US History to 1877 for Cambridge International AS Level History

COURSEBOOK

Tony McConnell, Eric Rivas and Peter Ferdinando

with Digital access

Tony McConnell, Eric Rivas and Peter Ferdinando

with Digital access

2.1

2.2

3.1

3.3

5.1 Why and how did the Market Revolution impact the US economy and society from 1820 to 1850?

5.2 Why did westward expansion impact US politics and culture in the mid 19th century?

5.3 How and why did US expansionism impact indigenous people from 1815 to 1877?

6.1 How and why did sectional divisions widen between 1846 and 1861, resulting in the American Civil War?

How far did the Civil War transform the lives of Americans?

What were the aims of Reconstruction and how successful was it?

7.2

7.3

Please be aware that this book contains some historical texts and images that may distress the reader. This material reflects the language and attitudes of the period in which they were created, but not does not align with the current values and practices of Cambridge University Press and Assessment. Teacher support is advised.

This suite of resources supports learners and teachers following the Cambridge International AS Level US History to 1877 syllabus (8101). The components in the series are designed to work together and help learners develop the necessary knowledge and skills for studying History.

The Coursebook is designed for learners to use in class with guidance from the teacher. It offers coverage of the AS Level US History to 1877 syllabus. Each chapter contains explanations, definitions and a variety of activities and questions to engage learners and develop their historical skills.

The Teacher’s Resource is the foundation of this series. It offers inspiring ideas about how to teach this course including teaching notes, how to avoid common misconceptions, suggestions for differentiation, formative assessment and language support, answers and extra materials such as worksheets and historical sources.

This book contains a number of features to help you in your study.

Each chapter begins with Key questions that briefly set out the topics you should understand once you have completed the chapter.

The timeline at the start of each chapter provides a visual guide to the key events which happened during the years covered by the topic.

Getting started activities will help you think what you already know about the topic of the chapter.

Activities are a mixture of individual, pair and group tasks to help you develop your skills and practise applying your understanding of a topic. Some activities use sources to help you practise your skills in analysis.

Key terms are important terms in the topic you are learning. They are highlighted in bold where they first appear in the text, and definitions are given in the Key terms boxes. All of the key terms are included in the glossary at the end of the book.

Key concept boxes contain questions that help you develop a conceptual understanding of History, start to make judgements based on your knowledge and understanding, and think about how the different topics you study are connected.

Key figure boxes highlight important historical figures that you need to remember, and briefly explain what makes them a key figure.

Reflection boxes give you the opportunity to think about how you approach certain activities, and how you might improve this in the future.

These questions, written by the authors, help you prepare for assessment by writing longer answers.

Sample answers to some of the practice questions, accompanied by notes on what works well and how they could be improved. After reading the comments, you are challenged to write a better answer to the question.

The answers and the commentary are written by the authors.

Tips are included in the Preparing for assessment chapter. These give advice on important things to remember and what to avoid doing when revising.

Each chapter ends with a checklist of the main points covered in that topic, and gives you space to think about how confident you are with these points.

You should be able to:

Needs more workAlmost thereReady to move on

KEY QUESTIONS

This chapter will help you to answer these questions:

• How and why did politics in the US change from 1820 to 1850?

• Why did a wave of reform movements emerge in the antebellum period from 1820 to 1850 and how successful were they?

• Why did the debate over slavery intensify from 1820 to 1850?

1819–20 Missouri Compromise

Jan 1825

Feb 1826 American Temperance Society formed

New Harmony utopian society created

Feb 1825 “Corrupt bargain” election of November 1824 is finally resolved

Jul 1822 Planned date of Denmark Vesey’s slave revolt

Nov 1832 A South Carolina convention nullifies the Tariff Acts of 1828 and 1832

Nov 1828 Andrew Jackson is elected president for the first time

Jul 1832 Andrew Jackson vetoes the bill to re-charter the Bank of the United States

1839 Theodore Weld, Angelina Grimké, and Sarah Grimké publish American Slavery As It Is

Apr 1846–Feb 1848 Mexican–American War

Mar 1836 Texas declares independence from Mexico 1843 Margaret Fuller writes The Great

Sep 1836 Ralph Waldo Emerson publishes Nature

May 1828 Tariff of Abominations enacted 1833 Whig Party formed

Dec 1845 Texas

With the benefit of hindsight, it can be easy to see the causes of the American Civil War as you study the period 1820–50. In groups of three or four, discuss what you already know about the US at the start of the period covered by this chapter, in 1820. Explore the following questions. Think in broad terms—politically, socially, economically, and culturally—but try to provide specific examples too. Make notes of your ideas.

1 What strengths did the US seem to have in 1820?

2 What weaknesses did it seem to have?

3 Were there any particular unresolved problems? If so, what were they, and why were they unresolved?

The second half of the 1810s appeared to bring peace and stability to the young USA. The War of 1812 was over, and relations were improving with Britain, an important trading partner. After the Missouri Compromise of 1819–20, the expansion of slavery into the Louisiana Purchase (see Topic 3.3) was governed by rules that both pro- and anti-slavery factions could accept. A new generation of political leaders appeared ready and able to replace the ageing Patriots. American culture was beginning to flourish.

Politics became about who should participate in political culture. New political parties fought for the votes of a far wider selection of men; women sought rights of their own. Divisions emerged between North and South, between supporters of centralized financial institutions and their opponents, between market capitalism and new societies. New religious ideas arose; some withered while others grew.

American politics, culture, economics, and society in 1850 were richer and more complex than those of 1820. Eventually, though, the central contradiction of American life—the existence of slavery in the Land of the Free—would prove to be too big a problem to overcome.

Look back at the notes you made during your discussion in the “Getting started” section. Write two well-argued paragraphs outlining the strengths and weaknesses of the USA. Start the two paragraphs as follows:

• “The USA’s greatest strength in 1820 was …”

• “The USA’s greatest weakness in 1820 was …” or “The USA’s biggest problem in 1820 was …”

The Missouri Compromise settled one of the major political issues of the time. As a clear principle, as new states were added to the Union, a balance would be maintained between slave states and free states.

Meanwhile, an industrial revolution was beginning in the USA. The 18th-century American republic, founded to protect the economic and political interests of landowners, who alone had the vote, would no longer be enough. The growth of industry would create an economy with multiple parts that depended on each other. There would need to be an internal market, meaning tariffs, and perhaps a bank. This would have to be managed, perhaps by the federal government.

The new generation of politicians reorganized the loose structure of political parties into something more formal.

By 1840, two main parties emerged. The major figure in this realignment was one who straddled the era of the Patriots and the new era to come.

Tariff: a government charge on goods entering or leaving a country.

Realignment: a political concept describing the way in which existing political parties are replaced by new ones; in practice, the process is not usually smooth, and individual politicians form differing alliances over a period of time until they settle into new political parties.

The “Era of the Common Man” is the era of Jacksonian Democracy. The “common man” is both Andrew Jackson, president of the USA from 1829 to 1837, and the typical voter who sent him to the White House. Jackson came from humble origins, and he and his allies exploited those origins during his campaign to be president. He also exploited the expansion of voting rights to the vast majority of free (white) men. As president, he opposed institutional power—whether the institution was the Bank of the United States, the civil service, or even Congress.

Jackson said that as president he was responsible for protecting the rights of the people against the government. He was like an ancient Roman tribune, the protector of the people, and his campaign slogan was “Let the people rule.” His first State of the Union address made it clear that he intended to let the people to rule through the president, as the official elected by the whole country. His argument would have been strengthened if, in every state, there was an element of direct election for the presidency. However, this was not the case in 1829.

The American electoral system is complex, and the process of selecting the president is its most complex part. Presidents are chosen by the Electoral College, and the Electoral College is chosen by the people of the state.

