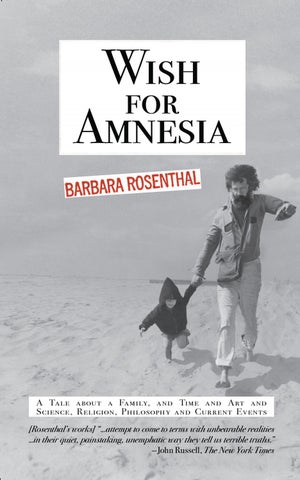

A Tale about a Family, a nd Time a nd A rt a nd Science, Religion, Philosophy a nd Current Events [Rosenthal’s works] “...attempt to come to terms with unbearable realities ...in their quiet, painstaking, unemphatic way they tell us terrible truths.” 1 —John Russell, The New York Times

Wish for Amnesia

2

in PRAISE of WISH FOR AMNESIA …satirical, fantastical, and philosophical….. We see the world…most rivetingly…. readers will find they can’t take their eyes away. They’ll also sometimes wonder what’s real and what’s not—and exactly what kind of magic might be at work. A celebration of the dysfunctional that will keep readers turning pages. — Kirkus An extraordinary cast of characters who shuttle between divinity and depravity, motivated by a blinding vision of perfection. Thought-provoking, beautifully written and fully engaging. Brava! —Jeffrey Cyphers Wright, Goodreads ...fast-paced, surprising, heart-wrenching and beautiful. It touches the reader’s soul. Rosenthal elevates storytelling to a high note.…The tale stands out in imagery and tight, gripping plot [in which] historical moments…beautifully intertwine…[It] merits five stars and a read from every book lover in the world. —Kleio Bhagwati, Wicked Venom …extraordinary…compelling… a loom...of finespun hard-steel cable.... Clinical precision and vertiginous pace combine in...the most astounding passages of English prose you’ll ever read.…[and] take Wish for Amnesia from merely brilliant to root-and-branch reinventive. This...richly tapestried infrastructure…finds few literary precedents … (maybe Joyce). —L. Weichselbaum, Home Planet News …a fable-like fiction… a well-drawn mise-en-scène of the senses…. Wish for Amnesia is complex and folds back on itself even as it moves forward…. A Möbius strip of science and magic. [A]wild ride, careening through time, space and levels of reality…. The writing is rich.... Wish for Amnesia is well worth reading. Multiple times. —Pam Kray, Afterimage Rarely have I felt a sense of place as vividly ...The same is true of the characters, each of whom is a complex universe...rendered with startling authenticity—and humor. Rosenthal is a master craftswoman—each sentence a sculptured gem. Reading the book a second time, I’m blown away even more...this time around. An awe-inspiring achievement!!! —Stanley Hoffman, Amazon Barbara Rosenthal re-imagines the art of fiction between new modes of imagination and reality. She is the closest thing we have to a Wallace Stevens. —Stephen Paul Miller, ed. Radical Poetics and Secular Jewish Culture An adventure in language, and an entertaining “Siddhartha-type” read… likely to touch a responsive chord.... [A] kaleidoscope of references... delightful to experience. —Mike Foldes, Ragazine A very clever, powerful and complex book...about the contest between priorities of the mind, the body and the soul. —Angharad Lodwick, Tinted Edges3

Wish for Amnesia

other BOOKS by BARBARA ROSENTHAL BOOKS, sole author Soul & Psyche

ISBN 0-89822-121-8 Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1998

Homo Futurus

ISBN 0-89822-046-7 Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1986

Sensations

ISBN 0-89822-022-x Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1984

Clues to Myself

ISBN 0-89822-015-7 Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1981

PAMPHLETS, sole author Existential Cartoons

eMediaLoft.org, NYC, 2007

Names / Lives

eMediaLoft.org, NYC, 2001

Haunted House

ISBN 0-9728260-1-7 Washington Street Press, 1997

Children’s Shoes

eMediaLoft.org, NYC, 1992

Introduction to the 1976-1986 Trilogy eMediaLoft.org, NYC, 1987

Old Address Book

eMediaLoft.org, NYC, 1984

Structure and Meaning

eMediaLoft.org, NYC, 1981

BOOKS in collaboration Sitting Book visual direction & design with poet Bonny Finberg ISBN 0-97607893-3-x Xanadu Press, NYC, 2017 Party Everywhere visual direction & design with poet Jeffrey Cyphers Wright ISBN 0-97607893-9-9 Xanadu Press, NYC, 2014 Roger’s Reference: Dictionary of Homonyms & Homophones American-spellings editor with editor-in-chief Roger Burke ISBN 0-9579618-2-0 Chiasmus Press, Morayfield, AU, 2005 Weeks photographer with poet Hannah Weiner ISBN 0-9770049-7-x Xexoxial Endarchy, La Farge, WI, 1989 4

ABOUT previous WORKS by BARBARA ROSENTHAL // “...an attempt to come to terms with unbearable realities...in their quiet, painstaking, unemphatic way they tell us terrible truths.” —John Russell, The NY Times. // “...incessantly personal, even naked, with an emphasis on language...” —Manohla Dargis, The Village Voice. // “...profound work...pithy, poignant, prophetic... high content...” —Clare Carswell, Flash Art International. // “...dreamlike, associative...” —Shelley Rice, Artists’ Books: A Critical Anthology. // “...hyper-real...”—Ngan Le, Berlin Art Link. // “...effective directness...”—Laura C. Lieberman, Afterimage. // “...Platonic ideal...large and public scale...transgresses conventional limits...” —Ellen Handy, Photography Quarterly. // “...a very funny take on life...sardonic...” —Bill Creston, underground filmmaker. // “all sorts of interesting other meanings...” —Buzz Spector, co-founder WhiteWalls magazine. // “...truly original...” —Richard Kostelanetz, Dictionary of the Avant-Gardes. // “...questioning the modern milieu...” —Pam Kray, Book Arts, London. // “...introspection, reflection, and the texture of the material world...” —Philippa Hawker, Sydney Morning Herald. // “...A one-to-one experience...” —Shelley Rice, The Franklin Furnace Flue. // “...a thinking artist...” — Judith Hoffberg, Umbrella. // “...a Freudian concept of the uncanny, where familiar things are imbued with strangeness...” —Natalie Zayne, Belgo Report, Montreal. // “The paradox is to share the ultimately private... — George Myers, Jr., Introduction to Modern Times. // “...charged with psychic energy...” — Laurie Schneider, Score. // “...alongside John Cage and Alison Knowles and Philip Corner” —Carol Bergé, avant-garde poet. // “...combines mass culture and interior monologue...” —Ellen Handy, Arts. 5

Wish for Amnesia

6

Wish for Amnesia A Tale about a Family, and Time and Art and Science, Religion, Philosophy and Current Events

7

Wish for Amnesia

NY Times: November 14, 1985

NY Times: December 29, 1985

None of the characters or references are meant to represent any person living or dead, unless they are named correctly and are so famous they are fair game. None of the places refer to anyone there. None of the scenes ever took place, there is no association with Columbia, Princeton or the U.N., nor was a Times article yet ever written about Jack. But every quotation is transcribed accurately from the author’s contemporaneous readings copied by hand into her Journals, and all general history and specific dates are real whenever possible. On Dec. 27, 1985, terrorists attacked two airports, and Halley’s Comet neared the Earth. All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, television or internet article, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Publisher. ISBN 978-1-937739-92-8 first edition, 2017 (definitive, 2018) ISBN 978-1-937739-66-9 first edition eBook, 2018 ISBN 978-1-937739-83-6 pink skin proto-edition, 2016 ISBN 978-1-937739-28-7 fine print proto-edition, 2015 ISBN 978-1-937739-75-1 white/tan/purple proto-editions, 2014/2015 ISBN 978-0-976079-36-1 comb-bound proto-editions, 1990-2005

Published by Deadly Chaps Press New York, NY, USA http: //www.deadlychaps.com/novel wishforamnesia.com 2018 8

Foreword

FOREWORD by Joseph A.W. Quintela, publisher A t a sun-soaked gathering of poets in 2013, in a grassy Queens park overlooking Manhattan, I first encounter Barbara Rosenthal, barefoot, face shaded by a wide-brimmed black hat, perched on a stone wall and looking every bit the part: an oracle. This image alone might be the ideal introduction to Wish for Amnesia. I recognize the artist immediately, but it takes a while before we say hello. At the gathering, we are both performing poetry interventions that use text cards to initiate interaction. At one point, we each spontaneously say something aloud that combines two of our cards in a moment of cosmic collaboration. By this entrÊe, I find myself joining her later for Long Island Iced Tea and rambling conversation that returns frequently to one preoccupation of the ensuing pages: the multiplicity of variations that exists within an individual’s perception of time:

