Chopin Wilde plays

Wilde plays Chopin vol ii

Frederic Chopin (1810–1849)

David Wilde piano

Two Nocturnes Op. 27

1 No. 1 in C sharp minor

2 No. 2 in D flat major

3 Polonaise in A flat major Op. 53

Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor Op. 35

4 Grave – Doppio movimento

5 Scherzo

6 Marche funèbre: Lento

7 Finale: Presto

8 Nocturne in E flat major Op. 9 No. 2

9 Prelude in D flat major Op. 28 No. 15, ‘Raindrop’

Fantaisie in F minor Op. 49

playing time

The decision to record this music – which has been central to my musical life – was made very shortly following the death of my dear wife Jane in 2013. I dedicate this recording to her memory. DW

Recorded on 14 August, 16 September and 10 - 11 December 2013 at the Reid Concert Hall, University of Edinburgh

Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter

24-bit digital editing & mastering: Paul Baxter

Piano: Steinway Model D Grand Piano, 2012, serial no. 592403

Piano technician: Norman W. Motion

Photography © Delphian Records Ltd Design: Drew Padrutt

Booklet editor: Henry Howard

Delphian Records Ltd – Edinburgh – UK www.delphianrecords.co.uk

Chopin’s first Sonata, Op. 4 in C minor, written in 1825 when he was only 14 years old, is widely regarded as juvenilia and rarely played. Despite its number, therefore, his Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor Op. 35 is his first mature work in this form. It is known as the ‘Funeral March’ Sonata because of its renowned third movement, which is performed around the world on occasions of state mourning. Chopin in fact composed this movement in 1837, two years before he wrote the rest of the Sonata, but most of the work seems to take its cue from the ‘Marche funèbre’, being in the darkest vein (one might perhaps even apply the overworked adjective ‘Gothic’ here).

subject in the Sonata No. 3 in B minor, nevertheless enriches us with another beautiful example of Chopin’s seemingly inexhaustible talent for endlessly flowing melody. This in turn leads to a thrilling passage in triplet crotchet chords and an ecstatic stretto, which ultimately crashes into two fortissimo chords, each two bars long, and a repeat of this exposition.

Join the Delphian mailing list: www.delphianrecords.co.uk/join

Like us on Facebook: www.facebook.com/delphianrecords

Follow us on Twitter: @delphianrecords

The first movement begins with a slow introduction, marked grave, and announced with strong left-hand octaves that suggest the opening of Beethoven’s last Sonata, Op. 111 – although, as will be discussed below, Chopin was the only composer of his time not to declare himself the heir to Beethoven’s tradition. This introduction is followed by a throbbing, broken accompanying quaver figure in B flat minor, marked doppio movimento, which is soon joined by a fragmented, agitated first subject in which a reiterated rhythmic motif is subjected to innumerable melodic transformations. After continuing in a more expansive pianistic style this figure is augmented to become a very short bridge to the broad second subject, in D flat major, which, though not so extended as the corresponding

The development section begins in the startlingly distant key of F sharp minor, and from this point takes the material of the exposition through a series of radical modulations, leading to a grand climax in G minor, which combines the first subject’s initial motif, played this time in double notes, with powerful reiterations and variations of the opening ‘Beethovenian’ bass octaves, supported in the middle register by further double notes in the left hand, the whole pianistic effect resembling Sigismond Thalberg’s illusion of three-handed technique, beloved by Liszt. As in the B minor Sonata, Chopin here follows the traditional principle of classical sonata form in recapitulating the second subject in the tonic major key, in this case B flat, in which key the movement ends with a stretto leading via a crescendo to three semibreve chords of B flat major, marked triple forte .

The second movement is named ‘Scherzo’ but has no specific tempo indication. It is in the subdominant key of E flat minor and in

traditional ‘ABA’ form, the outer sections being Dantesque and demonic in character. The middle section, in the relative major key of G flat, offers gentle, lyrical relief.

