WALTON WILLIAM

COMPLETE SONG COLLECTION

Siân Dicker soprano

Krystal Tunnicliffe piano

Saki Kato guitar

Siân Dicker soprano

Krystal Tunnicliffe piano

Saki Kato guitar

Siân Dicker soprano

Krystal Tunnicliffe piano

Saki Kato guitar**

The artists gratefully acknowledge the generous assistance of Ruth Whitehead Associates/Dissenters, the Golsoncott Foundation, William Newsom, Theresa Cole, Christine Melville, Dr Susan Partridge, Francesca Chiejina, Richard Hammond-Hall, Mimi Doulton, Nanette Tunnicliffe, Dr Morag Shiach, Sylvia Chew, Bharti Karadia, Rachel Liddell, Dr Clare Taylor and Dr Robert McAdie They also recognise with huge appreciation the artistic support of City Music Foundation, the Royal Over-Seas League, Marie Vassiliou, Christopher Glynn, Andrew West, Sholto Kynoch and David Wordsworth.

Recorded on 5-7 January 2024 in St Mary’s Parish Church, Haddington

Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter

24-bit digital editing: Jack Davis

24-bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter

Piano: Steinway model D, 2016, serial no. 600443

Piano technician: Norman Motion

Design: John Christ

Booklet editor: Henry Howard

Cover image: Firefly/Coates-Gibson

Session photography: foxbrush.co.uk

Delphian Records Ltd – Edinburgh – UK www.delphianrecords.com @ delphianrecords @ delphianrecords @ delphian_records

A Song for the Lord Mayor’s Table 1 1. The Lord Mayor’s Table [3:32] 2 2. Glide gently [2:30]

3 3. Wapping Old Stairs [2:34] 4 4. Holy Thursday [3:55] 5 5. The Contrast [3:09] 6 6. Rhyme [2:12] Anon in Love ** 7 1. Fain would I change that note [3:19] 8 2. O stay, sweet love [1:47] 9 3. Lady, when I behold the roses [1:45] 10 4. My Love in her attire [0:53] 11 5. I gave her Cakes and I gave her Ale [1:37]

Under the greenwood tree [2:06]

Beatriz’s Song (from Christopher Columbus ) arr. Christopher Palmer [3:05] Three ‘Façade’ Settings

Daphne [3:07]

Old Sir Faulk [2:02]

Through gilded trellises [4:07] Total playing time [53:42] * premiere recordings

The Winds [1:44]

It is not too fanciful to suggest that if young Master William Turner Walton had not been naturally blessed with a beautiful singing voice, we would not have had the great composer Sir William Walton that he became. In later years, Walton was fond of telling whoever would listen that his voice trial at Christ Church Cathedral School, Oxford almost didn’t happen, because his father had been to the pub the night before and spent the funds that been saved for the train journey from Oldham to Oxford. His mother duly borrowed some money from the local greengrocer and escorted her son to his trial – they arrived after the auditions were over, but Mrs Walton pleaded with the panel and William was accepted. Dr Thomas Strong, then Dean of Christ Church, saw potential, took the boy under his wing, and Walton stayed at the school for six years, until he became an undergraduate at Christ Church at the age of 16. Walton admitted in later life that he had started to compose when his voice broke to make himself seem interesting and so he wouldn’t get sent back to Oldham. Sir Hubert Parry, who had seen some of the young composers’ early efforts, was clearly impressed, telling Dr Strong, ‘There’s a lot in this chap, you must keep your eye on him’.

Despite starting his musical life as a singer, music for solo voice played a small part in Walton’s output until relatively late in his life,

the two song cycles not appearing until the early 1960s. During the most successful period of his career in the 1920s and 30s, Walton was preoccupied with the large-scale works that made his reputation, such as the Viola and Violin Concertos, the oratorio Belshazzar’s Feast and the First Symphony. The war years brought ballets, incidental music for the radio and theatre, and most importantly music for films such as The First of the Few and Laurence Olivier’s Shakespeare films. It was only after the composition of a String Quartet, his grand opera Troilus and Cressida, the Cello Concerto and the Second Symphony that he turned his attention to the solo voice again.

