hidden gems

Sandwiches, speeches and solitude

by Carlos Gabriel Ramirezon page 15

Shifting the spotlight

by Keira Feng

by Keira Feng

on page 30

on page 15

by Keira Feng

by Keira Feng

on page 30

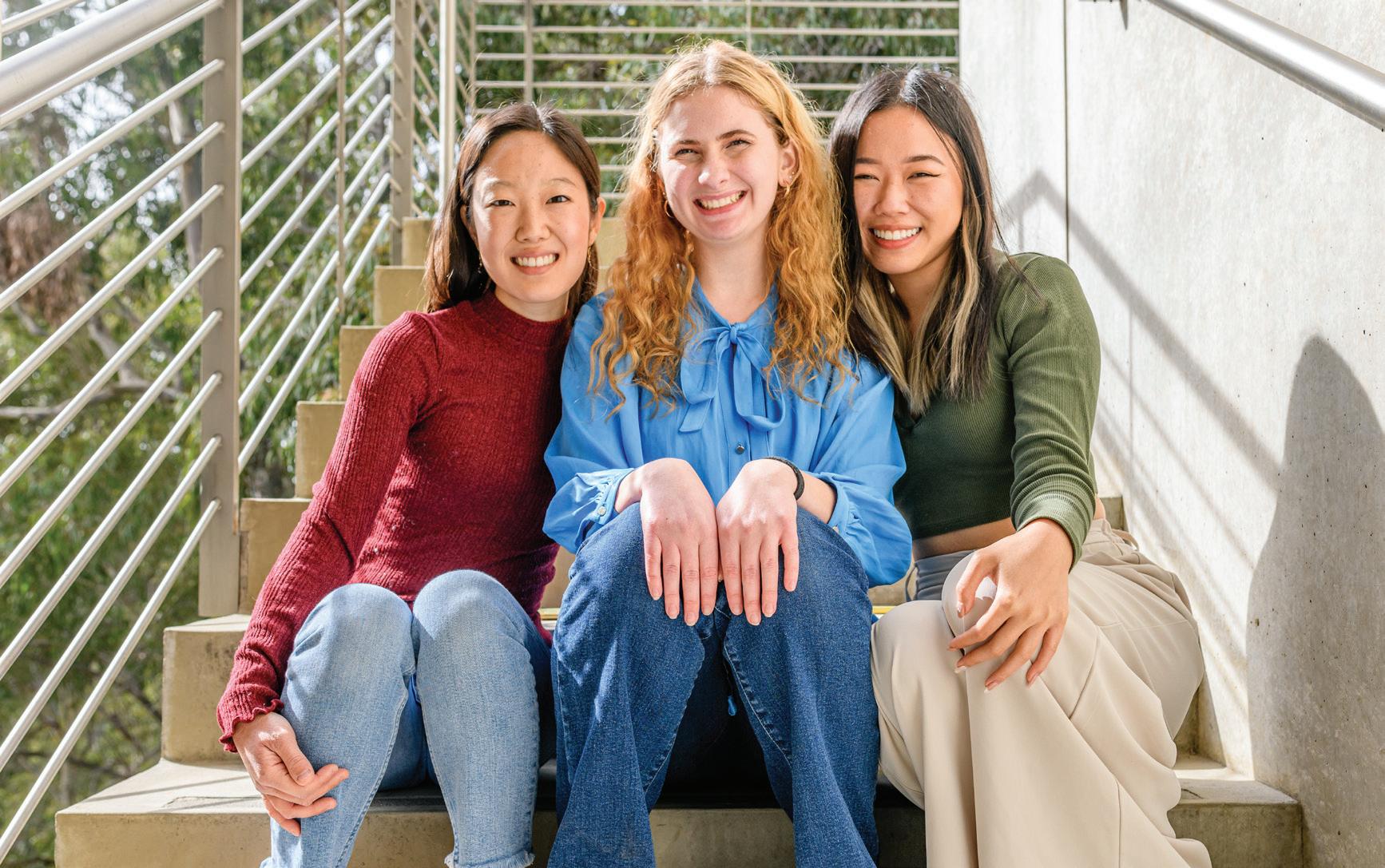

Dear reader,

Working at PRIME, the three of us have come to learn that stories are everywhere. Sure, there are the obvious ones – breaking news and major events – but there are also the smaller ones. This issue is all about those hidden gems.

On the roof of the Life Sciences Building, PRIME writer Emily Kim overcame her fear of bees. This quarter, she visited Bruin Beekeepers’ hives to learn all about the organization and the ecological importance of its mission. Although the looming threat of a bee sting was always present, she walked away with a newfound appreciation for an aspect of campus few are aware of.

Over on Janss Steps, a few select students are vying for a grand prize of $100 (plus bragging rights). Taking inspiration from the hit CBS reality competition show, Survivor @ UCLA gathers a group of students to participate in grueling challenges over the course of a quarter. As participants get voted off, the production crew films and edits the whole story. Join PRIME writer Breanna Diaz as she follows UCLA’s little-known spin on one of TV’s biggest shows.

At PRIME, our mission is to uncover the hidden gems all around us. We hope this issue broadens your perspective, from the stories of UCLA’s best-dressed students to the success of one of the Hill’s favorite food trucks. Thank you for picking up a copy of our magazine. Enjoy!

Megan Fu PRIME art director Abigail Siatkowski PRIME director Megan Tagami PRIME content editor

“There I stood, just as I always have: beautifully brown.”

When it comes to fashion, Generation Z is ready to make its mark.

Serving real fruit ice cream, Creamy Boys has quickly cemented its place as one of the most popular food trucks on the Hill. But how did one New Zealander man dominate UCLA’s late-night dessert scene so quickly?

written by EMILY KIM

written by EMILY KIM

Forget the underground tunnels and hidden rooftops –UCLA’s best kept secret is the beehives on campus.

What happens when a group of students enters a reality TV bubble to live out their “Survivor” dreams?

Los Angeles is no stranger to extreme heat. But nobody seems to recognize the true danger of a heat wave.

photographed by ETHAN MANAFI

written by KEIRA FENG

written by KEIRA FENG

Classic plays were not made with diverse audiences in mind. Do these scripts still deserve a spotlight?

PRIME writer Martin Sevcik has been told that his father abandoned him to follow his dreams. Yet Sevcik isn’t so sure those voices are right.

written by LAYTH HANDOUSH

designed by JULIETTE LIU

photographed by NEHA KRISHNAKUMAR

written by LAYTH HANDOUSH

designed by JULIETTE LIU

photographed by NEHA KRISHNAKUMAR

At UCLA, Bruin Walk is a fashion show, and everyone is a supermodel. Students catwalk through the cobblestone campus in outfits ranging from retro bell-bottoms to vintage Victorian gowns, modeling one-of-a-kind couture with the utmost confidence.

Generation Z – the generation known for TikTok trends, micro-influencers and dark-humored memes –is changing the fashion industry. Even as their fashion choices bewilder older generations, members of Gen Z prize creativity and sustainability in styling, stimulating a 50% increase in second hand shopping between 2019 and 2022, according to Forbes. Now in college, members of the generation enjoy more independence to express themselves through their clothing.

For me, coming to UCLA presented a Pinterest board of outfit inspiration. The styles I saw on a daily basis were muses for my own wardrobe and left me wondering about the stories behind peoples’ outfits.

And so, I consulted an expert to learn more about the style of today’s students.

Esther Blum, a third-year economics student, met me at Starbucks in an emerald-green blazer with a green cross-stitch-patterned purse to match. After brief introductions, I shifted my conversation to Blum’s forte: fashion. Her eyes lit up, and for the next few hours, we covered everything from her favorite brands to microtrends. I expected no less enthusiasm from the director of styling at Fashion and Student Trends, UCLA’s first and largest fashion organization responsible for the school’s annual fashion show and style magazine, FAST at UCLA.

Blum’s love for fashion was evident in her every word. Coming to Los Angeles from Switzerland, Blum said she was amazed by the drastic difference in styles and trends that emerge across the world. She laughed as she recalled the contrast between young Americans’ obsession with Crocs and the daily formal dress of Swiss

people. And the differences didn’t stop at countries –as Blum joined FAST and explored fashion’s evolution across generations, she came to a simple conclusion as to why she believes Gen Z dominates the scene.

“I think our generation just doesn’t give a fuck,” Blum said.

She attributed her consensus to the radical role of social media. As users turn to Instagram and TikTok to showcase their creativity and popular styles, Blum believes that major brands take note of their young consumers’ preferences. With the fashion industry now catering to Gen Z, young adults feel a greater sense of control over what they wear and how they wear it.

Third-year English student Milagro Jones is just one member of Gen Z pushing the style boundaries.

Jones has walked campus in everything from formal suits to kimonos, and they do not disappoint when they arrive at our interview wearing red, black and white patchwork pants. Platform vegan-leather shoes adorned with silver spikes and buckles make for hardcore footwear, and their winged-heart choker complements the vampire cape draped around their shoulders. Without a doubt, this was the most far-out fit I had ever seen.

