DC MOORE GALLERY

Yvonne Ja cquett e i s best known for dazzling paintings of views observed from the top floors of skyscrapers and the far higher vantage points of airplanes and helicopters. That view was the stuff of dreams long before the Roman poet Ovid’s account of the story of Icarus but not accessible to mortals until the beginning of the last century if we exclude the Montgolfier brothers’ hot air balloons from the end of the 18th century. It was a perspective that remained not readily available to the public before the 1950s, and when Jacquette took the plane ride that changed her life and practice (at around the time of the Apollo 11 moon landing), flying was still thrilling.

While the aerial vistas begun approximately a decade later became her signature images particularly the nocturnes that captured the transformation of drab metropolitan streets and buildings into wonderlands of sparkling light and color when night fell she did not exclude rural scenes such as fields, forests, mountains, and water from her highflying repertoire. But, before looking down, Jacquette looked in other directions, focusing primarily on what was often just overhead or close by, scrutinizing commonplace objects and spaces usually not accorded a starring role in paintings, especially those on a grander scale. She and her cohort of like-minded artists, often women, saw significant beauty in the quotidian, engaged by what shaped their immediate reality. They believed that domestic objects could be the subject of art, could become art, beliefs supported by feminist theories that would eventually upend the existing paternalistic canon.

The exhibition , Yvonne Jacquette, Looking Up/Down/Inside Ou t, presents more than three dozen paintings and works on paper from 1962 – 197 6. Seldom shown together, these earlier endeavors seem very different from her acclaimed,

beloved panoramas. Nonetheless, the themes and formal strategies that have become her trademark are already present: for instance, the distinctive, even idiosyncratic point of view; the absence of human figures, although their presence is always implied; the happy cohabitation of the abstract and the representational; and the precision of architectural components softened by the expressiveness of the brushwork.

Jacquette was born in 1934 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and raised in Stamford, Connecticut. She attended the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) and, just shy of graduation, left for New York to try her luck, like so many before her. That was in 1955 . She has lived in Manhattan ever since, her luck, sustained by her talent, holding steady for nearly seven decades. She fell in with a group of artists who were Realists. Many of them were women, some were feminists or proto-feminists in resistance against or reaction to Abstract Expressionism. Jacquette also met filmmakers and photographers and, in 1964 , married one of them, Rudy Burckhardt (191 4 – 1999 ) , who was born in Switzerland but had become a passionate New Yorker. Their circle of friends included Edwin Denby, Willem de Kooning, Fairfield Porter, Robert Mangold, Sylvia Plimack Mangold, Mimi Gross, Red Grooms, Alex Katz, Nell Blaine, and Jane Freilicher, among many others, almost all representational artists, their practice at odds with Minimalism, Conceptualism, and Performance Art, then ascendant. Burckhardt, deeply entrenched in the downtown art world and a mentor to many, influenced the direction her work took in her formative years. His odd camera angles and points of

WINDOW ON FIRE ESCAP E , Spring 1965

WINDOW ON FIRE ESCAP E , Spring 1965

view and his tremendous love of New York its physical structures and propulsive rhythms, its variabilities inspired and reinforced Jacquette’s own embrace of the city and her paeans to it.

While many Photorealists or Super Realists of the period, with whom she was grouped for a time, aspired to the (putative) objectivity of photography, Jacquette, with perhaps a few exceptions, did not suppress the traces of her hand in her work. She never thought that the painterly should be excluded, asserting that the abstract and representational “exist perfectly, happily together. It’s not that you have to have one or the other,” she said, in a 2014– 15 series of conversations with her son Tom Burckhardt, also a painter of note 1

One striking violet gray painting, Window Shadow (c. 1965) [ p 9 ] , pictures the subject as a reflection on the floor. It is tall and dimly lit, its multi-paned frame silhouetted against the shade drawn across it. The window, an enduring motif in Jacquette’s practice, occupies nearly the entire surface of the painting, and seems to lean back into it, drawing our gaze upward. But the rendering seems askew, as Jacquette introduces, without fanfare, more than one perspectival resolution into the painting. It is a frequent ploy, one with links to pre-Renaissance paintings, Cubism, and the naïfs. She also uses “color to shift the normal reading” of a work, playing off positive and negative spaces and the spaces in between, she said, in a 1989 interview with Barbara Shikler for the Archives of American Art