Nevertheless, amongst Walton’s earliest surviving works are Four Early Songs, composed between 1918 and 1920. The autographs of three of the songs only turned up at an auction some years after Walton’s death and so they were not published as a set until 2022, to celebrate the centenary of the composer’s birth; this recording is the first of the complete set. Swinburne was not an obvious poet to choose, it is more likely that these texts were suggested to him by Dr Strong – Walton was not, even in later life, an avid reader of poetry, and indeed he had the texts for his later songs selected for him. Three of the songs are competent, especially for a sixteen-year-old, whilst not

being startlingly original, but ‘The Winds’, with its pulsating, stormy piano part and dramatic conclusion, shows us something rather different – and this song was the first of Walton’s works to be published in 1921.

Tritons, setting an obscure seventeenthcentury ‘madrigal’ by William Drummond and written in 1921, is the most interesting of these early vocal works, with a surprisingly angular vocal line and a much more elaborate piano accompaniment. Walton never really mastered the piano, or indeed any other instrument, and his piano parts are never particularly straightforward, but this song shows the musical distance he had travelled in a few short years, and that the hours he had sat in the library at Oxford studying scores of works by Stravinsky, Debussy and others was time well spent.

There can be no doubt that Walton’s first meeting with the Sitwell family, Osbert in the first instance, saved him financially, after he had been ‘sent down’ from Oxford for failing the obligatory exams in Greek and Algebra. Walton himself was aware of his good fortune, declaring that if it wasn’t for the Sitwells he would have ended up working in a bank. The circumstances surrounding the first (private) performance of Façade in 1922, the ‘entertainment’ Walton wrote with Edith Sitwell, have been well documented, and

even a little elaborated by the participants; however, it can’t be denied that Façade made Walton’s name The music is quite astonishingly sophisticated, and it is hard to believe that its composer was barely nineteen years old when he started to write the music for Dame Edith’s bizarre experimental poems. The ensuing history of Façade is far too complicated to relate here – Walton spent most of his life revising, ditching and adding movements, creating a ballet and orchestral suites out of the music, and even composing a Façade 2, seemingly not being able to stop tinkering with his precocious original.

In Façade the text is of course spoken, so the melodic lines and the accompaniment of the Three ‘Façade’ Settings are all derived from the music played by the six instrumentalists in the original, which again results in a rather challenging piano part. ‘Daphne’ does not bare much resemblance to the setting of the same poem that now is an ‘additional number’ the final published version of Façade – Walton always felt that the ‘spoken version’ of this poem had not worked and was much happier with this song. ‘Through gilded trellises’ and ‘Old Sir Faulk’ are more closely related to the original – the first having an appropriately exotic Spanish atmosphere (the poem is full of references to the heat, castanets, and siestas), while the second is a Foxtrot, which like so much

of Façade is full of references to popular music of the time. The songs are dedicated to Dora and Hubert Foss, who gave the first performances. Some years before, Hubert Foss had founded the music department of Oxford University Press, which became Walton’s publisher for the rest of his life.

Both Under the greenwood tree and Beatriz’s Song are the result of incidental music Walton wrote for a film and a radio play respectively. The Shakespeare setting was written for – though never performed by – the Austrian-British actress Elisabeth Bergner, who appeared in Paul Czinner’s 1936 film of As You Like It. These circumstances, together with an effort to match the period of the play, account for the simplicity of the vocal line, reflecting an Elizabethan lute-song.

‘Beatriz’s Song’ was part of the music Walton wrote for Christopher Columbus , a radio play by his friend Louis MacNeice, broadcast in 1942. The song was only published by a reluctant Walton (who believed that his incidental music had no real function out of its original context) in 1974, in a voice and piano arrangement made by Christopher Palmer.

The relationship between two of the greatest British composers of the twentieth century, William Walton and Benjamin Britten, has been the cause of a good deal of speculation. Britten was undoubtedly prickly and, on many

occasions, suspicious of his colleagues. Walton, on the other hand, was jealous of the younger composer’s success, a success that had to some extent, together with negative critical reaction to the music he had written after the war that suggested he was old-fashioned and ‘written out’, affected his already considerable insecurities and made composition increasingly difficult.