As a kid, Jones said their wardrobe was a collection of donated and thrifted pieces, adding that their sense of style was determined by necessity. Now in adulthood, Jones prioritizes sustainability as they add to their wardrobe, shopping from small businesses and environmentally friendly sources whenever possible.

Jones is not the only member of Gen Z who is prioritizing sustainability. In response to pressure from their young consumers, brands are making a conscientious shift toward eco-friendly production methods, Blum said. H&M, for example, has pledged to use 100% sustainably sourced materials by 2030 and encourages customers to recycle unwanted clothes at their retail locations.

Similar actions have been taken by Levi’s and Patagonia, whose fair-trade and manufacturing practices aim to ensure environmental sustainability. Though

I think our generation just doesn’t give a .

“ “

many members of Gen Z still support fast-fashion companies such as Shein, whose mass production methods produce 6.3 million tons of carbon dioxide each year, the growing popularity of this sustainability movement may signal a shift in how companies and customers approach production and consumption in the fashion industry.

When we met at the Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden, Jones told me their outfit choices come from a history of cautious dressing and constantly trying to blend in. Growing up in neighborhoods with heavy gang activity, Jones said they always found their punk rock style at odds with the expectations of local gang members. Their style was considered a challenge to authority, and threats from gangs quickly stifled Jones’ self expression.

Now at UCLA, Jones’ heightened sense of safety has manifested itself through fashion. They added that they feel no need to blend in when everyone’s expression is different on campus.

“I feel like UCLA is also an inspiration because there’s so many people here that got dope fashion sense and different styles that I’ve never seen,” Jones said.

Affability also characterizes Gen Z’s affiliation with fashion. Complimenting a stranger’s outfit can lead to new friends, which is exactly how I met Sylas Umoren.

Walking past Bunche Hall in a patched racing jacket and white-rimmed shades, the first-year global studies student caught my eye with his swag and a Snorlax. Stirred by childhood nostalgia, I complimented Umoren’s star-patterned backpack, whose cream-and-blue plush exterior takes the shape of one of my favorite Pokémon, Snorlax. Umoren proudly showed it off as he explained that he tries to incorporate personal interests, such as video games and music, into his outfits as much as possible.

Umoren said his newfound interest in styling came from a recent trip to Japan,

where he observed a foreign fashion culture firsthand.

“There’s all these people wearing whatever they want and looking nice,” Umoren said. “It inspired me to also do the same with myself.”

Back home in San Diego, Umoren said he has faced judgement from family members while experimenting with different outfits, making it difficult for him to maintain his confidence. But in Westwood, Umoren said he has joined a like-minded, inventive community that has helped him feel more comfortable with himself and his new college surroundings.

“I think expressing yourself through fashion is important because you get to connect with people,” he said. “It’s a lot about connecting with other people through your interests.”

Blum said a big part of Gen Z’s claim to fame is its development of microtrends, which are styles whose popularity wanes within a few weeks or months. Many of these microtrends, such as bleaching and denim painting, emphasize the do-it-yourself attitude that encourages people to take clothing production into their own hands. Kayla Stonum, a fourthyear human biology and society student and frequent DIY-er, uses the creative freedom of microtrends to her advantage.

I met Stonum on my way back to the dorms. Her outfit was reminiscent of young Avril Lavigne – she wore a silver

“ “

cross necklace intertwined with a snake around her neck and a laced, shoulderless top with a frilled black skirt.

Stonum’s style journey stems from a stifling history of high school uniforms. When she finally arrived at college, she took to designing outfits inspired by her favorite fashion influencers. Throughout her years at UCLA, she’s resolved to find a compromise between functional and creative, turning to different materials such as ribbons and mesh when customizing her outfits.

Stonum said styling has introduced her to more friends in the fashion scene and has exposed her to the aesthetics of LA’s art and fashion districts. Through her adventures around the city, Stonum has found fashion to be one of the best outlets for creativity and camaraderie.

“I think it’s a perfect platform for people to really hone in on their identities and how they want to present themselves,” she said.

Stonum added that her exploration of fashion has inspired her to incorporate creativity into all aspects of her life. After graduating in the spring, she hopes to work in fashion and music management, drawing on the confidence she has gained through her stylistic pursuits.

“As long as you’re ... pushing yourself and you have a supportive community of friends, then I think you’re golden,” she said.

And Blum believes that everyone should be free to dress how they like. For those who are still searching for their own identity and style, she shares her advice:

“Whatever makes you feel good in the moment, just go for it!” ♦

It’s a perfect platform for people to really hone in on their and how they want to present themselves.

“ “

written by MALLORY COOPER

designed by EMILY TANG, JUSTIN HUWE and JOSEPH JIMENEZ

photographed by MEGAN CAI

written by MALLORY COOPER

designed by EMILY TANG, JUSTIN HUWE and JOSEPH JIMENEZ

photographed by MEGAN CAI

It was 7:54 p.m. on a brisk Saturday night. According to the iPhone Weather app, the air outside hung at 48 degrees – practically subzero temperatures for Los Angeles. But the cold was no deterrent for the Creamy Boys food truck. For the team inside, it was tripledigit temperatures, and customers were in dire need of something sweet and refreshing. It was positively perfect ice cream weather.

Creamy Boys Ice Cream is the midpoint between an Instagrammable snack spot and a friendly neighborhood ice cream man. The truck serves up real fruit ice cream, a staple sweet in New Zealand made with only a vanilla base and frozen fruit. Its bright pink lights first catch people’s eyes, but Creamy Boys’ pastel swirls of icy sweetness reel people – including many UCLA students –in for a taste.

Since fall 2021, any niche craving has been only one food truck away for students living on the Hill. Food trucks were first introduced to UCLA to counter staffing shortages in the dining halls after students’ return to campus, and they have since become a fan favorite. On a typical day, eight to nine different food trucks will call UCLA home for one of three meal shifts.

Among the array of food truck options at UCLA, Creamy Boys stands alone. Even when temperatures drop and nights stretch into midnight snack territory, a devoted fan base flocks to the truck in droves of more than 200 students per shift.

The inside of the Creamy Boys truck resembles a hybrid between a garage band studio and a mechanized conveyor belt. Despite the trailer’s cramped conditions, each team member seamlessly assumed their unique role in the ice-cream-making process. Standing center stage in a cheerful blue-striped apron, Duncan Parsons conducted the controlled chaos of Creamy Boys with each pull of the ice cream machine’s lever.

Hailing from an apple orchard in New Zealand, the owner and operator of Creamy Boys grew up in fields of strawberries, peaches and plums. During hot summer

days growing up, Parsons cooled off with real fruit ice cream on his walks home from work. Parsons said he now associates ice cream with childhood nostalgia, reminiscing on time spent with his friends.

“Our life was really about eating fruit from trees,” Parsons said.

This philosophy of incorporating fresh fruit into everyday food remained with Parsons throughout his undergraduate studies at Duke University. After graduation, Parsons moved to LA, enticed by the lively food truck scene and sunny weather – perfect for ice cream. Embarking on a new passion project, Parsons turned to an old friend for support.

Like Parsons, Joe Wedd grew up in the orchards of New Zealand. When the opportunity arose to start an ice cream truck, Wedd knew it was too sweet to pass up. He signed on as the special projects and operations manager of the burgeoning business.

Working with a food truck builder from Long Beach, the friends’ shared dream of running an ice cream truck came to fruition. By April 2021, Creamy Boys was on the road.

Nearly two years later, the truck is making a prolonged pitstop at UCLA. Although ice cream is usually reserved for the sweltering heat of summer afternoons, Creamy Boys has found its footing in the cold night of the 8 p.m. to midnight extended dinner shift.

Among the courageous souls stopping by Creamy Boys on this chilly January evening was Alysa Phattanaphibul. The first-year materials engineering student was the first in line, claiming her spot long before the truck’s neon lights snapped on. Grabbing a late-night soft serve at Creamy Boys isn’t just about satisfying her sweet tooth – for Phattanaphibul, it’s an opportunity to bond with friends.

Phattanaphibul recalled how one night, ice cream helped to relieve some of her sadness. After snagging some soft serve, she ate with her roommates on their dorm floor.

“I was crying, and I was really sad,” Phattanaphibul said. “We found out Creamy Boys was here, and my roommates were just trying to lift my spirits.”

Phattanaphibul, who had stopped by Creamy Boys with her roommate, continued recounting stories until reaching the front window. While Wedd scribbled her name onto the bottom of her bowl, Phattanaphibul dropped a small blue slip as payment into a jar. As the jar accumulated more slips, it became clear Creamy Boys was having a busy night.

Despite their resemblance to Monopoly money, these meal vouchers signal a food truck’s success. At the front desk of any of UCLA’s main residential halls, students can redeem one meal swipe for one food truck meal voucher. These vouchers can be exchanged at any food truck on campus for one of the meals on their UCLA-specific menus.