Wish for Amnesia

“…time plays tricks,” reflects Jack, the pivotal character in the novel and, for me, this has never been as true as it is in this hours-long conversation, which has never left my mind. By the time we part on the subway back to Manhattan, my head is pleasantly reeling. So begins my acquaintance with this futurist, visionary and tragi-comedian. The agreement to finally publish Wish for Amnesia with Deadly Chaps Press comes a year later. At this point, we’d planned to release a trilogy of her “journal-text artist books,” assimilating materials from 1990-2005, and she previewed a segment from it on our stage at the NY Poetry Festival on Governor’s Island in July. However, as that project expands it becomes clear that it must be prefaced by the very thing that prefaces the decade: construction of the first of her two existential novels, slowly developing in suspension forty years. So work on the trilogy is paused in October of 2014 as Barbara throws open one of the Six Trunks of Journals, Drafts, Workbooks and Mock-ups that occupy her riverside loft in the Westbeth Artists’ Complex in Greenwich Village. From this treasure trove of process notes, thick files and looseleaf binders devoted to characters, scenes, philosophic compilations and chronologies begun in 1978, she pulls a comb-bound copy of the Wish for Amnesia 1991 “protoedition.” I rush it home. I can not put it down. I am smitten. All too prophetic at the time of its writing, and with a plot that concludes in 1985, the novel’s immediacy right now is striking. Now is its time. Rosenthal’s concept of the “Trans-Millennial Century,” an era whose beginning could be marked by her own birth, might best be seen as the era of reckoning for the excesses of Modernism. She marks its onset year as July 23, 1944 - August 6, 1945, “the simultaneous first liberation of the Concentration Camps and first dropping

Foreword

of the A-Bomb, when worldwide and together we faced the Horricides of ethnic annihilation in the cause of mass hysteria.� It is on this stage, woven with pivotal events plucked from history, that Wish for Amnesia unfolds. She subtitles it a Tale about a Family, and Time and Art and Science, Religion, Philosophy and Current Events. In short, a book almost as exhaustive in purview as its author. In this wackiest of deadly serious pieces of literature, Rosenthal creates the universe, re-conceives God, rapes, murders, gives birth, undergoes transformations, commits child-abuse, sustains child-abuse, crashes a car, ideates artworks, throws a party, has lots of sex, smokes lots of marijuana, makes a daring escape, gets appointed to high office, develops computerware, splices genes, contacts extraterrestrials, puns and cracks jokes, places fifty-eight photographs, and lets you know everything there is to know about being an idealist, and a contemporary, secular Jew, an artist, child, teen, daughter, woman, wife, mother, or any cosmopolitan of any gender or ethnicity, or any kind of human being at all. It certainly can be understood on its own as a work of pure, rollicking fiction, presented in a duality-paired quantum-like structure by a long-time college professor of both English and Art spoofing the rules. But Wish for Amnesia is also the serious, unflinching, philosophical exegesis of a clearly defined universe. We contemplate human identity from the vantage of information overload, which, as Rosenthal correctly predicted in her four previous books, would change the human mind. And it also contains some of the most quotable terminology and sure-fire new memes of any epoch. In life, Barbara Rosenthal is a performance and media artist, a “media poet,� who has inhabited many personas, directing them variously throughout the world.

Wish for Amnesia

But here in her first novel, these many personas fall back toward one another on the page. The book opens with a stark image of two characters falling toward one another on a moving train. This image stays with me throughout, as I see the performance being replayed. Characters, scenes and ideas are often paired, so veering in and glancing off each other often result. Much of her work incorporates paired dualities: mind and body, natural and artificial, sea and sky, male and female, real and unreal, sight and sound, art and science, speaking and writing, innocence and corruption, as well as semantic opposites. She says she herself has only “two time zones: Now and Not Now.” We are lucky to be here together in Zone Now. But watch out! Most of her pairs function in triads. “Where are we really now, then?” she asks. Much of the work Rosenthal has produced in her fifty-seven years as an artist and writer is still largely unknown to a wide public, and this book might have been among them. The structure and first edit was completed by the end of 1985, and in the early 1990s, Gunther Stuhlmann, editor of Anaïs Nin’s diaries, and literary agent to both, represented Wish for Amnesia to the very best publishing houses (Vintage, Putnam, Grove, etc.), but unfortunately he died before “finding this baby a home,” as he wrote in a letter to her. So, casually over the years, as many other projects were produced, this novel was periodically redrafted and sporadically submitted to ninety-six agents and well-known commercial and independent presses, who, I hope, are kicking themselves today. At last, after many hurdles, changes in typing technology and seventeen proto-editions, this extraordinary book found its way to my desk. I hope you’re glad I’ve gotten it to you. —Joseph A. W. Quintela, NYC, January 4, 2018

12

Wish for Amnesia

13

Wish for Amnesia

This book is dedicated to my close family, here and gone: my children, Ola Creston and Sena Clara Creston; their father, Bill Creston; our grandchildren, Zeia Mays Brittenburg and Castenea Quinn Brittenburg; my brother, Gilbert Alan Rosenthal; and my parents, Leon Rosenthal and Evelyne F. Rosenthal.

14

If there is merely inward looking and never outwardlooking, there can be no distinction between what has value and what has not, between what is precious and what is vile, between what is noble and what is vulgar. — Hsun Tzu, Confucian scholar’s criticism of Tao. 3rd c. bc When I thought to know this, it was too painful for me. — King James Bible. Psalm 73:16 We do not see things as they are. We see things as we are. — Rabbi Shmuel Nachmani,Talmud tractate Berakhot 55b

15

Wish for Amnesia

CHAPTERS SECTION ONE

1. 1. 1. 1. 2. 2. 3. 3. 4. 4. 5. 5. 6. 6. 7. 7. 8. 8. 9. 9.

16

PROLOGUE Poland, 1943 Chaim and Chava................................................................ 1 COMMENCEMENT New York, 1968 Jack Walks up Broadway to His Office ………...........…........ 4 Chaim’s Letter to Jack ……………………….………….............…14 11 13 Six Quick Letters, Jack and Beatrice ………….…...............….16 22 Beatrice, Effluvia .................................................................24 26 Jack Meets Beatrice at Kennedy Airport ..............................24 32 Caroline Meets Letty on the Playground ..............................30 34 Letty’s Mother Dying ..........................................................39 40 Caroline and Letty, Carmine Street Pool ............................... 43 49 52

Chapters

SECTION TWO

New York and New Jersey, 1969-85 10. The Birth of Jewel ................................................................ 52 1. 11. Caroline’s Sketch Pad I ....................................................... 65 2. 12. Caroline’s Sketch Pad II....................................................... 74 3. 13. Jewel .................................................................................... 80 4. 14. Caroline and Jewel Drive to the Country .............................. 82 5. 15. Incident at the Abandoned Farmhouse ............................... 93 6. 16. Jewel’s Notebook ................................................................ 1103 7. 17. The New York Times Article about Jack ............................... 112 8. 18. Caroline and Jewel Drive to the City ................................... 1114 9. 19. Caroline Parks Car and Walks Back Alone ........................... 125 10. 20. Caroline in the Drug Store ................................................. 138 11. 21. Jewel Enters Beatrice’s Party Alone .................................... 146 12. 22. Jack and Caroline Enter the Garden ................................... 162 13. 23. Jack’s Speech: Homo Futurus in the Trans-Millennial Century. 168 14. 24. Jewel Dreams the Physics Dream .......................................... 178 15.

SECTION THREE

25. 1. 26. 2. 27. 3. 28. 4. 29. 5. 30. 6. 31. 7. 32. 8. 33. 9. 34. 10. 35. 11. 36. 12. 37. 13. 38. 14. 39. 15. 40. 16. 41. 17.

