CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF

AWARDS

COLUMNIST & INTERNATIONAL EDITOR-AT-LARGE Baz Bamigboye

EXECUTIVE MANAGING EDITOR Patrick Hipes

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR & BOX OFFICE EDITOR Anthony D’Alessandro

SENIOR

SENIOR

MANAGING

DEPUTY

SENIOR

POLITICAL EDITOR Ted Johnson

INTERNATIONAL TELEVISION EDITOR Max Goldbart

INTERNATIONAL FEATURES EDITOR Diana Lodderhose

INTERNATIONAL BOX OFFICE EDITOR & SENIOR CONTRIBUTOR Nancy Tartaglione

INTERNATIONAL TELEVISION CO-EDITOR Jesse Whittock

ASSOCIATE EDITOR & FILM WRITER Valerie Complex

ASSOCIATE EDITORS Greg Evans Bruce Haring

CONTRIBUTING EDITOR, ASIA Liz Shackleton

SENIOR TELEVISION REPORTER Rosy Cordero

SENIOR INTERNATIONAL FILM CORRESPONDENT Melanie Goodfellow

DEADLINE.COM

Breaking News Follow Deadline.com 24/7 for the latest breaking news in entertainment.

Sign up for Alerts & Newsletters

Sign up for breaking news alerts and other Deadline newsletters at: deadline.com/newsletters

VIDEO SERIES

The Actor’s Side Meet some of the biggest and hardest working actors of today, who discuss their passion for their work in film and television. deadline.com/vcategory/theactors-side/

Behind the Lens

Explore the art and craft of directors from first-timers to veterans, and take a unique look into the world of filmmakers and their films. deadline.com/vcategory/ behind-the-lens/

The Film That Lit My Fuse

Get an insight into the creative ambitions, formative influences, and inspirations that fuelled today’s greatest screen artists. deadline.com/vcategory/thefilm-that-lit-my-fuse/

PODCASTS

20 Questions on Deadline

Antonia Blyth gets personal with famous names from both film and television. deadline.com/tag/ 20-questions-podcast/

Scene 2 Seen

Valerie Complex offers a platform for up-and-comers and established voices. deadline.com/tag/ scene-2-seen-podcast/

Crew Call

Anthony D’Alessandro focuses on the contenders in the belowthe-line categories. deadline.com/tag/ crew-call-podcast/

SOCIAL MEDIA

Follow Deadline

Facebook.com/Deadline Instagram.com/Deadline Twitter.com/Deadline YouTube.com/Deadline TikTok.com/@Deadline

CHAIRMAN & CEO Jay Penske

VICE CHAIRMAN Gerry Byrne

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER George Grobar

CHIEF ACCOUNTING OFFICER Sarlina See

CHIEF DIGITAL OFFICER Craig Perreault

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, BUSINESS AFFAIRS & CHIEF LEGAL OFFICER Todd Greene

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, OPERATIONS & FINANCE Paul Rainey

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, OPERATIONS & FINANCE Tom Finn

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCT & ENGINEERING Jenny Connelly

MANAGING DIRECTOR, INTERNATIONAL MARKETS Debashish Ghosh

EVP, GM OF STRATEGIC INDUSTRY GROUP Dan Owen

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, SUBSCRIPTIONS David Roberson

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, DEPUTY GENERAL COUNSEL Judith R. Margolin

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, FINANCE Ken DelAlcazar

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, HUMAN RESOURCES Lauren Utecht

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Marissa O’Hare

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, CREATIVE Nelson Anderson

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, LICENSING & BRAND DEVELOPMENT Rachel Terrace

VICE PRESIDENT, ASSOCIATE GENERAL COUNSEL Adrian White

VICE PRESIDENT, HUMAN RESOURCES Anne Doyle

VICE PRESIDENT, REVENUE OPERATIONS Brian Levine

HEAD OF INDUSTRY, CPG AND HEALTH Brian Vrabel

VICE PRESIDENT, PUBLIC AFFAIRS & STRATEGY Brooke Jaffe

HEAD OF INDUSTRY, TECHNOLOGY Cassy Hough

VICE PRESIDENT, SEO Constance Ejuma

VICE PRESIDENT & ASSOCIATE GENERAL COUNSEL Dan Feinberg

HEAD OF LIVE EVENT PARTNERSHIPS Doug Bandes

VICE PRESIDENT, AUDIENCE MARKETING & SPECIAL PROJECTS Ellen Deally

VICE PRESIDENT, GLOBAL TAX Frank McCallick

VICE PRESIDENT, TECHNOLOGY Gabriel Koen

VICE PRESIDENT, E-COMMERCE Jamie Miles

HEAD OF INDUSTRY, TRAVEL Jennifer Garber

VICE PRESIDENT, ACQUISITIONS & OPERATIONS Jerry Ruiz

VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCTION OPERATIONS Joni Antonacci

VICE PRESIDENT, FINANCE Karen Reed

VICE PRESIDENT, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY Kay Swift

VICE PRESIDENT, HUMAN RESOURCES Keir McMullen

HEAD OF TALENT Marquetta Moore

HEAD OF AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY Matthew Cline

VICE PRESIDENT, STRATEGIC PLANNING & ACQUISITIONS Mike Ye

VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCT DELIVERY Nici Catton

VICE PRESIDENT, CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE & MARKETING OPERATIONS Noemi Lazo

VICE PRESIDENT, ASSOCIATE GENERAL COUNSEL Sonal Jain

VICE PRESIDENT, ASSOCIATE GENERAL COUNSEL Victor Hendrickson

DEADLINE HOLLYWOOD IS OWNED AND PUBLISHED BY PENSKE MEDIA CORPORATION

Nellie Andreeva (Television) Mike Fleming Jr. (Film)

COLUMNIST & CHIEF FILM CRITIC Pete Hammond

EDITOR, LEGAL & TV CRITIC Dominic Patten

MANAGING EDITOR Denise Petski

EDITOR Erik Pedersen

MANAGING EDITOR Tom Tapp

TELEVISION EDITOR Peter White

INTERNATIONAL EDITOR Andreas Wiseman

BUSINESS EDITOR Dade Hayes EDITOR-AT-LARGE Peter Bart

FILM CRITIC & COLUMNIST Todd McCarthy EXECUTIVE EDITOR Michael Cieply

FILM WRITER Justin Kroll CO-BUSINESS EDITOR Jill Goldsmith LABOR EDITOR David Robb

FILM REPORTER Matt Grobar INTERNATIONAL FILM REPORTER Zac Ntim TELEVISION REPORTER Katie Campione NIGHTS AND WEEKENDS EDITOR Armando Tinoco PHOTO EDITOR Robert Lang PRESIDENT Stacey Farish EXECUTIVE AWARDS EDITOR Joe Utichi VICE PRESIDENT, CREATIVE Craig Edwards SENIOR AWARDS EDITOR Antonia Blyth TELEVISION EDITOR Lynette Rice FILM EDITOR Damon Wise DOCUMENTARY EDITOR Matthew Carey CRAFTS EDITOR Ryan Fleming PRODUCTION EDITOR David Morgan EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Destiny Jackson DIRECTOR, SOCIAL MEDIA Scott Shilstone DIRECTOR, EVENTS Sophie Hertz DIRECTOR, BRAND MARKETING Laureen O’Brien EVENTS MANAGER Allison DaQuila VIDEO MANAGER David Janove VIDEO PRODUCERS Benjamin Bloom Jade Collins Shane Whitaker DESIGNERS Catalina Castro Grant Dehner SOCIAL MEDIA COORDINATOR Natalie Sitek EVENTS COORDINATOR Dena Nguyen DESIGN/PRODUCTION COORDINATOR Paige Petersen CHIEF PHOTOGRAPHER Michael Buckner SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Kasey Champion SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, GLOBAL BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT & STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS Céline Rotterman VICE PRESIDENT, ENTERTAINMENT Caren Gibbens VICE PRESIDENT, INTERNATIONAL SALES Patricia Arescy VICE PRESIDENT, SALES & EVENTS Tracy Kain SENIOR DIRECTOR, ENTERTAINMENT Brianna Corrado DIRECTOR, ENTERTAINMENT London Sanders DIRECTOR, DIGITAL SALES PLANNING Letitia Buchan SENIOR DIGITAL ACCOUNT MANAGER Cherise Williams

PLANNERS Luke Licata Kristen Stephens SALES ASSISTANT Daryl Jeffery PRODUCTION DIRECTOR Natalie Longman DISTRIBUTION DIRECTOR Michael Petre PRODUCTION MANAGER Andrea Wynnyk

SALES

First Take 4 PAUL MESCAL: Dad and loving it: the Irish “co-star” of indie hit Aftersun 8 QUICK SHOTS: Walking the talk in She Said and dressing for duress in Women Talking 10 THE BIG REVEAL: Top Gun: Maverick director Joseph Kosinski’s personal stories behind the film. 14 INTERNATIONAL: How Ireland’s The Quiet Girl became a success. 18 DOCUMENTARY: Put your arms around the world at Oscar time. 22 FRESH FACE: All Quiet on the Western Front star Felix Kammerer. Cover Story 24 TRIO OF LIFE: Alfonso Cuarón, Alejandro G. Iñárittu and Guillermo del Toro get the old gang back together. Dialogue 36 BARRY KEOGHAN 38 CHINONYE CHUKWU 40 GRETA GERWIG 42 PARK CHAN-WOOK 46 JESSICA CHASTAIN 48 EDDIE REDMAYNE 50 JENNY SLATE 54 RYAN COOGLER 56 KATE HUDSON 58 BITATÉ URU EU WAU WAU 62 CAREY MULLIGAN 64 SARAH POLLEY 66 PAUL DANO Craft Services 70 CUTTING TO THE CHASE: Three editors on getting historical for The Woman King, All Quiet on the Western Front and Emancipation The Partnership 76 JAMES GRAY & JEREMY STRONG: New York state of mind: the making of Armageddon Time ON THE COVER: Alfonso Cuarón, Alejandro G. Iñárritu and Guillermo del Toro photographed exclusively for Deadline by Josh Telles.

