Jane Holzer, Muse & Philanthropist

Simply One of a Kind

Simply One of a Kind

Simply One of a Kind

Jane Holzer, Muse & Philanthropist

Simply One of a Kind

Simply One of a Kind

Simply One of a Kind

DECEMBER 2 - 8

MUSEUMS & GALLERIES

Winter 2024

80 82 84 86 88 90

96

“COULD YOU WRITE WHAT YOU WRITE IF YOU WEREN’T SO TINY?”

In 2021, Lili Anolik discovered never-before-seen correspondence between Eve Babitz and Joan Didion. The epistolary trove is the subject of her gripping new book.

ANDRÉ HOLLAND DIGS IN

The actor reflects on the intensity of the process behind his latest film, Exhibiting Forgiveness, and his increasing involvement in the art world.

WITH NICKEL BOYS, RAMELL ROSS EXCAVATES SOUTHERN WOUNDS

The director adapted Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer-winning novel into an experimental portrait of life in the Jim Crow South.

SIMON KIM’S BANNER YEAR

The mastermind behind Cote and Cocodaq lifts the curtain on his rambunctious hospitality brand’s inner workings.

CHARLES ATLAS MAPS HIS LIFE AND WORK

“About Time,” the title of the artist’s first career retrospective at the ICA Boston, is both a joke and completely serious.

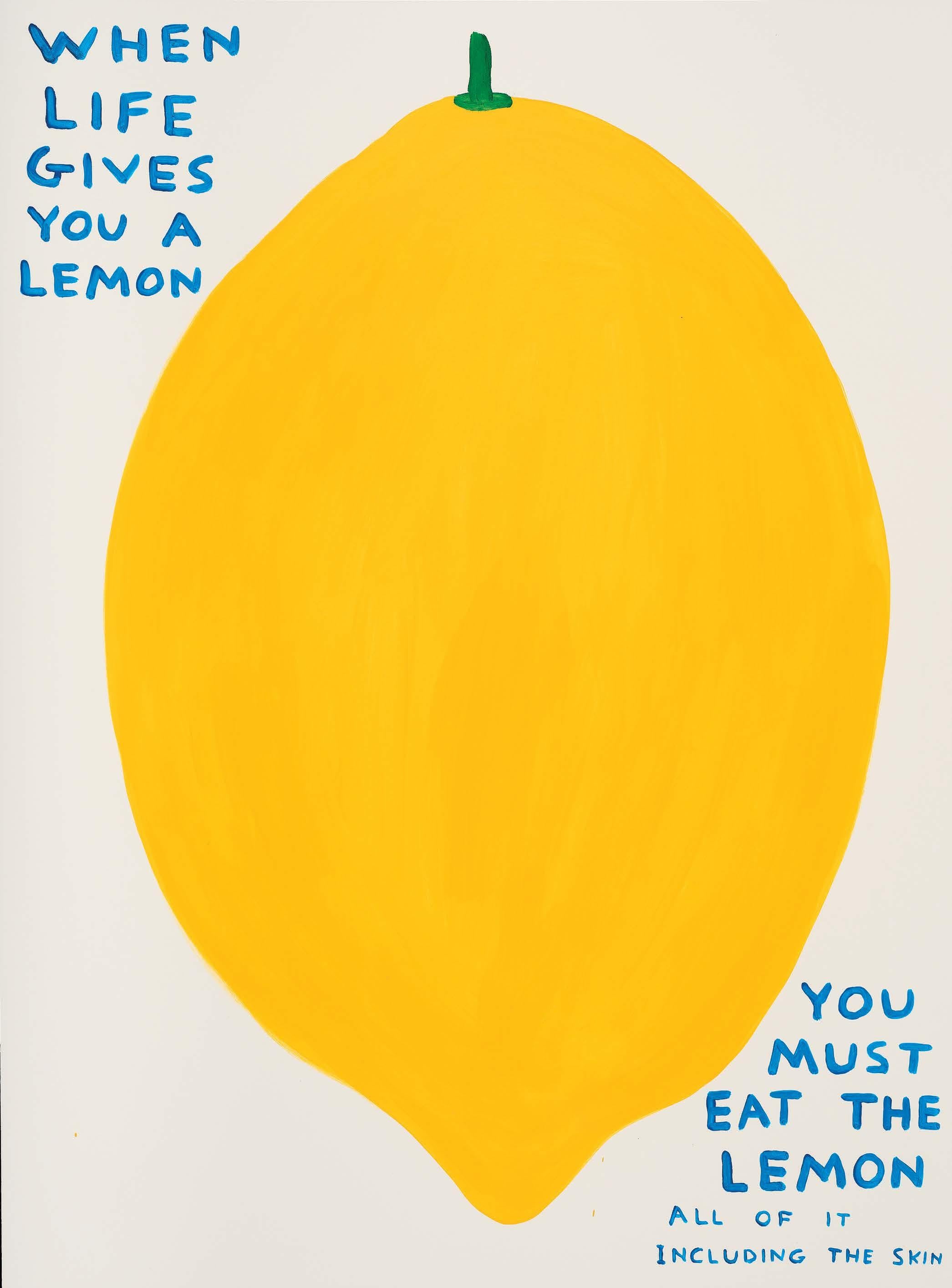

SUNA FUJITA GOES DEEP

For their most otherworldly collaboration yet, Loewe and the Japanese studio plumbed the depths of sea and sky.

THE CROWD PLEASER

While his films break box office records, Shawn Levy is quietly laying the groundwork for a second passion: collecting.

102

AN INSTANT CLASSIC Alessandro

100 FOR MIU MIU, ONE FILMMAKER WANDERS THE PAMPAS Laura Citarella joins an all-star list of filmmakers for Miu Miu’s Women’s Tales initiative.

Michele’s first Valentino Garavani collection marks the beginning of a new era.

104

106

HEJI SHIN TAKES OFF For her first institutional solo exhibition in the U.S., the provocative photographer looked to the skies.

THE NEXT ART-WORLD WATERING HOLE OPENS ITS DOORS At Clemente Bar, a new space by painter Francesco Clemente and chef Daniel Humm, revelry is as important as craft.

108

JUST KEEP PAINTING At 87, Loretta Dunkelman is embarking on the latest chapter of her career at Polina Berlin Gallery.

114 110 112

116

GIORGIO ARMANI TRANSFORMS A MILANESE PALAZZO INTO A TEMPLE FOR GLOBAL DESIGN The designer’s latest furniture collection is a love letter to travel, craft, and film.

MARGUERITE HUMEAU’S AIRBORNE ERA

The artist is bringing a speculative slate of new work to the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami—one that imagines an alternate evolution of humanity.

REMEMBERING GARY INDIANA—A BEGRUDGING ICON

Following the cult writer’s passing, our critic recalls his bitchy radicalism, wild prose, and uncensored takes on the art world.

THE BASS LOOKS AHEAD

As it turns 60, Miami Beach’s storied Bass Museum of Art gears up for yet another growth spurt.

120

128

134

138

142

THE CROWN PRINCE OF CANAL STREET As he prepares to relaunch the legendary artist-run restaurant Food, Lucien Smith shares some of his culinary predilections.

A FIELD GUIDE TO DATING IN THE ART WORLD Industry veterans and newcomers share their rules of thumb for dating—and breaking up—in the art world.

JOAN SNYDER’S SECOND COMING

As the 84-year-old artist prepares for her first show with Thaddaeus Ropac in London this winter, she’s nowhere close to slowing down.

FROM BRUTALISM TO THE BAHAMAS

This collector’s Baker’s Bay home provides a stunning backdrop for her creative passions— many of which were sparked in childhood.

NEW YORK, I LOVE YOU

Photographer Deon Hinton captures a crosssection of young creatives leaving their mark on the shape-shifting metropolis.

152

154

THE MAKING OF A MEMORY

MACHINE Jaeger-LeCoultre tapped French perfumer Nicolas Bonneville to create three fragrances that embody the Swiss watchmaker’s legacy.

DESIGN. DEFINE. THEN DISAPPEAR. Lucifer Lighting has been illuminating culture for decades—lighting everything from history museums to Cartier’s glass vitrines.

Winter 2024

THE THINGS WE CARRY

262 272 238 248 256

158

166

VENUS WILLIAMS AND TITUS KAPHAR RECTIFY A MISSED CONNECTION After a recent jaunt through the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Venus Williams sits down with Titus Kaphar for a long-overdue conversation.

FOR NJIDEKA AKUNYILI CROSBY AND MALCOLM WASHINGTON, ART LIVES IN THE BONES The painter and filmmaker met to discuss what it takes to make a work of art that stops you in your tracks.

174

184

216

228

JON BATISTE AND AMY SHERALD ENTER THEIR FLOW STATES The pair met for a conversation about their respective journeys to the concert hall and gallery floor.

YOUNG ARTISTS 2024 The 30 artists on CULTURED ’s ninth annual Young Artists list make work that is bursting with idiosyncrasy, curiosity, and gumption.

DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE Photographer and acrobat Isabelle Wenzel juxtaposes Chanel’s delicate silhouettes with her signature contortions.

GUCCI STARTS A HEAT WAVE

Photographer Clay Stephen Gardner captures the brand’s 2025 Cruise collection in all of its intensity, amidst the bucolic-yeturban landscapes of New York.

Some objects are ephemeral. Others last longer than their keepers. CULTURED offers an array of pieces primed for this extraordinary destiny.

IF YOU KNOW, YOU KNOW

A century into its story, Loro Piana’s brand of finely crafted, understated essentials is more timely than ever.

THINGS YOU WANT TO LIVE WITH, FOR THE LIFE YOU WANT TO LIVE

In design studio APPARATUS’s latest project, photographers Matthew Placek and Dina Litovsky found distinct inspiration on the same well-lit set.

THE ARTIST’S HAND

Four of Dior’s chosen creatives unpack what went into their take on a timeless accessory: the Lady Dior handbag.

