MASTHEAD LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

Dear Readers,

Welcome to the second edition of Prosody, Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin’s official studentrun literary and arts magazine. We hope not only to showcase creative works by students, residents, and faculty, but to provide an outlet for the Dell Medical School community to share their experiences through artistic expression.

The journey through medical training is transformative. Maybe it began with a loved one in a hospital or personal experience. Maybe it was driven by ambition or a thirst for knowledge. We start eager to change the world, before we are humbled by our patient encounters. What is painstakingly memorized in textbooks does not translate into the broken system unraveling before us. Driven by economic forces and policies, we find modern medicine asking us to favor quantity over quality. Compassion does not always translate to efficiency. Sometimes after racking our brains, the best plan we come up with still discharges patients to the street.

Yet in the face of complex medical challenges, art becomes a powerful tool for healing and understanding. This edition encourages us to embrace the beauty and significance of the arts in our medical journey.

Our contributors explore this journey through the compassion physicians display in their work in the face of challenging circumstances. Health care workers often have to persevere through challenging circumstances, whether that be long hours or personal sacrifices. This can be seen in Dr. John Luk’s poem “Superheroes’’ where health care workers persevere “beyond to their long and tall shadows” as they don “the billowing capes of our healthcare heroes!” Alternatively, empathy can present itself in the face of grief which Rabab Isa, MS4 explores in her poem “Autopsy”: “Here Lies Physician Empathy, A Girl Who Wanted to Do Something That Mattered 1998-2023.” By celebrating our imperfections and resilience, we foster a holistic and compassionate approach to patient care.

We would also like to dedicate this edition to physicians involved in global conflicts. We honor their resilience, compassion, and unwavering commitment to healing in the face of adversity. These individuals inspire us to recognize the profound impact of health care in challenging environments and remind us of the global responsibility we carry as future health care professionals.

Victoria Siu, Alexis de Montfort Shepherd, Co-Editor-in-Chief Co-Editor-in-Chief

Executive Board

Editors-In-Chief: Victoria Siu, Alexis de Montfort Shepherd

External Communications: Lundyn Davis, Prachi Khanna, Rabab Isa, Natalie Lim

Design: Sahana Prabhu, Evelyn Syau, Zahra Ansari

Submissions: Chandana Tetali, Nuha Arefin, Richard Sames, Logan Muzyka

Finance: Ria Sur

Readers

Edy Adams, Emma Ableman, Katie Baker, Natasha Gengler, Austin Hermann, Carolyn Huynh, Sher Isada, Aiza Kahlun, Emma Lehrer, Esteban Pantoja, Rohit Prasad, Daniel Ramirez, Sanjana Ravi, Sunny Shah, Catherine Stauber, Jon Trujillo, Molly Van Dyke, Olivia Viscuso, Brooke Upchurch

Website Editor Jackie Castillo

Faculty Sponsors

Steve Steffensen, M.D.

Thomas Vetter, M.D., M.P.H., M.F.A

Advisory Board

Phil Barrish, Ph.D.

Carrie Barron, M.D.

Hannah Jane Collins

Craig Hurwitz, M.D.

Stephen Sonnenberg, M.D.

Swati Avashia, M.D.

Richard Peters, M.D.

Imelda Vetter, M.L.I.S

Ray Williams, M.A., M.Ed.

Cover

Lattice of Care by Anuska Martinez

Arguedas

Table of Contents

Icons created by Gregor Cresnar and sourced from The Noun Project

The works published in this journal were selected based on literary and artistic merit and do not reflect the views of The University of Texas at Austin, Dell Medical School or the editorial staff.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

4

Superheroes | John Luk, M.D.

4 Embracing Mortality | Nuha Arefin, MS2

6 Halcyon | Evelyn Syau, MS3

7 Lights | Thomas Varkey, M.D., PGY2, Alumni

8 The Boxer | William Tierney, M.D.

9 Study of Power | Victoria Siu, MS2

12 Adélie | Hani Talebi, Ph.D., L.S.S.P.

12 Purple Paradise | Lundyn Davis, MS3

14 Another Virus | Victoria Siu, MS2

14 Fences | Alexis de Montfort Shepherd, MS3

16 Ischiopagus Twins | Anuska Martinez Arguedas, MS3

17 O.C.D. | Rabab Isa, MS4

18 Mayfield Park | Swati Avashia, M.D.

19 Scoliotic Saplings | Emily McCalley, MS4

20 Whispers of Nature’s Eternal Flow | Sriya Dommaraju, Undergraduate

20 Truehearted Mountaineer | William Austin, MS3

22 Losing a Grandmother to the Haze | Victoria Siu, MS2

22 Stopping by a Lake on a Snowy Morning | Thomas Vetter, M.D., M.P.H., M.F.A.

24 On Loneliness | Richard Sames, MS1

24 The Sky Rejoices in the Morning’s Birth | Thomas Vetter, M.D., M.P.H., M.F.A.

26 Soulless | Haeley Shaw, Staff

27 452 | Raaj Pyada, MS3

28 Track 5, Side 1 | Tyler Jorgensen, M.D.

32 I Look Not to My Past | Justin Jensen, MS2

32 Burnout | Nuha Arefin, MS2

34 My Bike | Sam Burr, MS3

35 Guadalupe Mountain Mosey | Molly Van Dyke, MS1

36 Deadly Earnest | Thomas Vetter, M.D., M.P.H, M.F.A.

37 Pacemaker | Saurin Gandhi, D.O.

38 Heavenly Debauchery | Richard Sames, MS1

39 Sorrowful Grace | Ayla Farzamnia, Undergraduate

40 Cicada | William Austin, MS3

41 Autopsy | Rabab Isa, MS4

42 Grief Felt | Thomas Varkey, M.D., PGY2, Alumni

42 House | Georgia Williams, MS4

44 Unknown Stretch | Michelle Bach, MS4

45 Gripped by Silence | Ayla Farzamnia, Undergraduate

46 Maisie | Haeley Shaw, Staff

47 Medicine | Richard Sames, MS1

SUPERHEROES

John Luk, M.D.