FOR DEADLINE CALL SHEET

MICHAEL

BUCKNER

F T I A

R K

S E

THE PARENT TRAP

How Paul Mescal tapped into the joy and pain of young fatherhood in indie hit Aftersun

By Baz Bamigboye

By Baz Bamigboye

T

QUICK SHOTS 8 | THE BIG REVEAL: JOSEPH KOSINSKI 10 | FRESH FACE: FELIX KAMMERER 22

4 DEADLINE.COM/AWARDSLINE

COURTESY

OF A24/ENDA BOWE/HULU/NETFLIX

Paul Mescal enters the north London cafe having trudged a short distance through the snow from his gym. Heads turn, but Mescal is oblivious. He shakes himself out of a hooded coat then nonchalantly removes a sweater to reveal a ribbed torso sheathed in a white T-shirt. More stares. The star of Aftersun, Scottish director Charlotte Wells’s tender visual poem about a father and daughter, takes a seat and rubs his tummy. In that moment it’s all too easy to compare him to Marlon Brando, with the tight-ish whitey shirt and all that.

As it happens, the Irish-born actor is playing one of Brando’s signature roles: the brutish but passionate Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Williams’ landmark play A Streetcar Named Desire, at the Almeida Theatre, a fiveminute walk away from where we’re breakfasting. The revival has been on Mescal’s slate for three years, delayed by Covid and scheduling issues. Early previews merged with an extension of rehearsals due to Lydia Wilson’s withdrawal from the production for health reasons, and she’s since been replaced as Blanche DuBois by Patsy Ferran, a frequent collaborator of director Rebecca Frecknall.

Now in his late twenties, Mescal has been on a roll since the BBC adaptation of Sally Rooney’s 2018 novel Normal People was released on BBC TV and Hulu at the height of the pandemic. Audiences lapped up the painfully honest relationship drama from the comfort of their sofas. The series made Mescal an overnight star, hurling him up the proverbial ladder and winning him the TV BAFTA for leading actor. That capital was used wisely, introducing him into the world of features with a small but significant role in Maggie Gyllenhaal’s acclaimed directorial debut The Lost Daughter as the guileless beach bartender who draws the film’s aloof, prickly protagonist

(Olivia Colman) out of her shell.

It was while preparing to shoot his next film, God’s Creatures, with Emily Watson in Donegal, Ireland, that Mescal got wind of Wells’ Aftersun. His agents, Lara

Normal People

Beach at Curtis Brown and CAA’s Zach Kaplan, were excited about the story of a young, separated father and his pre-teen daughter holidaying at a Turkish resort. The tale, perhaps a distorted memory of a vulnerable father’s unravelling, unfolds through the young girl’s eyes. Mescal pushed to meet Wells, reasoning “any actor who was reading it was gonna want to do it.”

He auditioned for the part of the father, Calum, then did a chemistry read with 12-year-old Frankie Corio, already cast as the daughter, Sophie. This was the real test, he says, because the film “lives or dies”—notwithstanding Wells’ “wonderful script and direction”—on whether you believe in the two actors. Fortunately, he and Corio hit if off straight away. “She’s wild, wild, like Frankie is wild,” he says, his grin widening as he speaks.

For proof, Mescal proudly points to the British Independent Film Awards (AKA the BIFAs), where Aftersun

DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE 5

Frankie Corio as Sophie with Mescal as her father Calum in Aftersun.

The Lost Daughter

won seven awards, including Best British Independent Film and Best Director. At the pre-Christmas awards ceremony in London, Corio’s speech went viral after she playfully roasted Mescal in front of a roomful of industry people, yelling, “I was number one on the call sheet and he was number two—so he was the co-star and I was the star!”

Mescal laughs. “I don’t know if I’m particularly good with kids, generally speaking, but for some reason with Frankie, I found it easy. I can’t explain that other than probably, like, chemistry that exists between people. And we were lucky.”

Asked what poetry might best connect to the film, Mescal cites Thomas Lux’s “My Father Whistled”, which Lux dedicated as “a love poem to my father”. He then recites a line from another poem about a daughter teething for the first time. “It’s so tender,” he says softly. But it’s perhaps Barry Jenkins, one of the film’s producers via his PASTEL production company, who articulated the film’s emotional core more succinctly in The New York Times when he described Calum, a loving but emotionally ill-equipped young man clearly buckling under the pressures of parenthood, as “walking through a world of quiet anguish”.

Mescal nods his head in agreement. “I think it’s spot on,” he says. “I don’t think there’s anything particularly interesting about watching somebody suffering for 96 or 97 minutes. What I think makes it more effective is when you see them trying not to, and I think Calum really doesn’t want to have the set of feelings that he’s been given. And you see him fronting up against that on a daily basis. That, to me, is where… ” He pauses. “It devastates me, you know? It’s like, what is harder to watch than somebody who wants to be better?”

Talk turns to the topic of masculinity, about hiding emotions, and the way men are often slow to look after their mental health. “I think talking to someone

fine. But some people just can’t do it.”

about your feelings is a very, very modern thing,” he says. “Like, when I told my dad that I’d started going to therapy, he went, ‘What? What’s wrong with you?’” He laughs. “Because that’s, culturally, what you do: you go to a therapist if you’re mentally blocked. When I first started spending time in LA, I hadn’t started going to therapy properly. People would look at me like, ‘Why?’ And so, initially, I was defensive. I was like, ‘I’m fine.’ And of course that’s not the point. The point is, the way you look after your body should be the way that you look after…”

Your mind? Mescal nods. “You have to. You have to. I’m very grateful of the time that I’m in now and not 20 years ago, even, where that wasn’t really an option. It wasn’t that it didn’t exist, it just wasn’t really something that people would do. They would just bottle it up. And some people could do it and survive it and be

He says it’s vital that films like Aftersun exist to help trigger debate on subjects that are often put to one side. “There’s a catharsis in watching something that makes you feel,” he says, pointing out that the way Wells’s immersive film deliberately withholds some key information from the audience “forces them to think a little bit more”.

Going forward, Mescal is eager to take the next step, but he admits that it’s a process that scares him. “The thing I’m nervous about is... ” He pauses. “Being totally honest, I have a desire to be liked and for my work to be admired, but that’s not the reason I do it. But I do want to know what people think, and I’m nervous about the next steps. I don’t want to make just movies like Aftersun for the rest of my life. I know that will be the bedrock, but I want to have my cake and eat it. There are other things out there I want to do and try and taste, I’m just scared about being judged for either doing them or not doing them, which is ridiculous, because, so far, I don’t think I’ve made any film, or done any play or any piece of work yet, that I haven’t needed to make. And I don’t see that changing anytime soon.” ★

FT CLOSE-UP 6 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE COURTESY OF A24

Aftersun

Talk

Cinematographer Natasha Braier using the camera as a “good listener” for She Said

When she began her work on She Said, cinematographer Natasha Braier didn’t have a clear-cut idea of how to shoot a film that took place mostly over the phone. Then, she realized that the camerawork needed to follow the conversation, without becoming a part of it. “The camera had to be a listener, had to be a very good listener,” she explained. “You have to listen in a way that was close to them, but not too intrusive because some of these women that are delivering testimony in the film are actual survivors.”

She Said follows the New York Times reporters who broke the Harvey Weinstein story and ignited a movement that gave voice to the silenced victims of sexual assault.

“As a cinematographer, it was important for me to create an environment where they could forget about the camera, where they wouldn’t feel like the camera is invading their personal space.”

Most of the film takes place in the offices of The New York Times, where the reporters are speaking to people over the phone.

While she would normally avoid scripts that didn’t have many visual possibilities, Braier says she felt the need to tell the story and make it visual. “With the phone calls, we try to introduce a lot of movement.