Rome, 1985 Beatrice and Jewel Walk Along the Tiber .............................. 181 A Taxi Driver, Toto ................................................................ 186 Toto, Beatrice and Jewel on the Gianicolo at Sunset ............. 196 Toto, Beatrice and Jewel Drive to Ostia ................................ 208 In Ostia ................................................................................. 212 Jewel Swims Out ................................................................... 223 Exhausted and Exposed ....................................................... 233 Incident at the Northern Cove .............................................. 235 Toto and Jewel Return to the Shack ...................................... 238 Telephone Call to Princeton ................................................. 249 Caroline at Computer I ......................................................... 261 Da Vinci Airport.....................................................................265 Jack Lands ............................................................................. 269 Toto Locates Jack .................................................................. 276 In the Air ............................................................................... 282 Caroline at Computer II ........................................................ 284 From the Skies over Italy ........................................................286 17

Wish for Amnesia

SECTION ONE

18

Section 1 Prologue. Chapter 1: Chaim and Chava

PROLOGUE Poland, 1943

19

Wish for Amnesia

20

Section 1 Chapter 1: Chaim and Chava

Chapter 1 Chaim and Chava Chaim and Chava met in a boxcar with a thousand other Jews, two of ten thousand on a transport to Auschwitz. They fell toward one another, contorted, swollen figures wrenching and lurching into areas of the car with less resistant human tissue. They dangled with the others, dead and living, tight, like upright worms, desiccating in their thirst and filth, pressed and introduced in private scandal. Chaim was sixteen, blond; Chava, fifteen, alabaster skin, black hair, like Snow White. Their parents were not present. After three days, the transport was halted in abandoned countryside outside the gates to allow for removal of the dead. No water was given to the prisoners, barely living. A wasp stung one of the guards. Chaim saw his chance to escape, and escaped with Chava. 1

Wish for Amnesia

Within time, they met partisans in the forest, and soon joined a band of brigand-Jews in a fragile supply chain toward the Warsaw Ghetto, ultimately broken and defeated due to refusal of assistance, well-known. When they could, they escaped finally to America, and bore a child here: Jack Rubin.

2

Section 1 Commencement. Chapter 2: Jack Walks up Broadway to His Office

COMMENCEMENT New York, 1968

3

Wish for Amnesia

Chapter 2 Jack Walks up Broadway to His Office On Broadway at 110th Street facing north, the sun

from straight behind cast a long shadow, fast advancing. Jack was walking up to Columbia to pick up his mail, then home to 103rd. He was smiling to himself, six feet tall, tangled black hair to his waist, beads, feathers, the gaunt and bearded leader of a great counterculture. His thoughts were on — Heaven. “Heaven,” he said out loud, and imagined a state wherein all ecologies harmonize in beneficent bliss. Jack saw it as his duty to act on his ideals, to be righteous and worthy, to give to the world all that he could make best in himself, and to inspire in others love and humanity. He felt that his life was a gift to the Earth and that through his person the fate of the universe could advance more near to Heaven. He was born, he thought, from the 4

Section 1 Chapter 2: Jack Walks up Broadway to His Office

womb of the Twentieth Century: his genes alone were salvaged from the wreck. “Are we tightening our boundaries again?” he thought aloud, and people heard him. Passersby turned with admiration as they recognized him, and some saluted with the V-finger peace sign, but he paid them no attention. He saw in his imagination elaborate geodesic figures that he’d made as a child from paper straws. Each figure had taken months to complete. To this day they still hung like fat stars from the ceilings of his parents’ apartment in Forest Hills, Queens, an airless three rooms rarely visited. They had lived a quiet existence since coming to America. They never talked much about the past. Jack didn’t see his family often. Many grown children didn’t, anymore. People were coming into prominence about this time with names very similar to his own: Jerry Rubin, Jack Ruby —. “Jewery,” he thought, or heard. Take Only What’s Offered! Morality clichés thundered admonition. Just Where Do You Come Off! Strange voices from out of nowhere had been yelling at him lately. Jack was 29, a little old for his radical leadership and not altogether suited to it. He was better fit, personalitywise, for the role of theoretician than of guru. “I want a letter from Beatrice today, I want a letter from Rome today,” he chanted, striding, concentrating, swinging his old, cowhide briefcase from hand to hand, its straps and buckles flapping. He smiled his constant smile, which masked these inner shouts. Speak Only When Spoken To! another old saw cut into him. Ask For Nothing! You Are A Fraud! You’re Only In It For Yourself! 5

Wish for Amnesia

The voices challenged his sunny face. They were familiar voices, commands by one in particular, which Jack had come to think of as The Voice of the Petty Accuser. Onslaughts of auditory hallucinations were pursuing Jack Rubin with increasing frequency as he rose and emerged as a leader of the Peace Movement, a speaker for his peers. Who else but a son of heroes, a brilliant mind. “Who, who,” Jack called out, hooting as more people gathered, following after him as he walked. Cross-examination of the voices, rebuttal, was permitted, but Jack never won. He was never even told the charge. At each imaginary trial, he felt he must convince not only of his innocence, but of his nobility beyond innocence, and thus he was always defeated. He knew that his hallucinatory judges were barbaric hypocrites, that there were no common values or vocabulary; he was certain of the inferior mentalities of the yahoos on his nightmare juries, yet was hounded by his inability to clearly state his point within their limits. He was tormented. As he got closer to the exact language with which to phrase his position and win the philistines, the meaning of his statements evaporated on the witness stand, and he was, each time, left helpless and speechless, often even voiceless. Every night he would awaken to find himself standing on his bed, screaming a silent scream. Crowds were growing behind him on the street. People pressed closer in on him, trying to keep pace with his long, fast stride, turning their faces to bask in the smile he hardly knew he wore. Jack pushed his black hair out of his eyes, startled to see real people in front of him. He knew he could never purge himself of these fantasies until he won his case. What is my case? What is the case against me? All Jack ever believed for certain was that nothing was ever right. I know I’m right...I’m Left! (I’m all that’s left....) 6

Section 1 Chapter 2: Jack Walks up Broadway to His Office

Someone blocked him and was grabbing his arm! An unsavory Corsican seaman was requesting his autograph. The filthy young sailor held out to him a leather volume and a meticulously crafted fountain pen. It was mother-of-pearl and lapis inlaid, but the ink smelled like blood, and ran red. Jack uneasily obliged, but kept walking. His mind was tortured. He tried talking to himself. Was it karma? neurosis? metaphor? collective unconscious? hereditary psychosis, imbalance of nutrients, effect of poor posture? Should he seek analysis or hypnosis or wait it out, smoke more dope or less —. Someone handed him a lit joint rolled in licorice paper, and met his eyes. Jack toked on the gift, cupping it in his hand. Then he paused to look at his followers. They became still and watched him. He selected a pretty, young woman and neatly passed the marijuana to her, then raised his arms dramatically above the throng. “Conscience has advanced to this point from the moment of our dawn on the beach,” Jack said, projecting his calm, smiling facade out over the crowd. “But time plays tricks. Do not be fooled.” That was all. He opened the face of his hands to stop his people from massing, and turned into the gate of Columbia University between its guardian stone statues, the male, Scientia, on the left, and his female companion with book — unnamed? Must be Ars, he reasoned every day, almost a mantra or password. “We are nearing the end of the Ages of Culture,” he said, casually smiling to the small, privileged, inner group still dogging his steps, and he stopped to list as they occurred to him: “Age of Earth, Age of Order, Age of Esthetics, Age of Mechanics, Age of Biophysics, Age of Astrogenetics.” He laughed out loud. For each age, a geodesic paperstraw star was imagined. He couldn’t get this walk done fast enough. 7

Wish for Amnesia

Before he reached the McPherney Building, he had outpaced most of the youthful band still pursuing him. A few remaining breathless Barnard co-eds and dedicated joggers gaited him to his office door. Today he would not pause with them, although sometimes he did. One boy, Arnold Saperstein, found waiting when he arrived, was his lieutenant, but today Jack had things on his mind besides the Movement and dismissed him with the others. “Do whatever’s right,” he said when Arnold tried to urge urgent messages and events. “This isn’t something I can handle myself,” the boy said weakly, while Jack flipped his keys. “Then don’t,” answered Jack, and snapped the door open and shut. He was sweating when he finally could lean on it for support, still holding the knob in his hand behind his back. It was an old, wooden, public school-type door with four star-textured, translucent glass panes. The group outside could see him through it! Jack jumped out of the way and flicked on the overhead fluorescent lights, knocking into a partition put up recently by one of his officemates. “Damn,” he grunted, stumbling through the cluttered room toward his own place near the windows. He pushed some papers back and sat on the edge of his desk. Although Jack was alone at the moment, four grad-student teaching assistants shared this room: Jack Rubin himself, in Political Science with crossovers in Anthropology and Genetics; Rabinowitz, in Sociology; Reilly, in Astrophysics; and Ross, the linguist. It was an office built for one, so each had jury-rigged partial enclosures and taken them first-come; Jack was lucky to get a window spot, which he had not partitioned off. Ross had the other window, and Reilly and Rabinowitz, who also used Columbia’s new computer center, preferred seats near the door so they could sometimes beat Jack to it. 8

