H I R U M A K A Z U Y O

Hiruma Kazuyo (b 1947), a former graphic designer who didn’t start her own kiln until she was 40 years old, drew early inspiration from two pioneering women artists of the previous generation: Araki Takako (1921–2004) and Tsuboi Asuka (born 1932). Leading lights in the Joryū Tōgei (Women’s Association of Ceramic Art) group, both were already established figures when Hiruma herself first garnered critical attention by winning the Mainichi Newspaper prize at the group ’ s 1979 exhibition. As Hiruma recently recalled:

At the time, the vigorous assertiveness of their work—created in an era when women could at last stake their claim to a place in the world of contemporary ceramics—made it seem that Araki and Tsuboi were literally putting their very lives on display. More than that, even today I can still vividly recall the profound effect their ceramics had on me when I saw them for the first time. I was both shocked and surprised at their capacity to imbue objects formed from clay with such expressive power.

Araki’s use of paper-thin sheets of porcelain to create her celebrated Bible series finds a visual

parallel in Hiruma’s sekisō (laminar) technique that emulates the repeated cycles of sedimentation and erosion seen in some of America’s most iconic landscapes More significant, perhaps, is the biographical or autobiographical intent of both women ’ s practice. Araki deployed those porcelain

J O E E A R L E

8

Hiruma Kazuyo in her studio workspace, 2024

sheets as a tribute to her deceased brot commentary on religious faith, while Hiru style is the outcome of a life-changing, q experience during a two-week visit in the Arizona, a place she’d previously seen on photographs:

Dark brown earth, dry sand and wind row upon row of surf-like forms that s have been pulled from Earth’s core, c processes by which living creatures h down to the present: a testament to li transported from beyond a now-invisi uniformly skin-toned landscape that m doubt our importance as denizens of t After offering up a prayer to the gods ancestors once worshiped on this ver my leave.

Following this revelatory encounter, Hiruma started work on Daichi no Kioku (The Earth Remembers),

Hiruma Kazuyo 昼⾺和代, Aflojar ゆるぐ, 2017, stoneware, 18 7/8 × 22 7/16 × 15 3/4 in

Suibun ni kansuru kioku (Memories of Moisture), and other series that have defined her subsequent practice

In contrast to some contemporary women ceramic artists who view their encounters with clay as a search for its inner nature or a struggle with unpredictable outcomes, Hiruma speaks of an intricate process through which the material is bent to her will She makes her own mixtures, using different colors for different effects from skin tones to dry grays and conveys a sense of the passage of geological time by applying multiple, thin layers of heat-resistant clay that present a wavelike appearance when they’re eventually glazed and fired, several times

9

Araki Takako 荒⽊⾼⼦, Degeneration Bible, 1993, porcelain, 7 × 17 × 14 in Image courtesy The Everson Museum of Art (Gift of the artist), 93.16

10

Dark brown earth, dry sand and wind on my cheeks, row upon row of surf-like forms that seemed to have been pulled from Earth’s core, concealing the processes by which living creatures had come down to the present...

