2

EDITED BY ARTHUR FINK

CLAUDINE GRAMMONT

JOSEF HELFENSTEIN KUNSTMUSEUM BASEL

DEUTSCHER KUNSTVERLAG

3

4

5 74 REPRINTS 77 LE SALON D’AUTOMNE L’ILLUSTRATION, Nº 3271, NOVEMBER 4, 1905 80 LOUIS VAUXCELLES, LE SALON D’AUTOMNE GIL BLAS, OCTOBER 17, 1905 88 LOUIS VAUXCELLES, LA VIE ARTISTIQUE GIL BLAS, OCTOBER 26, 1905 92 MICHEL PUY, LES FAUVES LA PHALANGE, NOVEMBER 15, 1907 102 GELETT BURGESS, THE WILD MEN OF PARIS THE ARCHITECTURAL RECORD, Nº 140, MAY 1910 119 PLATES 239 CHRONOLOGY 250 APPENDIX 253 BIBLIOGRAPHY 256 IMAGE CREDITS 257 LIST OF WORKS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The exhibition was made possible by the generous support of:

Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne

Bundesamt für Kultur

Credit Suisse (Schweiz AG)

Isaac Dreyfus-Bernheim Stiftung

Karin Endress

Simone und Peter Forcart-Staehelin

Dorette Gloor-Krayer

Rita und Christoph Gloor

Annetta Grisard-Schrafl

Stiftung für das Kunstmuseum Basel

Trafina Privatbank AG

Heivisch

Anonymous sponsors

The Kunstmuseum Basel would like to thank the international public and private collections for their generous support and loans.

Austria

Albertina, Vienna, Klaus Albrecht Schröder

Sammlung Batliner, Albertina, Vienna, Klaus Albrecht Schröder

Denmark

Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Mikkel Bogh

France

Fondation Jean et Suzanne Planque, Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence, Bruno Ely

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux, Sophie Barthélémy

Musée Unterlinden, Colmar, Pantxika De Paepe

Musée de Grenoble, Grenoble, Guy Tosatto

Archives Henri Matisse, Issy-les-Moulineaux, Anne Théry

Musée d’art moderne André Malraux, Le Havre, Annette Haudiquet

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, Lyon, Sylvie Ramond

Musée Cantini, Marseille, Guillaume Theulière

Musée Matisse, Nice, Claudine Grammont, Aymeric Jeudy

Galerie Bernard Bouche, Paris, Bernard Bouche

Galerie de la Présidence, Paris, Florence Chibret-Plaussu

Centre Pompidou, Paris, Laurent Le Bon, Xavier Rey

Collection Larock, Paris, Marc Larock

Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris, Paris, Fabrice Hergott

Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Christophe Leribault

Musée d’art moderne et contemporain, Strasbourg, Paul Lang

Musée de l’Annonciade, Saint-Tropez, Séverine Berger

Germany

Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg, Söke Dinkla

Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Susanne Gaensheimer

Museum Folkwang, Essen, Peter Gorschlüter

Collection Hasso Plattner, Potsdam, Stephanie Ullrich

Arp Museum Bahnhof Rolandseck, Remagen, Julia Wallner, Susanne Blöcker

Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Christiane Lange

6

United Kingdom

Tate Modern, London, Maria Balshaw

Japan

Musée Marie Laurencin, Tokyo, Hirohisa Yoshizawa

Spain

Colección Carmen Thyssen, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Guillermo Solana

Switzerland

Jacques Herzog und Pierre de Meuron Kabinett, Basel

Musée des Beaux-Arts de La Chaux-de-Fonds, David Lemaire

Association des Amis du Petit Palais, Geneva, Claude Ghez

Galerie Rosengart, Lucerne, Angela Rosengart

Sammlung Pieter + Catherine Coray, Montagnola

Hahnloser/Jaeggli Stiftung, Villa Flora, Winterthur, Beat Denzler

Sammlung Emil Bührle, Kunsthaus Zürich, Zurich, Lukas Gloor

Sammlung Gabriele und Werner Merzbacher, Kunsthaus Zürich, Zurich

Kunsthaus Zürich, Zurich, Ann Demeester, Philippe Büttner

United States

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, Michael Govan

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Max Hollein

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Glenn D. Lowry, Ann Temkin

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Kaywin Feldman

And all private lenders who do not wish to be named.

We would like to express our sincere thanks to the authors of the catalog:

Arthur Fink

Claudine Grammont

Gabrielle Houbre

Peter Kropmanns

Maureen Murphy

Pascal Rousseau

The curators would like to thank all those who supported them in the planning and implementation of the project:

Raphael Bouvier, Anna Brailovsky, Philippe Büttner, Florence Chibret-Plaussu, Elena Degen, Sandra Gianfreda, Ruth und Peter Herzog, Gabrielle Houbre, Rudolf Koella, Jelena Kristic, Jean-Pierre Manguin, Frédéric Paul, Isolde

Pludermacher, Nadja Putzi, Assia Quesnel, Susanne Sauter, Teo Schifferli, Geneviève Taillade, Imogen Taylor, Anne Théry

7

FOREWORD

JOSEF HELFENSTEIN

8

The exhibition Matisse, Derain, and Their Friends: The Paris Avant-Garde 1904–1908 is the first major survey on the Fauves to be shown in Switzerland in decades. It harks back to a pathbreaking curatorial project: the first institutional exhibition on this group outside of France, organized by Arnold Rüdlinger at the Kunsthalle Bern in 1950, when art-historical research into the movement was just beginning. The first significant monograph, Georges Duthuit’s Les Fauves, was also published around the same time.