Section 1 Chapter 2: Jack Walks up Broadway to His Office

Their two cubicles were clean and tidy. Jack’s and the linguist’s were heaped with papers and objects and old correspondence. Today’s mail wouldn’t be in yet; it was still before noon. The faculty boxes were located near the coffee machine; he’d go there soon and then settle in for the rest of the day. Jack didn’t like receiving mail this way, but the brass mailboxes in the doorway of his shabby tenement building were so destroyed by junkies that he had no choice. He stood and stretched and paced around the desks. He passed time in front of Ross’s bulletin board: picture postcards, notes, memos, photos, a few stray words on scraps of paper, a calendar with every day of the month through yesterday x’d out, and a Calvin and Hobbes cartoon, everything tacked with identically angled steelhead thumbtacks in all four corners and evenly spaced on the board. Jack’s area wasn’t neat, or even clean. His girlfriend, Beatrice, though, was immaculate. And she wouldn’t have given her autograph, like I just did, either, he thought, acknowledging another of their dissimilarities as he remembered signing for a sailor out on the street, the bloody pen. The autograph book itself had given him the creeps too, felt like infant skin. He looked at his watch, a high school graduation present from his father. Still too early for the mail. He ringed one sinewy wrist with his other hand, dirt around the cuticles and under the nails, lifeline and fateline etched in grime. He wiped them on his sleeves, clanking the beads and chains that filled his shirtfront. He didn’t want to read the cartoon. Academic humor depressed him. The only humor Jack Rubin appreciated was crass, sexual innuendo. He recognized that this was low, but was secretly proud of his own imaginative depravity; he weighed judgement solely on deed. Just like everyone, he liked to mistakenly think. He moved to the astrophysicist’s desk and crashed down in his seat. Reilly had retained the walnut desk he 9

Wish for Amnesia

had been issued, polishing it daily with lemon Pledge, but bought himself an executive armchair from an office furniture showroom in The Bronx. It had a wide cross-base on wheels and leaned safely in all directions. Upright on the desk stood a set of marbleized cardboard cutaway boxes of sociology publications and a formidable bronze pipe-suzy. Jack pulled out one of Reilly’s pipes and a periodical. He stuck the pipe in his mouth without filling or lighting it, and bobbed back in the chair with the journal. It absorbed him more than he expected, and not before an hour had passed did he stop chewing his officemate’s pipe, return it to the caddy without wiping it dry, slide the journal into a random place in the otherwise date-ordered file, and roll backward to go check the mail. It was his charming, confident, public self who sauntered down the corridor, but his face was lying; the dreaded words came back. Fuck You, Asshole! Everyone brightened attentively when they saw him, but for Jack, charisma had this awful flipside. How could he make the voices stop? He faced the wall of alphabetized pigeonhole boxes stuffed with rolled mimeographed notices, half-sheet pink memos, manila envelopes and a few real letters. He knew the location of his own box, and stooped to verify his name: the tags repeatedly came off; Jack had retaped his a dozen times. He pulled out the roll of papers and threw away all the ads without reading them. The pink memos he glanced at casually, tossing out any from students, newspaper reporters, the Dean, the Chair, the charity and blood campaigns, etc. Today there was one he kept, notifying him to pick up a package at the office window, too large for the pigeonhole. There was also the airmail-stamped letter from Beatrice he was hoping for. His father had sent the package: a 4-foot-long, 3-inch-square tube-box. Jack didn’t know what was in it. He 10

Section 1 Chapter 2: Jack Walks up Broadway to His Office

had not seen his parents in a long time. He used to see them reasonably frequently, but then they had some words about his girlfriend. Actually, Chaim and Chava easily welcomed Beatrice. It had been she who had weaned him from them. He brought the mail back to his office and cleared a space on his desk by stacking three unrelated piles of papers on top of each other and moving them to the window ledge. A plant that had dried up and died there, he placed on the floor behind his own ratty, college-issue chair, and sat down. He couldn’t decide which to open first, or whether to take them both home. What to do home and what to do in the office and which materials he might need in which place, was a continual dilemma. His tendency was to work at home and keep his college office as a token. Papers for the Movement all stayed with him in his old, cowhide briefcase. Instead of opening either, he reached for two clear, crystal objects he used as paperweights, and toyed with them. Each was five inches high: one, an open-apex pyramid; the other, a partially hollowed, interior-faceted, flat-bottomed sphere that fit over it. They were scale models for the double-walled structure called Science & Art Double Pavilion that his girlfriend, Beatrice Stregasanta Madregiore, had designed for glass and steel construction at last year’s Sao Paolo Bienal. The open pyramid was Science and the internally faceted sphere was Art. Spectators entered the pyramid through the sphere and looked vertically through a conjoined open oculus, or sideways at angles through shafts of natural and artificial light. Some of the internal facets were one-way mirrored, some double mirrored, some clear prismatic vitreum. And what seemed at first to be mirrors, reflected their figures in slowed-up time, altered coloration and scale. This echoed the human sounds re-sounding vocal pitch, modulation and ambient audiations. Other machinations recalibrated hour of day and each person’s sense of nearness to each other. 11

Wish for Amnesia

The Sao Paolo Bienal was one of the world’s two great international biennial art exhibitions, vying with another in Venice, and Beatrice represented the United States that year in both extravaganzas. In Venice, she had installed her You & I Transmission. Light patches and slices of visitors’ reflections bounced to format recomposited projections on the facades of the palazzi. Full-body floating holograms of the passati morphed their ages, races and sexes. Jack fooled with her elegant prototypes, placing them over his nipples and then his eyes. No American artist rivaled Beatrice Stregasanta Madregiore in clarity and simplicity of production, or in originality and profundity of idea. No viewer could remain untouched by the cosmic interaction she played agent for. Her work was an Avant-Conceptualism that found expression in large-scale public projects and theatrical events. As a performer, Beatrice made magic on the stage, impossibilities of instantaneous change in character and appearance, reversals and restructurings of time and space. Her pieces dealt with black and white, sight and sound, natural and supernatural, imagination and perception. In one called Ici/Voici, she effected pyrotechnic explosions along the River Seine, appearing and vanishing on different bridges before each discharge was perceived. She cultivated many myths about herself, and was as surrounded by acolytes as Jack. Although publicly they were not linked as a couple, Jack’s love for this dramatic woman was catalytic to his charisma and political leadership. He lifted her letter to his forehead. He placed his lips on the Italian airmail stamps she had recently licked. He breathed deeply the scent of her. Some people believed that Beatrice was prophetic. She spoke extemporaneously with little frequency, and 12

Section 1 Chapter 2: Jack Walks up Broadway to His Office

conversationally almost never, but her pronouncements were portentous. Her followers transcribed her words, and dutifully convocated to divine her hidden messages. Twoedged words were essential to her pieces, particularly in the titles, and her essays and articles on the nature and theory of art and the mentality of its production set standards for evaluating past and present thought. Her opaque, creative art and poetic, oral musings and personal missives were balanced by her clarity of written public exposition. Jack would save her words for last, and open first the package from his father. Taped to the outside of the long tube-box, with extra postage, was a letter in a square white envelope, like a greeting card. Jack dragged a fingernail through the crease of the tape and tore through the flap. The paper inside didn’t fit and was folded badly into quarters. The letter was written with blue ballpoint, in his father’s large, curled, deep-pressed, sharp-cornered European hand, on his letterhead, cheap bond half-size sheets, contracongruously offset-printed at the top in elaborate 18-pt Edwardian Script. Hoo Ha Fancy Schmantzy! Jack couldn’t help hearing. The printed memo pad stationery dismayed him. His parents were proud of the clothing business they had founded, but Jack was not proud of them for this; only for their long-past valor. The night he brought Beatrice to meet them, he had felt ashamed their lives were now so inconsequential. “It’s up to me to fulfill their potential,” he had told her. “To carry on, to make the world, and myself, always better.” She had known this was a Jewish mandate, but since he didn’t seem to, she didn’t mention it. He steadied himself and read his father’s letter.