A WALK ON THE WILD SIDE

Actor Deepika Padukone, the face of Cartier’s Nature Sauvage, unpacks the heat and heart behind the collection’s modern heirlooms.

Our last issue of the year was assembled during unusual times: following yet another “hottest summer on record,” we barrelled forward into an uncertain fall right alongside our readers. As we all know, it’s moments like these when the creatives amongst us are needed most—not just to offer an escape, but to craft a mirror of our moment, a historical record of what we’ve experienced together.

But the artists in our lives need support, too. Our Winter issue’s Young Artists list features 30 emerging talents who are chronicling our moment while navigating a culture that is often hostile to creativity. I began the annual list nine years ago, after spending countless hours visiting the studios of fledgling artists. I saw time and again how the forces of daily life both inspired these talents and prevented them from flourishing. This year, I was thrilled to announce that MZ Wallace will be providing one of the honorees in these pages with an unrestricted $30,000 grant. It will mark the second year that the list will provide not only recognition, but also meaningful financial support.

The issue also celebrates what we at CULTURED hope will be the rebirth of art criticism. More than a decade ago, critic Deborah Solomon estimated that there were fewer than 10 full-time art critics at major newspapers in the United States. Since then, that number seems to have dwindled further, but the number of artists making important work has not. That’s why, this fall, I launched the Critics’ Table—with co-chief art critics Johanna Fateman and John Vincler—a subscribers-only column that will offer a refuge for criticism and its most intrepid voices.

These pages are also home to the first installment of our cover-spanning Artists on Artists series, which invites luminaries across disciplines to sit down for conversations as diverse as their outputs. In one, the tennis

star, entrepreneur, and art collector Venus Williams joins artist and filmmaker Titus Kaphar to compare notes on venturing into new mediums. “People can put you in a box,” Williams says. “It’s so important to come at them with authenticity, really actually know what you’re doing, and just keep hauling away.” In another, filmmaker Malcolm Washington and artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby dissect one another’s work for clues to their personal histories. For our third cover story, painter Amy Sherald and musician Jon Batiste discuss their respective journeys to the gallery floor and concert stage. “I love it when things don’t work,” Sherald tells Batiste. “It leaves room for something else to happen next.”

Join us in supporting these trailblazing creatives.

Sarah G. Harrelson Founder and Editor-in-Chief @sarahgharrelson | @cultured_mag

JUSTIN FRENCH Photographer

“Venus Williams has such refreshing vitality; it is encouraging and provides an opportunity to develop imagery that is emotive, honest, and exciting,” says Justin French, who photographed the multihyphenate powerhouse for one of the issue’s cover stories. “I enjoyed working with her on this project.” The two convened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for a shoot that meandered through the institution’s legendary collections. Outside of his contributions to CULTURED, French has worked with the likes of Vogue, Netflix, and Nike to show a new side of our culture’s best-known figures through his highly saturated approach to portraiture. At the heart of his practice is a thirst to encapsulate the full range of human emotions in a single still.

“Venus Williams has such refreshing vitality.”

Stylist

Jessica Willis’s on-set work doesn’t often include balloons and rabbits—but when it does, she rises to the occasion. “When we first discussed creative direction, Lucien said, ‘Let’s have fun’—and we really did!” she says, referring to the shoot with artist Lucien Smith featured in the pages of this issue. “We drew inspiration from the whimsy of Charlie Chaplin and the bold spirit of Gordon Matta-Clark. In response, I styled him in expressive looks from Marni, Marc Jacobs, Bottega Veneta, and Balenciaga.” Elsewhere, Willis has teamed up with photographers like Campbell Addy and Nadia Lee Cohen for editorials appearing in Vogue, The Cut, The Wall Street Journal, and more, as well as for brands like Tiffany & Co. and Jil Sander.

ESTHER ZUCKERMAN Writer

Most know Shawn Levy for his blockbuster hits, including this summer’s Deadpool & Wolverine. For this issue, writer Esther Zuckerman explored one of the decorated director’s lesser-known passions: art collecting. “Shawn’s enthusiasm for his work in film and his art collection was palpable as soon as I walked through the door of his Lower Manhattan apartment,” she recalls. “I tried to capture that in this piece.” Zuckerman’s work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and GQ, and she’s the author of three books: Falling in Love at the Movies, Beyond the Best Dressed, and A Field Guide to Internet Boyfriends.

“Shawn Levy’s enthusiasm for his work in film and his art collection was palpable as soon as I walked through the door of his Lower Manhattan apartment.”

—Esther Zuckerman

RACHEL CORBETT Writer

“I’m always trying to understand how artists become who they become and make what they make,” says Rachel Corbett, who profiled 2024 Young Artists Emil Sands, Olivia Vigo, Qualeasha Wood, and Faye Wei Wei for this issue. “The Young Artists list is a fun reversal of that process, allowing us to observe the

TITUS KAPHAR Artist

After many a missed connection over the years, Titus Kaphar and Venus Williams were overdue to meet one another. So when CULTURED asked the pair to carve out time in their crazed schedules, it was a no-brainer for Kaphar. “It was such an honor to sit down and chat with Venus about art, design, and producing an autobiographical film,” says the painter. “It was surprising to discover that, despite our very different professions, we experienced similar challenges when it came to adding an entirely new medium to our repertoire.” The pair discussed their forays into film and design for the issue’s Artists on Artists series, which asks creatives across disciplines to discuss the drive at the core of their practices.

“It was surprising to discover that, despite our very different professions, Venus Williams and I experienced similar challenges when it came to adding an entirely new medium to our repertoire.”

—Titus Kaphar

creative process in its early stages and, hopefully, follow it for years to come.” Corbett has also written for New York magazine and The New York Times Magazine, and is the author of You Must Change Your Life: The Story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin

DANA SCRUGGS Photographer

Shooting one great cover is a feat. For this issue, Dana Scruggs was asked to shoot two. For CULTURED’s Artists on Artists series, the photographer was tasked with capturing artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby and filmmaker Malcolm Washington, as well as Jon Batiste and Amy Sherald—two distinct sets of creatives whose budding connections flourished before her lens. Each pair spent an afternoon with Scruggs, during which the photographer’s meticulous posing and quiet, confident demeanor yielded some of the issue’s most enduring images.

JEREMY LIEBMAN Photographer

Jeremy Liebman has photographed figures from the worlds of art, politics, and design, ranging from Vladimir Putin to John Waters, for publications such as Apartamento, Pin-Up, and The New Yorker. His work has additionally been commissioned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Apple, and Bottega Veneta. For this issue, CULTURED sent him to the Bahamas.

There, he delved into the art-filled home of collector Ivana Berendika. “The trip to Ivana’s home in Baker’s Bay required two flights, a car, a speedboat, and a golf cart,” he recollects. Once he landed in New York, the photographer headed to Chinatown (which only required one train) to shoot artist Lucien Smith—a whimsical romp featuring Charlie Chaplin–esque theatrics.

Photographer

On a rainy day in New York, Deon Hinton climbed onto a chair in a rooftop garden, film camera in hand, to capture a coterie of the city’s creatives. “Photographing artists who also belong to communities that drive New York culture and art truly was such a beautiful experience,” he says of the portfolio he shot for this issue. “To be an artist in New York does not look one specific way, but I believe a similar heart is shared amongst us all.” Outside of his editorial work, the 2023 CULTURED Young Photographers List alum has collaborated with the likes of Fendi, Gucci, and Calvin Klein while producing a slate of personal projects, documenting his community and himself in the tenderest of moments.

Writer

For CULTURED, Rabkin Prize–winning writer Travis Diehl has chased down the artistic collateral of anxiety, Peter and Sally Saul’s secrets to a lifelong creative practice, and Derek Fordjour’s historical dive into the world of Black magicians. Now, he’s turned his critical eye—which has been featured in The New York Times, The Baffler, and X-TRA—onto three emerging talents for the magazine’s annual Young Artists List: Louis Osmosis, Catalina Ouyang, and Paige K. B. “Stepping into an artist’s studio is like visiting their brain,” he muses. “You can talk about ideas but also process, materials, other artists. Whatever’s in the air.”

“Photographing artists who also belong to communities that drive New York culture and art truly was such a beautiful experience. To be an artist in New York does not look one specific way, but I believe a similar heart is shared amongst us all.”

—Deon Hinton

On View Through Jan 05, 2025

SARAH G. HARRELSON Founder, Editor-in-Chief

MARA VEITCH Executive Editor

JOHN VINCLER Co-Chief Art Critic and Consulting Editor

ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT Senior Editor

SOPHIA COHEN Arts Editor-at-Large

DELIA CAI Culture Writer

JACOBA URIST New York Arts Editor

KAREN WONG Contributing Architecture Editor

COLIN KING Design Editor-at-Large

ALEXANDRA CRONAN

KATE FOLEY Fashion Directors-at-Large

GEORGINA COHEN European Contributor

NICOLAIA RIPS

CAT DAWSON

DEVAN DÍAZ

ADAM ELI

ARTHUR LUBOW

HARMONY HOLIDAY

GEOFFREY MAK

LAURA MAY TODD

EMMA LEIGH MACDONALD

LIANA SATENSTEIN Writers-at-Large

JULIA HALPERIN Editor-at-Large

JOHANNA FATEMAN Co-Chief Art Critic and Commissioning Editor

ALI PEW Fashion Editor-at-Large

JASON BOLDEN Style Editor-at-Large

SOPHIE LEE Associate Digital Editor

TOM MACKLIN Casting Director

EVELINE CHAO Senior Copy Editor

SIMON RENGGLI

CHAD POWELL Art Directors

HANNAH TACHER Junior Art Director

CAROL SMITH Strategic Advisor

EMILY DOUGHERTY

DOMINIQUE CLAYTON

RACHEL CORBETT

KAT HERRIMAN

JOHN ORTVED

SARA ROFFINO

YASHUA SIMMONS Contributing Editors

LEXI GLUCK

KATHARINE LEE

KATIE KERN

NICOLE HUR

ZACH BERNSTEN

GRACE WAICHLER

GIULIANA BRIDA

MIA GOULD

MORGAN DESFOSSES Interns

CARL KIESEL Vice President, Chief Revenue Officer

LORI WARRINER Vice President of Sales, Art + Fashion

DESMOND SMALLEY Director of Brand Partnerships

SOPHIA FRANCHI Marketing Coordinator

CARLO FIORUCCI Italian Representative, Design

ETHAN ELKINS

DADA GOLDBERG Public Relations

AMANDA GILLENTINE Marketing and Partnerships Consultant

PETE JACATY & ASSOCIATES Prepress/Print Production

BERT MOO-YOUNG Senior Photo Retoucher

JOSÉ A. ALVARADO JR.

