John Sheppard S acred choral mu S ic

missa cantate

Gaude virgo christiphera hymns, responds, antiphons choir of St mary’s cathedral, edinburgh duncan Ferguson

missa cantate

Gaude virgo christiphera hymns, responds, antiphons choir of St mary’s cathedral, edinburgh duncan Ferguson

choir of St mary’s cathedral, edinburgh duncan Ferguson

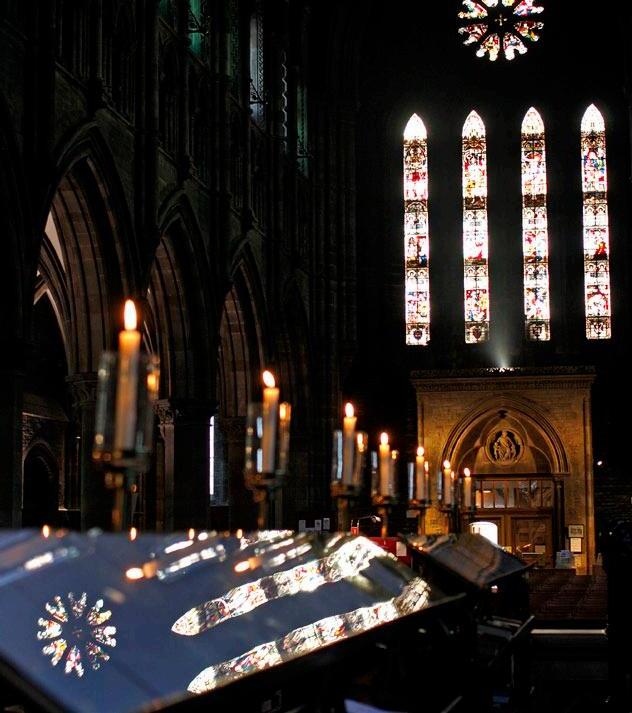

Recorded on 29-31 January and 18-20 September 2013 in St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh by kind permission of the Provost

Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter

24-bit digital editing: Adam Binks

24-bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter

Cover image and booklet photography © Colin Dickson Design: John Christ Booklet editor: Henry Howard Delphian Records Ltd – Edinburgh – UK www.delphianrecords.co.uk

With thanks to St Mary’s Cathedral Music Society

Join the Delphian mailing list: www.delphianrecords.co.uk/join

Like us on Facebook: www.facebook.com/delphianrecords

Follow us on Twitter: @delphianrecords

Libera nos, salva nos I

Reges Tharsis et insulae

Gaude virgo Christiphera

Sacris solemniis

Kyrie Lux et origo (Kyrie Paschale)

Missa Cantate

& Benedictus

Dei

Hodie nobis caelorum rex

Verbum caro

playing time

Despite the extensive work of scholars and editors, as well as the concert and recording projects undertaken by groups such as The Sixteen, the Tallis Scholars and others, a significant portion of the surviving music of John Sheppard remains underperformed and, in some cases, entirely neglected. Several pieces are still unrecorded, and only a minority are in the repertoire of the cathedral and chapel choirs of today that most closely resemble the sort of ensemble Sheppard would have known: first at Magdalen College, Oxford, where he directed the choir in the 1540s, and later at the Chapel Royal, of which he became a Gentleman some time before 1552.

To a great extent this is due to the slow appearance of modern editions of Sheppard’s music, itself a result of his works’ poor preservation: most are preserved in just one source, the Baldwin partbooks copied in the 1580s, one of which, furthermore, is missing. Sheppard’s absence from the 1920s publication Tudor Church Music was in part an unfortunate consequence of the delay which ensued in the attempts to reconstruct his pieces. Performing versions of Sheppard only started to appear in the 1970s; with the publication of two volumes of the Early English Church Music series, edited by Nicholas Sandon and David Chadd, and in the editions of his works prepared by David Wulstan, Sheppard’s music was brought to performers and the public for the first time

in many centuries. Yet it is only now that a complete published edition of his surviving output is within sight, at written pitch and with lost parts reconstructed wherever feasible. Widespread performance of Sheppard’s lesser-known works has consequently become possible, and with it a more thorough appreciation of his music overall.1