Until 1816, around half of US states had used elections to appoint their members of the Electoral College. In 1820 and 1824, three-quarters of the states did so. In 1828, all but Delaware and South Carolina used popular elections. By 1832, Delaware had fallen into line, but South Carolina would not follow suit until after the Civil War. Jackson benefited from this practice, and wanted to maintain the trend toward popular participation in the vote for the presidency.

The period immediately preceding the first presidential election involving Andrew Jackson (1824) is known as the “Era of Good Feelings.” Monroe had won re-election in 1820 with almost no opposition, despite the stresses of the Missouri Compromise and a poor economy. One reason for this was Monroe’s popularity within his party, the Democratic-Republicans. However, he was helped by the fact that the opposition party, the Federalists, had no candidate and had effectively ceased to exist. This lay at the heart of the Era of Good Feelings—but with more candidates, and more voters, those good feelings did not last.

Jacksonian Democracy: a term used to describe the policies and styles of governing and campaigning adopted by Andrew Jackson and his allies, such as Martin van Buren and John C. Calhoun; Jacksonian Democrats were the forerunners of the modern Democratic Party, as a coalition of poor immigrants, laborers, and people who live in cities.

State of the Union: a speech that the president of the United States gives to Congress every year, about the achievements and plans of the government.

Electoral College: the body that appoints the president and vice president; each state chooses a number of electors to vote for these two offices, and that number is equal to the number of representatives the state has in Congress, plus its number of senators (always two).

In the original 13 states, voting was generally restricted to significant landowners. The 13 states were not identical, but they shared a mostly agricultural economy, although there were differences in what was farmed and who did the farming. Property—and votes—were in the hands of men, almost all of them rich and white, who felt they had a duty to govern the country properly.

In the states formed out of the Louisiana Purchase, every white man was a pioneer, and every one was self-made. Nobody had family land or obligations to inherit. And so in four of the six states admitted in that area— Indiana, Illinois, Alabama, and Missouri—there was universal manhood suffrage from the start. In Louisiana, there was a reasonably difficult tax barrier to suffrage, and in Mississippi, there was a less complex one to overcome. Those six states were all admitted to the United States between 1812 and 1821, and they formed a quarter of the 24 states of the Union.

Several factors determined why states abolished or failed to introduce property requirements around voting. Society was now more complex in several ways.

• Economically: The industrial revolution had begun, and wealth could now be obtained not just through large landowning but also through manufacturing.

• Commercially: There had been a Market Revolution. In general, the average citizen had enough money to buy commercial goods, which meant they had a choice. They might wish to choose in the political sphere too.

• Educationally: Political ideas could be easily spread, and improved communications helped this.

In the new societies of western states, there were never great barriers to suffrage, but in the existing states these barriers had to be abolished. This was not easy to do, as it required Constitutional Conventions to meet and agree.

Pioneer: someone who is among the first to enter and live in an area, especially colonial Americans in the western USA.

Universal manhood suffrage: the right of all adult male citizens in a political system to vote. Barrier to suffrage: obstacles that had to be overcome before someone was allowed to vote; there were property barriers, meaning that only people with property worth a certain amount could vote, and tax barriers, meaning that only people paying a certain amount of tax every year could vote; also known as “qualification for suffrage.”

Market Revolution: a period of transition from a traditional, moral, colonial economy to a more modern capitalist economy.

New York provides an interesting case study in the changes to manhood suffrage in this period. Useful sources exist in the papers of the New York politician—and future president—Martin van Buren. A Constitutional Convention was held in New York in 1821. This meant that delegates were elected from across New York and instructed to come together to discuss amending the New York constitution to extend the franchise.

(by themselves) in the interests not just of aristocrats but of poorer, “common man” New Yorkers. Second, the generation of Patriots was dying out, and it seemed to be a good time to make a change.

Early in the conference the delegates agreed that there should be a tax barrier to suffrage. However, the following day the discussion moved on to whether New York should in fact allow all men over the age of 21 to vote, regardless of what tax they paid. Van Buren and others were concerned that this would distribute the number of votes too unevenly, favoring New York City and giving the north of the state less of a political voice. In the end, the delegates at the Convention agreed to extend the franchise to all white men. There was then a long discussion over what to do about suffrage for free African-American men. There was no talk of extending the franchise to women.

Franchise: the right to vote in an election.

Revisions of state constitutions to exclude women and free African Americans from voting

Simply considering allowing women and free African Americans to vote was progressive in this period. Only Kentucky (briefly in 1792 and then again in 1838) and New Jersey had allowed any women to vote. Only New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania had allowed any African Americans to vote. In many states, free African Americans were not actually banned from voting, but they could not be citizens—and only citizens could vote.

The New York constitution adopted in 1821 said that African Americans could vote if they had lived there for three years and had property worth $250. This was a large sum of money, which excluded all but a handful of black men from voting. Van Buren argued that this would be an incentive for black families to work hard to build up their property.

There were two reasons why the convention happened in New York in 1821. First, van Buren and his allies in Albany had been seeking to control New York politics— with great success. It made sense for them to broaden the franchise, as they were confident they would win the support of any new voters. Van Buren’s allies (known as the “Albany Regency”) wanted New York to be run

In fact, this was a change from the previous position where, in voting—although in no other way—black men and white men had been equal. While the number of African-American voters did not reduce significantly (it had been very low to start with), the number of white voters increased greatly in New York.

In New Jersey and Pennsylvania, more extreme measures were taken. Some women in New Jersey had been allowed to vote since 1790, but that changed in 1807 when the property qualification for voting in New Jersey was abolished. At the same time, women and African Americans were excluded from voting. In New Jersey, both women and African Americans were generally expected to vote Democratic-Republican rather than Federalist. With the franchise extended to poorer white men (also expected to vote Democratic-Republican), the black and female vote was no longer needed.

In Pennsylvania, in 1837–38, the debate was over African-American suffrage. Free black people were allowed to vote if they met the property qualification. Toward the end of the Convention, at which the franchise was extended to non-property owners, there was an attempt to restrict the vote to white men only. The debate fell along predictable lines. Those against the move recognized that free African Americans had a stake in society, and some were very rich. They also argued that to exclude African Americans from voting was undemocratic and illiberal, especially as in Pennsylvania it would mean taking the vote away from them.

On the other side of the debate were three main arguments:

• Most other states that had amended their constitutions had excluded African-American voters when doing so.

• There had been a rapid increase in the population of African Americans in Pennsylvania, and it was preferable not to give them political power.

• Giving African Americans the vote in Pennsylvania would encourage more African Americans to come there.

Changes in political campaign tactics to appeal to new voters

The presidential elections of the period provide interesting examples of the way in which politics adapted to the new voting population. For the first time, popularity among the people (rather than just among politicians or landowners) would really matter in determining who became president.

In Pennsylvania, the question was avoided until the elections of November 1837, some of which seemed to have been swung by African-American votes. Politicians opposed to the election results argued that African Americans were not free men, and should not have been allowed to vote. As a result, African-American Pennsylvanians lost the right to vote. One state bucked the trend towards disenfranchising certain groups. In 1838, in Kentucky, women who had property and were the heads of their household were given the vote—the only place in the USA to do so.

In the early days of the US, the electoral colleges of particular states had met in their state capitals to debate whom to elect as president. In 1800, fewer than half the states chose their electoral colleges by popular vote; in the others, they were chosen by the state legislatures. In states along the eastern seaboard, voters were still mostly prosperous landowners. They were politically engaged and knew about the candidates for the presidency without needing to be told much about them.

The “Era of the Common Man” brought new voters, who came from all different backgrounds and lifestyles. Some were frontiersmen in the west; others were part of the expanding middle class created by the Market Revolution; still others were the voters van Buren had worried about in big cities such as New York City— urban, immigrant, and poor. Presidential candidates could not rely on the fact that these new voters, from different social, economic, and geographic places, would have accurate political knowledge. Their votes were there to be won, and to do so, politicians used a variety of tactics. Not only did the number of eligible voters increase, but so did turnout in presidential elections, from 27% in 1824 to 78% in 1840.

