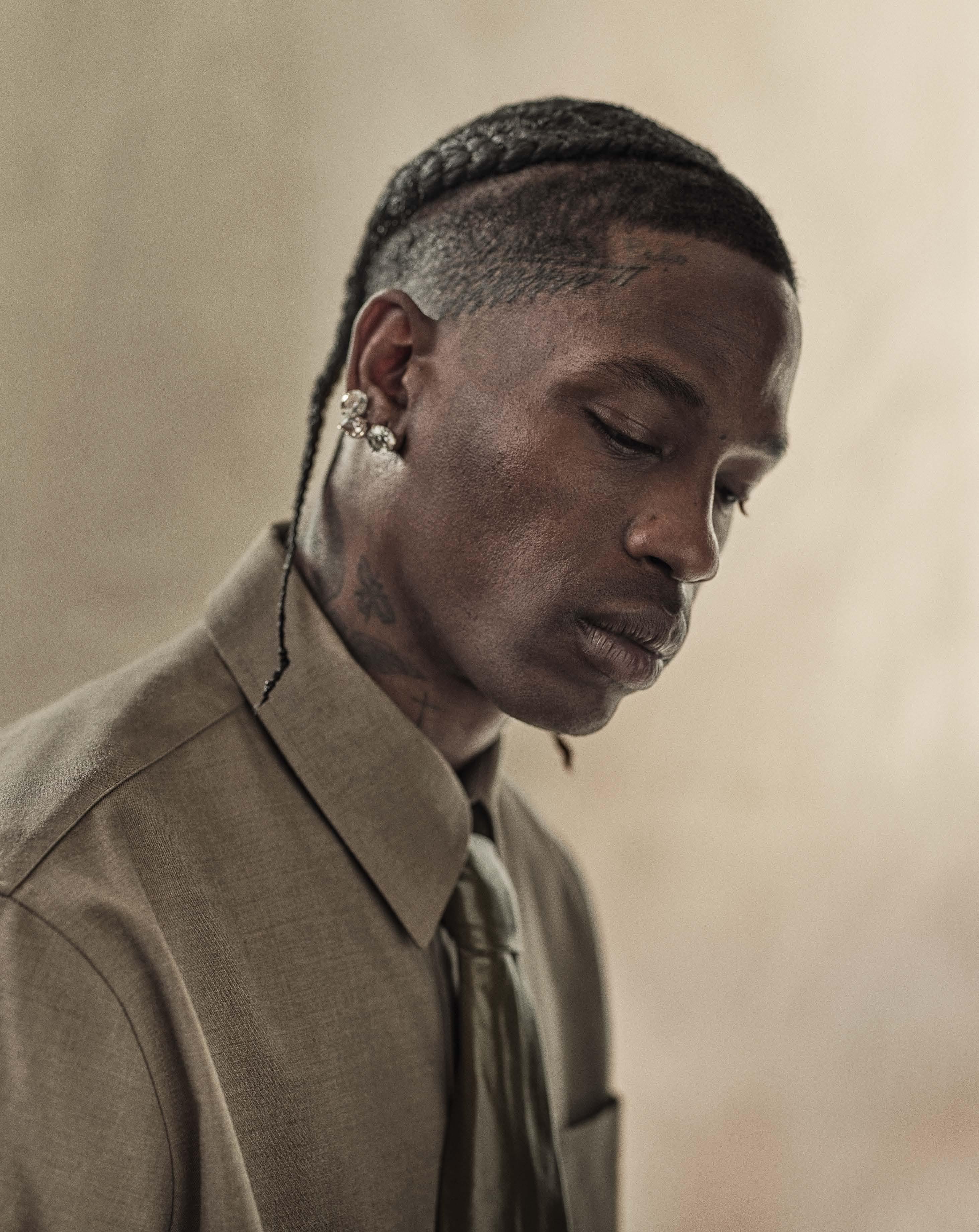

CRASH, DESTROY, AND DISMANTLE

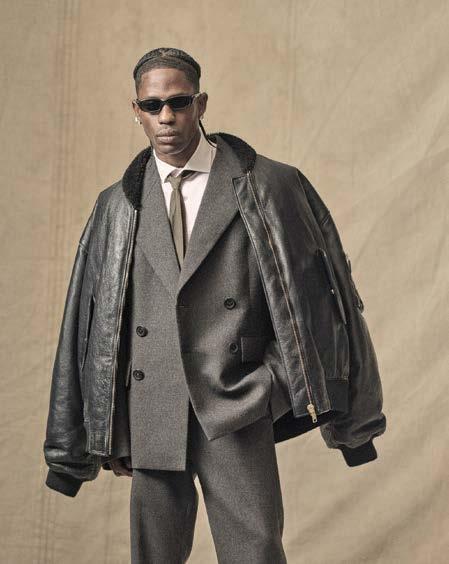

Despite their disparate fields, Travis Scott and George Condo find themselves drawn to one another. Here, they catch up after an action-packed summer.

146

MESSY GIRL, BIG TITS, BUT SMART

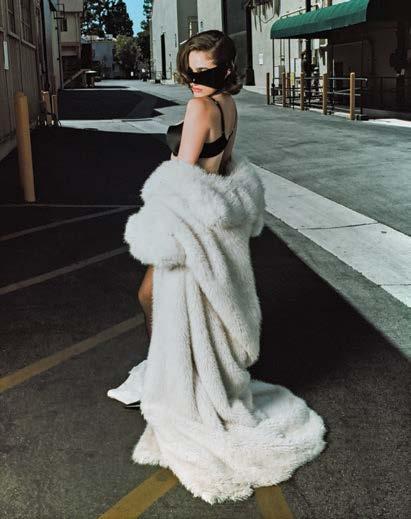

VIBES Rachel Sennott and Charli XCX sit down to compare notes on the hottest summer on record.

September/October 2024

156

GRACE CODDINGTON HAS HER BEST IDEAS IN BED From muralmaking to a return to modeling, the legendary former Vogue editor is at work on a plethora of creative endeavors. Just don’t call it retirement.

160

176

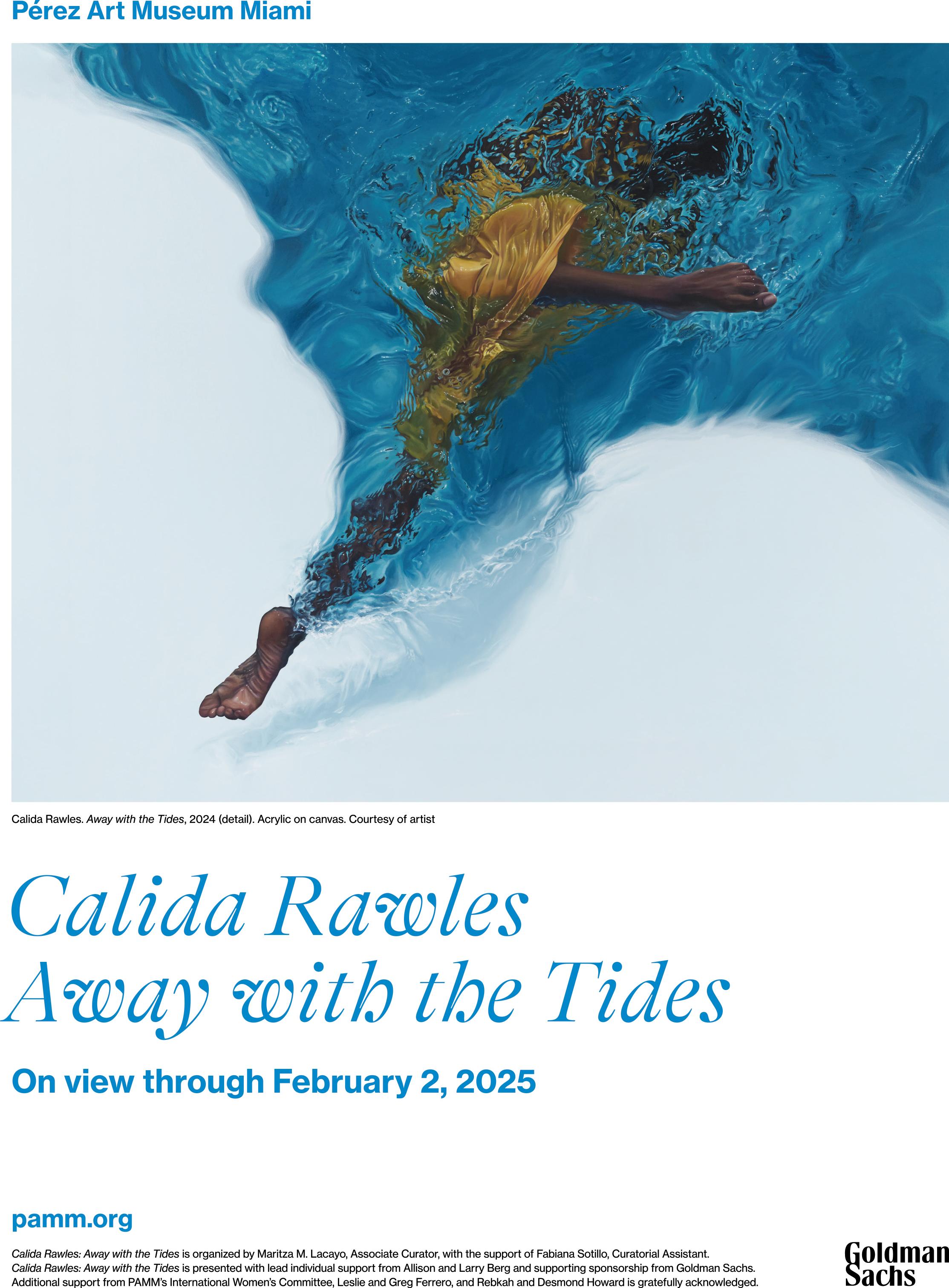

HIT WOMAN This year, a slate of leading roles has pushed Adria Arjona into the limelight. The actor is seizing her moment.

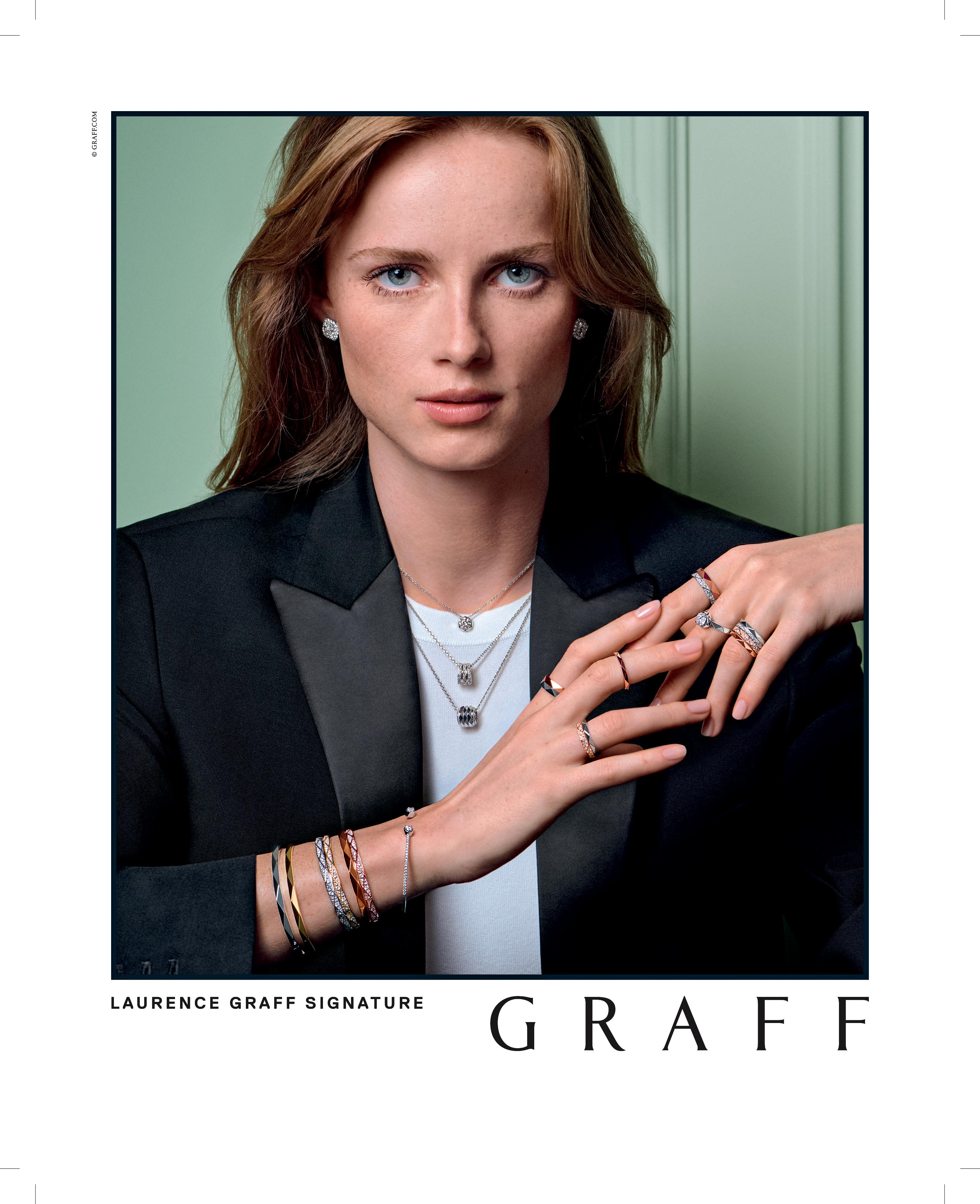

DESIGNING A LEGACY Lauded for timeless designs and flawless refinement, Graff’s precious heirlooms embody the spirit of the wearer—and the brand’s founding family—all at once.

170 TINA BARNEY LOOKS INWARD A new exhibition at Paris’s Jeu de Paume pays tribute to the photographer’s interrogations of kinship, wealth, and tradition.

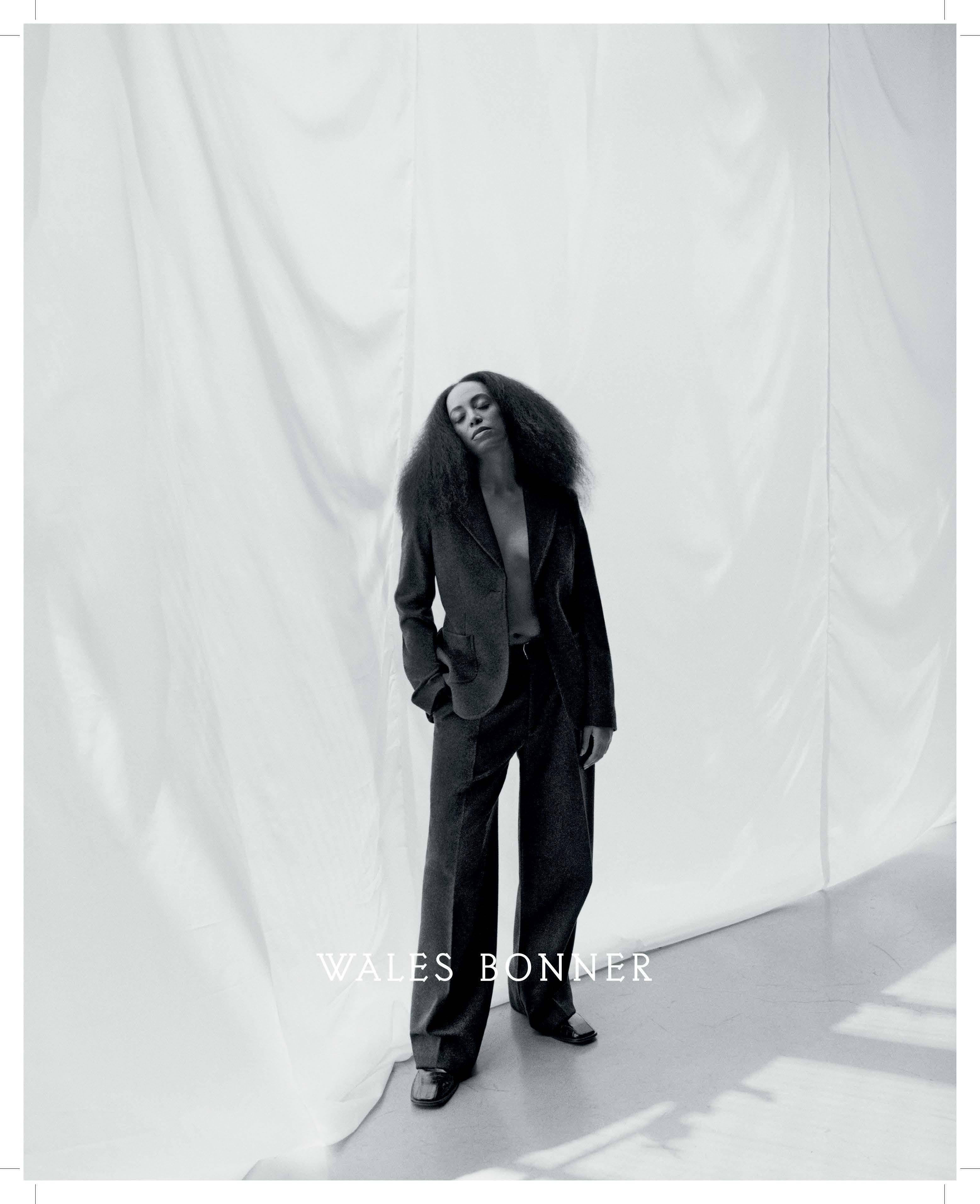

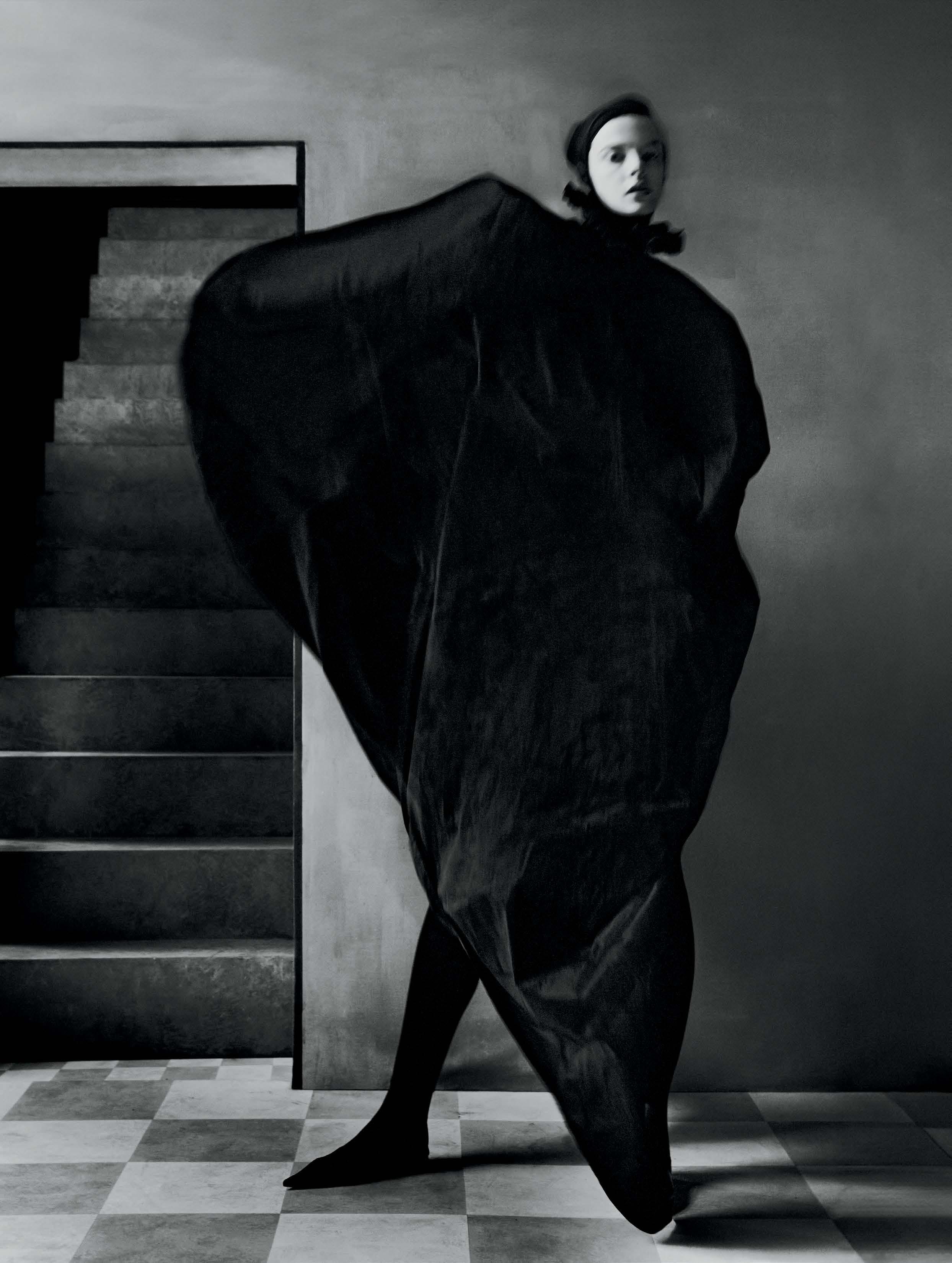

BODY WORK In the pared-back world presented by photographer Quil Lemons, each piece in Louis Vuitton’s Fall/Winter 2024 collection seems to come alive.

184 FOR THESE ARTISTS, CLOTHING IS THE MEDIUM AND THE MESSAGE

194

A rising generation of artists is turning to clothing to engage audiences beyond the white cube.

