LEARNING PACK

TRANSFORMATION IN THEATRE THROUGH DESIGN

Transform your thinking!

How do Designers work collaboratively with others to transform ideas onto the stage?

Learn about the different design roles – set, costume, props and lighting.

Follow the steps taken, through the design process.

in THEATRE Transformation

This pack will focus on the design aspects of MY FAIR LADY at Curve and will help you to transform your thinking and recognise the valuable part design plays in all production.

DESIGN and following the DESIGNER’S APPROACH for your assessment or exam, can be an exciting and creative way of engaging with the chosen TEXT you are studying or DEVISED DRAMA ideas you are exploring, in a group.

You will be using a variety of skills like CRITICAL THINKING, COMMUNICATION, CREATIVITY and COLLABORATION. Additionally, you will be using your PROBLEM-SOLVING skills right from the start, so that you can select from the different ideas and possibilities you might be thinking about.

TRANSFORMATION DEFINITION (NOUN)

A COMPLETE CHANGE in the APPEARANCE or CHARACTER of something or someone, especially so if that thing is IMPROVED or MADE DIFFERENT

Synonyms: change, later, vary, convert, turn into, modify, adapt, evolve

DEFINITION OF DESIGNER’S IN THEATRE

THEATRE DESIGNERS

Lighting Designer Sound Designer

Set Designer Costume Designer

Props, Wigs and Make-up Designer

The design team are often brought together by the Director of a production and will work closely together to help deliver the director’s vision. Some of their work may be done in advance of rehearsals, but they will often continue to work on a show until it opens.

They will determine the type of space the characters will inhabit and help to engage an audience to the story. They will help decide, what costume they will wear, suitable props and objects to use, the mood, tension and atmosphere being portrayed through lighting, sound, music and special effects.

TRANSFORM YOUR THINKING!

Complete your own research into a specific area of design for theatre, that interests you. What can you find out about experienced theatre designers? Create a fact sheet to demonstrate your learning.

As a DESIGNER, you will need to be clear on:

The CONTEXT of the production.

Transformation

THEATRE

To create a show like MY FAIR LADY, the very first step in the process lies with the writers of the play. The design team needs to work in COLLABORATION with each other and the DIRECTOR

To realise the directors VISION and INTENTION, they will explore a range of ideas that can TRANSFORM the space and what the AUDIENCE, SEES, HEARS and EXPERIENCES, to help communicate the story.

This will include HISTORICAL, SOCIAL, CULTURAL and POLITICAL aspects.

Read the RESEARCH INFORMATION for MY FAIR LADY at the back of this pack. How does this help you to start forming your own design ideas?

WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT BEING A DESIGNER?

• Research the descriptions, definitions and roles of the different designers used in theatre. Write it in your own words, making it clear how their role adds to the process of putting a show together.

• Start with BBC Bitesize Drama, for the different exam boards, or a Google Search on Design Roles in Theatre. https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/subjects/zbckjxs

• Look at the website for The National Theatre, what does it tell you about any theatre roles and training for young people? https://www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/learn-explore/young-people/

• Look at the website for your local theatre, like Curve theatre. Explore the links to careers and roles you have at a theatre. https://www.curveonline.co.uk/about-us/meet-the-team/our-departments/ https://www.curveonline.co.uk/about-us/careers/

• Know more about the theatre roles and routes into theatre, by navigating the website Get Into Theatre. https://getintotheatre.org Home - Get into Theatre

Complete the boxes below with a DESCRIPTION or DEFINITION for each Design Role.

Set Designer

What other design roles in theatre, not shown here, are part of the design process?

Costume Designer

Lighting Designer

Sound Designer in

Photography: MARC BRENNER

Designer Michael Taylor drew on the real-life arches and pillars that can be seen in the architecture of Covent Garden and St Paul’s cathedral in London. Read more about this in the Research page London in MY FAIR LADY.

SET DESIGN

in THEATRE Transformation

A SET DESIGNER’s primary focus will be how they can transform the performance space, to support the story being told. Their decisions will be informed by the research undertaken, discussions with the PLAYWRIGHT (if it is a new or contemporary text) DIRECTOR and other members of the CREATIVE TEAM. They will read the script, annotate what action is taking place: When? Where? Time of day? and how the most important moments in the play, can also be captured through the SET and PROPS design choices.

