5 minute read

Poland Explore the graphic and subversive world of the Polish School of Posters

History projekt

The Polish School of Posters tells a story of creativity during an age of suppression – and one venture is bringing greater visibility to these highly collectible designs

Words Kate Lawson

Images Courtesy of Projekt 26

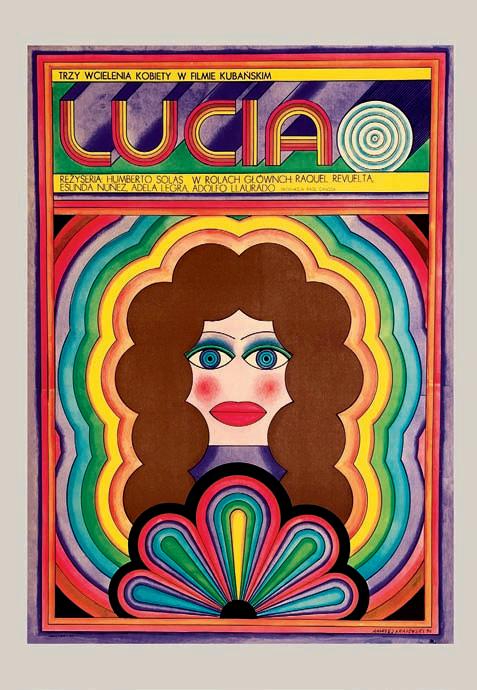

Facing page Clockwise from top left: Cuban film Lucia as imagined by Andrzej Krakewski; Jakub Erol’s poster for a 1970s film comedy; 1972 film poster by Krakewski for Wiem ze jestes Morderca (“I Know You are a Killer“); poster for Russian film Vzroslyy syn (“Grown-Up Son“) by Maria “Mucha” Ihnatowicz

Nowhere has the graphic art of the poster dominated visual culture more than in Poland. Following the second world war, the country’s Soviet-supported communist regime used them as a propaganda tool, commissioning prominent artists such as Andrzej Krajewski, Henryk Tomaszewski, Jan Lenica, Waldemar Świerzy and Wiktor Górka to promote social causes and state-controlled cultural events – from music, dance and film to exhibitions, theatre and the circus.

But what Poland’s government didn’t grasp was the immense potential for subverting a poster’s message. Thus these bold, vibrant works, with their hand-crafted typography, often characterised by surrealist undertones, could be rich in metaphor and multi-layered symbolism imbued with the spirit of anarchy – a subtle rebuke by the artists of the underlying political context of the time. This pioneering art movement became known as the Polish School of Posters, injecting vitality and colour into Poland’s grey urban landscape, while giving hope to passers-by after the devastation of the war and the stinging deprivation of the country’s austere communist system.

By 1989, however, with the fall of communism and the introduction of a free market economy, the role of the poster dramatically changed. Stock advertisements began to replace their signature artistic qualities, marking the end of this highly creative era.

Making it their mission to prolong the lifespan of these unique works are business partners Harriet Williams and Sylwia Newman, the founders of Projekt 26, a venture that collects and sells original Polish posters online and at vintage markets and art fairs. Their name is partly inspired by the Polish magazine Projekt, which had its heyday in the 1960s and 1970s and showcased design from behind the Iron Curtain. “It always included a poster and became a platform for some of the most celebrated artists from the movement,” says Williams, a freelance graphic designer. “The ‘26’ stands for our south London postcode where we met as friends,” she explains.

The duo realised their joint passion for Polish design over a cup of tea while admiring Newman’s second-edition 1979 cyrk (circus) poster, a work called 9 Lions by Tadeusz Jodlowski (“although it’s actually eight lions and a woman if you look carefully,” says Newman). They’ve now amassed around 700 original works from the 1950s to the 1980s.

“Most people don’t know about Polish posters and we were blown away by the response we got after tentatively starting on Instagram,” explains Newman. “We are so passionate about these incredible designs, and want to help preserve them. People contact us from all over the world to buy the posters, and some of our bestsellers include the Krajewskis, which are super popular, and the cyrk, which are iconic.”

The circus posters are a good example of coded meanings: since the bear is a symbol of Russia, a bear on a bicycle, or with a ball, might be read as a comment on Russia’s desire to conquer the world. One Waldemar Świerzy poster shows a pompous-looking bear in a suit, standing next to a tiny bicycle that comically undermines the self-importance of the animal.

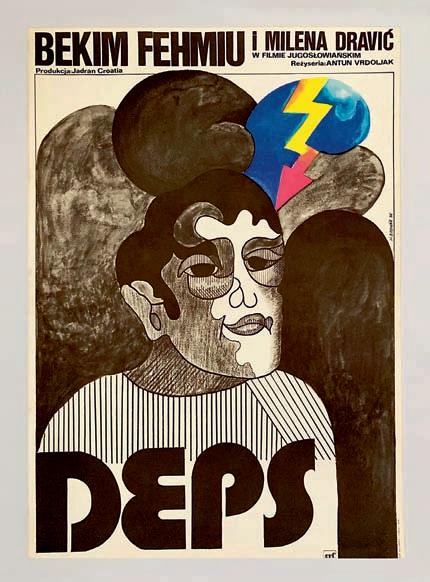

Above Left to right: 9 Lions by Tadeusz Jodlowski; Hanna Bodnar’s poster for 1974 Yugoslavian film Deps

Facing page Dirk Bogarde's 1971 Death In Venice, by Maria “Mucha” Ihnatowicz

The pair cite Krajewski as well as Hanna Bodnar and Maciej Hibner as their favourite artists – although work by the former is becoming increasingly hard to find. “If we do source one, it’s very hard to part with if we don’t have a copy for our own collection,” enthuses Williams. They’re still on the hunt for iconic works, though, such as Swierzy’s posters for Midnight Cowboy and Sunset Boulevard.

The pair strive to find original posters in good condition from all over Poland, sourcing them from cinemas, theatres and printing houses. “Each one was printed with the intention of it being used in strict print runs,” explains Williams. “You can see where most were printed by the information at the bottom, and the type of paper is also a very good indication of provenance as it’s beautiful matte paper.”

Despite many posters not surviving the years in tact, there have been some unexpected surprises. “We found a batch from somebody

whose father-in-law was a distribution driver for a printworks, and had saved some surplus ones,” says Newman. “They were perfect.” A classic Steve McQueen Bullitt poster, which came from a private owner, was in need of attention, however: “It was so rare our buyer was still really happy to have it. We’re always really honest about any marks and flaws so people know what they are buying.”

Despite the posters’ ephemeral nature as markers of time and place, they have had a farreaching impact. The revival of the Polish poster as a small beacon of artistic resistance, counteracting western aesthetic expectations, helps to amplify their importance for future generations. “If you look at an equivalent film poster from the west and a Polish poster from the same time, there is no comparison,” says Williams. “They are bursting with typographic and illustrative creativity. They have a special soulful joy, as well as a dark beauty too. They shine like a beacon among their peers.”

This page Clockwise from top left: Andrzej Krakewski’s Heroina (“Heroin”) poster advertises an East German film from 1968; Mieczysław Wasilewski’s poster for Legenda o miłosci (“Legend of Love”); a cheeky green monkey by Hubert Hilscher advertises the circus

Invest in an annual subscription to Design Anthology UK to receive three issues a year, anywhere in the world