Fleming

Traditionally Modern

How costume designer

Quita Alfred honored Mennonite communities with accurate outfits

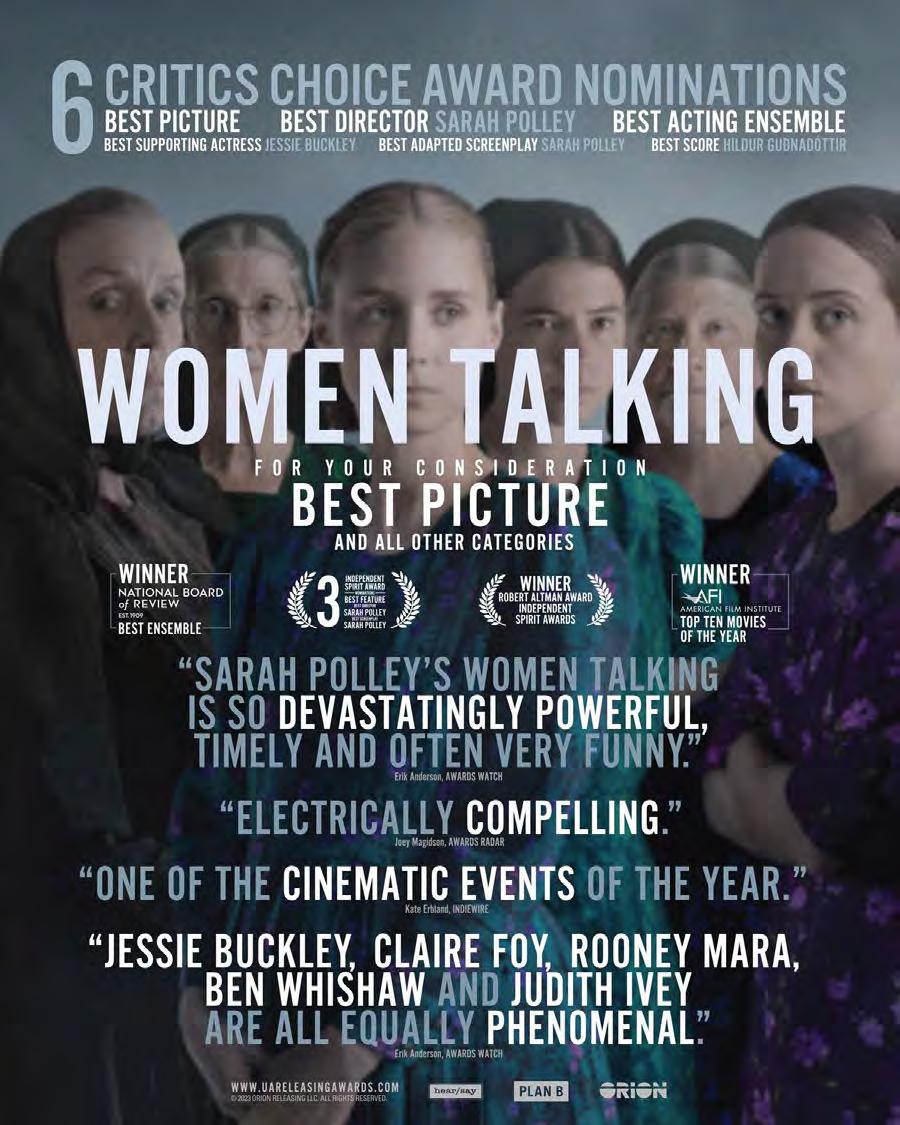

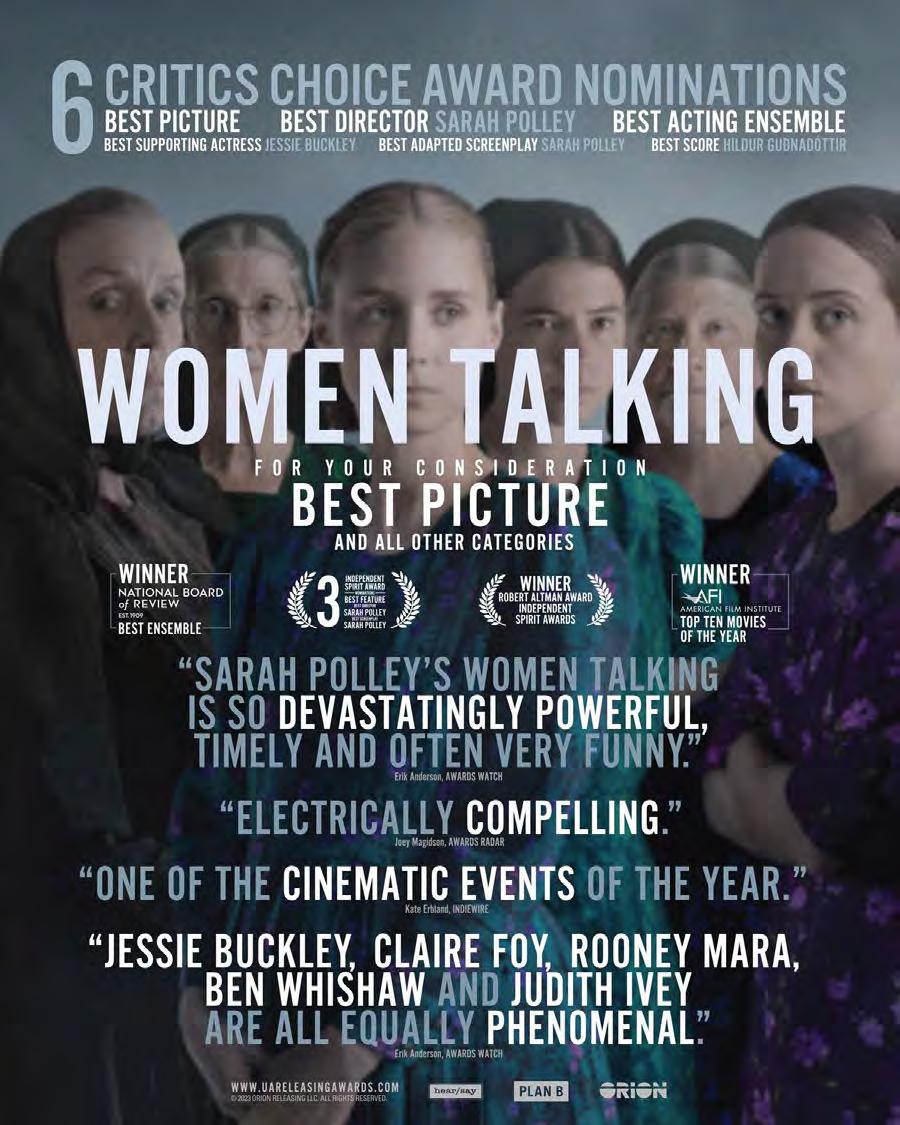

When costume designer Quita Alfred was approached by director Sarah Polley for Women Talking, Alfred was already living close to a Mennonite community

in Winnipeg. “I brought to Sarah the reality of Russian Mennonite plain dress,” she says. “I was able to buy the real things, the real fabrics from real vendors who sold exclusively to Mennonite communities and colonies.”

Using the same fabrics used in Mennonite communities today, Alfred says her costumes needed to be primarily made of polyester. “That’s what vendors have available

and it’s affordable in those remote communities and colonies. We used stronger colors and bolder patterns for characters of the same nature, but we couldn’t add a collar or change a neckline because that’s all very strictly traditional.” Though the traditional style of the clothing may seem simple, Alfred says the styles are “the culmination of 500 years of the Mennonites’ travels through Europe.” —Ryan Fleming

