AUCTION | MELBOURNE | 24 APRIL 2024

Significant works from the Collection of Joan and Peter Clemenger

Significant works from the collection of Joan Clemenger AO and Peter Clemenger AO, Melbourn e

Lots 6 – 8

1

John Brack

No More , 1984

John Brack

No More , 1984

WEDNESDAY 24 APRIL 2024

7:00 pm

105 commercial road south yarra, vic telephone: 03 9865 6333

TUESDAY 9 – SUNDAY 14 APRIL

36 gosbell street paddington, nsw telephone: 02 9287 0600

11:00 am – 6:00 pm

THURSDAY 18 – TUESDAY 23 APRIL

105 commercial road south yarra, vic telephone: 03 9865 6333 11:00 am – 6:00 pm

email bids to: info@deutscherandhackett.com telephone: 03 9865 6333 fax: 03 9865 6344

www.deutscherandhackett.com/watch-live-auction

3 3

sydney viewing melbourne viewing

bsentee/telephone

ive

melbourne auction a

bids l

online bidding

www.deutscherandhackett.com | info@deutscherandhackett.com

AUCTION | MELBOURNE | 24 APRIL 2024

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER 4

JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER, MELBOURNE

Joan and Peter Clemenger’s passion for art and generous philanthropy to the arts over many decades is all the more remarkable given that neither came from families with an interest in visiting galleries and collecting. This is something they developed together as a couple, and it has been one of the hallmarks of their extraordinary lifelong partnership. However, rather than focus exclusively on developing their own collection, the Clemengers made the visionary – and at the time, ground-breaking – decision to share their love of art and the enrichment it gave them, through philanthropy, and particularly through their support of the National Gallery of Victoria, a relationship that now extends over 40 years.

Joan and Peter met when Joan was working in the Collins Street studio of acclaimed Melbourne fashion and advertising photographer Athol Shmith, and the pair married in 1956. Peter had started working in advertising at the age of 16 and joined his father in establishing Clemenger Advertising just two years later. Today, Clemenger BBDO is the largest agency group in Australia. Not long after their marriage, Joan attended a Christie’s art appreciation course, which she loved. Visits to Melbourne’s small clutch of commercial galleries ensued, with Joan coming to know gallerists such as Joseph Brown, Max Hutchinson, Georges Mora, Anne Purves and Sweeney Reed.1 As Peter’s advertising business grew and he was increasingly required to travel overseas for work, their knowledge of art correspondingly expanded to include international modern and contemporary artists and dealers. In a story that has since become family lore, Joan once arrived at the reception of

New York’s Chase Manhattan Bank and requested to see the Bank’s art collection. Such was Joan’s courage, determination, and bravura, that no further questions were asked, and she was subsequently taken on a private tour by David Rockefeller (1915 – 2017), the Bank’s chairman and chief executive at the time. As Jason Smith has so aptly described Joan: ‘She had a twinkle in her eye, a ready smile, and a fabulous laugh. But when she spoke, she meant business.’ 2

The Clemengers’ art collection started modestly, with an eight by six-inch Ray Crooke painting that was bought from gallerist Barry Stern for £25. This was followed by a group of small paintings by Thomas Gleghorn; a Lawrence Daws for $5; a Fred Williams work on paper, bought from Rudy Komon Gallery for $190, and then a small John Olsen purchased when Peter had ‘had about three sherries… and was feeling fairly relaxed’. Driven by personal response rather than by fashion or art world ‘favourites’, the couple lived with their growing collection and rarely sold works: ‘We’ve not had a plan’, admits Peter, ‘we are just happy with what we’ve got’. 3 Their first significant acquisition was an Arthur Boyd ‘Wimmera’ painting from Melbourne’s Australian Galleries, which was $1,600 – quite a jump from the price of earlier purchases, and quite a stretch for the young couple at the time. As this sale attests, several important works followed including Brett Whiteley’s magnificent Bathurst landscape, The Wren , 1978, executed at the height of his fame; John Brack’s enigmatic still life, No More , 1986, and the joyful The Splash , 1955 from John Perceval’s iconic Williamstown series.

5

A major donation by the Clemengers to the NGV in 1991 was the impetus for the establishment of what was to become known as the Clemenger Contemporary Art Prize, a series of six triennial exhibitions (running from 1993 to 2009) which celebrated the contribution of Indigenous and non-Indigenous mid-career and senior contemporary Australian artists. Having had the pleasure of working on two iterations of this Prize in 2006 and 2009 as Curator of Contemporary Art, I came to understand and appreciate the Clemengers’ deep commitment to Australian art and artists, their generosity of spirit, and their extensive knowledge. This unique and important series was a collaboration between the Gallery’s curators and Joan and Peter, with the development of each exhibition unfolding over several years. Peter’s keen eye was largely tuned to management of the budget and to the exhibition collateral, signage, and promotion; with Joan acting, in each iteration, as one of Prize’s three judges.

It did not stop there. In 1999, Joan made a commitment to build upon the important legacy of the Gallery’s G H Michell (1976 –1987) and Margaret Stewart Endowments (1987 – 1997), which supported the acquisition of emerging Australian artists working in all media. Thus, the Joan Clemenger Endowment was born. Over the course of the Endowment’s four-year term, Joan was closely involved in the acquisition process, visiting galleries with the curators, and attending Acquisitions Meetings. The price for works was capped at $5,000 to ensure that the fund was truly benefiting artists at the beginning of their professional careers, and to enable the purchase of a greater number of works. It is telling that many of the artists whose work was acquired through this fund – including David Rosetzky, Ricky Swallow and Louise Weaver, to name but a few, are now some of our most celebrated contemporary artists.

Given the benefits they derived from travel, and from seeing the world’s best museums, Joan and Peter also established the Clemenger Travel Grant – an application-based program that

enabled the professional development of the Gallery’s curators, conservators, and other professional staff. I was fortunate to be a recipient of this grant and can vouch for the life- and careerboosting benefits of the five-week trip I was able to undertake, visiting museums and colleagues across the UK and North America. The grant has now been running for close to 20 years.

After the end of the Clemenger Contemporary Art Award, Joan and Peter’s support of acquisitions at the NGV broadened to include international contemporary art, but equally, they have also been quietly involved in the purchase of works across other collecting areas for decades. After Joan’s death in early 2022, Peter has continued the couple’s commitment to the NGV, ensuring that Joan’s legacy as a benefactor, art lover, and friend to artists continues through his involvement.

Yet the Clemengers’ benefaction is by no means exclusive, and alongside their incredible support of the NGV they fostered long

6

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

a patron of the Melbourne International Arts Festival, the pair are Lifetime Patrons of the Melbourne Theatre Company, and through the Joan and Peter Clemenger Trust (established in 2001) they support the Australian Ballet to bring international artists and companies to Australia to tour. Searching for a major tourism and reinvigoration project for Melbourne in the early 1990s, Peter established (and funded) the Melbourne Food and Wine Festival and ran the organisation for nine years. It has since become one of the world’s top food and wine events and celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. Joan was a Fellow of Heide Museum of Modern Art and was central to the fundraising efforts that enabled the Museum to develop the 2012 exhibition Louise Bourgeois: Late Works and was also a supporter of a host of organisations ranging from Orchestra Victoria to Big Brother Big Sister and Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria. The Clemenger Trust has also funded medical research through its support of, amongst other organisations, the Mental Health Research Institute of Victoria, the Centre for Eye Research Australia, the Peter McCallum Cancer Foundation and the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, and has helped address the needs of vulnerable children, young people and families through its substantial support of Anglicare. 4

In 2015 Joan and Peter Clemenger scored a rare ‘double’ in the Australia Day Honours, each becoming Officers of the Order (AO) for their support of the visual and performing arts and for their philanthropic work. Peter’s response to this very public recognition was characteristically low-key: ‘I got a letter telling me about the award and thought that’s nice…Then I opened another letter and found Joan had the same. That was wonderful.’ 5

The author is grateful to Veronica Angelatos for the notes she took during her interview with Peter Clemenger at his Melbourne home on 26 May 2022, which have informed this piece.

1. Joseph Brown (1918 – 2009) opened Joseph Brown Gallery at 5 Collins Street, close to Athol Shmith’s studio, in 1967. Max Hutchinson (1925 – 1999) was the founding director of Gallery A; Georges Mora (1913 – 1992) was the director of Tolarno Galleries; Anne Purves was the director, with husband Tam, of Australian Galleries, and Sweeney Reed (1945 – 1979) was the Director of Strines Gallery, and later, Sweeney Reed Gallery.

2. Smith J., speech notes for Joan Clemenger AO, Memorial Service, 5 April 2022. Jason Smith, also a Curator of Contemporary Art at the NGV from 1997 to 2007, worked on the 1999, 2003 and 2006 iterations of the Clemenger Contemporary Art Award.

3. Childs, K., ‘Portrait of a Patron’, Flight Deck May 1993, p. 21 in ‘EXHIBITION: JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER TRIENNIAL EXHIBITION OF CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIAN ART 1996 PART 1: APR 1993 – DEC 1994’, NGV RMU File G1111, accessed 29 June 2022

4. ‘Advertising Legend Peter Clemenger and Wife Joan Both Awarded AO in Australia Day Honours’, 26 January 2015, https://campaignbrief.com/ad-legend-peter-clemenger-and/?utm_source=pocket_ mylist accessed 23 July 2022

5. Money L., ‘Australia Day Honours: Ad Legend Clemenger and Wife Score The “Double”’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 January 2015, https://www.smh.com.au/national/australia-day-honours-adlegend-clemenger-and-wife-score-the-double-20150123-12wu6a.html , accessed 23 July 2022