Oral History Project 2

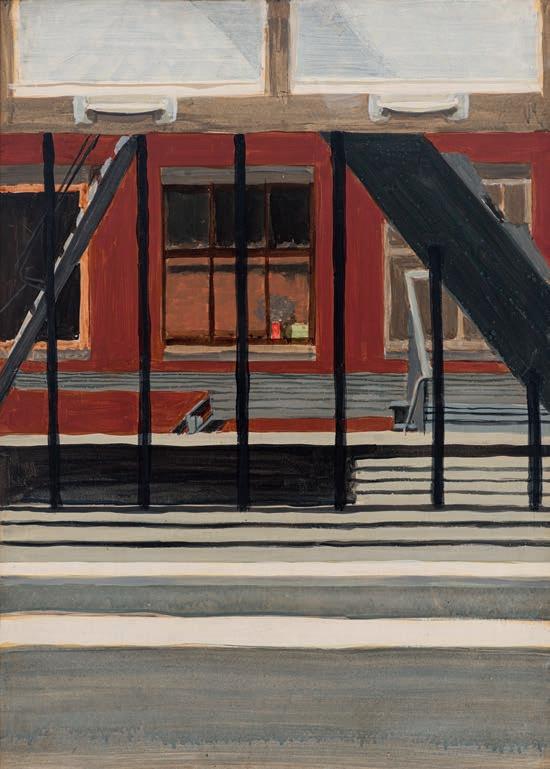

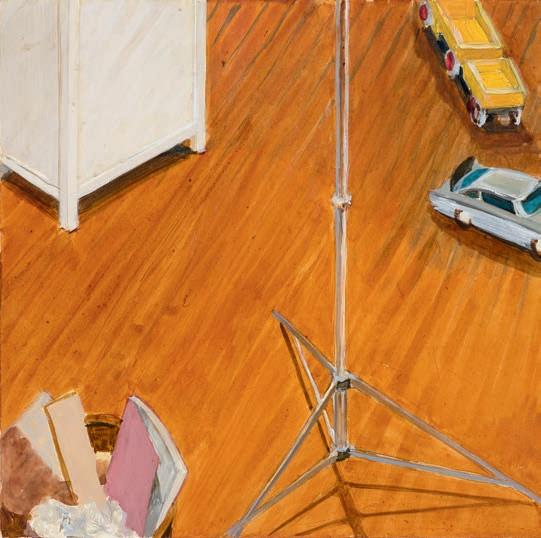

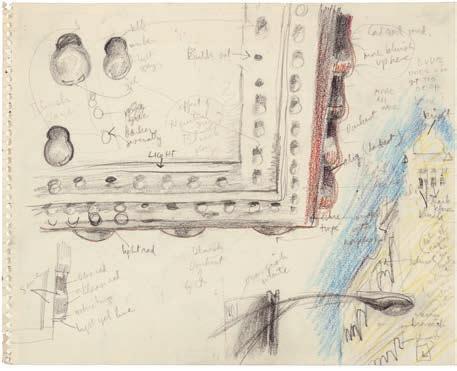

STUDY FOR THE JAMES BOND CAR PAINTIN G , 1967

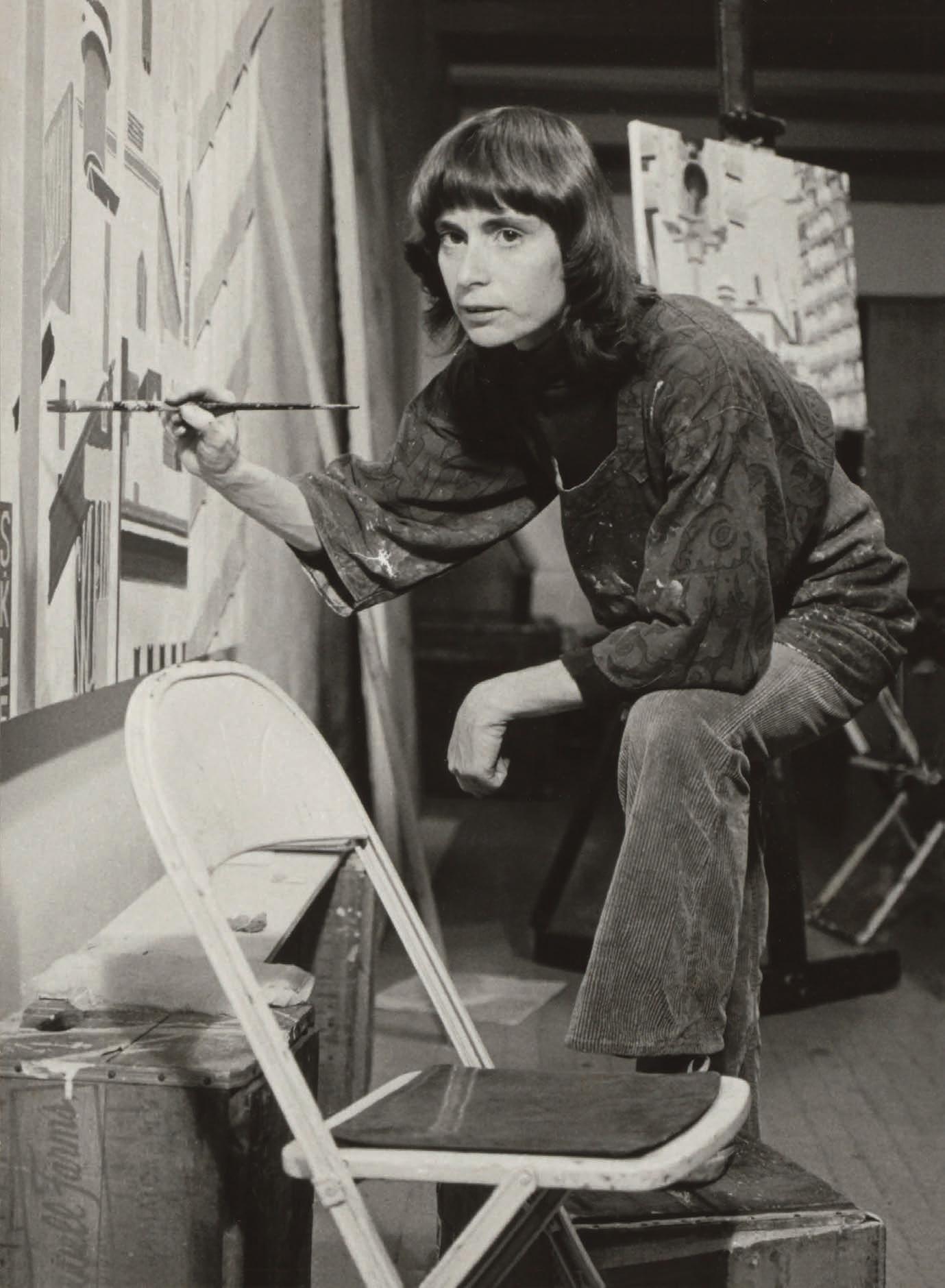

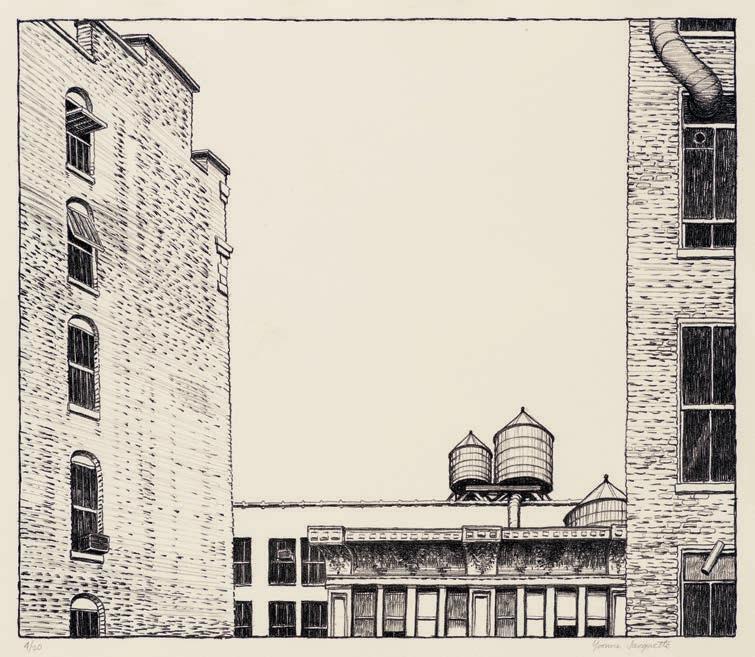

The point of view of other window paintings presented here peer into the picture plane, defining the canvas as an entry into illusionary space, with a clearly legible foreground, middle ground, and background. Colorful plants and flowers, potted and in vases, and floral-patterned curtains splashed with a gorgeous red add a cheerful vibrancy to a pair of paintings she made in Maine, Maine View with Curtains (1964 ) [ p 5 ] and Still Life with Plants (1962 ) [ p 2 ] , where Jacquette and Burckhardt had bought a house and spent summers during the thirty-five plus years of their marriage . Another painting, Window on Fire Escape (1965 ) [ p 4 ] , composed of forceful horizontal and diagonal lines, is decidedly, delightfully urban (what could be more typical of midcentury New York than an apartment with a fire escape?) .

Soon, Jacquette was painting images of doors, walls, floors, and ceilings, with a country wall thrown in, its piled-up stones an adamant backdrop to a quartet of intrepid black-eyed Susans tucked into the foreground: human constructs versus nature’s creations. She zooms in on places of architectural junction, cropping them so the familiar becomes far less so. Under-Space (1966 ) [ p 7 ] is an elegantly spare, gray-scaled painting of modest dimensions and precisionist rigor that is difficult to parse at first glance. It is eventually revealed as the legs of a chair, although it seems to float in an undifferentiated space that, once again, is curiously off-kilter. The shadow of its underside cast onto what is presumably the floor (looking up at the chair) only adds to the ambiguity, its placement destabilizing, improbable. But, if so, the loss of verisimili tude

is the painting’s gain, an example of the analysis of the “space between objects” that the art historian Linda Nochlin in 1974 said characterized Jacquette’s paintings . 3 For the artist, the pictorial tension between space and object is what makes art interesting.

She identified it as her son’s highchair in that same series of conversations with him. Looking at “just its legs resting on the floor and the tubular silver crossbar and the shadow,” it looked very minimalist, which made her want to paint it. As an artist, a woman who was the mother of a young child, she had limited time to fully devote to her work. She had to learn to use her time well, to seize what was at hand, engrossed by what she might have previously disregarded, such as a highchair, which she stripped down to its formal elements, narrative and sentimentality eliminated.

The fluorescent light in her studio at the time provoked a similar response. The painting Study for Fluorescent Light ( 1969 ) [ p 14 ] , although seen from below up, stretched overhead across the ceiling horizontally, might also be read vertically, as “straight up,” as she described it, playing again with a spatial orientation that urges a reconsideration of both the space and the light fixture, her attentiveness shifting the emphasis from “light fixture” to more formal elements. She also includes indicators here to position us the upper edge of a door, the conduits for electric wires, the brighter banding that marks the division between the ceiling and wall the detailing adding a sense of depth and location that is more definitive than in Under-Space