SEAN DAVIDSON

SOPHIE ELGORT

ADAM FRIEDLANDER

JULIE GOLDSTONE

WILLIAM JESS LAIRD

GILLIAN LAUB

YOSHIHIRO MAKINO

LEE MARY MANNING

BJÖRN WALLANDER

BRAD TORCHIA Contributing Photographers

Alexander McQueen · Alexander Wang · Alaia · Amiri · Audemars Piguet · Balenciaga · Balmain · Berluti · Bottega Veneta · Breitling

Bvlgari · Canada Goose · Cartier · Celine · Courrèges · David Yurman · Dior · Fendi · Gentle Monster · Giorgio Armani · Givenchy Graff · Gucci · Hermès · IWC · Jacques Marie Mage · Jil Sander · Lanvin · Loewe · Loro Piana · Louis Vuitton · Maison Margiela Marni · Missoni · Moncler · Moynat · Palm Angels · Patek Philippe · Porsche Design · Prada · Ralph Lauren · Rimowa · Roger Dubuis

Rolex | Tourneau Bucherer · Saint Laurent · Stella McCartney · Tag Heuer · The Webster · Thom Browne · Valentino · Versace · Zegna Bloomingdale’s · Nordstrom · Saks Fifth Avenue partial listing

Valet Parking · Personal Stylist Program · Gift Cards · Concierge Services

“COULD

WEREN’T SO TINY?”

In 2021, Lili Anolik discovered the correspondence of two of Los Angeles’s literary titans: Eve Babitz and Joan Didion. The revelations they sparked are the subject of the writer’s gripping new book.

By Mara Veitch

“I’d already been at it with Eve Babitz for 10 years,” says writer Lili Anolik when asked about the origins of her latest book. “We’d spent hundreds of hours talking—literally hundreds.”

Anolik’s relationship with the late patron saint of 1970s Los Angeles began like many relationships between writers and their subjects: with a barrage of letters and calls, and Anolik hoping that Babitz would eventually bite. A profile ensued, and a book—Hollywood’s Eve—followed in 2019. Anolik’s biography of Babitz is credited in part with the resurgence of interest in the author’s wry, hedonistic oeuvre, giving her long-overdue flowers as a chronicler of Los Angeles’s unforgiving yet irresistible draw. Anolik didn’t think she’d write another one.

Yet after Babitz died in 2021, Anolik discovered that “Eve, who I thought I knew so well, I didn’t know at all.” While sifting through the detritus of Babitz’s life, Anolik discovered boxes full of journals, artworks, and letters—including several to Joan Didion, her fellow iconic literary Angeleno.

That trove became the subject of the writer’s latest book: Didion & Babitz. Of the countless revelations embedded in the letters—many of which offer a riveting glimpse behind the impenetrable saucer-sized sunglasses at a more vulnerable Didion—one scrawled line written in 1972 sticks in Anolik’s mind: “Could you write what you write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan?”

Anolik pored over the correspondence, plumbing the depths of the pair’s fraught relationship and profound rivalry. “It took my breath away,” the writer recalls. “Joan versus Eve is bigger than Joan and Eve—the conflict between them is universal.”

The book offers fresh insights into two of America’s most iconic wordsmiths, yes, but for Anolik, it’s almost a referendum on the creative life—one’s free-spirited, danger-courting joie de vivre clashing against the other’s icy, voluminous intellect. “I hope [readers] come away with the sense that they’ve just finished the nonfiction version of My Brilliant Friend,” Anolik jokes. “And also that all women are one or the other—a Joan or an Eve.”

The decorated actor is no stranger to stepping into a character’s shoes. His latest turn—in artist Titus Kaphar’s debut feature Exhibiting Forgiveness—required an entirely new approach.

By Mara Veitch

In April of 2023, André Holland embarked on what would become a three-month-long routine: a daily commute from his home in New York to Titus Kaphar’s New Haven, Connecticut, studio to learn how to paint.

Even for Holland, a veteran performer who enters a period of deep research for every role he plays, this was a new level of immersion. Kaphar, a MacArthur “genius grant”–winning painter, was developing a feature film—his first—that would excavate the scar tissue of his relationship with his estranged father. Kaphar wanted Holland to play him, so he had to know how to paint.

“We would always talk about ‘the line,’” Holland recalls of those months of preparation. “Bad painting in movies is one of Titus’s pet peeves. He would tell me, ‘Choose a line and then make a confident stroke.’” While they worked, the pair dove deep: Kaphar unspooled memories of childhood and fatherhood, and reflected on his foray into a fickle art world. As they grew closer, the Bessemer, Alabama–born actor learned how to embody the weight of those experiences onscreen.

Holland and Kaphar poured all those months

in the studio into Exhibiting Forgiveness. The project, a true labor of love, has won and broken hearts across the film festival circuit. Here, Holland reflects on the intensity of the process and his increasing involvement in the art world.

How did you and Titus Kaphar build the rapport needed to bring this film to life? When we met, we spent a lot of time talking about art—more than the script or anything else. We ended up spending three months together painting, and that’s how we became friends. Of course, as we’re working, I’m asking him questions about his dad, about his family, and what it’s like to be a father.

Was the physical act of painting like a doorway to deeper conversation? Maybe it’s a bit of a gender thing. Growing up, the men in my neighborhood would spend a lot of time working on cars. Some of them hadn’t run in 20 years. You knew they never would again, but it was an activity that allowed them to talk to each other.

Were there things that you changed about this role along the way? It was clear in the script that my character was very angry. That anger towards his father was something Titus was open about. But as an actor, I’m always suspicious of anger. The question for me is, what’s fueling

it? There was a softness and a vulnerability that I wanted to find, and when you really dig into those hard moments, that’s what comes out.

This press tour isn’t just for the regular Hollywood crowd—you also have the whole art world involved. How did that feel?

Different. Y’all are a vibe, I gotta say. In the last few years, I’ve found myself in a lot of those spaces. I did a piece with Isaac Julien about a year and half ago [Once Again… (Statues Never Die), 2022]. Right now, I’m doing a thing with Arthur Jafa.

Is your feeling of the film’s impact aligning with the audience reactions you’re observing? Every person on this film put their back into it —it cost everyone a lot emotionally to get to that place and then live in that place. Sometimes when you do that, it’s a shame when people either don’t get to see it, or don’t feel it in the way you hope. That was not the case this time. Just today, a woman was like, “I saw it once, and I don’t know if I can ever bear to see it again. But I do know that I need to call my father.”

“AS AN ACTOR, I’M ALWAYS SUSPICIOUS OF ANGER. THE QUESTION FOR ME IS, WHAT’S FUELING IT?”

THE DIRECTOR ADAPTED COLSON WHITEHEAD’S PULITZERWINNING NOVEL INTO AN EXPERIMENTAL PORTRAIT OF LIFE IN THE JIM CROW SOUTH.

By Sophie Lee

Colson Whitehead entrusted the adaptation of his Pulitzer-winning 2019 novel, The Nickel Boys, to first-time feature director RaMell Ross with just two words of emailed encouragement: “Good luck!”

Before Nickel Boys, Ross had just one directing credit to his name: 2018’s Oscar-nominated documentary Hale County This Morning, This Evening. The lyrical snapshot of life as a Black American in Alabama earned the artist and filmmaker a meeting with the producers bringing Whitehead’s fictionalized account of atrocities documented at the infamous Dozier School for Boys to the screen. The Florida reform school, which shuttered in 2011, was the subject of years of

investigation linked to the rampant abuse—and close to 100 unrecorded deaths—of its students.

The film—shot entirely in point-ofview—follows two Black teens through their efforts to survive the institution, interspersed with flash-forwards to its unraveling in the 2010s and archival documentation that reminds viewers of its real-life reverberations. Ahead of its December release, Ross unpacks the atmosphere and allegories behind the action.

THIS WAS YOUR FIRST FORAY INTO DRAMA. DID YOU FEEL PREPARED? I came with my pockets completely empty. It wasn’t a conceptual leap, but it was a practical leap. I had to learn how to say “action,” and other silly things.

Sometimes I would forget to say “cut” and I’d just be like, “Mhm, great guys.” Everyone would be like, “So, are we done?” I’d say, “I don’t know, you tell me.” They’re like, “No, you tell us.”

ANIMALS APPEAR THROUGHOUT THE FILM: AN ALLIGATOR ROAMING THE HALLS, LITTLE LIZARDS EVERYWHERE. It’s like, That’s an omen—but if you don’t recognize it as an omen, then is it? One thing about being a person of color is, Is everything racialized? Maybe it’s nothing, maybe it’s something. It’s always plural, right? The images in the film are intentionally symbolic and metaphorical, but also just experiential. The alligator has a really specific historic resonance—for a time, Black children in the South were used as alligator bait. I wanted to nod to that lost history. It was a metaphor for the system—how blind, violent, and uncompromising it can be. But also, it’s just Florida.

HOW DID YOUR EXPERIENCE

FILMING HALE COUNTY INFORM THE FEEL OF NICKEL BOYS? To me, Hale County was like an orchestral attempt at vision. The poetics of Black subjectivity, or the poetics of Black visuals, are just so under-explored and limited. Those tools haven’t been in the hands of Black folks. Thinking about how to continually add images that have the ambiguity necessary to further dilute the muddy waters of Blackness is the connection between the two films, and maybe an ultimate aim of mine in making images. What a fun thing to try.

beach living completely redefined

One- to four-bedroom residences Starting at $1.5 Million

Expertly crafted by the world’s most visionary design minds, Five Park represents the intersection of function, beauty, and sustainability. The sleek tower offers a host of unprecedented amenities with in-house wellness and a private beach club bringing five-star service to everyday life. MOVE IN TODAY. LIMITED INVENTORY REMAINING.