According to an emailed statement from UCLA Dining Services, each individual meal voucher is valued at $9 –the cost of producing one meal for one person. Per the

“Our life was really about eating fruit from trees.”

statement, this cost was calculated by dividing the annual cost of food and labor by the number of meals served each year. At Creamy Boys, this translates to a cup of soft serve with a choice of topping and chips and/or cookies.

After a shift, vendors like Creamy Boys exchange the vouchers with UCLA Dining, which then reimburses the food trucks and produces an invoice for payment, according to another emailed statement from the department.

“It’s nice because it’s simple and accessible for students, and it’s straightforward for us,” Parsons said.

Although Creamy Boys now has a steady stream of student customers, the truck has traveled a long and winding road to serving UCLA – traversing the tumult of a global pandemic.

According to Parsons, one of the most difficult obstacles Creamy Boys faced during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic was finding a consistent consumer base. Lockdown mandates canceled many community events, typically a prime spot for food trucks. Even when these events resumed, Parsons said the constant changes in COVID-19 safety protocols made planning for the future a nearly impossible feat.

After searching for a loyal pool of ice cream fanatics at

As word of real fruit ice cream and pavlova – the truck’s signature New Zealand-style meringue dessert – spread, the truck developed a cultlike following.

LA night markets and movie sets, Creamy Boys arrived at UCLA in December 2021. Wedd anticipated a gradual ease into serving the campus, expecting fewer than 100 customers on the first night. But that inaugural shift far surpassed his initial expectations. A mass of 350 students showed up, ready for a post-study treat.

“We actually ran out,” Wedd said. “We were giving out stickers, just being like, ‘Sorry guys.’”

As word of real fruit ice cream and pavlova – the truck’s signature New Zealand-style meringue dessert – spread, the truck developed a cultlike following. Now, students even begin chanting for Creamy Boys as the truck drives in, Parsons said.

Following the challenge of developing its customer base, the UCLA community provided Creamy Boys with constant business. While food trucks scarcely encounter repeat customers because of the lack of a consistent storefront, serving UCLA on a regular basis drew frequent attendees to the truck.

Student life has since bounced back from lockdown days. Not far removed from his own time as a student, Parsons said the lively energy of a college campus is one of his favorite aspects of serving the UCLA community. He noted that the connections he has forged with students have allowed him to fulfill his mission of fostering a sense of community.

“We’re not just giving, say, ice cream with pavlova ... but also some entertainment and a brand they actually care about,” Parsons said.

While Creamy Boys has enjoyed success serving the Hill’s residents, the food trucks haven’t been a welcome presence for everyone.

Creamy Boys’ stability stemmed from UCLA Dining’s instability during the return to inperson instruction in fall 2021. In response to labor shortages in the dining halls on the Hill, the university brought in independent food trucks as students returned to on-campus housing. Although UCLA has since lifted many pandemic

restrictions, UCLA Dining said in the emailed statement that food trucks have continued serving students because of persisting workforce shortages.

Since the return of students to the Hill, relations between UCLA Dining and the American Federation

representing UCLA Dining employees – have been underscored by tension. At the center of conflicts is the outsourcing of dining labor to non-University of California employed workers. The addition of food trucks has only complicated this debate further; in fall 2021, protests against the university’s response to staffing shortages were held just outside dining halls.

Todd Stenhouse, a spokesperson for AFSCME Local 3299, said the presence of food trucks at UCLA appears to be a form of outsourcing. According to Stenhouse, Article V of the union’s contract with the University restricts how many UC jobs can be outsourced. UCLA is relying on a third-party vendor system to perform tasks that dining workers would usually do, Stenhouse said.

“If the University says, ‘We have a need, it can’t be met by our current workforce,’ their first step is to confer with their bargaining unit (the union) about that need,” Stenhouse said. “That has not happened in this case.”

According to an emailed statement from UCLA spokesperson Bill Kisliuk, the university has worked with AFSCME Local 3299 since October 2021 to address shortages within the UCLA Housing and Hospitality Services departments. The collective bargaining agreement between the university and AFSCME Local 3299 allows UCLA to contract out dining services if there is an

insufficient quantity of employees, Kisliuk added in the statement.

With staffing challenges remaining unresolved, food trucks are here to stay for the time being. Even as the clock neared midnight and the temperature approached a bitterly cold 45 degrees, a handful of students groggily placed orders just minutes before the end of the Saturday night shift. It was a long night for the team at Creamy Boys, but Wedd took the final few names with the same sunny demeanor as he used with the very first order.

“It’s really cool to see the places ice cream might get you to,” Wedd said.

As the team began cleaning up the food truck for the night, they finally took a moment to relax. Styrofoam containers of takeout food in hand, they spoke freely without the constant carousel of names, ice cream flavors and toppings.

Despite four hours of soft-served mayhem, Parsons appeared as laidback as always, his pink hoodie no longer covered by his apron. He leaned against the side of the trailer with an air of contentment.

“My vision starting the ice cream truck was: This will be fun. This would be a cool thing to do,” Parsons said. “Why wouldn’t you want to be an ice cream man? And that’s what we stay true to.”

“It’s really cool to see the places ice cream might get you to.”

illustrations by MEGAN WU

written by CARLOS GABRIEL RAMIREZ designed by CRYSTAL TRINH

illustrations by MEGAN WU

written by CARLOS GABRIEL RAMIREZ designed by CRYSTAL TRINH

Every day for 12 years, I ate the same sandwich. Made with the same ingredients, wrapped in the same paper towel and placed in the same plastic bag, the ham, mayonnaise and wheat bread eventually staled in my mouth. My taste buds had forgotten, just as I had, the reason I was eating it.

So one afternoon in 11th grade, I asked my mom.

“Ayo Ma! I swear I appreciate whatever you make me, but why the sandwich every day? Why not mix it up?”

“What?” she said, staggering. “You told me to make it for you.”

After thousands of sandwiches, I had forgotten it was my own recipe. I knew the sandwich itself originated during my years at Alice Fong Yu Alternative School –my elementary and middle school – but under sudden scrutiny, my memories were foggy. After leaving the school years ago, it seemed time to finally look back.

Only, I found more than just a sandwich. Much more.

I remember the car ride to Alice Fong Yu. My family and I would spear through the thick fog, driving higher into San Francisco and away from my neighborhood at the bottom of the city. I would feel my chest tighten, my stomach churning with nausea as we drove over the hills and into the Sunset District. It wasn’t until later that I learned I wasn’t supposed to dread driving to school every day.

Alice Fong Yu is a Chinese immersion school serving kindergarten through 8th grade. Most of my classmates were East Asian, making me one of the very few Latine students in my class. We began learning Cantonese in kindergarten and Mandarin in sixth grade.

As a kindergartener, I did not know how to interpret my differences from my classmates. I relished in innocent friendships and sincerely anticipated my peers’ company every day. But what excited me the most about each school day was lunchtime.

I would race to the cafeteria, eagerly unzipping my hand-me-down lunch bag and pulling out cheesy pupusas, husk-wrapped tamales, steamy casamiento or sopa de frijoles – my favorite. When I saw the dented thermos waiting in my bag, I knew unscrewing its black cap would release the savory aroma of home.

But some of my classmates did not share my excitement. Even at age five, my heart broke when they called my food “poo,” inspired by the brownness of the soup my mother made. My friends’ laughs haunted me, so I begged my mom to change my lunch. I just wanted a simple sandwich.

As I grew older, I practiced times tables while my

“

My heart broke when they called my food ‘poo,’ inspired by the brownness of the soup my mother made.

classmates called me Mexican, and my teachers guessed I was from Ecuador. I quickly learned not to care to make the correction that I was Salvadorian since my heritage became expendable. And yet, comments about my race followed me into my middle school years.

My fourth-grade classmates reminded me of my race often, calling me Juan to be funny, exotic to be ostracizing and border-hopper to be insulting. I was mostly indifferent, but when one student called me chocolate – inspired by the dark brownness of my body – my skin prickled. As I grew angry, another classmate began to laugh. I questioned myself: Why did I care about their ridicule?