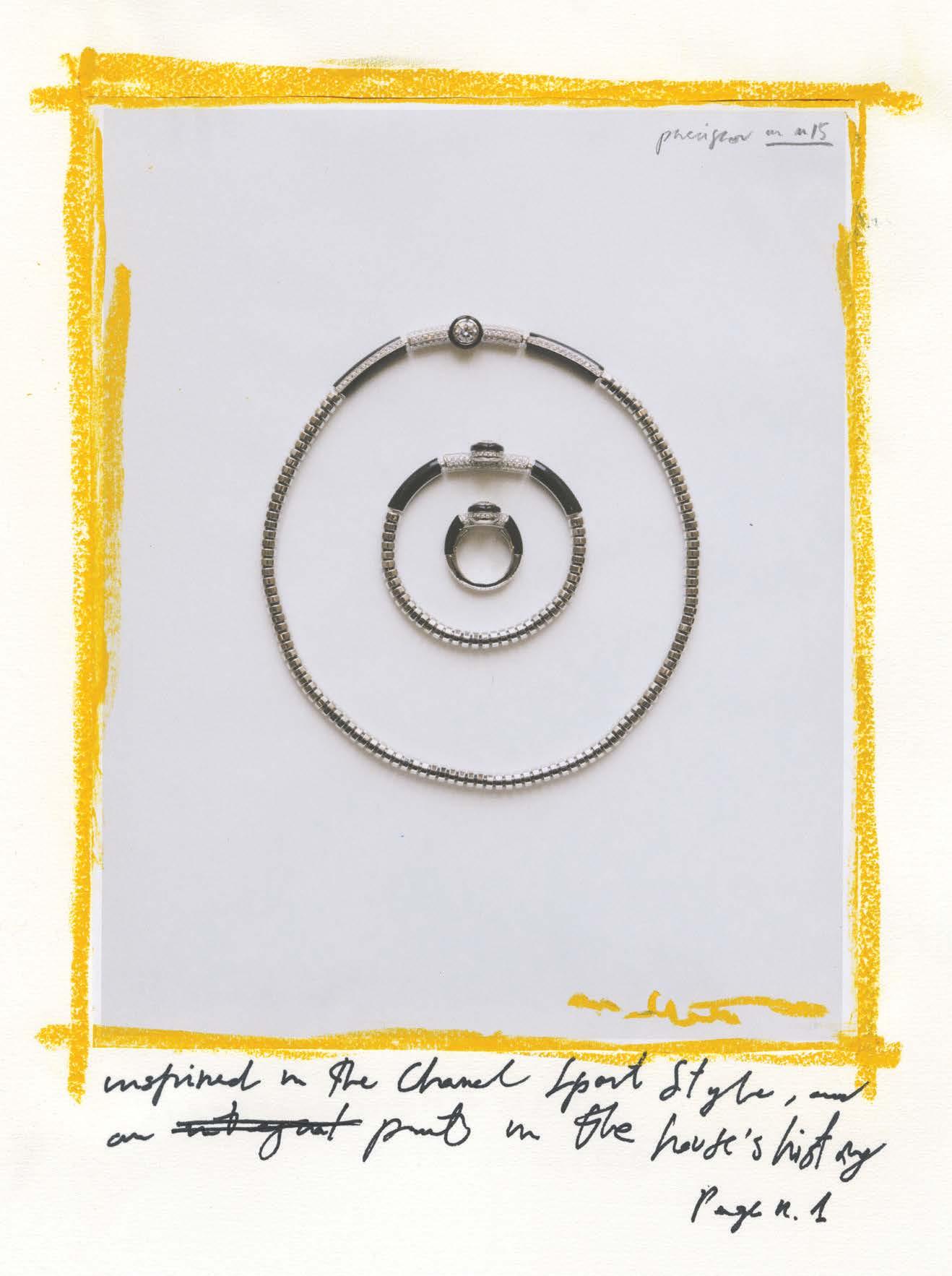

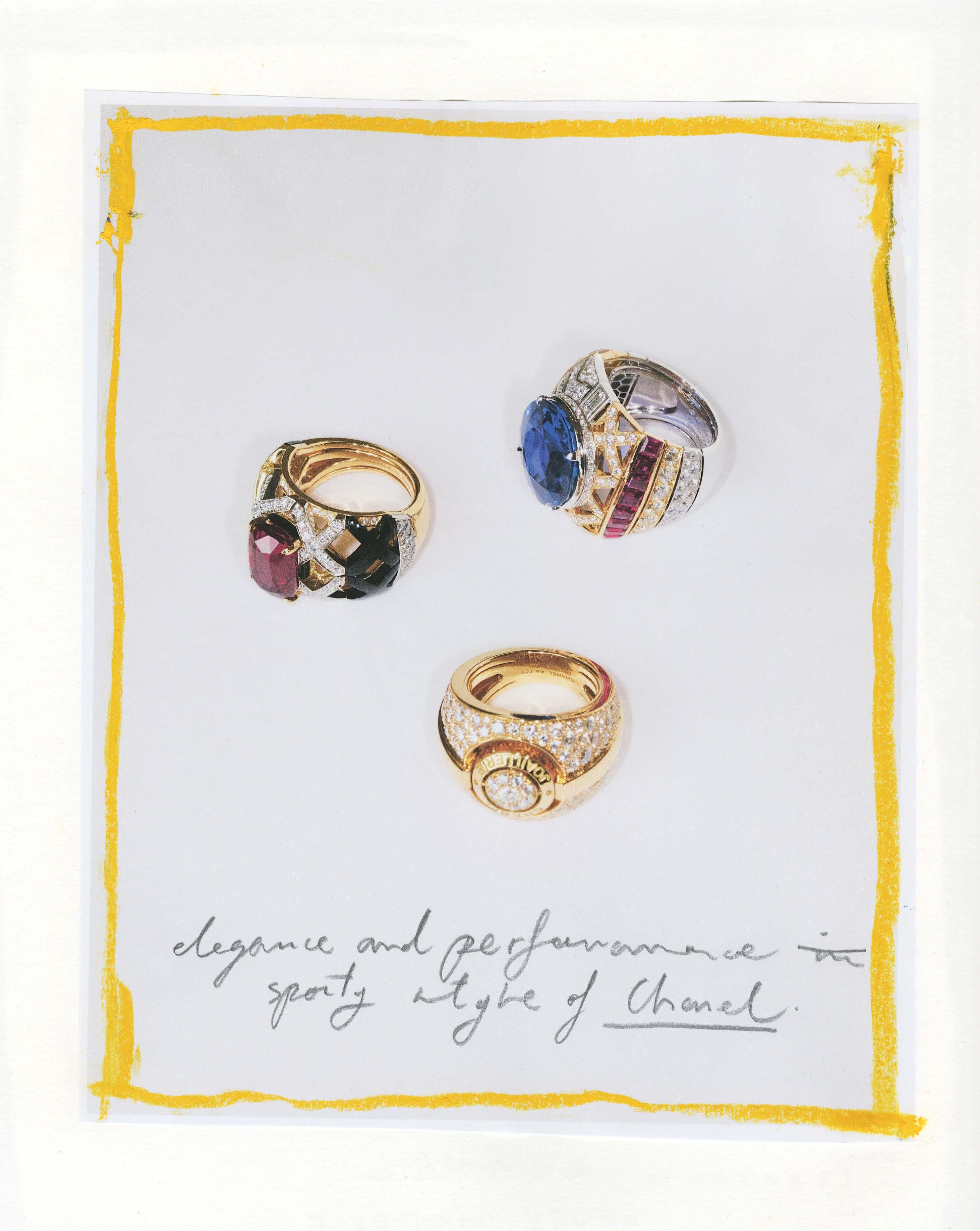

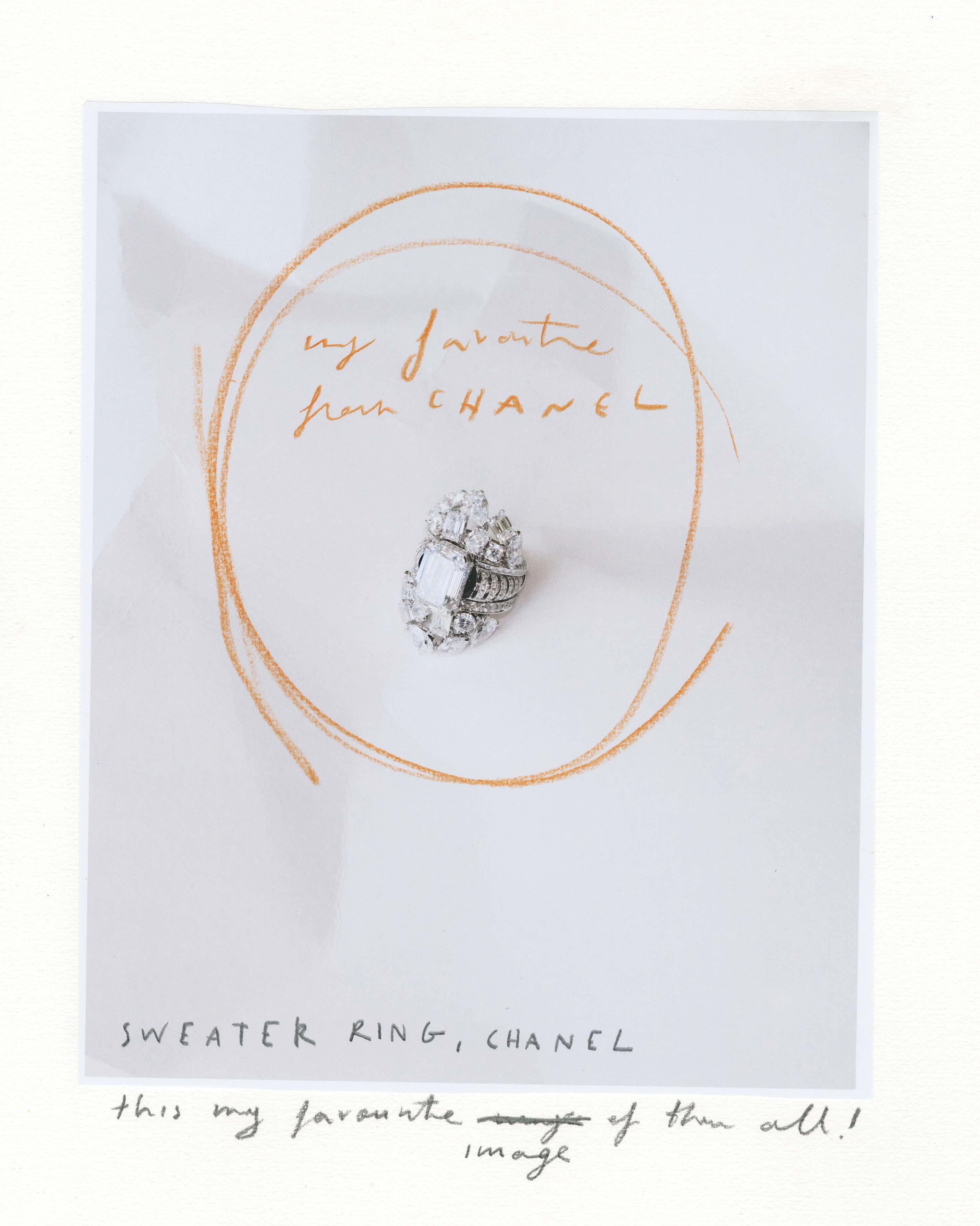

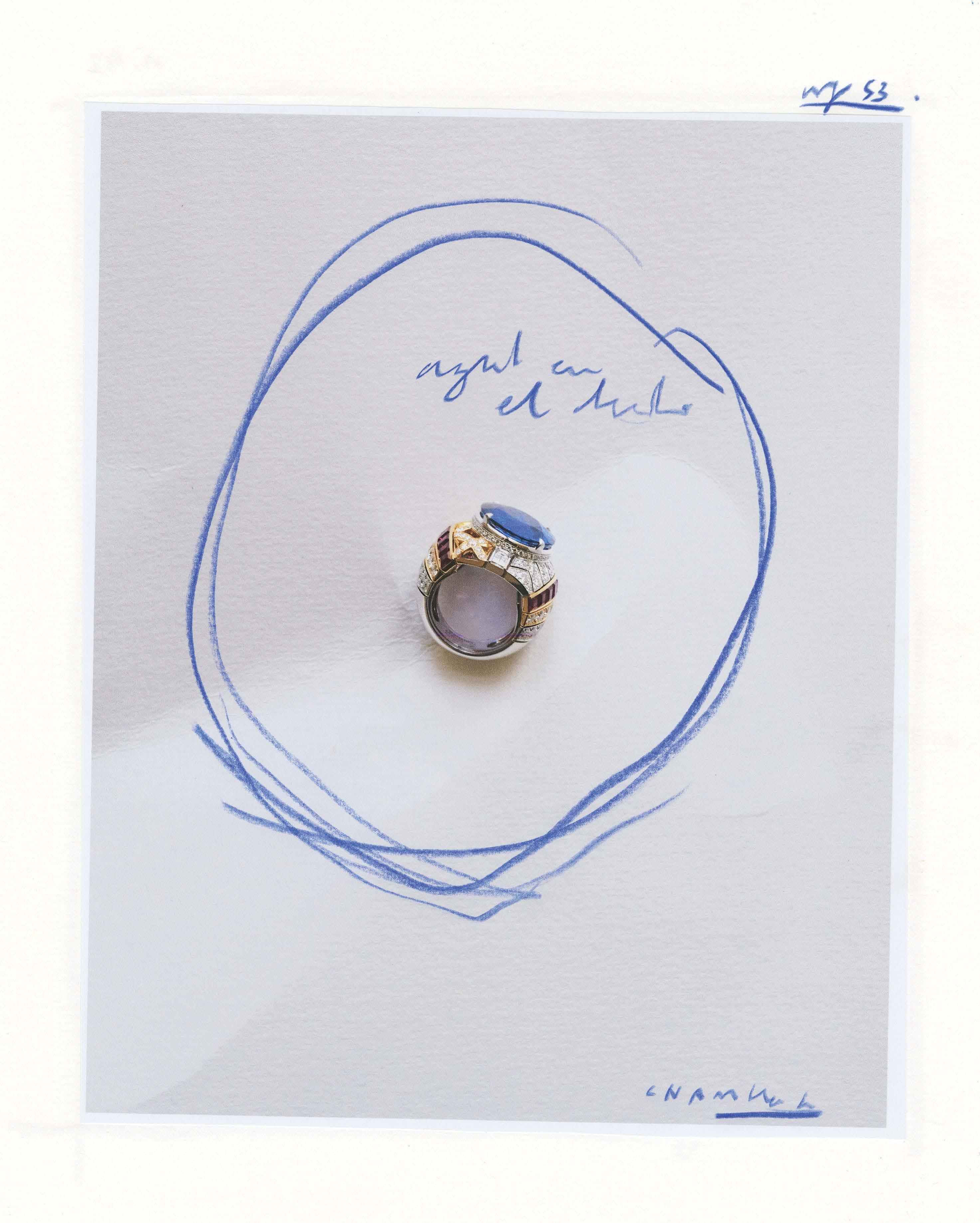

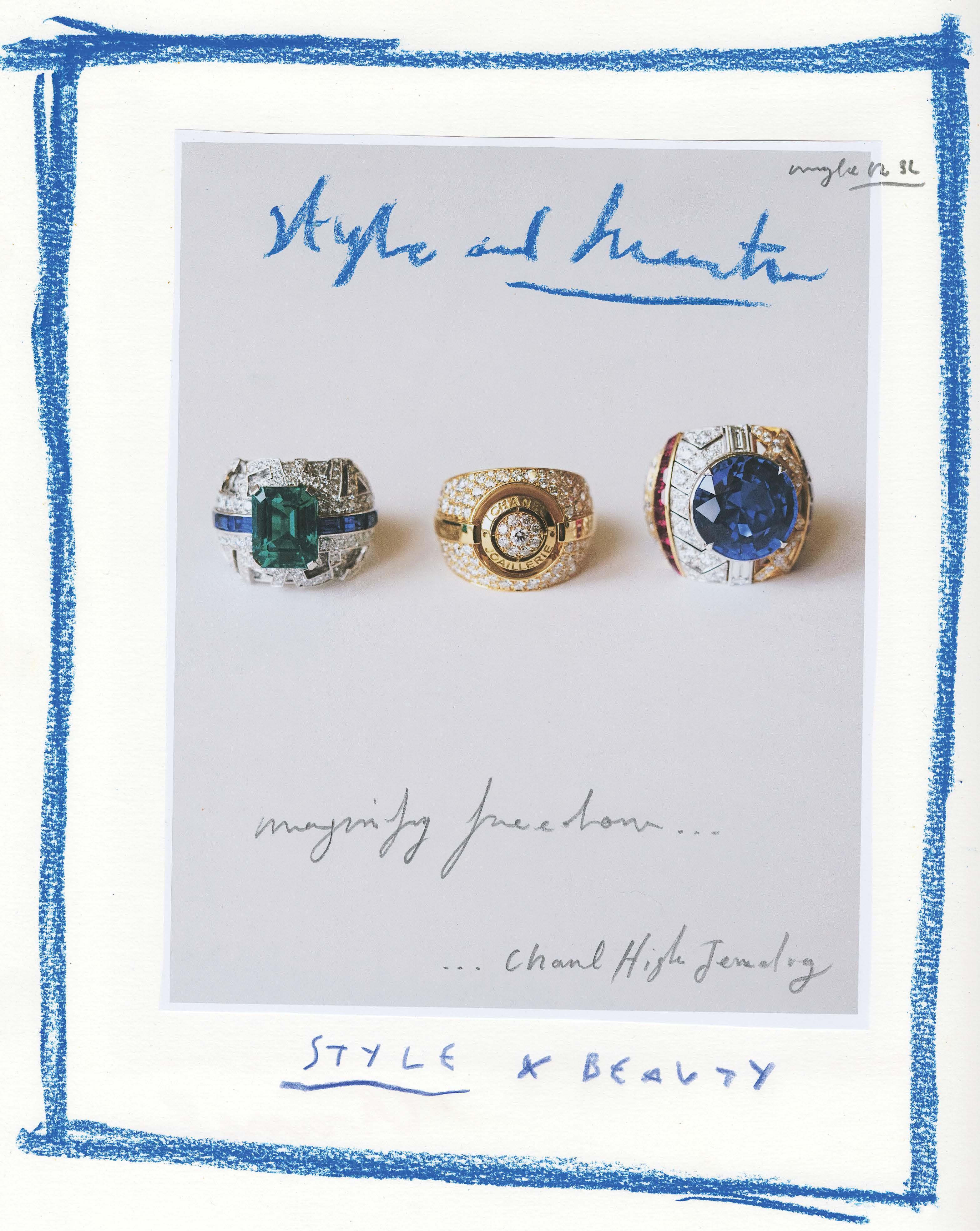

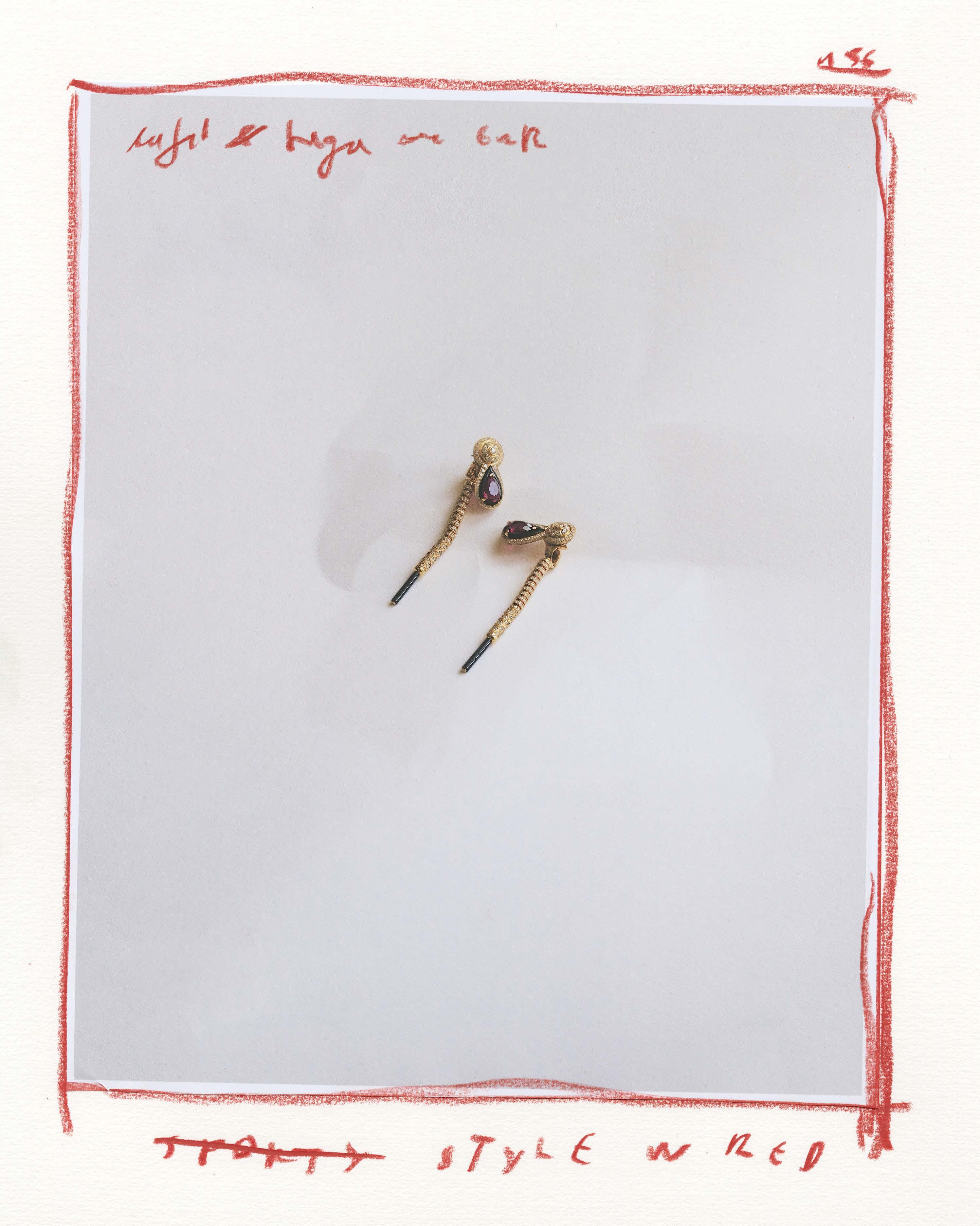

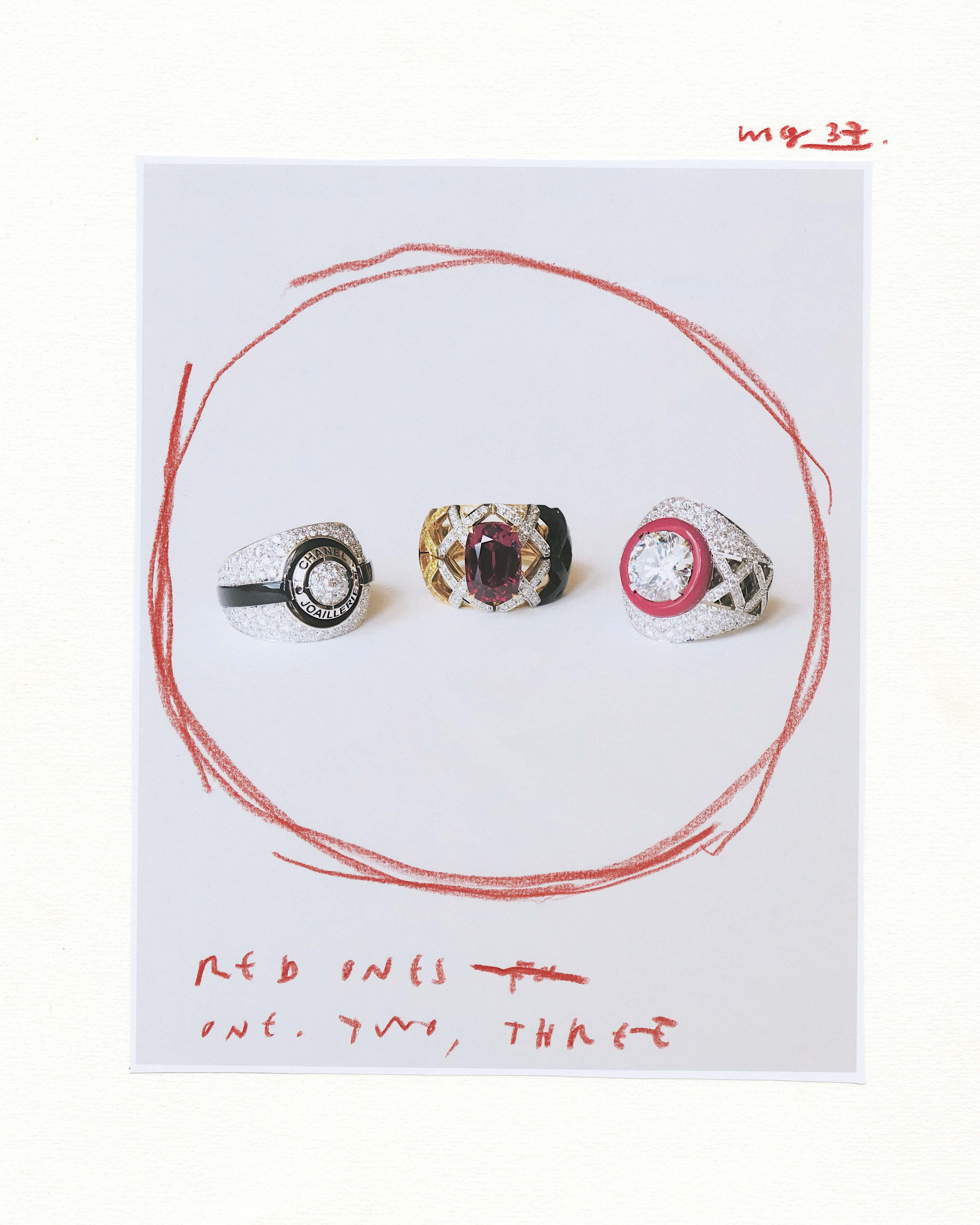

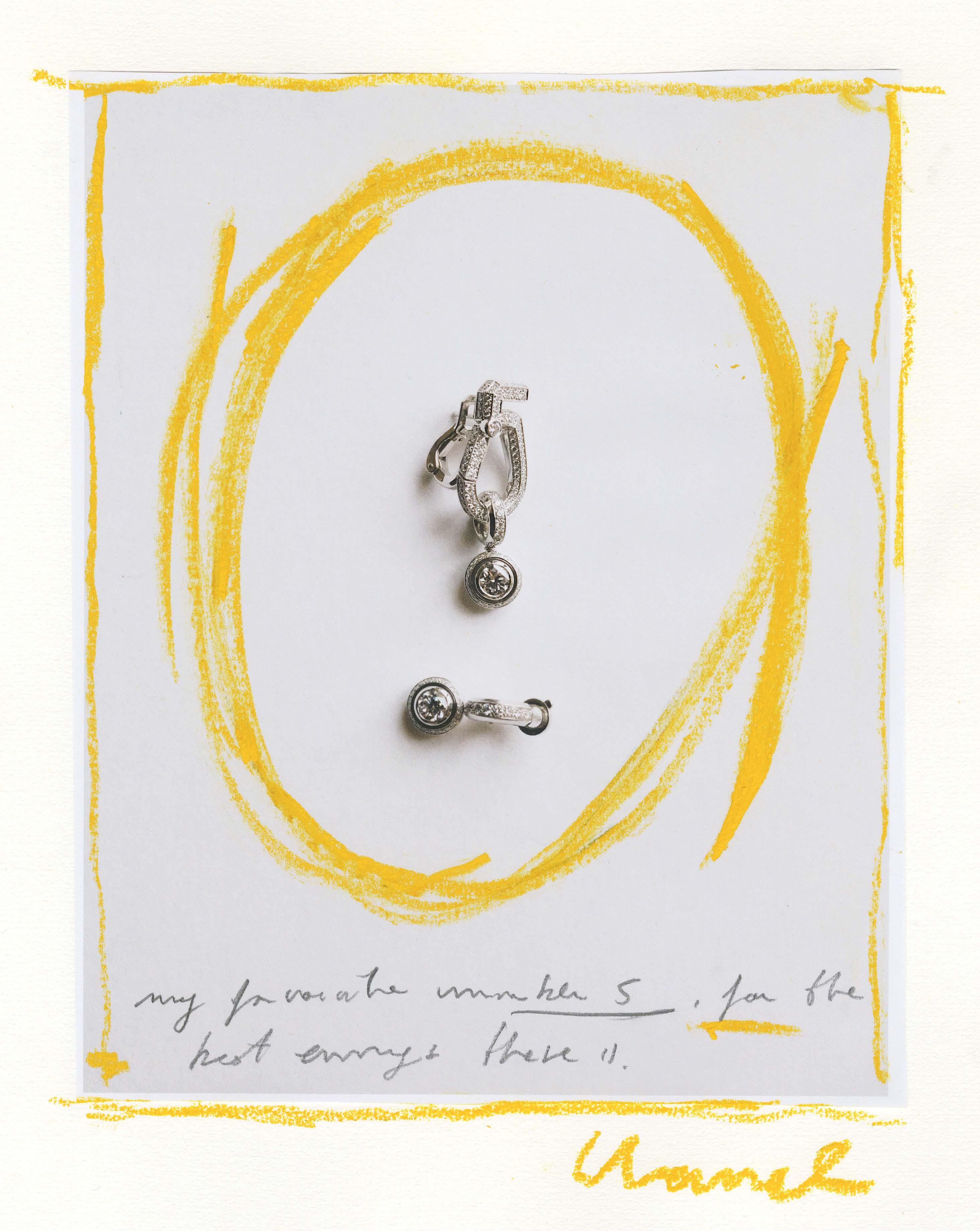

The brand’s Haute Joaillerie Sport collection evokes the ecstasy of movement—echoing delicate mementos of matches won or divisions clinched.

DISPATCH FROM ELSEWHERE

In a sartorial landscape largely preoccupied with meeting the moment, the painstaking detail and elaborate design of couture conjure up an altogether different world.

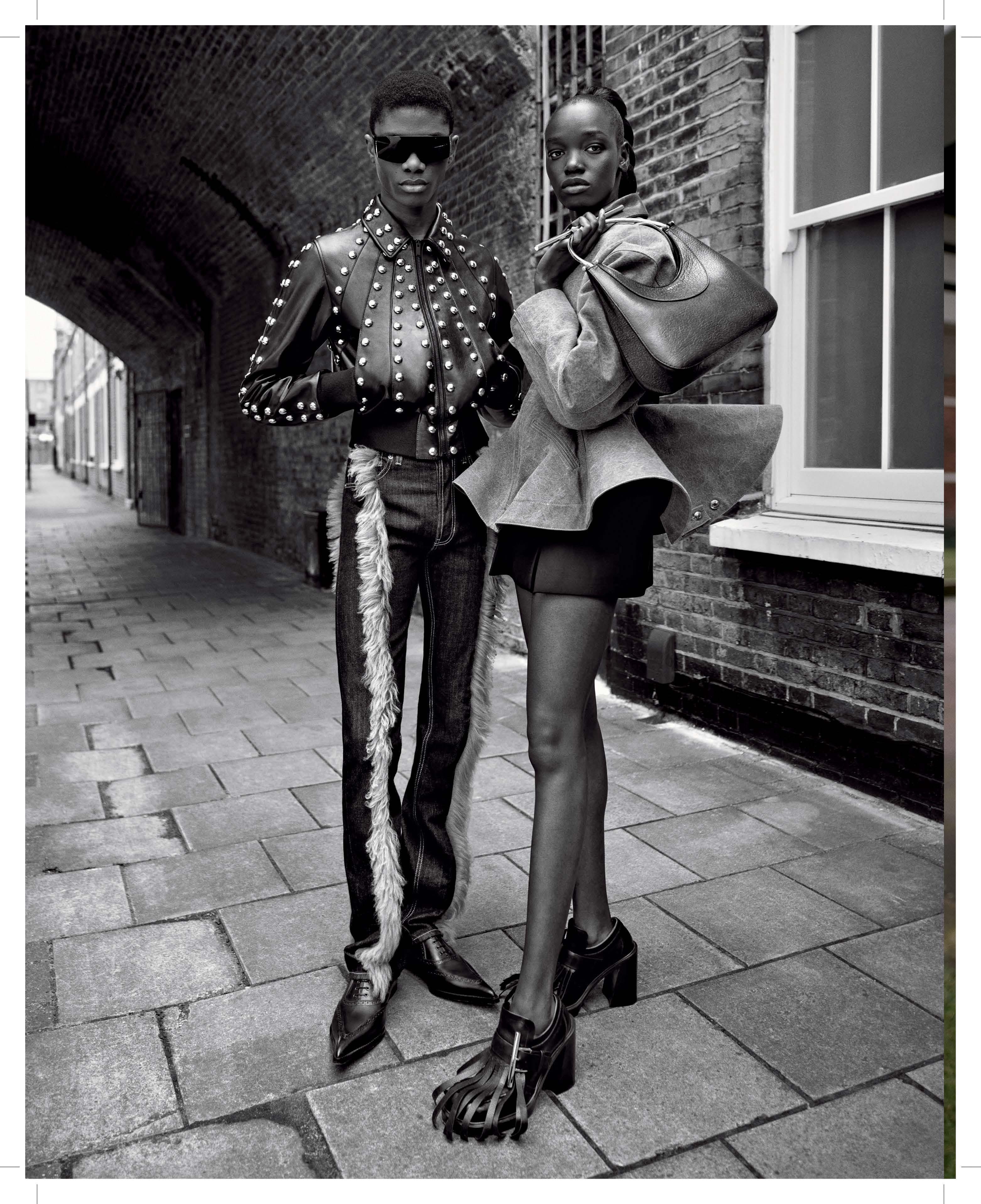

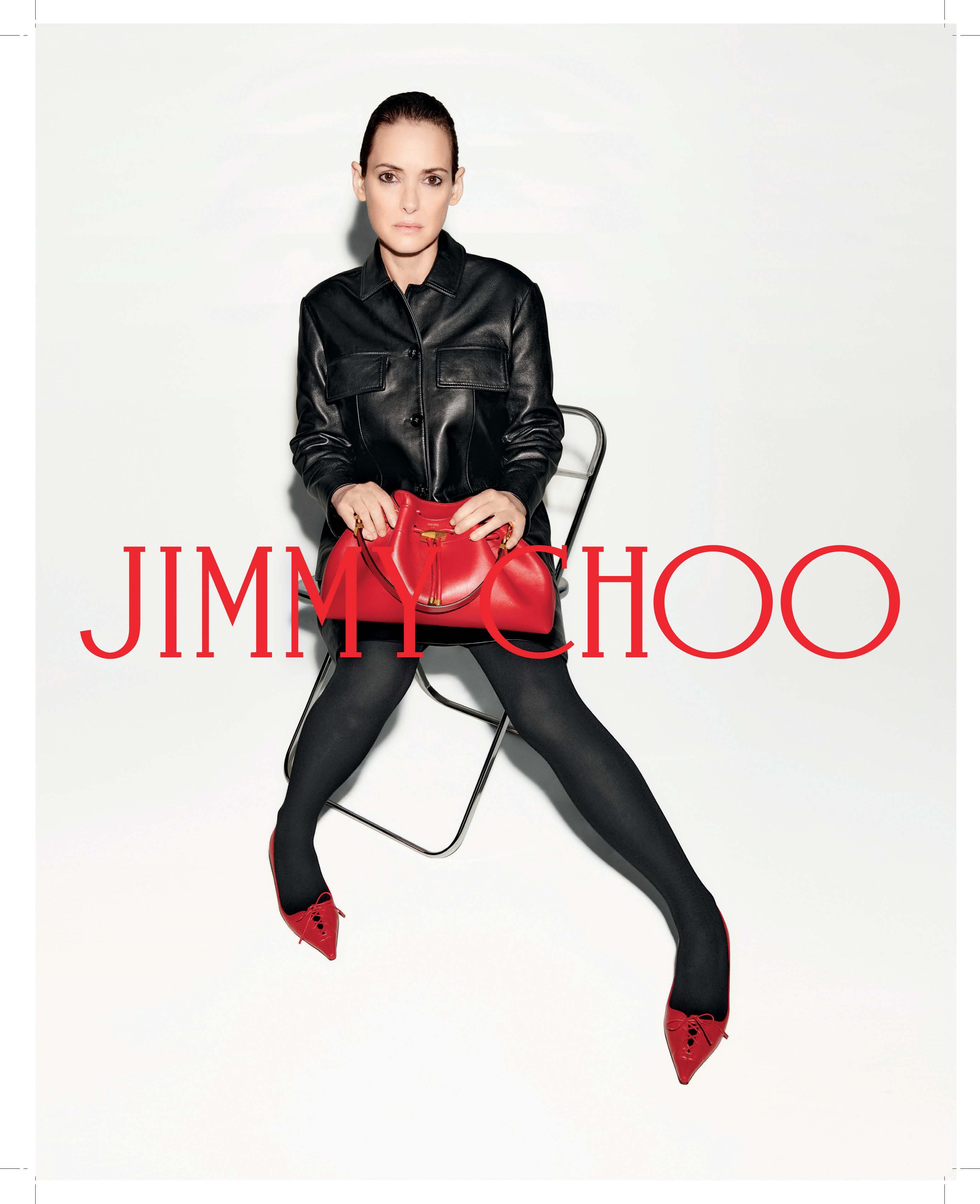

POSTCARD FROM THE ’90S

Photographer Drew Jarrett conjures the grungey-chic spirit of London in the late ’90s—Jimmy Choo’s founding moment—to celebrate the brand’s moody Autumn collection.

In the decade since he joined Louis Vuitton, the designer’s visionary cruise presentations have catapulted the brand—and the very premise of cruise—to new heights.

TRAVELING THROUGH TIME

“My Dior,” Victoire de Castellane’s latest joaillerie collection, is the designer’s tribute to the Dior woman—now and forever.

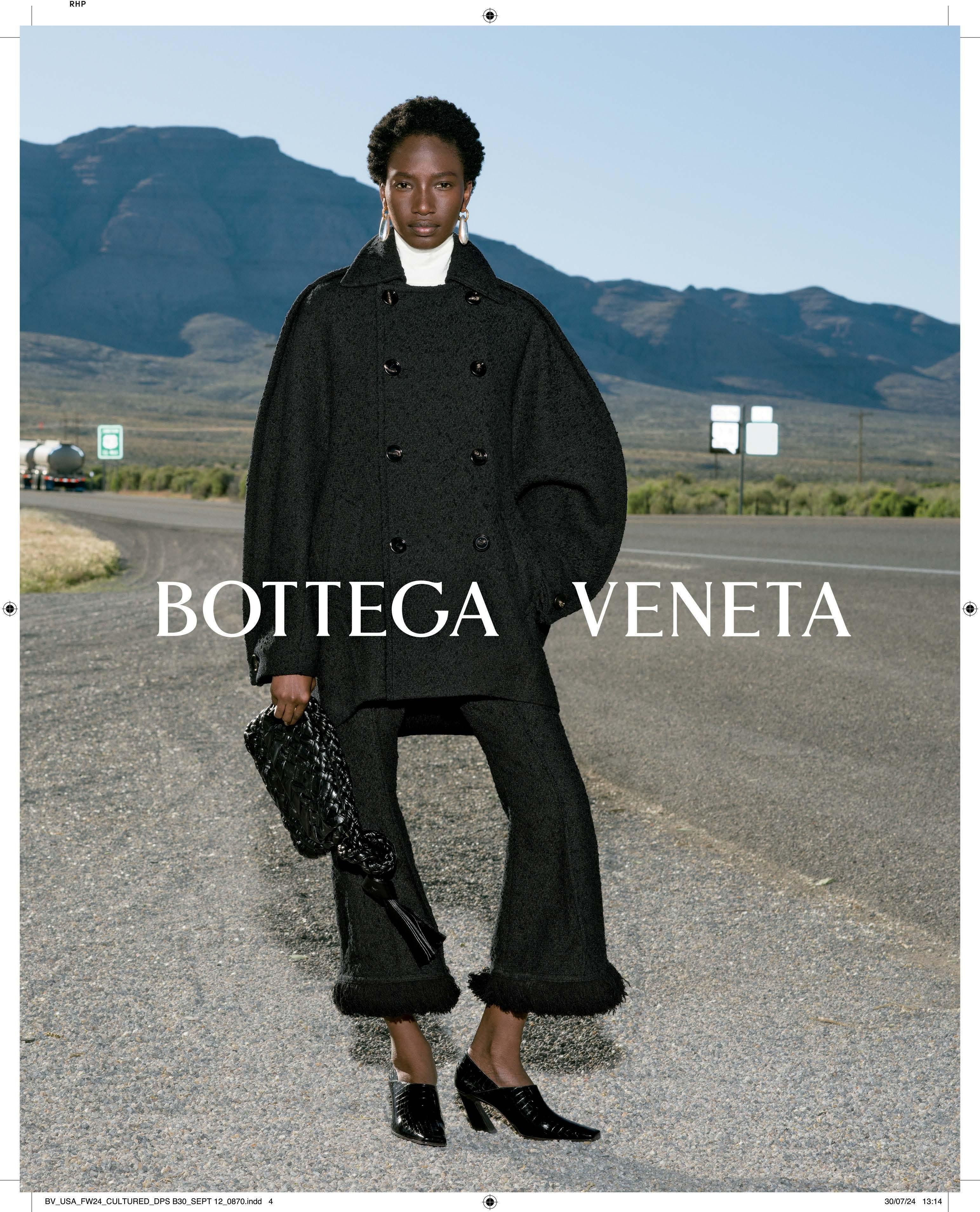

CULTURED’s September fashion issue is dedicated to provocateurs and all that fuels them. Young or old—actor, designer, musician, or artist—the people highlighted in these pages are united by their irreverence and unwavering vision.

Our moment is a complex one, so the work emerging from it should challenge expectations. Take Rachel Sennott—one of the issue’s cover stars, shot in a Hollywood back-lot on a 100-degree day in August—who has managed, in just a few years, to put forth a cinematic oeuvre that has encapsulated our anxious zeitgeist with comedic precision while simultaneously redefining the coming-of-age drama. “I feel like you’re very much at the forefront of this new kind of way to be a woman,” Sennott’s friend Charli XCX tells her in the issue’s cover story. “It’s kind of this messy girl, big tits, but smart vibes.” Travis Scott, a rap renegade of historic proportions, has