If I had a superpower, I would use it to do good

To plunge into mood’s depth without fear or platitude

From joy to anguish, from high to low, I will be there

Ready to serve or to lend a hand, no matter where

If I had a superpower, I would articulate the love

Describe it so to uplift it highest above

I would ease suffering earthly and sickly

Relieve experiences uncomfortably prickly

If I had a superpower, I would connect us all

To make bonds so strong that even gravity cannot stall

I would impart knowledge, to comfort, and to nourish

Ease the pain so that our shared existence can flourish

If I had a superpower, I would right the wrongs

I would transform the sad notes into joyous songs

In a world that is full of wonder and awe

There remains much for me to experience in the raw

If I had a superpower, I would choose only this

That I would use words to comfort and uplift

I would speak the language in core shared

To include, to invite, to coexist, to joy unimpaired

I do have that superpower—a gift of words

To give flight to feelings to ears unheard

The language of community that connects us all

It sustain our bond amid shine and squall

As a physician I use that superpower to build and to heal

I use words as my medical sword and shield

To defend those hurting, suffering, and starving

To give them hope and strength to face life jarring

As a healer I can walk a patient’s path

Through their words offered in full or in lath

I would listen and tender my respect

By quietly processing words delivered unchecked

For through this superpower may I affirm the trust

That patients have bestowed onto me with faith uncussed

To share words bound in the language of humanity

Connecting us in times of great joy and calamity

EMBRACING MORTALITY , Nuha Arefin, MS2

If I had a superpower, it would be the language

With which to offer kindness, respect, and courage

For in our exchange, we recommit ourselves To choose the right words that give wind to right sails

This is the superpower of healthcare heroes

Through a pandemic as seasons unfold

The league of individuals diverse and predisposed To serve with valor and humility well composed

We have a superpower to shine right and true In the face of fear and suffering all in queue

Our healthcare heroes do not shy away from the view

Facing it with courage steeled and renewed

Our healthcare heroes abound with might To care, to assuage, to diagnosis, to make right For in their superpowers lie hearts of gold

With caring and character in abundance to behold

Through sickness and health they stand ready

Shoulder to shoulder in formation heady

Let us do our part to not give them cause To be alarm but to receive our applause

Bless their hands, their hearts, and their minds

For in their work reveals humanity’s kind

Look beyond to their long and tall shadows

For the billowing capes of our healthcare heroes!

HALCYON , Evelyn Syau, MS3

Dancing brightness before my eyes. While it is twinkling and glimmering shadows run away. All is illuminated colors drawn from the gray. Beauty once hidden now reviled in the light of day. Even the darkness of myself tries to hide away. Though I may fear the light it draws me closer ever still. Burning burning burning burnt, the light itself does not fade away. Warmth and its pleasure. Heat and its pain. What is happening to me? Why do I burn in the light?

LIGHTS

Thomas Varkey, M.D., PGY2, Alumni

THE BOXER

William M. Tierney, M.D.

I’m usually doing something trivial—riding my bike, mowing the grass—when a certain song from that late ‘60s (The Boxer) comes onto my MP3 player, and it never fails to pull me into a state of reverie. I first heard the song in the Spring of my senior year of high school while driving to the YMCA to play basketball. I recall the day because I had not gone for months, and when I hit the court, Greg was there, alone, practicing his jump shot.

Greg looked at me and asked, “Have you been coming here a lot recently?”

“No, first time in months,” I answered.

“Weird! First time in months for me too.” I wondered how closely Greg’s and my minds were linked, what subconscious event had sent us both to the “Y” to shoot hoops on that same day. That day and that song remain linked in my memory. We both shot well that day.

Two years previously, at the beginning of my junior year of high school, I had moved from the New Jersey shore to a mid-sized industrial town in Indiana. I was a stranger in a strange land, a surfer banished to the cornfields, and had little hope of making friends until I met Greg who lived across the street. On my first day in Indiana, he was in his driveway, shooting baskets. He and I were very much alike: same size, same

build, same smart-ass personality. I was a decent athlete, but coming from a state where baseball and football were king, I had no game. Greg took me to the local YMCA and taught me basketball. He asserted that basketball and jazz were the only two uniquely American art forms.

Greg taught me the fundamentals: the pick and roll, give and go, the turnaround jumper, blocking out, and always taking the open shot from the free throw line. Being new and having few friends and little else to do, I played a lot of “ball.” And I got good. Together, Greg and I played at the “Y” almost every week in both pickup games and leagues. We joined a team of guys from his old (rough) neighborhood and would play other neighborhood teams in games that at times resembled rugby more than basketball. We won more than we lost, and we loved it.

Greg and I were also close in school where we were both in honors classes in English, Math, and Physics. We often double dated. We went to high school basketball games together: a big deal in Indiana where, at that time in the 1960s, basketball was like religion (think “Hoosiers”). My high school gym seated 9100 people and was always packed with howling fans. After high school, we both went to the same state university, but we parted ways. He lived in a dorm and studied business while I moved into a fraternity and was pre-med.

STUDY OF POWER , Victoria Siu, MS2

We lost touch, both at school and even in the summertime when we both came home. We still lived across the street from each other, but I worked in factories and on construction crews while he worked on his family farm outside of town. We rarely saw each other.

Right before starting medical school, I got married and Greg came to my wedding. We spoke only briefly, awkwardly. We had little to say to each other. And then I didn’t see him again until my junior year of med school. I had begun a month-long rotation in Psychiatry at the state mental hospital, and as I walked through the cafeteria on the first day, Greg was sitting there, thin, disheveled, unwashed, and smoking. I learned that beginning in his last two years of college, he had progressively fallen into psychosis. He had begun to lose touch with the reality that he and I had shared, and no treatment seemed to work. Despite intensive inpatient care, huge doses of antipsychotics, and even electroshock therapy, he was still nonfunctional, paranoid, and lost.