However, Britten did graciously support Walton with performances and commissions – his chamber opera The Bear was premiered at the Aldeburgh Festival in 1967 and his last major orchestral work, Improvisations on an Impromptu of Benjamin Britten (1967) was a direct act of homage, so despite Walton’s bluster and sometimes rather ungallant comments about Britten and his music, there was clearly some regard and affection between them.

Anon in Love was another Aldeburgh commission, this time for the 1960 Aldeburgh Festival where it was first performed by Peter Pears and Julian Bream. Christopher Hassall (who had the curious distinction of collaborating with both Ivor Novello and William Walton – he was the librettist for Troilus and Cressida ) chose the texts, taking care to include some Restoration poems that would have appealed to Walton’s schoolboy sense of humour.

Pears had created the role of Pandarus in Troilus and Cressida and the vocal writing of the mischievous ‘fixer’ in the opera clearly parodies certain mannerisms in Britten’s vocal style, no doubt written with a twinkle in the eye. These are to some extent carried on into Anon in Love. Having said that, the sly syncopations in the faster movements and languid vocal lines of the slower songs could not be by any other composer.

Walton had not written for the guitar before and so Julian Bream sent the composer a sheet of instructions entitled ‘Sir William’s Dot Chart for the Box’ (Bream always referred to his instrument as ‘the box’).

Writing idiomatically for the guitar is no easy matter, but Walton evidently got his head around the complexities and went on some years later to compose Bream a set of ‘Five Bagatelles’ for solo guitar that have become much admired repertoire pieces.

A Song for the Lord Mayor’s Table was commissioned by the Worshipful Company of Musicians for the 1962 City of London Festival. The first performance was given by Elisabeth Schwarzkopf (who had been the composer’s first choice for the part of Cressida but had withdrawn due to scheduling problems – there was also a suggestion that singing such a huge role in English was making her very nervous), and the then doyen of piano accompanists

Gerald Moore. The famously somewhat frosty Madame Schwarzkopf demanded that she have must have the score at least ten weeks before the premiere; Walton, never particularly good with deadlines, apparently delivered on time, though there were several alterations made before the premiere which both performers seem to have readily accepted.

The six texts, again chosen by Christopher Hassall, are primarily a celebration of the City of London – the church bells, the Wapping Old Stairs (site of a famous pub by the river where the dead bodies of pirates used to hang), St Paul’s Cathedral, and a declaration that the joys to be found in the city are so much more interesting than the rather boring countryside! Brief moments of serenity are provided by setting of Wordsworth’s evocation of the Thames, ‘Glide gently’, and even more seriously by William Blake’s ‘Holy Thursday’. At the head of the score of this last collection of songs, Walton placed the words ‘In Honour of the City of London’ – itself the title of an earlier, rarely performed Walton choral work that sets a text by William Dunbar. Walton later made orchestral accompaniments of these two cycles, but in many ways, it is in their original, more intimate versions that the wit and sparkle of both pieces come through to best effect.

In his old age there were several approaches made to Walton about the possibility of new songs and cycles but sadly, as with the Third Symphony (for André Previn), a choral and orchestral setting of the Stabat Mater (for Owain Arwel Hughes and Huddersfield Choral Society), and rather tantalisingly, a companion piece for The Bear with a libretto by Alan Bennett, no less, these came to nothing. One can only agree with Gerald

Moore who wrote to Walton’s publisher about A Song for the Lord Mayor’s Table – ‘these Walton songs are really terrific –everything WW does is impressive – why the devil doesn’t he write more songs …?’

© 2024 David Wordsworth

David Wordsworth is a choral conductor and writer. He is shortly to begin work on a new biography of Sir William Walton.

1 1. The Lord Mayor’s Table

Let all the Nine Muses lay by their abuses, Their railing and drolling on tricks of the Strand, To pen us a ditty in praise of the City, Their treasure, and pleasure, their pow’r and command.