Anton Rubinstein, years after Chopin’s tragically early death, was the first pianist to have the idea of understanding the third and fourth movements programmatically: according to him they depict the mourners at a funeral approaching the chapel, attending the service, and withdrawing, leaving the listener alone in the cemetery with the wind blowing over the graves. The better to express this image he effectively places us, the listeners, outside the chapel, making a crescendo as the mourners approach it and ending with fortissimo doubled octaves in the bass, then takes us inside for the service, and leaves us outside again as the music once more pounds out its fortissimo double octaves, making a steady poco a poco diminuendo as the mourners withdraw, leaving the listener alone. The young Sergei Rachmaninov heard Rubinstein play the work and years later incorporated this idea into his own, now iconic recording of it. In my recording for Delphian I have humbly followed the lead of these two giants in this respect.

The Finale, marked presto, is astonishingly ahead of its time – even for Chopin – and the scholar Alan Walker, in his book on Chopin, goes so far as to say that it suggests a twentieth-century spirit trapped by accident

of birth in the early nineteenth century. Robert Schumann, that other great modernist avant la lettre, was startled by it, and indeed commented on the whole Sonata that here Chopin had ‘brought together four of his wildest children’.

If there is any longer a need to dispel the false notion of Chopin as merely the gentle dreamer (though he had that in him too, of course) this Sonata, together with the two great Polonaises in F sharp minor and A flat, the ‘Military’ Polonaise in A major, and the Polonaise-Fantaisie, are the works to do it. This is after all the composer who is reported to have said to a pupil: ‘If I had your strength and could play that Polonaise as it should be played, there would be no string left unbroken by the time I had finished!’1

If we include the Polonaise-Fantaisie and the four posthumous Polonaises, Chopin wrote eleven pieces in this genre. Of these, two in particular have moved the popular imagination: the ‘Military’, Op. 40 in A major, and the Polonaise in A flat major Op. 53, sometimes called ‘Heroic’. Both were of great patriotic significance to a Poland desperately struggling simultaneously against Stalin’s Russia and Hitler’s Germany during World War II, and it was

1 As told by Arthur Hutchings in Alan Walker (ed.), Frédéric Chopin: Profiles of the Man and the Musician (London: Barrie and Rockliff, 1966). The Polonaise in question was the one recorded here, Op. 53 in A flat.

my privilege to play them both, sometimes to Free Polish Airmen stationed in my home town of Blackpool, at that terrible time.

The Polonaise in A flat is the king of polonaises, brilliantly combining the triumphant and the defiant, and pushing piano technique in new directions that bore rich fruit later. The middle section, in E major in particular, with its famous left-hand octave ostinato, clearly influenced the corresponding section of Liszt’s Funérailles, which was composed in 1850, shortly after the deaths of both Chopin himself and of three of Liszt’s friends who died in the abortive Kossuth Revolution against Habsburg rule over Hungary. I particularly enjoy Liszt’s oft-reported remark at his Weimar masterclasses to a student who used this section of the Polonaise to show off his octave technique: ‘No, no, no! I don’t want to hear how fast you can play octaves; I want to hear the prancing of the Polish cavalry!’ – a remark that acquired new and tragic meaning when that same cavalry charged with suicidal heroism against Hitler’s invading tanks on 2 September 1939.

After the cavalry charge comes a brief time of reflection, leading to a final peroration of the original ‘heroic’ theme, followed by a coda ending with what Alfred Cortot described as ‘victory chimes’ in the left hand, a final brief reminder of the cavalry charge, and a powerful cadence in Polonaise rhythm.

The intimate Nocturne in E flat major Op. 9 No. 2 is the second earliest published piece in its genre by Chopin, and remains one of the most popular. As with many of his works, there are several versions, all authentic, simply because Chopin was very active as a teacher and his students naturally wanted to learn his music; as there were no copying facilities in those days Chopin had to choose between engaging copyists and doing the work himself. He chose the latter, and in the process often seems to have had new ideas as he copied. In this case some of the alternatives (published in the excellent Wiener Urtext edition) are almost unbelievably ornate; I favour, and have here recorded, the simplest version.