JOIN US AT OUR ON-SITE SALES GALLERY 500 ALTON ROAD MIAMI BEACH FL 33139 SALES@FIVEPARK.COM 786 673 7974

The mastermind behind Cote and Coqodaq lifts the curtain on his rambunctious brand’s inner workings and shares the childhood hijinks that made him fall in love with food.

By Ella Martin-Gachot

Few restaurants have the sex appeal of Cote. With three locations—in New York, Miami, and Singapore—and a fourth in the works in Las Vegas, the Korean barbecue staple has established itself as a consummate crowd-pleaser—if you can snag a reservation. Behind it all is Simon Kim, a hospitality powerhouse who got his start at his parents’ restaurant in Tribeca before scaling up to Vegas and Manhattan fine dining in the aughts. This year, the Seoul native introduced Coqodaq, a new fried-chicken-forward eatery in Flatiron, and announced a monumental three-story dining nucleus on Madison Avenue. How does he do it all? Kim lets CULTURED in on a few of his secrets.

2024 has been a huge year for you. How do you keep your cool? The secret to keeping up is ignorance. I am such a sucker for creating. It’s not work, it’s not scary, it’s not bothersome. Over the years, we built enough infrastructure so that it’s not a candle flame; it’s a steam engine with a surplus of charcoal that we continuously feed, so the fire burns strongly and sustainably.

Almost a decade into the Cote story, what has been your biggest takeaway? I don’t have a banking background. I went from the dish pit to the boardroom, if you will. I always believed in hard work. We opened Cote New York with such fanfare: a Michelin star in four months, fully booked, making lots of money. We were scared that it might be a fad, but we believed in the

formula. It’s about true hospitality—and looking at it from a customer’s perspective. I wanted to create a restaurant where, if there’s a bell curve with one end being uber fine dining and the other end being McDonald’s, the majority would enjoy it. Same with Coqodaq, where NYU students and billionaires sit next to each other, having the best time of their lives in their own ways.

“I am such a sucker for creating. It’s not work, it’s not scary, it’s not bothersome.”

Tell us about the culinary environment you grew up in. I always grew up thinking my dad was like a secret Michelin inspector. We didn’t go play catch or hike or do the things that kids and fathers do. He would take us to fine-dining restaurants. My mother, who was an actress—she’s now acting again at 72!—was extremely passionate about food. She saw the dinner table as her time to shine. And I was the youngest of three, so I was kind of the maître d’. My older siblings and dad were like our customers.

You’re also a prolific collector. If you were to sit down for a meal with an artist right now, who would it be? I’d hang out with Andy Warhol. As a restaurateur, I balance commerce and artistry. He embraced that balance. So, I’d just want to hang out and vibe with Andy. Drink whatever he’s drinking—a lot of it—go to his studio, and talk.

By Helen Stoilas

“About Time,” the title of Charles Atlas’s first career retrospective at the ICA Boston, is both a joke and completely serious.

On the one hand, Charles Atlas’s work has always had a temporal focus, capturing the fleeting feeling of live performance, the immediacy of personal interactions, the perma-scroll of TikTok, and the free association of thought. On the other, recognition is long overdue for an artist who has been working for over five decades, basically invented the translation of contemporary performance onto screen, and has collaborated with the likes of Merce Cunningham and Marina Abramović.

For the past 10 years, Atlas has been working with his gallery, Luhring Augustine, to find a museum capable of handling the technical challenges that a retrospective of his work involves. “There’s not many museums that could do it,” Atlas says, adding that his ICA Boston exhibition, on view through March 2025, involves 31 channels of video across four gallery-filling installations. These in turn draw on clips from some 125 works Atlas has created over his career, which he has digitized and remixed.

Atlas’s interest in film and performance dates back to his childhood in St. Louis, where, he has said, “cinema was my escape outlet.” After dropping out of Swarthmore College, Atlas moved to New York in 1968 with the aim of seeing “every movie ever made.” A stage-managing gig at an off-Broadway theater led to a job as assistant manager for the legendary choreographer Merce Cunningham’s dance company. A 20-year-old Atlas taught himself to use a Super 8 camera on the job. The rest is art history.

Atlas’s ties to artists like Cunningham are a defining aspect of his career. Personalities, a new installation created for the ICA Boston, features video portraits of collaborators and friends such as Abramović, Leigh Bowery, and Johanna Constantine. The work is presented on 12 monitors arranged on pedestals in a gallery painted orange—Atlas’s signature hue, the color he dyes

his sideburns—with wallpaper drawn from his 2003 project Instant Fame!, in which Atlas created live video portraits of gallery visitors.

“Seeing all these pieces together, it kind of just hit me … it encompasses a lot of ideas,” Atlas says, adding later, “It’s a little overwhelming to see everything from 50 years gone by.”

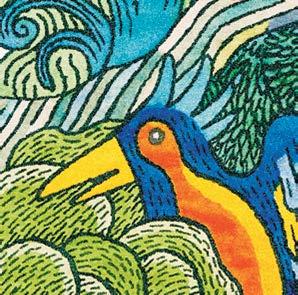

LOEWE FIRST CONTACTED THE KYOTO-BASED ARTIST DUO, KNOWN FOR THEIR WHIMSICAL AND DELICATE CERAMICS, ON FACEBOOK. IN THE SECOND YEAR OF THEIR CREATIVE PARTNERSHIP, THE SPANISH HOUSE AND JAPANESE STUDIO PLUMBED THE DEPTHS OF SEA AND SKY TO CRAFT THEIR MOST OTHERWORLDLY COLLABORATION YET.

By Katie Kern

“We do not have a particular relationship with fashion,” say Shohei Fujita and Chisato Yamano, the artistic duo behind Kyoto-based ceramic studio Suna Fujita. “Our work involves staying at home and working. We rarely meet people, so when choosing what to wear, we prioritize functionality.”

Though the artists’ wardrobes are built around more utilitarian aims, Suna Fujita’s latest collaboration with Loewe proves that their imaginations know no such constraints. The Spanish luxury house’s holiday collection transforms the Japanese ceramicist duo’s signature whimsical creatures—from space-dwelling

octopi to deep-sea hamsters—into a fantastical array of accessories, including a submarine-shaped bag that opens with a press of its chimney. The collaboration’s origin story is as unexpected as its results. Loewe discovered the artists some years ago through a simple DM. “We received an inquiry on Facebook about how to purchase our works. We informed them that we only sell during exhibitions,” the duo recalls.

What began as a casual social media exchange soon evolved into a multiyear creative alliance. Last holiday season, Loewe Creative Director Jonathan Anderson partnered with Suna Fujita for the first time—adapting motifs from their existing ceramics into new classics.

This time, Anderson challenged the pair to voyage into new territory. “Jonathan suggested focusing on the deep sea and space,” they explain. Building on their existing oceanic motifs, Fujita and Yamano plunged into research, crafting both digital and hand-drawn illustrations that would eventually populate Loewe’s signature silhouettes.

From delicate embroidery to intricate leather marquetry, each piece showcases the meticulous attention to detail and obsession with craftsmanship that define both the house’s artisans and the Suna Fujita universe. The limited-edition collection of bags, ready-to-wear, shoes, and accessories will be available in stores and online this November.

70 NE 40TH STREET, MIAMI

26 NOV - 12 DEC

DECEMBER 2 - 8, 12 - 7 PM

PALM COURT EVENT SPACE 140 NE 39th STREET, 3rd FL. MIAMI DESIGN DISTRICT

2BNONPROFIT

ARTECH COLLECTIVE

ARTS OF LIFE

BOOKLEGGERS LIBRARY

CENTER FOR CREATIVE WORKS

COMMUNITY ACCESS ART COLLECTIVE

CREATIVE GROWTH

LAND GALLERY

THE LIVING MUSEUM

THE OUTSIDER INSTITUTE

PROGRESSIVE ART STUDIO COLLECTIVE

STUDIO ROUTE 29

VINFENʼS GATEWAY ARTS

BY ESTHER ZUCKERMAN PHOTOGRAPHY BY RAFAEL RIOS

SHAWN LEVY IS KNOWN FOR HIS CHART-TOPPING BLOCKBUSTERS.

BUT WHILE HIS FILMS ARE BREAKING BOX OFFICE RECORDS, THE FILMMAKER IS QUIETLY LAYING THE GROUNDWORK FOR A SECOND PASSION: COLLECTING.

“SHAWN LEVY MADE HIS NAME AS THE MAN BEHIND EARLY-AUGHTS, FOURQUADRANT FAMILY FARE LIKE CHEAPER BY THE DOZEN AND THE NIGHT AT THE MUSEUM FRANCHISE. HIS PROFILE HAS ONLY RISEN IN RECENT YEARS.”

“WHEN HE

WAS STARTING OUT, IT WAS STEVE MARTIN—A LONG-TIME COLLABORATOR— WHO TOLD HIM TO SUBSCRIBE TO SOTHEBY’S CATALOGS AND BEGIN STUDYING.”

Shawn Levy picks the works that adorn the walls of his Downtown Manhattan home in much the same way he chooses what films he’s going to direct. “I like art that feels singular and specific, but also built for visual joy,” he says, sitting barefoot and cross-legged on a plush couch in his den. “And I pick movies that inspire feeling, laughter, and joy.”

