this auction

Chris Deutscher

Damian Hackett 0411 350 150 0422 811 034

Henry Mulholland Fiona Hayward 0424 487 738 0417 957 590

Crispin Gutteridge Veronica Angelatos 0411 883 052 0409 963 094

ADMINISTRATION AND ACCOUNTS

Alex Creswick (Melbourne) Hannah James (Sydney) 03 9865 6333 02 9287 0600

ABSENTEE AND TELEPHONE BIDS

Annabel Lees 03 9865 6333

SHIPPING

Eliza Burton 03 9865 6333

auctioneers

ROGER McILROY head auctioneer

Roger was the Chairman, Managing Director and auctioneer for Christie’s Australia and Asia from 1989 to 2006, having joined the firm in London in 1977. He presided over many significant auctions, including Alan Bond’s Dallhold Collection (1992) and The Harold E. Mertz Collection of Australian Art (2000). Since 2006, Roger has built a highly distinguished art consultancy in Australian and International works of art. Roger will continue to independently operate his privately-owned art dealing and consultancy business alongside his role at Deutscher and Hackett.

SCOTT LIVESEY auctioneer

Scott Livesey began his career in fine art with Leonard Joel Auctions from 1988 to 1994 before moving to Sotheby’s Australia in 1994, as auctioneer and specialist in Australian Art. Scott founded his eponymous gallery in 2000, which represents both emerging and established contemporary Australian artists, and includes a regular exhibition program of indigenous Art. Along with running his contemporary art gallery, Scott has been an auctioneer for Deutscher and Hackett since 2010.

Lot 25

Del Kathryn Barton Hard Wet, 2017 (detail)

various vendors page 12

prospective buyers and sellers guide page 134

conditions of auction and sale page 136

telephone bid form page 138

absentee bid form page 139

attendee pre-registration form page 140

index page 155

Lot 5

Fred Williams Landscape with Swamp, 1972 (detail)

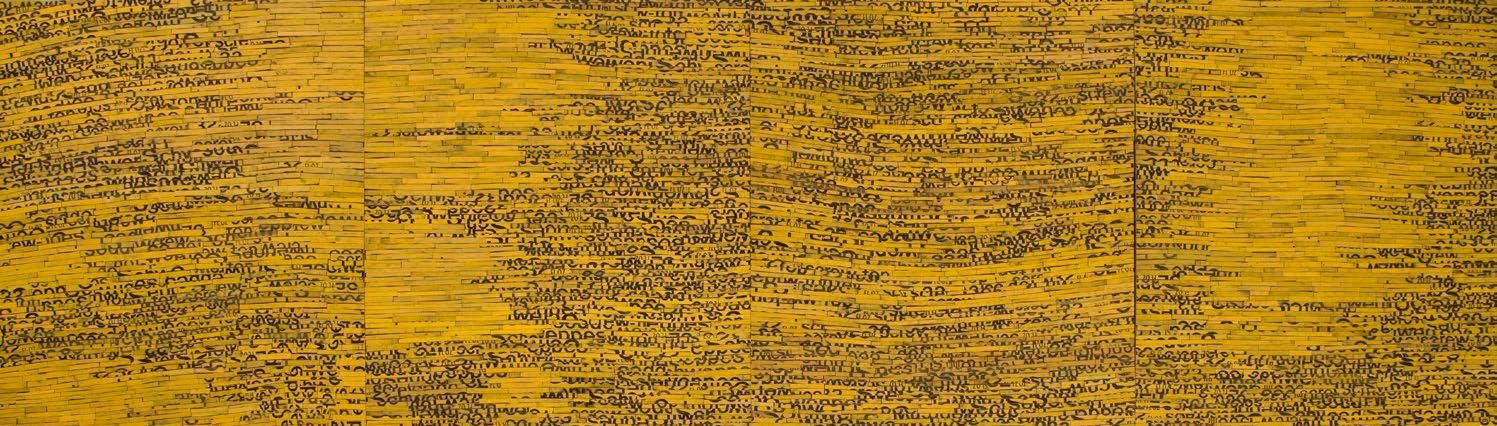

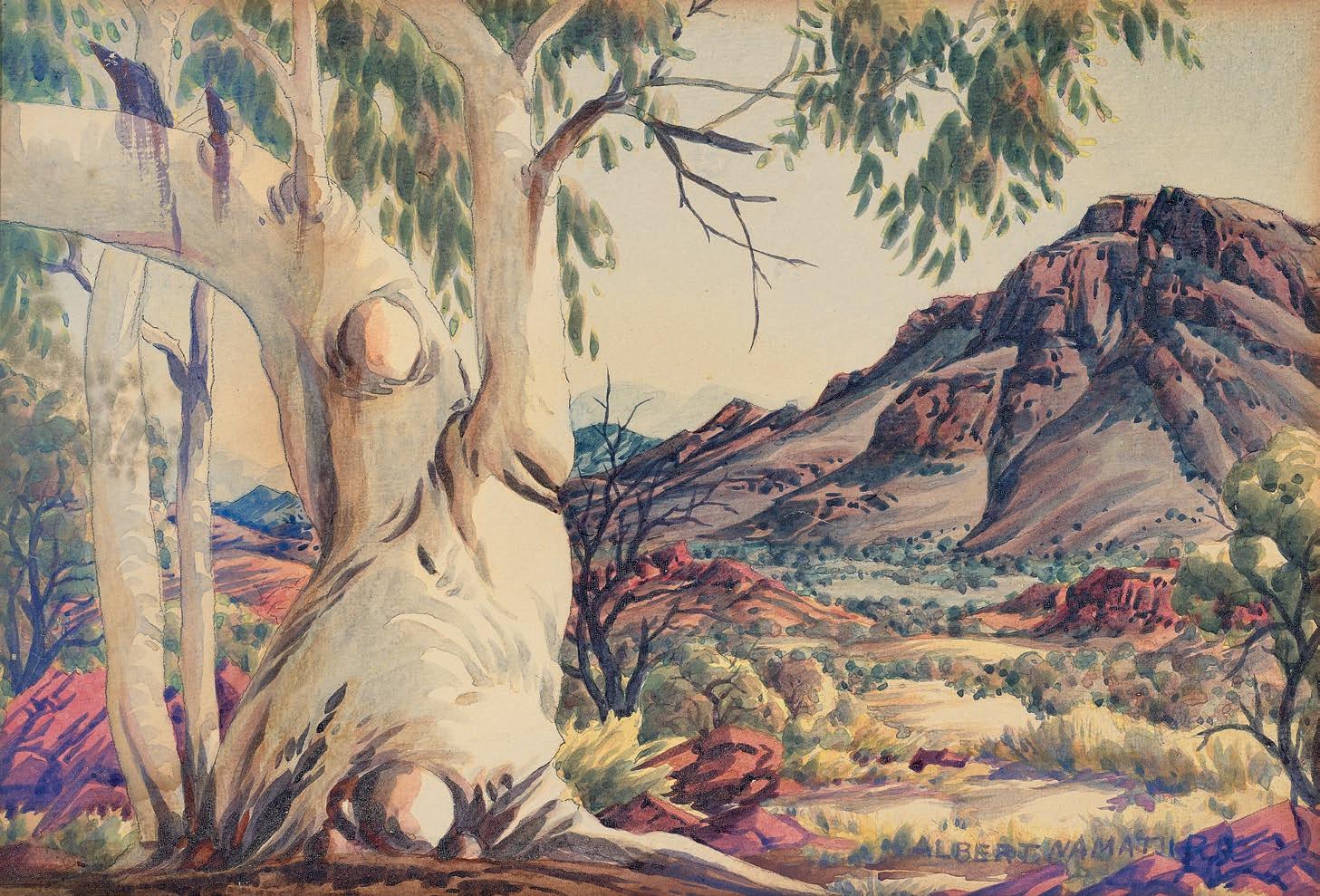

IAN FAIRWEATHER

(1891 – 1974)

PEKING MARKET PLACE, c .1940

gouache and pencil on paper

36.0 x 43.0 cm

signed lower right: I Fairweather

ESTIMATE: $60,000 – 90,000

PROVENANCE

Lina Bryans, Melbourne

Christie’s, Melbourne, 6 March 1970, lot 64 (as ‘Market Place’)

Joseph Brown Gallery, Melbourne

Joan Clemenger AO and Peter Clemenger AO, Melbourne, acquired from the above 6 December 1982

EXHIBITED

Fairweather: A Retrospective Exhibition, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 3 June – 4 July 1965, then touring to: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 21 July – 22 August 1965; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 9 September – 10 October 1965; National Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 26 October – 21 November 1965; Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, 9 December 1965 –16 January 1966; and Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, 10 February – 13 March 1966, cat. 79 (as ‘Market Place’)

Joseph Brown Gallery, Melbourne, 10 – 24 September 1981, cat. 139 (illus. in exhibition catalogue, p. 120, as ‘Market Place, 1940 – 41’)

and fellow artist Lina Bryans – ‘the mysterious lady benefactress’ 2 as Fairweather would call her. Always able to make a simple situation more complicated and fraught, Fairweather – although grateful for Frater’s support – felt humiliated by the process, and it would be some years before he would meet up with Bryans in person.

The works in this group were memories of Peking which he had visited for the first time in 1933 after living in Shanghai for two years. Although only a brief visit, his first impressions were positive, and he was keen to return. For the next year however he circled Southeast Asia, restlessly travelling to Bali, Australia, Colombo and Davao in the Philippines, and finally arriving back in Peking in March 1935. He found the city much changed, he wrote in a letter to Jim Ede, and ‘full of refugee Russians’ who competed for the sort of unskilled work he depended upon while waiting for money from the sale of his paintings in London. 3 All that was left to do was to walk the city, drawing and sketching the temples and bridges, the walls and canals, the crowded markets and busy street stalls. Peking was messy and noisy and, though preferable to the monotony of Melbourne and the irritations of Davao, drove him to distraction. As he found in most instances, places and people were much better after the fact.

In 1938, Fairweather was living in an abandoned theatre in Sandgate, a seaside suburb of Brisbane. Spooked by inexplicable noises and lights throughout the night, he began both sleeping and working in the old projection room where he could at least close the door to feel more secure. In spite of this he was productive and, as he recounted to his friend Jock Frater, in a few months had completed at least ten works which he intended to send to London for sale.1 Before Fairweather could execute his plan however, Frater managed to sell a large lot to his friend

Such depictions of China are now considered amongst Fairweather’s finest works, and indeed the present, Peking Market Place , c.1940, has all the immediacy and vividness of a photograph snapped in the street. The dark brown and cream figures form a long serpentine line set against a vivid background of indigo blue, a colour used frequently in Chinese ink paintings, with other details picked out in a deep russet. It offers a fleeting impression quickly and perfectly sketched.

1. Roberts, C. and Thompson, J., Ian Fairweather: A Life in Letters, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2019, p. 123

2. ibid.

3. ibid.

DR CANDICE BRUCE

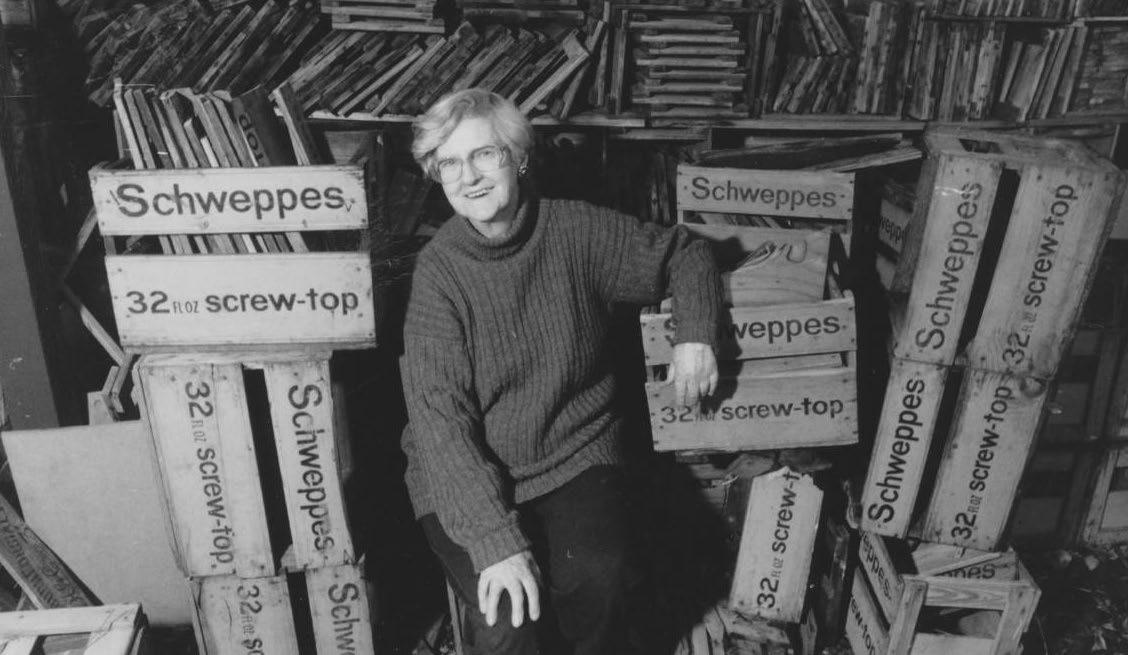

RALPH BALSON (1890 – 1964)

CONSTRUCTIVE PAINTING, c .1942 oil on card

48.0 x 60.0 cm

ESTIMATE: $30,000 – 40,000

PROVENANCE

Private collection, Sydney

Sotheby’s, Melbourne, 4 May 2004, lot 146

Private collection, Sydney

There was never a time when Ralph Balson’s belief that abstraction was the highest form of expression ever diminished. He occasionally wrote about it, his art shifted from non-objective geometric paintings to become gestural and experimental. But critical to everything he produced was his disinterest in colloquial figuration – the landscape and nationalist heroism held no interest. He wanted Australian art to become international without any parochial facade.