left his own indelible mark on our culture through his forays into fashion and his desire to collaborate across mediums. “I try to connect with people who inspire me to push it,” he tells George Condo in this issue’s cover story. “I’m trying to always challenge myself to be better.” Others channel their drive more into introspection than collaboration: For the legendary artist Thomas Houseago, who I spent the morning with in Malibu and whose forthcoming New York show charts what he describes as a recent “dark night of the soul,” creativity is the result of a deep, merciless dive inward. “The minotaur is the perfect metaphor for trauma, right?” he says of one of the show’s central symbols. “Born out of perversion. Half man, half beast. Stuck in a maze it can’t get out of.” And then there’s the inimitable Grace Coddington—83 years old with a slate of new creative forays on the horizon—who has no intention of acting her age. She invited us into her home out East while her old friend, the legendary Arthur Elgort, photographed her for our digital cover.

“The people highlighted in these pages are united by their irreverence and unwavering vision.”

These pages also feature an homage to the earliest kernels of creativity. Our second annual Young Photographers list features 12 formidable image-makers, put forward by some of the most notable photographers of our day. These creatives are not contained to one school or aesthetic, nor do their practices reflect their formidable nominators: Dawoud Bey, Justine Kurland, Cass Bird, Elle Pérez, Lyle Ashton Harris, Tyler Mitchell, Farah Al Qasimi, Jack Pierson, and Ethan James Green. “Think of this new group as the next ring, moving outward, in an era when photography is perhaps more prized, more omnipresent, and more distrusted than ever before,” says the writer Rebecca Bengal in the list’s

introduction. “Collectively, they have dedicated themselves to photography as an art form,” she concludes, “an integral part of their lives, as fundamental as breathing.”

In these stories and countless others in this issue, we celebrate the force of the creative spirit and the many ways it manifests. We hope you enjoy the issue.