KELLY GELLATLY

7

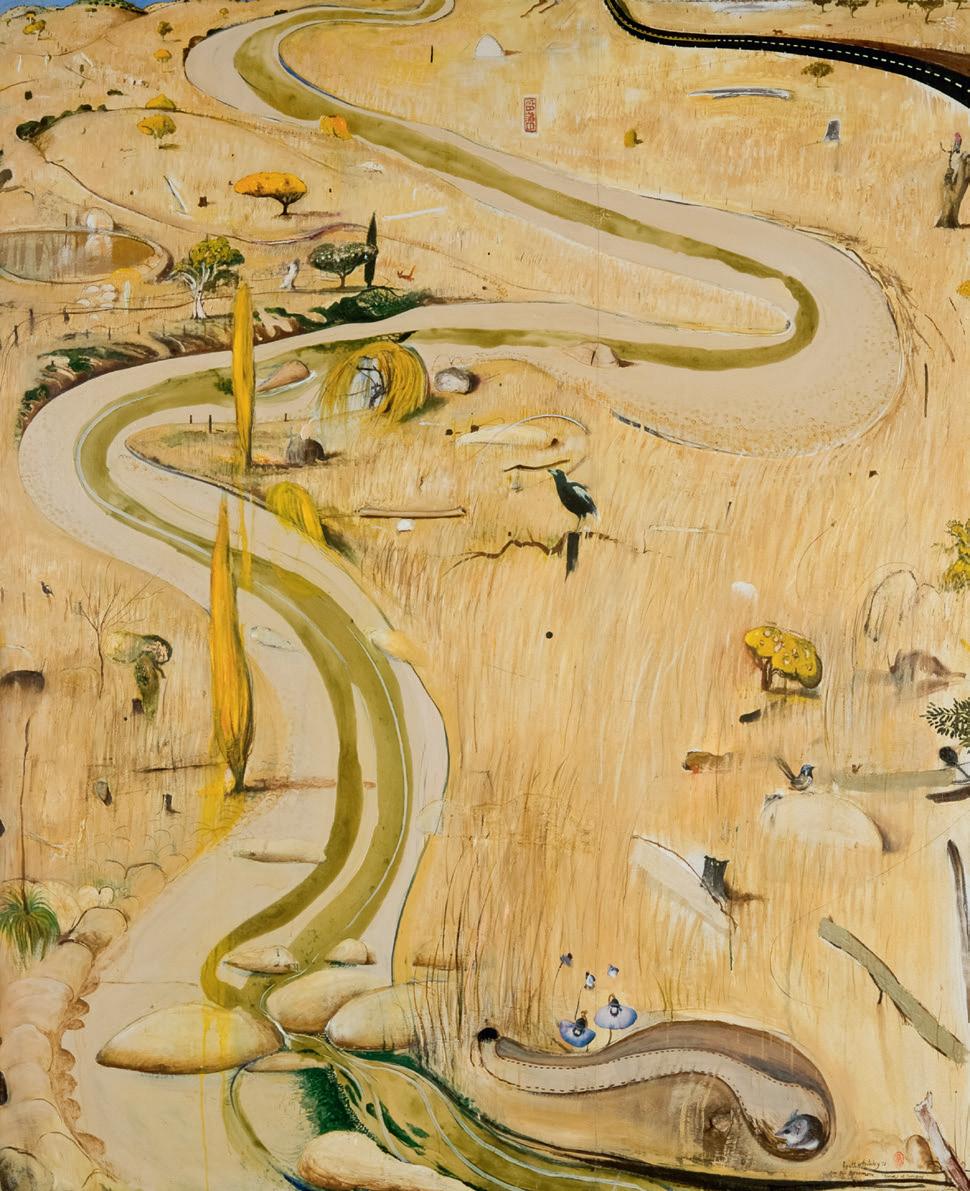

Brett Whiteley

(1939 – 1992)

The Wren , 1978 oil on canvas

168.0 x 153.0 cm

signed lower right: brett whiteley

ESTIMATE: $2,000,000 – 3,000,000

PROVENANCE

Australian Galleries, Melbourne

Joan Clemenger AO and Peter Clemenger AO, Melbourne, acquired from the above in July 1978

EXHIBITED

Brett Whiteley: paintings, drawings and three scrolls plus one bronze from 1960 Italy never before shown in Australia, Australian Galleries, Melbourne, 12 – 25 July 1978, cat. 48 (label attached verso)

LITERATURE

Makin, J., ‘Which Brett is for real?’, The Sun , Melbourne, 19 July 1978, p. 32

Sutherland, K., Brett Whiteley: Catalogue Raisonné , Schwartz Publishing, Melbourne, 2020, cat. 243.78, vol. 3, p. 556 (illus.), vol. 7, p. 457

RELATED WORK

(Blue Wren), c.1979, mixed media and collage on card, 101.5 x 76.0 cm, private collection, illus. in Sutherland, K., op. cit., cat. 176.79, vol. 3, p. 636

8

6

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

Front cover of exhibition catalogue Brett Whiteley: paintings, drawings and three scrolls plus one bronze from 1960 Italy never before shown in Australia, Australian Galleries, Melbourne, 12 – 25 July 1978

9

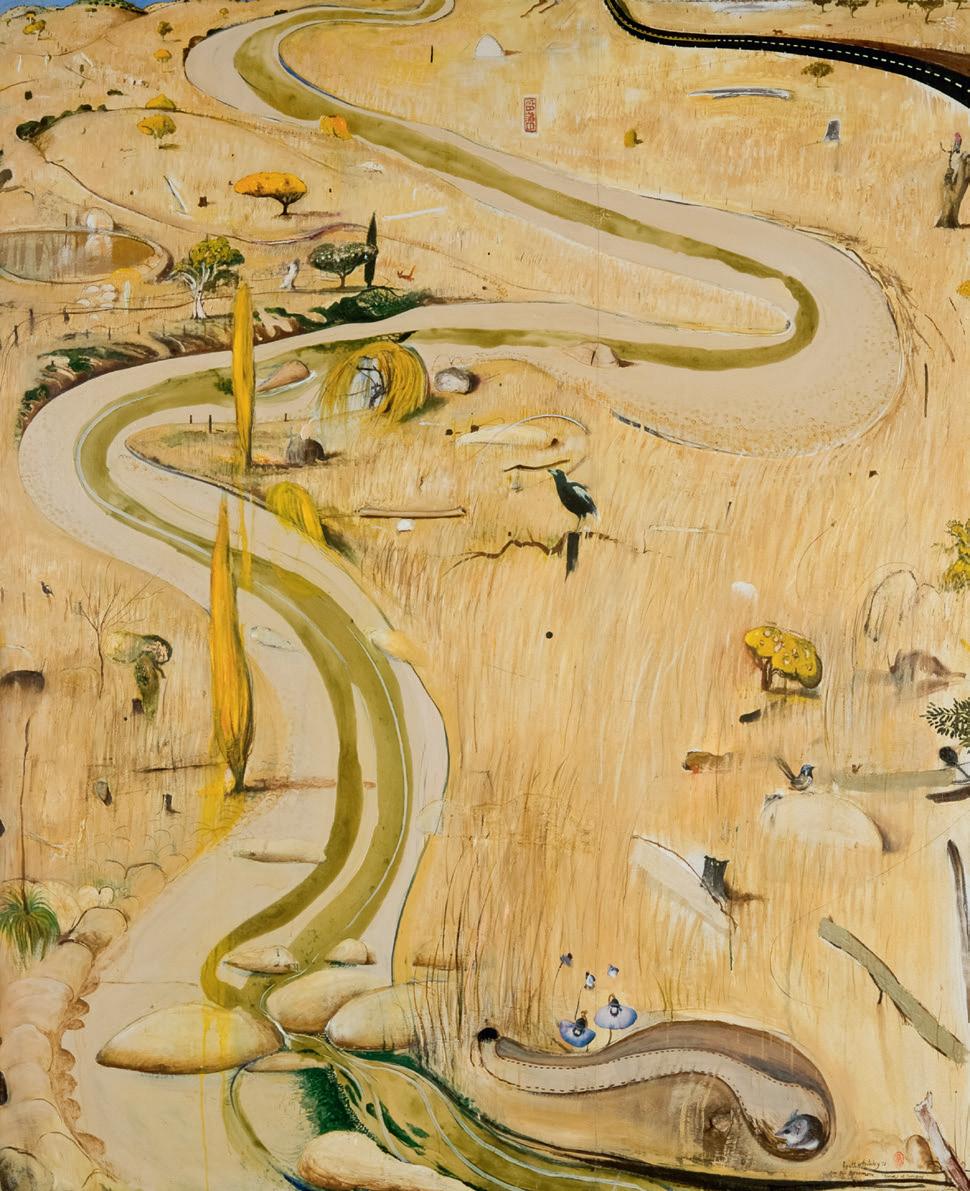

brett whiteley

‘Of all the subjects Whiteley painted in his career, landscape gave him the greatest sense of release…’ 1

After a tumultuous decade abroad, in 1969 Brett Whiteley returned to Australia and, in the tradition of many expatriate artists before him, thus embarked upon an artistic pilgrimage to rediscover his homeland. Captivated afresh by the beauty, vastness and variety of the Australian landscape, he thus explored the shifting chromatic illusions and ‘optical ecstasy’ of Sydney’s Lavender Bay in sumptuous tableaux redolent of Matisse, before subsequently revisiting the country of his boyhood in the central west of New South Wales – returning ‘to the rounded, monumental, full-breasted hills and open spaces that surround Bathurst’. 2 Today universally acclaimed among the most relaxed and quietly assured paintings of Whiteley’s career, the resultant landscapes immortalising the central west thus exuded a distinct lightness and easy spontaneity – an intimacy derived from the artist’s deep identification with this region’s geography over the span of three decades. Capturing the shimmering heat that descends on these rolling hills and gentle vales during the blaze of an Australian summer, The Wren , 1978 represents a particularly magnificent example from this celebrated period within Whiteley’s oeuvre – evoking both the detached grandeur of classical Chinese painting, and the close emotional engagement of his spiritual and artistic hero, Vincent Van Gogh. Hailing from that auspicious year when Whiteley was at the very height of his fame – his annus mirabilis of 1978 in which he became the first artist ever to win all three of the country’s most coveted art prizes (namely the Archibald Prize for Portraiture; the Wynne Prize for Landscape and Sulman Prize for Genre) – indeed the work is Whiteley at his finest, elegantly encapsulating his luminous colour, sensual line and characteristic verve all in poignant homage to the landscape where his journey as a painter first began.

