COLERIDGE-TAYLOR (1875–1912) PARTSONGS SAMUEL

Joseph Fort and The Choir of King’s College London gratefully acknowledge the support of the individuals and institutions who made this project possible. The clergy and staff of All Hallows’, Gospel Oak (in particular, Fr. David Houlding) graciously allowed us to use their church for the recording. The staff of the Dean’s Office of King’s College London (Ellen Clark-King, Tim Ditchfield, Clare Dowding and Natalie Frangos) provided considerable administrative and logistical support.

Recorded on 24-26 February 2023 in All Hallows’, Gospel Oak

Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter

24-bit digital editing: Jack Davis

24-bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter

Design: Drew Padrutt

Booklet editor: Henry Howard

Cover image: Siobhan Louise Riordan,

Portrait of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, 2018, © Siobhan Louise Riordan

Session photography: foxbrushfilms.com

Delphian Records Ltd – Edinburgh – UK www.delphianrecords.com

@ delphianrecords

@ delphianrecords

@ delphian_records

Notes on the music

It may seem unlikely today, but towards the end of the nineteenth century, the partsong emerged as a key battleground for national musical pride. Secular choral settings in English became immensely popular and at their heart was the celebration of British Romantic poetry. Large amateur choirs and choral societies throughout the country took on this rapidly expanding repertoire and publishers raced to keep up with demand. For the key composers of the English Musical Renaissance, such as Stanford, Parry and Elgar, part of the impetus was to prove the suitability of English as a language for musical setting, as a parallel to the celebrated song traditions on the continent. It was also seen as a key area of development, alongside the larger genres such as the symphony and opera. The goal was to not only match, but intensify, the emotional experience of the verse. At the same time, the genre often looked back to earlier periods and particularly the Elizabethan madrigals, which were often programmed alongside contemporary repertoire. Celebrated examples, such as Stanford’s exquisite setting of Mary Elizabeth Coleridge’s The Blue Bird, became exceptionally popular and were seen as blueprints for a particular style of setting which prioritised the manipulation of mood and atmosphere.

of novel tonalities or harmonies simply for momentary effect had to be avoided at all costs. By 1890, when Samuel Coleridge-Taylor entered the Royal College of Music as a student, the compositional ethos of the RCM had English verse at its heart, to the extent that another of Stanford’s celebrated pupils, Herbert Howells, later claimed Stanford taught two things: poetry and music. Partsongs often celebrated natural beauty, and the challenge was in expressing this with a harmonic richness, while keeping to a small number of vocal parts and a level of technical difficulty that amateur ensembles could manage. Despite these perceived limitations, many of Stanford’s pupils, including Coleridge-Taylor, Wood, Bridge, Howells, Vaughan Williams and Holst, wrote significant numbers of partsongs.

For Stanford, this was often about simplicity. Every note had to be justified and the use

The career of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was defined by the success of the choral work Hiawatha and his subsequent premature death; however, more recent reassessments have come to appreciate a much wider repertoire, acknowledging his considerable achievements in a number of fields. The partsongs represent another piece in this jigsaw. In Stanford, Coleridge-Taylor found not only a dedicated teacher, but also one who was equally invested in reconciling elements of his own (Irish) cultural heritage into classical forms, not unlike Coleridge-Taylor’s assimilation of African melodic features.

Coleridge-Taylor was born in Holborn in 1875. His father, from Sierra Leone, studied medicine in England (including a period at King’s College, London) but had left the country before the birth of his son. His mother gave him the middle name Coleridge after the founder of the English Romantic movement, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and the composer later took the form Coleridge-Taylor. The combination of difficulties created by his broken home and racial attitudes of the period were somewhat alleviated when his early musical promise led to a place at the Royal College of Music from the age of fifteen, assisted financially through the generosity of a silk merchant who was a governor at his school. In an obituary article, Sir Hubert Parry commented that ‘when Coleridge-Taylor came to the Royal College of Music he was accepted on terms of full equality, and soon won the affection of every one with whom he came into contact’. Despite his early promise on the violin, Coleridge-Taylor was soon drawn to composition, becoming one of Stanford’s pupils in 1892 and gaining a prestigious open scholarship a year later. In total, he spent seven years studying there. Initial professional success came with the orchestral Ballade in A minor, written for the Three Choirs Festival, a commission he secured with the help of Edward Elgar. The subsequent trilogy Scenes from the Song of Hiawatha was immensely popular (both in the UK and in America) and was followed by the

birth of his two children, Avril and Hiawatha. The personal success of the choral trilogy, combined with the need to earn money to support his family, led to an outpouring of partsongs around this period. It was also at this time that he travelled to America and gained considerable critical acclaim, including an invitation to the White House from President Roosevelt, and this love of America is reflected in some of his poetic choices.

