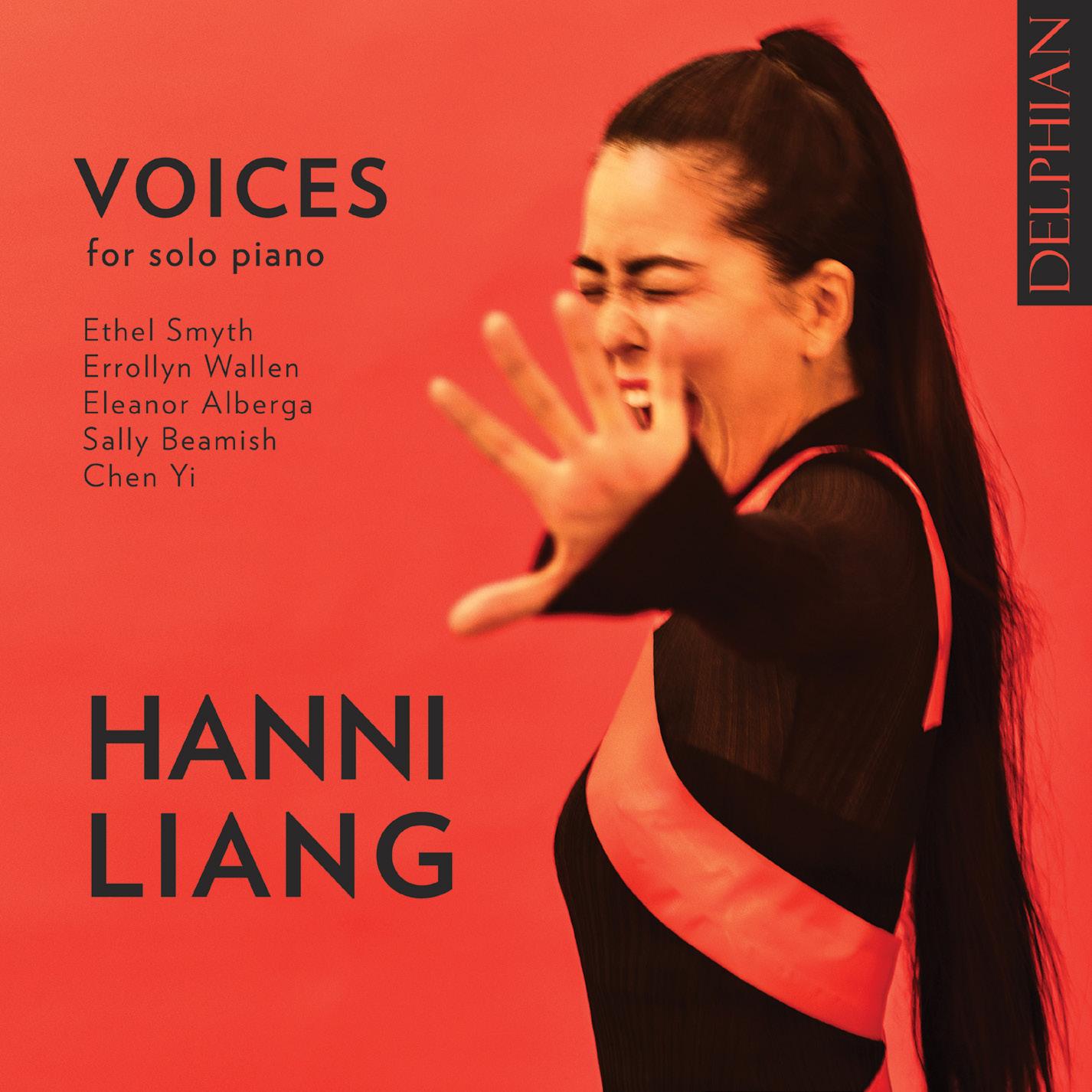

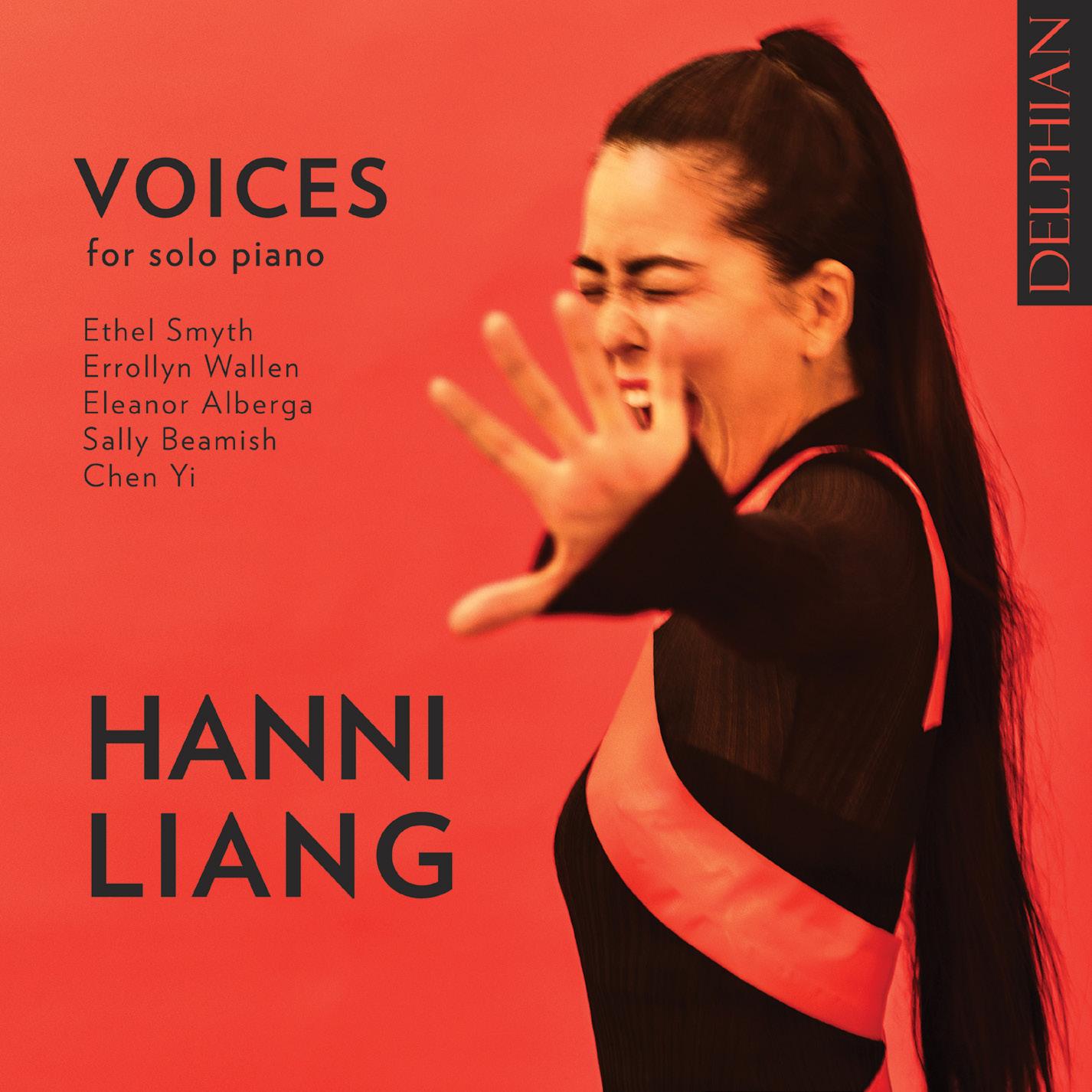

VOICES

for solo piano

Ethel Smyth

Errollyn Wallen

Eleanor Alberga

Sally Beamish

Chen Yi

HANNI LIANG

* premiere recordings

Recorded on 7-9 November 2023 in Sendesaal Bremen

Producer / Engineer: Andreas Neubronner

24-bit digital editing: Andreas Neubronner

24-bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter

Piano: Steinway model D, serial no. 597020 (2014)