Initial white card ideas.

The transformation begins here, in Covent Garden, Eliza’s place of work and where Higgins, Pickering and Eliza first meet. Informed by the research that reflects the time, people and architecture.

An abstract idea to bring into the space elements of Professor Higgins and his world, if there wasn’t a full scene change.

We see the ideas have developed further, by showing more detail of the props and people that will inhabit the space and movement within it.

The use of a higher level will sweep characters off to bed, but also signal an important turning point in Eliza’s arc of transformation and realisation, when she and Higgins argue.

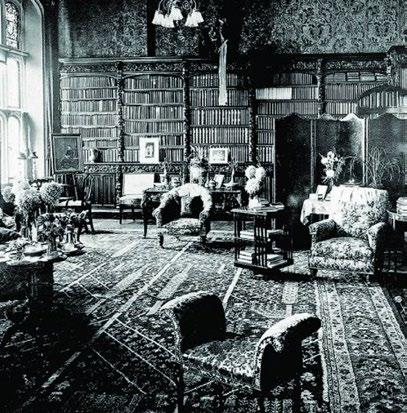

The home and study of Professor Higgins is brought forward for the action.

We see his world of books, education and a wellguarded bachelor space.

Seeping through, as if to interrupt this sanctuary are the towers, gate and grandeur of Covent Garden. Reminding the audience of the context of our protagonist.

Additionally, columns, props and paraphernalia of Covent Garden is expressed here and shows the occupants busy lives and encounters, within the area. This is a design decision to let the action fall out, across and towards the audience as if inviting them into the action.

MODEL BOXES AND WHY ARE THEY USED

A white card model is the original version of the model box and set design, made by the Designer, it is made using white card.

There will be stages of model boxes that will be shared with the director and design team, so that everyone is clear on how it will look and work on stage. If things are not working, it is easier and more cost effective to fix any challenges at this stage.

The final model box will be made in full colour and may have different materials and textures to demonstrate what will be used. Furniture and figures of the actors will also be used, so that you can get a better sense of scale and how things will work, as you move through set changes.

TRANSFORM YOUR THINKING

Research Model Boxes, what materials are used and the dimensions used (which tend to be 1:25 scale), why not have a go at creating one yourself! Below are the Model Boxes used for the production of MY FAIR LADY.

The full scope of the space and how it fills, spills out and into the auditorium, is demonstrated here. As well as how company members can be grouped and staged for particular scenes.

We can also see the depth and breadth of the space and the opportunity for ensemble pieces to ‘With a Little Bit of Luck’ and ‘I’m Getting Married in the Morning’, raucous dances and singing!

FINAL MODEL BOX

“These early white card model pictures from our MY FAIR LADY Designer Michael Taylor, are playing with two main spaces – the expanse of the open stage for the epic exterior scenes to facilitate the big musical numbers, framed by the iconic Covent Garden ironwork and the intimate, interior-set traditional musical comedy scenes, which take place in Higgins’ study. The production will be set in 1912, and Michael’s costumes will be as sumptuous as the film!” Director Nikolai Foster

WHITE CARD BOX DESIGN

Photography: JONATHAN PRYKE

MICHAEL TAYLOR

Set and Costume Designer for MY FAIR LADY

Training: RADA

Michael started out by training as a designer at RADA and then working as assistant to the theatre and opera designer John Gunter. Michael’s design for THE LADYKILLERS was nominated for an Olivier Award and a Whatsonstage Award. He was one of four designers included in The Stage 100 of 2013 “our annual power list, detailing the theatre and performing arts industry’s most influential individuals”. He won the Drama Magazine Best Designer Award for Tony Marchant’s THE ATTRACTIONS, and has been nominated for six other awards.

Previous Curve theatre credits include: EVITA; BILLY ELLIOT THE MUSICAL and WEST SIDE STORY.

in THEATRE Transformation

MICHAEL TAYLOR’S 5 TOP TIPS FOR A THEATRE DESIGNER

A stage set is a place. It is a location we can believe in where the actors tell a story. It’s not a concept or an abstract arrangement, it has to create a real place even if the place is created almost entirely in the audience’s imagination by what the set has put there. Normally the set doesn’t present the whole location but there is enough there to start the audience imagining the rest.

