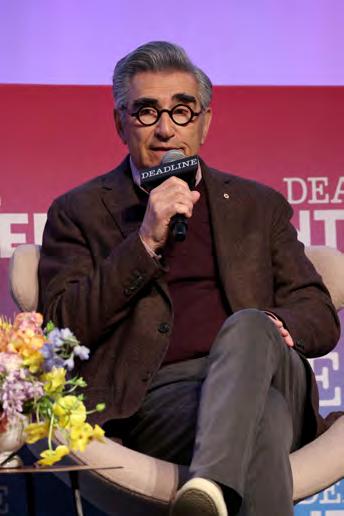

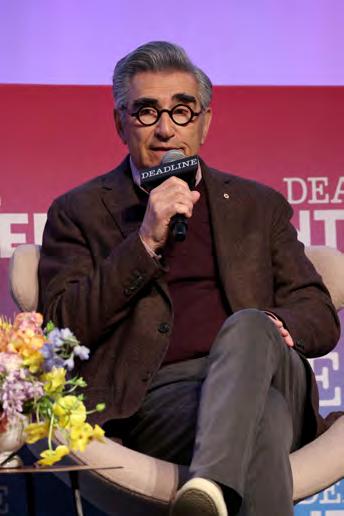

DEADLINE

DISRUPTORS

Our 2023 class of movers and shakers including:

QUINTA BRUNSON

It’s always funny in Philadelphia

LOUIS THEROUX

His docs don’t jiggle jiggle, they’re bold

EDWARD BERGER

Enjoying the spoils of war

IDRIS ELBA & MO ABUDU

Building a media empire from scratch

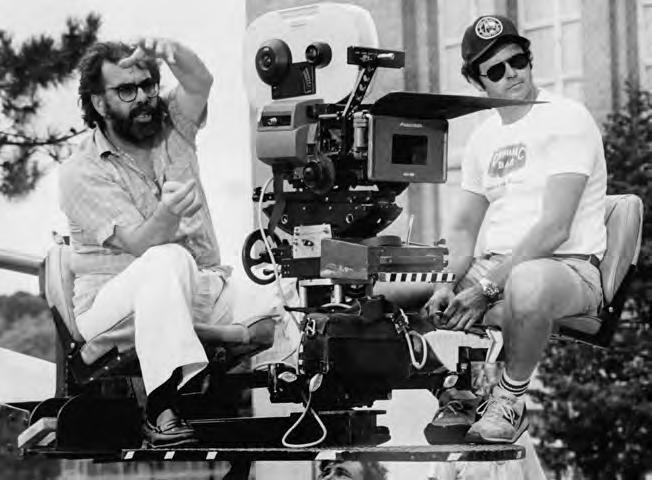

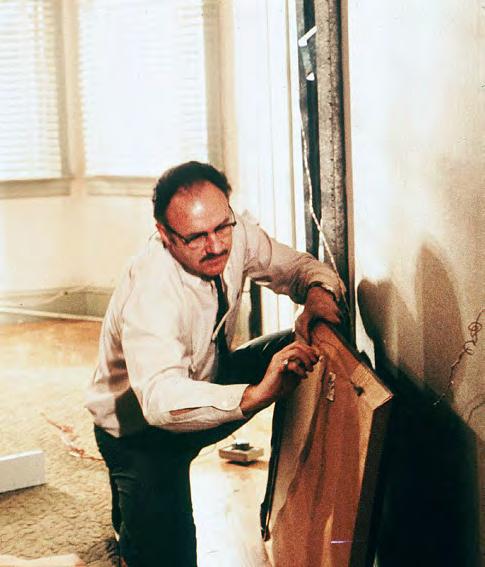

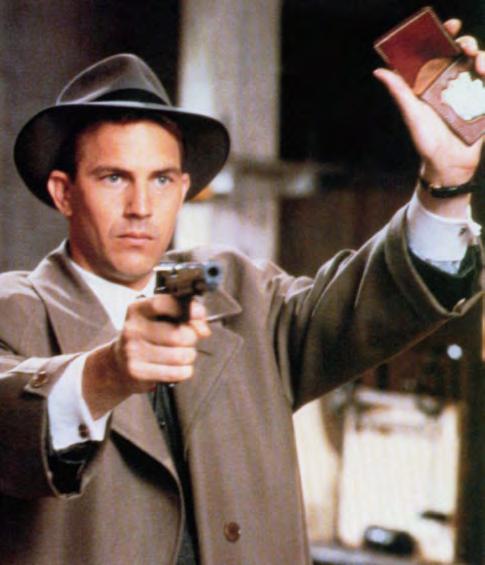

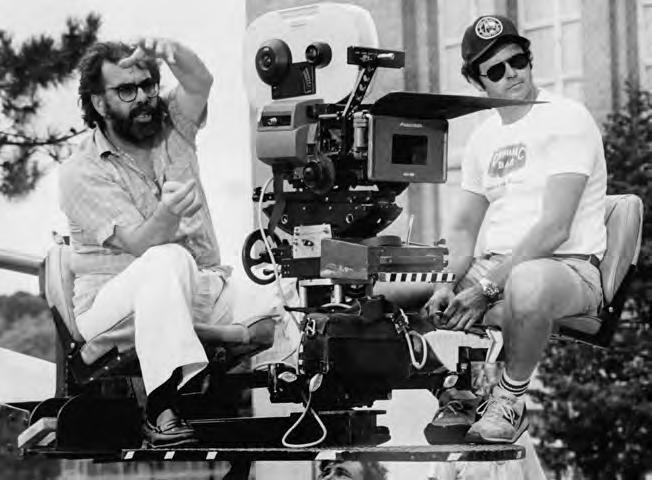

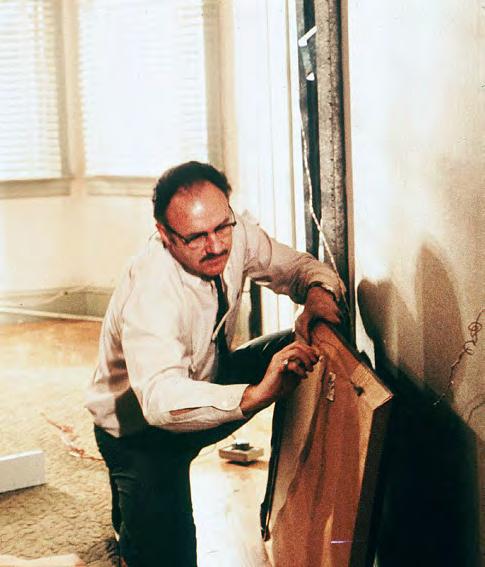

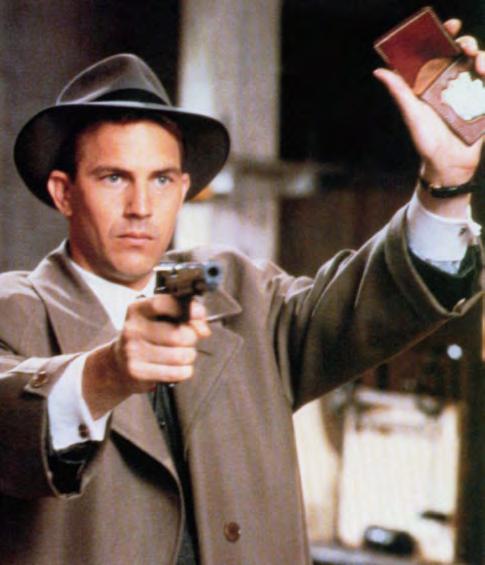

FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA & KEVIN COSTNER

How to make a DIY blockbuster

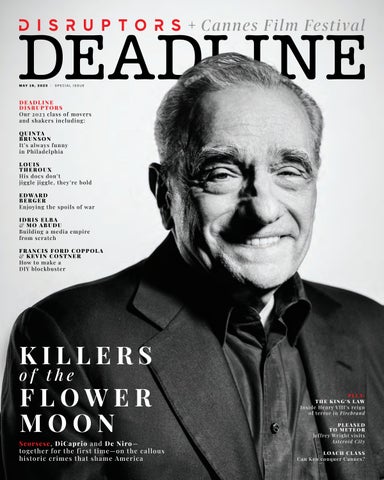

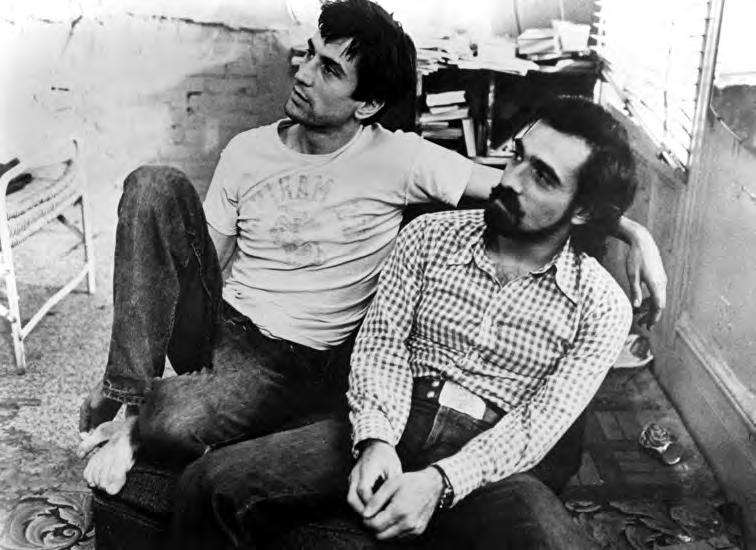

KILLERS of the FLOWER MOON

Scorsese , DiCaprio and De Niro together for the first time—on the callous historic crimes that shame America

MAY 16, 2023 | SPECIAL ISSUE

PLUS: THE KING’S LAW

Inside Henry VIII’s reign of terror in Firebrand PLEASED TO METEOR

Jeffrey Wright visits Asteroid City

LOACH CLASS Can Ken conquer Cannes?

PRESIDENT Stacey Farish

EXECUTIVE AWARDS EDITOR

Joe Utichi

VICE PRESIDENT, CREATIVE

Craig Edwards

SENIOR AWARDS EDITOR

Antonia Blyth

TELEVISION EDITOR

Lynette Rice

FILM EDITOR

Damon Wise

DOCUMENTARY EDITOR

Matthew Carey

CRAFTS EDITOR

Ryan Fleming

PRODUCTION EDITOR

David Morgan

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Destiny Jackson

DIRECTOR, SOCIAL MEDIA

Scott Shilstone

DIRECTOR, EVENTS

Sophie Hertz

DIRECTOR, BRAND MARKETING

Laureen O’Brien

EVENTS MANAGER

Allison DaQuila

VIDEO MANAGER

David Janove

VIDEO PRODUCERS

Benjamin Bloom

Jade Collins

Shane Whitaker

DESIGNERS

Catalina Castro

Grant Dehner

SOCIAL MEDIA COORDINATOR

Natalie Sitek

EVENTS COORDINATOR

Dena Nguyen

DESIGN/PRODUCTION COORDINATOR

Paige Petersen

CHIEF PHOTOGRAPHER

Michael Buckner

PUBLISHER

Kasey Champion

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, GLOBAL BUSINESS

DEVELOPMENT & STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS

Céline Rotterman

VICE PRESIDENT, ENTERTAINMENT

Caren Gibbens

VICE PRESIDENT, INTERNATIONAL SALES

Patricia Arescy

VICE PRESIDENT, SALES & EVENTS

Tracy Kain

SENIOR DIRECTOR, ENTERTAINMENT

Brianna Corrado

DIRECTOR, ENTERTAINMENT

London Sanders

DIRECTOR, DIGITAL SALES PLANNING

Letitia Buchan

ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE

Michael Bronstein

SENIOR DIGITAL ACCOUNT MANAGER

Cherise Williams

SALES PLANNER

Luke Licata

SALES ASSISTANT

Daryl Jeffery

PRODUCTION DIRECTOR

Natalie Longman

DISTRIBUTION DIRECTOR

Michael Petre

PRODUCTION MANAGER

Andrea Wynnyk

CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF

Nellie Andreeva (Television)

Mike Fleming Jr. (Film)

AWARDS COLUMNIST & CHIEF FILM CRITIC

Pete Hammond

COLUMNIST & INTERNATIONAL EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Baz Bamigboye

EXECUTIVE MANAGING EDITOR

Patrick Hipes

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR & BOX OFFICE EDITOR

Anthony D’Alessandro

SENIOR EDITOR, LEGAL & TV CRITIC

Dominic Patten

SENIOR MANAGING EDITOR

Denise Petski

MANAGING EDITOR

Erik Pedersen

DEPUTY MANAGING EDITOR

Tom Tapp

TELEVISION EDITOR

Peter White

INTERNATIONAL EDITOR

Andreas Wiseman

BUSINESS EDITOR

Dade Hayes

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Peter Bart

FILM CRITIC & COLUMNIST

Todd McCarthy

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

Michael Cieply

SENIOR FILM WRITER

Justin Kroll

CO-BUSINESS EDITOR

Jill Goldsmith

LABOR EDITOR

David Robb

POLITICAL EDITOR

Ted Johnson

INTERNATIONAL TELEVISION CO-EDITOR

Max Goldbart

INTERNATIONAL FEATURES EDITOR

Diana Lodderhose

INTERNATIONAL BOX OFFICE EDITOR & SENIOR CONTRIBUTOR

Nancy Tartaglione

INTERNATIONAL TELEVISION CO-EDITOR

Jesse Whittock

INTERNATIONAL INVESTIGATIONS EDITOR

Jake Kanter

ASSOCIATE EDITOR & FILM WRITER

Valerie Complex

BROADWAY AND NEW YORK NEWS EDITOR

Greg Evans

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Bruce Haring

CONTRIBUTING EDITOR, ASIA

Liz Shackleton

ASSOCIATE EDITOR, TV

Rosy Cordero

SENIOR INTERNATIONAL FILM CORRESPONDENT

Melanie Goodfellow

FILM REPORTER

Matt Grobar

INTERNATIONAL FILM REPORTER

Zac Ntim

TELEVISION REPORTER

Katie Campione

NIGHTS AND WEEKENDS EDITOR

Armando Tinoco

PHOTO EDITOR

Robert Lang

DEADLINE.COM

Breaking News Follow Deadline.com 24/7 for the latest breaking news in entertainment.