All my stars forsake me is a ternary setting of ‘Song of the Night at Daybreak’ from the 1875 collection Preludes by A C Thompson, later Alice Meynell, who became a key figure in the Catholic suffrage movement. In the original text, Thompson prefaces the poem with the line, ‘Night hovers all day in the boughs’, which comes from the second set of Essays (1844) of Ralph Waldo Emerson, the American philosopher and abolitionist and a key figure in the poetry of transcendentalism at the time, that focused on the intimacy of the spiritual experience. Coleridge-Taylor’s rich D-flat setting (op. 67, no. 1), dated ‘March 1905’, captures a nostalgia which is ‘sick with memories’, failing to find comfort in the natural world, but doing so in the most achingly beautiful way. Another Romantic nocturnal song, Isle of Beauty, was published posthumously in 1920, the text coming from the Songs and Ballads, Grave and Gay (1844) by the English poet and songwriter, Thomas Haynes Bayly. The lilting 9/8 setting

Notes on the music captures a refined Stanfordian simplicity as it reflects on the absence that ‘makes the heart grow fonder’. The dramatic The Fair of Almachara (1905, op. 67 no. 3) with its arresting fanfare opening, is a vivid sonic evocation of an evening at a country fair in Almachara, a town and area in the province of Málaga, nestled in the mountains of southern Spain. Coleridge-Taylor captures the ecstatic energy of the evening revelries in the words of Richard Hengist Horne.

In contrast, The Evening Star captures a more soporific mood – ‘If any star shed peace, ’tis Thou’ – from a poem by the early nineteenth-century Scottish poet Thomas Campbell. The poet addresses the star ‘of love’s soft interviews’ as ‘parted lovers on thee muse’. Coleridge-Taylor uses a Wagnerian harmonic language to express this love and given the simple SATB scoring, achieves a remarkably rich effect. By the lone seashore is a melancholic setting of another, later, Scottish poet, Charles Mackay, who is chiefly remembered today for his writing on psychology, particularly the Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. The composer captures the anxiety of the waves and the pathetic fallacy as ‘The wild wind sobs and raves’, a tension which is quickly dispelled by the appearance of a boat on the horizon, as ‘nature smiles with sympathy of heart’.

The next three partsongs express the Victorian fascination with death in different ways. The undated Requiescat, which was never published, sets a popular verse by Matthew Arnold. From the richness of the fifths in the bass, to the melodic ecstasy of ‘Ah! would that I did too’, the setting revels in the poet’s longing for death, the peace found there (in contrast to ‘mirth the world required’ in life), and the exquisite beauty of nature in the roses. The poet and missionary Kathleen Mary Easmon Simango was a personal friend of Coleridge-Taylor, born in Sierra Leone, she died tragically young at the age of 32 from appendicitis. In that context, her poem Whispers of Summer takes on a bitter irony as it captures a longing for peace, to escape ‘from the tumult of life’. The 1908 partsong Sea Drift is amongst Coleridge-Taylor’s most original. A wonderfully melodramatic piece, scored for eight parts, it sets a poem by the American Thomas Bailey Aldrich about a ghostly figure that stands on the shore at night as the sea ‘foams in anger’, the morning light revealing ‘the corpse of a sailor’. In contrast, the lightness of the pianissimo staccato opening of Tennyson’s The Sea Shell captures the fragility of the object which is ‘frail, but a work divine’. Like the shell itself, the setting is ‘exquisitely minute’.

is gone, yet in Coleridge-Taylor’s setting, notable for its descending chromatic bass lines and intense melancholy, a final repetition of the ‘Summer is gone’ moves to a warmer major tonality, which gives the setting a beguiling ambiguity. Death is also the subject of Dead in the Sierras (1905, op.67, no.2); however, in contrast to the typical English Romanticism of many of the earlier partsongs, it speaks of the American landscape and animals of Sierra Nevada, as natural life continues after the death of a hunter. The words are by the American poet Joaquin Miller, whose real name was Cincinnatus Heine Miller, and was principally celebrated for his Songs of the Sierras (1871).