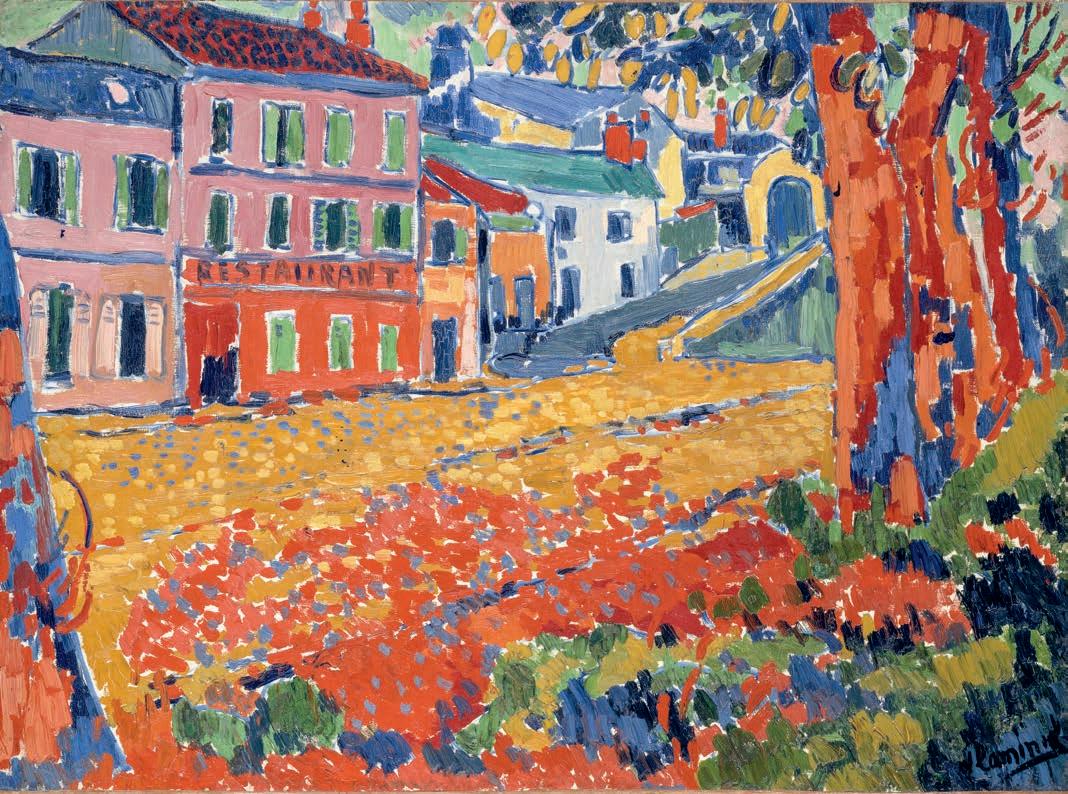

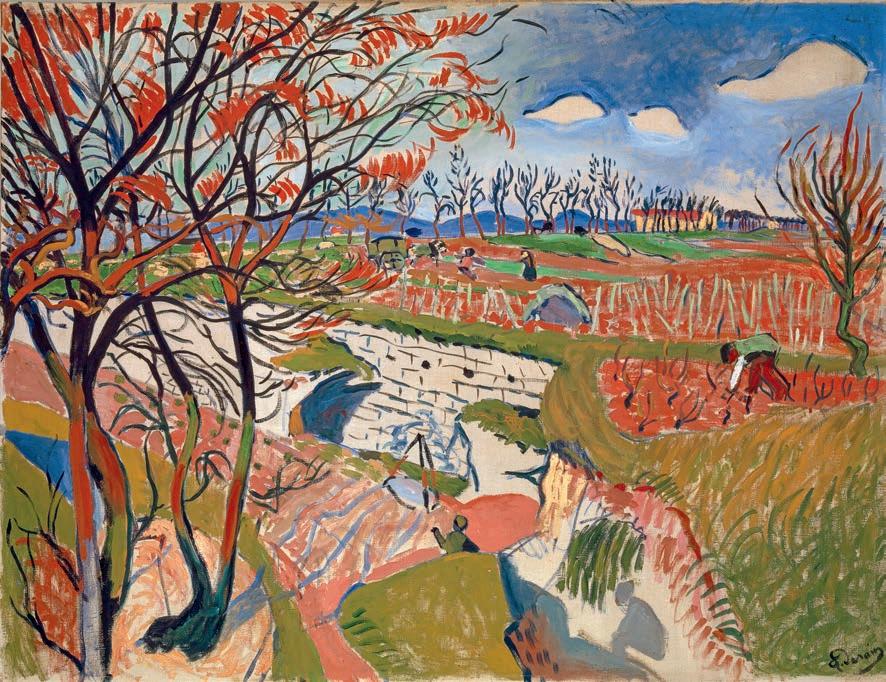

Fauvism was the first avant-garde movement of the twentieth century. It shaped the discourses of painting in the modernist era and beyond. The artists who became canonized in art history as Fauves were concerned with liberating painting from a highly codified set of academic rules. Their ambition was to revolutionize painting through subjective, direct forms of expression. They advocated for a simplification of technical means through a radical departure from painterly conventions. Matisse, whom contemporary art critics called the “Prince,” “King,” “Chief,” and the “Fauve of the Fauves,” commented laconically in retrospect that “tradition was rather out of favor by reason of having been so long respected.” 1 Derain, Vlaminck, Matisse, and their friends made color tangible as a concrete material. In their work, the process of applying paint becomes immediately evident, and brushstrokes have a tactile quality. They dispensed with established modes of modeling such as chiaroscuro shading and outlines, and instead emphasized the flatness of the pictorial support and no longer tried to divide the pictorial space hierarchically into foreground, middle ground, and background. The canvas as a two-dimensional support was accentuated by the frequent occurrence of unpainted areas.