While there remains uncertainty about Sheppard’s birthdate (1515 seems the most likely), the first confirmed reference to the composer is his appointment to Magdalen College, Oxford, as Informator Choristarum in 1541. Magdalen’s choral foundation of sixteen choristers and twelve clerks had been established in 1480, and had already employed some of the country’s finest musicians including Richard Davy, John Mason and Thomas Appleby. It is known that Sheppard became a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal some time after leaving Magdalen, though he seems to have retained a link with the College for many years after his official departure in 1548. At the Chapel Royal during the 1550s Sheppard would have been in good company, including the great Thomas Tallis, Christopher Tye and Richard Farrant. Like them he lived through a period of extraordinary religious change, from the introduction of English liturgies in the

1 A third EECM volume edited by Magnus Williamson (2012) has recently appeared. I am very grateful to Dr Williamson for his contribution to this recording project in conversations and e-mail correspondence.

1540s, to the second Book of Common Prayer (1552), which gave no provision for music at all, to the restoration of full-blown Catholicism under Queen Mary (1553–58). It is from this later period that almost of all of Sheppard’s surviving Latin music is thought to date, despite the fact that on supplicating for a doctorate in 1554 he claimed in his submission to have been composing music ‘for twenty years’. Sheppard’s English music, which represents a small portion of his output, presumably dates from the reign of Edward VI (1547–53) and the end of King Henry VIII’s reign (1509–47), when English texts were gradually being introduced to services.2 It has generally been assumed that the ‘John Scheperde’ who was buried on 21 December 1558 at St Margaret’s Church, Westminster is the composer, although some have argued it is more likely he died the following month. In either case he lived long enough to see the accession of the Protestant Queen Elizabeth (1558–1603) and the beginning of the further religious changes that this entailed.

Stylistically, Sheppard was a composer of his time, responding not just to the implications of religious change but also to developments in composition that were taking place on the Continent as well as in England. Despite his significant contribution to the development of

2 The first service in the vernacular was Cranmer’s translation of the Litany, published 27 May 1544. From 1548, all services were supposed to be said (or sung) in English.

music for the Anglican rite (most importantly his Second Service), it is perhaps inevitably his Latin music that is of most interest and on which his place in the history of the period is chiefly judged. Here there are elements of the florid, pre-Reformation English style which had enjoyed its final full flowering in the music of John Taverner two decades earlier, while there are also clearly more modern influences. There has been a tendency among scholars not to see his music either as shaping stylistic change, or as the culmination of one style or another. Yet it is difficult to reconcile the ‘certain sameness about much that he wrote’ (in the words of Hugh Benham), and the negative slant this implies, with the sheer range and breadth of the music. Unlike Tallis, Sheppard did not live long enough to enjoy the benefits of being a favoured composer of the Elizabethan settlement and all the privileges this entailed, and the problem of missing or incomplete music has already been mentioned. Much of his surviving music does in fact contain great variety and novelty, textural contrast and striking dissonances, features that set it apart from the approach taken by his contemporaries (Tallis included) in similar works. One of his earliest advocates wrote that ‘when like is compared with like, there is little doubt that Sheppard is an Olympian figure of mid-sixteenth-century polyphony.’3

