Bold journalism since 1953 Telling it as it is THE MAGAZINE “MADE FOR MINDS” 2023

DW is Germany’s international broadcaster. Our job? Ensuring freedom of opinion around the world with unbiased news and information. Over 291 million people rely on our TV, online and radio coverage each week to make up their own minds. DW Akademie trains journalists worldwide and supports the development of free media. DW’s global staff is made up of nearly 3,000 people from more than 140 countries.

Weltzeit is published by DW and covers freedom, democratic values and our commitment to unbiased information.

Editorial

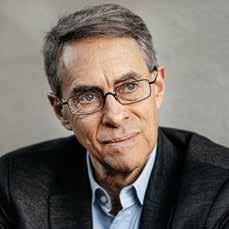

Telling it as it is …

A principle to which DW has remained true for over 70 years.

Since DW went on air in 1953, we have informed our users around the world about the implications of the dramatic changes we have witnessed. In this issue, we are taking decisive moments in recent history as a cue for an outlook on the challenges for our societies which are more interdependent than ever before.

The fallout of the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine has affected not only neighboring countries but caused immediate consequences as far away as the Global South. In effect, this war has taken us to a crossroads in international relations and is bringing about new alliances. The changes on the playing field today are more complicated than during the Cold War. The stakes could not be higher.

While we have a job to do, keeping the public abreast with global developments, journalism around the world is under immense pressure. From autocratic governments, from state actors, armed groups, criminal organizations and even ordinary citizens who have fallen into the trap of disinformation.

Some governments seem to believe that they can hold on to absolute power by controlling the flow of information to their citizens. The digital age has made the circumvention of state censorship easier. People will always find a way to get the full picture.

The role of international broadcasters like DW has become crucial in this context,

making journalism the intermediary for a global audience with independent and objective information. And we strive to live up to our promise to all our users every day.

For any credible media organization, it is key to have people on the ground. DW is officially blacklisted in several countries. I salute our correspondents and reporters who are working against the obstacles put in their way in countries with limited and no freedom of the press.

It is thanks to all the women and men who are so dedicated to their professional calling as journalists, that DW can continue its proud tradition of observing, scrutinizing and holding those responsible to account.

Looking at Russia’s war against Ukraine, I want to mention the impact of professional journalists and media in the context of international armed conflicts. The courageous and diligent work of journalists on the ground is an important contribution to the documented evidence needed to prosecute war crimes and human rights violations.

We understand, that in extreme situations we are journalists and witnesses at the same time, and we act accordingly. This is not touching our impartiality as observers, but a duty as human beings.

Cordially,

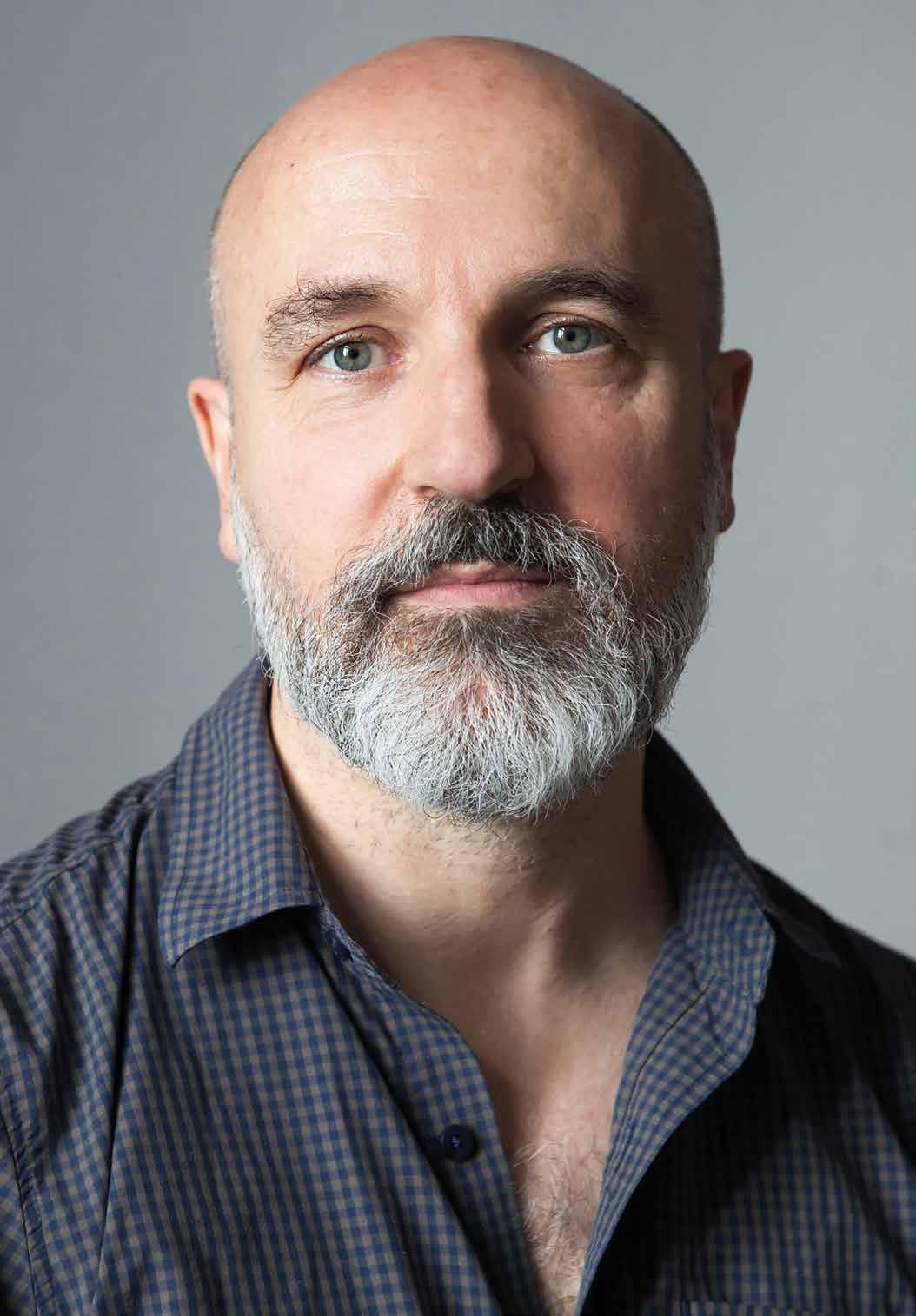

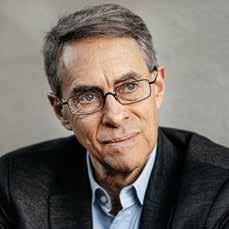

Peter Limbourg Director General @dw_Limbourg

It is thanks to all the women and men who are so dedicated to their professional calling as journalists, that DW can continue its proud tradition of observing, scrutinizing and holding those responsible to account.

3 Weltzeit 2023

© DW / J. Röhl

Contents 26 What do Russians think? 22 Environmental journalism in Brazil remains dangerous LATIM AMERICA Interview with Natalia Zubarevich 54 Tracing service as a lifeline DW's contact program for refugees from the Yugoslav war ENCOUNTERS 9 Mohamad Chreyteh 134 The hope for a better future With Margot Friedländer DW HIGHLIGHTS 10 DW Planet A A global look at climate issues DW Analiza 11 +90 Turkish-language format expands to TikTok 12 Nous, les 77 pour cent French edition launched 13 Guardians of Truth 14 The Campus-Project 2023 Afghanistan and Iran RUSSIA 70 YEARS DW 4

