2023 Family Medicine Report

2023 University of Toronto Family Medicine Report

Editor

Alisa Kim

Design

Trajectory Brands Inc.

Writers

Alicia Fung, Alisa Kim and Elaine Smith

Photography

Brian Da Silva

Cover illustration

Pui Yan Fong

We wish to acknowledge this land on which the University of Toronto operates. For thousands of years it has been the traditional land of the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and the Mississaugas of the Credit. Today, this meeting place is still the home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island and we are grateful to have the opportunity to work on this land.

Contents Message from the Chair .......................................................................... 2 LEADERSHIP Critical Engagement ............................................................................. 5 RAAM Clinic Founder Bullish on Addictions Support .............................................. 8 In Support of Health System Resilience ......................................................... 12 Looking Upstream for Solutions to Health System Challenges ................................... 16 Feedback Loop ................................................................................. 20 ‘We Watch Teachers Grow’ ..................................................................... 24 COMMUNITY Speaking Their Language ...................................................................... 29 Have a Health Concern? Call Auntie. ............................................................ 32 Bringing the Winds of Change to Toronto’s Primary Care ‘Desert’. ............................... 36 Prescribing Better “Pills” to Swallow ............................................................ 38 Q&A: Dr. Melanie Henry. ........................................................................ 42 Cultivating a Culture of Curiosity and Continuous Quality Improvement. ........................ 46 RELATIONSHIPS A Little Help from my Friends ................................................................... 49 Healthy Barrie ................................................................................. 52 Finance 101 for MDs ........................................................................... 56 Office of Health System Partnerships Engages Primary Care Providers to Address the Health System’s Most Pressing Needs 60 1 2023 Family Medicine Report

Table of

2 Department of Family & Community Medicine,

Photo: Ed Rek

University of Toronto

Too often these two words conjure up visions of endless flip charts and sticky notes, long afternoons of time lost culminating in documents that quickly prove to be too general, too specific, or too unrealistic.

That’s not how I feel. To me, a good strategic plan is a clarion call: a lucid, inspiring articulation of what we stand for, and a promise about how we will spend our time, energy and resources. And in a massive department such as ours—with more than 2,000 faculty members, hundreds of learners, and countless internal and external partners—a strategic planning process is also an opportunity to build community, get to know each other better and strengthen bonds.

Our academic collaboration with Addis Ababa University, for example, is fostering the development of Ethiopia’s first emergency medicine residency program to build the nation’s capacity in this domain. The partnership, which you can read more about on page 24, is also a beautiful example of our expansive network, and the importance of considering the specific needs of a community in all we do.

The OurCare initiative, which you can read about on page 5, is engaging the Canadian public in reimagining the future of primary care in Canada—how it can be more equitable, accessible and sustainable. This feedback, wrought through connection and collaboration with everyday Canadians, forms the basis of unprecedented engagement with policymakers who are deeply interested in the public’s perception about the current state and future of primary care in Canada.