3 David Wulstan, Tudor Music (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1985), pp. 273-4

Gaude virgo Christiphera demonstrates Sheppard at his most elaborate. Sheppard’s only surviving Marian antiphon, the origin of its obscure text is unknown – it is particularly unusual for the period in having a rhyming text. Gaude virgo Christiphera has suffered from a lack of modern performances owing to the missing treble partbook (only a very small section of Sheppard’s original treble part survives in another source). Unlike missing tenor parts, in the middle of the texture and thus not so exposed, or any missing cantus firmus parts which can easily be restored with reference to the plainsong, recreating a treble part is more challenging.4 The piece has some similarities with Tallis’s votive antiphon Gaude gloriosa, which probably dates from the reign of Queen Mary. Sheppard’s work is melismatic and florid, firmly Taverneresque in style, in the great English preReformation tradition: the piling up of imitative entries in the ‘Amen’ is particularly reminiscent of Taverner’s O splendor glorie The influence of the Continental style, evident in much of Sheppard’s other work, is less obvious here. An argument has been made, partly on these stylistic grounds, that the piece was written in the 1540s although it remains most likely that it dates from the 1550s, along with almost all Sheppard’s other surviving Latin works.

The Missa Cantate is by far Sheppard’s most elaborate festal Mass setting (and his only Mass in six, rather than four parts), again linking stylistically with the English pre-Reformation tradition of Taverner and yet almost certainly written during the mid-1550s. Like the votive antiphon, the festal Mass went out of fashion during the 1540s but returned under the restored Catholicism of Queen Mary, albeit considerably reduced in length (Tallis’s Missa Puer natus est of 1554 being another example). The reason for the name ‘Cantate’ (‘sing’) is unknown, although presumably has something to do with the (unidentified) material on which some of the music is based: an intermittent cantus firmus in the tenor, and the opening bars common to each movement.5 The Missa Cantate is composition on a grand scale and easily overshadows Sheppard’s other Mass settings.6

In the Sarum use there was no place for a Kyrie in the Mass: the text was occasionally set by composers for certain other services. Kyrie Lux et origo (or Kyrie Paschale) was written for Second Vespers of the Resurrection. In all the sources Sheppard’s Kyrie is followed by the Easter Haec Dies : after the two pieces a copyist wrote ‘finis the best songe in England’

4 Until recently the only credible version was an unpublished edition by David Wulstan, transposed up a minor third, which was recorded by The Clerkes of Oxenford in the 1980s. The new version by Magnus Williamson (which the editor does not claim to be definitive) is recorded here for the first time. 5 Roger Bray has suggested one of the tunes associated with the canticle ‘Cantate Domino’ as a possibility.

6 Benham goes as far as to label the Western Wynd Mass ‘probably the least accomplished of Sheppard’s works’.

and, in another, ‘finis a good songe excellente good’.7 Given that Sheppard’s works have been poorly preserved it is reassuring to know that contemporaries rated his music so highly.

Sheppard’s largest group of surviving works is the Responds, pieces that fulfil a liturgical function between readings or as processions, depending upon their position in the Divine Office. The structure of both Reges Tharsis et insulae and Verbum caro follows the wellestablished practice of placing the plainsong in the tenor, although Sheppard’s responsory settings are slightly more florid than those of his contemporary, Thomas Tallis. Verbum caro, the ninth and final responsory at Matins on Christmas Day, sets words from John 1: 14, ‘And the word was made flesh and dwelt among us …’. Reges Tharsis (‘The Kings of Tharsis and the isle offer their gifts’) is a Matins responsory for the feast of Epiphany. Both pieces luxuriate in the full sound of rich choral textures. Hodie nobis caelorum rex is totally different, as it was written with a specific occasion in mind, setting as it does the very first responsory for Matins of the Nativity. Four soloists sing the verse ‘Gloria in excelsis’ detached and distant from the rest of the choir which sings the plainsong. The intended soloists appear to be three trebles, with the fourth part sung by a very agile tenor, quite possibly the singing teacher to the three trebles. The

7 British Museum, MSS 30480 (f.68v) and 30484 (f.8)

splendour of the music coupled with the effect of distancing one group of singers from the other would surely have made a major impact as the first music heard early on Christmas morning. This is the first recording of the piece sung as it was almost certainly intended.

