BENJAMIN BRITTEN: CANTICLES

JAMES WAY tenor NATALIE BURCH piano

LOTTE BETTS-DEAN mezzo -soprano

HUGH CUTTING countertenor

ROSS RAMGOBIN baritone

ANNEMARIE FEDERLE horn ALIS HUWS harp

1 Benjamin Britten (1913–1976) Canticle I: My beloved is mine and I am his [8:04]

2 Benjamin Britten Canticle II: Abraham and Isaac [17:59]

3 Benjamin Britten Canticle III: Still falls the Rain [12:06]

4 Benjamin Britten Canticle IV: Journey of the Magi [11:59]

5 Benjamin Britten Canticle V: The Death of Saint Narcissus [8:10]

Priaulx Rainier (1903–1986) Cycle for Declamation

6 I: Wee cannot bid the fruits [2:10]

7 II: In the wombe of the earth [2:23]

8 III. Nunc, lento sonitu [4:53]

Total playing time [67:50]

The artists thank Lindsay Tomlinson, Sir Simon Robey and The Nicholas Boas Charitable Trust for their generous support of this recording

Recorded on 15-17 January 2024 in St Mary’s

Parish Church, Haddington

Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter

24-bit digital editing: Jack Davis

24-bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter

Piano: Steinway & Sons model D,

serial no. 600443 (2016)

Piano technician: Norman Motion Design: Drew Padrutt

Booklet editor: Henry Howard

Cover image: Cookworthy Knapp, David Shaw Fine Art Photography

Session photography: Will Coates-Gibson/Foxbrush Delphian Records Ltd – Edinburgh – UK www.delphianrecords.com Made and printed in the EU

www.delphianrecords.com @ delphianrecords @ delphianrecords @ delphian_records

In 2022, the pianist Natalie Burch and her husband James Way gave a concert at the Aldeburgh Festival called ‘Songs after Supper’. The performance took the form of an imagined evening at the Red House, home of Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears, in which friends and colleagues (including Imogen Holst and Bernard van Dieren) shared their music. Among the programmed works were Britten’s Canticle II as well as two numbers from a Cycle for Declamation by the South African-born composer Priaulx Rainier. From this happy collaboration the idea of a recording project emerged, bringing together a new generation of Britten singers with the Royal Harpist Alis Huws and the brilliant young horn player Annemarie Federle. Indeed, friendships, romantic partnerships and professional collaborations abound among both the performers and composers – above all in the spirit of Peter Pears, the first interpreter of all pieces featured. ‘It underpins the whole disc,’ James explains, ‘doing music that was written between and for a couple … there’s a different relationship in performing and playing when you live together, share your daily lives together, have arguments together. And it’s a real privilege to perform music specifically written for that kind of partnership.’

Britten’s Canticle I holds a special place for Natalie and James, and has been in their duo repertoire for many years. It was the first piece the composer wrote after he and

Pears moved to Crag House in the centre of Aldeburgh in 1947. The work sets words by the seventeenth-century poet Francis Quarles who in turn draws upon the Song of Solomon. This lyrical love song – ostensibly to God but, given the masculine pronouns in play and the work’s intended performers, also from Britten to Pears – is heavily influenced by the music of Henry Purcell, a favourite of both men. The Canticle combines dreamily bitonal lyricism with a pinging Purcellian setting of ‘Nor time, nor place’, and the hymn-like declaration that ‘He is my altar; I, his holy place’. It is a work of multiple moods and stylistic influences, ingeniously combined to capture the many sides of love.

Britten’s first-floor study at Crag House overlooked the shingle beach and beating waves of the North Sea. He was completely delighted with his new home: indeed, the resounding success several years earlier of his opera Peter Grimes – which is set in Aldeburgh – makes plain his deep connection with the landscape, evoked so beautifully (and sometimes brutally) in this and other works. For Natalie, that sense of place is crucial. ‘When I play Britten, I try to think of Aldeburgh and the sea – there’s something stark, grey, but with a great sense of depth.’ It is this idea of ‘recreating the landscape’ as she plays that allows her a way into the music without feeling as if she is obliged to copy Britten’s own distinctive playing style.

Canticle II raises the question of voice types. It was composed for inclusion in a fundraising concert for the English Opera Group, which Britten, Pears and a clutch of colleagues had established after the Second World War. In January 1952, Pears was joined in the premiere by the celebrated British contralto Kathleen Ferrier. The ‘Songs after Supper’ programme of 2022 had seen James and Natalie perform this piece with mezzosoprano Lotte Betts-Dean. ‘We thought our voices combined really well,’ says James, ‘and I was keen to record it this way rather than with a countertenor’ (which is often done, but has a very different aural impact).