Create an atmosphere: Think of atmospheric places you have seen or seen photos of: trees in mist, wet streets at night, deserted buildings, empty skies, sunshine coming through trees, a room lit only by a desk lamp.

If the play is set in a particular time and place, research, in books or online what the place would look like. If you find images that look beautiful in your research, work out how to evoke that in what you design.

Any artistic skills you have will be useful, others you can learn. Set Designers need to be good at making models, it helps if you can draw but if not you can teach yourself. Other useful skills are CAD drawing, Photoshop, and being good at maths – BUT NO SINGLE SKILL IS ESSENTIAL.

Get all the experience you can by offering to help when plays are being put on, school, college, professional, amateur or wherever. Go to the theatre or watch the NT Live films of successful productions when they come on in the cinema. Enjoy it

Scan this code or click on the image below to see an interview with Set and Costume Designer

Michael Taylor and Artistic

Director Nikolai Foster.

Photography:

Costume Supervisor Hillary Lewis worked with Michael Taylor, the Designer on MY FAIR LADY to create the stunning range of costumes the demonstrated the stark divide between the classes. It is interesting to note how Eliza’s progression through the play is reflected in how the costume choices develop alongside her own transformation.

TRANSFORM YOUR THINKING

Research the role of a Costume Supervisor.

Photography: MARC BRENNER

in THEATRE Transformation

COSTUME DESIGN

Choose a particular character in the play or production that you are designing for.

Transform your thinking: What do know about them? What they do and who they interact with in the production will help you make choices about their costume.

Create your own design and then annotate it to explain and justify your thinking.

This is an opportunity to link it back to your research and all the information you acquired about the production and its context.

in THEATRE Transformation

COSTUME DESIGN

Think about their… Age Time period / era the production is set in

Textures

Layers or other garments they might have to put on

Shoes or footwear

Hat or headdress

Remember they will be on stage, so the materials need to be breathable and will not restrict their movements.

Choose a particular character in the play or production that you are designing for.

Transform your thinking: What do know about them? What they do and who they interact with in the production will help you make choices about their costume.

Create your own design and then annotate it to explain and justify your thinking.

This is an opportunity to link it back to your research and all the information you acquired about the production and its context.

Think about their… Age

Time period / era the production is set in

Colours

Patterns

Textures

Layers or other garments they might have to put on

Shoes or footwear

Hat or headdress

Remember they will be on stage, so the materials need to be breathable and will not restrict their movements.

DEFINITION OF A MOOD BOARD

in THEATRE Transformation

AS A DESIGNER…

Create a Mood Board that demonstrates a range of ideas for the production that links to the research you’ve read and carried out.

A mood board is used to help the artist or designer with inspiration for their work. They may have been given a brief, a specific text or stimulus, as their instructions to follow or explore.

They will fill the board with a collection of their ideas, thoughts, drawings, photos, images and any visual elements that help to convey the required mood or interpretation of the ideas outlined to them. This will be a collage; it can have colour and texture to it.

It can help you to narrow down your ideas, ask questions or clarify what the overall concept and vision could be, in collaboration with the rest of the design team and director.

Costume can be used to tell us what is important about different characters and their backgrounds. Consider how Colonel Pickering’s costume choices are informed by his Indian heritage.

TRANSFORM YOUR THINKING

Find some examples of mood boards that will inspire you to create your own, some examples are shown below. Talk through your ideas with someone, how does it connect to the brief given? and how will you justify your interpretation and ideas?

This can be as a SET, COSTUME, LIGHTING or SOUND DESIGNER

Photography:

Photography: MARC BRENNER

in THEATRE Research

Flower Sellers Transformation

In Edwardian London, women were able to make a living selling flowers. Earlier fashions had favoured expensive flowers from abroad, but the new preference for local flowers like primroses and nosegays meant that the opportunity to work selling flowers was available for girls and young women in need of unskilled employment. Typically flower sellers began as children due to orphanhood or to supplement the family income. The amount these girls could expect to make was low – one orphaned girl told documenter Henry Mayhew that she made around sixpence a day. The girl explained she and her sister and a brother who was also working, lived on a diet of bread, tea and the occasional herring.