Sign up for Alerts & Newsletters

Sign up for breaking news alerts and other Deadline newsletters at: deadline.com/newsletters

VIDEO SERIES

The Actor’s Side

Meet some of the biggest and hardest working actors of today, who discuss their passion for their work in film and television. deadline.com/vcategory/ the-actors-side/

Behind the Lens

Explore the art and craft of directors from first-timers to veterans, and take a unique look into the world of filmmakers and their films. deadline.com/vcategory/ behind-the-lens/

The Film That Lit My Fuse

Get an insight into the creative ambitions, formative influences, and inspirations that fuelled today’s greatest screen artists.

deadline.com/vcategory/ the-film-that-lit-my-fuse/

PODCASTS

20 Questions on Deadline

Antonia Blyth gets personal with famous names from both film and television. deadline.com/tag/ 20-questions-podcast/

Scene 2 Seen Valerie Complex offers a platform for up-and-comers and established voices. deadline.com/tag/ scene-2-seen-podcast/

Crew Call

Anthony D’Alessandro focuses on the contenders in the below-the-line categories. deadline.com/tag/ crew-call-podcast/

CHAIRMAN & CEO

Jay Penske

VICE CHAIRMAN

Gerry Byrne

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER

George Grobar

CHIEF ACCOUNTING OFFICER

Sarlina See

CHIEF DIGITAL OFFICER

Craig Perreault

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, BUSINESS AFFAIRS & CHIEF LEGAL OFFICER

Todd Greene

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, OPERATIONS & FINANCE

Paul Rainey

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, OPERATIONS & FINANCE

Tom Finn

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCT & ENGINEERING

Jenny Connelly

MANAGING DIRECTOR, INTERNATIONAL MARKETS

Debashish Ghosh

EVP, GM OF STRATEGIC INDUSTRY GROUP

Dan Owen

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, SUBSCRIPTIONS

David Roberson

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, PROGRAMMATIC SALES

Jessica Kadden

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, DEPUTY GENERAL COUNSEL

Judith R. Margolin

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, FINANCE

Ken DelAlcazar

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, HUMAN RESOURCES

Lauren Utecht

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT

Marissa O’Hare

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, CREATIVE

Nelson Anderson

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, LICENSING & BRAND DEVELOPMENT

Rachel Terrace

VICE PRESIDENT, ASSOCIATE GENERAL COUNSEL

Adrian White

VICE PRESIDENT, HUMAN RESOURCES

Anne Doyle

VICE PRESIDENT, REVENUE OPERATIONS

Brian Levine

HEAD OF INDUSTRY, CPG AND HEALTH

Brian Vrabel

VICE PRESIDENT, PUBLIC AFFAIRS & STRATEGY

Brooke Jaffe

HEAD OF INDUSTRY, TECHNOLOGY

Cassy Hough

VICE PRESIDENT, SEO

Constance Ejuma

VICE PRESIDENT & ASSOCIATE GENERAL COUNSEL

Dan Feinberg

HEAD OF LIVE EVENT PARTNERSHIPS

Doug Bandes

VICE PRESIDENT, AUDIENCE MARKETING & SPECIAL PROJECTS

Ellen Deally

VICE PRESIDENT, GLOBAL TAX

Frank McCallick

VICE PRESIDENT, TECHNOLOGY

Gabriel Koen

VICE PRESIDENT, E-COMMERCE

Jamie Miles

HEAD OF INDUSTRY, TRAVEL

Jennifer Garber

VICE PRESIDENT, ACQUISITIONS & OPERATIONS

Jerry Ruiz

VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCTION OPERATIONS

Joni Antonacci

VICE PRESIDENT, FINANCE

Karen Reed

VICE PRESIDENT, BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT

Katrina Barlow

VICE PRESIDENT, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

Kay Swift

VICE PRESIDENT, HUMAN RESOURCES

Keir McMullen

HEAD OF AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY

Matthew Cline

SOCIAL MEDIA

Follow Deadline

Facebook.com/Deadline Instagram.com/Deadline Twitter.com/Deadline YouTube.com/Deadline TikTok.com/@Deadline

VICE PRESIDENT, STRATEGIC PLANNING & ACQUISITIONS

Mike Ye

VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCT DELIVERY

Nici Catton

VICE PRESIDENT, CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE & MARKETING OPERATIONS

Noemi Lazo

HEAD OF INDUSTRY, PERFORMANCE MARKETING

Scott Ginsberg

VICE PRESIDENT, ASSOCIATE GENERAL COUNSEL

Sonal Jain

DEADLINE

HOLLYWOOD IS OWNED AND PUBLISHED BY PENSKE MEDIA CORPORATION

First Take

Cover Story

Flash Mob

CALL SHEET

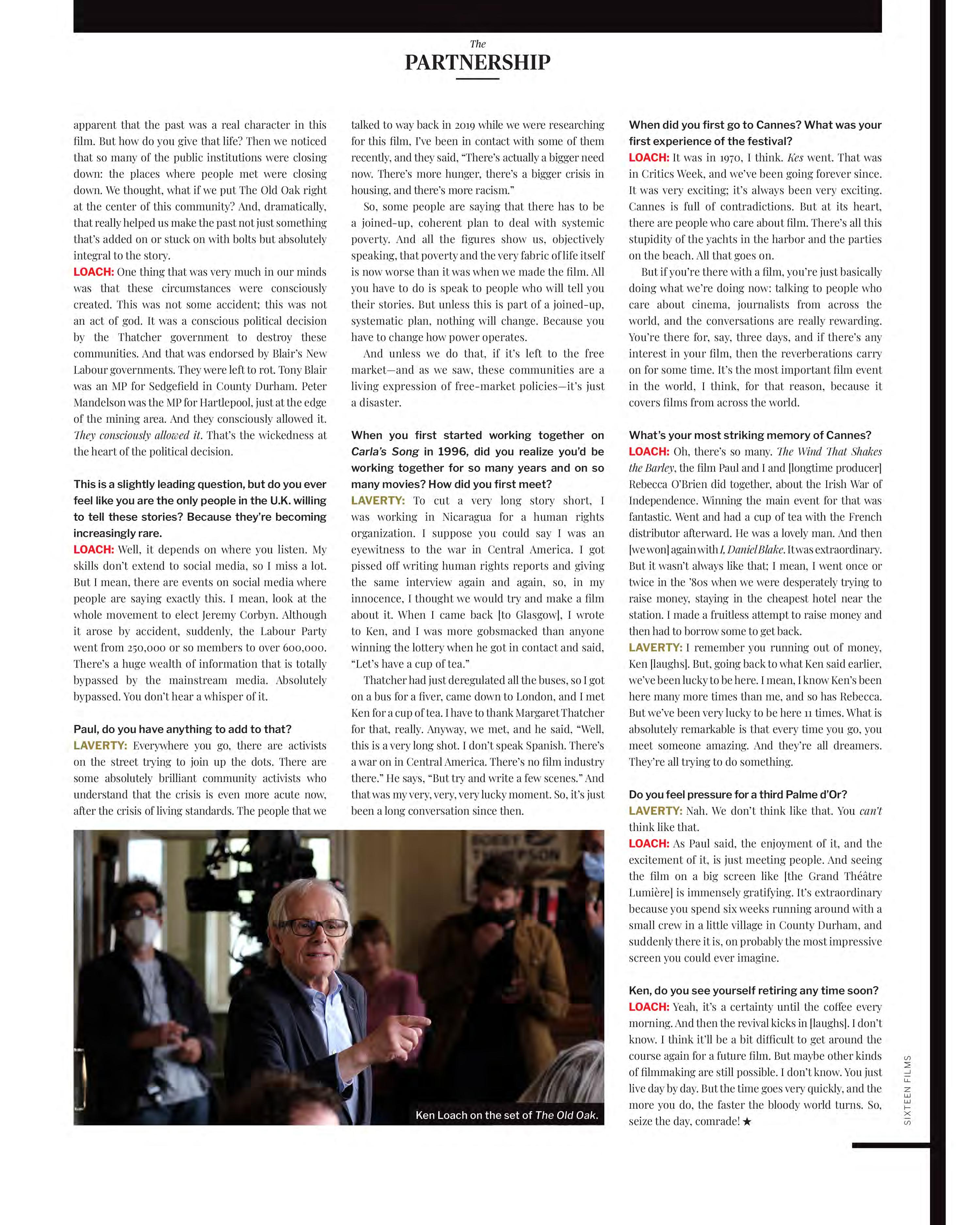

4 ONES TO WATCH: Five Cannes debutantes to keep an eye on. 10 FIREBRAND: Jude Law and Alicia Vikander in a historic matter of wife and death. 24 THE PARTNERSHIP: Ken Loach and Paul Laverty go for the triple with The Old Oak 30 JEAN-LUC GODARD: The untold story of his crazy assault on Shakespeare. Dialogue 12 Wim Wenders 18 Alice Rohrwacher 20 Jeffrey Wright

