R O B E R T

U S H N E R

R O B E R T

U S H N E R

STEVEN WATSON : When I met you in the early 1980 s, you produced a wonderfully quirky multiple for the exhibition Artifacts at the End of a Decade: an ink-drawn face on a mash-up of kitschy wrapping paper and fabric. 1 You de scribed it as “Henri Matisse on an off day.” It’s instructive and joyful to re visit works from that era now and see the changes and continuity in your current work. Certainly Matisse is still inflecting them!

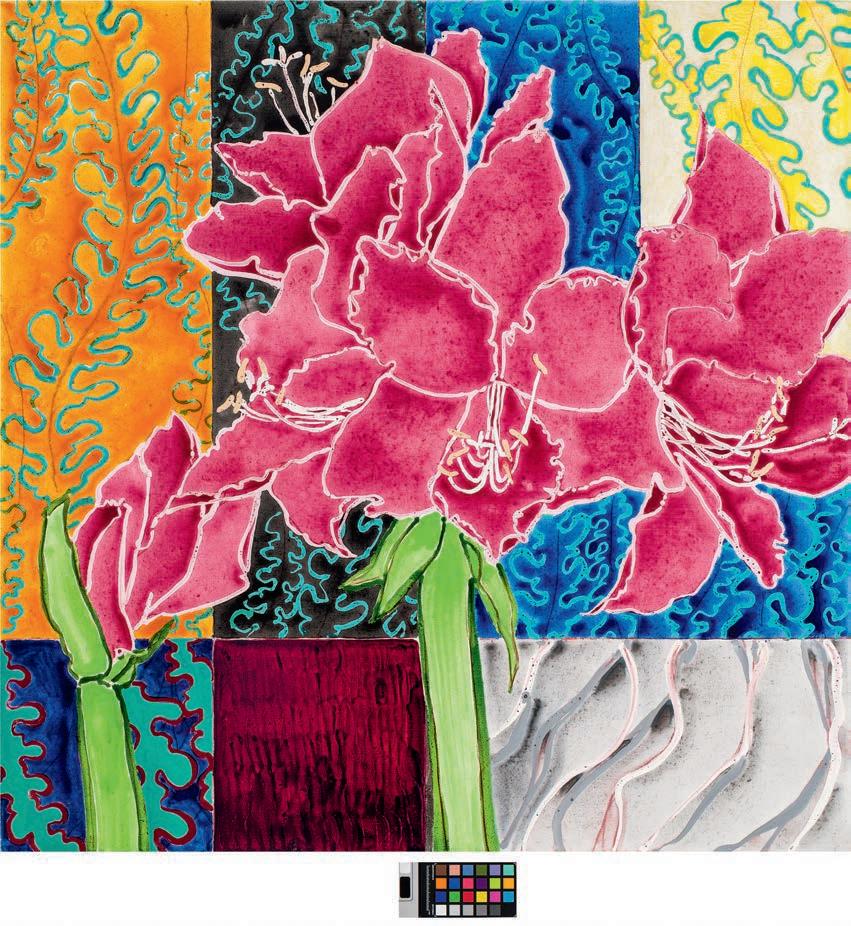

RO B E RT KU SHNE R : In this show, I wanted to exhibit recent paintings side by side with some of my paintings on fabric from the 1970s and 1980s to see how they looked together, how they resonated. And how they might clash. How would Shalimar (1979) with its big curves and lavish colors butt up against For Betty (2022), with its large cut out shapes of two Betty Woodman vases? So far they each hold their own and have an interesting dialogue. Through all these years, some things have remained consistent: my use of high key color, even very specific color harmonies, an overall activation of the surface, patterns, and an expansive flatness that I think of as essential to the tradition I belong to: Decoration.

Art is such a weird proposition because it is simply not necessary.You cannot eat it. You can’t use it to get warm. You can’t put it over your head to stay dry. So you had better have a good reason for making it. Early on, I asked myself the question: how can I make my work reflect the range of art that I so enjoy looking at? I had started to look at Islamic textiles, particularly kilims, which I was restoring professionally. There was also Art Nouveau, Art Deco, architectural or nament in downtown New York, every building has some weird or stylish detail to look at. I wanted my paintings to be as complicated as those sources so that you just want to keep looking and looking at them. Perhaps you might learn your way through the painting, and then I wanted you to come back to it another time and just say, “Ah, I remember, I go from there to there.” I wanted these fabric works to be that rich and that complex. This intention was totally

at odds with the prevailing aesthetic of minimal, reductivist painting that was in the air in the early 1970s. And all those original elements seem to still be present in what I am doing today.