Levy is known for crowd-pleasers. He made his name as the man behind early-aughts, fourquadrant family fare like Cheaper by the Dozen and the Night at the Museum franchise. His profile has only risen in recent years—first as an executive producer of the massive Netflix hit Stranger Things, and this summer as the director of Deadpool & Wolverine, the record-breaking Marvel jaunt and Levy’s biggest box office success to date (pulling in over a billion dollars worldwide). The filmmaker’s home, which he shares with his wife, Serena, is filled with Pop and contemporary art that reflects the same playful spirit as his oeuvre. Their collection features work by the likes of Jonas Wood, Jasper Johns, and Julian Schnabel, the latter of which, Walt Whitman IV (Air), 2016, sits in Levy’s office across from the masks of the two superheroes with whom he has become so closely associated.

As soon as I arrive, Levy offers me a tour. In the entryway, there’s a Robert Rauschenberg etching, Solitaire, of a bird on a pier—the first work of art the Levys ever bought. It hangs near an Anna Weyant flower study, and opposite a pink

Warhol Sidewalk print of the pavement outside Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. A series of 10 Yoshitomo Naras hangs above the couple’s breakfast nook. “I always sit on the same side of the table,” he says, “because I love looking at those Naras twice a day.”

The story of Levy’s entrée into collecting isn’t a typical one. For one thing, he has a star-studded cast of advisors at his fingertips. When he was starting out, it was Steve Martin—a longtime collaborator who appeared in the Levydirected films Cheaper by the Dozen and The Pink Panther —who told him to subscribe to Sotheby’s catalogs and begin studying. Among Levy’s most treasured pieces is an Ed Ruscha emblazoned with the words “Lady Joy.” He acquired it with the help of yet another frequent co-conspirator: Owen Wilson, a mutual friend he shares with Ruscha. “The piece describes my everyday domestic life,” says Levy, who has been married for nearly 30 years and has four daughters. “I thought, I just need it.” Levy has worked with art consultant Cardiff Loy, but also seeks counsel from friends like Tobey Maguire, a dedicated collector himself, or advisor Sophia Cohen.

While the Levys will occasionally find themselves drawn to what they describe as “more provocative or troubling” works, they focus on pieces that imbue their home with warmth. “The works in our collection—whether it’s peaceful, meditative paintings like that Tony Lewis across the living room, or

something more audacious like the Sterling Ruby, with its use of color and texture—are built for viewer engagement,” the filmmaker tells me. “They are inviting, not repellant.”

This is not to say that his love of art is confined to the domestic realm. In fact, the climactic scene in Deadpool & Wolverine is inspired by a Lucian Freud triptych the filmmaker showed to his visual effects team and art department. “To this day, several colleagues from the movie make fun of me for that hifalutin allusion,” he says. “But watch that scene: Emma Corrin, Hugh Jackman, and Ryan Reynolds all move through this super fast, stuttery conniption. It all comes back to those paintings.”

Are there any Freuds in his collection? Not yet. “There are some artists I’m fascinated by who I either haven’t had an opportunity to acquire or couldn’t afford,” he continues. He’s still mourning a Barbara Kruger that got away— Jennifer Lopez has it in her office, in the same West Hollywood building as Levy’s company headquarters. “No matter how many times I knock on her door and ask to buy it, I cannot get my hands on it,” he says with a laugh.

Still, Levy is reluctant to think of himself as a collector in any “official” sense. Instead of sharing any grand ambitions for future acquisitions, he returns to the idea of joy. “I do know that living with art makes a home more lovely,” Levy tells me. “It’s very much a part of our life now.”

When Alessandro Michele unveiled his first Valentino Garavani collection this past summer, the fashion world dropped everything to take it in.

Its densely packed prints, rivulets of pearls, and faux-fur trimmings made one thing crystal clear: A new era had begun.

Amongst the decadent array of offerings from Michele’s inaugural line are two accessories handpicked for Valentino devotees new and old: the showstopping Fleur Lumineuse necklace and impeccably bite-sized Vain bag. Winter’s doldrums may have settled in, but these pieces will enliven your uniform—any day of the year.

Argentine director and producer Laura Citarella has emerged as one of the most exciting voices in contemporary cinema. Now, she joins the all-star list of female filmmakers commissioned for Miu Miu’s Women’s Tales initiative.

BY MARÍA BELÉN ARCHETTO

Laura Citarella speaks fondly of the cultural education her parents gave her as a child in Argentina. Although she was born in La Plata, the capital of the country’s Buenos Aires Province, the memories she cherishes most are from the summers she spent in their hometown of Trenque Lauquen.

This small city in the Pampas region later became the backdrop for a number of the director’s films, including her celebrated 2022 feature Trenque Lauquen, which follows two men searching for the missing woman they love and earned Citarella a nomination for the Orizzonti Award for Best Film at that year’s Venice Film Festival. More recently, the country’s low grasslands served as the setting for El Affaire Miu Miu, a short commissioned by the cult Italian house as part of their ongoing Women’s Tales series. The film debuted in Venice this past August during the Giornate degli Autori, followed by a two-day talks program featuring brand ambassadors and actors Cailee Spaeny, Molly Gordon, and Valentina Romani.

El Affaire Miu Miu grew from Citarella’s interest in Hitchcockian mystery and female Sherlock Holmes figures who are on the hunt for “women that, for different reasons, run away.” The film begins, fittingly, with a fashion shoot starring an Italian model, set in the heart of the Argentine Pampas. After the shoot wraps, the model vanishes, and three of the town’s detectives—all women—embark on an investigation, piecing together clues hidden in cast-off Miu Miu garments and the surrounding landscape.

With the film’s release, Citarella is the latest creative to join the ranks of the Women’s Tales initiative, which since 2011 has invited visionary female directors to explore themes of vanity and femininity in commissioned short films. Previous participants include Ava DuVernay, Miranda July, Janicza Bravo, and Chui Mui Tan.

The fusion of fashion and landscape was partic-

“FROM THE BEGINNING, CLOTHES HAD TO BE LIKE ANOTHER PROTAGONIST WITH A NARRATIVE VALUE, A NARRATIVE WEIGHT.”

ularly compelling for Citarella. “I was interested in exploring how a woman wearing Miu Miu arrives, stands, and walks in the Pampas—to explore and see how this image is forged,” the director muses. “From the beginning, clothes had to be like another protagonist with a narrative value, a narrative weight. They didn’t have to be something that contributes to forging a character—they had to be a main character in the construction of the story.”

“THE SHOW WAS SUPPOSED TO BE ABOUT AMERICA,” HEJI SHIN SAYS OVER ZOOM, “BUT IT TURNED OUT TO BE A BIT MORE METAPHORICAL.” FOR HER FIRST INSTITUTIONAL SOLO EXHIBITION IN THE UNITED STATES, ON VIEW AT THE ASPEN ART MUSEUM THROUGH MARCH 2025, THE CULT IMAGE-MAKER HAD PLANNED TO DRIVE ACROSS THE UNITED STATES. SHIN ENDED UP HOMING IN ON FLORIDA, TRAINING HER LENS ON NASA’S KENNEDY SPACE CENTER IN CAPE CANAVERAL AND THE STATE’S COASTLINE, WHICH WAS RECENTLY STRUCK BY TWO CONSECUTIVE HURRICANES. “I WAS LEFT WITH ROCKETS AND WAVES,” SHE SAYS WITH A LAUGH.

“I wanted to focus on rocket launches, not because they’re quintessentially American, but because they embody the extremes of American technological advances. I didn’t want to get embedded in the Cape Canaveral community—I just wanted to go there and photograph rockets.”

“I do think there’s a consensus that transgression is not very interesting at the moment. People feel like they want to just look at good stuff and go back to more classical things—maybe even to what art has traditionally been occupied with.”

ANYONE EVEN VAGUELY FAMILIAR WITH SHIN’S OUTPUT OVER THE PAST DECADE KNOWS A VEER INTO LANDSCAPE PHOTOGRAPHY IS UNEXPECTED. THE KOREAN-GERMAN PHOTOGRAPHER HAS EMBRACED SHOCK FACTOR—COPS COPULATING, BABIES CLAMBERING THROUGH BIRTH CANALS, KANYE WEST MID-DOWNFALL— UNTIL NOW. IN THE DUAL SERIES ON VIEW IN ASPEN, SHIN STRIPS A POCKET OF AMERICA DOWN TO ITS ELEMENTS. THE OUTCOME IS, IN HER WORDS, “EPIC.” HERE, SHE UNPACKS THE STORY BEHIND ONE IMAGE IN THE SHOW, SHARED EXCLUSIVELY WITH CULTURED, AND WHY SHE’S LEAVING TRANSGRESSION BEHIND—FOR NOW.

BY ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

WHEN HE WAS 10, Daniel Humm had a revelation in front of Claude Monet’s “Water Lilies.” There, in the lower level of Paris’s Musée de l’Orangerie, he burst into tears. “I didn’t know why,” Humm recalls. “Was I happy? Was I sad? From that moment on, I knew that I was deeply moved by art.”

Three decades later, Humm joined the ranks of one of Manhattan’s most vaunted eateries. Over his time at the three-Michelin-starred Eleven Madison Park, the chef has transformed the institution into a destination for food—and art. Works by the likes of Olympia Scarry, Rita Ackermann, and Rashid Johnson—also some of Humm’s closest friends—adorn the restaurant’s sleek interior. This fall, the chef escalated this passion, opening Clemente Bar just a few stories below, alongside none other than Francesco Clemente, whose hand-painted frescoes envelop diners in the dreamlike world he’s become known for. Here, the chef reflects on the undertaking: a modern monument to the finer senses.

“THAT’S A GREAT LESSON FOR RESTAURANTS: WE SHOULD TAKE OUR WORK VERY SERIOUSLY, BUT NOT OURSELVES.”

YOU’VE EARNED ALMOST EVERY ACCOLADE A RESTAURANT OR CHEF CAN HOPE FOR. HOW DO YOU GET YOURSELF EXCITED ABOUT SOMETHING NEW? For Francesco and me, the word we focused on with Clemente Bar was “historic.” Nothing is permanent these days, but this is as close as it gets. We were inspired by Kronenhalle in Zürich. Diego Giacometti made the lighting, and it’s hung with Rauschenberg and Picasso paintings. There are not many places with that kind of permanence.