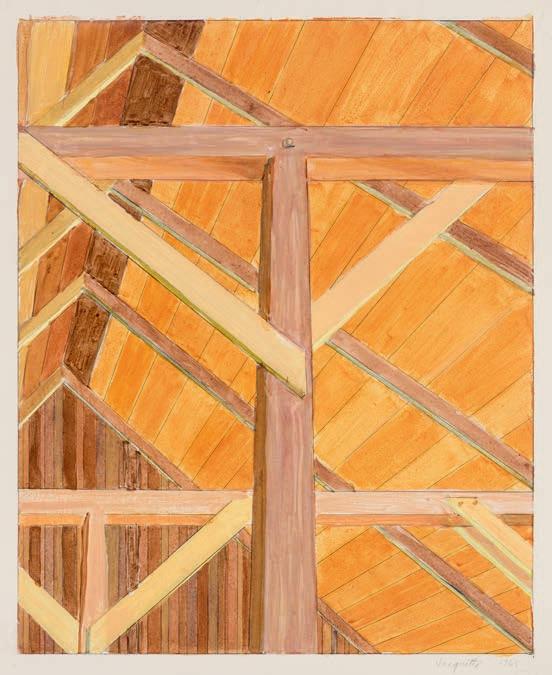

BARN CEILIN G , 1968

BARN CEILIN G , 1968

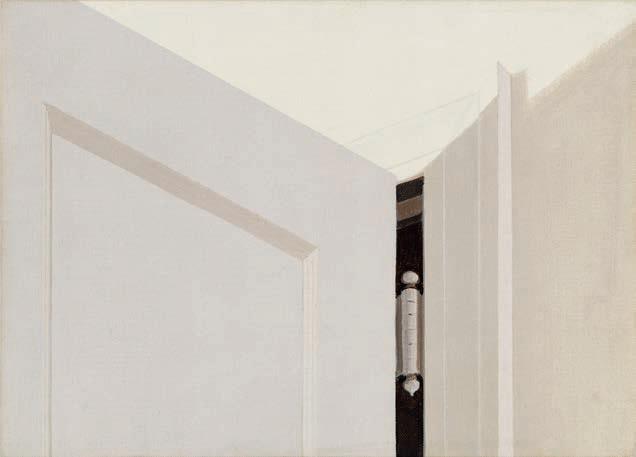

OPEN DOOR WITH HINGE (SMALL VERSION) , 1967

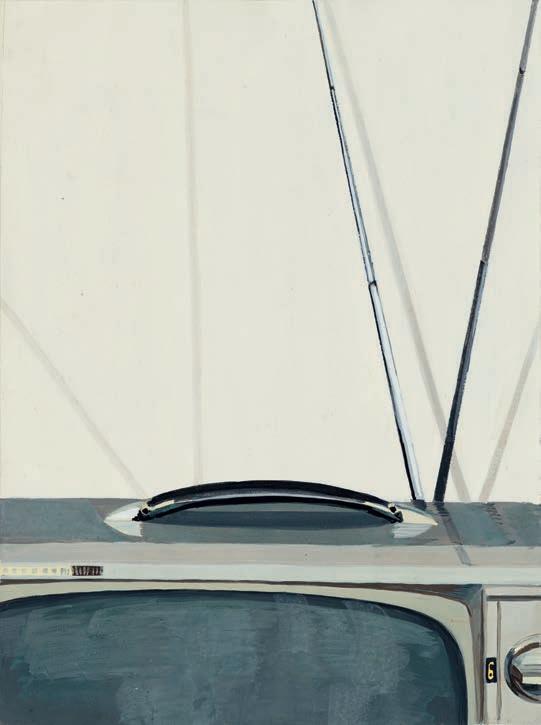

One of the largest paintings here is Barn Ceiling (1969 ) [ p. 13 ] , just under seven feet high and around five feet wide, accompanied by a smaller version in watercolor dated one year earlier. Jacquette is not afraid to scale up (or down), her dimensions ambitious almost from the beginning, encouraged by Alex Katz to go big and to explore the same subject in various scales. It is a partial view of the barn’s peaked ceiling, the planks so warm and glowing that they could be used to make a Stradivarius. The image is that of a post-and-lintel system triangulated to support the pitched roof, the barn a subject that is, once again, conveniently at hand, since it served as her summer studio. It is carefully observed, but full of her usual pictorial feints that include seesawing between the realistic and the geometric, an inconsistent perspectival system that is subtly disruptive, cueing our perceptual alertness, and a color scheme that nods to actuality but defers to aesthetic preference.

Smaller Tin Ceiling [ p. 19 ] , Detail of Ceiling [ p. 18 ] , and Open Door, Tin Ceiling [p.15] ( all 1969 ) also focus on ceilings, two of the works incorporating doors, which is another motif, as noted, that appears throughout this selection. Open Door, Tin Ceiling is close in size to Barn Ceiling , and it highlights the stamped tin ceilings found in abandoned industrial buildings and former tenements that artists used for studios and lofts, installed as a cheap way to emulate the costly plasterwork of the residences of the wealthy. She said to her son, referring to these paintings, that on a bright day, light found its way inside their place and illuminated the tin ceiling. Because there weren’t many windows, she would also have a light turned on and she noticed how the artificial and natural light interacted,

how they illuminated the pattern of the tiles. She found the play of light so intriguing that she painted the ceiling and, noticing a door that was half open, she put it in too. It appears to be a white painting at first, crossed by a diagonal (the crown molding), full of light and very serene, a domestic space, formalized, objectified, with a whisper of something else in its stillness and silence, its upward tilt. That tilt made me think of the majestic paintings in the domes of Baroque cathedrals, to be looked at di sotto i n su (from below up), here minus their grandeur, but equally meaningful in its mundanity, if not more so. And, looking closer, the painting is not monochrome at all but full of color: pale turquoise, creamy yellow, delicate rose, delicate gray, warmed, cooled. The door, lightly blue, barely a color, is beautiful. The design of the same tiles etched in a luminous blue in Detail of Ceiling , a much smaller work, has its own exquisite charm. As a painting of a geometric pattern that is itself a geometric pattern, it is inextricably abstract and representational, Jacquette restating that a work can be both.