62

Solidarność

LATIN AMERICA

16 ¡Venceremos! Latin America with new self-confidence

20 The corrosive power of violence Media in Mexico

UKRAINE

29 Delivering justice for the war crimes

32 The new Ukrainian reality

BELARUS

40 The Nobel Peace Prize behind bars

70 YEARS DW

42 DW A brief history

44 Milestones

48 Our global network

50 The echo of history DW Greek

58 Rescue from Kigali Days of anguish in Rwanda

Bringing aggressors to justice

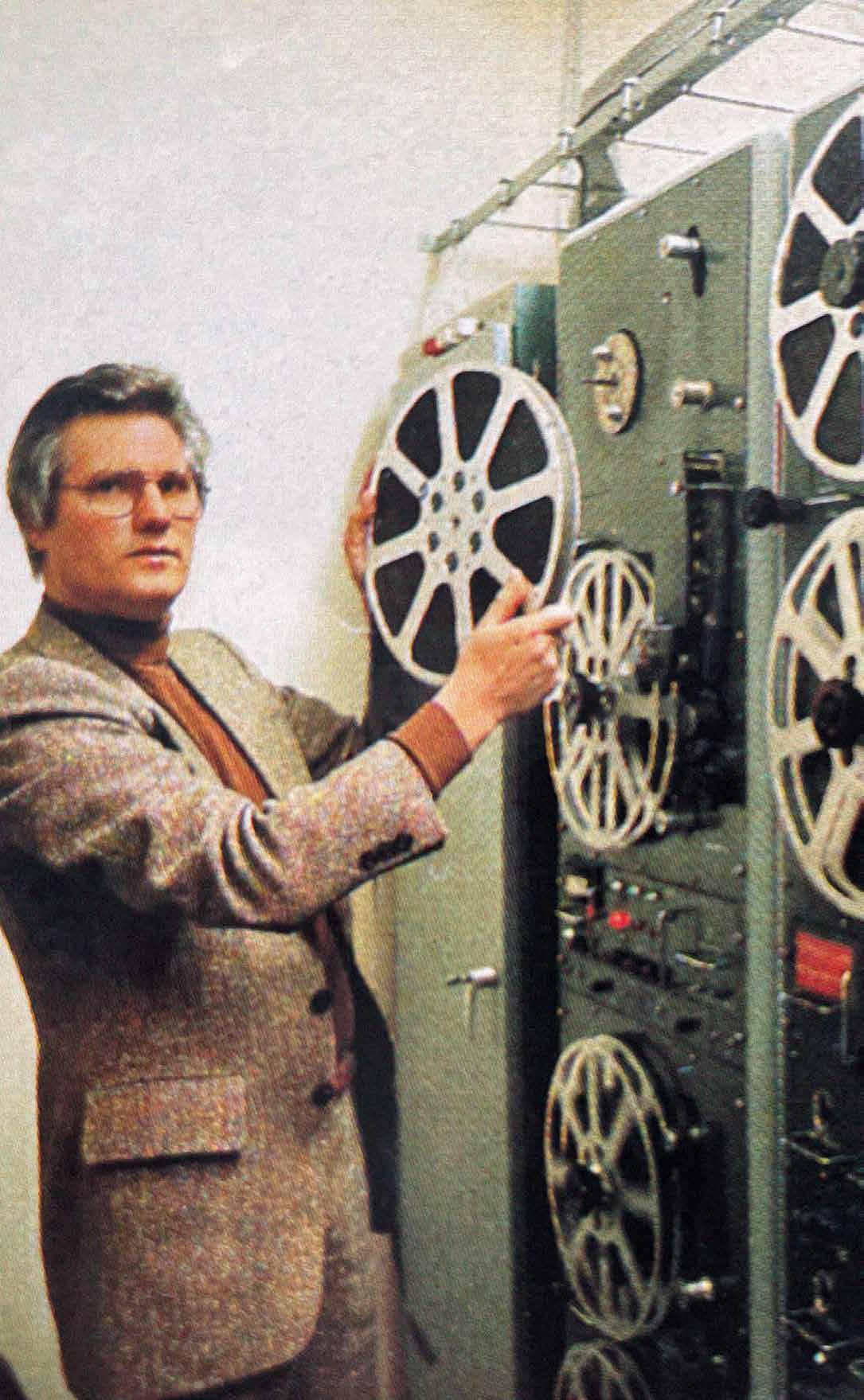

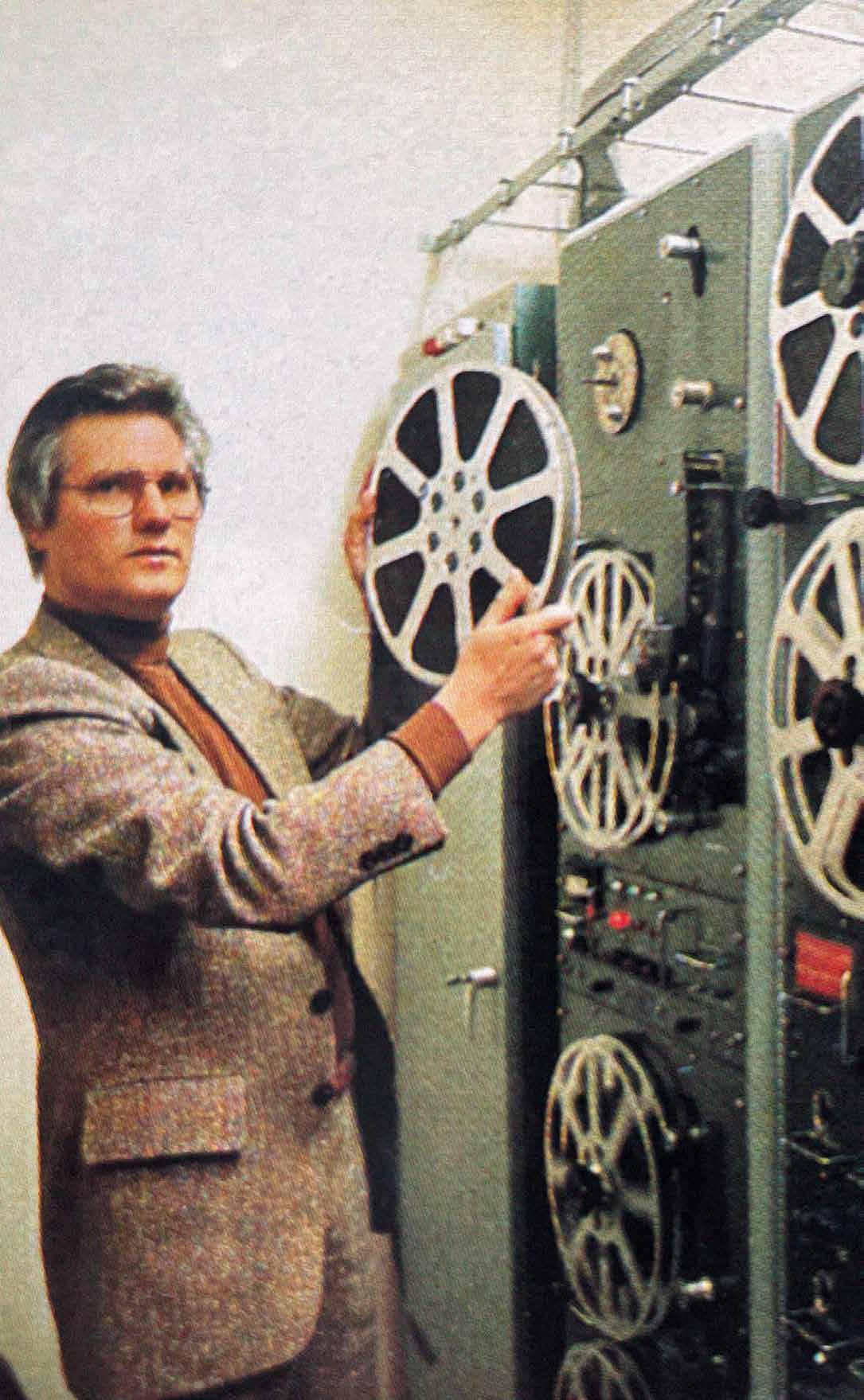

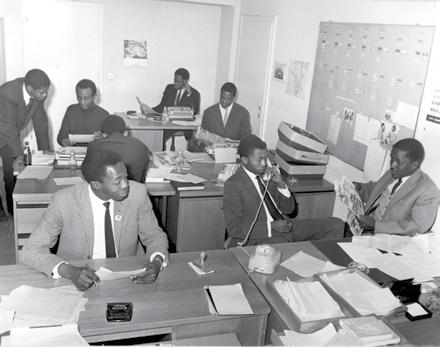

60 The early days of broadcasting

Interview with Hans-Jürgen Reher

66 A look back in time

36

70 YEARS DW UKRAINE 5

When Lech Wałęsa addressed the Soviets on DW Radio

74 Walking a very thin line

AFRICA 70 Ignored, underrepresented, underestimated The media’s view of Africa 77 Press freedom in Nigeria 80 Using media as a weapon Russia’s influence in Africa GLOBAL IMPACT 84 Getting climate on the news agenda 88 No more refugees, please 90 Can the EU stop migration in Libya? 92 InfoMigrants DW’s information platform for migrants and refugees 94 Best relations for the time being 96 The tsunami of global hunger 100 Turning a blind eye to a real threat Critical reporting in the cradle of democracy 102 A Taiwanese view on the island’s future 104 Who is responsible? Afghanistan under the Taliban 110 Facing off at the Olympic Games Athletes talk about boycott 114 Human trafficking Bulgarian organized crime networks 118 Parallel universes … by Uğur Gallenkuş