During our month together on the Adult Psychiatry Ward, Greg taught me about mental illness, especially schizophrenia. I was shocked to learn that he knew that the things he was thinking and the voices he was hearing weren’t real. He just couldn’t ignore them. He couldn’t seem to find his way back to the reality he knew was out there somewhere, the reality he and I had once shared. He was lost, and neither he nor I could bring him back. God knows, I tried. I worked hard with him during that month, trying to fathom his illness and help him find his way out. I figured that nobody caring for him could understand him and help him as well as I. But I was ignorant and impotent, and I failed. Worse than failing, I represented the reality, the functional and successful existence, that was permanently closed to him. No matter how hard he tried, his illness bludgeoned him into submission, defeated and hopeless.

My month on Adult Psychiatry ended. On my last day, I wished Greg luck and left. I’d like to say that I thought about Greg a

lot over the ensuing months, but this was my clinical third year of med school. It was intense. I was immersed in the anxieties and excitement of hospital work, and I had no extra cerebral energy to ponder Greg and his demons.

Then, two years later, during my internship, I got a call from Greg’s former girlfriend. He had gone into his father’s barn, squirted a ring of gasoline around himself, and consumed himself in fire. Unfortunately, he didn’t die immediately. He lived two days after being helicoptered to the Burn Center in my hospital. He died there, alone, without family or friends. I didn’t even know he was in the same building in which I was putting in 18-hour days as an intern.

Since then, I have occasionally thought about Greg and the lessons he taught me, especially when working the graveyard shift in my inner-city public hospital’s emergency department where it was my responsibility to screen all patients with psychosis to rule out a medical cause for their aberrant behavior

before calling Psychiatry. Greg taught me that each of them had a past when they were not sick, not screaming or spitting on me. Greg was always in the back of my mind when I worked with patients in the hospital or my primary care practice with depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia, and lost. He taught me patience and empathy. I try to recall Greg and his struggles when faced with a “difficult patient.” And his memory also comes to me unbidden when, mowing my lawn or riding my bike, that song from our carefree high school days takes me back to a day at the “Y” and basketball, jump shots, and the demons that killed Greg and motivate me.

ADÉLIE

Hani Talebi, Ph.D., L.S.S.P.

<Background: At a birthday party for a classmate of 1.0 who is turning 8 years old. There is a very large piñata at which the children are taking turns attempting to obliterate. 1.0 and 2.0 are very comfortably waiting in line and watching in earnest as all indications point to the fact that it is a matter of seconds before the glucoseladen innards of the stuffed container are strewn about the ground and the collective jackal-esque attack will begin. The boss and I are attending to 4.0 as he has chosen this moment to simultaneously empty a juice box all over himself, mixing it with all the dirt (now mud) in which he has been playing, and screaming like a banshee (presumably to communicate to everyone the primal nature of such an activity). My eyes drift briefly, and I see that very quietly standing next to us and surveying the other children (whose frenetic energy has become palpable with the disembowelment quickly approaching) is, of course, 3.0. She is smaller than almost all the children, carrying a body which comes nowhere near matching the magnificent spirit encased within it. This is nothing new, though, and something to which she is accustomed at her current life stage. She is very intently and purposefully taking everything in and intensely focused on the moment.>

<The piñata finally breaks, and all the children rush in to collect the goods.>

<I continue watching 3.0 as she has not moved at all...she is still standing about 10 feet away from the rest of the

group but is also not looking at me or her mom for guidance or support. As we continue calming 4.0, the boss and I exchange a knowing glance: poor little child, we say with our eyes to one another. 3.0, as the second middle child, has always been the one forced to find her own way...not the biggest, not the smallest, and not a true middle. Something inside me feels sadness and worry.>

< 3.0 begins to make slow, deliberate steps toward the throng...and very cautiously finds her way to the perimeter. I can’t help but see her as a young penguin trying her very best to try and join the group so she can stay warm - but is repeatedly sent away back to the outer fringe to fend for herself. I am frustrated that no one sees her while also reminding myself to not ‘do’ anything and allow her to ‘be’ herself - process over outcome. She kneels down and reaches in between all the larger kids’ legs while turning her head back the opposite direction in an effort to blindly find any type of treat. Something else inside me hurts and feels helpless on behalf of my youngest daughter.>

<It is here that I experience a strange internal shift and find myself unable to help but think that what I am witnessing is some surreal microcosm of all my worst fears of what society has become and might continue to be for 3.0 in the future. The bigger and stronger taking from her without concern for her welfare. The disregard for her as a member of the group, of the community. The lack of empathy

and compassion for her. The vitriol and negativity that seems so pervasive everywhere these days...will she be on the receiving end of all that some day when I’m not around to hug her tightly and lift her up in my arms? The hopelessness and the cynicism... will she have no choice but to adopt it? ‘PLEASE, ONE OF YOU HELP MY CHILD!’ I find myself wanting to yell. Something inside of me breaks a little more and I recognize I am short of breath and anxious and sad and...>

<Snapping out of my distant gaze, I see that 3.0 has left the large group of children and is walking back toward us. ‘Please,’ I say to myself...’please let her have found SOMETHING. Please don’t let her be sad...please let her know kindness and a belief that it’s all OK.’>

< 3.0 has still not looked at me or her mother so we can’t tell what she is feeling and what our next steps ought to be. There is no need to say anything to one another as parents, thoughwe are both preparing ourselves to console her...to reflect her feelings...to support her in her disappointment.>

<We find ourselves confused, however, as she continues to walk straight past us without even a sideways glance.>

3.0: <innocently smiling and gently handing over all three pieces of candy she found to her little brother> “Here you go...I got these for you.”

<One final something inside me breaks...in the very best way possible.>

, Lundyn Davis, MS3

In their unsmiling eyes, weary faces halfobscured by blue surgical masks, a rumor festers.