Among the door paintings, one of the standouts is a little canvas board that is labeled Open Door with Hinge Study ( 1967 ) [ p. 14 ] . It is a study of diagonal lines and planes, light and shadow, the composition consisting of the point of convergence between a door and wall, the margin, the negative space between them, painted black. Allotted pride of place in the margin is the humble (but essential) hinge, its objecthood and critical role acknowledged, looking like a kind of talisman or just a hinge. Except for that black strip, the rest of the painting is in quiet, modulated shades of milk and coffee, simple and sophisticated.

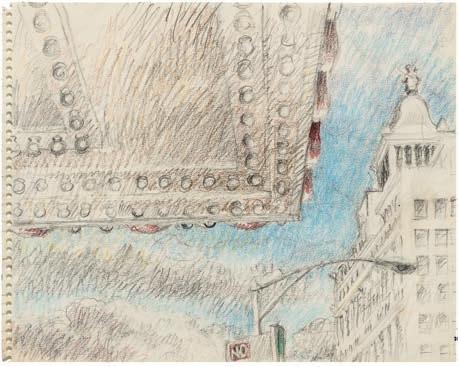

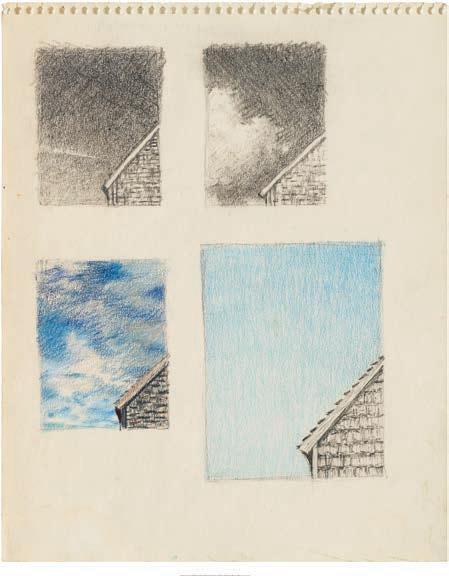

Jumping forward to 1972 , the underside of movie marquees depicted at different times of the day became a new subject. There are several studies recording her various

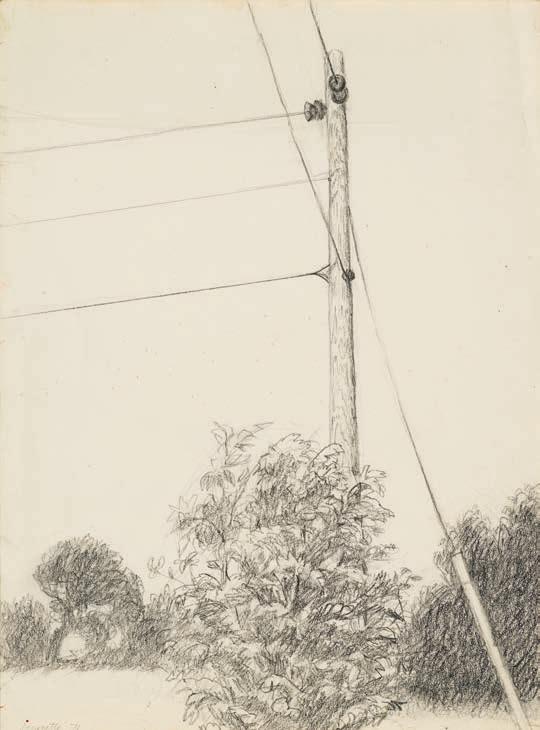

adjustments, such as the placement of the marquee, its dimensions and shape, the intensity of the colors, and, of particular interest, the degree of sky to be glimpsed. The move outside is a preamble to her aerial paintings, and of great significance, as we know in hindsight. Jacquette has freed her gaze from the confines of interiors and of house and home (children do grow older), an act that in some ways summons that of Henrik Ibsen’s Nora leaving her dollhouse, stepping outside into the world.