13

Wish for Amnesia

From the Desk of Chaim T. Rubin Wholesale Transactions Ladies’ Fine Merchandise Chapter 3 Chaim’s Letter to Jack

O ctober 7, 1968 Dear Son, Your mother and I found your old telescope when we did the Passover cleaning in April, and held it for you. As you did not come to the Seders, we held on to it longer until we should see you in the summer but as you were so busy again we held on to it longer until we should see you for the High Holy Days which you again didn’t come, so and now as you must be busy again with the school I am taking the liberties with mailing to you. Please you shouldn’t think I am pushing to you for a visit you don’t welcome to make, but I see you 14

Section 1 Chapter 3: Chaim’s Letter to Jack

sometimes in the newspaper and also your dear Mother thinks you need a home-cook meal. Also about politics maybe we should have a talk. You have responsibilities to your own people but I see you go far away outside your own. What’s next? I say this what’s next to make a joke because what’s inside the package. Do you remember your very much interest in this object when you were a boy? And do you remember how it got the dent on the side which is still there and the broken lens inside which we paid money to repair but you never played with it again? I will remind you it was the evening of the summer when you were ten and we stayed for a week in the home of our friends in the country, the Schulmans. Every evening you took this out to the fields alone. One night, boys from the area came at you with what are called now “racial epithets” and also sticks and stones and you hit one of them with this object in defense of yourself. Sooner or later, once again you will have to name yourself a Jew. It will be so called for you anyway. Your Father, Papa P.S. I remind you again it cost a lot to refit the focus, so please you should look long through the lens.

15

Wish for Amnesia

Chapter 4 Six Quick Letters, Jack and Beatrice Jack got up from his desk and checked the hall. No one was out there. He locked the door and quickly lit a joint, opening the window to dispel the smoke, and grabbed one of Beatrice’s paperweights to keep the papers on the sill from blowing off. He gulped in about a third of the pot, saving the rest in a throat lozenge box in his desk drawer. He sat for a moment and stared out the window, waiting for the cannabis to take effect and release the tension in his chest. He opened the package. It was what the letter indicated: the low-quality, amateur telescope he had as a kid. He held it with amusement, twirled it like a baton, and batted it around like a weapon. “Neat,” Jack said out loud, “if I turned it up to the sky and saw God.” What did his father hope to see? 16

Section 1 Chapter 4: Six Quick Letters, Jack and Beatrice

Chava, his mother, had been disgusted with God. “On the seventh day,” Chava once said, “God rested and the Devil took over.” He aimed the telescope out the window, but saw only sky-blue, then had another thought: Bet I can watch girls on the quad! But the angle wouldn’t let him see under their miniskirts. Although he could bring some tits in pretty close. Soon bored, he replaced the toy in its wrappings and stashed the box in the corner behind the desk. If he remembered, he would take it back to the apartment. Could Jack ever be as exemplary as Chaim? He wondered about that constantly. I have joined a movement that must not fail! He was a man of his own time and country, a man of the uniting, peacemaking type, he thought. Such things as happened to his father could never happen anymore. He did recall the boyhood incident. The voices reminded him of it, too, from time to time, in their own way. He set his father’s letter under one of his lover’s paperweights. The telescope was more than an effective lance. It had awakened a sense of power. Odd that Chaim should send it now, just when Jack was adding space exploration to his interests. He glanced at the locked door and finished the joint, weighing Beatrice’s unopened letter in his hand. A blackand-white picture of her was on his desk, but it wasn’t too good. One of her students had underexposed the film by not compensating for backlight. Beatrice stood in silhouette against the Tiber River. You could see her narrow waist and long, straight hair and the shape of her dark, flowing clothes, but not her features. He inhaled the heavy musk of her stationery and hastily split her envelope with a pencil.

17

Wish for Amnesia

Dear Jack, Breeze comes from the west tonight, salty, close, from the beaches of Ostia. I feel the season hot by day and cool between my toes in evening sandals. I would like you to be with me. It would calm you here, in the dark. I dream of gestures chorused in the night, port de bras, port de bras, or sweeps and leaps extended across space as if the dancer sails or floats. I dream of hot sunsets, spiral galaxies, halls of broken mirrors. I see a fire-maker, a magician of the burning match. By day I see permuting forms. I drink, smoke, wear them, form after form awaiting conflagration. Today I consolidated two pieces under one title. Each alone has meaning but my meaning is incomplete without their polarity. Art reformulates itself continually. I can reconceive my visions until perfect. Past and Future exist only as constructs within the Present. The Present is a boundless continuum. The Present is a bridge that does not span a gap. Love, Beatrice Dear Beatrice, No, Beatrice, the present is a pretty fast thing. It’s a brief, self-bounded period. Maybe art recycles, but science evolves, and pretty quick. Every moment is discrete, yet immediately replaced by another. And every new physicality calls for immediate behavior. I heard this today at a Yippie speech: 18

Section 1 Chapter 4: Six Quick Letters, Jack and Beatrice

“History could be changed in a day. An hour. By the right action at the right time.” The past only determines the future if the present doesn’t intercede. The tiniest prick can change the world. Love, Jack Dear Jack, Well, good luck. Art is an artist’s closed system. You scientists wish containment but you’re constrained by persistent delusions. Science is immutable. Art malleable, though capricious. You would say even my soul is chemical, but it is of the finest chemistry, passed carefully mother to daughter, from Eve. Watch me make it last forever. Reality can’t be revised to match Ideal, though I will watch you try, and root for you, at least for now. Art, on the other hand, can match it; that’s what I do all day long. Love, Beatrice Dear Beatrice, We’re arrested constantly: public nuisance, loitering, disorderly conduct, trespassing, malicious mischief, disturbing the peace.... I know I’m in the right. But accusatory voices stalk me worse than cops. “Do Not Do, Think.” Sometimes I wish I could stop. But the Movement is infused with wiseacres, brats who’ d quickly step in, only to disrupt, not accomplish. I’m receiving violent personal warnings. But if I admit doubt, I’ d have to 19

Wish for Amnesia

yield to the Yippies, who forswear sensible thought for nonsensical action, and equate them. And yet, does morality really help our species develop in a positive evolutionary way? Wouldn’t morality retard it? What is right and wrong — If biologically the only right is procreation, then so base a thing as rape must be the greatest moral act! As a political activist, I serve harmony, but the bio-anthropologist in me is waging his own war, besides the raging of my own doubts regarding personal worth. Well, I was molded by a past that brought me here. For me, as a person, there’s no going back; the immediate, momentary present is the only time there is. But as for our species, the natural evolutionary process is too slow. No world will be here when our creature is complete, impossible anyway: we are evolving beings (and so’s the world). All parts evolve variously toward different ideals, some parts are still left from more primal systems. Homo futurus might not be human. There’s no way to know what’s next for all the good we will ourselves to do, and all the bad we do, we do, we do. And it goes without saying: the universe is vast. Surely we’re not the best of its creatures. I’ d like to find some good ones out there. And I do plan to search. And I expect to find some solar systems that revolve them. Love, Jack Dear Jack, Warm Christmas here. Bad traffic. Must take taxis everywhere. In taxi drivers I do trust. They alone unfailingly get me where I’m going. 20

Section 1 Chapter 4: Six Quick Letters, Jack and Beatrice

Street paparazzi bug me for pictures and autographs. My students accompany me to fend off. Some day I will lure you to Rome. Forget about other solar systems. Rome will be far enough for both of us. I’ ll come back to New York to see you in the spring. But one of these days I’ ll surely get you here to me. Love, Beatrice P.S. aka “Betty.” Some of the American kids nicknamed me. Dear Beatrice, This is my New Year! I’ve stopped eating almost completely. I’ve given away everything I can. I’m in a fast of sympathy for vegetarian apes, who would have kept this Eden-garden Earth alive if it were theirs. People amass behind me. They block regress. They expect me to lead them, so I comply. But I understand the voices now. They say I have no right to lead until I have the perfect plan. I’ve begun a study collating anthropological statistics with the human genetic code as it’s being cracked. What is the atomic Homo sapien? How does culture define itself in genes? I have shaved. I have completely shaved my head and beard. I’m glad the term is over and I’ ll see you. Love, Jack P.S. “Betty”? I could never call you that.

21

Wish for Amnesia

Chapter 5 Beatrice, Effluvia Beatrice selected a cool, cotton dress with two pockets, black. Into the right, she put a Peruvian leather pouch containing an ancient clay hash pipe and matches; into the left, went the old family housekey she carried as an amulet. Tomorrow, she would pack and return to New York for the summer. Jack would meet her plane at Kennedy Airport. Alone now, she reclined on the balcony of her apartment, staring into the night and breathing the Roman spring. She sat in blackness, still and calm, inhaling the mix of vapors flowing to her on currents warm from her perfumed doorway, hot from the courtyard garden, and cool from the nighttime sky. 22

Section 1 Chapter 5: Beatrice, Effluvia

Her room whiffed Oriental spices and hashish, Egyptian perfumes and dried flowers. On her dresser stood fine soaps and body lotions. Sachets and potpourri were tucked into the corners of shelves and drawers: each trace a perfect memory, a place, a person, circumstance. No mirrors, though, were in the room. Beatrice kept herself beautiful without them, for her private and her public self; she believed her life would have been difficult otherwise. Her grandmother had raised her in a hall of mirrors, but as time went along, few people would remember this detail of the artist’s past, and no biographer would connect it to any event of significance in anyone’s future. Beatrice’s room was, as usual, dark. Her closets would be emptied tomorrow. Most of her clothing was black, India-cotton, Egyptian cotton, or crêpe, soft and long and loose, natural black flax, rayon, flannel, cashmere, Canton silk, velour and velvet, chamois and cambric and wool. Each piece could be identified by texture, and several costumes and disguises, black and also white, were in the wardrobe.