Balson’s art is not an intellectual pursuit in itself, echoing those he admired, especially Mondrian. His association with Sydney’s burgeoning modernism shortly after he arrived from England in 1923 was critical. His enduring friendship with Grace Crowley became an arrangement of reciprocal understanding in each other’s pursuits, each exerting a profound effect upon the other. Their art became a marker of abstract art’s secure place in Australian art history.1

Crowley went to France and studied under Albert Gleizes and André Lhôte, where she responded to their reworking of Cubism. Back in Sydney in 1932 Crowley and Rah Fizelle established a School where Balson was a student. In 1939 he was included in Exhibition 1 at David Jones Gallery, the first exhibition in Australia of artists working with abstraction.

In Constructive Painting , c.1942, one finds a work which embraces a serious understanding of European geometric avant garde painting. The painting shares a close conceptual and pictorial system with the artist’s Construction in Green, 1942 (Art Gallery of New South Wales), also executed in oil on card. The overlapping and interlocking translucent forms in halftones surround more strongly defined shapes in red, blue and green – a black rectangle becomes a pictorial anchor. The irregularity becomes a resolved composition of sublime and elegant equilibrium.

The surfaces of Balson’s art are always important and the measured painterly personality in his geometric work is distinctive. Areas of subtle, lushly nuanced variations meet edges that hold the final distinct gesture of the brush. Soft irregular borders remind us that nothing is a conceptual template, that the presence of the artist’s hand is essential.

Balson can appear to us a precursor to many artists from the generation that followed him. Those who found purpose and certainty in geometric abstraction then moved to painterliness in various appearances, where each career signals a particular respect – David Aspden, Peter Booth and Michael Johnson are obvious examples. What they share in common is the depth of their introspection, rather than observation of an external world.

Balson’s autodidactic philosophical curiosities, especially scientific theory, increasingly shaped his thinking. He was born in Dorset in 1890, attended the local village school, left at age 13 and was apprenticed to a house painter and his formative instincts remained. Respect for Balson’s work has never ebbed, from his earliest work to his final Matter paintings he holds a critical presence in each decade of Australian art.

1. as witnessed by the recent exhibition, GRACE Crowley & Ralph Balson, held at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Federation Square, Melbourne, 23 May – 22 September 2024.

DOUG HALL AM

ERIC THAKE

(1904 – 1982)

BRASILIA AT CORIO, 1976

oil on canvas board

60.0 x 50.0 cm

signed and dated lower right: ERIC THAKE 1976 inscribed with title lower left: BRASILIA AT CORIO inscribed with title verso: “BRASILIA AT CORIO”

ESTIMATE: $30,000 – 40,000

PROVENANCE

Estate of the artist, Victoria

Thence by descent

Private collection, Melbourne

EXHIBITED

Eric Thake , Geelong Art Gallery, Victoria, 15 October – 28 November 1976, cat. 29

Eric Thake , Macquarie Galleries, Sydney, 2 – 14 February 1977, cat. 17

A keen observer of the world around him, Eric Thake always carried a sketchbook so that he could record what he saw. As a child he was enthralled by Cole’s Funny Picture Books, especially their visual puzzles, and credited them with his habit of seeing the unexpected and the unfamiliar in the everyday. This unique perspective was combined with a distinctive sense of humour and an eye for design, born in part from the experience of working in the art department of Patterson Shugg process engravers from 1918, and later, as a commercial artist. A draftsman, painter and printmaker of refined skill, Thake produced some of the most memorable images of mid-twentieth century Australian art.

From the early 1970s Thake lived at Geelong where the Corio docks and surrounding industrial landscape captured his attention. The largest painting in his oeuvre, Brasilia at Corio, 1976 depicts a singular gas silo which fills the pictorial space with its huge spherical form. While the artist has paid attention to the details of his subject, he has also played with reality, subtly modifying elements in the service of composition, story-telling and design. Photographic images of similar silos show, for example, that the elegant curve of the external stairs sweeping around

the left-hand-side of Thake’s silo is pure artistic invention, while the flash of red which represents a fire extinguisher dwarfed by the looming bulk of the silo is a classic example of his ironic humour.

The most striking element of this image is the depiction of light and shadow, and in particular, the concentric circles reflected on the silo’s front. Thake’s daughter recalls him explaining that this was simply the result of the way that the sun hit the vertical supporting poles – no doubt with a little artistic licence thrown in.1 The graphic quality of these reflected patterns, the geometric form of the silo and its bright white colour presumably inspired the title which, in characteristic Thake style locates the exotic in the everyday, aligning the industrial waterfront of Geelong with the federal capital of Brazil, a planned city and marvel of modern design and construction (involving, among others, architect Oscar Niemeyer and landscape architect, Roberto Burle Marx) which was inaugurated in 1960.

Thake was the first Australian surrealist and this aspect of his art was identified as early as 1933 when he showed Bluebells, Blue River, 1932 (National Gallery of Victoria) in the annual Contemporary Art Group exhibition. Reviewing the show, Blamire Young observed insightfully that ‘His juxtapositions are sometimes surprising’ 2 and this is one of the defining characteristics of Thake’s oeuvre. While he was aware of the work of English and European surrealists such as Giorgio de Chirico, Edward Wadsworth and Paul Nash (possibly having seen their work in local exhibitions, but known primarily in reproduction from books, magazines and postcards), what distinguishes Thake’s art from that of his peers is the unique ability to construct ‘a bricolage of everyday images to unfix and change, this way and that, the world around us.’3 Indeed, by incorporating the lessons of surrealism into his vision of the world, no matter how apparently banal his subject matter, Thake’s images are at once familiar and yet full of mystery, the uncanny and the unexpected.

1. Conversation with Jenifer Beaty, 4 October 2024

2. Young, B., The Herald, Melbourne, 1 August 1933, cited in Eagle, M. and Minchin, J., The George Bell School: Students, Friends, Influences, Deutscher Art Publications, Melbourne, 1981, p. 26

3. Eagle, M., ‘The 1920s and Eric Thake’ in Eagle & Minchin, ibid.

KIRSTY GRANT

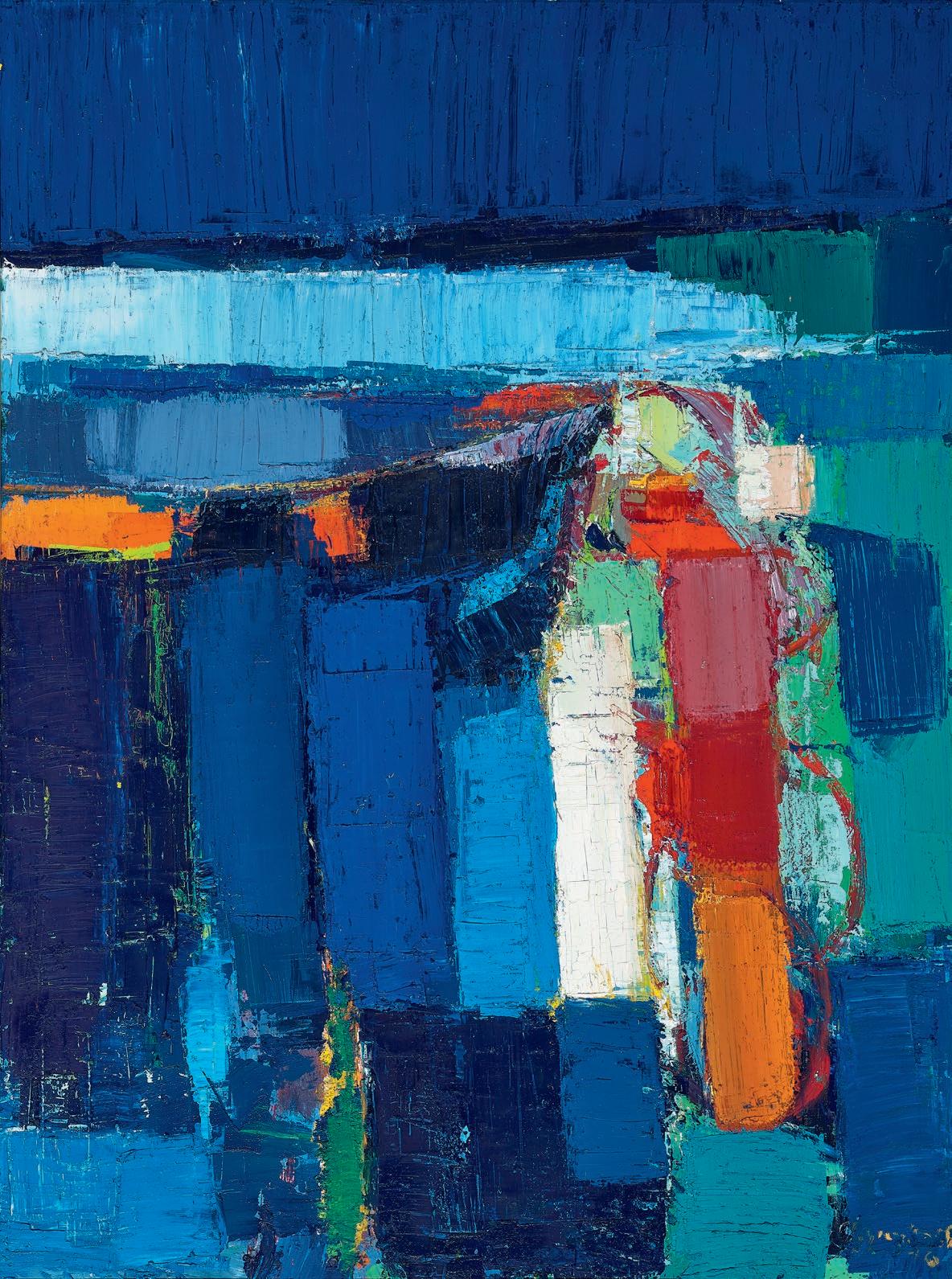

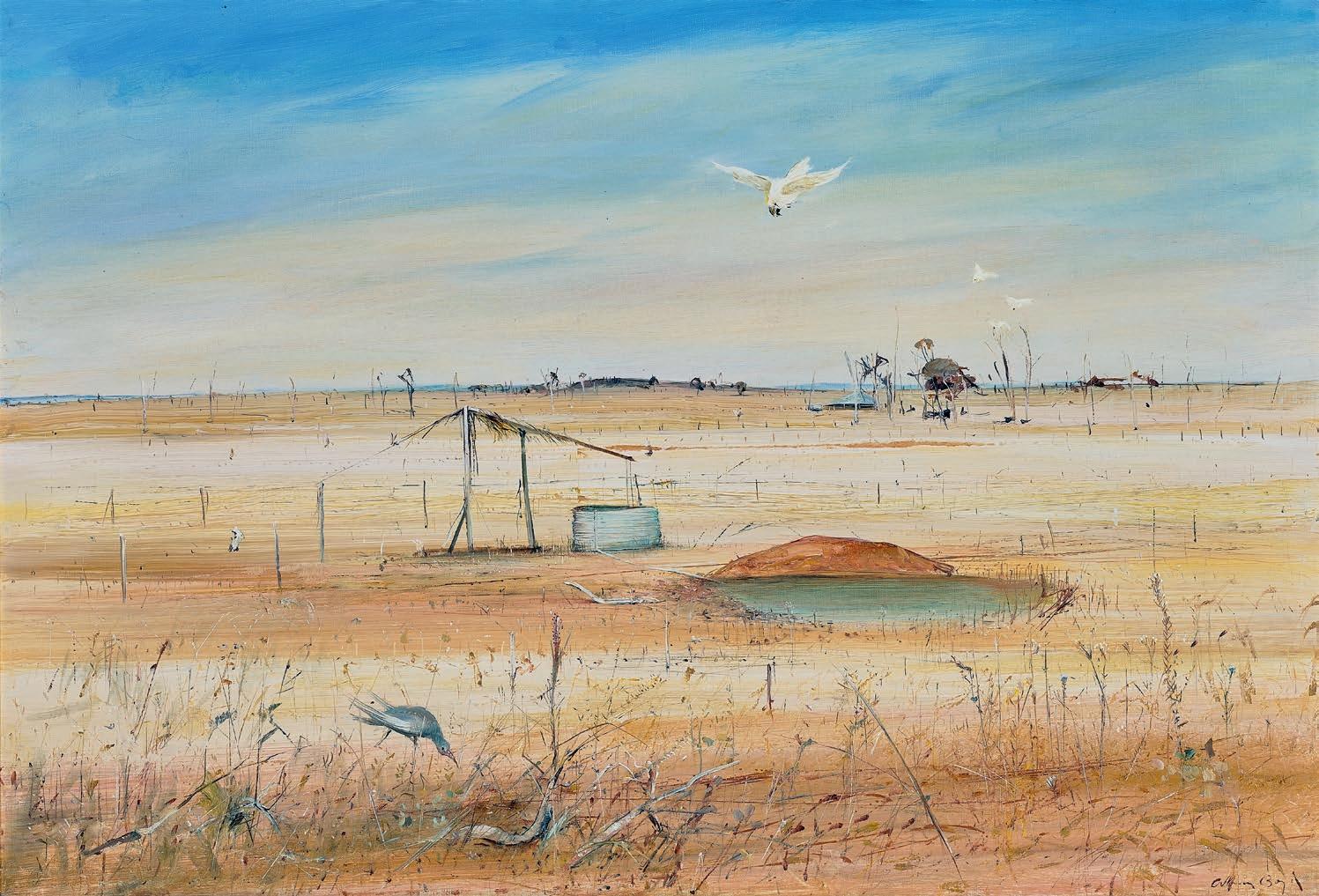

GUY GREY–SMITH

(1916 – 1981)

PT D’ENTRECASTEAUX, 1976 oil and beeswax on composition board 121.0 x 91.0 cm

signed and dated lower right: G Grey Smith / 76 bears inscription on frame verso: GUY GREY-SMITH ‘ANN LEWIS’ 1978 inscribed verso: 31

ESTIMATE: $55,000 – 75,000

PROVENANCE

Estate of the artist Gallery 52, Perth Private collection, Perth, acquired from the above in 1982

EXHIBITED

A Festival of Perth Exhibition: Paintings by Guy Grey-Smith, Old Fire Station Gallery, Perth, 24 February – 16 March 1977, cat. 31

LITERATURE

Gaynor, A., Guy Grey-Smith: Life Force , University of Western Australia, Perth, 2012, p. 266

Guy Grey-Smith is renowned for his powerful visions of the Western Australian landscape, in particular the rocky coasts of the southwest. This love of the sea was instilled in him as a child, travelling over two hundred kilometres with his family for holidays at places like Bunkers Bay and Canal Rocks. These journeys, occasionally by horse and cart, also took in the variety of the natural world as they passed through woodland, fields of wildflowers and soaring karri forests. In Pt D’Entrecasteaux , 1976, Grey-Smith stands 240 kilometres further south at Black Point (now known as Tookulup), a small promontory that looks towards the spectacular Point D’Entrecasteaux, named after the French Admiral who was the first European to sight the area in 1792.

