The Official Publication of the National Defense Transportation Association February 2023 www.ndtahq.com Overcoming Challenges The State of the Defense Industrial Base

February 2023 • Vol 79, No. 1

PUBLISHER

VADM William A. Brown, USN (Ret.)

MANAGING EDITOR Sharon Lo | slo@cjp.com

CIRCULATION MANAGER

Leah Ashe | leah@ndtahq.com

PUBLISHING OFFICE NDTA

50 South Pickett Street, Suite 220 Alexandria, VA 22304-7296 703-751-5011 • F 703-823-8761

GRAPHIC DESIGN & PRODUCTION MANAGER

Debbie Bretches

ADVERTISING SALES DIRECTOR

Bob Schotta bschotta@cjp.com

ADVERTISING & PRODUCTION

Carden Jennings Publishing Co., Ltd. Custom Publishing Division

375 Greenbrier Drive, Suite 100 Charlottesville, VA 22901 434-817-2000 x330 • F 434-817-2020

Defense Transportation Journal (ISSN 0011-7625) is published bimonthly by the National Defense Transportation Association (NDTA), a non-profit research and educational organization; 50 South Pickett Street, Suite 220, Alexandria, VA 22304-7296, 703-751-5011. Copyright by NDTA. Periodicals postage paid at Alexandria, Virginia, and at additional mailing offices.

SUBSCRIPTION RATES: One year (six issues) $40. Two years, $60. Three years, $75. To foreign post offices, $45. Single copies, $6 plus postage. The DTJ is free to members. For details on membership, visit www.ndtahq.com.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to:

Defense Transportation Journal 50 South Pickett Street, Suite 220 Alexandria, VA 22304-7296

www.ndtahq.com | 3 February 2023

FEATURES BUILDING SUPPLY CHAIN RESILIENCE 7 By Emily Harding and Harshana Ghoorhoo IMPACT OF CONSTRAINED LITHIUM SUPPLY 12 TO THE US DEFENSE INDUSTRIAL BASE By Lt Col Paul Frantz, USAF DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE STRATEGY AIMS 18 TO SUPPORT CRITICAL FACET OF DEFENSE INDUSTRIAL BASE BRINGING MANUFACTURING BACK TO THE US 22 REQUIRES POLITICAL WILL, BUT SUCCESS HINGES ON TRAINING AMERICAN WORKERS By Amitrajeet A. Batabyal FORTHCOMING RULES WILL NECESSITATE 26 CLIMATE REPORTING AND SUPPLIER VISIBILITY ACROSS THE SUPPLY CHAIN By Sharon Lo DEPARTMENTS NDTA FOUNDATION HALL OF FAME ..................................................................................... 4 PRESIDENT’S CORNER | VADM William A. Brown, USN (Ret.) ................................................ 5 CHAIRMAN’S CIRCLE ........................................................................................................... 28 HONOR ROLL 29 INDEX OF ADVERTISERS 30 We encourage contributions to the DTJ and our website. To submit an article or story idea, please see our guidelines at www.ndtahq.com/media-and-publications/submitting-articles/. SIGNUP TODAY www.ndtahq.com/the-source The Source NDTA’sOfficialNewsletter toAddpublications@ndtahq youremailaddressbook

NDTA Headquarters Staff

VADM William A. Brown, USN (Ret.) President & CEO

COL Craig Hymes, USA (Ret.)

Senior VP Operations

Claudia Ernst Director, Finance and Accounting

Lee Matthews

VP Marketing and Corporate Development

Jennifer Reed Operations Manager

Leah Ashe

Membership Manager

Rebecca Jones

Executive Assistant to the President & CEO

For a listing of current Committee Chairpersons, Government Liaisons, and Chapter & Regional Presidents, please visit the Association website at www.ndtahq.com.

NDTA FOUNDATION HALL OF FAME

The National Defense Transportation Association Foundation recognizes our most special donors for their gracious financial support to academic scholarships supporting our future logistics and transportation leaders.

VISIONARY SOCIETY

Contribution over $100K

EDITORIAL OBJECTIVES

The editorial objectives of the Defense Transportation Journal are to advance knowledge and science in defense logistics and transportation and the partnership between the commercial transportation industry and the government transporter. DTJ stimulates thought and effort in the areas of defense transportation, logistics, and distribution by providing readers with:

• News and information about defense logistics and transportation issues

• New theories or techniques

• Information on research programs

• Creative views and syntheses of new concepts

• Articles in subject areas that have significant current impact on thought and practice in defense logistics and transportation

• Reports on NDTA Chapters

EDITORIAL POLICY

The Defense Transportation Journal is designed as a forum for current research, opinion, and identification of trends in defense transportation and logistics. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily of the Editors, the Editorial Review Board, or NDTA.

EDITORIAL CONTENT

Archives are available to members on www.ndtahq.com.

Sharon Lo, Managing Editor, DTJ NDTA

50 South Pickett Street, Suite 220 Alexandria, VA 22304-7296 703-751-5011 • F 703-823-8761 slo@cjp.com

TRAILBLAZER SOCIETY

Contribution $50K - $99,999

PATHFINDER SOCIETY

Contribution $25K - $49,999

As the Foundation is funded by voluntary donations, with your support, the Foundation will be empowered to help students for decades to come. Please consider making a tax-deductible contribution to help our future professionals have a future. Visit https://www.ndtahq.com/foundation/ to find out more.

4 | Defense Transportation Journal | FEBRUARY 2023

FOUNDATION

PRESIDENT’S CORNER

Remaining Up to the Challenge

VADM William A. Brown, USN (Ret.)

NDTA President & CEO

Dear NDTA Teammates,

As we are already a few months into 2023, it looks to be a challenging year— we are up to it! The war in Ukraine has passed the one-year mark (24 Feb 2023) and finding a short-term solution to end what has become known as, “Putin’s war of choice,” is unlikely. Meanwhile, the US has continued to supply Ukrainian forces and NDTA members in uniform and in industry have continued to deliver across challenging lanes. Per US Transportation Command (USTRANSCOM), there have been approximately 1,000 combined

military and commercial flights, 60 maritime vessel movements, and many times more rail and truck movements providing aid worth over $27 billion in support of European allies and partners. The center of effort for US support continues to be training support to Ukraine—and equipment. As usual, things are busy. This is expected to remain the case throughout 2023. On top of this, our thoughts and prayers go out to the victims of the Türkiye/Syria earthquake.

Inflation continues to be a top concern for shippers, logistics and transportation providers, as well as the cost of capital as

as of February 17, 2023

CHAIRMAN’S CIRCLE

• The Pasha Group (upgrade)

PRESIDENT’S CIRCLE

• Sonesta International Hotels Corporation

SUSTAINING

• All Aboard America Holdings

• Holland & Knight

• Signature Transportation Group

• Smith Currie & Hancock LLP

interest rates have risen. Meanwhile, our Nation’s much needed focus on the Industrial Base continues to take shape as more and more questions beget actions to ensure we are not reliant on hostile actors for critical support items—material,

See Pres. Corner pg. 30

SURFACE FORCE PROJECTION CONFERENCE

May 15-18, 2023

Christopher Newport University, Newport News, VA

REGISTER TODAY! www.ndtahq.com/events/ports-conference/

This conference focuses on the challenges associated with deploying large military organizations through the U.S. strategic seaports, via surface transportation, while integrating and adapting to contend with the contested environment of today and tomorrow.

Join the National Defense Transportation Association (NDTA) and Christopher Newport University’s Center for American Studies (CAS) along with

the NDTA Surface Committee and Ports Subcommittee as we team with USTRANSCOM’s Military Surface Deployment and Distribution Command (SDDC), U.S. Department of Transportation’s Maritime Administration (MARAD), commercial industry and academia to find creative and innovative ways to improve deployment readiness, solve challenges and improve U.S. ability and capability to respond and operate in a global, multidomain, and contested environment.

www.ndtahq.com | 5

NEW CORPORATE MEMBERS

WELCOME

“Achieving Surface Deployment at the Speed of War: Supporting Large Scale Operations”

6 | Defense Transportation Journal | FEBRUARY 2023 WE CARRY THE THINGS THAT CARRY THE WORLD FORWARD

crowley.com/solutions

When you need a partner to solve your biggest problems, before they are your biggest problems.