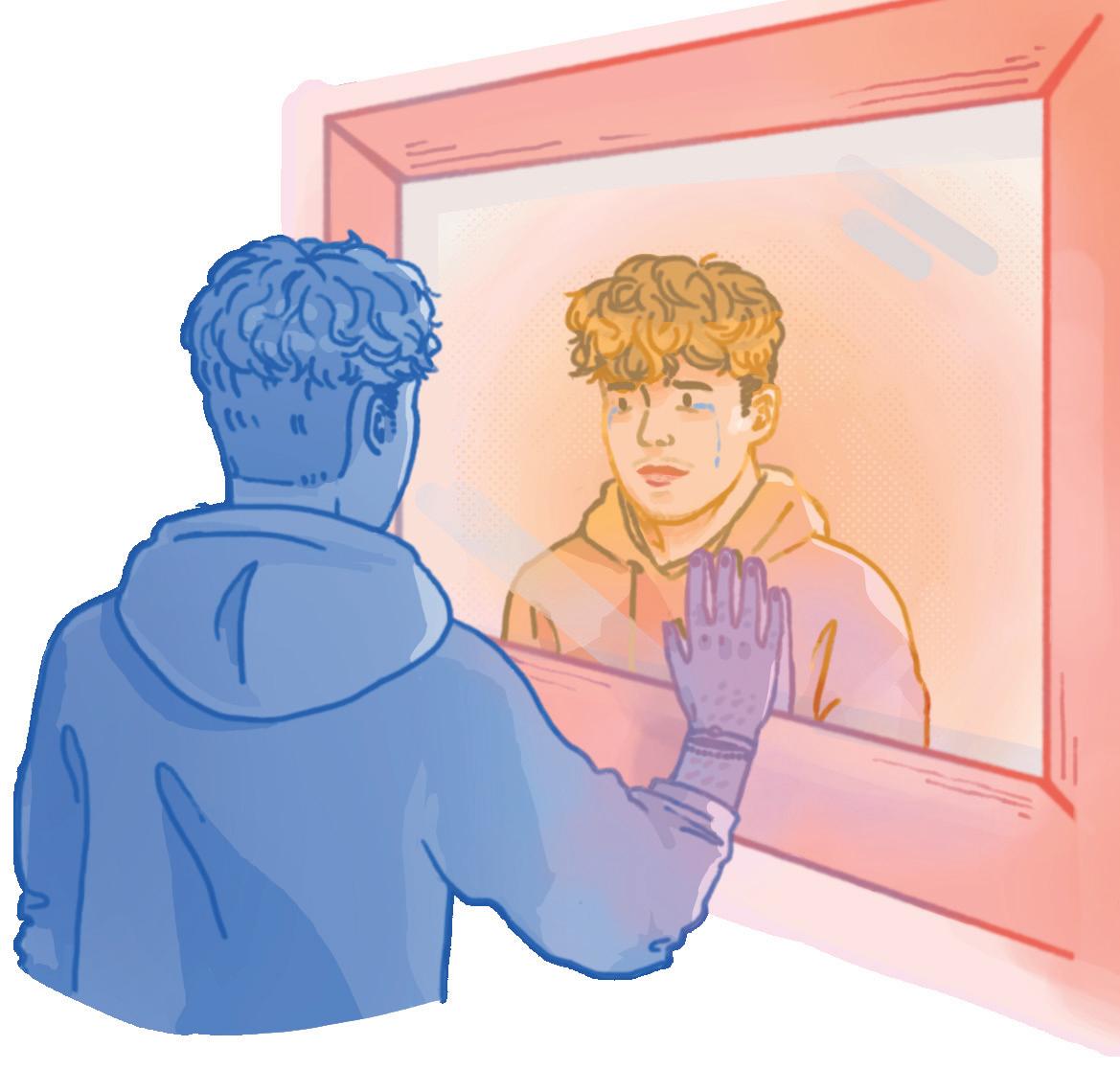

But after I got home and dashed to the bathroom, I broke into tears. Looking in the mirror, I began to pick out what to blame. As I watched the tears fall down my plump cheeks and the snot run from my wide nostrils onto my thick upper lip, I cursed my brownness and dreamt of lighter skin.

And I carried that resentment with me for a long while. Wearing sweaters and pants to cover my arm and leg hair, I hid my growing adolescent abnormalities. I tried to pray away my dark skin as I pinched my nose to make it smaller, strangled my thighs to make them skinnier and sucked in my lips to make them thinner.

My Spanish speaking skills diminished as I relentlessly studied Cantonese and Mandarin, eager to fit in with my classmates. I subtly, and mostly unknowingly, began to reject Salvadorian food. Devoted to my new lunch, I

became known for my signature ham and mayonnaise sandwich. It was my “thing” – a sign of my successful assimilation.

Standing alone on the stage, staring blankly at 150 people and fumbling at a speech I barely knew, I began to realize how meaningless assimilation truly was. That fateful speech was the centerpiece of an event celebrating the Chinese exchange program held at Alice Fong Yu. Although the event was an eighthgrade affair, I was chosen as a seventhgrader to give the speech. It was not my first time on stage. Throughout my time at Alice Fong Yu, I wrote campaign speeches for the student government, made announcements in Cantonese and Mandarin and was selected to represent our school at numerous events.

Despite my teachers’ claims that I possessed exceptional speaking capabilities, I still seemed to perform excessively. Even then, it was obvious that the underlying reason was my race. It was no secret the school saw fit to present me on a pedestal, proudly showing off their successful project: a brown boy who could speak Chinese.

Nevertheless, I relished the attention. After witnessing the scorn my older brothers received at Alice Fong Yu, I felt tremendous relief in being adored. But I was unaware of how much it would eventually cost me.

It was on that stage, during that seventh-grade speech, that the pedestal I stood upon came crashing down.

My legs shivered, and I felt frozen as I faced 150 people, none of whom looked anything like me. Even as I stuttered in a language I had spent a single year learning, I blamed myself for my failure, despite the fact I was

“

The school saw fit to present me on a pedestal, proudly showing off their successful project: a brown boy who could speak Chinese.”

given a single day to craft the speech. Shame coursed through me as I pulled out a notecard, barely looking at the words I rushed to speak. I held back tears, wondering if the audience’s blank stares held judgment or pity. I wondered if they saw me cursing my circumstance. I wondered if they saw me wishing I wasn’t brown.

An eerie sensation that my world was deeply flawed followed me through my final year at Alice Fong Yu. I felt uneasy on the last drive down the city to return home. I know now that I was close to uncovering the truth, about to uncap the pain I had bottled up for so long.

My first day of high school started not with a car ride through the city but with a short walk from my house to campus. After nine years at Alice Fong Yu, attending Balboa High School was jarring.

I immediately noticed an academic advantage after overcoming the rigors of Alice Fong Yu, but something was missing. As one of countless Latine students at Balboa High School, I no longer stood out for my race. The assimilation I had worked so hard to achieve at Alice Fong Yu was no longer necessary or even beneficial to me.

Thus, I numbly navigated my first year of high school, grappling with the aftermath of the assimilation.

Drifting between dreary days and dull nights, I walked to school in the morning, meandered through flavorless classes and made the trek straight home. At the time, I had few friends and abandoned my lifelong hobby of reading in favor of the mindless world of YouTube, video games and social media. I lay in bed, perpetually awake, my face illuminated by flickering blue light.

Although I continued to learn Mandarin in high school, my commitment fell short of the dedication I maintained in middle school. At home, I exclusively spoke English, refusing my dad’s commands to speak in Spanish. When he begged, I avoided his eyes, trying to ignore memories of the Alice Fong Yu stage that flashed in the back of my mind.

I was terrified of accentuating my differences. After spending all of my life learning four languages, I felt limited to only speaking English. It made sense – after all, I was still eating the same sandwich every day.

In 10th grade, however, something strange happened: I felt again.

I walked out of class after going through the motions of another mindless day. Even as the wildfires raged in California, my head remained down and my back continually hunched. My eyes, however, caught something more interesting than the chasms in the sidewalk.

I looked up to see that the air was murky with smoke. A red sun shone through the smog, bleeding orange into the

clouds. Ash floated down from above like expired rain. My lips shriveled as I took a breath, nearly coughing on the dry air.

It may have been the taste or maybe the smell, but my chest grew tight as I watched the ash-filled landscape. My skin dried as my eyes watered, and each step I took rang in my hazy head. My bulging backpack, filled with books I rarely read, was weightless compared to my heavy heart. In the space between school and home, in a city of thousands, I was alone. I felt so alone. The worlds I knew, built on sandwiches and languages, were falling as I continued the walk home under the bleeding sun.

When I made it back home, I cried. Under the weight of my crushing memories, my pain broke free. I lay in bed as the bruises and burns of a forgotten past flooded my eyes for the first time in seven years. And I kept crying for years.

Brandishing chipped nail polish and arm hair, I felt the world spinning as my brother drove me over the San Francisco hills. My legs were stiff under the dashboard, my stomach was twisting, and my chest was tightening with each breath as we drew closer. I sat amazed but mostly sorry that I felt dread like this every day when I was young.

Still, it had been five years, and while the looming red brick building made me want to vomit, it did not seem as tall as it once did. I walked through the gates, readying myself to face Alice Fong Yu.

But nothing happened. My nerves never dissipated. The walls did not crumble like I had vanquished a great enemy. The bells did not sound to announce the fall of a great evil. The school kept running, students kept talking, teachers kept rushing, and I stood frozen as the day went on.

But after the car ride home, I felt a rush of pain on my walk to the bathroom. My legs shivered as familiar tears welled in my eyes. In the mirror, I appeared just as I always had. But armed with a wondrous perspective, tempered by trauma, I could finally see what is true. There I stood, just as I always have: beautifully brown. And new tears fell. I stared at them in wonder as they glided down my bronze cheeks, trailing ablaze with a golden glow and giving me a satisfaction I had never known. My full lips parted, and my mighty nostrils flared as I smiled, finally staring at the savior I had been waiting for.