As is the case with the Impressionists, the label “Fauves” originated with a disparaging phrase that was rarely used by the artists themselves at the time. The term Fauves (Eng. wildcats or wild animals) comes from a review of the Salon d’Automne 1905 by Louis Vauxcelles { → pp. 80–87 } , in which he used the word in two different ways. First, the term was for him emblematic of the disdain with which conservative critics reacted to the paintings of the young painters. Vauxcelles describes Matisse as an artist who boldly enters the arena of the wild beasts (in the Salon). At the same time, he used the term to describe the impact of the paintings. The influential critic was referring specifically to the expressive application of paint and the unusual color combinations, which violated the conventions of painting at the time in a revolutionary way. The pictures seemed garish and shocking to contemporary audiences, and moreover featured thematic references to French peinture naïve and borrowed formally from non-Western art and medieval pictorial traditions. Exhibited in the same room was a bust by Albert Marque { → p . 129} , which in its formal design embodied a traditional understanding of art influenced by the Italian High Renaissance. This sculpture, said the critic, appeared as if it had landed in the midst of an “orgy of pure color”— a “Donatello chez les Fauves” (Donatello among the wild beasts). According to anecdotal accounts, the critic had already made a similar statement at the opening of the exhibition (“Tiens, Donatello au milieu des fauves!”), where the analogy caused so much laughter that he used it again in the press. Contrary to popular belief, however, the term did not take hold immediately. It would not be used by Vauxcelles to refer to the artists directly until two years later, in a review of the 1907 Salon des Indépendants. The designation ultimately became established toward the end of 1907 in part due to an essay by Michel Puy { → pp. 92–101 } . By this time, however, the loose association of artists was already fraying. Braque and Derain were drawn to the Bateau-Lavoir, where Picasso had his studio. They were interested in a new style of painting that would later be canonized as Cubism (incidentally, this term, too, originated

9

1 Matisse, “On Modernism and Tradition,” in Matisse on Art, ed. Jack D. Flam (London: Phaidon, 1973), p. 136.

7 In the Matisse literature, see Schneider, Matisse, 1984, p. 29: “The Virgin Mary escapes [from the painting], leaving behind the open book, the emblem of her piety, the vessel that signified her purity, and the glass that is pierced by the light without breaking, symbolizing the Immaculate Conception. Kalf, Stosskopf, Chardin and Matisse, one after the other, inherit the vessel, the glass and the book, as one inherits objects whose value was obvious to a foremother, but passed away with her. The still life, the ‘nature morte,’ is the flotsam and jetsam that remains on the surface of the painting when meaning has withdrawn: the visible world, perceptible to our senses, abandoned by vision.”

8 Victor I. Stoichita, L’instauration du tableau: métapeinture à l’aube des temps modernes (Paris: Méridiens Klincksieck, 1993), pp. 29–41.

9 For a discussion of still life discourses in antiquity, as well as of Cézanne’s still life as a blueprint for the modus operandi of modernist still lifes, which do not represent objects but rather present new painterly propositions, see Norman Bryson, Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting (London: Reaktion Books 1990), pp. 7–59, pp. 60–95.

10 Richard Shiff, “Morality, Materiality, Apples,” in The World Is an Apple: The Still Lifes of Paul Cézanne, ed. Benedict Leca, exh. cat., The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, and the Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario, 2014–2015 (London: Giles, 2014), pp. 145–93.

11 Matisse bought a painting by Cézanne from Vollard the year before, as well as a work each by Gauguin and Van Gogh.

Hillary Spurling, The Unknown Matisse: Man of the North 1869–1908 (London: Penguin Books 1998), pp. 187–88.

12 Vischer, “Beobachtungen zu Chardins Einfluss auf die Stillebenmalerei im 19.

Jahrhundert an Beispielen von Manet, Courbet und Cézanne,” in exh. cat. Basel 1998, pp. 117–35. For details see, exh. cat., Cézanne, Picasso, Braque: Der Beginn des kubistischen Stilllebens (Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje, 1998).

13 Wildenstein, 1963, pp. 9–10. There is a statement Chardin is known to have made about painting still lifes that is particularly interesting in the context of Fauvism: “Here is an object that must be reproduced. If I want to reproduce it faithfully, I must forget everything I have seen so far, even how others have depicted these objects. I must distance it so far from me that I no longer recognize the details. I must direct my main attention to reproducing as appropriately and faithfully as possible the mass as such, the color shading, the roundness, the effect of light and shadow.”

Nicolas Cochin the Younger, “Essai sur la vie de M. Chardin” (1780), ed. Ch. De Beaurepaire, in Précis analytique des travaux de l’Académie des Sciences, Belles-Lettres et Arts de Rouen, vol. 58, 1875–1876, pp. 417–41; trans. the author.