Frontiersman: someone who lives on the border between cultivated land and wild land, especially in the American West.

The election of 1824 was a contest between four members of the same political party, the DemocraticRepublicans. Their official candidate, William Crawford (the Secretary of the Treasury) was selected at a nominating caucus in February. Only around a quarter of Democratic-Republican congressmen had even attended the nominating caucus. With no opponent from the Federalist Party, which was in decline, Crawford seemed to have no realistic challenge in his attempt to win the presidential election.

In the “Era of Good Feelings,” he might have run unopposed, as Monroe had in 1820. But times had changed—this was the “Era of the Common Man.”

The Democratic-Republican party in Tennessee felt that because so few congressmen had attended the nominating caucus, Crawford’s nomination was undemocratic. They wanted the people of Tennessee to have a choice, so they nominated their own senator, Andrew Jackson.

This encouraged other politicians to seek the presidency too. In particular, three men had been waiting for Monroe to retire, and despite Crawford’s nomination, they decided to run for the presidency anyway. They were:

• John Quincy Adams, the Secretary of State

• Henry Clay, the Speaker of the House

• John C. Calhoun, the Secretary of War.

In the campaigns that followed, there were some debates about policies, such as the role of tariffs and the precise nature of federal oversight over the growing transport network. However, the main talking point was which of the five main candidates (which quickly dropped to four when Calhoun withdrew from the race) had the right personality to win over the “common man.”

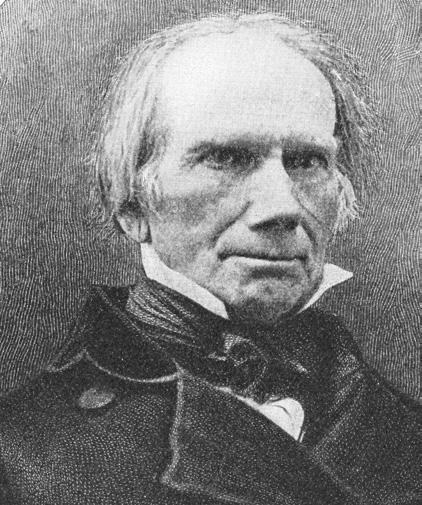

John Quincy Adams (1767–1848)

Adams, the son of the second president, had been brought up in politics. In his childhood, he followed his father around on ambassadorial duties. He served as a US senator and then a diplomat, and was Monroe’s Secretary of State. He succeeded Monroe by winning the controversial election of 1824. After his presidency (1825–29), he became a Whig and served as a US representative.

Andrew Jackson (1767–1845)

Jackson was born into poverty in the area that now spans the border between North and South Carolina. He had enlisted in the Revolutionary Army by 1780, making him—just about—a member of the Patriots’ generation. He was a lawyer and a highly successful general before entering politics, and was a US senator from 1823 to 1825. He served as president from 1829 to 1837.

Henry Clay (1777–1852)

Clay was a lawyer who became Speaker of the House in 1823, and then served as John Quincy Adams’s Secretary of State. He spent a significant amount of time as a US senator, and is regarded as one of the most influential members of Congress in the first half of the 19th century.

Nominating caucus: a meeting of the elected officials of a political party, at which they choose a candidate for an election.

Whig: a member of a political party in the US in the early 19th century that believed Congress should have more power than the president; Whigs supported business and economic development.

On your own, research one of the five contenders for the presidency in the 1824 election. Draw up a table listing their strengths and weaknesses. When you have finished your research, get together with other students who have researched the other four candidates. Share your findings and discuss the strengths and weaknesses of each candidate. As a group, try to agree which one made the best potential president.

Look at your assessment of each man as a candidate for the presidency. Do you think there are different criteria for being a good candidate and being a good president? If so, what are those criteria? Would you change your selection based on that?

When the election was held, none of the candidates won 50% of the votes in the Electoral College. The Constitution stated that if this happened, the House of Representatives would choose the president from the top three contenders, who were Jackson, Adams, and Crawford. Clay, who had come fourth, was the Speaker of the House, and it soon became clear that he would be able to influence the House’s decision. Jackson’s supporters offered Clay the position of Secretary of State in return for Clay’s backing. Clay turned it down, and instead supported Adams, who won the presidency. Jackson’s attempt to influence Clay by offering him the post of Secretary of State was not the “corrupt bargain” that gave the election its name. As soon as he became president, Adams made Clay his Secretary of State. Jackson accused Clay of having sold his vote for his position. He called that a “corrupt bargain,” and he gave Clay a new nickname, “Judas of the West.”

With this in mind, the campaign for the presidency used some new vote-winning ideas, and made better use of some old ideas. Contrafacta were used for the first time in the 1824 campaign. Newspapers published editorials alongside political cartoons to promote particular candidates. Calhoun’s newspaper was called The Patriot, a deliberate reference to the previous generation of presidential candidates. Candidates had nicknames. Jackson had long been “Old Hickory”—a reference to a tree whose toughness Jackson possessed. Clay was “Henry of the West.” All of these tactics were designed to deliver simple messages about candidates and make sure they were recognized.

These new tactics tended to help Jackson most. He was already the most famous candidate, and the only one who had actually fought in the Revolutionary War (at the age of just 13). Jackson was a successful general and a reluctant politician, just like George Washington. In the end, he won 43% of the popular vote and 38% of the Electoral College, but it was not enough.

Contrafacta (singular contrafactum): popular songs in which the lyrics were adapted so that they became campaign songs for a particular candidate.

The idea of the “corrupt bargain” became a key campaign tactic in the next presidential election, in 1828. It did not matter that Jackson’s supporters had tried to do exactly the same thing. They, and Jackson, had realized that promoting the idea of a stolen election would be a powerful way to win votes the next time.

It became common to campaign for or against policies that would be identified with a particular candidate for the presidency. For example:

• In 1828, Jackson’s supporters engineered a disagreement about tariffs and used that as a reason to vote for him in the election.

• In 1832, while he was president, Jackson engineered a controversy about the national bank for similar reasons.

• In 1836, on behalf of his chosen successor, Martin van Buren, Jackson accelerated the same disagreement. In each of these cases, Jackson’s popular position became a major factor in why the Democratic-Republicans won the vote.

• In 1844, the election was about whether westward expansion was a good idea, and James K. Polk was the candidate who took the most popular stance.

It might seem odd to point out that the outcome of presidential elections were influenced by policy, but this was unusual at the time. Before Jackson, Congress, not the president, was the chief policy-maker, and

presidential candidates rarely discussed what they proposed to do when they took office. All these policies are explored in more detail later in this chapter.

Campaign slogans

Campaign slogans moved beyond simple nicknames. In 1828, Jackson used the slogan “Let the people rule.” He meant that he, as president, would rule in the interests of the common people. Adams’ supporters responded with a contrafactum, “Little Know Ye Who’s Coming,” warning that if Jackson was elected there would be a demonic plague. They also used newspapers to get their message across, calling Jackson a “ruffian” and accusing him of gambling and adultery. It is important to note that Adams himself was not responsible for any of the smear campaigns against his opponent. In their turn, Jackson’s supporters highlighted in the press the corrupt bargain of the 1824 election, and pointed out that voters had a chance to make things right in 1828. Jackson was at least partly responsible for that.