This Canticle is a dramatic scene: a conversation between father, son and God. Britten deftly transforms two individual voices into a single, unearthly unit to represent God’s voice, an extraordinary pairing of pure ringing major chords in the piano with chant-like simplicity of harmony between the singers and occasional, gently crunching seconds. Abraham leads his son, who follows obediently, his vocal line copying his father’s – though Abraham’s turmoil is made clear to us in a heartfelt recitative to God. And yet Isaac remains obedient, even his fear at learning of his own demise leading him back to singing the same note as Abraham, a musical ‘agreement’. The jangling killing blow is stopped by the return of God’s voice, and father and son deliver a lilting song of praise.

Canticle III is a profoundly moving expression of mourning and loss. The Australian pianist and composer Noel Mewton-Wood had become a close friend of Britten and Pears, and deputised as Pears’s accompanist whilst Britten was at work on his opera Gloriana Mewton-Wood’s lover William Fedrick died unexpectedly of a ruptured appendix in late 1953 and the anguished musician blamed himself for not spotting Fedrick’s symptoms sooner. He killed himself a few days later by drinking hydrogen cyanide. Imogen Holst recorded that on receiving this news, Britten looked ‘grey and worried, and talked of the terrifyingly small gap between madness and non-madness, and said why was it that the people one really liked found life so difficult.’

Britten turned to the writings of the British modernist Edith Sitwell, whose poetry Façade had been so memorably set by William Walton in the 1920s. He chose something quite different: ‘The Raids, 1940. Night and Dawn,’ a remarkably vivid, heartsore reflection on the losses of the Second World War which is shot through with biblical imagery of the Old and New Testaments. This time the tenor is joined by a horn – although ‘joined’ is not entirely accurate, as singer and instrumentalist alternate for the vast majority of the piece, the horn providing an introduction and interludes between the increasingly expansive, recitative-like statements of the tenor. Only in the final few lines of the poem do the two come together to ‘speak’, magically, as one.

Canticle III was, Natalie reflects, the most difficult to grapple with. ‘We spent a lot of time working out how to get into the piece. The connections between the horn and vocal sections are some of the hardest moments in the whole set of Canticles: to get that pacing right, to pick up from one another.’ It was Sitwell’s poetry, ultimately, that provided the answer – the performers all ‘leaning on the text’, as she describes it – to find the right way through the whole.

It was in the year before the composition of Canticle III that Britten and Pears first met Priaulx Rainier, when her Sonata for Viola and Piano was performed at the Aldeburgh Festival (with Mewton-Wood at the keyboard). Rainier had settled in the UK in her late teens, and by the 1940s was developing an impressive reputation as a composer. Her music was premiered by Yehudi Menuhin, Jacqueline du Pré and Janet Craxton; Michael Tippett was a close friend; and she joined the St Ives group of artists in Cornwall in 1953 where she had a composing hut in Barbara Hepworth’s garden. Pears commissioned her that same year to write the Cycle for Declamation, an unaccompanied setting of three extracts from John Donne’s Devotions upon Emergent Occasions of 1624.

encounter unaccompanied secular vocal solos). In the strident first movement the singer hammers out his opening lines on a single high note; whilst the second is long-breathed and fluid, the voice ebbing and flowing in pitch and volume. The third alternates English and Latin phrases, the repeated Latin phrases lending a reflective, ritualistic feel to the whole. This final piece sets some of Donne’s most famous lines: ‘No man is an Iland, entire of itself … Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankinde … And therefore never send to know for whom the Bell tolls; It tolls for thee.’

The contours of the Cycle for Declamation are clearly moulded to the shape of Pears’s voice – just as he was also Britten’s vocal ideal. I wonder how difficult it is to escape this heavy performative legacy: how a twenty-first-century tenor might develop his own sense of musical ownership. ‘You have to challenge yourself to dissociate yourself from his sound,’ says James. ‘You have to do what your body does – I’m built completely differently from Pears – and consider what you can do best.’ He points to the detailed instructions in the scores of both composers, and the need to find space beyond what’s on the page to make the performance truly personal.

also toured internationally with Pears. Canticle IV was premiered in June 1971, and broadcast on British television in December of the same year. Yet despite the profound subject matter of T.S. Eliot’s poem, this is far from a po-faced narrative. ‘We thought of it as being three older men reflecting on their journey, all sat around a coffee table – or in a pub – squabbling a bit as they speak,’ says Natalie. She mentions the way in which Britten picks up on this in-built humour, staggering the men’s entries, and James laughs in agreement. ‘The baritone’s always furiously late to the party and has something ludicrous to say … so everyone else just moves on.’

Canticle IV was dedicated to the original performers of the piece: countertenor James Bowman, baritone John Shirley-Quirk and, of course, Pears. The awkward piano opening offers a delightfully witty depiction of lolloping camels, and as the three men sing together to tell us their story they pause and repeat words as if trying to remember what happened next.