It will certainly be a lifelong struggle, but I am ready to begin healing. I am ready to eat, feasting on pupusas so creamy and sopa so savory that they start to repair the severed ties to my heritage.

I am finally hopeful enough to fight, reclaiming what was taken from me, one mouthful at a time. ♦

“In the space between school and home, in a city of thousands, I was alone.”

“ There I stood, just as I always have: beautifully brown.”

written by EMILY KIM

designed by KIMMY RICE

photographed by JOSEPH JIMENEZ

written by EMILY KIM

designed by KIMMY RICE

photographed by JOSEPH JIMENEZ

Here’s a fun fact: There are bees on the roof.

I’m standing on the rooftop of the Life Sciences Building amid two active beehives, watching a few errant honeybees lazily drift from the box Rey Soto has just opened.

“This used to be used for bird research,” said Soto, a data manager in the UCLA Department of Epidemiology and director of operations for Bruin Beekeepers at UCLA. He gestured to the cages on the rooftop. “Now we’re going from birds to bees.”

Most UCLA students haven’t seen the hives before. They’re unassuming – just wooden boxes with vertically stacked frames of honeycomb. A couple of boxes sit in metal chicken-wire cages between the thundering air conditioning units on the rooftop. Signs above the entryways warn visitors of nearby active hives.

This setup is all well and good, but there is a slight problem. I am scared of bees.

I tell Soto this truthfully.

His response? “Just close your eyes.”

So I do. But I open them soon after. There is a box of bees in front of me, and I don’t want to miss a thing.

Bruin Beekeepers leads campus sustainability efforts with its emphasis on bee conservation, education and research. The club is also a satellite branch of the California Master Beekeeper Program, a statewide education program that certifies beekeepers.

Jonathan Fox, an alumnus and founder of Bruin Beekeepers, was inspired to create the club in 2018 after listening to a talk by a local beekeeper, who accompanied his presentation with a box of bees. The talk, alongside Fox’s passion for conservation, led him to incorporate beekeeping into the club as a way to actively engage students with sustainability issues.

“No one at UCLA had been keeping bees,” he said. “And so I just thought, ‘Well then why not? Why don’t I do it?’”

Although having hives was a goal at the outset for

Fox, the expensive equipment required for honey-beekeeping prevented the new club from establishing hives immediately. But little did Fox know, another student group at UCLA also had their sights set on beehives.

It all began with an unexplained candle on a table in 2019. Members of Bruin Home Solutions, a club dedicated to student-led sustainability projects, were sitting around the table brainstorming project ideas when Kian Nikzad was inspired by the candle’s mysterious presence. Nikzad, an alumnus and former executive director of Bruin Home Solutions, envisioned a local economy project in which candles could be sustainably produced within the Westwood region. But this meant they needed beeswax.

To kick start the process, Nikzad created Bruin Apiary as a project under Bruin Home Solutions. The Bruin Apiary team then reached out to Bruin Beekeepers and UCLA administration to pitch their idea of keeping bees on campus. This partnership created the current Bruin Beekeepers club in

The merger has enabled the club to combine both the educational and practical aspects of beekeeping into one setting, said Angela Tang, a co-director of Bruin Beekeepers and fourth-year geography/ environmental studies and mathematics student.

Tang joined Fox’s Bruin Beekeepers in her freshman year while looking for a sustainabilityfocused club. While she didn’t know much about bees before joining, her passion for the insect soon grew.

“What really hooked me was learning that there’s this whole other world of bees that most people don’t really think about or know about,” she said.

Back on the roof of the Life Sciences Building, I’m able to step into the world Tang has grown to love.

According to Isabel Zabryanskiy, a co-director of Bruin Beekeepers and fourth-year civil engineering student, the stars of the rooftop are the two honeybee hives. She added that the club owns four additional hives at a ranch in Santa Paula, California, that also house honeybees. But even though Bruin

Beekeepers only keeps honeybee hives, it dedicates its education and conservation efforts to native bees. As I soon learned, the distinction between native bees and honeybees is essential for focusing conservation efforts.

Native bees are incredibly effective at pollinating and sustaining native plants, said Hollis Woodard, an associate professor of entomology at the University of California, Riverside. In contrast, honeybees were brought to the United States in the 17th century via colonization, and their beeswax was used to make candles. Although honeybees are used for crop pollination, some native bees are more effective pollinators than honeybees, according to research from UC Berkeley. This effect is particularly noticeable in local plants, Woodard added.

Nikzad noted another important benefit of native bees: They increase an ecosystem’s biodiversity and provide unique ecological services. For example, some native bees only pollinate certain plants, and many native bees aerate the soil by living in the ground.

“There’s beauty in these relationships,” Nikzad concluded. “There’s this spiritual aspect of it, of caring for these things.”

Woodard also emphasized the ethical importance of minimizing harm and supporting native bees beyond the practical purpose of pollinating native plants.

“Equally important is the ethics of conservation, regardless of what they (native bees) do for us or for the ecosystem,” Woodard said. “They deserve protection.”

But pesticides, climate change and limited food resources – among other factors – have disrupted native bees’ habitats, leading to a decline in their population, Woodard said. This habitat destruction, coupled with the importance of native bees in sustaining local plants, has driven Bruin Beekeepers’ advocacy for native bees, said Zabryanskiy.

The club’s first native bee project began in 2019 in the Mildred E. Mathias Botanical Garden. What was affectionately named “the bee hotel” was assembled from stacks of chopped bamboo in a box of recycled and reclaimed wood. It encouraged native bee conservation by providing safe habitats for native bees, who tend not to live in hives. It later went on to win the sustainability project of the year award at UCLA’s Green Gala.

While honeybees might have been the more expected choice for the project, Fox and his cofounders chose to focus on native bees because of the risks they face compared to honeybees.

“We really wanted to, at least in the beginning, hammer home the whole conservation aspect,” he said.

However, Zabryanskiy and her peers recently found there were more effective ways to support native bees on campus. They decided to retire the original native bee hotel project to focus on these other methods.

“We looked more into research and found that the native bees of Southern California don’t really live in hotels like that close together,” Zabryanskiy explained. “So we came up with a solution.”

The solution in question? On the rooftop, Soto pulls out a chunk of a log attached to a long pole of rebar, with holes drilled in the log. To me, it looks like an aerated marshmallow on a stick, a la s’mores. But to native bees, it looks like home.

“These holes are now nests for native bees,” Soto said.

He explained that some native bees will lay their eggs in the holes. The homes will then be placed around campus, displaying scannable QR codes with more information on native bees to educate students. Bee education is a central part of the club’s mission,

Tang said. At general meetings, the club presents on topics such as the differences between native bees and honeybees – Tang’s favorite topic – and explores bees around the world. Bruin Beekeepers also educates members about the relationship between flowers and bees for Valentine’s Day, in what Tang calls “the blooms and the bees.”

Bruin Beekeepers also offers and subsidizes the California Master Beekeeper course – a class for any California bee enthusiast to become a registered California Beekeeper. The course features lectures, self-guided notes, a practical exam and a written test, Zabryanskiy explained.

“Everyone at UCLA passes (the course) because we do put a lot of emphasis on it,” Zabryanskiy said.

But the hives aren’t just for beekeepers – they’re also open for research. Bruin Beekeepers encourages bee research, a field Soto said is understudied at UCLA and currently lacks resources.

While on the roof talking to Soto, I’m able to witness the first use of the hives for research. Kayla Law, a third-year biology student and member of Bruin Beekeepers, arrived with a small group of fellow students to study the bees’ memory in an experiment for a class.

Zabryanskiy hopes that researchers can use the club’s hives to study honeybees as well as native bees.

“We don’t really know the effects of urban life on native bees in Southern California,” Zabryanskiy said. “We don’t have that much research on it now.”

Bruin Beekeepers’ projects, including its original bee hotels, helped UCLA achieve its Bee Campus USA certification in 2020. The Bee Campus USA certification encourages universities to create habitats that support pollinators and discourage pesticides while also educating students about bee conservation, said Laura Rost, the Bee City USA and Bee Campus USA coordinator.

As UCLA reaffirms its commitment to bee conservation, there’s a lot of buzz around Bruin Beekeepers’ plans for the future. The club’s rooftop hives aren’t currently ready for honey production, but that could change soon.

“The goal is in a few years to have all the

honey in the dining halls be sourced from here,” Zabryanskiy said. “Maybe eventually we’ll sell it.”

Soto envisioned the honey stocking the Community Programs Office Food Closet, which provides free food to all students.

The second time I make it to the rooftop for a tour of the hives, I’m still wary but not as scared. The wind is higher today; it kicks at the back of my coat, and Zabryanskiy and I have to raise our voices to be heard over it. Yet the clunky machinery on the rooftop feels oddly navigable, and the bright red signs warning me about live bees on the roof are less foreboding than before.

