8 minute read

Freedom, Finally

OUR COMMUNITY

ON THE COVER

Advertisement

Freedom, Finally! Recalling the historic arrival of Soviet Jews in Detroit. ASHLEY ZLATOPOLSKY CONTRIBUTING WRITER

In 1981, my mother, Alla Zlatopolsky (maiden name Nisnevich), a Jewish immigrant from what was then the Soviet Union, experienced her first Shabbat dinner at the home of a volunteer family in Metro Detroit. These American families were paired with Soviet Jewish families to teach them about Jewish life.

At 15 years old, my mom, who was born in Bobruisk, Belarus, and grew up in Riga, Latvia, knew little about Judaism. But she, along with the thousands of Soviet Jews who resettled in that area after World War II, weren’t alone in this lack of understanding.

Religion was illegal in the U.S.S.R. due to state-sponsored atheism instilled by the communist regime. Judaism, especially, was not tolerated or permitted. Centuries of antisemitism were deeply ingrained in Russian society, a view that barely improved after the war.

Three million Jews across the Soviet Union from Ukraine to Lithuania faced spiritual extinction. While the physical threat of the Holocaust remained nothing but a terrible, albeit fresh, memory for survivors and their direct descendants, the once-vibrant Jewish life of

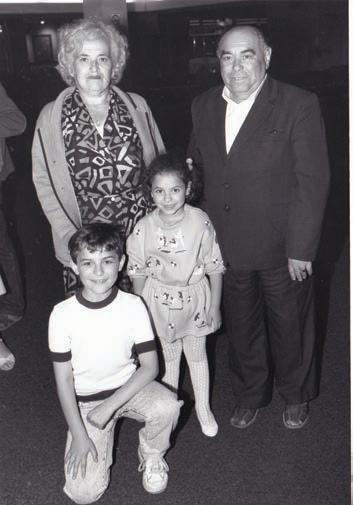

COURTESY OF JFS.

Families welcome their Soviet relatives to Detroit in this historical photo from JFS.

Eastern Europe was virtually nonexistent in the decades that followed the 1940s.

VOIDING JUDAISM

In the U.S.S.R., there were no celebrations of High Holidays or Shabbat dinners. Matzah for Passover, if even considered, was brought home illegally by Jews in pillowcases and briefcases, quietly purchased at underground synagogues housed in the basements of nondescript buildings. Yet, religious suppression was only a small fraction of the problems that Jews living behind the Iron Curtain faced on a day-to-day basis.

Soviet Jews generally weren’t able to pursue higher education. They were denied the right to attend university, unless they could offer a hefty bribe, and faced decreased options in the workforce. In regions of the former Soviet Union where antisemitism was higher than others, it was not uncommon to see antisemitic posters around town.

Jewish children born after World War II were taught from an early age never to speak of their religion. There was a sense of shame attached to being Jewish, like a barrier that couldn’t be budged and negatively impacted every corner of life. In the U.S.S.R., Judaism wasn’t a religion, but a nationality. Having the mark of evrai, or Jew, on the fifth line of one’s passport meant that person would always be at a disadvantage.

Despite growing up with almost no understanding of Judaism and remaining silent about their religion, Soviet Jewish children were still bullied at school. They were called Jewish slurs by classmates, beaten up and even ostracized by teachers. These children would often stick together, uninvited to play with non-Jewish peers. Only their grandparents who grew up in pre-Holocaust years would teach them things like Yiddish lullabies.

For many decades, nothing could be done about this widespread problem. Emigration was illegal in the U.S.S.R., as was Judaism. Millions of individuals couldn’t leave, but they also couldn’t be free in their own country. It was a paradox that was finally relieved following mounting international pressure in the 1960s and 1970s to let the Jews of the Soviet Union go. It would become one of the greatest rescues of the 20th century.

Jews began to slowly trickle out of the U.S.S.R., claiming repatriation to their rightful homeland of Israel. While some Jews continued on to Israel, others would change course and go to America, Canada or Australia, three countries that would accept them in numbers. As the Soviet Union began to crumble, the trickle turned into a stream, which eventually turned into a wave of 2 million Jews leaving the Soviet Union forever.

IN THE SOVIET UNION, THERE WAS A SENSE OF SHAME ATTACHED TO BEING JEWISH ... IT NEGATIVELY IMPACTED EVERY CORNER OF LIFE.

VIA VIENNA-ROME

Most traveled through the Vienna-Rome pipeline, an escape route set up by international Jewish organizations. Upon leaving the Soviet Union, Jews would forfeit their passports, rendering them stateless. Waiting for approval for applications to emigrate took months, sometimes even years, and many Jews were denied. This particular group of people became known as refuseniks and were ostracized by society.