Thomas Hood’s dramatic portrayal of The Lee Shore (set in 1911) returns us to more familiar English talk of seaside weather, with ‘Sleet! and hail! and thunder!’, for which ColeridgeTaylor contrasts dramatic unison outbursts with sudden homophonic sonority, the fierce allegro giving way in the second half to a gentle tranquillo, all reflecting on the dangers for sailors of being washed ashore by the strong winds.

Shelley. In two simple verses, the composer gradually builds to a grand climax and then immediately dispels all tension and dissonance on the final repetition of the word ‘Proserpine’. A masterclass in the formal manipulation of poetry in music, it represents Samuel Coleridge-Taylor at his very best.

The Romantic symbolism of the dying rose returns in Christina Rossetti’s poem Summer

One of the composer’s final works before his untimely death from pneumonia at the age of 37, the Song of Proserpine, serenades the ‘Sacred Goddess’, the daughter of Zeus in Classical mythology, in words by Percy Bysshe

Jonathan Clinch is Lecturer in Academic Studies at the Royal Academy of Music, London. He has worked extensively on the music of Herbert Howells, including a completion of the Cello Concerto (2014) and an edition of his piano works (2021).

© 2023 Jonathan Clinch1 Sea Drift

See where she stands, on the wet sea-sands, Looking across the water: Wild is the night, but wilder still The face of the fisher’s daughter !

What does she there, in the lightning’s glare, What does she there, I wonder?

What dread demon drags her forth In the night and wind and thunder?

Is it the ghost that haunts this coast? –

The cruel waves mount higher, And the beacon pierces the stormy dark With its javelin of fire.

Beyond the light of the beacon bright A merchantman is tacking; The hoarse wind whistling through the shrouds, And the brittle topmasts cracking.

The sea it moans over dead men’s bones, The sea it foams in anger;

The curlews swoop through the resonant air

With a warning cry of danger.

The star-fish clings to the sea-weed’s rings

In a vague, dumb sense of peril; And the spray, with its phantom-fingers, grasps At the mullein dry and sterile.

O, who is she that stands by the sea, In the lightning’s glare, undaunted? Seems this now like the coast of hell

By one white spirit haunted!

The night drags by; and the breakers die Along the ragged ledges; The robin stirs in its drenchèd nest, The hawthorn blooms on the hedges.

In shimmering lines, through the dripping pines, The stealthy mom advances; And the heavy sea-fog straggles back Before those bristling lances!

Still she stands on the wet sea-sands; The morning breaks above her, And the corpse of a sailor gleams on the rocks – What if it were her lover?

Thomas Bailey Aldrich (1836–1907) 2 By the Seashore By the lone seashoreMournfully beat the waves;

Mournfully evermore

The wild wind sobs and raves.

A sadness and a sense of deep unrest Brood on the clouds and on the waters’ breast. But lo! the white seamew careering, Float indolently by, float indolently by.

And lo! a snowy sail appearing Gleams fair against the sky, The sadness and the loneliness depart, And nature smiles with sympathy of heart.

Charles Mackay (1814–1889)3 Isle of Beauty

Shades of ev’ning, close not o’er us, Leave our lonely bark awhile!

Morn, alas! will not restore us

Yonder dim and distant Isle; Still my fancy can discover Sunny spots where friends may dwell; Darker shadows round us hover; Isle of Beauty, fare thee well!

When the waves are round me breaking, As I pace the deck alone, And my eye in vain is seeking Some green leaf to rest upon; What would not I give to wander

Where my old companions dwell?

Absence makes the heart grow fonder, Isle of Beauty, fare thee well!

Thomas Haynes Bayly (1797–1839)4 The Lee Shore

Sleet! and hail! and thunder!