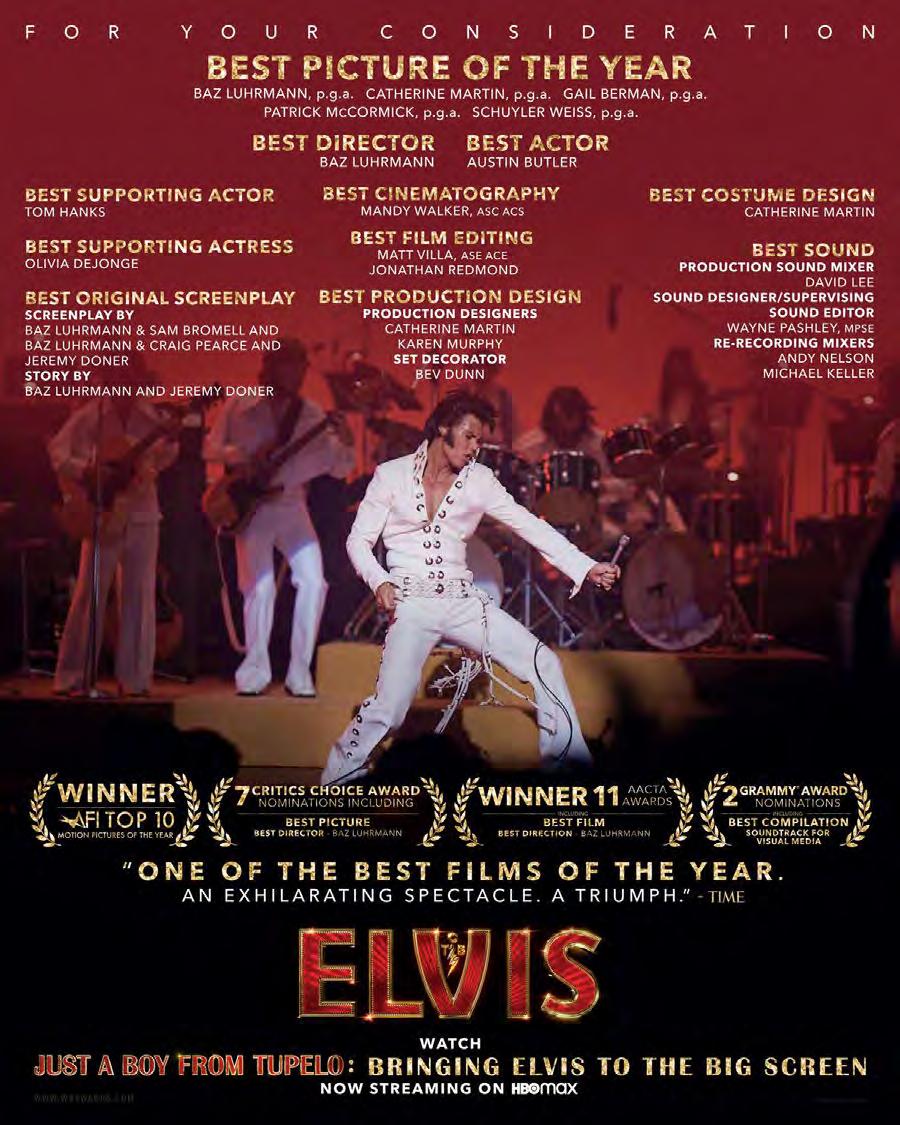

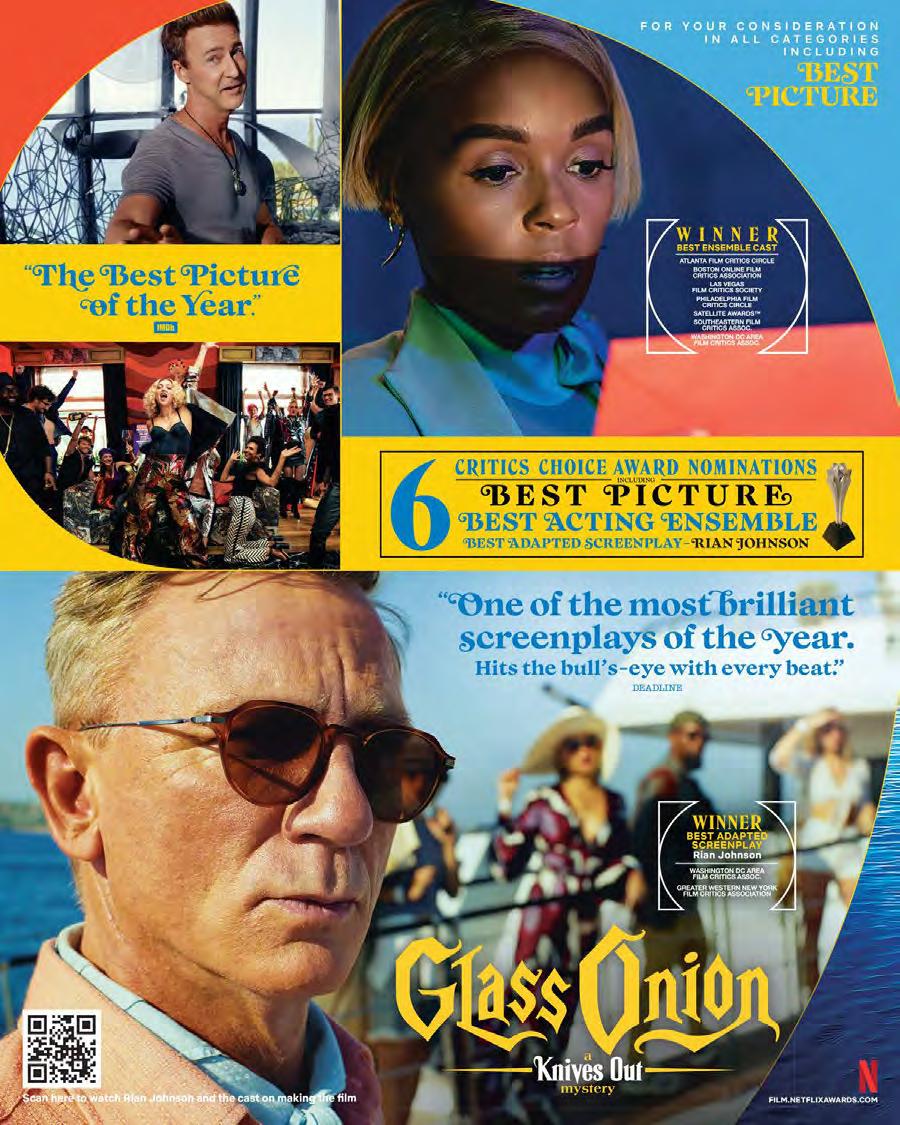

8 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE 1 The Fabelmans ODDS 7/1 2 Everything Everywhere All at Once ODDS 15/2 3 Top Gun: Maverick ODDS 8/1 4 The Banshees of Inisherin ODDS 8/1 5 Avatar: The Way of Water ODDS 10/1 6 TÁR ODDS 21/2 7 Women Talking ODDS 12/1 8 Elvis ODDS 13/1 9 Glass Onion ODDS 28/1 10 The Woman King ODDS 30/1

&

Best Picture At press time, here is how GoldDerby’s experts ranked the Oscar chances in the Best Picture race. Get up-to-date rankings and make your own predictions at GoldDerby.com Charted Territory Walk

FT QUICK SHOTS JOJO WHILDEN/UNIVERSAL PICTURES/UNIVERSAL PICTURES/MICHAEL GIBSON/ORION PICTURES/COURTESY EVERETT COLLECTION

We try to capture them on the move from one place to another, or from their desk to a place where they can hear better… those movements really helped with those moments.” —Ryan

Costume designer Quita Alfred.

Natasha Braier on set.

Women Talking

She Said

TOP GUN: MAVERICK

By Antonia Blyth

Tom really didn’t want to make another Top Gun and [director Tony Scott’s suicide] made it even less likely. I’m sure for him, that’s probably another reason why he wouldn’t ever consider going back. But I pitched the idea of this story being a reconciliation between him and Rooster set against this mission that would take Rooster into this very dangerous situation, that they’d end up together across enemy lines, having to resolve their differences and work together to get back home. As soon as I pitched that idea, I could just see the wheels in Tom’s head start to turn and all of a sudden, he had a very emotional reason, a hook back into this character, and a reason to come back, because I think in his mind it was like a one in a million shot that we would be able to get it right. He kept saying, “Joe, we got to hit a bullet with a bullet.” And that was his line on this movie. And so, I certainly heard that in my head every day as we were making the film. I think everyone who worked on this film felt like the bar was very high because we all were fans of the original.

Val Kilmer was the one who came up with the idea to make Iceman ill. I’ll never forget the shoot day with him and Tom. That scene with those two guys, two actors at their absolute best pulling off a scene like that, their first time together on camera since 1986. The friendship between the two, the mutual respect between the two of them as real people very much mirrors the characters. So, I think that’s why that scene lands so well. When we were putting the film together, we all wanted Val to be a part of it, but we just didn’t know what was possible. So, we had Val come in and said to him, “We’d love to have you in this film.” It was his idea to make it feel as authentic as possible. Once he had that idea, it opened up that whole storyline and just allowed us to tell this story in a better way. I was blown away when he offered that up. The scene was intense and very emotional, but when the camera wasn’t running, hearing him and Tom talk about the hijinks of making the first film and how much fun they had and the tricks they were pulling on each other, and just the craziness of that time and that era, was really fun to listen in on. You really felt that connective tissue to the past.

It was a very, very difficult world to live in and shoot a movie in. I spent two weeks on an aircraft carrier, and that was tough. And the fact that these people do that for six months or nine months without seeing their families, I was just really blown away by their sacrifice and what they give up to do that job for us. So, I think all of us on the crew walked away with even more respect for all the men and women out there. And that’s another reason we wanted this film to represent them in the best way possible. Because they worked so hard to help us capture all that. Every flight was flown by real Navy personnel. Every time you see Phoenix flying in the film, she’s being flown by a female aviator. The Navy has very different personnel than it did in 1986. The movie Top Gun: Maverick represents the Navy of today as opposed to the Navy of 1986. And that’s how far it’s come and how different it is now than then. So, it was good that our film was able to represent that in a really authentic way.

Tom was jumping off the roof of his house as a kid. He’s just always been that way. So, for him, he loves [stunts]. He’s always very well-trained and is working with the best people. To an outsider, it does look insane. But I

10 DEADLINE.COM

Director Joseph Kosinski tells some personal stories behind the successful sequel and this season’s biggest splash

From left: producer Christopher McQuarrie, Tom Cruise, director Joseph Kosinski and producer Jerry Bruckheimer.

PARAMOUNT PICTURES/COURTESY EVERETT COLLECTION FT THE BIG REVEAL

From left: Danny Ramirez, Glen Powell, Monica Barbaro, Joseph Kosinski and Lewis Pullman on the Top Gun: Maverick set.

think for him; he’d want to be doing nothing else. It’s his dream. He’s living his dream every day on a movie set doing these things. So, for him to do it is one thing. But on this film, I had all the other actors [flying for real] too. They all wanted to do it to prove they could do it, and to deliver something really special. Because once we saw the footage they were getting, it was undeniable. As soon as they landed, we’d put the chips from the cameras into the monitor and we’d sit and watch it, and everyone would cheer when you saw those great moments. The other thing is, I knew they were in the hands of truly the best aviators in the world. I mean, when you saw how professional these Navy pilots were, it does look incredibly dangerous and thrilling and exciting. But that’s what these people do every day.

You’re pulling 6, 7, 7.5 Gs in the jet, and that’s incredibly draining. The actors were wiped out. Some days, we would have the actors fly in the morning and the afternoon and that’s when people would get sick. People would be just exhausted. It was really, really difficult. Even for the real pilots themselves, that’s a lot of work. One day the weather was so beautiful, Tom came up to me and said, “I think I should go three times today.” He’s like, “Joe, when you see this footage, you’re going to be blown away.” So, Tom went up and shot his third act sequence, which is the big bombing run. He came back, and

it was the last debrief of the day. I think all the other pilots had gone back to their trailers, and Tom came in and he collapsed in a chair, and he had his black Ray-Bans on. I said, “Tom, how’d you do?” And he said, “We crushed it.” It was very Maverick/Tom Cruise. Is there a difference?

I had a huge love of aviation growing up. I was building model airplanes, really complex radio-controlled airplanes and flying them around. The first thing I did after getting this job was, I flew out to the Teddy Roosevelt aircraft carrier. I jumped on a Greyhound, which is not the fast jet, but I did get to fly out there and catch the cable, and then I got the catapult launch off the jet. When you’re directing the film, you kind of get to become a ‘subject matter expert’, which is the Navy term—the SME—on any subject you want. So, I got to live that dream of being in the Navy for a couple years. I got to go to places that civilians don’t get to go to. I got to see things that no civilian would get to see. I had my camera confiscated at one point. Wiped clean. I took some pictures and maybe captured something I wasn’t supposed to capture, and my camera was quickly returned to me without any photos on it. I got to go to China Lake and shoot in a hangar that is top secret. And it was all in this quest for authenticity. And I think you feel it when you see it, because you don’t feel like you’re in a Hollywood-designed setting. There’s a reality to it.

We collaborated with the actual engineers who make the real secret aircraft. It was just a dream come true.

Films from the ’80s are ones that people keep going back to because of that strong story foundation. Top Gun is one of those movies I remember seeing in the theater, along with Raiders of the Lost Ark and Back to the Future. I think that era was storydriven—certainly, there were visual effects, but not at the level you have now—because the story had to carry the film and visual effects could add a little special sauce on top. I think even Star Wars, which you think of as a giant effects film, had something like 400 shots in it, compared to movies now which have 2,500 or 3,000 effects shots. So, they had to have a fundamentally strong story to draw you in. I remembered that

experience of seeing Top Gun as an 11-year-old kid. So, when Jerry Bruckheimer sent me an early draft of Maverick, I had all those recollections, memories and feelings of what that movie felt like. ★

12 DEADLINE.COM

Clockwise from below: Iceman and Maverick; McQuarrie, Tommy Harper, Bruckheimer and Kosinski; Cruise in flight.

FT THE BIG REVEAL

PICTURES/COURTESY

Top Gun: Maverick

PARAMOUNT

EVERETT COLLECTION

GIRL POWER

How Ireland’s The Quiet Girl became a surprise stalking horse in the International Oscar race

By Damon Wise

By Damon Wise

For the last three years, the winner of the International Oscar has pretty much been a given: First came Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, then Thomas Vinterberg’s Another Round, and then Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car—all anointed by Cannes and eased to the finish line after prominent festival play in the usual cosmopolitan areas.

This year’s shortlist, however, paints 2022 as being far from such a one-horse race. True, the supremacy of Cannes as the foreign-language kingmaker is unchallenged, having berthed nine of the 15 contenders, and it’s worth wondering whether Triangle of Sadness would be the film to beat had its director, Sweden’s Ruben Östlund, filmed it in his native tongue. And, yes, once again, the field is overwhelmingly male, with just three female-directed titles—Morocco’s The Blue Caftan, France’s Saint Omer and Austria’s Corsage—vying with heavyweights like Park Chan-wook (South Korea) and Alejandro G. Iñárritu (Mexico) for inclusion in the final five.

However, the anomaly in this year’s shortlist is a film that challenges the usual notions of representation in the category. Based on the novella Foster by Claire Keegan, Ireland’s entry The Quiet Girl tells the story of Cáit, a 9-year-old girl who is sent away by her dysfunctional family to live with relatives in the country during the summer of 1981. One of a handful of films made by largely English-speaking countries to be submitted to the Academy (another being Australia’s You Won’t Be Alone, filmed in Macedonian), The Quiet Girl is filmed entirely in the Irish language, a form of Gaelic, which poses some interesting questions about cinema and national identity.