Rainier’s writing is not straightforwardly virtuosic, but it is a fearsome performative challenge (and it’s rare, as James notes, to

There is a gap of almost twenty years between Britten’s Canticle III and Canticle IV, during which time he was largely occupied with largescale projects (A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the War Requiem, to name but two) and

The angular musical lines once the singers split into three parts – not to mention the sharp, scurrying piano writing – brilliantly captures the biting cold and uncomfortable journey. The musical sections and sudden mood changes match Eliot’s verse divisions, and as they repeat that the place they found ‘was (you may say) satisfactory’, the piano quotes from the plainchant ‘Magi videntes stellam’ associated with the first Vespers for

the Feast of the Epiphany. This also returns at the close of the work as part of a chord both major and minor, joyful and sorrowful. Composed in 1974 to another Eliot text, Canticle V is the most gnomic and mysterious of the five. The second-century Saint Narcissus, an early Bishop of Jerusalem, has little in common with the poet’s central character. Instead, Eliot seems to have created a curious hybrid of the Greek mythological Narcissus (famously obsessed with his own reflection) and the Christian martyr Saint Sebastian, who is usually depicted with multiple arrow wounds. (‘I haven’t got the remotest idea what it’s about,’ Britten wrote cheerfully to one of his friends.) What matters above all is Eliot’s language: the dreams he unfurls, the ideal beauty of the Greek youth Narcissus, and the innocence lost by the story’s end. The tenor is accompanied this time by a harp, a wonderful example of making a virtue out of necessity, since Britten’s health was sufficiently poor by this time that he could not have performed as Pears’s accompanist. The fluid shapes of the harp’s opening figurations hint at the watery mirror that was Narcissus’s downfall; but Britten’s use of the instrument is endlessly inventive, from strumming chords and snippy high phrases to the twanging resonance of ringing bass notes. What is the ultimate intention of bringing the music of Britten and Rainier together in this

© 2025 Katy Hamilton

way? ‘The Declamations are brilliant pieces,’ Natalie replies simply. ‘And they’re so fresh,’ James chips in, ‘they sound very new, very unusual. They’d suit so many different voices.’ Most importantly, Natalie clarifies, ‘they work so well together: the Rainier is so arresting, so confrontational at the start before becoming more intimate; and the Canticles are big, dramatic pieces that draw an audience in.’ The music of each composer provides new ways of listening to, and thinking about, the other. And of course, there is also the question of raising Rainier’s profile and inspiring others to tackle her music. ‘If just two or three other people listen and think “oh that’s interesting, I want to learn these,” then that’s got to be a win.’

Katy Hamilton is a music historian, presenter and broadcaster . She works regularly with concert halls and festivals across the UK and Europe, and is a frequent contributor to BBC Radio 3.

Texts

1 Canticle I: My beloved is mine and I am his

Ev’n like two little bank-divided brooks, That wash the pebbles with their wanton streams, And having ranged and searched a thousand nooks,

Meet both at length at silver -breasted Thames, Where in a greater current they conjoin: So I my best-beloved’s am; so he is mine.

Ev’n so we met; and after long pursuit, Ev’n so we joined; we both became entire; No need for either to renew a suit, For I was flax and he was flames of fire: Our firm-united souls did more than twine; So I my best-beloved’s am; so he is mine.

I’m his by penitence, he mine by grace; I’m his by purchase, he is mine, by blood; He’s my supporting elm and I his vine; Thus I my best beloved’s am; thus he is mine.

He gives me wealth; I give him all my vows: I give him songs, he gives me length of days; With wreaths of grace he crowns my longing brows,

And I his temples with a crown of praise, Which he accepts: an everlasting sign, That I my best-beloved’s am; that he is mine.

Francis Quarles (1592–1644)

2 Canticle II: Abraham and Isaac

God speaketh:

If all those glittering monarchs that command

The servile quarters of this earthly ball, Should tender in exchange their shares of land, I would not change my fortunes for them all: Their wealth is but a counter to my coin: The world’s but theirs; but my beloved’s mine.

Nor time, nor place, nor chance, nor death can bow

My least desires unto the least remove; He’s firmly mine by oath, I his by vow; He’s mine by faith, and I am his by love; He’s mine by water, I am his by wine, Thus I my best-beloved’s am; thus he is mine.

He is my altar; I, his holy place; I am his guest and he, my living food;

Abraham, my servant, Abraham, Take Isaac, thy son by name, That thou lovest the best of all, And in sacrifice offer him to me Upon that hill there besides thee.

Abraham, I will that so it be, For aught that may befall.

Abraham riseth and saith:

My Lord, to Thee is mine intent Ever to be obedient.

That son that Thou to me hast sent Offer I will to Thee. Thy bidding done shall be.

Here Abraham, turning him to his son Isaac, saith: Make thee ready, my dear darling, For we must do a little thing. This woodë do on thy back it bring, We may no longer abide. A sword and fire that I will take, For sacrifice behoves me to make; God’s bidding will I not forsake, But ever obedient be.

Here Isaac speaketh to his father, and taketh a bundle of sticks and beareth after his father. Father, I am all ready

To do your bidding most meekëly, And to bear this wood full bayn am I, As you commanded me.

bayn: willing

Here they both go to the place to do sacrifice. Now, Isaac son, go we our way To yonder mount if that we may.

My dear father, I will essay To follow you full fain.