Building Supply Chain Resilience

By Emily Harding, Deputy Director & Senior Fellow, International Security Program, Center for Strategic & International Studies, and Harshana Ghoorhoo, Research Assistant, International Security Program, Center for Strategic & International Studies

www.ndtahq.com | 7

In late 2021, global supply chains were stretched to breaking point. A British parliamentary committee found that an average of one in six adults in Great Britain experienced essential food shortages in late October and 37 percent struggled to get fuel. Two months earlier, a survey found that business stock levels were the lowest they had been since 1983.

Around the same time, the port of Los Angeles was in the middle of a crisis. Ships were lined up for miles, unable to move products through the bottleneck at the port. The port’s executive director said the port had the capability to run 24 hours a day, but a shortage of truck drivers and nighttime warehouse workers prevented a nonstop schedule. He cited the tremendous challenge of getting “this entire orchestra of supply chain players to get on the same calendar.”

The Covid-19 pandemic brought the fragility of global supply chains into stark relief. A complex system of producers and suppliers collapsed under the weight of high demand, just-in-time delivery, workforce shortages, and low supply. Producers overindexed on efficiency in production and did not build enough buffer to anticipate disrupted global trade. Even the defense industrial base was not able to withstand the shocks. The Ukraine war exacerbated the situation, highlighting single-threaded suppliers and foreign control of key elements.

Shocks will never be completely foreseeable or preventable. Instead, government and industry should focus on resilience, or maximizing quick recovery from disruptions. The White House’s Executive Order on Supply Chain Security (EO 14107) said “more resilient supply chains are secure and diverse—facilitating greater domestic production, a range of supply, built-in redundancies, adequate stockpiles, safe and secure digital networks, and a world-class American manufacturing base and workforce.” In operational terms, a resilient supply chain identifies critical nodes, anticipates likely disruptions to minimize strategic surprise, creates buffers

or alternatives for those nodes, and adjusts to recover quickly from a disruption.

SUPPLY CHAIN CHALLENGES

A supply chain crisis is not any one problem; instead, it results from a combination of poor visibility that hampers planning, a narrowing of a pipeline that creates focused risk, and then a shock that throws the system off the rails.

Poor Visibility into a Deep Supply Chain

Visibility risk is at the core of supply chain vulnerability. Without complete insight into the spreading web of suppliers, there is always a risk that an unforeseen disruption will derail production. However,

Shocks will never be completely foreseeable or preventable. Instead, government and industry should focus on resilience, or maximizing quick recovery from disruptions.

modern supply chains have so many layers that constrained time and research resources prevent full visibility.

Prime suppliers often trust that their subcontractors are monitoring their own supply chain, when sometimes critical components slip through the cracks. Companies may not know when an adversary or competitor acquires a sub-subcontractor, or the chain of custody for a critical widget might be obscured. The Department of Defense (DOD) suffers from this problem much like any other consumer. DOD relies on contracts with prime contractors and expects those primes to manage their own supply chains, but too often that has proven to be a misplaced trust.

While DOD once conducted its own supply chain security evaluations, that capability has atrophied over time as

Congress sought to shift the burden onto contractors to verify their own work. As a result, DOD officials are now grappling with how to evaluate layered risk. One interviewee said that there are excellent software tools that can map the many layers of the supply chain, but none of those tools describe the capacity of production within each production line or identify which systems use the same sub-tier suppliers. In other words, if Prime Contractor A understands their supply chain, and Prime Contractor B understands their supply chain, but A and B are unaware they are both drawing on Subcontractor C, the capacity and resilience of the supply chain is actually more fragile than A and B might assume.

Rules designed to protect proprietary information also contribute to blind spots in the supply chain, according to our interviews. Each prime should rightfully expect their intellectual property (IP) to be protected, but that protection obscures information relevant for risk assessments and restricts some data from access. For example, to populate supply chain management tools, DOD needs to get approval from each contractor to access proprietary data. Further, DOD cannot use contractors to pull together this data, because that might open the door to industrial espionage, leading to workforce shortages.

Narrow Pipeline Creates Focused Risk

Focused risk happens when a supply chain narrows to a single source or single location that can be disabled by a shock event. For example, a critical facility or transportation route could be in the path of a tsunami, terrorist violence could imperil a key rail line, political instability could displace a workforce, or a public health emergency could lead to an extended lockdown.

Foreign dependence aggravates focused risk in supply chains, with Taiwan’s nearmonopoly on advanced semiconductors being a prime example of concentrated risk. A conflict over Taiwan would cut off

8 | Defense Transportation Journal | FEBRUARY 2023

global access to about 90 percent of highend semiconductors. Any conflict in the Pacific would lead to massive disruptions to a range of supplies; China controls 87 percent of the market for permanent magnets, which are used in the manufacturing of electric vehicle motors, electronics, wind turbines, and defense systems. The United States is still dependent on China

for rare earth and other minerals, critical to goods from consumer electronics to weapons systems.

Shocks Happen

The diagram above is far from a comprehensive list of shocks, but it illustrates some of the most common causes for supply chain disruptions.

GETTING TO TRUE RESILIENCE

A mindset of resilience means assuming disruptions will occur and planning for a rapid recovery to acceptable functionality.

Entities should approach resilience in three steps: First, improve visibility to minimize blind spots in the supply chain. Second, identify potential shocks and evaluate which ones are most likely and most

www.ndtahq.com | 9

disruptive. Third, create contingency plans and buffers for the most critical, vulnerable portions of the supply chain.

Step 1: Improve Visibility to Minimize Surprise.

Maximizing visibility into supply chains should always be the goal. The DOD should step up its staff resources to improve visibility into critical defense supply chains. Further, this staff should build resilience by identifying gaps and working to match those gaps to nontraditional suppliers.

When engaging in evaluation of supply chains, entities should put a premium on constructing a diverse team of analysts. Geographic diversity, socioeconomic diversity, and racial and gender diversity on a team can contribute to fewer blind spots. For example, a person whose family includes truck drivers and Midwesterners might understand transportation during extreme weather better than most. Immigrants and children of immigrants might provide critical insights into seasonal labor concerns and visa challenges. Assembling a team that represents a diverse set of disciplines has repeatedly been shown to result in better outcomes.

Entities should focus on predicting and extending the lifespan of critical components to minimize urgent need. “Digital twins”—or virtual representations of realworld objects that mirror the environment and stresses on the object—are increasingly becoming the go-to industrial approach to accurately predict the operational lifespan of products to anticipate the demand cycle.

Step 2: Identify Potentials Shocks. Entities should identify single points of failure or places where the supply chain narrows to criticality. Evaluating each critical piece for threats, like risk of environmental shock or workforce scarcity, in a rigorous way can then inform scenarios analysis and crisis production plans. Part of that rigor is a diverse team doing the analysis.

The US Government has a role to play both anticipating potential security shocks and facilitating information sharing. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States needs to keep evolving to identify potential threats early and create a robust support structure for industry. Further, the United States should use existing regulatory authorities and industry groups

to encourage critical infrastructure providers to conduct an in-depth, rigorous analysis of potential shocks to their systems and the challenges for recovery.

Creating a diverse workforce and talent pipeline can insulate against labor shifts. The DOD has attempted to create geographic diversity in its pipeline, and industry is working on ways to cultivate both a cleared and uncleared workforce for added diversity. Getting a security clearance can be time consuming and a large hurdle, eliminating some potentially talented candidates who could contribute at the unclassified level. The creation of apprenticeships and embedded trade schools can also facilitate a strong pipeline of certain key skills. Some entities are creating intentional pathways to underserved communities, like the National-Geospatial Intelligence Agency’s initiatives to collaborate with the local community surrounding its new facility in North St. Louis.

Step 3: Create Buffers and Contingencies.

