7 minute read

world

JOINT COLUMN | Academia is rewarding knowledge commodification, not contribution

Amy Wax’s racist remarks towards her students and various demographics such as the Asian American community have caused great controversy. For the sake of our own sanity and yours, we will not give further publicity to her exact words. To do so would be akin to catering to the bully. But Wax’s willingness to embroil herself in controversies is a topic worth exploring.

Enrollment in Wax’s law seminars has seen a dramatic decline after her comments on race and immigration sparked a national controversy. Though counterintuitive to her position as a professor, student dissatisfaction and low participation don’t matter to her. After all, law students are hardly her audience.

Richard Schechner is often credited for coining the notion of performance theory. As a concept, performativity does not only include a theatrical performance on stage; it permeates every fiber of the world.

While you don’t need to agree with Schechner’s theory, it is hard to argue against the fact that there is often a performative aspect to the way we go about our daily lives. From mundane things such as the clothes one wears to decisions like the size of the diamond one buys for their fiancé, every action sends a signal — they are all performances of some sorts. The more dramatic the performance, the greater attention it attracts. One might argue that Wax has put on quite the performance herself.

Can you name the second most controversial professor at Penn? Hopefully not. Wax has differentiated herself from the crowd with her performance. She might be an extreme case, but society is no stranger to differentiation. You don’t pass the resume screen with average statistics, nor do you get promoted by being middle of the pack. There is a need to be seen.

Every performance requires an evaluative metric. For academia, it’s citations. We measure professors by the number of citations they have and the publicity they muster. Theories are not only vehicles of knowledge exploration, but a method to build social capital for the theorist. This creates a fundamental tension in the world of academia between the pursuit and commodification of knowledge. It’s an evident example of incentive misalignment.

The quantification of a university scholar’s success is already damaging. It is further exacerbated by the pitifully limited means at our disposal to do so. We claim that students shouldn’t be evaluated purely on test scores, and instead be looked at holistically. However, we neglect to recognize that professors and scholars deserve the same treatment. A high h-index or impact factor does not define a professor.

What about the strength of their teaching abilities? What about their efforts to maintain a safe campus community? However, research candidates are often told early on in their careers to focus on narrow areas of research instead of teaching. After all, teaching is rarely the key to tenureship. And yet, the frontier of knowledge that research represents is only valuable if it can be inherited, and the scholars of tomorrow are the students of today.

Here’s a simple observation. In order to get citations, you must get noticed. Now, interestingly enough, you don’t need people to agree with you. People can cite you in fervent agreement or blatant dispute. After all, simple citation count doesn’t discern between positive and negative citations.

The lack of other dimensionalities fosters a race to the bottom. In marketing, the race to the bottom is pure price competition. Although it’s a situation that companies strive to avoid, the prices are bounded by the costs of product production and sale. Academia’s race to the bottom has to do with the extent to which academics can distinguish themselves. Normally, the act of differentiation quickly gets costly through reputational burdens and job security. But tenure often absorbs these costs and provides a hefty buffer of safety.

Yet the cost doesn’t disappear — it is transferred. Students who belong to marginalized communities might have their well-being and safety damaged by professors like Amy Wax. The psychological harm is unseen, but it is every bit as real as physical harm. The institution and academia overall also bear reputational burdens as a result.

Tenureship attracts talented scholars worldwide, bolsters economic stability, and provides greater freedom for faculty to “pursue research and innovation and draw evidence-based conclusions free from corporate or political pressure,” as defined by the American Association of University Professors. Simply put, tenureship offers the freedom to posit, theorize, publish, and debate in a scholarly setting. But with freedom comes responsibility. And tenureship has allowed Wax’s show to go on for far too long. As it stands today, tenureship allows performativity to transform academia into a contest of publicity, not brilliance.

ANDREW LOU is a Wharton and Engineering junior studying finance, statistics, and computer science from Connecticut. His email is alou6683@ wharton.upenn.edu.

SAM ZOU is a College senior studying political science from Shenzhen, China. His email is zous@thedp.com.