In addition to these Responds, Sheppard wrote a large number of hymns alternating plainsong verses with polyphony: the polyphonic verses use the plainsong melody, usually in the treble part. Yet, unlike Tallis, Sheppard varied the pattern, particularly when making two settings of the same words. In the second setting of the Trinity Vespers hymn Adesto sancta Trinitas, also recorded here for the first time, the cantus firmus is in the tenor (Sheppard placed it in the treble for his first setting of the same words). While this setting is rather typical of Sheppard’s hymn-writing style, and of the period, the Corpus Christi hymn Sacris solemniis is an altogether different affair. Verses two, four and six are set polyphonically, with the outer verses sharing the same music (whereas the usual pattern was that consecutive polyphonic verses had the same music). The piece splits into eight parts, although more than six rarely sound at the same time, with an unusually embellished plainsong melody placed in the treble voice. The treble itself splits into two at various places, singing in gymel. The false relations, many of them simultaneous, are very striking, while the use of antiphony at ‘dicens:

accipite’ between the high, soaring plainsong melody in the triplex (treble) II and the other voices is surprisingly dramatic and highly novel. Sacris solemniis is a fine achievement. Here the florid, ornamental writing which had characterised English music before the Reformation and contrasting contemporary techniques influenced by the Continent come together in what David Chadd has called one of Sheppard’s ‘richest and most masterly works’.

The high-lying plainsong verses of Sacris solemniis may suggest the ongoing use of faburden, the practice of singers improvising a three-part harmonisation of plainchant that is known to have flourished in England since 1430 or even earlier. Later sources imply that whereas it had formerly been placed in the middle of the three voices, the chant had come to be sung in the top part (as was usual in the related, but different, fauxbourdon ), before its demise along with that of plainchant more generally in England.

Libera nos, salva nos I is, along with the second setting of the same words, widely known today, and certainly one of Sheppard’s

most beautiful compositions. Although the text belongs to Matins on Trinity Sunday as an antiphon to a psalm, it may well have been written for a specific use at Magdalen College, Oxford. The college’s founder Bishop William Waynflete decreed in the college statutes that the antiphon ‘Libera nos’ should be said by the president, fellows and scholars twice a day.

With the plainchant in the bass part underlying a rich seven-part scoring, Libera nos, salva nos I has a serene beauty to modern ears that surely moved sixteenth-century listeners too: perhaps it is not too difficult to imagine the college community gathered in its chapel to hear it at the beginning or close of the day.

© 2013 Duncan Ferguson

1 Libera nos, salva nos

Libera nos, salva nos, iustifica nos, O beata Trinitas.

2 Reges Tharsis et insulae

Reges Tharsis et insulae munera offerent, reges Arabum et Saba dona Domino Deo adducent. Et adorabunt eum omnes reges, omnes gentes servient ei. Reges Arabum et Saba dona Domino Deo adducent. Gloria Patri et Filio et Spiritui Sancto. Domino Deo adducent.

Responsory for First Vespers or Third Matins on the feast of Epiphany

3 Gaude virgo Christiphera

Gaude virgo Christiphera quam adumbrans lux divina selegit ex virginibus

Sola ut esses singulari quam contigit decorari partu imbuta caelibus.

Ex te semen hoc divinum cuius caput serpentinum est contritum viribus,

Free us, save us, absolve us, O blessed Trinity.

Let the kings of Tharsis and the island offer gifts, the kings of the Arabs and Saba bring presents to the Lord God. And all kings will worship him, all nations serve him. Let the kings of the Arabs and Saba bring presents to the Lord God. Glory to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit. Let them bring [presents] to the Lord God.

Rejoice O virgin, bearer of the Christ-child, whom the dazzling divine light selected from all virgins

So that thou alone shouldst be the one whom it befell to be honoured with an unique birth engendered from heaven.

From thee this divine seed is issued forth, by whose strength the serpentine head is trodden underfoot.