A bee follows me around the rooftop as we move from the hives to the storage shed, like an odd welcoming committee. But when I hear its telltale buzzing circling my head, I stay still.

I don’t close my eyes. ♦

written by BREANNA DIAZ

designed by AMELIA WALKER

photographed by ALEX DRISCOLL

written by BREANNA DIAZ

designed by AMELIA WALKER

photographed by ALEX DRISCOLL

Daniel Blecker just wanted to watch “Glee.”

To a 12-year-old living in Switzerland, nothing seemed cooler than American television shows. At the time, “Glee” was at its peak, and Blecker yearned to join the fandom.

The only problem? There was no real way for the UCLA alumnus to watch American TV in his home country.

Blecker’s fruitless search for “Glee” eventually came to an end with the help of his older sister. After she introduced him to an online streaming site hosting American shows, Blecker had the entertainment he sought at his fingertips.

But in his search for “Glee,” another title caught Blecker’s eye: “Survivor.” On the hit CBS show, 18 contestants find themselves stranded on a tropical island, grouped into tribes to compete against each other for a million-dollar prize. Since premiering in May 2000, the show has become a cult classic. It has

now aired 43 seasons and boasts a 73% audience score on Rotten Tomatoes.

Blecker began watching out of curiosity, but he became a super fan almost immediately – he quickly devoured all 25 seasons that existed at the time. All he could do now was eagerly await each new episode.

When Blecker was applying to colleges in the United States, he knew some universities had their own “Survivor” clubs – and rather large ones, too. These clubs weren’t simply congregations of fans. Rather, these organizations produced their own versions of the show, often operating on shoestring budgets. “Survivor Maryland” at the University of Maryland, for example, has aired seven seasons. But Blecker learned in 2019 that there was no analogue to the reality show at UCLA.

“I thought, ‘That’s a shame,’ because I’ve been waiting six years (to) hang out and fangirl about ‘Survivor,’” Blecker said.

Taking matters into his own hands, Blecker turned

“I’ve been waiting six years (to) hang out and fangirl about ‘Survivor.’”

to Reddit to find other people who were interested in playing “Survivor” at UCLA. Alumnus Andre Chan reached out to Blecker, and together they began planning the production right in Blecker’s Sunset Village dorm.

Now, Survivor @ UCLA is a growing group of reality television fans who produce their own version of the show. The club replicates the high-stakes challenges of the original program by recruiting students to compete over 10 weeks for a grand prize of $100.

On a breezy January day in 2023, the Survivor @

UCLA production team has arranged a set of sorts beside Powell Library. The ground was marked to show contestants where to stand, and a homemade clay statue of a snake eating its own tail sat atop a column. Two tribes entered the scene on a producer’s signal.

It was the first day of filming for season four, and each tribe was antsy. The 16 players were finally meeting their teammates, whom they’ll rely on to win challenges but may ultimately betray in the hopes of winning the grand prize. Each player was dressed in either green or purple, only they didn’t know what exactly their tribes represented.

Evan Starr, Survivor @ UCLA president, jumped into his host spiel, welcoming each of the players onto the show. Starr, a fourth-year anthropology and cognitive science student, donned a bright orange trucker hat emblazoned with the “Survivor” logo. As he spoke, each player received a bandana corresponding to their tribe’s color. They admired their new bandanas and decided the best placement for them – around their heads or tucked into their pockets – while Starr finally revealed the theme of the season.

“It’s pre-meds versus the world,” he announced. The tribes broke out in surprised laughter.

That’s not really the theme though, Starr admitted. This season is concerned with the idea of the moral dilemma, forcing the two tribes of snakes and doves to make ethicallycharged decisions.

Each season is built around a certain theme, Starr said, and the casting department chooses contestants whose personalities best align with that theme. Season three pitted three tribes of six players against each other in a game of brains versus beauty versus brawn. Another season split contestants into North versus South Campus rivalries. This year, the production crew decided to hold off on announcing the theme of the season until the first day of filming in order to avoid contestants feeling like they had to play a certain character, rather than be themselves.

For the snakes, Starr said the casting team chose people who seem more willing to lie and backstab, while the doves

are loyal – maybe even to a fault. Ultimately, Starr said the production team designs the game to make the players confront who they think they are and what values they stand for. Some players may consider themselves loyal and incapable of betraying a teammate, but in the heat of competition, Starr said that no decision is set in stone.

“The whole idea is about … how you play the game and how that changes,” Starr said.

This year, more than 50 people applied to be one of the 16 contestants ultimately selected. But Survivor @ UCLA has not always been so popular – the organization comes from

Some players may consider themselves loyal and incapable of betraying a teammate, but in the heat of competition, Starr said that no decision is set in stone.

humble beginnings.

A few weeks after Survivor @ UCLA was founded, COVID-19 became a pandemic, forcing Blecker back to his home country. To reconnect with the UCLA community, Blecker and Chan decided to film “Survivor @ UCLA” online with the help of a two-person production crew recruited on Facebook.

From their own homes, 12 contestants played online puzzles and tackled challenges such as balancing toilet paper on one arm while standing on one leg, Blecker said. The small production crew was in charge of developing the challenges and recording the game via Zoom.

“We planned it of course, but we all kind of went in with a blind eye,” Blecker said. “We didn’t really know how (it was)

going to work online and if people were going to show up.”

After seeing a Facebook post searching for contestants, “Survivor” fan Starr decided to compete in the inaugural season of “Survivor @ UCLA.” After becoming the show’s first-ever winner, he joined the production team before becoming president of the club this year.

The first two seasons of “Survivor @ UCLA,” filmed entirely on Zoom, never aired on the club’s YouTube channel, Starr said, noting that the production quality was not up to par. But the return to campus in fall 2021 meant Survivor @ UCLA could finally grow. At the Enormous Activities Fair that year, Blecker said the club had more than 100 people sign the interest form, and the number of contestant applicants doubled from 30 for season two to 60 for season three. Now, the club is airing episodes of season three, its first in-person season. As the production team has grown, Starr said the club has streamlined its production, splitting into committees in charge of casting, filming and editing, props, and challenges and twists. Before the start of filming, the production team meets to brainstorm ideas for themes and games. Although they draw inspiration from challenges seen in the original show, members of the team take creative liberties when inventing plot twists and games of their own.

For the first day of filming, the production crew developed a team-based challenge. Only a few minutes after meeting, each tribe had to complete a puzzle – but only after two of its members trekked down Janss Steps blindfolded to retrieve the puzzle pieces. Although the contestants didn’t know their tribe assignments until a few minutes before, they’re already beginning to embrace the characteristics associated with their group.

During the first challenge, the doves kept their heads down and collaborated to try to solve the puzzle first. The snakes, however, weren’t afraid to play dirty. They sent one of their own to watch the doves decipher the puzzle, hoping to get a hint of the answer.

“People go from normal-person mode to realityTV mode when there’s an iPhone (camera) on

them,” said Elsa Servantez, a third-year philosophy major and production team member.

Sarahbeth Zohrehvand, a fourth-year psychology student, started out as a contestant on the first season and now heads the casting and contestant relationships committee. The application for contestants aims to draw out key personality traits in order to cast people in certain tribes, she said. This year, applicants also self-identified traits about themselves that helped pin

them as snakes or doves, such as being reserved or friendly. Above all else, the casting committee looks for people who have the energy and enthusiasm for the game, Zohrehvand added.

Beyond personality changes, Survivor @ UCLA becomes an all-consuming extracurricular for some of the players. Simona Lewis, a secondyear sociology student and casting department member, competed in season three. During her run on the show, Survivor @ UCLA became her social life, she said.

To be the last player standing requires strategic alliance-building and backstabbing, Lewis said. In any free moment, Lewis would schedule frantic FaceTime calls and meetups with her fellow castmates, discussing the progress of the game as more and more players were kicked off.

With the show forcing tribes to work together but also vote each other off, dramatic twists are the natural result. Early in the game, Lewis said it’s important for players to find their closest allies and choose who to target, but that is not always enough to stay in the game. The day Lewis was eliminated, her two most trusted partners flipped on her and voted her off.

Playing “Survivor” puts moral limits on the line, said

“People go from normal-person mode to reality-TV mode when there’s an iPhone (camera) on them.”

Austin McBride, a third-year physiological science student and season three cast member. In the reality TV bubble, McBride had to let go of his nice-guy personality and lie to people in the hopes of being the sole survivor.

“I like to have genuine conversations and relationships,” McBride said. “But in the game, I was like, ‘How can I be the most manipulative? Can I make people become enemies?’”

But the real storyline for the season emerges in the editing process, said Eli Kupetz, a third-year political science student. Kupetz heads the filming and editing committee, having joined the “Survivor” production crew as a second-year student. There are so many different players and perspectives in the game, Kupetz said, that it’s up to the editor to decide how to portray the information to the audience while building suspense.