14 Wildenstein, ibid., pp. 50–52

it moves into the center of aesthetic debates again in the late nineteenth century.7 According to a wellestablished art-historical model that explains the genesis of the genre, still life should be understood as the accessories of a sacred image emancipating themselves to become an autonomous picture.8 At the same time, there is the topos of the secret language of still life, of a resistant deeper meaning that cannot be accessed. By virtue of its muteness, still life positively calls out for the decoding of its ciphers and offers itself up to being questioned through the medium of painting, since in it, the fundamentals of pictorial representation are made visible. Indeed, one of the primal scenes of art history—the imitatio contest between Zeuxis and Parrhasius described by Pliny—revolves around two still lifes: one image depicting grapes that deceive birds, and another that shows a curtain capable of deceiving people.9 The fact that still life painting played a central role in Fauvism has to do with two historic artistic predecessors who served as models for the young artists. Around 1900, Paul Cezanne was known to be a pivotal reference figure (“cézannisme” was at its peak in the immediate period after his death in 1906).10 Cezanne’s apples had become icons: Compotier, Verre et Pommes of 1879–80 {FIG. 1} was already being passed around in the 1880s and 1890s by its owner Paul Gauguin as a teaching piece. He would take it with him to the restaurant in the evenings to show it to his pupils and quoted it in his own paintings. Accordingly, the artists of the Nabis revered this painting and Maurice Denis commemorated it in his Hommage à Cézanne (1900 {FIG. 2} ), which depicts the Nabis painters conversing around the painting in the gallery of Ambroise Vollard, who would also exhibit Derain and Vlaminck a few years later.11 The painting was purchased by the author (and critic of the Fauves) André Gide. What Cezanne was to the Nabis, the Fauves, and the Cubists, Jean Siméon Chardin had earlier been to the generation of artists that formed around 1860.12 He too was a figure shrouded in myth, and also an outsider. He came from a family of craftsmen and was trained in a guild as a decorative painter. In part for this reason, he did not paint history paintings and was ridiculed as a sausage painter. In 1728, he managed by a ruse to become a member of the Académie Royale despite his non-academic training.13 In the mid-nineteenth century, he was rediscovered by young artists and writers; his works first began to enter the Louvre, where they were actively copied.14 The fascination with Chardin’s works in the Louvre would continue throughout the following decades.15 In 1893, Matisse copied his first work in the Louvre: La Tabagie (Pipes et vase à boire) {FIG. 3} . 16 And the twenty-four-year-old Marcel Proust (following in the footsteps of Diderot and the Goncourt brothers) wrote a fragmentary hymn of praise to him in 1895. That year, a retrospective was dedicated to the painter at the Palais Galliera.

{1} Paul Cezanne, Compotier, Verre et Pommes (Fruit bowl, Glass, and Apples), 1879–80 Oil on canvas, 46.4 × 54.6 cm The Museum of Modern Art, New York

15 “Yes, I often go to the Louvre. What I study most there is the work of Chardin. I go to the Louvre to study his technique.” Clara MacChesney, “A Talk with Matisse, Leader of Post-Impressionists,” The New York Times, March 9, 1913, cited in EPA, p. 54, note 22.

16 Spurling, The Unknown Matisse, 1998, pp. 85–87. The work is not extant. Copies of Le Buffet and La Raie as well as La Pourvoyeuse are also documented. See Alexis Merle du Bourg, Chardin (Paris: Citadelles, 2020), p. 345.

{2} Maurice Denis, Hommage à Cézanne (Tribute to Cézanne), 1900 Oil on canvas, 180 × 240 cm Musée d’Orsay, Paris

46

Proust describes Chardin as a master who leads us into the magic of the mundane, humble world of things, like Virgil leads Dante into the underworld:

From Chardin we have learned that a pear is as alive as a woman, a plain earthenware vessel as beautiful as a precious stone. The painter proclaimed the divine equality of all things before the mind that contemplates them and the light that embellishes them. He made us leave behind a false ideal so as to enter more broadly into the world of reality and find the beauty that is everywhere, no longer the languishing captive of convention or poor taste, but free, robust, and universal; in opening up to the real world, he draws us out onto a sea of beauty.17

MATISSE’S EARLY STILL LIFES

The first two still lifes on view in the exhibition date from the winter of 1898–99, which Matisse spent in Toulouse { → p . 123} . In the early summer of 1898, while in Corsica, he reads Paul Signac’s essay “D’Eugène Delacroix au néo-impressionisme,” published in Revue Blanche. This text enables Matisse, who is quite conscious of tradition, to anchor his own aspirations in a well-grounded, contemporary intellectual framework, and he adopts the painterly principles formulated within the essay as his own.18 Matisse’s reception of Signac’s essay is evident in Nature morte: Buffet et table, albeit with some deviations from the Neo-Impressionist doxa: the painting features multiple focal points as well as indistinct areas of the image where the contours of the objects become blurred (in the case of the tableware). Moreover, there are outlines and the brushstroke sometimes changes direction, which also serves to outline the objects. The other still lifes with oranges created during this period, including Nature morte aux fruits from the Rosengart Collection, do not show direct signs of Signac’s influence, but are marked by his painterly conceit that a brushstroke no longer has to be descriptive—i.e., it can have a life of its own as a pictorial unit and does not have to coincide with what is depicted. The pictorial signs detach themselves from the represented object. Orange is not necessarily bound to the orange.19

At this time, Matisse was also studying the painting of Chardin and Cezanne in depth, in addition to Signac’s color theory. These different influences, as well as Matisse’s probing, critical appropriation are evident in the series of still lifes with oranges.20 This series is considered the first in which the same object is rendered in different ways of seeing/painting. Oranges are often seen in literature as a symbol of Mediterranean light. As a fruit, they are, so to speak, reservoirs of sunlight. Apollinaire dedicated the closing line to the orange in the poem “Les fenêtres” (1918): “La fenêtre s’ouvre comme une orange / Le beau fruit de la lumière.”21 The orange as a motif also seems to be a reference to the reception of the still lifes of Gauguin, who often painted them as well. Cezanne’s apples, on the other hand, do not appear in Matisse’s work as a direct pictorial quotation.