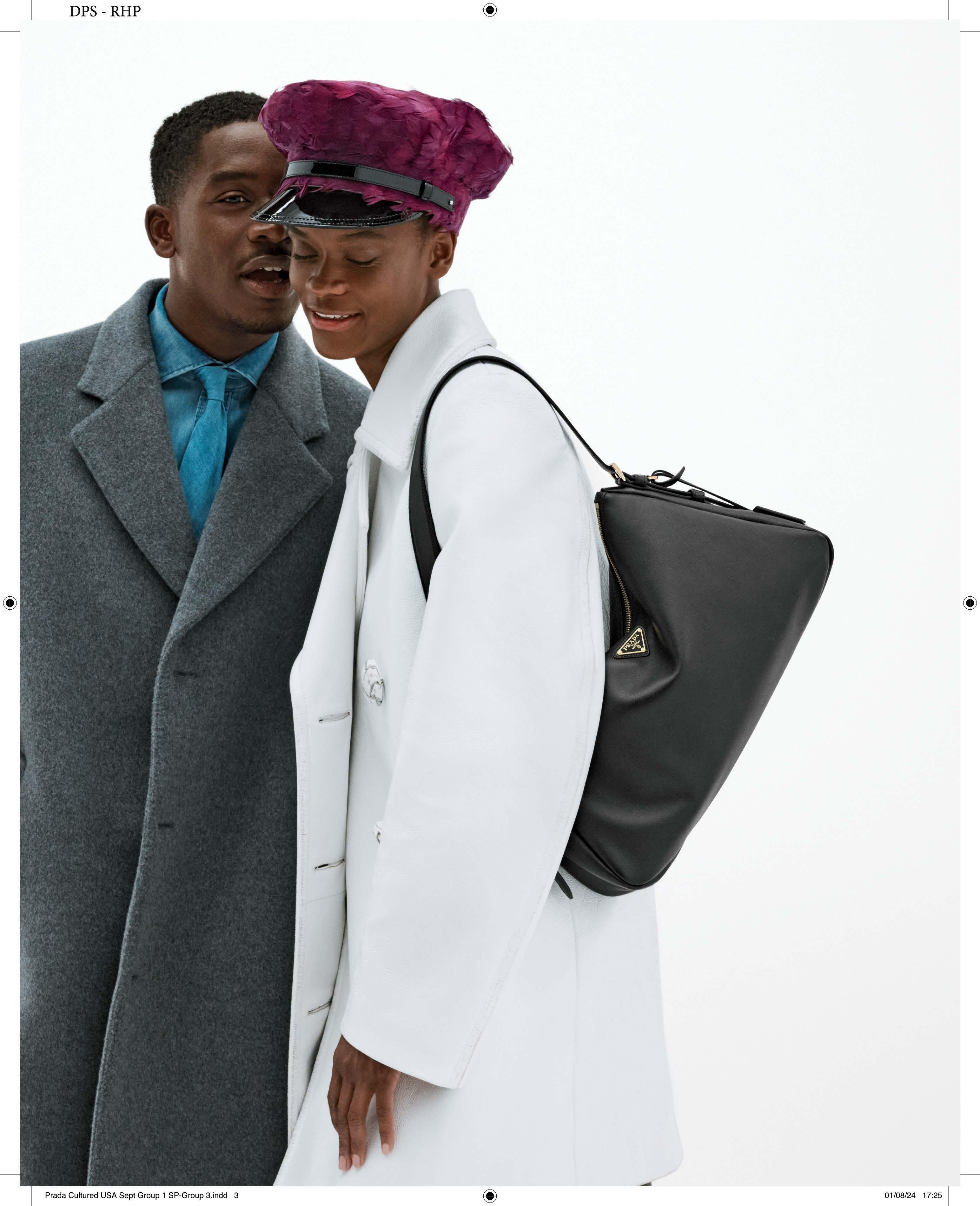

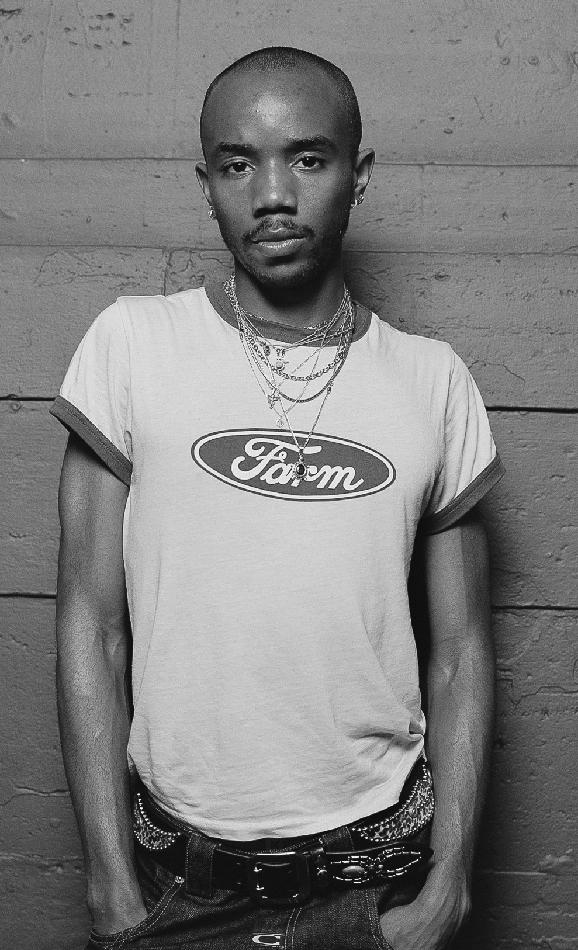

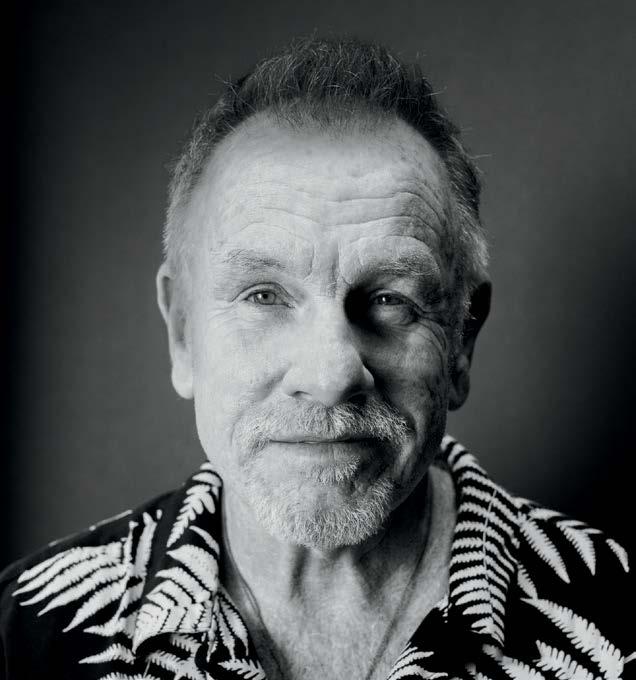

ARTHUR ELGORT Photographer

The work of Arthur Elgort is defined by its spontaneity. Models laughing while running with dogs or sipping wine populate the photographer's oeuvre. Since his breakthrough in the 1970s, this free-flowing practice has become a calling card. When CULTURED needed someone to drop by the legendary Grace Coddington’s home for an intimate shoot, who better than her longtime collaborator? “I had a great time photographing Grace—we always have fun together,” he recalls. “Since we’re both out East for the summer, it worked out perfectly.”

“I had a great time photographing Grace Coddington—we always have fun together.”

Photographer

Nicolas Ghesquière’s Fall/Winter 2024 collection for Louis Vuitton may have been inspired by the house’s history, but through the lens of photographer Quil Lemons, the pieces appear futuristic. “I came of age during his time at Balenciaga,” notes Lemons. “You had to be blind not to see the influence of Ghesquière’s Balenciaga era. His time at Vuitton is equally poignant, and it’s funny to see his codes—Ghesquière-isms!” The photographer infuses a sense of play and seduction into the contemplative collection, continuing his tradition of reimagining fashion photography, which he’s tackled in the pages of Elle, Variety, GQ, and more.

LISA TADDEO Author

“I much prefer asking the questions to answering them,” admits writer Lisa Taddeo, “but when the interviewer is Shailene Woodley, who has an unflappable innate charisma and ability to get you to say everything, it feels like sunshine on my face.” For this issue, Taddeo spoke with the actor ahead of the release of the television series Three Women, based on Taddeo’s first nonfiction book and starring Woodley. The author, a two-time recipient of the Pushcart Prize and a 2023 O. Henry Award winner, followed up that 2019 bestseller with her 2021 debut novel, Animal, also set to make its way to the screen. Rounding out her trio of publications is a short story collection, Ghost Lover, published in 2022.

“I much prefer asking the questions to answering them. But when the interviewer is Shailene Woodley, it feels like sunshine on my face.”

—Lisa Taddeo

BEATRICE LOAYZA Writer

Actor Adria Arjona is gearing up for a speedy ascent this fall. For the issue’s digital cover story, the Blink Twice actor sat down with writer, historian, and editor Beatrice Loayza. “Like Arjona, I’m Latina, so I was particularly delighted and moved by her rich ideas about identity and artistic freedom,” Loayza says.

Stylists

“We used the term ‘chill billionaire’ as a narrative for this shoot,” explains styling duo Hardstyle of their cover story with musician Travis Scott. “We wanted the story to be about the synergy between Pieter [Hugo]’s photography and the energy Travis brings to the looks.” Hardstyle, composed of Peri Rosenzweig and Nick Royal, has studios in both London and Los Angeles. Known for their industrial hardcore aesthetic, the duo has helped shape the image of artists including Scott and Yves Tumor. The pair’s dynamic body of work, in addition to styling, encompasses creative direction, art direction, and fashion design.

“Maja Ruznic’s paintings about the cloistered, sleepless period after the birth of a child were profound, especially since my second child was a baby when I saw them.”

—John Vincler

“She struck me as incredibly warm and honest. Clearly, this is only the beginning of a luminous career.” The writer splits her time between New York and Paris, covering film and the visual arts for The New York Times, Criterion Collection, The Nation, and other publications.

JOHN VINCLER Chief Art Critic and Consulting Editor

For his debut as CULTURED’s chief art critic and consulting editor, John Vincler sat down with artist Maja Ruznic to discuss her upcoming Berlin solo debut. “I knew nothing about Maja when I first saw her paintings at Karma in New York in 2020, but her paintings about the cloistered, sleepless period after the birth of a child were profound, especially since my second child was a baby when I saw them,” he says. The writer and rare book specialist has contributed to The New York Times, Frieze, and The Paris Review.

For this issue, Jack Pierson contributed his thoughts on the emerging photographers poised to carry the medium forward for the second Young Photographers list. “They come from challenges and freedoms those in my generation both created for them and will never hope to surmount,” admits Pierson. “I’m pleased with the output of these young artists thus far.” Since his

arrival in the 1980s as part of the Boston School of photographers, alongside the likes of Nan Goldin, Pierson’s work has found its way into collections across the country, from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, as well as France’s CAPC and Switzerland’s Graphische Sammlung der ETH.

REBECCA BENGAL Writer

PIA RIVEROLA Photographer

“Meeting Adria Arjona and getting to shoot with her was absolutely fantastic,” says Pia Riverola. The self-taught photographer, based between Los Angeles and Mexico City, met the actor in LA ahead of Arjona’s busy fall slate of projects.

“Working with a Spanish-speaking talent and crew on set made the day feel special and super familiar,” she adds. Riverola’s portfolio spans fashion, still life, and architectural photography for the likes of Calvin Klein, Loewe, Apartamento, and Vogue, as well as exhibitions from London to Amsterdam and a sold-out debut monograph, Flechazo (2022).

Photography is evolving nearly as fast as the technology that produces it. In this issue, author Rebecca Bengal introduces the next generation of creatives shaping the character of the medium in the 2024 Young Photographers list. “It’s especially exciting to discover new photographers through the eyes of your favorite artists,” she says. “Justine Kurland, Dawoud Bey, Lyle Ashton Harris, and so many more of the nominators on this list are among those I revere and whose work I return to, and who are great champions of others.” Bengal is the author behind last year’s Strange Hours, and is known for her work in The Paris Review, Vanity Fair, The Guardian, and more.

Farah Al Qasimi’s practice involves hand-sewn puppets, falcons, African land snails, exorcists, and most recently, a Jack Sparrow impersonator. For this issue, she nominated a rising image-maker for CULTURED’s annual Young Photographers list. A 2021 Young Artists alum, her work can be seen in the collections of institutions around the world, including the Tate Modern in London, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, and Paris’s Centre Pompidou.

york 511 w 21st street october 17 — november 16

SARAH G. HARRELSON Founder, Editor-in-Chief

MARA VEITCH Executive Editor

JOHN VINCLER Chief Art Critic and Consulting Editor

ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT Senior Editor

COLIN KING Design Editor-at-Large

SOPHIE LEE Associate Digital Editor

JACOBA URIST New York Arts Editor

KAREN WONG Contributing Architecture Editor

NICOLAIA RIPS Styles Writer

CAT DAWSON

DEVAN DÍAZ

ADAM ELI

ARTHUR LUBOW

HARMONY HOLIDAY

GEOFFREY MAK

LAURA MAY TODD

EMMA LEIGH MACDONALD

LIANA SATENSTEIN Writers-at-Large

ALEXANDRA CRONAN

KATE FOLEY

Contributing Fashion Directors

GEORGINA COHEN European Contributor

JULIA HALPERIN Editor-at-Large

ALI PEW Fashion Editor-at-Large

JASON BOLDEN Style Editor-at-Large

EVELINE CHAO Senior Copy Editor

DELIA CAI Culture Writer

TOM MACKLIN Casting Director

SIMON RENGGLI CHAD POWELL Art Directors

HANNAH TACHER Junior Art Director

DOMINIQUE CLAYTON

KAT HERRIMAN

JOHN ORTVED

SARA ROFFINO

YASHUA SIMMONS Contributing Editors

PALOMA BAYGUAL

KATIE KERN

REBECCA GOODMAN

LYDIA LEE

GAURI KASARLA

NICOLETTE CAVALLARO

LEILA SHERIDAN

PHOEBE ROBERTS

SOFÍA TRUJILLO

MIA GOULD Interns

CARL KIESEL Chief Revenue Officer

LORI WARRINER Vice President of Brand Partnerships

DESMOND SMALLEY Director of Brand Partnerships

SOPHIA FRANCHI Marketing Coordinator

CARLO FIORUCCI Italian Representative, Design

ETHAN ELKINS

DADA GOLDBERG Public Relations

PETE JACATY Prepress/Print Production

BERT MOO-YOUNG Senior Photo Retoucher

JOSÉ A. ALVARADO JR.

SEAN DAVIDSON

SOPHIE ELGORT

ADAM FRIEDLANDER

JULIE GOLDSTONE

WILLIAM JESS LAIRD

GILLIAN LAUB

YOSHIHIRO MAKINO

LEE MARY MANNING

BJÖRN WALLANDER

BRAD TORCHIA Contributing Photographers

New York

Hilary Pecis

Warm Rhythm

September 4 – October 12, 2024

Mai-Thu Perret

October 25 – December 14, 2024

Los Angeles

Matthew Brannon

Le Gant de Velours, Traversing the Fantasy, and the Thousand-Yard Stare (Disparate Subjects Happening Concurrently, 1977–1979)

September 13 – October 19, 2024

Fred Eversley Cylindrical Lenses

September 13 – October 19, 2024

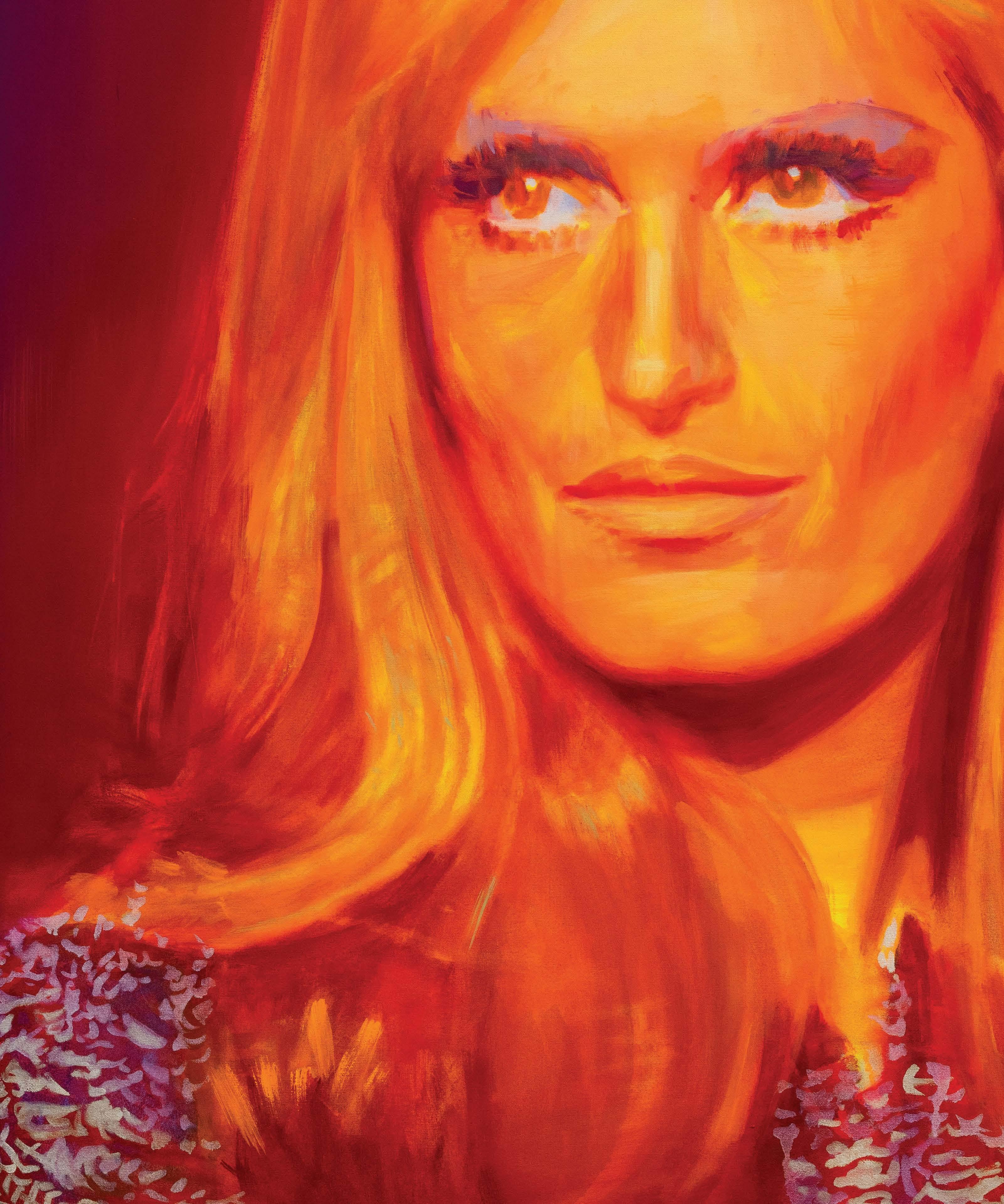

Jenna Gribbon

Like Looking in a Mirror

September 13 – October 19, 2024

Chase Hall

November 8 – December 14, 2024

Ruby Neri

November 8 – December 14, 2024

BY JULIA HALPERIN

“I can’t sleep … Of course I can’t sleep, because there is too much to look at.” So intones the narrator of Sara Cwynar’s Soft Film, 2016. For more than a decade, the Canadian artist has made videos and photographs that explore the

ties that bind together capitalism, desire, misogyny, and information overload in the digital age. Her latest film debuts at 52 Walker, David Zwirner’s Tribeca outpost, on Oct. 2. Two years in the making, it is her longest and most ambitious yet.

While much of Cwynar’s oeuvre explores items marketed to women—from dolls to clothes to makeup—this film, titled Baby Blue Benzo, takes as its point of departure a decidedly masculine lust object: the 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR Uhlenhaut Coupe. The compact silver car sold for $142 million in a secretive auction in 2022, becoming the world’s most expensive automobile. “I wanted to make a film about the arbitrariness of value and how things become important to certain people,” Cwynar explains.

The roughly half-hour-long video, shot on both digital and 16mm film, includes archival footage of car crashes and assembly lines, a dream sequence of ice skaters dressed in car-racing costumes, and shots of a bikini-clad model reclining on a fake replica of the prized vehicle.

“I WANTED TO MAKE A FILM ABOUT THE ARBITRARINESS OF VALUE AND HOW THINGS BECOME IMPORTANT TO CERTAIN PEOPLE.”

(Cwynar even hired a former car commercial narrator to enthusiastically cheer, “The Mercedes Benz!”)

Cwynar shot the fake car footage on an LA soundstage alongside other theatrical, oversized props like a giant clock and a piece of fake meat. It’s a nod, in her eyes, to Surrealism as both an expression of dreams and an increasingly common source of inspiration for advertising. The film alternates between a fast-paced, tightly stitched collage of industrialization (the urge to acquire, produce, and accelerate) and a slower register that embodies the anxiety of insomnia (the urge to slow down).

For Cwynar, these segments are two sides of the same coin. “The dreaming, sleeping part is about trying to reform yourself in a world where all these things are offered to you, but none of them are things you can access,” she says. The drive to possess and the drive to rest are twin expressions in our cacophonous, late-capitalist world—one where we’re all constantly yearning for both satisfaction and relief.

PASSION PROJECT: A BLISSFUL RETREAT IN UPSTATE NEW YORK.

BY LEE CARTER

“It’s a full interior curation offering casual style and slow living—therefore bliss.”

The Hudson Valley has long served as a leafy reprieve for New York’s creative set. A bucolic oasis just far enough from the grinding megalopolis is precisely what the design and lifestyle oracle Jenni Kayne was searching for when considering locations for the Farmhouse, the ultra-cozy luxury retreat—or, as she calls it, a “haven of hospitality”—she recently opened in the village of Tivoli on the banks of the Hudson River.

“It’s a full interior curation offering casual style and slow living—therefore bliss,” purrs the Los Angeles–based fashion and home accessories designer. Lauded for her own faultlessly breezy aesthetic and Californian je ne sais quoi, Kayne’s goal was simple: “I wanted to create a warm, timeless environment that immerses guests in my super laid-back, effortless look.”

But while the brand’s Cali-chic codes call for extensive ruminations on beige, the designer wanted the upstate experience to evoke the

splendor of the Northeast’s autumnal season. “The Farmhouse speaks to the unique landscape around it,” she says, citing the region’s “gorgeous fall foliage when the maples, oaks, and birches change color.” She recalls, for instance, a linen sofa she dyed a particularly rusty red—an entirely new shade for her home collection—before introducing it to the Farmhouse. “I’ve made sure nature is encountered at every turn [and] through every window,” she says.

Every inch of the Farmhouse has been exactingly conceived—down to a hand-tied plush silk rug, an exhaustively burled wood hutch, and a taupe throw in especially fuzzy alpaca wool. (These, and more than 100 additional pieces that adorn the Farmhouse, are available on her website). Yet, Kayne insists, “Nothing is too precious.Everything has a lived-in feel—it’s cozier and warmer than the Ranch back in California.” The Ranch—the designer’s previous foray into hospitality—all but broke TikTok when it was unveiled in 2022, instantly turning her

namesake brand into one of the most followed lifestyle companies on social media.

The remodeled New York state property also features vintage ceramics and furnishings (curated in collaboration with Galerie Provenance), an open-concept chef’s kitchen, a pool with panoramic views, and a barrel-shaped outdoor sauna with matching hot tub and cold plunge. For the wellness-oriented, a freestanding greenhouse offers the latest in skin and body pampering courtesy of Oak Essentials, Kayne’s skincare line.

For a burgeoning lifestyle empire with Ralph Lauren–level aspirations, designing a monument in one’s own image seems like a necessary yet daunting undertaking. For Kayne, the process felt natural. “The Farmhouse embodies everything that I’m about,” she says with a shrug. “I’ve always wanted to design a space where people could come together to celebrate life and its bounty.”

WITH HIS FIRST TWO NOVELS, THE AUTHOR MADE HIS NAME AS AN UNFILTERED, INTOXICATING ALCHEMIST OF GAY PHYSICALITY. HIS THIRD BOOK, OUT THIS SEPTEMBER, SEES HIM ENTER NEW TERRITORY.