– Hiruma Kazuyo

11

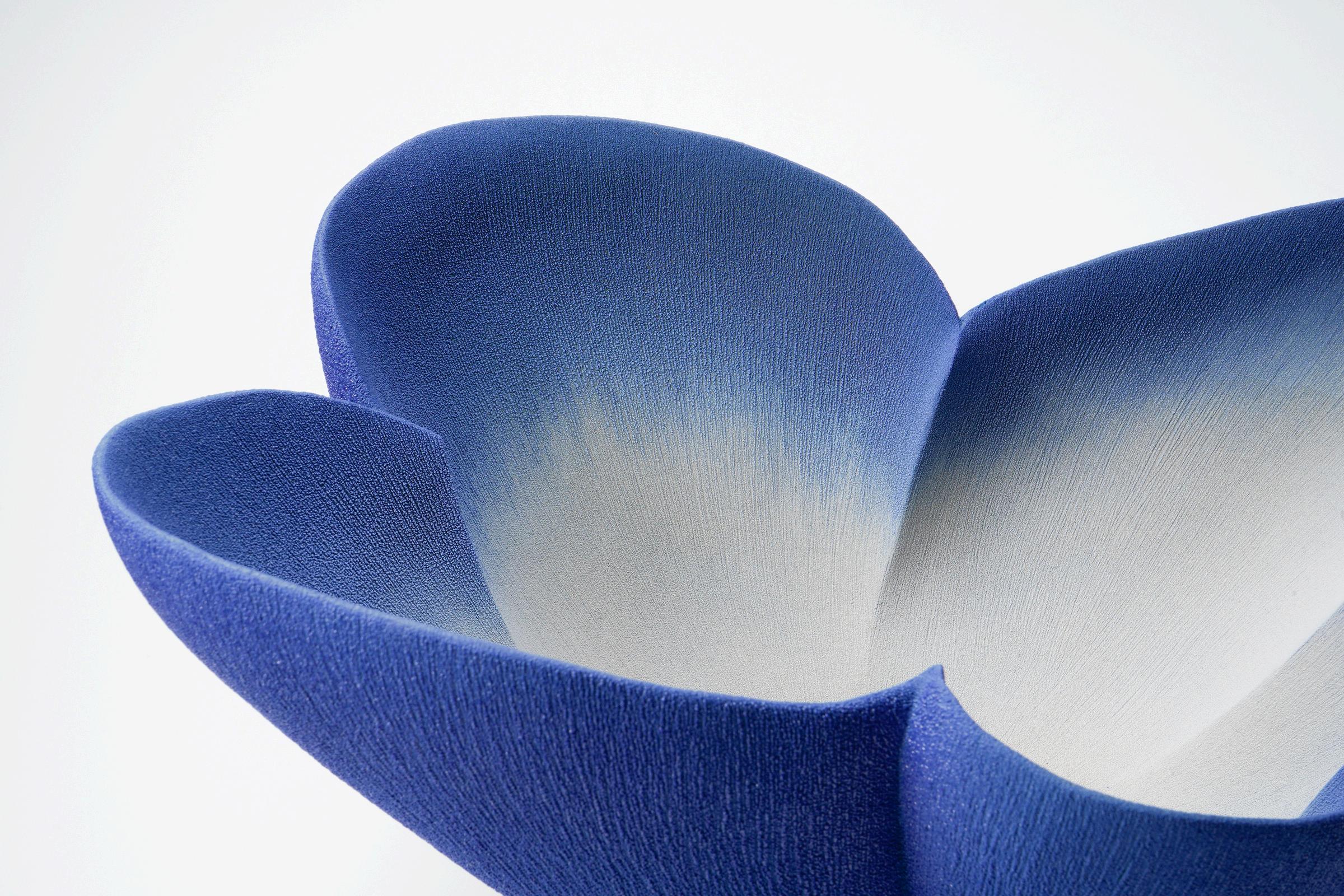

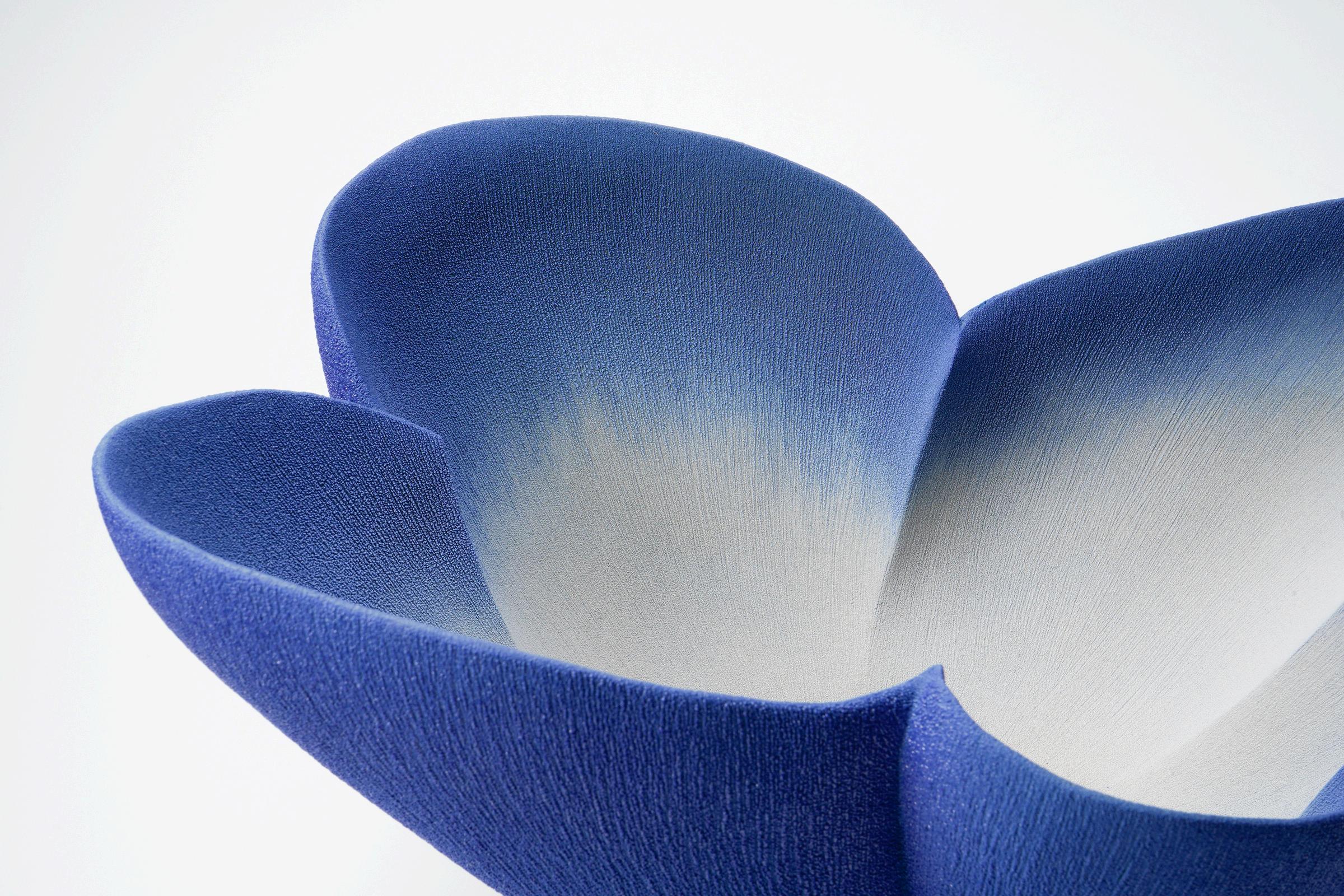

Hiruma Kazuyo 昼⾺和代, "Windswept Passage" flower vessel B 花器, 2024 Wth signed wood box stoneware 7 × 12 3/4 × 8 5/8 in

Hiruma Kazuyo 昼⾺和代, "Windswept Passage" flower vessel B 花器, 2024 Wth signed wood box stoneware 7 × 12 3/4 × 8 5/8 in

Tsuboi Asuka 坪井明⽇⾹, Chinese-brocade ancient skirt 唐

織裳, 2017, stoneware Carol and Jeffrey Horvitz Collection of Contemporary Japanese Ceramics Courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago

Hiruma’s often large-scale ceramic geologies speak to a passionate embrace and celebration of landscape as a creative source, as seen also in the work of other prominent women ceramists such as Ogawa Machiko and Koike Shōko

On occasion, she has adopted a more environmental, campaigning stance as in Haha naru daichi (Mother Earth), a floor piece first exhibited in 2008. To make it, she fashioned around 10,000 small pieces of clay, both large and small, fired them outdoors, and then arranged them carefully one by one over the course of a day Measuring some 12 to 15 feet in diameter, the circular installation was designed to resemble our planet, and visitors were encouraged to touch the pieces, feeling earth’s warmth, the pulse of its life and perhaps also its fragility

Glad to assume the role of public artist and ceramics activist, Hiruma supports educational activity in her native city of Sakai (part of greater Osaka) and has contributed to its sister-city relationship with Wellington, New Zealand More unusually, perhaps uniquely, she’s also put her ceramics to work in the Japanese movie industry

Scriptwriter Imai Masako, also from Sakai, asked Hiruma to make tea bowls to “star” in the comedy trilogy “Usoyao (We Make Antiques),” featuring a crooked dealer and a struggling potter who conspire to sell fake historic tea bowls:

It’s hard work making a movie, especially as I had to turn out several similar-looking copies of each piece for the different scenes, but it’s good that my bowls will survive in cinematic form!