Yet, those who were approved were still considered traitors of the state. They would lose their jobs, friends and personal belongings deemed property of the U.S.S.R., like military medals and artwork. Jews were only allowed to take a certain amount of cash, pushing people to pack precious luggage space with knickknacks to later sell for money. Many also faced verbal abuse and a chaotic emigration system at Soviet Union borders.

Most had no guarantee of a future. They’d wait in Vienna and the greater Rome area for a second round of approval to come to the United States. Bloomfield Hills-based Jenny Feterovich, now 45, remembers being a teenager in Italy with her family in 1989.

“It was adventurous, but at the same time I was very sad,” she recalls. “I left all my friends. I left the comfort of my life. We were living with my parents in one single room without knowing where we’re really going.”

It was common for families or even groups of families to share single rooms as they waited in Italy, facing high rent prices that were unafford-

OUR COMMUNITY

continued from page 11

able for many. By day, they’d stand for hours in Italian markets, selling Sovietmade watches, linens and other goods for money. By night, they’d take English lessons as they prepared for their new lives.

Still, despite their effort and sacrifice, many Jews were denied the right to come to the U.S. “People were there [in Italy] for six months or a year, even more than that,” Feterovich says.

It was the same story over and over during interviews at immigration offices — Soviet Jews explained that they were persecuted. This was why they wanted to go to America. Yet some families received approval while others were left behind.

“I think that immigration person, whoever made that decision, who was sitting on the other end … maybe they were having a good day or bad day,” Feterovich describes, “because how else do you make that kind of decision?”

COURTESY OF JFS.

A Soviet family arrives at Metro Airport in this historical photo.

HEADING TO DETROIT

Luckily for the Feterovich family, who came from Moscow, approval was swift. They made their way to the Metro Detroit area, where they had relatives. Yet for teenagers like Feterovich, who arrived with the expectation to see glimmering lights and bustling avenues like that of New York City, ending up in quiet Oak Park — where many Soviet Jewish immigrants first settled — was an unexpected shock.

“I came from a big city,” she says. “Here I am, Oct. 24, standing in front of Northgate Apartments [in Oak Park], wondering if this is my life. I remember asking my parents, ‘Did you bring me here to die?’ I regret that phrase now, and it’s such a devastating question, but you could say my expectations were not met.”

Most Soviet Jews arrived to small apartments with a scattering of donated furniture. They often only had one or two mattresses, a kitchen table and occasionally an old TV. “I remember our [paired volunteer] family was extremely wealthy,” Feterovich says. “They had a helipad and we had nothing. We were literally sleeping on the floor.”

It was a stark and eye-opening experience on both ends, for the Soviet Jews who had to rebuild their lives from scratch and for the American Jews who often expected the newly arrived Soviet Jews to be, for lack of better words, more Jewish.

“There was this huge separation because we didn’t really know much about Judaism,” Feterovich explains. “All of these people were like, ‘Let’s be Jewish together,’ but we had no idea what that meant.”

Jenny Feterovich and her parents, Nelly and Vladimir Feterovich, on her first day in America in 1989.

NEW AMERICAN WAYS

Yuliya Gaydayenko, chief program officer of behavioral health and older adult services at Jewish Family Service of Metropolitan Detroit, says the influx of Soviet Jewish immigrants coming to the area picked up in the early 1980s and continued through the mid-1990s, stopping sharply with the 9-11 attacks in 2001.

Donations from Jewish families in Metro Detroit helped pay for staff to facilitate the mass arrivals, which included greeting immigrants at airports, placing deposits for apartments and connecting them to government benefits, among other services.

Gaydayenko, who also immigrated from Moscow, estimates that each resettlement cost about $5,000. “This would cover the first three months of the initial resettlement for families,” she explained. After that, immigrants would take over. They were provided with ESL (English as a second language) courses, cultural workshops and other educational programs to learn American ways.

JVS Human Services, meanwhile, helped immigrants find employment and write resumes. Both parents and teenagers often worked multiple jobs to support their families in the first few months or even years. It was common for teenagers to attend school during the day, then work late into the night, sometimes until 2 a.m., in order to help their parents put food on the table.

With the assistance of volunteer families, Soviet Jews would also learn how to do things like grocery shop, read food labels and, of course, experience a Shabbat dinner. Some immigrants grew close to their newly understood religion, opting to become Orthodox. Others became Conversative or Reform, and some not religious at all.

Despite the path they chose, Soviet Jews played a remarkable role in developing Metro Detroit’s Jewish community. From their impact in the workforce to their contributions to society, they became an indisputable and essential part of local life.

Most importantly, though, they were free to make those choices of who they wanted to be. Their children could have a future. And there was no one to tell them they couldn’t be Jewish.