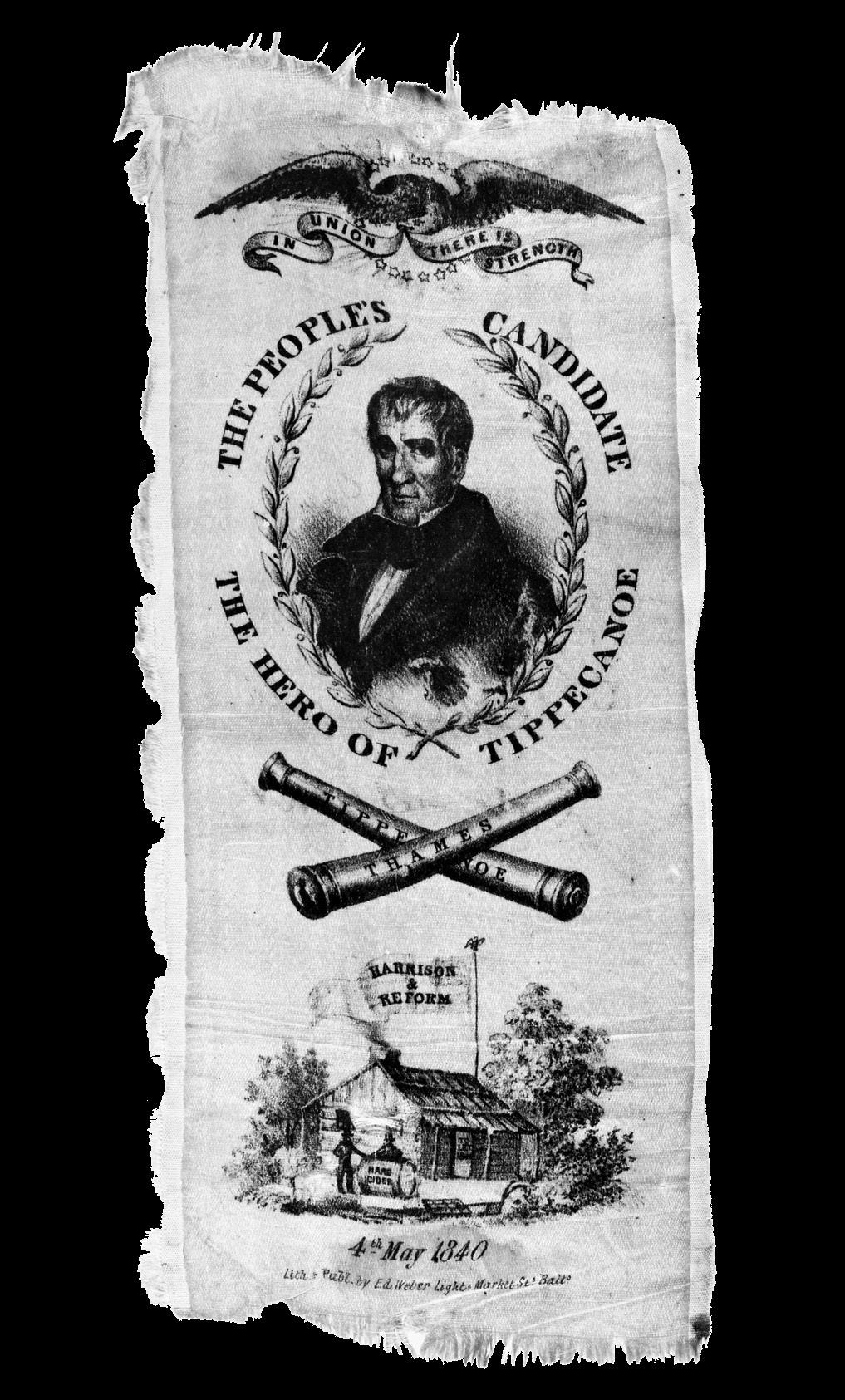

In 1840, the Whig William Henry Harrison and his running mate John Tyler used a slogan based on the contrafactum “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.” Tippecanoe referred to a famous battle that Harrison had won against an alliance of indigenous peoples in 1811. The contrafactum contained a direct attack on the incumbent president, van Buren: ‘Van is a used up man.” Harrison was 67 at the time of the campaign, and the Democrats (as van Buren’s party was by now known) made an issue of his age to fight back against the powerful slogan. The Baltimore Republican suggested pensioning Harrison off by giving him a bottle of hard cider and a log cabin.

The Whig press seized on this and started to echo it in support of their candidate. They invented campaign merchandise, and people could buy walking canes with cider motifs. Harrison became the “log cabin candidate.”

In fact, he had not been born in a log cabin and he came from a far wealthier background than van Buren.

But none of that mattered—Harrison won the 1840 election, in part because he successfully created a persona for himself—poor, hardworking—that appealed to the “common man.” It also helped that Harrison was associated with Jackson who, although from a different party, really had been born into poverty in a log cabin.

Much of Harrison’s popularity was also rooted in the fact that he had been a general in the army. Zachary Taylor won the 1848 election using his military background to help him. He, Jackson, and Harrison all won popularity because of their status as war heroes— and perhaps because of the echo of the first president, General George Washington.

Running mate: a political partner chosen for a politician who is trying to get elected; in presidential elections, a candidate’s running mate is usually the person they will appoint to be vice president if they are elected.

Incumbent: referring to someone who holds or held a particular official position.

Read the following text. Explain which elements of this contrafactum might have helped Harrison and Tyler to win the election of 1840.

What’s the cause of this commotion, motion, motion

Our country through?

It is the ball a-rolling on For Tippecanoe and Tyler too. For Tippecanoe and Tyler too.

And with them we’ll beat little Van, Van, Van, Van is a used up man.

And with them we’ll beat little Van

Like the rushing of mighty waters, waters, waters, On it will go!

And in its course will clear the way For Tippecanoe and Tyler too […]

[…]

Now you hear the Vanjacks talking, talking, talking,

Things look quite blue, For all the world seems turning round

For Tippecanoe and Tyler too […]

Let them talk about hard cider, cider, cider

And Log Cabins too, It will only help to speed the ball

For Tippecanoe and Tyler too […].

‘Tippecanoe and Tyler Too’, a poem by Alexander Coffman Ross, 1840

Change

There were clearly substantial changes in the way presidential campaigns were carried out in a quite brief period, from 1820 to 1850.

What were the most important changes, and continuities, in the following areas?

• the importance of policies in election campaigning

• the media (press, contrafacta, merchandise) of election campaigns

• the importance of personalities in election campaigns.

You may wish to revisit your answers when you have finished reading this chapter.

Andrew Jackson began his presidency (1829–37) as the “champion of the Common Man” and he ended it being called (by some) “King Andrew.” In 1828, Jackson campaigned against the tariffs favored by Adams—the so-called Tariff of Abominations (see “Tariff of Abominations, 1828”). He also opposed Adams’s view that members of Congress should work for the good of the country, rather than for their constituents, in providing for internal improvements of the transportation network. Adams stood for economic nationalism; Jackson stood for states’ rights—even if that jeopardized the growth of the nation’s economy.