In February 1948, amidst the demands of managing a business and maintaining their hectic social schedule, Clem and Beryl Whiteley made the steely decision to uproot their children – Brett, aged eight and sister, Frannie, aged ten – and pack them off to boarding schools some three hundred kilometres away from Sydney. 3 Seething with frustration at his loss of freedom and the

regimentation of boarding life at The Scots School, Bathurst, not surprisingly Whiteley felt banished, rejected and angry; as he later reflected, ‘The days were so long – it was all so stretched out. A term seemed three years. It really was a punishment and there was nothing else to do but to invent my own world – to set up a device to deal with it.’4 Notwithstanding such negatives, there were also triumphs and with hindsight, the Bathurst experience proved crucially important to Whiteley’s future development as a painter –influencing his understanding of the landscape and its seasons in a way that could not have been possible had he remained in Sydney during these formative childhood years. Notably, his teachers were perspicacious and supportive of their reluctant student’s precocious artistic talent, encouraging him to set up an easel at the back of the classroom from which he could paint the view through the window – whether it be ‘a wren that landed on a tree branch’ or ‘the hills, the sort of caressed breasts of Bathurst’. 5 Moreover, on Sundays during his final years of high school, Whiteley and his close friend, Vernon Treweeke, were granted special permission to leave the school grounds to explore and paint en plein air the surrounding Bathurst countryside – with one composition from such excursions earning Whiteley first prize in the Young Painters section of the 1956 Bathurst Show. 6 Significantly, after leaving school and while working at the Lintas advertising agency in the city, Whiteley would continue to make weekend sketching expeditions over the Blue Mountains to Bathurst, Ulladulla, Sofala and Hill End, and notably, it was a central west landscape from this time, Around Bathurst, 1959 (private collection) that won him the Italian Government Travelling Art Scholarship for 1960.7

If these seminal experiences nurtured the beginning of a profound and enduring attachment to the landscape of the New South Wales central west – a connection Whiteley described as ‘a sense of feeling close to the earth’ 8 – his response was also inevitably conditioned by a boundless admiration for that great visual rhapsodist of the region, Lloyd Rees. As famously recounted, Whiteley first made the serendipitous discovery in 1954 when, as

* * * * * * * * * *

(right page)

Brett Whiteley in his studio, 1970

photographer: Robert Walker

© Robert Walker/Copyright Agency 2024

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER 10

11

a curious, wide-eyed fifteen year old dressed in his school’s cadet uniform, he wandered into a solo exhibition of Rees’ recently painted landscapes at Macquarie Galleries in Sydney. 9 Deeply poetic in their contemplation of soft curves and arabesques all rendered with impeccable tonality, such images instinctively appealed to a young Whiteley in his ‘obsession’ with the sensuality of the landscape – with the child prodigy believing he had found in Rees a kindred artistic spirit. Indeed, Rees’ interpretations of the landscape left such an indelible impression upon his consciousness that decades later Whiteley not only dedicated an entire series to celebrating the master’s creative genius, but would write to his frail mentor to pay tribute: ‘I wanted to convey to you just how important an influence you have been on my life and on my art, how one event in 1954 had a profound effect on my understanding of what painting was and could be, and that the realisation that day has continued to influence and inspire me to this day.’ 10

Although attracted to the overtly sexual elements he perceived in Rees’ landscape, Whiteley nevertheless doubted that ‘old Reesey’ would have recognised such allusions in his own work.11 Years after the encounter at Macquarie Galleries, Whiteley would repeatedly visit Bathurst and Orange with fellow artist Michael Johnson, ‘hunting for Reesey’s hills’, remarking ‘Look at those rolling contours, he’s modelling the torso…’. As Johnson recalls, ‘We got so excited thinking of the landscape as a female figure, but we’d never say any of this to

Lloyd. Lloyd was a nineteenth-century man, settled into what he was, and we were twentieth-century kids, searching for the new.’ 12 Today one need only consider Whiteley’s early landscapes, such as The Black Sun, Bathurst, 1957 (private collection) – a portrait of melancholia prompted by his mother’s departure for an indefinite period overseas following the breakdown of her marriage to Clem – alongside Rees’ iconic south coast painting, The Road to Berry, 1947 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) to appreciate the master’s defining influence. And in turn, the debt of both artists to the surrealist landscapes of British abstractionist Graham Sutherland – in particular, his Welsh Mountains 1937, one of the few international modern paintings hanging in the Art Gallery of New South Wales at the time.13 Beyond the sensual abstracted forms of his soulful landscapes moreover, Whiteley also absorbed Rees’ predilection for intentionally leaving visible pentimenti or traces of the artwork’s evolution within the finished composition – a dynamic painterly technique that would become a hallmark of the younger artist’s oeuvre. As Whiteley recalled of his landscapes at the Macquarie Galleries’ exhibition, ‘…they contained naturalism but also seemed very invented, and the adventure of them was that they showed the decisions and revisions that had been made while they had been painted. I had never seen anything like that before… it set me on a path of discovery that I am still on today – namely that change of pace in a painting is where the poetry begins.’ 14

12

* * * * * * * * * *

Brett Whiteley Around Bathurst , 1959

oil and sand on composition board, 122.3 x 143.0 cm Private collection

© Wendy Whiteley / Copyright Agency 2024

Lloyd Rees

On the Road to Berry, 1947

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

oil on canvas on paperboard, 34.6 x 42.2 cm Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney © A&J Rees / Copyright Agency 2024

Still reeling from his experience of living the turbulent, not-quite ‘Ameri can dream’, it is of little surprise that Whiteley should seek out the landscape of the central west for solace and inspiration upon his return to his homeland. As Barry Pearce, emeritus curator at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, has noted: ‘…if in many of his other themes Whiteley confronted the difficult questions of his psyche, landscape provided a means of escape, an unencumbered absorption into a painless, floating world.’ 15 Oscillating between periods of extreme dependence on narcotics and restorative sojourns in the countryside (where the Whiteleys would invariably stay at the home of influential radio host, John Laws, in Oberon, or Michael Hobbs in Carcoar), thus the years that ensued witnessed the production of some of the most beautiful, highly acclaimed landscapes of Whiteley’s career – aptly earning him the epithet of ‘chronologist of the golden paddocks, sensual hills and willow-strewn rivers of the central west.’ 16 Culminating most famously in his highly successful solo show, ‘Rivers’, held at Robin Gibson Gallery, Sydney in March 1977, as well as the two Wynne-Prize winning paintings – River at Marulan (…Reading Einstein’s Geography), 1976 (private collection) and Summer at Carcoar, 1977 (Newcastle Art Gallery) – such large-scale landscapes poetically captured the region in its myriad moods and seasons, featuring birds, rivers, trees, rocks, skidding insects and shy mammals (both painted and assemblage), all brought together with elegia c majesty.

Monumental in scale and conception, The Wren exemplifies brilliantly this genre – complementing the dominant vertical perspective of the gliding river that ascends the picture plane with an acute attention to detail to exquisitely depict the tough beauty of a droughtravaged landscape in mid-summer. Indeed, as Jeffrey Makin, art critic for the Sun astutely observed upon the painting’s unveiling at Australian Galleries in 1978, ‘As a performer Whiteley knows few equals. His understanding of the mechanics of composition are [sic] often excellent as evidenced in ‘The Wren’. Here the relationship between flattened space and incident – ie. that bouncy blue bird – is beautifully balanced.’ 17 Recalling the legacy bequeathed by artistic predecessors Russell Dysdale and Sidney Nolan in their stark portrayal of the country’s parched interior, thus the composition similarly evokes all the colour and drama of drought – presenting a theatre of death and survival in the same reductive palette of pale desiccated yellows punctuated by cobalt blue highlights that Whiteley so favoured in masterworks such as River at Carcoar; To Yirrawalla , 1971 (Art Gallery of New South Wales); and Blue River, 1977 (private collection).

Yet, as intimated by the painting’s title, it could well be argued that Whiteley’s focus here is as much upon the motif of the little blue wren as it is the expansive landscape. Occupying a poignant place in his iconography from early in his artistic journey, birds embodied for Whiteley not only peace and tranquility – a refuge from the

13

Brett Whiteley

The Black Sun, Bathurst, 1957 oil on board, 39 x 58.5 cm

Private collection

© Wendy Whiteley / Copyright Agency 2024

Brett Whiteley

To Yirrawala, 1972 oil and mixed media on board, 185.3 x 166.3 x 6.3 cm

Private collection

© Wendy Whiteley / Copyright Agency 2024

internal demons that haunted him – but in his later work particularly, represented a yearning at once for both domestic stability and personal freedom. As Margot Hilton and Graeme Blundell elaborated, ‘Whiteley so loved birds, loved the way they hung overhead, tacking against the breeze, sliding sideways, wheeling and screeching away. He loved their freedom, the mindless glide of them. They were like a blessing on his life, an indication that the hand of God was at work…’ 18 , they were ‘the essential symbol of the song of creation’ 19 . Whether painted, drawn, collaged or stuffed and mounted, ornithological creatures populate Whiteley’s most important works – from the hummingbird and eagle appearing in his chaotic multipaneled American Dream, 1968 – 69 (Art Gallery of Western Australia) and the lyrebird, blue wren and even Donald Duck nestled within Alchemy, 1972 – 73 (Art Gallery of New South Wales), to his individual portraits dedicated to particular species – for example, Orange Fruit Dove, Fiji, 1969 (private collection, Brisbane); Pink Heron, 1969 (Art Gallery of New South Wales); Lyrebird, 1972 – 73 (private collection, Sydney); Hummingbird and Frangipani, 1986 (private collection) and even a Butcher Bird with Baudelaire’s Eyes , 1972 (private collection, Sydney). And of course, there are the whimsical avian sculptures – a Picasso-

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

© Wendy Whiteley / Copyright Agency 2024

esque owl created from a boot; pelicans fashioned from dried palm fronds; and giant egg sculptures atop Brancusian pole-plinths. Bereft of any hint of angst or menace and ‘motivated more by love than despair’ 20 , not surprisingly such bird paintings remain among Whiteley’s most universally admired achievements; in the words of Sydney poet, Robert Gray, ‘In Whiteley’s bird paintings is embodied his finest feeling; they are to me his best work. I like in the bird shapes that clarity; that classical, haptic shapeliness; that calm – those clear, perfect lines of a Chinese vase. The breasts of his birds swell with the most attractive emotion in his work. It is bold, vulnerable and tender.’ 21

Situated both thematically and chronologically between the two legendary late 1970s solo shows that explored the themes of the Bathurst landscape and birds respectively – namely his 1977 ‘Rivers’ and 1979 ‘Birds and Animals’ exhibitions, both held at Robin Gibson Gallery, Sydney – thus The Wren encapsulates Whiteley at his most lyrical, with his signature sweeping calligraphic line, dominant palette of sun-bleached yellows and luminous blues, and refreshing sense of freedom, optimism and contentment. An arcadian refuge of tranquil release and contemplation that seems almost beyond

14

Brett Whiteley

Orange Fruit Dove, Fiji, 1969 oil and mixed media on composition board, 136.5 x 122.0 cm

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

time in its stillness, indeed the masterpiece betrays an elegance and harmony unmistakably redolent of the Chinese art that Whiteley so admired, with the ‘repetition of motifs symbolising states of mind…the arabesques echoing the flightpaths of birds, which in turn mirrored the artist’s relaxed journey through his own domain.’ 22 In stark contrast to his more gruelling, visually demanding canvases of previous years, here there is no complex artifice, no anthropomorphic forms, nor flamboyant burlesques. Rather, Whiteley simply offers a romantic celebration of Nature in all her sensuality and rugged beauty, paying tribute to the landscape of his boyhood which first inspired his journey as a painter all those years ago. As the artist himself reflected upon such landscapes at the time, ‘…Sometimes I have to paint pictures that have an effortless naturalness, not artificial or synthetic, not manufactured – pictures that have no affectation through mental tricks but are graceful and according to nature.’ 23

1. Pearce, B., Brett Whiteley: Art and Life Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1995, p. 196

2. McGrath, S., Brett Whiteley Bay Books, Victoria, 1979, p. 206

3. Sutherland, K., Brett Whiteley: A Sensual Line, 1957 – 67 Macmillan, Sydney, 2010, p. 15

4. Brett Whiteley, cited in McGrath, op. cit., p. 18

5. Brett Whiteley in Interview with Phillip Adams radio 2UE, Sydney, September 1986

Brett Whiteley

Summer at Carcoar, 1977 oil and mixed media on pineboard, 244.0 x 198.7 cm

Newcastle Art Gallery, New South Wales

© Wendy Whiteley / Copyright Agency 2024

6. Sutherland, op. cit.

7. In November 1959, Whiteley was awarded Italian Government Travelling Art Scholarship for 1960, judged by Sir Russell Drysdale at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Whiteley submitted four entries: Sofala Dixon Street July c.1959; and Around Bathurst, 1959 the painting that won him the scholarship.