Garth Greenwell’s third novel, Small Rain, opens with the poet narrator experiencing a gut-wrenching pain that eventually lands him in the ICU at the height of Covid. Those familiar with the author’s work won’t be surprised he’s writing about anguish and the body. His debut novel, What Belongs to You, explored the Venn diagram of those themes through the lens of a relationship between an American professor and a sex worker in Bulgaria. It established him as one of the great gay writers of our time, someone who paints the cocktail of pleasure, pain, and power that queerness invites with unabashed alacrity and almost cruel beauty. Writing about his second book, Cleanness, fellow queer literary giant Alexander Chee described Greenwell as one who “maps the worlds our language walls off—sex, love, shame and friendship, the foreign and the familiar—and finds the sublime.” Small Rain, which comes eight years after Greenwell’s debut, is a departure for the 46-year-old author—in location (swapping Europe for the Midwest), length (his longest), and tone. To mark its release, I sat down with the writer to discuss the book’s preoccupation with meaning, his take on autofiction, and why making queer pride obligatory is a mistake.

ADAM ELI: THIS BOOK IS DIFFERENT FROM YOUR FIRST TWO BOOKS IN TERMS OF CONTENT AND VIBE. THE FIRST TWO WERE A LITTLE MORE EDGY AND EXTREMELY SEXY. GARTH GREENWELL: It’s true that based on my first two books people thought of me as someone who writes about sex in a certain way, and I’m very happy to be thought of in that way. In this book, there is very little sex. Also, my first two books were about being an American abroad and the experience of foreignness. Not only is this book set in the United States, but in the American heartland—a small Midwestern town.

With that said, the books are continuous because when I step back and ask myself what I’m really writing about, the answer is always, “How do human beings make meaning?” Sex is one way human beings make meaning. Love is a way human beings make meaning. Religion is a way human beings make meaning. And art is a way human beings make meaning. This is a book about someone who in his early 40s is struck down by a really scary, potentially fatal medical crisis, and confronts questions that he didn’t anticipate confronting for another 20 years about the meaning of his life. His life has been a life devoted to art. The book asks, what is the value of that?

ELI: PEOPLE ARE OBSESSED WITH KNOWING WHICH PARTS OF BOOKS ARE INSPIRED BY

BY ADAM ELI

THE AUTHOR’S REAL LIFE, ESPECIALLY FOR QUEER AND FEMALE AUTHORS. I AM NOT INTERESTED IN WHICH ASPECTS OF SMALL RAIN ARE INSPIRED BY YOUR REAL LIFE, BUT I AM INTERESTED TO HEAR YOUR THOUGHTS ABOUT THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN AUTOFICTION, MEMOIR, AND NOVEL. GREENWELL: Autofiction is a term I feel super alienated from. I kind of think the term itself is bogus. Using one’s own experience as found material, which one can transform, recontextualize, and surround with invention, is the oldest game in literature. The tradition of writing that I’m working within goes back to Saint Augustine. The philosopher Charles Taylor talks about Saint Augustine as the origin point for the idea that within any particular experience can be found a meaning that is universal.

The idea that there is something new, marketable, and therefore faddish in a certain kind of writing that combines lived experience with invention and essayistic writing doesn’t make any sense to me. It’s always been clear to me that, even though there are certain portions of my books that hew pretty closely to my lived experiences, I am not writing memoir. I am writing fiction. If you call something nonfiction, you’re establishing an important contract with the reader that you’re not going to make things up in that way. If I call something nonfiction, then I am going to do my best to write in a way that bears an allegiance to an objective fact-checkable reality, and if I depart from that, I’d make those departures very clear to the reader. In writing fiction, I have no allegiance to that kind of shared reality.

When I do use my lived experience, I do so because it seems aesthetically compelling—beautiful or dramatic in a way that’s appealing. With that said, it’s also true that I use art to think about things in my own experience that are really bewildering. When I am completely bewildered by something,

that’s when I know I have to write about it. I’ve been open about having a medical crisis similar to the narrator’s, but our experiences in the hospital are totally different and the kinds of intimate relationships he forms with the people who take care of him are totally fictional. I keep waiting for somebody to point out, in the irate way that people sometimes point out these things, that in a real ICU there would never be a single nurse who would be so present, because it would involve one nurse doing too many shifts. But I wanted to explore the relationship that forms between a caregiver and a patient, and having one nurse more present allowed me to do that.

ELI: EARLIER THIS YEAR, I SAW YOU IN CONVERSATION WITH ÉDOUARD LOUIS, AND YOU SAID SOMETHING SO BRILLIANT ABOUT SHAME THAT REALLY RESONATED WITH ME. IT PERTAINED TO THE IDEA THAT, GROWING UP, IF YOUR SHAME HAD BEEN REMOVED THERE WOULD BE NOTHING ELSE LEFT OF YOU.

GREENWELL: I think we were talking about this idea that there is an original, pure self beneath that shame, beneath homophobia, beneath these learned things. I don’t believe that, because growing up in Kentucky in the ’80s, there was nothing except shame for me to make a self out of—until I found opera at 14. But by then I was already a self, I had learned so many things, I was having sex, etc. I needed shame because what else could I have made a self out of? The idea that we can find a pure self by erasing shame, violence, and homophobia rings utterly false to me.

The question should not be, How do I get rid of this shame? That way lies madness. Instead, the question should be, What can I do to make shame not simply a negative repressive force in my life? How can I make something productive of it? That is the great genius of queer people. The history of queer art is taking stigma and turning it into style, into solidarity, into pleasure. Those all seem to me like radically productive uses for shame.

I think it’s a mistaken impulse to want to deny shame, to make a kind of pride obligatory. Like all attempts to repress genuine feelings, it can make us monstrous. But if instead we can view shame as a productive way to create beauty and change in the world, then I feel very grateful to shame. Without it, I would not be an artist. I would not be someone capable of love in the way that I am. I would not be recognizable to myself had I not been shaped by certain lessons, the legitimacy of which I absolutely reject. And yet I never get to be someone who wasn’t taught those lessons.

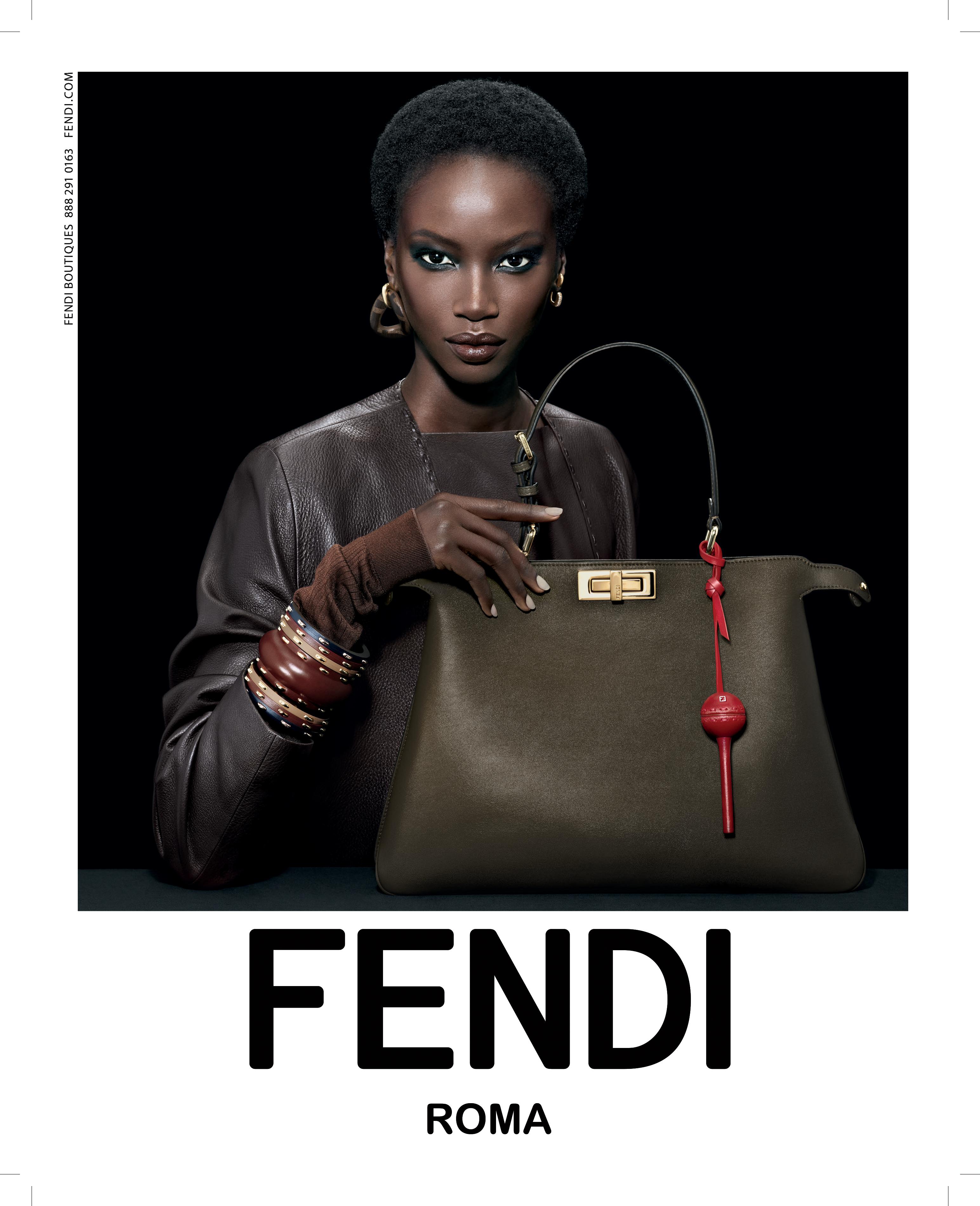

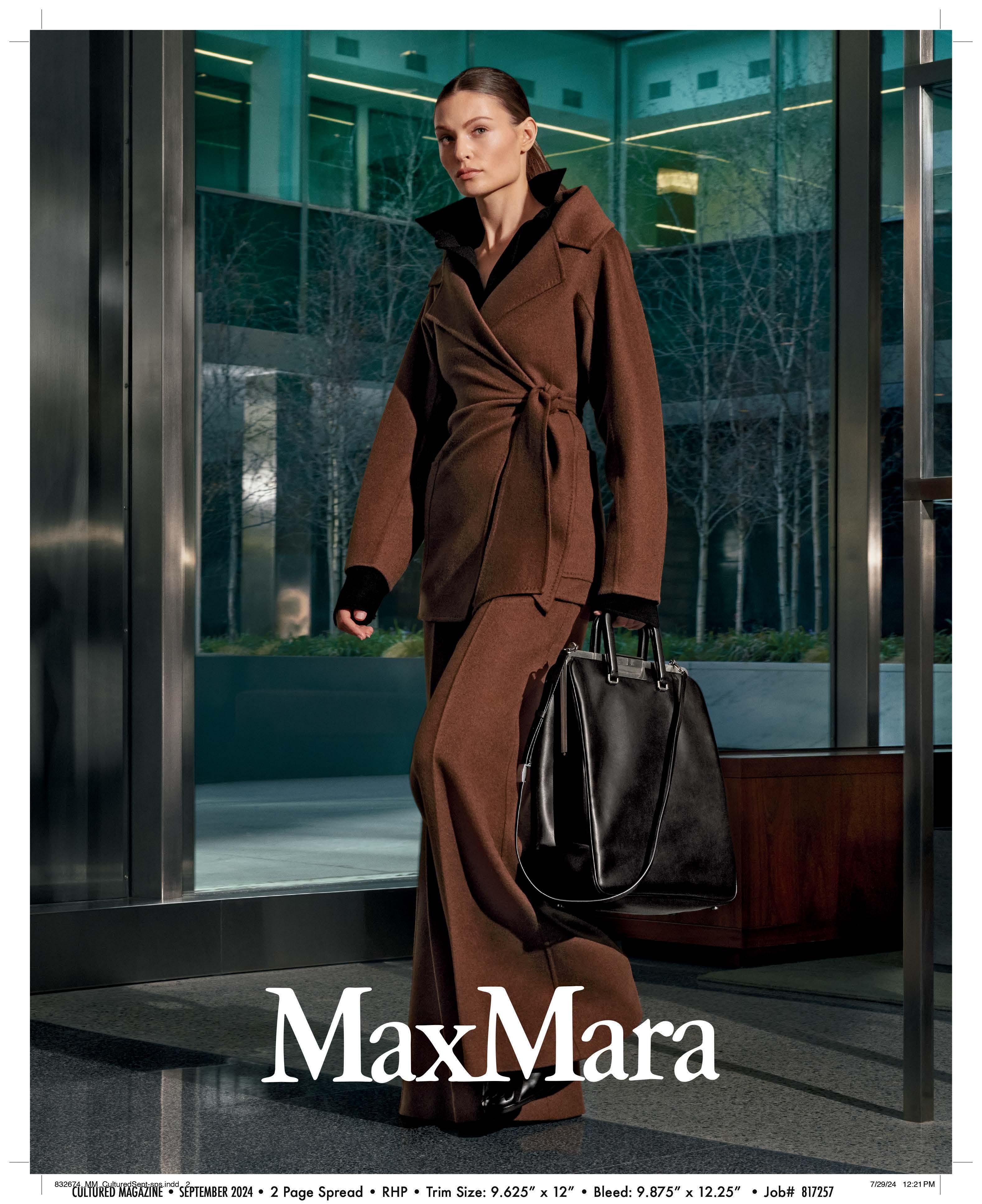

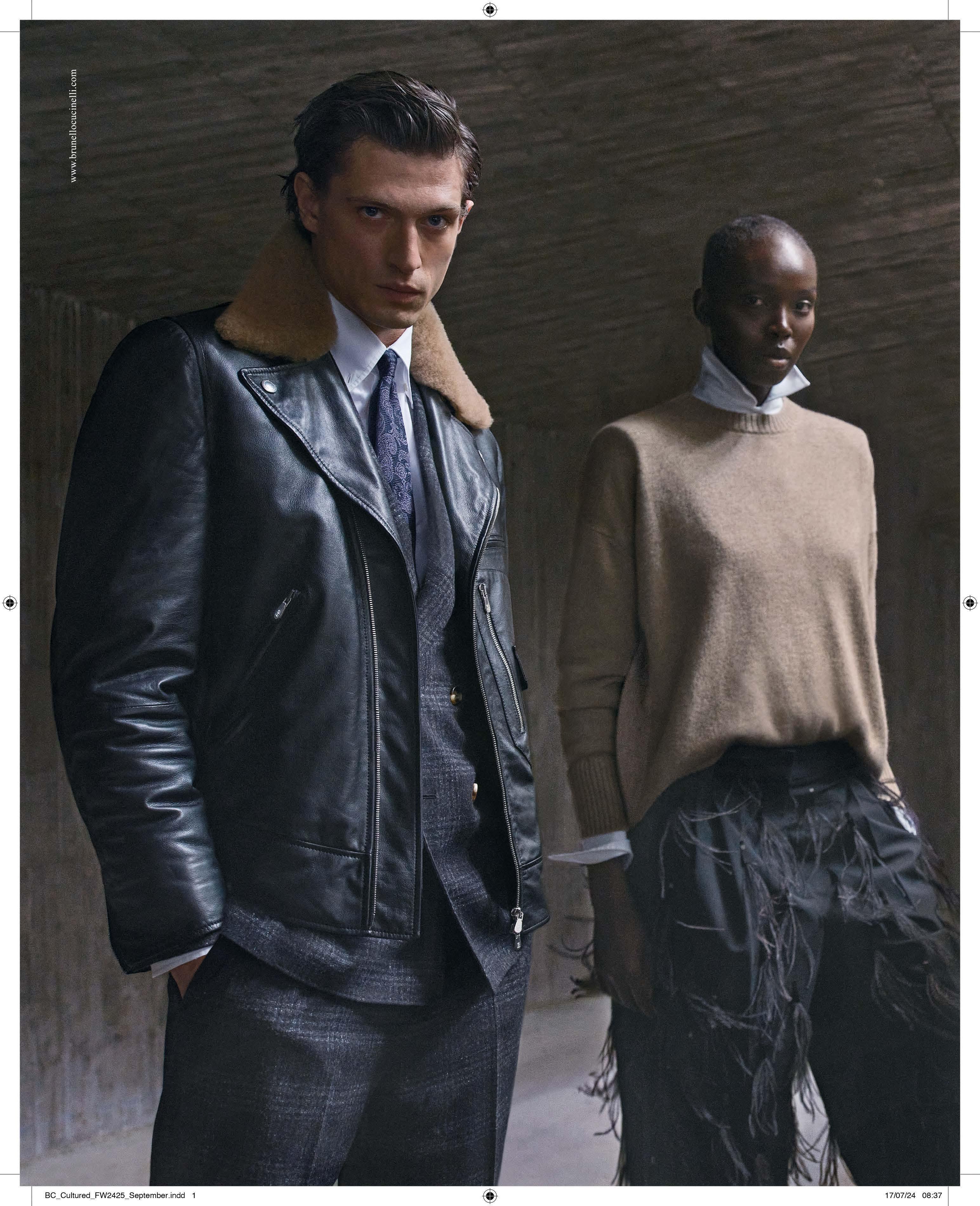

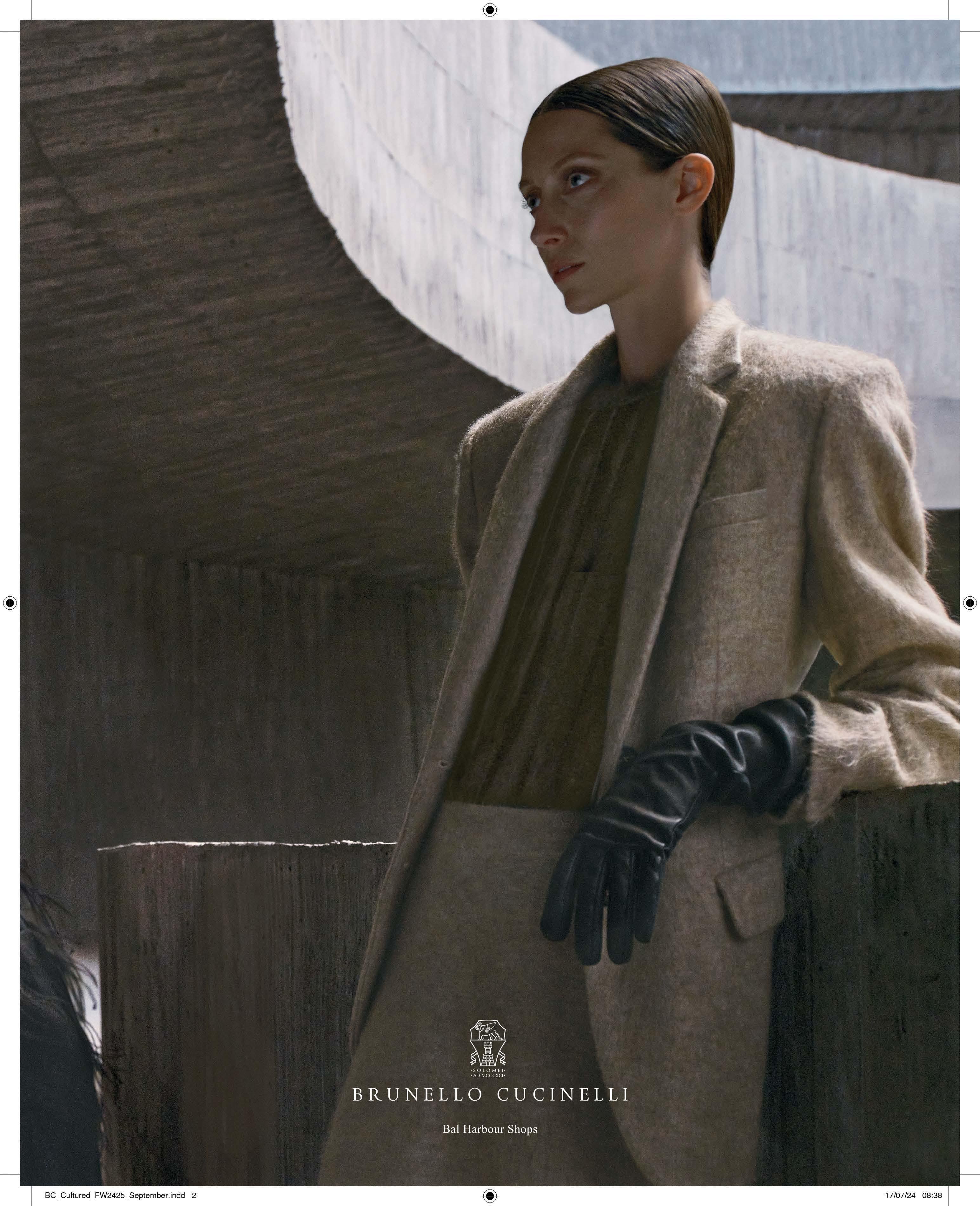

Alexander McQueen · Audemars Piguet · Balenciaga · Balmain · Bottega Veneta · Brunello Cucinelli · Bvlgari · Byredo · Cartier

Celine · Chanel · Chloé · Christian Louboutin · Courrèges · Dior · Dolce&Gabbana · Fendi · Ferragamo · Ganni · Gentle Monster

Givenchy · Graff · Gucci · Harry Winston · Hermès · IWC · Jacques Marie Mage · Lanvin · Loewe · Louis Vuitton · Marni · Max Mara

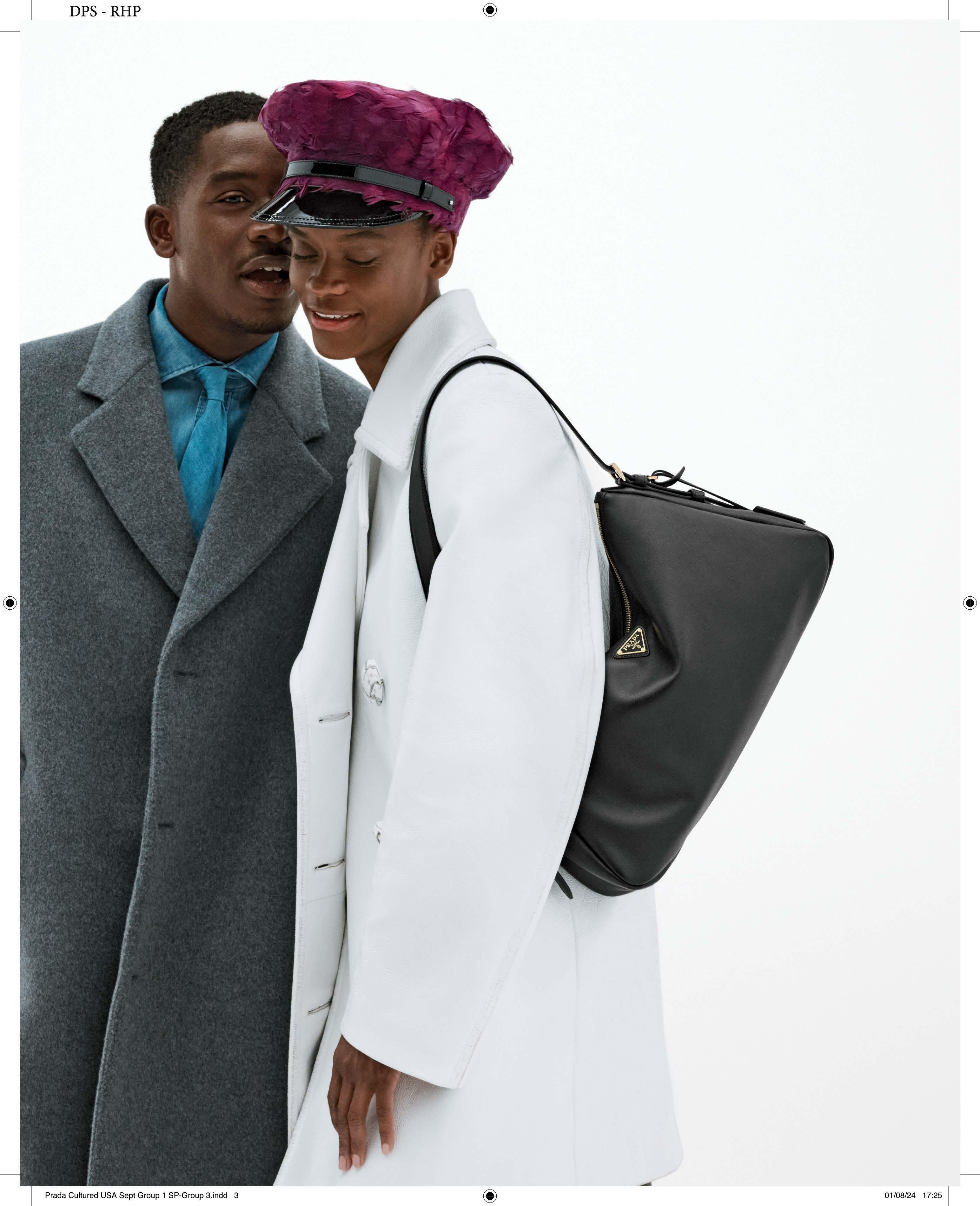

Mikimoto · Missoni · Miu Miu · Moncler · Oscar de la Renta · Prada · Ralph Lauren · Roger Vivier · Saint Laurent · Stella McCartney

The Webster · Thom Browne · Tiffany & Co. · Vacheron Constantin · Valentino · Van Cleef & Arpels · Versace · Zegna · Zimmermann partial listing

Valet Parking · Personal Stylist Program · Gift Cards · Concierge Services

Before a character in a film even utters a line, their clothes are speaking volumes. For out-of-focus extras, sometimes clothes are the only way to do the talking. Here, the costume designers behind three major fall releases share the stories, challenges, and inspirations behind their most revealing looks.

