Marionas: the guitar music of Francisco Guerau

Gordon Ferries baroque guitar

1. Marianos [?.??]

2. Jacaras de la Costa [?.??]

3. Marizapalos [?.??]

4. Pasacalles por Patilla, 8 tono, punto alto [?.??]

5. Gallardas [?.??]

6. Pasacalles por 3 tono [?.??]

7. Villanos [?.??]

8. Folias [?.??]

9. Canario [?.??]

Total playing time: [?.??]

Francisco Guerau’s Poema Harmonico (Madrid 1694) is arguably the finest body of guitar music from seventeenth-century Spain. Beautifully engraved and beautiful in conception, it represents an apotheosis in the baroque guitar’s transfiguration from a simple folk instrument to one capable of the highest artistic expression. Guitarist, composer, violinist, singer, priest and writer on theology, Francisco Guerau was born in 1649. As a ten-year-old he became a member of Charles II’s royal Chapel of Madrid’s ‘little singers’ employed as a boy treble or cantorcico progressing to a male alto, ‘with a very fine voice’. Guerau tells us in the preface of his book that by the year of its publication in 1694 he had been in the royal service for thirty five years advancing from singer to ‘composer to the royal Chapel’ and finally to the post-of-master of the college.

The path of Guerau’s career enabled him to live comfortably as well as facilitating the publication of his Poema Harmonico (dedicated to Charles II) alongside his theological writing

amor and Alerta que de los montes.1 The Prologue to the aficionado, given after the dedication of Poema Harmonico, hints as to Guerau’s character. He describes his own ‘meagre ability’ and chastises himself for the delay in publishing his book. Further to this, and with humorous overtones, he acknowledges the inappropriateness of a priest providing ‘example and cause of entertainment’ instead of ‘example and cause of virtue’ describing his works as morally neutral unless put to ‘bad use’ – an allusion perhaps to the ecclesiastical authorities’ ambiguity towards some dances used by Guerau. He was obviously held in the highest esteem by his musical colleagues; Santiago de Murcia stated that ‘All amateurs have read this singular book published by Don Francisco Guerau.’2

Recorded in Crichton Collegiate Church, Edinburgh on 9 & 10 April, 2007

Recorded with 24-bit stereo technology

Producer: Paul Baxter

24-Bit digital editing: Adam Binks

24-Bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter P

Design: Drew Padrutt

Photography: Delphian Records Ltd

Photograph editing: Dr Raymond Parks

© 2007 Delphian Records Ltd 2007 Delphian Records Ltd

Made and printed in the EU by Delphian Records, Edinburgh, UK www.delphianrecords.co.uk DCD34046

Declaraciones sacras sobre los Evangelios (Valencia, 1698). Apart from his guitar book only three vocal works are extant: Que Lleva el Sr. Sgneva for three voices and two secular villancicos or tonos humanos: O nunca tirano

Alongside the sheer quality of its contents, Guerau’s writing for guitar is significant in other ways. Published around twenty years later than Gaspar Sanz’s guitar books,3 Guerau makes no similar allowances for beginners, establishing from the outset that this book is not for them.

1 MSS 3880 and 3881 Biblioteca Nacional Madrid

2 Resumen d’accompagñar con la partie 1714 (facsimile available from Editions Chanterelle)

3 Intruccion de musica sobre la guitarra Española 1697 (facsimile available from Minkoff)

He eschews his contemporaries’ practice of including strummed (rasguedo) versions of the popular grounds and ballad melodies of the day, favouring an almost completely plucked or punteado style. The composer likely assumed a familiarity of these formulae and chord sequences in the same way that in our time an advanced book on jazz improvisation would make such assumptions in terms of the genre’s ‘standards’. Another significant departure is the absence of miniature pieces of the type given in Sanz’s book,4 with Guerau demonstrating a much more extended compositional approach, wringing every possible nuance from his sometimes scanty source material. The Poema Harmonico consists of sets of variations or differencias based on entirely Iberian dance forms, unlike his contemporaries who often include pieces in the French style (such as the suites found in the works of Santiago de Murcia).5 This is not to say that Guerau lacks the cosmopolitan outlook of Sanz or Murcia; he encases the elegance of French music skilfully within a Spanish framework. Guerau uses this potentially restrictive framework with a

liberating ingenuity, at times belying the simple harmonic patterns within which he works.

In his introduction Guerau indicates clearly a particular stringing which includes a low octave or bourdon on both the fourth and fifth courses,6 giving a truer bass than in the systems recommended by contemporaries such as Sanz who favoured an entirely treble stringing. Guerau’s music is entirely suited to the possibilities of his preferred system as Sanz’s is to his. Following the composer’s stringing system instructions allows us to hear the music exactly how the composer desired it to be heard, an exhilarating experience for the performer. In terms of ‘right hand technique’, the composer elects the thumb for the low strings and the index and middle fingers for the higher ones, differing from the alternation of thumb and index finger already established in lute playing and closer to modern guitar technique.