Their feast, and guest, so temptingly drest, Their kitchens all kingdoms replenish; In bountiful bowls they do succour their souls, With claret, Canary and Rhenish:

Their lives and wives in plenitude thrives, They want not for meat nor money; The Promised Land’s in a Londoner’s hand, They wallow in milk and honey.

Let all the Nine Muses …

Thomas Jordan (c.1612–1685)

2 2. Glide gently

Glide gently, thus for ever, ever glide, O Thames! that other bards may see As lovely visions by thy side

As now, fair river! come to me.

O glide, fair stream, for ever so, Thy quiet soul on all bestowing, Till all our minds for ever flow

As thy deep waters now are flowing.

William Wordworth (1770–1850), from ‘Remembrance of Collins’

3.

Your Molly has never been false, she declares, Since last time we parted at Wapping Old Stairs, When I swore that I still would continue the same, And gave you the ’bacco box, marked with your name.

When I pass’d a whole fortnight between decks with you, Did I e’er give a kiss, Tom, to one of the crew?

To be useful and kind, with my Thomas I stay’d, For his trousers I wash’d, and his grog too I made.

Though you threaten’d, last Sunday, to walk in the Mall

With Susan from Deptford, and likewise with Sal, In silence I stood your unkindness to hear, And only upbraided my Tom with a tear.

Why should Sal, or should Susan, than me be more priz’d?

For the heart that is true, Tom, should ne’er be despis’d; Then be constant and kind, nor your Molly forsake, Still your trousers I’ll wash, and your grog too I’ll make.

4 4. Holy Thursday

’Twas on a holy Thursday, their innocent faces clean, The children walking two and two, in red, and blue, and green: Gray-headed beadles walked before, with wands as white as snow, Till into the high dome of St Paul’s they like Thames waters flow.

O what a multitude they seemed, these flowers of London town!

Seated in companies they sit, with radiance all their own. The hum of multitudes was there, but multitudes of lambs, Thousands of little boys and girls raising their innocent hands.

Now like a mighty wind they raise to heaven the voice of song, Or like harmonious thunderings the seats of heaven among; Beneath them sit the aged men, wise guardians of the poor: Then cherish, cherish pity, lest you drive an angel from your door.

William Blake (1757–1827)

5 5. The Contrast

In London I never know what I’d be at, Enraptured with this, and enchanted by that, I’m wild with the sweets of variety’s plan, And life seems a blessing too happy for man.

But the country, Lord help me! sets all matters right, So calm and composing from morning to night; Oh! it settles the spirit when nothing is seen But an ass on a common, a goose on a green.

Your magpies and stock-doves may flirt among trees, And chatter their transports in groves, if they please: But a house is much more to my taste than a tree, And for groves, o! a good grove of chimneys for me.

In the country, if Cupid should find a man out, The poor tortured victim mopes hopeless about, But in London, thank Heaven! our peace is secure, Where for one eye to kill, there’s a thousand to cure.

I know love’s a devil, too subtle to spy, That shoots through the soul, from the beam of an eye;

But in London these devils so quick fly about, That a new devil still drives an old devil out.

Charles Morris (1745–1838)

6 6. Rhyme

Gay go up and gay go down, To ring the bells of London Town.

Oranges and lemons

Say the bells of St Clement’s.

Bull’s eyes and targets, Say the bells of St Margaret’s. Brickbats and tiles, Say the bells of St Giles’. Half-pence and farthings, Say the bells of St Martin’s. Pancakes and fritters, Say the bells of St Peter’s. Two sticks and an apple, Say the bells of Whitechapel.

Pokers and tongs, Say the bells of St John’s. Kettles and pans, Say the bells of St Ann’s. Old father baldpate, Say the slow bells of Aldgate. You owe me ten shillings, Say the bells of St Helen’s. When will you pay me?

Say the bells of Old Bailey. When I grow rich, Say the bells of Shoreditch. Pray when will that be?

Say the bells of Stepney.

I do not know, Says the great bell of Bow.

Gay go up and gay go down, To ring the bells of London Town. Anon.