Quite rarely programmed in recitals, the Nocturne in C sharp minor Op. 27 No. 1 is, by contrast, a darkly dramatic tone poem, expressive of profound gloom and inner turmoil. The work begins coldly and noncommittally with left-hand arpeggios of fourths and fifths, so that we are uncertain whether we are in the major or minor key. Then the righthand melody seems to resolve the mystery, introducing, as if from beyond the grave, a ghostly E – the minor third – in the register beloved of Chopin in much of his lyrical music, around an octave and a half above middle C. But this melody rises first to an E sharp (the major interval) and then to an F sharp, only to fall back to C sharp via E and D, leaving us again unsure where we stand – major or minor?

This uneasy phrase sets the tone for the deep feelings of insecurity and pessimism with which the work is endowed, and it falls away to an inconclusive B sharp (the leading note) before apparently failing, as if from shortness of breath, just a beat before the expected resolution onto the tonic C sharp.

The middle section introduces an element of impending danger, with a bass rising in threatening semitones under a sinister triplet figuration, culminating in a funereal climax, in heavy left-hand legato octaves (in small note heads, implying senza tempo), effectively a downward-moving recitative which returns to the despairing mood of the opening like a coffin being lowered into a grave.

In the recapitulation that follows, the ethereal melody is joined by a more earthly theme below it, and I may perhaps be permitted to make the personal point that since the death, from cancer, of my beloved wife Jane in August 2013, this passage suggests to me an eerie dialogue between us, from opposite sides of the Great Divide. After this dialogue, the Nocturne at last resolves to a kind of peace, in the major key, and this devoutly Roman Catholic composer ends the work with a beautifully arranged plagal cadence, subdominant to tonic: the traditional ‘Amen’.

piece in C sharp minor in its tenderly passionate character and its consoling message; indeed it is the ultimate ‘Consolation’, as Liszt called his set of pieces of this kind. However, there is nothing in Liszt’s set to come anywhere near the eloquence, the grandeur, or the sheer inventiveness of this glorious piece. Chopin’s Nocturnes, in general, are unique in the repertoire, and this is one of the greatest and best known. It is an outstanding example of his mastery of the ‘cantabile’ or singing style, which one might even say that he invented – with respectful nods in the direction of the Irish composer John Field, who first coined the name ‘Nocturne’ for this kind of music, and the violinist Paganini, who inspired Chopin to write his two sets of Etudes, Op. 10 and Op. 25, and to develop further than any other composer the lyrical cantabile style on the piano for which he had shown a strong instinct even in his earlier works. Indeed there are passages here strongly suggestive of double-stopping on the violin.

not even to know the ranges of some of the instruments.) The D flat Nocturne is one of the best examples of Chopin’s total identification with his instrument and the cantabile style; like Schubert, Chopin never ceased to sing.

essentially episodic form and, for Chopin, its surprisingly plain, undecorated piano style. In modified ABA form, the Fantaisie begins with a slow, extended introduction which (in Rafael Joseffy’s edition published by Schirmer) is headed ‘Tempo di Marcia’ and marked grave, and seems to recall the funeral march from the B flat minor Sonata.

The much-loved Nocturne in D flat major Op. 27 No. 2 contrasts sharply with its companion

As is well known, Chopin lived and breathed through the piano, and after a few songs, his early piano trio and the piano concertos – also written when he was very young – he confined himself entirely to solo compositions for his own instrument until near the end of his short life, when he wrote his great sonata for cello and piano; and I find orchestral arrangements of his works, such as the ballet Les Sylphides, unsatisfactory. (Chopin’s own lack of interest in the orchestra was so great that he seemed

Chopin was almost alone among his contemporaries in showing no interest in Beethoven. All the others, except Verdi, regarded themselves as the heirs to the Beethovenian tradition; even Rossini admired and visited Beethoven and wept when he saw the sordid conditions in which the impoverished, sick and deaf composer was living, while Wagner would often return to the score of his ninth symphony for inspiration. But Chopin’s way was generally quite different, and his models were Mozart (whose Requiem was played at his funeral, at his request) and J.S. Bach, whose music he is reported to have practised at the start of every working day. This, in turn, gave him a particular place in the later history of European music; his works gave rise to French Impressionism and the music of Debussy and Ravel in the West, and of Scriabin in the East, all of whom rejected the works and aesthetic of Beethoven.