Guerau describes five types of ornament employed in his music: the estrasino or slur where strings of notes are plucked by the left hand only; the aleado or trill;7 the mordent; vibrato, and arpeggio. In his introduction he states that:

The most beautiful thing of all is a continuous series of trills, mordents, slurs and arpeggios; for although in truth, if the music is good and you play it in the correct rhythm and if the instrument is properly tuned it will sound well, nevertheless, if you use these ornaments which are the soul of music, you will see the difference between the one and the other.

Once inside the music of Poema Harmonico, it becomes easy to understand the composer’s words. In some of the more lively dances with strong rhythmic drive, the ornaments do not change the music internally. In the passacalles, however, the ornamentation is indeed the ‘soul’ of the music which is intrinsically linked to the overall aesthetic.

Guerau’s diplomacy is evident when he goes on to say: but anyone who cannot play with continuous trills, mordents and arpeggios should not despair, nor be discouraged: he should play the figures even without the ornaments, for they are not an inviolable law; I am only pointing out the best way to anyone who wishes to play this music.

4 Sanz compresses eleven miniature pieces on to one page

– Clarinas y trompetas con canciones muy curiosas etc.

5 Full suites in the French style with some Spanish variants are included in the publications mentioned in notes 2 and 3.

6 The baroque guitar has five courses or sets of strings. Various stringings were in vogue including the so called re entrant tunings where the lower strings appear an octave higher, as was Sanz’s preference. Guerau’s lower and higher octave on the two lowest courses suits his intentions perfectly. The type of stringings used for the baroque guitar remains a much-debated area among performers and academics alike. For a fuller discussion see Baroque guitar stringing a survey of the evidence, Monica Hall. (Lute Society, 2003).

7 The trill is described in some Spanish sources as starting on the principal note moving to the note above, differing from the more conventional French baroque upper note trill. The former appears to have been Guerau’s preference.

It may appear odd to us when exploring the beauties of Guerau’s music that it could be, in the composer’s words, put to ‘bad use’. It seems more than likely that he was referring to the well-documented obloquy of the church towards the sensuality and, in some cases, overt sexuality of the danzas – in particular the bailes, popular during the period. Dances such as the zarabanda carried severe punishments if danced in public and others were seen to have diabolical associations, especially if used theatrically as was often the case. Alongside this general ecclesiastical disapproval, the guitar was seen in some circles as inferior to the lute and vihuela.8 The initial ignobility and low associations of the instrument gradually changed as its repertory became respectable in

8 The vihuela was a six course insrument shaped like a guitar but tuned like a lute. It flourished throughout the second half of the sixteenth-century; its ensuing decline in popularity was blamed by some on the arrival of the guitar.

Baroque Guitar

based on various seventeenth century Venetian models, principally after Sellas

–Martin Haycock (2004)

–Martin Haycock (2004)

the hands of guitarist/composers such as the Italian Francesco Corbetta who elevated the guitar’s status to one suitable even for royalty.9 The church, whose attitude towards dancing remained highly suspicious, began to accept the musical aspects proffered by its forms. The sacred villancico became a staple part of the festive and pungent atmosphere of the Spanish baroque church. Church composers began to set sacred texts to dances such as the jacaras – with its lugubrious connotations, theatrical associations and heady rhythms. This unlikely coupling also perfectly adheres to the Counter Reformation ideal of the arts; appealing to both the human and the divine. Perhaps church leaders thought appealing to popular tastes a worthwhile compromise during this crucial time in religious history.

As a priest, Francisco Guerau must have been aware of this dichotomy. The instrumental format of his music ensures theological or religious ideas cannot be evinced. To the common people a jacaras outwith a sacred context would be associated with dance and the very theatrical productions frowned upon by the church. In the case of the marizapalos

9 Corbetta succeeded in ingratiating himself with both Louis XII in France and Charles II in England.

or marionas in the major mode (both featured on this recording), the melodies and chord sequences are directly associated with a ballad of very sensual nature concerning the machinations of a beautiful young girl. It includes the lines: Marizapalos was a girl, In love with Pedro Martin, Esteemed because she was the priest’s niece, The toast of the town, the flower of spring.

Further on, the text becomes more suggestive;

Turning her head towards him, She pretended only then to notice him; So great was her delight and laughter, That all caution was thrown to the winds.

The ballad ends with the couple almost caught in flagrante delicto

‘Twas the priest on his way to the grove And if he had come onto the scene a little earlier, Knowing grammar as he did, He would have caught them out in bad latin!