Abraham being minded to slay his son Isaac, lifts up his hands, and saith the following:

O! My heart will break in three, To hear thy words I have pitye; As Thou wilt, Lord, so must it be, To Thee I will be bayn. Lay down thy faggot, my own son dear.

All ready father, lo, it is here. But why make you such heavy cheer? Are you anything adread?

Ah! Dear God! That me is woe!

Father, if it be your will, Where is the beast that we shall kill?

Thereof, son, is none upon this hill.

Father, I am full sore affeared To see you bear that drawne sword.

Isaac, son, peace, I pray thee, thou breakest my heart even in three.

I pray you, father, layn nothing from me, But tell me what you think.

layn: hide

Ah! Isaac, Isaac, I must thee kill!

Alas! Father, is that your will, Your owne child for to spill Upon this hillës brink? If I have trespassed in any degree With a yard you may beat me; Put up your sword, if your will be, For I am but a child. Would God my mother were here with me! She would kneel down upon her knee, Praying you, father, if it may be, For to save my life.

O Isaac, son, to thee I say God hath commanded me today Sacrifice, this is no nay, To make of thy bodye.

Is it God’s will I shall be slain?

Yea, son, it is not for to layn.

Here Isaac asketh his father’s blessing on his knees, and saith:

Father, seeing you mustë needs do so, Let it pass lightly and over go; Kneeling on my kneës two, Your blessing on me spread.

My blessing, dear son, give I thee And thy mother’s with heart free. The blessing of the Trinity, My dear Son, on thee light.

Here Isaac riseth and cometh to his father, and he taketh him, and bindeth and layeth him upon the altar to sacrifice him, and saith: Come hither, my child, thou art so sweet, Thou must be bound both hands and feet.

Father, greet well my brethren ying, And pray my mother of her blessing, I come no more under her wing, Farewell for ever and aye.

Farewell, my sweete son of grace!

Here Abraham doth kiss his son Isaac, and binds a kerchief about his head.

I pray you, father, turn down my face, For I am sore adread.

Lord, full loth were I him to kill!

Ah, mercy, father, why tarry you so?

Jesu! On me have pity, That I have most in mind.

Now, father, I see that I shall die: Almighty God in majesty! My soul I offer unto Thee!

To do this deed I am sorryë.

Father, do with me as you will, I must obey, and that is skill, Godës commandment to fulfil, For needs so it must be.

Isaac, Isaac, blessed must thou be.

Here let Abraham make a sign as though he would cut off his son Isaac’s head with his sword; then God speaketh:

Abraham, my servant dear, Abraham, Lay not thy sword in no manner On Isaac, thy dear darling. For thou dreadest me, well wot I, That of thy son has no mercy, To fulfil my bidding.

Abraham riseth and saith:

Ah, Lord of Heaven and King of bliss, Thy bidding shall be done, i-wiss! A hornèd wether here I see, Among the briars tied is he, To Thee offered shall he be Anon right in this place.

Then let Abraham take the lamb and kill him.

Sacrifice here sent me is, And all, Lord, through Thy grace.

Envoi

Such obedience grant us, O Lord!

Ever to Thy most holy word. That in the same we may accord As this Abraham was bayn; And then altogether shall we That worthy King in Heaven see, And dwell with Him in great glorye For ever and ever. Amen.

From the Chester Mystery Plays

3 Canticle III: Still falls the Rain

The Raids, 1940. Night and Dawn

Still falls the Rain –

Dark as the world of man, black as our loss –Blind as the nineteen hundred and forty nails Upon the Cross.

In the Potter’s Field, and the sound of the impious feet

On the Tomb:

Still falls the Rain

In the Field of Blood where the small hopes breed and the human brain

Nurtures its greed, that worm with the brow of Cain.

See, see where Christ’s blood streames in the firmament:

It flows from the Brow we nailed upon the tree

Deep to the dying, to the thirsting heart

That holds the fires of the world, – darksmirched with pain

As Caesar’s laurel crown.

Then sounds the voice of One who like the heart of man

And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly

And the villages dirty and charging high prices:

A hard time we had of it.

At the end we preferred to travel all night, Sleeping in snatches,

With the voices singing in our ears, saying That this was all folly.

Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley,

Still falls the Rain

With a sound like the pulse of the heart that is changed to the hammer -beat

Still falls the Rain

At the feet of the Starved Man hung upon the Cross.

Christ that each day, each night, nails there, have mercy on us –

On Dives and on Lazarus:

Under the Rain the sore and the gold are as one.

Still falls the Rain –

Still falls the Blood from the Starved Man’s wounded Side

He bears in His Heart all wounds, – those of the light that died, The last faint spark

In the self-murdered heart, the wounds of the sad uncomprehending dark, The wounds of the baited bear –

The blind and weeping bear whom the keepers beat

On his helpless flesh … the tears of the hunted hare.

Still falls the Rain –

Then – O Ile leape up to my God: who pulles me doune –

Was once a child who among beasts has lain –

‘Still do I love, still shed my innocent light, my Blood, for thee.’