The flower sellers were also recorded by journalists as either selling in the day or night. Those who sold in the day were seen as the more virtuous as those who sold at night were understood to be selling more than flowers. In fact, the term flower girl ultimately became synonymous with prostitute. However, the result was that the night sellers could make around £3 a week, while those who sold only during the day might only make ten shillings.

One flower seller, as recorded by Henry Mayhew, recounted being sent out by her parents at age nine to sell flowers and would rarely be home before midnight. Eventually, by the age of 13, neither her father nor mother worked, relying solely on the money their daughter made through prostitution. At the time of speaking to Mayhew she had taken to committing crime in the hope of being placed in a prison or an asylum, being “tired of her life.”

Adolphe Smith documented that “In the summer months more than a pound in profits have been cleared in a week; but in bad weather these women have often returned home with less than a shilling as a result of twelve hours exposure to the rain.”

The flower sellers were often seen as being largely single, however there are also reports that many were in unofficial marriages or partnerships. In those cases, the women often found themselves having to support a jobless man as well as themselves. The result of this hard life of poverty and of traipsing the streets in all weathers meant that flower sellers aged quickly. What little money they had was often enjoyed in pubs.

With flower selling women suffering both extreme poverty and representing moral ambiguity, some charities hoped to place the girls and women in the industry into more structured employment, with service being the primary focus. However, service meant long hours, low pay and being isolated in the house of your employer. It was not an attractive proposition, even given the poverty these women and girls were living in.

One of the last street flower sellers in London was Agnes Pegg who sold violets in Piccadilly Circus until the 1970s.

Photography:

EDWARDIAN LONDON

World of the Play

The years between Queen Victoria’s death in 1901 and the start of the First World War in 1914 were years of growth and prosperity, though the extreme inequalities which had characterized Victorian London continued. London was a bustling and evolving metropolis, the centre of an expansive and extractive empire that moved wealth, materials and people across the globe. The capital was home to elites who opulently dominated this world, as well as immigrants, workers and women who all faced oppression as they struggled to live with dignity in the city. By 1900 one out of five Britons lived in London, with the population of roughly 5 million in 1900 rising to over 7 million by 1911.

Edwardian London was often a city of conflict, characterized by the burgeoning Women’s Suffrage movement, as well as various workers’ strikes. The city became the epicentre for the nationwide suffrage movement spearheaded by Emmeline Pankhurst and her Women’s Social and Political Union.

Protests and demonstrations reached a peak between 1912 and 1914 as the movement militarized. Hyde Park hosted two major suffragette rallies in 1908 and 1913, the former counting over 250,000 attendees.

London in My Fair Lady

COVENT GARDEN

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin’s Lane and Drury Lane. In 1912, there was a fruit and vegetable market in the central square. The Royal Opera House, located on the side of the square, is itself known as “Covent Garden.” The central square is famous for street performers, historical buildings, theatres and entertainment facilities, including the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane.

The first major building in the square was under architect Inigo Jones, in the 17th century. It is the first regularly planned square in London, and included the construction of St Paul’s, designed in the model of a classical Italian church, with its iconic columns.

By 1654 a small open-air fruit-and-vegetable market in the square. Over the following centuries, the market grew, became organized and buildings were added, such as the Floral Hall, Charter Market, and in 1904 the Jubilee Market. In the 18th century, Covent Garden had become a well-known red-light district, but by 1912 it had been reorganized and gain gained a reputation for its markets, taverns and theatres.

A Victorian iron and glass building on the east side of the market square was designed as a dedicated flower market by William Rogers of William Cubitt and Company in 1871.

ROUND ABOUT A POUND A WEEK was an influential 1913 survey of poverty and infant mortality in London, by feminist and socialist Maud Pember Reeves. It describes the lives of the “respectable poor”: one in five children died in their first year, and hunger, illness, and colds were the norm.

Urban Poverty Life of members of the Working Class

A 1909 report of the Poor Law Commission found that one-third of the East End’s 900,000 strong population lived in conditions of extreme poverty. The report also detailed the squalor of conditions in these areas, with an average of 25 houses sharing one lavatory and fresh water tap between them. One response to a dire lack of sanitation in London’s poorest areas was the provision of communal washhouses for bathing and clothes-washing; an average of 60,000 people each week used the 50 such bathhouses which existed across the city in 1910.