Kupetz is currently editing the second half of season three. Once season four is finished filming at the end of the quarter, the episodes will be edited and posted on the club’s YouTube channel in a year’s time. Meanwhile, the club hopes to get started casting the next season, with plans for filming in spring quarter, he said.

Before they get ahead of themselves, the Survivor @ UCLA crew members have to wrap up the season at hand. After the first elimination night of the season, Starr switched from host to president mode. Producers blew candles out, gathered their props and led the tribes to Bunche Hall’s Palm Court, the site of the night’s challenge.

Under the shadowy trees, Starr began explaining the rules of the game. In this event, one player from each tribe will have to balance a fake skull on one hand while trying to knock the other player’s skull down. It may have been early evening, but there was still one more clash between tribes left before they could pack up for the night.

For Starr, Survivor @ UCLA means bringing the thrill of the original show’s challenges to campus. Watching the club grow from its shaky start to full-blown production is a source of Starr’s pride. Once he graduates, Survivor @ UCLA is the legacy he’ll leave behind. But Starr acknowledges playing “Survivor” is not for the weak.

“Last season, we had a girl who got voted out,” Starr said. “(She) said, ‘Well, I can finally focus on my homework.’”

“I like to have genuine conversations and relationships. But in the game, I was like, ‘How can I be the most manipulative? Can I make people become enemies?’“

In August, Casper Hsu found the trek to campus from his dorm more difficult than usual. The distance to class and the number of stairways he had to climb were not the only obstacles the fourth-year economics student faced. There was heat. Extreme heat.

Extreme heat is one of the deadliest extreme weather events, leading to the most fatalities of any weather emergency each year. According to the Los Angeles Times, the 2022 LA summer heat wave was possibly the worst September heat wave on record, with temperatures consistently trending upward of 100 degrees Fahrenheit. The City of LA issued an excessive heat warning from Aug. 31 to Sept. 9, alerting residents to the grave health risks posed by the temperatures.

The effects of the heat extended to campus and beyond. From overwhelming UCLA’s hospital with patients to exacerbating socioeconomic disparities, the heat wave exposed the dangers of an unprepared and unaware community. Now, six months later, the true toll of the disaster on both UCLA and LA is still being revealed.

On Sept. 5, UCLA shut down air conditioning and access to 34 buildings across campus. Martin Lee, a professor in the biostatistics department, taught Biostatistics 100A: “Introduction to Biostatistics” during summer session C. He said that he and other faculty members received notifications from UCLA asking them to be aware of the risks of the heat, especially if their class involved outdoor

activities. Lee added that, while his lecture took place earlier in the morning and in a classroom where the conditions were bearable, he noticed that attendance dropped as the temperatures rose.

“Let’s face it, August in LA is never a cool period of time,” Lee said. “But ... I can still remember summers going way back being a lot easier to deal with than certainly the last decade or so.”

Heat and dryness are typical features of California’s weather. However, climate change has intensified these events, said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability.

“One of the things to realize is that climate change most prominently exacerbates existing physical hazards,” he said. “Often it’s not creating new physical events out of the ether, but it’s amplifying them.”

But, Swain said, residents may not realize the danger of these high-intensity climate events.

Anna Jackanich, an emergency medicine resident physician at UCLA, explained that heat can cause health conditions such as fatigue, dehydration and headaches. Heat exhaustion sends many patients to the hospital when temperatures rise, she said. The effects, however, can quickly manifest into a more severe condition: heat stroke, which occurs when the body can no longer regulate its temperature.

“The symptoms of heat stroke can actually be pretty dangerous,” she said. “It can lead to death.”

"It’s just crazy to think that someone could be so sick from heat exposure."

Many patients came to the emergency room exhibiting signs of heat exhaustion and heat stroke during the heat wave: nausea, confusion and even seizures, Jackanich said. However, the heat can also exacerbate existing conditions because of dehydration or lead to physical injury because of fatigue. Many other patients came with kidney stones, injuries caused by collapse or other conditions, she added.

“It’s just crazy to think that someone could be so sick from heat exposure,” she said.

Students on campus over the summer were no strangers to the symptoms of heat exposure Jackanich described. Ruochen Li, a fourth-year biochemistry student, took Biostatistics 100A over the summer. During this time, Li lived in Saxon Suites without air conditioning. Even with the ice packs he made using campus ice machines, Li said he still struggled to fall asleep at night. Eventually, that lack of sleep affected his studies.

“I found (it) hard to keep focused at the lecture,” he said.

For Sarah Huang, a third-year human biology and society student, the symptoms went beyond disrupted sleep patterns. The heat, coupled with the demands of her academics and extracurriculars, led to a sudden fever.

“I think I got sick just due to extreme exhaustion and fatigue,” Huang said. “My body shut down.”

Later in the summer, Huang participated in band camp with the UCLA Bruin Marching Band. While the camp occurred in September, after the peak of the heat wave, the 12-hour outdoor practices took a toll on Huang and her peers. She added that the band’s efforts to mitigate the effects of the heat, such as taking mandatory water breaks and cooling down in air-conditioned rooms, did not fix their situation.

Angelique Campen, a clinical professor of emergency medicine, explained that heat can affect anyone, including young individuals like Li and Huang. At the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, the ER was overrun with struggling

patients of all ages.

This increase in the number of patients led to a strain on hospital resources. Both Campen and Jackanich described the scramble as they sought out fans, looked for ice and prepared cooling blankets. These overwhelmed systems within hospitals only reflected the realities of outside communities.

David Eisenman, a professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine and the Fielding School of Public Health, tracked the effects of the heat wave on entire communities. His research quantified the effects of the heat on Southern California by mapping excess ER visits – calculated by comparing ER visits on days with extreme heat versus non-heat days – on both the county and ZIP code levels. His studies found that, for every day of extreme heat, there are eight additional deaths within LA County. The more days of extreme heat there are, the more the number of fatalities increases.

Eisenman and his colleagues also found that not every community experiences extreme heat the same way. During the heat wave, ZIP code 90210, which covers parts of Beverly Hills, had two excess ER visits daily. The neighboring ZIP code 90024, which covers UCLA, had three. On the other hand, ZIP code 90037, covering parts of South LA, had 17. As Eisenman explained, these disparities reflect long histories of discriminatory policies and structures.

“Why is this one neighborhood so much more affected than the other?” he said. “This almost always comes down to issues of equity, fairness in housing, historical racism in the form of redlining, access to health care.”

Despite the risks of heat, there has been a lack of data transparency in the immediate aftermath of a heat wave, Eisenman said. He added that, while LA County does keep records of the effects of the heat, they are not made public. Public health authorities are not adequately informing communities about the dangers posed by heat waves, he explained.

While months have passed since the heat wave, the repercussions still persist. Often, relentless rain can be linked to the extreme temperatures of the summer, Swain explained. He said that higher temperatures increase the atmosphere’s capacity to hold water. Eventually, that water must return to land as rain.

Like the summer heat wave, January’s winter storms had devastating impacts on unprepared residents. According to the LA Times, the storms resulted in at least 22 fatalities. NPR reported that 2.6 million homes using Pacific Gas and Electric – California’s largest electricity provider – experienced power outages. Many freeways, including the Pacific Coast Highway and Interstate 5, were partially blocked because of mudslides or flooding.

According to the LA Times, this particular storm

was not the result of global warming. Patterns of heat followed by precipitation are normal to California’s climate. However, climate change will only exacerbate this cycle, Swain said. The solution to this problem is difficult and complex: stopping climate change.

“We can’t directly do anything about the extreme weather events except to the extent to which we mitigate and eventually halt climate change,” he said.

underway, is to ensure safe environmental conditions in the older (buildings),” he said. “Because our campus is well over 100 years old now.”

On a communitywide scale, Eisenman said counties such as LA should release data on the effects of heat.

“They (LA County) need to educate them (residents) going forward about heat, and how to prevent their own sicknesses and how to stay cool,” he said.

However, that does not mean individuals are hopeless when it comes to mitigating these conditions. Lee said that UCLA needs infrastructure changes on campus in order to combat the effects of heat. He explained that older buildings, such as Moore Hall, tend to become unbearably hot in comparison to their newer counterparts.

“What certainly needs to be done, if it’s not already

But one of the most important steps needed is a collective acknowledgment of how dangerous the heat can truly be, Eisenman said.

“Extreme heat is, on average each year, the No. 1 weather-related emergency for deaths across the nation, more than any other kind of weather-related event,” he said. “But if you look at the news, what do you see from pictures? You see pictures of people going to the beach.” ♦

"The

is difficult

All the world’s a stage,” William Shakespeare wrote. But for whom? Whose triumphs are celebrated, and whose losses mourned?

The shows that brought Broadway and Shakespeare’s Globe glittering to life were not made with diverse audiences in mind. A 2018 study found that 94% of Broadway shows were led by white directors, while nearly two-thirds of the roles on Broadway and the 18 largest nonprofit theater companies in New York City were played by white actors. As the entertainment industry continues to grapple with its history of marginalization, some artists are raising the question: Do the classics still matter?