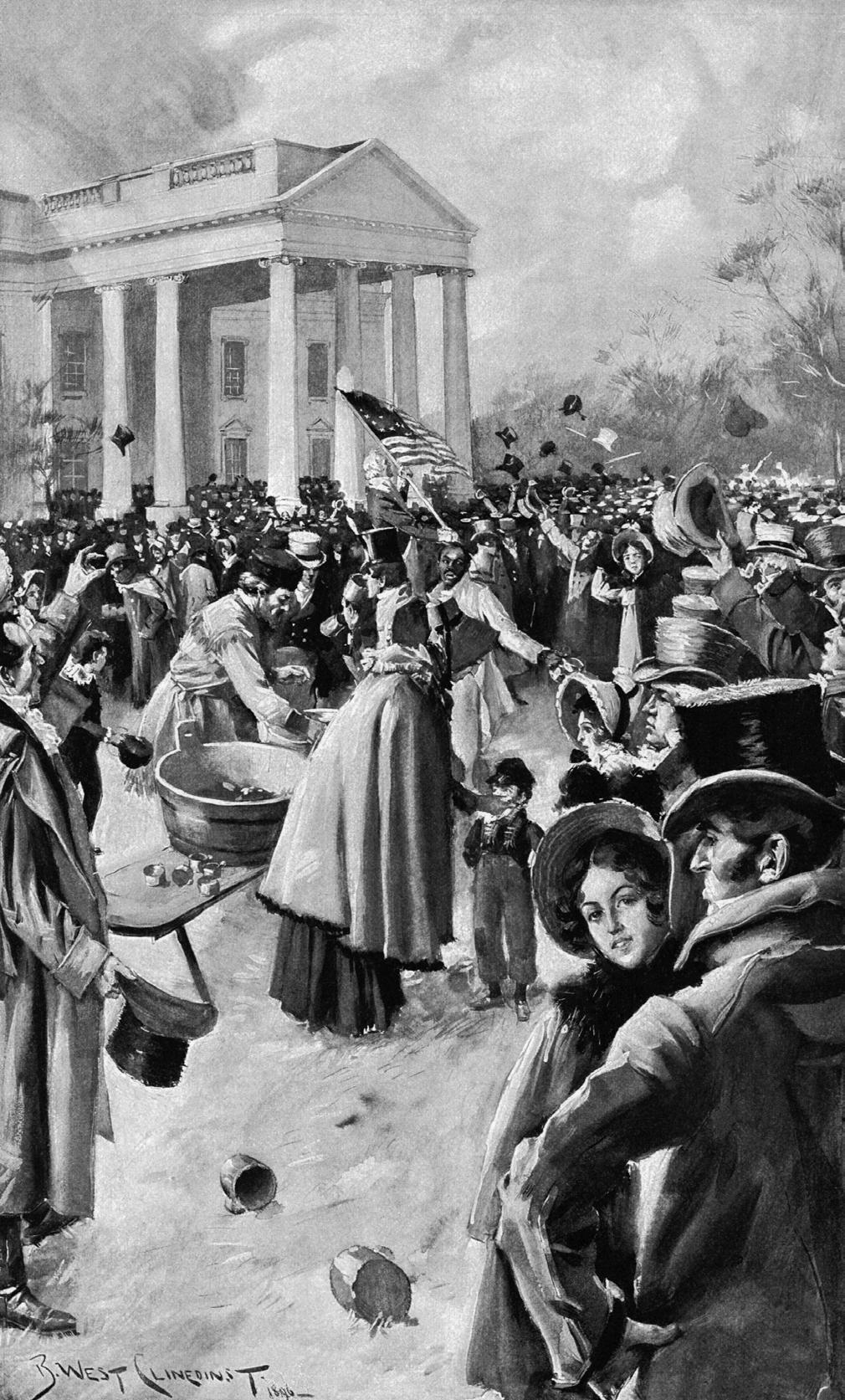

There is a famous story about the day of Jackson’s inauguration in March 1829, when Washington, DC was filled with 20 000 overexcited people. Some of these supporters stormed the White House, and Jackson was forced to escape through a bathroom window. Shocked Washington residents referred to the crowd as “King Mob.”

Jackson used this popularity to extend the power of the presidency, claiming he was the people’s representative and champion, there to protect them from the rest of the government. Several striking features of his presidency demonstrated this:

• He attacked the Supreme Court’s decisions as part of the Bank War (see “The Bank War”).

• He expanded executive (presidential) authority, including by setting policy, which had previously been Congress’s job.

• He set himself up as the clear, personal leader of his party, the Democrats or sometimes Jacksonian Democrats.

• He was seen to ignore his official cabinet in favor of a kitchen cabinet of unofficial advisers.

Jackson was a strong supporter of states’ rights and low tariffs, preferring the federal government (indeed, any government) to stay out of the people’s way. He was also a nationalist who was prepared to defend the union from any threats, including the threat of arguments about slavery. He refused to admit Texas to the Union in 1836, knowing that to do so would reopen the damaging question of slavery by upsetting the balance of the Senate. By blocking attempts to sell off public land, Jackson slowed the process of the expansion of the USA. Only two states were admitted in his presidency, right at the end: Arkansas, a slave state, and Michigan, which was free.

Kitchen cabinet: a term originally used by Jackson’s opponents to refer to the group of unofficial advisers he consulted rather than his official cabinet; it is still used to refer to unofficial advisers to people in power.

The conflict between Jackson and the Bank of the United States is an important and revealing part of his presidency. He did not start it, but he made sure that he won. The first Bank had been chartered by Alexander Hamilton in 1791, and it lasted 20 years (see Topic 3.3). A second was chartered in 1816, when it became clear that the country still needed a central bank.

Support for an opposition to the Bank of the

The Bank sat in the middle of the growing industrial revolution and Market Revolution, trying to ensure that nothing moved too fast. This was economically sensible,

but when it worked it made enemies of those who wanted to move fast—for example, people on the frontier who were seeking to make their fortune. However, when things went wrong, the Bank got the blame. In the financial crisis known as the Panic of 1819, many frontiersmen were ruined, and others also lost money. They blamed the Bank, pointing out that it had survived intact while they had suffered. Jackson, typically on the side of states’ rights, questioned whether the Bank was even constitutional because it tried to regulate smaller banks that were set up by individual states.

There was an argument in favor of a central Bank. It played an important role in the internal improvements and market expansions of the period from 1816 to 1829. It issued paper money to make sure that there was enough credit, and it called back its loans from state banks when it thought there was too much credit, preventing them from taking too many risks. It was economically important to have enough credit, so that improvements and commerce could happen when required. It was also important not to have too much, to prevent unwise speculation into projects that were not viable, which is what happened in 1819.

In 1823, Nicholas Biddle of Pennsylvania was appointed president of the Bank of the United States. Biddle was a capable administrator who recognized the need to have money circulating to build an economy based on producing goods—largely cotton—and getting them to the northeast, ready for export to the United Kingdom. He moved money around the country and stabilized trade.

The bank had foreign stockholders. Some people thought the Bank was not constitutional.

Some people thought the Bank was not constitutional.

State banks disliked being told what to do by the Bank.

This was not popular with those who did not benefit: people who farmed anything but cotton in the west, who would prefer “soft money” (easy access to credit), and laborers in the east, who preferred “hard money” (coins rather than the notes the Bank used, which might change in value). The Bank’s defenders pointed out that its energies were best focused on building the lucrative cotton economy. Its attackers remembered that they had lost money in 1819.

Panic of 1819: a financial crisis that lasted from 1819 to 1823; trade growth stopped, unemployment rose, and banks failed; speculation on western land collapsed, affecting many frontiersmen.

‘Hard Money’ men distrusted paper money, which the Bank produced.

‘Soft Money’ men liked easy credit, which the Bank prevented.

The Bank of the United States

The Bank gave money to particular politicians.

The bankers were elites, and not the common man.

Figure 4.4: Reasons for opposition to the Bank of the United States

Examine Figure 4.4. Were the reasons why the Bank was opposed primarily political, economic, or ideological? Make some notes to explain your answer, then get together in pairs to discuss your ideas.