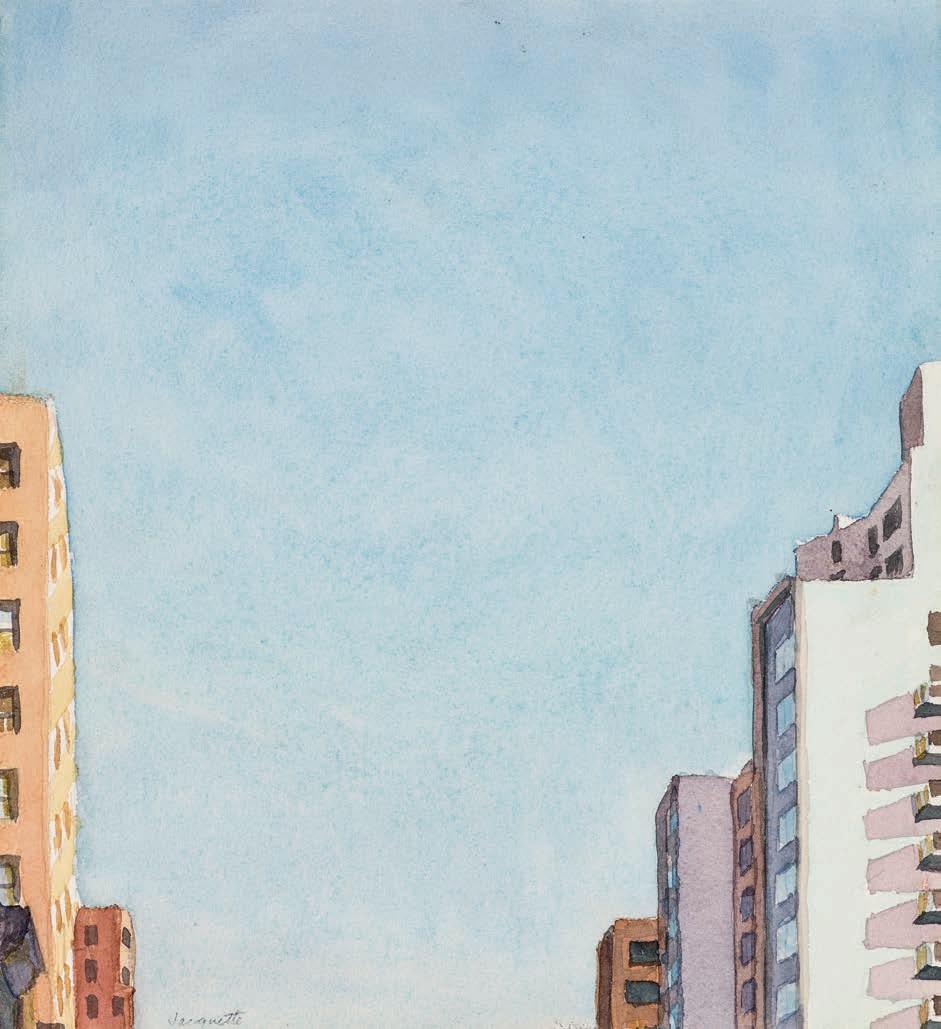

Movie Marque e II (Afternoon ) ( 1972 ) [ p. 21 ] , the finished red, white, and blue painting, is a bold, perfectly poised composition, the cantilevered marquee of the title edged by a spotless blue sky that seems full of promise, the marquee steadying the eye, the sky inviting the gaze to soar. It’s as if she had juxtaposed two realms for dreaming: one fictive, cinematic, the other a gift from nature and both are options. The sky, pillowed with clouds, is also the protago nist of A Quick Look at the Weather ( 1972 ) [ p. 23 ] and Looking Up Study ( 1972 ) and Looking Up II ( 1973 ) [ p. 24 ] The latter, a work on paper as well as one on mat board in which the large building extended across the lower quadrant is merely a support, the sky is the hero, the eye rushing towards it.

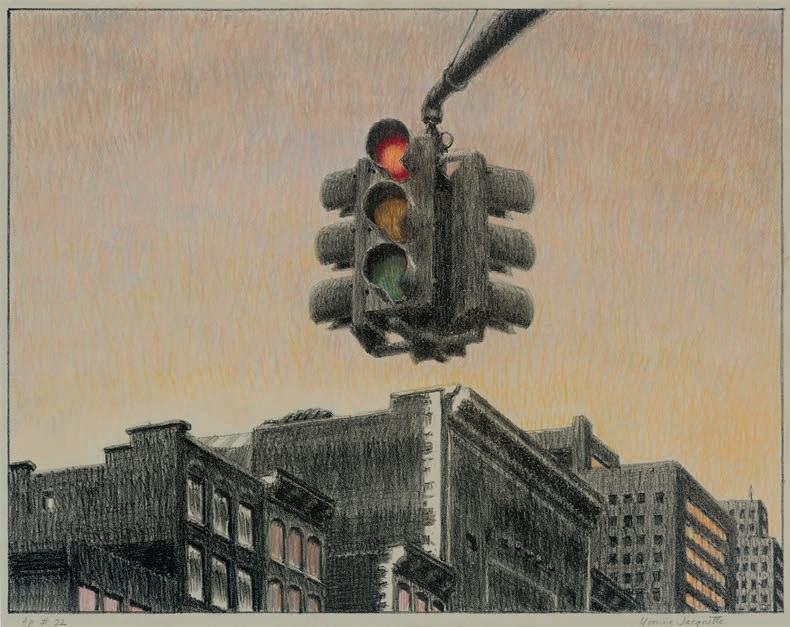

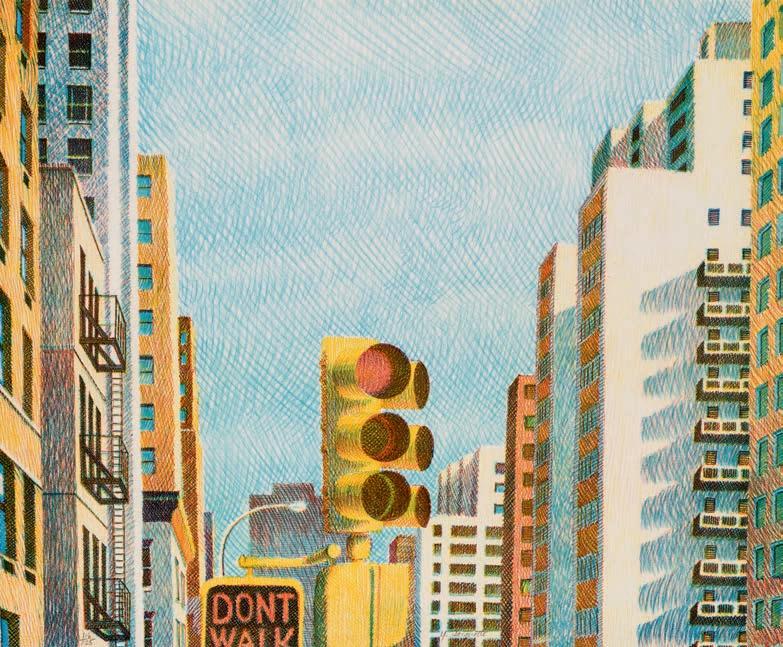

One of the (voyeuristic) pleasures of looking at preparatory drawings is that it permits us to follow the artist at work, comparing the final painting with the studies. The glimpse of the process gives us insight into how the work evolved into its final version and the sketches in pencil and pastel, always Jacquette’s first steps in making a painting, are beguilingly immediate. One example are the painting and prints of stoplights anointing the commonplace mechanism with an unexpected magisterial regality. Another is a lithograph of a building façade; if you look closely, you see that she has gone back into it, adding the reflection (reflections fascinate her) of the sky in the windows by hand.