The simple act of rigorous evaluation and contingency planning can lay bare a previously unconsidered problem. Taking the next step to create buffers for key nodes in a supply chain can shift an event from a catastrophic shock into a temporary disruption.

DIGITAL SEED BANK

A database of information, which one participant described as a public-private digital seed bank, could stockpile plans for creating critical components. In a crisis, when current supplies cannot meet sudden and urgent demand, the government can match those plans with companies who might be well suited to shift production lines to meet the dire need. Critically, participating companies would need reassurances about protection of IP or compensation for its use.

VENDOR DIVERSIFICATION

A vendor chain that builds in diversity will more effectively create resilience.

10 | Defense Transportation Journal | FEBRUARY 2023

Containers are stacked on a ship at dock in the Port of Los Angeles. From mid-2021 into 2022, the port experienced a crisis with ships lined up for miles, unable to move products through the bottleneck at the port.

Photo courtesy the Port of Los Angeles.

Vendors that cover several geographic areas are insulated against environmental or security shocks; vendors that represent a variety of backgrounds and experiences will be better able to identify and anticipate developments. Entities should place a high value on a diverse supply chain as a hedge against shocks. DOD is already working to bring in new entrants to the DOD contracting market to improve diversity and innovation, but more can be done. For example, DOD’s strict requirements and complicated contracting processes can be a barrier to entry for smaller businesses, so elements of the department are working with potential contractors to discover the biggest cost drivers and adjust or eliminate them. Since the economic incentives that pushed production of key parts overseas still exist, DOD is also looking for ways to incentivize onshoring or friend-shoring using existing regulatory authority.

STRATEGIC STOCKPILING

While big pieces of equipment are impractical to stockpile, the most critical, or most likely to break, components of those pieces could be stored. For example, rather than store an entire generator, utilities can store the elements of their existing generators that are most prone to failure. Additive manufacturing can be a flexible and costeffective alternative for some parts, providing a bridge capacity for creating those critical parts until regular supply chain mechanisms have recovered.

CREATE A DIVERSIFIED WORKFORCE PIPELINE

Government should create a national imperative for bolstering industrial skills, such as encouraging trade apprenticeships; Industry could partner with unions, which have proven proficient at retraining and upskilling. In order to sustain their diversified workforce, companies also need to take steps to promote inclusivity. Social inequalities present an underlying challenge both to creating a robust pipeline into the

defense industry and to growing a diverse array of potential suppliers.

NEARSHORING AND FRIENDSHORING

Companies should carefully evaluate which key parts need to be located within friendly territory, for reasons ranging from counterintelligence concerns to human rights violations to a dependable justice system for resolving disputes. Coordinating with allies and partners for secure manufacturing of precursors is critical. The G7 could be a vehicle for this coordination, given its flexibility, decades of experience working through economic challenges, inclusion of key US allies, and high-level coordination mechanisms. As one workshop participant said, “The challenge in operational resilience is fundamentally an international game.”

CONCLUSION

As the conversation on supply chains builds renewed urgency, EO 14017 has laid a sol-

id foundation for continued steps toward resilience. The 100-day follow-on report to EO 14017 said “America’s approach to resilient supply chains must build on our nation’s greatest strengths—our unrivaled innovation ecosystem, our people, our vast ethnic, racial, and regional diversity, our small and medium-sized businesses, and our strong relationships with allies and partners who share our values.” Innovation drawing on these strengths is the surest path to true resilience. DTJ

This commentary was produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

The Department of Defense completed a one-year assessment of supply chains in the defense industrial base (DIB), in response to President Biden’s February 2021 Executive Order (E.O.) 14017. The report provides a strategic assessment of five critical supply chain areas: Kinetic capabilities, energy storage and batteries, castings and forgings, microelectronics, and strategic and critical materials. The report also identifies four strategic enablers which underpin the four key focus areas: workforce, cyber posture, manufacturing, and small business. Graphic and information by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Industrial Base Policy.

Impact of Constrained Lithium Supply to the US Defense Industrial Base

By Lt Col Paul Frantz, USAF, Student, Seminar 13, The Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy, National Defense University

By Lt Col Paul Frantz, USAF, Student, Seminar 13, The Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy, National Defense University

in

paper

of the

not

the official policy

position

of

the US

The views expressed

this

are those

author and do

reflect

or

of the National Defense University, the Department

Defense, or

Government.

IMPACT OF CONSTRAINED LITHIUM SUPPLY TO THE US DEFENSE INDUSTRIAL BASE

Over the last twenty years, lithium (periodic symbol: Li) has evolved into a critical material for the US Defense Industrial Base (DIB). Uses for lithium within the DIB and the US economy continue to expand. The increasing reliance on lithium is readily apparent to casual observers. However, the fragility of the world’s lithium supply chain remains more challenging to perceive. Over the last decade, the lithium supply has lagged behind demand across the market. With regard to national security, how lithium limits the surge capacity of the DIB is particularly concerning. The negative impact on the DIB’s surge capacity is not a forecasted problem; instead, it is a present and worsening problem. Policymakers should view risk to the DIB and national security as unacceptable. US policies and corresponding strategies must quickly evolve to address the ongoing and projected challenge to the lithium supply chain and the associated negative impact on DIB surge capacity.

BACKGROUND – WHAT LITHIUM IS / HOW IT WORKS / SUPPLY CHAIN HISTORY

Scientists identified lithium as a distinct alkali metal element in the year 1817. However, the use of the new metal proved difficult as it did not respond to conventional electrolysis—the process used to isolate and separate some metal elements found in the natural environment.1 It was not until the latter half of the nineteenth century that scientists were able to isolate lithium through extreme heating paired with electrolysis.2 From this point forward, lithium received use in a wide range of applications—most of which have emerged in the postindustrial era.

www.ndtahq.com | 13

Figure 1. Lithium supply and demand disconnect.5

Figure 2. Lithium price in China from January 2017 through March 2022.7

Lithium’s innate resistance to regular electrolysis remains key to the material’s usefulness. At room temperature, lithium is stable and does not easily break down when exposed to a sustained electrical charge. Lithium is also much lighter than most alkali metals. The combined features of resistance to deterioration, conductivity, and low weight relative to mass have made lithium an attractive material for batteries.

As uses for lithium expanded during the twentieth century, supply generally kept pace. However, lithium’s supply and demand profile evolved in the twenty-first century. Demand has increased exponentially with improved battery technology and expanded product applications, including significant growth in telecommunications, transportation, and power storage.

Various forms of lithium receive use across a wide range of commercial applications, including high-end manufacturing alloys, medicine, ceramics, and air conditioning.3 However, over the last fifteen years, batteries have consumed most of the world’s lithium supply. Presently, battery production consumes 65% of the lithium market, with most production occurring in China. The balance of raw lithium usage spreads across the following sectors: ceramics and glass – 18%, lubricating greases – 5%, polymer production – 3%, continuous casting mold flux powders – 3%, air conditioning equipment – 1%, small scale/niche uses – 5%.4 Global demand for lithium remains on track for tremendous growth in the coming years. The next three to five years, in particular, promise to be especially challenging.

The chart at figure 1 depicts the severity of the lithium supply problem. The black line within the chart depicts current and forecasted market demand. Yellow bars speak to proven production, while blue depicts additional forecasted production. The shades of blue indicate degrees of risk – dark blue bars have solid footing, while lighter shades of blue indicate increased risk concerning production and availability.

Until recently, lithium production has kept pace with rapidly expanding demand in the market. However, due to COVID-19 related impacts on market behavior, lithium supply temporarily surpassed demand—this resulted in a tapering of global production, a dramatic price drop, and a (false) sense of confidence. The surplus lithium supply has now been exhausted, and production has not ramped up sufficiently to meet current demand. The spot price for lithium is now at an alltime high and almost 500% higher than last year. The present problem is challenging enough, but it pales compared to projected supply problems over the next three to five years. Furthermore, problems over the next ten to fifteen years may prove disastrous without change across the market.

