Despite many challenges facing the industry, the education, innovation, and diversification in DFW’s healthcare market has never been stronger.

BLACK MEN IN WHITE COATS

TCU’s Innovative Medical Curriculum

TCU’s Innovative Medical Curriculum

Despite many challenges facing the industry, the education, innovation, and diversification in DFW’s healthcare market has never been stronger.

TCU’s Innovative Medical Curriculum

TCU’s Innovative Medical Curriculum

In an industry beset by societal and financial challenges, healthcare continues to innovate.

healthcare is, at its heart, an optimistic industry. To enter the profession, one must believe in his or her ability to help make people feel better or prevent them from getting sick in the first place. Even in the face of the most daunting odds, those in the healthcare industry approach problems with hope and belief that they can make a change for the better. This attitude makes my job covering the North Texas healthcare industry endlessly interesting and fulfilling.

My mother is one of the best exemplars of this attitude. A nurse in Austin, she works in a psychiatric emergency room where people go when they are having a mental health crisis. Because of societal forces outside her control, a good portion will never reach what most of us would call a stable life. Even in the face of daunting challenges, she continues to do the best she can to help stabilize and treat these patients.

In this year’s D CEO Health Care Annual, we have several stories that showcase the resilience and belief in medicine. First, we have a profile on Dr. Dale Okorodudu (Page 80), a UTSW pulmonologist who spends his free time tackling the lack of diversity in medicine.

Even though there has been an erosion of trust in the medical profession and ever-present burnout, the Burnett School of Medicine at TCU graduated its first class this year. Our story examines the school’s innovative curriculum (page 84).

Lastly, our panel discussion is about the hospital of tomorrow, where industry experts give their thoughts on what is next for hospital design (page 88). Even after a year where half of all Texas hospitals lost money, the industry continues to look forward and innovate to better care for its patients. That’s the resilience of healthcare.

THE DEVOTED DOC Dr. Dale Okorodudu is on a mission to diversify the physician workforce. While barriers remain, progress is being made.

MIXING THEORY AND PRACTICE

Anne Burnett Marion School of Medicine at TCU graduated its first class under a unique curriculum.

THE HOSPITAL OF TOMORROW

Industry leaders discuss what’s now and what’s next in healthcare design and construction.

Will Maddox Healthcare Editor

What is “unhealed trauma,” and what are the signs?

Unhealed trauma is an individual’s internal experience of traumatic events that have not yet been processed in a healthy way. Signs of unhealed trauma can include hypervigilance, increased anxiety and feelings of panic, recurring patterns of dysfunction in interpersonal relationships, and myriad physiological ailments. In fact, survivors of trauma have a higher likelihood of medical ailments, such as heart disease, diabetes, and addiction.

Is it appropriate for a company to address mental health with employees?

Companies should take a position of support when it comes to addressing mental health with employees. Reminding employees of resources available to them, such as Employee Assistance Programs (EAP), mental health counseling through their health insurance, as well as any mental health days the company offers, could assist in linking struggling team members with the appropriate tools.

Can a past negative work experience be considered unhealed trauma? If so, what is the danger of carrying that over?

A past negative work experience could be considered an unhealed trauma in certain circumstances—particularly if the past environment caused damage in other areas of the employee’s life, such as a demotion which resulted in a loss of pay or being forced to switch to a new team which caused a loss in valuable relationships. Employers can help with this by asking pointed questions at onboarding such as “What worked at your past job and what did not?” or “Tell me about a work environment you’ve had where you’ve felt supported?” These are indirect ways to begin the conversation of what they’ve experienced in the past that they might be bringing into their current work situation.

What are professional/workplace signs an employee may have unhealed trauma?

An employee who has unhealed trauma may be disconnected from colleagues and/or be resistant to bonding with new coworkers, actively create toxicity within a team, or exhibit signs of unwarranted self-deprecation regarding their work performance. Conversely, an employee may never exhibit outward signs of unhealed trauma, so it behooves leadership to actively engage team members individually to keep a pulse on their current experience.

What are some services and offerings a company can have in place for employees to care for mental health issues?

The first and most important service a company can offer employees as they work through mental health issues, including unhealed trauma, is to offer an alternative experience than what they have experienced in the past. Direct supervisors and upper management have an amazing opportunity to be a part of an individual’s healing journey by offering a healthy and positive experience that challenges the negative one they experienced in the past. In addition, companies can offer peer support and mentorship programs that can give employees access to a safe space both at their level and above.

ABOUT THE EXPERT:

Catherine Richardson is a licensed professional counselor in Texas. In her clinical career that spans more than a decade, Richardson has participated in and led teams in various capacities, including clinical quality management, performance and compliance, risk management and crisis intervention and diversity, equity, and inclusion. In her work as therapist, she specializes in childhood trauma and play therapy, particularly enjoying her work with parents of traumatized children. Outside of work, her passions include history, yoga, trying every cuisine known to man, and globetrotting with her husband and two sons.

Well beyond borders. There’s no connection like the one to those who keep us safe and secure. That same bond is why Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas members know they can depend on a partner to be there... always encouraging us toward a healthier tomorrow. Whatever your state. Wherever the journey.

When it comes to your health, it’s only natural to want the best.