Booklet editor: Henry Howard

Design: Eliot Garcia

Cover & portrait photography: Esther Haase

Session photography: Will Coates-Gibson/ Foxbrush

Delphian Records Ltd – Edinburgh – UK www.delphianrecords.com

Ethel Smyth (1858–1944) Sonata No. 2 in C sharp minor

I. Lento assai – Allegro assai – Allegro moderato

II. [Andante]

III. Finale: Presto con brio

Errollyn Wallen (b. 1958) I Wouldn’t Normally Say [2:20]

Ethel Smyth

delphianrecords

Variations in D flat major on an Original Theme (of an Exceeding Dismal Nature)

Thema (Rühig)

Variation I (Allegro)

Variation II (Quasi maestoso)

Variation III (Lento)

Variation IV (Allegro: à la Phyllis)

Variation V (Andante con moto)

Variation VI (Adagio)

Variation VII (Presto: wild und stürmisch)

Variation VIII & Finale (Allegro con brio)

Sally Beamish (b. 1956) Night Dances * [12:54]

Chen Yi (b. 1953)

Variations on ‘Awariguli’

Theme (Andante)

Variation I (Allegro)

Variation II (Allegro)

Variation III (Con moto vivace)

Variation IV (Sostenuto)

Variation V (Alla romance)

Variation VI (Moderato)

Variation VII (Alla danza)

Variation VIII (Allegro moderato)

Variation IX (Andante)

Coda (Vivace)

Eleanor Alberga (b. 1949) Cwicseolfor * [11:44]

When I gave my debut 2018 in the Elbphilharmonie Hamburg together with the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, it was a dream come true for a traditionally trained classical pianist. But as always, when you reach the peak of a mountain, next comes the long way down, and that is what happened to me. I started to question: Why am I doing this? Why am I a musician? What is a concert? What remains when the music is over? And what does being an artist mean when facing all the challenges we have in the world?

In my search for the answer, which is going, I'm sure, to be lifelong, I’ve found my beliefs for now:

I believe that art poses questions, that it challenges us to confront different perspectives, that it can unite us in diversity and be a gallery of the present moment –the ‘now’. That’s why I’m making music and where I want to make my contribution as a human being.

This album started with my inner need to raise my voice, to reflect my Chinese roots as one who was born and grew up in Europe. All this is mirrored in the programme I have chosen which would not have been possible without the constant support of my wonderful family: my parents, partner and my two lovely children.

Also a big thank you to Joachim and Anna Kühmstedt as well as to Esther Haase for creating such a strong photo for the album. And of course to sound engineer Andreas Neubronner, the whole Delphian team, my wonderful PR agency WildKat, and Sendesaal Bremen.

— Hanni Liang

‘It was just a book – you know how it sometimes happens,’ says Hanni Liang. She is describing reading a volume about the British composer, writer and suffragette Dame Ethel Smyth, an episode in that constant process of exploration that musicians embark upon to find new ideas and new repertoire. ‘And I was so inspired and so impressed by her. Not only by her music, but also as a person and as a woman. Fighting without any compromises for her beliefs. She was a symbol and also an inspiration for me to really raise my voice. Indeed, raising one’s voice today, when we are facing so many challenges –social, economic, ecological – that’s why the album title is Voices.’

It’s entirely characteristic of Liang that the path to Voices has been so strongly shaped by cultural and political ideas as well as musical ones. She is endlessly thoughtful about what a musical performance might be, and how audience and performers could (or should) interact in a concert space. To that end, she is sceptical about what many would see as the traditional role of recording in developing an artist’s career, questioning the need to record and re-record standard repertoire. ‘The last recording of Smyth’s piano music was in the 1990s,’ she explains. ‘It was the first time I had a feeling that there was a need

to record this music again, to make her music come alive.’ And her desire to connect Smyth’s musical and political thinking to the present day then sent her off in pursuit of contemporary works to complement these late-nineteenth-century pieces, two of which are premiere recordings.