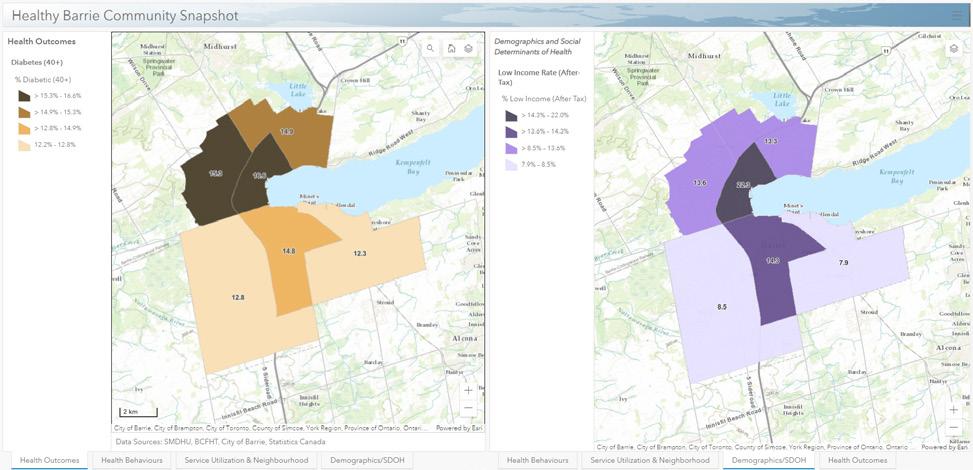

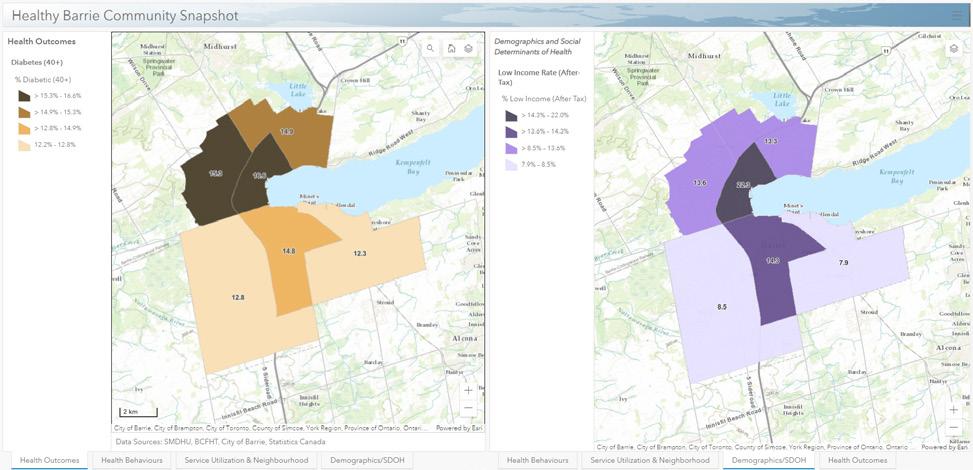

Increasingly, the work of primary care and public health are intertwined. In this report, we profile Healthy Barrie, a project that integrates public health, family medicine and municipal government action. The collaboration looks at data on various health indicators and neighbourhood characteristics to inform service policy and public health planning to drive change leading to a healthier population.

In late 2022, our Department of Family and Community Medicine concluded a community-building exercise of impressive breadth and depth, and launched a new strategic plan that I hope fulfills that dual function of community-builder and clarion call.

The three pillars of our plan—Community, Leadership and Relationships—are at the heart of everything we do in academic family medicine. The stories in this report are organized around these pillars, and of course they easily cut across themes. Each uses data from various sources to tell a story, and also engages with the narrative of our discipline, globally and locally.

The stories on these pages are just some examples (of many!) of the incredible work done across our department every day. Each story has a face—people whose work speaks of their incredible skills and commitment, as well as the people we serve. Each also uses data to propel us towards our vision: Outstanding primary care for all, powered by world-leading research, education, and innovation. In that sense, the work is just like family medicine itself: grounded in evidence and propelled by stories.

I am inspired by the depth and breadth of the work of our community for the good of our patients, our faculty and learners, and the health care system writ large—locally, nationally and globally.

Enjoy!

Dr. Danielle Martin Professor and Chair Department of Family and Community Medicine University of Toronto

3 2023 Family Medicine Report

There are lots of reasons to dislike, or distrust, “strategic planning.”

LEADER SHIP

4 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

CRITICAL ENGAGEMENT

By Alisa Kim

OurCare Initiative Brings the Public’s Voice to the Dialogue on the Future of Primary Care in Canada.

The second phase of OurCare engages the public and patients through provincial reference panels. In Ontario, more than 1,200 people volunteered to participate; 35 people representing the demographics of Ontario were selected. In February 2023, the Ontario panel met in Toronto to learn about primary care and put forward recommendations for a better system.

LEADER

Photo credit: Yuri Markarov, Unity Health Toronto

5 2023 Family Medicine Report – Leadership

The issues besetting primary care in Canada are immense and predate the COVID-19 pandemic. For one, it is very difficult for people without a family doctor to find one—particularly those in rural and remote areas. The problem will only get worse as family doctors retire in the coming years with fewer medical students choosing to specialize in family medicine to take their place. As decisionmakers try to address these matters and reform primary care in Canada, a key voice is missing—that of patients and the public.

Dr. Tara Kiran, Vice-Chair of Quality and Innovation at the Department of Family and Community Medicine (DFCM), is correcting that omission. She is spearheading a bold national initiative called OurCare that engages patients and the public in reimagining the future of primary care in Canada. The goal is to enable the average person living in Canada to have a say in developing a primary care system that is more accessible, equitable and sustainable, and to bring that feedback to policy makers.