By Sophie Lee

In this year’s Cannes Palme d’Or winner, a 20-something stripper in New York’s Brighton Beach, played by Mikey Madison, finds herself in a whirlwind romance with the son of a Russian oligarch, incarnated by Mark Eydelshteyn. The fast-paced misadventure—the latest from director Sean Baker—is styled with riveting precision by Jocelyn Pierce, who was fresh off The Sweet East and Hit Man when she got the call.

“I started by pulling really glossy magazine images. We wanted to focus on the aspirational vibes a lot of the characters have in the film. Sean Baker is, at his core, relentlessly authentic. We spent so much time with the people of Brighton Beach, and we started mixing the magazine versions with the authentic versions of these people.

We didn’t get to talk to any Russian oligarchs or their sons, but we did a lot of research. For Mark Eydelshteyn, my initial boards were all Gucci, Balenciaga, and Louis Vuitton—your usual

suspects—but he’s so nuanced and he’s still a kid in a lot of ways. So, we mixed a lot of that luxury with streetwear. When you’re 21, you think you know it all, but there are clear signs to the rest of the world that you’re still very young. For the wedding, we chose a blazer and paired it with basketball shorts. Mark introduced us to a lot of Russian designers, and we got to work with a lot of small New York labels. Mikey Madison was also really involved. Ultimately, good actors know what’s best for their characters. She had done so much rehearsal, learning to pole dance and lap dance, and the

costumes that she had been rehearsing in … she lived in them as Anora for so long that some pieces felt really right.

When we went to Cannes, there were like 31 crew members. I remember talking to people from other films and they were like, ‘Wow, the Anora crew rolls so deep.’ It’s such a surreal experience to be making a film with such a tiny group of people and have it win the Palme d’Or.”

In Zoë Kravitz’s directorial debut, a group of young women (including Naomi Ackie and Alia Shawkat) are swept off to the private island of a charismatic playboy and legendary party host (Channing Tatum). Upon arrival, the women are given clothes—white swimsuits, wide-brimmed sun hats, and gowns—curated off-screen by costume designer Kiersten Hargroder (You, Supergirl, and Borat Subsequent Moviefilm). Here, she discusses the sweat-soaked fever dream in Mexico—part The Row, part rope play—that led to the blockbuster film.

“It’s well known how stylish Zoë Kravitz is, so it’s no surprise that the film has a sense of style. A lot of her inspiration came from vintage photos and fashion ads, a bit of that timeless appeal. In the film, there’s a lack of clothing options—as soon as you get to this island, you’re molded into an object for men’s affection.

The men in the film are able to reveal a bit of their personality through their clothes, while the

women are given stuff that just magically fits—it shows their interchangeability and replaceability. Zoë has shared what inspired her to write the script —how women are treated in the industry and beyond. It’s a film about control, but it’s also about how underestimated women are.

We needed a gown that looked pretty and elegant, but it also had to be used as a means of torture. That’s hard to do, right? How do you make

something that could tie someone up but also looks elegant? We had to make like 70 of those. Some of them are bloody, others stay clean. All of Channing Tatum’s shirts were made for him. There’s a famous shirtmaker here in Los Angeles, Anto, that churns them out. We had to change Channing’s shirt every 10 minutes because it was so humid. It’s no surprise that some of the pants he wears are The Row, one of Zoë’s favorite brands.”

In the 36 years since the release of Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice, Winona Ryder’s young character has grown up and had a daughter of her own—played by Jenna Ortega in this year’s sequel.

To bring the film’s fantastical characters to life, Burton tapped his longtime costume designer and four-time Academy Award winner Colleen Atwood. Here, she discusses the art of maintaining a decades-long collaboration and how she reimagined Michael Keaton’s infamous striped suit.

“ Tim Burton and I have worked together on so many fun things, we’ve developed a shorthand. When we begin a project, Tim describes what he wants to do with characters. Then I gather images, fabrics, and swatches for his reaction. I don’t really use mood boards—it’s broader than that for me, from weird masks to piles of fabrics.

Once we’ve settled on these ideas, we meet with actors and start the fitting process. When I met with Michael Keaton, we talked about the suit—the fact that the character has gotten a little older is reflective in the fit of the suit and its aging. In this new film, the merging of modernity with the timelessness of the underworld shows a passing of time that helps set up the story.

Tim visually uses the empty space and unique angles to create his style of framing. For me, it is about making sure the costume can be seen in a sculptural way, as well as in close-ups. I think the layers of people in the underworld—from the receptionist to the soul train dancers who form the backdrop—along with Monica Bellucci’s black dress are my favorite details.”

OVER THE LAST DECADE, ROBERT WUN HAS MADE A NAME FOR HIMSELF BY EMBRACING THE LABORIOUSNESS AND PRECARITY OF HIS CRAFT. THE HONG KONG–BORN COUTURIER HAS NO INTENTION OF SLOWING DOWN.

BY JAYNE O’DWYER

“I never have a muse,” declares Robert Wun. While many of his peers find inspiration in human subjects, the Hong Kong–born, London-based designer is more interested in the thorny forces that act upon them—like fear and grief. Wun credits this resistance to the corporeal with the critical success of his designs, which have been worn by the likes of Björk and Cate Blanchett. “When I choose a subject that is not human, the language can be so much more out of the box,” he adds.

For the past 10 years, Wun has been crafting a sartorial vocabulary all his own. Speaking on Zoom after his Fall/Winter 2024 collection “Time” made waves at Paris Haute Couture Week, he confesses to feeling caught between recent success and the looming deadline of his “Home” show in Hong Kong in early September. “I made this collection to question ... what we are expecting from creatives nowadays,” asserts Wun. “The industry forces people to feel they can never stop. It’s like, ‘You either deliver or you’re out.’” This moment of reflection comes after a quick succession of hardwon accolades: Wun founded his namesake label in 2014, cutting his teeth with ready-to-wear before pivoting to couture in 2022. He made his runway debut in Paris in January 2023, becoming the first designer from Hong Kong to join the haute couture calendar.

If “Time” was a celebration of his achievements, it was also an acknowledgement of the pressures and precarity of his craft. The show opened with an homage to falling snow, taking ephemeral beauty —and its inevitable demise—as the main focus. “Endings can be rather graceful and powerful,” he muses. “What if we embraced that more, and were inspired by them?”

For Wun, couture remains a way to resist this churn —a time-honored art form that cannot be expedited, and where he is free to take his themes to their fullest extent. A Robert Wun show treats the runway like a film set, and the backdrop for “Time” was no different. Animated projections offered a fantastical backdrop for the designer’s magnetic looks, inspired by the seasons and fleeting natural wonders (Wun cites Alexander McQueen’s runways as inspiration).

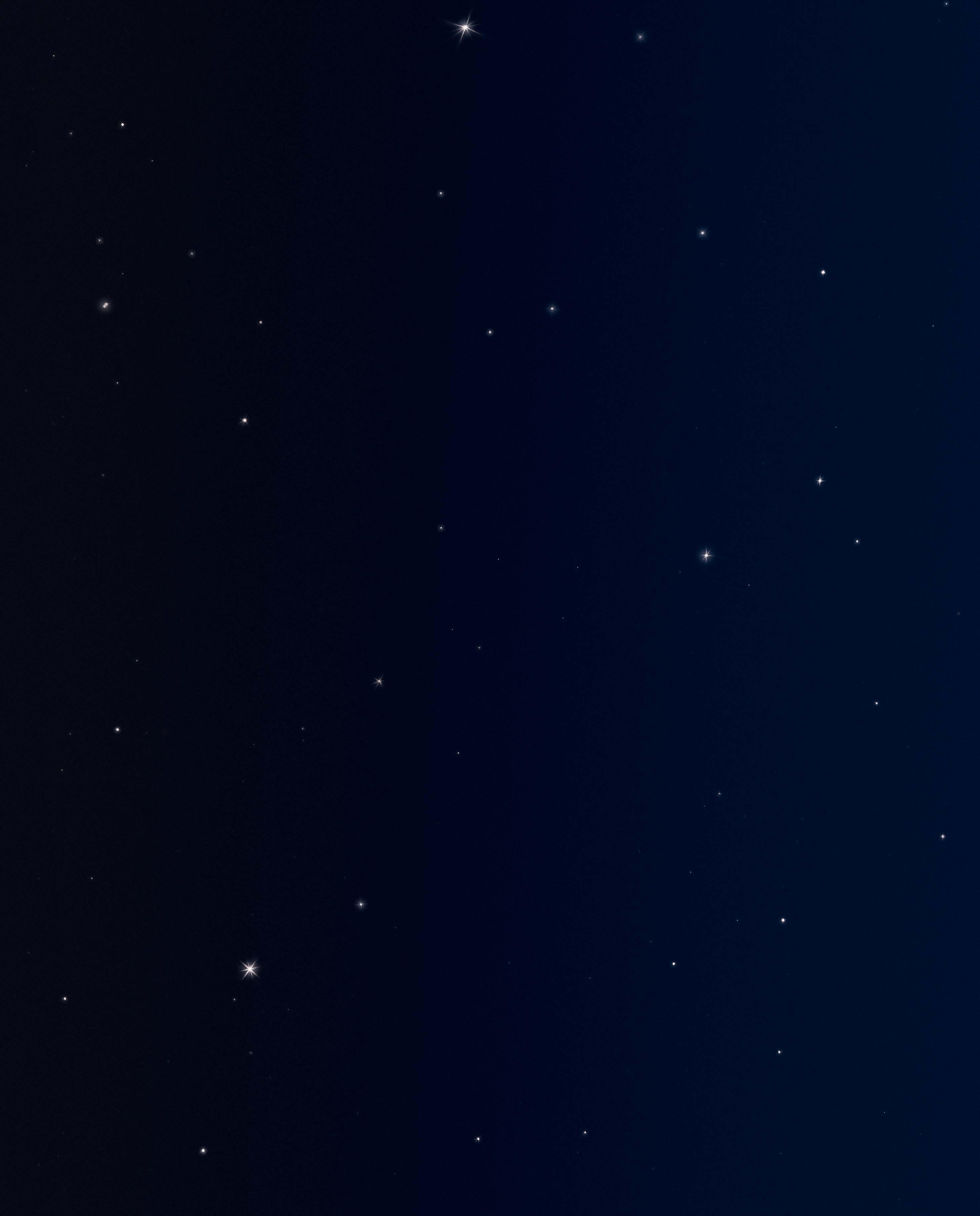

As the last looks swept the Fall/Winter 2024 runway, Wun sent out four creations that demarcated the human body: flesh, muscle, bone, and soul. The final gown—soul—was topped with a glittering shroud that evoked a constellation of stars. In Robert Wun’s reality, endings aren’t always such a bad thing.

“Endings can be rather graceful and powerful. What if we embraced that more, and were inspired by them?”

ARCHITECT ELIZABETH ROBERTS AND FASHION DESIGNER CECILIE BAHNSEN PRIZE INTUITION AND RESOURCEFULNESS OVER PERFECTION. HERE, THEY COMPARE NOTES ON CREATING OPPORTUNITIES FOR “ACCIDENTAL BEAUTY.”

It was a chance meeting at a dinner party in Copenhagen that first brought together New York–based architect Elizabeth Roberts and Danish fashion designer Cecilie Bahnsen. Though they operate in different mediums—one with space, the other with the body—a sense of camaraderie sparked between them instantly. Ahead of the publication of Roberts’s first monograph—Elizabeth Roberts Architects: Collected Stories from Phaidon, out this month—and the debut of Bahnsen’s Spring/ Summer 2025 collection during Paris Fashion Week, the two women sat down to discuss motherhood, the beauty of imperfection, and why there’s nothing quite like bespoke designs.

ELIZABETH ROBERTS: I love people who are doing really unique work, and your work stands out. You’ve got such a strong voice—it’s so soft, yet with an attitude. It’s hard to do things that are so your own, yet so universally admired.

CECILIE BAHNSEN: When we first met, we couldn’t stop chatting. Even though our fields are different, there are so many overlaps in how we produce. We put a lot of passion and energy into our work, but we also have this unpreciousness about what we do. We want the women that wear our clothes or live in our spaces to really feel like they’re them—that our designs don’t outshine them.

ROBERTS: I’m often working for one person, so I dive deep into what they’re after, but sometimes it can go too far. I can fall into their fantasies too much and create something that can feel a bit too temporary. It’s nice to get people out of their heads, out of perfection, and into real stuff. Like, How is this gonna fare for the next 10 years? Can your kids spill yogurt on it?

When we met in Copenhagen, you had your dress clipped up on the side. You told me that originally you didn’t have this clip on your dresses, but your studio mates needed it because they ride their bikes to work every day. That’s a perfect example of the kind of attitude I love: the idea that things aren’t perfect when you’re done with them. When they go out in the world, they become better.

BAHNSEN: It’s like accidental beauty—the imperfection of these things that you explore as you live in it and make it your own. You’re creating this universe around your brand, but, once a woman puts it on, they add their own point of view and their own electricity to it. When I look at your work, I also see this unexpected choice of materials, which I really love. You strike a balance that feels quite intuitive and that is hard to put into words. I spend a lot of time refining that balance myself and trying to get it right.

ROBERTS: How did you decide to start your own brand?

BAHNSEN: I wanted a change of pace. I moved back to Denmark to try and do fashion in a slower and more conscious way. I wanted to stay away from some of the pressure you have in bigger cities, although I am very lucky that I get to come to New York and tap into that energy again. But I definitely have this stubbornness inside me. I wanted to create a brand with a strong female voice, but I also wanted to be a mom. Today, I couldn’t imagine doing anything other than what I am doing. Being a mom is a huge part of my inspiration and features so much in what I create. At the end of the day, I think it’s my stubbornness that has served me best.

ROBERTS: A very stimulating part of our jobs is that we’re both lucky enough to work with people whom we can pass our values down to.

BAHNSEN: That’s the most important part: The people you create with become family.

ROBERTS: And then they follow the life balance you’ve chosen, which is like, “Let’s not work until 3 in the morning. Ever. Let’s work really, really hard

“It’s nice to get people out of their heads, out

of perfection, and into real stuff.”

—Elizabeth Roberts

during working hours.” Those values used to be super rare in architecture. I want to be able to roam in the woods with my son on the weekend. I want to do beautiful things outside of work. Right now, you are quite busy, right?

BAHNSEN: Yes, we are working on the show for Paris. It’s two months from today. It’s a very special time where everything that you worked on for months comes together and you’re making sense of all the bits and bobs. It’s one of my favorite times with the team; we are working on the looks and starting to see the movement in the collection. Somehow, despite all this preparation, you still get surprised.

ROBERTS: For us, we finally finished my book. It’s interesting to have to put things to words, and to apply a narrative about what we’re doing. I’ve never done that before. We usually create things and then other people write about them.

BAHNSEN: It must have been very special choosing what to feature from your whole body of work.

ROBERTS: You can’t be too precious about it though. Besides Paris, are you focused on any special projects right now?

BAHNSEN: We’re going really intimate and doing some made-to-order pieces. We are using all our archive fabrics and creating new pieces out of them. Some of the dresses are like patchworks of different seasons together. We make them for the customer personally and we always know who she is. That one-on-one approach is so inspiring for us.

ROBERTS: I designed a store for Rachel Comey, and I remember her telling me that she could hear people thumbing through the clothes and trying them on. She loved the conversations she overheard —a mother and daughter shopping together and talking about her designs. That personal stuff is why I decided I was going to work with families and go deep—as a result, I developed a portfolio that is very personal. Now, even with big projects, we keep them that way—personal.

“You’re creating this universe around your brand, but, once a woman puts it on, they put their own point of view and their own electricity into it.”

—Cecilie Bahnsen

Photography by Julie Goldstone

By Ella Martin-Gachot

Thomas Houseago is making his New York comeback.

A new exhibition this fall, taking over three floors of Lévy Gorvy Dayan’s Upper East Side townhouse, will mark the artist’s first presentation in the city in 10 years. Calling from Tokyo this summer, he readily acknowledged the weight of the task at hand. He has never felt seen by the New York art world, although it witnessed watershed moments in his career, like the inclusion of his hulking Baby in the 2010 Whitney Biennial and his foray into the architectural realm with “Moun Room” at Hauser & Wirth in 2014.

“New York has never really been an easy audience for me in terms of the critical establishment,” Houseago admits. “It’s not a place where I’ve felt comfortable or safe.” He recalls a particularly unsparing review of a 2013 show at Storm King, in which a New York Times critic suggested he might need therapy. “He was right,” Houseago says. “In a way, what he was picking up from the work was correct.”

The Leeds-born, Los Angeles–based artist made his name in the late aughts with mammoth sculptures of mangled humanoid and animal forms whose weary stoicism often betrayed an unflinching vulnerability. Houseago’s self-described “fuck-it” behavior and high-octane ascent —accompanied by its fair share of name-brand collectors, mega-gallery drama, and celebrity friends—made him impossible to ignore. He was seemingly everywhere—until he wasn’t.

In 2020, Houseago left his practice behind. He was in the midst of a mental breakdown, battling preverbal trauma resulting from sexual violence he experienced as a child. “When I went into treatment, I was like, Sculpture is gone. I’m so relieved,” he remembers. “I’m never going to do that again.” He saw his sculptural output up to that point as a constant cycle of retraumatization. “I wasn’t in control [of the work at all],” he recalls. “I didn’t make it. It was making me.”

But with the help of an interventionist and care manager—Danny Smith, who died this past spring—he began to make his way back to art,

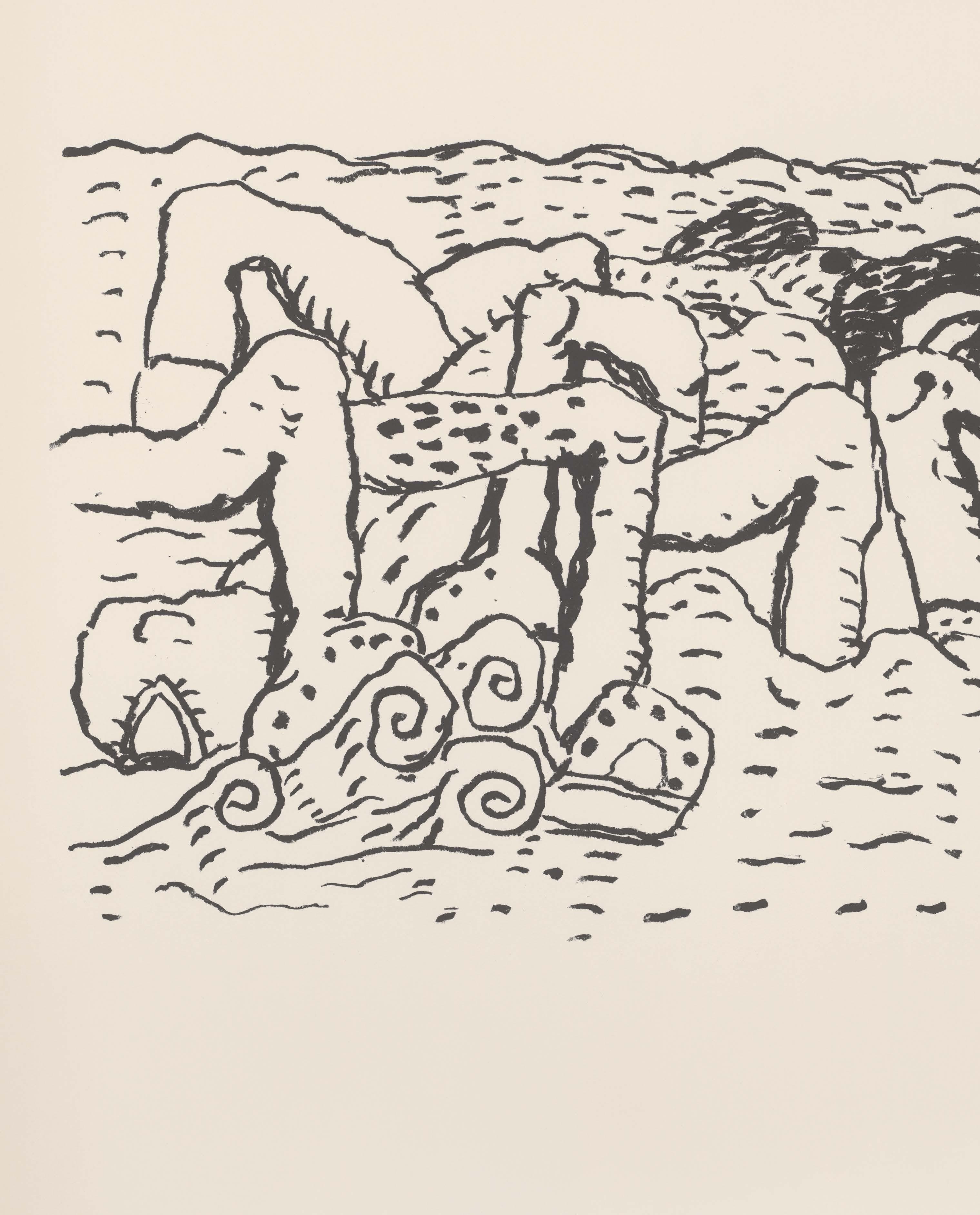

first with ink drawings of visions he’d had at an Arizona treatment center, then with painting, and finally, and most reluctantly, sculpture once again. The Lévy Gorvy Dayan show charts this “dark night of the soul.” The journey begins on the ground floor, with the heaviest work—both conceptually and literally—including a bronze minotaur that will greet visitors at the entrance. “The minotaur is the perfect metaphor for trauma, right?” Houseago notes. “Born out of perversion. Half man, half beast. Stuck in a maze it can’t get out of.”