Anon in Love

7 1. Fain would I change that note

Fain would I change that note To which fond Love hath charm’d me Long, long to sing by rote, Fancying that that harm’d me: Yet when this thought doth come ‘Love is the perfect sum

Of all delight!’

I have no other choice

Either for pen or voice

To sing or write.

O Love! they wrong thee much That say thy fruit is bitter, When thy rich fruit is such As nothing can be sweeter. Fair house of joy and bliss, Where truest pleasure is, I do adore thee:

I know thee what thou art, I serve thee with my heart, And fall before thee.

8 2. O stay, sweet love

O stay, sweet love; see here the place of sporting; These gentle flowers smile sweetly to invite us, And chirping birds are hitherward resorting, Warbling sweet notes only to delight us: Then stay, dear love, for, tho’ thou run from me, Run ne’er so fast, yet I will follow thee.

I thought, my love, that I should overtake you; Sweet heart, sit down under this shadow’d tree, And I, I will promise never, never, to forsake you, So you will grant to me a lover’s fee. Whereat she smiled, and kindly to me said: ‘I never meant to live and die a maid.’

9 3. Lady, when I behold the roses

Lady, when I behold the roses sprouting, Which clad in damask mantles deck the arbours, And then behold your lips where sweet love harbours, My eyes present me with a double doubting; For, viewing both alike, hardly my mind supposes Whether the roses be your lips or your lips the roses.

10 4. My Love in her attire

My Love in her attire doth show her wit, It doth so well become her: For every season she hath dressings fit, For winter, spring, and summer. No beauty she doth miss When all her robes are on: But Beauty’s self she is When all her robes are gone.

11 5. I gave her Cakes and I gave her Ale

I gave her Cakes and I gave her Ale, I gave her Sack and Sherry; I kist her once and I kist her twice, And we were wondrous merry. I gave her Beads and Bracelets fine, I gave her Gold down derry.

I thought she was afear’d till she stroaked my Beard And we were wondrous merry. Merry my Hearts, merry my Cocks, Merry my Sprights, my hey down derry. I kist her once and I kist her twice, And we were wondrous merry.

12 6. To couple is a custom

To couple is a custom: All things thereto agree. Why should not I then love, Since love to all is free?

But I’ll have one that’s pretty, Her cheeks of scarlet dye, For to breed my delight When that I lig her by.

Tho’ virtue be a dowry, Yet I’ll chuse money store: If my love prove untrue, With that I can get more. The fair is oft unconstant, The black is often proud, I’ll chuse a lovely brown: Come fiddler scrape thy crowd. For Peggy the brown is she; She must be my bride; God guide that Peggy and I agree.

Anon.

Four Early Songs

13 1. Child’s Song

What is gold worth, say, Worth for work or play, Worth to keep or pay, Hide or throw away, Hope about or fear? What is love worth, pray? Worth a tear?

Golden on the mould

Lie the dead leaves rolled Of the wet woods old, Yellow leaves and cold, Woods without a dove; Gold is worth but gold; Love’s worth love.

14 2. Song

Love laid his sleepless head

On a thorny rosy bed; And his eyes with tears were red, And pale his lips as the dead.

And fear and sorrow and scorn Kept watch by his head forlorn, Till the night was overworn And the day was merry with morn.

And Joy came up with the day And kissed Love’s lips as he lay, And the watchers ghostly and grey Sped from his pillow away.

And his eyes as the dawn grew bright, And his lips waxed ruddy as light: Sorrow may reign for a night, But day shall bring back delight.

Fair of face, full of pride, Sit ye down by a dead man’s side.

Ye sang songs a’ the day: Sit down at night in the red worm’s way.

Proud ye were a’ day long: Ye’ll be but lean at evensong.

Ye had gowd kells on your hair: Nae man kens what ye were.

Ye set scorn by the silken stuff: Now the grave is clean enough.

Ye set scorn by the rubis ring: Now the worm is a saft sweet thing.

Fine gold and blithe fair face, Ye are come to a grimly place.

Gold hair and glad grey een, Nae man kens if ye have been.