Edith Sitwell (1887–1964), from The Canticle of the Rose

4 Canticle IV: Journey of the Magi

‘A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp, The very dead of winter.’

And the camels galled, sore-footed, refractory, Lying down in the melting snow.

There were times we regretted

The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces,

And the silken girls bringing sherbet.

Then the camel men cursing and grumbling

And running away, and wanting their liquor and women,

And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters,

Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation; With a running stream and a water -mill beating the darkness,

And three trees on the low sky,

And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow.

Then we came to a tavern with vine-leaves over the lintel,

Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver,

And feet kicking the empty wine-skins,

But there was no information, and so we continued

And arrived at evening, not a moment too soon Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory.

All this was a long time ago, I remember, And I would do it again, but set down

This, set down

This: were we led all that way for Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly, We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms, But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods. I should be glad of another death.

T.S. Eliot (1888–1965), published by Faber and Faber Ltd, reprinted by permission

5 Canticle V: The Death of Saint Narcissus

Come under the shadow of this gray rock –Come in under the shadow of this gray rock, And I will show you something different from either Your shadow sprawling over the sand at daybreak, or Your shadow leaping behind the fire against the red rock: I will show you his bloody cloth and limbs And the gray shadow on his lips.

He walked once between the sea and the high cliffs When the wind made him aware of his limbs smoothly passing each other And of his arms crossed over his breast. When he walked over the meadows He was stifled and soothed by his own rhythm. By the river

His eyes were aware of the pointed corners of his eyes

And his hands aware of the pointed tips of his fingers.

Struck down by such knowledge

He could not live men’s ways, but became a dancer before God.

If he walked in city streets

He seemed to tread on faces, convulsive thighs and knees.

So he came out under the rock.

First he was sure that he had been a tree, Twisting its branches among each other And tangling its roots among each other. Then he knew that he had been a fish

With slippery white belly held tight in his own fingers,

Writhing in his own clutch, his ancient beauty

Caught fast in the pink tips of his new beauty.

Then he had been a young girl

Caught in the woods by a drunken old man

Knowing at the end the taste of his own whiteness,

The horror of his own smoothness, And he felt drunken and old.

So he became a dancer to God, Because his flesh was in love with the burning arrows He danced on the hot sand Until the arrows came.

As he embraced them his white skin surrendered itself to the redness of blood, and satisfied him.

Now he is green, dry and stained With the shadow in his mouth.

T.S. Eliot, published by Faber and Faber Ltd, reprinted by permission Cycle for Declamation

6 I. Wee cannot bid the fruits

Wee cannot bid the fruits come in May, nor the leaves to sticke on in December. There are of them that will give, that will do justice, that will pardon, but they have their owne seasons for all these, and he that knows not them, shall starve before that gift come. Reward is the season of one man, and importunitie of another; Feare is the season of one man, and favour of another; friendship the season of one man, and naturall affection of another; and hee that knowes not their seasons, nor cannot stay them, must lose the fruits

John Donne (1572–1631), from Meditation XIX

transplanted, but transported, our dust blowne away with profane dust, with every wind.

John Donne, from Meditation XVIII

8 III. Nunc, lento sonitu

Nunc, lento sonitu dicunt, morieris.1 The bell doth toll for him that thinkes it doth. Morieris. Who casts not up his Eye to the Sunne when it rises? but who takes off his Eye from a Comet when that breakes out? Who bends not his eare to any bell, which upon any occasion rings? Morieris. But who can remove it from that bell which is passing a peece of himselfe out of this world? Nunc, lento sonitu dicunt, morieris. No man is an Iland, intire of it self; every man is a peece of the Continent, a part of the maine; if a Clod bee washed away by the Sea, Europe is the lesse, as well as if a Promontorie were, as well as if a Mannor of thy friends or of thine owne were. Morieris. Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankinde. Morieris. And therefore never send to know for whom the Bell tolls; It tolls for thee. Nunc, lento sonitu dicunt, morieris.

John Donne, from Meditation XVII

7 II. In the wombe of the earth

In the wombe of the earthe, wee diminish, and when shee is delivered of us, our grave opened for another, wee are not

1 Now, this bell tolling softly for another, says to me: Thou must die (Donne’s translation; literally: ‘Now they say with their slow sound, you will die’)

A versatile performer, James Way’s career takes in a variety of concert, opera and recital repertoire. The music of Benjamin Britten is a cornerstone of his repertoire, most recently performing Winter Words in recital with Malcolm Martineau for Britten–Pears Arts and Flute A Midsummer Night’s Dream for Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Garsington Opera and the BBC Proms. In demand as an interpreter of Handel, his performances have won praise internationally including Messiah with Handel & Haydn Society Boston, Les Arts Florissants and Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, Lurcanio Ariodante with Il Pomo d’Oro and Zadok Solomon with the English Concert under Harry Bicket at Carnegie Hall, as well as the tenor solo in a tour and recording of L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato with William Christie and Les Arts Florissants. Other highlights include Young King in George Benjamin’s Lessons in Love and Violence with Orchestre de Paris conducted by the composer, regular collaborations with conductor Barbara Hannigan in repertoire including Stravinksy Pulcinella and Mozart Requiem, Schubert Winterreise with Natalie Burch and Handel Nine German Arias alongside Rachel Podger. James was a choral scholar at King’s College London and continued his studies at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama with Susan Waters. He was second prize winner in the Kathleen Ferrier Awards and is a former Britten–Pears Young Artist.