UT Southwestern has been named the #1 hospital in Texas* and one of the top 20 in the U.S. because we deliver on that promise. Eleven of our specialties are ranked among the nation’s best. And for seven years now, we’ve remained the #1 hospital in DFW.

Driven by a deep commitment to our community, UT Southwestern is advancing science and medicine so you can feel confident the best health care is right here when you need it.

Finding answers, changing lives. That’s what we do every day.

Nationally ranked in:

Cancer

Cardiology, Heart & Vascular Surgery

Diabetes & Endocrinology

Gastroenterology & GI Surgery

Geriatrics

Neurology & Neurosurgery

Obstetrics & Gynecology

Otolaryngology – Ear, Nose, Throat

Pulmonology & Lung Surgery

Rehabilitation

Urology

At Texas Health, we’re proud to say more North Texans choose us than any other health care system. From heart and vascular care to coughs and colds, we’re dedicated to giving you more ways to access your health care than ever before. With our ever-expanding hospital and urgent care locations to our video visits and at-home care options, we’re dedicated to making your health care more convenient so you can spend less time on figuring out your health care and more time on what matters most. That’s how Texas Health cares more.

What is unique about pediatric sports medicine?

Children and teenagers currently have more opportunities to train and excel at high levels in a wider variety of sports than ever before. These activities lead to particular challenges as a result of repetitive stress on small and immature bones, cartilage, and ligaments. Injuries and conditions affecting these developing structures are often unique to children and very different than those seen in adults. Fortunately, specialized pediatric sports medicine experts now research and treat these conditions.

Can you explain what makes Scottish Rite for Children a great fit for the care of a young, growing athlete?

Treating children and teenagers 100% of the time, our fellowship-trained pediatric sports medicine experts also specialize in pediatric orthopedics. As a result of our high volume of specialized care and research, we are consistently ranked as one of the top programs in the country. Our multidisciplinary team works together to surround a patient with complete and comprehensive care.

In addition to participating in national multicenter prospective study groups, Scottish Rite for Children has more than 240 active research studies with resultant innovative surgeries and technological advances to treat growing patients.

• Collaborate on specialized care, learning what motivates athletes to work toward their performance goals.

• Have experience with rare injuries, like osteochondritis dissecans and ulnar collateral ligament tears, as well as common ones, like ACL injuries and fractures.

• Engage before, during, and after surgery to achieve optimal outcomes for your growing athlete.

• Track athlete outcomes and adjust surgical techniques and rehabilitation accordingly.

Why does taking your teen athlete to children’s sports medicine matter?

Your young athlete’s body is still growing, making injuries and treatment strategies different than those in adults. We provide a comprehensive assessment, treatment, and expert advice for growing athletes with injuries and conditions that affect sports performance. We use special equipment and technology to find and correct techniques and mechanics to improve and refine sport performance. Our fellowship-trained sports medicine specialists have additional training that enables them to get kids moving and back on the field again—not just for one season but for as long as they desire. We offer comprehensive care and treatment through:

• Sports surgery

• Sports medicine primary care

• Sports physical therapy

• Athletic training

• Sports motion analysis

• Sports nutrition education

• Pediatric psychology care

• Athlete development

• Return to sport bridge training

ABOUT THE EXPERT: Philip L. Wilson, M.D., is an assistant chief of staff, director of the Center for Excellence in Sports Medicine and a pediatric orthopedic surgeon at Scottish Rite for Children. Dr. Wilson also serves as the medical director of the North Campus. He is a professor at UT Southwestern Medical Center and provides orthopedic trauma coverage at Children’s Medical Center of Dallas.

With the best pediatric orthopedic experts in the world on staff at Scottish Rite for Children, talented athletes like Myson never have to settle for standard care. We don’t chase the standard. We set it — for ourselves, our peers and our patients. scottishriteforchildren.org

story by WILL MADDOX

story by WILL MADDOX

to diversify the physician workforce to benefit all patients. While barriers remain, progress is being made one conversation at a time.