8. Brett Whiteley, cited in McGrath, op. cit., p. 18

9. Lloyd Rees: 22 European Paintings, 17 March 1954, Macquarie Galleries, Sydney.

10. Brett Whiteley, cited in Klepac, L., Lloyd Rees – Brett Whiteley: On the Road to Berry, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 1993, p. 7

11. According to Wendy, Rees was reportedly astounded when Whiteley pointed out to him the overt sexual elements that he had found in his paintings: see Hawley, J., ‘Whiteley and Rees: An Inspiring Friendship’, Sydney Morning Herald Sydney, 8 July 1992, pp. 13 – 17, cited in Sutherland, op. cit., p. 19

12. Michael Johnson, cited in Hawley, ibid., p. 17

13. Graham Sutherland, Welsh Mountains,1937, oil on canvas, 56.0 x 91.0 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales. For discussion of the influence of this work upon both artists, see Pearce, op. cit., p. 18 and Sutherland, op. cit., p. 19

14. Brett Whiteley, cited in Klepac, op. cit.

15. Pearce, op. cit.

16. Hopkirk, F., Brett Whiteley 1958 – 1989: The Central West Orange Regional Gallery, Orange, 1990

17. Makin, J., ‘Which Brett is for real?’, The Sun Melbourne, 19 July 1978, p. 32

18. Hilton, M and Blundell, G., Whiteley: An Unauthorised Life Macmillan, Sydney, 1996, p. 215

19. Pearce, B., Australian Artists, Australian Birds, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1989, p. 144

20. McCulloch, A., ‘A Letter from Australia’, Art International October 1970, pp. 69 – 70

21. Gray, R., ‘A Few Takes on Whiteley’, Art and Australia vol. 24, no. 2, Summer 1986, p. 222

22. Pearce, B., Brett Whiteley: 9 Shades of Whiteley (Education Kit) Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2007, p. 25