Journalism in Cameroon AFRICA ©

Melgrati 138 Woman Life Freedom IRAN 6 CONTENTS

Marco

107 Elections in Turkey

MEDIA DEVELOPMENT

122 Developing media. Supporting human rights.

Now more than ever

126 Understanding trauma could be the key to resiliency

Interview with Gavin Rees

129 Strengthening the voices of women

Yemen

132 Predicting the future DW trainees

IRAN

FREEDOM OF SPEECH

147 Raif Badawi

148 An ally in the fight for press freedom

70 years of DW

151 Weaponizing the law to silence journalists

TECHNOLOGY

154 Viral but irrelevant

158 Challenging censorship

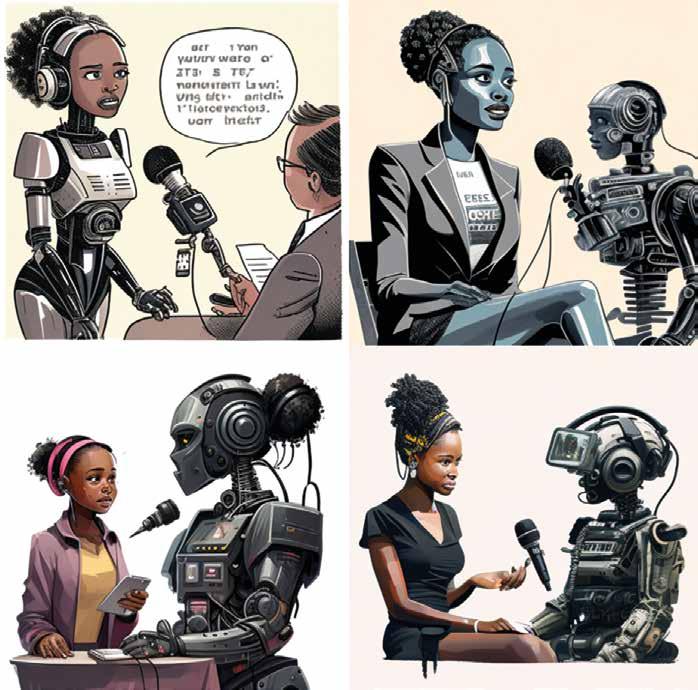

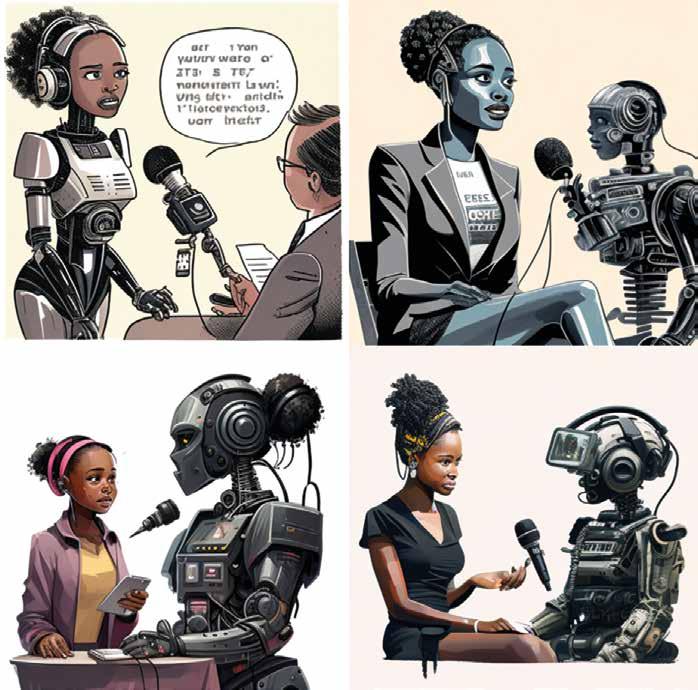

162 The dawning of a new era

DW’s path to global information provider

164 AI and I

A mash-up

FUTURE WORLD

170 Press freedom at stake in India

174 Enabling people to make free decisions

Our primary goal

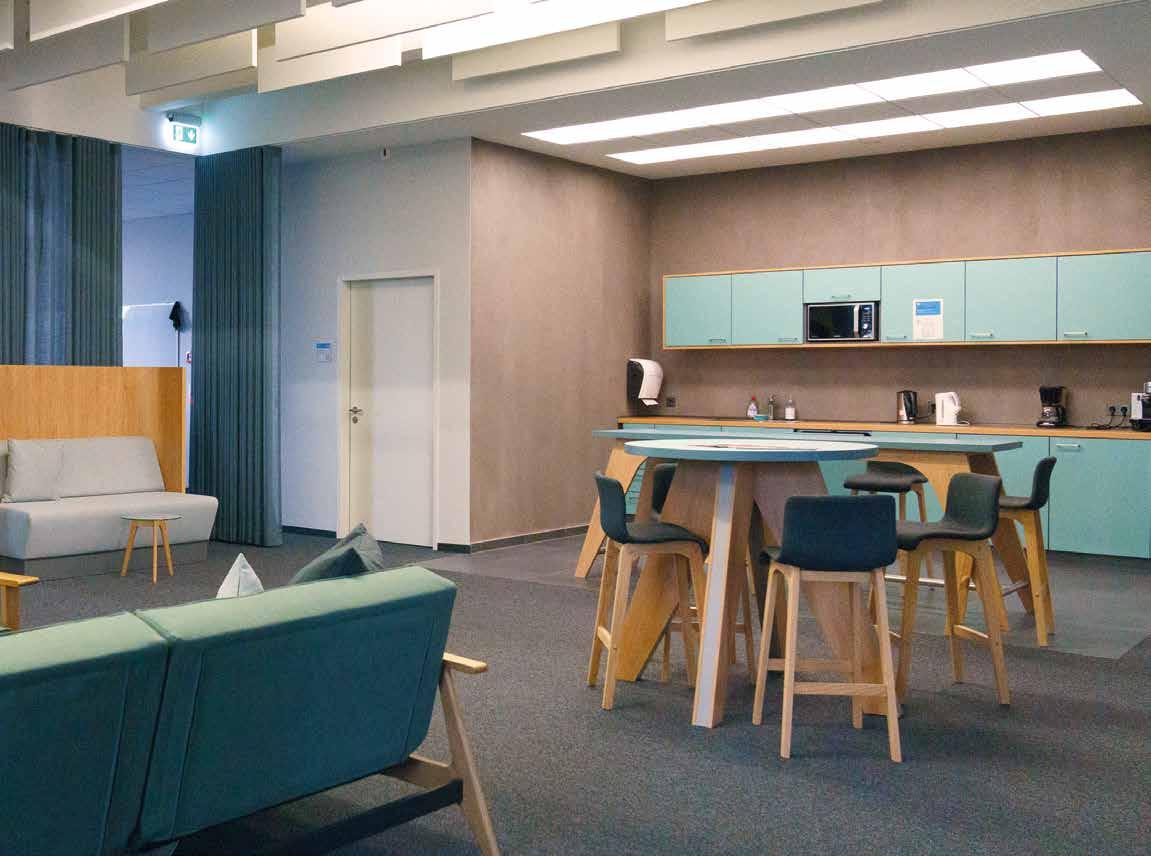

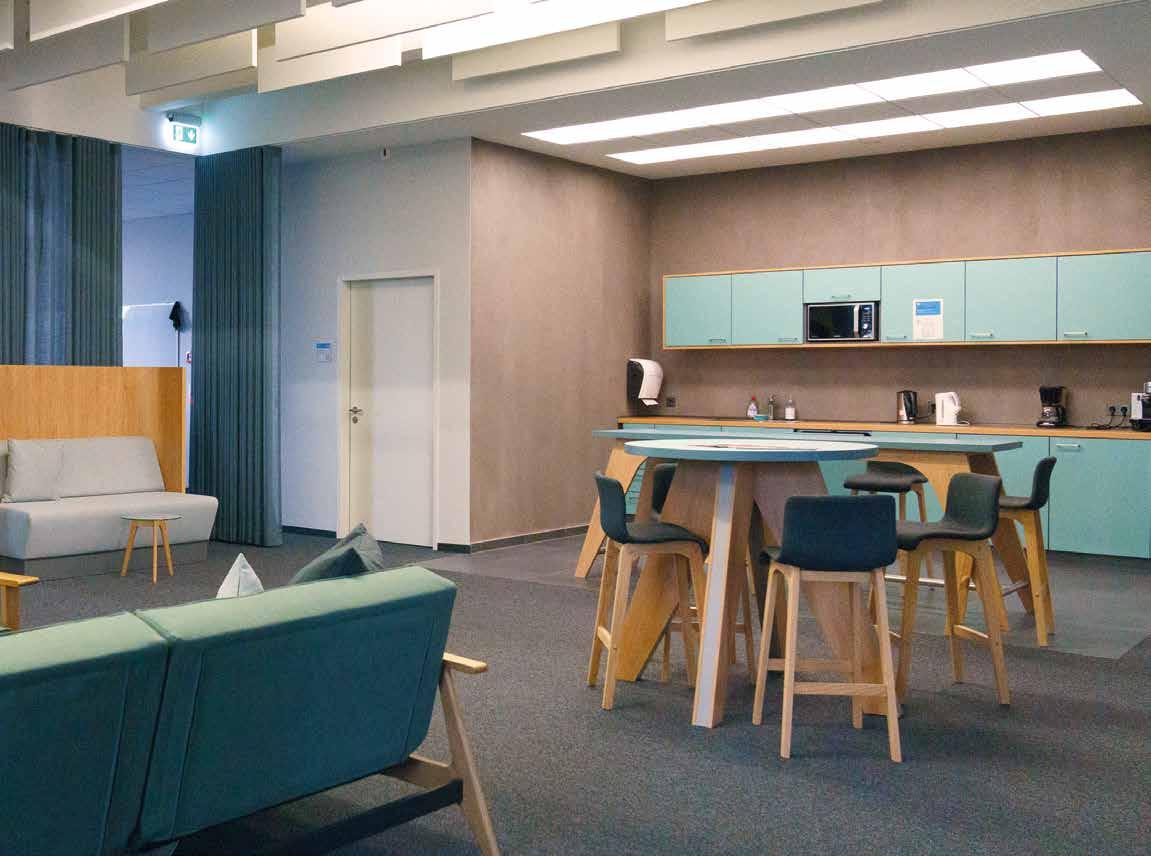

176 Is New Work the new normal?

Interview with Barbara

Massing

MIDDLE EAST

184 Reassessing the approach to Israel

MIDDLE EAST

180

On the verge of an abyss?

142 Social media vs. state propaganda

145 The power of words Using books to fight for freedom of speech

188 Managing Palestine’s looming leadership transition

192 Imprint

IMPACT 7 Weltzeit 2023

GLOBAL

May 13: Fuchsthone Orchestra

May 13: Bobby Sparks

Florian Weber & Dogma Chamber Orchestra

Thomas D & The KBCS

Sendecki & Spiegel

ENEMY – Downes/Eldh/Maddren

Thärichens Tentett

Ida Nielsen & The Funkbots

Jacob Karlzon Trio

Judith Hill

Portugal/Gramss/Muche/Negrón van Grieken

Delvon Lamarr Organ Trio

May 14: Philip Lassiter

Brad Mehldau Trio

Jakob Manz & Johanna Summer

Atom String Quartet

Julia Hülsmanns Heaven Steps To Seven

The Baylor Project

Simon Nabatov & Matthias Schubert

Simon Nabatov & Ralph Alessi

Fuchsthone Orchestra

Bobby Sparks PARANOIA

Post Koma

Philip Lassiter

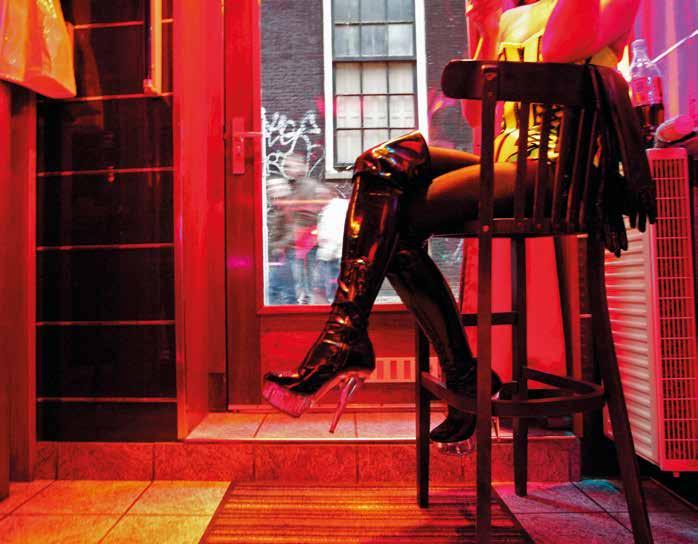

Jazzfest Bonn Extended

August 26/27 2023

THE PRINCE EXPERIENCE

Vince Mendoza & WDR Big Band

www.jazzfest-bonn.de

May 1 to 14 2023

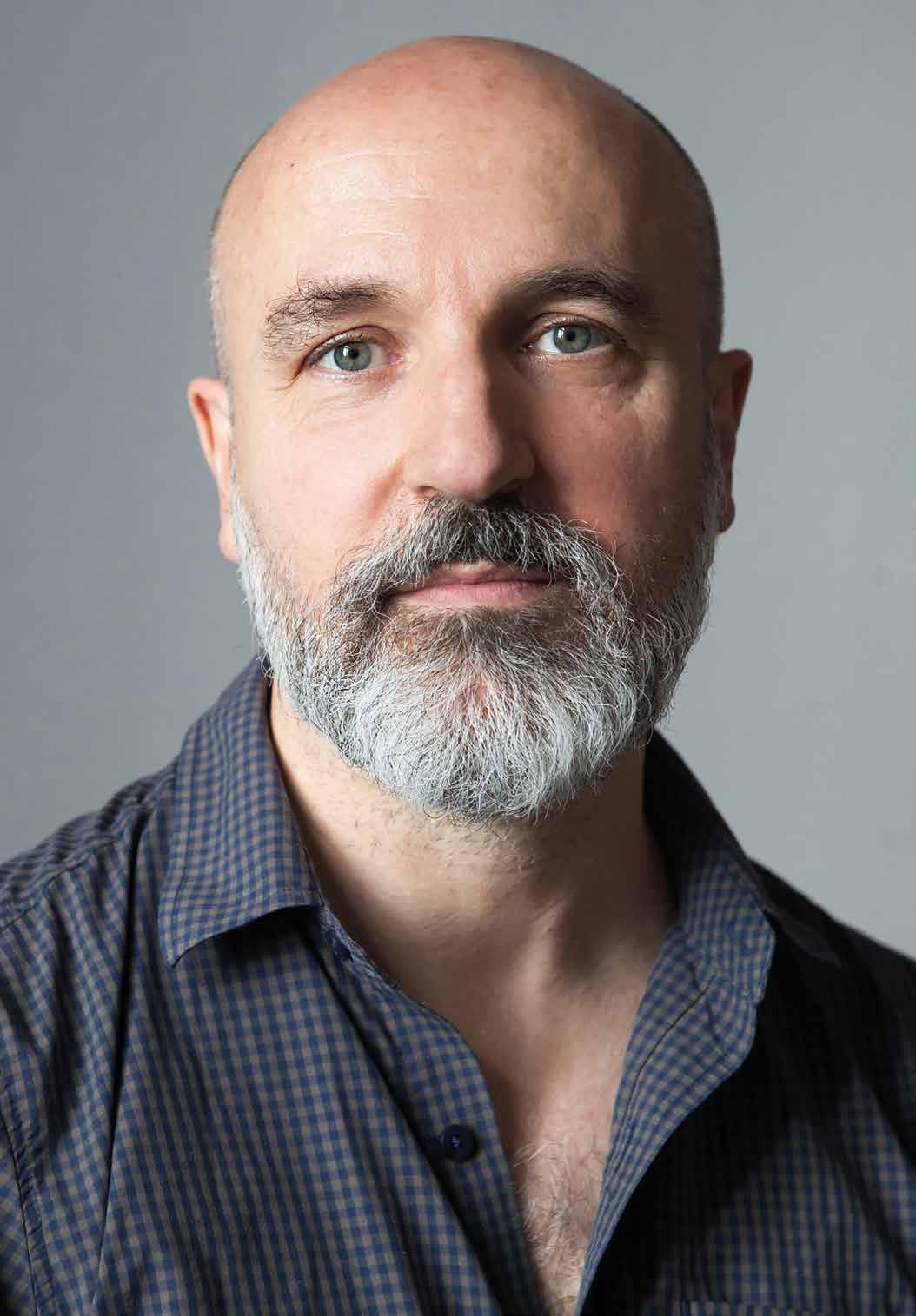

Mohamad Chreyteh

“Intense, interesting and promising,” is how Mohamad Chreyteh describes his first months at DW in retrospect. The award-winning investigative journalist and filmmaker from Lebanon has headed DW’s Beirut bureau since August 2022.