13

Hiruma Kazuyo in her studio workspace, 2024

14

15

No 4 The Miraculous Series 奇跡, 2023

18

1/8

With signed wood plate, exhbited at Nitten

2023

stoneware and glass

3/8 × 18

× 13 3/4 in

"Windswept Passage" flower vessel A 花器颯然, 2024

With signed wood box stoneware

9 1/4 × 8 1/4 × 6 7/8 in

"Windswept Passage" flower vessel B 花器, 2024

With signed wood box, stoneware, 7 × 12 3/4 × 8 5/8 in

16

17

18

19

The Brilliance of Wind Silver I ⾵銀を刻む I 2017 Awarded the encouragement award at the 2017 Nikkokai exhibition glazed stoneware 16 1/2 × 24 7/8 × 12 1/2 in

20

21

22

No 7 The Miraculous Series 奇跡, 2024 With signed wood plate, stoneware and glass 15 1/2 × 10 5/8 × 9 1/4 in

23

24

No 6 The Miraculous Series 奇跡, 2024 With signed wood plate, stoneware and detachabe gass with gold foil 16 5/8 × 16 3/8 × 19 in

25

Black Raku tea bowl, 2024

Black Raku tea bowl, 2024

26

With signed wood box, stoneware, 4 1/8 × 4 1/8 × 4 1/8 in

“Lake Wind” water jar 湖⽔の⾵⽔指, 2024 With signed wood box, stoneware with gass and gold fol, 4 3/8 × 7 1/4 × 7 1/4 in 27

“Lake Wind” water jar 湖⽔の⾵⽔指, 2024 With signed wood box, stoneware with gass and gold fol, 4 3/8 × 7 1/4 × 7 1/4 in 27

26

Aflojar ゆるぐ 2017

Stoneware 18 7/8 × 22 7/16 × 15 3/4 in

29

30

signed wood pate awarded grand prize at Nikkokai exhbition, stoneware 14 3/8 × 18 1/8 × 17 3/8 in

31

No 2 Memories of Earth ⼤地の記憶, 2022

With

32

No 3 The Miraculous Series 奇跡, 2022 With signed wood pate exhibited at Sokoka 創工会, stoneware and gass, 18 7/8 × 17 1/8 × 11 1/4 in

33

34

35

No 1 Memories of Earth ⼤地の記憶, 2022 With sgned wood plate exhibited at Wachū-an, Kyoto stoneware 23 × 18 3/4 × 11 7/8 in

松 ⾕ ⽂ ⽣ M A T S U T A N I F U M I O

M A T S U T A N I F U M I O

Renowned for sculptural ceramics with intricate, subtly colored surfaces, Matsutani Fumio lives and works in his native Ehime Prefecture on the island of Shikoku He shapes clay by hand, allows it to dry, shaves it to refine the form, makes striations over the entire piece, glazes and fires it two or more times, and finally finishes it with sandpaper Born into a family that specialized in Tobe ware, handthrown, mass-produced everyday porcelain utensils with lively decoration in dark cobalt blue, Matsutani was determined to expand his creative horizons, enrolling when he was twenty years old at Kyoto Saga University of Arts where he studied under Imai Masayuki (1930–2023).

We asked Matsutani about his first teacher, a distinguished artist best known for stoneware plates and vases with inlaid designs of plants, birds, and especially fish Imai, Matsutani told us, did not approve of imitation and told him to “Make your own work: an artist is an artist only for his own lifetime ” He went to art college to learn ideas and perspectives rather than techniques, but he

J O E E A R L E

39

Matsutani Fumio in his studio workspace, 2024

I use colors as titles, without adding any descriptive words, because all that really matters is the feeling of the works and I want them to speak for themselves To put it another way, the technique is complex, but the expression is simple.