16 4. The Winds

O weary fa’ the east wind, And weary fa’ the west: And gin I were under the wan waves wide I wot weel wad I rest.

O weary fa’ the north wind, And weary fa’ the south: The sea went ower my good lord’s head Or ever he kissed my mouth.

Weary fa’ the windward rocks, And weary fa’ the lee: They might hae sunken sevenscore ships, And let my love’s gang free.

And weary fa’ ye, mariners a’, And weary fa’ the sea: It might hae taken an hundred men, And let my ae love be.

Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837–1909)

17 Tritons

Tritons, which bounding dive Through Neptune’s liquid plain, Whenas ye shall arrive With tilting tides where silver Ora plays, And to your king his wat’ry tribute pays, Tell how I dying live, And burn in midst of all the coldest main.

William Drummond of Hawthornden (1585–1649)

18 Under the greenwood tree

Under the greenwood tree

Who loves to lie with me, And turn his merry note

Unto the sweet bird’s throat, Come hither, come hither, come hither: Here shall he see

No enemy

But winter and rough weather.

Who doth ambition shun And loves to live i’ the sun, Seeking the food he eats, And pleased with what he gets, Come hither …

William Shakespeare (1564–1616), As You Like It, Act II, scene v

19 Beatriz’s Song

When will he return? Only to depart.

Harrowed by the omen

Of his restless heart; Bondsman of the voice, Rival to the Sun, Viceroy of the sunset Till his task be done.

Though he is my love He is not for me;

What he loves lies over Loveless miles of sea. Haunted by the West, Eating out his heart When will he return? Only to depart.

Louis MacNeice

20 Daphne

When green as a river was the barley, Green as a river the rye, I waded deep and began to parley With a youth whom I heard sigh. ‘I seek’, said he, ‘a lovely lady, A nymph as bright as a queen, Like a tree that drips with pearls her shady Locks of hair were seen. And all the rivers became her flocks Though their wool you cannot shear, Because of the love of her flowing locks … The kingly sun like a swain Came strong, unheeding of her scorn, Bathing in deeps where she has lain, Sleeping upon her river lawn And chasing her starry satyr train. She fled, and changed into a tree, That lovely fair-haired lady … And now I seek through the sere summer Where no trees are shady.’

21 Old Sir Faulk

Old Sir Faulk

Tall as a stork,

Before the honeyed fruits of dawn were ripe, would walk And stalk with a gun

The reynard-coloured sun

Among the pheasant-feathered corn the unicorn has torn, forlorn the Smock-faced sheep

Sit and sleep

Periwigged as William and Mary, weep:

‘Sally, Mary, Mattie, what’s the matter, why cry?’

The huntsman and the reynardcoloured sun and I sigh,

‘Oh, the nursery-maid Meg

With a leg like a peg

Chased the feathered dreams like hens, and when they laid an egg

In the sheepskin Meadows

Where

The serene King James would steer Horse and hounds, then he

From the shade of a tree

Picked it up as spoil to boil for nursery tea’ said the mourners.

In the Corn, towers strain

Feathered tall as a crane

And whistling down the feathered rain, old Noah goes again –

An old dull mome

With a head like a pome, Seeing the world as a bare egg

Laid by the feathered air; Meg Would beg three of these

For the nursery teas

Of Japhet, Shem and Ham; she gave it

Underneath the trees

Where the boiling Water

Hissed

Like the goose-king’s feathered daughter – kissed

Pot and pan and copper kettle

Put upon their proper mettle

Lest the Flood, the Flood, the Flood begin again through these!

22 Through gilded trellises

Through gilded trellises

Of the heat, Dolores, Inez, Manucia, Isabel, Lucia, Mock Time that flies.

‘Lovely bird, will you stay and sing, Flirting your sheened wing, Peck with your beak, and cling To our balconies?’

They flirt their fans, flaunting

‘O silence enchanting As music!’ Then slanting Their eyes,

Like gilded or emerald grapes, They make mantillas, capes, Hiding their simian shapes.