And ye winds that rave, Till the sands there under Tinge the sullen wave –

Winds, that like a demon

Howl with horrid note

Round the toiling seaman, In his tossing boat –

From his humble dwelling

On the shingly shore, Where the billows swelling Keep such hollow roar –

From that weeping woman, Seeking with her cries

Succour superhuman

From the frowning skies –

From the urchin pining

For his father’s knee –

From the lattice shining, Drive him out to sea!

Let broad leagues dissever Him from yonder foam; –

O, God! to think man ever Comes too near his home!

Thomas Hood (1799–1845)5 Dead in the Sierras

His footprints have failed us, Where berries are red, And madroños are rankest, –The hunter is dead!

The grizzly may pass By his half-open door; May pass and repass

On his path, as of yore; The panther may crouch In the leaves on his limb; May scream and may scream, –It is nothing to him.

Prone, bearded, and breasted

Like columns of stone; And tall as a pine –

As a pine overthrown!

His camp-fires gone, What else can be done

Than let him sleep on Till the light of the sun?

Ay, tombless! what of it?

Marble is dust, Cold and repellent; And iron is rust.

Joaquin (Cincinnatus Heine) Miller (1837–1913)6 Song of Proserpine

Sacred Goddess, Mother Earth, Thou from whose immortal bosom Gods, and men, and beasts have birth, Leaf and blade, and bud and blossom, Breathe thine influence most divine On thine own child, Proserpine.

If with mists of evening dew Thou dost nourish these young flowers Till they grow, in scent and hue, Fairest children of the Hours, Breathe thine influence most divine On thine own child, Proserpine.

Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822)7 The Fair of Almachara

Hark to the cymbals singing!

Hark to their hollow gust!

The gong sonorous swinging

At each sharp pistol-shot!

Bells of sweet tone are ringing!

The Fair begins

With countless dins, And many a grave-faced plot!

Trumpets and tympans sound, ’Neath the moon’s brilliant round, Which doth entrance

Each passionate dance,

And glows or flashes

Midst jewelled sashes, Cap, turban, and tiara In a tossing sea Of ecstasy, At the Fair of Almachara!

There dance the Arab maidens, With burnished limbs all bare, Caught by the moon’s keen silver Through frantic jets of hair!

O naked moon! O wondrous face! Eternal sadness, beauty, grace, Smile on the passing human race!

Trumpets and tympans sound

’Neath the moon’s brilliant round, Which doth entrance

Each passionate dance, And glows or flashes

Midst jewelled sashes, Cap, turban, and tiara, In a tossing sea Of ecstasy, At the Fair of Almachara!

Richard

Hengist Horne (1802–1884)8 The Sea Shell

See what a lovely shell, Small and pure as a pearl,

Lying close to my foot, Frail, but a work divine, Made so fairily well With delicate spire and whorl, How exquisitely minute, A miracle of design! What is it? a learned man

Could give it a clumsy name. Let him name it who can, The beauty would be the same.

The tiny cell is forlorn, Void of the little living will

That made it stir on the shore. Did he stand at the diamond door

Of his house in a rainbow frill? Did he push, when he was uncurl’d, A golden foot or a fairy horn

Thro’ his dim water-world?

Slight, to be crush’d with a tap

Of my finger-nail on the sand, Small, but a work divine, Frail, but of force to withstand, Year upon year, the shock

Of cataract seas that snap

The three-decker’s oaken spine

Athwart the ledges of rock, Here on the Breton strand!

Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892), ‘The Shell’ from Maud

9 All my stars forsake me

And the dawn-winds shake me: Where shall I betake me?

Whither shall I run Till the set of the sun, Till the day be done?

To the mountain-mine, To the boughs o’ the pine, To the blind man’s eyne, To a brow that is Bowed upon the knees, Sick with memories.

10 The Evening Star

Star that bringest home the bee, And sett’st the weary labourer free!

If any star shed peace, ’tis Thou, That send’st it from above, Appearing when heaven’s breath and brow Are sweet as hers we love.

Come to the luxuriant skies, Whilst the landscape’s odours rise, Whilst far-off lowing herds are heard And songs, when toil is done, From cottages whose smoke unstirr’d Curls yellow in the sun.

Star of love’s soft interviews, Parted lovers on thee muse; Their remembrancer in Heav’n Of thrilling vows thou art, Too delicious to be riven By absence from the heart.