They say it’s a China virus. Kung-Flu. They wanted to point fingers at the hidden silent killer and now they’ve found it their scapegoat in the peril yellowness of skin.

A perpetual foreigner. A young girl born in America, or beautiful country in Mandarin, her parent’s native language. She stumbles through the English language. Again and again until the lexiconic nuances flow in almost instinctual synaptic memory like an old friend.

But persistence and education does not always anticipate interrogation. Does not feel prepared when asked,

“You look oriental. Where are you from?”

“No, I meant where are you really from?”

In the quietude of formaldehyde and bodies draped in towels on metal tables, it is easier to simplify. Skin is skin.

FENCES , Alexis de Montfort Shepherd, MS3

The epithelium crumples and when you push away tissue paper and fascia, there is only blood, bone, flesh And a once-beating still heart.

From dust you came and to dust you shall return.

Pain bites against the hands who treat it, the intertwining hands of other Asian Americans who came before the young girl to heed the call of medicine, to heed the China virus.

In America, the beautiful country, obscured by blue surgical masks, a rumor festers.

ANOTHER VIRUS

Victoria Siu, MS2

bottles sit stacked on the windowsill tallest to shortest flower vases with their petals traded for pills

bedsheets pulled back perfectly dust nowhere in sight vacuum lines stretch across flawless carpet

hands tremble fingers twist lips part tongue swallows

it doesn’t matter how many round white ovals slide down my dry throat i still see the disorder everywhere

there is always something to fix always something left broken and i keep telling myself

it’s not me

it’s not me it’s not me

–– o.c.d.

Rabab Isa, MS4 o.c.d.

MAYFIELD PARK , Swati Avashia, M.D.

0SCOLIOTIC SAPLINGS

Emily McCalley, MS4

Have you seen the way trees warp?

So many barrel their way to the sky I forget their malleability.

But they’ll grow around anything!

Stone and steel and older trees— anything solider than they are, really.

Have you seen the way our bodies warp?

I forget that lean women can get leaner, that toned women can, too.

Today my kind friend rebuked my harshness and was right.

I mourned a lean woman getting leaner.

“But if that’s how she’s comfortable…” she corrected.

Sometimes I wonder if warped trees are comfortable.

A scoliotic sapling wending its way under a concrete slab is resolute and resilient and I’m sure is making itself much more comfortable.

But if I anchor the slab in its place and believe the sapling is serpentine of its own accord…

My heart sang a little last month when I met a tree that ate a power line. Ate it!

The cable runs through its trunk now and the linemen just cut the cable and made room for the tree. Its roots were bursting through the sidewalk— it had places to go!

I’m not sure if it was comfortable. I’m not sure it cared.

My heart sings a little when a woman decides she is lean enough or that she does not care.

We are each of us mightier than the concrete fingers pointed at our contours.

Embodied, we have places to go.

WHISPERS OF NATURE’S ETERNAL FLOW

Sriya Dommaraju, Undergraduate

How can I embrace life’s natural order, To nurture and bear, to grow and explore, To love and to cherish, to hold close and dear, But what if I long to linger right here, Frozen in time, surrounded by comfort’s embrace?

They say understanding purpose lets us move on, Yet I hold tight, for change feels too strong, I cherish these bonds, surpassing glimpses of tomorrow,

Not yet ready to release, to embrace the unknown sorrow.

But nature follows its course, unyielding and true, Like a bird with new wings, taking to the blue, As the wind rustles through feathers, so crisp and unfurled,

A barren nest tells of a different world.

Parents gaze with love, pure and profound, Fulfilling life’s purpose, their hearts so tightly bound, Yet nature’s thread tugs, a gentle but firm pull, While death’s scissors cut, ushering a new rule.

And so we move on, to a different nest we fly,

With a fresh purpose, under a different sky,

Mother Nature’s cycle, eternal and vast, Who am I to question her wisdom amassed?

A lost soul yearning, seeking answers in strife, Or a bird taking flight, braving uncertain life, For wings may falter, wind may blow too strong, And the gaze of love may transform into a mournful song.

Is this the natural order, the way of all things? To falter, to suffocate, as a fledgling bird’s wings? To witness love turn to despair’s piercing sting, In the grand tapestry of life’s eternal spring?

We ponder, we question, with hearts full of care, In the quest for understanding, answers we share, But ultimately, it’s in accepting the unknown, That we find solace in life’s cyclical throne.

So let us embrace the natural course’s flow, Nurture the bonds that bring warmth and glow, For in the vast tapestry of nature’s embrace, We find purpose and meaning, woven with grace.

LOSING A GRANDMOTHER TO THE

Victoria Siu, MS2

Do you remember how memory was a rope into the past that kept going and going

Along the side of a sloping cliff until it got lost in a fog

Was it laughter or heartache when you first heard someone ask

About memory

About the brain

About how the mind is a strange circuit board of chemical reactions and signals until something breaks

I’m constantly reminding you

Take two small round pills before bedtime

You liked to refuse and say to the fog you’ve already taken them

STOPPING BY A LAKE ON A SNOWY MORNING , Thomas Vetter,

M.D., M.P.H., M.F.A.

Do you remember when you started losing track of consonants and syllables

Those sneaky words that crept into tricky phrases

You told me you understood everything perfectly I pretended alongside you

But I think we both know

Registering bitterness on a blank face

Is instinctual

When you wore hearing aids for the first time

Maybe it was a chance for the mind to catch up to the ear

But the mind caught up to the ear and the ear got lost in the fog.

Maybe they’re behind the torn satin couch Steven bought for you I guess we’ll never know

Do you remember smiling and laughing when we asked you to remember?

But you just shake your head and the curtain falls anyways.

ON LONELINESS

Richard Sames, MS1

It was almost philosophical, Watching the spiders dance

Across the bay like blown leaves

As I stood in the shadow

Of the lone mesquite tree

Freshly powdered with spring.

A girl walks her dog along the boardwalk. Some guys kick a ball back and forth, And the wind does that thing to the waves again.