The second floor sees Houseago sculpting on a smaller scale: His signature eggs populate one room at varying degrees of brokenness and a series of three-dimensional still lifes memorializes his gradual re-enchantment with the quotidian. The path to recovery is punctuated by a turn toward the celestial on the fifth and last floor, with a skylit mural depicting the phases of the sun and moon. “No matter how triggered or fucked-up I am, I always find the dawn beautiful,” Houseago concludes. “The whole show in a nutshell is: There’s hope. How do you become an ambassador of hope?”

“THE MINOTAUR IS THE PERFECT METAPHOR FOR TRAUMA, RIGHT? BORN OUT OF PERVERSION. HALF MAN, HALF BEAST. STUCK IN A MAZE IT CAN’T GET OUT OF.”

“THE WHOLE SHOW IN A NUTSHELL IS: THERE’S HOPE. HOW DO YOU BECOME AN AMBASSADOR OF HOPE?”

Victor Barragán and Betsy Johnson straddle the worlds of fashion and conceptual art, making work that tests the culture’s appetite for extremity. Here, the kindred provocateurs sit down to discuss the rewards of risking it.

Victor Barragán and Betsy Johnson are no strangers to taboo. Barragán launched his namesake label in 2016, shortly after moving to New York from Mexico City, and wooed the fashion set with designs that collapsed religious iconography, gay paraphernalia, and Internet subcultures into viral garments worn by the likes of Madonna and Rosalía. Then the designer made a radical decision: to drop out of the fashion week rat race and show off-calendar and outside the industry’s sanctified locations. His last presentation, which took over a militarized airport in Mexico City and reveled in the language of cults, Catholicism, and weaponized nationalism, was a testament to his ability to constantly upend what we expect from a brand. Johnson is a sartorial Swiss army knife—she casts, styles, creative directs, designs, and shoots—whose work has caught the eye of rappers, luxury houses, and the Internet alike. Last year, she launched Products, a project that alchemizes her interests in the aesthetic consequences of commodification and class. Beloved as she is by fashion insiders, Johnson is unafraid to skewer the industry’s shortcomings and package them for all to see. Here, the friends share how they drown out the noise—and make space for the stories they want to tell.

BETSY JOHNSON: I knew your work for maybe five years without knowing [the person] behind it. I have no idea how I came into your sphere.

VICTOR BARRAGÁN: You worked with some of my friends in Europe. Then I started seeing your name popping up all over the world. It was funny how we met at the Shayne Oliver show—I had no idea you were gonna be doing the styling.

JOHNSON: We were both wallflowers trying to stay out of the way of the chaos. How did you get into fashion?

BARRAGÁN: I come from an architecture and industrial design background. Then I quit and started doing fashion [full-time]. I started doing things here and there, and then I got popular on Tumblr really quick. I got pulled onto the fashion calendar kind of by accident, because people contacted me like, “We love what you’re doing, we wanna support you.” They threw me into the mix in New York, and I didn’t know what I was doing.

I always took fashion as performance mixed with a product. It was about storytelling for me. I started mixing everything: my art, my sculpture, my clothing, my music. You do something similar—you build your whole world in terms of the people you collaborate with and how you present things. You put yourself in the spotlight a lot, in your own language [which I do too]. We put ourselves out there, but we are not too reachable.

JOHNSON: People that are these “trouble-causing provocative auteurs in their field,” they’re always 360-degree kinds of people who are in their own universe. To be a storyteller, you have to have a story to tell. It’s a self-informed process. Every time I step into someone’s project, I’m never under a title. I just come in and support whatever storytelling they’re doing. It’s a collaboration, not this structured corporate format.

BARRAGÁN: How does your relationship with your audience influence the evolution of your work? You have so much attention online. People track you.

JOHNSON: These Reddit threads, like, “She’s here!” I’m like, Whoa, I’m actually being tracked [Laughs] The person I am in real life is so different to who I portray online. That’s part of the weird little character-building process I’ve gone through, and it’s a really liberating space to be in. It allows me to create and put everything I’m thinking into my work.

BARRAGÁN: My image online looks really crazy. It’s totally a performance. When people meet me, I’m like, shy. I’m not as crazy as I look on the screen. I express so much with my work, maybe not with words. My mind and words start sticking sometimes, so I use the brand as a form of expression. But I don’t interact too much with people I don’t know online. It’s hard and can be an empty place to do that, but I feel like the audience always wants to be part of it, and I love that. I feel like I’m not talking to a wall.

JOHNSON: Do you feel like there’s a next step for you with the community that you’ve built with your storytelling, to push people to also be provocateurs with everything going on in the global cultural landscape, which is a whole other spectrum of bullshit?

BARRAGÁN: You always feel like you have to push it more. My work became more conceptual through the past years. Now, I’m doing a movie and … there’s my love for music. I love how these intersections keep provoking fashion in a different way. It’s always the more risky people who take these new ways to communicate, and then you will see all this resonate on bigger brands in the future, for sure.

JOHNSON: I feel like [bigger brands] are getting less risky. Everyone’s scared out here. The market’s so fragile. When I’m in my studio, we’re talking about the craziest ideological concepts and … we’re getting into the nuances. When people come in, they’re like, “Wow, these conversations are crazy.” I’m like, “Yes, if you work at [a big house] you’re knocking out email marketing campaigns.” You’re not really getting into the nitty gritty of cultural references and how they translate into the work.

BARRAGÁN: I see how the bigger brands have to move so fast that they feel rushed somehow. There are all these mini trends. The algorithm on TikTok is throwing so many new things so they can market anything. At a certain point, it’s gonna collapse.

JOHNSON: There has to be a point where everyone’s overwhelmed. Most of the people I resonate with creatively, even on a friendship level, are like, “Let’s slow down.” I won’t post something for like a year; I’ll let it simmer for so long, and I’m at peace with that. I feel like the most provocative thing you can do is to slow down and trust that your storytelling is strong.

BARRAGÁN: No, it is. The algorithm is so controlled, so you feel the pressure to keep pumping content. I didn’t know this, but the algorithm tracks your face. If you post your face, it’s gonna show it to more people. That was why I started doing the censored face on the brand account. The algorithm started taking my posts down because they thought I was doing something shady. I learned that when I took a class about Instagram and managing my brand. They were like, “Don’t be surprised if you post a selfie and that selfie gets more likes than your actual work.”

JOHNSON: Oh my god. That’s insane.

BARRAGÁN: I guess the selling point is you in whatever you do. I was so conflicted about like, Should I just keep posting some sexy pictures of men? Boom, worked. And I haven’t done that. That’s why I post a lot of memes and things like that. I was like, Damn, this is so not fun. You have to keep playing this game with it, so you can actually show your work.

JOHNSON: It’s blocking the provocateurs because it’s promoting this influencer culture, which is not provocative at all. That gets me on to this next point about intersectionality and how art and fashion are potentially fusing more recently. I really am sensing this a lot. The art world was so abstract and inaccessible to me. I would never even try. And then I was in the art world and everyone was like, “Oh, you are an artist though.”

BARRAGÁN: I started in fashion and people told me, “You are an artist using clothes. Just keep it like that. If you put it in a box, you are always gonna be overwhelmed, controlled.” I definitely see you as an artist first, and I feel like there’s a crazy thin line where, if you are in the fashion world, your work could have less meaning because it’s a product. Art is a product too, but it’s just different in the way it’s perceived.

JOHNSON: These terms—“jack of all trades, master of none”—have been planted there to make people like us, aka provocateurs, feel as if you have to be one thing. You’re less dangerous if you’re one thing. Your ideas can’t spread as vividly if you are stuck in one craft.

BARRAGÁN: Definitely not.

JOHNSON: If you could use one word to describe how fashion is right now, what would it be?

BARRAGÁN: Cheap. What about you?

JOHNSON: Uninspiring. Sorry guys, but it really just is uninspiring.

BY ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

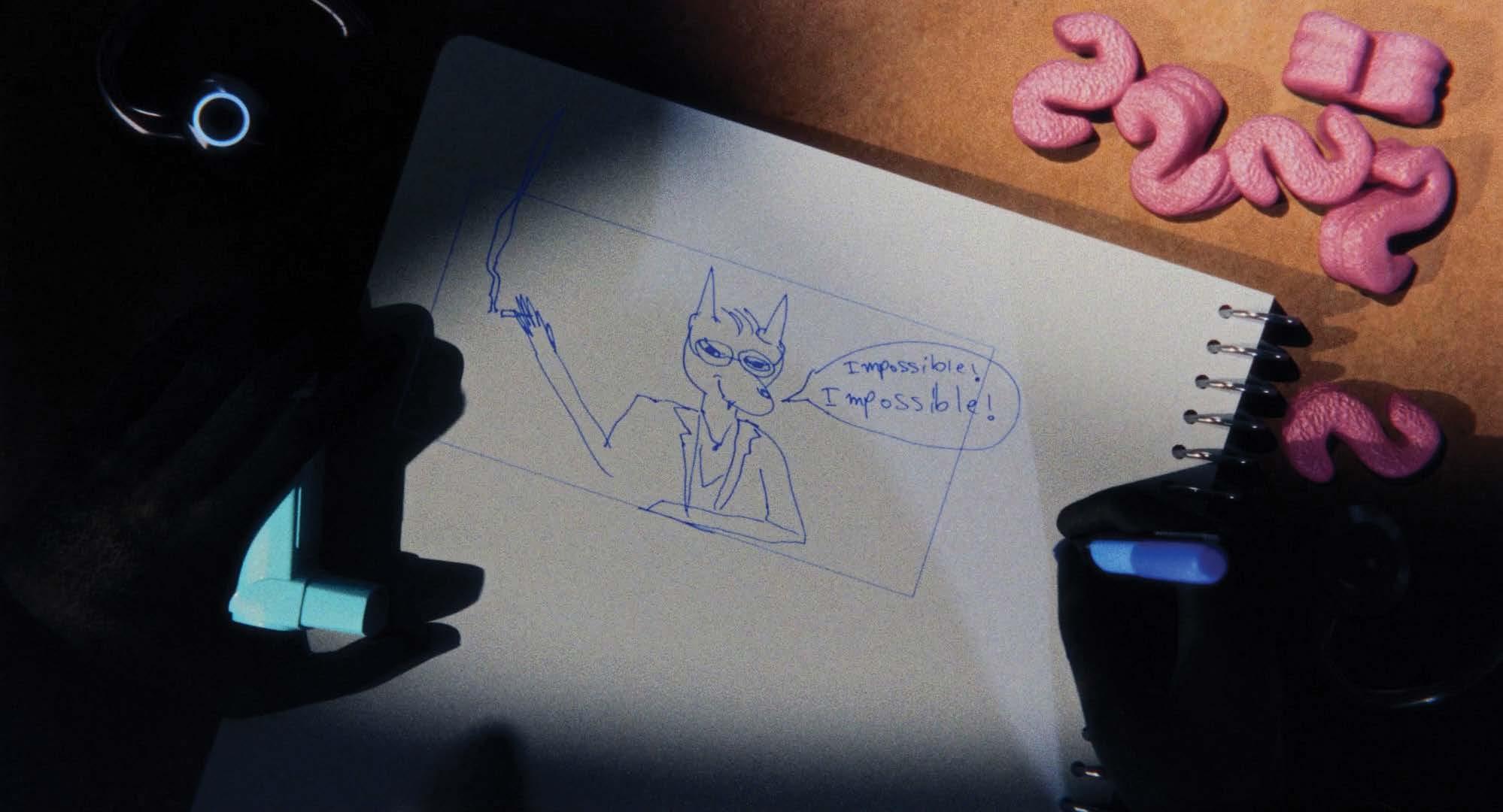

The New York–based artist sits down with her longtime co-conspirator Orian Barki to discuss her latest caper: an ambitious exhibition at the Fondazione Prada.

Over the past decade, Meriem Bennani has filtered the crushing estrangement and feverish pace of postmodern life through a delirious yet distinctly earnest lens. Topics as disparate as immigration, girlhood, and the aftershocks of colonization in the Maghreb surface in the artist’s work, which can take the form of a scrappy reality TV show or a spinning tornado powered by electric bike motors.

“For My Best Family,” a new exhibition opening Oct. 31 at Milan’s Fondazione Prada, is Bennani’s latest world-building exercise. On the ground floor, a soundtrack composed with Cheb Runner will accompany hundreds of flip-flops in a trancelike ballet. The mechanical installation, titled Sole crushing, promises both cacophony and catharsis. Above, visitors will be able to take in the artist’s longest film thus far, For Aicha. Directed with her longtime co-conspirator, documentary filmmaker Orian Barki, and with the support of animators John Michael Boling and Jason Coombs, the work follows Bouchra, a Moroccan jackal living in New York, as she attempts to make a film about how her queer identity has shaped her relationship with her mother. Here, Bennani and Barki give CULTURED a peek at the film and exhibition’s backstory.

FOR AICHA, THE FILM INCLUDED IN “FOR MY BEST FAMILY,” IS THE LONGEST VIDEO PROJECT YOU’VE EVER WORKED ON. WHAT CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES DID THE EXTENDED FORMAT BRING?

MERIEM BENNANI: When you make a movie over two years, you’ve gone through so many different political and personal moments. You have to sustain some kind of narrative cohesion while going through so much. You also have to maintain spontaneity. The story [is] about a mom and daughter learning to understand each other around queerness. The thing is, it can so easily fall into something so annoying in terms of a coming-out story in the Arab world. People in Western countries, maybe that’s all they ask for—to see how it’s so hard to be Arab and gay. We were scared to fall into that, but at the same time we thought it would be cool to have a fun and emotional lesbian story about this Moroccan filmmaker who lives in New York … What we found as a solution is specificity, which is realizing that maybe it’s a documentary about me and my mom in a way, and it doesn’t matter what it means because it’s so true to us.

ORIAN BARKI: Meriem was like, “I feel that we’re missing the perspective of the parent in the relationship. Maybe I should call my mom and ask about her experience, and we can use that as inspiration.” So she called her mom. They’ve had conversations before about Meriem’s queerness and their relationship, but never like this. After the call, [Meriem] played the recording to me and translated it live.

BENNANI: We were like, “This is better than everything we’ve been trying to write. We have to use it as the spine of the [film].”

BARKI: So we created this meta layer for the story. On one level, it’s about a daughter trying to understand her mother better, to be able to have some type of closure and move on, but on another it’s like, “I need to understand you in order to be able to make this film.”

BENNANI: I was really uncomfortable making a film about myself or bringing my mom into it. She’s always accepted being in my films, but that doesn’t mean she accepted making it about us, especially about the most sensitive part of our relationship. I’m really impressed by her. Giving me this was a mix of love for me, but also an understanding that I need it, which she says in the film. I also want to say that a very important step was to fictionalize things: This is not my mom anymore. It’s re-recorded with Moroccan artist Yto Barrada’s voice. Departing from things in that way allows you to look at it like a story … What Orian and I have in common is we know when something feels true. It’s a balance between a certain tenderness and humor that is not trying to be cool or relevant—it just is. That’s our compass.

BARKI: Sometimes it was just about going on our phones, looking for videos of moments, and then reproducing them in a fictionalized way. The scene in For Aicha where she gets her ear pierced and then puts the sunglasses on to hide her emotions— we have a video of when I got my ear pierced and Meriem made fun of me. She was like, “Are you crying?” You can take those real-life moments and place them in a way that feeds into an emotional arc. That’s another way of keeping this documentary spirit, with these small poetic life moments.

MERIEM, WHAT WAS IT LIKE TO WORK ON SOLE CRUSHING AT THE SAME TIME AS FOR AICHA?

BENNANI: With Sole crushing, it was fun to create an environment that is not telling you a story but that hopefully generates a feeling within you. It’s an overwhelming, loud installation. It is definitely informed by going to protests. It’s about being surrounded by a big group of people [united] around one thing—what that feels like. It’s also about moments of collective catharsis—not necessarily just around politics, but also around musical traditions. It’s more about the essence of living than a specific person’s story.

WHY CHOOSE FLIP-FLOPS AS YOUR PROTAGONISTS?

BENNANI: The Fondazione Prada space is so gorgeous and fancy. It felt like a challenge to be like, “In this insane space, I’m going to work with a flipflop. How can I go from silly to monumental with such an unprecious, bottom-of-the-fashion-chain thing?” That was the initial impulse. Because I wanted to make music with flip-flops, I started researching percussive dances, like tap dance and flamenco. I started getting really into flamenco and duende, [an elevated state of emotion often associated with flamenco]. Duende is anchored in a kind of tragic swag; it doesn’t matter how good you are technically, it just comes out of you. In the way it’s described by [Federico García] Lorca in his text on duende, it comes from the feet. So then I thought about duende with the flip-flops.

YOU’VE WORKED TOGETHER FOR YEARS NOW. DID YOU LEARN ANYTHING NEW ABOUT EACH OTHER THROUGH THIS PROJECT?

BARKI: I work with doubt as a guide, which can be a very annoying thing, but I use it as, like, “Oh, is this good? Is this not good?” Meriem is the complete opposite. We’re able to complete each other in this way where she has an idea and runs with it. And I’m always like, “Wait, I don’t know.”

BENNANI: I’m more visually uptight. I’ll care about more within a scene, and sometimes I can get lost in that. Like, “She can’t be wearing those pants, she already wore them. They need to be blue.” Orian is always looking at the bigger scale. It’s like, “Who cares about if this shot looks good. First, the story needs to work.”

“It’s a balance between a certain tenderness and humor that is not trying to be cool or relevant—it just is. That’s our compass.” —Meriem Bennani

YVONNE WELLS HAS BEEN MAKING QUILTS FROM HER ALABAMA HOME FOR OVER FOUR DECADES. THIS FALL, HER RENEGADE PRACTICE GETS ITS DUE WITH A NEW MONOGRAPH AND TWO EXHIBITIONS.

BY ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

Yvonne Wells was almost 40 when she began quilting. A self-described tomboy turned high school P.E. teacher, she turned to the craft for warmth in the winter of 1979. “I was just making quilts to cover the kids and keep my legs warm by the fire,” the Tuscaloosa native recalls over the phone. She used what was around her —curtains, her children’s clothes, her husband Nathaniel’s pants—to elaborate the spreads she’d seen her own mother make growing up. What she found in quilting went far beyond the quotidian. “Something was burning inside me,” Wells, now 84, remembers. “It made me say, Yvonne, don’t turn this loose. This is something that has to come out.”

The moment when an artist meets their medium—that instant when a compulsion to create finds its vocabulary—is the stuff of biopics and memoirs. But Wells didn’t identify as an artist from the get-go. “I just thought I was somebody making quilts,” she says with a laugh. And quilts she did make: Over the decades, Wells has crafted more than 500 pieces and shown them across the United States, with some of her designs even making their way onto Hallmark cards and the White House Christmas tree. Early on, when she landed on an idea, she’d make it in multiples—three, to be exact, which she identifies with the Holy Trinity. “I believe in God, and I believe in the symbols of God,” she explains. “The first one never said [everything] I wanted to say. The second one didn’t either. By the time I got to the third one, it did.”

Wells’s approach to her subject matter, like to the medium itself, has always been instinctual. Whether she’s depicting biblical scenes, pop culture figures, or civil rights struggles, her visual language is sui generis: Stitches are prominent, colors collide, and shapes warp, giving the impression that the quilts are in perpetual movement. “I can’t draw a straight line,” Wells confesses. “If you look at my quilts, everything is slightly off-center. It’s just the way the fabric flows.”

This September, her off-kilter abstractions will be the focus of a solo show for the first time, at Fort Gansevoort in New York. Because Wells believes in the power of threes, it’s fitting that this milestone is accompanied by two others: the publication of the first monograph devoted to her practice, and a retrospective at the Paul R. Jones Museum in her hometown, on view through Sept. 27. Have these, and the many accolades she’s accumulated throughout the years, changed how she feels about the word artist? “Whatever they call me is what I am,” she concludes. “It doesn’t matter if I’m folk or fine. I just continue to do what I do. My head sees, my heart feels, and my hands create.”

“IT DOESN’T MATTER IF I’M FOLK OR FINE. I JUST CONTINUE TO DO WHAT I DO. MY HEAD SEES, MY HEART FEELS, AND MY HANDS CREATE.”