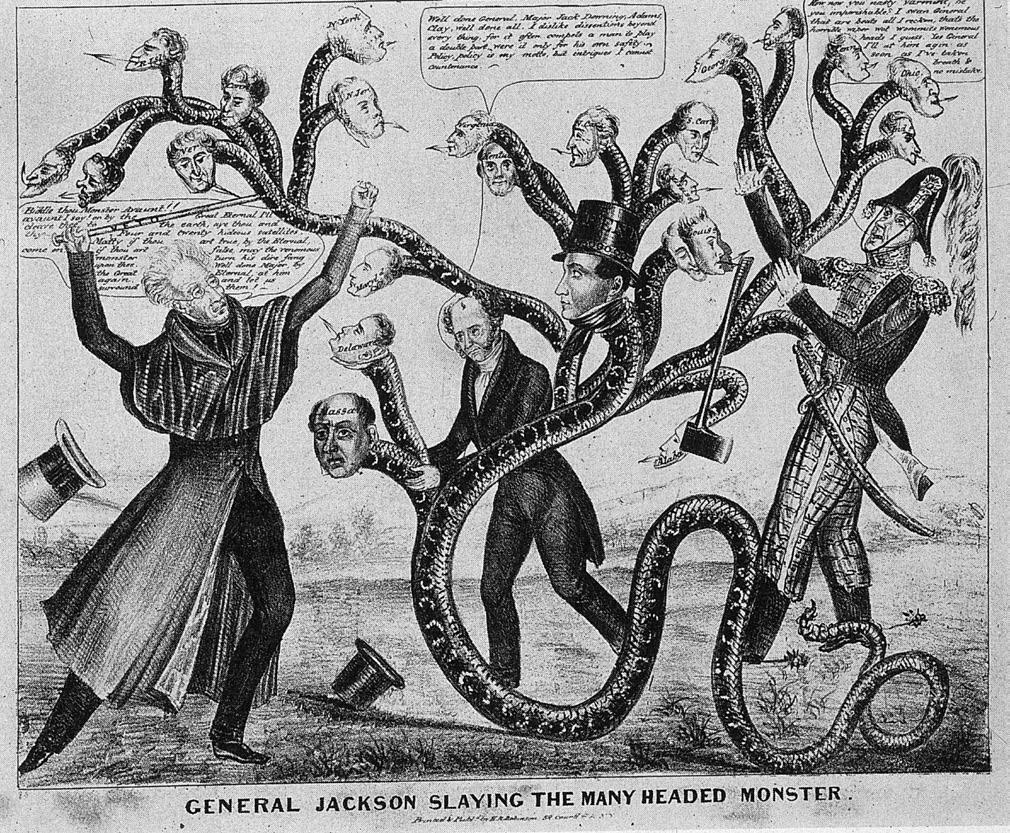

The Bank War was started by Henry Clay, Jackson’s opponent in the 1832 election, who thought that the issue of the Bank would be a winning campaign strategy. Clay persuaded Biddle to apply early for the Bank’s charter renewal, which was due in 1836. Steered by Clay, the request passed Congress, but Jackson vetoed it, sending a message that the Bank represented privilege, which stood in opposition to his own policies, which represented the common man.

Jackson had long suggested (probably unfairly) that the Bank had financed Adams’s campaign against him in 1828. Now the Bank really did step into presidential politics by financing Clay’s campaign. Jackson accused Congress of setting up a bank to interfere in elections and said that the Supreme Court had been wrong to confirm that the Bank was constitutional. Jackson won the 1832 election by a considerable margin.

Jackson instructed his Treasury Secretary, William Duane, to withdraw federal funds from the Bank, to make it harder for the Bank to operate. When Duane refused, Jackson simply replaced him with a man who would do his bidding, Roger Taney. When a recession came in 1836 (partly caused by Taney’s actions), Jackson called it “Biddle’s Pain.” On the basis of this, he built a reputation as the slayer of the Bank and any state banks that supported it.

Veto: to refuse to allow something to be done, especially to refuse to let a bill pass into law.

Recession: a period when the economy of a country is not doing well, when industrial production and business activity are at a low level, and many people are unemployed; the term is a modern one—before the Great depression of 1930, the word “panic” was used.

When a bill passes both the Senate and the House of Representatives, it is sent to the president to sign into law, which he must do within ten days. However, the president has the right to veto any bill by sending Congress a message to explain why he objects to it. Congress can attempt to override the veto and pass the law anyway, but it needs two-thirds of the House and two-thirds of the Senate to support an override.

Jackson’s veto of the Bank re-charter bill was groundbreaking because he used it to show that even when the Supreme Court had decided something was constitutional, it could still be challenged. The other vetoes that Jackson used reveal some interesting aspects of his presidency. He wrote extensive veto messages, and often wrote messages for his pocket vetoes too, although he was not obliged to. He did this to make his thinking clear, but also for a number of other reasons:

Pocket veto: an indirect refusal to sign a bill into law by simply ignoring it (putting it in a pocket) until the ten days have passed; this will cause the bill to fail as all bills must be resolved before the end of a congressional term; the president does not have to explain his objections to the bill and Congress cannot override a pocket veto.

• He wished the president to be able to set policy, not just Congress.

• He wished to communicate his ideas, not just to Congress but directly to the people.

• He wished to demonstrate that he was acting constitutionally (and therefore working on behalf of the people).

Table 4.1 summarizes Jackson’s vetoes and the reasons he gave for them.

DateVeto Reason

May 1830 Federal funding for the Maysville Road and for the Washington Road (two vetoes)

June 1830 Federal funding for the Louisville and Portland Canal Company (pocket veto)

June 1830 Federal funding for various local maritime projects (pocket veto)

The Maysville Road is entirely in Kentucky, and the Washington Road is entirely in Maryland.

It is unconstitutional for the government to invest in a private company.

Congress is suggesting local over-spending.

July 1832 Bank re-charter billThe Bank is not constitutional, even if the Supreme Court says it is.

July 1832 Federal government paying the states for debts incurred in the War of 1812 (pocket veto)

July 1832 Internal improvements in harbors and on rivers (pocket veto)

The interest on these claims was not calculated correctly.

Some of the improvements are not actually useful and conflict with the principle of earlier vetoes.

DateVeto Reason

July 1834

To improve the Wabash River (pocket veto)

March 1835 An attempt by Congress to control negotiations with the King of Two Sicilies

June 1836 Congress attempting to set the day when it meets every year

March 1837

Attempt to regulate the way in which debts could be paid

The Wabash River is entirely in Indiana.

Congress is interfering in the role of the Executive branch.

Congress cannot constitutionally bind future Congresses.

The bill is complex and uncertain and will not work.

March 1833 To redistribute public lands (pocket veto)

The price of the land is too high.

(Continued)

Jackson’s most common argument for vetoing bills was that they were unconstitutional. He also argued sometimes that they were too complicated, or that they would simply not work. Occasionally, he could not say what he really meant for a variety of reasons. For example, Jackson vetoed a series of bills focused on internal improvements. His two vetoes of May 1830—of the Maysville Road and Washington Road bills—set out one major objection, which was that he believed federal funds should only be spent on projects that affected more than one state. His next two vetoes, a month later, added further objections. First, any government, federal or state, should not be investing in a private body. Second, money should be well spent. He believed that the maritime funding bill of 1830 was a poor use of government funds because it seemed to direct them to particular representatives’ districts, and some of the spending programs did not seem useful.

By 1832, Jackson had started to refer back to his vetoes of 1830 to justify further vetoes. But he also gained in confidence when it came to expressing his own opinions. When vetoing improvements around the Wabash River in 1834, he gave his own policy on internal improvements as a reason. He was effectively telling Congress what he would allow to pass—the first president to try and make policy in this way.

Some of Jackson’s vetoes were about finance, such as the 1832 Bank veto and his veto the same month about the states’ war debts. He also vetoed a bill on the final day of his presidency about the acceptability of paper money.

All three of Jackson’s vetoes in 1832 should be seen as part of his battle with Henry Clay, the man who dominated Congress, and therefore part of the 1832 election campaign. However, they were also a statement that the president and not Congress should control policy-making. There was also a personal element: Maysville Road—the subject of Jackson’s first veto—would have passed close to, and been of great benefit to, Ashland, Clay’s home.

b Examine Figure 4.6. Do you think Jackson deserved to be called ‘King Andrew the First” because of his vetoes?

a Examine Table 4.1 and reread all the information about Andrew Jackson. For each of Jackson’s vetoes, discuss in small groups how far you trust Jackson’s stated reasons for vetoing the bill. Where you decide that he was being deceptive, why do you think he gave the reason he did for vetoing the bill?