17 “Nous avions appris de Chardin qu’une poire est aussi vivante qu’une femme, qu’une poterie vulgaire est aussi belle qu’une pierre précieuse. Le peintre avait proclamé la divine egalité de toutes choses devant l’ésprit qui les considère, devant la lumière qui les embellit. Il nous avait fait sortir d’un faux idéal pour pénétrer largement dans la réalité, pour y retrouver partout la beauté, non plus prissonière afffaiblie d’une convention ou d’un faux goût mais libre, forte, universelle; en nous ouvrant le monde réel c’est sur la mer de beauté quíl nous entraîne.” Posthum erstmals erschienen in Le Figaro littéraire, March 27.

1954. Cited in Marcel Proust, Chardin and Rembrandt, trans. Jennie Feldman (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2016), p. 22. For an in-depth discussion of the text see Christie McDonald, “I am [not] a painting: how Chardin and Moreau dialogue in Proust’s writing,” in Christie McDonald and François Proulx, eds., Proust and the Arts (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 40–52.

18 Flam, Matisse, 1986, pp. 58–60. Several such works were produced. For a detailed account of the reception, see Catherine C. Bock, Henri Matisse and Neo-Impressionism 1898–1908 (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1981).

19 Flam, Matisse, p. 61.

20 In his chats with Pierre Courthion, Matisse describes how he moved away from faithful color reproduction when painting still lifes: “The first works I did from nature were always a bit simplistic in their composition. Or, to be precise, they lacked composition altogether. I felt that nature was so beautiful that all I had to do was reproduce it as simply as I could. I sat down in front of the objects I felt drawn to and identified with them, trying to create a double of them on the canvas. But then I was influenced by sensations that led me away from the trompe l’oeil; the green of an apple didn’t match the green on my palette but something immaterial, something that I needed to find. I remember meditating on a lemon. It was posed on the corner of a black mantelpiece. Suppose I managed to copy that lemon, what would I have gained by it? Why did it interest me? Was it such a very beautiful lemon—the loveliest lemon ever? Why take all the trouble to see it rendered (more or less eternal) on canvas when I could replicate my admiration with one just like it—a real piece of fruit that, once I got bored of contemplating it, would make me a nice cool drink? Deduction by deduction, I realized that what interested me was the relation created by contemplation between the objects present: the yellow of the lemon peel on the shiny black marble of the mantelpiece. And I had to invent something that would render the equivalent of my sensation. A sort of emotional communion was created among the objects placed before me.” Pierre Courthion, Henri Matisse, Bavardages: les entretiens égarés, ed. Serge Guilbaut (Milan: Skira 2017), p. 224. 21 Apollinaire, Calligrammes, 2014, p. 15.

47

{3} Jean Baptiste Siméon Chardin, Pipes et vase à boire (Pipes and Drinking Vessel), ca. 1750–75 Musée du Louvre, Paris

5 For a recent and precise study of this genealogy, see Joshua I. Cohen, “Rethinking Fauve ‘Primitivism,’” in The “Black Art” Renaissance: African Sculpture and Modernism across Continents (Oakland: University of California Press, 2020), pp. 23–54.

6 See Johannes Fabian, Le Temps et les autres: Comment l’anthropologie construit son objet (Toulouse: Anarchasis, 2006; repr. 2014).

7 For African art, see Yaëlle Biro, Fabriquer le regard: Marchands, réseaux et objets d’art africains à l’aube du XXème siècle (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2018).

8 Romain Bertrand, Histoire

Much ink has been spilled on the subject of the masks, relics, and statuettes that were brought to Europe from Africa or Oceania— not in order to shed light on their meaning or history, but to establish a genealogy of their “discovery” by European artists.5 It is now generally agreed that Vlaminck bought a Fang mask (Gabon) in a bistro in Argenteuil in 1905 and sold it to Derain, and that Matisse purchased a Kongo-Vili sculpture (Congo Republic) from Emil Heymann at Au Vieux Rouet in 1906, on his way back from a visit to Leo and Gertrude Stein. I will not dwell on these well-known and muchrepeated facts, but will look instead at an aspect of the relationship between European artists and their African or Oceanian sources of inspiration that has often been overlooked: the history of the artifacts themselves. Long consigned to a timeless present,6 these artifacts were often exhibited without any mention of their historicity, as for example at the controversial exhibition held at the New York Museum of Modern Art in 1984, “Primitivism” in 20th-Century Art. In fact, as we will see, the majority of works from Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Oceania were contemporary with “modern” art. The artifacts that the Fauves thought of as “distant” were actually very close, but they were difficult to understand and obscured by an aura of otherness created by the contemporary colonial context. This context was essential to the encounter (or the misunderstanding) between the Fauves and the artifacts from Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Oceania. Although present in European collections since the first cultural exchanges with Europe in the fifteenth century, these objects did not attract the attention of artists until the late nineteenth century, when they began to arrive in Europe in ever greater quantities as a result of the colonial conquests and the growing market for ethnographical curiosities;7 their appearance in museums and colonial exhibitions coincided with an increasing number of articles denouncing the scandals associated with colonialism in places such as the Congo, Dahomey, and Namibia—among them, the reports on the Herero genocide in the satirical journal L’Assiette au Beurre. Maurice de Vlaminck, André Derain, Henri Matisse, and Kees van Dongen in France, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde in Germany did not inhabit ivory towers; this is evident in their paintings. These artists read the news and sometimes published caricatures and drawings in the press; they were appreciative of photography and the art of the postcard (which they made use of in their paintings), and they nourished their libertarian impulses with the repellent and fascinating tales of distant places that they found in newspapers and journals. In order to restore the complexity of the “primitivist” movement of the Fauves, I will consider it from a globalized perspective sensitive to the exchanges and circulation of ideas, images, and objects, while at the same time attempting to write a “more balanced history”8 that illuminates, as far as possible, both the Fauvist approach and that of the sculptors from Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Oceania, most of whom, far from being historically remote as the adjective “primitive” implies, were contemporaries of the Fauves.