Coastal paintings appear at most stages of Grey-Smith’s trajectory and following them consecutively, they provide signposts as his technique altered to become the celebrated slab paintings of the 1960s and 1970s. Early works such as Albany Landscape (Torbay), 1951 (private collection), and Longreach Bay, Rottnest, 1954 (Art Gallery of Western Australia) are descriptive of the rhythms and natural patterns of the ocean but are still, even placid, when compared to the spiky rock

outcrops in Bunker Bay (Winter ), 1956 (private collection) and Bunker Bay, 1960 (private collection). Conversely, in Kalbarri Landscape , 1959 (Artbank), the crash of the waves and the surge of the rolling surf resonate throughout the scene. Abandoning the theme for much of the 1960s, Grey-Smith returned in the mid-1970s with a passionate sequence of paintings done in his (by-now) trademark process of pigment thickened with a home-made wax emulsion applied using paint scrapers. The work on offer here, Pt D’Entrecasteaux , 1976, belongs to this series and it appears that Grey-Smith has climbed down just below the summit of Black Point, as the lower half of the painting is highly suggestive of the heavily eroded rock forms within the one-hundredmetre-high limestone cliff. This upthrust is then counterbalanced by the horizontality of Point D’Entrecasteaux itself, rendered as a ghostly blue apparition cutting left to right above. Suggestive of a primaeval life force, Grey-Smith succeeds here in ‘divorcing abstraction from romantic self-expression… (his) concern is with the thing, and its value to other observers, and not primarily with the autobiography of (his) own feelings. This kind of classical abstractionism is perhaps more valuable than romantic abstract expressionism, and harder to come by.’1

Pt D’Entrecasteaux was exhibited at Grey-Smith’s remarkable exhibition of 1977 held at Rie Heyman’s Old Fire Station Gallery in Subiaco, Perth, full of ‘glorious colour which seemed to pour out of the gallery as we walked up the street.’ 2 To coincide with the show, Art and Australia published an extended article by noted curator Barry Pearce who celebrated that the artist was deliberately pushing his own boundaries, which was ‘typical of the energetic character of Guy Grey-Smith in seeking to improve and extend the possibilities of his subject without plagiarising himself, and there is no sign of relaxation of his prolific output.’3 Grey-Smith died in 1981 after two equally powerful exhibitions mounted by Ann Lewis at Gallery A in Sydney; and the current owners purchased Pt D’Entrecasteaux from respected Perth gallerist Wendy Rogers in 1982. It has not been seen publicly since.

1. Hutchings, P., ‘The Grey-Smiths’, The Critic, Perth, vol. 2, no. 10, 25 May 1962, p. 82

2. Thomas, C. V., cited in Gaynor, A., Guy Grey-Smith: life force, University of Western Australia Publishing, Perth, 2012, p. 104

3. Pearce, B., ‘Guy Grey-Smith: painter in isolation’, Art and Australia, vol. 15, no. 1, 1977, p. 69

ANDREW

GAYNOR

FRED WILLIAMS

(1927 – 1982)

LANDSCAPE WITH SWAMP, 1972 oil on canvas

71.0 x 97.0 cm

signed lower right: Fred Williams bears artist’s name, title, date, medium and dimensions on artist’s label verso inscribed on artist’s label verso: WILLESMERE [sic] / PARK / (KEW) / PAINTED ON 6 AUGUST 1972

ESTIMATE: $250,000 – 350,000

PROVENANCE

Rudy Komon Gallery, Sydney (RK 3461), (label attached verso)

Private collection, Sydney

Gould Galleries, Melbourne

Private collection, Melbourne

Deutscher and Hackett, Melbourne, 16 April 2008, lot 18

Private collection, Melbourne

EXHIBITED

From Streeton to Whiteley: A Selection of Australian Art, Gould Galleries, Melbourne, 18 October – 10 November 1996, cat. 29 (illus. in exhibition catalogue)

We are grateful to Lyn Williams for her assistance with this catalogue entry.

We are grateful to Brenda Martin Thomas, wife of the late David Thomas AM, for kindly allowing us to reproduce David’s writing in this catalogue entry.

The 1970s introduced some of Fred Williams’ pictorially richest and most interesting works, as seen in Landscape with Swamp , 1972. From the aerial viewpoint and minimalism of the You Yang paintings and the tripartite divisions of his later Lysterfield paintings, his work gave way to the freer compositions and richer colours of the Yan Yean oils of 1972, painted out of doors at the Yan Yean Swamp in company with John Perceval. Unlike earlier works, they are clearly identified with the place and its particularities, being described by Patrick McCaughey as ‘among the finest and most interesting of all the oil sketches of the early 1970s.’1 Although inspired by a different place, Landscape with Swamp belongs to this group in terms of motif and achievement. Now

more traditional in pictorial presentation, the brilliance of palette and vitality of form gains in emphasis through the use of black, outlining tree trunks and water’s edge. It provides an element of control, as it were, for the rich tangle of colour and paint, seen again in such works as Yan Yean II (Dog Chasing Possum) and Yan Yean in the collection of the Queensland Art Gallery, both painted in 1972.

Landscape with Swamp is identified by the artist’s note on the back of the painting as Willsmere Park in Melbourne’s East Kew, close to the Kew Billabong and River Yarra. Williams even added the date on which it was painted, indicating that both location and time had significance in terms of the painting itself during this highly fertile period of his art. While the locale is different from Yan Yean, the motif is similar and marks the genesis of the great Kew Billabong series of three years later. Previously it had been thought that Williams commenced this series in April of 1975. 2 Williams considered the Billabong ‘splendid’ and found ‘it a great place to work.’ 3 It was within easy distance from his home and provided Williams with what McCaughey described as ‘a retreat, a new starting point with some point of departure from previous work.’4 Quiet paintings of the transitory illusion of light reflecting on water and thoughts of Monet’s Waterlilies led many to see these paintings as being ‘as close to the spirit of French Impressionism as any of Williams’ works.’5 Such developments to come are hinted at in Landscape with Swamp , where the splendidly vigorous handling of the monumental in nature is destined to give way to the intimate. The ephemeral detritus of man and nature were to replace the grandeur of trees beside the bank and their solid reflections in the water.

1. McCaughey, P., Fred Williams, Bay Books, Sydney, 1980, p. 240

2. Mollison, J., A Singular Vision: The Art of Fred Williams, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1989, p. 199

3. ibid.

4. McCaughey, op. cit., p. 285

5. Mollison, op. cit., p. 201

DAVID THOMAS

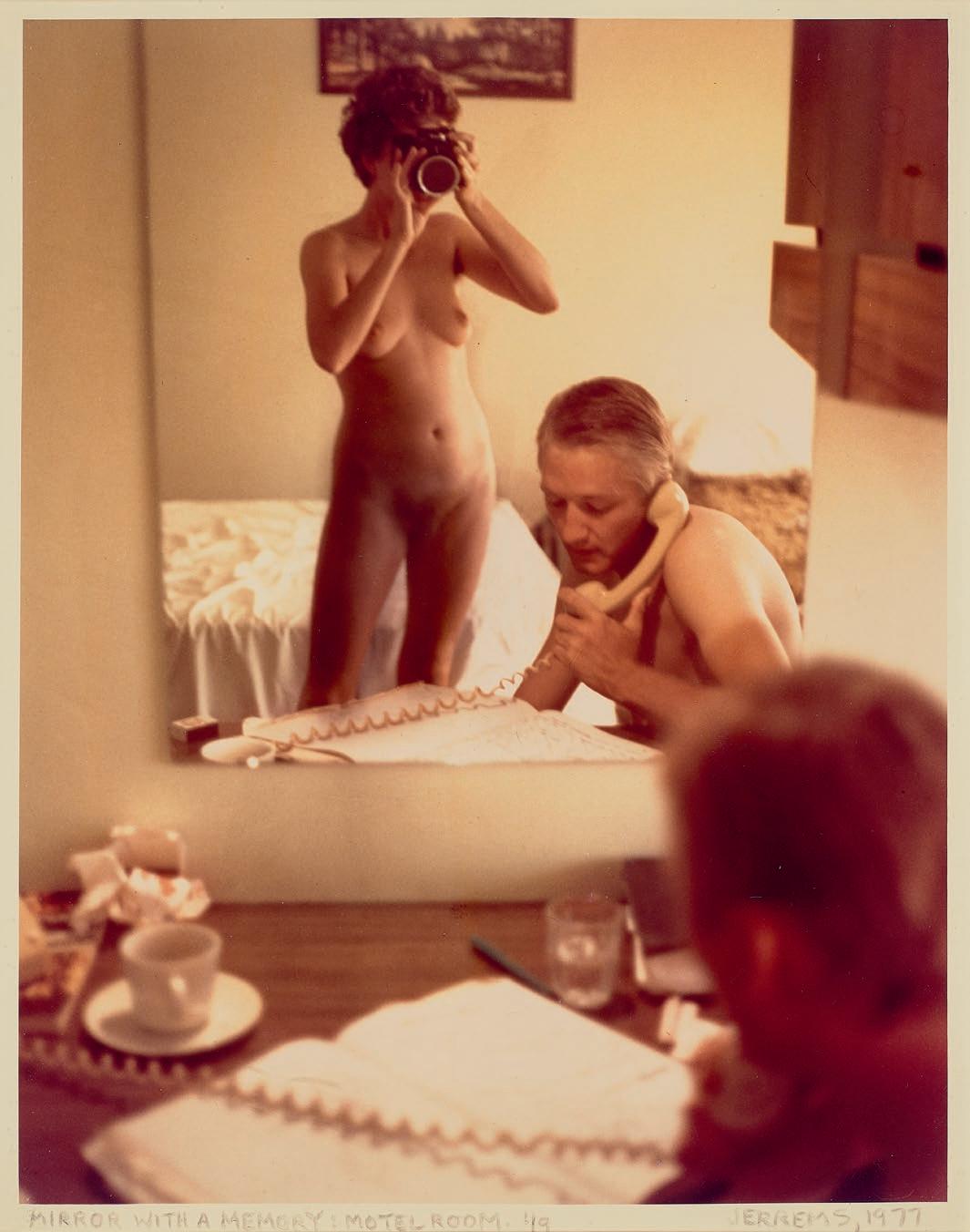

JOHN BRACK (1920 – 1999)

SEATED NUDE WITH SCREEN, 1982 – 83 oil on canvas

130.0 x 97.0 cm

signed and dated lower left: John Brack 1982/3 inscribed with title on artist’s label attached verso: ‘SEATED NUDE WITH SCREEN’

ESTIMATE: $300,000 – 500,000

PROVENANCE

Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

Joan Clemenger AO and Peter Clemenger AO, Melbourne, acquired from the above in 1983

EXHIBITED

John Brack , Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, 21 May – 11 June 1983, cat. 9

John Brack: A Retrospective Exhibition, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 10 December 1987 – 31 January 1988, cat. 105

The Nude in the Art of John Brack, McClelland Sculpture Park and Gallery, Langwarrin, Victoria, 17 December 2006 – 25 March 2007, cat. 15

John Brack Retrospective , The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, 24 April – 9 August 2009, then touring to The Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2 October 2009 – 31 January 2010 (label attached verso)

LITERATURE

Lindsay, R., John Brack: A Retrospective Exhibition, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1987, pp. 73 (illus.), 134, 141

Grishin, S., The Art of John Brack , Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1990, vol. 1, p. 160, vol. 2, cat. o275, pp. 36, 171 (illus.)

Klepac, L., Australian Painters of the Twentieth Century, Beagle Press, Sydney, 2000, p. 168 (illus.)

Lindsay, R., The Nude in the Art of John Brack, McClelland Sculpture Park and Gallery, Langwarrin, 2006 (illus., n.p.)

Grant, K., John Brack , National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2009, pp. 187 (illus.), 225

Like all artists of his generation, John Brack was well-versed in the history of Western art and it remained an essential touchstone throughout his career. A survey of his painting reveals references to significant historical works by artists as diverse as Boucher, Seurat and Buffet, which provided inspiration as he borrowed from earlier masters and challenge as he pitted himself against them. His iconic painting, The bar, 1954 (National Gallery of Victoria), for example, appropriates both the subject and composition of É douard Manet’s famous depiction of A bar at the Folies-Berg è re, 1882 (Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London). In Brack’s characteristic way however, the PostImpressionist’s clever visual trick of depicting the scene in front of the barmaid reflected in a mirror is used to describe the subject as he witnessed it in 1950s Melbourne – a drab image of dour-faced workers who are urgently drinking their fill before the imminent early closing of the pub rather than the gay opulence of 1880s Paris.