For director Colm Bairéad, making the shortlist was an achievement in itself. “We knew from the outset that we would be eligible,” he says, “but we also knew that the task of competing at that level— against the very best of world cinema—was an extraordinarily difficult one. So I kind of pushed that notion to the back of my mind and just focused on making a film that would appeal to my own sensibility.”

But after the film’s critical reception proved so positive (more on that later), the prospect of getting a nomination in the Best International Feature category quickly became a talking point. Says Bairéad, “No Irish film has ever been nominated in this category at the Academy awards. For an Irish-language film to achieve this would be a monumental moment, both for our country and for our language, which is an endangered language and which has rarely had a voice in the history of cinema.”

Of all the films on the list, Bairéad’s film has had the longest life, premiering in February at the Berlinale’s often-overlooked Generations strand and getting a dual release in the U.K. and Ireland the following May. But the film is still on its path, garnering more and more enthusiastic reviews as audiences continue to discover it.

14 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE

BANKSIDE FILMS/COURTESY EVERETT COLLECTION

FT FOCUS ON: INTERNATIONAL

The Quiet Girl

From left: Kate Nic Chonaonaigh and Catherine Clinch in The Quiet Girl

Was it obvious to Bairéad that his creation would be so enduring? “Well,” he says, “there’s always that moment in the edit when your film—though incomplete—finds its voice for the first time, where you stop looking at the sheet music, so to speak, and just let this thing you’ve assembled speak to you for what it is. I remember at the end of a particular viewing being overwhelmed, emotionally. It’s that magical and slightly dangerous moment where you fall in love with the work. And from that point onwards, you give all of yourself to it and you’re trying to help it to find its fullest expression of itself, in the hope of achieving a similar response in others.”

In terms of the audience reaction, Bairéad credits the film’s success in Berlin and at the Irish Film and Television Awards (AKA the IFTAs), where it picked up seven awards, including Best Film, with creating momentum before the theatrical release.

“It just kept growing and growing,” he recalls, “holding screens across the two territories. In the end, The Quiet Girl ran in cinemas for over six months and grossed over €1 million at the Irish/U.K. box office, smashing the previous record for an Irish-language film and becoming a kind of cultural landmark here in Ireland. Beyond its home shores, it has so far been released in Australia and New Zealand, where it received a phenomenal reception, and it’s still playing in Australian cinemas after nearly four months. Audience reactions at festivals across the globe have been just as encouraging with the film receiving many Audience Awards, so we’re very excited to see what 2023 brings when the film is released in more international territories, including the U.S. [in February].”

The film’s commercial success might even mean that The Quiet Girl has a long shot at appearing in other categories, something that would have been unthinkable five or more years ago. Says Bairéad, “The

success of international films in multiple categories of the Academy Awards in recent years is a good indicator of how the Academy is opening its arms to a broader, more inclusive idea of cinema. Which is, in itself, reflective of a broader audience response, I think.”

He recalls Bong Joon-ho’s Oscar acceptance speech, in which the Parasite director joked about “the one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles”. “People are happily stepping over that now,” he says. “You can feel the energy of that audience online, the fervency with which they engage with this cinema from all over the world; it’s palpable. As for Irish-language film production, it will be really interesting to see what emerges in the coming years in the wake of The Quiet Girl’s success. No one can claim anymore that making a film in Irish is a dead end, either critically or commercially. That veil has been lifted.”

The film’s epic journey has given Bairéad a lot of time to reflect about his film’s meaning and how to interpret its burgeoning popularity.

“You could say that The Quiet Girl is a small story, that it’s

a kind of miniature, and that would be true,” he says. “But, to me, its essence has always felt huge, because it touches upon things that are fundamental to all human beings—the need for love, the question of family, the phenomenon of grief. These things were all present in the story the film was adapted from, which itself had been translated into multiple languages, so it was clear before we began that there was a universality to this story. It was just a question of harnessing that and honoring it in a new medium.”

Looking at the shortlist, The Quiet Girl stands out, alongside Belgium’s Close and India’s Last Film Show, as part of a mini-wave of films this year that treated the inner lives of pre-teen children with care and respect. Might that have something to do with its success? Says Bairéad, “There’s possibly some truth to the idea that films centered on children have the potential for a broader acceptance—it’s difficult for an audience not to care for a child, regardless of what culture that child is coming from or what language they’re speaking. From our own direct experience, audiences everywhere have tended to speak of the film’s beauty, referring not only to the visual presentation of the story or the manner of its telling, but to its deeper meaning.”

Which is?

“‘What will survive of us is love,’ wrote the great poet Philip Larkin. That same message applies to this film.” ★

16 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE A24/MONSOON FILMS/STRAND RELEASING/COURTESY EVERETT COLLECTION

Close

Last Film Show

FT FOCUS ON: INTERNATIONAL

The Blue Caftan

A WIDE, WIDE WORLD

International-themed films dominate this season’s Oscar documentary feature shortlist

By Matt Carey

In theory, international films can earn an Oscar nomination for Best Picture in any given year. But in reality, only a handful have ever attained that distinction, and a single one— Parasite—has claimed the prize.

For a truly global competition—international and American films contending in the same category—one has to turn to the Best Documentary Feature race. This year alone, shortlisted documentaries vying for a nomination originate from China, Vietnam, India, Ukraine, Canada and the U.S.

Vietnamese director Ha Le Diem shot her shortlisted film Children of the Mist in a Hmong community in Northern Vietnam, where teenage girls are routinely kidnapped by male suitors and coerced into marriages. Di, the 14-year-old heroine of the documentary, flirts with a boy who soon abducts her and with help from his family tries to force her to tie the knot.

“New Year is the season of bride kidnapping, and it is allowed,” Di’s mother informs her young daughter. Di observes, “Mum means that if I am kidnapped, I must cope on my own.”

Children of the Mist made the shortlist despite not benefiting from a major distributor. The same is true of Hidden Letters, directed by Violet du Feng and Qing Zhao. That film explores gender relations in contemporary China through the lens of two protagonists who come from a part of the country where

women developed a secret language to cope with suffocating patriarchy.

“Four hundred years ago in feudal society in China, where women had bound feet,” du Feng has said, “and were deprived rights of education, they decided to create their own language by writing poems and songs to give each other hope and dignity… The language survived.”

In an earlier era of the Academy, internationalthemed films like these might have gone unrecognized. But about half a dozen years ago, filmmaker Roger Ross Williams—then a governor of the Academy’s Documentary Branch—began pushing to expand branch membership beyond the traditional profile of white, male and American.

“Now the Documentary Branch is a third international,” Williams says. “We’re the first branch to go from non-gender parity to gender parity. And we have an incredible amount of BIPOC members. We still have a lot of work to do too, but we are the most diverse branch in the Academy.”

Syrian-born filmmaker Orwa Nyrabia, the artistic director of IDFA who joined the Academy’s Doc Branch in 2017, allied with Williams in efforts to increase the branch’s international contingent.

“That was very necessary,” Nyrabia comments. “I think what’s been achieved is an amazing accomplishment. And I think on the Documentary Branch level, Roger Ross Williams has done the Academy a historical favor.”

The impact of the increased international membership can be seen in the roster of documentaries

to secure Oscar nominations in recent years, including a pair in 2022: Flee, the story of a gay Afghan refugee directed by Danish filmmaker Jonas Poher Rasmussen, and Writing with Fire, about Dalit women journalists in North-Central India directed by Indian filmmakers Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh. The Mole Agent from Chile, Romania’s Collective, Brazil’s The Edge of Democracy, Honeyland from North Macedonia, and The Cave and For Sama—both from Syria—are among other recent international documentaries to claim Oscar nominations.

In addition to Hidden Letters and Children of the Mist, the Doc Branch shortlisted several other international contenders, including A House Made of Splinters from Danish director Simon Lereng Wilmont, set in a shelter in Eastern Ukraine that houses neglected children. The vivacity and vulnerability of the young protagonists has touched many viewers.

“I was drawn to Eva,” Wilmont says of one of his subjects, “because of the look in her eye. It had both sadness and joy, and she was doing these cartwheels all the time. And sometimes it seemed like that was her way of getting the anger out, and sometimes it was to celebrate how happy she was.”

One Oscar favorite hails from India: All That

18 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE

FT FOCUS ON: DOCUMENTARY

MOVEMENT/CARGO FILMS/COURTESY

COLLECTION

FILM

EVERETT

Children of the Mist

Hidden Letters

Breathes. Shaunak Sen’s film, winner of the top documentary prizes at Sundance and Cannes, examines two brothers and their assistant in Delhi, India, who rehabilitate birds suffering in the city’s choking air pollution.

“When you live in Delhi, you’re constantly thinking of the air,” Sen says. “The air itself is a palpable, visceral, tactile, heavy, and gray phenomenon and a texture of grayness sort of constantly laminates your life. I was interested in doing something which is like an abstract triangulation of air, bird, humans. And that’s actually how the film began.”

Unlike some other international hopefuls, All That Breathes boasts a major distribution partner in HBO Documentary Films, alongside Submarine Deluxe and Sideshow. HBO Documentary Films, under the leadership of Nancy Abraham and Lisa Heller, also contends with three other films: Moonage Daydream, Brett Morgen’s David Bowie doc; The Janes, by Tia Lessin and Emma Pildes about a group of women who set up a secret network to provide abortion services in Chicago in the 1960s, and All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, the Venice Golden Bear-winning film directed by Oscar winner Laura Poitras (Citizenfour). The latter film centers on renowned photographer Nan Goldin, who successfully pressured major art institutions to cut ties with the Sacklers, the family whose wealth was partly derived from selling the opioid OxyContin.

Neon, the taste-making independent production company and distributor, released All the Beauty and the Bloodshed theatrically. It also distributed Moonage Daydream, the top-grossing documentary of the year, with more than $12 million in receipts worldwide, and another big Oscar favorite, Fire of Love, directed by Sara Dosa, about an adventurous French couple who studied volcanoes but lost their lives to their

scientific obsession.