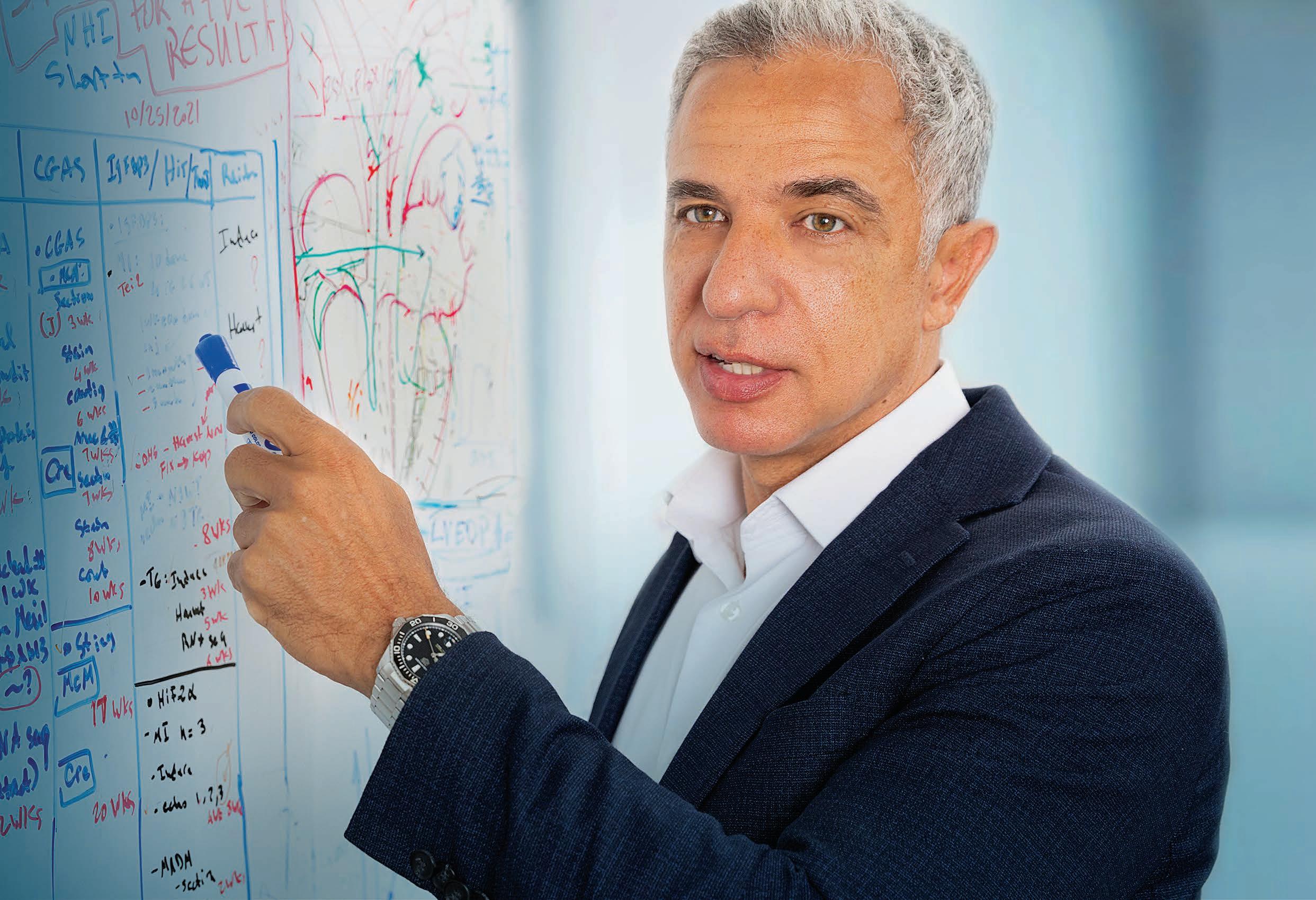

Dr. Dale Okorodudu is on a mission

Dr. Dale’s nonprofit provides communal support to those looking to enter the medical field.

Before launching Black Men in White Coats, Dr. Dale Okorodudu founded Diverse MedicineInc. in 2011.

The nonprofit’s goal is to increase ethnic and socioeconomic diversity in the field of medicine. In the decade-plus since being launched, it has organized mentorship opportunities for underrepresented students, hosted clinical case series where high school students meet to solve a medical case, youth summits, and MCAT preparation.

Providing support and community for ethnically diverse students is critical to increasing the number of doctors of color in the United States. Dr. Dale has long been moved to have an impact beyond his interactions in the exam room and feels called by both his talents and his faith to give back and help others join him to practice in medicine. “None of this was planned,” he says.

“If I see a problem and I have a solution for that, I want to be able to realize my gifts of vision and problem-solving.”

OKORODUDU NEVER FORGOT THE TIME HE was asked if he was studying to be a drug dealer. Dressed in sweats and a hoodie, he was a college student on a plane to a cousin’s wedding in Chicago when an older woman sat beside him. She spent the next two hours criticizing how he dressed and spoke, letting him know he would never amount to anything if he continued down his current path. When he got out his chemistry books to knock out some studying, she asked if he was studying to be a drug dealer.

He says he responded as amicably as possible but “went into his own little world” and counted the seconds until he could get off the plane. He remembers talking to his parents, who immigrated to the U.S. from Nigeria, about the experience. It was a seminal moment for him. “I thought, ‘Wow, people look at us and judge us completely on how we look.’ I want to do something about that.”

What the woman on the plane will never know was that she was sitting next to a future pulmonary and critical care physician who would go on to earn undergraduate and medical degrees from the University of Missouri. She will never know that he’d go on to be a resident at Duke University, earn a fellowship at UT Southwestern, and practice today as a triple-boarded pulmonologist, critical care physician, and internist.

The interaction on the plane was not the first or last time Dr. Dale (as he is known) experienced overt racism, and he persevered to become an excellent physician, a worthy goal for most people. But securing his own future was never going to be enough. Dr. Dale has spent more than a decade advocating for diversifying medicine, authoring several books, and founding numerous organizations to get more people who look like him in medicine.

To that end, Dr. Dale is featured in, and executive-produced, a documentary called, Black Men in

White Coats, released in 2021 to create awareness about the lack of diversity in medicine. The documentary shares stark truths that reveal the depth of the issue. More Black men were applying to medical school in 1978 than in 2014, and today just four percent of physicians are Black, although 13 percent of the country is Black. A 2021 study found that the number of Black students applying to medical school had stagnated in the previous decade. There are several medical schools in the country without any Black men in their classrooms and lecture halls, meaning the discussions and educational experiences of those training to be doctors is missing a key demographic—and all the life experience that comes with being Black in America.