Thomas Campbell (1777–1844)11 Whispers of Summer

When whispers of summer are filling the air, It’s oh! to escape from the tumult of life, From its ceaseless worry, and its endless care, To flee from the sound, the sound of its strife, It’s Oh! just to be by the sweet summer sea, When the dancing waves sing low, And the heavens are bright And flushed with the light Of a sunset afterglow, It’s oh! for the peace that is waiting there, When whispers of summer are filling the air.

Kathleen Mary Easmon Simango (1891–1924)12 Summer is gone

Summer is gone with all its roses, Its sun and perfumes and sweet flowers, Its warm air and refreshing showers: And even Autumn closes.

Yea, Autumn’s chilly self is going, And winter comes which is yet colder, Each day the hoar-frost waxes bolder And the last buds cease blowing.

Christina Georgina Rossetti (1830–1894)13 Requiescat

Strew on her roses, roses, And never a spray of yew! In quiet she reposes; Ah, would that I did too! Her mirth the world required; She bathed it in smiles of glee. But her heart was tired, tired, And now they let her be.

Her life was turning, turning, In mazes of heat and sound. But for peace her soul was yearning, And now peace laps her round. Her cabin’d, ample spirit, It flutter’d and fail’d for breath. To-night it doth inherit The vasty hall of death.

Matthew Arnold (1822–1888)

The Choir of King’s College London is one of the leading university choirs in England, and has existed since its founding by William Henry Monk in the middle of the nineteenth century. The choir today consists of some thirty choral scholars reading a variety of subjects. The choir’s principal role at King’s is to provide music for chapel worship, with weekly Eucharist and Evensong offered during term, as well as various other services. Services from the chapel are regularly broadcast on BBC Radio. The choir also frequently sings for worship outside the university, including at Westminster Abbey and St Paul’s Cathedral. In addition, the choir gives many concert performances. Recent festival appearances in England include the Barnes Music Festival, English Music Festival, London Handel Festival, St Albans International Organ Festival, Thaxted Festival, and the Christmas and Easter Festivals at St John’s Smith Square. Recent collaborations include the UK premiere of Samuel Barber’s The Lovers (chamber version) with Britten Sinfonia at Kings Place, the performance

described in The Times as ‘sung beautifully, the voices judiciously blended’, Bach’s St John Passion with the Hanover Band, and Holst’s The Cloud Messenger with the English Chamber Orchestra. The choir tours widely, with recent destinations including Canada, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Italy, Nigeria and the USA.

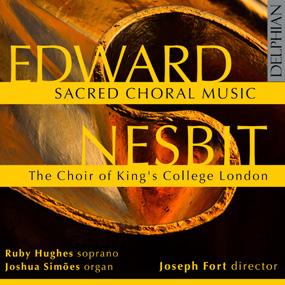

The choir has made many recordings, and enjoys an ongoing relationship with Delphian Records. Recent recordings include Lliam Paterson’s Say It to the Still World (a largescale commission for choir and electric guitar, DCD34246), Edward Nesbit’s Sacred Choral Music (DCD34256), which was a Gramophone

‘Editor’s Choice’ in 2022, a disc of Kerensa

Briggs’s choral works (DCD34298), and a major new recording of Rachmaninoff’s All-Night Vigil (DCD34296) to celebrate the composer’s 150th anniversary.

Following some twenty years under the leadership of David Trendell, the choir has been directed since 2015 by Joseph Fort.

Joseph Fort is a conductor and musicologist based in London. His performances with The Choir of King’s College London have been recognised as ‘English choral singing at its best’ (Choir & Organ), ‘a performance of astonishing intensity and musicality’ (Gramophone), and ‘superbly drilled’ (The Guardian). Orchestras with which he has worked recently include Britten Sinfonia, the English Chamber Orchestra and the Hanover Band. His growing discography with Delphian Records has received considerable critical acclaim. Festival conducting appearances across the world include the Festival de Mexico, the White Nights Festival of St Petersburg, the Montreal Organ Festival, the London Handel Festival, the St Albans International Organ Festival and the conventions of the American Guild of Organists and the Royal Canadian College of

Organists. At King’s, Joseph is responsible for chapel music, conducting the choir in the weekly Eucharist and Evensong services during term, as well as radio broadcasts, concerts and tours. He also serves as Director of Music at St Paul’s Knightsbridge, where he conducts the professional choir.