23

Wish for Amnesia

24

Section 1 Chapter 6: Jack Meets Beatrice at Kennedy Airport

Chapter 6 Jack Meets Beatrice at Kennedy Airport Her plane arrived at Kennedy as scheduled, early

on a hot, sunny day. Beatrice waited calmly in the airconditioned terminal of TWA in an area raised above the flux of people crisscrossing near the counters. A huge bow window backlighted her in dazzling southeast rays glowing pinkly in the air, drawing color from the plush red carpet and whitewashed concrete dome walls. She stood with tranquility in that vaulted space, a Black Madonna in the Saarinen apse, the architecturally praised waiting area slightly elevated from the flow. Black from head to foot, she formed a silhouette of maximum absorbency, reflecting nothing but her race and sex. Her Bantu parentage was evident beneath her clothing. Today she was in purdah, wore a burqa, the concealing woman’s garment of the East. This clothing hid 25

Wish for Amnesia

her long, jet-black, straight hair but not her spirit force, which stood unmistakable against the light. Nor did her costume hide her blindness. She held a thin, white stick, more like a wand than a probe, and almost unneeded: her inner senses guided her through space. Immediately upon entering the terminal, Jack spotted her. He had only half-remembered her physical beauty. She was delicate and throbbing like an exquisite, winged insect. He started for her through the crowd. Beatrice felt Jack streaming toward her on the floor below. She could hear the turmoil his presence caused. The mass was rapidly parting for his wild, emaciated figure. His head and face were completely shaved and he towered very tall. He was bare-chested. He wore cheap, black plastic sunglasses, taped-together leather sandals, and a pair of grotesquely ripped and oversized dungarees held up at his waist by a rope. Everyone rushed to make way for him, as the power of his intense concentration cleaved the enormous room. But before Jack reached the waiting platform, a piercing siren blasted. Two men grabbed hold of the blind, black artist, Beatrice, just as the maniacal figure bounded within reach of her. Beatrice sensed this must be Jack, but could not be sure until she touched him or he spoke to her. She flailed out her arms for an instant of connection, and at that instant, security guards restrained them both. There was memory in her fingertips, and she heard his name surge through the crowd, “Jack Rubin!� But she was stunned by his physical changes; she still could not be certain this was her Jack: a skull, a skeleton, a rope? Her fingers did not receive the feelings they expected. She was held as Jack was arrested; both were questioned several hours, searched; Jack’s lawyers came, Peace Movement lawyers, and finally, the couple was released, exhausted. 26

Section 1 Chapter 6: Jack Meets Beatrice at Kennedy Airport

“Constant police harassment,” Jack said later, in bed in his stifling, glaucous-green apartment. The sheets had not been washed in months. Roaches ran the cupboards. Dust balls swam the floors. This is how the world should end its differences, Jack thought, in bed together, races mixing. It saddened him that Beatrice took precautions against pregnancy, or possibly was unable to bear: he would have liked a love child; she refused to discuss conception. Betty? he remembered the nickname her American students had given her, how silly. How totally opposite to her character anyone with a name like that would be. He loosened her long, heavy hair and spread it over their skins, dark and light. His hair had been as black as hers before he shaved it. His mother Chava’s hair was just like this. Beatrice felt how especially huge and hot his penis was now, attached to what had become such a bony frame. She could not sense any resemblance now between “then” (which was something in her memory as “now,” that is a “memory of then,” not really “then”) and “now,” the “now” itself. Jack’s sense of time was understood by her, although she did not share it. They lay in bed trying to relax away so long apart. She listened to him say words about his political life, each syllable filled with weariness and irony. He said depressing things about his struggle, in a voice so mellifluous there could be no doubt he’d overcome all odds, unless, she thought sadly, he were stopped violently, like other leaders of the decade. He outlined the edge of both her ears with each of his fingers in turn. Jack’s touch didn’t match her memory of it. She stroked his head and body with her hair, draping it over the palm of her hand like gauzy silk, imagining herself belonging to him again, trying to revive the twinship they had felt. His eyes were swollen and enlarged. His cheeks 27

Wish for Amnesia

twitched and ticked, his mouth was locked in an artificial grin. And he was dirty. He had sticky lines of filth in all his creases; she could roll balls of his clay in her fingers. His face was patinaed in a grime of oily sweat. His groin and armpits stank. She had to admit this to herself. What was he trying to prove? They lay in the heat of this early summer afternoon, in those charged moments of conversation before the frenzied intercourse of lovers who’ve been parted long. The now, the now of the fuck, the now of the fuck bringing everything into the present. “I would not have thought this from a Jew,” she said. What did she mean, Jack recoiled. The mayor? Beatrice was so cryptic. Words she spoke were never direct. He had said “constant police harassment,” and she said “from a Jew.” Was she trying to say, what, that Jews weren’t currently the object of harassment by American police? What did she mean “ from” a Jew? Why was she holding her nose? It wouldn’t do to ask her what she was getting at. Everyone knew Beatrice’s famous line: “There is as much effort and epiphany in the comprehension of a production as in its creation. Art and text are sanctified by their beholder.” Beatrice contended that once the effort of communication is made, and substance is carefully laid down, the rest is up to the perceiver. She maintained this about conversation, too. She was right, up to a point, but Jack found her presumption arrogant and annoying. She didn’t make it easy. Everything she said had to be considered two and three times. Every statement had to be referred back to the prior quote, or even to her unspoken thought. And she took so long in her replies. What was it she had told him about her new performance piece? The title: Oracle, Jack scoffed to himself, recalling that her sibylitic phrasing sometimes grated. 28

Section 1 Chapter 6: Jack Meets Beatrice at Kennedy Airport

Her letters at least you could read over a few times and figure out, but her laconic speech annoyed Jack, who every moment struggled with the question of whether what he said could ever be less than completely clear and unambiguous and absolutely true: if ever he might be called upon to straightforwardly articulate his principles, he could come through, he hoped. He took this hope on faith; but he knew it was a tested reality for Beatrice. It was she who could, in writing, go on developing, refining, explicating even her most subtle ideas to perfectly pin down their exact meaning forever, for any reasonable mind, even if her oral off-hands had been abstruse. The reactions of his listeners to his own halfformed thoughts, however, did amuse him: his followers concurred with every utterance, even phrases that perplexed himself. Jack participated in only one moment at a time no matter how it got to him, or how he got to it, even if he planned the route that got him there. That’s what made him quick and nimble. But whatever his groupies thought he thought, he hadn’t the slightest idea. He says something, he smiles, the listener smiles back a look of enthusiastic understanding, and cheers. The voices in his head told another story, particularly The Voice of the Petty Accuser, but no human being challenged him to that degree. The voices would not allow his mere charisma to carry the day. They taunted him to exactify his rhetoric. Jack looked over to his girlfriend, small and naked, completely fast asleep, this woman he’d waited months to make love to again, no matter how easily so many easy loves had eased under. He drifted off to sleep, unable to arouse her for another rouse. But then, while lying next to him awake an hour later, it occurred to Beatrice to introduce Jack Rubin to one of her students now home from college, by the name of Caroline Klein. 29

Wish for Amnesia

Chapter 7 Caroline Meets Letty on the Playground When Caroline was four years old, she stood with her mother one late, gray, autumn afternoon, on a chilly, dreary, earthen suburban playground in Ellenville, New York, north of the city by an hour’s bus ride few of Ellenville’s townspeople ever cared to make. Caroline was cautious, non-committal, even-tempered at this early age. She stood in a reluctant stance, a child of average build, dull, honey-colored braids plaited as tight as possible into wet hair every morning by her exacting mother, and fastened with mismatched rubber bands, no bangs. She wore a faded red and tan plaid cotton dress with white Peter Pan collar, a hand-knit brown and green sweater with front zipper and cowl, new thick maroon woolen knee sox, and old oxblood oxford shoes, Buster Browns repolished many 30