This is loneliness:

The sum of it all rushing by

When everything inside you goes still,

The humidity pressing against the back of your neck

As a couple goes at it over your left shoulder.

Last night I had that dream

Where I come home and Someone moved into my house. They’ve put in hardwood floors

And replaced my silverware. There is hair in the drain.

Everything was so new.

I moved near a beach for work, I watched the sun fall into the bay, I considered a dog; it was summer.

Then I worked longer hours. I spent more time in bed, I gave up on that writing group

And everything charged by.

It was Easter, A Sunday.

The bells rang all over town, I could feel them in my chest.

The sun came up over the museum

And I said nothing to no one. Unburdened, this is it.

All that’s left to do is watch

The fish surface under the spiders, As the tree rustles and the oilrigs hum In the orange of the evening.

You don’t have to pursue anything ever again – Tony Hoagland, Disappointment

Thomas Vetter M.D.,

SOULLESS , Haeley Shaw, Staff

452

Raaj Pyada, MS3

“Code Blue, Room 452 .”

Is that us? Unsure, it’s the weekend. We go anyway.

Up the elevator

Is it wrong to feel Excited?

Will they know it’s My first one?

“I have a learner, he’ll be doing Compressions.”

Oh good, I’ve been Announced.

Handoff time, I start to get a bit Nervous.

Leg half on the bed, man this is Exhausting. Keep counting, keep pressing Is it time to switch? No? Keep going.

Who is this man?

What is his name? Why is he here?

Wait. If I don’t know him then Why am I heStop. It’s not the time for that.

“Good compressions, go a bit Deeper.

The quality wanes, so it’s Transition time, be smooth, then Wipe off sweat, shuffle away Catch your breath. Check? Oh that’s ROSC.

Time to go, we walk out No debrief. No time. Others still remain, now Back to the ER

Down the elevator and Out of room

452.

Is that even the number? Months later I reflect Now it’s time but Honestly, I forget.

How to honor someone you Don’t know?

How can I celebrate?

I’m not sure he’s still here.

How can I grieve?

I’m not sure he’s really gone.

What can I cling on to?

When it’s tough, just remember ROSC achieved in room

452 .

TRACK 5, SIDE 1: THE NIGHT

THEY DROVE OLD DIXIE DOWN BY THE BAND

Tyler Jorgensen, M.D.

A haunting home visit and an all-time show stopper.

My dad taught me every epic journey deserves a great soundtrack.

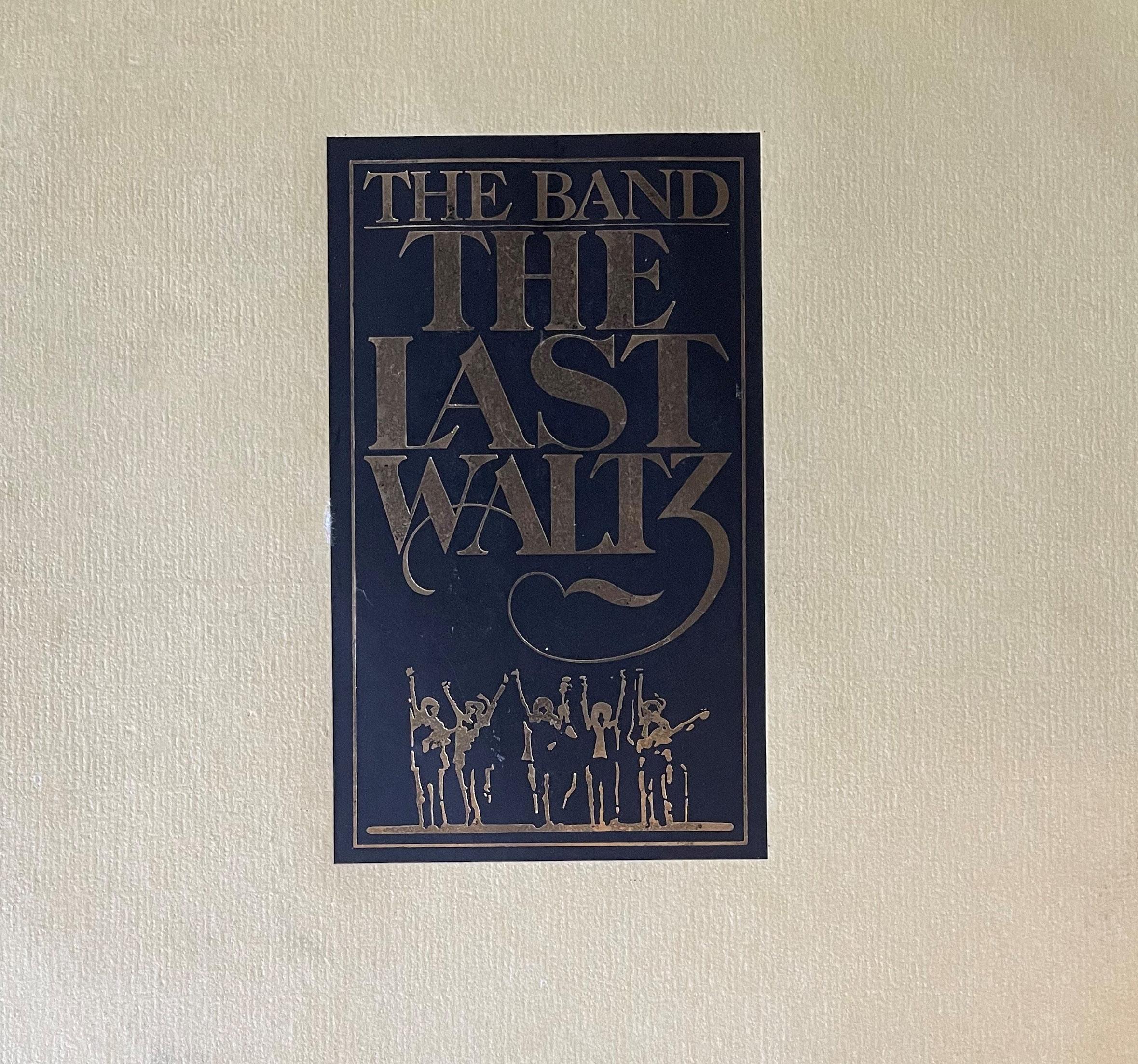

If you’ve never seen The Band’s concert film The Last Waltz, please check it out on your favorite streaming service. It’s incredible. It’s directed by Martin Scorsese, for heaven’s sake.