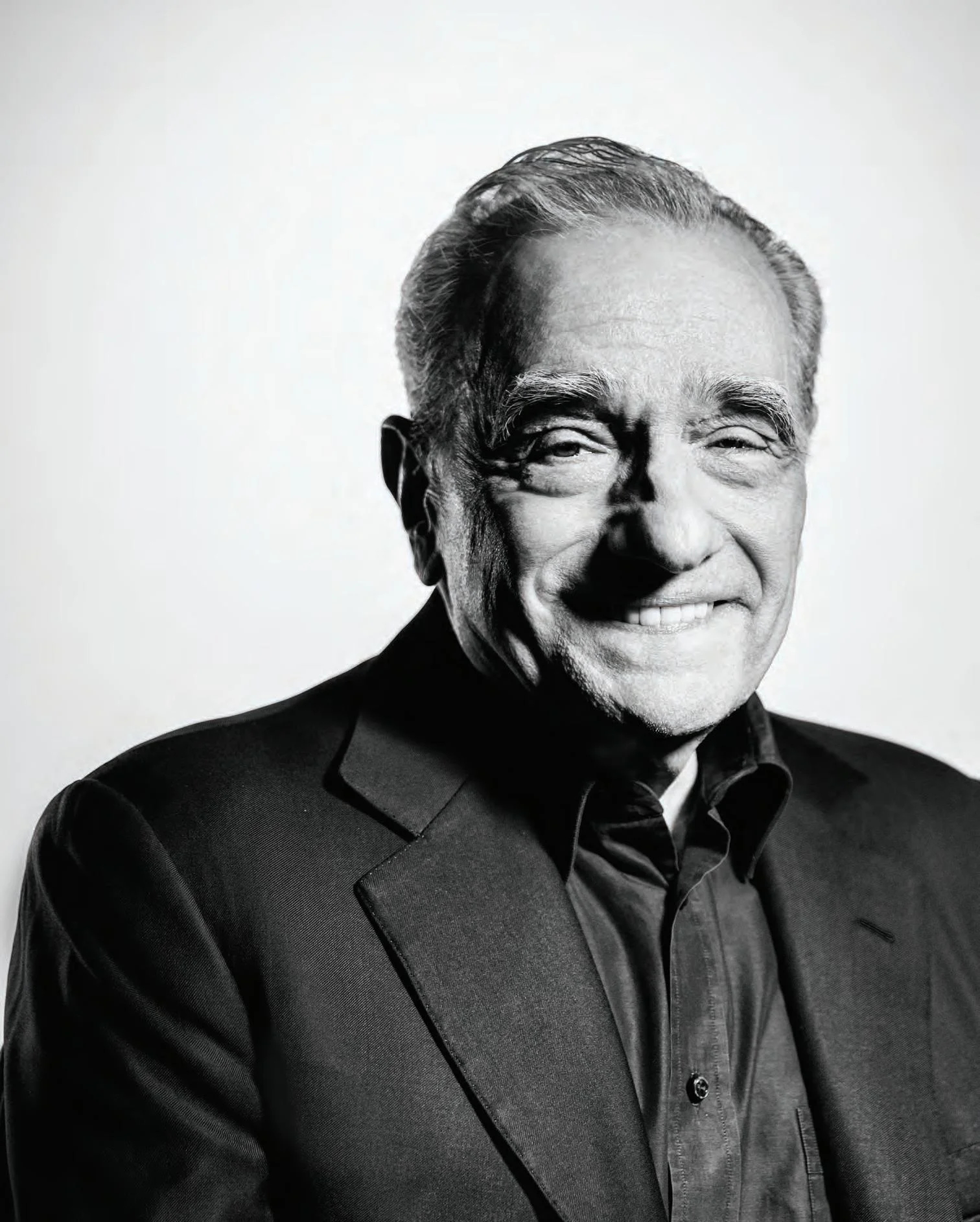

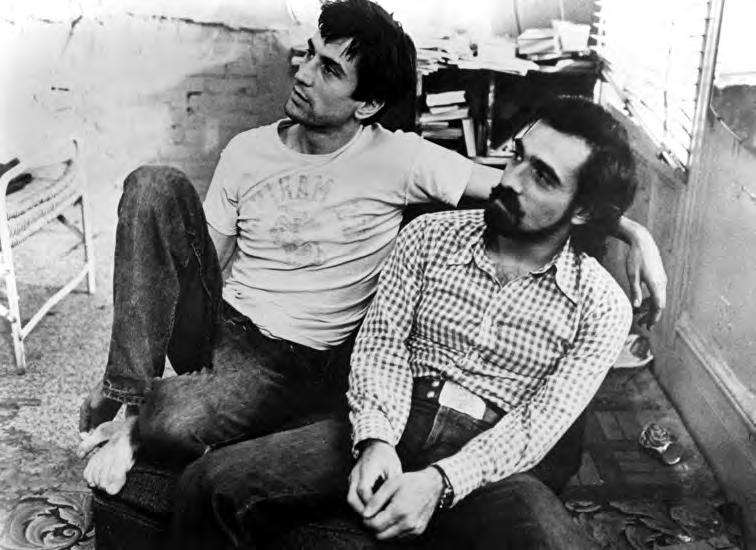

38 KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON: How David Grann’s 2017 truecrime bestseller became the year’s biggest movie thanks to Martin Scorsese and Co.