Section 1 Chapter 7: Caroline Meets Letty on the Playground

times, passed down from older cousins. New shoes were a luxury Caroline experienced only twice before her teens, and it had been white sneakers both occasions. Her face was pale and unfreckled, undimpled, unmarked. She cradled a few objects in her arms: a small brown paper bag, soft and wrinkled from re-use, but untorn and rolled at the opening; a worn Raggedy Ann doll, no dress, all joint seams resewn; a large yellow Golden Dictionary; a natural sponge trimmed to an artificial ovoid; and a tiny porcelain cup from a child’s tea set. In the brown bag were two unbroken wax crayons she had found the day before, and a Rome Beauty apple from the overhanging bough of a neighbor’s tree. The playground was dismal, almost deserted. Caroline’s mother sat on a bench with the Women’s Page of the Ellenville Press and an embroidery scissors to cut coupons and advertisements. Her fingers were darkly cracked at the tips and knuckles, the nails unpolished and broken, yellow and pellucid from detergents and harsh cleansers. The woman was thick, peasant-like, ruddy. She evaluated her only child, Caroline, standing next to her: a healthy girl, but a pest, a drain. In a few years she could get after-school jobs. I’ve started her on housework, but not without supervision, scolding, reminding and punishment. “Go play,” the mother pantomimed, pushing her daughter slightly. She didn’t like Caroline’s leaning bodily against her, to her mind one of the girl’s many bad habits. “Go play,” she repeated, now loudly. “There’s another child your age in the park.” Cary had already seen her. A plump little girl was playing recklessly on the big slide, repeatedly skidding and falling into the dirt. The girl slid, squatting, the slippery soles of her shoes skiing down the metal ramp to slam her 31

Wish for Amnesia

knees against the grit and skin her hands, her face painfully grazing the hard ground every time. Caroline saw her spit soil but get up quickly and run back to the ladder to do it again. Cary looked toward her mother for reaction. What did she think of this behavior? Didn’t she think the girl might be crazed or dangerous? No, her mother didn’t seem to think so: she was expressionless. “Go make friends,” she insisted, gesturing Caroline away in shoo-fly motions. “You don’t have any nice friends. You don’t know how to make friends.” “Will you go with me, Mommy?” Cary asked. “Go yourself,” her mother pushed. But Caroline would not. She moved closer to her mother, pressing into her broad thighs. Her mother shoved her again, not hard, but firmly. The strange girl fell once more and rubbed her hands, calling to the adult who had brought her, a teenage boy, most likely her much older brother. The boy sat on a bench near the slide, with his hands in his field-jacket pockets, laughing loudly. “Funny Letty,” he called to her, “Funny Letty.” He wiped her face, patted her, and gave her jelly beans from a cellophane package decorated with pentacles. The child’s painful practice was clearly meant for his appreciation. This was a novel idea to Cary; she eyed the sweets and wondered for a giddy moment, if she hurt herself or did a dangerous trick, would he give her some candy, too? Can I make him pat me, too? Lying on the bench next to him was a doll similar to her own, a Raggedy Ann one size larger and brighter and newer, and wearing a starched dress with bright white hearts on the belt, and a satin grosgrain ribbon still crisp in the clean, thick, red yarn hair. Cary knew it belonged to the girl on the slide. She turned away from her mother to squarely face the strangers across the yard. 32

Section 1 Chapter 7: Caroline Meets Letty on the Playground

The doll and the candy were strong inducements for her to cross the playground. Caroline placed her own things under the ladder with exaggerated care and climbed behind the chubby girl. It was a tall slide, and Letty turned around from the top to watch her. The brother increased his alertness, aware of his responsibilities, duties, his rights and the rights of others. Was his sister taking too long, maybe more than her turn, or blocking the other child? He was worried that the new girl would yell at his sister or boss her, which he didn’t like to give anyone a chance to do. “Leticia!” he called firmly. “Move over or slide down. Give the girl her turn. There are other children waiting.” Caroline and Letty both looked around, but Cary was the only other child. The boy stood up. He was tall, even when viewed from the height of the ladder. Cary turned toward his sister a few steps above herself and was surprised to see that at close range, Letty looked awful: her face was flushed, arms bruised black and blue, her thick legs badly scraped and scratched. She was wearing beautiful, new, white, patent-leather strap shoes, but look at how soiled they are! Letty wouldn’t slide. She stood intractably as Cary waited eye-level to her feet, hatching a dangerous trick she could do for the big boy herself, maybe for reward. An exciting idea: to do something in order to receive reward, not just to avoid punishment! A shiver passed through her. She’d stand at the top, let go of the rail, lift her dress over her head and slide fast. She tried to pass Letty as politely as possible, nudging her gently to the side with her feet. “You’ve been sliding all day, Leticia,” the boy called again, alarmed by Caroline’s little kicks of his sister; but the effect of his words was only to rivet the child more staunchly. 33

Wish for Amnesia

As is characteristic of many children her age, she responded to her brother with the action his words cued, no matter how far off the ball the were. Letty hadn’t been deliberately blocking Caroline until he said he thought she was: she’d merely been intently watching her; but now she had the fine idea to thwart the other child, stir things up. The boy yelled again, his hands on his hips, annoyed. He wasn’t talented at making Letty mind. Caroline could read his gestures well; she must do her trick quickly before the situation changed and her opportunity was lost. She inched her feet against the stubborn girl again, and thought up another stunt even more daring. She would stand on one leg without holding, and jump to a sitting position. Turning her head to check, she saw her mother absorbed in the paper. Tricks were not something her mother approved of. But turning back, she felt the teenager stomping up the ladder behind her. There wouldn’t be much time to show off for him. She whined with disappointment, and to focus him. “Watch me?” she wheedled. Their eyes met and he smiled. It was a genuine smile, and surprised her. “Just a sec.” He climbed up the rest of the way, his feet clanging and scraping on the metal rungs, the flimsy structure shaking under his added weight. As he passed to grab his sister, he reached around Caroline, like a hug. She liked the feeling. “Excuse me, honey.” Letty howled, jealous of her brother’s courtesy toward the intruder. The boy took no particular interest in Caroline, his was simply a common endearment; he was no pedophile. But spurred by Letty’s yell, Caroline released 34

Section 1 Chapter 7: Caroline Meets Letty on the Playground

herself into his arms in a fit of giggles. Unprepared, he almost lost his balance. When Letty screamed, he fueled her fury by teasing, mistakenly thinking it would teach her a lesson; that is, teach her the lesson he meant to teach her, not the sadder, meaner lessons a person learns by being teased. He played along with Caroline, cuddling her and sticking out his tongue. Letty vengefully pushed into them both. They were in a dangerous spot, all three at the top of the slide, but the boy recalled his responsibilities and sobered. Not wanting to have to call the mother over, he sat Caroline down carefully in front of his sister and curled her fingers around the cold, metal, rolled handrails. “Please slide,” he said to her. He had no way of knowing she had planned to do tricks for him. Letty was roaring. Cary still hoped the boy would go sit and watch. She waited another minute while he held his squealing charge, as he looked at her nicely with a frank and casual patience she wasn’t used to. She saw a Jewish star around his neck. She had one too, but her mother insisted she wear it hidden; Caroline thought they were supposed to be worn hidden. Her boldness shrank fast: there were few Jewish families besides her own living in this town, and she had been well instructed early on not to advertise her Jewishness. She was astonished to see the star worn openly, especially by a teenage boy. Didn’t the other boys fight him? Once she had seen garbage flung at a boy who forgot to remove his yarmulke skullcap after a holiday observance, and periodic incidents were not uncommon. But even at this age, Cary knew her family involved themselves in religion as little as possible, maybe an odd word here and there. They went to a service once or twice a year, maybe. Frightened and confused, she slid away. Landing easily upright, she quickly 35

Wish for Amnesia

gathered her sponge and her toys and ran to her mother, not looking at the boy and girl staring after her, and not knowing why she felt ashamed. “What happened?” her mother asked, and then answered herself with an erroneous assumption. “The girl was afraid to slide down? Not you. You are a big, brave child.” How could her mother think Letty had been afraid: hadn’t she seen her? Hadn’t she been looking straight at Letty’s daring-do’s? Her mother’s inconsistent reactions were often a puzzle. “Is Raggedy Ann Jewish?” Cary asked. Her mother heaved an exasperated sigh. “Sit down,” she said. She’d have to enroll her in Sunday School, then maybe Hebrew School a few afternoons a week. She couldn’t answer this sort of question. Caroline knelt on the barren earth and rested her head in her mother’s lap, which sometimes this stern woman permitted her to do. Cary loved to feel close and warm and safe and soft. She thought of the big boy smiling at her, touching her, and calling her “honey.” She watched the weak sun lift off the ground and slice patches across the playground’s barren tree trunks. She burrowed her head into the nest of her mother’s warm lap, smelling the mysterious odors. “Please,” her mother hissed sharply, twisting the child’s arm to make her stand. “You’re embarrassing me!” Caroline sat down on the bench fast and hard. “Eat your apple,” said her mother, opening another section of the newspaper, licking her fingers to turn the page. She would not look at Caroline, angry that the child had to be reminded of all the same things all the time. “Color with your crayons,” the woman went on. “Keep yourself busy. Stay inside the lines.” 36