If you don’t have 2 hours to watch a 45-year-old concert film, surely you can spare 4 minutes. Go over to youtube and watch the clip of The Band performing The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down and prepare to have your mind blown. It is my favorite filmed vocal performance of all time. Levon Helm is an absolute maniac, keeping it tight on the drums somehow while simultaneously singing with the passion and desperation of a starving rebel taking his last stand. The exaggerated pause at the end of each verse, the synchronized salvo of explosive harmonies on each chorus, even the fist pump from lead guitarist Robbie Robertson as the momentum builds…it’s everything you want from a band at the peak of their powers.

It’s also a great song to tell the story of a home visit that still haunts me.

Until this fellowship year, I had never cared for patients in their homes. What an adventure that has been! (And all this time I thought the ER was a raw experience!) I learn more about my patients’ lives in two minutes of seeing their homes than I could in a lifetime of clinic visits. I’ve learned I never know what I’m gonna get. On home visits I get to pet dogs, touch quilts, study photos, and admire charming heirlooms that would fetch a mere few dollars in a garage sale, but that in these homes are priceless mementos. Just as often I get to bear witness to the mess, the filth, the foul smells, the poverty, and even the loneliness and despair. Regardless of whether I like what I find in a home, at least it’s honest, and it always helps me understand how to best care for a patient.

Now, I don’t mind chopping wood / And I don’t care if the money’s no good / You take what you need / And you leave the rest

Driving out to Jerry’s place west of town for a home visit was an ordeal. We wove along roads that progressively narrowed—paved, then gravel, then dirt—dodging dogs and loose livestock all along the way. Jerry’s friend met us and walked us down a path to the old aluminum shell of a trailer where Jerry was staying as he battled lung cancer. He had missed his most recent follow-up appointments.

I’ll be honest, I wasn’t too surprised to see an old confederate flag on the wall as I stepped into this sad, stuffy space. Confederate flags are still fairly common in small town Texas. Mixed in with the flag I saw some more artful tapestries, but the faded colors of Dixie still popped. Really, man? I thought. It’s 2023. Can you not take that flag down?

Like my father before me / I work the land / And like my brother before me / who took a rebel stand / he was just 18, proud and brave/ when a Yankee laid him in his grave

As my eyes further adjusted to the dark inside this hot trailer, I scanned the clutter and found jumbles of pill bottles scattered helter-skelter around the room, half-consumed bottles of Ensure, flies feasting on food that Jerry hadn’t touched. Then I saw Jerry himself, a specter lying in the dark, and his body revealed instant clues to the severity of his disease—his labored breathing, his gaunt features, the exaggerated convexity of his chest, each rib so distinct with no muscle or fat left to cover them. Sweat dripped off his pale body as he cried in pain. We got him some of his pain medication and quickly made the decision to call 9-1-1. He clearly needed immediate attention and was not yet ready to embrace the finality of hospice at home. He was among the sickest patients I’ve ever seen outside of a hospital. I caught myself staring.

In the winter of ’65 / We were hungry, just barely alive

After some long moments I snapped myself out of my trance and forced my gaze away. As my eyes drifted up from their hypnotic fixation on his ribcage, I saw something equally as sick as Jerry’s lungs—a full-size swastika flag on the wall right above his bed.

I had missed it at first, but there it was. Crisp and clean. This was no historical artifact. This was a freshly made, recently purchased SS swastika flag. Now I started to feel sick.

Some still argue (albeit with less regularity and much less credulity than in the past) about what the Confederacy’s

Stars and Bars may represent to white people in the South in 2023, but there’s no denying that a swastika represents hate, antisemitism, evil, and white supremacy. The ceiling of this nasty old trailer had just gotten a whole lot lower. I felt the walls closing in.

A question has echoed in my head ever since that day. How should I handle the tears of a Nazi? I had recently been reading some of the essays of the Trappist monk Thomas Merton who dealt regularly with questions like this.

Merton wrote that, for him, empathy came from an understanding that his own faults and shortcomings were as great as anyone else’s. He believed that, deep down, he was capable of any of the monstrous depravities he saw in his society and in the world at large. To Merton, the fact that he had not traveled down certain dark paths was merely a reflection of God’s grace. He must therefore extend love to all persons.

Beyond that, Merton felt a responsibility to engage with the societal problems of his times. He didn’t like that he had to deal with the realities of Auschwitz, Hiroshima, and Vietnam—all of which happened during his lifetime—but he felt he had no choice. These were the times he was born into. He didn’t get a pass, and neither do I. I have to find my role in the midst of this messy society, and that can look different on different days. On that particular day, in my role as this man’s physician, it meant easing the pain of a neo-Nazi.

EMS arrived, and we escaped from this rectangle of sadness back into the bright central Texas sunlight. How should I handle the tears of a Nazi? As his physician, I should handle them the same way I handle the tears of anyone else. I should wipe them, and I should do my best to ease his pain. Even when I’d rather keep my distance.

Let’s finish this out with a little more Levon.