M. López de Honrubias (1657)As well as the mocking tone levelled at the priest in the scenario, the Spanish text is littered with double entendres which are lost to us in both culture and translation. Guerau’s apologetic tone in his preface may be in part to exculpate himself, knowing well the lubricious overtones of his chosen sources – hence his need to describe his works as ‘morally neutral’.

Meaning literally ‘to pass through the street’, the pasacalles originated in early seventeenthcentury Spain and was most likely performed outdoors, given its title. The earliest literary reference comes from 1605 and the first musical examples come from the guitar alphabeto books.10 In France and Italy the term referred to ritornello sections played between strophes. During the seventeenth-century the guitar’s repertoire was intrinsically linked to the pasacalles, with composers demonstrating their skills by presenting a series in differing keys using variation form. Guerau presents us with no fewer than thirty examples, two of which are recorded here; the Pasacalle in the 3rd tono (e minor) is on a grand scale, using motifs that would not be out of place in a French overture.

10 The alphabeto system was a series of letters to signify various strummed guitar chords used to provide an accomplishment for singing, dancing or instruments.

The Pasacalles de patilla 8° Punto alto (A major) is an altogether more introverted work which comprises sublime music displaying the guitar’s most diaphanous textures. In general, Guerau’s sets of variations are longer than most of his contemporaries. The term pasacalles remains in use in Latin American music today describing ritornelli in popular dance music, due – most likely – to guitar strumming conquistadores!

The marizapolos is a triple time dance linked to the pasacalles. The earliest versions give the name as Mari Zápalos. The ground is unusually long at eighteen bars and in Guerau’s version the new variation begins on the closing bar. The Marionas is a major mode variant of the marizapalos and was utilised frequently in theatrical productions. Guerau’s version is interchangeable with the chaconne – another staple of the guitar repertoire and again of Iberian origin. Guerau adheres to the usual tonality of the marionas, C major, based around the alphabeto chord of B. This joyous set of differencias shows the composer’s melodic flair at its most effortless.

The word gallardas comes from the Spanish for elegant or dashing. The gallardas is the Spanish version of the galliard popular around Europe

in the sixteenth- and seventeenth- centuries. Normally in triple time, it was exemplified by the tripping syncopated rhythms of Dowland’s lute galliards, often reworking material from the preceding pavane. In Spain however, especially in guitar sources, the gallardas also existed in duple time as is the case with Guerau’s set of variations alongside those of Sanz and de Murcia. Sanz also gives us a major version in alphabeto. The slow chordal movement across a fast metre provides an intriguing range of possibilities which are fully exploited by Guerau who employs a broad range of styles in his set of variations in d minor.

hemiola formula, making it rhythmically less complex. Its simplicity is no barrier to Guerau’s creativity as he weaves a beguiling set of four bar variations exploiting the guitar’s full register. Strummed versions of the villano and other dances, although omitted by Guerau, have been included in this recording, taken from versions by Sanz and de Murcia and by harmonies implied by the composer.

In Spanish the word villano has two meanings implying both villain and peasant. Essentially a sung village dance in duple metre, the villano thrived in Italy and Spain during the sixteenthand seventeenth-centuries, the first mention of it being in 1554. Numerous literary references exist including those made by Cervantes and Lope de Vega. A melody for it appears in De musica libri septum (1577). Brinçeño (1642) provides us with alphabeto notation and two accompanying texts. Choreography for the villano also survives, described by Navarro (1642). The dance has the same harmonic structure as the canario but without the

The canario is a lively villancico from the Canary Islands, also known as the negrilla when associated with the black population of the islands. The canario follows the typical Iberian hemiola formula of 123/123/12/12/12 which gives it its wildly syncopated flavour. The dance was originally accompanied by zapateado or foot stamping, wild movements and jumps. The canario became popular all over Europe in the seventeenth-century becoming known as the canary. Many notable examples are extant, including pieces by Purcell, Lully and Couperin.

The Spanish version of the dance generally employs equal notes (as in the example recorded here) as opposed to the rest of Europe where dotted rhythms were more prevalent.

in relation to music and dancing go back as far as the fifteenth-century. The term describes two forms; an early and a later variant which became known under the French name ‘La folia’ or Folie d’Espagne, whose emphasis on the second beat is closely related to the French sarabande. The folia was also sung as well as danced with an example of a text again given by Brinçeño. Guerau’s twelve variations generally stick to the older form but with some rhythmic elements of the new. He gives us no hint of the madness implied by the title and instead offers us a serene interplay among the parts, greatly enhanced by his preferred use of octave stringing.

rambunctious of the danzas, the villancicos de jacaras became a staple in church music and maintained the lively cross rhythms of the original. Guerau’s variations display a subtle virtuosity which stretches the form to its limits.