Sunline is a video that Jacquette made around 1974, with assistance from her husband, the music composed by her stepson, Jacob Burckhardt, also a gifted filmmaker. In it, a shadow crosses the face of an apartment building in a jerky, frame by frame sequence in time to the metronomic, and to me comic, kerplunk of a soundtrack that seems to be pulling the (recalcitrant) darkness across the screen, urged on by an insistent beat that makes me smile. And although only six minutes long, it feels epic, Aristotelian, as day becomes night. Then, the camera shifts, the scene changes, light and shadow plays across an unkempt swatch of grass before it moves again across the façade of a building, a different one.

It could be a manifesto of sorts, reminding us, without fuss, that to still the passage of time is Jacquette’s ultimate subject, and that art can put on pause for an unspecified period of that otherwise unstoppable passage. Gathering and translating the ephemerality of what she has seen into a semblance of permanence, she gilds all that with her singular imagination and consistent intensity of gaze, telling us it never hurts to look (up, down, around), it never hurts to push against boundaries, and it never hurts to dream.

Lil ly We i is a New Yor k based independent curato r, critic, art write r, and journalist whose area of interest is global contemporary art

1 Personal interview with Yvonne Jacquette conducted by Tom Burckhardt. December 28 , 2014 , January 19, 2015 , February 7, 2015 , March 29, 2015.

2 Interview with Yvonne Jacquette by Barbara Shikler for the Archives of American Art Oral History Project, June 6, 1989.

1 Personal interview with Yvonne Jacquette conducted by Tom Burckhardt. December 28 , 2014 , January 19, 2015 , February 7, 2015 , March 29, 2015.

2 Interview with Yvonne Jacquette by Barbara Shikler for the Archives of American Art Oral History Project, June 6, 1989.

Yvonne Jacquette ( b 1934) is an American artist well known for her aerial views of cities and landscapes. She grew up in Stamford, Connecticut, and studied at the Rhode Island School of Design from 1952– 55, leaving after three years to move to New York City. There, she created her own graduate program through visiting galleries and immersing herself in a milieu of other artists, poets, writers, and filmmakers. During this period, she befriended several artists who would also go on to have acclaimed careers, including Rudy Burckhardt, whom she married in 1964, Mimi Gross, Red Grooms, Sylvia Mangold, Alex Katz, Lois Dodd, and Rackstraw Downes.

In the early 1960 s, Jacquette started using her surroundings as subject matter, observing her immediate reality from unusual points of view: looking through the windows of the flower district near her apartment on West 29 th Street, down at her son’s toys on the floor, or up at the light reflected on the tin ceiling while practicing yoga on the floor. These cinematic glimpses of daily life would later translate into her extreme long-views and aerial perspectives, offering alternative visions of reality through direct observation.

In the summer of 1964, Jacquette and Burckhardt rented a house in Lincolnville, Maine with Edwin Denby, Mimi Gross and Red Grooms, near Alex and Ada Katz. In this collaborative, familial environment, Jacquette took the opportunity to experiment with plein-air painting. After she and Burckhardt purchased a house in the nearby town of Searsmont in 1965, she began depicting cropped and angled views of barn interiors and exteriors, windows, and skies.

Her 1967 work, The James Bond Car Painting was included in the group exhibition, Realism No w, at Vassar College Art Gallery in 1968 , marking her first recognition as part of the New Realist movement. In the catalogue essay for the exhibition, Linda Nochlin formulates New Realism as characterized by largeness of scale, a field like flatness, a concern with meas-

urement, and the use of photographic techniques such as crop ping, close-ups and disjunction of scale. Nochlin argues that “not since the Impressionists, has there been a group so concerned with the problems of vision and their solution in terms of pictorial notation and construction.”

In addition to these characteristics, Jacquette took interest in the painterly qualities of light and the motion implicit in visible brushstrokes. In her later aerial and nocturne paintings, Jacquette embraced the atmospheric qualities of darkness and neon lights, the varied, tapestry-like textures of fields seen from above, and the energetic, organic patterns found in urban landscapes. Her recent views of cities document the rapidly changing built environment, leaning further into memory and fantasy, embracing composite views, while remaining rooted in careful observation

In 2008, the Museum of the City of New York organized Under New York Skies: Nocturnes by Yvonne Jacquette. A comprehensive retrospective, Aerial Muse: The Art of Yvonne Jacquette, originated at the Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford University, CA in 2002 and traveled to Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, ME; Utah Museum of Fine Arts, Salt Lake City; and the Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, NY.

Recently, Jacquette’s work was included in the exhibitions At First Light: Two Centuries of Art in Maine (2022) at the Bowdoin Museum of Art, ME , and Slab City Rendezvous (2018–19) at the Farnsworth Art Museum, ME . In 2010, The Center for Maine Contemporary Art organized the exhibition Yvonne Jacquette Aerials: Paintings, Prints, Pastels.