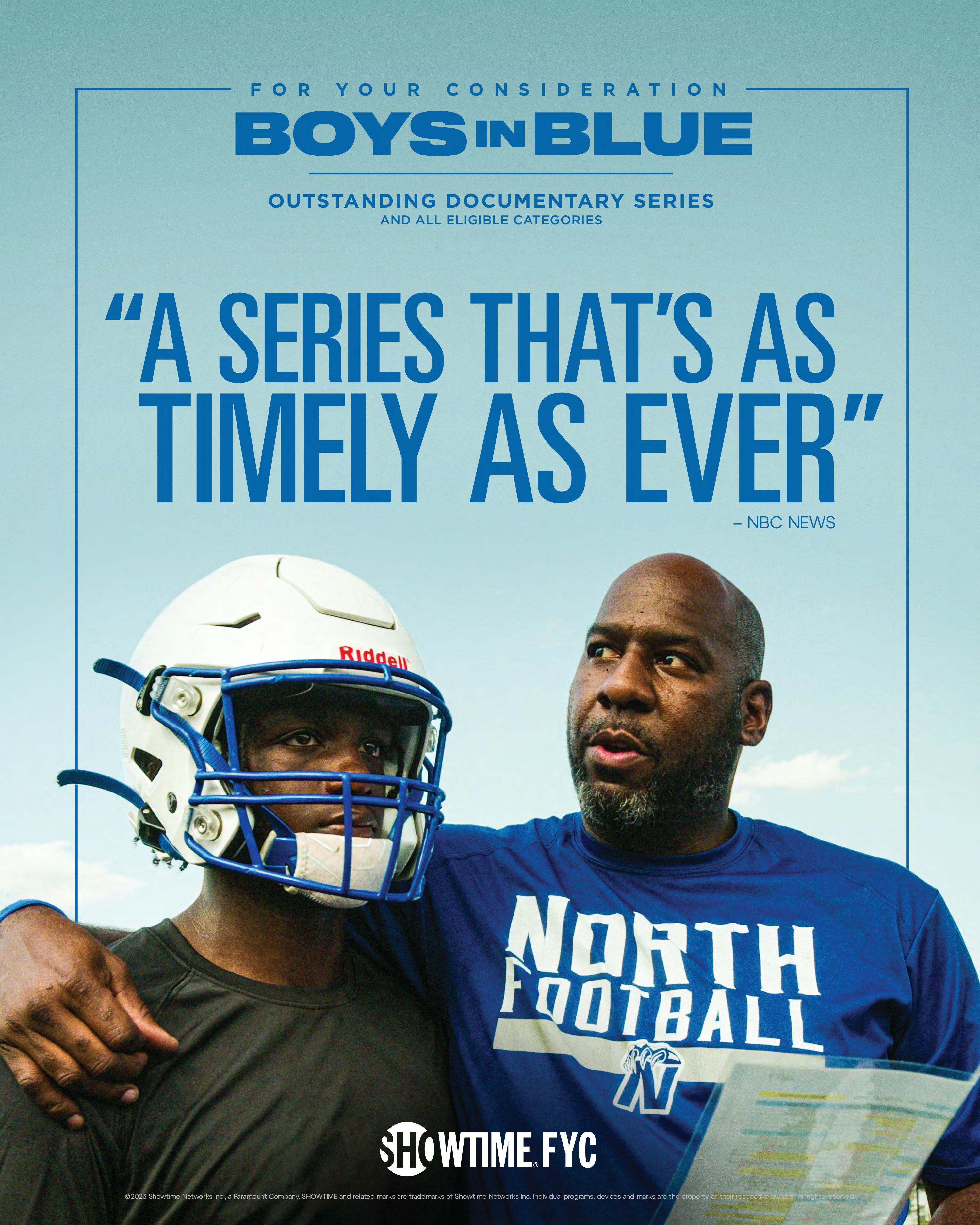

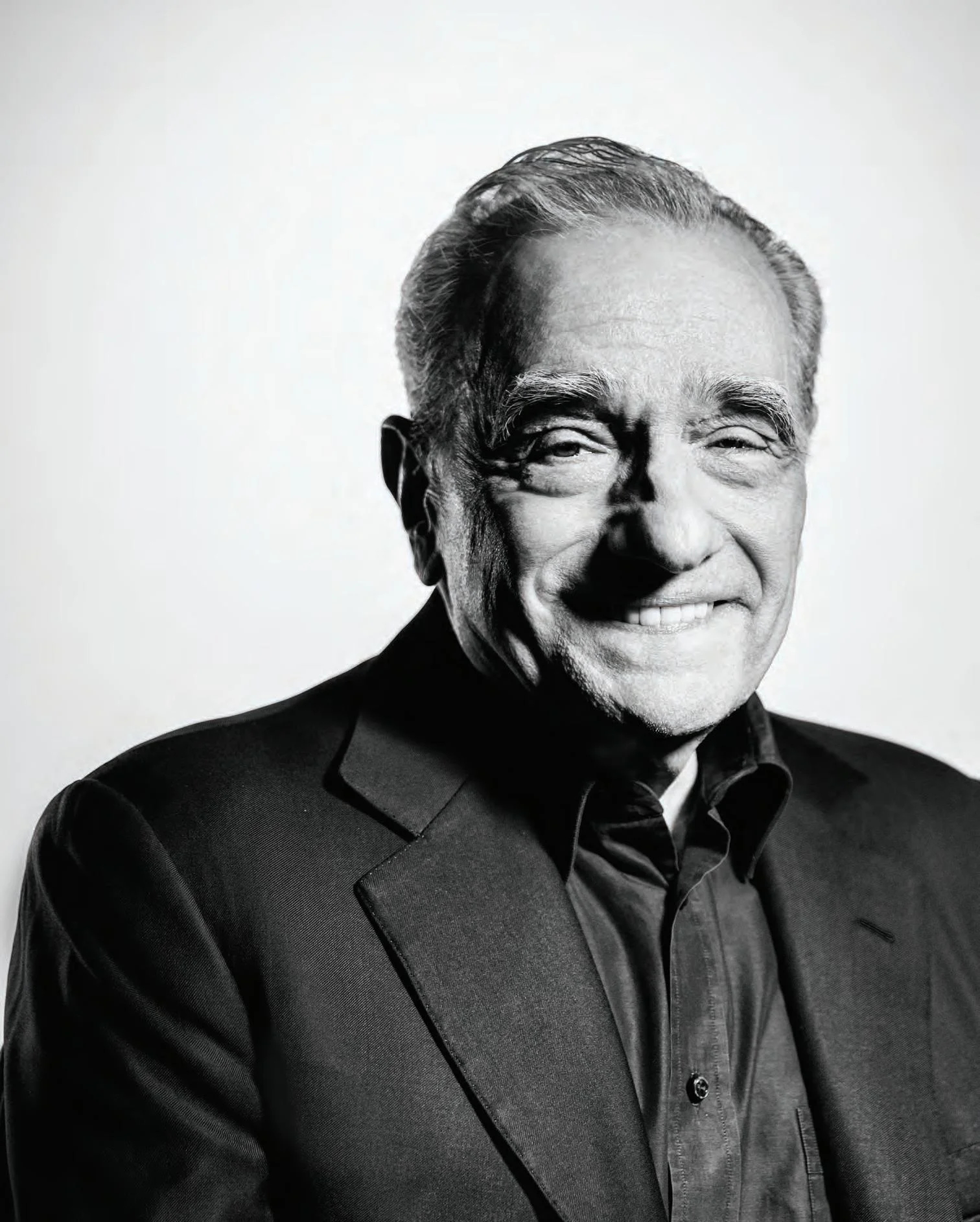

114 Shots from Contenders Television: Los Angeles. ON THE COVER: Martin Scorsese

Mann. THIS PAGE: Quinta Brunson

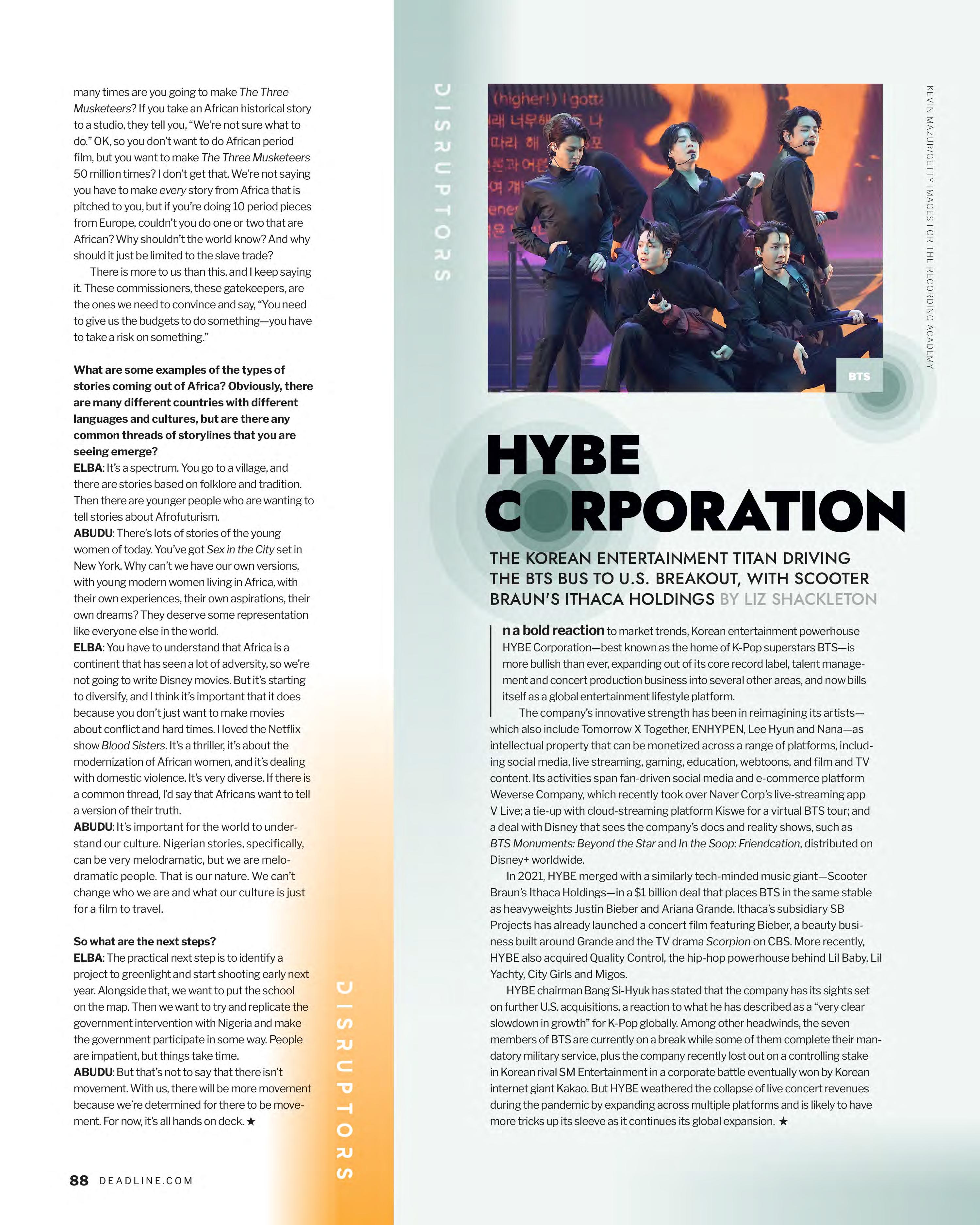

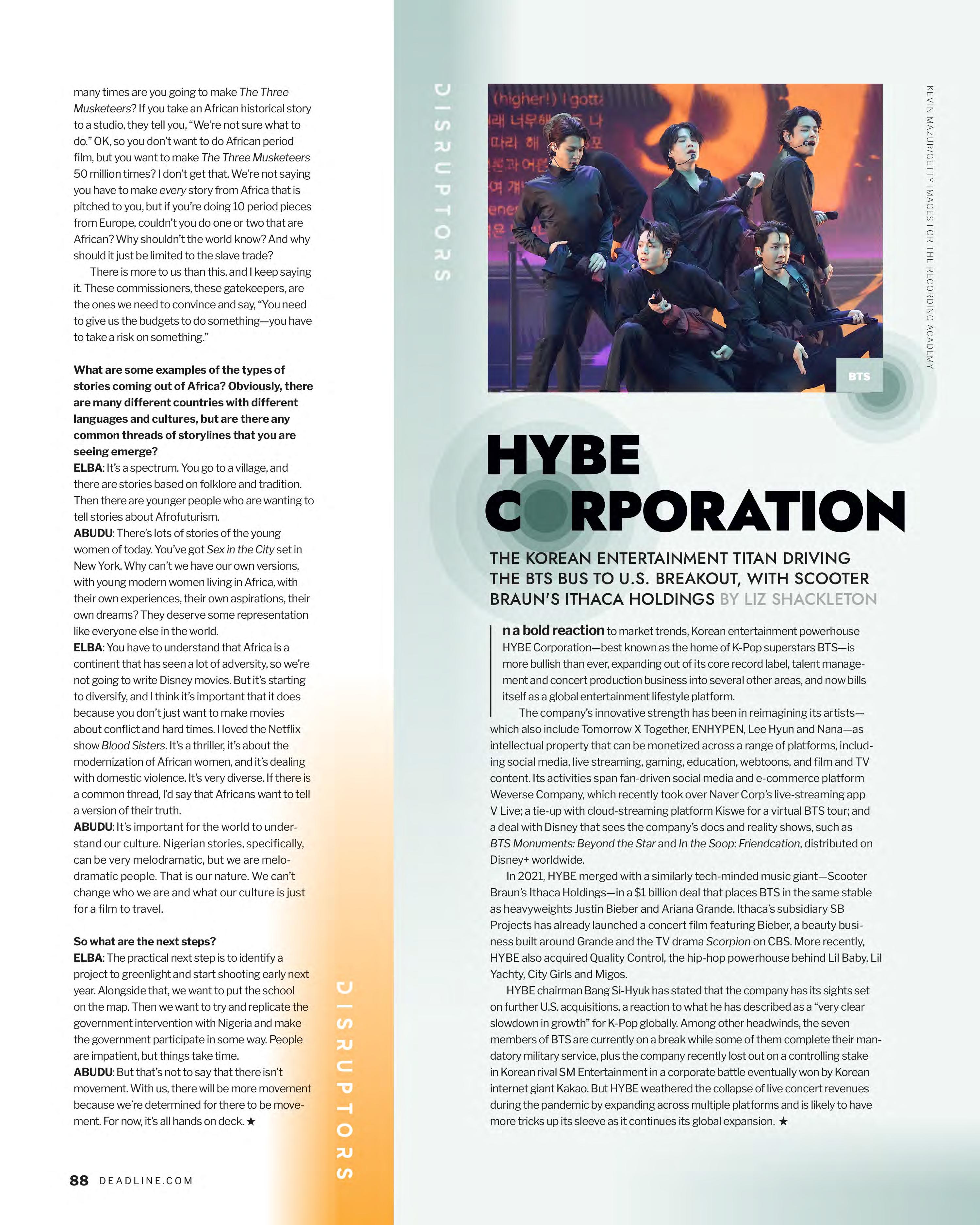

Quinta Brunson 62 YouTube Revolutionaries 70 Vision Entertainment 74 Word-of-Mouth Horror 75 Tollywood 76 Magnolia Network 80 Idris Elba & Mo Abudu 82 Hybe Corporation 88 Edward Berger 90 Iran Rebels 92 Mediawan 94 Louis Theroux 96 Digital Disruption 98 Francis Ford Coppola & Kevin Costner 102

photographed by Mark

photographed by Michael Buckner.

F T I A R K S E T

DEADLINE ANOINTS THE FIVE NAMES

DESTINED TO ROCK THIS YEAR’S CROSETTE

ONES TO WATCH

CANNES FILM FESTIVAL 2023

DEADLINE.COM PG. 4

GETTY IMAGES/RLJE FILMS/STEF BLOCH/EDDY CHEN/HBO

DEADLINE’S

LILY-ROSE DEPP

WILL THE IDOL STAR UPSTAGE HER FAMOUS FATHER ON THE CROISETTE THIS YEAR?

“When was the last truly fucking nasty, nasty, bad pop girl?” This is the question posed in the teaser trailer to HBO’s The Idol, which promises the kind of lurid, adrenaline-pumping pop-culture exposé you’d see if Paul Verhoeven was ever allowed to make a film like Showgirls again. Said trailer also features copious quantities of cocaine, champagne and seriously dirty dancing, suggesting a warts-and-all drama about a super ambitious Madonna/Lady Gaga type who has recently hit the big time in the dog-eat-dog world of showbiz.

That, in itself, would be a risky for role for any young actress, especially since The Idol has already been in the news for its turbulent production, overseen by director Sam Levinson, whose envelope-pushing series Euphoria was labelled “pointlessly gratuitous” by the hardly conservative Esquire magazine. Hats off, then, to Lily-Rose Depp—daughter of Johnny and French pop singer Vanessa Paradis, and goddaughter of the controversy-besieged goth rocker Marilyn Manson—for braving the role of Jocelyn, a singer on the rebound who falls under the influence of shady nightclub impresario Tedros (Abel Tesfaye, AKA The Weeknd).

Though she’s still only 23, Depp went into acting nearly a decade ago, when she made her debut alongside Kevin Smith’s daughter Harley Quinn in Smith’s Tusk, an orgy of nepotism that must have seen the recent ‘nepo baby’ witch hunt coming. The pair reteamed in another Smith movie, Yoga Hosers (2016), another horror-comedy, in which they played convenience store clerks attacked by occult Nazi sausages. It was both a commercial flop and, to damn it with faint praise, Smith’s best film in 10 years.

Somehow, Depp’s acting career has gone under the radar so far, despite roles alongside names like Timothée Chalamet in The King (2019) and Keira Knightley in Silent Night (2021). With a high-profile project like The Idol, which follows prestige serial TV such as Twin Peaks: The Return (2017) and Irma Vep (2022) into the official Cannes lineup, Depp will have to navigate her own life as a screen idol pretty quickly, a status she’s already given thought to. “People want you to be larger than life and somebody that they can aspire to be like or look up to,” she has said, “but also relatable enough to make them feel comfortable.”

To play the part of Jocelyn, Depp went further than asking her parents what life was like in the ’90s, which, on reflection, might have saved everyone a lot of time.

“I thought about movie stars of the ’40s, like Lauren Bacall and Gene Tierney,” she said. “They didn’t walk into a room and descend to anybody else’s level to try and make them feel comfortable. They almost had this confidence in the discomfort that they could provoke in people. A thing of, ‘This is who I am, and I’m not going to change.’”

The elephant in the room, of course, is the very public fall from grace of Depp Sr.—star of opening night film Jeanne du Barry—whose notorious libel trial made never-ending headlines last year. Asked by Vice about the blessing/curse of celebrity parentage, Depp showed an encouraging level of self-awareness. “I feel like my parents did the best job that they possibly could at giving me the most ‘normal childhood’ that they could,” she said. “And obviously, that still was not a normal childhood. I’m really lucky that I’ve been surrounded by people who value normalcy and who value real life, and I think that’s the only way to exist in this world and not go insane.” —Damon Wise

ANNUAL GROUP OF ONES TO WATCH IN CANNES IS MADE UP OF ACTORS AND FILMMAKERS WHO ARE ALL BRINGING SOMETHING FRESH TO THE FESTIVAL. THE DISTINCTION ISN’T ALWAYS RESERVED FOR BRAND NEW FACES; RATHER, WE’VE SELECTED PEOPLE WHO ARE BRANCHING OUT, OR WHO FIND THEMSELVES IN WATERS WHERE THEY ARE LIABLE TO MAKE WAVES. CANNES CAN BE A PLACE OF REINVENTION, AFTER ALL.

2023 FILM FESTIVAL CANNES

IDOL

THE

JOANNA ARNOW

THE PROVOCATIVE BROOKLYN SHORTS DIRECTOR MAKES HER FEATURE DEBUT

You know an artist must be doing something special when even Andrew Bujalski, the godfather of mumblecore, calls their work “excruciating and extraordinary”. But this is where Brooklyn-based director and comic-book writer Joanna Arnow is right now, after a string of darkly funny shorts that might be said to combine the sexual candor of early Chantal Akerman with the sardonic humor of Todd Solondz. Cannes audiences, then, must brace themselves for her feature debut, The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed, which premieres in the Quinzaine and which she describes as “a mosaic-style comedy following the life of a woman as time passes in her long-term casual BDSM relationship, lowlevel corporate job, and quarrelsome Jewish family.”

Surprisingly—or perhaps not, given the genesis of her bestknown film I Hate Myself, a documentary that started to take a new direction when a bitter row with a boyfriend was accidentally recorded—Arnow was expecting to debut with a different movie. “But my previous project had gotten delayed,” she says, “and I needed to feel artistically engaged with something new.” Similarly, she hadn’t always planned to be a director. “I wanted to be an actor when I was growing up, but in college I was too nervous to audition. I didn’t quite know what to do after giving up in a big way, until I was blown away by a history of world cinema class and decided to divert my interests into film.”

As someone who thinks she shares “a lot” with George Costanza in Seinfeld, Arnow is both thrilled and terrified to debut in Cannes. “I hope people think it’s funny, and that they will relate to the absurd humor of a character figuring out how to be. I’m overjoyed the film is screening at Cannes and grateful to be included in such an amazing lineup. I’ve been trying to make a first feature for the past eight years, and I never expected something like this would be at the end of the road.”

—Damon Wise

MOLLY MANNING WALKER THE FIRST-TIME BRITISH DIRECTOR EXPLAINS HOW TO HAVE SEX?

They say you always remember the first time, but Molly Manning Walker’s Cannes debut, in the shorts section of Directors’ Fortnight, only happened in theory, after the pandemic closed down the festival. “It’s weird but I’ve never seen a film I’ve made in a cinema,” she says. “Both of my other shorts came out in the pandemic, then Good Thanks, You? premiered at Cannes, but only virtually, which was heartbreaking. So, it will be great to be at Cannes and experience it in full force.”

Happily, not only is Walker back, she’s in Un Certain Regard no less, with her first feature, How to Have Sex? “It follows a group of teenage girls during a rite of passage post-exam holiday in a party town in the Mediterranean,” she explains. “It looks at how we learn to have sex through the pressure of friendship, toxic masculinity and societal expectations. It’s a ride through the highs and lows of intimate female friendship.”

As you might expect, the story is drawn from the filmmaker’s own experiences. “As a teenager I enjoyed many party holidays but I hadn’t thought about the impact it had had on my perception of sex,” she explains. “I have a very distinct memory of a bar crawl where I saw a blowjob on stage. I wanted to talk about how we are introduced to sex. Especially people who have experienced these clubbing holidays. Most women I know have experienced some form of sexual assault, and I think this needs to be talked about. There is obviously a gap in education around the topic of consent. I hope the film will start a bigger conversation around the topic of consent; it would be amazing to reframe the conversation around how to have positive sexual experiences.”