The British-Jamaican composer Eleanor Alberga composed Cwicseolfor in 2021 for Isata Kanneh-Mason, and its title is the ancient spelling of quicksilver, or mercury. ‘As a child,’ Alberga writes,

I remember being fascinated with watching mercury in a container; how it didn’t adhere to anything and moved and changed direction rapidly. There was also an almost unbelievable brilliance on the surface of this stuff. Anyone who has seen this will know exactly what I mean. (Little wonder that in so many cultures and over many centuries mercury has been seen as having transformative qualities.)

It is precisely this sense of transformation – of change that often seems to turn on a dime – that drives Cwicseolfor. Broad, resonant chords are replaced by scuttling single notes in each hand, which melt into short duets. Major and minor chords leap out from a tonal palette which embraces everything from Beethoven and Debussy to John Adams and beyond, and the pace and tempo of the music is constantly changing. This is musical

alchemy at is most vivid, as Alberga herself describes it, and it is as entrancing as it is ferociously virtuosic. Liang admits that this was final piece to be recorded, on the basis that it was the most extreme workout not only for her, but also for the piano!

Chen Yi’s beautiful Variations on ‘Awariguli’ were composed in 1978 and premiered by her sister, Chen Min, in Beijing. The theme is an Uyghur folksong (the Uyghurs are a persecuted minority from the Xinjiang region of north-west China), which Chen discovered in a collection of Chinese folksongs whilst studying for her undergraduate degree. It is simply stated at the work’s opening, almost unharmonised, before we set out on a series of nine variations. The shape of the song of course informs the chords and colours of what follows, drifting now and again towards what we might hear as Impressionist harmonies, whilst Chen’s distribution of the melody and accompanying figurations between hands seems to invoke a number of different pianist-composers from across the last few hundred years (not to mention a Bachian fugue in the sixth variation, although it is in more than one time signature). A grand coda returns us to our theme, broken by strident fanfare-like chords; but the very ending is quiet, left hanging in the air, as if there is no such thing as a fixed ending to this song.

Liang was determined to include a Chinese composer as part of her programme. Although she was born and raised in Germany, she feels deeply connected to her Chinese family roots. Indeed, you could say that the pairing of Chen Yi and Ethel Smyth both reveal something of Liang’s personal heritage: on the one hand Chinese culture, and on the other, two works written during Smyth’s years of study in Liang’s home country of Germany and profoundly influenced by Austro-German models. Smyth was nineteen years old when she finally persuaded her parents that she should be allowed to attend Leipzig Conservatory to study as a composer and pianist, falling almost immediately among acclaimed performers and composers. In England she had been particularly taken by the music of Johannes Brahms, and by 1879 was personally acquainted with both Brahms and Clara Schumann, among others. Her three piano sonatas (the third of which was left incomplete) were all composed in her first year in Germany, as assignments set by her tutors at the Conservatory. But the Sonata No. 2 in C sharp minor, included here, has an autobiographical element that Smyth herself described unapologetically in her memoirs.

During her weekends in Leipzig, Smyth would attend the theatre as a means of improving her German and getting to know the theatrical literature. Among the regular lead actors in these performances was Marie Geistinger, a woman some twenty years Smyth’s senior who was also a major operetta star (in fact, she had performed in the premiere of Johann Strauss II’s Die Fledermaus just three years earlier). Smyth cheerfully admitted that she fell frequently and deeply in love with women throughout her life – her ‘passions’, as she called them – and rapidly became ‘quite mad about Geistinger’. After weeks of waiting for her at the stage door, and taking her cards and flowers, she was eventually granted an audience. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it rapidly transpired that the two women had little to say to each other; but such was the significance of this encounter to Smyth that she

came home, felt another creature, and forthwith composed I think the best thing I have yet done – the skeleton of a ‘first movement’ of a new sonata. It is really programme music, though no one would know it! I have the whole scene there – going up the stairs, the ‘Herzklopfen’ [throbbing heart] at the door, and all!