Jacquette’s work is included in the collections of over forty museums, including the Brooklyn Museum , NY; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington , DC ; The Metro politan Museum of Art, NY; The Museum of Modern Art, NY; Philadelphia Museum of Art, PA; and Whitney Museum of American Art, NY.

Lookin g: Up / Down / Inside /Ou t, 196 2 – 19 76

DC Moore Galler y, Ma y 4 – June 10, 2023

© D C Moore Gallery, 2023

From There to Here: Up, Dow n , Around © Lilly We i, 2023

isbn : 978 -1-736772 3-1-7

design : Joseph Guglietti

printing : Brilliant

photograph y : © Steven Bates

p 4 : Window on Fire Escape, Collection of Saskia Grooms

p 12 : Barn Ceiling, Collection of Scott Brown

p 14 : Open Door with Hinge Study, Collection of Rackstraw Downes Study for Fluorescent Light, Collection of Tom Burckhardt & Kathy Butterly

p 17 : Rock Wall, Collection of Jacob Burckhardt

p 21 : Movie Marquee II (Afternoon ), Collection of New York Historical Society, Promised gift of Elie and Sarah Hirschfeld, Scenes of New York City, i l 2 021 51 106

p 24 : Looking Up Study, Collection of Mira Schor

p 31: Traffic Light, Private Collection

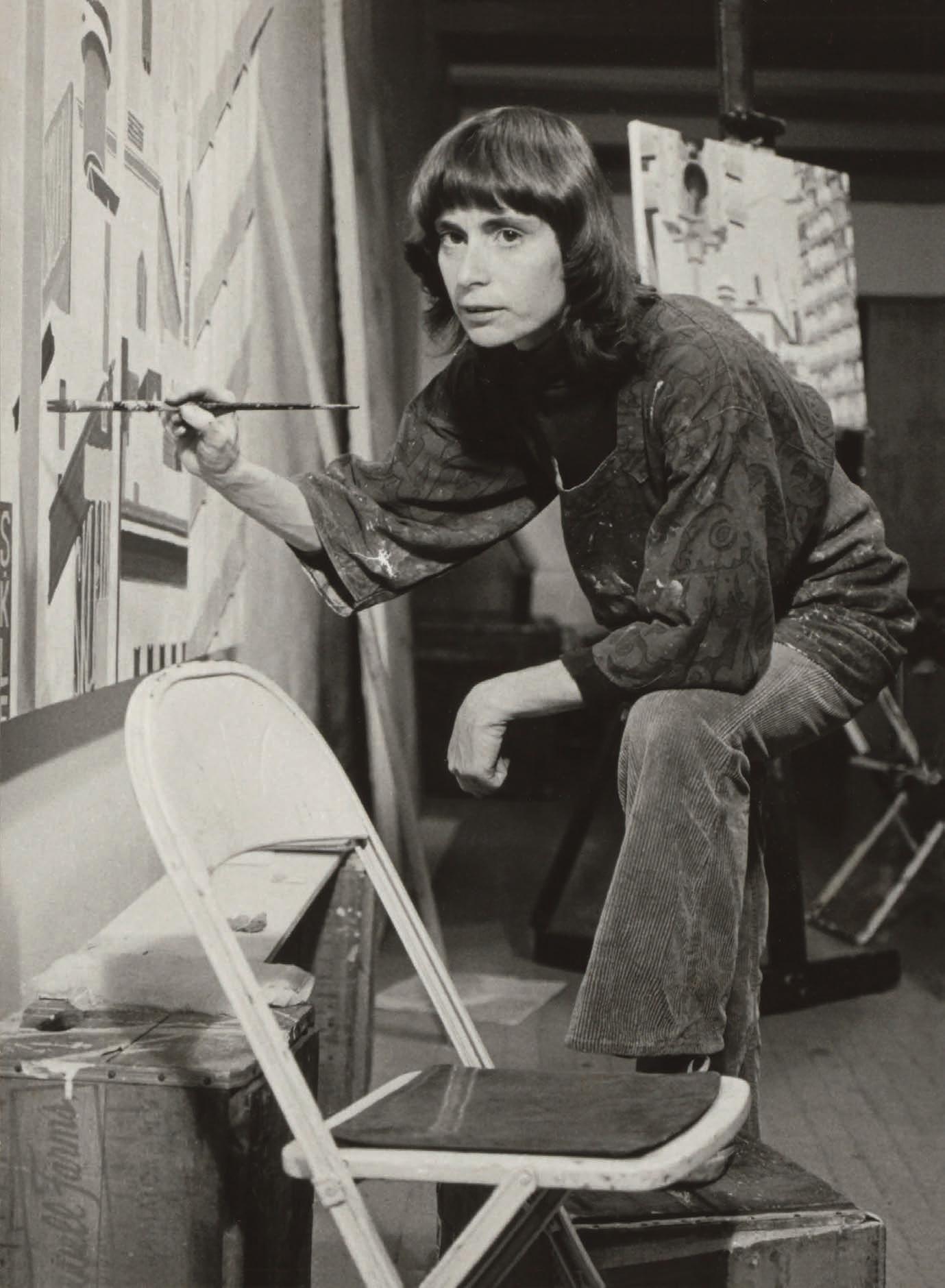

cover : Yvonne Jacquette in Her New York Cit y S tudi o, c. 1973–74

cover flaps : O pen D oor, Tin C eilin g, 1969 (detail)

Acrylic on canvas, 75 1⁄ 2 x 59 3⁄4 inches