This is an exciting professional challenge for him. He is currently working with colleagues in Bonn and Berlin to expand DW’s reporting from the region. As a regional hub, Beirut will produce reports and topics for all DW language services in various formats for online, digital and TV. Chreyteh is certain, this will be “a promising concept that will give DW a greater presence in this important region of the world and bring it closer to its target groups on the ground.”

Logistically, however, it is not an easy task. “The country is suffering from one of the worst economic crises ever and is politically paralyzed. Public utilities in Lebanon are notoriously poor, the state provides barely more than 2 hours of electricity per day in many parts of the country,” he says, describing the situation. “Fortunately, DW made it possible for us to move into a well-secured and maintained building where water and electricity are available 24/7.”

In February 2023, Chreyteh covered the devastating earthquake that killed more than 50,000 people in Turkey and Syria. “It was a challenging assignment in every respect: logistically, editorially and emotionally. I didn’t expect to relive such a tragedy so soon after the huge explosion in the port of Beirut in 2020; and on a much larger scale, at that. The images of destruction, the smells, the fear and desperation of the people, all brought back many memories for me.”

© DW

9 ENCOUNTERS

DW Planet A A global look at climate issues

YouTube channel DW Planet A, launched in September 2020, addresses young users’ needs for solution-oriented reporting on climate change.

DW Analiza

Even with sometimes unwieldy topics, the social media format DW Analiza has had great success on the web: The technology duel between China and the USA, the oil price putting the alliance between the producing countries and the EU to the test, what factors will be decisive in the war in Ukraine?

The videos achieve hundreds of thousands of views on YouTube every week, high reach on Twitter and Instagram as well. And thousands of comments, through which the editorial team’s community management can enter into direct dialogue with users. The format was originally developed in the editorial department of DW’s Spanish television channel to provide more background to the news on the TV program with more up-to-date videos and with personalized explainer formats on the digital platforms.

With Planet A, DW tackles environmental issues that matter to the young target group worldwide with a twist: “We don’t want to only point fingers. Every video tries to convey possible solutions and be constructive. Climate change content can be depressing at times, and we want to break free from that,” explains Kiyo Dörrer, Supervising Editor of Planet A. “We launched Planet A because there wasn’t a lot of environmental content on YouTube that focused on the bigger picture. A lot of the videos dealt with individual solutions how to use less plastic or recycle your organic waste. But we wanted to look at

how the systems and power structures need to change for us to effectively combat climate change.”

Identifying and addressing user needs that were not sufficiently addressed before on the platform namely by creating a constructive format has been a recipe of success for Planet A. Now well into its third year, the format has gained over 400,000 followers. The most watched videos were viewed over three million times each. The team has since also launched a TikTok channel.

dwplaneta @dw_planeta

The impressive usage numbers have now brought the digital format to linear television programming as well. DW Analiza has been running on the DW Español TV channel since February 2023. “Digital first” is part of DW’s strategy to offer its users in the various target regions the programs that meet their individual information needs.

@dw_espanol dw_espanol dwespanol Watch DW Analiza on YouTube 10 DW HIGHLIGHTS

+90

Turkish-language format expands to TikTok

The social media format +90 debuted on TikTok in February, delivering distinctive output on social and regional themes whilst offering Turkishspeaking viewers a new destination to engage with constructive journalistic content.

The TikTok channel is the latest expansion of the multiplatform channel +90. Since the launch on YouTube in April 2019, the format has maintained a strong digital-only presence in Turkey, with more than 625,000 subscribers and an average of 3 million monthly views, and has since expanded to Twitter, with a follower count of 75,000, and Instagram, with 213,000.

+90 is a project developed by DW with VOA, BBC, and France 24 as part of the international broadcasters’ aim to create custom content and provide young Turkish audiences with unbiased information that promotes free speech in Turkey. While all four organizations contribute content to +90 YouTube channel, DW leads the project and oversees its programming, strategy, distribution, and marketing.

DW Managing Director of Programming Nadja Scholz: “As part of our digital first approach to commissioning, the +90 format has been a great success. Thanks to the editorial team behind the international joint venture, it is the perfect format to deliver stories that explore a wider range of opinions, allowing young audiences to evaluate diverse issues affecting the Turkish society.”

Uncovering overlooked stories in Turkey

The launch on TikTok builds on the success and global reach

of the format’s social accounts on YouTube, Instagram and Twitter and marks one of the first journalistic offerings tailored for young TikTok users in the region to provide unbiased information amid a decline in journalistic freedom in Turkey. In addition to curating content relevant to viewers in Turkey, the format will continue its mission to uncover important stories missed by local news outlets and provide value to younger and more female audiences.

Erkan Arikan, Director of Turkish Service: “The format +90 complements our offerings and enables us to further expand the ways we reach younger and especially female audiences in Turkey. We’ve seen a huge demand for factbased, unbiased journalism in the region, and our +90 team is working around the clock to provide young people with relevant stories that don’t make it into the Turkish news channels.”

Filling the gap for Turkish-focused, constructive journalism

The channel serves as an extension of DW’s editorial commitment to constructive journalism, with TikTok being an opportunity to reach the potential target groups in Turkey.

Isil Nergiz, Head of Channel +90: “We started on YouTube and expanded to Twitter, Instagram and then TikTok, motivated by the desire to go where our audience is.

Many people in Turkey use TikTok, most of whom are in the age range of our young target audience, but there is little to no journalistic content being offered to them. +90 reporting will fill the void for a Turkish-focused, independent, diverse and constructive journalism.”

Cross-platform content reach

+90 channel videos range in length from 30-second shorts to 15 minutes, allowing for more explanatory and in-depth content. Content includes interviews, reportages and explainers on key regional themes, including the

latest earthquakes in Turkey, the collapse of the Turkish lira, being a young Jew in Istanbul and stories of sexual abuse survivors.

Some of the format’s top videos to date on Instagram include Earthquake from a construction worker’s perspective, with more than 9.9 million views. On YouTube, Scorpion venom fetching 10 million dollar a liter reached over 3.6 million views. On Twitter, the video Being a young Armenian in Turkey has been viewed 1.5 million times and garnered over 5,000 likes.

plus90 @plus90 11 Weltzeit 2023

@plus90_official

Nous, les 77 pour cent French edition launched

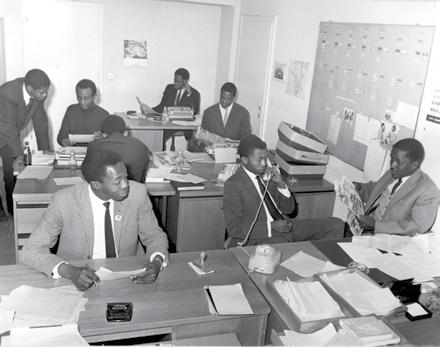

On the beach at Cotonou: Kamal Radji listens attentively to the young woman telling him how she became a victim of cyberbullying. The influencer is in Benin’s economic hub hosting a street debate for youth magazine 77 percent, now in French on DW. Majoie Houndji talks about how she was bullied first in school, then on Facebook because some of those around her thought her breasts were too small.

“A former friend wrote a post to my Facebook page and inside of a week I had 60,000 followers… but they weren’t standing by me, they were coming after me.” She recounts how she began hurting herself so she would not feel the pain of the insults and didn’t know which way to turn. “Then one day it occurred to me: This is about my life!” So, she filed a lawsuit against the offenders.

Majoie Houndji went on to start a club for people against

cyberbullying who also support the victims.

Cyberbullying, professional perspectives, participation in politics and civil society, love, migration, innovation, taboos the new French-language magazine, dubbed “77 pour cent nous, les jeunes d’Afrique” deals with all these topics in the form of reports, interviews or discussions.

The magazine’s name comes from a statistic by the World Bank showing that 77 percent of Africans are younger than 35. This majority does not have much of a voice, so DW gave them one in 2017, by launching the 77 percent format: radio reports and videos on demand (VoD) now in six languages, including French, as well as English, Portuguese and Hausa.

“I am so happy that we are producing a program for a young francophone audience,”

says Fréjus Quenum, Co-Head of French for Africa. “77 percent is a program that combines entertainment with education. We are not afraid to touch on difficult topics but we make sure that we do not destroy the innovative capability of the young people. The show is structured to be a source of motivation for young Africans.”

“77 percent is hitting the mark and the young people seem to trust the DW brand and are showing how much they love discussing issues,” says Claus Stäcker, Director of Programs for Africa. “TV in Africa is still growing, but as internet prices continue to drop, more and more young people are watching our video-ondemand content on their cellphones, tablets or laptops.”

dw.com/fr dw77pourcent

nous,

jeunes

Text Dirke Köpp, DW French for Africa

Watch 77 pour cent

les

d’Afrique

12 DW HIGHLIGHTS

© Johan von Mirbach / DW

© DW

..

has been fighting against ruler Alexander Lukashenko from exile since 2020. For several months Turkish journalist Can Dündar traveled with her to Vilnius, Vienna, Aachen and Berlin.

DW Director General Peter Limbourg said at the premiere: “Most people in the West do not know what it is like to live in exile, not to be able to return to their homeland. That is why our film with Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya and Can Dündar is so important. It also draws attention to the ongoing courageous struggle of the people in Belarus.”

Following the film screening, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya said that everybody who lives in Belarus is in constant danger of “being arrested, kidnapped, put in prison.”

“My husband is on trial again in Belarus. We all know it’s a farce, an attempt to put pressure on him to break. But my husband, like all the other political prisoners, is unbreakable,” Tsikhanouskaya said. The more than 1,000 prisoners “know that the Belarusian people continue to fight for them. They believe in us, in the international community and that together we will be able, through pressure, through sanctions, through

negotiations, to find mechanisms to release our beloved and to free our country from dictatorship.”

In the Guardians of Truth series, Can Dündar, former editor-in-chief of the Turkish daily Cumhuriyet, who was imprisoned in 2015 for his research into Turkey’s arms supplies to Syria, meets exiled journalists, politicians and dissidents around the world. He talks to them about the fate he

himself shares with them. Dündar’s films show impressive biographies of people who fearlessly stand up for freedom of expression. Guardians of Truth Part 1 followed Mexican investigative journalist Anabel Hernández, who has been living in exile in Italy since 2017. Her work focuses on corruption and the collusion between Mexican government officials and the drug cartels. Hernández became the fifth recipient of the DW Freedom of Speech Award in 2019.

Can Dündar: “We live in a time when freedom is threatened in many places in the world. Fortunately, there are also courageous people everywhere who defend this freedom. It is a privilege that we can meet them in this film series.”

Can Dündar and Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

In 2015, the Turkish journalist Can Dündar exposed illegal arms deliveries from Turkey to Syria, was called a terrorist by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and fled to Germany after an attack was made on him during his trial. Since then, he has campaigned for freedom of expression worldwide.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya is an “involuntary” opposition leader. In 2020, her husband Sergei stood in the Belarusian presidential elections against long-time ruler Alexander Lukashenko, but was detained before election day and later sentenced to 18 years in a prison camp. Tsikhanouskaya briefly took over her husband’s candidacy, but left the country with her two children shortly afterwards for security reasons and has since been living in exile in Lithuania. She called for peaceful protests against ruler Lukashenko and is campaigning for the release of political prisoners.