Working within the traditional genres of painting, Brack explored the still-life, portraiture and the nude in his art. Landscape as a theme however, is largely absent from his oeuvre, and indeed, when his friend and fellow artist, Fred Williams, announced that he intended to make the Australian landscape the focus of his art, Brack was sceptical, doubting its relevance as a subject for contemporary painting. Always underlying Brack’s approach – and explaining his avoidance of landscape as a subject – was an enduring interest in the human condition. As he said,

‘What I paint most is what interests me most, that is, people; the Human Condition, in particular the effect on appearance of environment and behaviour… A large part of the motive… is the desire to understand, and if possible, to illuminate… My material is what lies nearest to hand, the people and the things I know best.’1

In the context of the nude, Brack described this focus on human nature in the following way: ‘When I paint a woman… I am not interested in how she looks sitting in the studio, but in how she looks at all times, in all lights, what she looked like before and what she is going to look like, what she thinks, hopes, believes, and dreams. The way the light falls and casts its shadows is merely… a hindrance unless it helps me to show these things.’ 2 Embarking on his first sustained series of paintings of the nude during the mid-1950s, Brack sought to test the development of his work through a return to the rigour and discipline of life drawing and placed an advertisement for a model in the newspaper. Questions about how he might make a new and meaningful contribution to the genre were answered by the single response he received, from a thin middle-aged woman whose appearance demanded a radically different approach that was far removed from the sensual nudes of earlier artists such as Rubens and Gauguin. Brack quickly realised that ‘there is absolutely nothing whatsoever erotic in an artist’s model unclothed in a suburban empty room’ 3 , and produced a series of striking paintings including Nude in an armchair, 1957 (National Gallery of Victoria) and

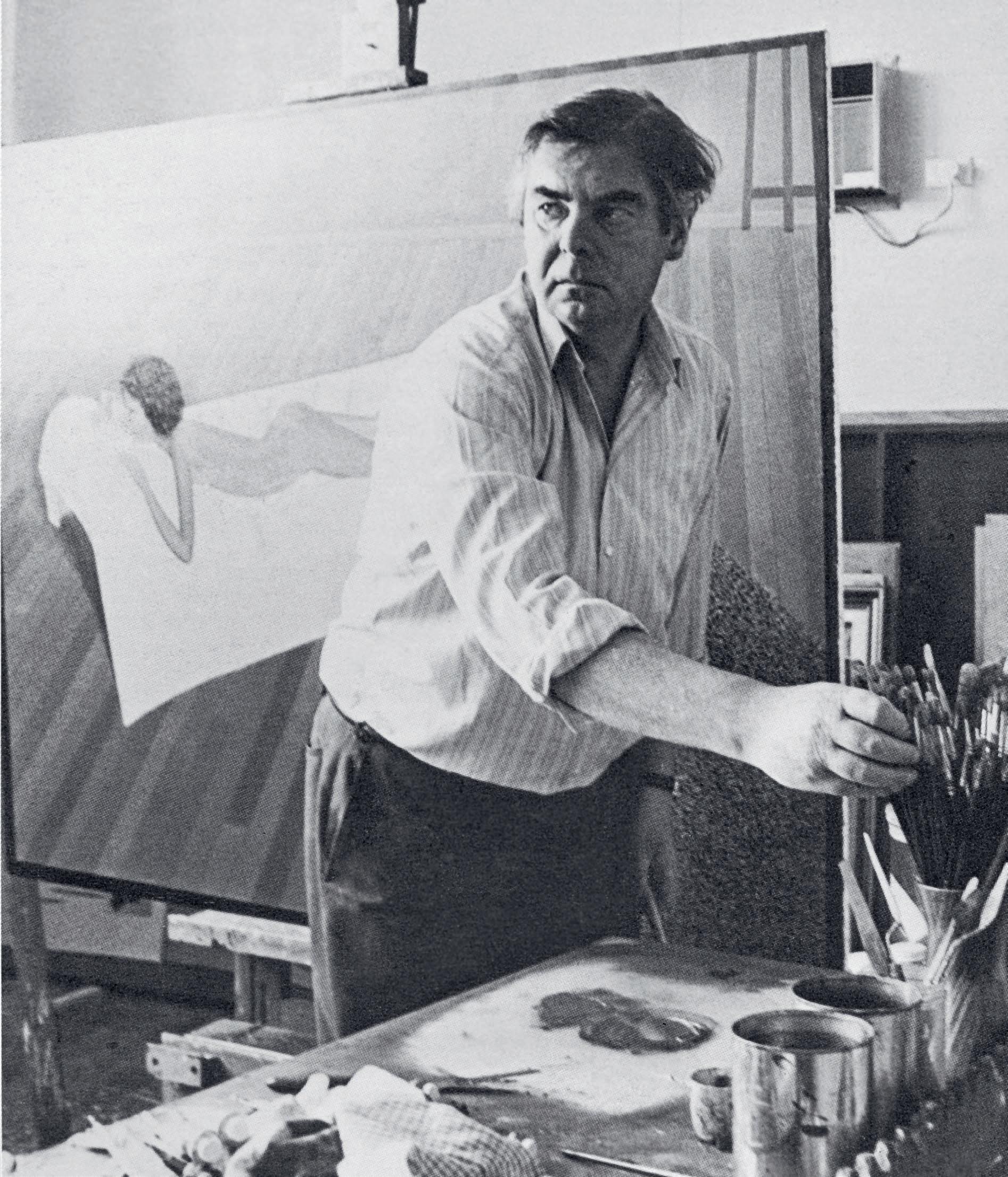

Opposite: John Brack in his studio with easel and paint completing ‘Nude on shag rug 1976 – 77’, February 1977 photographer unknown

The bathroom, 1957 (National Gallery of Australia), that boldly challenged expectations of the subject. While some lamented the skinny, sexless appearance of the model, art critic Alan McCulloch wrote that in pitting himself against tradition Brack had successfully demonstrated that ‘he [was] on all occasions master of the medium.’4

The nude returned as a major subject within Brack’s oeuvre during the 1970s and 80s and in these works a restrained sensuality and pleasure in depicting the female form is apparent. The contrast between the uncomfortable tension of the 1950s nudes and paintings like Seated nude with screen, 1982 – 83, where the subject looks out at the viewer completely at ease with her nakedness, seems to reflect the changes in social mores that had taken place in the intervening years and the increased informality of the late twentieth century. These differences might also point to the development of Brack’s own confidence and

artistic maturity. In the mid-1950s he was at the beginning of his career with a handful of solo exhibitions to his name, still defining his visual language and establishing his artistic persona. In 1968, with the help of a monthly stipend from his Sydney dealer Rudy Komon, Brack had resigned from his position as Head of the National Gallery School in Melbourne and for the first time in his life was able to paint fulltime. The ensuing decades witnessed regular solo exhibitions, private commissions, as well as other public affirmations of his art.

Like all of the nudes from this time, Seated nude with screen was painted in Brack’s studio and features its distinctive timber floorboards and unadorned walls, as well as a Persian carpet, which is rendered in characteristically intricate detail. Helen Brack interprets these carpets as symbolising the world of men and in the context of images where the subject is always female, this has a particular relevance. 5 In addition to

Installation photograph from the retrospective John Brack , held at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne, 2009

highlighting what the artist perceived as the differences between the sexes, this pictorial device also illustrates the counterbalance they provide each other.6 In this painting, the centrally-placed figure is prominent within the composition, and the all-over pale tone of her bare skin contrasts with the dark colours and decorative detail of the carpet. Brack has also paid particular attention to the model’s hair, carefully describing its elaborate braiding and the bun that is neatly coiled on top of her head. The model’s clothing often features in these paintings, discarded and casually draped nearby. Here, the figure’s overcoat – presumably hanging on a hook which is attached to the folded screen in the background – assumes a strangely anthropomorphic character and suggests the presence of another figure in the room. What ultimately prevails in this painting however, is what Patrick McCaughey astutely described as Brack’s ‘paramount… sense of observed reality.’ 7

Joan and Peter Clemenger purchased this painting from Brack’s 1983 exhibition at Tolarno Galleries in Melbourne and, apart from being displayed in several subsequent museum exhibitions –including both the 1987 and 2009 retrospectives at the National Gallery of Victoria – it has graced the walls of their home ever since. 8

1. Brack cited in Reed, J., New Painting 1952 – 62, Longman, Melbourne, 1963, p. 19

2. Brack, H., ‘This Oeuvre – The Work Itself’, in Grant, K., John Brack , National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2009, p. 16

3. Brack, J., Interview, Australian Contemporary Art Archive, no. 1, Deakin University Media Production, 1980, transcript, p. 6

4. McCulloch, A., ‘Classical themes’, Herald, 13 November 1957, p. 29

5. See Lindsay, R., The Nude in the Art of John Brack, McClelland Sculpture Park and Gallery, Langwarrin, 2007, unpaginated

6. See Helen Brack cited in Gott, T., A Question of Balance: John Brack 1974 – 1994, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Bulleen, 2000, p. 23

7. McCaughey, P., ‘The Complexity of John Brack’ in Lindsay, R., John Brack , National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1987, p. 9

8. See exhibition history noted above in the caption for this lot.

KIRSTY GRANT

John Brack

The bathroom, 1957 oil on canvas

129.4 x 81.2 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra © Helen Brack

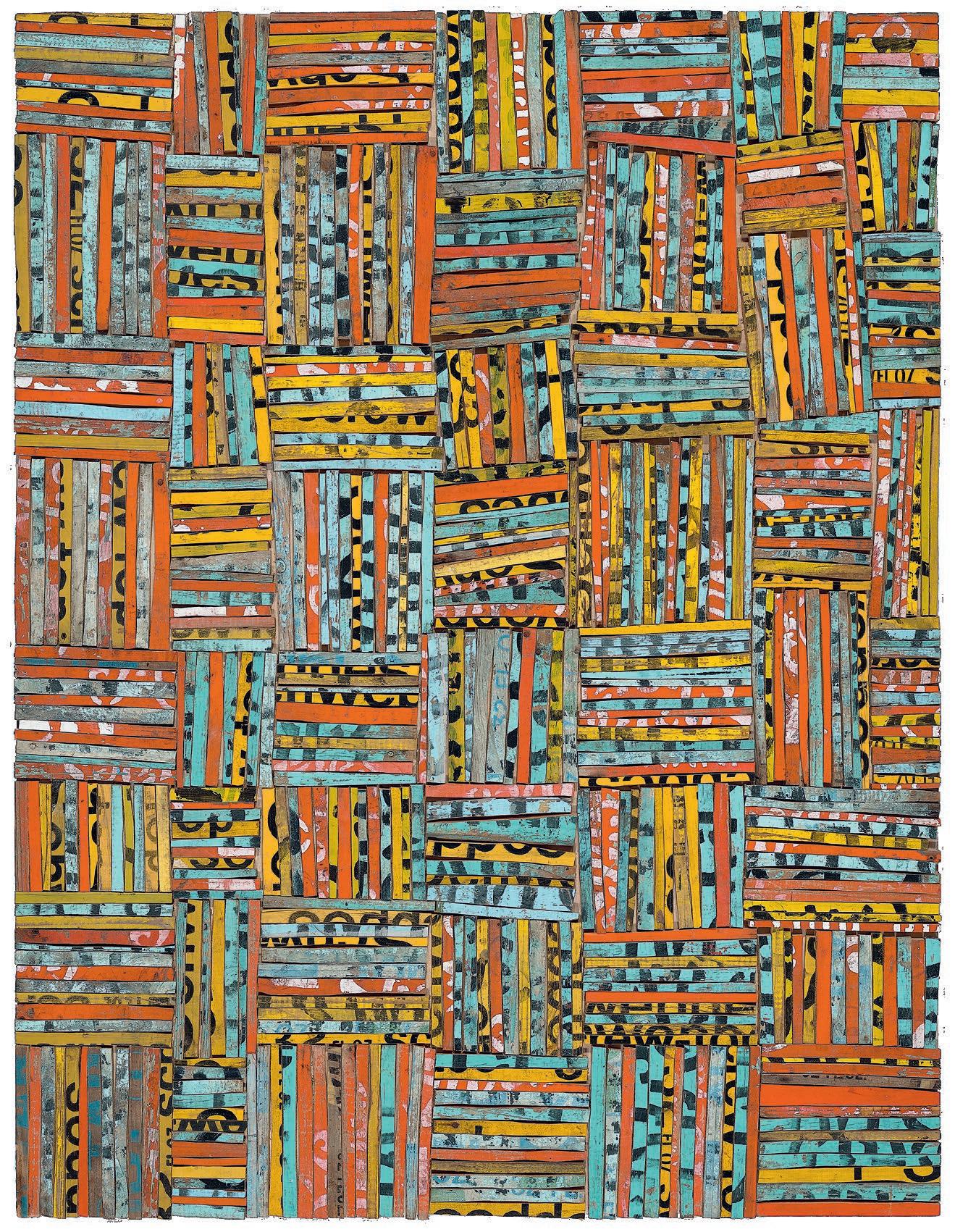

BRETT WHITELEY (1939 – 1992)

BIRD IN THE RAIN, 1984 painted and glazed earthenware with cobalt blue decoration and white glaze

53.0 cm (height) signed and dated on base: brett whiteley 84 monogrammed on base by potter John K Dellow: 84 JKD

ESTIMATE: $60,000 – 80,000

PROVENANCE

Private collection, Sydney Whiteley Estate, Sydney

Sotheby’s, Melbourne (private sale)

Joan Clemenger AO and Peter Clemenger AO, Melbourne, acquired from the above in 2011

EXHIBITED

An Exhibition by Brett Whiteley – Eden and Eve, Australian Galleries, Melbourne, 12 – 28 July 1984, cat. 52 [additional to catalogue] probably Animals and Birds , Brett Whiteley Studio, Sydney, 15 June – 16 October 2002

LITERATURE

Sutherland, K., Brett Whiteley: Catalogue Raisonné , Schwartz Publishing, Melbourne, 2020, cat. 95c, vol. 6, p. 79 (illus.), vol. 7, p. 866

Traditional blue-and-white painted ceramics constitute a little-known facet of Brett Whiteley’s artistic practice, despite consistently appearing within many of his most famous paintings of his Lavender Bay home alongside his personal collection of Asian and European blue-and-white ware. A technique only approached at the height of his career (from c.1974), collaboration with local potters provided Whiteley with unique and consistent three-dimensional supports for his sensuous ink-andwash still lives, landscapes and figure studies. The resulting elegant and life-affirming works were intimately linked to the rest of his oeuvre, both thematically and aesthetically.