The chart at figure 2 depicts the Chinese market price of lithium over the last five years. The chart is depicted in Yuan as most lithium component manufacturing occurs in China.6

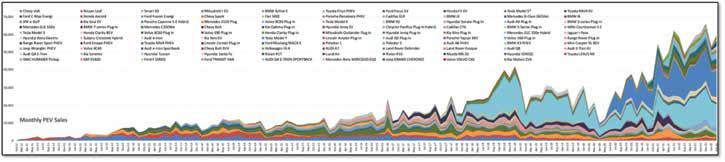

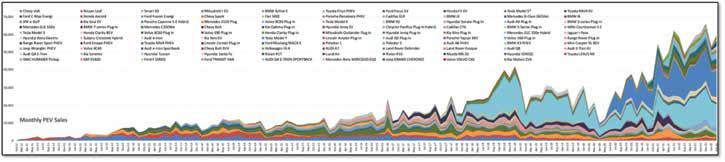

Over the last decade, especially in the last five years, commercial sector demand for lithium has advanced primarily through global Electric Vehicle (EV) sales. Figure 3 depicts global EV sales through

the last ten years. Despite the challenges of the COVID-19 global pandemic, 2021 proved to be a banner year for the electric auto industry.

LITHIUM AND THE DEFENSE INDUSTRIAL BASE

As with commercial demand, defenserelated lithium requirements have steadily increased over the last twenty years. However, the need for lithium within the defense sector will, in all likelihood, expand sharply over the next five years. Should a conflict with a peer or near-peer competitor occur, the gap between supply and demand may reach new extremes.

Along with extensive use in batteries, lithium enables several additional capabilities within the defense sector. Examples include alloys used in steel armor plating, combat-rated impact glass, and several polymers needed for aerospace, cyber, nautical, and space-related hardware.9 Lithium-related demand within the defense sector is poised to grow sharply in the near term. Two defense requirement categories will drive this change; these are (1) autonomous vehicles and (2) microgrids. Lithium applies to several other defenserelated requirements. However, these two misunderstood categories likely provide the strongest demand signal.

Autonomous and remotely piloted vehicles are becoming more and more prevalent across the battlefield environment. This new breed of weapon systems participates in the air, land, sea, and space domains. Paired with artificial intelligence and advanced algorithms, new au-

14 | Defense Transportation Journal | FEBRUARY 2023

Figure 3. Global EV sales February 2011 – February 2022.8

tonomous and semi-autonomous weapons systems continue to push the character of warfare into new directions. Within the ongoing war in Ukraine, remotely piloted aircraft like the Turkish-made Bayraktar Tactical Unmanned Aerial System have proved decisive. As with other unmanned weapons systems receiving operational use during the ongoing conflict, the Bayraktar relies on relatively lightweight, long-lasting lithium-ion batteries for propulsion and to supply power to on-board avionics, communications, and combat systems.10 Lithium-based power supplies enable extended battlefield loitering times while exposing a relatively slim operational profile. The light footprint and low heat signature of the Bayraktar make it resistant to conventional anti-aircraft and detection systems. In addition to having success in Ukraine, the Bayraktar also proved effective in Syria and the recent Armenia-Azerbaijan war.

Air-based autonomous and semi-autonomous weapons systems have taken the spotlight in recent conflicts. However, lithiumpowered capabilities are abundant across the other physical warfighting domains.

Space-based systems have long relied on lithium-ion batteries paired with solar panels. Space capabilities have been pivotal to the American way of war since the first Persian Gulf War. Unsurprisingly, space-based systems have become more capable with improvements in computing hardware and software fueled by top-end lithium-ion battery systems.

Lithium-enabled weapons have taken center stage in space and cyber domains. However, the same level of impact will soon occur in the land and sea domains. Lithium-ion battery-enabled robot combat systems like the Army’s Ripsaw autonomous combat vehicle and the Navy’s Snakehead Large Displacement Unmanned Undersea Vehicle (LDUUV) have reached the initial stages of operational fielding.11 These systems, and others like them, may prove decisive in future conflicts.

Weapons systems that function at or near the front line typically receive the most attention within defense circles.14 However, one of the essential capabilities

enabled by lithium batteries includes the opportunity to construct power supply microgrids. Independent microgrids reduce and eliminate the risk associated with large power production sites. Microgrids gather and store power provided by conventional generator farms, solar panels, wind turbines, or other forms of renewable power production. In forward combat areas, microgrids enable operational resilience and reduce risk by creating the opportunity to disperse both power production and power supply. This spreading of assets makes for a much harder target.

In addition to the capability provided to forward war fighters, microgrids offer the opportunity for exceptional resiliency to

the civilian sector—both in times of peace and in times of war. Microgrids have the potential to significantly limit the negative impacts from natural disasters and manmade disasters—such as a precision deep strike attack against a large power plant.

ENVIRONMENTAL, SOCIAL, AND GOVERNANCE (ESG)

While lithium offers tremendous environmental benefits by reducing—and potentially eliminating—the need for carbon-based energy, the material also offers particular environmental challenges. Extracting lithium typically involves largescale strip mines and significant quantities of water. Additionally, some skeptics have

www.ndtahq.com | 15

Figure 4 – Textron Ripsaw Combat Vehicle.12

Figure 5 - Snakehead LDUUV.13

asserted that lithium is difficult to recycle and may create as many problems as it solves.15 However, the accelerating rate of global climate change may prove to be a forcing function for lithium technologies and the policies that guide the industry.

More than 95% of lithium extraction occurs in four countries: Australia, Chile, China, and Argentina.16 These countries increased lithium production in each of the last five years. However, supply continues to fall short of demand. Prospects for the long term are even worse. Planned mine expansions do not come close to forecasted requirements.

Despite the aforementioned difficulties, some hope is available regarding lithium production. A tremendous surge in lithium surveying activity is underway globally. This multipronged survey effort has achieved success and will likely continue to achieve success. New and expanded lithium reserves are being revealed on an almost daily basis. As a whole, known sources for lithium have increased by more than three times over the last three years.17 However, the efficacy of these new sites remains unproven. Further exploration and proof must occur.

Increased lithium production has advanced innovation within the mining industry. Conventional lithium extraction requires 500,000 gallons of water per ton of useable material. However, new extrac-

tion techniques may enable this number to drop to almost zero.18 While getting to zero water use may ultimately prove unreasonable relevant to the associated costs, other innovations offer more in the near term. Recent research at the University of Texas hints at the potential for a low-cost method

Most lithium processing occurs in China, particularly most high-end lithium processing. The lack of diversification in lithium processing presents a substantive challenge to US security.

As supply and demand challenges across the lithium industry grow, the need for intelligent policies also increases. The US must take care in setting governance practices that enable optimal outcomes. Supply and demand must be assured, but the environment must also be protected. More lithium is needed, but failure to halt climate change is its own challenging national security problem.20

POLICY & STRATEGY

The world has changed significantly over the last twenty years—and more change is on the way. US interests benefit when national-level policies and strategies orient on the present rather than the past. However, US interests benefit the most when policies and strategies focus on both the present and the future. Currently, US policies and strategies are wholly unfocused on current and future requirements relevant to the global lithium supply. Additionally, the US approach to policy and strategy should consider both near-term and longterm needs. The US must continuously reassess and update policy and strategy to ensure optimal outcomes in concert with this approach.

of removing lithium from contaminated water.19 If proven and fielded, this new method could transform the industry.

While the distribution of lithium reserves continues to grow, the global economy’s ability to process lithium remains constrained. Most lithium processing occurs in China, particularly most high-end lithium processing. The lack of diversification in lithium processing presents a substantive challenge to US security. New processing capabilities are emerging globally. However, to date, these new sites are relatively inconsequential.