However, Chopin’s Impromptus do suggest the influence of Beethoven’s devoted disciple, Franz Schubert, and the Fantaisie in F minor Op. 49 is also Schubertian in its large-scale but

The American critic James Huneker, in his preface to the same edition, writes that Liszt told the programme of the beginning of the work, allegedly heard from Chopin himself, to the young pianist Vladimir de Pachmann. According to Pachmann’s account, a depressed Chopin was sitting at his piano when there was a sinister tapping at the door, which he echoes on the keyboard, and the answering phrase represents Chopin’s response: ‘Entrez, entrez.’ Eventually, the door opened and in came George Sand, Liszt, Camille Pleyel, and other friends of the composer. As the music becomes more passionate, George Sand, with whom he had recently quarrelled, falls on her knees to ask forgiveness, and the subsequent emergence of the ‘heroic love chant’ in the A flat section suggests that this pardon is granted.

Meanwhile the music unfolds. At bar 43 the march rhythm gives way to an ominously pregnant legato phrase rising in triplet quavers and culminating in a semibreve fermata (pause), which is immediately repeated a minor third higher. Then it continues to repeat, marked

crescendo and poco a poco doppio movimento (little by little towards double speed), always in a higher key, until at bar 52 it is suddenly interrupted by a grand, rhetorical group of three descending accented double octaves on B flat, marked ff – these are to acquire great motivic significance during the course of the work –ending in a fermata.

This process now starts again, a fifth lower, but this time the triplets continue without interruption in a great dramatic arc, a crescendo to ff covering the entire range of Chopin’s piano and ending on a deep bass C, marked sforzato, which hurls us into the darkly passionate introduction to the main theme, beginning in the tenor register with three accented tones and rising by Paganini-like double thirds to the theme itself – Huneker’s ‘heroic love-chant’ – in the relative major key of A flat, again in Paganini-style double-stopping. There follows a second strain that alternates descending legato octaves with more double-stopping, and an extraordinarily intense eight-bar modulatory passage, crescendo, ending in a powerfully repeated dominant bass ‘organ point’ on a B flat octave, which resolves onto a chord of E flat – the dominant of the relative major key of A flat – and a new subject, in legato octaves, fortissimo, in both hands, basically in contrary motion, alternating with assertively rhetorical six-note chords.

This leads, by more such dramatic devices and modulations, to a second march theme, quite different from the opening funeral march, this one being optimistic in character, though restrained and marked piano. (It is at this point, according to Huneker, that the intruders in Chopin’s music-room vanish away.) This moment is a particularly striking example of Chopin’s ability to orchestrate at the piano, and I have marked the melody ‘Horn Solo’ in my score. The march comes to a dramatic end with a forte chord of a dominant seventh in E major, a semitone higher than the key of the foregoing, and the rising triplets begin again in this new tonality, again describing an arc, and modulating once more, this time supported by a rhetorical chordal figure in the left hand, to an apparent transition via another dominant seventh chord to D flat, at which point the motif of three powerful descending octaves returns, followed by a semitone drop, which announces a recapitulation of the passionate introduction to the main theme, this time in the dominant key of C minor. Here the Paderewski edition repeats the theme, piano (as do I), and the return of the modulatory triplets (forte) leads us to a progressively more tranquil triplet passage, and the descending octave figure returns, this time in pianissimo minim G flats, marked rallentando and ending in a semibreve with a fermata

Understood enharmonically as F sharps, these octaves take us directly into the key of B major in which the music that follows is composed.

It’s the farthest possible point from the home key of F minor, and contrasts with the mood of the rest of the work as much as it is possible to imagine. Marked lento, sostenuto, this beautiful slow middle section is like a calm island lagoon in the midst of a stormy sea, its long lines expressed as legato chords free from all pianistic elaboration, and challenging to the limit the pianist’s ability to sustain legato lines.

After a sustained dominant seventh chord, the calm is interrupted by a diminished triad, sforzato, in the home key of F minor, and the rising triplet figures start again, leading to a return of the rhetorical descending octave figure, this time fortissimo. Now the introduction to the main theme returns in accented octaves, also marked fortissimo, and the music starts building towards a restatement of the heroic love theme, this time often played – as in the present recording – piano.