National Geographic released Fire of Love, scoring a shortlist hat trick with that film, Matthew Heineman’s Retrograde, and The Territory, the feature directorial debut of Alex Pritz. The Territory tells the story of an Indigenous Brazilian tribe attempting to protect its land in the Amazon rainforest from illegal miners, squatters and other invaders.

“One of the most meaningful things for us was that NatGeo supported us in releasing the film in Brazilian theaters. We’ve just come back from opening weekend in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro and 15 cities across the Amazon,” Pritz said last fall. “We’re nearing a hundred festivals now and it’s just been an incredible ride.”

Netflix’s hopes hinge on Descendant, Margaret

Brown’s documentary about people in the Mobile, Alabama area who trace their ancestry to survivors of the last slave ship to enter U.S. waters on the eve of the Civil War. And Sony Pictures Classics has Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song, by Daniel Geller and Dayna Goldfine, about the late Canadian singer-songwriter’s most cherished composition.

“Of all the songs, it feels like the one where, in a way, he distilled so much of his essence,” Geller says. “And that’s probably why it took about seven years for him to write the first version [he] recorded.”

Canadian filmmaker Daniel Roher directed the Oscar favorite Navalny, about the Russian opposition leader who was nearly killed in a Kremlin-conceived poisoning plot. After recuperating in Europe, Navalny returned to Russia and was promptly arrested and imprisoned. At a recent Q&A, the filmmakers were asked about the larger geopolitical context of their film.

“There’s a simple answer, which is, will the world tilt toward authoritarianism?” producer Shane Boris responded. “And the answer is yes,

if we do nothing. And I think that’s what Navalny shows in the most profound way, that it is our responsibility to do something.”

Navalny represents something of an Oscar swan song for CNN Films, the documentary division of CNN that produced RBG and other titles going back a decade. Late last year, new CNN chief Chris Licht announced CNN Films would no longer partner with outside-based filmmakers on projects but instead produce documentaries exclusively in-house.

MTV Documentary Films, which earned an Oscar nomination last year for Ascension, returns to contention with Last Flight Home, Ondi Timoner’s poignant film about her ailing father Eli Timoner, who decided to end his life as permitted under California’s End of Life Option law.

David Siev’s contender Bad Axe, from IFC Films, has gained awards momentum after its debut at SXSW, where it won the audience prize for documentary. Like Last Flight Home, it’s a film that springs from experience.

“It’s an incredibly personal story because it’s a film about my family,” Siev says. “My mother, she’s Mexican-American, and my dad is a Cambodian refugee that came here after the Killing Fields in 1979… It’s a story of hope, resilience and what the American dream looks like in 2020.”

Last year, Summer of Soul—a doc about a se-

ries of groundbreaking concerts by African American artists in Harlem—earned the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature, which was evidence that American-oriented stories still enjoy an advantage when it comes to winning in the category. Whether an international-focused documentary beats the odds this year remains to be seen, but a vital indication will appear when the Oscar nominations are announced on January 24. ★

20 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE FT FOCUS ON: DOCUMENTARY NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC/SONY PICTURES CLASSICS/NEON/COURTESY

EVERETT COLLECTION

The Territory

Fire of Love

Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song

FRESH FACE

By Destiny Jackson

WHO

Felix Kammerer

Age: 27

Hometown: Vienna, Austria

WHAT

In his feature film debut, Austrian theater actor Felix Kammerer delivers a haunting star-making performance in Edward Berger’s German-language rendition of All Quiet on the Western Front. The anti-war drama, based on Erich Maria Remarque’s 1929 novel of the same name, follows a German battalion of spirited young men as they experience the atrocities of war while battling the French on the frontline. More specifically, the soldiers’ road to disillusionment is seen through the eyes of plucky Paul Bäumer (Kammerer) as the damning psychological effects of World War I combat ravage what’s left of his innocence.

For Kammerer, a veteran of stage plays but a newcomer to film, watching himself on the big screen for the first time offered great insight. Upon witnessing the raw expression of trauma and humanity in his performance, Kammerer decided he was on the right career track. “I really liked that I couldn’t see myself on the screen,” Kammerer says. “I had nothing to do with that person. It felt like it was Paul on the screen and me watching this person. For me, that’s a great sign that I have detached from that role so clearly. When I feel that I’m totally fine with what I’m seeing and doing, while at the same time I don’t feel that it’s me, that’s a very important factor. That’s how I know I’ve done a good job.”

WHY

Born to esteemed opera singers, Kammerer’s career choice seemed almost inevitable as he describes it. “Because of my parents, I grew up on stage and in changing rooms and theater houses,” Kammerer recalls. “First, I wanted to be a director, cinematographer, or even a physicist—though I’m bad at math. But then I started acting in youth theater companies, and when I was 17, I realized that acting was something I wanted to study.”

After spending four years at Berlin’s Ernst Busch Academy of Dramatic Arts, Kammerer was handpicked by dramaturge Sabrina Zwach to join the prestigious Burgtheater in Vienna. There, Kammerer would find himself trading in soliloquies for marching orders. At Zwach’s behest, her husband, All Quiet on the Western Front producer Malte Grunert, saw Kammerer during one of his first plays at the theater. Grunert was so impressed by his performance onstage that he offered Kammerer an audition right on the spot after the show and personally recommended him to Berger for consideration. “I owe it to [Zwach] that I’m here where I am now,” Kammerer says. “Her husband came to watch a play and saw me on stage and really liked what I did. That’s how it all started. It was an accident.”

Kammerer did not let the switch from stage to screen faze him. During his six-month prep period, he threw himself into research to help him capture the essence of an early 1900s soldier. In addition to watching films and gaining access to rare pictures and audio files from the beginning of

the 20th Century, Kammerer’s most daunting task was sifting through war letters from the British National Archives’ Letters from the First World War collection. “I observed everything that I found, and read around 2,500 letters from the front,” he says. “It’s so interesting and heartbreaking to read those letters because they’re censored. People didn’t want to tell their families [about the difficulties] of what was really going on. And those letters are their private thoughts. Seeing that helped a lot in preparing me for this role.”

WHEN & WHERE

As for where we’ll see the rising star appear next, Kammerer jokes that he can’t share that classified information just yet. But when he considers the roles he’s aiming at in the future, he says, “I’d like a project that is important in a more universal way. Not just a happy story, but something that tells us something about humankind, about history, something that has many layers and can tell us something about the things we don’t understand about ourselves. Something that makes you feel, ‘Ah, we needed that movie.’”★

22 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE FT FRESH FACE

BAJO/NETFLIX

REINER

Felix Kammerer as German soldier Paul Bäumer.

GETTY

Alfonso Cuarón, Guillermo del Toro and Alejandro G. Iñárritu have forged an unshakeable friendship over years of filmmaking in their native Mexico and internationally. They won five Best Director Oscars and claimed two Best Picture trophies in the space of six years, bolstering the profile of Mexican cinema on the global stage. In their first joint interview in more than a decade, the ‘Three Amigos’ gather with Joe Utichi for a wide-ranging discussion about art, life and the future of cinema.

DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE 25

The

filmmakers Alfonso Cuarón

Guillermo del Toro and Alejandro G. Iñárritu

released three new movies in the space of the same year was 2006. By then, their reputations at home had been established by early successes like Y tu mamá también (Cuarón), The Devil’s Backbone (del Toro) and Amores Perros (Iñárritu) and they had each worked in the U.S., with del Toro and Cuarón stepping into blockbuster cinema with Hellboy and Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban respectively, and Iñárritu directing Sean Penn and Naomi Watts to Oscar nominations with 21 Grams

When they donned tuxedos to celebrate the 79th Academy Awards together on February 25, 2007, the ‘Three Amigos’, as they’d been dubbed, might have considered the evening a high watermark in their respective careers. Iñárritu had been Best Director and Best Picture nominated for Babel; Del Toro had a nod for his Original Screenplay for Pan’s Labyrinth; and Cuarón was nominated for his Adapted Screenplay and Editing on Children of Men.

Few could have predicted then that just a few years later, between

2013 and 2018, Cuarón, del Toro and Iñárritu would split no fewer than five of the six Best Director Oscars and take home two Best Picture trophies for a run of work that firmly established them in the pantheon of cinema history. With Gravity, Birdman, The Revenant, The Shape of Water and Roma, the three filmmakers ascended the Oscar stage to share their unique visions of cinema with the world. And against a political backdrop of anti-immigrant sentiment, they made inarguable statements about the power of the international community of film.

Behind all the pomp, praise and prizes is a friendship and collaboration that has endured for decades. They have supported one another and helped champion new voices, in Mexico and around the world. They have forged successes both together and independently, and they have carried failures for themselves and for each other.

They gather now, for their first major joint interview since 2006, as each of them continues to tread new ground. Alfonso Cuarón is still cooking his next feature, but he has this year produced Alice Rohrwacher’s Oscar-shortlisted short film Le pupille and Rodrigo García’s Raymond & Ray, which premiered at the Toronto film festival. Guillermo del Toro has literally attached his name to two projects this year: anthology series Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities, and his first animated feature Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio, both for Netflix. And Alejandro G. Iñárritu delivers his most personal work to date with Bardo: False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths, in which he takes an unabashed look at his own triumphs and tragedies.

The conversation between the three old friends flows easily and requires little moderation. So obsessive is their interest in their chosen field that ideas become bold, and arguments become (comfortably) heated. But we begin where we should, with a trip down memory lane, and their first encounters with one another…

26 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE

GETTY IMAGES/LIONS GATE/EVERETT COLLECTION//20TH CENTURY FOX/NICK WALL/WIREIMAGE

last time Mexican

,

Alfonso Cuarón, Alejandro G. Iñárritu and Guillermo del Toro at the Academy Awards in 2007.

GUILLERMO DEL TORO: To start chronologically, Alfonso and I met in the ’80s having heard about each other through mutual friends. I remember thinking, ‘Who is this guy who everyone likes?’

When you’re 20 or younger, you’re envious of everybody [laughs]. ‘Why do people like this guy?’

We finally met in the waiting room of Hora marcada, a TV program that I was going to do the makeup effects on; Alfonso was writing and directing. I went in to say, “Look, I’ll do the makeup effects for you if you’ll let me direct and write a few episodes.”