WHAT WAS YOUR FIRST IMPRESSION OF FRANCESCO?

YOU’RE FRIENDS WITH SO MANY ARTISTS. WHY DO YOU THINK THAT IS? I have like five people I’m very close to in my life, and they’re all artists. I feel understood by them. We put ourselves out there, which is vulnerable. Artists know that better than anyone. Art and beauty really move me... I’ve always been interested in moments in art history where artists did something really new, like with the beginning of abstract painting, or Duchamp, or Fontana, who took the canvas and sliced it.

WHAT CAN THE WORLDS OF FOOD AND ART LEARN FROM EACH OTHER? The beauty of Clemente Bar is that it’s not a gallery or a museum—when you lean back in your chair, your head can touch Francesco’s paintings. That’s a great lesson for restaurants: We should take our work very seriously, but not ourselves.

THIRTY-FIVE YEARS AFTER HER LAST NEW YORK SOLO SHOW, LORETTA DUNKELMAN IS EMBARKING ON THE LATEST CHAPTER OF HER CAREER AT POLINA BERLIN GALLERY.

“Does that seem like an awkward painting to you?”

Loretta Dunkelman was examining a foamcore model of New York’s Polina Berlin Gallery in her Lower Manhattan loft. Looking anything but “awkward,” even as a tiny printout, the painting in question was rimmed by lemon yellow, with blue and white passages resembling clouds. It would soon be prominently displayed at Polina Berlin.

The 87-year-old artist displays confidence— along with moments of doubt—in a practice that has long been out of the spotlight. Over her six-decade career, Dunkelman co-founded A.I.R. Gallery, the pioneering SoHo venue dedicated to female artists. Her work has entered the collections of the Whitney Museum of

By Brian Boucher

American Art and the Smithsonian Institution. But like so many female artists of her generation, Dunkelman has faded from the art world’s memory, even though she has been steadily working—drawing and painting precise, meditative pieces at her live-work space a few floors above Bowery and Canal Street—all this time.

The New Jersey native studied under the artist Tony Smith at New York’s Hunter College in the 1960s. After graduation, the trailblazing curator Marcia Tucker included her in the 1973 Whitney Biennial (“I’ve called to do some business with you,” Dunkelman remembers Tucker saying). The piece she showed, Ice-Sky, 1971–72, is a luminous five-panel drawing that moves through shades of blue, pink, and white. When Berlin saw it on the

floor during a recent studio visit, “It almost felt like a James Turrell. It emanates light, like a portal to the sky.”

But in the 1960s, the then-ascendant Minimalist artists disapproved of Dunkelman’s sensuous abstractions. “She was an outlier, even though on the face of it there seems to be so much common ground,” Berlin says. Plus, “she’s a woman. That’s not lost on me.”

Now, Dunkelman is enjoying a new generation’s perspective on her work—and gaining a fresh perspective of her own. She recently removed one of her large abstractions, Tintern Abbey, 1987, from storage. “I thought it was awful all this time, but only because the photos were bad,” she says. “When I pulled it out, I loved it!”

The designer’s latest furniture collection is a love letter to travel, craft, and film.

BY PHOEBE ROBERTS

Giorgio Armani is taking Milan’s reputation as a global capital of fashion and design to a whole new level.

The Italian designer’s latest Armani/Casa collection transports shoppers to locations as far-flung as Japan, China, and the Middle East—all without leaving its historic headquarters. Aptly titled Echi dal Mondo, or “Echoes from the World,” the collection is inspired by Armani’s travels around the globe and draws on decades of careful research.

The initial inspiration for the project is rooted in a childhood dream of the designer, who grew up in the northern Italian town of Piacenza. “I would have liked to have been a director,” Armani said in a statement, “[so] I imagined a ‘cinematic’ journey to the countries that have always inspired me: places and cultures that spark highly personal reworkings.”

The result, which debuted at Salone del Mobile this past spring, is an evocative display at Palazzo Orsini, with each room in the 17th-century villa corresponding to a different geographical location. Visitors follow a golden ribbon through a series of rooms punctuated with fashion, furniture, and mementos from Armani’s personal travels, borrowed from his private home.

Those seeking to take part in Armani’s “cinematic” wanderings can view the pieces at Palazzo Orsini or simply shop the collection themselves, with designs including the Japanese samurai-armor-inspired Virtù cabinet—featuring a katana-like handle and tatami-effect interiors—and

the Chinese-influenced Vivace table, a silverleaf-topped creation with legs that resemble bamboo stalks.

Other standouts include the “Arabian Nights”–inspired set, which includes a new edition of the Club bar cabinet with a blue leather interior and an upholstered grosgrain fabric screen. Influences from Berber culture can be glimpsed throughout, from the canaletto walnut wood and geometric-patterned velvet of the Morfeo bed to the tassel appliques that enhance the Esagono coffee tables’ upholstered fabric.

References to European culture also abound: The Trocadero table, featuring plexiglass legs and a platinum-lacquered, wave-textured top, could be snatched right out of a midcentury design book, as could the Riesling bar cabinet, with its sleek canneté plexiglass front calling to mind dinner parties of yore.

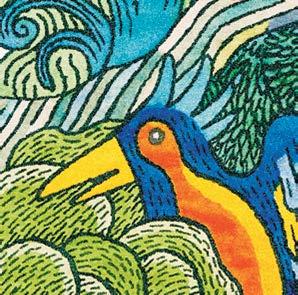

Like a canonical film, these pieces—and indeed the entire Echi dal Mondo collection—ignite the imagination and transport their owners to places they have never been—without even crossing their doorstep.

“I WOULD HAVE LIKED TO HAVE BEEN A DIRECTOR.”

—GIORGIO ARMANI

BY JULIA HALPERIN

Marguerite Humeau has the curiosity of a child, the sensitivity of a poet, and the technical precision of a surgeon. The London-based French sculptor is bringing this potent combination to the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, where her first large-scale museum show in the United States will see the light this winter.

Humeau is best known for collaborating with all manner of experts—anthropologists, ornithologists, even clairvoyants—to make art that conjures the ancient past or imagines the distant future. In one of her earliest works, she recreated the voice box of Lucy, the 3.2-million-yearold skeleton discovered in Ethiopia in the 1970s. Last year, she installed more than 80 kinetic sculptures across a 160-acre expanse of the San Luis Valley in Colorado. It was one of the largest land artworks ever created by a female artist.

The time Humeau spent in that drought-stricken Colorado landscape helped inspire the Miami exhibition “\*sk\*/ey-,” which opens Dec. 3. “It got me thinking about what forms of life can actually exist in this world,” Humeau says. Watching the wind push tumbleweeds across the desert and whip dust into roving clouds, the artist began imagining a speculative future where “we have to become creatures of the air.” This line of inquiry, she reasoned, would be especially relevant for a show in Florida, which is a key thoroughfare for migratory birds.

“I WANTED THE NEW SCULPTURES TO FEEL LIKE THEY ARE ALIVE, THAT THEY’VE GROWN FROM THE SOIL. THEY ARE IN A STATE OF BECOMING.”

Footage she shot in Colorado forms the basis for a new video that envisions what it might look like for life to leave an uninhabitable Earth behind and become airborne. (The score, by composer and clarinetist Angel Bat Dawid, is unsurprisingly heavy on the wind instruments.) In the next gallery, a trio of sculptures appears to emerge from the ground like forest zombies. Another group of sculptures, perched high on the wall, looks like winged creatures poised to take flight. Their surfaces resemble those of surreal creatures in a Leonora Carrington painting, rippled and otherworldly.

As part of her research, Humeau convened a group of textile designers for more than a month to experiment with treating felt and organza silk in ways that evoke mold and dead skin. “I wanted them to feel like they are alive, that they’ve grown from the soil,” Humeau says of her new sculptures. “They are in a state of becoming.”

By Johanna Fateman

Following the cult writer’s passing, our critic recalls his bitchy radicalism, wild prose, and uncensored takes on the art world.

The great novelist and art critic Gary Indiana, who passed away on Oct. 23 at age 74 and left a hole in the city’s literary firmament the size of his name state, isn’t generally remembered for his favorable reviews. Maybe it’s because even his positive assessments were not positive—not in tone. They emerged from a deep anticapitalist snobbery. A “rave” from Indiana, circa 1985–88, during his tenure as senior art critic for The Village Voice, might start with a scathing blind item or two about the vacuous or vulturous characters he encountered on the gallery beat. His caustic disdain for the commercial structures and depraved figures of the (art) world was justified, implicitly, on aesthetic as much as political grounds. Though in the universe of his writing— by the rules of his bitchy radicalism—no such distinction exists.

Yet Indiana did love, like, and approve of many things. I know that from the conversations I was lucky enough to have with him over the years, though I knew him only a little. In the ’90s, I was a studio assistant for two artists who were close to him. We would gossip when I answered the phone. More than a decade later, when Indiana and I were both writing for Artforum, we talked at parties. Not so long ago, I told him how great I thought Horse Crazy was (I had just reread his 1989 novel). He told me it was not great. I asked him, “What is a great novel, then?” He sighed and said very wistfully, “Wuthering Heights.”

Flipping sadly through Vile Days (which anthologizes his Voice columns) on the day I learned of his death, I found more things he admired. In his reviews—which tended, thrillingly, to push the

form beyond recognition—there is louche precision, grudging respect, and fleeting moments of wonder. As an art critic, I’d love to say he’s been an influence, but that implies something actually rubbed off. I can only claim inspiration.

At the Voice, he was charged with covering the Reagan-era art boom, during the Reagan era of mass death. As the new galleries of the East Village scene, often peddling the neo-Expressionist painting Indiana despised, ushered in a phase of rapid gentrification, the AIDS epidemic stole his friends away. He would not pretend it wasn’t happening; in his writing, he did not cordon it off. Though Indiana would hate to be a role model, I’m sure, his work offers some lessons for our own vile days. Sometimes, to write about what you love, you must start with what you hate.