Jackson was the first president to use the power of patronage as part of his political and electoral strategy. As the people’s president, he said that he was opposed to corruption, to the establishment, and to experts. As an example of this, during the 1828 presidential campaign, Jackson had said explicitly that he would replace prominent civil servants with the “common man”—in contrast to John Quincy Adams, who said he would not do so.

In fact, during his first term, Jackson removed only around one-fifth of the civil servants that he might have done, and a further quarter in his second term. Future Whig administrations would remove far more. He also appointed elites to important positions.

The idea of patronage was important in the 1820s and 1830s. The New York administration (known as the Albany Regency), one of whose members was Jackson’s supporter Martin van Buren, had used patronage to consolidate its power over the state. Early in Jackson’s presidency, New York senator William Marcy, a member of the Albany Regency, had defended Jackson’s actions in the Senate. Responding to an attack by Henry Clay, Marcy said that “To the victor belong the spoils of the enemy.” From this, patronage also became known as the “Spoils System,” although Jackson preferred to call it “rotation in office.”

Patronage: the idea that after a presidential or gubernatorial election, the victor offers his supporters positions in government, often removing existing office holders; patronage can be seen as a reward for support in the election campaign, or as a way of keeping allies on side after the election campaign.

Civil servant: someone who works for the local, state, or federal government.

Albany Regency: the name given to the group of Democratic politicians who systematically controlled the politics of New York from 1822 to 1837, culminating in the election of Martin van Buren as president.

It is useful to consider why previous presidents had not tried to change large numbers of federal officials. Four factors suggest what was different about the election of 1828, which brought Jackson to power:

• It was a highly contested election won by the antiestablishment candidate.

• It was the first time since 1801 that the incoming president had been opposed to his predecessor and been from a different party.

• As a consequence, many of the office holders Jackson had replaced had been in post for a long time.

• The USA was changing rapidly in terms of territorial expansion and internal improvements, and so were the jobs of federal office holders. Jackson saw patronage as a way to be more democratic, by giving more opportunities for people to take office and by reflecting the will of the people who had elected him. He started with the view that government officials were likely to be corrupt, and launched investigations into every federal department. He looked for—and found— officials to dismiss, both in Washington, DC and around the country, including several federal district attorneys. One position that was particularly associated with patronage under Jackson was that of Postmaster General, a cabinet position. The Postmaster General was in charge of most communications and of the distribution of newspapers. He was also in charge of the federal appointments system—and therefore of the system of patronage itself. He, therefore, wielded substantial power.

Usually, this position was retained by the same person, even under a change of president, but Jackson wanted an ally. William T. Barry, who took office a few days into Jackson’s first term, was, like the new president, an opponent of the Bank of the United States and a war hero. In 1835, Barry was replaced by Amos Kendall, a lawyer who had worked for Jackson in his first term, drafting presidential papers, and then as an auditor investigating the Treasury.

In the Nullification Crisis, Jackson was opposed by his own vice president, John C. Calhoun. As the crisis unfolded throughout 1832–33, the limits of American nationalism and the US Constitution were tested to the full. The Democratic Party was temporarily split apart, and the arguments made during the Nullification Crisis would ultimately be used to split the country too.

At the heart of the crisis was the Tariff of Abominations (see “Tariff of Abominations, 1828”). Tariffs in general, and this one in particular, tended to protect manufacturers above farmers. Most farming states with little in the way of manufacturing industries were in the South. One such state was South Carolina, whose most prominent politician was Jackson’s ally, Vice President Calhoun.

“Liberty

Jackson had run for office speaking against this tariff, and Calhoun had hoped he would reduce the tariff when he became president. However, it remained in force during Jackson’s first term—the president argued that while the tariff was a poor idea, it was constitutional. Calhoun and his state argued that the law setting up the tariff could be nullified by a Convention in South Carolina. This caused an open argument between the president and the vice president. In 1830, at an official dinner, Jackson led a toast to “Our Federal Union: it must be preserved.” Calhoun replied with a toast of his own: “The Union! Next to our Liberty, the most dear.” In a subsequent debate in the Senate, Daniel Webster would famously declare, “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable.”

Nullification: the idea that states can declare federal laws to be unconstitutional and can therefore ignore them.

There was a genuine constitutional argument at the heart of this, as well as an economic one. The tariff of 1828 was certainly bad for South Carolina, but could the federal government impose a tax that had such a negative impact on some of its states? Did the states not have rights in this situation? For Jackson, the key principle was that the people of the several states had given up their sovereignty to the federal government. He was an American nationalist, representing the American people, and the states would have to come second to that.

Jackson and Calhoun were both politicians, so they initially sought a political compromise, but in 1832, when the time came to pass another tariff bill or abandon tariffs altogether, this compromise broke down. The new tariff was less strict, but South Carolina was still not happy and Calhoun resigned as vice president to become a senator—a more powerful position—to oppose it. In February 1833, South Carolina refused to collect

federal tariffs and threatened to secession from the Union if the government tried to use force to collect them.

Secession: the act of leaving a government or organization, especially the decision of a state to separate from the US government.

In private, Jackson declared that he would personally lead the army into South Carolina and ensure that Calhoun was hanged, and warships were sent to Charleston Harbor. However, in public, Jackson worked with Congress to reduce the tariff. Calhoun and Clay, united in opposition to Jackson, worked together to prevent a split. The compromise they came up with allowed for a lower tariff, with the ability to raise it in a national crisis. South Carolina accepted the new tariff, but it nullified the Force Act, which was passed at the same time and which would have allowed the US to invade the state. Jackson let this lie. The Union was secure, but the threat of secession had paid off for South Carolina.

The Whig Party was created in opposition to Jackson and van Buren, and its first leading figure was Henry Clay. Clay had stood against Jackson in the election

of 1832 as a “National Republican,” the party of the American System that Clay supported (see “The American System”). The Whigs, as Clay’s party came to be called, took their name from the British political party that sought to limit the power of the monarch. It was intended to be a commentary upon the power of “King Andrew,” the nickname of President Jackson.

The Democrats formed to oppose Adams, and the Whigs formed to oppose Jackson. Broadly speaking, the Democrats were the party of immigrants, small farmers, and the west. The Whigs were generally seen as the party of business. Table 4.2 outlines some of the key policy positions of these two parties. In their early days, neither party dared to take a position on slavery.

Who should be more powerful, the President or Congress?

Who should be more powerful, the federal government or the states?

The President (who is elected by the “common man”) Congress

The statesThe federal government

Expansion or internal improvement? ExpansionInternal improvement

Bank of the United States OpposedIn favor

Soft or hard money?

Tariffs

Hard money (and limited debt)

Soft money (and easy credit)

Low (or none)High, for protection for American manufacturers

Table 4.2: Key policies of the Democrats and the Whigs

By the mid 1830s, the USA’s population was moving west, which meant new lines of communication were needed. Economically, it was necessary to send goods, messages, and finance back and forth across the country. Whose responsibility was this?

The Whigs believed in the American System—an economic plan designed to balance agriculture, industry, and business. They supported a high tariff to protect American industries and to generate revenue. They wanted high public land prices because this made money for the federal government when the land was sold. With a national bank to coordinate all this, the money could be used to build roads and canals around the country. The Democrats opposed the Bank and tariffs, as well as the idea that the federal government should interfere to make internal improvements to develop infrastructure.