As a scientist and family physician, Dr. Kiran understands the imperative need for users of the primary care system to be part of any reforms. “Primary care is in crisis right now. Far too many people don’t have a family doctor; those who do can’t get seen in a timely way. There have been lots of changes in primary care and the health care system including the introduction of virtual care and increased footprint of corporations. All of these things together make it the right time to have dialogue around what the system of the future should look like,” she says.

The first phase of OurCare launched in September 2022 with a national online survey that asked about people’s experiences with primary care and what they valued most in primary care. More than 9,000 people completed the survey which, among other things, inquired about whether people had a primary care provider, if they had used a walk-in clinic in the past year, how they access their medical information, and the importance of having a primary care provider or team. Results of the survey are posted online, where anyone can interact with the data and see how different groups responded to the questions.

Dr. Tara Kiran, Vice-Chair of Quality and Innovation at DFCM and the Fidani Chair in Improvement and Innovation, is leading OurCare, a national initiative that is engaging the public on the future of primary care in Canada.

The second phase of the project engages patients and the public via reference panels. In Ontario, more than 1,200 people volunteered to participate; 36 people representing the demographics of Ontario were randomly selected. The panel met to learn about primary care and put forward recommendations for a better system. There will also be reference panels in British Columbia, Quebec, Nova Scotia and one territory.

It is a priority to discuss the future of primary care in a way that is inclusive and equitable, says Dr. Kiran, who notes the team is engaging with members of the public who may not have a regular care provider. “When we think about patient engagement, we think about people who are actually taken care of. Primary care is something that should be available for everyone so we want to have that broad conversation with members of the public whether or not they have a family doctor,” she says.

More than 6.5 MILLION adults in Canada don’t have a regular family doctor or nurse practitioner.

6 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

The third phase is a series of community round tables to hear from people who are underserved by primary care systems in Canada. The OurCare team is collaborating with local organizations to understand who it should be engaging, and to rely on the groups’ relationships and expertise to bring people together. “[The round tables] are designed to focus on equity issues and bring voice to marginalized communities and their specific needs and priorities,” says Dr. Kiran.

After each phase, the researchers will produce a report about the findings. The reports will be shared with the public and a long list of stakeholders including government and health care organizations—all of whom are deeply interested in the public’s perception about the current state and future of primary care in Canada. “I don’t think there is any government that isn’t interested in what the public has to say about what the future of primary care should be. I think often they don’t have a direct vehicle to converse with the public to understand the perspective,” says Dr. Kiran.

OurCare reflects the priorities of DFCM through its work in the Quality and Innovation program, which, in 2022, established a Family Medicine Patient Advisory Committee. The committee is comprised of 16 patient partners who receive care at one of DFCM’s clinics. Its members come from a variety of backgrounds to form a diverse and inclusive group.

When the call for patient partners was made, there was a strong response, notes Dana Arafeh, DFCM’s first Patient

and Family Engagement Specialist. “We had 150 apply for the role. From there, we selected 16. We wanted representation from all of the clinics and looked at sociodemographic information and the type of connection patients might have to a primary care clinic. There is definitely a diverse range of perspectives,” she says.

The Patient Advisory Committee, which meets bi-monthly, advises DFCM on a variety of topics related to improving the quality of care delivered in family medicine. It helps the department form questions for its patient experience survey, assists in interpreting results of the survey and gives feedback on new projects aimed at improving care. The group will also provide advice on the education of family medicine residents by helping the department communicate the role of residents to patients, and will provide input on curriculum and advice on how to give feedback to residents. “We are getting the patient perspective on what’s missing at our clinics, how can we start communicating better about what we do, what a teaching clinic looks like, and what people can expect from a resident,” says Ms. Arafeh.

Engaging patients to try and improve the health care system is critical, says Dr. Kiran. “I’ve learned over the years how important it is to hear directly from the people using the system how we should design it. Each time I’ve done it, I’ve learned a lot. The public and patients provided stakeholders with important insights we wouldn’t have gotten otherwise that helped shed light on what the priorities are and how we should move forward.”

Some Recommendations from the Ontario OurCare Priorities Panel:

• Expand team-based care to every resident

• Ensure patient access to personal health data

• Legislate and enforce interoperability data standards

• Invest a greater proportion of total health care funding in primary care

• Strengthen links between primary care practitioners and community agencies

The OurCare initiative engaged people across Canada about their care experiences and what’s important to them when it comes to primary care. Learn more at OurCare.ca.