The abbreviated final section of the work’s ABA form reintroduces the horn solo, this time marked forte, culminating in a terrifying cascade of descending chromatic triplets in both hands, reinforced in the right hand by accented crotchets, that hurls us onto the rocks of a fortissimo restatement, again for solo horn, of the beginning of the lento sostenuto theme of the middle section, now marked adagio sostenuto. After a pause, there follows a dreamy recitative in small note heads – once more implying senza tempo – and ending

with a dominant seventh chord in the work’s relative major key of A flat, in which tonality Chopin finally resolves the drama with a plagal cadence – again the traditional ‘Amen’ – but with a poignantly flattened third in the first, subdominant chord.

It was Alfred Cortot who first realised that the Chopin Preludes were intended to be played as a single work, a carefully planned set of prophetically pre-impressionist miniatures united by a strictly observed sequence of keys; tonic, relative minor; dominant, relative minor; and so on. The little A major Prelude (No. 7) is sometimes played as an encore and that and the C minor (No. 20) are used as teaching pieces, but otherwise the only one that clearly stands on its own is the longest, in D flat major Op. 28 No. 15, the popular ‘Raindrop’ Prelude – so named because of the repeated A flat (enharmonically changed to G sharp in the middle section in C sharp minor), which dominates the piece like an obssessive ostinato, and is said to have been inspired by a continuous dripping from the roof in the Chopin–Sand apartment in Valldemosa, Majorca. However, during a visit to Majorca, my wife Jane and I visited Valldemosa, where the piano on which Chopin composed this and many other pieces is still to be found (though not to be played, of course), and saw that this story could not be quite accurate,

since there is an apartment above, and, if my memory serves me correctly, one above that again. The explanation would seem to be that Chopin probably left the French window leading off his workroom open during the typical Mediterranean warm, wet winter, and that there was a faulty gutter above the terrace outside, resulting in a constant drip.

The piano itself is interesting: it’s a kind of upright in which the frame and casing barely rise above the keyboard, resulting in short bass strings and a small soundboard. The range of timbres available to Chopin on this instrument must have been very limited, though one could hardly guess so from the beauty of the sounds he was able to conjure from it in his composing.

Biography

Pianist and composer David Wilde was born in Manchester in 1935. A busy wartime career as ‘boy pianist’ brought him to the attention of the legendary pianist Solomon, who arranged for Wilde to study with his pupil and assistant Franz Reizenstein. Later, from 1949, Wilde studied composition with Professor Richard Hall at the Royal Manchester College of Music (precursor of the Royal Northern College of Music), of which he was elected a Fellow in 1953. In the same year he was awarded the prestigious Walter Dayas Gold Medal.

In 1961 Wilde won a first prize at the Liszt–Bartók competition in Budapest. The legendary Nadia Boulanger was a jury member, and invited him to visit her in Paris at any suitable time, so when in the same year Wilde was awarded a senior scholarship by the Caird Foundation of Dundee he wrote to accept her invitation and ask if he might work with her. Wilde joined her in Paris and at the Conservatoire Americain in Fontainebleau (of which Boulanger was then Musical Director) in 1963, and again in 1964 and 1968, remaining in close touch with ‘Mademoiselle’ for the rest of her long life. Wilde is a passionate teacher, and his pupils include Jack Gibbons, now pursuing a brilliant career in the USA; Christopher Oakden, now Professor at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater in Hannover; Thomas Hell, winner of the European Competition for contemporary Music in Orleans, and Bulgarian pianist Irina Georgieva. Wilde taught at the Hochschule

für Musik und Theater in Hannover from 1981 to 2000, and was made a Professor Emeritus of the State of Lower Saxony in 1983. He has given many lectures in both English and German, including his paper on psychology and the meaning of music, ‘Listening to the Shadows’. His Jungian analysis of Liszt’s Piano Sonata in B minor, which he read and illustrated at London’s Analytical Psychology Club (of which he is an elected life member), was originally written as a contribution to the book Analecta Lisztiana, ed. Michael Saffle (publ. Virginia Tech, USA).