Expectations are high for the film, since Walker is already established as a talented DP—her most recent work can be seen in Charlotte Regan’s charming Sundance entry Scrapper. And there are no signs that How to Have Sex? will be a one-off. “For me, cinema can take you on a rollercoaster of emotions. It’s all-encompassing. For the duration of the film, you have to surrender to the filmmaker. Real life really inspires me, I’m forever writing down stuff that people say in the street. To me, reality is so much better than fiction and when you can capture the madness of life on screen, that’s magic.” —Damon Wise

6 DEADLINE.COM

2023 FILM FESTIVAL CANNES FT CANNES ONES TO WATCH ODD ANDERSEN/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES/COURTESY MOLLY MANNING WALKER

RAMATA-TOULAYE SY

THE FIRST-TIME DIRECTOR REFLECTS ON HER ANCESTRY IN COMPETITION ENTRY

Senegalese and French director Ramata-Toulaye Sy is only the second Black woman to make it into Competition in Cannes. Her debut feature, Banel & Adama , follows in the footsteps of Mati Diop’s 2019 Atlantics . The screenwriter and director draws on her roots in the Fulani, or Peul, culture of the Futa region in northern Senegal for her magic-realist film about a young couple whose passion brings chaos to their remote rural community. “The people of Futa have the reputation of being very dignified and sticking to their community,” says Sy, who was born and grew up in France. “I was raised in the Fulani tradition at home and French culture outside.”

Inspiration for Banel & Adama came from a desire to create a tragic African heroine on par with Pierre Corneille’s Médée or Jean Racine’s Phèdre. “We don’t really have these mythical, tragic characters, or we do, but very few,” says Sy, who wrote the screenplay as her graduation work for the French film school La Fémis, where she studied screenwriting.

“I didn’t want to direct. Literature and writing are my passion,” she says, citing her favorite authors as Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Jesmyn Ward, as well as William Faulkner. But tragedy pushed Sy into the director’s chair after French producer Éric Névé, who had acquired the screenplay and was trying to get the project off the ground, died suddenly in 2019. “He was my godfather in the cinema world. His wife, Maud Leclair, said, ‘You need to do this for Eric,’ and so I did it for him as an homage.”

Mixing 17th Century literary influences with Senegalese storytelling traditions, Sy describes her film as “a patchwork” representing different parts of her identity. “Yes, I was born in France, and I am culturally French, but I am above all African because I am Black and my parents come from Senegal. I also consider myself a French cineaste.”

STÉPHAN CASTANG

THE DIRECTOR OF VINCENT MUST DIE PROVES THE ZOMBIE MOVIE IS UNALIVE AND KICKING

In an early scene of French director Stéphan Castang’s Cannes Critics’ Week entry Vincent Must Die, a colleague of the film’s titular protagonist whacks him around the head with his laptop. A little later, another workmate stabs him in the arm. “He’s just an average guy who wakes up one morning to discover that everyone wants to kill him,” Castang explains. The debut feature follows in the wake of Julia Ducournau’s Raw and Just Philippot’s The Swarm as French genre titles to be championed by the first and second film-focused Critics’ Week.

Castang came late to film directing after spending two decades working as a theatre actor. “I always wanted to write and direct films but then I took a very long detour,” he says. He finally started exploring filmmaking with a short film, French Kids—in which a group of rebellious high school students react to an aggressive guidance counsellor—that played in the Generation 14plus section of Berlin in 2012. Subsequent shorts include the 2050-set sci-fi Panthéon Discount, set in a world where doctors have been replaced by a super-scanner that diagnoses ailments and treats them on the basis of the patient’s bank balance, and the octogenarian love-triangle tale Finale.

Vincent Must Die is one of the first projects to come to fruition for Wild West, the joint Blumhouse-style venture created by Thierry Lounas’ French film company Capricci and Goodfellas (ex-Wild Bunch International) in 2021 to develop and produce French genre cinema. The screenplay by Mathieu Naert was originally developed in Capricci’s So Film Genre Screenwriting Lab, which laid the foundations for the creation of Wild West.

“I was a script consultant on the residency but on another project,” says Castang. “Thierry asked me to look at the script and whether I would be interested in directing it. Initially, I wasn’t too keen, as I like to write my own films, but when I read it, I felt a complicity. There was something in it that chimed with my own neurosis. I felt I could find a place for myself in the story. I also like the way it mixed lots of genres. It’s not locked in absolute genre codes, it’s a love story with a sort of zombie angle as well.” —Melanie

Goodfellow

But beyond questions of origin and identity, Sy’s biggest hope for the film is that it will have universal appeal. “I want all women to recognize themselves in the character of Banel, in the same way there are universal films set in the United States, in which I recognize myself even if they’re American characters,” she says. “We need to do the same thing out of Africa. Just because a film is African with Black characters, it doesn’t mean white spectators can’t recognize themselves in those films, in the same way we recognize ourselves in films where the characters are predominantly white.” —Melanie

Goodfellow

8 DEADLINE.COM

BANEL & ADAMA

2023 FILM FESTIVAL CANNES

FT CANNES ONES TO WATCH CAMILLE DAMPIERRE/ASTOU FILMS

BANEL & ADAMA

HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIOUS KILLER

Alicia Vikander stands up to a fearless Jude Law in Firebrand, Karim Aïnouz’s unvarnished look at Henry VIII’s last marriage

ByBazBamigboye

ByBazBamigboye

It’s a solemn command from Firebrand’s first assistant director Lydia Carrie: “When you bow to the king, bow straight down,” she announces. “Don’t look at him; you’ll get your head cut off.” The fearsome monarch Carrie is referring to is Henry VIII, and on this particular day, Jude Law’s king is in an ax-swinging mood. The background artists on Karim Aïnouz’s set comply to orders and stare down at their toes. Before them, seated on thrones arranged on a raised plinth, is the potentate in question, and Katherine Parr, his queen.

Henry’s had a few wives. Katherine is his sixth and every time she opens her mouth, she’s in mortal danger. How does she survive? That’s the burning question asked by Firebrand, which Aïnouz describes as a

“psychological thriller”. History tells us that Parr outlived her husband, but little is known about Parr after that, though she was the first woman in England to have a book published in her own name.

Katherine was a smart woman who had to strategize in order to keep her head on her shoulders, says Alicia Vikander, the Academy Award-winning actress playing Parr. She knew exactly what she had to do “to live with a man who is like a beast” and “she needs to read him, constantly.”

Firebrand’s set today is the ancient Haddon Hall, built with local Derbyshire, England sandstone thick enough to retain 900 years’ worth of secrets within its walls. Aïnouz accompanies Vikander, wearing a grey tracksuit,

to the Hall’s gardens to go through the scene planned for the day’s shoot: It’s to be a Maypole dance to welcome in the spring.

A corpulent person soon appears, bedecked in a bejeweled coat with a fox-head fur wrapped over his shoulders. “It has to be real otherwise it looks like teddy bears,” says costume designer Michael O’Connor. Before PETA becomes involved, he quickly adds, “They’re old cut-up fur coats, so they’re sustainable.”

The man with the wide girth continues toward the filmmaker and the actress. He’s having trouble with his legs and the walk is more of a wobble. It’s before 9 a.m. and a visitor wonders if the mystery man with whiskers on his square-jawed face is Law’s stand-in.

“It’s Jude,” Firebrand producer Gabrielle Tana says matter-of-factly. “There’s Alicia in her civvies. They’re all here to rehearse. That’s Karim’s process.”

Law fills the throne as he sits. White stockinged legs protrude from ruby-red robes. He stares at Vikander, who by now has partnered with Sam Riley, playing the cowardly courtier Thomas Seymour. They bow, heads down, then dance. Vikander, who studied ballet when she was younger, moves delicately as Karim and Law look on.

Law shifts his padded frame. He was up with the larks to be dressed in specially made undergarments of the period. “No zips and buttons,” says O’Connor, noting that Law’s undies had to be tied up with silk ribbons.

Such an endeavor signified immense wealth. “You couldn’t possibly dress yourself,” O’Connor scoffs. “Only those highborn and with money could afford to have an army of dressers to get you ready in the morning.”

Aïnouz wanted to work with O’Connor because of the costumes he created for Francis Lee’s Ammonite. The filmmaker asked O’Connor how they could make “Ammonite on this film, in terms of spareness, stripping it down.”

“I said: ‘Well, she’s scrabbling around for dinosaur poo on the South Coast, and this is the court of Henry VIII, so they’re not really related to each other.’ But he wanted to get into what happens behind closed doors. It’s about how to transpose his style onto this subject. He wanted to coarsen it up a bit,” says O’Connor, though there is some splendor.

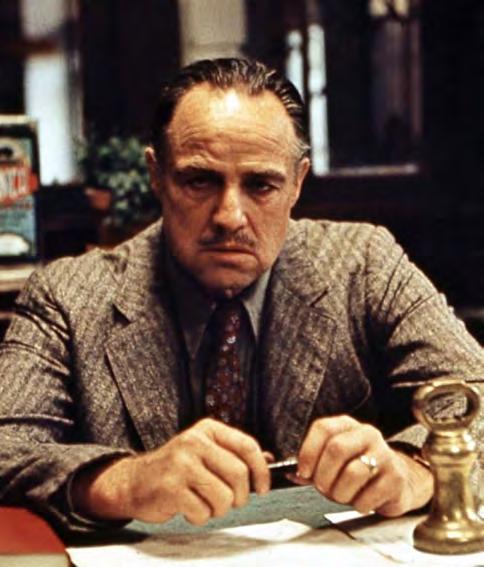

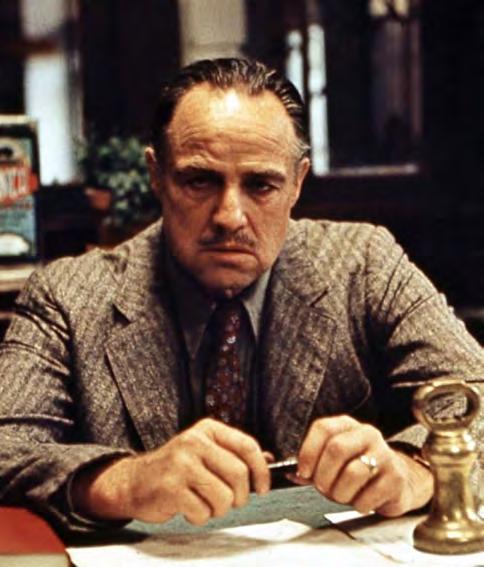

Only thespians portraying powerful sovereigns in a major movie can wallow in such trappings nowadays. So it was that O’Connor and his team were up early to kit out Law in a full padded body suit and then dress him in finery before turning him over to Oscar-winning makeup and hair designer Jenny Shircore to pad his cheeks, Marlon Brando Godfather style, and attend to his coiffure.

Shircore has been on almost intimate terms with Law’s torso; painting it with makeup and measuring his padded posterior to ensure the

10 DEADLINE.COM

LARRY D.

ENTERTAINMENT

2023 FILM FESTIVAL CANNES

HORRICKS/BROUHAHA

FT FEATURE

From left: Eddie Marsan, Alicia Vikander and director Karim Aïnouz.

buttocks tallied with someone else’s bare bottom, to use as a stand-in for a scene involving a horrifying sexual assault on Parr.

Tana admits that “a lot of actors were scared” of this Henry VIII. “He’s a murderer, a butcher,” she says.

“They didn’t want to have to go through that physical transformation, and all they could think about was that Hans Holbein portrait of Henry as this very stout, big thing,” she says. “They couldn’t get that out of their mind. There’s something very dark about that period and this Henry. But Jude relishes this, and he has totally embraced it.”

One of Aïnouz’s edicts is that on the set nobody talks to the actors except him. “So on the set, Jude is Henry,” Tana tells us.

She understands it. “It’s about protecting those characters. When they’re on the set that’s who they are. It’s his interactions with the actors and those interactions are sacrosanct,” Tana says. “He’s the director, he’s the auteur. They’re discovering their characters as they’re playing them.”

Aïnouz, too. Born to a Brazilian mother and an Algerian father who met at graduate school in the U.S., British medieval history hadn’t been on his curriculum growing up in Brazil. “Karim didn’t even know who Henry VIII was until I gave him the screenplay,” Tana says, which is why she wanted him to direct Firebrand She wanted a filmmaker who could look at other peoples’ stories “from the outside”.

Tana knew this from watching the heartwrenching betrayals explored in his films such as Futuro Beach and The Invisible Life, a success at Cannes in Un Certain Regard.

Tana notes how some British period films “fall into the same old tropes.” She says, “Karim doesn’t countenance tropes, but delights in all the things that are about the period.”

Like what? “In a way, the horrors of it,” she

says with alarm. “It’s not romanticized, it’s a fascinating portrait of a horrible marriage. There was no way out of it for her. ”

And Aïnouz has been absorbed with the historical medical details relating to Henry’s painful venous leg ulcers. “The maggots, the leeches and all of that,” that physicians of the day applied when they opened the wounds to drain and air them, Tana says.

Shircore consulted with surgeons about venous ulcers so she could contract FX designers to build leg wounds oozing with a variety of matter that slithers and apply them to Law’s legs. “It’s all down to Jude,” Shircore says. “He knows what he wants. He knew he could achieve it.”

As with Aïnouz, Vikander came to Parr from an outsider’s perspective, though she confesses to a certain “unsaid pressure” in portraying a royal character. But “Karim has taken an artistic freedom in telling quite an intimate story about a relationship,” she notes. “He shows quite a domestic version of what happened at court.”

There’s also a coarseness in the court that Aïnouz puts on display at Haddon Hall. “We’ve really tried to strip down the costume drama,” Vikander says.