This voluptuous balustre vase, Bird in the Rain, 1984 is amongst a handful of very large ceramic vessels, thrown by John K. Dellow and painted by Brett Whiteley in 1984. Combining many of Whiteley’s most iconic and optimistic motifs, it features, in rich and precious ultramarine pigment, an atmospheric scene of a speckled nesting bird in a tree, unfurling like a frieze around the wide shoulder of this vessel. The meandering painted lines of the tree and its wide leaves were then streaked with dark raindrops, the liquid pigment arrested mid-drip. Bird in the Rain, like all of Whiteley’s ceramics, is entirely

painted with ravishingly deep blue, applied in a range of saturations. This hue, described as his favourite colour, produced for Whiteley an ‘obsessive, ecstasy-like effect.’1

Between 1976 – 1982, Whiteley created a large body of ceramics with Derek Smith, a former teacher at East Sydney Technical College who had established Blackfriars Pottery in Chippendale. Following Smith’s move to Tasmania in 1982, Whiteley was referred to one of his students, Harriet Collard, who had a pottery studio in Leura. Inevitably, when Whiteley was confident enough to attempt larger works and required a potter with greater physical strength and a larger kiln, Collard handed him over to John Dellow who was also, at that time, living in the Blue Mountains. 2 It was within Dellow’s spacious pottery studio in the mountains in Katoomba, that the imposing Bird in the Rain was thrown, painted and glazed, a tandem between the artist and the potter. Although Whiteley collaborated with a succession of highly skilled commercial potters, the forms of the vessels they produced for him were unusual, with exaggerated silhouettes that suited the artist’s expressive and loose brushwork, in designs often mapped out in his notebooks, in pencil, ink or even collage.

The lyrical and serene composition of a small and alert bird, sitting steadfastly on her nest, balancing on a thick snaking branch has appeared throughout Whiteley’s oeuvre in many forms. From a rough and spare Sketch for Blue Vase , 1975, featuring a songbird sitting on a leafy branch adorning a wide baluster vase, to a plump pigeon sitting on a group of eggs, painted on the back of a large earthenware vase , Figure by the River, 1976, and of course painted and mixed media masterpieces such as The Wren, 1978; T’an, 1979; The Dove and The Moon, 1983, and Pink Dove , 1983. The poet Robert Gray perceptively reflected around the time of this vase’s execution, ‘…[Whiteley’s bird paintings] are to me his best work. I like in the bird-shapes that clarity; that classical, haptic shapeliness; that calm – those clear perfect lines of a Chinese vase. The breasts of his birds swell with the most attractive emotion in his work: it is bold, vulnerable and tender.’3

1. Brett Whiteley, cited in Krausmann, R., ‘Painting the infliction of life’, Aspect: Art and Literature, Sydney, 1975 – 76, p. 6

2. Correspondence between Kathie Sutherland and Harriet Collard, 29 February 2016, reproduced in Brett Whiteley: Catalogue Raisonné, Schwartz Publishing, Melbourne, 2020, vol. 6. p. 851

3. Gray, R., ‘A few takes on Brett Whiteley’, Art and Australia, Sydney, vol. 24, no. 2, 1986, p. 222

LUCIE REEVES-SMITH

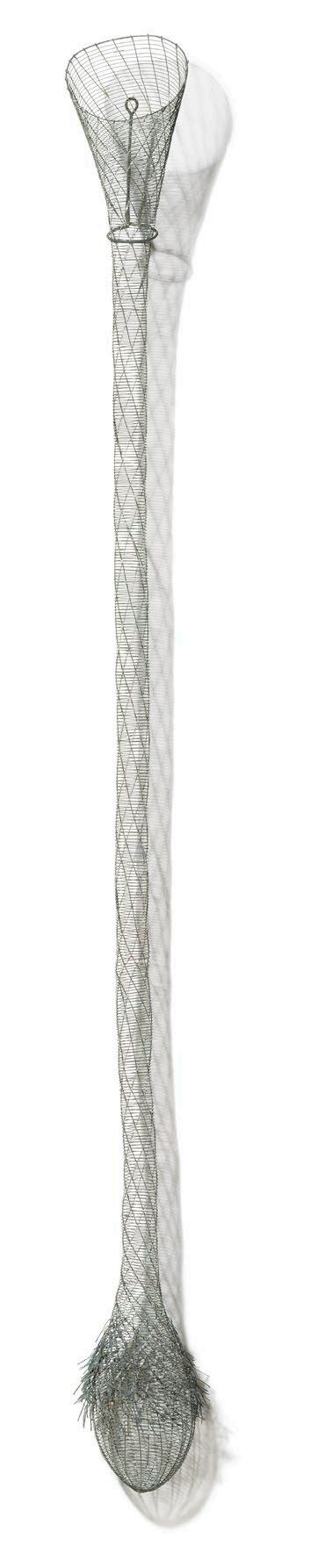

BRETT WHITELEY (1939 – 1992) WREN, 1988

(cast later by Meridian Foundry, Melbourne)

cast bronze, wire, glass eyes on a wooden stand

31.0 x 23.0 x 23.0 cm (bronze)

60.0 x 23.0 x 31.0 cm (overall, including base) edition: 9 + 2 AP

bears foundry stamp at base of bronze: BW AP 2–1 / E Ed

ESTIMATE: $120,000 – 160,000

PROVENANCE

Estate of the artist, Sydney Company collection, Sydney

EXHIBITED

Brett Whiteley: ‘Birds’, recent paintings, drawings, sculpture and one screenprint, Brett Whiteley Studio, Sydney, 5 – 19 July 1988, cat. 54 (another example)

Brett Whiteley: Art & Life , Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 16 September – 19 November 1995, cat. 144 (another example), then touring to: Museum and Art Galleries of the Northern Territory, Darwin, 13 December 1995 – 28 January 1996; Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, 22 February – 8 April 1996; Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 9 May – 16 June 1996; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2 July – 26 August 1996; Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, 18 September – 19 November 1996 (another example)

A Different Vision: Brett Whiteley Sculptures , Brett Whiteley Studio, Sydney, 4 April – 23 August 1998 (another example) Animals and Birds , Brett Whiteley Studio, Sydney, 15 June –6 October 2002 (another example)

Brett Whiteley: Sculpture and Ceramics , Brett Whiteley Studio, Sydney, 5 June – 6 December 2015 (another example)

LITERATURE

McGrath, S., Vogue Living, November 1988, p. 152 (illus., install photograph, another example)

Pearce, B., Brett Whiteley: Art & Life , Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1995, pl. 138, pp. 200 (illus., another example), 234 Sutherland, K., Brett Whiteley: Catalogue Raisonné: 1955 – 1992, Schwartz Publishing, Melbourne, 2019, cat. 72S, vol. 6, p. 197 (illus., another example), vol. 7, p. 896

‘People ask me – “Why paint birds?”, and I look at them dumbfounded. I’ve got no answer to it except that they’re the most beautiful creatures and I can’t think of a nicer theme – celebrative, heraldic theme – than birds.’1

Sculpture was an integral part of Brett Whiteley’s sprawling, diverse practice and he first introduced sculpture into his exhibitions in 1964 and 1965 with the intention of making a direct correlation between his work in two and three dimensions. 2 Across the course of his

career, sculptural elements burst from the picture plane, and threedimensional form was explored through the addition of real-life objects to his paintings (including branches, nests, eggs and taxidermised animals), in his collaborations in ceramics, and through stand-alone sculptural works. So important was the role of sculpture to Whiteley in his exhibitions that he would often borrow back privately owned works for inclusion, adamant that the exhibition would be less without them.

As Kathie Sutherland has revealed, Whiteley was not averse to writing ‘begging’ letters to a work’s owner pronouncing that the exhibition in question would be a ‘flop’ without the inclusion of the artist’s chosen sculptural centrepiece. 3

A version of Whiteley’s Wren, 1988, was first shown in the solo exhibition Brett Whiteley: ‘Birds’, recent paintings, drawings, sculpture and one screenprint , held at the artist’s Surry Hills studio in July 1988. True to Whiteley’s prodigious talent and ability to turn his hand to any material, this landmark show featured major works in all media, including the artist’s highly acclaimed bronze ‘Bird Sculptures’ of 1983 – 88, of which Wren is part. Presented during the year of his separation from his wife and muse Wendy Whiteley, the focus on birds in this exhibition also represented ‘a yearning at once for domestic stability and personal freedom.’4 Indeed, just as landscape provided Whiteley with ‘a means of escape, an unencumbered absorption into a painless, floating world’5 , so too these ornithological creatures embodied a declaration of love and limitless joy – with the symbolism of birds and eggs having fascinated the artist from childhood, as his sister Fran Hopkirk has observed.

Despite the weight of the bronze in which it is cast, Wren immediately captures the quirky hoppity movements of this beautiful small bird. Driven by the desire to convey personality rather than precisely replicate the animal’s physiology, Whiteley has abstracted the wren’s characteristic round form, streamlining its body, head and beak into a continuous line, as if the bird is caught mid-action, possibly capturing some food. This is a creature that the artist both knows well and has observed closely, its jaunty erect tail making it immediately identifiable as a wren, while its spindly legs convey a sense of both the bird’s fragility and its need of our protection and care.

1. Brett Whiteley, cited in Featherstone, D., Difficult Pleasure: A Film about Brett Whiteley, Film Finance Corporation Australia Limited, 1989

2. Sutherland, K., Brett Whiteley: Catalogue Raisonné, Schwartz Publishing, Melbourne, 2020, vol. 7, p. 5

3. ibid.

4. Grishin, S., Baldessin/Whiteley: Parallel Visions, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2018, p. 196

5. Brett Whiteley: Feathers and Flight, Brett Whiteley Studio, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 4 June 2020 – 28 March 2021, see https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/listen/ whiteley-feathers-flight/ (accessed 16 October 2024)

KELLY GELLATLY

BELLE–ÎLE. VILLAGE D’ENVAG

JOHN PETER RUSSELL (1858 – 1930)

[SUNSHINE SHIMMER], 1900 oil on canvas

65.0 x 81.0 cm

signed with initials lower centre: J.R. dated and inscribed with title verso: Sunshine Shimmer / August / B Isle 1900

ESTIMATE: $400,000 – 600,000

PROVENANCE

Estate of the artist, Brittany, France

Harald Alain Russell, the artist’s son, Brittany, France, inherited from the above c.1930

Thence by descent

Private collection, United Kingdom

EXHIBITED

John Peter Russell, Galerie G. Denis, Paris, 1941 / 1943 (?), cat. 11 (label attached verso, as ‘Belle-Isle. Village d’En-vag’)

On long term loan to Glasgow Museums & Art Galleries, Kelvingrove, Scotland, 1974 – 1991

LITERATURE

Galbally, A., The Art of John Peter Russell, Sun Books, Melbourne, 1977, cat. 158, p. 107 (as ‘Belle-Île. Village d’En-vag’)

Although he was born in Sydney, John Russell lived much of his adult life in Europe and holds a unique place within the history of Australian art for his close association with avant-garde circles in 1880s Paris and firsthand acquaintance with some of the masters of European Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Following studies at the Slade School, London in 1881, Russell attended Fernand Cormon’s atelier in Paris in the mid-1880s, working alongside Émile Bernard, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and later, Vincent van Gogh, with whom he established an enduring friendship.1 On a summer break from Paris in 1886, he spent several months on Belle- Î le, one of a group of small islands off the coast of Brittany which, buffeted by almost constant westerly winds blowing in from the Atlantic Ocean, is part of the accurately named La C ô te Sauvage. Captivated by the rugged landscape and the possibilities of this environment for his painting, Russell bought land there the following year. Writing to his friend, Tom

Roberts, he said, ‘I am about to build a house in France. Settle down for some five years. Get some work done. It will be in some out of the way corner as much as a desert as possible.’ 2

It was here that he met and befriended Claude Monet who he saw working en plein air and, recognising his painting style, famously introduced himself by asking if he was indeed ‘the Prince of the Impressionists’. Flattered, Monet, who was eighteen years Russell’s senior, took a liking to the young Australian and dined with him and his beautiful wife-to-be, Marianna, enjoying their hospitality and company during his stay on the island. Uncharacteristically, Monet allowed Russell to watch him work and on occasion, to paint alongside him, experiences that provided the younger artist with an extraordinary insight into the techniques and working method of one of the founders of the Impressionist movement. The influence on Russell was significant and the paintings he made

Gustave Loiseau

Le village d’Envag, 1900 oil on canvas

50.0 x 73.0 cm

Private collection

Belle-Île-en-Mer, Brittany, France

in Italy and Sicily only a few months later show him working in a new style, using a high-keyed palette (from which black had been banished entirely) and his compositions made up of strokes of pure colour. 3 In addition to showing him how to use colour as a means of expressing a personal response to the subject, Monet’s example also highlighted for Russell the importance of working directly from nature.4

Belle- Î le offered little in the way of obvious picturesque views but ‘instead … the challenge of a raw confrontation with nature for which there was no tradition of painterly representation.’5 Russell and Monet were not the only artists attracted by its creative possibilities. The roll call of artists who visited Russell and his wife – Fernand Cormon (1888); John Longstaff (1889); Dodge MacKnight (1889, 90, 91 and 92); Eugène Boch (1890); Bertram Mackennal (1891) and Auguste Rodin (1902) –is mirrored by those who came to paint on the island independently.