SW • As I’ve followed your recent paintings, I am struck by how your deep love of art history is buried within them. The ebullience of the early work is there but now the complexity has a different, more subtly balanced tenor.

RK • There is an art historical term “late phase work,” artwork that artists create at roughly the age you and I are at right now,in our 70s. And how it is often very different, often it is freer. Like Matisse’s cutouts, like Titian almost becoming an Impressionist at the end, Beatrice Wood the sorceress of luster, de Kooning’s radical embrace of light

This goes on and on with a wide variety of artists, not just the masters. For me at this stage in my studio life, my own big picture is about pulling in as much as possible of my life experience. How wide a net, how big a panorama can I include in the works I am making now? Can I put in everything I know how to do as a painter? Every one of the still life objects has a personal connection for me: who owned it, how it came to me, what it has meant to me over the years. I love the objects, but I also love so much art of the past. Behind you, on the wall, there are two reproductions of Matisse paintings, one from 1911, another from 1918. There is an Indian miniature, and then there is a reproduction of an astonishing Persian miniature from the 17th century. They all pull me in, inspire me, ask to be included in what I am trying to accomplish.

When I am making a new painting, particularly these new ones, I ask: what would Matisse think of what I just did? Would he think that was adding something? Or am I being redundant? Is it exhibiting vigor or intellectual curiosity? I am taking all my heroes and heroines and mentors whether I knew them or not and trying to pull them all together into a raucous colloquium.

It’s like Indian cooking, which I love to do, filled with highly complex flavors. In the kitchen if you do it just right, good ingredients, correct sequencing, it turns into a flavor you never quite tasted before. That’s what I’m trying to do with these paintings.

Textiles are really important to me again, like the huge embroidered Suzani behind us. I can never know who embroidered that. For sure it was a woman

from Uzbekistan, it was for a wedding. Whose? Maybe a century ago? Unknowing is all part of the mix.When I hung that up yesterday, expecting your visit today, it nearly jumped out of my hands. I said, “Oh my, that is really gorgeous. Powerful. What color and boldness!” I felt deeply invigorated. I want to go there too.

S W • On first glance, those early fabric pieces seem so overtly outrageous, funny, and freewheeling. What I think of as your Inner Thirteen-Year-Old It’s only after looking closer that I see the color palette choices and formal considerations that inform the “spontaneity.”

RK • T he early fabric things were done by a young me. There was a huge amount of, “I’ll show you.” I was a really awkward kid. I loved Classical music, art, poetry, crocheting, flowers, and I was not good at sports, which was what you needed to do growing up in suburban California. All filtered through the studio and practice of my mother, an Abstract Expressionist painter. That was my own private world.

In my 20 s, my work was an integration of many weird little textile fragment s my mother’s sewing, my grandmother’s crochet and hat making, my father’s knowledge of fur, my own interest in kilims and 18th century brocades. Our house, my life, was a hotbed of textile creativity. But instinctively, I was always going toward a bigger picture in both the performance costumes and the paintings, questions about gender expectations: why do men do this? And women do that? Not in terms of their proclivities, but in terms of social expectations. Why do men have to wear gray, green, brown, and blue? In terms of flamboyant styles, the hippie era and Carnaby Street had come and gone. Things seemed a little bland again. If you went to a museum opening, the men were dressed one way and the women were Va-Va-Voom. Art was the perfect forum for me to bring up these questions.

SW • For many years you have been working in the same arena flowers and still lifes but your work never becomes a repetitive genre. It’s like a long-term marriage, but sparked by new arousals, dalliances with a specific blossom you found at the Union Square Market.

RK • Thank you, I truly hope there is something new in each series. I don’t start to work until I know what I want to do. I always have a clear concept of scale, motif, color harmony, and what I want the painting to feel like. A popular art pedagogy

today asks the artist to empty their mind and draw freely to find inspiration. But all the “freedom” of this process seems to lead to repetition after a while, everything looks the same. On the contrary, I need to know what I want to create. I never sit down and say, “Oh, I’ll just fiddle around.” No matter how wild and chaotic the end result might appear, being clear and focused is really essential to me.

SW• The way we usually know that we are looking at Art is that it lives in a frame or perches on a pedestal. Your unstretched pieces painted with acrylic on cot ton had neither of those, and they subverted so many expectations. I am curious about your transition to canvas and oil paint.