23. Brett Whiteley cited in McGrath, op. cit., p. 216

VERONICA ANGELATOS

15

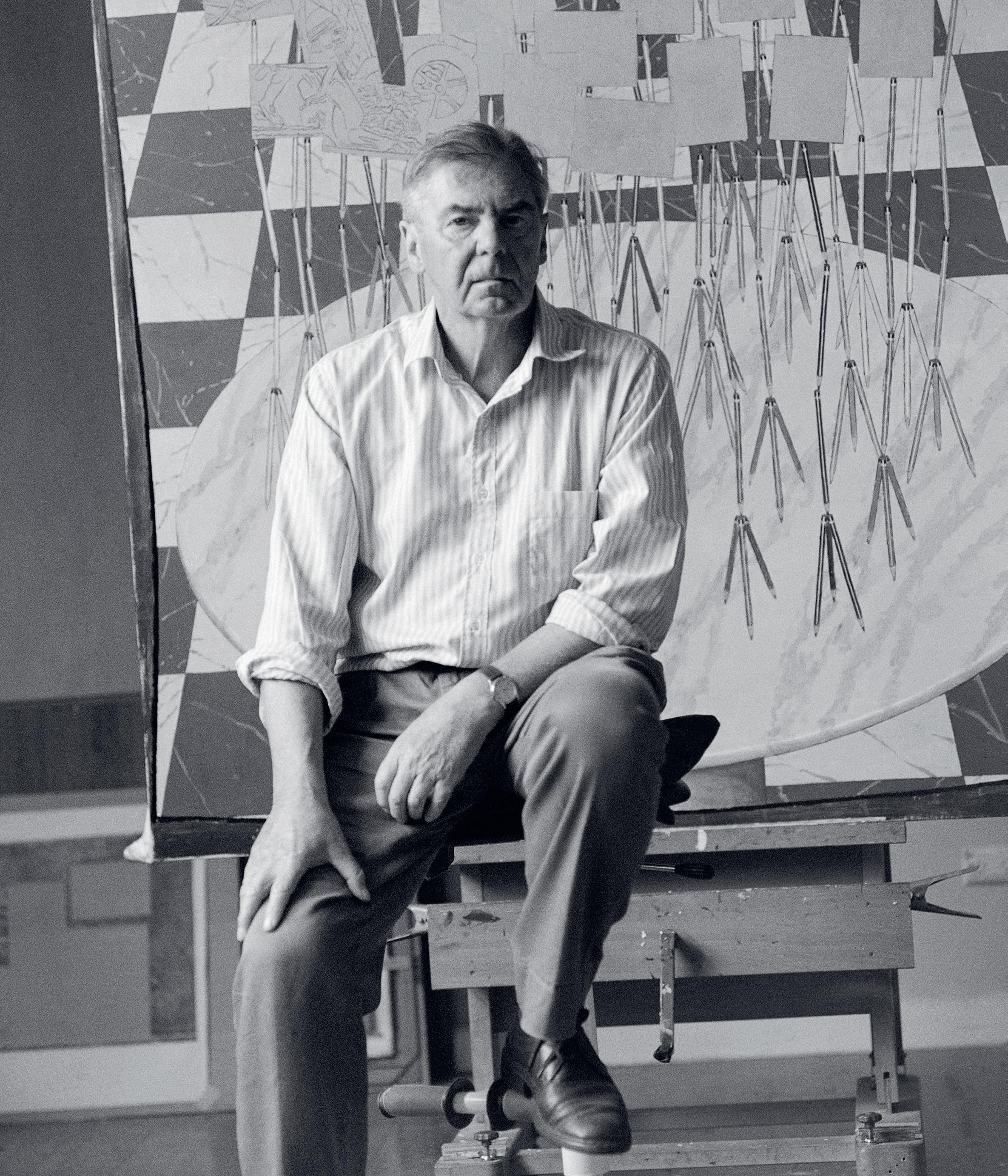

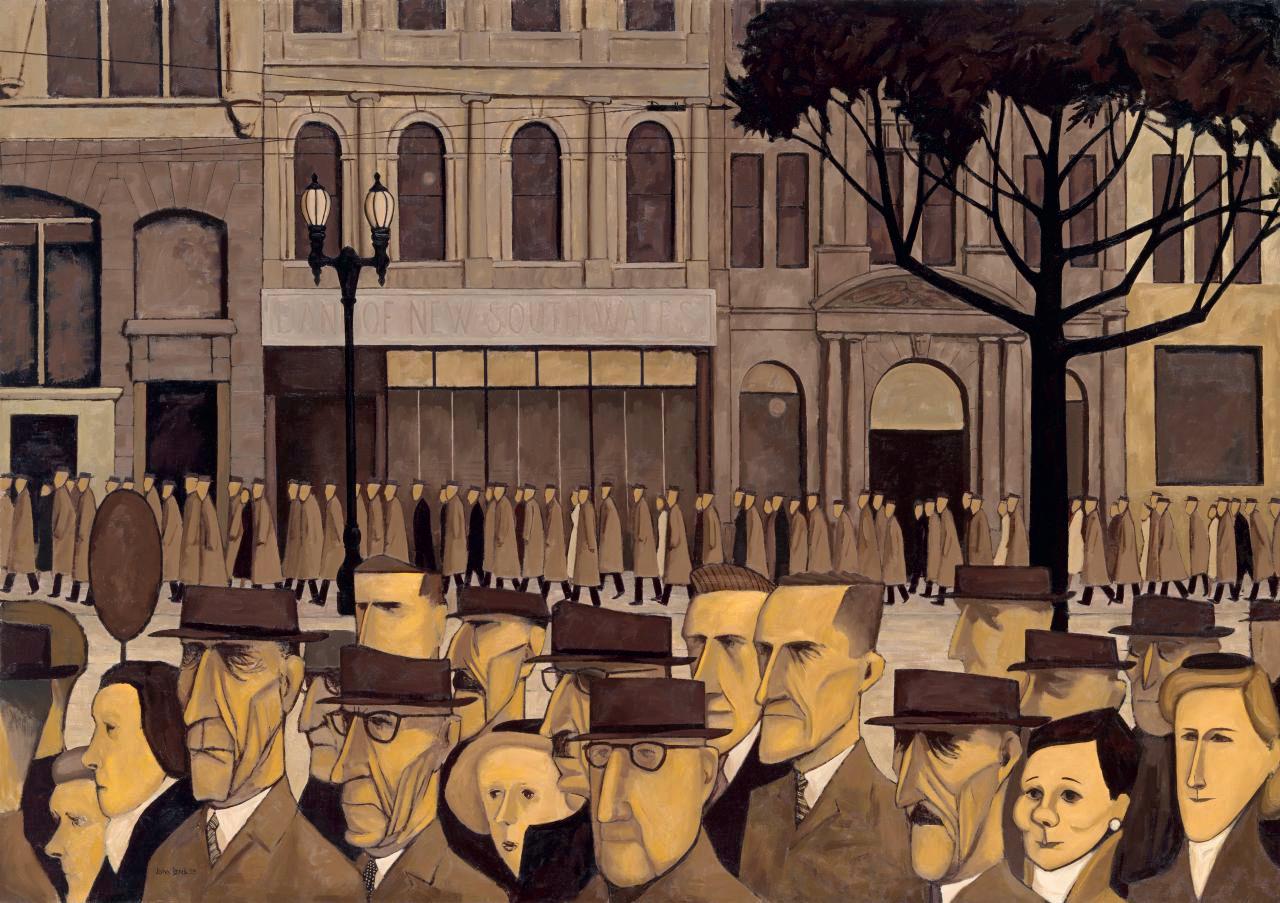

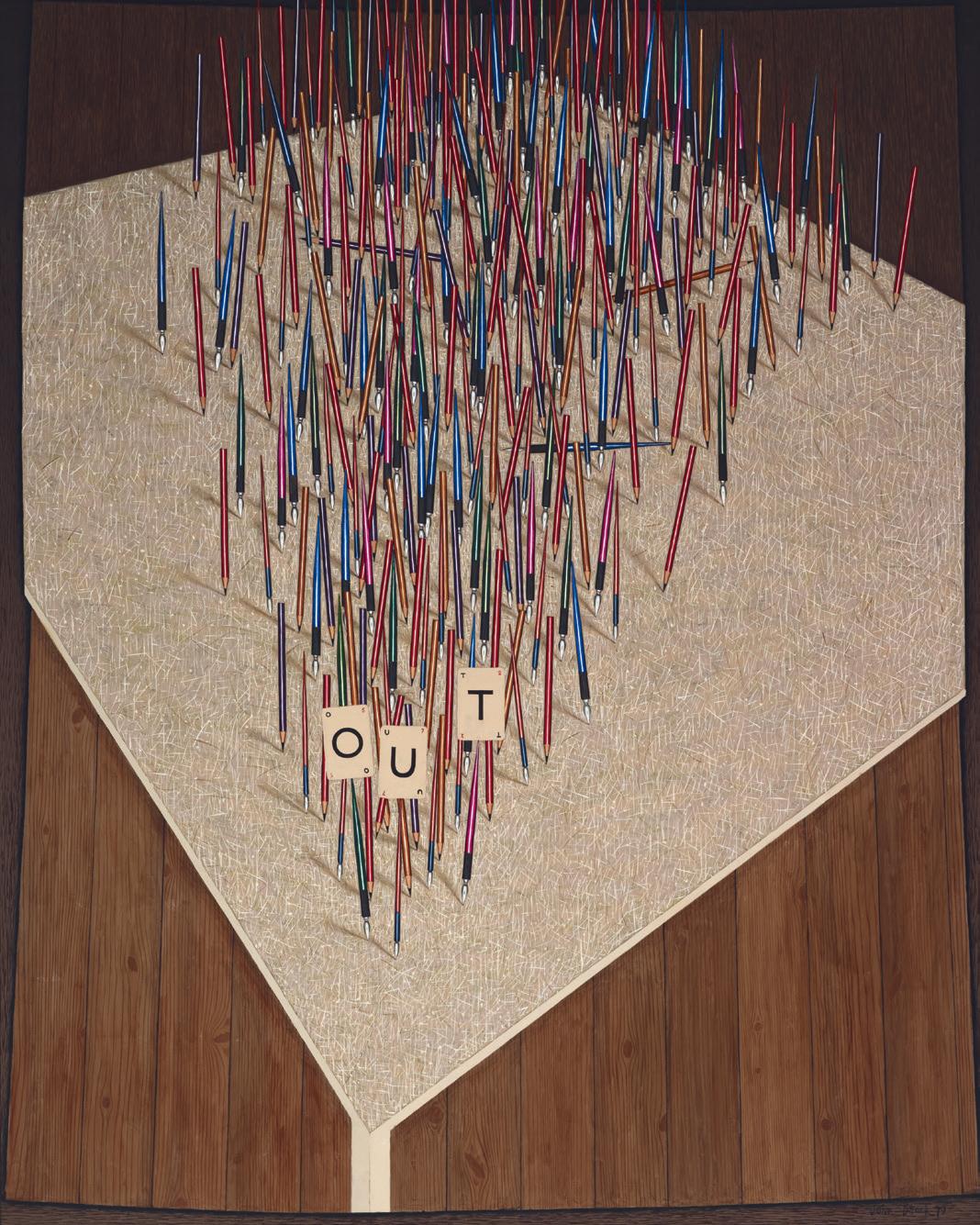

John Brack

(1920 – 1999)

No More , 1984

oil on canvas

137.0 x 137.0 cm

signed and dated lower right: John Brack 1984

ESTIMATE: $800,000 – 1,000,000 7

PROVENANCE

Rex Irwin Art Dealer, Sydney (label attached verso)

Joan Clemenger AO and Peter Clemenger AO, Melbourne, acquired from the above in December 1996

EXHIBITED

John Brack, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, 21 September – 12 October 1985, cat. 6

John Brack Paintings and Drawings, DC–Art, Sydney, 19 September – 15 October 1988

John Brack Recent Paintings and Drawings , Rex Irwin Art Dealer, Sydney, 13 April – 1 May 1993

LITERATURE

Grishin, S., The Art of John Brack , Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1990, vol. 1, pl. 53, pp. 164, 166 (illus.), vol. 2, cat. o282, p. 37

RELATED WORK

No More, 1984, watercolour, pen and ink, 68.0 x 68.0 cm, private collection, illus. in Grishin, S., The Art of John Brack , Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1990, vol. 2, cat. p289, p. 241