For the near term, the US should embrace three strategic lines of effort. First, the US should set policies to enable a sizable strategic stockpile of lithium. A strategic stockpile will enable the US to ride out market fluctuations more easily. Additionally, the US will be more resilient to market denial events (i.e., an event where the US is cut off from the world lithium supply by an aggressive actor or by a natural disaster). In addition to creating a strategic stockpile, the US must increase domestic production of lithium. Doing so will further reduce the risk to US interests. Finally, the US must accelerate research and development to find alternative materials to compete against and potentially outperform the current lithium-based battery market in the near term. US-funded research could enable new and separate energy storage options. Alternatively, USfunded research into energy storage technology could help make better lithium

16 | Defense Transportation Journal | FEBRUARY 2023

Aerial view of the lithium mine of Silver Peak, Nevada, California, USA.

batteries—configurations requiring less lithium while providing more power.

Over the long term, the US needs to consider two lines of effort. The first is that the US must ensure that it possesses a vertically integrated lithium industry capability. Presently, no such capability exists. The US has minimal mining capacity, limited processing capacity (refining lithium into useable material), and minimal component production capacity (battery production). The US must reduce strategic risk by building and sustaining a domestic capability. The second long-term approach includes attention to US allies and key partners. Assuring that allies and partners have reliable access to lithium will reduce risk to US interest. The US way of national security relies on healthy alliances. Insecure US allies makes for an insecure US.

CONCLUSION

Lithium, which economists increasingly refer to as ‘the new oil,’ remains a vital resource for the US, our allies, and our strategic competitors. Modern economies, and the militaries that defend them, cannot function without stable access to lithium-enabled products. World lithium production tripled from 2011 to 2021, mainly due to production increases from China and Australia. Projections for the next ten years indicate that lithium demand will increase between seven-fold and twelve-fold. Consequently, production increases may prove insufficient for projected demand. As with oil in the 20th century, disconnects between the supply and demand of lithium may drive international behavior in the 21st century [i.e., Paraguay-Bolivia 1932, Japan-US 1941, Iraq-Kuwait 1990, etc.].

Australia, a US ally, holds the largest lithium reserve, which reduces risk to US interests. Large lithium reserves exist in several parts of South America, further reducing the risk to US interests. However, risks offset by new lithium mines in South America rebound due to the same countries having joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Regarding Australia, the tyranny of distance and proximity to Chi-

na adds risk, especially in the event of a shooting war involving world powers. How lithium limits the surge capacity of the DIB is particularly concerning. The negative impact on the DIB’s surge capacity is a present and worsening problem that will degrade further before it can improve. Policymakers should view risk to the DIB and national security as unacceptable. US policies and corresponding strategies must quickly evolve to address the ongoing and projected challenge to the lithium supply chain and its associated negative impact on US interests. DTJ

1. Royal Society of Chemistry, “Lithium Fact Page,” ROS.com, available at: https:// www.rsc.org/periodic-table/element/3/ lithium#:~:text=Lithium%20is%20rare%20 in%20the,lithium%20minerals%20to%20 be%20discovered

2. Ibid.

3. Douwe Draaisma, “Lithium: the gripping history of a psychiatric success story,” Nature, August 26, 2019, https://www.nature.com/ articles/d41586-019-02480-0

4. Office of the Secretary of Energy, “National Blueprint for Lithium Batteries – 2021-2030,” Department of Energy, June 2021, https:// www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2021-06/ FCAB%20National%20Blueprint%20 Lithium%20Batteries%200621_0.pdf

5. US Security & Exchange Commission, “Chemical Plat PFS Demonstrates Exceptional Economics and Optionality of USA Location,” SEC, May 26, 2020, https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/ data/1728205/000172820520000018/ex99_1.htm

6. China’s domination of the lithium market is currently in decline. Most industrial countries are in the processes of expanding lithium component manufacturing. While China’s volume of production as not declined, its overall market share continues to decrease.

7. Annie Lee, “The Battery Metal Really Worrying China Is Lithium, Not Nickel,” Bloomberg, April 4, 2022 https://www.bloomberg.com/ news/articles/2022-04-04/the-battery-metalreally-worrying-china-is-lithium-not-nickel

8. Argonne National Laboratory, “Light Duty Electric Drive Vehicles Monthly Sales Updates,” November 2019, Argonne National Lab website, https://www.anl.gov/es/light-dutyelectric-drive-vehicles-monthly-sales-updates

9. Defense uses

10. Naval-Technology webpage, “Bayraktar Tactical Unmanned Aerial System,” NavalTechnology. com, January 11, 2015, https://www.navaltechnology.com/projects/bayraktar-tactical-

unmanned-aerial-system/

11. Todd South, “Soldier will test Army’s new robotic combat vehicle in 2022,” Army Times, December 21, 2021, https://www.armytimes. com/news/your-army/2021/12/21/soldiers-willtest-armys-new-robotic-combat-vehicle-in-2022/ and Amit Malewar, “U.S. Navy showcases its new Snakehead unmanned submarine,” Inceptivemind.com, February 21, 2022, https:// www.inceptivemind.com/us-navy-showcasessnakehead-unmanned-submarine/23396/

12. Textron Systems, “M5 Information page,” Textron Systems, accessed April 4, 2022, https://www.textronsystems.com/products/m5

13. https://www.navalnews.com/navalnews/2022/02/u-s-navy-christens-firstsnakehead-lduuv-prototype/

14. Front line = Forward Line of Troops [ref. concepts described in Army Publication 3 & Joint Publication 3]

15. IER, “The Environmental Impact of Lithium Batteries,” Institute for Energy Research, November 12, 2020, https://www. instituteforenergyresearch.org/renewable/ the-environmental-impact-of-lithiumbatteries/#:~:text=The%20lithium%20 extraction%20process%20uses%20a%20lot%20 of,and%20pump%20salty%2C%20mineral-rich%20brine%20to%20the%20surface.

16. Vladimir Basov, “The world’s largest lithium producing countries in 2021 – report,” Kitco. com, February 1, 2022, https://www.kitco.com/ news/2022-02-01/Global-lithium-productionup-21-in-2021-as-Australia-solidifies-its-toplithium-producer-status.html

17. M. Garside, “Lithium mine production worldwide form 2010 to 2021,” Statistia, 2022, https://www.statista.com/ statistics/606684/world-production-oflithium/#:~:text=Lithium%20mines%20 produced%20an%20estimated,was%20 just%2028%2C100%20metric%20tons.

18. Robin Bolton, “Lithium mining is booming – here’s how to manage its impact,” GreenBiz, August 11,2021, https://www.greenbiz.com/ article/lithium-mining-booming-heres-howmanage-its-impact

19. UT News, “New Way to Pull Lithium from Water Could Increase Supply, Efficiency,” University of Texas at Austin, September 08, 2021, https://news.utexas.edu/2021/09/08/ new-way-to-pull-lithium-from-water-couldincrease-supply-efficiency/

20. Flavelle et al., “Climate Change Poses a Widening Threat to National Security,” New York Times, November 1, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/21/ climate/climate-change-national-security. html#:~:text=Intelligence%20and%20 defense%20agencies%20issued,between%20 countries%20and%20spur%20migration.

www.ndtahq.com | 17

Department of Defense Strategy

Aims to Support Critical Facet of Defense Industrial Base

The United States faces unprecedented national security and economic challenges. Strategic competitors seek to displace the US military as the world’s preeminent force, the COVID-19 pandemic and impacts from climate change have exposed fragility in critical supply chains, and consolidation in the defense marketplace has undermined the competition and innovation needed to provide the best systems, technologies, services, and products to support the warfighter. These vulnerabilities especially threaten capital-strapped small businesses, which represent a majority of prime- and sub-tier defense suppliers. As part of its efforts to support this critical facet of the industry, the Department of Defense (DOD) has released its Small Business Strategy. This Strategy outlines strategic objectives that will enable the DOD to expand and strengthen its relationship with small businesses and better leverage their capabilities to help solve the Department’s and our Nation’s most complex challenges.

THE IMPORTANCE OF SMALL BUSINESSES

panies that did business with DOD. One high-profile example is Moderna, a former small business and Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) grant recipient that produced millions of mRNA vaccines to help fight the COVID-19 global pandemic. Without small businesses, the vital engine of growth for the United States industrial base would cease to exist.