RK

• The transition from the fabric paintings to canvas was around 1987 or 1988. I had several frustrations with the way I was working with acrylic. I felt like for me at that time the colors as applied to unprimed cotton were repetitive. And there was not as wide a range of actual pigments as there was with oil paint. At the time I was looking more at early modernism rather than my textile and decorative sources. Pierre Bonnard, Charles Demuth, Raoul Dufy, Juan Gris, Henri Matisse, Georgia O’Keefe, Odilon Redon, Florine Stettheimer. A lot of School of Paris. Also a lot of Japanese and Chinese decorative painting.

I wanted to see what it was like referring to those sources working with their chosen materials oil on canvas. Being me, I added collage, acrylic paint and glitter. I also wanted to work smaller. Many artists like to start small and then scale up. For me, the opposite is true. It is a lot easier for me to work bigger than smaller. And I wanted to see what it was like to work with a material all new to me oil paint.

SW • In many of your early works, the space is resolutely flat, the colors and patterns shifting around on a two-dimensional decorative surface. But in the new still lifes, is there something else going on?

RK• One of the unexpected rewards of looking closely at Matisse still lifes is observing his rigor in maintaining spatial coherence in the still life composition. I love to try this in my own paintings, and then I feel free to subvert the urge. Flattening the space gives me many new and interesting ways to paint the tablecloth meeting the wall, the edge of the table, the floor. Or watching those pesky horizontal planes relinquish their assigned proper locations and float free like flying carpets.

Visions

SW• You live an extremely ordered domestic and spiritual life, and your hours for painting are sacrosanct. Within that structure, you continually pose new aesthetic problems and challenges for yourself. I think of it as the daily fight against falling into automatic patterns in making art.

R K • For me, the goal is about making myself experience something new, and sometimes it takes me a while to find it. But then once I do, I run with it. I never get tired of painting certain flowers, and now that applies to some of my favorite still life elements as well. But they have to say and do something new to keep my interest. Overall, if it is not interesting, why do it? You know, I think my idea of hell would have been Josef Albers. “Look, Anni [Albers], I did it I finally made all three squares in gray today!” “Oh, Josef, that’s so wonderful. Now come have your lunch.” With all due respect, what’s the point of that? Why not make it hard for yourself? Or at least maybe not hard, but why not make it interesting? It sometimes comes unexpectedly. And in these new ones, Matisse, with all the complexity and innovation of his lifetime quest, just keeps reappearing, unfolding. At this point I am not copying particular paintings, but the Matissean inspiration is there. In this show two paintings Pink Studio I and Pink Studio II were the result of a close read of Matisse’s Pink Studio (1911). In the Matisse, there is a small wooden table with several strange objects on it. We have almost the same table. So I said, “Aha. What if I put OUR table front and center?” I hung some kimono fabric behind it, placed a few objects, a vase, some fruit on the table. And I was off and running.

SW• Your recent work was made in a dark period of political unrest, during a time when solitude and interiority was enforced by the Covid pandemic. Do you see any reflections of that in your new paintings?

R K • Definitely. This has been a rough time for society and for many of us. I think these new works of mine offer a considered alternative to the isolation and darkness of these last few years. Sometimes I worry that the paintings themselves might be a little too sweet. And then I say, yeah right. In this day and age, we could use a little gentleness and kindness. In so many ways, life and events are frightening, even awful right now. Why not go for refuge? Matisse’s famous/ infamous armchair ? 2 To paraphrase from Matisse’s original 1908 statement from Notes of a Painter: “ I dream of an art of balance, of purity, of tranquility, without any unsettling or worrying subject matter; an art that would be,

for any intellectual laborer for the businessperson as well as the literary artist, for example a balm, a remedy to soothe the mind, something analogous to a good armchair that relieves them of their physical fatigue.” This is actually a big point I wanted to make. Why not view art as someplace that you want to go to and inhabit when you are exhausted? I feel used up thinking about the abrasive and divisive politics out there today, the fact that a large country is piecemeal destroying a smaller country and we are watching it on a daily basis. What about illnesses and the pandemic and the knowledge there will be more of them? The fact that the environment is going down the tube in every conceivable way and it feels close to hopeless? But with all these concerns weighing on us, is it possible for me to give you a momentary respite that is relevant right now? In today’s art world there is a tremendous emphasis on the role of the artist to raise socially uncomfortable questions. Fair enough. But there is also another option for the artist: to give you solace, to offer you another place to park your mind. Give you an escape, an alternative to the grimness of what we are living through. And a vision of dwelling for a bit of time where we would prefer to be.