In the documentary, dramatic music plays over a message that hits home in Dallas: “We need more Black men in white coats because we need to save the lives of more Black men.” The statistics support the assertion in the film. The life expectancy range in Dallas ZIP codes shines a light on the disparity. Locallly, the average ranges from more than 90 years in some areas of Dallas to 67.6 years in ZIP code 75215, which is 67 percent Black.

A Black doctor treating Black patients has numerous advantages. It increases the trust between the long-marginalized Black communities and the healthcare system. It provides a model for young Black patients about a career option that hadn’t been on their radar—which is one of Dr. Dale’s major focuses. Communication style, shared experiences, and community involvement are other ways Black doctors can achieve better outcomes with Black patients.

And now data is proving what many have been anecdotally saying for years. An April 2023 study published in JAMA Network Open found that every 10 percent increase in Black primary care physicians in a county increased life expectancy by one month for Black patients. More Black physicians in a region also reduce the gap between life expectancy for White and Black Americans, which currently sits at six years nationwide. Armed with statistics like this and others, Dr. Dale has made it his mission to do all he can to make medicine more diverse.

Dr. Dale grew up outside Houston, one of four children with immigrant parents who told him medicine might be a good option for his future but didn’t force him into the field. Whatever he chose, he was likely to be a leader, says his older brother Dr. Daniel Okorodudu, who’s also a physician in Dallas and helps run Black Men in White Coats, a brand that shares the name of the documentary. “Even when we were younger, when Dale spoke, we listened,” Daniel says. “He follows through on things.”

Dr. Dale founded Black Men in White Coats in 2013, long before the JAMA study came out. The problem was one he identified throughout his medical education, where he was often one of the very few Black men in his classes or medical education cohorts. “When I was in biology or chemistry or a pre-medical type of course, I would look around the classroom and see that there are not very many people that look like me,” he says.

Racial disparity exists in nearly every professional industry, but becoming a doctor requires an extraordinary ability to navigate several systems before landing a job. First, one must attend a high school that will prepare them for college and stand out enough at that high school to get into premed classes. Next, the student must excel in college, figure out how to navigate and take the MCAT, and pay for and apply to medical schools, which is followed by residency, fellowship, and working in the field. Navigating the path to medicine is exponentially more difficult without the money, connections, and mentors that White children in America are more likely to have.

“Matriculation to medicine is resource-intense,” Dr. Dale says. “How do you provide the resources necessary to compete to that point?”

This is where the documentary and his advocacy strategy come in. Since its release in 2021, the movie has been screened at dozens of medical schools nationwide to promote awareness about the need for more Black doctors. The organization also hosts youth summits, which aim to bring together Black physicians, educators, families, and community leaders to inspire kids to pursue medicine and lay the foundation for mentorship and networking.

But even if Black children believe they can be doctors, that won’t necessarily increase their MCAT scores or give them more time to beef up their resumes before applying to medical school. And Dr. Dale doesn’t want medical schools to let Black students in as charity cases either. A recent Supreme Court ruling will mean that public medical schools can no longer use affirmative action to increase diversity in their student population.

The organization’s tact is to speak with the medical school admissions department to help them redefine what they look for in prospective students. Every school wants the best future physicians they can get in their class, but Dr. Dale wants medical schools to rethink which skills, abilities, and life experiences will make for good physicians. “A lot of these individuals are being overlooked, and they are highly meritorious,” he says.

A patient likely doesn’t care how high their physician’s MCAT score was, but rather how hard they will work to solve their case, Dr. Dale explains. Is the physician resourceful enough to find the answer? Will they stop at nothing to achieve that goal? “That’s not defined by GPA,” he says. “That’s defined by what you have overcome in life to get what you want. Those skills are going to make your healthcare solution better; they are going to make your city better; they are going to make the country better.”

Daniel took notice of what he calls his brother’s superpowers at an early age. “He is very charismatic and has a way of galvanizing people,” says Dale’s brother Daniel. “He could do a lot of evil with his talents, but he truly cares about people.”

Dr. Dale is known both for his rapport with patients and his clinical acumen at UT Southwestern and the North Texas V.A. hospital—he divides his time between the two—and becoming a respected doctor a priority before expanding his influence. “He is a phenomenal physician, and he has this presidential demeanor,” says Dr. Carlos Girod, the associate vice president for Parkland health affairs at UT

Outreach efforts include a podcast and a dozen books.

Dr. Dale Okorodudu is writing a book about why the medical community needs more diversity and its impact on health outcomes. With a population that is only growing more diverse, he wants to ensure that underrepresented populations can be treated by a physician who looks like and has similar life experience as they do. That book will be his 12th. Another work is Black Men in White Coats: 100 Rules for Success!, in which he outlines his lessons learned as well as the eponymous podcast about how to overcome difficult circumstances on the way to being successful. Dr. Dale is a father of three and writes a juvenile fiction series meant to help parents introduce the idea of becoming physicians called Doc 2 Doc “The way Dale views life is not something to hold on to, but to pour into the people around him,” says Dr. Dale’s brother Daniel. “There are not enough hours in the day; I simply do not know how he accomplishes everything.”