As it turns 60 years old, The Bass Museum of Art, Miami Beach’s storied institution, gears up for yet another growth spurt.

BY SOPHIE LEE

Each year, 50,000 people visit The Bass Museum of Art. “The Bass’s audience is diverse,” says Executive Director Silvia Karman Cubiñá. “When our curators plan exhibitions, we make sure the art offers multiple cultural and intellectual touchpoints that are engaging to this wide audience.”

Since opening in 1964 to house the private collection of John and Johanna Bass, the museum has become a tentpole of the city’s creative ecosystem—

bolstered by seasonal influxes of visitors around events and fairs like Art Basel Miami Beach. In 2022, the institution was awarded $20 million as part of Miami Beach’s General Obligation Bonds, a $159 million sum that supported 16 city-owned cultural institutions. In addition to ringing in its 60th anniversary, the museum is now in the throes of its next period of expansion.

“We are looking to build a new, state-of-the-art gallery for temporary exhibitions as well as social spaces for public programs,” explains Karman Cubiñá. “Simply put, a new flexible gathering space where art and people meet.” This includes building enhancements, part of which will house new media works; public works, like the planned takeover of a rotunda in Collins Park; and support for the museum’s educational programming.

In the meantime, the exhibitions currently on view

at the museum embody its enduring mission, six decades on. “‘Rachel Feinstein: The Miami Years’ demonstrates the ongoing commitment to commissions with the presentation of [the artist’s] 30-foot painting of enamel on mirror,” says Chief Curator James Voorhies. “‘Performing Perspectives: A Collection in Dialogue’ looks both forward and back with a selection of historical works installed in relation to the contemporary collection.”

What might the next 60 years hold for the institution? Ultimately, says Karman Cubiñá, “With new communities of full- and part-time residents moving to the area, plus a generation of young adults raised alongside Art Basel Miami Beach, The Bass has become a place for people to get together and connect while seeing art.” The changes underway at the institution are a sign of commitment to that burgeoning, ever-shifting audience— as the city evolves, so too will The Bass.

Miami Beach Convention Center

December 6 - 8, 2024

WHAT’S THE DISH THAT MAKES YOU FEEL AT HOME WHEREVER YOU ARE IN THE WORLD? Rice and ketchup.

WHAT’S THE DISH THAT BEST REPRESENTS WHERE YOU’RE AT IN YOUR LIFE RIGHT NOW? Spaghetti and ketchup.

LUCIEN SMITH IS AN ART-WORLD SWISS ARMY KNIFE. THE LOS ANGELES NATIVE HAS SET AUCTION RECORDS—AND EXPERIENCED THE VOLATILITY OF A RUTHLESS MARKET. HE’S ALSO MODELED FOR SUPREME, LAUNCHED A CLOTHING BRAND WITH HIS MOTHER, AND ESTABLISHED A NONPROFITCUM-SUPPORT GROUP FOR CREATIVES ACROSS THE GLOBE. HIS LATEST VENTURE IS ONE FOR THE HISTORY BOOKS. THIS DECEMBER, SMITH WILL BRING BACK FOOD, THE ARTIST-RUN RESTAURANT THAT GORDON MATTA-CLARK, TINA GIROUARD, AND CAROL GOODDEN OPENED IN SOHO IN 1971. FIVE DECADES AFTER ITS CLOSURE, THE CULT CANTEEN EMBODIES AN ERA OF ARTISTIC POTENCY FILTERED THROUGH THE TASTE BUDS. SMITH’S ITERATION—FOR WHICH HE’S TAPPED COLLABORATORS LIKE CHEF MATHIEU CANET AND ARCHITECTS MICHAEL ABEL AND NILE GREENBERG—PROMISES TO BE NO LESS RAMBUNCTIOUS. AHEAD OF ITS OPENING, THE ARTIST LET CULTURED IN ON HIS CULINARY PREDILECTIONS.

By Ella Martin-Gachot

WHAT WOULD IT TAKE FOR YOU TO LEAVE A GOOGLE OR YELP REVIEW?

Gun to the head.

WHO DO YOU MOST LOVE TO COOK FOR? WHO DO YOU MOST LOVE TO COOK WITH?

Myself. My little brother.

WHAT’S YOUR TAKE ON COOKBOOKS?

I’ve never used a cookbook.

WHAT’S THE MOST EXPENSIVE MEAL YOU’VE EVER HAD?

I ate raw horse once. I’m sure that was pricey.

GO-TO BODEGA ORDER?

A chopped cheese or Jamaican patty with hot sauce and a peach Snapple.

ONE MEAL THAT CHANGED YOUR LIFE?

I ate a hot pepper as a kid in the Philippines on a dare. I had smoke coming out of my ears.

WERE YOU A PICKY EATER GROWING UP?

Not really. I did have to be forcefed, because I never wanted to eat.

JANUARY 23 - 26, 2025

FORT MASON CENTER fogfair.com

January 22, 2025 Preview Gala Benefiting the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

PIER 3

AGO Projects, Mexico City

Altman Siegel, San Francisco

Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York

Anthony Meier, Mill Valley

Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco

Casemore Gallery, San Francisco

Crown Point Press, San Francisco

David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

David Zwirner, Los Angeles

Fergus McCa rey, New York

Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris

Galerie Maria Wettergren, Paris

Gallery FUMI, London

PIER 2

Charles Mo ett Gallery, New York

Chris Sharp Gallery, Los Angeles

Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles

Crèvecœur, Paris

Fernberger, Los Angeles

François Ghebaly, Los Angeles

House of Seiko, San Francisco

Johansson Projects, Oakland

Jonathan Carver Moore, San Francisco

Municipal Bonds, San Francisco OCHI, Los Angeles

Rebecca Camacho Presents, San Francisco

Superhouse, New York

Gallery Japonesque, San Francisco

Gladstone, New York

Haines, San Francisco

Hauser & Wirth, Los Angeles

Herald St, London

Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco

Hostler Burrows, New York

Jenkins Johnson Gallery, San Francisco

Jessica Silverman, San Francisco

KARMA, West Hollywood

Kiang Malingue, Hong Kong

kurimanzutto, New York

LEBRETON, Monte Carlo

Lehmann Maupin, New York

Lisson Gallery, London

LUHRING AUGUSTINE, New York

Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Beverly Hills /

Gió Marconi Gallery, Milan

Marian Goodman Gallery, NewYork

Mendes Wood DM, New York

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York

Micki Meng, San Francisco

Night Gallery, Los Angeles

Nino Mier Gallery, New York

Peter Blum Gallery, New York

pt.2 Gallery, Oakland

Sarah Myerscough Gallery, London

SIDE GALLERY, Barcelona

Southern Guild, Los Angeles

Talwar Gallery, New York

Tina Kim Gallery, New York

Venus Over Manhattan, New York

BY ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

DATING AT WORK IS FROWNED UPON. BUT IN THE ART WORLD, WHERE WORK AND LIFE ARE SO OFTEN INTERTWINED, THE TEMPTATION CAN BE STRONG. HERE, INDUSTRY VETERANS AND NEWCOMERS ALIKE SHARE THEIR RULES OF THUMB FOR DATING AND BREAKING UP IN THE INDUSTRY.

FINDING LOVE MAY SEEM ANTITHETICAL TO NAVIGATING THE INS AND OUTS OF A FAST-PACED, FLAKEY, AND OFTEN FINANCIALLY DRIVEN ART WORLD. BUT SOME OF US LIKE A CHALLENGE, AND THE INDUSTRY’S ROMANTIC INHOSPITALITY MAY BE THE VERY THING THAT MAKES DATING WITHIN IT SO HARD TO RESIST. SOME ART-WORLD COUPLES HAVE WITHSTOOD THE TEST OF TIME (CARROLL AND LAURIE, ANYONE?); OTHERS HAVE SPIKED MANY AN ART PUBLICATION’S WEB TRAFFIC WITH THEIR TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS. BUT WE’RE NOT HERE TO JUDGE—AFTER ALL, THERE’S NOTHING LIKE A GOOD RUMOR, AN AWKWARD OPENING RUN-IN, OR A MEET-CUTE ON THE FAIR FLOOR.

TO FIND OUT HOW THE ART WORLD DATES, CULTURED ASKED DOZENS OF ITS DENIZENS FOR THE ROMANTIC RULES THEY LIVE BY—FROM BLANKING YOUR PARTNER AT THEIR OPENING TO THE RATIONALE FOR SLEEPING WITH THEIR GALLERIST.

If you like attention and love gossip (especially when it is about you), then you should go out with a really famous artist. Friends, enemies, and strangers alike will count the days until your relationship goes up in flames, and you will come out the other side with a couple of trinkets, a battered sense of self, and 100 new jokes!

HADI FALAPISHI ARTIST

DON’T GO TO THE STUDIO ON VALENTINE’S DAY.

BENJAMIN GODSILL ART

Never ever date in the art world. If it ends poorly you are going to end up running into your ex at openings, dinners, airport lounges, Swiss train stations, and the like for the rest of your days. Do you really want to have to air-kiss and make small talk with someone who did you dirty for the next 20-plus years?

Only date in the art world. Who else is going to understand why you need to take a call from “an important client” at 7 p.m. on Christmas Eve; why you need to fly halfway across the world for a week to have lavish dinners with the same people you see all the time in London, New York, and Hong Kong; and why the painting you purchased for $20,000 from “the next big thing” is still on your wall 10 years later and worth less than the price of your Chinese takeaway order?

CULTURAL CRITIC AND CONSULTANT

At your partner’s art opening, pretend you don’t know him, get drunk with your friends, and wear something that shows your boobs—or whatever your version of that is. His opening is work for him, and what would be more annoying than having someone show up at your work and try to do it with you? (That being said, he needs to stay hydrated and will probably forget, so you should bring over water every now and then.)

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF THE ART PRODUCTION FUND

A broad warning that the art world is very small. Trust me—your dating past and poor decisions will haunt you at every art fair you attend, so choose wisely! With that said, do have a frivolous makeout session on the beach with an artist if the opportunity presents itself. It will be a good story for years to come.