52

{2} Temple of Bayon and Cambodian antiquities

FROM ORIENTALISM TO PRIMITIVISM

According to a canonical history of art that proceeds by a series of “isms,” Orientalism was followed by Japonism, while primitivism marked the affirmation of a modern consciousness in early twentieth-century artists. At the root of all these words for artistic movements is a geographical or temporal elsewhere: the Orient for Delacroix (a geography whose ideological dimension we have been aware of since Edward Said’s Orientalism)9 Japan for the Impressionists, and the “primitives” for the Fauves and later the Cubists. For the artifacts originating from Africa, Asia, the Americas or Oceania, the geographical designation was replaced by a temporal one as the word “primitive” denotes anteriority. The logic of the avant-garde demanded that artists seek far afield to find new forms of expression—but that didn’t stop them from adding Persian, Greek, or Egyptian references to their African, Asian, American, or Oceanic sources.10 The Fauves combined their borrowings to distinguish themselves from their predecessors; at the heart of this repeated game of fusion were the people who in those days were more often referred to not as “primitives” but as “Negroes.” The violence of this word stems from its racial load: those considered “Negro” were believed to belong to a distinct race defined by skin color and deemed inferior to the “white” race. By extension, any objects connected with that purported biological category were indiscriminately labeled “Negro,” whether they came from Africa, the Americas, or Oceania. Derain used the same word when he told Matisse of his visit to the British Museum: “Heaped up there pell-mell, as it were—pay attention now—were the Chinese, the Negroes of Guinea, New Zealand, Hawaii, and the Congo, the Assyrians, the Egyptians, the Etruscans, Phidias, the Romans, the Indians.”11 The confusion between artifacts and people can be explained by the exhibition methods that had been practiced in museums since the mid-nineteenth century. The Fauves were keen museumgoers, often visiting the Louvre or the Museum of Comparative Sculpture whose Indo-Chinese room featured a life-size reconstruction of the Temple of Angkor Wat (Cambodia) {FIG. 2} —probably, like the medieval statuary exhibited opposite,12 an inspiration for certain details in Derain’s Dance. Guillaume Apollinaire, Derain, and Picasso all roamed the Trocadéro Museum of Ethnography, and the importance of those visits, for Picasso in particular, is well known.13

THE ROLE OF THE MUSEUMS

A place of trophies and accumulation whose displays combined the spectacular with the scientific (or what passed for such at the time), the Trocadéro Museum of Ethnography celebrated the idea of military and ideological victory; the artifacts and mannequins on show constituted the mechanisms of the evolutionist and racist theories that aimed to demonstrate the savagery of the dominated peoples in

9 Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon, 1978).

10 For the Fauves’ Egyptian sources, see Philippe Dagen, “L’Exemple égyptien: Matisse, Derain et Picasso entre fauvisme et cubisme (1905–1908),” Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français (1984), pp. 289–302. See too, by the same author Primitivismes: Une invention moderne (Paris: Gallimard, 2019)

11 “Là sont entassés pêlemêle pour ainsi dire, suivezmoi bien, les Chinois, les Nègres de la Guinée, de la Nouvelle-Zélande, de Hawaï, du Congo, les Assyriens, les Egyptiens, les Etrusques, Phidias, les Romains, les Indes.” Letter from Derain to Matisse, no date, ca. March 1906, Matisse archives, quoted in Rémi Labrusse, Matisse: La condition de l’image (Paris: Gallimard, 1999), p. 52.

12 Derain was able to see the plaster model of the temple again when it was displayed at the 1906 colonial exhibition in Marseille, where he was also struck by the Cambodian dancers {FIG. 3} who inspired a series of watercolors by Rodin. Writing about the Museum of Comparative Sculpture at the Trocadéro, Dominique Jarrassé and Emmanuelle Polack note that “the plaster models of Egyptian, Assyrian, and hieratic Greek art [were exhibited] facing French works of the eleventh and twelfth centuries” (“les moulages d’arts égyptiens, assyriens et de la période hiératique grecque [étaient exposés] en regard des œuvres du XVème et XIIème français”). Jarrassé and Polack, “Le Musée de Sculpture Comparée au prisme de la collection de cartes postales éditées par les frères Neurdein (1904–1915),” Les Cahiers de l’École du Louvre, 4, 2014, accessed March 31, 2023, https://doi. org/10.4000/cel.476.

13 “When I went to the Trocadéro,” Picasso told Malraux, “it was disgusting. The flea market. The smell. I was all alone. I wanted to get away. But I didn’t leave. I stayed. . . . I understood why I was an artist. All alone in that awful museum with the masks and the redskin dolls and the dusty mannequins” (“Quand je suis allé au trocadéro, c’était dégoûtant. Le marché aux puces. L’odeur. J’étais tout seul. Je voulais m’en aller. Je ne partais pas. Je restais. . . . J’ai compris pourquoi j’étais peintre. Tout seul dans ce musée affreux, avec des masques, des poupées peauxrouges, des mannequins poussiéreux”). André Malraux, La Tête d’obsidienne (Paris: Gallimard, 1974).

53

{3} Cover of Le Petit Parisien: Supplément littéraire illustré June 17, 1906

{4} Le Monde Illustré, May 6, 1882, Le Musée ethnographique du Trocadéro

14 In his correspondence with Vlaminck, Derain wrote in summer 1907: “What one needs is to remain a child forever; one could do beautiful things all one’s life. If instead one becomes civilized, one becomes a machine that adapts very well to life, but nothing more” (“Ce qu’il faut, c’est rester éternellement enfant: on pourrait faire de belles choses toute sa vie. Autrement, quand on se civilize, on deviant une machine qui s’adapte très bien à la vie et c’est tout”). André Derain, Lettres à Vlaminck: Suivies de la correspondence de guerre, ed. Philippe Dagen (Paris: Flammarion, 1994), p. 187.