In the 2022 Press Freedom Index of Reporters Without Borders, Belarus ranks 153rd out of 180 countries.

dwdocumentary

A film by LINDA VIERECKE and CAN DÜNDAR

Camera AXEL WARNSTEDT and NEVEN HILLEBRANDS / Editing KIRSTEN JUNGCLAUS / Music and Composition JÖRG SEIBOLD

Re-Recording Mixer TIM TABELLION / Color Grading ROBERT FIEDLER / Research DEMID SHERONKIN

Managing Producer GESINE KRÜGER / English Version MEREDITH JONES / Commissioning Editor HANS CHRISTIAN OSTERMANN Executive Producers TIM KLIMEŠ and ROLF RISCHE

A film by LINDA VIERECKE and CAN DÜNDAR

Camera AXEL WARNSTEDT and NEVEN HILLEBRANDS / Editing KIRSTEN JUNGCLAUS / Music and Composition JÖRG SEIBOLD

Re-Recording Mixer TIM TABELLION / Color Grading ROBERT FIEDLER / Research DEMID SHERONKIN

Managing Producer GESINE KRÜGER / English Version MEREDITH JONES / Commissioning Editor HANS CHRISTIAN OSTERMANN Executive Producers TIM KLIMEŠ and ROLF RISCHE

Can Dundar meets Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya Watch Guardians of Truth Part 2 on YouTube

13 Weltzeit 2023

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya and Peter Limbourg

© Florian Huber / DW

The CampusProject 2023

Afghanistan and Iran Text Anastassia Boutsko, DW Culture 14 DW HIGHLIGHTS

For over 20 years, the Beethovenfest Bonn and DW have been organizing the joint Campus-Project a cultural performing platform for young musicians from around the world.

This year, the focus is on two countries in which women in particular are struggling for their right to social participation and (cultural) self-determination: Afghanistan and Iran. The first stop is the Portuguese city of Braga, where young Afghan musicians have currently found refuge from the Taliban.

Marin, Shabana and Baset are members of the Afghan National Youth Orchestra. In August 2021, the lives of these young people changed abruptly after the Taliban took over power in Kabul. The young musicians’ “alma mater”, the Afghan National Institute of Music (ANIM), became one of the first targets of the new regime: classrooms were vandalized, musical instruments destroyed.

“My mother said to me: you must also destroy your instrument, the sitar, or at least hide it well,” Shabana recalls. “So me and my brother, who is also a musician, wrapped our instruments in blankets and hid them in the laundry.” In the months that followed, Shabana was only rarely allowed to leave the house: “My mother was afraid that I could be picked up by Taliban and forcibly married.” Her fellow music student Marin also recounts similar experiences, “Life changed abruptly. It was a nightmare.”

A new life began for Marin, Shabana, Baset, and nearly fifty other young Afghans a few months later when Portugal, on behalf of the European Union, made the decision to offer refuge to young musicians from the Taliban-occupied country.

Braga, a beautiful small city near Porto in northern Portugal, is hosting the members of the Afghan youth orchestra. “Here our young musicians have the opportunity to go to appropriate schools, but most importantly to continue their musical education at one of the best conservatories in Europe,” says Ahmad Sarmast, founder and director of ANIM with visible pride. “I am sure that the barbaric rule of the Taliban will not last forever,” Sarmast says. “And then we will return to Afghanistan with a team of young musicians who are among the world’s elite.”

For the Campus-Project the musicians from Afghanistan will perform a concert at the Beethoven Festival in Bonn in September together with their young colleagues from the National Youth Orchestra of Germany (Bundesjugendorchester).

Cymin Samawatie has taken on the task of musical director of the project. Born and raised in Germany as the daughter of parents who fled Iran, Samawatie knows about the structural and cultural problems and reservations.

The composer, conductor and singer lives in Berlin and, with patience and perseverance, has established herself as a pioneer of a new transtraditional music that artistically unites musicians from different cultural backgrounds.

“I am thrilled by the creativity of young Afghan musicians and their openness and I look forward to working with them,” Samawatie says. On the artistic vision of the project, she explains, “The poetic word, a central element of Afghan culture, and in both major national languages, Pashto and Dari, will play a central role. Namely, the poetry of women.”

“Art and culture, especially music, are subject to considerable restrictions in Afghanistan and are partly forbidden, for Afghan musicians it is therefore hardly possible to develop,” says DW’s Head of the Afghanistan Service, Waslat Hasrat-Nazimi. “We often hear about violence against Afghan artists or even against people who listen to music. For this reason, it is important to us to support the project with our coverage.”

As in previous years, all activities of the project will be accompanied by the media and language channels of DW. The Afghanistan-Iran Campus marks the 21st round of this unique and successful international project.

dw.com/culture beethovenfest.de/ campus-projekt

I am sure that the barbaric rule of the Taliban will not last forever and then we will return to Afghanistan with a team of young musicians who are among the world’s elite.

© DW

15 Weltzeit 2023

(left to right): Head of project, Thomas Scheider (Beethovenfest), Anastassia Boutsko (DW Culture), Director of ANIM, Ahmad Sarmast, Zamzama Niazai and Nazenin Wali (DW Dari and Pashto Service)

¡Venceremos!

Latin America is back on the world stage. After long years of neglect, Europe and the US have rediscovered their interest in the region. Against the backdrop of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, the subcontinent has become more important not only because of its fossil raw materials and its great potential for producing green energy, but also geopolitically: Not least at the United Nations, every vote against Russia counts

But Latin America’s traditional ties with Europe are by no means self-evident. While Europe and even the US are still held in high regard by the people in the region, their governments have long been courted by Russia and China, and competition has widened the scope for negotiation.

About a dozen Latin American countries have signed a memorandum of understanding to join China’s Silk Road Initiative, China is building ports and railroads, buying mines and concession rights, and recently trumped Germany and others in the race to mine lithium in

Bolivia. Russia, on the other hand, is not only economically engaged and thus vital to the survival of its traditional allies in the dictatorships of Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela, but also relies on soft power: The Kremlin invests in cultural exchange, scientific relations, and uses them for its propaganda, for which historically based anti-American resentments provide fertile ground.

Europe is in a competition that is about more than raw material supplies and trade relations. In addition to historical and cultural proximity, in recent decades after most Latin American dictatorships were overcome the two continents have been linked by shared democratic values. What has been lost sight of in the process is the fact that for most people in Latin America, the idea of Western democracy is linked not only to political but also to economic participation. However, neither the overthrow of dictators nor vibrant economic relations with the global West have helped to combat the glaring social inequality.

Latin America with new self-confidence

Text Uta Thofern, Director, Programs for Latin America

16 LATIN AMERICA

© Pablo Cozzaglio / AFP via Getty Images

The Uyuni Salt Flat, Bolivia. South America controls about 70 % of the world’s reserves of lithium.

17 Weltzeit 2023

The hope for greater social justice that was associated with democracy has been dashed again and again in Latin America. And yet it has just experienced a renaissance: In Colombia, the reformed former guerrilla Gustavo Petro was elected as the first left-wing president in history; in Brazil, the social democrat Lula da Silva replaced the unsavory rightwing populist Jair Bolsonaro; in Chile, Gabriel Boric, a former student leader who was elected to office after a wave of social protests, has been in power for a year. The expectations of the poor, the marginalized and the disadvantaged now rest on them. The three presidents must deliver. However, none of them has a stable majority of their own in parliament, and they will have to make far-reaching compromises. To what extent they will actually succeed in achieving a more social economy and society is an open question.

The risk of failure is immense in Latin America. Many of the reasons lie in the constitutions, which are often described as poor copies of the US Constitution. Directly elected heads of state without a parliamentary majority are predestined to disappoint their voters; at the same time, they are more easily tempted to rule through their access to the military. The frequent ban on re-election, which is actually an attempt to limit power, fuels corruption and bad governance. At the same time, the separation of powers functions inadequately in many places, and the legal system is perceived as corrupt.

Social inequality still partly reflects structures of the colonial era: A racist class society that feels no obligation to the indigenous population and the descendants of slaves. On the one hand, precarious living conditions and a lack of education increase the manipulability of these voter groups and can sweep populists to power; on the other hand, they

make it more difficult for new democratic forces to emerge. In addition, the specter of communism is very much alive in Latin America. The road to the abyss taken by Venezuela following the election of a socialist tribune of the people means that even justified social demands are often perceived as subversive by the old elites. Peru, which has worn out five presidents in the last five years, exemplifies political polarization, social division and the resulting alienation from the existing democratic system.

In addition to political reforms, steps toward a fairer economic system are urgently needed if the countries of Latin America are to take their rightful place on the world

stage in the long term. To achieve this, old mistakes must not be repeated. During the last commodity boom, no Latin American country managed to develop a self-sustaining economic model. Both Lula in Brazil, who was already once in power at the time, and his socialist colleagues Evo Morales in Bolivia and Rafael Correa in Ecuador largely confined themselves to redistributing the profits from the exploitation of natural resources through social programs, not to mention Hugo Chávez and his successor Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela. Europe profited from this and has become an accomplice in this development.

For a successful new start in relations, Europeans must

© picture alliance / dpa / Cerrejon

18 LATIN AMERICA

View of the Cerrejon mine in Colombia.

not only insist that social and environmental standards be observed in economic cooperation always with the risk that competition from China or Russia will demand less while offering faster profits. Europe must also provide a technology transfer that enables partners to create more value in their own countries. The first steps have already been taken. For example, while Germany initially seeks to import more coal from Colombia in light of the current energy shortage, it also aims at supporting the country in building a green hydrogen industry. In order to finally adopt the free trade agreement between the EU and the South American Mercosur states, similar thinking is needed.

Politically, Europe must accept that no allegiance can be expected from Latin America. The egoistic vaccine policy of the Corona years has cost the EU credibility and reinforced the trend towards diversification of foreign relations in Latin America. The fact that countries like Mexico and Brazil refused to take a clear position on the war in Ukraine and instead presented their own negotiating concepts is not only an expression of traditional neutrality, but also of a new self-confidence. The European Union is no longer automatically regarded as a model of success. Supporting political and economic reforms in Latin America for sustainable mutual benefit will be a balancing act.

Against the backdrop of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, the subcontinent has become more important not only because of its fossil raw materials and its great potential for producing green energy, but also geopolitically.

A child playing basketball in the 23 de Enero neighborhood.

19 Weltzeit 2023

© picture alliance / dpa / Pedro Rances Mattey

Media in Mexico: The corrosive power of violence

The first report of the murder of a journalist in Mexico dates from 1860. On November 25, Vicente Segura Argüelles, co-founder of the satirical newspaper Don Simplicio, editor of two other newspapers and a representative of politically conservative journalism, was shot dead by troops of the liberal government in Mexico City.

These were the years of the so-called “War of Reforms,” a civil war in which two parallel governments, one liberal, the other conservative, faced each other irreconcilably for three years.

A little over half a century later, a new peak was reached when in 1912, under the presidency of Francisco I. Madero, and in 1913, under Victoriano Huerta Ortega, the number of murdered journalists rose to five each year. These were the last days of the Mexican Revolution.

Seven decades later, in 1986, the deaths of 12 journalists were recorded under the government of Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado. The death toll rises steadily, ranging from 26 to 32 journalists killed during the six-year terms of Miguel de la Madrid, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, Ernesto Zedillo, and Vicente Fox Quesada.