Christum dico designatum sed pro nobis incarnatum ex tuis visceribus.

Ergo Sathan mors peccatum hinc videtis procreatum ut vestra habens capita.

Laus sit patri et maiestas tibi Christe rex potestas qui consopisti omnia. Amen.

4 Sacris solemniis

Sacris solemniis iuncta sint gaudia, et ex praecordiis sonent praeconia; recedant vetera, nova sint omnia, corda, voces, et opera.

Noctis recolitur cena novissima, qua Christus creditur agnum et azyma dedisse fratribus, iuxta legitima priscis indulta patribus.

Post agnum typicum, expletis epulis, corpus dominicum datum discipulis, sic totum omnibus, quod totum singulis, eius fatemur manibus.

I mean him that was called Christ, but was made flesh for us from thy loins.

Therefore, Satan, death, and sin, ye behold him born here that he may crush your heads.

Praise be to the Father, and majesty and power unto thee, Christ the King, who hast laid them all to rest. Amen.

translation © Leofranc Holford-Strevens

Let joys conjoin with sacred solemnities, and let prayers resound from our very hearts; let old things recede and all be renewed: hearts, voices, deeds.

We commemorate the supper of that evening when Christ, the Lamb as we believe, broke bread with his brethren, in accordance with patriarchal custom.

After the figural lamb was consumed, the instituted feast was done, the Lord’s body was shared among the disciples: thus one and all received of him by their hands.

Dedit fragilibus corporis ferculum, dedit et tristibus sanguinis poculum, dicens: Accipite quod trado vasculum; omnes ex eo bibite.

Sic sacrificium istud instituit, cuius officium committi voluit solis presbyteris, quibus sic congruit, ut sumant, et dent ceteris.

Panis angelicus fit panis hominum; dat panis caelitus figuris terminum; O res mirabilis: manducat Dominum pauper, servus et humilis.

Te, trina Deitas unaque, poscimus: sic nos tu visitas, sicut te colimus; per tuas semitas duc nos quo tendimus, ad lucem quam inhabitas. Amen.

St Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), hymn for First Vespers on the feast of Corpus Christi

5 Kyrie Lux et origo (Kyrie Paschale)

Kyrie eleison (x3), Christe eleison (x3), Kyrie eleison (x3).

He gave the weak the nourishment of his body, and to the sad the cup of his blood, saying: Take the vessel I hand to thee, and drink this all of ye.

Thus he instituted that sacrifice whose performance he first committed to his chosen priesthood who, having themselves partaken, would share it with others.

Thus bread of angels becomes bread of men; heavenly manna supplants worldly simulacra. What a wonder: the master is eaten by pauper, slave and meek.

Threefold deity, as we pray to thee, may ye visit us; and in thy footsteps lead us towards the light which thou dost inhabit. Amen.

translation © Magnus Williamson

Missa Cantate

6 Gloria

Gloria in excelsis Deo et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis.

Laudamus te. Benedicimus te.

Adoramus te. Glorificamus te. Gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam.

Domine Deus, Rex caelestis, Deus Pater omnipotens.

Domine Fili unigenite, Jesu Christe;

Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris.

Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecationem nostram.

Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, miserere nobis.

Quoniam tu solus Sanctus, tu solus Dominus, tu solus Altissimus, Jesu Christe.

Cum Sancto Spiritu in gloria Dei Patris. Amen.

Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to men of good will. We praise you. We bless you.

We worship you. We glorify you.

We give you thanks for your great glory.

Lord God, heavenly King, God the Father Almighty.

Lord, the only-begotten Son, Jesus Christ; Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us.

Who takes away the sins of the world, receive our prayer.

Who sits at the right hand of the Father, have mercy upon us.

For only you are Holy, only you are Lord, only you are Most High, Jesus Christ. With the Holy Spirit in the glory of God the Father. Amen.

Lord have mercy, Christ have mercy, Lord have mercy.