16

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

17

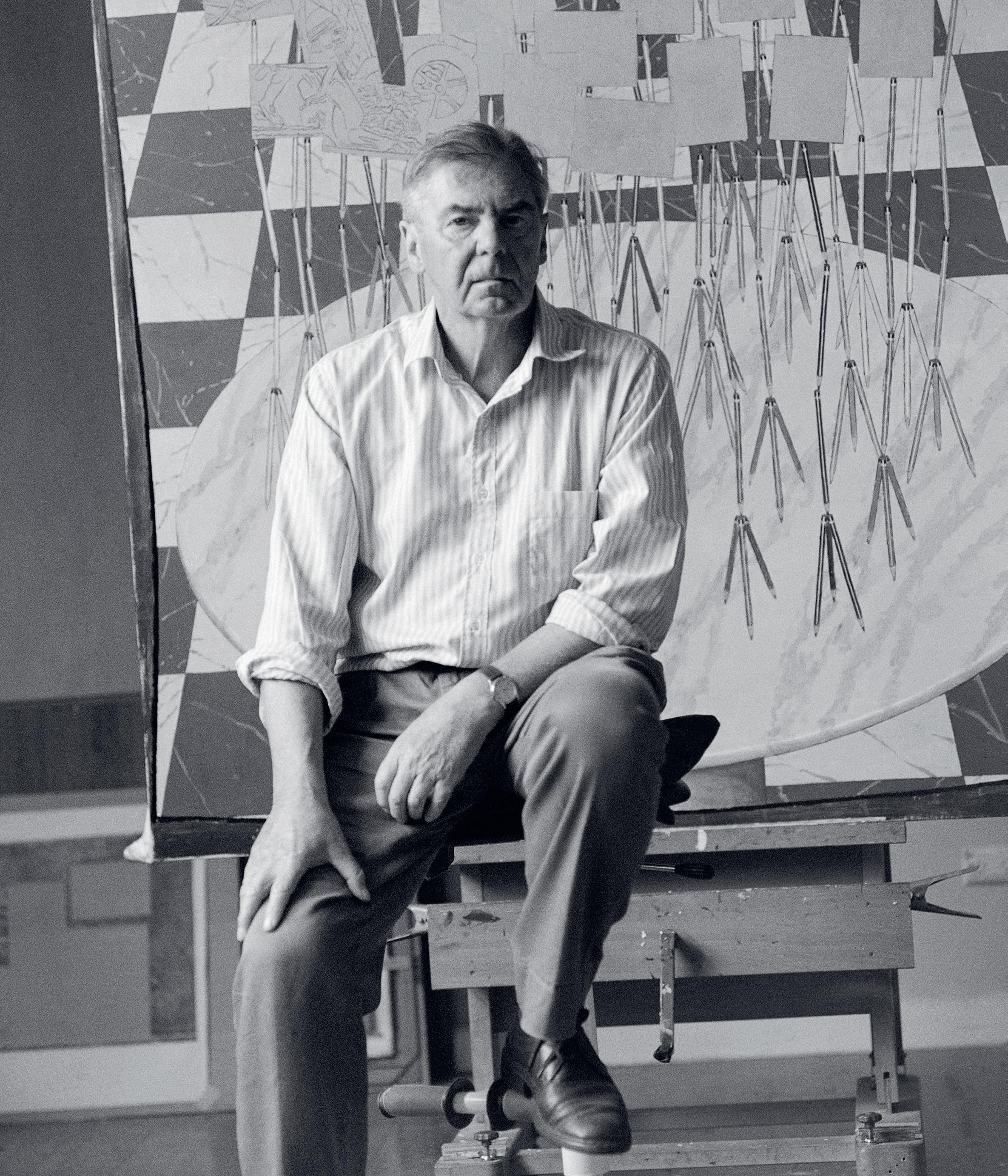

john brack

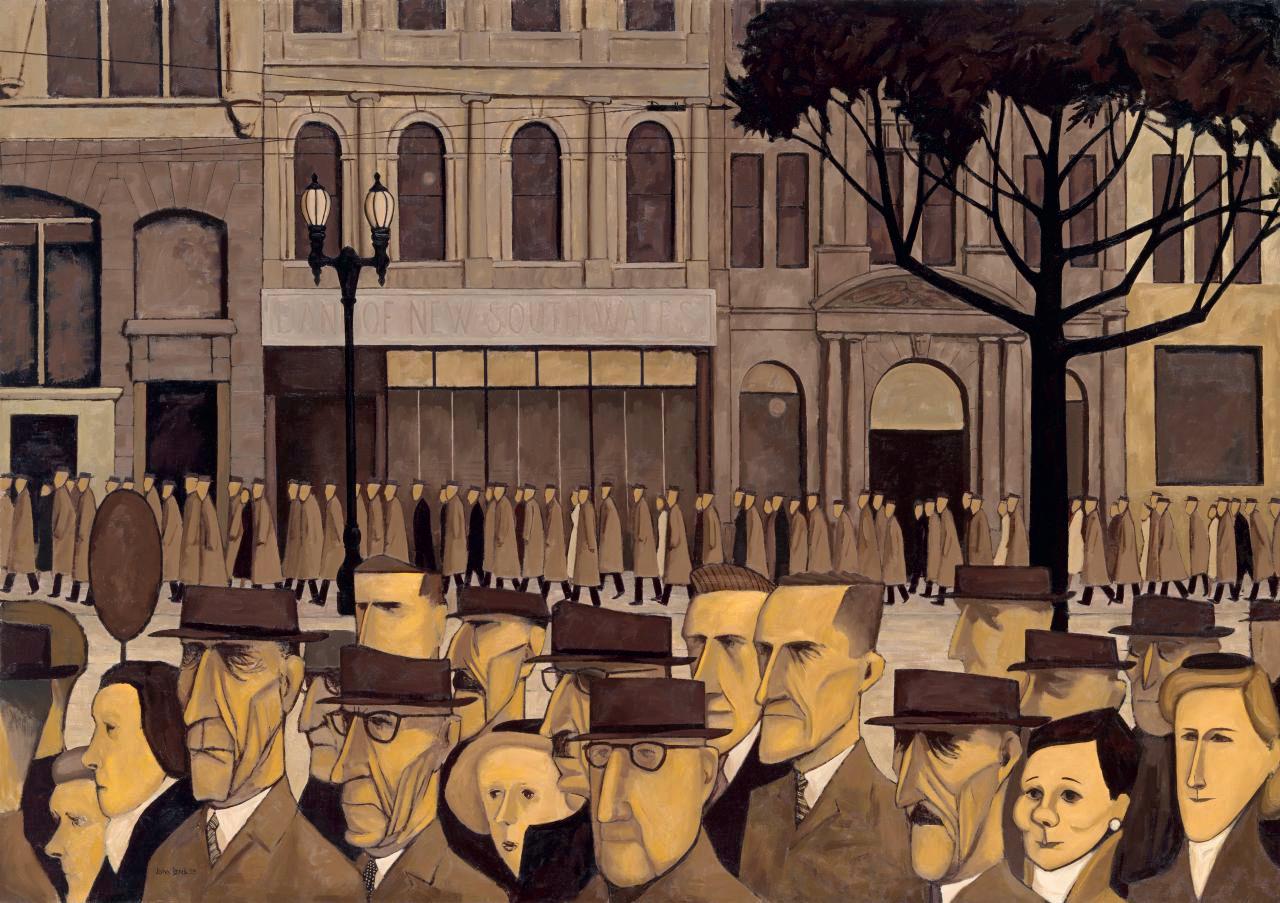

John Brack’s motivation for painting remained consistent throughout his career. In 1956, following the National Gallery of Victoria’s purchase of Collins St, 5p.m. , 1955, he wrote to Eric Westbrook, the gallery’s director, explaining, ‘One either has a subject, or one has not… If I choose to paint the life I see around me, it is because I find people more interesting than things.’ 1 Brack satisfied this intense interest in people by finding subject matter in his immediate surroundings, the suburbs and the city of Melbourne, and now iconic paintings such as The New House , 1953 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) and The Bar, 1954 (National Gallery of Victoria) still stand as acute observations of modern Australian life. While the clothing, hairstyles, interiors and other accoutrements of mid-century suburban life imbue these paintings with a strong sense of nostalgia, it is what they reveal about human behaviour and its inevitable predictability, irrespective of the era, that is most compelling. It is this element which also provides the thematic link between Brack’s most well-known works and his later paintings.

During his tenure as head of the Melbourne National Gallery School between 1962 – 68, Brack maintained a studio in a small room behind his office, however the demands of his job and the seriousness with which he approached it left little time for making art. While no commercial exhibitions took place during these years, the positive regard in which his art was held was reflected in his inclusion in several important international exhibitions and the awarding of the inaugural Gallaher Portrait Prize in 1965 for his painting of Harold (Hal) Hattam (private collection, Melbourne). In 1967 the exhibition John Brack, Fred Williams was mounted at Albert Hall in Canberra, displaying side-byside the art of two great friends who would eventually be counted among the most significant figures in twentieth century Australian

art. Brack resigned from the Gallery School at the end of 1968 and with the prom ise of a monthly stipend offset against annual sales from Sydney art dealer Rudy Komon, he was able to paint full-time and constructed a purpose-built studio at home. Including paintings from the ballroom dancing series, Brack’s first commercial exhibition with Komon was held in 1970. The following year he was awarded the Travelodge Art Prize and a monograph by Ronald Millar was published, firmly cementing his place in contem porary Australian art.

In late 1973 Brack and his wife, Helen, left Australia for the first time. With plans to travel in England and Europe for two months, he painstakingly planned their itinerary, ‘down to the specifics of street maps and detailing individual paintings that would form cultural targets .’ 2 While the experience of visiting great historical cities and seeing works of art known up until then only in reproduction left Helen buoyant, John was overwhelmed by the loss of control he felt in such unfamiliar surroundings. 3 Despite this, the trip prompted a marked shift in Brack’s art and over the next few years, the human figure disappeared from his paintings almost entirely, replaced by a range of inanimate objects including museum postcards, umbrellas, pencils, playing cards and wooden artists’ manikins. Perhaps not surprisingly, when Brack showed these new paintings publicly, his audience was confounded. The social commentary that had been such a consistent feature of his work appeared to have been discarded, along with the human figure. Sandra McGrath typified the cool response of many to this new imagery, writing in the Australian newspaper that ‘Brack’s work celebrates an intellectual rather than an emotional approach to life and art. It’s a unique vision and puts him outside the mainstream of Australian art.’4

18

(right page)

John Brack in his Surry Hills studio, 1988 photographer: Robert Walker

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

© Estate of Robert Walker

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

19

Combining this esoteric selection of objects with various domestic props to construct subtle visual metaphors, Brack found another way to express his perspective on the perennial forces of human nature, in the process transforming his view from the local to the universal. 5 As Helen Brack observed, ‘What John saw in the collections of Europe gave him all the courage and consolidation and self-confidence he needed to develop the paintings of Grand Human themes that were not in his consciousness when he was young, trying to identify in the Suburbs.’ 6 The first paintings in this vein were exhibited under the broad title of the Unstill Life Series and combined finely rendered depictions of cutlery and postcards of antiquities which Brack had collected during his visits to museums overseas. Gleaming knives and forks often appear to hover in space while the postcards are precariously balanced on their edges and corners. These paintings, and almost all that followed, also incorporated a distinctive new element in which an irregular border frames the central image. In addition to disrupting the viewer’s rightangled perspective and drawing attention to the illusionistic nature of painting, this feature also pointed to the possibility of something else beyond the painted surface. ‘John wanted to somehow alter the

balance. He knew that although the human framework calls to the right-angle and the horizontal and the vertical, you can talk about other things in the margins. The margins here are very important, because they are about the dark past, other ages. He was extremely interested in how you can use structure to say what you want to say.’ 7

If the meaning behind Brack’s Unstill Life paintings remained elusive to most viewers, the works that followed, with their themes of alliance, conflict and division, should surely have made it clear. As Sasha Grishin has noted, the artist now sought ‘to express the whole complexity of social interconnections. The form needed the potential for intricacy and complexity as well as the ability to be organised with deceptive simplicity. It needed to be a thing of considerable visual beauty, yet one that could be treated in a completely impersonal way and be worked with a sense of technical detachment in order to make the picture appear silent, permanent and durable.’ 8 In the late 1970s umbrellas, walking sticks, pencils and pens became the active figures in Brack’s paintings and, just like people, they are seen forming into groups, declaring allegiances, breaking rank and marching in

20

John Brack

Collins St, 5p.m., 1955 oil on canvas, 114.8 x 162.8 cm National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

© Helen Brack

The battle , 1981-83

oil on canvas, 203.0 x 274.0 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra © Helen Brack

triumph. The Battle , 1981 – 83 (National Gallery of Australia) is the major work from this series and by far the largest painting within Brack’s oeuvre. Setting himself the challenge of painting what he regarded as an impossible picture, Brack set out to depict the immense scale and minute detail of a military battle – specifically the 1815 Battle of Waterloo, with the French forces in blue, surrounded by the English in red and the Prussians in brown. Recalling drawing-room conversations after dinners held at the home of his new wife’s parents decades before, where ‘those old gentlemen would start refighting the battles of World War I…[picking] up their knives and forks and saltcellars… to represent the lines of the troops’, Brack stated, ‘My pens and pencils are the same thing.’ 9

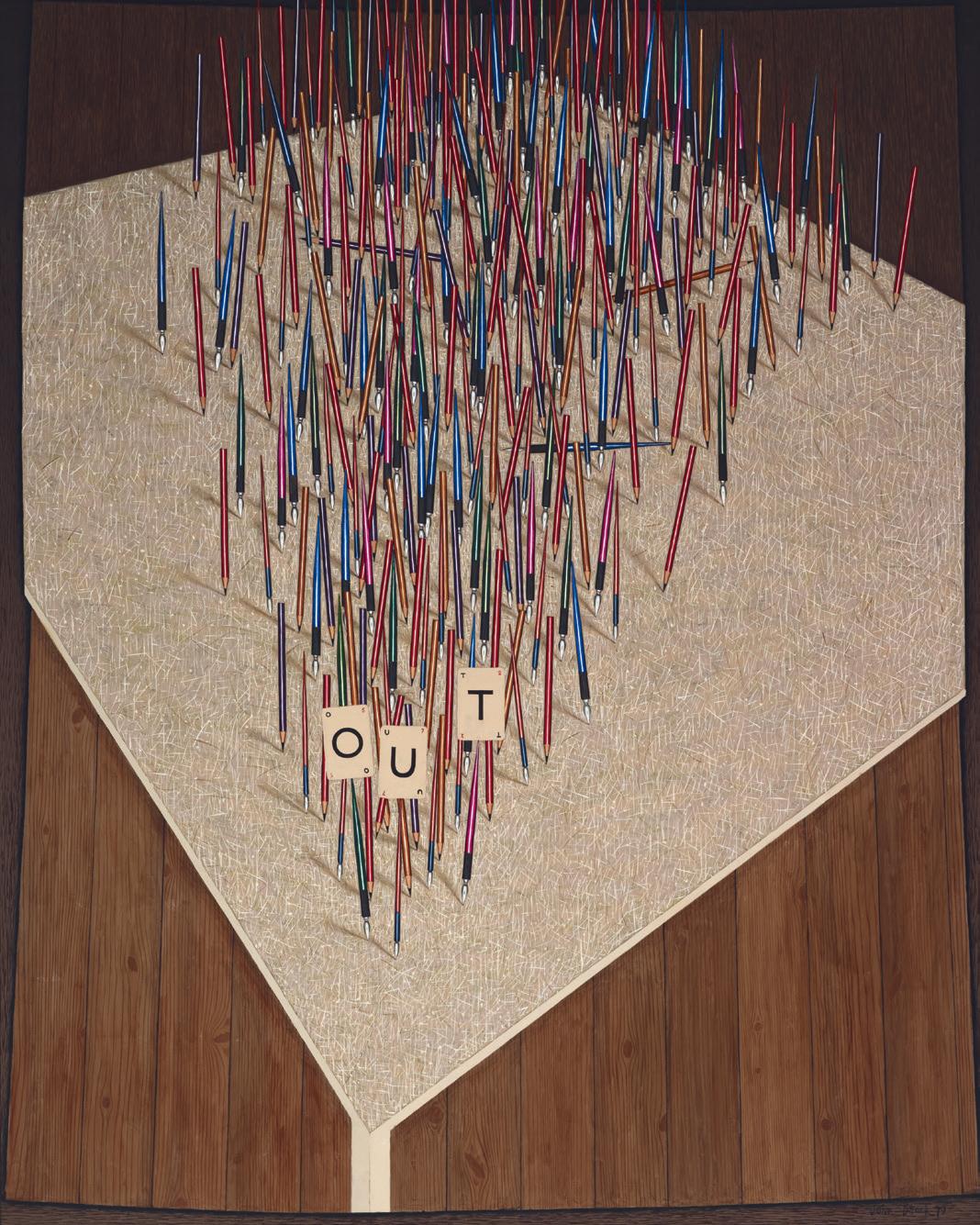

The densely massed pens and pencils of No More , 1984 appear to describe a crowd, perhaps one that is marching in protest and holding aloft a banner of playing cards which spells out the title of the painting. The message is clear – No More! – but the presence of a pair of additional cards just visible at the top edge of the painting introduces a nagging, unanswered question – No More What? We see Brack’s enjoyment of colour as the crowd of yellow, pink, lime green, blue and other brightly-hued writing implements builds. Moving in from the sides and squeezing into the centre, they are oblivious to those who have fallen, and seemingly compelled on an inexorable and inevitable path that is directed by the vertiginous tilt of the table, down to the floorboards below. The crowd builds as brightly coloured writing implements move in from the sides to join its ranks, squeezing