– Matsutani Fumio

40

acknowledges that his clay preparation, so critical to his current production, was initially supervised by Imai Despite the wide aesthetic and conceptual gulf that separates the work of the two, it is not difficult to make a visual connection between Imai’s textured finishes typical of many a postwar ceramic artist striving to bring new life to stoneware and Matsutani’s glowing monotone surfaces

Returning to Ehime, Matsutani originally intended to pursue a dual career, carrying on with the family business while developing his own studio practice, but soon realized it would be difficult to reconcile the conflicting demands of practical, wheel-thrown vessel forms and hand-formed sculptural ceramics

A few years back, he commented that due to its relative geographical isolation, Tobe ware developed during the postwar period in its own unique “Galapagos” manner, independent of porcelain production elsewhere in Japan Drawing a parallel between the backgrounds of Tobe ware and his own ceramic works, Matsutani observed:

I’ve come to admire how people in Ehime, with limited information at their disposal and few opportunities for trade, made such efforts to develop their own richly varied style of ceramic ware. It might seem strange to some of you, but although I’ve chosen to work in a way that’s completely different from this traditional local industry, I still feel a sense of inseparable connection with Tobe ware. (Matsutani Fumio, “Sentaku to en [Choice and Connection],” Homura 16, October 2014, pp. 2–3).

Today, however, Matsutani writes:

I have almost completely severed my ties with Tobe ware. Once upon a time I was fascinated by the simple, quick work of shaping vessels on a potter's wheel, but now I think I’m at last in a position to confront myself afresh, without compromise or deception. I feel the urge to make work that speaks on its own terms, without borrowing forms from others.

Colors play a critical role in Matsutani’s ceramic language, and many of his recent pieces are titled with just a single character: Sō 蒼 (Blue), Ō ⻩ (Yellow), or Rei 黎 (Black) We were intrigued especially by Rei not the usual word for “black” and asked the artist about this choice:

To my eyes, my black is not completely black, but rather a “black that has not yet become black” thanks to the different materials I use to make it, so I felt it would be a bit awkward simply to use the character Kuro 黒 (the usual word for black).

41

42

I searched for another single character with the right flavor and found Rei, which I liked because the word “reimei” 黎明 refers to the dawn of a new day, and the Rei works were the first in a new series. I use colors as titles without adding any descriptive words because all that really matters is the feeling of the works, and I want them to speak for themselves. To put it another way, “The technique is complex, but the expression is simple.”

Combining a hard-won sense of individuality with a disciplined technical foundation built on both workshop experience and art-college training, Matsutani has developed an outstanding practice that also embraces challenging, quasi-architectural form:

Mankind has always created buildings that seem to defy gravity. Although ceramics and architecture aren’t the same, I feel the same way about my sculptures … In future I’d like to create works formed by arranging and stacking multiple components, defying gravity but at the same time working with it.

43

Two works by Matsutani Fumio

45

Rei (Black) D–4 黎, 2020

With signed wood box, stoneware, 7 5/8 × 12 7/8 × 13 1/2 in

44

47

Rei (Black) Flower Vase D–2 黎花器, 2018 With signed wood box stoneware, 11 × 8 × 4 7/8 in

48

49

Sō (Blue) No 2 2024

With sgned wood box stoneware, 5 3/5 x 12 x 10 1/2 in

Mankind has always created buildings that seem to defy gravity. Although ceramics and architecture aren’t the same, I feel the same way about my sculptures.

– Matsutani Fumio

50

51

(Blue) D–4 蒼, 2020

Exhibited and nominated for Ceramic Society award stoneware 20 7/16 × 19 1/2 × 14 7/16 in

Sō

53

54

55

Rei (Black) Water Jar D–1 黎⽔指 , 2020

With signed wood box, stoneware, 6 1/2 × 9 × 9 1/2 in

Ō (Yellow) No 9 ⻩, 2024

Ō (Yellow) No 9 ⻩, 2024

56

With signed wood box, stoneware, 8 2/4 x 16 1/3 x 12 in

56

58

Rei (Black) D–3 黎, 2022 With signed wood box stoneware 9 1/2 × 17 1/2 × 12 1/2 in

59

60

No 15 Sō (Blue) 蒼 2021

With signed certificate of authenticity from the artist 19 × 26 3/4 × 17 in

61

With signed wood box, stoneware 8 × 15 1/2 × 11 2/5 in

62

Rei (Black) No 4 黎, 2024

63

64

65

Ō (Yellow) D–5 ⻩, 2021 With signed wood box stoneware, 8 5/8 × 14 × 11 5/8 n

Rei (Black) D–3 黎, 2018 With signed wood box stoneware 9 1/2 × 17 1/2 × 12 1/2 in