Guerau’s Poema Harmonico offers us a fascinating insight into the artistic potential that exists within popular music. Working only with home-grown Spanish dances, he created a work of individuality, technical demand, sensuality, great artistry and above all, an intense expressive beauty.

The word folias is Portuguese in origin meaning mad or empty headed. References

Even to modern ears, the jacaras is instantly recognisable as being of Spanish origin. Its rhythm and harmonic flavour are still very much alive in the flamenco tradition today. The word, as well as referring to the dance, was also a short theatrical piece in which villains and rogues or jacaros took leading roles. The jacaras’ momentum is provided by a spiky two-against-three rhythm between tonic and dominant. It was conventionally in the minor mode although the Jacaras de la costa seems to have been a regional variation in the major. Despite being one of the bawdiest and

© Gordon Ferries, 2007 This recording is dedicated with love to the memory of my father Gordon Raymond Ferries.Having initially studied classical guitar at Napier University, Gordon Ferries went on to study at the RSAMD where he specialised in lute and early guitar music. He has now established himself as one of the UK’s leading exponents of the baroque guitar; two previous recordings of French (DCD34011) and Spanish (DCD34036)

guitar music have been internationally acclaimed – Goldberg Magazine awarded La Preciosa platinum five stars. Gordon has worked for both television and radio: arranging and performing music for Radio 4; featuring on ‘Scotland’s music’ with Concerto Caledonia,

and for BBC 2 television. He has performed in venues and festivals across the UK both as a soloist and in ensemble and has appeared with The Scottish Ensemble, The Scottish Early Music Consort, and the Edinburgh Quartet, amongst others. Gordon directs his own group Symphonie des Plaisir.

Gordon has been awarded two grants from the Scottish Arts Council towards study at the Bibliotheque Nationale de Paris researching the baroque guitar; the fruits of which appear on his recordings. He lectures in lute and guitar at Napier University in Edinburgh, and is involved in teaching young people in many musical styles.

Les Plaisirs Les Plus Charmants: Works for French Baroque Guitar

Gordon Ferries, baroque guitars (DCD34011)

From its earliest beginnings, the five course Baroque guitar was associated – for better or worse – with dance music, becoming the sensuous younger cousin of the lute or vihuela. In this mélange of music from seventeenth-century France, Gordon Ferries weaves a tapestry of sound that is at once elegant, earthy, and utterly timeless.

‘Gordon Ferries is an expert in his field, and picks his way stylishly on period instruments through the selection of suites, chiaconas and other numbers.’ – The Scotsman, August 2003

The Red Red Rose: Concerto Caledonia

Songs and tunes from 18th century Scotland

Mhairi Lawson, soprano Jamie MacDougall, tenor directed by David McGuinness, harpsichord (DCD34014)

Concerto Caledonia bring their exuberant flair for early Scottish music to love songs from the time of Robert Burns, and baroque/Cape Breton virtuoso David Greenberg brings along some wild fiddling from the Golden Age of the Scots violin. The original version of Robert Burns’s most famous song The Red Red Rose appears here in its first ever recording.

‘The funkiest album of Burns songs I’ve ever hear… a fresh look at Scottish music in the 18th century: outstanding playing and the singing is characterful and expressive.’ – BBC Radio 3 CD Review, January 2005

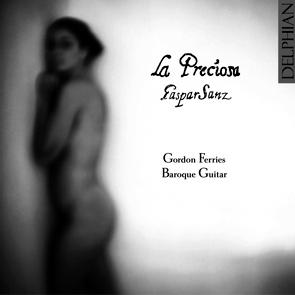

Gordon FerriesLa Preciosa – The Guitar Music of Gaspar Sanz (c.1640-c.1710)

Gordon Ferries, baroque guitar (DCD34036)

Baroque guitarist Gordon Ferries visits the music of seventeenthcentury Spain’s fiery streets – a time when the five course guitar produced a sense of abject horror in the morally inclined, citing associations with popular ballads, taverns, criminality, sensuality and in particular dancing. Ferries assumes the role with panache and breathtakingly virtuosic flair.

‘Stylish and accessible baroque from an exponent whose star is in the ascendant.’

– Classical Guitar, March 2004

Love and Reconquest: Music from Renaissance Spain Fires of Love (DCD34003)

Frances Cooper, soprano

Jo Hugh-Jones, bass and recorders

Gordon Ferries, vihuela and Renaissance guitar

Marcus Claridge, percussion

Scottish early music ensemble Fires of Love serves up a feast of songs and ballads from the Spanish Renaissance and early Baroque, with a freshness critic Norman Lebrecht calls simply ‘beautiful’.

Repertoire includes works by Luys de Narváez, Miguel de Fuenllana, Luis Milán, Alonso Mudarra, and Juan del Encina.

‘...full of vitality and will soon have your foot tapping... delightfully sung.’

– Early Music News, June 2005