Violence against journalists in Mexico skyrocketed under Felipe Calderón Hinojosa, under whose administration the country saw 113 murdered journalists. The number then dropped to 83 during Peña Nieto’s six-year term, and 42 journalists have been killed so far during the term of current President Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

Murders are just the tip of the iceberg

Mexico is setting a sad record internationally. According to several organizations,

Mexico, the most dangerous country for journalists

Murders each year Source: UNESCO 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 80 99 55 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 World Mexico 90 57 62 99 116 102 Syria Afghanistan Iraq

20 LATIN AMERICA

Text Claudia Herrera Pahl, Head of Spanish Online

including Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Mexico is the deadliest country in the Americas for journalists and the second deadliest in the world.

But it’s not just murders. The listing of the dead certainly marks an end point, but it is only the tip of the iceberg that hides a much larger number of assaults on the press as a whole. According to the international human rights organization Article 19, in June 2022 there was an attack on journalists or media outlets in Mexico every 14 hours. According to the same source, most attacks on journalists in Mexico come from state agencies or local authorities.

In a recent act of violence, prominent journalist Ciro Gómez Leyva was shot at by unknown assailants on a motorcycle while riding in an armored car in Mexico City on December 15, 2022. He was unharmed. His armored car saved him from three targeted shots.

“We know that we are doing journalism in a violent and dangerous country and that we are exposed to risks,” says Ciro Gómez, who points out, however, that nothing comparable has occurred in the Mexican capital since the mid-1980s. The violence, he says, is concentrated in the provinces and is directed against local journalists from smaller media outlets, but seldom against the more renowned journalists working for Mexico’s largest media outlets.

So, was it a targeted attack on the journalist, or was it just an ordinary assault in a country rife with violence, where more than 30,000 murders were recorded in 2022 and more than 100,000 people disappeared without a trace? Ciro Gómez doesn’t want to jump to conclusions: “There is no certainty, only uncertainty”.

Violence is an everyday occurrence

In today’s Mexico, where people are dying seemingly indiscriminately, the effects

will be felt for generations to come. “The spiral of violence is so massive that the media now treat this news as routine, so ultimately the violence has become normal, which prevents the population from becoming outraged and generating a civil society response,” says Mexican investigative journalist Anabel Hernández.

“This apathy, this indifference of citizens to the suffering of others, increases the scope for impunity and leads to more violence against

everyone, including journalists,” Hernández says. “This violence, this taming and subjugation of a people at gunpoint, whether by the narcos or by the army and police, makes a country kneel not only before crime but also before authoritarianism. This life on its knees will have consequences for generations,” analyzes Hernández. “We are facing a threat to democracy and the social and civic constitution of a country that for many decades has been an example of social struggle and dignity.”

A journalist holds a picture of her murdered colleague during a protest.

Most attacks on journalists come from state agencies or local authorities.

©

21 Weltzeit 2023

picture alliance / AA/Daniel Cardenas

22 LATIN AMERICA

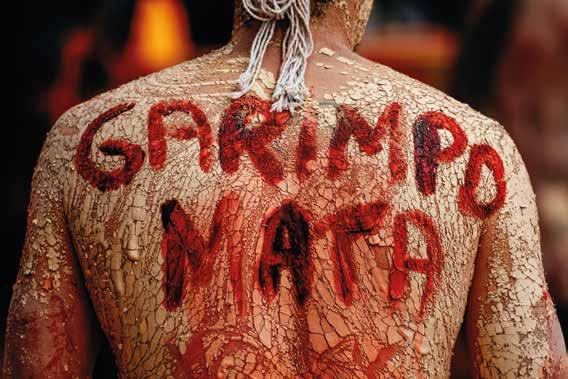

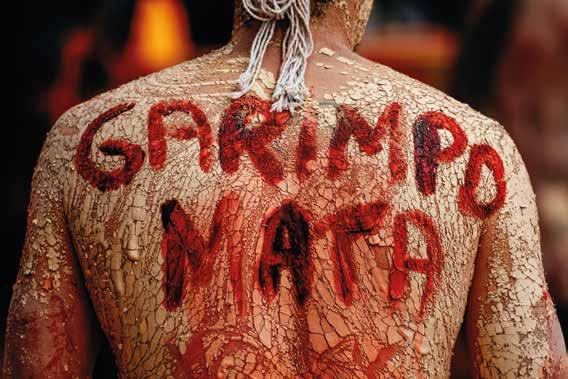

Environmental journalism in Brazil remains dangerous

Brazil is one of the most dangerous countries for conservationists. According to a 2022 report by the nongovernmental organization Global Witness, one in five murders of environmentalists occurred in Brazil over the past decade. The vast majority of the murders occurred in the Amazon. Most of the victims were indigenous people.

Those who want to tell the story of these people are also in danger. The non-governmental organization Reporters Without Borders lists the

Amazon rainforest as one of the most dangerous regions for environmental journalism in its press freedom ranking.

DW reporter Nádia Pontes knows this all too well. Attempts to intimidate her are routine in the numerous environmental reports she has written for DW’s Brazilian service in recent years. She experienced the most dangerous situation of her career during an operation by the Brazilian environmental agency Ibama against illegal gold miners in Kaypa Indian Territory. The helicopter in which she was accompanying Ibama’s agents was fired upon with heavy gunfire.

Fortunately, no one was injured. “On the same mission, we had to leave a guesthouse in the early morning hours. I was working on the computer when I heard the receptionist giving information about our team to someone on the phone. To avoid an ambush, we quickly left the place.”

Environmental journalism in Brazil is dangerous because it works with superlatives. The first of these is the economic component: Indigenous and conservation areas in the region bordering Peru, Colombia and Venezuela are threatened by illegal logging, mining and the transnational drug trade that uses the

Text Francis Franca, Head of DW Brazilian Service

Weltzeit 2023 23

An indigneous man with “Mining Kills” painted on his back.

© picture alliance / ASSOCIATED PRESS / Eraldo Peres

region’s rivers to bring cocaine to ports and ultimately to the European market. Journalists who report on the damage these activities cause to biodiversity and indigenous populations stand in the way of the interests of criminal organizations that move billions of euros each year.

However, the exorbitant sums earned from environmental destruction are tiny when compared to the importance that an intact forest has for the planet. With its “flying rivers,” the immense amount of rain that the rainforest produces, the Amazon regulates precipitation throughout South America and stabilizes the world’s climate.

To preserve the forest despite the greed of organized crime, another superlative must be managed: the area to be protected. Brazilian authorities must control an area in the Amazon that is larger than all

the countries of the European Union combined and that’s not even taking into account other important ecosystems such as the Cerrado and the Atlantic Rainforest. Many regions are difficult to access and can only be reached after hours of travel by boat or by plane. These are regions that the state does not penetrate. And thus they become lawless areas.

In one of these regions, the Javari Valley, the British journalist Dom Philips and the indigenous expert Bruno Pereira were murdered in 2022. The case attracted international attention and revealed again the violence that Global Witness had already noted in its report on the murders of environmentalists.

Pereira was a frequent source for DW reports on violence against indigenous peoples as an employee of the Funai indigenous agency.

We live in terror in the Amazon.

© picture alliance / ASSOCIATED PRESS / Lucas Dumphreys

24 LATIN AMERICA

Men search for gold at an illegal mine in the Amazon jungle.

He always asked not to be named because he was subject to death threats. “We live in terror in the Amazon,” he told reporter Nádia Pontes in 2020, referring to his work during the government of Jair Bolsonaro, under which structures to control and fight environmental crimes in Brazil had been dismantled, encouraging the practice of illegal activities on indigenous lands and in protected areas. While environmental authorities were weakened and given fewer resources and personnel, organized crime in the Amazon reached unprecedented levels of complexity.

The most dramatic consequence of these policies was the famine of the indigenous Yanomami people, which made headlines around the world in January 2023 when newly elected President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva visited Yanomami land. Images of malnourished women and children shocked the world. Close to 600 Yanomami children have died of malnutrition in the last four years. The crisis was triggered by illegal gold miners who destroyed the forest, contaminated rivers with mercury and spread disease.

The new government is at least showing interest in protecting the Amazon. Regulators are being rearmed to fight environmental crimes and drive out invaders. But environmental protection and environmental journalism remain dangerous even under Lula da Silva. For example, the base that Ibama and the federal police set up to evict gold miners and regain control of Yanomami land was attacked by gunmen a few weeks later.

Despite the risk, Nádia Pontes says she is not afraid: “For my research, I spend a certain amount of time in these places and then return home. The greatest danger is borne by the environmentalists who stay in the area, continue to give tips to the authorities and thus become the target of criminal organizations.”

© Michael Dantas / AFP via Getty Images

© Nádia Pontes

Aerial view of an illegal logging operation in Humaitá, Brazil.

© Michael Dantas / AFP via Getty Images

© Nádia Pontes

Aerial view of an illegal logging operation in Humaitá, Brazil.

25 Weltzeit 2023

Nádia Pontes covers environmental issues for DW in Brazil.

© Contributor / Getty Images 26 RUSSIA

What do Russians think?

DW’s Konstantin Eggert

with Natalia Zubarevich, a Russian specialist in socio-economic development.

Interview Konstantin Eggert, DW Editor

How has the war in Ukraine affected the life of Russians so far?

If we take the large urban population, the first factor is those who left. Figures vary, but cumulatively from spring to fall at least 300,000 people left the country. This is a substantial loss of human capital.

While the Russian population is used to losing income, we are still at the level of income of around 2012. Ten years down the drain. The minimum wage was raised by 10 % while the cost of living increased by 10 %, which means that more people will be able to claim social assistance. In this crisis, the biggest blow came to the educated, urban, professional population. No one is going to help them in any way.

Do you think the Russian authorities have a strategy to deal with the declining workforce in industries like high tech?

I don’t have an answer to your question, because the policy of the authorities is incredibly contradictory. But the fact is that we want to bring back those who are needed, yes. And for the rest, well, the attitude is “go to hell”.

Russia’s economy is beginning to feel the weight of Western sanctions, following the start of the war against Ukraine.

spoke

27 Weltzeit 2023

In Russia, payments for those killed in war are like anesthesia.

Though several hundred-thousand men were drafted, one can’t see much discontent. Was there no real effect of the mobilization at all?

Initially, it was very hard on the labor market, because it was mainly bluecollar workers who were drafted. And we have industries in which the workforce is predominantly male. This is the agricultural sector, construction, transportation, manufacturing. There are staffing problems there, there is no one to replace these people. There are already issues in construction, it is also difficult to find workers for the defense industry. The logic for many who were drafted is simple: they did not earn much and were promised much more. That is why families, already burdened with loans, said, “at least something will be earned, it will be easier.” People are poor. 12 % of the population lives below the very modest Russian subsistence level. And another 13 % just above that level. The money they were promised looks fantastic. People are strapped with credit, living from paycheck to paycheck.

But they don’t just go there to die, they go to kill.

A large part of the Russian population is quite satisfied with the propaganda they receive from Russian television. Poor people, as a rule, live for today. This is Russia’s misfortune, this is Russia’s problem. But you can’t accuse these people of anything. They are surviving. People have three choices. The first is obedience. They went where they were told. This is the reaction of the majority. The second is protest. And there are fewer and fewer of these reckless people, because there are risks and consequences. And the third is avoidance. The urban population chose avoidance and left the state. And the bulk of the population, not having the resources, nor an understanding of the situation, chose obedience and went where the state told them to go.