Sighs

Each lady, ‘Our spadille’s Done.’ ‘Dance the quadrille from Hell’s towers to Seville;

Surprise

Their siesta,’ Dolores

Said. Through gilded trellises

Of the heat, spangles

Pelt down through the tangles Of bell flowers; each dangles Her castanets, shutters

Fall while the heat mutters, With sounds like a mandoline Or tinkled tambourine ...

Ladies, Time dies!

Texts from Facade by Dame Edith Sitwell (1887–1964).

Words reprinted from Edith Sitwell’s Façade and other Poems 1920–1935 , by permission of the publishers Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd. Licensed by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

‘Oozing characterful expression’ (Opera Today ), soprano Siân Dicker is in demand for her rich, full-bodied voice and dramatic flair. Siân is a City Music Foundation Artist and was listed in BBC Music Magazine ’s ‘Rising Stars’ feature in February 2023. She won the Singers Prize in the 2020 Royal Over-Seas League Competition and has since performed as a young artist for Britten–Pears Arts, Ryedale Festival and Oxford International Song Festival. Recent operatic engagements include roles and covers for English National Opera, Royal Opera House, Opera Holland Park, Garsington Opera, Bampton Classical Opera and Waterperry Opera. Siân was delighted to be awarded the Simon Sandbach Award by Garsington Opera for her contribution to their 2023 season.

Siân enjoys regular song recitals with duo partner, Krystal Tunnicliffe, across Europe and the UK. Recent performances include recitals at the International Lied Festival Zeist, Life Victoria Barcelona, Aldeburgh Festival, Ryedale Festival, Oxford International Song Festival, St Martin-in-the-Fields, Ludlow English Song Weekend and BBC Radio 3’s In Tune

Siân studied at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama with Marie Vassiliou and Janice Chapman. She is a Live Music Now musician and works as a workshop leader with the Britten–Pears Arts Community team.

British/Australian pianist Krystal Tunnicliffe is ‘an exceptionally gifted and sympathetic player, whose light, flowing touch will endear itself to a host of the next best singers’ (Patrick Maxwell, Classical Music Daily ).

She enjoys a varied career as a collaborative pianist and music educator, and has been a Samling Artist, Britten–Pears Young Artist, Ryedale Festival Young Artist, and an Oxford Song Young Artist. With duo partner Siân Dicker, she has performed at the LIFE Victoria Festival (Barcelona), International Lied Festival Zeist, Aldeburgh Festival, Ryedale Festival, Oxford Song Festival, and on BBC Radio 3’s In Tune. Other recent highlights include performances with Brindley Sherratt and Nicky Spence as part of the Ludlow English Song Weekend and Ryedale Festival respectively, as well as recitals at Wigmore Hall, Queen Elizabeth Hall, St-Martin-inthe-Fields, and LSO St Luke’s. She is a staff pianist in the Junior department of the Guildhall School of Music and Drama.

Krystal is a graduate of the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music, and the Franz-Schubert-Institut (Baden bei Wien). She studied with Glenn Riddle, Andrew West and Christopher Glynn.

Saki Kato is a Japanese classical guitarist who specialises in the areas of new music performance and community music-making. In 2019 she gave her debut recital at the Wigmore Hall for the Julian Bream Trust, which included the world premiere of Edward Cowie’s Stream and Variations. As a Julian Bream Trust scholar, Saki studied privately with Julian Bream from 2017 to 2020. As a soloist and member of the Miyabi Duo, Saki regularly collaborates with composers including Sylvia Lim and Electra Perivolaris, whose pieces they premiered at the Wigmore Hall. They have recorded music by Edward Cowie and Mihailo Trandafilovski, which was released in 2022 by Métier.

Saki’s extensive community music-making work includes leading musical workshops for participants of all ages. In 2020 she was awarded fellowships at Wigmore Hall Learning and Open Academy (RAM) to develop these skills. She works regularly with Britten–Pears Arts, Sinfonia Viva, English National Ballet and Wigmore Hall Learning. Saki graduated from the Royal Academy of Music in 2020, having been awarded the Dove Award, the John McAslan Prize, the Timothy Gilson Guitar Prize and the LRAM diploma.