21

John Brack

John Brack

Out , 1979

oil on canvas, 153.0 x 122.0 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

© Helen Brack

into the centre, oblivious to those who have fallen, and seemingly compelled on an inexorable and inevitable path that is directed by the vertiginous tilt of the table, down to the floorboards below. The surface of the marble table is littered with hundreds of pencil marks, both within the confines of the marching pencils and, inexplicably, on the path in front of them, suggesting that this is not the first time such a crowd has gathered on this site. The meaning of Brack’s imagery is always enigmatic, but in the context of his exploration of human nature and the recognition that generation after generation, little changes, No More might indeed represent a personal protest against what he perceived as the inevitability of human behaviour and our inability to learn from past mistakes.

Like all of Brack’s late paintings, No More is the result of intense preparation and a meticulous technique. A series of working drawings preceded the construction of an elaborate tableaux in his studio. Using a variety of furniture props, including a marble-topped table – a familiar feature in many of the late paintings carefully selected for its distinctive veined pattern – he would build a model with fishing line and tape used to suspend actual cutlery, postcards, pencils and other items in place. From this, he would make a single, highly detailed preparatory drawing on which the painting was based. Using fine brushes and glazes to minimise the appearance of brushstrokes, Brack aimed to heighten the pictorial realism in these works and in this way, to engage viewers so that they could focus on the meaning of his imagery rather than being distracted by expressive painterly bravura.10

22

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

In the late paintings Brack’s perspective expanded beyond the local to encompass the universal. As Patrick McCaughey eloquently concluded, ‘The strategy of these paintings is clear; here the still life goes beyond the observed and the daily and passes into the life of metaphor… John Brack… transforms himself from the classicist whose forms are drawn from the experience of the world to the allegorical fabulist. The still life enables him to ruminate and reflect on ideas and arguments beyond the scope of observed appearance. Brack becomes a ‘modern history painter’, able to take on the largest speculations pictorially through the humble genre of the studio still life.' 11

John Brack

We, us, them, 1983

oil on canvas, 183.4 x 122.4 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

© Helen Brack

1. Brack to Eric Westbrook, 15 April 1956, National Gallery of Victoria Artist File

2. Gott, T., A Question of Balance: John Brack 1974 – 1994, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 2000, p. 4

3. ibid., pp.4 and 6

4. McGrath, S., ‘Brack’s unique vision’, The Australian 27 December 1975, cited in Gott, ibid., p.8

5. The exceptions to this were the nudes, a subject which Brack painted throughout his career, and occasional portraits.

6. Helen Brack, cited in Gott, op. cit., p. 18

7. ibid., p. 11

8. Grishin, S., The Art of John Brack , Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1990, p. 140

9. Brack, cited in Grishin, ibid., p. 152

10. See Grishin, op. cit., p. 132

11. McCaughey, P., ‘The Complexity of John Brack’ in Lindsay, R., John Brack , National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1987, p. 9

KIRSTY GRANT

23

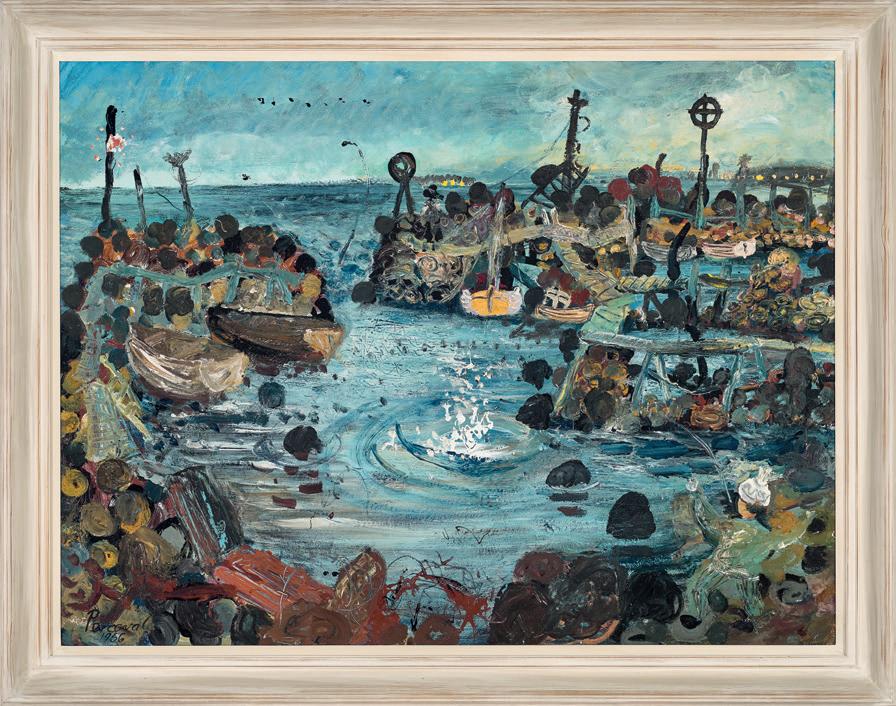

John Perceval

(1923 – 2000)

The Splash , 1956

oil and enamel on composition board

91.0 x 122.0 cm signed and dated lower left: Perceval / 1956

ESTIMATE: $400,000 – 600,000

PROVENANCE

Australian Galleries, Melbourne

Geoffrey Hillas, Melbourne, acquired from the above in 1956

Australian Galleries, Melbourne

Joan Clemenger AO and Peter Clemenger AO, Melbourne, acquired from the above in March 1975

EXHIBITED

Exhibition of Paintings by John Perceval, Australian Galleries, Melbourne, 12 – 30 November 1956, cat. 5

Commonwealth Art Today, Commonwealth Institute, London, 7 November 1962 – 13 January 1963, cat. 16

John Perceval: A Retrospective Exhibition of Paintings, Heide Park and Art Gallery, Melbourne, 10 July – 26 August 1984, cat. 47

LITERATURE

John Perceval: A Retrospective Exhibition of Paintings, Heide Park and Gallery, Melbourne, 1984, cat. 47, pp. 21 (illus.), 23

Grishin, S., ‘Perceval’s work in retrospect’, The Canberra Times, Canberra, 23 July 1984, p. 12

Allen, T., John Perceval, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1992, pp. 105, 106 (illus.), 156

Allen, T., John Perceval, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, revised edition 2015, pp. 133, 134 (illus.), 146, 171

Field, C., Australian Galleries: the Purves family business. The first four decades 1956–1999 , Australian Galleries, 2019, pp. 34, 35 (illus.)

RELATED WORKS

Gannets diving , 1956, enamel paint and gouache on composition board, 91.5 x 122.0 cm, in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, illus. in Plant, M., John Perceval, Lansdowne Press, Victoria, 1978, pl. 12, p. 41

Fisherman’s sights, Williamstown , 1956, oil on composition board, 91.5 x 121.0 cm, private collection, sold Deutscher and Hackett, 15 March 2017, Sydney, lot 6

24

8

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

25

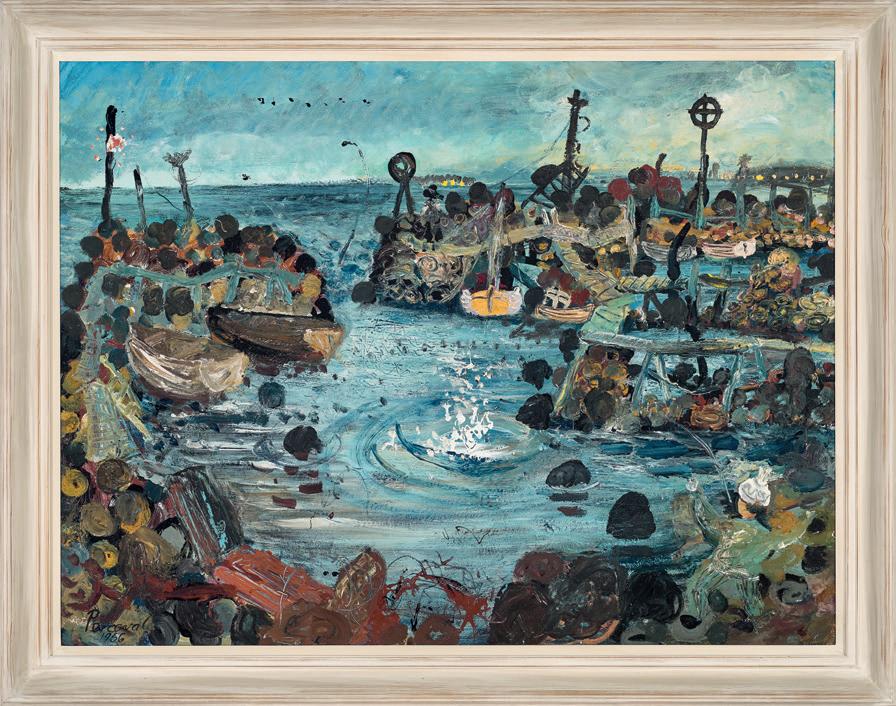

john perceval

Williamstown today is a bustling tourist town on Port Phillip Bay that proudly celebrates its maritime history. Located on the traditional lands of the Bunerong people of the Kulin nation, the area was originally called ‘koort-boork-boork’ (clump of she-oaks), a paradise for sea birds such as gannets, pelicans and black swans. In the mid1950s, however, when John Perceval first visited, Williamstown was a rundown graveyard of rusting hulks moored amidst the formerly bustling docks, but the artist, in a rapturous mood, described the experience as akin ‘to discovering Venice.’ 1 Also attracting his attention was a sequence of hand-built boat shelters located at the western edge of the town, and it was here that he painted The splash, 1956, as well as two others works Gannets diving (National Gallery of Victoria), and Fisherman’s sights (Deutscher and Hackett, The Gould Collection of Important Australian Art, Sydney, 15/03/2017, lot 6). Now known as ‘the Williamstown series’, Perceval’s joyous paintings are recognised as an iconic moment in Australian art.