SMALL BUSINESS CHALLENGES

Despite their importance to the Department, small businesses face various obstacles in helping DOD meet its challenges.

ness prime contracting goal for the past eight years, the number of small businesses participating in the defense industrial base has declined by over 40 percent in the past decade. Over time, a decline in the number of small businesses participating in defense acquisitions will lead to a reduction of innovative concepts, capabilities, quality of service and increased acquisition costs.

DOD ACTIONS & INITIATIVES

“Small businesses help ensure that our military has the very best capabilities to keep us safe. Some of the most innovative minds in the country come from smaller companies, and in an era of strategic competition small businesses are one of our greatest tools. Despite their significance to the defense mission, the Department of Defense has yet to utilize the full potential of small businesses,” read a message by Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III. “This Small Business Strategy outlines a Department-wide plan to harness the power of America’s small, innovative, and agile companies and grow their contributions to the defense mission.”

Through recognizing these vulnerabilities now, the Department can respond with targeted initiatives that leverage diverse small business suppliers to strengthen our domestic supply chains, reduce reliance on single or sole sources of supply, and help ensure the United States continues to lead in innovation. By adjusting to macroeconomic trends and understanding that the Department must take action to encourage more small businesses to work with the Department, DOD can implement appropriate strategies to expand use of small businesses.

It is imperative for the Department to focus on small business. These innovative companies account for 43 percent of all high-tech jobs in the US and generate sixteen times more patents than large firms. Small businesses spur innovation, represent most new entrants into the Defense Industrial Base (DIB), and through their growth represent the next generation of suppliers with increasingly diverse capabilities. Small businesses are agile and often can implement change more quickly than larger firms. In Fiscal Year (FY) 2021, small businesses made up 73 percent of all companies that did business with DOD and 77 percent of the research and development (R&D) com-

Regulations and business practices can be difficult to understand or otherwise create barriers or increase the cost of doing business with DOD. Larger, better-resourced companies are better able to navigate these obstacles and address these costs than smaller businesses. Some of these barriers include confusing points of entry into defense markets, improper bundling and consolidating of contracts, and understanding complex regulations. These barriers strain the relationship between the Department and small businesses.

In combination with economic conditions leading to a consolidating DIB, these barriers have contributed to a reduction of small businesses in the DIB. Although the Department has achieved its small busi-

Increasing small business participation in defense acquisitions is critical. Expanding participation will keep DOD at the forefront of innovation, while simultaneously fostering increased competition that can reduce costs for high quality capabilities. It will also ensure that the Department continues to leverage the untapped potential of disadvantaged-, women-, and veteran-owned small businesses that have historically been underutilized. As the Department aims to maintain the technological edge, small businesses are key. These small business efforts are a critical part of implementing the Department’s broader industrial base priorities, which directly support and align with the priorities of the President. These priorities include ensuring robust domestic capacity and capabili-

www.ndtahq.com | 19

ties to meet our national security challenges, promoting competition in the procurement process to benefit from improved costs, performance, and innovation, and advancing equity and inclusion in defense acquisition to leverage the unique talent and ideas that come from diverse communities from across the country. Success of implementing these priorities relies on small businesses being drivers to generate these outcomes.

DOD’S SMALL BUSINESS STRATEGY

The Department of Defense built its Small Business Strategy around three strategic objectives. First, improve management practices by sharing best practices and creating efficiencies across the enterprise for small business activities and programs. Second, ensuring that small business activities within DOD better support national security priorities. And third, strengthening the Department’s ability to engage and support small businesses. Implementing this strategy will make the DIB more innovative, resilient, and effective, producing a Joint Force that is better equipped to execute its mission.

The strategy heavily relies on the Department’s own continued push for excellence. Numerous existing small business initiatives have made incredible progress in addressing these issues. For example, the Department of the Air Force’s Open Topic Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and the Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs have successfully brought first time applicants into the DOD. This strategy seeks to uncover similar pockets of excellence, share best practices, develop policy, distribute guidance, and establish initiatives, as appropriate, to continue to accelerate the Department’s ability to partner with and benefit from America’s small business base.

STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 1: Implement a Unified Management Approach for Small Business Programs and Activities

The Department’s small business programs, activities, and workforce are distributed across the Military Services, Defense Agencies, and field activities (DOD Components), including Components of the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD). This distribution, although beneficial in some areas, also often leads to confusion for small businesses as to what the entry points are, how programs and initiatives connect to each other, and how a small business can or

should utilize DOD’s various small business programs to mature their capabilities from prototype to full-scale integration or to diversify the goods and services they provide to DOD. To address these issues, DOD will develop and implement a unified management structure for DOD small business programs and activities, develop a unified small business professional workforce, and streamline entry points, and improve small business access to decision makers.1

STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 2: Ensure the Department’s Small Business Activities Align with National Security Priorities

National security concerns are a primary force guiding the Department’s military and defense objectives. Accordingly, national security concerns should guide the Department’s activities with respect to the small business industrial base. To build enduring advantages and get the technology we need more quickly, DOD must have access to a healthy small business industrial base with broad capabilities to produce parts and systems, secure supply chains, and access

To address these issues, DOD will develop and implement a unified management structure for DOD small business programs and activities, develop a unified small business professional workforce, and streamline entry points, and improve small business access to decision makers.

tice small businesses into the defense marketplace, while simultaneously taking into account their commercial growth objectives. The Department will ensure small business activities are carried out to further national defense priorities through efforts to stabilize and scale existing programs that help small technology and manufacturing businesses deliver capabilities to the warfighter, utilize data tools to understand and expand small business participation and spending, and expand policy and process engagement of small business professionals and senior leaders on small business matters.

STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 3: Strengthen the Department’s Engagement and Support of Small Businesses

For the Department to effectively support small businesses, DOD must improve its ability to meaningfully engage with small businesses including firms from critical socioeconomic categories and underserved communities. The Department must also ensure that its operational and acquisition leadership continues to recognize the abilities of small business to support the defense mission, and that small businesses can understand and access the Department’s most current initiatives, efforts, and policies. Furthermore, DOD should provide training and other resources to help educate small businesses and enhance their ability to resist cyber threats, IP infringement, and foreign ownership, control, or influence. These efforts help reduce the vulnerability of the DOD’s supply chain. The Department will advance these efforts through strategies to improve outreach and communication with small businesses, provide cybersecurity training and resources to small businesses, and educate small businesses. DTJ

a skilled workforce. Presidential executive orders to promote competition,2 foster supply chain resiliency,3 and advance equity4 also put small business at the nexus of the nation’s economic and national security priorities. Attending to commercial trends is critical, as today’s innovative companies have many choices for capital, are not reliant on defense spending, and, therefore, have other options for how to do business. These trends may lead to adverse incentives that inhibit the Department’s ability to access America’s most innovative minds, and potentially impacting DOD’s ability to achieve national defense priorities. The Department must, therefore, take action to en-

1 Section 4901 of title 10, United States Code (U.S.C.); Section 861(b) of the William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 (Public Law 116-283); Department of Defense Instruction (DoDI) 4205.01 “DoD Small Business Programs (SBP)” (August 2018); DoDI 5134.04 “Director of Small Business Programs (SBP)” (December 2017).

2 Executive Order (E.O.) 14036 “Promoting Competition in the American Economy” (July 2021).

3 E.O. 14017 “America’s Supply Chains” (February 2021).

4 E.O. 13985 “Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government” (January 2021).

20 | Defense Transportation Journal | FEBRUARY 2023

Bringing Manufacturing Back to the US Requires Political Will, But Success Hinges on Training American Workers

By Amitrajeet A. Batabyal, Distinguished Professor, Arthur J. Gosnell Professor of Economics, & Interim Head, Department of Sustainability, Rochester Institute of Technology for The Conversation

Supply chain disruptions during COVID-19 brought to light how interdependent nations are when it comes to manufacturing. The inability of the US to produce such needed goods as test kits and personal protective equipment during the pandemic revealed our vulnerabilities as a nation. China’s rise as a global production superpower has further underscored the weaknesses of American manufacturing.