Although the great state rooms, minstrels’ gallery and the acres of terraced gardens are splendid to behold, they’re not as grand as the palaces down south. “We are not in the main castle of London,” Vikander explains, “because, and this was accurate during the time, the court has to escape the plague, so this is set much smaller. It’s like when the royal court goes camping for a while.”

Vikander studied Parr’s own writings to help get a sense of Parr’s life. “For me, it was a lot of trying to get in the head of this woman and to understand her faith in God. The question of not having faith almost didn’t exist.” Parr’s words helped give Vikander a realization. “Not

only of Katherine, but of how women at that time lived and how they really came second. They were such a low-tier citizen.”

Vikander couldn’t comprehend how Parr could write long essays and poems about her fantastic husband, “And yet, at certain points of her life, he wants her dead. She’s in this very unhealthy and abusive relationship, but at some level it also needs to be functioning, and she was considered a good wife. I think it’s interesting to think about women in general, at whatever generation or time you’re in, you need to survive, so you also need to find your place in this reality and to find a way for you to not fully succumb to the tragedy that you are in.”

The stance Parr took often worked in her favor. Henry admired her intelligence to such an extent that he made her regent when he went with his army to France. “We really do play with the idea that she had quite a lot of influence on him,” she says.

We’re sitting in an outbuilding that has been turned into her green room, which she has brightened up with flowers.

The talk then turns to monsters. The ones who run the world now and how they relate to monsters in the past. “Henry was a monster and there are dictators like him living now,” she says, without identifying the 21st century culprits. Her question is, how would you survive? “How would a woman survive,” she corrects herself. “What would you say and how would you behave?”

A look back at Henry’s six wives suggests that history doesn’t really focus on the survivors. You don’t hear so much about Catherine of Aragon and Anne of Cleves, whom he divorced, but everyone remembers Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, who were executed, and Jane Seymour, who died shortly after childbirth.

“Isn’t that sad?” says Vikander. “They’re only interested in the women if they’re dead.” A

2023 FILM FESTIVAL CANNES DEADLINE.COM 11

Alicia Vikander as Katherine Parr.

Wim WENDERS

With Anselm and Perfect Days , the German auteur comes to Cannes with a two-for-one offer

BY DAMON WISE

A A A A A

Wim Wenders could be the Bob Dylan of European cinema: always around, always the same, always different. Sometimes he’ll arrive in Cannes with a doc, like 2018’s Pope Francis: A Man of His Word, and sometimes he’ll come with a work of fiction, like his timeless 1984 Palme d’Or winner Paris, Texas. This year, he’s coming with one of each: Anselm, a 3D portrait of artist Anselm Kiefer, and Perfect Days, the story of a Tokyo toilet cleaner. Ironically, Wenders thought he’d have more time on his hands after the pandemic and moving on from being president of the European Film Academy. How wrong he was.

You have two films in Cannes. Which would you prefer to start with?

Let’s start with the one that was in the works longer. That would be Anselm,

which was shot all through the pandemic and took quite a bit longer.

You’ve become very prolific in terms of documentaries lately in

your career. What appeals to you about documentaries, and why Anselm Kiefer?

I feel that the field of documentaries is wide open and that you have the freedom to redefine it with each film.

I’ve explored it extensively, let’s say, from Buena Vista Social Club to Pina or The Salt of the Earth, and each time the result was an entirely different language. I love it when the subject invents its own form and prefer that to imposing a formula or method on a film beforehand. Then you not only discover a new world, but also the way to approach it from scratch. I’m convinced that audiences feel that energy and are taking part in a whole new adventure of discovery.

The idea for a film with Anselm Kiefer didn’t come out of the blue. I’ve known him for 30 years, and at the beginning of our relationship in the ’80s, we talked about making a film together. In the end, we didn’t do it because Anselm moved to France, and I eventually moved to America for quite a while. But I followed his

work ever since, and we still met every now and then, reminding each other of our old plan. And then, about three years ago, I visited him for the first time in his huge place in the South of France, Barjac, where he built a whole landscape of gallery houses, underground structures like crypts and tunnels, even a roofed amphitheater and an immense cityscape of crumbling towers. I had never seen anything like it. That’s when our film idea immediately imposed itself again, very powerfully. And soon afterward, we met again in his studio near Paris, in Croissy, where I also hadn’t been before. And that was really what clinched it. After seeing that studio and the work he was doing there, I said, “We shouldn’t wait any longer; let’s do it now.”

Is this a study of the person or the work?

[Laughs]. The man is truly an interesting character, quite wild and independent. I like him a lot, yes, but it’s his work that I was interested in. With Pina, too, I didn’t go into a biography of Pina Bausch, same with the Buena Vista Social Club guys. I am interested in the work, and this film is a “biography of his work”, so to speak. Anselm and I have a lot in common. We were born in the same year, 1945, he a bit before the end of the war, me a bit after that. We definitely share a lot of the history that so strongly appears in his work. The scope of his painterly world is tremendous. It includes history, not only the German one, the origins of our myths, just as well as religion, astronomy, alchemy, physics. The range of his explorations really knows no limits, and he’s just as well a poet and a scientist than a painter and sculptor.

How do you approach a documentary—is it the same as your

12 DEADLINE.COM

GETTY IMAGES

CA NNES FILM FES TIVAL

fiction narratives? Are you the same person behind the camera?

I’m the same person behind the camera, sure. It might sound a little cryptic, but I basically approach my documentaries as if they were fiction films, and I like to approach my fictional films as if they were documentaries. I try to be fluid and to not be preconceived. Fiction thrives on an injection of reality, and the documentary form loves to include fictional elements. In a documentary, you try to find a thread, something that leads you through it, so you’re almost in search of a story. While in a fiction film, I enjoy the freedom that can come in when elements of reality enter it.

Has the technology changed since you did Pina? That’s a fair while ago. Is it easier to shoot in 3D now?

We did Pina on prototype equipment and remember that was before Avatar even came out. I was declared crazy. “Where do you want to show your 3D extravaganza!?” Then, God bless James Cameron, Avatar opened everywhere and there were suddenly a lot of theaters that could show Pina. And you’re right, with the technological development of 3D, I felt I was given a whole new approach to producing a poetic and immersive experience for the viewer inside the documentary field. Indeed, it was a different ballgame to shoot in 6K instead of high-def [like Pina] and to have all the tools I only dreamed of at the time. We even developed an enormous drone to actually carry a two-camera 3D rig for the landscape shots.

What is it about Anselm’s work that lends itself to 3D?

3D involves you. Other parts of your brain are put into action to see three dimensions. You’re altogether more “there”, both mentally and physically. And Anselm’s work needs your entire perception. You leaf through a catalog, and it doesn’t mean anything. You stand in front of the work or walk through it, and you’re completely

overwhelmed. I wanted to take the audience into that experience, both of him working as well as into the work itself.

How did you manage to make another feature film, Perfect Days, in all this time?

When we finished shooting, Anselm and I had a final cut. Post-production had to continue in all these different departments, from sound to visual effects, color correction and so on. There were months and months in which other people had to work, which I essentially just had to supervise. 3D is extremely demanding in postproduction. I really had time on my hands. And then I all of a sudden got this amazing invitation, out of nowhere: could I possibly think about making a film in Japan? And I said, “Yes, but only if it can happen fast because I’m not available for too long.”

That proposition was a very open invitation and a Carte Blanche in many ways. And with it came an amazing partner and writer, Takuma Takasaki. He came to Berlin, and together we wrote the basic story in two weeks. And we found the title, too. Perfect Days. Titles are so important to drive a project! I loved this one from the beginning based on a Lou Reed song. Soon afterward, I found myself going to Tokyo for two weeks to look for locations and to meet the one and only actor for this project: Kôji Yakusho. I knew his work ever since Shall We Dance and Babel and had always been utterly

impressed with him. When the possibility opened up that we could work together, it seemed too beautiful to be true. And we got along great on the spot. The language barrier was no problem. We spoke the same language and needed no words. The script was written for him, so to speak, and he became very involved in the making of the film and the preparation.

In October, I went back to Tokyo, and we shot Perfect Days in an amazing 17 days. Yes, that is fast. I love that intensity of shooting in such a condensed way. Actors love it too when they do not have to sit around waiting but can really live a story, almost as it happens. With my director of photography, Franz Lustig, we are a great team. He shot the entire film handheld, like a living tripod.

And what’s that story about, in your own words?

It’s a very Japanese story deeply rooted in Japanese culture. It digs deep into the idea of what “cleaning” means and what “service” means. The most unclean places in our Western civilization are obviously toilets. Toilets are not part of our culture; they rather represent the contrary. In Japan, there’s a whole different attitude surrounding “The Toilet”. They are essential places of everyday culture. Our story involves the most amazing “toilet temples” built in the city of Tokyo, in the Shibuya area, by Japanese master architects. Then again, this is not a film about toilets.

It is about the spirit of a man who takes care of these places. He does it with a great modesty, in the spirit of “service”, which has a whole different history in Japan. Hirayama is the man’s name in our story. He had a very different, “privileged” past in a former life but is now dedicated to these places. And to nature, trees especially. And to reading. And to listening to his favorite music. I won’t tell you more. This film is an ode to a spirit of service and to “nowness”: to live your life in the present tense.

The common good in Japan is still something altogether different than in our Western civilization, where the common good was a sad victim of the pandemic. The idea of the common good has vanished more and more, together with the sense of truth that has also gone down the drain lately. Perfect Days is about a man who finds a sense of life in service and restriction, even poverty. His routine might, at first sight, appear boring to us, but soon you realize that it is the opposite: it is filled with beauty and purpose. This man is able to live his life to the fullest.

Could you have foreseen these two films both being in Cannes?

No way [laughs]. When I finished the cut of Anselm, I told Thierry Fremaux that I had a film that I would love to show in Cannes, and he was intrigued. He liked it very much and suggested an Out of Competition slot. So Anselm, in my book, was already going to Cannes. Now, postproduction in 3D is more demanding than in any other medium, so a window opened for the other film, and I edited it almost as fast as I shot it. The Japanese producers said to me, “It looks like we could be ready in time for Cannes. Would you allow us to send it in?” I responded: “Well you must know that I may already have a film in Cannes, but who am I to forbid this to you?” And then the unforeseen happened: Frémaux called me a day before the press conference and said he would like to invite both films. I sat down and took a deep breath. A

14 DEADLINE.COM

Wim Wenders' Cannes entry Anselm ROAD MOVIES

Alice ROHRWACHER

The Italian director goes for gold with her archaeological drama La chimera

BY DAMON WISE

In less than 10 years, Alice Rohrwacher has carved out a formidable reputation for herself, notably by gatecrashing the boys’ club that is traditionally the Cannes competition, and the fact that she did so in 2014 with only her second film, The Wonders, is further proof of a distinctive talent. One competition slot doesn’t guarantee another, yet Rohrwacher was back in 2018 with the follow-up, Happy as Lazzaro. Both films won prizes— Grand Prix and Best Screenplay, respectively—which means that expectations are high for the Oscar-nominated 41-year-old Italian, whose new film, La chimera, makes it three in a row.

What can you reveal to us about La chimera?

Nothing! [Laughs] It’s very difficult to talk about the film when you have not seen it, but I can tell you that it’s the story of a group of grave robbers. We call them tombaroli in Italy, and they do it because some of the world’s most precious artifacts are hidden in Etruscan tombs. The main character is a British archeologist, played by

Josh O’Connor, and the title, La chimera, represents what we aim for and can never reach. For some, a chimera is easy money. For other people, it’s a secret goal that cannot be attained so easily.

Who else do you have starring in the movie?

There’s a very important character played by Isabella Rossellini, an old

lady living with the memory of her daughter. And then there’s a young singing student, played by Carol Duarte, a Brazilian actress who learned Italian to play the role, and there’s also a small part played by my sister Alba. But it’s an ensemble with many different roles that are played by local people. Some of them are non-professional actors. Mainly my neighbors [laughs].

What inspired the story?

Accounts of the archeological treasures that were illegally found at night in the woods, under the ground, fed my childhood. It’s somehow an epic narrative that is part of the territory I was born in and grew up in, and it’s part of the epic narrative of Italy, as with all the other countries that had a strong past civilization. But I

do remember that in the ’80s, while I was growing up, men would go out on a treasure hunt at night to try and steal any artifacts that they could find. It was almost a stereotype. However, it fascinated me very much, and, indeed, I do think that my work as a filmmaker is somehow connected to archeology. My writing process has a connection with the process of the archeological in terms of findings and practice, so I thought it was a good idea to combine these two universes: filmmaking and archeology.

Whydidyoudecidetobecome a filmmaker?

Probably because there were stories that I could not write, but I could see.

Childhood seems to be a very big influence on your work, your own

18 DEADLINE.COM

A

A A A A

FILM MOVEMENT/EVERETT COLLECTION/TEMPESTA

childhood in particular.