According to theater magazine Backstage, a classic play can be loosely defined by its features of elevated language and an epic plot. Many of these plays, such as

those written by Shakespeare and Anton Chekhov, were released centuries ago without considering the stories of diverse audiences. Now, as people of color, the LGBTQ+ community and other marginalized groups push to be included in the theater industry, the value of these plays is debated.

Sara Ryung Clement, a lecturer in the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television, said the theater industry is hard to crack for people of color because audiences are so used to seeing white actors in starring roles.

“It’s hard to visualize something until you’re asked to break a paradigm about it,” Clement said.

Dominic Taylor, a professor in the departments of African American studies and film, theater and television, said racial economic disparities further exacerbate the issue. With the median wealth value of Black households 7.8 times lower than that of white families in 2019, Black audiences have not always had access to expensive theater performances, he said.

But at UCLA, the Color Box Production Company spotlights works written by diverse creators and challenges the limitations of theater.

Since 2017, the Color Box has aimed to create an inclusive performance space for students at UCLA. Each quarter, the student-run organization aims to push the boundaries of contemporary performance art. Keeping with this tradition, the company is performing LinManuel Miranda and Quiara Alegría Hudes’ “In the Heights” in the winter. The musical tells the story of the dreams and struggles of a tight-knit Latino community in Washington Heights, New York.

Isaiah Mateas, the director of “In the Heights” and a third-year theater student, said the Color Box chose the 2005 show because they wanted to perform a piece already centered on minority communities. Although the company has reimagined older works, such as a sapphic production of “Grease,” in the past, Mateas said he felt it was time to take on a work specifically exploring themes important to marginalized groups.

For Madurya Suresh, a third-year linguistics and computer science student and the company’s managing director, diversity in theater is not just a concept – it’s a commitment. In her previous theater experiences, Suresh said she was acutely aware that her peers did not

While older pieces of theater offer an escape from reality, people of color often don’t have the luxury of escaping from constant prejudice and marginalization.

look like her. In comparison, the Color Box offered her a safe platform to proudly tell the stories of marginalized communities. She pointed to how the company’s current musical allows students to infuse elements of Los Angeles’ own tight-knit Latino community into its production.

The rehearsals felt very much like the musical itself: a vibrant community.

Surrounded by a cornucopia of pizza boxes and Veggie Grill takeout containers, the cast and crew came to life in a hodgepodge of low-rise skinny jeans and sweatpants. Bursts of vocal riffs and choreographed dances were interrupted by jokes, and Mateas himself continuously stepped into the performance space to build chemistry between his actors.

The cast specifically experimented with minute character interactions in the musical’s titular ensemble number to establish familiarity among characters whom the audience doesn’t know. Small details, such as the ladies of the hair salon walking in coordination with each other and strategically angling the performers diagonally across the stage, contributed to Mateas’ vision of the production.

During a rare rehearsal break, second-year theater student Al Hiciano De Gongora and first-year playwriting graduate student Mario Vega stepped outside for an interview. De Gongora plays Abuela Claudia, the matriarch and acting grandmother of the “In the Heights” barrio. Vega plays Kevin Rosario, the endlessly proud father of one of the main characters, Nina.

For De Gongora, who has a Dominican and Cuban background and was born in Puerto Rico, “In the Heights” closely resonates with their identity. De Gongora said their character reminds them of their own mother and grandmother. All three women fled from Cuba to the United States, and De Gongora attributes their current life and opportunities to their family’s courage.

More importantly, the members of the Color Box understand what it is like to be a minority, De Gongora said. Learning that the performance space was supportive of people from all backgrounds was especially significant to them.

Vega said “In the Heights” balances the whimsical escapism of musical theater with the real-world struggles people of color face today. While older pieces of theater offer an escape from reality, Vega said people of color often don’t have the luxury of escaping from constant prejudice and marginalization. “In the Heights” strikes a balance of accurately portraying xenophobia and gentrification while also using a magical neighborhood of singers

and dancers to add some levity, he added.

As if to illustrate his point, he was interrupted by a burst of music from one of the musical’s ensemble numbers “96,000,” in which the characters discover the bodega has sold a winning lottery ticket worth $96,000 and wonder what they would do if they had a small fortune.

“I mean, they’re dancing about money right now,” Vega laughed.

At another rehearsal across campus, there are no choreographed musical numbers, but the fervent exchanges of old English are equally energizing.

The Shakespeare Company at UCLA aims to reinterpret Shakespeare’s works to reflect modern realities. Past productions include “Ophelia,” as well as a rendition of “King Lear” that reinterpreted the play as a dark comedy illustrating the tumultuous state of American politics.

The director behind this quarter’s production is Cerulean Long, a second-year theater student. Long chose to direct her all-time favorite play, Joe Calarco’s 1998 piece, “Shakespeare’s R&J,” which is about four students in a Catholic school who find a creative outlet by sneaking out to rehearse Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet.”

Some audiences may think “Romeo and Juliet” is just an overdone love story, Long said. But because the Shakespeare Company at UCLA’s rendition of

Take a risk on some new work. Shakespeare is just some dude.”

“Shakespeare’s R&J” emphasizes and explores gender roles, the story remains pertinent today, she explained.

The original “Shakespeare’s R&J” focuses on four Catholic school boys, but the Shakespeare Company at UCLA’s production translates the narrative into a sapphic love story set in a dystopian future, tackling themes of lust, liberation, disobedience and conformity, Long said. The freshness of Shakespeare came to fruition in Macgowan Hall 101, where the cast and crew of “Shakespeare’s R&J” lounged in foldout chairs and laughed about astrology signs before rehearsal in a sparsely furnished dance studio. However, their body language shifted from lighthearted informality to focused intensity as they began their first read through.

Throughout the play, the main characters, aptly named Students One, Two, Three and Four, faithfully recite Shakespeare’s Old English text. Shakespeare’s language, once so familiar, is transformed as they take on unique personalities suited to the 21st century. A particular recitation of “Sonnet 18: Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” was hot-blooded, thrumming with the intensity of restrained adoration rather than its expected tenderness.

encourages her fellow students to sneak out and recite a prohibited copy of “Romeo and Juliet.” At this point, the play moves from modern English to the language of the bard. Chun empathizes with her character, who knows that the world doesn’t accept her queerness and uses “Romeo and Juliet” as an outlet for freedom.

“I see her (Student One) very much as someone who’s trying to explore and grow but doesn’t really know how,” Chun said.

Emily Fritz, a third-year English student, plays Student Two, the adaptation’s equivalent of Juliet. In contrast to original performances of “Romeo and Juliet,” in which only men were able to perform, “Shakespeare’s R&J” is a nuanced exploration of what love means for women without men present, Fritz said. Through “Shakespeare’s R&J,” audiences can analyze the concept of love itself from a female perspective, she added.

“We’re figuring out how to craft it (Shakespeare’s work) in a way that we can still use his words to discuss our modern world,” Fritz said.

On the surface, the Shakespeare Company at UCLA’s “Shakespeare’s R&J” seems to live in stark contrast to the Color Box’s “In the Heights”– and cast members in both groups expressed different opinions on the value of tradition in theater.

Between practicing elaborate choreography and workshopping dialogue inflections, De Gongora said updating and diversifying traditional plays is important. However, they added, this work often overshadows newer works created by people of color.

Vega agreed, acknowledging that Shakespeare’s stories continue to influence media today but advising theater companies to focus on works that reflect and champion their local communities instead.

You realize that we are all more like each other than we think.”

“Take a risk on some new work,” Vega said. “Shakespeare is just some dude. Everyone is just some dude.”

However, other students continue to find magic and opportunity in centuries-old work. Blaire Battle, a fourthyear theater student and the executive director of the Shakespeare Company at UCLA, said they fell in love with Shakespeare because of the ubiquitous influence of his text. After studying enough Shakespeare, they realized his work, perhaps surprisingly, lends itself to gender bending and fluidity.

Battle said the reason Shakespeare’s works are so easily reexamined as queer stories is partially because they have always had the potential to be queer. Despite popular notions, queer people have always been around, they said.

“Shakespeare wouldn’t have called it this, but I think modern scholars would just call (his productions) camp. There’s a fun to it. I find (it) endlessly refreshing,” Battle said.

Despite their different choices in the texts they choose to perform, members of both companies both strive to assert themselves in an industry that has so often excluded them.

Brooke Lebidine, a second-year theater student and associate director of “In the Heights,” said a major focus of the Color Box is ensuring their performances are informed by the actors’ backgrounds and lived experiences. The company’s selection of productions is always deliberate, she added, pointing to last quarter’s

performance of “Jane: Abortion and the Underground,” which focuses on the history of abortion rights in Chicago and reflects ongoing debates about states’ anti-abortion laws.

De Gongora added that diverse narratives can unite audiences, even if people feel that they can’t personally relate to others’ stories.

“It’s the moment you sit in the theater and actually go, that you realize that we are all more like each other than we think,” they said.