Southwestern. Girod trained Dr. Dale as a fellow and says he looks up to him even though he is his senior by several years. “When he speaks, he commands the room with humble confidence.”

Black Men in White Coats has been operating during a time of progress, but the system is still years from true equity. According to the American Association of Medical Colleges, the number of first-year medical Black male students increased by an impressive 20.8 percent in 2021. Black students of both genders comprised 11.3 percent of matriculants, up from 9.5 percent in 2020. In 2022, the first-year Black male demographic increased by another 5 percent in the nation’s medical schools.

The statistics surrounding Black men in medicine are becoming more promising, but difficulties in patient outcomes and trust in the system remain. Dr. Dale faces these challenges every day in his time seeing patients. Black Americans have lived through experimentation on enslaved people, forced sterilization of Black women, and the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study, where hundreds of Black men were denied treatment for decades to allow doctors to track the disease’s progress.

Black maternal mortality studies and others show that Black patients are underrated for the pain they are experiencing and have caused rifts between the Black community and the healthcare system. A 2020 Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that seven in 10 Black Americans say the healthcare system has mistreated them, and 55 percent say they don’t trust it.

Overcoming generations of neglect and mistrust is a challenge Dr. Dale faces every day and one he believes can be improved by diversifying the workforce. He remembers one interaction with a Black patient who needed a procedure that the patient didn’t want to undergo. The patient did not believe the caregivers had his best interest in mind and was sure he was a guinea pig and that the doctors were going to kill him. Dr. Dale took the time to speak with the man, reassuring him that he understood the history and his concerns but that no one there was trying to kill him. “I was able to bridge that gap of misunderstanding based on the years of medical atrocities that have happened in the United States,” he says. “I’m here. I’m your advocate. We’re going to make sure that doesn’t happen.”

Moments like that, Dr. Dale says, demonstrate the power of Black Men in White Coats.

graduated its first class this spring under a new curriculum model that integrates classroom learning with clinical application.

THE TIME IS OFTEN DIVORCED FROM ANY PRACTICAL application or reminders about how the Krebs cycle or embryology works in the human body—information that the future doctors may use daily upon graduation. Even before the pandemic, most medical students didn’t go to class in-person: They watched or listened to lectures at 1.5 speed, taking notes to be memorized later.

Once classes are completed, the students hustle through clinical rotations, working their way quickly through several different departments, where they experience an intense crash course in the workings of that system, then move on to the next.

These methods make up a pedagogy that misses the opportunity to get the most out of the bright minds who chose medicine over other career options because they wanted to connect with patients and help them feel better.

But a movement among medical schools is looking to make education more engaging, relevant, and applicable to the realities of medical practice. North Texas’ Anne Burnett Marion School of Medicine at Texas Christian University was founded on the principals of this curricular model, called a Longitudinal Integrated

Clerkship (LIC). The school’s first class of medical students graduated this spring and are now completing their intern years at residency programs nationwide.

The LIC is a growing curricular model that allows students to follow patients as they move through the health system, integrating classroom learning into a clinical setting. Rather than immersing students into one department for a few weeks during a clinical rotation, then never having them visit that department again, students at the Burnett School of Medicine distribute the same hours throughout the four years of medical school.

Dr. Jo Anna Leuck is an associate dean and professor at TCU who was educated in a traditional model but now teaches in a LIC environment. “I would do pediatrics for six weeks, and then I never did that again,” she says. “I only followed the inpatient, ivory tower academic version of medicine, which is just not how medicine works.”

At the Burnett School of Medicine, students spend a half day each week or every other week in a clinic or hospital, where they balance practical experience with classroom learning. In essence, the school takes the two years of classroom study and the two years of clinical experience in traditional medical education and integrates them, stretching the curriculum over all four years of learning.

TCU students have several 40-week rotations, where they build relationships with the preceptor and patients, following them from the clinic into the hospital and back. A student might start the day in a cardiac anatomy classroom learning environment, then move into the clinical skills class where the curriculum is designed to help them practice a cardiovascular exam. There, they can listen to the valves they read about that morning. Those skills and objectives are communicated to the preceptor, who can reinforce the learning by allowing student to practice on actual patients during their rotation, interweaving the theoretical with the practical.

“That’s how you get to see the different arenas of care, how communication works and doesn’t work,” Leuck says. “It is a richer experience. It’s harder to pull off and uses a ton of resources, but we feel like the juice is worth the squeeze.”

One of the school’s priorities is developing empathetic physicians, and the long-term relationships that students build with patients and professors throughout their studies provide ample opportunity to foster the empathy and bedside manner that helps create quality physicians. “Nothing makes the students’ eyes light up like the fact that we don’t make them sit in a classroom for two years,” Leuck says.

Putting together this type of curriculum and convincing professors and clinicians to do things differently isn’t easy. It requires a 1:1 physician-student ratio with hundreds of physician preceptors; lecture-style classroom learning goes out the window. The school only does interactive application sessions in smaller groups.

But the extra effort is already paying off. “When the students go away on their rotations, we keep getting feedback that there is a real difference, both in their clinical skills and communication and connection skills,” Leuck says.