Henri Matisse first visited Belle- Î le in 1895 as a young art student, returning in 1896 and again the following summer. Of the island he said simply, ‘Here it is wildness in all its beauty and emptiness.’6 During an extended stay in 1896 he lived at the village of Kervilahouen on the south-western side of the island, near Russell’s house, and the two artists met. Russell introduced the young artist to Monet’s techniques and the work of van Gogh, contributing to a dramatic transformation in his approach to colour. Matisse’s biographer, Hilary Spurling, describes this as ‘a way of seeing: the first inklings of the pursuit of colour for its own sake that would draw in the end on his deepest emotional and imaginative resources.’7

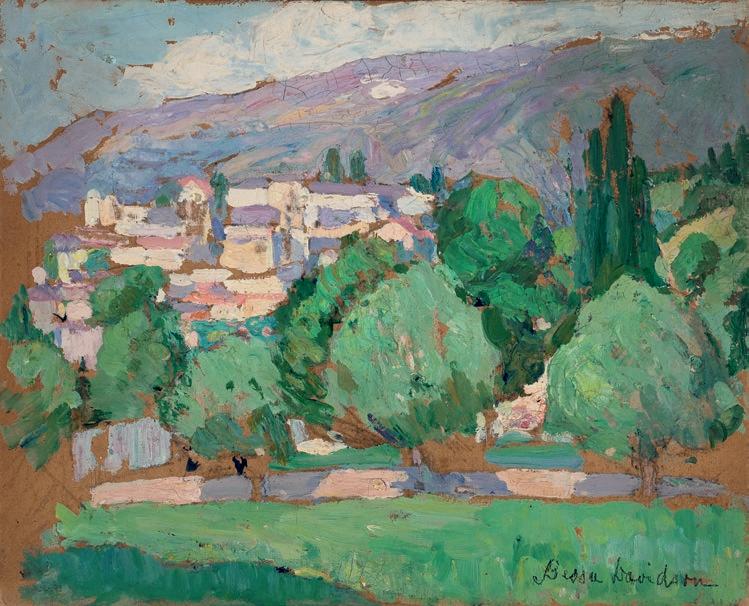

In Belle- Î le, Village d’Envag, 1900, it is the distinctive stone cottages of the island, specifically the nearby village of Envag, that have captured Russell’s attention. With a series of chimneys lined up in silhouette

65.5 x 93.0 cm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois

against a pale blue sky, the cottages are described in delicate shades of purple, blue and occasional pink and white highlights. Characteristically, the colour is built up in individual brushstrokes which shimmer with movement and light, communicating as much about the appearance of the scene as the feeling of being there. Russell varies the application of paint according to the subject, with regular, mostly horizontal strokes defining the geometric form of the buildings, and freer, more painterly daubs delineating the verdant foreground and atmospheric sky. This is an intimate scene, a local view, and located just north of Russell’s home – known to the locals as Château de l’Anglais – which overlooked the inlet of Goulphar, it was an area with which he was very familiar.

Russell scholar Ann Galbally explains the appeal of a rural lifestyle for many French artists during the late nineteenth century as ‘something that seemed to… be purer, simpler, and more fundamental’ than the

intensity of the artworld centre of Paris. 8 Citing, among others, van Gogh at Arles, Gauguin at Pont-Aven and Russell at Belle- Î le, she explains that ‘they were drawn … towards a primitive life style, a closer communication with nature, a chance, so they felt, to find the source of art.’ 9 In this context, paintings like Belle- Île, Village d’Envag sit alongside Russell’s images of local fishermen and other island inhabitants, celebrating the simplicity and authenticity of rural life. Monet had painted examples of vernacular architecture in Varengeville, a coastal town in Normandy, and the cottages of Belle- Île appealed to other artists who visited the island. Matisse, for example, focussed on buildings at nearby Kervilahouen which, in the work illustrated here, gleam a brilliant white against his bold colour palette. Probably having seen Monet’s paintings of Belle- Île, the Post-Impressionist, Gustave Loiseau, travelled there with friends and fellow artists Maxime Maufra and Henry Moret in 1900. It is not known whether Loiseau and Russell met at the time,

Claude Monet

Customs House at Varengeville , 1897

oil on canvas

Henri Matisse

Maisons à Kervilahouen, Belle-Île , 1896 oil on board

31.0 x 37.0 cm

Private collection

but the similarities between their paintings, both depicting the same area in Envag, make this a tantalising possibility. Russell paints from a position close to the cottages while Loiseau adopts a broader view – the varied perspectives, perhaps, of a local, more interested in capturing an impression of a familiar subject, versus a visitor, who paints the entirety of the scene as a way of recording it. Loiseau’s painting also includes figures walking on the path and close inspection of Belle- Î le, Village d’Envag reveals a solitary figure sketched in pencil on the path as it forks to the right. A label attached to the back of the painting shows that it was exhibited in an exhibition at Galerie G. Denis, Paris in the 1940s, and Russell obviously regarded it as finished, so just when and why the sketch was added remains a mystery.

1. Although Russell did not see van Gogh again after he departed for Arles in the south of France in early 1888, their friendship continued via correspondence. See Galbally, A., A Remarkable Friendship: Vincent van Gogh and John Peter Russell, The Miegunyah Press, Carlton, 2008

2. Russell to Tom Roberts, 5 October 1887, cited in Tunnicliffe, W., (ed.), John Russell: Australia’s French Impressionist, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2018, p. 193

3. Taylor, E., ‘John Russell and friends: Roberts, Monet, van Gogh, Matisse, Rodin’, Australian Impressionists in France, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2013, p. 60

4. Prunster, U., ‘Painting Belle- Île’ in Prunster, U., et al., Belle- Île: Monet, Russell and Matisse, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2001, p. 31

5. Galbally, A., ‘Mer Sauvage’ in Prunster, ibid., p. 14

6. Prunster, op. cit., p. 37

7. Spurling, H., The Unknown Matisse: A Life of Henri Matisse, Volume One: 1869 – 1908 , Hamish Hamilton, London, 1998, p. 144, cited in Taylor, op. cit., p. 65

8. Galbally, A., The Art of John Peter Russell, Sun Books, Melbourne, 1977, p. 45

9. ibid.

KIRSTY GRANT

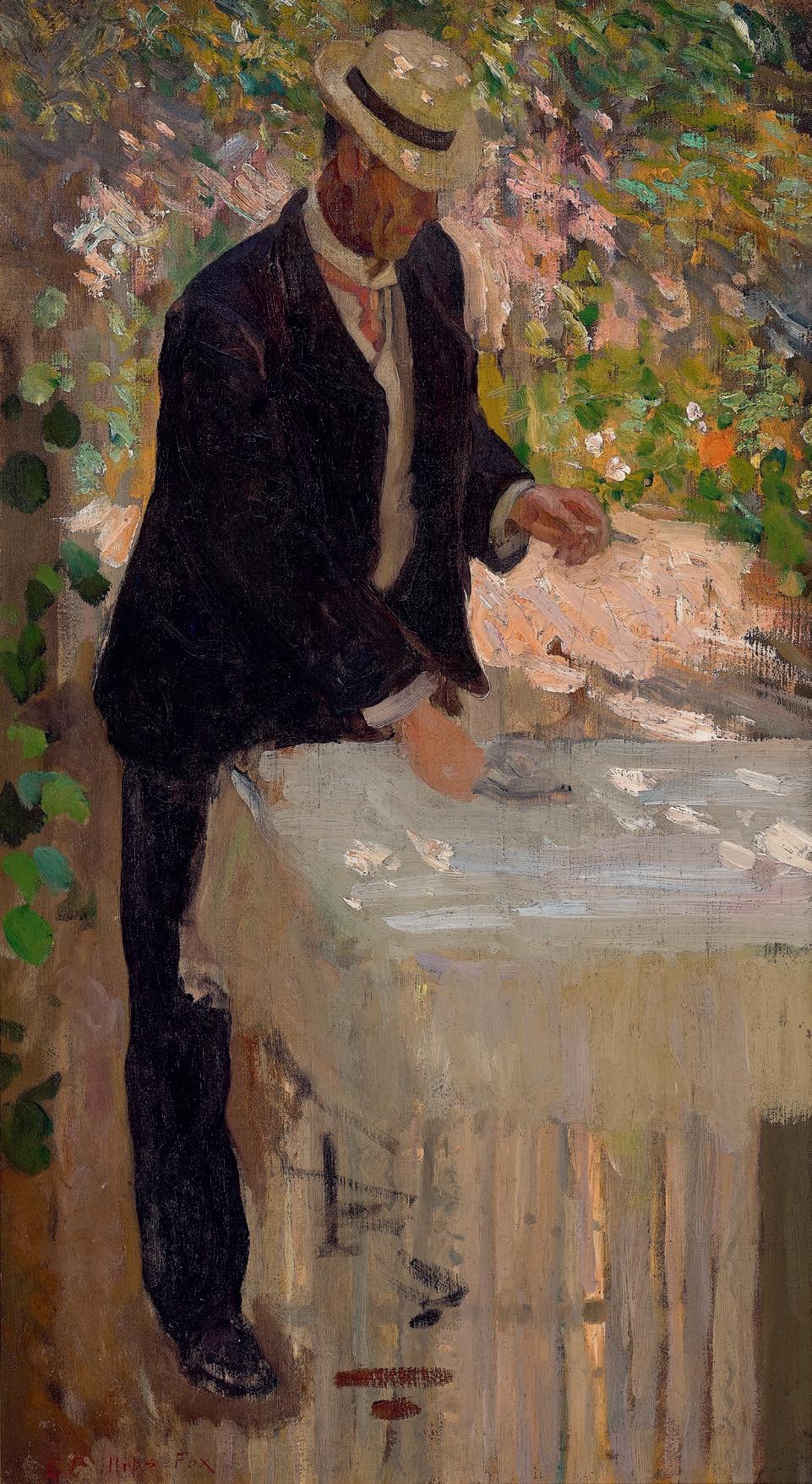

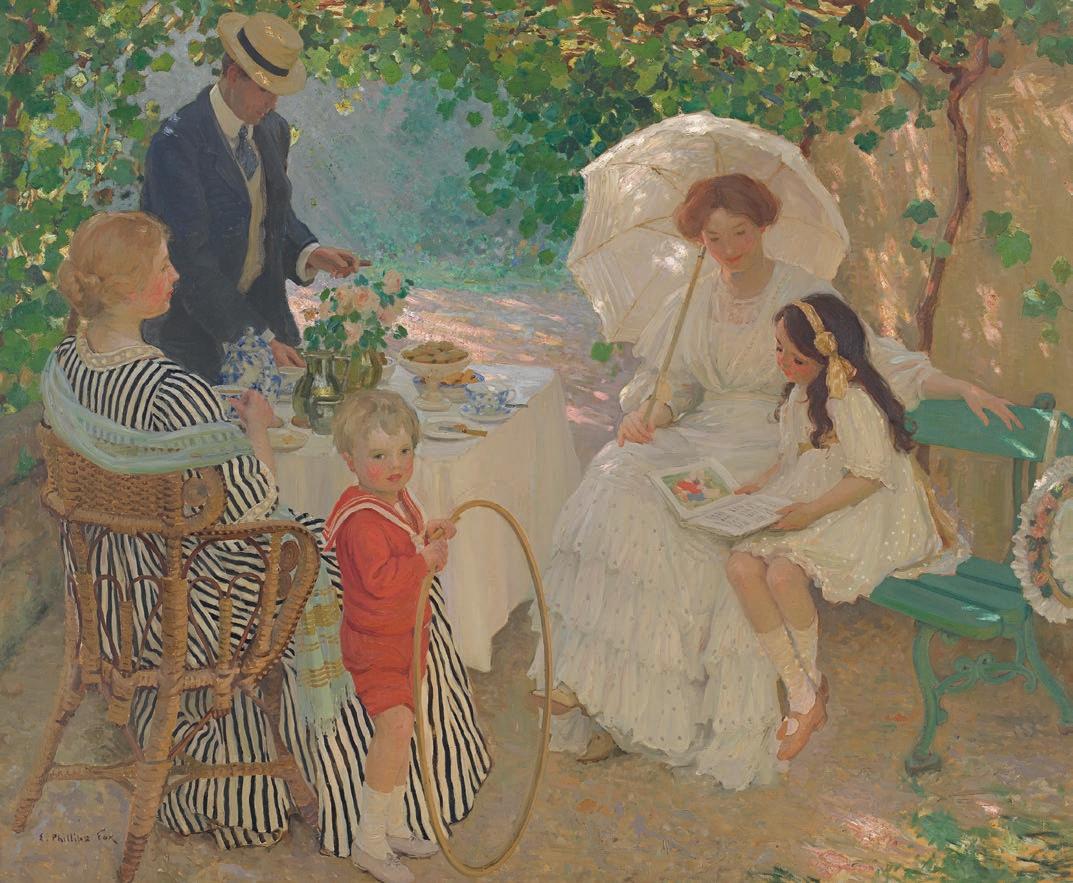

EMANUEL PHILLIPS FOX (1865 – 1915)