In addition to fixing supply chain disruptions, bringing manufacturing back to the US will benefit national security. Advanced computer chips, for example, are disproportionately made by a single firm, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. These microchips are critical to smartphones, medical devices and selfdriving cars, as well as military technology. TSMC, from a US national security perspective, is located too close to China. Taiwan’s proximity to China makes it vulnerable because the Chinese government threatens to use force to unify Taiwan with the mainland.

My research and that of others examines how the lack of manufacturing competitiveness in the US leaves the US vulnerable to shortages of critical goods during times of geopolitical disruption and global competition. The strategies the US employs in bringing back manufacturing, along with innovative practices, will be key to ensure national security.

STRENGTHENING NATIONAL SECURITY

President Joe Biden has signed two bills that propose to rebuild American manufacturing. The CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 will provide US$52.7 billion for American semiconductor research, development, manufacturing and workforce development.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 will invest $369 billion to promote a clean energy economy, in part by offering generous incentives for US-made electric cars. Training workers for new advanced manufacturing is another key factor in strengthening a sector that has become increasingly reliant on technology. In fact, while the number of jobs in American manufacturing fell by 25% after 2000, manufacturing output did not decline. Still, American manufacturing is facing a massive shortage of labor, especially among those workers with skills needed to power a new generation of manufacturing.

www.ndtahq.com | 23

This need to train a new group of skilled workers explains why federal funds in the CHIPS Act are set aside for workforce development. Complementing federal legislation are programs such as America’s Cutting Edge, a national initiative that provides free online and in-person training designed to meet the growing need in the US machining and machine tool industry for skilled operators, engineers and designers.

THE POWER OF INNOVATION

It is impractical to bring all manufacturing back to the US. Offshoring is often less expensive. But research shows that certain types of in-country manufacturing can not only help secure national security but also spark innovation.

When research and development (R&D) are conducted close to where the goods are physically made, this proximity can increase the likelihood of collaboration between these two activities. Collaboration can lead to greater efficiencies.

Product development can benefit as well. New research demonstrates that US firms that located their manufacturing and R&D physically close to each other generated more patents than firms that did not.

Even so, the contribution of US manufacturing firms to innovation declined greatly between 1977 and 2016. That’s because the benefits of locating manufacturing and R&D close to each other depends on the nature of the manufacturing itself, researchers have found.

For instance, the design of new drugs often requires manufacturing facilities to be located nearby. In that respect, co-locating manufacturing and research and development makes sense. This can be true for semiconductors as well. World-class chip manufacturers in Taiwan, such as TSMC, are located alongside a growing chip design industry, which permits designers to prototype and test new ideas quickly.

The US and other countries are betting on the same potential benefits from colocation. For instance, to minimize the dependence on TSMC and, more generally, on foreign sources for chips, the European Union is spending 43 billion euros, while Japan is encouraging chip manufacturing at home with a $6.8 billion investment.

PEOPLE ARE THE BOTTOM LINE

In a 2011 op-ed, I argued that while federal legislation to promote US manufacturing could succeed in bringing more

manufacturing back to the US, there was no guarantee that large numbers of jobs would be created—a key point made by those seeking to promote manufacturing.

Governments are generally poor at picking winning technologies and industries. Governmental mistakes in picking supposedly winning industries or sectors have, generally, led to a great deal of waste of taxpayer dollars.

In fact, market forces and informed company decisions should, I believe, play a larger role picking winners than federal investment. Where that investment comes from, what it supports, and how much money is needed are critical questions.

If firms choose to relocate their companies to benefit from the synergy of R&D, then they must be able to attract the best human resource talent available. This is where US investment can help build a more skilled workforce.

As pointed out by the economist Gary Pisano, many policymakers in the US have long believed that manufacturing is an attractive sector for people with less education and training. Therefore, as a nation, we have not devoted many resources to train people with specialized skills in manufacturing.

This approach stands in stark contrast to the approach followed in Germany. There, practical work is valued by employers and employees and hence apprenticeship programs are routinely used to train workers who are well qualified to work in the manufacturing sector. While the US approach is changing with recently announced investment by the White House through the CHIPS and the Inflation Reduction acts, more is needed.

It is my belief that if the US is to remain an economic powerhouse, then corporations should not separate their workforce, sending cost-saving manufacturing offshore while retaining the innovators. Corporations like Apple have sent nearly all of their production offshore, retaining only the most skilled parts of the supply chain involving activities like R&D.

Instead, the US needs to financially support firms wishing to bring manufacturing back by making it easier for such firms to find qualified manufacturing workers at home—and close to innovators when practical. This effort will bolster the US’s ability to be self-sufficient, innovative and secure in times of geopolitical conflicts. DTJ

24 | Defense Transportation Journal | FEBRUARY 2023

If firms choose to relocate their companies to benefit from the synergy of R&D, then they must be able to attract the best human resource talent available. This is where US investment can help build a more skilled workforce.

Forthcoming Rules Will Necessitate Climate Reporting and Supplier Visibility Across the Supply Chain

By Sharon Lo, Managing Editor, DTJ & The Source

The importance of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting has increased rapidly in recent years as public expectations shift and these performance measures influence investors’ decisionmaking. According to McKinsey, as of 2019, global sustainable investment topped $30 trillion. This amount constituted a 68% increase since 2014 and a tenfold increase since 2004.1

But, despite increases in interest and investments in ESG, measurement and reporting standards are inconsistent. To that end, this past May the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) released proposed amendments to rules and reporting forms that aimed to “promote consistent, comparable, and reliable information for investors concerning funds’ and advisers’ incorporation of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors.”

In short, the SEC will require publicly traded companies to report their total emissions and standardize the metrics by which the reporting is done. But, as we have seen time and time again over the last few years, the interconnected nature of supply chains means that these changes will be felt by companies large and small, across the supply chain, publicly traded or not.

There are three categories of emissions—Scope 1, 2, and 3. Scope 1 are the Green House Gas (GHG) emissions a company makes directly, such

What is ESG?

Environmental: includes issues focused on climate risks, carbon emissions, energy efficiency, use of natural resources, pollution and biodiversity

Social: includes issues focused on human capital, labor regulations, diversity, DEI, safety, human rights and community involvement

Governance: includes issues focused on board diversity, corruption and bribery, business ethics, compensation policies and general risk tolerance 3

use them. For many businesses, Scope 3 can account for more than 70% of their carbon footprint.2

Scope 1 and 2 emissions, by and large, can be controlled, tracked, and reported by the company itself. To report Scope 3 emissions companies will have to report on emissions data on the operations and supply chains of their suppliers. This is a daunting task—especially if the company faces penalties or liability for reporting on something so widely out of its control.

as emissions that occur from running boilers at company-owned facilities or fuel used by company-owned vehicles.

Scope 2 covers emissions a company makes indirectly, so emissions that are generated when a company purchases electricity, steam, heat, or cooling from a utility company.

Scope 3 emissions include all emissions associated, not with the company itself, but that the organization is indirectly responsible for, up and down its value chain. This includes tasks such as buying products from suppliers and from products when customers

Originally these rules were set to take effect as early as March of 2023. Currently, the SEC is still reviewing public comments and the rules will likely not go into effect until April or perhaps even later. In the interim, companies large and small, publicly traded or not should prepare. And not just for this particular change. This is just one of many instances where sustainability and supplier visibility are shifting from trends to imperatives for those in industry. DTJ

1 McKinsey & Company. (2023, January 30). What is ESG? Retrieved from McKinsey. com: www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/ mckinsey-explainers/what-is-esg

2 Deloitte. (2023, January 30). Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions What you need to know. Retrieved from deloitte.com: https:// www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/focus/climatechange/zero-in-on-scope-1-2-and-3emissions.html

3 Ernst & Young. (2023, January 30). ESG Reporting. Retrieved from ey.com: www.ey.com/en_us/esg-reporting

26 | Defense Transportation Journal | FEBRUARY 2023

www.ndtahq.com | 27

CHAIRMAN’S CIRCLE

AAR CORP.