An alumna of Chetham’s School of Music, King’s College London and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, Natalie Burch is a dedicated song pianist and curator, interested in the political and social intersection of music and its audiences. Natalie is committed to programming compelling and challenging recitals which she regularly presents in recital at festivals across Europe. She is also a passionate advocate for increasing female representation in the song-piano world.

Much in demand as a song specialist, Natalie regularly collaborates with a number of awardwinning artists. Recent and future projects include her debut at the Aldeburgh Festival alongside Lotte Betts-Dean and James Way, recitals with Roderick Williams and James Newby at the Oxford International Song Festival and a chapter on the songs of Elizabeth Maconchy for the upcoming Cambridge University Press book on her works. She is a Samling Artist, winner of the Maureen Lehane prize for piano at Wigmore Hall and is an alumna of the Britten–Pears, Leeds Lieder and International Lied Festival Zeist Young Artist programmes. Natalie is Associate Artistic Director of the Oxford Lieder Festival 2024 and founder of the Devon Song Festival.

Lotte Betts-Dean is an Australian mezzosoprano based in the UK with a wide-ranging repertoire and a passion for curation,

programming and collaborative project development. Praised for her ‘irrepressible sense of drama and unmissable, urgent musicality’ (Guardian) and ‘arrestingly opulent voice’ (Gramophone), Lotte is equally at home in chamber music, art song, contemporary repertoire of all kinds, early music, opera and narration. Lotte is an Associate of the Royal Academy of Music, an Ambassador for Donne UK – an organization supporting women in music – and was named Young Artist of the Year at the 2024 Royal Philharmonic Society Awards. Lotte is a regular at major festivals and venues across the UK, Australia and Europe, including Wigmore Hall, Kings Place, Aldeburgh Festival, Oxford Song, West Cork Chamber Music and Australian Festival of Chamber Music, and her operatic credits in baroque, twentieth-century and contemporary opera include Grand Théâtre de Genève, Bayerische Staatsoper and State Opera of South Australia. Lotte is a Young Artist alumnus of Britten–Pears Arts (2022), City Music Foundation (2019) and Oxford Lieder (2020). Lotte has recorded for Naxos, Divine Art Métier, Another Timbre, Platoon, BIS and Tall Poppies, among others; for Delphian she has recorded music by Stuart MacRae (Earth, thy cold is keen, DCD34297) and The Past and I: 100 Years of Thomas Hardy (DCD34307). She studied at the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music and the Royal Academy of Music, as well as completing a Fellowship at Australian National Academy of Music.

Hugh Cutting is a graduate of the Royal College of Music where he was a member of the International Opera Studio. On graduating, he was awarded the Tagore Gold Medal, presented by King Charles III. In the autumn of 2021, Hugh became the first countertenor to win the Kathleen Ferrier Award and to become a BBC New Generation Artist (2022–4).

In his first professional season, Hugh made his debut at Opernhaus Zürich singing Monteverdi Madrigals in Christian Spuck’s ballet setting, sang Arsace Berenice on tour in Europe with William Christie and Les Arts Florissants, made his debut at Wigmore Hall, and sang Bach’s St Matthew Passion at Carnegie Hall with Bernard Labadie and the Orchestra of St Luke’s, marking his US debut.

The 2023–4 season sees him touring with Les Arts Florissants as Polinesso in Handel’s Ariodante, with Il Pomo d’Oro again as Arsace, and with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment in Bach’s Christmas Oratorio with Masaaki Suzuki. He will make role debuts as the Boy in George Benjamin's Written on Skin in Stavanger, Ariel in Anthony Bolton’s new Island of Dreams at Grange Park Opera, Dardano in Handel’s Amadigi with The English Concert and Harry Bicket, and as Corindo in Cesti’s Orontea in his debut at La Scala Milan.

Biographies

Annemarie Federle is Principal Horn of the London Philharmonic and Aurora orchestras, and she regularly appears as guest principal with other major orchestras in the UK, including the London Symphony, Royal Philharmonic, Philharmonia and BBC Scottish Symphony orchestras. Annemarie also regularly works as a session musician, and can be heard playing on various film, TV and video game soundtracks, such as Wonka, The Little Mermaid, Citadel and Mission Impossible.

Annemarie was a grand finalist in the BBC Young Musician 2020 competition, performing Ruth Gipps’s Horn Concerto with the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra. In 2021, she was also a semifinalist in the prestigious ARD International Music Competition and winner of the Gianni Bergamo Classic Music Award. Following these successes, Annemarie has enjoyed a diverse solo career, performing concertos with the LPO, English Chamber Orchestra, and London Mozart Players, among others, and recitals and chamber music across the UK and Europe, including at the Lucerne Festival.