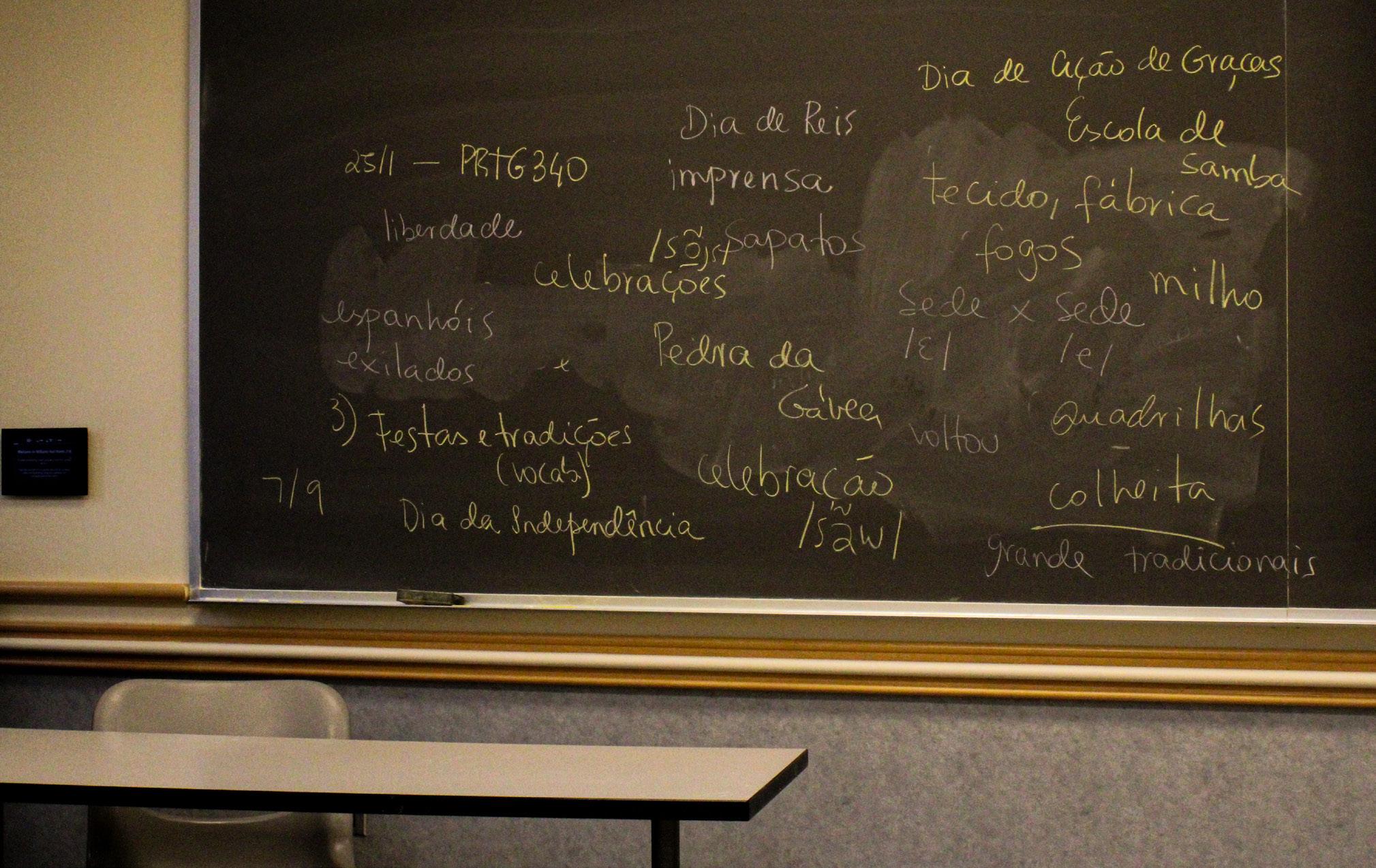

Penn’s foreign language requirement is insufficient

THE AIYER ASSESSMENT | After completing four

Before coming to Penn, I made the goal for myself that by the time I graduated college, I would be, at the very least, trilingual. I am a native English speaker, studied Mandarin for 15 years from preschool to high school, and am now learning Spanish at Penn. However, by the end of my fourth semester of Spanish, I doubt that I will be able to call myself trilingual.