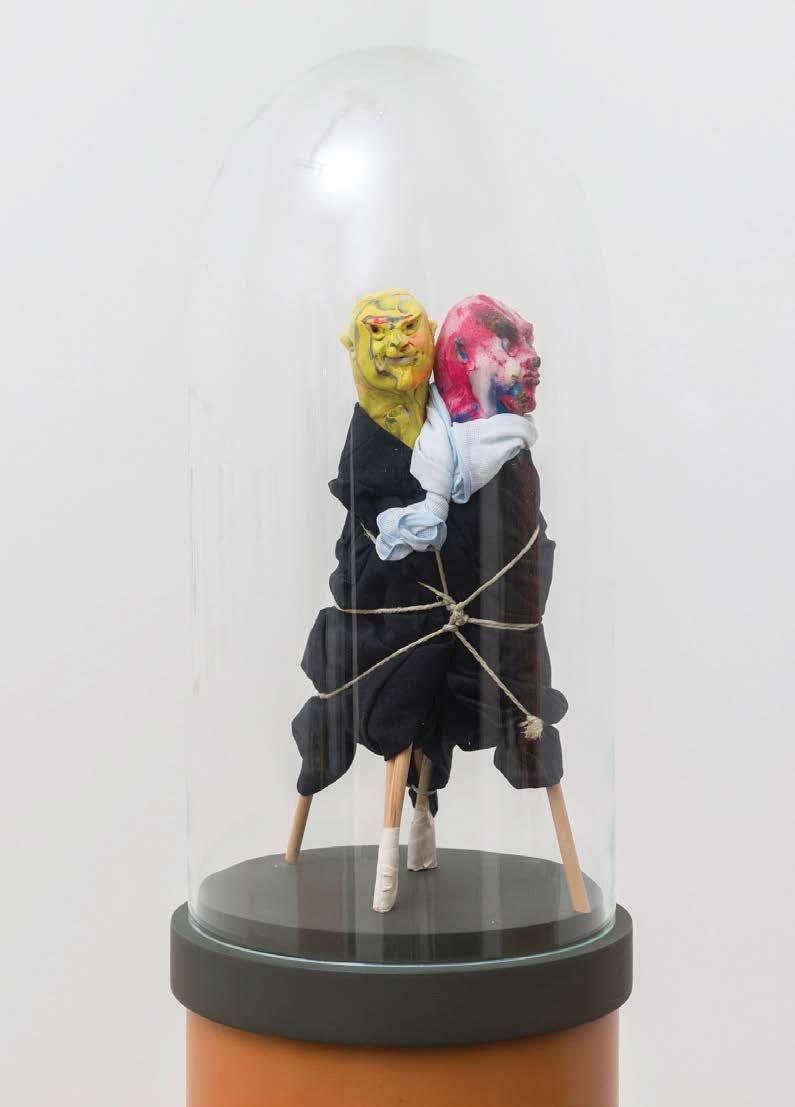

Thomas Schütte hasn’t had a major U.S. museum exhibition in over two decades, but the category-defying creative’s influence looms large. A new MoMA show is setting out to prove it.

By Rebecca Goodman

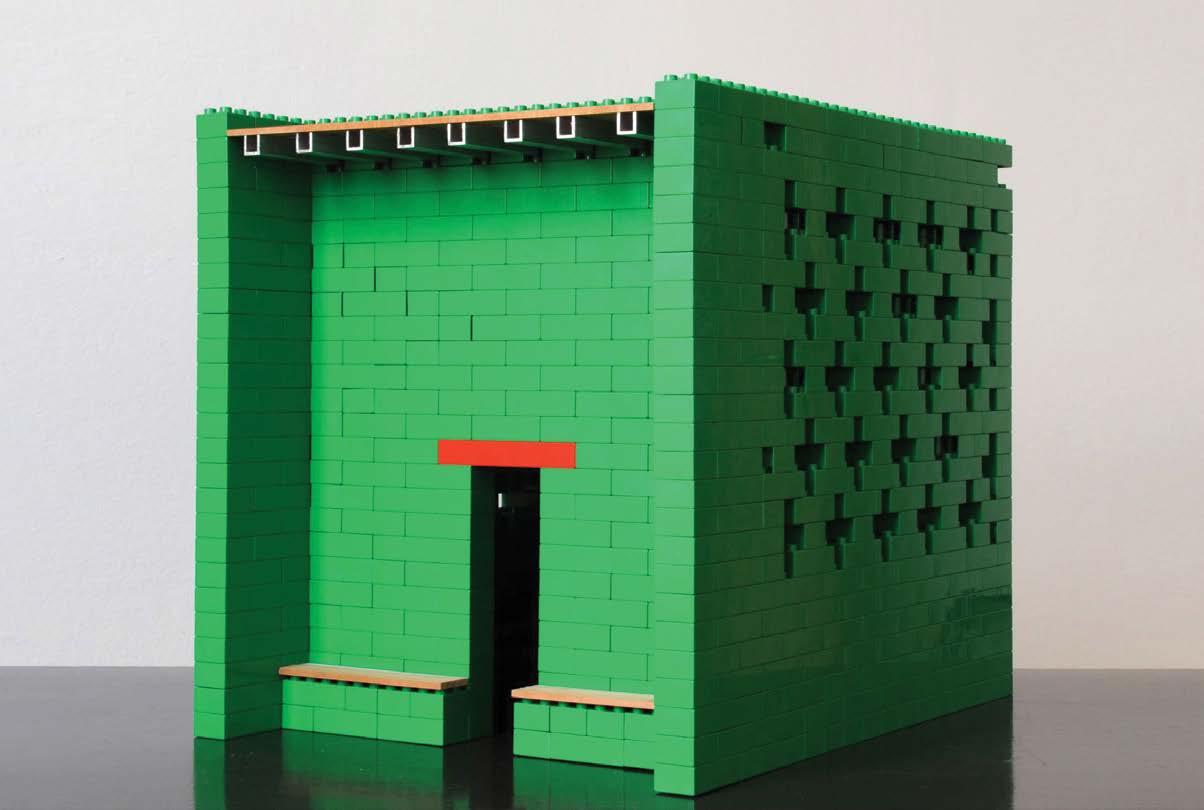

“He finds relevance in the least expected places,” says curator Paulina Pobocha of Thomas Schütte. “A Pringles potato chip balanced on a matchbook serves as a prototype for a museum … a diminutive, gnarled and grimacing figure becomes the embodiment of authoritarianism.” This fall, that very ingenuity is at the heart of a splashy retrospective of Schütte’s work that Pobocha organized at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The eponymous show, which runs from Sept. 29 through Jan. 18, 2025, will be Schütte’s first survey at a U.S. museum in over two decades. “The exhibition marks 50 years of his practice,” continues Pobocha. “Schütte’s work is topical but not reactive: Its urgency is compelling and broad, existing in time and outside of it.”

The Oldenburg native, now 69, came up alongside fellow German artists, like Katharina Fritsch and Isa Genzken, who were interested in pushing the zeitgeist away from the reigning minimalism and toward a more textured iconography. Even among this eminent group of artists, Schütte’s approach remains singular and allergic to categorization. “With ease, he moves from the foundry to the ceramic studio,” Pobocha muses. “One day he can be drafting plans for an imagined building, and the next, painting flowers or tomatoes in ink and watercolor.”

The elastic nature of Schütte’s oeuvre is emphasized in the show’s curation, which slaloms between the artist’s watercolor, drawing, print-making, architectural, and sculptural practices. Connoisseurs may have seen examples of the latter making rounds on the art-fair circuit in recent years—bulbous, often grotesque figures molded out of ceramic, wax, or bronze that evoke a modern-day Honoré Daumier.

“He has given us so much to see, so much to consider,” says Pobocha, “with regard to art-making, but more importantly in how we, collectively, relate to the world, each other, and ourselves.”

By Jayne O’Dwyer

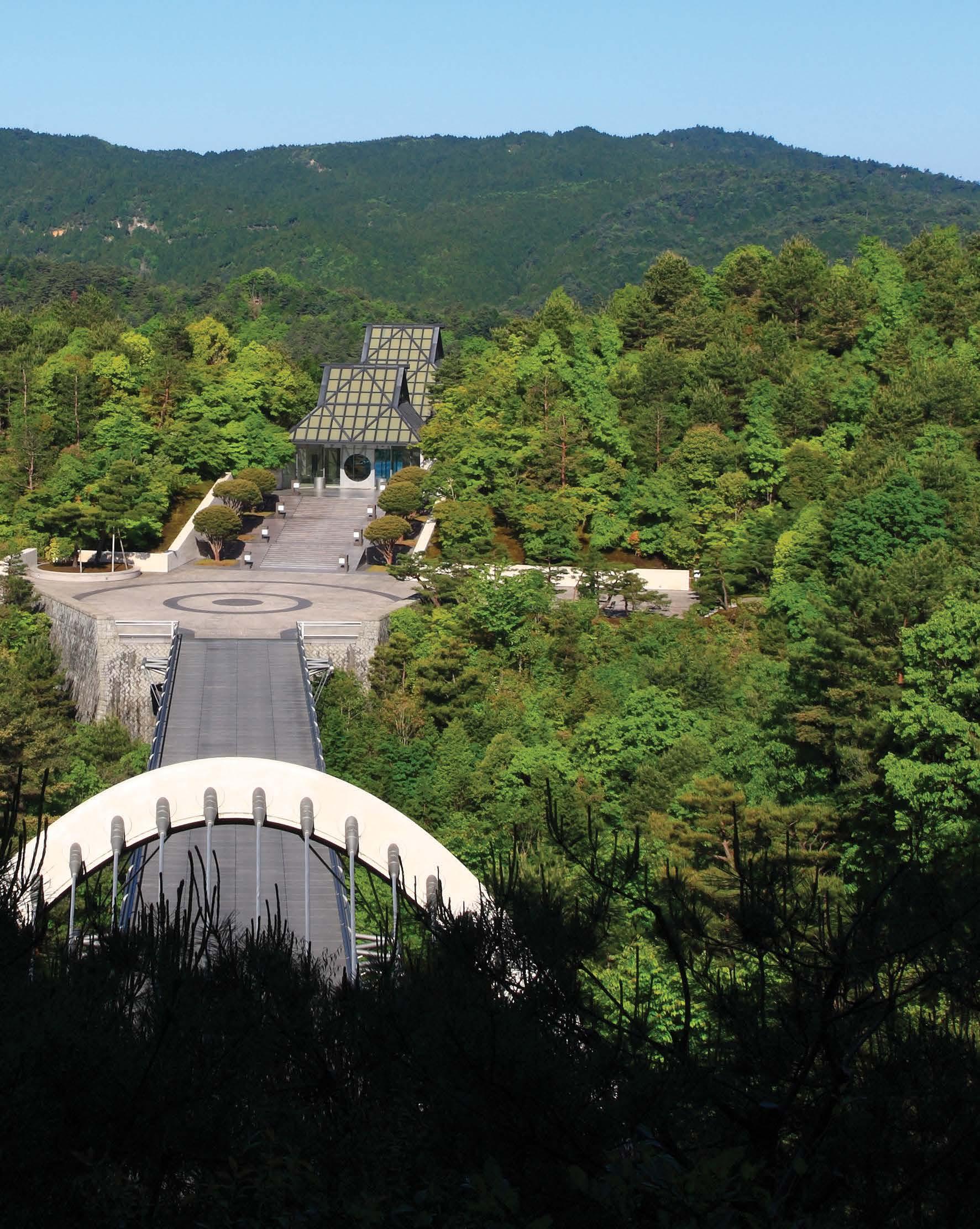

JOSÉ ESPARZA CHONG CUY AND GUILLERMO RUIZ DE TERESA WERE ARCHITECTURE STUDENTS IN GUADALAJARA WHEN THEY FIRST HEARD OF THE STOREFRONT FOR ART AND ARCHITECTURE. NOW, THEY’RE STEERING THE NEW YORK INSTITUTION TOWARD ITS NEXT CHAPTER.

For José Esparza Chong Cuy and Guillermo Ruiz de Teresa, the Storefront for Art and Architecture loomed large in their imaginations well before they began their tenures at the New York institution. “In college, we were asked to draw the building as an exercise,” remembers Chong Cuy. The 1993 installation—which tapped artist Vito Acconci and architect Steven Holl to reenvision Storefront’s Nolita facade— won the admiration of the two architecture students from Guadalajara. Now, the duo is at the helm of the pioneering organization. As executive director and chief curator, Chong Cuy prides himself on thinking big picture about Storefront’s legacy, while Deputy Director and Curator Ruiz de Teresa considers himself the more pragmatic one. “I’m more focused on how things will take place, and José is always leading the charge in what things could be,” he explains.

This year, that complementary dynamic has been put to work—and rewarded—with “Swamplands,” a year-long series of research,

exhibitions, and programming that centers “the ethical and technical entanglements of water.” When we speak—with Chong Cuy calling from Mallorca and Ruiz de Teresa from a small town in Central Mexico—London-based artist Imani Jacqueline Brown’s “Gulf” (or “Strike Gulf”) is on view in New York, and they are reviewing the over 200 applications they received for an open-call exhibition next January.

These milestones were born of an immersive period of preparation. Before “Swamplands” came to be, the pair held a four-day “Swamp Summit” on the Yucatán peninsula with the entirety of the Storefront team, featured artists (including Gala Porras-Kim and Fred SchmidtArenales), and a few special guests. “We invited a physicist that had been working on the coast of the Yucatán,” Ruiz de Teresa says, “and through conversations with Imani, the physicist connected her to the archives of a university in Mexico that has core samples from the 1960s,” which had a direct impact on

the artist’s work and exhibition centered on the “geographies of oil and gas.”

The duo hope to foster connections like these within the organization and beyond. “Storefront was never really about the square footage,” asserts Chong Cuy. “The gallery has always been an excuse to gather.” As they continue to consolidate their program, the pair are also looking outside New York. After its current run, “Swamplands” will become a touring group exhibition, starting at the Graham Foundation in Chicago. Storefront also recently announced the creation of the Kyong Park Prize, an unrestricted $25,000 award to be bestowed on an individual or collective working at the intersection of art, architecture, and politics.

Despite many irons in the fire that draw the duo’s attention elsewhere, a commitment to securing Storefront’s future in New York takes precedent. “Let’s buy the building,” Chong Cuy exclaims. “Let’s manifest.”

FOLLOWING HER INCLUSION IN THE 2024 WHITNEY BIENNIAL AND A KNOCKOUT SOLO SHOW AT KARMA IN NEW YORK, THE NEW MEXICO–BASED ARTIST IS BRINGING HER ETHEREAL PAINTINGS TO BERLIN.

By John Vincler

Maja Ruznic paints worlds of feeling. To describe her work as straddling abstraction and figuration, which critics often do, is to neglect her inventiveness. Rather than existing between two states, Ruznic creates an alternate one, simultaneously recognizable and uncanny. Hers is an emotionally charged dreamworld made material, which, rather than dissolving with your attention as a dream might upon waking, only grows more engaging, complex, and inhabitable the longer you look.

When we met this summer, Ruznic was showing at three venues in New York. She had just returned home to New Mexico after opening her solo show, “The World Doesn’t End,” across two of Karma’s East Village spaces. She was one of only a few painters featured in the 2024 Whitney Biennial and was also included in the group exhibition “Mother Lode: Material and Memory” at James Cohan in New York. We talked as she prepared for her first solo in Berlin, at Contemporary Fine Arts this fall.

Writers have the phrase “speculative fiction” to describe works that envision fantastical or imaginative realms, a genre that includes everything from fairy tales to magical realism. In her paintings, Ruznic conjures her own distinctive universe, including a set of recurring characters. (She keeps separate notebooks to chronicle a core group of four of them, she tells me, reaching for a notebook at the end of her work bench.)

Ruznic’s figures combine the patterned geometry of Gustav Klimt and the surreal physiology of Leonora Carrington, all while emerging from a Rothko-like vapor of Color Field painting. While her works seem to synthesize a century and a half of art history, there is nothing academic about them.

As a child, Ruznic fled Bosnia and the genocide that began there in 1992, living for three years in refugee camps before arriving in the United States. “I’ve often thought the imaginative space that feels so comfortable to me, came to me from trauma,” the artist says. At age 9, in an Austrian refugee camp, she remembers being given a set of watercolors, as well as a red lamp that a doctor told her would treat depression. Painting, and the use of color, became a way of both exploring and representing her emotions. “I feel like I really lucked out in that … to deal with the trauma, I became obsessed with creating worlds,” she says.

While Ruznic’s narrative arc—from fleeing war as a child to becoming an artist in the United States —is a compelling one, it would be a mistake to reduce her achievements to a trauma plot.

I first encountered Ruznic’s paintings at Karma in 2022. Her suite of large canvases captured the sleepwalking state of early parenthood, of being up in the middle of the night and exhausted during the day. Dominated by somber purples and greens with flashes of red and yellow, the pictures told a nonlinear story of a mother, a father, and a child—all shot through with tenderness and just a dash of

horror. It was one of the most affecting shows I’d see all year.

In more recent canvases, Ruznic has pushed the boundaries of her visual language, creating austere and concentrated Color Field works and complex compositions of multiple figures. Take the Pietà-like central figure of Arrival of Wild Gods II, 2023, with an attending crowd of maybe-human figures framing the scene in ethereal yellow. The Berlin show, titled “Mutter”—a play on the German word for “mother” as well as for the English word for a barely audible utterance—will feature The Beginning/The End, 2023/24, with rhythmic tufts of red oil overtaking a cloud of purple on linen. Ruznic confesses that, for her, the stripped-down expanses of color are more difficult, more taxing. She can suggest a story with the figures, but in the unpopulated (or barely populated) fields of color, she intends to precisely render an intense feeling.

While the artist has never been more in demand, she seemed happy to be back in her studio in New Mexico, where she moved in 2017. Surrounded by desert and mountains and away from the competition and bustle of urban art-world centers, she’s been able to push her work further and on her own terms. “Being here,” she says, “has just expanded everything.”

Maya Ruznic, The Beginning/The End, 2023-24.

October 18 - 20, 2024

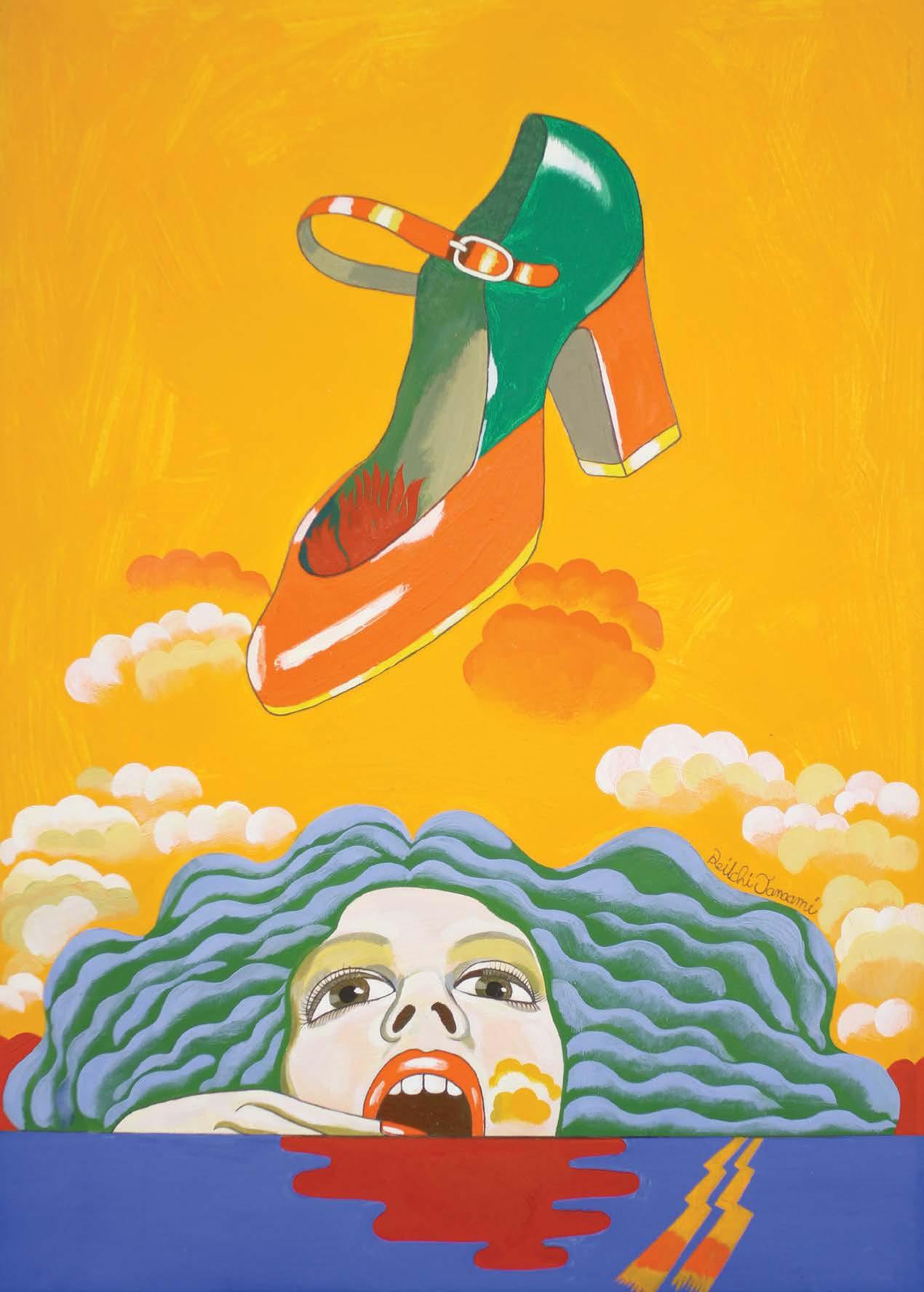

TO MARK THEIR INCLUSION IN PHAIDON’S GREAT WOMEN SCULPTORS, THE TWO ARTISTS MEET—FOR THE FIRST TIME— TO UNPACK THE EBBS AND FLOWS OF THEIR PARALLEL PRACTICES AND WHAT THEY TREASURE ABOUT THEM.

OVER TWO AND THREE DECADES, RESPECTIVELY, ANTHEA HAMILTON AND SYLVIE FLEURY HAVE EXPLORED THE AESTHETIC COLLATERAL OF CONSUMER CULTURE IN THEIR ARTISTIC PRACTICES. BORN AND BASED IN LONDON, HAMILTON’S UNCANNY INSTALLATIONS AND PERFORMANCES PROBE “THE EXPERIENCE OF STUFF,” AS SHE’S PUT IT IN THE PAST. SWISS NATIVE FLEURY’S FASCINATION WITH THE MATERIAL FETISHES OF MODERN LIFE CAN BE TRACED BACK TO HER EARLIEST READYMADES IN THE ’90S; SHE’S PLAYFULLY POKED AT THE ART WORLD’S HIERARCHIES EVER SINCE. HERE, THE TWO ARTISTS—BOTH INCLUDED IN PHAIDON’S MONUMENTAL NEW TOME GREAT WOMEN SCULPTORS CONNECT TO TALK FASHION, FANTASY, AND NEVER WANTING TO FINISH.

SYLVIE FLEURY: I love being called a sculptor because, like many artists today, I don’t sculpt.