Smyth’s feelings on encountering Geistinger are realised in an idiom at once Beethovenian and Brahmsian, with a strong sense of rhythmic urgency and energy that is also characteristic of her later works. Indeed, what’s remarkable about the Sonata as a whole is that it feels simultaneously like a composer firmly finding her feet in a traditional form, and a young musician joyfully throwing her own unique ideas at the manuscript paper. The slow movement is particularly unusual, floating between keys in a way that turns the principal melody into something almost completely singable and yet oddly out of reach, wandering away in a new direction just when its path seems clear.

Smyth’s Variations in D flat major on an Original Theme (of an Exceeding Dismal Nature), composed the following year, were written during her summer visit to England to see her parents. She was gently reprimanded by her German friends whilst away, who detected that her considerable energy was being spread across multiple pursuits –reading, playing, composing, socialising, hunting and sport – in a way that they thought would endanger her creative focus. No doubt they were amused to discover that one of the variations in Smyth’s new piece (the fourth, ‘à la Phyllis’) was ‘inspired by, and named after, the filly I had broken’. The theme, of her own composition, hints at Robert

Schumann as well as Brahms, and is rather intriguingly written in two time signatures at the same time – 3/4 and 6/8 – which means that the overall sense of pulse can be gently tweaked from bar to bar for rhetorical effect. Despite Smyth’s wry description of this set as having ‘an Exceeding Dismal Nature’, it is far from hyperbolically funereal, the variations sometimes gently rocking, sometimes grandly majestic. We hear Smyth’s new horse, Phyllis, in the fourth variation, stamping and cantering with admirable control. There are later moments of touching introspection as well as bravura showmanship, and a sweetly lyrical restatement of the theme to end the piece.

It is significant that Smyth wrote later about the revelation of hearing these Variations performed by a highly skilled pianist, since although she was herself a trained keyboard player, her technique and approach to the instrument was unconventional. ‘Her pieces are really uncomfortable to play,’ Liang observes, ‘as if she didn’t want to make it too easy for the performer.’ It is a challenge, as an interpreter, to recognise the very familiar idioms from which Smyth was learning, whilst also following her own independent lines of musical thought that often cut across expectations. But that difficulty, Liang believes, is very important. ‘She fought her whole life to be heard, and in the end

she didn’t succeed. It shouldn’t be easy –because it wasn’t easy. It’s really about that – the struggle, the fight, to keep on and not give up.’

After the dynamism and defiance of Smyth’s early works, Sally Beamish’s Night Dances offers a different kind of restlessness –and indeed sleeplessness – that is rather more introspective. Beamish developed a narrative for the work with the playwright Peter Thomson, wanting to find a way of writing night music that wasn’t simply tied to familiar ideas of the nocturne or depictions of sunset. Instead, the opening pages take us from a mind attempting to sleep into a gradually unfurling sense of anxiety and unrest, vividly conjured by the gradual increase in different pitches in the score and the repeated pounding of a single note. Animation and hesitation follow in alternating sections, chords jerky and unsettled, as our unnamed protagonist rises and goes out into the night-time world. They eventually begin dancing: wild, exuberant striding gestures are thrown across the keyboard, the right hand twirling and spinning as if in free improvisation (Beamish cites both John McLaughlin and Keith Jarrett as important influences in this work). Eventually the energy flags, the pace slows, and we return home to those opening, circling notes. In the

final few bars, the frame once again narrows to the crystalline, hypnotic repetitions of just a tiny handful of notes. Sleep, it seems, is descending at last.