In the College of Arts and Sciences, the foreign language requirement “affords unique access to a different culture and its ways of life and thought.” The Wharton School’s foreign language requirement is intended to allow students to “engage in an important form of critical thinking.”

Yet, Penn’s requirement is futile in truly equipping students with foreign language proficiency.

Penn’s foreign language requirement is inconsistent. The College and the School of Nursing require four semesters of a foreign language. Wharton requires only two semesters and the School of Engineering and Applied Science has no requirement.

The United States Foreign Service Institute has split up languages by how difficult it is for a native English speaker to reach fluency, with Group 1 languages being the easiest to learn and Group 4 languages being the hardest. Following this idea, it takes a minimum of 480 hours to learn a Group 1 language, such as Spanish, French, or Italian. To learn slightly more difficult languages that fall in Groups 2 through 4, such as Hindi, Russian, and Chinese, it takes a minimum of 720 hours to reach basic fluency.

Let’s do the math. A typical Penn semester consists of around 15 weeks of classes. For a Group 1 language, such as Spanish, the first and second semester typically consist of one-hour classes four days a week. The third and fourth semesters typically consist of one-hour classes three days a week. Over four semesters, that adds up to approximately 210 hours of Spanish instruction. This is sufficient to fulfill the Penn language requirement in the College and Nursing School. Even making the generous assumption that students spend an equivalent number of hours studying outside of class, they still fall short of 480 hour mark. Within Wharton, most students stop after the second semester, thus, only receiving 120 hours of foreign language instruction. We see a similar phenomenon with

semesters, have students really reached proficiency?

Group 4 languages, such as Chinese. Similar to Spanish, semesters one and two of Chinese consists of one-hour classes four days a week; semesters three and four follow the same format. This adds up to a mere 240 hours across four semesters, which falls short of the 720 hours that are needed to reach proficiency in Chinese.

A significant facet of Penn education is its pre-professional culture. Our education is structured to provide us with the tools to thrive in the workforce and, more broadly, the real world, both of which are becoming increasingly globalized. As a result, monolingualism is no longer sufficient.

In the workforce, an increasing number of employers are searching for bilingual talent. In 2015, approximately 630,000 job postings were aimed at bilingual workers, compared to less than half that number of job postings in 2010. Given this trend, the number of job postings for bilingual workers has likely increased significantly in the seven years since.

Most Penn students’ first destinations after graduation lie in the banking or consulting sectors. One of the leading companies that was searching for bilingual workers was the Bank of America, which is popular amongst recently graduated Penn students

It makes sense that employers are searching for bilingual employees, given how multicultural our world is becoming. In the U.S., approximately 20% of residents are able to speak two or more languages, while the percentage is closer to 50 for the rest of the world. The ability to converse in more than one language opens doors, allowing us to communicate with people that we might not otherwise be able to.

There is no point in learning half of a foreign language. It is a waste of time, energy, and is a disservice to us as Penn students.

The solution to Penn’s predicament is simple. The University must strengthen its foreign language requirement across the four schools. Varying by the difficulty of the language, Penn’s language requirement should allow for enough hours of instruction to ensure that students reach fluency. This may mean more required semesters, longer classes, or more frequent instruction.

I understand that this might be an unpopular idea in the minds of most Penn students. Many of us came to university looking forward to the academic flexibility that we lacked access to in high school. I’ve heard complaints about how frustrating it is to fit foreign language into our already busy schedules and I’ll admit that I’ve voiced similar concerns in the past.

But at the end of the day, we came to Penn to receive an education that prepares us for the real world. By the time we graduate, we must have the capabilities to enter a multilingual society with both the language skills and cultural competence to thrive. It is Penn’s responsibility to provide us with the tools to do so.

SANGITHA AIYER is a College first year from Singapore. Her email is saiyer@sas.upenn.edu.