I don’t know if my childhood is such a big influence on my filmmaking. I know that in the territory I grew up in I was a foreigner, since my father—who’s German—is a foreigner. I somehow had the ability to see that land, that place, with different eyes than the people around me, who were somehow more used to the landscape and the place. It’s certainly a source of inspiration for my imagination and the clarity of my gaze on the marvels surrounding me. But I would never tell a story related to my childhood if I were not sure that it tells a story of human beings in general.

You were very fortunate in that your very first film, Corpo celeste premiered at Cannes in 2011. What was your experience there, and were you surprised to get into Directors’ Fortnight?

I remember that it was a wonderful experience. It was all very new for me, and it impressed me so much. I hadn’t even made a short film before that, and seeing my film selected in Cannes was already beyond my imagination. But the experience of sharing that screening with an audience… It was just so emotional for me. I’ll never forget it.

It’s a very confident film. Your style has grown since then, but it’s still a very good debut. How do you feel about it now?

I don’t know if it was a matter of confidence or of feeling irresponsible and unaware. I felt a great deal of freedom, and I still look for that freedom. The freedom was in my angle and perspective on the world that I wanted to attract viewers into. That was mainly my goal: not so much telling a story but opening a door onto a world that I wanted people to go into. That’s why I’m talking about instinct and irresponsibility. I remember the first day I went on set, I’d never seen a crew in my life before. I didn’t know who did what, but I felt such a force and a beauty in collaborating in this team effort to make the film. The collective aspect of filmmaking gave me strength, and really, I admire the

beauty of that effort.

You hit your groove with your second film, The Wonders. Critics use the term ‘magic realism’ a lot to describe it. Were you aware of that emerging style, and did you consciously develop it to get where you are today?

Yes. I think that it’s important not so much to change but to evolve. And this is the reason why I like to continue working with the same collaborators because it’s as if I were saying to them, “OK, we got here. Now let’s continue the journey together. Let’s grow together in this world we wish to share and portray.” And, differently from Corpo celeste, The Wonders was a story that was much closer to home than the first film, and therefore it was more difficult in a way because I felt a shyness that I did not feel in my first film. But I like challenges. I think that these difficult things can help you grow and mature.

As for the definition of magic realism, I’ve read it very often myself, but it was never my intention nor my will. My approach is in talking about reality the way I see it, and I try to grasp the magic that I believe is in reality. So, it’s my gaze that sees the enchantment and the wonders in looking around myself. I don’t add it on in a sort of extra dosage of it.

Your next film, Happy as Lazzaro, had the best reviews you’ve had so far and put you into the main Competition for the first time. How important is that film to you?

I think it’s the one I have the most serene relationship with, in a way,

because I feel I did my homework with that film. It’s a film that I wanted to be that way, and my sensation was of being completely fulfilled in making it. It’s like when Michelangelo said, “I see the statue in the block of marble. It’s already there—I just must carve it out.” That’s what I feel about Happy as Lazzaro. I’m not comparing myself to Michelangelo [laughs]. I’m just saying that the most beautiful feeling for a filmmaker is when you feel that you need to give life to a film, and it’s right there in front of you. Of course, I see its faults, but it’s like being in a relationship with another human being—you love their faults and their failures as well.

La chimera brings you back in Competition. Do you feel any pressure? There are famously very few women competing every year…

Yeah, indeed. The fact itself of being in the Official Selection of the festival is already incredible because it means that I got what I wanted, in a way. So, I’m very grateful to the selection committee that chose my film. And, yes, the Competition adds some pressure, but the most difficult step is to be selected and to have the opportunity of presenting your film at the Cannes Film Festival in front of the Cannes Film Festival audience. Films have a strange life in a big festival. They can shine immediately and then disappear a split second after, or they can be silent and shine later on. Of course, different epochs, different times react to a film in different ways, and awards normally reflect the moment. But the life of a film can be

absolutely unexpected after it’s been presented to an audience.

Speaking of awards, you had the experience of the Oscars this year with your short film Le pupille What was that like for you?

It was very funny, in a way, being able to attend the ceremony with Alfonso Cuarón. There are many things that I didn’t know and I could never have imagined. Amongst which, what was least expected was that there was a very familial atmosphere at the ceremony. It was just extraordinary for a short film—which tells the story of 17 little girls in an orphanage in Italy, from the pen of [author] Elsa Morante—to be selected for the Academy Awards.

Why did you choose to make a short film at this point in your career? You said earlier that you hadn’t even made one before you made your first movie.

It was actually a long short film because it nearly lasted 40 minutes.

It was Alfonso Cuarón that asked me to make a Christmas film of the runtime that I wished, and this is one of the very positive aspects of platforms—the freedom of runtime. If you think about it, when cinematography was invented, films were short: one minute, 15 minutes, up to 45 minutes for [Jean Vigo’s 1933 featurette] Zéro de conduite, and nowadays, normally, a feature film lasts two hours. It was the complete freedom that I most appreciated, and I can only be very thankful to Alfonso for this experience. I don’t know if I’ll make another one in the future. If I’m given the opportunity, why not?

Final question. This is your fourth time in Cannes with a movie. What is it about the film festival that you look forward to the most?

It’s very difficult to describe. You’ll never get used to the emotions that you feel. It’s a mixture of fear, happiness, terror, joy, shame, embarrassment, pride—all of these together when it’s the first official screening in Cannes. It is really very, very difficult to describe, but I’m looking forward to it, and I cherish the emotions. A

DEADLINE.COM 19

Alice Rohrwacher's Cannes competion entry La chimera .

Jeffrey WRIGHT

BY DAMON WISE

It’s a testament to Jeffrey Wright’s onscreen presence that he is now the longest-serving Felix Leiter—an often-thankless part that’s perhaps the 007-universe equivalent of a Star Trek redshirt—in the entire James Bond franchise. But, then, Wright has a charismatic gravitas that has served him well in the years since Basquiat, an experimental portrait of the ill-fated New York graffiti artist, first launched him in 1986. Emmy-nominated for his stint in HBO’s Westworld, he comes to Cannes with his second Wes Anderson hook-up, Asteroid City, after stealing the show in The French Dispatch as food writer Roebuck Wright.

Wes Anderson’s films are always shrouded in secrecy, but what can you say about Asteroid City? Well, it’s more Wes Anderson [laughs]. It’s set in a fictional town in the American West of 1955, or at least it was 1955 when last I understood it to be. There’s a gathering around science and innovation centered on a group of young inventors or stargazers’ , as we call them. The story flows from that until it doesn’t, and it’s disrupted by an event that affects everyone. When I read the scripts, I asked Wes if he had written it during lockdown. He said he had. It made a poetical sense to me that that was the case. But it’s a wonderful, ironic, and quirky, but also fantastical film. Perhaps in a way that many of Wes’s films are fantastical, but I found this one particularly so. And it’s a story that, for me, became even richer and more interesting on performing it. It really unfolded with

increasing detail and wonder as we got together to put it on its feet.

What can you reveal about the character you play?

I play General Grif Gibson, who’s a five-star general. He’s the host for this event, a gathering of young, brilliant scientists and inventors. And he’s there because the United States military has an interest in these young minds and their various experiments. And so, he oversees the days spent there and the itinerary.

How did you first get involved with Wes Anderson?

I first got involved in the somewhat usual fashion when my agent reached out and said that Wes would like to meet me. This was, I guess—since the pandemic—four or five years ago. My agent said that Wes would like to meet me to talk about an upcoming project

he had planned in which he’d written a part with me in mind. As it turned out, I was traveling with my kids to Paris later that week, and Wes was living in Paris at the time. We met at a cafe in SaintGermain and talked about The French Dispatch and the character of Roebuck Wright. And I found out over lunch that he had seen pretty much every play I’d ever done in New York.

I was very touched by that and surprised because I hadn’t met him backstage after any of those shows. And it was very gratifying to know that he had taken the time to do that, and that, after having taken in my work over so many years, he’d kept me in mind with the intent to work with me someday.

And so, The French Dispatch was the beginning of our working relationship.

Roebuck Wright would be a fantastic part for any actor. It’s probably one of the best parts in any of Wes Anderson’s films, to be quite honest.

I couldn’t say [laughs]. There are so many wonderful characters and performances in Wes’s films. But when he sent me the script, and it was only Roebuck Wright’s story that he sent me, I just immediately fell in love with the words on that page. It was one of the most carefully, wonderfully written pieces that I had read. And by the time

we got to set, I knew every comma and dash in the thing. It just spoke to me.

There are so many characters in that film, but Roebuck Wright is one of the more real and emotionally grounded.

Yeah. All the characters in The French Dispatch were autobiographical for him in their own ways. I think it was a very personal film for him. But you’re a writer, so you’re biased.

What’s Wes like to work with? We hear that he’s a perfectionist and obviously a stylist.

I’m probably less stylistic in my life than Wes, but I’m equally a perfectionist. So, I understand him, and I know what he wants. He’s all of that and a real taskmaster but in the best way. He has a very vivid vision for his films, clearly, and he asks a group of actors to come together that he believes can help him realize that vision. Because he has such a specific and personal signature, we all understand what he’s doing—and if we don’t, then we’re in the wrong place. We understand that we are there to be in service to him and to his ideas and his framework. I find that to be gratifying. Wes is unique.

So, I seriously enjoy working with him because of his specificity and also because I think his films are genuine.

20 DEADLINE.COM

The Asteroid City slicker spills the beans on Wes Anderson’s star-studded sci-fi

A

A A A A

DAVE J HOGAN/GETTY IMAGES

He’s not putting on an affectation. He genuinely desires to tell a story in this way on film. And I love partnering with him in that, to the extent that I do in these characters that I’ve been able to play with him. I just dig him. I think we all do.

You’re quite unusual, in terms of American actors, because you have a lot of stage experience. What is it about theater that attracted you in the first place?

Well, the actors that I appreciated growing up, and most actors of the generation that I watched as a kid, were theater actors. Folks like Dustin Hoffman, Sidney Poitier, [Marlon] Brando, these are theater actors. [Al] Pacino is a theater actor. And what first drew me to acting wasn’t film; it was theater. It was just going to the theater regularly as a kid with my mom in Washington [D.C.], seeing all the touring shows that came to town. Everything from Black musicals like The Wiz and Purlie to Annie, to James Whitmore in Give ’em Hell, Harry! and the one-man show that Avery Brooks did about Paul Robeson.

I just saw a whole range of stuff on stage, and I was just enthralled by it. And then, I got out of college and started doing theater. I didn’t do any plays in high school. I didn’t do much in college until very late. Getting back to Wes Anderson, Wes’s films are, in some ways, cinematic theater in that we all exist inside these dioramas that are essentially shifting stages for him. He also appreciates the written word in a way that’s rare for the cinema.

Is it the spontaneity of theater that appeals to you?

There’s a freedom and an unexpected aspect to it that lends itself to spontaneity. And there’s also greater immediacy in the relationship between the performance and the audience. The actor has greater control over that relationship, and that’s gratifying. I was an athlete many years ago, and there’s an athletic quality to acting, a physical quality that, at times, you can explore on film, but you do it at every

moment on stage. Even if there are quiet moments. There’s a physicality to it that I appreciate.

What’s been your favorite role you’ve played in theater?

I don’t know. Obviously, Angels in America is the most meaningful play and performance, really, of my career, because it was the epicenter of so much. It was early on in my career, and it spoiled me with the idea that we could actually do great things. And it was also happening at a time that really needed it. I mean, I don’t say that lightly: it had a profound relevance. So that’s a big one for me. But I also deeply enjoyed playing in SuzanLori Parks’ Topdog/Underdog, which recently had a revival.

Are you still keeping an eye on the theater?

I’ll get back on the stage at some point, I think. Yeah. I’ve been working on a lot of movies and, of course, Westworld, so I’ve been jumping from one thing to another. In fact, I was doing Westworld when we filmed Asteroid City. They gave me a break; I snuck off for a couple of weeks to go do it, and then went back. Right now, I’m taking a pause, because there’s been too many airplanes in too many directions over the past few years. I have a project coming out this year, as well as two others. And so, I would like to get back on the stage at some point.

This interview is going in Deadline’s Cannes magazine. What’s your experience with Cannes?

I’ve never been! This will be my first

trip. I’ve had several films there, and, for one reason or another, I didn’t make it. Mostly because I was working, and they wouldn’t let me. For example, the last time Wes had a film there, I was fully planning to go, and then I believe it was Westworld that didn’t see fit to allow me to take time off to go.

The films of yours that have been there are all very different: films like W, Only Lovers Left Alive, The French Dispatch Don’t forget Broken Flowers!

What’s the common denominator in these kinds of films?

Well, when I’ve chosen best, it’s been about the collaborators and the people I’ve worked with. And over time, I’ve gotten better and smarter and wiser in my choices. And that’s, lately, what I think is most central. Yes, of course, the story has to be interesting to me and meaningful, but you can have the best of stories and have the experience of telling those stories be completely undermined by the people that you work with. I’ve learned over time that that’s the key to this work: do it well and do it with others who are also doing it well—and who aren’t assholes.

Basquiat put you on the map. How do you feel about it now?