SW

• It’s like being in Arcadia both the mythic and the real place.

RK • Yes, Arcadia, California. My own hometown. Idealized bucolic perfection. Gardens and trees. And me hiding in our neighbor’s giant bamboo grove, eating kumquats from the nearby tree. I love those memories and I often return there in my mind’s eye.

1 Artifacts at the End of a Decad e is a wide-ranging collaborative art world time capsule, featuring 44 artists, published in an edition of 100 in 1981

2 “Ce que je rêve, c’est un art d’équilibre, de pureté, de tranquillité, sans sujet inquiétant ou préoccupant, qui soit,

pour tout travailleur cérébral, pour l’homme d’affaires aussi bien que pour l’artiste des lettres, par exemple, un lénifiant, un calmant cérébral, quelque chose d’analogue à un bon fauteuil qui le délasse de ses fatigues physiques ”

– Henri Matisse, Notes of a Painter, 1908

D R STEVEN WATSON is an independent cultural historian who writes about constellations of the twentieth century American avant-garde, including books about pre-World War I bohemia, New York Dada, the Harlem Renaissance, Four Saints in Three Acts, the Beat Generation, and Warhol’s Silver Factory. He has curated two exhibitions at the Na tional Portrait Gallery and directed a documentary for Public Broadcasting System. His decades of shooting oral history interviews about art, performance, literature, and queer culture will comprise a forthcoming website , ARTIFACTS MOVIE

The Lapis Necklace , 1985 Acrylic and silver leaf on mixed fabric, 59 x 85 inches

The Lapis Necklace , 1985 Acrylic and silver leaf on mixed fabric, 59 x 85 inches

SINCE TH E 197 0’S , Robert Kushner has continu ally addressed controversial and often subversive issues involving the interaction of fine art and decoration, and is considered one of the founders of the Pattern and Decoration movement.

Kushner first began using textiles and fabrics with acrylic paint in his 1971 early performance pieces. In these performances, the fabrics were both functional pieces and art objects when the costumes were installed on the walls as two dimensional objects.Through his use of fabric and cloth, Kushner connected painting, decoration, and clothing, while also blurring gender issues and questioning stereotypes of artistic practice and materials. By the mid-1970s, Kushner was creating wall-specific fabric paintings, ones that were not a part of a performance. His conscious decision at this time to ignore the rise in popularity of reductivist painting on canvas, and to exhibit unstretched fabrics that were pinned to a wall, was a deliberate action that he continued until the mid-1990s. Kushner felt that stretching the cloth would change the fabric’s inherent qualities of softness and malleability, as well as blur its social and historical implications.

Since 1975, Kushner’s work has been exhibited extensively in the United States, Europe and Japan. In 1984 , Kushner was the subject of one-person exhibitions at both the Whitney Museum and the Brooklyn Museum, and in 1987 , a mid-career sum -

mary of his work was organized by the Philadelphia Institute of Contemporary Art. Kushner’s work was also featured in the 1979 and 1981 Venice Biennales and the 1975 , 1981 , and 1985 Whitney Biennials. In 1988, Kushner began to explore painting and collage on canvas. In order to achieve the same richness of color that he achieved from applying acrylic paint on cloth, Kushner incorporated oil paint into his works. Though there was a fundamental shift in his practice at this time, Kushner continued to use color and pattern as building blocks in his paintings, featuring flowers as a constant theme.

In recent years, Kushner has been included in numerous exhibitions including: P attern and Decoration: Ornament as Promise , Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, Aachen, Germany (traveled to mumok Vienna and the Ludwig Museum, Budapest); Pattern, Decoration & Crime , Le Consortium, Dijon ; Les Chemins du Sud, Musée Régional d’Art Contemporain, Sérignan, France; Les s is a B ore: Maximali st Art and Design, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972 –1985, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and the Hessel Museum of Art, Annandaleon-Hudson, NY; and Greater New York at MoMA

P.S.1. Kushner’s works are included in numerous prominent public collections in the United States, Europe, and Asia.

Young Fig Tree II , 2022 Oil, acrylic, and conté crayon on linen, 72 x 36 inches

Young Fig Tree II , 2022 Oil, acrylic, and conté crayon on linen, 72 x 36 inches