7 Credo

Credo in unum Deum, Patrem omnipotentem, factorem caeli et terrae, visibilium omnium et invisibilium. Et in unum Dominum Jesum Christum, filium Dei unigenitum, et ex Patre natum ante omnia saecula. Genitum non factum, consubstantialem Patri; per quem omnia facta sunt. Qui propter nos homines et propter nostram salutem descendit de caelis. Et incarnatus est de Spiritu Sancto, ex Maria Virgine; et homo factus est. Crucifixus etiam pro nobis sub Pontio Pilato, passus et sepultus est. Et resurrexit tertia die secundum scripturas, et ascendit in caelum, sedet ad dexteram Patris, et iterum venturus est cum gloria iudicare vivos et mortuos, cuius regni non erit finis, et vitam venturi saeculi. Amen.

I believe in one God, the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all ages. Begotten, not made; consubstantial with the Father, by whom all things were made. Who for us men, and for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man. He was crucified also for us, suffered under Pontius Pilate, and was buried. On the third day he rose again according to the Scriptures, and ascended into heaven. He sits at the right hand of the Father, and shall come again with glory to judge the living and the dead. And there shall be no end to his Kingdom, and the life of the world to come. Amen.

8 Sanctus & Benedictus

Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus.

Dominus Deus Sabaoth: Pleni sunt caeli et terra gloria tua. Hosanna in excelsis.

Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini: Hosanna in excelsis.

9 Agnus Dei

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona nobis pacem.

Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of Sabaoth.

Heaven and earth are full of your glory.

Hosanna in the highest.

Blessed is he that comes in the name of the Lord:

Hosanna in the highest.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, grant us peace.

10 Adesto sancta Trinitas

Adesto sancta Trinitas, par splendor una deitas, qui extas rerum omnium sine fine principium.

Te caelorum militia laudat, adorat, predicat, triplexque mundi machina benedicit per saecula.

Assumus et nos cernui te adorantes famuli, votaque preces supplicum hymnis iunge caelestium.

Unum te lumen credimus quod et ter idem colimus; Alpha et O quem dicimus te laudat omnis spiritus.

Laus Patri sit ingenito, laus eius unigenito, laus sit Sancto Spiritui, trino Deo et simplici. Amen.

Be present, Holy Trinity, single Godhead of equal splendour, who stand forever at the beginning of all things.

The army of heaven praises you, worships you, proclaims you, and the triple edifice of the world blesses you through the ages.

We too, your humble servants take our part in worshipping you; join prayers and supplications to the hymns of the heavenly ones.

We believe you to be one light, which we worship too as three; you whom we call Alpha and Omega, all living things praise.

Let praise be to the unbegotten Father, praise to his only-begotten Son, praise be to the Holy Spirit, the threefold and single God. Amen.

11 Hodie nobis caelorum rex

Hodie nobis caelorum rex de virgine nasci dignatus est, ut hominem perditum ad regna caelestia revocaret: gaudet exercitus angelorum, quia salus aeterna humano generi apparuit. Gloria in excelsis Deo, et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis. Quia salus aeterna humano generi apparuit.

First responsory for Matins on the feast of the Nativity

12 Verbum caro

Verbum caro factum est et habitavit in nobis cuius gloriam vidimus quasi unigeniti a Patre plenum gratiae et veritatis. In principio erat verbum et verbum erat apud Deum et Deus erat verbum. Cuius gloriam vidimus quasi unigeniti a Patre plenum gratiae et veritatis.

Gloria Patri et Filio et Spiritui Sancto. Plenum gratiae et veritatis.

Ninth responsory for Matins on the feast of the Nativity

Today the king of heaven deigned to be born for us of a virgin, that man that was lost might be called back to the heavenly kingdom: the host of angels rejoices, for eternal salvation has come for the human race. Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to men of good will. For eternal salvation has come for the human race.