AAT Carriers, Inc.

Agility Defense & Government Services

Air Transport Services Group (ATSG)

AIT Worldwide Logistics, Inc.

ALARA Logistics

Amazon

American President Lines, LLC

American Roll-on Roll-off Carrier (ARC)

Amtrak

Atlas Air Worldwide Holdings

Bennett

C5MI

Carlile Transportation Systems, LLC

Cervello Global Corporation

CGI Federal

Chapman Freeborn Airchartering, Inc.

Construction Helicopters, Inc. (d/b/a CHI Aviation)

Crane Worldwide Logistics, LLC

Crowley

Deloitte

DHL Express Enterprise Holdings

FedEx

Freeman Holdings Group

Hapag-Lloyd USA, LLC

International Auto Logistics

Kalitta Air LLC

Landstar System, Inc.

Liberty Global Logistics

Maersk Line, Limited

Matson

Microsoft Federal

National Air Cargo

Omni Air International, LLC

Patriot Maritime Reify Solutions, LLC

Salesforce

SAP

Schuyler Line Navigation Company LLC

Sixt rent a car

Southwest Airlines

The Pasha Group

TOTE Group

Tri-State Motor Transit Co.

United Airlines

US Ocean, LLC

Waterman Logistics

PRESIDENT’S CIRCLE

AEG Fuels

Air Charter Service

American Maritime Partnership

Amerijet International, Inc.

Berry Aviation, Inc.

BNSF Railway

Boeing Company

Boyle Transportation

Bristol Associates

Choice Hotels

Coleman Worldwide Moving

CSX Transportation

CWTSatoTravel

EASE Logistics

Echo Global Logistics, Inc.

Ernst & Young

Global Logistics Providers LLC

ICAT Logistics

KGL

Leidos

National Air Carrier Association

Norfolk Southern Corporation

SAP Concur Sealift, Inc.

Sonesta International Hotels Corporation

Telesto Group LLC

The Port of Virginia Transportation Institute

U.S. Bank

Union Pacific Railroad

Western Global Airlines

Wyndham Hotels & Resorts, Inc.

28 | Defense Transportation Journal | FEBRUARY 2023

These corporations are a distinctive group of NDTA Members who, through their generous support of the Association, have dedicated themselves to supporting an expansion of NDTA programs to benefit our members and defense transportation preparedness.

HONOR ROLL OF SUSTAINING MEMBERS AND REGIONAL PATRONS

ALL OF THESE FIRMS SUPPORT THE PURPOSES AND OBJECTIVES OF NDTA

SUSTAINING MEMBERS

3Sixty

Able Freight

Accenture Federal Services

Admiral Merchants Motor Freight, Inc.

Alacran

All Aboard America Holdings

American Bureau of Shipping

American Maritime Officers

American Trucking Associations

Apex Logistics International Inc.

ArcBest

Army & Air Force Exchange Service

Arven Services, LLC

ATS Specialized, Inc.

Avis Budget Group

Baggett Transportation Company

Beltway Transportation Service

Benchmarking Partners, Inc.

Bolloré Logistics

BWH Hotel Group

Cornerstone Systems, Inc.

Council for Logistics Research

Cypress International, Inc.

Delta Air Lines

Drury Hotels LLC

Duluth Travel, Inc. (DTI)

EMO Trans, Inc.

Estes Forwarding Worldwide

Eyre Bus Service, Inc.

FSI Defense, A FlightSafety International Company

GeoDecisions

Global Secure Shipping

Green Valley Transportation Corp.

Guidehouse

Hilton Worldwide

Hyatt Hotels

IHG Army Hotels

Intermodal Association of North America (IANA)

REGIONAL PATRONS

ACME Truck Line, Inc.

Amyx

Atlas World Group International

C5T Corporation

CakeBoxx Technologies, LLC

CarrierDrive LLC

Cartwright International

Columbia Helicopters, Inc.

International Association of Movers

International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), AFL-CIO

Interstate Moving | Relocation | Logistics

Jacksonville Port Authority (JAXPORT)

K&L Trailer Sales and Leasing

Kansas City Southern Railway Company

Keystone Shipping Co.

LMI

Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association

Martin Logistics Incorporated

Mayflower Transit

McCollister’s Global Services, Inc.

Mercer Transportation Company

mLINQS

National Charter Bus

National Corporate Housing, Inc.

National Industries for the Blind (NIB)

National Motor Freight Traffic Association, Inc.

National Van Lines, Inc.

Nika Corporate Housing

Northern Air Cargo, LLC

Omega World Travel

One Network Enterprises, Inc.

ORBCOMM

PD Systems, Inc.

Perfect Logistics, LLC

Pilot Freight Services

Placemakr

Plateau GRP

PODS Enterprises LLC

Port of Beaumont

Port of Corpus Christi Authority

Port of San Diego

Ports America

Prestera Trucking, Inc.

Procharter

Prosponsive Logistics

PTS Worldwide

Radiant Global Logistics

Dalko Resources, Inc.

Enterprise Management Systems

HLI Government Services

JAS Forwarding

John D. Odegard School of Aerospace Sciences

Kalitta Charters, LLC

Lineage Logistics

LMJ International Logistics, LLC

Lynden, Inc.

Move One Logistics

NovaVision, LLC

Overdrive Logistics, Inc.

PITT OHIO

Port Canaveral

Port of Port Arthur

Priority Worldwide

Seatac Marine Services

Ramar Transportation, Inc.

Rampart Aviation

Red Roof Inn

Sabre

SAIC

Savi

SeaCube Containers

Seafarers International Union of NA, AGLIW

SEKO Logistics

Selsi International Inc.

Signature Transportation Group

Smith Currie & Hancock LLP

SSA Marine

St. Louis Union Station Hotel a Curio Hotel

Collection by Hilton

StarForce National Corporation

Stevens Global Logistics, Inc.

Swan Transportation Services

The DeWitt Companies

The Flight Lab Aviation Consulting LLC

The Hertz Corporation

The Suddath Companies

TLR – Total Logistics Resource, Inc.

TMM, Inc.

Toll Group

Trailer Bridge

Transport Investments, Inc.

Transportation Intermediaries Assn. (TIA)

Travelport

Trinity Shipping Company

TTX Company

Tucker Company Worldwide, Inc.

U.S. Premier Locations

Uber for Business

UNCOMN

United Van Lines, Inc.

UPS

US1 Logistics

Women In Trucking Association, Inc.

World Fuel Services – Defense Solutions

Yellow Corporation

UNIVERSITIES

Critical Infrastructure Resilience Institute – University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

McKendree University

TechGuard Security

Trans Global Logistics Europe GmbH

www.ndtahq.com | 29

www.ndtahq.com |

labor, funding. Manufacturers are more interested than ever and may be required to validate subvendor supplier information down six or more levels to ensure the efficacy of manufacturing materials and pedigree. More scrutiny and laws will surely follow regarding foreign investments

We have a new Jobs Board where participating companies are directing you to their hiring sites. We hope this brings additional networking value to our membership. Give us your feedback!

issues related to and impacting transportation and logistics. These issues involve “nuts and bolts” matters such as base access and manning needed to operate vessels and financial matters. Also, Joint “theater support” continues to be a focus in exercises throughout the world—to include the defense of our homeland. Our educational programs will continue to “tee up” important discussions, matters and objectives related to the transportation and logistics military and commercial industrial base. This aspect of the overall US industrial base is a key enabler to our nation’s economy and national security.

for their outstanding insights, education and professional development value. Also, we have a new Jobs Board where participating companies are directing you to their hiring sites. We hope this brings additional networking value to our membership. Give us your feedback!

Lastly, I encourage local chapters to continue to meet and draw in new members. NDTA has much to provide young logisticians, transporters and those working functions such as contracting and finance! If there is anything I can do to help in this regard, please let me know.

in these areas—including land and other critical infrastructure industries. A reset in the relationship with China will likely take some time and significant political policy breakthroughs.

In 2023, NDTA will remain engaged to educate logisticians and leaders about