The night they drove old Dixie down / And the bells were ringing / The night they drove Old Dixie down / And the people were singing / They went, “Na, la la na la la…”

I LOOK NOT TO MY PAST

Justin Jensen, MS2

This poem was written from the perspective of someone who had to face their own mortality, and instead of being consumed by this mortality, they chose to overcome it. I had contemplated the feelings of anguish and uncertainty in this moment and had realized that we all have time limits on our journeys. But that does not mean we cannot add time to other peoples lives. The obvious way to do this is to equip healers with the skills to subdue uncertainty for their patients. Our Willed Body patients do exactly this; they provide the initial canvas for us to learn the sacred art of medicine. Their contribution to medicine ends up contributing to the healthcare of countless lives. In this spirit, I realized they were not victims of death, but rather had the ultimate weapon in pestering death for generations to come.

BURNOUT , Nuha Arefin, MS2

I look not at my past, a story already written.

Instead, I peer intently into the unknown.

Gripped with uncertainty, I struggle for a measure of control.

Alas, I have found my weapon against you.

A darkness that has followed me since birth.

I now make this sacrifice, a contribution of borrowed matter.

You will soon know me as victim, but they, they will know me as cadaver.

Watch as I equip them, laid upon an altar of steel.

They will huddle around me, some offering late night praise.

And for you, oldest friend.

You will soon see the army of healers I have raised.

Spinning wheel wheel wheel wheel like it when it makes a squeal

Peal out and lose your balance

Heel, fast man

Heal, my man

Take off in the stratosphere

Low gear

Peer into your old house

I see you fighting with yourself from up here

Hack away at the cacti you’re a hero down there

Slow, the bag fills up slow

It’s so unfair

How can you be you if drag that shit everywhere?

Chameleon changes but his green is worse for wear

So I say fuck it, join me up here

Mission this is ground control

This is ground control, you are too close to the sun

Turn around now.

Fuck with shooting stars

Oh, we’re weightless now

Proof we were down on Mars

Ah, they can’t touch us now

Stopped to ask some Martians if we’d gone too far

Immersed in the silence it’s so loud

Pantomime the light year

Will it work out up here?

Martians touched our minds saying “have no fear”

Out in the middle of this space time realm

We made contact.

Mission this is control. It’s just me, I’m the only one left.

I was wondering, I’ve got a question: you’re up there all alone, so who are you talking to?

Maybe that’s why you talk to yourself up there

Maybe that’s why

You laugh at the walls

You take it all in

The bashful evolve

But you just get lost

And eaten by laws

That split up your psyche

And tickle your skull

Maybe that’s why

The peddles you pump

Can take you this far

Away from demand

The bar that’s so high

Keep riding your bike

Keep riding your bike

Keep riding your bike

And You

You pull in

You wake up

Your back hurts

Your rents due

The man calls

Oh

Your moms lost

Your dads done

The clock ticks

The dogs won

But strap in

It’s seven

The airs cool

THE BIKE

Sam Burr, MS3

Your wheels pumped

So ride on and escape your world

GUADALUPE MOUNTAIN MOSEY , Molly Van Dyke, MS1

DEADLY EARNEST

Thomas Vetter, M.D., M.P.H., M.F.A.

September 1980. I enter garishly lit, austere, gross anatomy lab with khaki concrete block walls and khaki tile floor. In swirling sea of khaki, I see two neat rows of long, stainless-steel metal tables: each with large, thick, black bag resting within perimeter of its four, raised, square edges. Shape of each bag conveys contents. Crowded room hushed: only murmuring voices appropriate. Brainstem response: dry mouth, sweaty palms, wave of nausea. Don’t puke!

Cautiously unzipping assigned bag reveals earthly remains of intact human body—with eyelids thankfully closed by meticulous diener; sallow skin like soggy, thick animal hide; and numbered toe-tag. Unforgettable chemical smell of preserved cadaver, offgassing volatile organic compounds (VOCs), assaults my virgin nostrils: strong, sickeningly sweet and tarry, pickle-like odor.

Meeting your cadaver is one of most memorable events in medical school and rite of passage. Considering intense focus—and reverence of ensuing ten-week learning effort—I suspect in some cases, ironically, more attention is lavished on such human body after death than during life.

Our team of five, first-year medical students is assigned to anonymous male cadaver, an elderly gentleman, whom we fondly name Earnest. In what is first of many expressions in our careers of compensatory, medical gallows humor, we five, twenty-something compatriots

and fledgling doctors often note how we are diligently working—in “deadly earnest.”

Given human body’s symmetry, two of our team of five—me included—become main dissectors, while two others stand alongside, with arcane atlases and detailed manuals in hand, dutifully guiding us from epidermis to viscera. Our fifth team member? They float about room, making social rounds, stopping back at our table from time to time, to take note of our painstaking, slow progress in uncovering the complex anatomy buried in dear old Earnest.

George, my fellow dissector and soon trusted friend, is accomplished artist by avocation and talented plastic surgeon in making. Not surprisingly, like Michelangelo and Bernini, his side of our cadaver evolves into work of art as George sculptures out fine details. In contrast, my well-intended but blunt dissection of Earnest, for most parts, proves to be more anatomical tour de force, with far less aesthetic results.

Like all cadavers, Earnest has been embalmed: wellpickled in commercial combination of formaldehydephenol-glycerol. We regularly spritz Earnest with special wetting solution to prevent his muscles and connective tissues turning into stiff jerky. We do not wear medical examination gloves while dissecting— except unpreserved, thus not disinfected, and possibly prion-laden brain, removed like soft walnut from its hard shell by jagged teeth of old bone saw.

During every afternoon of dissection, human tissue accumulates under my fingernails. My white lab coat is always soiled with body fluids and greasy from Earnest’s ubiquitous fat. Saturated by vapors of potent preservative, my sense of smell evaporates. Heading home in late afternoon, I enjoy watching facial expression and body language of normal folks sharing elevator ride to ground floor. They grimace, breath through their mouths, move as far away as possible from my classmates and me, then dart out once door opens. Don’t eat with my hands.

One winter Saturday night it’s nearly zero degrees outside. I have been studying in my apartment all day—when around midnight, I get this urge to complete my dissection of face, specifically, internal carotid and external carotid arteries and their branches diving deep into face. I bundle up and make my way on foot through frozen, empty streets to medical school. Gross anatomy lab is open 24/7. It is magical to be alone in room with Earnest, exploring beauty of vasculature of his face.