Section 1 Chapter 7: Caroline Meets Letty on the Playground

Caroline watched Letitia and her brother gather their toys to go home, Letty darting off ahead, the brother calling after her, “Hey, this is yours, too, baby!” He was mischievously gesturing to a little black cape by his side. Letty would be going as a witch for Halloween. “Oh, yeah!” she laughed, and ran back for the costume. It was a Christian holiday, All Hallow’s Eve, and the few Jews there were in Ellenville didn’t let their children trick or treat, but the Schwartzweiss family made an exception in Letty’s case, with her brother to accompany her everywhere. But Caroline noticed that they did forget the starry candy wrapper on the bench. Cary would never do that: it had been drummed into her that leaving trash was an insolent, spoiled act. Her mother almost delighted in pointing out littering by transgressors from all classes and professions. Cary was taught to always check back behind her. When they reached the gate, Letty turned abruptly and fluttered her little cape. Then she jerked her new doll up and down. Caroline tried to read the gesture but could not. Was it a wave or a taunt? She raised her own doll slightly in return, but Letty did not signal again, grabbing and slamming the gate instead, causing it to crash and rebound open. The chill in the air was insistent this late in the afternoon. Caroline hugged her raggedy Raggedy, as the curious playmate and kind brother receded along the path. When they were out of sight, she finished her apple, including the core as she’d been taught, and tossed the pits over the fence to grow apple trees if they would. Then she crossed the playground to get the empty candy bag, and inhaled its sticky aromas before dropping it into a dented, galvanized barrel near the gate. She carefully colored the 37

Wish for Amnesia

lady in the coloring book, with the two crayons she had found: green for the lady’s coat, red for the dress. Her mother folded the paper, putting a few of the clippings into her upholstery-fabric purse, but changed her mind about some of the others, and threw them out. Playgrounds made her uneasy when the sun went down: to get her home early, her own mother had told her that ghosts of dead children came to play at dusk. She didn’t remember having been told this, but when these afternoons drew in she felt their presence, with dread but without pity. “That girl had a new Raggedy Ann,” Caroline said as they left. “Be grateful you have one at all,” came the reply. “They’re Jewish,” Caroline continued, referring to the boy and girl, still not sure about the dolls, as she followed her mother toward the street. “Let’s stop at Corso’s Market on the way home,” the woman said, not paying her any attention. “Canned peas nineteen cents on special.” They walked out of the playground towards home as the lamplights began to come on, splatting harsh, white triangles far apart. Along the streets of Ellenville were crooked rows of mismatched houses set among vacant lots, and wild trees, and patchy yards, and jumbled gates enclosing barking dogs, and broken crates, and chipped white plaster saints in delft blue niches. Her mother pointed toward a particularly derelict property containing a rotting house and outbuildings attached in series, constructed by a prosperous farm family a century ago. In the sing-song custom of the neighborhood, they ticked off the sections together, “Big house, little house, back house, barn.”

38

Section 1 Chapter 8: Letty’s Mother Dying

Chapter 8 Letty’s Mother Dying When the girls were ten, Caroline watched her friend’s mother from the doorway of the woman’s sickroom. Letty’s mom was too weak to get out of bed. She breathed in tiny pants and could hardly speak. Her skin was already dead white, yellow-gray waxen white, hideously made up with rouge circles and lipstick applied in a cupid’s bow. Her ear lobes were bloodless, dry callous. Her hands were transparent knobby claws with red nail polish badly painted over horny, flaking cuticles and riven fingertips. Her hair had fallen out too, but she tried, every day, to tie on a bright kerchief when Letitia brought Caroline home to play and do homework after school. She could hardly lift her eyeglasses off the night table to put them on. A living corpse, age thirty-eight. 39

Wish for Amnesia

Letty stomped through into the malodorous bathroom to wash her hands and face before she came near her mother, so Caroline visited first, from the doorway of the bedroom to keep her own germs away. Cary’s eyes darted to the dresser, bull’s eyeing the photograph of Letty’s brother, by this date in 1957 an early casualty of American skirmishes in Southeast Asia, what was the country — Laos. Caroline stared at the pinkish picture of him in khaki uniform. Bitterness rose in her, as always when she saw it. She had never been able to make him notice her, hadn’t grown up enough; none of her juvenile advances had clued him in. She was too young to know of course they did, but he had chosen prudently to ignore her flirtations — although maybe, underneath it all, as Letty resentfully suspected in the prescient ways of a despairing child, they had influenced his decision to go to war. His Colt model 1911, 45 caliber, semi auto service pistol had been shined up to send home to his family with his effects, and it was right here in that drawer. “How you feeling today, Mrs. S.?” Cary asked. “Regards to Mother,” croaked the cancerous woman, bending her wrist open-close, one-two, weaker and looser than the day before, thin flags of flesh hanging from the bones of her arm. Letty returned from washing up and tossed her mother’s cigarettes on the foot of the bed, Lucky Strike. They bounced to the floor and spilled. Letty blew on one, announcing “clean enough!” and placed the end into her mother’s mouth. She lit it for her, coordinating the flash of the lighter with the dying woman’s efforts to inhale. Then she pulled the cigarette back out, flicked it once into a handblown Murano ash tray, and replaced it between the reaching lips. Letitia was polite with her mother, but 40

Section 1 Chapter 8: Letty’s Mother Dying

Caroline noticed that, almost spitefully, she made her smoke too fast, each puff a gasp. An oxygen tank and apparatus stood near the bed. Letty had been taught to be careful about fire. It was the doctor’s policy to let his patients smoke until the end if they wanted. Caroline sat herself gingerly down on a beautifully designed and crafted, comfortable, Charles Eames wooden chair near the door. The bedroom set in this house was expensive, lacquered, sweet blond wood, with chips in the footboard from Letty’s baby teeth, tender gouges pointed out to Cary many times, “It’s a Herman Miller footboard I chewed up,” Letty liked to taunt, “moolah, moolah.” The house was brick; Caroline’s was aluminum-sided wood frame, with iron bedsteads. This was one of the best houses on one of the best streets in town. A huge palo santo bush blossomed hot pink on a manicured Merion-bluegrass sod front lawn. Letty’s family had more money than hers; the father was a banker. Letty was given piano lessons and skating lessons and went to arty summer camps, advantages Caroline thought were wasted on her overweight, untalented and inappreciative friend. Letty helped her mother smoke. There was no conversation once the cigarette was lit. And when the woman recovered from her fit of coughing, Letty brought her mother’s pocketbook to the bed and opened a satin, snaptop change purse. The mother took the soft thing into her own ruined hands, and with tweezer fingers lifted out some coins for Letty and for Caroline. She smiled best she could to them, her soul behind her burning eyes, heart bursting from her wracking chest, her face cascading torrents when the door closed. So Caroline and Letitia went for ice cream, and Letty bought Bazooka and more candy; she got fatter every week. 41

Wish for Amnesia

Caroline had never genuinely liked Letitia. They regularly bickered. Letty started fights with everyone. Other children heckled Cary for being with her, and wouldn’t play with either girl. Caroline bought chalk or paper or scissors, never sweets, as if in reproach. Cary liked sugar as much as any child, but in this circumstance she spited and denied herself as an example. And Letty ate more than she might have, had she not had her friend’s behavior to resent. Thus, the twisted patterns of their friendship were laid down, and elements of their personalities first set.

42

Section 1 Chapter 9: Caroline and Letty, Carmine Street Pool

Chapter 9 Caroline and Letty, Carmine Street Pool When

Caroline came home from college after doing well on an art department scholarship complete with year abroad, she looked up Leticia Sparafusil, neÊ Schwartzweiss, in the Manhattan telephone book. Letty had married someone, a foreign merchant marine, well beneath her family’s taste, income and education, and was living in New York. The girls arranged, after many postponements and phone calls because Caroline was trying to make all her city visits in one day, to meet for a swim at the Carmine Street Pool: the perfect thing. In high school they had enjoyed themselves as rival swimmers, Letty despite her weight, although neither had been the best, or even among the best, in their class. 43

Wish for Amnesia