Is there some level of sacrifice at which people will begin to worry? When might the mood change, even in this poor, docile Russia?

I’m not a sociologist, but I’m well aware that quite generous payments for the dead and wounded calm the families down. Huge benefits for their children to get into higher education are also a

Natalia Zubarevich

bonus. And people are told that their children died for their homeland. All this together so far works as an anesthesia for a large part of the population.

What will regional authorities do when they begin to realize that they have a real shortage of personnel, that taxes are falling? Will they go to Moscow and ask for more oil money?

So far, problems are piling up, first of all, in the federal budget. But the federal budget has money to draw from. 2022 was a special year. From January to May 2022, the Russian federal budget received 2.6 times more oil and gas revenues than the year before. In October, we exported and produced more than a year ago. All of this provided a huge cash cushion for the federal budget. Clearly, this can’t go on forever. 2023 will realistically be a much more problematic year for the federal budget. Legislation has been passed to raise taxes and duties on all export industries. We have already unlocked the National Welfare Fund. The next step is domestic borrowing.

In the case of a new mobilization, are some segments of the population still economically able to emigrate, or are they already exhausted?

Why declare a new mobilization when you can quietly pull out the people you need according to their military professions? Quietly, gently, little by little. The authorities are getting smarter too.

is a Russian economistgeographer specializing on the socio-economic development of the regions. She has been the professor of the Department of Economic And Social Geography of Russia of the Moscow State University since 2005.

28 RUSSIA

A large part of the Russian population is quite satisfied with the propaganda.

Delivering justice for the war crimes in Ukraine

Russia’s war against Ukraine has shattered millions of lives, wrecked Ukraine’s civilian infrastructure, and brought Europe back to the days of trench warfare and major battles not seen on the continent since World War II. Russia launched its full-scale invasion having already breached Ukraine sovereignty in occupying Crimea in 2014 and operating pro-Kremlin armed groups in eastern Ukraine. That the international community finally issued a firm response to the mounting atrocities that unfolded in Ukraine after the escalation is a positive precedent, paving a path to justice.

The question is whether we can make sure this will make a difference?

As part of the response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, multilateral organizations and many Western governments swiftly and

exceptionally engaged a range of accountability mechanisms and tools, underscoring the importance of criminal justice for serious crimes committed there.

On March 2, 2022, the International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor opened an investigation into alleged serious crimes in Ukraine following a request by an unprecedent number of ICC member countries. Judicial officials in several countries have also opened criminal investigations using their national laws to examine serious crimes committed in Ukraine. On March 4, the United Nations Human Rights Council established an Independent International Commission of Inquiry to collect, analyze and consolidate evidence of violations, identifying those responsible where possible with a view to ensuring accountability.

Text Tirana Hassan

The human cost of the war in Ukraine has been catastrophic.

29 Weltzeit 2023

© picture alliance / ASSOCIATED PRESS / Rodrigo Abd

Ukrainian authorities are also conducting their own criminal investigations. To support these efforts, many governments have offered Ukraine evidentiary, technical, and operational assistance to bolster its judicial capacity.

Meanwhile, journalists have been reporting on the war in Ukraine, showing the immense civilian suffering and the gratuitous cruelty of Russian forces. Ukrainian and international non-governmental organizations, including Human Rights Watch, have also been documenting abuses as they occur with a view to helping inform and in some cases support the accountability efforts to ensure justice for the crimes being committed in Ukraine.

From the earliest days of the full-scale invasion, Russian forces have showed unconscionable disregard for civilian life. They pummeled densely populated cities. They killed or injured hundreds of civilians in Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, in the first 11 days of the invasion alone, indiscriminately bombing and shelling heavily populated areas with cluster munitions and explosive weapons with wide-area effect. They laid siege to Mariupol, turning this port city into a veritable hellscape.

A number of Russia’s violations have been emblematic of the conflict. Among them is the widespread and repeated targeting of Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, which Human Rights Watch and other groups documented.

This tactic, apparently designed to instill terror among civilians in violation of the laws of war, has deprived millions of Ukrainians of regular access to electricity, water and heat in the dead of winter – cruelty that Russian policymakers and state media commentators applauded.

Russian attacks have also led to heavy civilian casualties. One such strike was the April 8 cluster munition attack on the Kramatorsk train station, a

major evacuation hub for civilians fleeing the fighting in eastern Ukraine, killing at least 58 civilians and injuring more than 100 others. A 10-month intensive investigation led Human Rights Watch to conclude that Russia launched this attack with disregard for the lives of the hundreds of civilians at the station that morning, making it an apparent war crime.

Another high-civilian casualty Russian attack, and one that should be investigated by judicial officials as a potential war crime, was the June 27 missile strike that hit a busy shopping center in Kremenchuk, in central Ukraine, killing at least 21 people and wounding dozens of others. Human Rights Watch, in an intensive investigation found no evidence of military targets in the vicinity, contrary to the Russian government’s claims

Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Britain’s Karim Khan (3rd L), visits a mass grave in Bucha, on the outskirts of Kyiv.

Russian forces have showed unconscionable disregard for civilian life.

30 UKRAINE

© Fadel Senna / AFP

that the Ukrainian government stored weapons in the adjacent industrial complex and that the mall was empty.

Media and human rights groups, including Human Rights Watch, have also documented Russian forces’ summary executions and other killings of dozens of civilians, conflict-related sexual violence, enforced disappearances, and torture all war crimes in areas Russian-occupied areas. The city of Bucha, in Kyivska region, has become a symbol for Russian forces’ atrocities as an occupier, but evidence of the same types of abuses is plentiful elsewhere.

In Izium, which Russian forces occupied for six months, almost all of more than 100 people Human Rights Watch interviewed said that they had a family member or friend who had been tortured. In Kherson region, researchers came across at least 52 cases in which Russian occupation forces either forcibly disappeared civilians or otherwise held them arbitrarily, many of whom were tortured.

Russia’s response to all allegations of abuse is a predictable wall of lies and denial. In some cases, though, comments by officials help implicate Russia in potential war crimes.

One example concerns Russia’s forcible transfer, or deportation to Russia or occupied territories, of Ukrainian children displaced by the war, a war crime. Much of what we know about this comes from top Russian officials, including President Vladimir Putin’s children’s rights commissioner and others who have staged photo-ops with these Ukrainian children.

Russia’s efforts to destroy Ukrainian culture is among its litany of crimes. Russian forces have systematically pillaged valuable artifacts and artworks, imposed Russian-language school curriculums in places they occupied, and used beatings and torture for forced “russification” in occupied areas.

Accurate and thorough documentation of these atrocities now, while memories are fresh and physical evidence is available, is crucial to ensure justice in courts of law. What is clear given the scale of the violations, is that a multitiered, cross-cutting approach is needed, which will require sustained resources and effective coordination by a range of actors, primarily the Ukrainian authorities, but involving the ICC, judicial officials in third countries, and others. This goodwill needs to be translated into political stamina and strategy to ensure the breadth of abuses are addressed effectively, credibly and comprehensively.

Russian forces are responsible for the overwhelming majority of abuses. Still, allegations of abuse by Ukrainian forces should be duly investigated, with those responsible be held to account in a fair trial. Measures should also be put in place to protect lawyers representing them. Effective justice, after all, means impartial justice.

The substantial global response to crimes in Ukraine showed what’s possible when governments come together, but the absence of a similar response to address grave crimes elsewhere like Afghanistan, Ethiopia and Palestine brought into sharp relief the international community’s double standards. This inconsistency risks eroding the credibility of the entire international justice system.

The challenge is to leverage the world’s response to the war in Ukraine to deliver impartial, comprehensive justice wherever it is needed by ensuring consistent financial, political, and practical support for credible accountability efforts. The international community can and should strengthen the justice response worldwide and replicate this principled support in other contexts where civilians pay the highest price for unbridled impunity.

Tirana Hassan is executive director of Human Rights Watch.

@tiranahassan

Tirana Hassan is executive director of Human Rights Watch.

@tiranahassan

31 Weltzeit 2023

The city of Bucha has become a symbol for Russian forces’ atrocities, but evidence is plentiful elsewhere.

Text Yevhen Hlibovytsky

More than 8 million Ukrainians found themselves abroad, mostly in the EU in 2022, according to the UN. A similar number of Ukrainians have been displaced internally. As the war continues, how many of them will be able and willing to go back? What kind of life awaits them?

On the surface it would seem simple and logical: people flee the war and the destruction of their homes. Once the war will be over most of them should plan to go back to restore their lives in a familiar environment, some mostly those, whose towns and homes were destroyed would seek either to move elsewhere in Ukraine or stay where they found refuge.

Reality is more complicated. Many Ukrainian refugees perceive going back home not literally going back where they came from, but also going back to the old time and old lifestyles they enjoyed. Some, who tried to come back, or visit have learned that returning now is not possible. The war has destroyed not only the buildings and infrastructure. It has also changed the ways people went about their lives. For many of them there is no way back, only forward.

The war has catalyzed the already ongoing political and social transformation. Over the years people, who were favorable of Russia, have moved through a period of ambivalence, and eventually incrementally joined the motion towards Western values and the EU. Now that choice has become almost unanimous from grassroots up. A change of political orientations goes beyond language, religion, ethnicity or place of birth. Ukraine that was tilting towards greater unity for some time has decisively become a country divided no more.

Most Ukrainians have come to the painful realization that Russians of different political affiliations share a similar colonial sentiment that drives the war against Ukraine. Sociologically, Russia has gone from being viewed as a friend by most Ukrainians to being viewed as a foe by almost all. And where the fault lines still exist, they went through families, friendships, business partnerships, consumer loyalties and ruptured relations with little hope for healing them fast, or ever. Social media multiply the stories of relatives being disowned striking cases for the society where family is usually the last bastion of unconditional acceptance against any kind of hostile challenges.

Economy has transformed, too. The fate of many Soviet heavy industry giants, mostly in the occupied East of Ukraine, was sealed by advancing Russian army. The demise weakens industrial oligarchy, whose seats at the political decision-making table are no longer granted. While loss of heavy industry is a painful economic shock, it also opens new development paths. The younger and more educated Ukrainians dispersed across Ukraine and abroad in search of security and new opportunities. However, the shock unproportionately hit the oldest and least adaptive Ukrainians, full of paternalistic expectations. They are the

Ukrainians leave the country in search of safety.

Ukrainians leave the country in search of safety.

32 UKRAINE

© picture alliance / NurPhoto / Artur Widak

The new Ukrainian reality

33 Weltzeit 2023

ones most likely to stay where they are, despite the frontline changes, and try to survive clinging to their windowless flats, smashed furniture and hoping that somehow life will come back to normal. That hope is rather irrational and represents the legacy of the world these people once lived in, where the state cares for people who give up their agency.

The demography of Ukrainian refugees is diverse, but not really representative of Ukraine. At the beginning of the war the two biggest cities in Ukraine the capital Kyiv and its former early Soviet capital Kharkiv were under fire and risk of capture. Their residents made up a great part of those who left. Not aware how the events on the ground would play out, many people decided that it was safer to stay in the suburbs of Kyiv than inside the city, where service or supply disruption could be disastrous. Those who moved to Bucha or other nearby towns often went through hell. Others went further West or even abroad to a safer uncertainty.