7 2023 Family Medicine Report – Leadership

DFCM Assistant Professor Dr. Hasan Sheikh is a physician in the emergency department at University Health Network and in the Rapid Access Addiction Medicine clinic he cofounded there in 2018.

RAAM CLINIC FOUNDER BULLISH ON ADDICTIONS SUPPORT

By Elaine Smith

8 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

Dr. Sheikh, a faculty member in the University of Toronto’s Department of Family and Community Medicine (DFCM), says, “I don’t think you have to be in a formal position of authority to be a leader and empower others to make change. I try my best to be a leader, but as to whether or not I’m successful, you’d have to ask others.”

His colleagues are happy to praise his leadership abilities.

“Dr. Sheikh is a very effective leader,” says Dr. Jennifer Hulme, a physician in the emergency department at the University Health Network (UHN) and in the Rapid Access Addiction Medicine (RAAM) clinic he co-founded there in 2018. “He leads by example and is very inclusive, but he is good at making executive decisions when we need action.”

DFCM and the provincial government also recognize Dr. Sheikh’s leadership potential. The emergency and addictions physician is the most recent winner of DFCM’s Louise Nasmith Award, given annually to provide an early career faculty member with protected time to research, prepare, and disseminate a lecture or workshop on a change-relat-

ed topic. In fall 2022, he was also named the provincial clinical lead for substance use disorders at the Mental Health and Addictions Centre of Excellence at Ontario Health.

Dr. Sheikh has been involved with public health and government policy in the past. In addition to his clinical experience, while earning a master’s degree in public administration at Harvard University, he worked with the City of Calgary on creating a municipal mental health and addiction strategy, the first city in North America to do so.

“I wanted to take a person-centered view of the addictions sector in the city, and to do that I consulted with a very diverse group,” he says. “That included many members of the community: I consulted with people who were actively using substances, those in treatment programs including the injectable Opioid Agonist Treatment (iOAT) program, and those who were in abstinence-based recovery programs. I also connected with community agencies that worked with people experiencing homelessness and with people who were using substances, and even connected with law enforcement as well to hear their perspectives.”

Dr. Hasan Sheikh’s favourite definition of leadership comes from Marshall Ganz, a professor at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government who teaches community organizing: “Enabling others to achieve shared purpose in the face of uncertainty.”

9 2023 Family Medicine Report – Leadership

The Louise Nasmith Award will provide Dr. Sheikh with some protected time to do systemic work that he can bring back to DFCM.

“I’d like to develop a framework of how to reframe our most frustrating clinical experiences and redirect our attention to look at the upstream failure,” Dr. Sheikh says. “Can we create a framework to systemically figure out policy failures and where to intervene?”

“This desire is based on my clinical experiences; I want to take a step back to see how I can help others who are doing similar work. We don’t get medical school training on how to diagnose or treat policy failures, despite the fact that we are the ones who see their effects every day.”

“For example, homelessness and the lack of affordable housing is a significant challenge,” he says. “Housing first strategies have shown to improve people’s mental health and substance use. Many of my patients tell me that homelessness is a major driver of their substance use.”

One of Dr. Sheikh’s proudest achievements to date is co-founding the RAAM clinic at UHN as part of a network of such clinics across Ontario. A RAAM clinic is a low-barrier, drop-in clinic that patients can attend to get help for a substance use disorder without an appointment or formal referral. It provides time-limited substance use care that includes pharmacotherapy, brief counselling, and referrals to community services.

“META:PHI (Mentoring, Education and Clinical Tools for Addiction, Partners in Health Integration) pioneered this model and built a ton of resources and a good community of practice,” Dr. Sheikh says. “It is a complete game-changer for people. It really works for people suffering from substance use disorders. We published a study on our first six months of data and patients with alcohol use disorder that came to us from the ED did even better than those referred from primary care, even though they started with more severe illness.”

In fact, the clinic began by operating for only two half days each week and is now open five half days a week. Currently, the clinic is trying a new intervention for people with stimulant use disorder that uses the reward centre of the brain to motivate them by offering vouchers for positive steps.

“The clinic fits with a DFCM pillar that says we should integrate research into our interventions and be accountable to the people we are trying to help,” Dr. Sheikh says.