I’m pleased to see the ways in which Basquiat has grown in the eyes of the world, and I think that our film was the first introduction to him and his work for many people. And for that reason, I felt, at the beginning of working on it, that it needed to be done carefully. “Treat it gentle”, as Sidney

Bechet wrote. I felt that I was being asked to be a caretaker for the telling of this seriously delicate story. So, it’s just been amazing to me, from that moment to now, to see his influence on aesthetics around the world and in so many different media and ways. It’s cool because I fell in love with him as an artist when I began to study his work preparing for that role. His work, his language, just speaks to me really deeply. I get him, and I’m pleased to see that others are beginning to get him too. I’m proud that I might have played a little part in that.

What was it like working on the Bond movies? Would you go back if they reboot it?

Yeah. Or if there’s a ‘ghost of Felix Leiter’ moment, then I’ll certainly consider doing that [laughs]. But, at the same time, I had a great run on those films, together with Daniel [Craig], Barbara Broccoli and Michael Wilson and I’m very happy to let that be. I’d never expected to be a part of that franchise. I was an enormous geeky fan of the Bond films as a kid, as many of us were. I’m completely satisfied with what we did there. I’m happy to move on and let someone else be part of it.

What are you up to now?

I just finished a film last fall, which is, as of now, untitled, directed by a firsttime director, Cord Jefferson, who also wrote the script. It’s a film based on the Percival Everett novel, Erasure I think we did something interesting there. But after we finished that in the fall, I decided to take some time off and lay low with my daughter, who’s in her last year of high school, and play the role of executive assistant to her as she applied to colleges and all that stuff. I just decided to chill for a while. I looked up one day and realized that it’d been over 35 years since I’d done nothing but work as a professional actor. Now, I’d like to carry on working for as long as I’d like to work, but I also think I’m OK with a little break here and there right now. And so, I’m taking a break. A

22 DEADLINE.COM

COURTESY OF POP. 87 PRODUCTIONS/FOCUS FEATURES

Wes Anderson's Asteroid City .

THE MADNESS OF KING LEAR

Chuck Norris, Shakespeare and a contract on a napkin: Peter Sellars reveals the inside story of Jean-Luc Godard’s strangest film

By Damon Wise

By Damon Wise

There are many stories about Jean-Luc Godard in Cannes, like the year he helped to shut it down (1968) because of the civil unrest that was sweeping France at the time. Then there was the time when (in 1985) he was ambushed in the Palais by a Belgian anarchist and hit in the face with a custard pie after the premiere of Détective . And, as recently as 2018, there was the time he conducted a press conference for his film The Image Book via Facetime from Switzerland, making journalists line up to speak into a mobile phone.

But the story that endures the most is the time he signed a contract on a napkin with Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, CEOs of The Cannon Group, whose big hits that year were Invasion U.S.A., starring Chuck Norris, and Death Wish 3, with Charles Bronson. Godard— who died last year aged 92—was the high priest of art cinema and his work the epitome of avant-garde (The Onion

CANNES

FILM FESTIVAL

noted his passing with the headline: “Jean-Luc Godard Dies at End Of Life in Uncharacteristically Linear Narrative Choice”). And yet this chalk-and-cheese pairing made a weird kind of sense; Godard had agreed, for $1 million, to make an adaptation of William Shakespeare’s King Lear, written by and starring Norman Mailer, then perhaps the most famous writer in America. Mailer’s

daughter Kate would play Cordelia, the headstrong daughter who precipitates the king’s downfall.

Two years later, a workprint of the film debuted in Cannes to less than stellar reviews, and its backers’ horror was palpable (“He took Cannon for a ride,” fumed Globus). After a screening at Toronto, the film finally appeared as an ultra-limited release in the U.S. in the beginning of 1988. The New York Times described it as “a late Godardian practical joke, sometimes spiteful and mean, sometimes very beautiful, sometimes teetering on the edge of coherence and brilliance, often amateurish and, finally, as sad and embarrassing as the spectacle of a great, dignified man wearing a fishbowl over his head to get a laugh.” For The Washington Post, meanwhile, it was “like finding yourself in the middle of a poem whose meaning the poet refuses to make clear.”

It came and went so quickly that the young Quentin Tarantino faked it on his resumé. “I’d played an Elvis impersonator on one of the episodes of The Golden Girls,” he said, “but basically, I didn’t have much of an acting career. I saw King Lear, one of the few people in America who actually did, and I went, ‘Aw, no one’s ever gonna see this movie, I’ll say I was in that.’ It was a really cool credit.” And because there are no actual credits on the film, and perhaps also because it was later noted that it features early acting appearances from French filmmakers Leos Carax (as Lear’s Edgar/ Edgar Allen Poe) and Julie Delpy (as a cinema usher shrieking, “Pall Mall! Marlboro! Lucky Strike! Camel! Phillip Morris!” in heavily accented French), no one twigged. For a really long time.

Despite the irreverent glee that heralded the inauguration of the project, Godard quickly went sour on the project. “I should never have gotten involved in this nonsense,” he told BBC filmmaker

30 DEADLINE.COM

Jean-Luc Godard on the set of King Lear

From left: Johnny Hallyday, Yves Mourousi, Godard and Claude Brasseur in Cannes,

2023

CANNON FILMS/EVERETT COLLECTION/RALPH GATTI/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES FT FEATURE

Christopher Sykes in 1986. “They tried to con me, Golan and Globus. They think they’re film producers but they’re just clumsy sharks, gangsters who want to be noblemen. Golan tricked me into signing a contract on a paper napkin in a hotel bar at Cannes. I thought it was a joke but an hour later he was holding it up to the press, shouting ‘Godard, Mailer, Shakespeare, King Lear, Cannon!’ People were cheering and I thought, ‘What the hell. I need the money; I’ll do the stupid thing.’”

Almost immediately, there was conflict. Godard claimed that the first four checks from Cannon bounced. Cannon counterclaimed that Godard was over-paying himself, something Godard ascribed to a 30% drop in the dollar-franc exchange rate between 1985 and 1986. And once production did start, it hit another rock. Having arrived in Nyon, a small Swiss town in the Paris-born Godard’s adopted homeland, Norman Mailer and his daughter Kate were dismayed to learn that Godard had become intrigued by a thought that there might be an incestuous subtext to Shakespeare’s tragedy.

Having filmed just one scene, both Mailers left. Godard not only put both takes of it in the film, he broke the fourth wall, recounting in scathing detail how Mailer upped and went in “a ceremony of star behavior”. He later scoffed at the claim that he’d offended the writer. “Just a pretext,” he said later. “Mailer loves money. Besides, he wanted Cannon’s backing for his Tough Guys Don’t Dance film. Once he got it he left my movie with $350,000 in his pocket and his movie contract. And there was still no King Lear.”

This is where Peter Sellars comes in. Now an acclaimed director of plays and operas, Sellars was then an actor in his mid-20s. As a freshman he enrolled in a filmmaking class and found himself in a

seminar on Godard’s 1962 film Vivre sa vie , starring Anna Karina. “We looked at the film for 15 weeks, frame by frame on a Steinbeck, and accounted for every literary reference, every musical reference, every visual reference,” he says. “It was my first time figuring out what was inside a work of art, and following Jean-Luc’s level of detail was incredible. So I became a worshipper of Jean-Luc.”

This familiarity with Godard’s work proved useful. Mediating between The Cannon Group and Godard in the thankless task of producer was Sellars’ friend and mentor Tom Luddy, cofounder of the Telluride Film festival in 1974, who died earlier this year at 79.

“After Mailer left, Jean-Luc had no idea how to continue,” says Sellars, “and Tom knew that the film was stuck. He knew that I loved Godard, he knew that I knew King Lear really well, and so he introduced me to Jean-Luc.”

Sellars met Godard when the director came to New York to film Woody Allen in the Brill building. Allen—playing The Fool but called, in Godard’s narra-

tion, The Alien—is sitting at a Steinbeck, splicing film with a needle and thread, reciting a Shakespeare sonnet. Recalls Sellars, “Jean-Luc said to me, ‘Talk to him. Here’s the sonnet. Go teach it to him,’ but Woody said, ‘I don’t know what this is. I can’t say this.’ That scene, which is right at the end of the film, was actually the first thing that was shot in my presence.”

It was Sellars who suggested the film’s new Cordelia: Molly Ringwald, fresh, almost literally, from her final John Hughes movie, Pretty in Pink. “I said to him, ‘the person you need in this film is Molly Ringwald. She has everything. She has truly everything. And the movies she’s been in have all been captivating, but she has so much more in her. And if she could actually touch Shakespeare, this would be incredible.’”

In the meantime, to replace Mailer, there were two old-Hollywood options: Rod Steiger, who refused to travel, and Burgess Meredith, who was Luddy’s first choice. “Burgess signed on,” says Sellars, “and then we were all set to go meet Jean-Luc. He insisted that we take the Concord, so the three of us got on

32 DEADLINE.COM GETTY IMAGES/CANNON FILMS/EVERETT COLLECTION 2023 FILM FESTIVAL

CANNES

From left: Godard and Anna Karina in Cannes; with Peter Sellars in King Lear

FT FEATURE

Cannon Films owners Yoram Globus and Menahem Golan in Cannes.

the Concord, but when we arrived in Paris, Jean-Luc was still not there.” They spent three days in the airport hotel then went to Nyon, where he was shooting. “Our trips to and from the shoot were silent because Godard was so overwhelming a presence that anything you said sounded unbelievably stupid after he said what he had to say. It was quite intense.”

The work situation was also intense. “At no point did anybody see a script,” Sellars says. “Whatever Jean-Luc wanted to shoot would be presented in the morning to me, and I was to present it to the actors. Two young women were the cinematographers, and they knew that it was an incredible privilege to work with Jean-Luc. They got a serious course because Jean-Luc was meticulous about everything. And I learned a lot of the most important artistic lessons of my life during those days. In particular: never point the camera at the view. Point the camera in some place no one would ever think of looking.”

Molly Ringwald, at 18, and Burgess Meredith, nearly 80, were both old hands by now, actors who were used to serious film sets with such things as hair and makeup. But they found none of the usual niceties in Nyon. “Poor Burgess,” says Sellars, “speaking these lines that he had spoken in his youth, but never knowing what we’re going to shoot from day to day. It was all just literally sprung on him. That’s why, in the film, I have to write things down and hand them to him, like it’s a telegram that’s being delivered, for example, because Burgess never had the time to learn any lines. And he felt that as a humiliation. But, of

course, for Godard, it becomes one of the most poignant and beautiful things of the film as you watch human failure with old age. It has a tragic stature that I think Burgess never realized was coming across in the footage.”

Suddenly, after three days of shooting, Godard sent Ringwald and Meredith home. “He said, ‘I’m done. I don’t need to see anything more.’ They were shocked. They thought they were being fired, but he said, ‘I just don’t need to see anything more.’”

What nobody knew was that Godard’s film was starting to come together in his mind, and Mailer’s original vision for the film had planted a seed: that script was called Don Learo , since Mailer thought, as he says in the film, that “the

mafia is the only way to do King Lear .” Meredith, as Learo, was a depository for everything Godard hated about the movie industry, and the film is rich with references to the mob and Las Vegas, while alluding to the idea of mainstream cinema as exploitation, a form of racketeering.

The finished film begins with that sense of vitriol: before Godard’s denunciation of Mailer, there are panicked voicemails from Golan and Luddy and a stark intertitle screams, “A PICTURE SHOT IN THE BACK.” (By whom? By Mailer? By Cannon? Or Godard himself? All these readings are possible.) But once this is out of the way, King Lear becomes, very recognizably, of a piece with the work Godard was doing in the same period, films that actively deconstruct storytelling while at the same time expressing sophisticated ideas about art and beauty. In this case, this means cross-pollinating King Lear with Shakespeare’s Sonnets, Virginia Woolf’s The Waves and a whole lot more.

The setting is a post-Chernobyl world where society has rebuilt itself after a harrowing nuclear winter, but art and culture has been destroyed. Into this bleak landscape comes William Shakespeare

34 DEADLINE.COM CANNON FILMS/EVERETT COLLECTION

2023 FILM FESTIVAL CANNES

Above: Sellars in King Lear ; Protesting directors in 1968, from left, Claude Lelouch, Godard, François Truffaut, Louis Malle and Roman Polanski.

FT FEATURE

Molly Ringwald and Burgess Meredith in King Lear .

Jr. the Fifth (Sellars), who is on a mission to restore his ancestor’s works. Along the way he encounters Professor Pluggy (Godard himself), a character memorably described by The Washington Post as “decorated like a kind of Rastafarian Christmas tree with variously colored audio and video patch cords, chomping a cigar and speaking, nearly incomprehensibly, out of the side of his mouth.”

It’s quite a look. Did Sellars know he was going to do that? “No,” he says. “When you see the film, you’re seeing me walk in and see him for the first time looking like that. And then I have to come in and sit with him. But, you know, it makes sense. He considered himself to be on the cutting edge of film tech-

nology, the technology of tomorrow, and so his wig is his statement of him not being in the world of John Ford. It’s his way of saying that the future of film is going to be this high-tech, electronic manipulation. So when we meet, he and I are in solidarity, because he, also, is reconstructing a lost art—the lost art of film—but with new technology.”