The publication of the third edition of Charles Booth’s monumental 17-volume LIFE AND LABOUR OF THE PEOPLE OF LONDON gave further insight into the conditions of London’s poorest. From 1900-1940, the London County Council continued a program of slum clearance and the building of “model dwellings” in the poorest areas like Spitalfields, Whitechapel and Bethnal Green.

Poor Londoners were condemned to live in densely populated, unsanitary and polluted slums while the middle-classes could move to the expanding suburbs for fresh-air and space. Such conditions made those born and raised in London’s slums noticeably unhealthy, weak, and malnourished in appearance. Recruitment drives for the Boer War of 1899-1902 revealed that 7 in 9 working-class Londoners were unfit for service.

Whilst 1912 saw certain improvements in living conditions and some labour reforms, life was still hard, and poverty rates remained high.

At the beginning of the 20th century, 25% of the population of Britain was living in poverty. At least 15% were living at subsistence level. They had just enough money for food, rent, fuel, and clothes. They could not afford ‘luxuries’ such as newspapers or public transport. About 10% were living below subsistence level and could not afford an adequate diet.

The main cause of poverty was low wages. The main cause of extreme poverty was the loss of the main breadwinner, e.g. if fathers died or became ill/unemployed. Women were paid much lower wages than men.

Poverty tended to be cyclical. Working-class people might live in poverty when they were children, but things usually improved when they left work and found a job. However, when they married and had children things would take a turn for the worse. Their wages might be enough to support a single man comfortably but not enough to support a wife and children too. However, when the children grew old enough to work things would improve again. Finally, older workers would find it hard to find work, and be driven into poverty again.

Middle Class Life for the Life for the Upper Class

In 1912, only about 20% of the population of Britain was middle class. (To be considered middle class you would normally need to have at least one servant). The Upper Class lived in very comfortable houses. However, middle-class homes would seem overcrowded with furniture, ornaments, and knick-knacks.

Gas fires became common in the 1880s. Gas cookers became common in the 1890s. The electric light bulb was invented in 1879. By 1912, most towns had electric streetlights. However, at first electric light was expensive. In 1912 most middle-class families still used gas for lighting their homes. Middle-class people in Britain usually had bathrooms. The water was heated by gas.

Games like lawn tennis and snooker, and Board games like snakes and ladders and ludo were also popular. Bicycling was a popular sport. Reading was also popular, with novels published by authors such as Arthur Conan Doyle and H G Wells.

The middle-class often enjoyed the theatre. The cinema was also a new pastime, although films were silent and in black and white.

Middle-class children in Britain owned plenty of toys, such as wood or porcelain dolls and toys like Noah’s arks with wooden animals. Plasticine was invented in 1897 by William Harbutt. It was first made commercially in 1900. Also in 1900, Frank Hornby invented a toy called Meccano.

Edwardian London was dominated by a fashionable elite, that set a style influenced by the art and fashions of continental Europe. For them, it was a “leisurely time when women wore picture hats and did not vote, when the rich were not ashamed to live conspicuously, and the sun never set on the British flag.”

The Liberal Government formed in 1906 and made significant reforms. Below the upper class, the era was marked by significant shifts in politics among sections of society that had largely been excluded from power, such as labourers, servants, and the industrial working class. Women started (again) to play more of a role in politics. Whilst the aristocracy maintained control of top government offices, the elite became increasingly conscious of the instability within the inequal British class system, and was heading blindly towards the world-changing disruption of the First World War.

The Edwardian period is sometimes portrayed as a romantic golden age of long summer days and garden parties, basking in a sun that never set on the British Empire. This perception was created in the 1920s and later by those who remembered the Edwardian age with nostalgia, looking back to their childhoods across the abyss of the Great War. The British Elite felt increasingly threatened by rival powers such as Germany, Russia, and the United States.

The engine of the British elite was the manor house, which represented a world of privilege, inequality, extravagance and power. This world was inhabited by an elite class of people who claimed descent from medieval nobles, whose titles and land were bestowed on them by a grateful king. For over a thousand years, aristocrats viewed themselves as a race apart, their power and wealth predicated on titles, landed wealth, and political standing.