Errollyn Wallen’s I Wouldn’t Normally Say was composed in 2004 for inclusion in a new anthology, Salsa Nueva, compiled by the Venezuelan-born pianist Elena Riu. The piece is dedicated to Wallen’s sister Karen: the two played piano duets frequently as children, and this was a chance to remember and celebrate those days. The tempo marking is, wonderfully, ‘From the hip’, the music dancing and swinging across different time signatures and unexpected changes of gear, always with a knowing, joyful smile.

Is this all-female line-up a pointed political statement? ‘No and yes,’ says Liang. ‘No, since we should really be over the idea of women who compose by now. And yes,

because it’s a shout-out to all of us, not only to women: I deeply believe that we can in the end shape and foster humanity through art and through culture and music.’ Ethel Smyth is where the project began, as a symbol of raising one’s voice to make a difference, and the cover of this album makes it clear that this, too, is Hanni Liang’s rallying cry: ‘Let’s be really active, and shape our world together.’

© 2024 Katy Hamilton

Katy Hamilton is a writer, presenter and broadcaster specialising in nineteenth-century music. She works regularly with concert halls and festivals across the UK and Europe, and is a frequent contributor to BBC Radio 3.

Hanni Liang is a pianist and concert creator, in which she is a lecturer at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater München (University of Music and Performing Arts Munich). Believing that art and culture can foster our humanity, she specialises in developing new concert formats and in her projects uses her art to address contemporary topics.

Performances have brought her to such places as Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, where she asked the question ‘Who owns the water?’ in her performance of the Piano Concerto by Caroline Shaw. She has also performed in venues including the Royal Concert Hall Nottingham, Konzerthaus Berlin, Mariinsky Theatre, Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich, Haus Styriarte Graz (Austria), Kurhaus Wiesbaden and State Opera Hanover and at festivals including Heidelberger Frühling, Ludwigsburger Schlossfestspiele, Reeperbahn Festival, Kissinger Sommer and Mozartfest Würzburg, in which she opens up the classical concert to become a space of encounters and exchanges through co-creativity, developing concerts together with people from all different kinds of backgrounds.

Schumann | Brahms

Elena Fischer-Dieskau

DCD34255

Clara Wieck, who in 1840 was to become Clara Schumann, was a significant figure in the lives both of her husband Robert and of Johannes Brahms, to whom the Schumanns became mentors. The double inspirations of Clara and of the writer E.T.A. Hoffmann’s fictional Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler are the connecting threads on this debut recording by pianist Elena Fischer-Dieskau, in which Robert’s capricious, moody Kreisleriana is joined by two sets of piano pieces by Brahms.

‘With a name like Fischer-Dieskau, this young pianist has a lot to live up to. But the granddaughter of the famous baritone need not worry, for she holds her own, and then some, in this engaging programme’ — BBC Music Magazine, November 2021

Sola: music for viola by women composers

Rosalind Ventris

DCD34292

In this largely British and Irish programme of music for unaccompanied viola, Rosalind Ventris sets substantial works by important yet still often overlooked twentieth-century composers –Imogen Holst, Lillian Fuchs, Elizabeth Maconchy, Elisabeth Lutyens and Grażyna Bacewicz – alongside more recent additions to the repertoire from Thea Musgrave, Sally Beamish and Amanda Feery. With several of the composers themselves professional string players, this is, in Ventris’s words, ‘wonderful music – that just happens to be by women composers’.

‘Gorgeously full-bodied playing, weighty yet poised’ — The Guardian, February 2023

Oxana Shevchenko: winner of the 2010 Scottish International Piano Competition

DCD34061

On 19 September 2010, a rapt audience in Glasgow’s City Halls witnessed the 23-year-old Kazakhstani pianist emerge decisively on the international stage. She had already won the International Music Critics’ Prize at the 2009 Ferruccio Busoni International Piano Competition, and now carried away first prize with unanimous approval from a distinguished international jury. Including works by Shostakovich, Mozart, Liszt and Ravel, this recital, recorded just three days after her triumph in the concerto final, reveals her extraordinary command of structure, rhythmic dynamism and sheer pianistic exuberance.