Joseph holds a PhD from Harvard University, and his academic research focuses on eighteenth-century music and dance. He is currently completing a monograph on Haydn and minuets. He has published in the Eighteenth-Century Music journal, and has chapters in books with Cambridge University Press and Leipzig University Press. Prior to Harvard, he studied at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he was the organ scholar, and at the Royal Academy of Music, who in 2017 elected him to their Associateship.

The Choir of King’s College London

Soprano

Ellie Blewitt

Isobel Coughlan Helen Hudson Choral Scholar

Julia Curry

Joni Foster

Sarah James Harrow Choral Scholar

Lucca Kelf

Anastasia Nunez

Lucy Peek

Julia Sherlock

Jennifer Spencer Helen Hudson Choral

Scholar

Katie Walker Eileen Lineham Choral Scholar

Alto

Ruby Bak Trendell Memorial Choral Scholar

Sheena Jibowu Harrow Choral Scholar

Katie Santi

Christine van der Wal

Klara Watson

Lorraine Wong

Tenor

William Collison

Ben Miller

Chris O’Leary

Harry Rowland

Julian Siemens

Christopher Trotter

Bass

Nicholas Bacon Gough Choral Scholar

Louis Edwards-Munro

Harry Fradley

Todd Harris

Thomas Hughes Glanfield Choral Scholar

Samuel Poole

Ricky Taing

Sergei Rachmaninoff: All-Night Vigil, Op. 37

The Choir of King’s College London / Joseph Fort

DCD34296

Could the definitive recording of the best-loved of all Orthodox choral works come from an Anglican chapel choir? Delphian’s Paul Baxter thinks so. The young King’s College London voices are bright, responsive and clear, and the recording is intentionally designed to bring out the bell-like phrases that ring through the whole piece. From the first second the sound grabs you and holds you close: it’s punchy, and bold – a new presentation of music we all thought we knew. In a recording to honour Rachmaninoff’s 150th anniversary, Joseph Fort and The Choir of King’s College London stake their claim to be among the finest choirs in the business.

‘Fort garners glowing consistency and soulfulness from his singers … Powerful music delivered with compelling self-belief’ — The Scotsman, February 2023

Deutsche Motette

Choir of Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge; The Choir of King’s College

London, Geoffrey Webber & David Trendell conductors

DCD34124

Delphian’s superchoir reunites after its highly successful recording of The Sealed Angel, this time for a unique programme of German music from Schubert to Richard Strauss. Strauss’s sumptuous Deutsche Motette is the last word in late Romantic choral opulence, its teeming polyphony brought to thrilling life by this virtuoso cast of over sixty singers. The rest of the programme explores the vivid colours and shadowy half-lights of a distinctly German music that reached its culmination in Strauss’s extravagant masterpiece. The singing throughout combines a musical intensity and imagination with an understanding of period style, two qualities that are hallmarks of both choirs’ work.

‘Credit to conductor David Trendell for eliciting that sustained intensity of expression from his combined college choirs, whose youthful timbre imparts a freshness which … suits the imprecatory nature of Rückert’s poem perfectly’ — BBC Music Magazine, August 2013

Kenneth Leighton / Frank Martin: Masses for Double Choir

The Choir of King’s College

DCD34211

London / Joseph Fort

In the 1920s Frank Martin, a Swiss Calvinist by upbringing, created a radiant Latin setting of the Mass for double choir, only to return it to the bottom drawer, considering it to be ‘a matter between God and myself’. It was finally released for performance forty years later, around the same time that the Edinburgh-based composer Kenneth Leighton made his own double-choir setting – a work with moments of striking stillness, delightful to choral singers and yet rarely recorded. Contrasts and comparisons abound at every point in this fascinating pairing of Masses from the supposedly godless twentieth century, and are brought out to the full by The Choir of King’s College London’s impassioned performances.