For decades, medical school has looked something like this: the first two years is a grueling test of students’ ability to memorize massive amounts of biology and chemistry information that most of them may never use again, before quickly forgetting it to make room for what’s on the next exam.

And support for the new program isn’t just qualitative. Research from the National Institutes of Health has shown that LIC students perform as well or better than their traditionally educated peers. They have a more positive and satisfied attitude toward their educational experience and greater fulfillment of their expectation to create meaningful relationships with patients and families during medical school.

This year’s class at TCU sent 52 students to residency programs around the country, including prestigious programs at UT Southwestern, Stanford, Tufts, Vanderbilt, UCLA, Columbia, and more. “It was time to change the model, though others would roll their eyes,” says Founding Dean Dr. Stuart Flynn. “Four years after the student’s first class, nothing has collapsed around us, the model is standing, and we are improving on it.”

When most students apply to medical school, they look at where a school’s graduates are matched for residency. TCU’s medical school, which began with its first class of students in 2019, didn’t have the advantage of a match record or the ability to say, “Look where our graduates have ended up.” The program still attracted applications from across the country.

In the last couple of years, the school averaged around 6,500 applications annually for just 60 spots. Now, between the school’s appearance in the college football national championship (an event that is a boost to all the school’s programs, even medical school) and graduating its first class (one that created a match record) Interim Dean of Admissions, Outreach, and Financial Education Dr. Shawn Skeen says he expects that to increase.

The school’s focus on empathetic scholars is another draw for students. Research says that most medical students enter med school looking to help others, but the grind and curricular rigor of a program can defray that mindset. “The way we plan curriculum and the admissions process includes a strong sense of empathy, as well as how students will maintain that through medical school,” Skeen says.

In the end, a patient is more likely to remember whether the physician listened in a moment of crisis than their doctor's board exam score. The last few years haven’t been the easiest for physicians. Between the pandemic, the politicization of their practice, and growing labor shortages, there are easier ways to make a living and support a family. But Skeen says medical schools don’t see that reflected in future applicants’ interest levels. Every few years, he says, something happens in medicine that everyone thinks will turn young people off from the profession, but it never does.

“The beauty of it is that the minds and

souls who want to do this do it regardless, or sometimes, because of, those things,” Skeen says. “They run toward that hurricane as fast as they can while everybody else is running away.” It is that way of thinking that makes for empathetic scholars, Skeen says, and something the school wants to cultivate and grow during students’ four years in medical school— not quash.

Texas is undergoing a renaissance with healthcare education programs, with medical and osteopathic schools at UT-Rio Grande Valley, the University of Houston, Sam Houston State University, UT-Tyler, and TCU opening or established in recent years. Most new schools incorporate aspects of the LIC model in the new curriculum. As a school founded on these principles, TCU’s medical school is becoming an influencer in the world of LIC schools, presenting at international conferences for their peers.

As more graduates move into residency programs nationwide, the school will have evidence of its successes and opportunities for growth. Dean Flynn is bullish on future feedback. “What is going to happen is that students are going to go into residency programs, and many are going to show that they are the best of breed,” he says. “Within five to six years of leaving TCU, the programs will tell us, ‘Your young people were sustainable.’ It’s not just a makeover.”

Construction is underway on a four-story, 100,000 square-foot medical education building in Fort Worth’s Near Southside neighborhood. The 5.3-acre campus will serve as the academic hub for the school’s 240 medical students and hundreds of faculty members and other staff. Completion of the building is planned for 2024. The neighborhood is already home to numerous other hospitals and healthcare facilities.

In origami, one takes a simple, square sheet of paper and transforms it – through patience and practice – into something beautiful and intricate.

For 40 years, we have been working to help our clients master the intricacies of workforce management with a focus on enhancing operating margins and financial performance, increasing workforce flexibility, and improving patient experiences.

Learn more about the strategies, technology, and talent we provide to drive savings and improve operations to achieve your financial and care goals.

INDUSTRY LEADERS DISCUSS WHAT’S NOW AND WHAT’S NEXT IN HEALTHCARE DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION.

story by WILL MADDOXPATIENT PREFERENCES, design, and technological advances are critical considerations as hospital operators continue to seek the most innovative ways to care for their patients. Hospital leaders, designers, and construction professionals contemplate everything from patient flow and electronic health records, to materials and hospital security to determine what’s next. Hospital operators and designers are in a uniquely challenging position. They work in an industry that is heavily regulated and notably not nimble, but innovation and societal issues constantly change what is feasible and desirable. The safety of patients and staff continues to be another issue that those who design and operate hospitals must consider, especially today. The future is incredibly bright in an industry where there are often more questions than answers. D CEO Healthcare recently assembled a team of experts to share insights about solutions to these challenges.

PAINT A PICTURE FOR US ABOUT SOME OF THE MOST SIGNIFICANT CHANGES YOU SEE ON THE HORIZON IN THE NEXT 25 TO 30 YEARS.