Notes his colleague Dr. Hulme, “Although RAAM is not unique, it’s unique to have emergency physicians there. Dr. Sheikh has been instrumental in changing the culture of our emergency department with continuing medical education and support to our emergency providers about which medication to start people with and how to counsel them. He’s done a lot of outreach to the family health team, because people do much better with support from their family physicians. He has also helped ensure that addiction medicine is a core rotation in a family medicine residency.”

10 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

“We don’t get medical school training on how to diagnose or treat policy failures.”

417 patient visits to the RAAM clinic at Toronto Western Hospital in the first six months of 2022.

In addition to his clinical work, Dr. Sheikh is also involved in research. He is a co-author of a study published in 2020 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal that grew out of curiosity about what happened to ED patients with repeated visits for alcohol intoxication.

“We looked a year forward from their ED visits and discovered that of those who had two visits or more in a year, one in 20 died, while among those who visited five or more times in a year, one in 10 died,” he notes. “This is comparable to the mortality after having a heart attack. We should be wrapping care around these people; but they aren’t treated with the same priority or severity as they should be.”

He is committed to helping as many people with alcohol use disorder as possible.

“We know that for some part of the emergency department population, the RAAM clinic works, but for others, it isn’t the model of care they need,” Dr. Sheikh says. “We need to determine what those supports are so we can work on the silent epidemic of alcohol-related harms. Can we move away from siloed, stigmatized care toward a more compassionate system that works with the realities people face?”

Dr. Sheikh has a long career in which to answer those questions and it’s apparent he’s off to a running start.

Opioid poisonings result in about 7 ED visits in Ontario daily and more than 13 hospitalizations per day across Canada.

1 in 3 Canadian adults meet the criteria for substance use disorder during their lifetime.

11 2023 Family Medicine Report – Leadership

Source: Wiercigroch, D et al. A rapid access to addiction medicine clinic facilitates treatment of substance use disorder and reduces substance use (2020); 15:4.

Dr. Danielle Martin, Professor and Chair of the Department of Family and Community Medicine at U of T, conceived a three-part brief for the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table on the strengths and challenges of primary care in Ontario during the pandemic. She is also a family doctor in the Women’s College Hospital Family Practice Health Centre.

12 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

IN SUPPORT OF HEALTH SYSTEM RESILIENCE DFCM RESEARCHERS HIGHLIGHT THE ROLE OF PRIMARY CARE DURING THE PANDEMIC IN ONTARIO

By Alisa Kim

A team led by researchers from the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto authored a threepart brief on the strengths and challenges of primary care in the pandemic for the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table.

13 2023 Family Medicine Report – Leadership

The reports, published on Oct. 3, 2022, detail the work of primary care providers during the first two years of the pandemic, outline issues affecting primary care in Ontario, and offer lessons learned to improve access to primary care.

“The pandemic is not over, and COVID-19 is increasingly an illness that will be managed in the community, supported by family doctors, nurse practitioners and primary care teams. The Science Table wanted to understand the evidence base around the contributions of primary care to the pandemic response so far, as well as current strengths and challenges that will affect response to future waves. At this time it is critical to understand the lessons learned from the last two and a half years ,” says Dr. Danielle Martin, Professor and Chair of the Department of Family and Community Medicine at U of T, who conceived the briefs. The core authors include experts in primary care from across Ontario with a wide variety of backgrounds, including Drs. Imaan Bayoumi, Azza Eissa, Noah Ivers, Tara Kiran, Derelie Mangin, Sarah Newbery, Andrew Pinto and Kamila Premji. The team analyzed more than 200 articles for the research and consulted experts broadly in its work.

The release of the briefs is the last official act of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. Comprised of scientific experts and health system leaders, the advisory table evaluated and reported on evidence relevant to the pandemic to guide Ontario’s response. Research shows health systems with strong primary care have better health outcomes and improved health equity at lower cost; an examination of the lessons learned about primary care in the pandemic seems a fitting capstone activity for the Science Table.