15 In a letter from July 8, 1905, he wrote to Vlaminck from Collioure: “Wherever I go, I run into anarchists who smash up the world every evening and put it back together again every morning.

It annoys me terribly, especially when I think that I used to be like that” (Partout où je vais, je me flanque dans des anarchistes qui brisent le monde tous les soirs et le reconstruisent tous les matins. Ça m’ennuie beaucoup, surtout d’avoir cru que je l’étais). Letter 57 in Derain, Lettres

16 Patricia Leighten, “The White Peril: Colonialism, l’art nègre, and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” in The Liberation of Painting: Modernism and Anarchism in Avant-Guerre Paris (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2013).

17 For the role played by Vollard in the Fauves’ careers, see Rebecca Rabinow, “Matisse, un rendez-vous manqué,” in De Cézanne à Picasso: Chefs-d’oeuvre de la galerie Vollard, ed. Anne Roqueberg et al., exh. cat., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Paris: Encyclopaedia Universalis, 2007), pp. 143–51.

order to justify the “civilizing mission” of colonization. Contemporary images in periodicals such as Le Monde Illustré {FIG. 4} give an impression of the theatricality of the place, the sense of overcrowding and accumulation: the walls are hung with military trophies; mannequins are displayed on raised pedestals; objects ranging from crude to elaborate are arranged in glass cabinets. Because they gave the illusion of reconnecting with an original art untainted by culture or machines, and because they were thought to establish links with the prehistory of art, the artifacts from Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Oceania captured the interest of the Fauves, although the Fauves did not subscribe to the imperial ideology surrounding them. Their commitment to the noble and wild, to the childhood of art,14 and the idea of radical otherness came closer to a rejection of the West and the moral, bourgeois, military, and industrial values with which it was associated.

ANARCHIST ANTICOLONIALISM

A sketch by Derain dated 1904 and titled “French Republic”

{5} André Derain, République française (French Republic), 1904 Pencil, ink, and Aquarelle on paper, 65 × 32.5 cm Musée Fournaise, Chatou

{FIG. 5} , shows the artist from behind, hands on hips, surrounded by a priest, a gendarme, and a red-skinned woman, her naked body arched, the epitome of the “natural woman”; she seems to be trying to get away from the figure of the priest who is moving toward her. In this drawing, the symbols of (religious and military) authority clash with those of freedom (the savage woman, the artist) in a comical spirit redolent of the caricatures designed and circulated in the anarchist and anticolonial networks to which Derain belonged, at least for a time.15 As Patricia Leighten recounts,16 Vlaminck, Odilon Redon, Roussel, Maillol, and Derain regularly attended dinner parties organized by Ambroise Vollard, the art dealer who helped promote the Fauves in France and abroad.17 It was Vollard, too, who published Alfred Jarry’s Illustrated Almanac in 1901 featuring his Ubu colonial, a satirical anticolonial panorama combining the grotesque and the absurd. Derain’s “Redskin” woman is clearly redolent of the style of the Bonnard drawings that illustrate Jarry’s text, and since Jarry published in L’Assiette au Beurre and the anarchist journal La Revue blanche alongside Félix Vallotton and Toulouse-Lautrec who were both admired by the Fauves, he must have been known to Derain and his circle. Those same journals, Patricia Leighten reminds us, also published the caricatures denouncing the scandals linked to colonization in the French Congo, the Belgian Congo, and Dahomey. It is no coincidence that the artifacts that inspired the Fauves came from those very countries.

54

{6} Fang-Mask (Gabon), arrived in France before 1906 Centre Pompidou, Paris

18 “To Paul Guillaume, slave trader” (“A Paul Guillaume, négrier”), Jean Cocteau’s preface to the first poetry and music recital organized by Pierre Bertin and held in Paul Guillaume’s gallery on November 13, 1917: “Your little Negro Fetishes,” Cocteau writes, “protect our generation whose task is to rebuild on the charming rubble of Impressionism . . . youth is turning toward more robust models. Only thus can the universe become a pretext for a new architecture of sensitivity, instead of always sparkling through eyelashes blinking in the sun. If the Negro eye is quite naked, if nothing prevents things from entering it directly, a great religious tradition must alter them before they emerge from the hand. Negro art should not therefore be compared to the disappointing flashes of childhood or madness, but to the noblest periods of human civilization” (“Vos petits fétiches nègres protègent notre génération qui a pour tâche de rebâtir sur les décombres charmants de l’impressionisme . . . la jeunesse se tourne vers des exemples robustes. C’est seulement à ce prix que l’univers peut devenir le prétexte d’une nouvelle architecture de la sensibilité au lieu de chatoyer toujours entre les cils clignés au soleil. Or, si l’oeil nègre va tout nu, si rien n’empêche les choses d’y pénétrer directement, c’est une grande tradition religieuse qui les déforme avant qu’elles ne sortent par la main. L’art nègre ne s’apparente donc pas aux éclairs décevants de l’enfance ou de la folie, mais aux styles les plus nobles de la civilisation humaine”). Paul Guillaume Archives, Orangery Museum, Paris.

19 This remark is attributed to artist and art dealer Paul Brummer, interviewed by Laurie Eglington in Art News (October 27, 1934).