ASHLEY DIAS: I like to look out 25–30 years because that is when we’ll see some real paradigm shifts and generational change, which is exciting to me. In that amount of time, we are going to see significant technological advancement, but looking back in time as technology has evolved, what we have learned is that all the advancement of technology offloads from human tasks, allowing us to elevate our contribution. What that means in general for healthcare is that we’re going to be able to shift our focus on discovery and diagnosis toward care management in the relationship between

the patient and the provider. So, what does that mean for space? We are starting to see immersive connectivity, and digital augmentation, for instance, is on the horizon. The predictability of AI is going to change spaces, but let’s talk specifically about an exam room or patient rooms— what are those going to look like? They are now focused on examination, discovery of analytics, and understanding diagnosis. They will be able to shift in the future to care management, treatment plan success, and the relationship. These spaces will be more comfortable, more focused on counseling and collaboration between the patient and the provider. I’m excited about these spaces because I think they will be more comfortable. Other things that we’re going to see are changes to our logistics by way of robotics in our supply chain management. In 25 years, this is going to be normal. In addition to working in person, doctors will have offices in the metaverse. I like to use this example: In 30 years, we’re going to be designing departments that we’ve never

designed before. I’ll use this made-up example to make the point: an anomathy. What’s an anomathy? It will be part clinical lab, part pharmacy, part biomedical engineering, and a nanotechnology makerspace. A combination of all those things will be a normal department 30 years from now. It is fun to think that far because that is where we will see some exciting change, but the theme is that we are going to get to be more human, despite all the technology.”

HOW ARE YOU THINKING ABOUT BALANCING WELCOMING DESIGN AND HOSPITABLE SPACE WITH THE GROWING NEED FOR GREATER SECURITY IN A HOSPITAL?

JASON SCHROER: “One of our main responsibilities as architects is safety. It’s just part of what we are obligated to do in hospitals. So, we’ve always had this mindset of safety and infection control, things that are typical to what you think about in hospitals. Plus, things like proper exiting, and

how you manage fires if they pop up. All those things are embedded in our learning, and in our DNA, and what we’re obligated to do by code. When you begin to think about what happened during COVID and the kind of additional threat of gun violence and other things that penetrate a lot of our buildings, we try to take some of the ideas that we already have in terms of containment. When you think about the analogy of a submarine, they’re designed in ways in which if they get punctured, they can seal themselves off and there’s only water in certain compartments. When you think about safety, it’s very similar in that regard in terms of how we design submarines. We start thinking about how we integrate those systems and exit doors, cross corridor doors. Where can we begin to think about containment? If there’s an incident in the emergency department, we begin to look at containing that incident to that location. There are ways in which we can build our systems where those doors will lock so you can contain and separate. Now, where the idea of separation

ASHLEY DIAS, Perkins & Will

“We’re going to be able to shift our focus on discovery and diagnosis toward care management in the relationship between the patient and the provider.”

At Children’s HealthSM our individualized approach to pediatric health care allows us to treat each child with the attention and care they deserve. See why we’ve been named the #1 children’s hospital in North Texas at childrens.com.

incredible. together.

and hospitality interface, that’s a little more difficult to describe without pictures. But there are opportunities for us to try to find that balance between protection separation and still provide a hospitable experience. We are seeing in our emergency departments we’re putting that initial checkin behind glass, but there’s ways in which we can do it where it still makes it seem as though that’s inviting and open. With a lot of our systems in hospitals, how do you put armed guards or police in those locations in a way that keeps it from being intimidating or creating anxiety for people.”

MUCH OF YOUR WORK HAS FOCUSED ON A SINGLE HOSPITAL THAT HAS BEEN REMODELED FOUR TO FIVE TIMES IN YOUR 20 YEARS THERE. TALK ABOUT THE FACTORS THAT LEAD TO THESE CHANGES AND A COUPLE OF EXAMPLES OF WHAT CHANGES WERE MADE AND WHY.

DARRON BLACK: “When you think about remodeling hospitals, there are several factors, including changes in laws, changes in staff, and changes in technology, but I think the first thing that comes to mind is what groups of physicians is the administration hiring? If they’re going to hire a new group of endocrinology doctors that are going to bring more procedures in, then we’re going to build more endocrinology suites. Those kinds of changes back and forth are why we have remodeled certain spaces four or five

different times over the last 20 years. When you have a new facility, it is the brand-new shiny object, so the physician’s groups are wanting to book all those operating rooms, so now you’ve got a bottleneck in the sterile processing department trying to process all your instruments. Fortunately, we plan for that, so we build space for expanding those services.”

YOUR HOSPITAL WAS BUILT IN A UNIQUE WAY. CAN YOU EXPLAIN THIS AND TALK A BIT ABOUT THE ADVANTAGES OF GOING IN THAT DIRECTION?

KENNETH ROSE: “Our hospital was built in a unique way through prefabrication. As we were designing this hospital, we wanted it to be consumercentric, and we wanted to be a hospital of the future. One of the things that The Beck Group told us was we should consider prefabrication as a part of our building process. At times, it can help with cost, but it always helps with efficiency. It means that parts of our building—and for us

mainly it was patient room bathrooms—were built in an off-site warehouse put together completely to be almost functional. They just needed to be installed. It was all put together in one place, so it helps with labor. Much of our hospital was built in the middle of summer in Texas. If you were to do a construction job outside, would you rather do your job in construction or in an air-conditioned warehouse? When you’re trying to attract labor in the different trades to build these bathrooms, it’s an easy way to convince people that your project is a better project to work on. With all of our growth, these tradesmen are hard to find and are hard to book. Bathrooms and head walls were designed in a warehouse in Grapevine and then they were boat wrapped and put on 18-wheelers. They drove onto our property, were taken off the trucks, and craned up to the second floor where they were installed. The bathrooms were slid in, fit perfectly, and installed quickly. It kept us on track with our construction project. When we think about the future of

healthcare, we need to look at other industries, how we consume things, how we receive things, and how we order things. Healthcare has got to get out of its own way and look at other industries that have figured out how to attract consumers and keep consumers.”