So, we became friends very quickly, and then Alejandro and I met because Alfonso called me and said, “There’s this guy who made a movie called Amores Perros, and he’s a goddamned genius, but he’s also really, really stubborn and he should cut the movie a little bit.” He gave me Alejandro’s phone number and a VHS—which I still have—of an early cut of Amores Perros

He told me, “We’ve all decided that the only guy as stubborn as him is you, so you should go and make him cut the movie.”

ALEJANDRO G. IÑÁRRITU: It was also Antonio Urrutia, no, Gordo?

DEL TORO: Yeah, him and Alfonso both. They said, “He’s a genius, but he’s the most stubborn motherfucker.” And it’s still true today [laughs].

IÑÁRRITU: Look who’s talking [laughs].

Before Guillermo called me, I went to LA to meet Alfonso. He was already preparing Great Expectations, and he was living in the fancy hotel, the Chateau Marmont. He was already kind of a rockstar for me, and I hadn’t met him yet.

I was about to start directing a pilot that I wrote for TV. It was my first attempt to do something that was one hour in length. Alfonso knew my work in advertising a little bit, and he always sent nice comments through Chivo [cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki]. I worked with Chivo before anything, and he had obviously worked with Alfonso by then. So, I went to visit Chivo, and I met Alfonso in the garden of the Chateau Marmont, and we spent two or three hours talking.

I literally went to get his advice, and he was very generous and read what I wrote. He was, in a way, mentoring me, giving advice about casting,

about blocking, things like that. I remember how generous he was, and in that moment, I really appreciated it.

So, I met him in ’95 and then I met Guillermo in ’99, when I was editing Amores Perros. And yes, it’s true that the film was finished. I edited it in my house for eight months and I considered it done, but it’s also true that it did need to be edited down. Guillermo and I spent three or four days in the studio discussing the movie, with him trying to get a little bit of consciousness out of this stubborn guy talking now. And he succeeded, I guess,

because it’s a shorter film as you know it now. Well, how many minutes did you say, Gordo? You said 20, I think, and we lost seven.

DEL TORO: Listen, I still say it and you should take my word for it. I have the VHS. We did lose about 20 minutes. You may have put some back. And we flipped the bank robbery from one reel to another.

IÑÁRRITU: Honestly, maybe it was a masterpiece and you destroyed it. What about that?

DEL TORO: [Laughs] No, but what is great about the three of us is the friendship was formed very fast. Alfonso and I, it was like we’d known each other all our lives, and the same thing was true when I met Alejandro. I felt he wasn’t just a great filmmaker, but a good guy. I liked him.

Theirs was a friendship forged in brutal honesty. As the three filmmakers explain it, nothing is off-limits when it comes to the feedback they offer one another, provided it follows one golden rule...

DEL TORO: The curious thing is we are very different, but we do also have a certain leaning towards philosophies about life that are similar somehow. We don’t see failure or success as defining features. We can see the good in the bad and the bad in the good. We have a dialogue that is very real, and I think that’s what helps us not get lost. It’s helpful to have these two guys to keep me in check, so that I don’t get high on my own supply. We remember, at the end of the day, that we grew up together.

ALFONSO CUARÓN: You can talk about the differences between us, but I see them more as complements, in the sense that I think we’re each very aware of our own limitations and of each other’s strengths. In that sense, even if we have a specific way of how we approach cinema, each one of us always understands where the other is coming from.

That’s great, because when there are disagreements—when I want to do something specific, and one of them puts a red flag on it—I immediately know that it’s something I have to be cautious about. That maybe his solution is not the solution I’m looking for, but that perhaps I have to find some solution.

And I mean, the communication between us is brutally honest. It is brutal. I have tried to have that kind of conversation with other peers, and they don’t like it [laughs].

DEL TORO: It’s true.

CUARÓN: Maybe I can be that brutal with Paweł [Pawlikowski] too, but most people don’t like it, and with Paweł the complementary nature of the relationship doesn’t exist in the same way it exists with Guillermo and Alejandro.

Some of the things Guillermo or Alejandro say to me, they really sting. They sting so bad, and I’m hurt. But the funny thing is that before the anger rises, laughter does, because you feel almost silly to be exposed in such a brutal way. The complement of the three of us is very strange, because it’s like these guys are funhouse mirror versions of myself.

DEL TORO: That’s a great way of putting it. The way we talk to each other, when Alfonso says brutal, he means brutal. You might show them a cut and they’ll tear it apart and go, “Look, no matter what you think this might be, this is what the audience will tell you about it, and this is what the critics will say. Change it or don’t change it, but this is what you must accept.”

DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE 27

Iñárritu directs Amores Perros in Mexico circa 1999.

Del Toro, Iñárritu and Cuarón at the Cannes Film Festival, 2007.

IÑÁRRITU: The nonverbal rule between us is that, more than just being brutal for the sake of it, whenever we have something to say about each other’s work, it has to be something that is both truthful and useful, not destructive. That rule is really important, because I’ll never lie to them, and I know they won’t lie to me.

When I talk to other directors, I don’t have the same depth of relationship that I have with these two. We talk about technical things, stuff that is on the surface. But with these two, the benefit is they know very deeply who I am, and what my motivations are, and what triggers me. That deep knowledge of what needs to be said, and of how to say it in a way that is truthful and useful, is a complex mechanic.

DEL TORO: Alfonso and I co-produced The Devil’s Backbone and Pan’s Labyrinth. We co-produced with Alejandro on Biutiful. The three of us co-produced a movie together called Rudo y Cursi. But it’s more than just producing; I’m inspired by them.

I remember one time I discussed with them writing a one-setting thriller. Alfonso said, “Oh, I’m going to write one myself,” and he wrote Gravity. And I think Alfonso’s experiments with the splice take on Children of Men were incredible additions to the vocabulary of world film. He refined that language in a beautiful way on Children of Men, and I think that somewhat inspired Alejandro to do Birdman

When I saw Birdman, I thought, ‘I’ve got to do The Shape of Water,’ because I was very afraid of how I could do that project for $19.5 million, which is a very tight number. I asked Alejandro how much he spent on Birdman and he told me, and it was something not that high. He said, “A budget is a state of mind,” and I knew then, I could do it.

So, if you ask me, we’re constantly inspiring one another, but we’re also tough. Alejandro and Alfonso have both been really tough with me when I make a mistake. I won’t go into the details because there are NDAs all over the place [laughs], but they’ve told me before: “Don’t do this.” And I go and I do it, and it’s a mistake. We warn each other. Very lovingly, but very sternly.

IÑÁRRITU: For me it’s the same. The work of Guillermo and Alfonso has always been a trigger for inspiration, and they’ve encouraged me to go further and learn about my own approach. As a filmmaker, you’re growing as a person, and as a person you’re changing perspectives, the way you live, the way you experience life, the way things impact you psychologically, spiritually and physically. So, it’s great that we have been able to share those shifts in our perspectives on life and adapting ourselves to what we want to say and the way we want to say it.

Circumstances have a huge impact; you’re always going through periods in your life where you’re getting lost, or you’re on a bumpy road, or you’re particularly inspired and creative. We’ve

28 DEADLINE.COM/AWARDSLINE

VIVIEN KILLILEA/GETTY IMAGES/PICTUREHOUSE/WARNER BROS./EVERETT COLLECTION

been able to manage that by being there for one another so that where one of us is down, the others are super high and can say, “Don’t fuck around, don’t get depressed. Get up. You can do it.” They open the door to things you can’t see in a particular moment. That’s the gift. That’s the blessing. We do make very different films, and we do come from different approaches, but I’m always in awe of what Guillermo and Alfonso can do that I never could. Like Pinocchio, for Guillermo: I wouldn’t even know where to start making a film like that. To see these incredible puppets and the technology he uses, and how he works with stop motion; there’s something about it I can’t even fathom. And yet I admire it and I learn from that.

DEL TORO: I also think we have three dialogues between each other, and at the same time a separate dialogue with the world. I don’t think the world knows Alejandro, I don’t think the world knows Alfonso, and I don’t think the world knows me. No matter how much work we put out, there’s an essence of each of us that is reserved on a human level for those that know us as artists and human beings. We can talk to each other about our craft and our successes in the most personal and philosophical way, and that helps us. I do believe there has been a moment or two where we have saved one another’s sanity at one point or another in our friendship.

Cuarón, del Toro and Iñárritu came of age together during a particular moment in time for Mexican film, and they resolved to lead their industry’s evolution. The creative inspiration they draw from one another is what makes them stronger and bolder as filmmakers, even to this day...

IÑÁRRITU: The only example I can think of for three directors who know each other as well as this is Spielberg, Coppola and Scorsese. They belong to the same generation, the same country, the same drive. The three of us share the same circumstances, coming from the same world, and we understand deeply who we are, not as filmmakers but as people.

DEL TORO: We came up in a different panorama of what Mexican cinema meant to the country and to international audiences. We started changing some of the technical aspects, and some of the presentational aspects of it, and the approach to genre and things like that. It was almost like the ABCs of what we set out to do, and now that is taken for granted.

CUARÓN: In many ways, the goal of our conversations is not even about the films, but about what the films are going to mean in our lives, and how they’re going to keep on building the lives we want. That, for me, is the most important aspect,

to share the success and failure with one another and to understand how that impacts our lives, and what we learn from it.

DEL TORO: It’s so true. Our movies together are not a filmography. They’re a biography of each of us. I see Alfonso’s high school movies, and then his senior movies, and I see how all our preoccupations get deeper. That doesn’t mean they’re more meaningful or not, but they get deeper in the context of who we are as the movies progress.

The first part of our career was how to handle the language of cinema. The latter part of our career is when the language of cinema and who we are start making contact. The films become a lot more personal, not necessarily in visible ways, but sometimes. I think Roma, Pinocchio and Bardo all have that in common, even if one of them is pure biography, one is a classic children’s fairy tale, and the other is obliquely a biography but also isn’t. They are joined in similar ways. Different approaches, but ultimately the way we have deepened in our own biography within film is very similar.

CUARÓN: Symbolic biographies, we can put it that way.