The word was made flesh and dwelt among us, whose glory we have seen as of the only begotten of the Father, full of grace and truth. In the beginning was the word, and the word was with God, and the word was God. Whose glory we have seen as of the only begotten of the Father, full of grace and truth. Glory to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit. Full of grace and truth.

The Choir of St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh is unique in Scotland in maintaining daily choral services in the Anglican tradition. The Cathedral was the first in the United Kingdom to allow girls to join boys as trebles in 1978. The choristers are educated at St Mary’s Music School, Scotland’s specialist music school, while the lay clerks of the choir consist of university choral scholars alongside more experienced singers.

The choir has an extensive discography on Delphian. In January 2010 a disc of works by the sixteenth-century composer John Taverner (DCD34023) was released to critical acclaim, earning an ‘Outstanding’ accolade from International Record Review and five stars from Classic FM Magazine, and reached seventh place in the Specialist Classical Chart. The following year a CD of Bruckner Motets was released (DCD34071), earning a Gramophone Editor’s Choice (and a Gramophone Recommendation in 2012) and with the choir being described by The Times as ‘a choir of humans who sing like angels’. Other works recorded by the choir include the Fauré and Duruflé Requiems, and several premiere recordings of works by Arvo Pärt, James MacMillan (DCD34017), Sir Peter Maxwell Davies (DCD34037) and Gabriel Jackson (DCD34027), including many works written for the choir. A second disc of music by Gabriel Jackson (Beyond the Stars, DCD34106) was

released in 2012, again earning a Gramophone Editor’s Choice and ‘Outstanding’ from International Record Review

In addition to its recording work, the choir is renowned for its commitment to contemporary music. In January 2013 the choristers sang with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra in a concert marking the sixtieth birthday of American composer John Zorn, and then took part in the Glasgow ‘Tectonics’ Festival, again with the BBC SSO, singing music by Frank Denyer, under the direction of Ilan Volkov. The choir sang a new piece by Dave Heath as part of the Qatar-UK Year of Culture Concert with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra in June 2013.

The choir regularly broadcasts on BBC Radio. During the Edinburgh Festival the choir is in residence, singing the daily services as well as concerts and broadcasts. The choir has worked closely with period ensembles Ludus Baroque and the Dunedin Consort. Major international tours in recent years have included the USA and Canada (2008) and then in 2011, at the invitation of the Taipei International Festival and the Little Singers of Tokyo, a tour of Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan. Venues included the National Concert Hall, Taipei, and Suntory Hall, Tokyo. The choir has been invited to tour Germany with the Nuremberg Symphony Orchestra in 2015.

Treble

Emily Jarron

Head Chorister

Neil Jeacock

Head Chorister

Anna Cooper

Deputy Head Chorister

Hugh Mackay

Deputy Head Chorister

Charlie Bradshaw

Katie Bradshaw

Max Carsley

Susanna Davis

Esme Frith

Peter Gill

Malachy Harris

Naima Heath

Amy-Felicity Horsey

Dominic Markus

Catherine Marple

Maisie Michaelson-Friend

Ciara O’Neill

Amber Phillips

Jacob Slater

Alto

William Fox-Roberts

Rory McCleery

Michael Wood

Tenor

Andrew Bennett

Oliver Brewer

Sam Clarke

Sam Jenkins

James Wood

Baritone

Sandy McCleery

Alex Robarts

James Skuse

George Wood

Bass

Christopher Borrett

Sam Carl

Matthew Davies

Duncan Ferguson Organist and Master of the Music

Donald Hunt Assistant Organist

Andrew Forbes Organ Scholar soloists in Missa Cantate soloists in Gaude virgo Christiphera soloists in Hodie nobis caelorum rex

Duncan Ferguson was appointed Organist and Master of the Music at St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh in April 2008 while still in his mid-twenties. He has responsibility for the musical life of St Mary’s, and in particular for recruiting, training, and directing the Cathedral Choir. Immediately prior to his appointment he was Assistant Organist at St Mary’s, playing the organ for the daily services, concerts, and broadcasts. As an undergraduate he held the organ scholarship at Magdalen College, Oxford, where special events included various live broadcasts, recordings, and accompanying the premiere of an oratorio written by Sir Paul McCartney. He gained a distinction for his Master of Studies degree, researching the role of music at St Margaret’s Church, Westminster during the Reformation.