Originally from Germany, Annemarie grew up in Cambridge and recently graduated with a First-Class Honours degree from the Royal Academy of Music in London.

Former Official Royal Harpist (2019–24), Alis Huws is a freelance soloist, orchestral and chamber musician. She regularly gives recitals across the UK and internationally, having toured to Japan, Europe, the US, Hong Kong and the Middle East. Alis was privileged to perform at His Majesty King Charles III’s Coronation at Westminster Abbey, where she performed Sir Karl Jenkins’ arrangement of ‘Tros y Garreg’ (Crossing the Stone) for solo harp and strings, as well as being a part of the prestigious Coronation Orchestra, formed specially for the occasion. Other high-profile engagements include the Welsh National Service of Prayer and Reflection for HM Queen Elizabeth II, and the Royal Opening of the Senedd 2016 and 2021. Additionally her work has been broadcast on BBC Radio 3, BBC Radio 4, Classic FM, BBC Radio Wales, BBC Radio Cymru and all major UK television channels.

Named on Classic FM’s 30 under 30 Rising Stars list for 2024, Alis completed both her Bachelor and Master’s degrees at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, where she was awarded the Midori Matsui Prize for Music, the Royal Welch Fusiliers Harp Prize, the McGrennery Chamber Music Prize, and the Rev. Paul Bigmore Music in the Community Award. She was made an Honorary Associate of the college in 2022.

An alumnus of London’s Royal Academy of Music and National Opera Studio, Ross Ramgobin has sung for companies including The Royal Opera, London, English National Opera, Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Opera Holland Park, Welsh National Opera, Angers Nantes Opera, Israeli Opera and Nederlandse Reisopera, as well as at the Aldeburgh, Brisbane Baroque, Göttingen, Verbier and White Nights of St Petersburg festivals.

Concert engagements have included projects with The Bach Choir, BBC Concert Orchestra, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, BBC

Symphony Orchestra, Britten Sinfonia, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France and Radio Filharmonisch Orkest.

His recordings include Handel’s Agrippina from the Göttingen Festival on Accent and Stanford’s Requiem with City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra on Hyperion, as well as The Royal Opera’s Rusalka on Opus Arte (Blu Ray / DVD) and films of Owen Wingrave and L’Heure espagnole for Grange Park Opera.

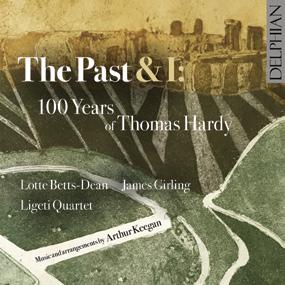

The Past & I: 100 Years of Thomas Hardy

Lotte Betts-Dean mezzo-soprano, James Girling guitar, Ligeti Quartet

DCD34307

Conceived during a residency at The Red House, Benjamin Britten’s former home, in 2019, this collection of new compositions and arrangements by Arthur Keegan shows the profound influence of Thomas Hardy’s poetry on composers throughout the twentieth century and into our own era. Hardy’s characteristic themes are present throughout: the relentless passing of time; nature and the changing seasons; the effects on both of the modern world, with its machines and timetables. Keegan’s Elegies for Emma, for voice and guitar, seeks to restore the voice of Hardy’s first wife Emma alongside the regret-filled poems Hardy wrote after her death, while String Quartet No 1 (‘Elegies for Tom’) weaves instrumental meditations on Hardy’s poem ‘Afterwards’ together with vocal interludes setting Philip Larkin.

‘heart-rending poignancy … The performances of James Girling and the Ligeti Quartet are perceptive and sympathetic; Lotte Betts-Dean provides an admirable range of vocal colours and timbres’ — Gramophone, September 2024

Our

Indifferent Century: Britten – Finzi – Marsey – Ward

Francesca Chiejina soprano, Fleur Barron mezzo-soprano, Natalie Burch piano

DCD34311

In 1914 Thomas Hardy wrote of ‘our indifferent century’; a generation later W.H. Auden urgently sought to fuse the political with the creative. Today, profoundly unsettled by the turn of the world’s politics, three artists respond with a programme that explores the changes and challenges we face presently, but one that also offers hope, levity an even a degree of irreverence, and never loses sight of the joy and beauty of nature. Hardy and Auden found their perfect musical counterparts in the songwriting of Finzi and Britten; in our own times William Marsey and Joanna Ward add their own musical voices of political urgency and wistful yearning.