‘a performance of astonishing intensity and musicality’ — Gramophone, May 2019

Edward Nesbit: Sacred Choral Music

The Choir of King’s College London, Ruby Hughes soprano, Joshua Simoes organ, Joseph Fort director

DCD34256

As a young composer, Edward Nesbit was drawn to the rich complexities of contemporary instrumental music; little more than a decade later, he has found himself returning to the inheritance of his early youth as a chorister: the texts of mass, psalms and canticles, and the long centuries of the Anglican choral tradition. Not that there is anything traditional about Nesbit’s music, which synthesises these two heritages into a soundworld that is accessible, full of references yet always recognisably its own voice. Joseph Fort – his colleague at King’s College London – and organist Joshua Simoes and the King’s choir rise to the challenges expertly, while multi-awardwinning soprano Ruby Hughes gives the lead in the clarion textures of Nesbit’s Mass.

‘highly original and brilliantly crafted’ — Choir & Organ, February 2022, FIVE STARS

The Choir of King’s College London on Delphian

Holst: The Cloud Messenger

The Choir of King’s College London, The Strand Ensemble; Joseph Fort conductor

DCD34241

In 1910, after seven years of work, Gustav Holst completed his choral–orchestral masterpiece, The Cloud Messenger. But following a disappointing premiere in 1913 the piece fell into obscurity, and has received only a handful of performances. This crowning glory from the composer’s Sanskrit period deserves to be much better known. Telling the powerful fifth-century story of an exiled yaksha who spies a passing cloud and sends upon it a message of love to his distant wife in the Himalayas, it is rich in its harmonic language and ingenious in its motivic construction, and points the way to Holst’s next major work, The Planets. This colourful chamber version by conductor Joseph Fort lends the more tender passages a new intimacy and clarity, while retaining much of the force of the original.

‘[Fort’s arrangement shows] sensitivity, skill and an evident love for Holst’s visionary, rapturously romantic score ... The singing, too, has a lovely sweetness and purity of tone’ — Gramophone, July 2020

Kerensa Briggs: Requiem

The Choir of King’s College London, Anita Monserrat mezzo-soprano, Richard Gowers organ, Joseph Fort director

DCD34298

Now in her early thirties, Kerensa Briggs could hardly have enjoyed a more salubrious childhood for a composer of sacred choral music, surrounded by music in Gloucester Cathedral close, singing in choirs and hearing the daily choral services. Briggs went on to study music and sing as a choral scholar at King’s College London, and her music and her understanding of the way the voice works have their roots in this deep immersion. This recording is the first dedicated to her music, in a portrait programme of premieres. Joseph Fort and The Choir of King’s College London continue to attract widespread critical acclaim, both for the ambition of their recorded programmes and for their polished and mature execution.

New in May 2023

Lliam Paterson: Say it to the Still World

Sean Shibe electric guitar, The Choir of King’s College London, Joseph Fort director

DCD34246

Multi-award-winning Sean Shibe, widely recognised as the leading guitarist of his generation, joins Delphian regulars The Choir of King’s College London in these beguilingly conceived works by Shibe’s friend and compatriot Lliam Paterson, for the rare combination of choir with electric guitar. Say it to the still world casts Shibe as Orpheus with his lyre, in a work which draws fragments of text from poetry by Rilke to meditate on language, loss and the transcendent power of song. Elegy for Esmeralda is a rawer, angrier response to grief, while poppies spread – composed especially, like the other two works, for the performers who bring it to life here – is a further testament to art’s ability to reflect and transform the outer world.

‘Fort’s evocative choir and Shibe's moody though equally ecstatic electric guitar ... Gorgeous’ — The Scotsman, November 2021, FIVE STARS

Brahms: An English Requiem

Mary Bevan, Marcus Farnsworth, The Choir of King’s College London, James Baillieu & Richard Uttley piano, Joseph Fort director

DCD34195

Since its London premiere in 1871, Brahms’s German Requiem has enjoyed immense popularity in the UK, in both its orchestral and chamber versions. But the setting we know today is not the one that nineteenth-century British audiences knew and loved. The work was rarely performed here in German; rather, it was almost always sung in English translation, with the writer G.A. Macfarren proposing in a widely read text that it should be called An English Requiem. In its sixth Delphian recording, The Choir of King’s College London revives the nineteenth-century English setting in which Brahms’s masterpiece established itself as a favourite among its earliest British audiences. Under its new director Joseph Fort, the choir is joined by pianists James Baillieu and Richard Uttley, and soloists Mary Bevan and Marcus Farnsworth.

‘utterly uplifting’ — Norman Lebrecht, La Scena Musicale, November 2017