FIGURE STUDY FOR THE ARBOUR, c .1909 – 10 oil on canvas

74.0 x 40.5 cm

signed lower left: E Pillips Fox [sic]

ESTIMATE: $200,000 – 300,000

PROVENANCE

Private collection, Brisbane

Sotheby’s, Melbourne, 25 August 1997, lot 260 (as ‘The Waiter’)

Private collection, Melbourne

Deutscher~Menzies, Melbourne, 25 April 1999, lot 67A

Private collection, Melbourne

Deutscher~Menzies, Melbourne, 20 August 2001, lot 47

Private collection, Tasmania

Deutscher and Hackett, Melbourne, (private sale)

Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in 2016

EXHIBITED

E. Phillips Fox and Ethel Carrick Fox, Deutscher Fine Art, Melbourne, 13 November – 6 December 1997, cat. 16 (illus. in exhibition catalogue, p. 21)

LITERATURE

Zubans, R., E. Phillips Fox: His Life and Art, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 1995, cat. 322, pp. 27, 225 (as ‘The Waiter’)

RELATED WORK

The Arbour, 1910, oil on canvas, 190.5 x 230.5 cm, in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Emanuel Phillips Fox

The Arbour, 1910 oil on canvas

190.5 x 230.5 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Colour and the varied effects of light were central to the art of Emanuel Phillips Fox. Indeed, as Lionel Lindsay recalled, ‘He once told me that he no longer saw anything except as a colour-sensation… His gamut of greens is extraordinary fine and varied, and the purity of his colour still holds the sunlight imprisoned in the pigment.’1 While he had been trained in an academic style, Fox always enjoyed the freedom of working outdoors, and the influence of French Impressionism – particularly as articulated by Monet and Renoir, whose work was easily accessible during Fox’s years in Paris – encouraged this, feeding in to what has been described as his natural ‘inclination towards colour, light and optical experience.’ 2

The influence of Monet and Renoir is also apparent in the so-called déjeuner paintings that Fox made in the early twentieth century – Al Fresco , c.1905 (Art Gallery of South Australia); The Arbour, 1910

(National Gallery of Victoria); and Déjeuner, c.1910 – 11 (University of Queensland Art Museum) – each of which depict family groups gathered around a meal in intimate outdoor settings. As Fox scholar, Ruth Zubans, observed, ‘In style there are considerable differences… [but] in attitude… the mood of optimism, easy sociability and warm humanity are qualities shared by the artists.’3

Fox’s working method typically involved the production of numerous studies and the largest of these three paintings, The Arbour, was no exception to this practice. In addition to quick compositional sketches in pencil and charcoal which show him experimenting with the placement of figures and refining the depiction of particular subjects, Fox produced a series of more detailed studies in oil. An earlier small head study of the artist’s nephew, Leonard (Len), for example, which was made in 1908 during the artist’s extended stay in Melbourne, served as the basis for

Emanuel Phillips Fox Al fresco, c.1904 oil on canvas

153.5 x 195.5 cm

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

the boy in red and the young girl is thought to be modelled on his sister, Louise.4 While the identity of the adult sitters is not clear, given this focus on family it is possible that they are based on the artist’s wife, Ethel Carrick Fox – also a noted artist – and the children’s parents, Fox’s brother David and his wife Irene.

Depicting a standing man, stylishly attired and cigar in hand, this painting is the largest study known to have been made for The Arbour and although it was previously referred to as The Waiter, it is clear that the figure is a member of this intimate party rather than staff. Fox describes the details of his clothing, pose and attitude, most of which are transcribed with little variation to the final painting, and his focus on the representation of colour and light – and unrivalled ability to describe in paint the effect of dappled light shining through foliage – is also on full display. While much of this painting is ‘finished’, aspects

of it have a work-in-progress quality that imbues it with a freshness and palpable sense of energy. Here, brushstrokes communicate not only the physical making of the painting but something of the thinking involved in its creation.

1. Lindsay, L., ‘E. Phillips Fox’, Art in Australia, series 1, number 5, 1918, cited in Zubans, R., E. Phillips Fox, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1994, p. 1

2. Zubans, ibid., p. 3

3. Zubans, R., E. Phillips Fox: His Life and Art, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 1995, p. 126

4. Fox, L., E. Phillips Fox and his family, self-published, Potts Point, 1985, p. 68

KIRSTY GRANT

ARTHUR STREETON (1867 – 1943)

CEDAR TREE, COOMBE BANK, 1913 oil on canvas

76.5 x 63.5 cm

signed with initials lower left: AS. bears inscription verso: A. STREETON

ESTIMATE: $90,000 – 120,000

PROVENANCE

Sir Robert Mond, Coombe Bank, United Kingdom

Nevill Keating Pictures, London

Private collection, Melbourne

Sotheby’s, Melbourne, 22 April 1996, lot 14

Henry Krongold, Melbourne

Thence by descent

Private collection, Melbourne

RELATED WORK

The lake, Coombe Banks, 1913, oil on canvas, 64.0 x 102.0 cm, in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Arthur Streeton first lived in London between 1897 and 1906 but struggled to make an impression. For some years, he wooed the ‘brilliant, educated, successful, socially experienced and wellconnected Canadian-born violinist Esther Leonora (Nora) Clench’1, but his comparative status as an impoverished artist weighed heavily on his mind. Knowing that he still had a larger profile in Australia –indeed, a number of his early works were already attracting large sums at re-sale – Streeton decided to return briefly in late 1906, holding financially successful exhibitions in Melbourne and Sydney. Sufficiently emboldened, he returned to his now-fiancé in London, and they were married in 1908. Part of the honeymoon was spent in Venice, and Streeton returned there for a painting expedition in September, where he ‘threw off his devotion to conscious art, and became absorbed again in truth of presentation.’ 2 Through his wife’s connections, he met Dr Ludwig Mond, whose chemical manufacturing business was famed in Europe. Mond was a major collector of art works, predominantly by historic European artists, but his ‘tastes were wide enough to encompass contemporary art, and Streeton was to find Ludwig Mond, and his sons Robert and Alfred, a valuable source of patronage over the years to come.’ 3 Indeed, the Monds’ purchased one of Streeton’s paintings of Venice’s Grand Canal in 1909, and the artist’s son was christened Charles Ludwig Oliver Streeton in honour of their patron and friend. In 1912, Streeton ‘joined a party led by the painter Sigismund

Goetze, to travel down the Loire. Nora had been instrumental in Streeton’s involvement with Goetze, who was married to Ludwig Mond’s sister, Violet.’4

Over Easter the following year, Streeton, Nora, Oliver and his nanny stayed at the Monds’ home Coombe Bank in Sevenoaks, Kent. Built in 1725 for the Duke of Argyle, Coombe Bank is a Palladian-style villa sited near the River Darent with extensive acreages of forest including ‘a dozen or so old cedars and miles of park.’ 5 Ludwig Mond purchased the property in 1906 but on his death in 1909, it passed to son Robert who carried out extensive alterations to the gardens, building a rockery and a formal rose garden. Streeton wrote vividly of the days and evenings there filled with ‘billiards, golf, fishing, shooting, ‘music’, peaches and grapes – nothing wanting.’6 It also included a major commission from Mond to paint ‘a dozen landscapes of the place and surroundings to be hung in the house.’7 Cedar Tree, Coombe Bank , 1913, in particular, clearly expresses Streeton’s delight as he painted aspects that caught his eye. Rapidly executed, likely en plein air, the vigorous horizontal brush marks of the work convey the sweeping movement of branches caught by breezes on a gusty day. Likewise, the agitation inherent in the blustering clouds accentuates this sensation.

Other subjects featured in the sequence include a small play cottage known as the ‘Children’s house’, a stand of other cedars, and a substantial vista of the noble frontage of Coombe Bank with attendant mature trees. A further work, The lake, Coombe Banks , 1913, in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, features people boating on the southern side of the property – again surrounded by trees and foliage. All these paintings display the ‘truth of presentation’ Streeton had been striving for following Venice, particularly evident in the evocative spontaneity he captured in this painting.

1. Wehner, V., Arthur Streeton of Longacres: A Life in the Landscape, Mono Unlimited, Melbourne, 2008, p. 6

2. Lindsay, L., ‘Arthur Streeton’, in The Arthur Streeton Catalogue, Arthur Streeton, Melbourne, 1935, p. 16

3. See Wray, C., Arthur Streeton: Painter of Light, Jacaranda, Brisbane, 1993, pp. 116, 120

4. ibid., p. 122

5. Arthur Streeton, Letter to Walter Pring, 30 March 1913, cited in Galbally, A. and Gray, A. (eds.), Letters from Smike: The Letters of Arthur Streeton 1890 – 1943, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1989, p. 125

6. ibid.

7. ibid.

ANDREW GAYNOR

MARGARET PRESTON (1875 – 1963)

PINEAPPLE PALM, 1925 also known as STILL LIFE WITH PALM oil on canvas

56.5 x 45.5 cm

ESTIMATE: $120,000 – 160,000

PROVENANCE

Grosvenor Galleries, Sydney

Elioth Gruner, Sydney, acquired from the above in August 1929 with Grosvenor Galleries, Sydney, May 1940

Howard Hinton, Sydney, acquired from the above Lawson’s, Sydney

Private collection, Sydney, acquired from the above, c.1970

EXHIBITED

Margaret Preston, Grosvenor Galleries, Sydney, 7 – 31 August 1929, cat. 6

Elioth Gruner Exhibition by Request of the Perpetual Trustee Co (Limited), Grosvenor Galleries, Sydney, 8 – 31 May 1940, no. 17 (as ‘Still life with Palm’)

Margaret Preston in Mosman, Mosman Art Gallery, Sydney, 7 September – 13 October 2002

LITERATURE

Butler, R., The Prints of Margaret Preston: A Catalogue Raisonné , National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1987, p. 311

Margaret Preston Catalogue Raisonné of paintings, monotypes and ceramics , Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2005, CD-ROM compiled by Mimmocchi, D., with Edwards, D., and Peel, R., cat. 1925.14 (illus.)

Margaret Preston Strelitzia, 1925 oil on canvas

45.7 x 53.9 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

© Margaret Preston/Copyright Agency 2024

By 1925, when Pineapple Palm was painted, Margaret Preston’s long years of training and thought began to coalesce in her pursuit of a truly national Australian art. Ever the straight-talking pragmatist, she was wise enough to realise that this would be no overnight undertaking and instead set herself gradual exercises to reach her goal. Each was a finished work unto itself, but each was also an experiment analysing an aspect of her pursuit. In the words of her great supporter Sydney Ure Smith, publisher of Art in Australia, Preston was ‘the natural enemy of the dull,’1 an artist whose ‘refusal to repeat herself was because she had acquired a single aim which she knew had to be approached in stages – namely the discovery of forms which would eventually become the basis for an Australian natural art.’2 Taking her cues from Aboriginal design, modernist flattened abstraction, and Japanese art, she used still life as her ‘laboratory table’, a controlled space ‘on which aesthetic problems can be solved.’3

Preston had a rigorous traditional art training undertaken variously at the National Gallery School, Melbourne; the Munich Government School for Women; and at private academies in Paris and London. She slowly became attuned to the theoretical ideas underpinning the paintings of Paul Cézanne and took further inspiration from the Fernand Léger’s mechanised evocations of the modern world. Moreover, from her concurrent study of Japanese printmaking, Preston intuited these modern masters’ emphasis on shallow space and abrupt angles of view. However, her overarching inspiration was the art of Australia’s Indigenous population, whose pared-back symbols and aerial perspectives – so Preston believed – were the essential anchor for any art that attempted to express an authentically Australian identity. This understanding was outlined in her article ‘The Indigenous art of Australia’ published in Art in Australia in March 1925.4 Unfortunately, like most of Australia in those years, Preston neglected to inform herself of the deep spiritual attachment that the Indigenous have for their art, and her appropriations and experiments may jar with contemporary thought.

Margaret Preston

The Potted Plant , 1925 oil on canvas

42.1 x 42.4 cm

Benalla Art Gallery, Victoria, Ledger Gift in 1975

© Margaret Preston/Copyright Agency 2024

Pineapple Palm is, at first glance, an austere arrangement of draped fabric, flowerpots, the palm itself and a semi-obscured window – a partial view in the Japanese manner – but closer examination reveals the painting’s deliberate complexities. Preston takes obvious delight in the juxtaposition of the pineapple’s angular form and textural skin (surely a fruit designed solely for modernist art) set against an exotic floral fabric, likely one designed by Paul Poiret or Raoul Dufy, and imported by the David Jones’ store in 1924, with Preston enlisted to arrange their display. Apart from these blooms, the rest of the image incorporates muted, earthy colours akin to those utilised by Indigenous artists, and by tilting the table’s surface, she effectively reduces the space to a shallow plane. Notably, Pineapple Palm was first owned by Preston’s esteemed artist colleague Elioth Gruner 5 , and of the modest total of paintings known from 1925, a number are now part of respected institutional and corporate collections including Still life and Study in white (both National Gallery of Australia); Strelitzia (National Gallery

of Victoria); Pink Hibiscus (Wesfarmers); The Potted Plant (Ledger Collection, Benalla Gallery); and White and Red Hibiscus (Art Gallery of South Australia).

1. Ure Smith, S., ‘Editorial’, Art in Australia, Margaret Preston Number, 3rd series, no. 22, Art in Australia Ltd., Sydney, December 1927

2. McQueen, H., ‘Margaret Rose Preston – an enemy of the dull’, National U, Canberra, 13 June 1977, p. 23

3. Preston, M., ‘Aphorism 46’, in Gellert, L. and Ure Smith, S. (eds), Margaret Preston: Recent Paintings 1929, Art in Australia Ltd., Sydney, 1929

4. Preston, M., ‘The Indigenous art of Australia’, Art in Australia, 3rd series, no. 11, Art in Australia Ltd., Sydney, March 1925, n.p.