The three-part brief is an ambitious undertaking involving dozens of researchers and primary care experts from across Ontario, Canada and internationally. The briefs outline the evidence on how primary care clinicians—family doctors, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, social workers and other allied health care providers—took on new roles and worked more days to support COVID-19 care in addition to their routine clinical work, which includes preventive, chronic and acute care. Primary care clinicians in Ontario assumed new responsibilities like COVID testing, assessment and isolation; vaccine counselling and delivery; treatment prescribing and referral and post-COVID acute care. They also aided other areas of the health system like emergency departments, intensive care units and long-term care, and assisted people experiencing mental health issues as well as poverty and food insecurity.

“As misinformation rises around COVID-19, primary care clinicians are highly trusted members of their communities—they are an invaluable resource for conveying fast-changing scientific developments around prevention and treatment of COVID-19 to the public,” says Dr. Fahad Razak, scientific director of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table and an associate professor in the Department of Medicine at U of T.

Ontario faces a significant challenge in keeping up with demand for primary care, the researchers note. About 2.2 million Ontarians do not have a regular family doctor, with new immigrants and people living on low incomes least likely to have one. Moreover, 1.7 million Ontarians have a family doctor who is of retirement age. Compounding this shortage is the decline in medical school graduates choosing to specialize in family medicine. These challenges, along with inequitable access to team-based care, shape the ability of primary care to respond to future pandemic waves and support health system recovery.

Based on their findings, the researchers outlined lessons learned:

1. Care provided in formal attachment relationships and through team-based models provides superior support for COVID-19- and non-COVID-19-health issues in the community.

2. In the absence of additional resources, COVID-19 response results in tradeoffs and unmet needs in other areas.

3. Innovative models and new partnerships supported patients to get needed care, but infrastructure is needed for sustainability, spread, and scale.

4. The absence of an integrated data system compromised the pandemic response in primary care.

5. Primary care can leverage its longitudinal relationships to achieve public health aims.

Dr. Martin says the ultimate goal of the work, which received widespread local and national media coverage, is to provide evidence to help decisionmakers, including governments, professional associations, and front-line providers to improve the ongoing pandemic response. “We’re in a state where we’re facing significant health human resources shortages, inequitable access to teams and uncertainty about the future. My hope is that the crisis we’re facing will motivate all leaders in the system to look to the evidence about how we can best improve access to high-quality primary care for all Ontarians.”

14 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

Lesson 1

Care by a regular primary care provider or team provides better support for health issues in the community.

Lesson 2

In the absence of more resources, COVID-19 response results in tradeoffs and unmet needs in other areas.

Lesson 3

Innovative models and new partnerships helped patients get the care they needed, but infrastructure is required for sustainability, spread and scale.

Lesson 4

The absence of an integrated and inclusive data system compromised the pandemic response in primary care.

Lesson 5

Primary care can leverage long-term relationships to improve population health and health system sustainability.

15 2023 Family Medicine Report – Leadership

16 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

LOOKING UPSTREAM FOR SOLUTIONS TO HEALTH SYSTEM CHALLENGES

By Elaine Smith

Dr. Andrew Pinto, an Associate Professor in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto, wears many hats: family physician, public health specialist and scientist. He also holds an Applied Public Health Chair from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and is the only family physician among the seven researchers nationwide who received this honour.

17 2023 Family Medicine Report – Leadership

The award, worth $1.15 million, provides mid-career researchers with an opportunity to collaborate with policy makers to support evidence-informed decision-making that improves health and health equity. Dr. Pinto attributes the recognition to the work being done by his Upstream Lab based at MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions, St. Michael’s Hospital, one of the University of Toronto teaching hospital partners.

He created the lab in 2016 as a way to make medicine more effective by looking upstream to the social determinants of health and the interventions that could create change at an individual, organizational or policy level.

“My selection speaks to the fact that the Upstream Lab is recognized in Canada and elsewhere for showing leadership in a challenging area,” he says of the five-year Applied Public Health Chair. “I see the lab as a resource for the community to use to create change and innovative solutions. We have a social justice focus and we seek to both describe and solve problems.

“It’s something I can’t do by myself, but I have a fantastic team of 26 staff and a dozen graduate students and post-doctoral fellows. We’re also starting to be the home for other research scientists,” says Dr. Pinto.

Dr. Archna Gupta, PhD is a member of the Upstream team. The family physician is finishing her post-doctoral fellowship in the lab and will soon become one of its scientists.

“The fact that Dr. Pinto started this lab well before others recognized the problem is impressive and the dedication he puts into pushing the envelope is amazing,” Dr. Gupta says. “The growth of the lab is a testament to his leadership and his ability to get grants for projects that aren’t traditionally funded.”