SHORTAGES HAVE PLAGUED EVERY ASPECT OF THE HEALTHCARE INDUSTRY, AND IT ISN’T A PROBLEM THAT’S GOING AWAY ANY TIME SOON. HOW ARE PROVIDERS AND DESIGN PROFESSIONALS THINKING ABOUT ADDRESSING THOSE ISSUES, AND HOW DOES IT IMPACT DESIGN?

SCHROER: “When you think about hospital design— specifically patient units, nurse stations, and things like that—there are standard nurse-to-patient ratios that we’ve tried to plan around. When you think about where people must sit, their visibility, and those ratios, it impacts how you design those units.

JASON SCHROER, HKS

“There are opportunities for us to try to find that balance between protection separation and still provide a hospitable experience.”

You can count on us.

With healthcare as the backbone of our construction success since 1969, we draw upon the experience, knowledge, and talent of generations.

Ranked #1

GENERAL CONTRACTOR FOR HEALTHCARE CONSTRUCTION BY MODERN HEALTHCARE

brasfieldgorrie.com

We are finding that we may have to start to rethink some of those ratios, and that will impact the design of our units. We even go into the science of walking distances and other things that we can measure based on testing out different layouts on floor plans. We can go into the field and measure if our designs supported giving nurses more opportunity to be bedside as opposed to walking and looking for meds, looking for supplies, and things like that. The other thing that we’re seeing, too, is integrating innovation and technology. Robotics are big in terms of trying to figure out what are certain tasks that can be mitigated, which is reinforced by shortages. We’re seeing that the caregiver average age is much lower than normal, and we have seen some innovative ideas around some systems. Some are convincing senior caregivers and saying they still want them on the team, but they are going to put the nurse in a command center to be available to all of our other nurses and caregivers in the system. Some systems have created a command center of more seasoned nurses as a safety net for their nurses within their system. It creates great mentorship opportunities.”

ROSE: “Healthcare is moving into an age where we have to be more consumer-centric. With our space, we want to make sure we have an environment where people can heal. Part of that healing is in family and connections, so you need rooms that can hold a spouse and maybe kids and parents where they can heal with the community, not just individually in small rooms. We’re done with double occupancy in healthcare. The other thing with space is natural light. Something that a lot of hospitals have done historically is what we call out-boarding of bathrooms, which moves the bathroom toward the exterior wall of the patient room, and it limits the amount of window space that you can have. With our hospital, we decided to inboard our bathrooms, which gave us larger windows and more natural light. It’s a basic thing, but it helps a patient when they’re there. We want it to feel more like home or a hotel.”

HOW HAVE SUPPLY CHAIN ISSUES AND INCREASING LEAD TIMES IMPACTED HOSPITAL CONSTRUCTION?

BLACK: “Supply chain challenges are extending the overall durations and the final end dates of everything. With a lead time of 30 or 50 weeks out, we bring those to the client and say, ‘What is more important to you? Is it money, or is it quality, or is the time?’ The other thing we think about in our industry is that we like just-in-time delivery. A lot of our job sites don’t have any storage, so we want to order our products and have them arrive just in time so that they can go into the building and be installed. Nowadays, you don’t have that luxury, and you may or may not know, so if you have space on site, then you can get storage containers to store stuff and get it in early. If not, we need to start talking about upfront warehouse space, getting those products in, and storing them so that we can have them when we need them so that it’s not impacting the overall duration.”

HEALTHCARE PROVIDERS ARE INCREASINGLY FOCUSED ON CONTINUITY OF CARE AND MAKING SURE PATIENTS STAY CONNECTED TO THE HEALTHCARE SYSTEM. HOW DOES THAT IMPACT DESIGN AND THE SPACE WHERE PATIENTS EXIST?

DIAS: “With the digital connection that we’re starting to get to our systems, it’s still figuring itself out. But hopefully, with digital connectivity to all the systems and opportunities, that will clarify as time marches on for us. What that means for design is that as it becomes clearer and we’re all educated more about where to go, we can spend less time as designers using architecture to clarify the healthcare continuum, and we can spend more time in the delightfulness of spaces. Daylight, biophilia, and art all deserve a great amount of design energy, and so the more that we can clarify the continuum, the more we can design delightful spaces. We’re not there yet, but I think that is the opportunity.”

AS CEO, YOU ARE CONCERNED WITH IMPROVING OUTCOMES VIA DESIGN. AS THE LEADER OF A RELATIVELY NEW FACILITY, HOW DID THE HOSPITAL INCORPORATE DESIGN ELEMENTS TO PROMOTE HEALING?

THE HOSPITAL OF TOMORROW IS OFTEN LITERALLY TOMORROW.

“Healthcare is moving into an age where we have to be more consumer-centric. We want to make sure we have an environment where people can heal.”