From 2003–5 he was Organ Scholar of St Paul’s Cathedral, where duties included regular recitals, accompanying and directing the Cathedral Choir, and playing the organ at diocesan and national services. He was also a Tutor at King’s College London.

Recent solo work has included recitals at St Davids Cathedral in Wales and at St Mary’s Metropolitan Cathedral, Edinburgh, workshops for the Royal College of Organists and the Royal Schools of Church Music, and various performances during the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.

Duncan’s recordings with St Mary’s have gained critical acclaim. Of his first Delphian recording with the choir (music by John Taverner, DCD34023), The Times wrote:

‘Duncan Ferguson is plainly a wizard.’

Bruckner: Motets

Choir of St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh / Duncan Ferguson

RSAMD Brass

DCD34071

Ferguson and his Edinburgh choir turn their attention to one of the nineteenth century’s compositional giants. This sequence of motets –among them several little-known gems – is a testament to Bruckner’s profound Catholic faith, and the performances blaze with fire and fervour in the vast cathedral’s icy acoustic.

‘Under its young director Duncan Ferguson, the choir is reaching new heights with its CDs for Edinburgh label Delphian. They always sounded fresh-voiced; now, following last year’s Taverner disc, the atmospheric richness of this new recital of Bruckner motets has generated a CD potent enough to knock major-label competitors into the long grass’

The Times, April 2011

Taverner: Sacred Choral Music

Choir of St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh / Duncan Ferguson

DCD34023

John Taverner brought the English florid style to its culmination; his music is quite unlike anything written by his continental contemporaries. In his debut recording with the critically acclaimed Edinburgh choir, Duncan Ferguson presents this music with forces akin to those of the sixteenth century – a small group of children and a larger number of men. The singers respond with an emotional authenticity born of the daily round of liturgical performance.

‘Treble voices surf high on huge waves of polyphony in the extraordinary Missa Corona Spinea, while smaller items display the same freshness, purity and liturgical glow. Duncan Ferguson, the Master of Music, is plainly a wizard’ The Times, February 2010

Gabriel Jackson: Beyond the Stars (Sacred Choral Works Vol II)

Choir of St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh / Duncan Ferguson

DCD34106

Gabriel Jackson’s long association with the Choir of St Mary’s Cathedral continues with this second volume of sacred choral music, released to celebrate his fiftieth birthday. Under Duncan Ferguson’s dynamic direction they bring a special authority, and all their characteristic verve and intensity, to a sequence of recording premieres that centres on the florid Hymn to St Margaret of Scotland, newly written for the choir. This sumptuously recorded disc opens a dazzling window on the luminous sound-world of one of Britain’s finest choral composers.

‘It’s easy to get so wrapped up in the ravishing delights of Jackson’s writing that you forget the astonishing quality of these performances’ Gramophone, October 2012

Jean Maillard (fl. 1538–70): Missa Je suis déshéritée & Motets

The Marian Consort / Rory McCleery

DCD34130

Jean Maillard’s life is shrouded in mystery, and his music is rarely heard today. Yet in his own time his works were both influential and widely disseminated: indeed, the musicologist François Lesure held him to be one of the most important French composers of his era. The Marian Consort’s characteristically precise and yet impassioned performances bring out both the network of influence in which Maillard’s music participated – its Josquinian pedigree, and influence on successors including Lassus and Palestrina – and its striking, individual beauty.

‘The performances are models of discretion and musical taste, every texture clear, every phrase beautifully shaped’

The Guardian, October 2013