With his new appointment, he hopes to establish a repository of evidence around what works in terms of upstream actions; determine what works to help health organizations look at the external factors that could be addressed to prevent various health problems; create a network of upstream clinics across Canada; and examine policy and opportunities for policy change through the Upstream Policy Observatory.

His CIHR chair and the Upstream Lab aren’t the only balls Dr. Pinto is juggling when it comes to research. In 2022, he was awarded $10 million in federal funding for CanTreatCOVID, which stands for Canadian Adaptive Platform Trial of Treatments for COVID in Community Settings. The trial is a national study of the effectiveness of current and future oral COVID-19 therapies to reduce symptoms faster and prevent long COVID. It is designed to identify useful and affordable medications so they can be made readily available in community settings.

“People needed better evidence about whether these treatments work, especially in a highly vaccinated population,” says Dr. Pinto. “They are expensive and we need to

18 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

Dr. Andrew Pinto (far left), an Associate Professor at DFCM, leads the Upstream Lab based at MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions, St. Michael’s Hospital. The lab aims to improve health through upstream social interventions. Photo: MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions.

know if it’s a good use of public money. It’s a great way to identify what works and test it in a continuous way.”

The team comprises primary care researchers and infectious disease and public health specialists. The goal is to attract 3,000 people to the study for each treatment, starting with Paxlovid and adding more therapeutics as they emerge. Participant recruitment is happening through primary care physicians, emergency rooms, pharmacies, COVID assessment centres and appeals to the public. Provincial hubs in British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Quebec, Newfoundland and Ontario will help connect patients to treatments.

The researchers hope to have feedback within six months and are looking at ways to disseminate the findings quickly, while continuing to assess other treatments. They are working in conjunction with colleagues in the United Kingdom who are doing a similar study, looking for ways to collaborate and pool their data.

“We’ll follow the patients over the course of their treatment and for six months afterward,” Dr. Pinto says. “Our main question is whether any of these treatments reduces hospitalization, emergency room visits or deaths. We will also look at recovery times and whether these medications reduce the chances of getting long COVID and its side effects.”

The study has been approved by Health Canada and supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Public Health Agency of Canada. It features more than 90 investigators, staff and patient partners, something he calls “a real team effort.” The team has a communications plan to disseminate pre-prints of their findings as quickly as possible.

Dr. Pinto wants the platform to be accessible to people beyond the research who have treatment ideas and there will be a committee who studies their proposals. Over the long term, he hopes that CanTreatCOVID will grow into a platform that encompasses other respiratory conditions such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, becoming CanTreatResp and helping public health prepare for future pandemics.

Dr. Gupta, his colleague, doesn’t doubt the future success and growth of CanTreatCOVID after seeing how he has assembled the team at the lab.

“We’ve grown over time and his ability to manage that speaks to his capacity as a leader,” she says. “He’s trying to develop a sustainable system of researchers so that the lab is bigger than one person—an organism that can perpetuate. It’s not a one-man-show. We’re all part of a team working toward a common vision. He’s developing a living entity.”

What is Paxlovid?

Paxlovid contains two antiviral medicines, nirmatrelvir and ritonavir, which are co-packaged together. Paxlovid stops the virus from multiplying in the body. Paxlovid is used in adults to help people overcome COVID-19 infection and recover faster.

A study involving more than 185,000 patients with COVID-19 showed Paxlovid reduced rates of hospitalization or death by 78%.

Source: Q Zheng et al. Efficacy and safety of Paxlovid for COVID-19: a meta-analysis. J Infect 86.1 (2023): 66–117.

19 2023 Family Medicine Report – Leadership

FEEDBACK LOOP DR. PETER SELBY USES PATIENT-CENTRED APPROACH AND CONTINUOUS LEARNING TO ENHANCE TREATMENT FOR TOBACCO ADDICTION

By Elaine Smith

By Elaine Smith

Illustration: Pui Yan Fong 20 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

Dr. Selby, the Vice-Chair, Research, for the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto, is a Senior Scientist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) and the principal investigator and director of its Nicotine Dependence Service, a project that first began in 2005–2006. He is also the driving force and principal investigator behind its Nicotine Dependence Clinic (NDC), Ontario’s STOP (Smoking Treatment for Ontario Patients) program and the TEACH (Training Enhancement in Applied Counselling and Health) program.