From a city window: songs by Hubert Parry

Ailish Tynan, Susan Bickley, William Dazeley; Iain Burnside piano

DCD34117

Recorded in the music room of Hubert Parry’s boyhood home, Highnam Court in Gloucestershire, this disc sees three of our finest singers shed illuminating light on an area of the repertoire that has rarely graced the concert hall in recent times. Iain Burnside and his singers rediscover what has been forgotten by historical accident – and what a treasure chest of song they have found! These beautiful performances return Parry’s songs to the heart of his output, where the composer always felt they belonged.

‘The emotional range of these songs, almost faultlessly conceived in terms of textual rhythm, reminds us of just how expert a song-writer and pioneer of the English art Parry was ... The performances are exquisite’ — Gramophone, April 2013

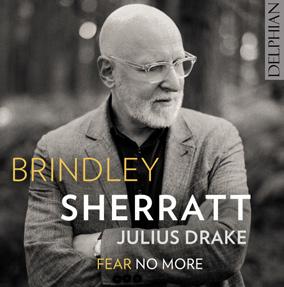

Brindley Sherratt: Fear No More

Brindley Sherratt bass, Julius Drake piano

DCD34313

Brindley Sherratt’s pre-eminence as an operatic bass is the result of two daring career shifts. Initially trained as a trumpeter, he gave up his first instrument as a student to become a singer. Yet even then, it was only in his mid-thirties that he left the professional security of a position in the BBC Singers to explore the world of opera. Now, the voyage of discovery continues as Sherratt turns to the intimate medium of the song recital. With the superb pianist Julius Drake as collaborator, in Fear No More Sherratt draws on all of his accumulated technical and expressive wisdom to traverse death-haunted songs by Schubert, Mussorgsky and Richard Strauss before arriving at a final group of five twentieth-century English songs in which consolation and acceptance are the keynotes.

‘Sherratt’s interpretations have an imposing power all their own, the deep, oaky patina of the voice carrying with it a special emotional weight’— Gramophone, May 2024

Our Indifferent Century: Britten – Finzi – Marsey – Ward

Francesca Chiejina, Fleur Barron; Natalie Burch piano DCD34311

In 1914 Thomas Hardy wrote of ‘our indifferent century’; a generation later W.H. Auden urgently sought to fuse the political with the creative. Today, profoundly unsettled by the turn of the world’s politics, three artists respond with a programme that explores the changes and challenges we face presently, but one that also offers hope, levity an even a degree of irreverence, and never loses sight of the joy and beauty of nature. Hardy and Auden found their perfect musical counterparts in the songwriting of Finzi and Britten; in our own times William Marsey and Joanna Ward add their own musical voices of political urgency and wistful yearning.

‘thought-provoking, beautifully executed and timely’

— BBC Music Magazine, December 2023

‘A fine showcase for the Glaswegian-born composer’ — BBC Radio 3 Record Review, July 2021

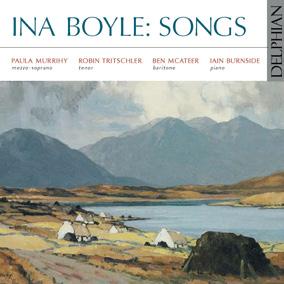

Ina Boyle: Songs

Paula Murrihy, Robin Tritschler, Ben McAteer; Iain Burnside piano DCD34264

In lifelong seclusion in rural County Wicklow, Ina Boyle created a legacy of song – tender, often melancholy, illuminated by an exquisite sense for harmony. ‘I think it is most courageous of you to go on with such little recognition,’ wrote Vaughan Williams to his pupil. ‘The only thing to say is that it does come finally.’

Amid the 2020 pandemic, Iain Burnside gathered three superb Irish singers at London’s Wigmore Hall. Recorded in less than five hours, the resulting 80 minutes of music unveil a composer who is one of Ireland’s ‘invisible heroines’. Half a century after Boyle’s death, is Vaughan Williams’s prediction at last coming true?

‘Ina Boyle could scarcely have wished for better advocacy than her songs receive here’ — MusicWeb International, September 2021