During the 1990s, having travelled to besieged Sarajevo to support his heroic colleagues there, Wilde composed several works protesting against human rights abuses in our time, notably The Cellist of Sarajevo (1992), the Suite for Violin and Piano, Cry ‘Bosnia-Herzegovina’, the String Quartet (of which the last movement is a ‘Threnody for the Unknown Victim of War and Oppression’), and the opera London under Siege, after an idea by Bosnian poet Goran Simic. The Cellist of Sarajevo, dedicated to Vedran Smailovic, is played the world over and was recorded by Yo-Yo Ma for Sony Classical, and London under Siege was produced by the State Theatre of Lower Saxony in 1998.

Wilde was twice honoured by the Bosnians: in 2003 he was awarded a diploma by the International Peace Committee of Sarajevo ‘for services to human rights in Bosnia-Herzegovina

© 2014 David Wilde

and throughout Europe’, and in 2005 he was presented with the ‘Symbol of the Open Door’, representing honorary Bosnian Citizenship. David Wilde has given many concert tours of the UK and played frequently with all the major London orchestras, all the BBC orchestras, and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, Bournemouth Symphony, City of Birmingham Symphony, Royal Scottish National and Hallé Orchestras.

He has appeared regularly at the Henry Wood Proms with conductors such as Horenstein, Boulez and Downes, and has toured New Zealand and played and taught in Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, India, Russia, the USA, most countries of Western Europe and, of course, Hungary. His recordings include all of Beethoven’s Sonatas for violin and piano and the Sonata by Reizenstein with violinist Erich Gruenberg, Alan Bush’s Variations, Nocturne and Finale on an English Sea Song (in a version for piano and orchestra which Wilde had premiered at the Cheltenham Festival), and concertos by Thomas Wilson (especially composed for Wilde) and Sir Lennox Berkeley. In his recently published diaries Berkeley, who was present at the recording of his concerto, wrote simply: ‘David Wilde was first class.’

More recently, Wilde commissioned a sonata from Gabriel Jackson with funds from the Scottish Arts Council, the Britten-Pears Trust and the Ralph Vaughan Williams Trust, and premiered it at the Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh in

2007. He gave the European premiere of this work during a recital in Braunschweig, Germany in October 2008. Also in 2007 EMI reissued Wilde’s 1968 HMV Liszt recital, coupled with Liszt recordings by Earl Wild.

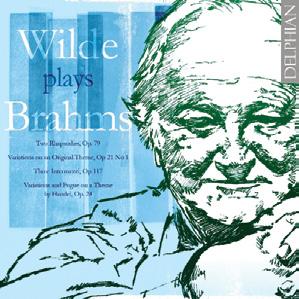

Wilde now records exclusively for Delphian Records: in addition to the present repertoire, a Chopin recital (DCD34010), the complete piano works of Luigi Dallapiccola (DCD34020), a highly acclaimed Liszt Sonata coupled with the seven Elegies of Busoni (DCD34030), a Schumann recital (DCD34050), a Brahms recital (DCD34040) and a Beethoven recital (DCD34090) are available. His most recent disc is Wilde plays Liszt (DCD34118).

David Wilde has two children by his first marriage and now lives on the east coast of Scotland, near Edinburgh. This recording is dedicated to the memory of his second wife, writer and historian Jane Mary Wilde.

Wilde plays Liszt David Wilde piano DCD34118

Fifty years after his victory in the International Liszt–Bartók Piano Competition, David Wilde – student of Solomon and of Nadia Boulanger – brings to the studio a lifetime’s experience with the music of Franz Liszt. The diabolically difficult Mephisto Waltz No. 1 is dispatched in a reading which overflows with personality and conviction, while Funérailles, too, is compellingly reimagined by an artist who cleaves to an earlier generation’s ideals of recreating both the self and the music in every inspired performance. Two groups of song-based works, the tre Sonnetti di Petrarca and the three Liebesträume, complete this very special disc.

‘dazzling … No connoisseur either of Liszt or of commandingly articulate, old-school pianism will want to miss this finely engineered release’ — Andrew Achenbach, The Classical Ear, December 2013, *****