DEL TORO: I remember seeing Amores Perros and thinking, ‘Look at this guy, and his rhythm.’ It was percussive, and it was an incredibly prodigious handling of the tools of cinema. The virtuosity for me on Bardo is a lot more exquisite, a lot more refined. It’s not percussive, but it’s lyrical and really hard to execute. And the way it affects who he is, and the way he views the world, is a lot more delicate. It was the same with Roma

CUARÓN: Everything we say to one another comes from a place of love and generosity. It doesn’t come from competition or jealousy. What happens is that, yes, I see something Guillermo or Alejandro did, and I think, ‘I know nothing.’ I’m in awe. There’s a feeling of admiration, and I’m left to realize that I have a lot of growing up to do in cinema. But then, for as brutal as we can be with one another, when you hear something positive from them it makes you feel that pretty much,

you’re at the same level, just on a different path. I think that’s very reassuring, and it’s what allows for that brutal honesty.

I remember having that same thought when I saw Amores Perros. Besides the filmic aspect and being exposed to that kind of cinema, it also exposed this whole thing of, ‘What the heck have I been doing all these years?’ I found I needed to recover something that was a bit lost.

DEL TORO: When I was finishing Pacific Rim, and Alfonso was finishing Gravity, we showed each other the movies and we were both really happy with what we’d achieved. Then we went together to see Birdman, and we came out and said, “Oh my God. The house wins.”

It’s one of the rare times we went straight to a bar in Santa Monica, the three of us, and we got drunk together, because I remember after Alejandro had done Biutiful, he said, “I want to do something quick and small next.” And his quick, small movie was Birdman [laughs]. It was so demolishing to see what he was doing formally.

IÑÁRRITU: You guys are being very generous, but that’s the beauty of what we’re saying, because the exact same thing happens to me when I see the work of these guys. I will never forget how blown away I was seeing Children of Men for the

DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE 29

Above: Del Toro directs Pan’s Labyrinth in Spain c. 2005. Below: Cuarón directs Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban in England, c. 2003.

first time. I couldn’t understand how Alfonso had done some of those shots. Every single sequence was better than the last.

And I would say, as a Mexican filmmaker, that Cronos is a film that I think triggered in every Mexican filmmaker the idea that it was possible to make something that not only broke the rules of Mexican cinema—that you had to be political or talk about a specific thing—but that also injected genre cinema with a quality and a soul that nobody at the time had done. In a way, it was Guillermo who opened those doors.

We’re sending a lot of flowers to one another, but it is true that the good thing of being inspired by your friends is that it triggers in you not jealousy but awe. It guides and triggers your own sense of self, and pushes you forward to the next thing you should explore.

I think it’s also true that we’re at a moment in our careers where we’re epitomizing what we’ve learned through the years. You can only really explore new languages when you’ve done so many things in the past, so that you can put together everything you’ve learned and at the same time open the door for a new light in the room. I think that’s what we are always trying to do for one another when we talk.

CUARÓN: I’m still amazed and in awe of the possibilities of cinema, including the unexplored ones. To be able to have that conversation and admire other masters—old masters and new ones—to give us cinema that challenges us… I think that spirit is in our conversations.

I don’t think you invent new languages, because in many ways we’ve always tried to honor the language of cinema. I think there are few in the history of cinema who have given us the gift of reinventing and transforming cinema in terms of language, but I think what Guillermo, Alejandro and I try to do is to find out how to serve that language best.

DEL TORO: Yeah, but I think like the Beatles “With a Little Help from My Friends”, we have all sung out of key. Many times, in all the years of knowing

each other. And I know that, regardless of what happens, I’ll have these guys. That’s always the real consolation.

I think we’re also mindful to shepherd new voices, and we need to produce and mentor new directors. We’re very conscious and conscientious about that. Just this year, Alfonso produced a short [Le pupille] and I love that he’s doing that. Every time we produce other directors, we know we’re being part of the flow. Cinema doesn’t start and stop with our generation.

The trio never saw success in the United States as the pinnacle of achievement and have returned to Mexico not only to shoot their projects (even portions of Pinocchio were animated in Guadalajara) but also to support the work of the local industry and to give a leg up for Mexican artists...

DEL TORO: We came from a generation that was completely lost in Mexican cinema—a generation of directors that had to battle a lot of adversity. The people that came after us are doing great, inventive and beautiful things. We feel that even though we’re making movies in America, we carry with us a lot of our roots by producing in Mexico, or by looking at work that’s being done here and helping to boost it.

We belong to a limbo—a bardo—that came out of

seeking to weigh into an industry that was not natural to us. That we have in common. That’s important to say, because when we talk to an American filmmaker that feels they belong completely, we realize we are still doing things that are oddities. We are not completely commercial filmmakers in America, nor are we making movies exclusively about Mexico. We have the bardo commonality that we can articulate between ourselves in a very unguarded way.

The curious thing is that we come from Mexico, we work in America, but I think that we all live in film. We have had residency of cinema, you could say, since we were kids. That’s another country we inhabit.

CUARÓN: In Mexico now, on the one hand there’s a healthy industry for workers in the sense of the amount of work; there’s a lot of production, and that is healthy. I think work conditions are something very important: to create standards for those conditions. Here I’m talking about within the industry in general, not necessarily about filmmakers. With the explosion of series and content for platforms, there’s an immense amount of production but there isn’t a clear regulation for how it should be done, and sometimes the regulations have been inherited from how the old

30 DEADLINE.COM/ AWARDSLINE

A scene from Cuarón’s 2006 release Children of Men , starring Clive Owen.

20TH CENTURY FOX/MURDO MACLEOD/WARNER BROS./UNIVERSAL/EVERETT COLLECTION/VITTORIO ZUNINO/GETTY IMAGES FOR RFF

Left: Iñárritu with Michael Keaton on the set of Birdman in New York, c. 2013. Right: Cuarón shoots Gravity in London c. 2011.

industry used to do it. I think it’s very important to address that, for workers.

The other thing, in the sense of craftsmanship, is that because of the amount of production—and this is something that is being experienced worldwide—young people getting into the industry have a very short time to go through their learning curve. People start work as a third assistant on a production, and then they find themselves as the head of department on the next production because of the amount of production going on. On the one hand that’s great, but on the other, there’s a certain understanding of craftsmanship that comes from experience, and through the elder craftsmen teaching the younger generation the tricks of the trade. That’s a concern I have worldwide because it’s not just happening in Mexico. There’s always going to be a handful of very motivated people who try to learn this stuff in their own way, but as an industry that can be diluted.

And I do think it’s very important to look at how that comes together in a place like Mexico, because Mexico has flourished in the relationship between government sponsorship in partnership with private investment. In the last few years, the government subsidies have been lost, and with great detriment because it creates a dichotomy. Part of the reason there’s such a healthy industry of workers in Mexico, and there are plenty of jobs, is precisely because of the generations that came through because of that government sponsorship.

DEL TORO: All I wish is that we can establish continuity to what has already been gained. Mexico and Mexican cinema, in its relationship to the world, is very prominent now. New filmmakers are being looked at with great hope, and a lot of new female directors especially are standing strong on the international stage from Mexico. The continuity of that generation is important.

As Alfonso said, it’s a dichotomy, because it’s a very good moment in some ways and a very difficult moment in others. It’s not an industry that was subsidized out of capricious decisions; it was subsidized because it was not protected in NAFTA [the North American Free Trade Agreement]. It was left completely unprotected by many of the big government moves. Other industries in Mexico were protected, but the cinema industry was left completely open. That’s why it requires a subsidy. It’s not capricious, it’s not about quality, it’s about it being left alone to fend for itself.

CUARÓN: That had proven to be an amazing investment from the government for the last few decades, and what you’re talking about—that continuity you’re talking about—is very important because Alejandro, Guillermo and I witnessed firsthand the hardship of the generation that came before us. A generation of amazing masters that the three of us owe such a debt to. They had to survive incredibly tough circumstances, and ever since that system was created, a new continuity

DEADLINE.COM/AWARDSLINE 31

was able to emerge. It is as much an industry continuity as a cultural continuity. And probably that, perhaps, would be the biggest argument in support of those incentives.

By the time Cuarón, del Toro and Iñárritu attended the Oscars in 2007, they had been dubbed the ‘Three Amigos’ and were years into their friendship. But their complicated relationship with success makes reminiscing about the decade and a half that followed tricky for them...

IÑÁRRITU: First of all, I want to mention that George Clooney stole our name, and he did a tequila [Casamigos], and frankly he should give us a little bit of a percentage [laughs]. We should have done that tequila, by the way. “The Three Amigos Tequila.” He was a wise guy, I think, Mr. George Clooney.

CUARÓN: [Laughs] Is this the section where we play “Reflections of My Life” by Marmalade as we look back?

DEL TORO: I look back on that time and I see three young guys. I see a lot of youth and I see three guys that believe in movies in the same way we believe in movies now. The adventure we’ve been on has not been lost on all of us, and I think we have only been able to survive success in the sense that we’ve embraced each other’s success with love, which is a very hard test for any friendship. We’ve been incredibly wise and loving with one another about failures and successes.

I’ve witnessed the deepening of Alejandro and Alfonso as people and as filmmakers. Filmmaking is a mysterious craft; a lot of people talk about film, and they don’t understand the actual mechanisms and syntax of how many hours and how much precision goes into the craft. There’s a mythology about film being something that just happens, but it’s something you will. It’s an accident that you must calculate with the help of hundreds of people to make happen. It’s a tribal birth. Every shot in a movie is a tribal birth that a director has had to orchestrate.

I have seen these guys’ craft deepen as much as their minds and souls have deepened, so when I look back, I see youth, I see lessons learned, I see the beauty of the scars. There’s a beauty to aging that I value a lot.

CUARÓN: And it’s a so-called success, because when we talk about any kind of success, it must coincide with different and specific moments in our lives. I think it’s been so beneficial to have this friendship with Guillermo and Alejandro endure because success is a double-edged sword. Depending on the time and moment you’re at in your life, you can be happy for the success of a friend because you know that in that specific

32 DEADLINE.COM/AWARDSLINE DEADLINE CONTENDERS PORTRAIT STUDIO/NETFLIX/DISNEY+/EVERETT COLLECTION

moment, he went through so much hardship. The added validation [of Oscar and critical success] is just the cherry on the cake.

As friends, you need each other to warn you to be careful of success. “This is great, and you’re enjoying these days and this moment, but remember it will end soon, and life will keep going on, so don’t invest too much in this perception of success.” If anything, the thing I remember most about those periods