Rei (Black) D–3 黎, 2018 With signed wood box stoneware 9 1/2 × 17 1/2 × 12 1/2 in

67

68

With signed certificate of authenticity from the artist stoneware, 9 1/4 × 25 3/4 × 13 1/8 in

69 No

蒼 2021

12 Sō (Blue)

70

Rei (Black) D–7 黎, 2018

Wth signed wood box stoneware 9 1/2 × 10 × 9 in

71

Kachi (Brown) Sake Cup D–11 褐盃, 2023

With signed wood box stoneware 2 1/2 × 3 7/8 × 3 1/8 in

Ō (Yellow) Sake Cup D–3 ⻩盃, 2023

With signed wood box stoneware 3 × 3 1/2 × 3 15/16 in

Sō (Blue) Sake Cup D–2 蒼盃, 2023

With signed wood box, stoneware, 2 × 3 3/4 × 3 in

Rei (Black) Sake Cup D-7 黎盃, 2023

With signed wood box, stoneware, 9 1/2 × 10 × 9 in

72

(Below) Ō (Yellow) Sake Pourer ⻩酒器, 2024

Wth signed wood box stoneware 3 × 7 1/2 × 4 in

(Above) Sō (Blue) Sake Pourer 蒼継酒器, 2024

(Below) Ō (Yellow) Sake Pourer ⻩酒器, 2024

Wth signed wood box stoneware 3 × 7 1/2 × 4 in

(Above) Sō (Blue) Sake Pourer 蒼継酒器, 2024

73

Wth signed wood box stoneware 3 15/16 × 7 × 5 1/2 in

E A R T H L Y F O R M S

C E R A M I C W O R K S B Y H I R U M A K A Z U Y O A N D M A T S U T A N I F U M I O

© DAI ICHI ARTS, LTD , 2024

Authorship: Beatrice Chang, Joe Earle, Matsutani Fumio, Hiruma Kazuyo

Catalog production: Haruka Miyazaki 宮崎晴⾹, Yoriko Kuzumi 久住依⼦, Kristie Lui

Photography: Yoriko Kuzumi 久住依⼦

Selected images courtesy of: Matsutani Fumio, Hiruma Kazuyo, Nippon Kogei Association

D A I I C H I A R T S , L T D 1 8 E A S T 6 4 T H S T R E E T , S T E 1 F N E W Y O R K , N Y , 1 0 0 6 5 , U S A W W W . D A I I C H I A R T S . C O M 2 1 2 2 3 0 1 6 8 0 | 9 1 7 4 3 5 9 4 7 3

Hiruma Kazuyo 昼⾺和代, "Windswept Passage" flower vessel B 花器, 2024 Wth signed wood box stoneware 7 × 12 3/4 × 8 5/8 in

Hiruma Kazuyo 昼⾺和代, "Windswept Passage" flower vessel B 花器, 2024 Wth signed wood box stoneware 7 × 12 3/4 × 8 5/8 in

Black Raku tea bowl, 2024

Black Raku tea bowl, 2024

“Lake Wind” water jar 湖⽔の⾵⽔指, 2024 With signed wood box, stoneware with gass and gold fol, 4 3/8 × 7 1/4 × 7 1/4 in 27

“Lake Wind” water jar 湖⽔の⾵⽔指, 2024 With signed wood box, stoneware with gass and gold fol, 4 3/8 × 7 1/4 × 7 1/4 in 27

Ō (Yellow) No 9 ⻩, 2024

Ō (Yellow) No 9 ⻩, 2024

Rei (Black) D–3 黎, 2018 With signed wood box stoneware 9 1/2 × 17 1/2 × 12 1/2 in

Rei (Black) D–3 黎, 2018 With signed wood box stoneware 9 1/2 × 17 1/2 × 12 1/2 in

(Below) Ō (Yellow) Sake Pourer ⻩酒器, 2024

Wth signed wood box stoneware 3 × 7 1/2 × 4 in

(Above) Sō (Blue) Sake Pourer 蒼継酒器, 2024

(Below) Ō (Yellow) Sake Pourer ⻩酒器, 2024

Wth signed wood box stoneware 3 × 7 1/2 × 4 in

(Above) Sō (Blue) Sake Pourer 蒼継酒器, 2024