‘thought-provoking, beautifully executed and timely’ — BBC Music Magazine, December 2023

Unveiled: Britten – Tippett – Gipps – Browne – Thomas

Elgan Llŷr Thomas tenor, Craig Ogden guitar, Iain Burnside piano

DCD34293

In Jeremy Sams’ new English-language singing version of Britten’s Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo, the passionate sentiments are liberated from the safe historical distance of the Italian Renaissance and unveiled in a way that was not possible in 1940, when Britten wrote the cycle – his first for his partner Peter Pears. Tenor Elgan Llŷr Thomas presents it alongside Michael Tippett’s equally ardent Songs for Achilles and a short item by W. Denis Browne, a close friend of the poet Rupert Brooke, as well as premiere recordings of four Brooke settings by Ruth Gipps and a new song-cycle by Thomas himself, to poems by Andrew McMillan. Tackling themes of love, shame, acceptance, war and death, the programme traverses a history of male homosexuality from necessary discretion to the (relatively) liberated present.

‘Thomas and Burnside do [the music] full, impassioned justice’ — Presto Music, April 2023, EDITOR’S CHOICE

From a city window: songs by Hubert Parry

Ailish Tynan, Susan Bickley, William Dazeley, Iain Burnside

DCD34117

Recorded in the music room of Hubert Parry’s boyhood home, Highnam Court in Gloucestershire, this disc sees three of our finest singers shed light on an area of the repertoire that has rarely graced the concert hall in recent times. Iain Burnside and his singers rediscover what has been forgotten by historical accident – and what a treasure chest of song they have found!

Still best known for two short choral works, Parry is at last undergoing something of a revival, and these beautiful performances return his songs to the heart of his output, where the composer always felt they belonged.

‘The emotional range of these songs, almost faultlessly conceived in terms of textual rhythm, reminds us of just how expert a song-writer and pioneer of the English art Parry was ... The performances are exquisite’ — Gramophone, April 2013

Britten: Suites for Solo Cello

Philip Higham

DCD34125

Britten’s meeting with Mstislav Rostropovich in 1960 was a watershed, the great Russian cellist becoming the primary collaborator of his later years and inspiring a whole series of masterworks. Among them are these three suites for solo cello, written as a conscious homage to those of Bach (there were originally to have been six). Britten scholar Paul Kildea, author of the lucid and perceptive booklet essay, sees the first as a coda to the War Requiem, the second as a snapshot of a lifetime of musical obsessions, and the third as both reaching back to much earlier works and suffused with Russian melody. Higham brings both vigour and a deep intelligence to this remarkable music.

‘a towering achievement … This is music that has consistently brought out the best in performers and you can hardly go wrong whichever you choose. This one should be near the top of your list, though. It is very special’

— International Record Review, April 2013

A Festival of Britten

National Youth Choirs of Great Britain / Ben Parry et al.

DCD34133 (2 discs)

The National Youth Choirs’ thirtieth birthday coincided with Britten's centenary, and this double album was the result. Over the course of a year, Delphian engineers followed the various choirs on their courses, and all seven groups appear on disc for the first time here – six hundred singers, eight conductors, in three different venues. The vast range of Britten’s choral output encompasses work to match the character of each of the different choirs, from the fresh-faced eagerness of the Training Choirs to the maturity and sophistication of the elite Chamber Choir. The vocal discipline of all these singers, their energy and their sheer enthusiasm are vividly conveyed in this unique double birthday celebration.

‘the joy of fresh voices cleanly singing a generous cross-section of Britten’s output … With a master text-setter like Britten you don’t want the words obscured; luckily the disc’s various acoustics make his genius crystal-clear’

— The Times, November 2013

Stuart McRae: Earth, thy cold is keen

Lotte Betts-Dean mezzo-soprano, Sequoia

DCD34297

In 2021, entranced by his first encounter with the voice of mezzo-soprano Lotte Betts-Dean, Stuart MacRae embarked on an extraordinary flurry of compositional activity, completing no fewer than eight vocal works in the space of two years. Sometimes entirely alone, sometimes joined by the composer himself on harmonium or electronics or by the violin-and-cello duo Sequoia (who also contribute two instrumental items), Betts-Dean’s compelling presence is at the very centre of this haunting album, which reveals the extent to which MacRae’s recent music has expanded to embrace folk-like simplicity alongside the modernist techniques of his earlier work.

‘conjures an aural landscape steeped in folk music and medieval lyric, but the result is entirely distinctive and modern … This is music for slow, close listening, beautifully performed’

— The Guardian, August 2023

Dreams and Fancies: English music for solo guitar

Sean Shibe

DCD34193

Barely half a century ago, the guitar was such a rarity in the concert hall that even an outstanding player like Julian Bream was remarkable as a pioneer as much as for his exceptional technique and musicality. Today, by contrast, the field is richly populated – thanks not only to Bream’s own inspiring example to younger players but also to the vastly increased repertoire, so much of which he also instigated. Yet even in this new heyday for the instrument, Sean Shibe – whose full album debut here nests among four of those Bream-commissioned works a clutch of Dowland pieces from a previous Elizabethan Golden Age –stands out as a truly uncommon talent. ‘I want to hear his interpretation of Britten’s Nocturnal over and over,’ wrote David Nice in an awed recent concert review. ‘This, for me, is the definitive performance.’