PACEMAKER , Saurin Gandhi, D.O.

Somehow, it suddenly becomes crystalline in my head, an anatomical epiphany. And for once, it is my side of Earnest’s sacred body that looks like idealized textbook image and Renaissance or Baroque marble sculpture.

Yet, such moments of complete understanding and absolute mastery are rare and fleeting for me during my first two years of medical school, amidst crush of absurd course load, and seemingly endless, completely senseless memorization and regurgitation of minutia: wash, rinse, and repeat, ad . It is a terrible time in my life—dominated by relentless academic pressure, omnipresent exhaustion, and my pervasive inner fear of failure: all stoking my own state of nihilism.

On that frigid, winter night, I mutter to myself, “I should have instead gone to law school.”

Earnest listens, smiles, and whispers to me, “Well, my young Doctor ___, maybe you will in your next life. By for now, have faith and remain earnest for me.”

HEAVENLY DEBAUCHERY

Richard Sames, MS1

When you die and get to heaven

It’s perfectly natural that the first thing you do is Get rip-roaring drunk and spray-paint the word vagina

In neon blue and all caps on the first wall you can find, Illustrating that from now until forever and beyond, That you won’t give a fuck.

Then, maybe you’ll toast St. Peter, Demanding, with your gin soaked tongue, To know why the Pearly Gates are actually a smoothly sanded Redwood, And whether or not that’s your halo

You feel pressing lightly against the back of your neck.

You’ll scream, cheer, and twist, And probably wonder why The celestial floor feels more like worn-out concrete, And if the spittle running down your mouth and into the cracks, Will make its way back to Houston.

After all, what else is there to do, When you’ve spent the last sixty years or so Performing morning sun salutations, Politely passing up the occasional celebratory cigar, And watching your sodium intake?

You counted calories. You brewed Kombucha, And every night before bed, You constructively reviewed your day, To James Taylor’s You Can Close Your Eyes.

So when Death comes to you as a ’59 Volkswagen Beetle, With one broken headlight and no license plate, Leaving you lying in the middle of the road, Nose crooked, mouth open like a busted shoe, What else is there to do,

But lie still, give thanks, and salivate over The bottles you’ll soon knock back in eternity, As the diamonds fade from your eyes?

SORROWFUL GRACE, Ayla Farzamnia, Undergraduate

CICADA, Will Austin, MS3

AUTOPSY

Rabab Isa, MS4

I am so sorry we did everything we could to save you but it wasn’t enough.

It is never enough. If my medicine of poetry, science, humanities, compassion, art, mixed with antidepressants, therapy, psychiatrist visits, & more therapy was enough, your corpse would not be lying here in this cold sepulcher decaying alone.

My dear friend, you had what we call a terminal illness, No medicine or therapy could’ve kept you alive.

But maybe they’ll read your obituary or your tombstone: Here Lies Physician Empathy, A Girl Who Wanted To Do Something That Mattered. 1998–2023.

And maybe they’ll find a cure but I’m not so sure, so I close your eyes. My lonely voice calls out for no one to hear: “Time of death, 23:19.”

GRIEF FELT

Thomas Varkey, M.D., PGY2

One little hand to never be felt. Slowly my eyes begin to melt. What a hand I have been dealt. Nowhere is my body left to dwelt. There is nothing but pain to be felt. And Yet the rain outside continues to pelt.

HOUSE, Georgia Williams, MS4

UNKNOWN STRETCH

Michelle Bach, MS4

Backbends, toe touches, sit and reach test Made her feel invincible in her third grade PE class. Others struggled to bend and move their joints With the ease and flexibility, she possessed.

“But how the tables have turned,” she shared. Cuts and bruises marked her body As it struggled to heal from painless wounds. While bones and joints burned.

Learning to live with pain, Not understanding the cause, And without the acknowledgement of others. She yearned for the pain to pause.

TMJ, costochondritis, dyspareunia, dysautonomia, Words engrained in her medical record, A steadily growing list.

With the body’s every battle, Anxiety came with uncertainty, Depression came with pain. To breathe again, an advocate she became.

Physical therapists, psychiatrists, Primary care physicians, surgeons, On this journey to unlock this mystery, Stood by her and searched endlessly.

After thirty years of incertitude, Five Beighton maneuvers provided clarity, Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos, An answer to her unknown stretch; gratitude.

GRIPPED BY SILENCE, Ayla Farzamnia, Undergraduate

MAISIE, Haeley Shaw, Staff

MEDICINE

Richard Sames, MS1

In an effort to be happier I’ve decided to spend less time Thinking about the job that I hate And more time listening

For the smallest hint of audible frustration As you follow around our dog on the front porch Trying to dry her paws after 15 minutes Of still settling rainstorm mud. Maybe it’s ridiculous, But I’m ashamed of the failure of the English language To properly describe your position, Something like a squat and lean, Two handfuls of inherited, embroidered towel And a furrowed brow.

You reach forward and fall slowly. Happy for the attention, The dog retreats and rolls backward. She looks directly at you And sees only you, But not for the way your hair Folds beneath your right ear, Or the way the remaining spring sunlight Reflects off the crook of your right clavicle, But rather just because you are here and she is there And she wants what you want Except she doesn’t know what that is, Because all she knows is that this moment Like all other moments, Is extraordinaryNot because of what is happening, But rather for the fact That whatever is happening, Is happening at all, So she reacts on her most basic instinct And does what she thinks will amplify your happiness And because you’re on the ground And you’re still reaching forward And because I share the same instinct, I think she guessed correctly.

Prosody, the student-run literary and arts magazine of Dell Medical School, brings together student, resident, fellow, faculty and staff voices to explore the intimate connection and meaning inherent in the practice of medicine through prose, poetry and visual arts.

Read Online: Prosody.DellMed.org