Life for the Servant Class Upper Class Life for the

Vast landed estates were their domain, where a strict hierarchy of class was followed above stairs as well as below it. In 1912, 1.5 million servants tended to the needs of their masters. As many as 100 would be employed at one manor as butler, housekeeper, house maids, kitchen maids, footmen, valets, cooks, grooms, chauffeurs, forestry men, and agricultural workers.

Manderston House in Berwickshire, for example, consisted of 109 rooms, and employed 98 servants. It was renovated at the turn of the 20th century for 20 million dollars in today’s money.

The Edwardian elite lived extravagant, indulgent lives of relaxation and pleasure, attending endless rounds of balls, shooting parties, race meetings, and dinner parties. The landed rich possessed over one half of the land in the country. Their power was rooted in land ownership and rent from those who lived on their large estates. The landed gentry also received income from investments, rich mineral deposits on their land, timber, vegetables grown in their fields, and animals shipped to market.

The eldest son inherited everything – the estate, title, all the houses, jewels, furnishings, and art – to ensure that country estates would not be whittled away over succeeding generations. Entailment, a law that went back to the 13th century, ensured that portions of an estate could not be sold off.

Only men who owned land could vote, and hereditary peers were automatically given a seat in the House of Lords. By inviting powerful guests to their country estates, they could lobby for their special interests across a dinner table, or at a men’s club.

The Industrial Revolution brought about changes in agricultural practices and inventions that presaged the decline of aristocratic wealth, as well as cheaper imports from Australia and the U.S. Individuals were able to build wealth in other ways – as bankers and financiers.

Contrasted with the opulent life above stairs was the machine of labour and service that sustained it. On a large estate that entertained visitors, over 100 meals were prepared daily. Servants rose at dawn and had to stay up until the last guest went to bed. Kitchen maids, who made the equivalent of 28 dollars per year, rarely strayed outside the kitchen. The kitchen staff worked 17 hours a day and rarely left the kitchen.

Scullery maids were placed at the bottom of the servant hierarchy. They rose before dawn to start the kitchen fires and put water on to boil. Their job was to scrub the pots, pans and dishes, and floors, and even wait on other servants.

One bath required 45 gallons of water, which had to be hauled by hand up steep, narrow stairs. At times, a dozen guests might take baths on the same day. House maids worked quietly and unseen all over the manor house. The were expected to move from room to room using their own staircases and corridors.

As revenues from agriculture dwindled, the upper classes searched for a new infusion of capital, which they found in wealthy American heiresses. The ‘Buccaneers,’ as they were called, infused the British estates with wealth. ‘Cash for titles’ brought 60 million dollars into the British upper class system via 100 transatlantic marriages.

Edwardian elites would also own ‘town houses’ in London, as well as their estates, to facilitate their movement for social and political events.

Maids and footmen lived in their own quarters in the attic or basement. Men were separated from the women and were expected to use different stairs. Discipline was strict. Servants could be dismissed without notice for the most minor infraction.

Footmen, whose livery (uniform) cost more than their yearly salary, were status symbols. Chosen for their height and looks, they were the only servants allowed to assist the butler at dinner table. These men were the only servants allowed upstairs.

Inventions revolutionized the workplace. Electricity, telephones, the typewriter, and other labour-saving devices threatened jobs in service. A big house could be run with fewer staff, and by the 1920s a manor house that required 100 servants needed only 30-40. Women who would otherwise have gone into service were lured into secretarial jobs, which had been revolutionized by the telephone and typewriter.

Act One

Synopsis

1912. London. Eliza Doolittle is a flower girl with a thick Cockney accent. The renowned phonetician Professor Henry Higgins encounters Eliza at Covent Garden and laments the vulgarity of her dialect (Why Can’t the English?). Higgins also meets Colonel Pickering, another linguist with a specialism in Indian dialects, and invites him to stay as his houseguest. Eliza and her friends wonder what it would be like to live a comfortable life (Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?).

Eliza’s dustman father, Alfred P. Doolittle, stops by the next morning searching for money for a drink (With a Little Bit of Luck). Soon after, Eliza comes to Higgins’s house, seeking elocution lessons so that she can get a job as an assistant in a florist’s shop. Higgins wagers Pickering that, within six months, by teaching Eliza to speak properly, he will enable her to pass for a proper lady.