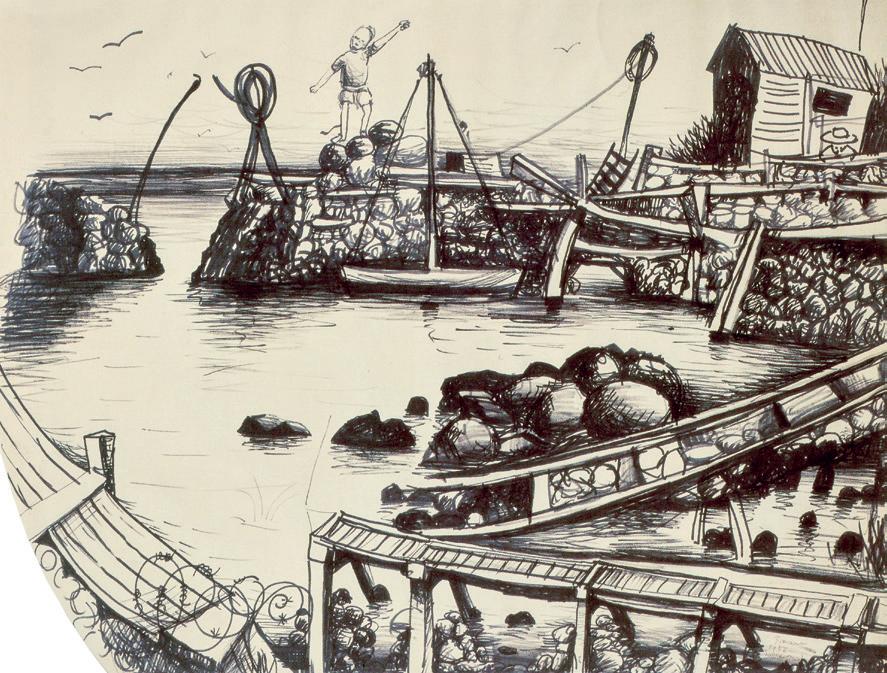

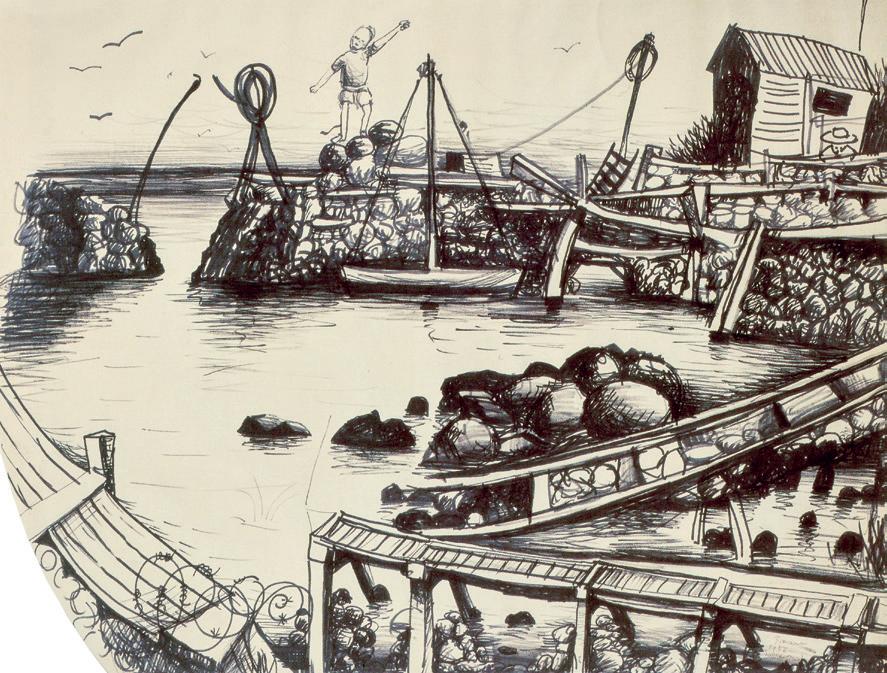

Although the artists Frederick McCubbin and Walter Withers had both painted the docks here in the early part of the twentieth century, few others had found the town worthy of consideration. Having recently bought his first car, an orange Volkswagen beetle, Perceval began exploring the outer regions of Melbourne. In 1956, with Charles Blackman as his passenger, he journeyed across the Yarra River and onwards down to Williamstown. Their mutual excitement was

captured perfectly by Blackman in his drawing Portrait of Perceval at Williamstown, 1956 (formerly Dr Joseph Brown Collection), which shows his colleague waving in excitement whilst standing atop the rock walls next to the harbour opening shown in The splash. Known variously as Bayview Harbour, the Secret Harbour, and Jimmy’s Creek, the anchorage lies at the end of Bayview Street and was built in the 1920s by local fisherman from ‘a combination of rough and dressed bluestone, bricks, concrete rubble and various other combinations of building material.’ 2 A jumble of wooden walkways linked the individual shelters, and fishermen’s sights were added using old tyres painted white. Three fishing clubs also have their sheds here.

One of the reasons why Perceval’s Williamstown paintings are so celebrated is the highly individualistic approach he took in their depiction and, importantly, in their distinctive technique. In 1944, Albert Tucker introduced Max Hoerner’s influential book The Materials of the Artist and their Use in Painting (published 1921) to Perceval and his brother-in-law Arthur Boyd, and in this they found a wealth of information concerning Old Master techniques with which they began to experiment. They also began to research the artists Hoerner referred to, and Perceval was particularly drawn to the rambunctious peasant scenes of the Northern Renaissance artist, Pieter Breughel the Elder – subsequently painting his own variants set within Melbourne environs, such as Christ Dining at Young and Jackson’s ,

26

Bayview Harbour, 1950s photographer: Bob Leak

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

27

John Perceval in his studio at the Australian National University Photographer: The Canberra Times Ltd

1948 (Private collection);; and Flight into Egypt, 1947 – 48 (Art Gallery of Western Australia). The bustling immediacy of these works are direct antecedents of the Williamstown series, and such was his new mastery of mediums and pigment that the noted artist-critic James Gleeson was moved to comment later that ‘John Perceval loves paint and is lavish with it. He loves the warmth or crispness of the air and evokes its quality with the exactness of an Impressionist and the feeling of an Expressionist.’ 3

In The splash , this description is particularly evident. Due to the number of works he painted at Bayview Harbour, Perceval was no doubt drawn to the independent spirit that had resulted in the boat harbour’s construction and sought to express his empathy though a bravura technique involving a mix of ‘resinous colour over tempera with a heightening of white, allowing a calligraphic basic drawing and a rather dry scumbled top effect.’4 Perceval painted The splash from a vantage point just outside the eastern wall of the harbour, and takes obvious delight in the tangle of timber walkways and barbed wire surrounding a scatter of typical ‘couta’ boats, surmounted by the hand-made fisherman’s sights. On the horizon, the lights of Altona and Point Cook indicate that dusk has begun to fall, whilst at the lower

right, a fisherman (wearing Perceval’s signature beanie, so likely a self-portrait) spreads his arms in delight having just witnessed a gannet plunging into the depths in search of a meal. There is a likely symbolism to the ripples left by the gannet, that of the doomed mythological figure Icarus, who drowned after the wings made by his father melted when he flew too close to the sun. Arthur Boyd painted his own version of Pieter Brueghel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, c.1560, 5 and it is plausible that Perceval also had this in mind when he painted The splash

Further cementing the significance of the Williamstown paintings was the manner of their first exhibition. In June 1956, Tam and Anne Purves opened Australian Galleries in Collingwood as a professionally focussed exhibition space, sited in a former warehouse with their extant fabric pattern-making company located at the rear. After selling a couple of paintings by Perceval, the artist asked for a solo show and on visiting his home studio, the Purves encountered a multitude of paintings of Williamstown and Gaffney’s Creek, in the wilderness of Victoria’s Yarra Ranges. Perceval was insistent that they all be shown together, so the Purves made a strategic decision and reconfigured their business to solely focus on the promotion and

28

John Perceval

Fisherman’s sights, Williamstown, 1956 oil on composition board, 91.5 x 121.0 cm

Private collection

COLLECTION OF JOAN AND PETER CLEMENGER

© John de Burgh Perceval/Copyright Agency 2024

selling of contemporary Australian art – and Perceval’s exhibition became their inaugural event. Two of the paintings had already been sold prior to the opening, Tug boat in a boat , 1956 by the National Gallery of Victoria, and Early morning – back beach 1956 purchased by the renowned collector Bruce Wenzel. On his recommendation, Wenzel’s good friend, the timber importer Geoffrey Hillas, purchased The splash and remarkably this was the only painting sold during the exhibition itself. In many ways, this reflected the conservative tenor of collectors at the time but in subsequent years, understanding caught up with Perceval, and examples of the Williamstown series have now entered a number of prestigious collections with the National Gallery of Victoria adding a second work, Gannets diving , 1956 to their collection in 1957.

1. Reid, B., Of Light and Dark: the art of John Perceval, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1992, p. 26

2. ‘Jimmy’s Creek: Williamstown Back Beach recreation precinct’, Victorian Heritage Database at https://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/13689 (Accessed 11 January 2024)

3. Gleeson, J., Modern painters: 1931 – 1970 Lansdowne Press, Sydney, 1971, p. 95

4. Plant, M., John Perceval, Lansdowne Press, Melbourne, 1971, p. 26

5. See Arthur Boyd, Boat builders, Eden, 1948, in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

ANDREW GAYNOR

John Perceval

Gannets diving 1956 enamel paint and gouache on composition board, 91.5 × 122.0 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

© John de Burgh Perceval/Copyright Agency 2024

Charles Blackman

Portrait of Perceval at Williamstown, 1956 ink on paper, 93.2 x 121.0 cm

Private collection

29

© Charles Blackman/Copyright Agency 2024

specialist fine art auction house and private gallery

John Brack

No More , 1984

John Brack

No More , 1984