‘a shrewdly chosen and enjoyably varied programme with playing at an exalted level … it is a rare gift to convey on disc also the sheer joy of performing’ — Gramophone, April 2011, EDITOR’S CHOICE

Valentin Silvestrov: Piano Sonatas

Simon Smith

DCD34151

This survey of piano music by the Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov is the first to focus on the 1970s, an important period in the formation of Silvestrov’s later style. Nothing is quite as it seems in the ostensibly Mozartian Classical Sonata, while its three numbered successors provide further glimpses into Silvestrov’s unique relationship with memory and the past. The short Nostalghia represents the mature Silvestrov, with its yearning melodic fragments and complex emotional undertow.

‘Smith has already recorded a brilliant Schnittke set for this label, and he’s equally persuasive here … sensational recorded sound, too, with the Steinway’s rich bass notes beautifully caught’ — The Arts Desk, January 2016

Editor's choice

Beyond Twilight: music for cello & piano by female composers

Alexandra Mackenzie, Ingrid Sawers

DCD34306

Furthering their longstanding interest in unfamiliar repertoire, cellist

Alexandra Mackenzie and pianist Ingrid Sawers have unearthed for this album a treasure trove of short pieces by female composers, some hiding behind bland initials such as ‘A. E. Horrocks’. Dating

from the 1880s to the 1950s, these intimate, quietly powerful works include miniatures by the Scottish cellist Marie Dare and two delightful songs by Gwendolen (later Avril) Coleridge-Taylor, here newly transcribed for cello. A total of fourteen works are presented, all but five in premiere recordings.

‘Mackenzie plays with appropriate panache’ — BBC Music Magazine, Christmas edition 2023

I and Silence: women’s voices in American song

Lieberson / Argento / Barber / Copland / Crumb

Marta Fontanals-Simmons mezzo-soprano, Lana Bode piano

DCD34229

The expectations of silence often placed on women historically and politically, and music’s power to break through them, are the themes of this deeply personal recital. Channelling the voices of female writers and musicians, Fontanals-Simmons and Bode include two works – Dominick Argento’s From the Diary of Virginia Woolf and Peter Lieberson’s Rilke Songs – which were written for great mezzo-sopranos of the recent past, Dame Janet Baker and Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, while settings of Emily Dickinson and Sara Teasdale fill out a programme which meditates powerfully on loss, vulnerability, tenacity and mindfulness.

‘[Fontanals-Simmons] prefers the words and music to do the talking, and they do so eloquently’ — BBC Music Magazine, October 2019

Kenneth Leighton: Complete Solo Piano Works

Angela Brownridge

DCD34301 (3 CDs)

Leighton’s complete solo piano music is presented for the first time, on three discs containing many world premiere recordings. Written for the composer’s own instrument, and played here by his distinguished pupil Angela Brownridge, these works span Leighton’s entire compositional career.

‘Brownridge plays superbly throughout – at all times, she is fully up to the technical, intellectual and characterizing demands of this music, and the recording quality of her instrument is consistently excellent … very strongly recommended’ — International Record Review, June 2005

Stone, Salt & Sky: Beamish – Maconchy – Strachan – Clarke

GAIA Duo

DCD34263

Formed in 2019, award-winning violin and cello duo GAIA have rapidly won plaudits for their pioneering programming and bold and daring performances. Their debut album release features three works specially written for the duo, and also bears testimony to their championing of works by underrepresented and overlooked voices from classical music’s past. Elements of folk and jazz string-playing styles rub shoulders with traditional chamber-music imperatives in a programme that is full of women’s voices: those of the performers; of composers Sally Beamish, Rebecca Clarke and Elizabeth Maconchy; and of the singers of two Scottish folksongs, taped recordings of which frame Duncan Strachan’s hauntingly evocative Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.

‘fiery confidence … Only a few tracks in and you’re transfixed’ — The Scotsman, April 2023, FIVE STARS