Many fleeing residents had much to lose. Among refugees both in Ukraine and outside the number of skilled, experienced, university-educated, multilingual people, and those with accessible savings was greater than national average. Some were more prepared for the war than the others, but a significant number had a safety net to sustain them at least several months. The larger Ukrainian cities away from the war zone were flooded with people. Hotels were overbooked, flat rents skyrocketed, local authorities organized makeshift shelters in gyms and schools. Lots of Ukrainians moved in with their relatives and friends. Eventually, the waves reached smaller towns. In some places the number of residents doubled, compensating for many years of population decline, bringing long abandoned realty back in

service, improving consumer economy, supplying rare skills and talent to the suffocating local job market. Often the entrepreneurs would run crowdfunding campaigns to restart their businesses in the new places. It took about half a year for things to become clear again: some businesses closed, others were looking to replace their conscripted employees, a few were trying to seek new opportunities. In general, the small business economy has become more resilient than expected, often offering lifelines to those in dire need.

A great number of people took volunteering tasks,

forming unprecedented networks, supplying the army with drones, night-vision sets, importing second-hand SUVs for the frontline or sending money to professional foundations that managed to buy a satellite already in space or import sophisticated technology. Volunteering became an ultimate manifestation of empathy, a bonding process in a torn society, helping people to cope, get a sense of belonging, reaffirm their dignity. Many refugees would volunteer in kind, offering their skills to the community.

As Russian troops were pushed back in the North of Ukraine, residents started

The lack of jobs, constant air raids and severe electricity shortages forced many to leave again.

Rebuilding begins as soon as Russian forces retreat.

34 UKRAINE

© Jose Colon / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

returning to Kyiv and other cities. However, the lack of jobs, constant air raids and severe electricity shortages forced many to leave again. Others stayed, trying to adjust their lifestyles to always being under a vivid threat.

It was not until early summer of 2022, when the Ukrainian border service witnessed for the first time that more Ukrainians crossed the border into Ukraine, than out. The Ukrainian government prohibited most men aged 18-60 (except those with three or more underage children, or single caretakers, or those with a special government-issued permission) from leaving the country, so the majority of international refugees are women with underage children. Giving their children the best education possible has become a key priority for Ukrainians abroad. Many will likely prefer to stay until the children end their school, but some keep their children in the Ukrainian online classes as well, signaling that they would like to return as soon as it becomes feasible.

The Ukrainian migration of 2022 is in many ways an untypical one. Studies show that the migrants stay very attached to Ukraine. They go an extra mile to protect their identity and, unlike the previous wave of Ukrainian migration in the 1990s, are determined to pass it on to the next generation. They are driven to start or expand existing Ukrainian institutions and are searching for ways to build up political influence. Despite the initial shocks, this wave of Ukrainian migration is more self-aware, has clear goals, is looking to become instrumental in a greater cause of saving Ukraine and persuading the outside world of the danger of leaving the business of defending Ukraine half-done. The fear of a deceitful truce that would allow Russia to regroup and attack again is a strong motivating force for majority of active Ukrainians.

How many of the displaced people will be able to go home very much depends on how the war ends. Will Putin be defeated? Will Russian colonialism come to an end? Will China or Iran throw a lifeline to Russia that would allow the war of attrition to last indefinitely? The answers to these and many other questions will define personal strategies of the people affected by the war. Rebuilding will be often delayed by the need of demining. Even in the best-case scenario this war has and will continue to produce major economic, demographic, social shifts inside Ukraine that may last for generations. But the new Ukraine is filled with a new sense of agency and eager to become a success story.

Yevhen Hlibovytsky

runs a boutique think tank researching Ukraine’s social transformation. He is also a lecturer at Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv.

@yhlibovytsky

The nonprofit organization ”We repair all together” is committed to helping people rebuild their own homes.

35 Weltzeit 2023

© picture alliance / AA / Jose Colon

36 UKRAINE

Bringing aggressors to justice

On February 24, 2022, Russia began an open, fullscale invasion of the territory of Ukraine. It was the third phase of the international armed conflict that started with the act of Russian aggression against Ukraine in February 2014, which led to the occupation of Crimea and continued with the occupation of parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

International response was soft, it did not include massive economic sanctions against Russia, or attempts to prosecute Russian leaders for the crime of aggression.

It was only after the fullscale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, accompanied by massive violations of international humanitarian law and human rights, that a shocked international community began to respond and to call a spade a spade in March 2022, 141 countries, against five, out of 193 countries adopted the UN General Assembly (GA) resolution condemning “the

aggression by the Russian Federation against Ukraine”.

The ICC jurisdiction: gaps and challenges

Since the beginning of the large-scale invasion, the ICC Prosecutor announced that he had proceeded to open an investigation, and on March 17, 2023, the ICC issued arrest warrants for Putin and one of his minions, the children’s ombudswoman Maria Lvova-Belova, for alleged war crimes committed in Ukraine namely the deportation of children. According to Art. 27 of the Rome Statute, Putin has no immunity from the ICC, even as a sitting president.

The significance of these arrest warrants cannot be overstated. It means that the 123 States Parties to the ICC are not only able, but obliged, to arrest the President of Russia. It also means that the rest of the world has the right do the same, although they are

Text Oksana Senatorova

People hang a painting at an exhibition dedicated to the liberation of Bucha.

37 Weltzeit 2023

© Maksym Polishchuk/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

not obliged by the Rome Statute. From a head of state who, at the beginning of 2022, had a queue of visitors eager to sit at his very long table, Putin has become an outcast.

There are, nevertheless, many risks of undermining the ICC’s authority through political games. Currently, there is a broad discussion about the future of Putin’s visit to the BRICS summit in South Africa, which as an ICC member, is obliged to arrest him, though it also has long-standing close relations with Russia. Hungary has said it would not arrest Putin, referring to the lack of national legislation on cooperation with the Court.

Most importantly, while the ICC will continue to consider evidence of other crimes committed by Putin and his clique, it cannot yet prosecute them for the crime of aggression. As a result of a political compromise, the ICC’s jurisdiction over the crime of aggression is more limited than over other crimes. The referral of the situation in question to the ICC by the UN Security Council is also impossible as long as Putin remains acting president and controls the use of the Russian veto in the UN SC.

Even more cynical is the fact that on April 1, 2023 Russia took the chair in the UN SC. The very fact that an aggressor state will lead a body created to combat the use of force and large-scale human rights violations is beyond common sense.

In October 2022, the UN GA adopted a resolution, stressing the need to establish conditions under which the ICC could exercise jurisdiction with respect to the crime of aggression. The ICC strongly supports this idea. There are various proposals as to how this could be done, e.g. bringing jurisdiction over the crime of aggression to the common denominator with other crimes; thus providing for the possibility of the General Assembly referring the situation to the ICC bypassing the UN SC. Although it is clear, that

any amendment will take time and it may end with more compromise, it is the right way. The way out could be easily found, i.e. through ratification of the Rome Statute and acceptance of the amendment, but there is no guarantee that Russia would do that even in case of a regime change.

That is why parallel efforts should be made to create a functioning mechanism of accountability for the crime of aggression committed by Putin and his entourage. The crime of aggression is, as the Nuremberg Judgement stated, “the supreme international crime <… containing> within itself the accumulated evil of the whole”. If we do not prosecute it per se, we open the door to chaos: any leader can commit acts of aggression, knowing that the system of deterrence will not work.

The circle of those persons in the Russian leadership, who committed the crime of aggression, does not necessarily overlap with the circle of war criminals, which means that without the creation of a

Oksana Senatorova

is Director of the Research Centre for Transitional Justice at Yaroslav Mudryi National Law University, Kharkiv, Ukraine.

A poster reads “Wanted dead or alive. Vladimir Putin for genocide”

A poster reads “Wanted dead or alive. Vladimir Putin for genocide”

38 UKRAINE

© Jakub Porzycki / NurPhoto via Getty Images

mechanism to prosecute the aggression, its perpetrators might reach the haven of impunity.

Most importantly, the circle of victims of the crime of aggression is by no means the same as the circle of victims of other international crimes. The aggression destroys the entire human rights architecture of the country against which it is unleashed, causing direct, indirect and cascading damage in all spheres of life: thousands of Ukrainians, both, combatants and civilians, have lost their lives and health, millions became IDPs and refugees, have lost and continue to lose their jobs, housing, education and other social, economic and environmental rights. All of this calls for international cooperation in creating an effective accountability mechanism where the voice of victims and survivors of the crime of aggression is duly taken into account.

Filing the gap

Immediately after the large-scale invasion in 2022, the idea to create a special tribunal to prosecute Russian leadership for the crime of aggression was born. There were many different proposals from outstanding international and Ukrainian lawyers and politicians, non-governmental organizations which were supported by UN GA resolutions and in-depth analysis and echoed in the reports of human rights institutions.

In February this year, the EU announced the creation of the new International Centre for the Prosecution of the Crime of Aggression against Ukraine (ICPA) to be set up in The Hague. Its main purpose is to enhance investigations into the crime of aggression by securing key evidence and facilitating the process of case-building at an early stage.

Now the Ukrainian President’s Office is considering three models of a special tribunal for the crime of Russian

aggression against Ukraine. The first option is the establishment of a Special Tribunal on the basis of an agreement between Ukraine and the UN, with the adoption of a corresponding resolution by the UN GA, which carries the risk of postponing the start of a tribunal’s work because of the need to gather a sufficient number of votes. Second the establishment of the tribunal on the basis of a multilateral open international agreement between the states of the civilised world the so-called “Nuremberg model”.

Third option is the establishment of the hybrid court under Ukrainian law and jurisdiction, i.e., as part of the Ukrainian judicial system, with varying degrees of internationalisation, such as international judges and prosecutors, a location in Europe, international support etc. Apologists for this idea include France, Germany, the UK and the USA, partly due to some of them having limited the ICC’s jurisdiction over aggression, mainly because they want to avoid the risk of setting up similar tribunals against themselves and prefer not to confront the Global South by granting exclusivity to Ukraine and blind-spotting their alleged precedents of illegal use of force (e.g. in Iraq, 2003).

The first two options are preferable for Ukraine because they would demonstrate the world’s readiness to deter criminals who commit aggression, provide broader legitimacy and eliminate the problems of personal immunities of officials of the aggressor. If the hybrid tribunal would not be endorsed by the UN GA, CoE or the EU, or a larger number of states, it would not be international in nature, which means that personal immunity would continue to apply to members of government and the same could be relevant for the functional immunities.

The ICC has taken the initiative by issuing the arrest warrant against Putin, and now he is in danger of being arrested

in at least 123 countries. However, it should be remembered that the ICC cannot prosecute him for the crime of aggression and cannot “share” its power to revoke personal immunity with another, less international tribunal. Moreover, other members of the Russian government with personal immunities, namely Sergey Lavrov and Mikhail Mishustin, are still without ICC warrants, as are many other Russian officials with functional immunities who took part in the decision to invade Ukraine and should therefore be prosecuted for the crime of aggression. The option of setting up the International Tribunal along the lines of one of the first two models might already be feasible among the coalition of states supporting the idea.

The lack of enforcement tools in existing international law to deter aggression should not be a reason for pessimism but a cause to further strengthen the system of international criminal justice and reinforce the inevitability of prosecution for this supreme international crime. For this reason, the ICC Statute should be improved to make it the most appropriate institution to prosecute the crime of aggression. Until the ICC is reformed, all senior Russian and Belarusian officials who have committed the crime of aggression should be brought to justice by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Crime of Aggression based on an international agreement.

39 Weltzeit 2023