The American System made sense for the manufacturing sector in the northeast of the country, because transportation links could get those goods out west. However, the South opposed the American System, not only because of the implications of tariffs (see “Divisions over tariffs”) but also because southern states did not need access to new markets. Without east–west canals and railroads, western traders had to use the Mississippi River, which emerged in New Orleans, in the Deep South. Internal improvements damaged the South. In the west there were two views. For Clay, western farmers could sell to hungry eastern workers, and buy their goods. For Jackson, the American System was unconstitutional as it took power from the states. While president, Madison had vetoed a plan for funding the National Road in 1817 for the same reason. Jackson also felt the American System was unwise because it gave power to corporations and increased debt.

The National Road, begun in 1815 and extending steadily westward, and the Erie Canal, finished in 1825, are examples of successful improvements. Adams sent the army to survey potential routes and locations for roads, canals, and—for the first time—railroads. Under Adams, nearly 100 internal improvement projects were built by federal soldiers, using federal money, including canals, harbors, and turnpikes.

Both Whigs and Democrats accepted that such infrastructure had to be developed, but who would pay, and where should they be? In the early 1840s, the economy was not strong enough to build much. Later in the decade, the Mexican–American War was the focus. From 1850, Whig president Millard Fillmore was willing to support infrastructure development including the Erie Railroad from New York to Illinois.

Jackson claimed that this was expensive and unconstitutional, and formed his policies (and therefore Democratic party policies) in response. As president, he vetoed several internal improvements bills, including those relating to Maysville and Wabash. However, he allowed most internal improvements bills to pass, as long as they were good value for money and did not take place entirely in one state.

The constitutional argument against a program of internal improvements was that the Constitution does not say that Congress can build canals or turnpikes. The 10th amendment states that anything the Constitution does not specifically allow is the right or responsibility of the states. If Congress was allowed to start building and expanding infrastructure, what else might it think it could do?

Even in the 1810s, in the lead up to the Missouri Compromise, there were nervous southern voices suggesting that Congress might think it could emancipate enslaved people. By the time of the Nullification Crisis, some southern politicians had become convinced that Congress would try to ban slavery, which was one reason why the principle of nullification and the threat of secession were important.

Generally, the Whigs favored federal over state power, and the Democrats favored the power of the states. Jackson’s view of the presidency was that because he owed his election to the people he (and only he) could override the will of the states. He used this during the Nullification Crisis as a nationalist argument that the Union should remain intact.

In opposing the Bank, Jackson took a similar attitude. Disagreements about money lay at the heart of arguments about federal and state power. In 1836, when the Treasury made a surplus, Jackson redistributed the money to the states, which caused an economic panic the following year.

Needing to take some action, and unable ideologically or politically to establish a Bank of the United States, in 1840 van Buren and Congress established an independent Treasury to control the money supply. This took three years of his presidency to achieve, only to be repealed by President Tyler the following year. Tyler refused to set up a new Bank of the United States, which Clay and other Whig leaders wanted. The independent Treasury was reestablished in 1846 by President Polk. The argument about federal and state power was resolved in a compromise, but it prolonged a decade of economic trouble.

Federal tariffs were designed to raise money for the federal government and to support American manufacturers. They were disliked by consumers, who had to pay more for goods, especially those who were not supported by the tariff in selling their own goods. The Whigs, who favored internal improvements, supported high tariffs. Whig supporters tended to include businessmen and factory owners, who benefitted from protectionist tariffs. Most Democrats opposed high tariffs.

Protectionist: describing actions that a government takes to help its country’s trade or industry by taxing goods bought from other countries.

The Tariff of 1828 (known as the “Tariff of Abominations”) imposed taxes of around 40% on imports of manufactured goods from Europe. This was good news for American manufacturers and factory owners, largely based in the northeast, as it meant their own products now faced less competition for sales. However, without cheap European competitors to drive down prices, farmers in the South had to pay more for their goods. The tariff prioritized northern manufacturing over southern agriculture.

In fact, Calhoun and van Buren had deliberately written the 1828 tariff bill in such a way that they were sure it would not pass, setting it up so that both northern and southern states would have to pay more for imports than they wished. They assumed that President Adams and his Secretary of State, Henry Clay, would be blamed for its failure. This would strengthen Jackson’s chances in the upcoming presidential election and damage the whole idea of high tariffs. But their plan backfired. Either recognizing that this was a political plot, or simply feeling that the principle of tariffs was too valuable to stand against, large numbers of northern congressmen voted for it and it became law.

The Nullification Crisis was only partly about tariffs, but its resolution did for a while fix the issue of how high tariffs should be. The 1833 Compromise Tariff, which addressed nullification, set a tariff rate of 20%, to be achieved by gradual reductions for the next ten years. Even when he reached a point where he was desperate for money, van Buren could not exceed this limit, because Calhoun had rejoined the party and van Buren did not want to alienate him and his supporters again.

Harrison, briefly, and then Tyler inherited the economic depression this caused. Tyler and the congressional Whigs, led by Clay, took a year to agree what to do. The tariff of 1842 raised many tariff rates to 40%. This partly addressed both the need for money and the need to protect American manufacturing, especially in ironmongery. The Democrats passed the Walker Tariff in 1846 to lower tariffs to 25%, which still made money but was not high enough to protect the iron industry. The two tariffs of the 1840s show that while the issue of protectionism remained a source of argument, both sides recognized that tariffs were needed to raise money.

This chapter has been cut part way through for sampling purposes

Essay-based question

Answer the questions below.

1 Explain why Andrew Jackson used his veto so often during his presidency. [10 marks]

2 To what extent were demands for women’s suffrage the most important priority of campaigners for women’s rights between 1820 and 1850? [20 marks]

1 Explain why Andrew Jackson used his veto so often during his presidency. [10 marks]

Jackson used his veto for two main reasons. One reason was because he believed that some of the bills proposed by Congress were not constitutional. He also wished to create political arguments that would help the Democrats to win elections.

Jackson believed that the Bank of the United States was not constitutional, which is why he vetoed the bill for it to be re-chartered in 1832. He believed that Congress was not constitutionally permitted to set up a national Bank. He believed that Congress could not pay for internal improvements that took place in only one state. This is why he vetoed the Maysville Road Bill in 1830. His veto messages show that he was concerned that Congress did not have the constitutional power to pass those bills. This also explains his pocket vetoes of internal improvement bills in 1830, 1832, and 1834.

This is a good response because it refers to half of Jackson’s 12 vetoes, and groups them together. It goes into a little detail about two of them. There would not be time to describe many more in a brief answer. It is also a good response because it focuses on explaining why Jackson used his veto. By referring to both straightforward vetoes and pocket vetoes, it shows good technical understanding.

There are two ways to improve the response. First, look at the question again. It asks why Jackson used his veto, and why he used it so often. There needs to be some comment on why he did this so frequently.

Second, consider the other way in which Jackson used his veto by thinking about his overall priorities. Jackson used his veto, and his veto messages, to try to lead policy-making as president. This was a genuinely new idea, and is part of his image of the president as the champion of the common man. There should be some discussion of this in an excellent answer.

Now, write your own response to this question.

Jackson’s veto of the Maysville Road Bill and his veto of the Bank created a clear difference between Jackson and his main opponent, Henry Clay, who had passed these bills through Congress. Jackson wanted to show that the Democrats wanted a small government that was careful with its spending on internal improvements. He also wanted to show that Democrats did not believe in national banks. These issues, especially the Bank, would be major issues in the 1832 and 1836 elections. Jackson thought correctly that they would be popular issues to campaign on.

After working through this chapter, complete the table.

You should be able to:

understand how and explain why politics changed from 1820 to 1850 in the USA

analyze the causes behind the wave of reform movements that emerged in the antebellum period from 1820 to 1850

assess the success of those reform movements consider why the debate over slavery intensified from 1820 to 1850.

Needs more work Almost there Ready to move on