Eliza becomes part of Higgins’s household. Their time together makes Higgins reflect on his relationship with women (I’m an Ordinary Man). Eliza endures Higgins’s tyrannical speech tutoring. Frustrated, she dreams of different ways to kill him (Just You Wait). Higgins’s servants lament the stressful atmosphere (The Servants’ Chorus).

Late one morning, Eliza suddenly recites one of her diction exercises in perfect received pronunciation (The Rain in Spain). Though Mrs Pearce, Higgins’ housekeeper, insists that Eliza go to bed, she declares she is too excited to sleep (I Could Have Danced All Night).

For her first public tryout, Higgins takes Eliza to his mother’s box at Ascot Racecourse (Ascot Gavotte). Though Eliza shocks everyone when she forgets herself while watching a race and reverts to foul language, she does capture the heart of Freddy Eynsford-Hill. Freddy calls on Eliza that evening, and he declares that he will wait for her in the street outside Higgins’ house (On the Street Where You Live).

Eliza’s final test requires her to pass as a lady at the Embassy Ball. After more weeks of preparation, she is ready. (Eliza’s Entrance). As Higgins, Pickering and Eliza arrive at the Ball, the curtain falls.

Act Two

At the ball, Eliza is admired by all the attendees, including the Queen of Transylvania (Embassy Waltz). A Hungarian phonetician, Zoltan Karpathy, attempts to discover Eliza’s origins.

The ball is a success. Pickering and Higgins revel in their triumph (You Did It). Eliza is insulted at receiving no credit for her success, packing up and leaving the Higgins house. As she leaves, she finds Freddy who begins to tell her how much he loves her. Eliza tells him that she has heard enough words, and that if he really loves her, he should show it (Show Me).

Eliza and Freddy return to Covent Garden but she finds she no longer feels at home there. Her father has received an unexpected inheritance, which has raised him to middle-class respectability, and so he is finally getting married.

Doolittle and his friends have one last spree before the wedding (Get Me to the Church on Time).

Higgins is upset to find Eliza has left and tries (without success) to rationalize her actions (A Hymn to Him).

Higgins despondently visits his mother’s house, where he finds Eliza. Eliza declares she no longer needs him (Without You). As Higgins walks home, he begins to realize the extent of his feelings for Eliza (I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face). At home, he sentimentally reviews the recording he made the day Eliza first came to him for lessons, until Eliza suddenly appears…

Writers

LERNER & LOEWE

Lyricist and librettist Alan Jay Lerner was born in NYC and first wrote for college musicals at Harvard. Composer Frederick Loewe grew up in Austria as a child prodigy concert pianist, before moving to NYC where he worked as a pianist in clubs and an accompanist for silent films.

The pair met in August 1942 in New York City, and whilst their initial two musicals were not a commercial success, they would go on to write BRIGADOON (1947), MY FAIR LADY (1956), and CAMELOT (1960), along with the musical film GIGI (1958). Lerner also achieved success on projects outside the partnership, including his screenplay for the 1951 film, An American in Paris, and collaborated with other writers after Loewe’s retirement.

The two were partial to working in the early morning, particularly Lerner, who believed all his best writing was done as soon as he awakened. Lerner often struggled with writing his lyrics. He was uncharacteristically able to complete “I Could Have Danced All Night” from My Fair Lady in one 24-hour period. He usually spent months on each song and was constantly rewriting them. Loewe could often be very uncertain in his choices and Lerner was able to provide him with reassurance.

GEORGE BERNARD SHAW

1856-1950. Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. He wrote more than sixty plays, including major works such as MAN AND SUPERMAN (1902), PYGMALION (1913) and SAINT JOAN (1923). With a range incorporating both contemporary satire and historical allegory, Shaw became the leading dramatist of his generation, and in 1925 was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Influenced by Henrik Ibsen, he sought to introduce a new realism into English-language drama, using his plays as vehicles to moralize and disseminate his political, social and religious ideas. Shaw’s expressed views were often contentious. He promoted eugenics and alphabet reform, and opposed vaccination and organised religion. In his will, Shaw ordered that his remaining assets were to form a trust to pay for fundamental reform of the English alphabet into a phonetic version of forty letters, an alphabet he invented and named after himself. He was also a friend of phonetician Henry Sweet.

in THEATRE Transformation THROUGH DESIGN