SENIOR DIRECTOR OF 52 WALKER

ARTIST

Love is itself a creative act. Fucking your collaborators is one thing, sure, but extending that curiosity is essential to keeping an art practice alive. It makes the experience of dating more integrated—and much more interesting.

I would ask in a straight relationship that women understand one thing: Men often have fuck-nothing on their minds. We like to sit on the couch thinking about sex, our work, or abstract things like “I wonder if there will ever be time travel,” and we spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about traffic. Allow for this.

ARTIST, WRITER, AND GALLERY ASSISTANT

Have sex with your partner’s gallerist. It would be “unprofessional” for them to, so it’s your responsibility. Then, pillow-talk about the gallerist’s genitals.

SOCIOLOGIST AND AUTHOR

There are only three types of art couples: those who hate each other but look good in pictures, those who love each other and hide from the public, and those who do whatever they want, whenever they want, without any regard for what anyone thinks. Decide early on which you want to be and make sure your partner is on board, or else one of you will always be pissed off.

ARTIST

Painters: Steer clear of them because they are already in a relationship with their paintings. Sculptors: excellent at assembling IKEA furniture. Video artists: Grab ’em if you can find them but be prepared to be in their work for life. Fiber artists: good for winter. Art handlers: good with their hands ;)

ANYONE WHO CAN GET YOU INTO THE GUGGENHEIM FOR FREE IS A KEEPER, ANYONE WHO CAN GET YOU INTO THE MET FOR FREE IS EVERYWHERE, AND ANYONE WHO CAN GET YOU INTO THE WHITNEY FOR FREE IS A LIAR.

WRITER, CURATOR, CO-OWNER OF FRANCIS KITE CLUB, AND FORMER PRESIDENT AND EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF THE QUEENS MUSEUM

Don’t expect the bubbly person you met at an opening to actually like going to openings, parties, or anything social. They are just as likely to be an introvert who would rather be at home.

ART

OF THE @THEARTDADDY_ INSTAGRAM ACCOUNT AND SUBSTACK

CURATOR AND WRITER

Museums are great dates for curators. However, be prepared for a 10-hour marathon of cross-town visits where the details of every exhibition—tombstones, layout, research, installation, and, of course, the art—are deeply contemplated. It’s fun! But your body will ache afterward.

WRITER AND EDITOR

Despite our field’s global pretensions, do not date long-distance or else your soon-to-be ex will start sleeping with some MassArt grad living in Allston whose “project” is dressing in handmade monochrome outfits.

IF YOU’RE NOT A FAN OF EACH

CURATOR AND EDLIS NEESON ARTISTIC DIRECTOR AT THE NEW MUSEUM

Very early on in my career I decided not to date artists, and it’s one principle I truly stuck to. I could say it was to avoid conflicts of interest or head and heart aches, but another way to put it is that

LIKE A SHRINK OR A DOCTOR, I WOULD NEVER LIKE TO BRING MY PATIENTS HOME.

I thought it would be healthier not to date within my own field, but then I met Cecilia [Alemani, director and chief curator of High Line Art] and the overlap actually turned out to be pretty special. Not sure if it makes for a better work-life balance, but so far so (very) good.

We all like an artsy outfit, but you don’t always have to come dressed like art on view. Dress like yourself—that will grab someone’s attention.”

Studio time is sacred. Make sure the person you’re

SIX DECADES INTO HER POLYCHROMATIC CAREER, JOAN SNYDER IS MORE SOUGHT-AFTER THAN EVER. HER FIRST SHOW WITH THADDAEUS ROPAC BRINGS HER HOMESPUN MAXIMALISM TO LONDON THIS WINTER— PROVING SHE’S NOWHERE CLOSE TO SLOWING DOWN.

By Ella Martin-Gachot

Joan Snyder is a morning person. Whether she’s in Brooklyn or Woodstock, the 84-year-old artist wakes up at 5 a.m.—“if not earlier”—on any given day. She makes tea, eats breakfast, hangs out with her partner Maggie, a retired judge, and does the crossword puzzle. Then she heads to the studio. Sitting in her Upstate atelier, Snyder admits hers is a hermetic life. “The pandemic was perfect for me,” she adds with a laugh. “I didn’t have to go anywhere or see anyone. I could just paint every day with absolutely no interruptions.”

Art has been a solace for six decades. Before her Whitney Biennial inclusions, before her Guggenheim Fellowship, before selling out solo shows, Snyder was an anxious sociology student at Douglass College. Then she discovered painting. “It was literally like speaking for the first time,” she recalls. “I could say what I wanted to say.” The studio and the canvas are still a refuge: “This is [where] I feel best. I love making paintings—I love it more than doing almost anything [else].”

There is one occasion for which Snyder will readily leave her ivory tower: music. She’s been a fan of Philip Glass’s forever. (“He was our plumber in the ’70s,” she deadpans, recalling the scantily equipped Mulberry Street loft she shared with her ex, the late photographer Larry Fink. “[Philip] was working with his family’s business while he was making Einstein on the Beach.”) She spent the year of 1992 listening to Mozart’s Great Mass while grieving her mother. And she makes regular pilgrimages to Woodstock’s Maverick Concert Hall for classical performances. It’s there, in “our Tanglewood,” that many of Snyder’s paintings begin. “Listening to live music inspires me more than going to a museum,” she says.

Every Joan Snyder work is a palimpsest of sorts. At concerts, sketchbook in hand, the artist

translates what she hears onto the page. The painter then returns to her concert sketches intermittently, annotating them with a new idea or motif each time. It can take years for one to make its way into a painting, and the finished product is rarely a mirror of the initial gesture. Snyder primes and stains her canvases before pasting a farrago of other materials: Paper towels, bits of fabric, twigs, dried flowers, and papier-mâché can all form the base for the alternatingly abstract and figurative shapes that populate her paintings. To this density, swaths of high-octane hues are added (she sees colors like notes of music). Often, words follow —a reflection of her stream of thoughts as she paints. When I point to one work, on which the letters “OMG” are scribbled, and ask where they came from, she says, “I just thought, Oh my god, because it was kind of a crazy painting.”

Over the years, the art world has closely followed Snyder’s evolution from the abstract “stroke” paintings that made her name in the early ’70s to her embrace of maximalism and upending of the landscape genre in the decades since. Her work is in the collection of every major American museum and has been the subject of over 60 solo exhibitions. This winter, European audiences will get a formal introduction to her practice, with her first show with Thaddaeus Ropac on view in London through February 2025. Most of the included pieces are leaving Snyder’s archive for the first time. “We borrowed maybe three paintings altogether,” she explains. “The rest are from my collection.” After months of working on the newest canvases in the show, the artist decided to make another “crazy painting.” Beholding it in her studio, before it too shipped across the ocean, Snyder was happy to have leaned into its excess. “It’s overdone, but to me it’s just perfect,” she confesses, before continuing, “No one is more surprised than I am that I’m still making these paintings. I mean who does that?”

The Brutalist landmarks that dotted Ivana Berendika’s childhood in the former Yugoslavia inspired her appreciation for sculpture. Today, the collector’s Baker’s Bay home provides a backdrop for her creative passions.

When Ivana Berendika made her first visit to a museum—to see an exhibition of World War II ephemera—she was confronted with artifacts that felt all too familiar for a child growing up in what was then Yugoslavia: bombs, guns, and tanks. “There was no space for art in that envi-

BY SOPHIE LEE

by JEREMY LIEBMAN

ronment; that was our reality,” she remembers. The Serbian jewelry designer and collector’s current surroundings are a far cry from those beginnings. After leaving the region at 18 and settling in Miami, Berendika now resides in New

York, Montana, and the Bahamas. Her home in Baker’s Bay, where she spends part of the year, is airy, verdant, and full of works from a formidable collection that includes a coterie of female artists like Jenny Holzer, Kelly Akashi, and Lauren Halsey. “One positive thing we had in Yugoslavia

“EVERYTHING WE OWN IN LIFE IS JUST BORROWED. IT COULD ALL BE GONE TOMORROW, SO I TRY TO ENJOY IT WHILE I HAVE IT.”

were these amazing Brutalist monuments,” she recalls. “Subconsciously, I think they developed my love for sculpture, which has always been my favorite medium.”

These days, Berendika divides her time between her roles as an arts patron, independent designer, and parent. Though so much has changed along the way, Berendika maintains a worldview shaped by her earliest experiences. “Everything we own in life is just borrowed,” she muses. “It could all be gone tomorrow, so I try to enjoy it while I have it.”

Here, the creative lets CULTURED into her Baker’s Bay home for a tour of the pieces currently driving that exuberance.

WHAT’S YOUR FAVORITE WORK IN THE HOUSE? My favorite piece of art in this house is by the artist Gabriel Rico. I purchased it without really having a good wall for it, so it sat in storage

for the next couple of years until I called Gabriel and begged him to reconfigure it. He was very sweet and divided the work onto two walls even though it was never intended to be shown that way.

WHICH WORK IN YOUR HOME PROVOKES THE MOST CONVERSATION FROM VISITORS? The Jesus sculpture by Elizabeth Englander has sparked numerous conversations. Elizabeth created this sculpture during her residency in a Spanish nunnery, where she stumbled upon old swimsuits worn by the nuns and used them to craft this body of work.

WHICH ARTIST ARE YOU CURRENTLY MOST EXCITED ABOUT AND WHY? When it comes to the artists I’m interested in adding to the collection, it’s Maja Ruznic, whose last show at Karma blew me away, and Ambera Wellmann, whom I consider to be one of the best painters of her generation.

“ONE POSITIVE THING WE HAD IN YUGOSLAVIA WERE THESE AMAZING BRUTALIST MONUMENTS. SUBCONSCIOUSLY, I THINK THEY DEVELOPED MY LOVE FOR SCULPTURE, WHICH HAS ALWAYS BEEN MY FAVORITE MEDIUM.”