20 On the subject of this mask, Vlaminck writes:

“The story of this Negro mask has now become historic. It is this mask that started Negro art. . . . It is the first piece of Negro art, from which the Negro art movement emerged, and which gave rise to Cubism” (“L’histoire de ce masque nègre devient historique à l’heure actuelle. C’est ce masque qui a déclenché l’art nègre. . . .

C’est la première pièce nègre d’où est sorti le movement sur l’art nègre et qui a engender le cubisme”).

Letter to Ary Leblond from April 4, 1944, quoted in Le Musée vivant, 21, 1956–

57, p. 377.

21 See Maurice de Vlaminck, “Portraits avant décès” (1943), in Le Tournant dangereux (Versailles: sVo Art, 2008), pp. 112–14.

22 “[C]e même étonnement, cette même sensantion de profonde humanité.”

Maurice de Vlaminck, “Le Tournant dangereux” (1929) in ibid., p. 94.

23 “[L]a mariée, le marié, la belle-mère, le garçon d’honneur, le colonial, la concierge, le croque-mort, le gendarme.” Ibid.

24 “[A]u-dessus d’un comptoir de bistrot, entre des bouteilles de Picon et de vermouth.” Ibid.

25 “[O]bjective, naïve et populaire.” Ibid., p. 92.

FROM THE COLONIES

The first mask acquired by Maurice de Vlaminck had been brought to France from Gabon, the region in the Congo territory (split between Belgium, France, and Portugal at the Berlin Conference of 1895) that was at the heart of the scandals linked to the expansion of the ivory and rubber trade. In 1905, Savorgnan de Brazza was sent on a fact-finding mission following the murder of a Congolese man who had been blown up with dynamite in 1903. He discovered forced labor, arbitrary abuse, women and children who had been taken hostage. Rubber, too, stained with the blood of the men charged with harvesting it, had become a source of the most abhorrent violence— and before long, the rubber trade was mixed up with that of the objets d’art. It was through the rubber trade, for example, that Paul Guillaume, whom Jean Cocteau described, not without ironic humor, as a “négrier” (slave trader),18 started to trade African art in a car workshop on the Champs-Elysées in around 1911: “African rubber merchants often brought back ivory sculptures, masks, and wooden statuettes to sell.”19 But it was before that, in autumn 1905, that Maurice de Vlaminck bought the famous mask {FIG. 6} that he would later sell to Derain for twenty francs,20 soon after buying two statuettes in a bistro in Argenteuil. In his 1929 account of this “discovery” (which he would retell, in a slightly modified form, in 1943),21 Vlaminck associated the “two Negro sculptures” with the world of the fair, that aroused in him “the same astonishment, the same sense of deep humanity.”22 He describes seeing an “Aunt Sally” (jeu de massacre) at the fair, featuring “bride, groom, bride’s mother, best man, colonialist, concierge, undertaker, gendarme.”23 All typical characters, according to Vlaminck, “morbidly poor and hallucinatingly real”—but he is unable to buy them, because their creator refuses to sell to him. Vlaminck then evokes two “Negro sculptures” which he spots “above the counter in a bistro, between the bottles of Picon and vermouth.”24 Like the Aunt Sally figures, the statuettes belong to a form of representation that Vlaminck describes as “objective, naïve, and popular.”25 He associates them with an imaginary of geographical and social margins (the suburbs, the colonies, the working classes),26 and compares them to the brightly colored popular prints known as the “Images d’Epinal” and to the trading cards that he remembers collecting from packets of chicory coffee and copying from the age of twelve.27 In both cases, the act of purchase and the creation of a collection constitute a dual process of appropriation and identification: Vlaminck wanted to create in the same spirit as the fairground artist or the sculptor of the statuettes, much like Paul Gauguin who had left Paris some years previously for the world of rural Brittany and then Tahiti, in search of rupture and renewal. The mask that Vlaminck repeatedly claimed to have been the first to buy—and which thanks to him (as he tells it), sparked a revolution in the perception of art28—probably inspired his 1905 Nu rouge { → p . 197} . In this painting, a woman’s red body is reduced to its nudity, confined within the limits of the frame to bring out its sexual attributes and express the artist’s desire. Inspired by the plastic solutions offered by a mask that was not in any way intended to be seen as a portrait (the idea being not to represent but to embody), Vlaminck has painted a face

26 The imaginary of the margins is also to be found in Guillaume Apollinaire’s poem “Zone” (Alcools, 1913): “You head for Auteuil you want to walk home / To sleep between your fetishes from Oceania and Guinea” (“Tu marches vers Auteuil tu veux aller chez toi à pied / Dormir parmi tes fétiches d’Océanie et de Guinée”). Guillaume Apollinaire, Œuvres poétiques (Paris: Gallimard, 1975), p. 44.

27 Congratulating himself on his sagacity, Vlaminck writes: “It took me a long time to satisfy myself that I was not mistaken. . . . Today, in the glass cabinets of opulent drawing rooms, I see the ships of spun glass that the stallholders used to sell at suburban fairs. Objects of admiration, they have been very delicately, very carefully positioned and are regarded as works of art. I am pleased not to have been mistaken” (“J’ai été bien longtemps à acquérir la certitude que je ne me trompais pas. . . . Actuellement, dans les vitrines des salons cossus, je retrouve des bateaux en verre filé que les forains fabriquaient dans les fêtes de banlieue. Admirés, ils sont poses délicatement, avec d’infinies précautions, et considérés comme des objets d’art. Je suis content de ne pas m’être trompé”). Vlaminck, “Tournant,” p. 92.

28 Ambroise Vollard had a bronze cast made of the mask by the Rudier Foundry which also made casts for Auguste Rodin (until 1904) and Aristide Maillol, among others. The cast of the mask is now held in the collections of the Quai Branly Museum, inv. 75.14393, fig. 5.

55