5. Other art colleagues who collected Preston’s paintings included Leon Gellert, Sydney Ure Smith, Lionel Lindsay, George Lambert, Thea Proctor and Adrian Feint.

ANDREW GAYNOR

CLARICE BECKETT

(1887 – 1935)

MARIGOLDS, c .1925

oil on board

40.5 x 30.5 cm

signed lower right: C. Beckett bears inscription verso: Clarice Becket [sic] / 10 Guineas

ESTIMATE: $35,000 – 45,000

PROVENANCE

Grace Seymour, Melbourne c.1930s, acquired directly from the artist Thence by descent Private collection, Melbourne Deutscher~Menzies, Melbourne, 21 August 2001, lot 25 Private collection, Sydney, acquired from the above

RELATED WORK

Still Life (Marigolds), 1925, oil on board, 30.5 x 40.8 cm, in the collection of the Castlemaine Art Gallery and Historical Museum, Victoria, Maud Rowe Bequest 1937

We are grateful to Brenda Martin Thomas, wife of the late David Thomas AM, for kindly allowing us to reproduce David’s writing in this catalogue entry.

Still life subjects are well-suited to the art of Clarice Beckett as stillness was such a fundamental aspect of her painterly aesthetic. In her lifetime, paintings of flowers were notably favoured more than landscapes, and their bright colours always caught the eye of the viewer. Asters, carnations, roses, and petunias were the single and group subjects of numerous still life paintings exhibited in the spring and autumn exhibitions of the Victorian Artists’ Society in East Melbourne during the twenties. Her first solo exhibition in 1923 featured so many flower paintings that the review in the Sun News-Pictorial was headed ‘Vases and Flowers: Miss Beckett’s Art.’

‘Nearly 80 paintings by Miss Clarice Beckett were exhibited yesterday at the Athenaeum. There is one portrait; the rest are land or seascapes, and some effective still life studies. Daisies; and Mr Sherlock’s Asters, and a Japanese Vase show the artist at her best… Her work denotes a fine appreciation for natural beauty.’1

In her Memorial Exhibition held in May 1936 at the Athenaeum, Melbourne, flowers also played a significant role, The Wattle being a lone native among the camellias and chrysanthemums. Beckett’s champion, Rosalind Hollinrake, noted that, ‘Unlike her contemporaries Ellis Rowan and Margaret Preston, Beckett did not paint native flowers.’2 She acknowledged one exception, the painting titled Gladioli exhibited at the Victorian Artists’ Society in 1922, to which gum leaves had been added. ‘Her attitude to native flora’, Hollinrake continued, ‘was that the Australian bush was fragile despite its seeming hardiness and that bush flowers should be left where they belong.’3 Significantly, among the works unveiled in her Memorial show was a painting titled Marigolds, (cat. 25). Just one year later, the related painting, Still Life ( Marigolds), 1925, was bequeathed to the Castlemaine Art Gallery and Historical Museum, Victoria – thus becoming one of the first works by Beckett to enter a public collection. Today the painting remains widely acclaimed among the artist’s finest flower pieces, and is complemented by the slightly larger, Marigolds , c.1925 on offer here. If the Castlemaine version has a lighter setting, with a strikingly simple ground of subtle fawns and greys, the flowers contained in a green glazed Chinese ginger jar, the present work places more focus upon the colour burst of orange flowers – while still maintaining all the subtle interplay of the former. Both provide a tangible sense of the flowers’ presence through an aura of tone and ravishing colour, thus eloquently illustrating that Beckett’s understanding of beauty was not purely confined to landscapes.

1. Sun News-Pictorial, Melbourne, 5 June 1923, p. 9

2. Hollinrake, R., Clarice Beckett: Politically Incorrect, Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne, 1999, p. 16 3. ibid.

DAVID THOMAS

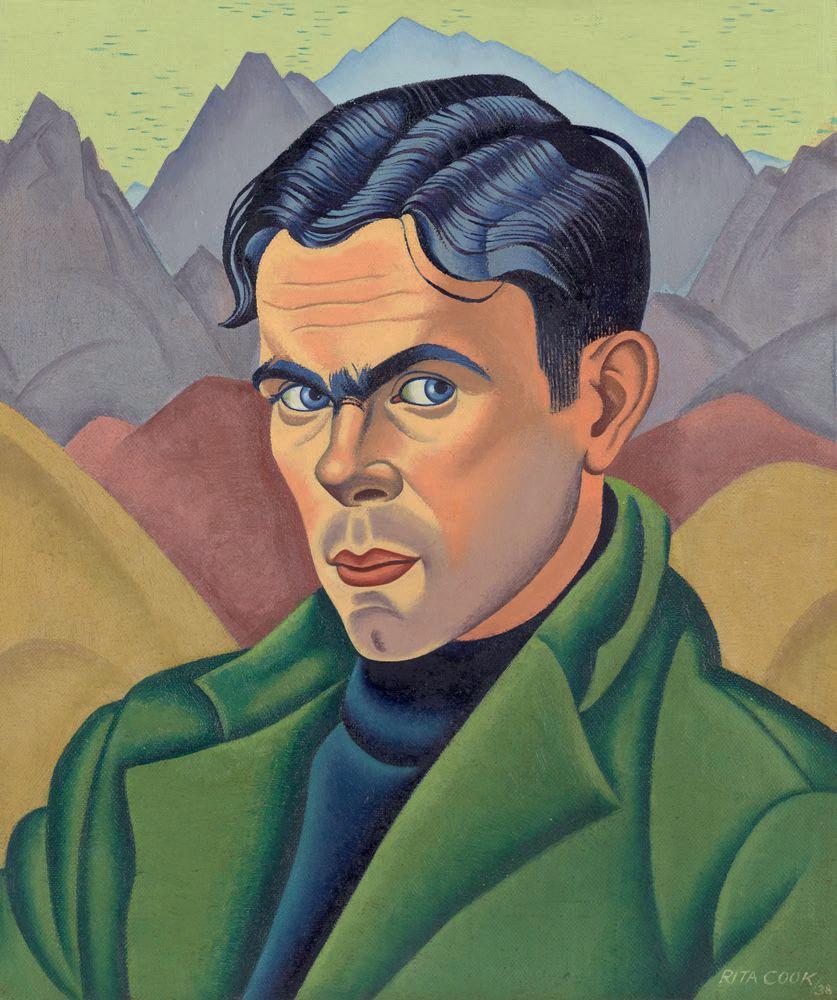

RITA ANGUS

(New Zealand, 1908 – 1970)

PORTRAIT OF O’DONNELL MOFFETT, c .1939 oil on canvas on cardboard

37.5 x 34.5 cm (image)

41.0 x 38.0 cm (frame)

ESTIMATE: $200,000 – 300,000

PROVENANCE

Valmai Moffett, Christchurch, New Zealand, commissioned from the artist

O’Donnell Moffett, New Zealand, a gift from the above

Thence by descent

Private collection, New Zealand

EXHIBITED

Gembox, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, New Zealand, 29 August – 15 November 2009

Bad Hair Day, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, New Zealand, 4 June 2016 – 28 May 2017

Faces from the Collection, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, New Zealand, May 2013 – September 2015

Ship Nails and Tail Feathers, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, New Zealand, 10 June – 23 October 2023 on long term loan to the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, New Zealand, 1998 – 2024

LITERATURE

Hall, K., ‘QUIET INVASION Faces from the Collection’, Bulletin, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, New Zealand, B.175, Autumn, March – May 2014, p. 31 (illus.)

Angus

Self-portrait , c.1937

oil on canvas on board

49.0 x 40.0 cm

Public Art Gallery, New Zealand

© The Estate of Rita Angus

Rita Angus painted this portrait of a young boy on the eve of the Second World War. Then in her early thirties, she had recently completed paintings such as Cass , 1936; Self-portrait, 1936 – 37; and Leo Bensemann, 1938, which are now celebrated in the art history of Aotearoa New Zealand. Living in Christchurch, then the country’s leading art centre, she was at the height of her powers and much admired by her artist contemporaries.

On a personal level, however, this was a challenging time for Angus. In March 1939, she quit her flat, unable to pay the rent, and for most of the year she stayed with friends, helping with childcare and household duties in return for board. As a committed pacifist she was deeply troubled by the escalating threat of war, but she was also beset by misfortune, including the death of a sister and the end of a long-term relationship. It was during this unsettled period that she painted Portrait of O’Donnell Moffett, c.1939.

95.5 x 67.0 cm

The portrait was commissioned by the subject’s mother – Angus’ friend, the cellist Valmai Moffett (née Livingstone). The two women, born a year apart, had known each other since the early 1930s and had much in common; both had married young and soon separated, and both were gifted artists, independent, unconventional and dedicated to their work. They were part of the same social circle in Christchurch, a group of innovative artists, musicians, writers and intellectuals who were linked through friendship, love affairs and marriage. Valmai attended parties at Rita’s studio in Cambridge Terrace, a hub for the local artworld, and she was painted and drawn by mutual artist friends. Today, Evelyn Page’s Portrait of Valmai Moffett , 1933 is one of the treasures of the Dunedin Public Art Gallery collection.

According to family history, Valmai commissioned Rita to make a pencil portrait of her son and was surprised to be presented with a more substantial work – an oil painting. Angus evidently wanted to do

Rita

Dunedin

Evelyn Page

Portrait of Valmai Moffett , 1933 oil on canvas

Dunedin Public Art Gallery, New Zealand

Rita Angus

Head of a Māori Boy, c.1938 oil on canvas on plywood

42.0 x 31.0 cm

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, New Zealand

© The Estate of Rita Angus

her best for her friend. She knew how much Valmai missed her tenyear-old son, who was based in Dunedin with his father at the time. Angus later referred to the portrait in a letter to a mutual friend, the composer Douglas Lilburn. ‘When I painted O’Donnell years ago as a commission, I asked the lowest amount I could, though in economic straits myself…’1 Angus, childless herself, was greatly drawn to children and took pleasure in depicting them all her life. Here, she presents us with an alert, wide-eyed boy, scrubbed and groomed for his portrait, his hair freshly combed and his jersey neatly buttoned. His irrepressible cowlick and unruly white collar contribute to the impression of barely contained vitality.

The portrait has affinities with another arresting image of a child – Head of a Māori Boy, c.1938, in the collection of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Both works show the crisp drawing, sharply delineated form

Rita Angus

Leo Bensemann, 1938 oil on canvas

30.0 x 35.5 cm

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington

© The Estate of Rita Angus

and brilliant light that are typical of Angus’ art, but the Moffett oil, an intimate and affectionate portrait, is more naturalistic. Its freshness and luminosity remind us that Angus had spent much of the past two years painting pristine watercolours of the Central Otago landscape.

Portrait of O’Donnell Moffett is a fine example of Angus’ work, and a testament to the friendship between two remarkable women, key figures in the lively Christchurch art world of the 1930s. Like most of Angus’ paintings it was never exhibited in her lifetime and has only come to public notice in recent years through exhibitions at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. Angus herself thought highly of it, telling Douglas Lilburn in 1946, ‘I’m glad I’ve painted this portrait for it’s good.’ 2

1. ‘Letter from Rita Angus to Douglas Lilburn’, 16 August 1946, Douglas Lilburn papers, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, MS-P-7623-61.

2. ibid.

JILL TREVELYAN

MARGARET OLLEY

(1923 – 2011)

HARBOUR VIEW, BOTTLEBRUSH AND KELIM, c .1999 oil on composition board

76.0 x 106.5 cm

signed lower right: Olley

ESTIMATE: $80,000 – 120,000

PROVENANCE

Nevill Keating Pictures, London

Private collection

Deutscher~Menzies, Sydney, 10 March 2004, lot 29

Private collection, UK, acquired from the above

EXHIBITED

Margaret Olley: Recent Paintings , Nevill Keating Pictures, London, 10 – 25 June 1999, cat. 1 (illus. on catalogue cover)

LITERATURE

Pearce, B., Margaret Olley, The Beagle Press, Sydney, 2012, pp. 169 (illus.), 262

‘…I can think of no other painter of the present time who orchestrates his or her themes with such richness as Margaret Olley. She is a symphonist among flower painters; a painter who calls upon the full resources of the modern palette to express her joy in the beauty of things.’1

A much-loved, vibrant personality of the Australian art world for over 60 years, Margaret Olley exerted an enduring influence not only as a remarkably talented artist, but as a nurturing mentor, inspirational muse and generous philanthropist. Awarded an Order of Australia in 1991 and a Companion of the Order of Australia in 2006, Olley featured as the subject of two Archibald-Prize winning portraits (the first by William Dobell in 1948, and the second by contemporary artist Ben Quilty in 2011, just prior to her death) and was honoured with over 90 solo exhibitions during her lifetime, including a major retrospective at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1997. Today her work is held in all major state and regional galleries in Australia, and the myriad contents of her Paddington studio have been immortalised in a permanent installation at the Tweed Regional Gallery in northern New South Wales, not far from where Olley was born. Bequeathing a legacy as bountiful as the subject matter of her paintings, indeed her achievements are difficult to overstate – and reach far beyond the irrepressible sense of joy her art still brings.

A striking example of the still-life and interior scenes for which Olley remains widely celebrated, Still Harbour View, Bottlebrush and Kelim, c.1999 wonderfully encapsulates the way in which she repeatedly turned to the quotidian for inspiration, excavating her domestic setting to uncover the beauty inherent in everyday life. While the majority of