The TEACH program offers continuing education and is aimed at capacity-building by training health care providers to support their patients with tobacco addiction and cessation, and address e-cigarette use or vaping. Taken together, these components also form the basis for

the Learning Health System that informs the treatments used by both clinic and STOP practitioners.

“Many family medicine problems had common causes, including smoking,” Dr. Selby says. “About four million Canadians smoke and it’s killing about 45,000 every year. However, when treating patients for other conditions, such as COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), high cholesterol or blood pressure, the benefits are wiped out if the person continues to smoke. In addition to preventing numerous chronic diseases, ongoing smoking harms almost all of them. As family physicians we also see the harms of smoking in pregnancy and the effects of second-hand smoke on children in our practice. Governments were also waking up to see smoking’s connection with other illnesses, but there were no leaders to take this on using this approach.”

Dr. Peter Selby has big goals: helping people to stop smoking successfully and continuously improving the system that makes this possible. Even bigger is the news that he’s succeeding.

21 2023 Family Medicine Report – Leadership

Dr. Selby has become that leader.

“We needed to research and create a separate system, since no single treatment seemed to work,” he says. We’ve created a system to look at who smokers are and treat them based on the context of their lives. With data, we could see that many smokers are also dealing with poverty, mental health conditions, drinking to excess, or other conditions. We looked at what we could add as additional interventions and supports.”

The result has been the provincewide STOP program, in addition to the CAMH Nicotine Dependence Clinic. The CAMH program is site-specific and focused on the hospital’s outpatient population, creating individual treatment plans and offering individual and/or group counselling supports. STOP, meanwhile, is a provincewide tobacco cessation treatment program funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health, and delivered either through local Ontario-based healthcare providers, or online via the STOP on the Net program. Smokers or vapers who qualify receive nicotine replacement therapy like gum and patches, and counselling supports.

“We created a system that we could scale up across the province,” says Dr. Selby.

STOP is available at more than 300 sites provincewide through collaborations with family health teams, community health centres, Aboriginal health centres, nurse practitioner-led clinics and addiction and mental health agencies. As of January 2023, STOP has treated 346,000 people across Ontario. People who participate in STOP are eight times more likely to quit than if they attempt to stop using tobacco unassisted.

Given the challenges of in-person interactions during the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Selby and his team initiated STOP on the Net, an online version of the program that is now a permanent option, given its popularity and effectiveness.

“We pivoted to provide services that people could access safely and virtually and the enrolment numbers continue to grow,” says Eva Huang, a CAMH knowledge translation specialist.

Adds Dr. Selby, “We created STOP on the Net to assist a workforce under strain. Since it is delivered directly to the smoker [or vaper], they can enrol themselves and reduce pressure on health-care providers. It’s all about improving population health by empowering people to take action.”

22 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

Dr. Peter Selby, Vice-Chair, Research at the Department of Family and Community Medicine, is Director of the Nicotine Dependence Service at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

STOP has a small footprint, he notes, needing little space of its own. Dr. Selby and his team explore the needs of the setting and create training programs tailored to their populations. These include initiatives targeting women and youth and efforts targeting homeless shelters or Indigenous communities.

STOP sites and the NDC provide Dr. Selby and his team with data about the success or failure of various interventions, as well as patient demographics; they form the basis for a learning health system. It is a system that relies upon continuous cycles of research, analysis, development and implementation of improvements to achieve better health for individuals and improved performance for health care systems.

“As I did traditional research, I recognized that making changes to frontline services took years,” says Dr. Selby. “We needed to take the current problems our patients are facing and rapidly develop solutions that we could simultaneously study and deploy in real-world settings.

“This is an adaptive learning system. We learn what works, create and adapt. The research setting is often different than the real-world setting. We look at the real-world settings and see what’s required to get the outcomes a site needs and make sure what is offered fits with their DNA. We offer intelligent research and support to do it.”

Nadia Minian, PhD, is an implementation scientist with the Nicotine Dependence Service and an assistant professor at DFCM. She is heavily involved in its learning health system and knowledge translation.

“These are evidence-based smoking cessation programs,” Dr. Minian says. “We collect data to see how well the programs are working, then make adjustments. Every time a participant enrols, we collect baseline data to match with treatments and look for trends and gaps. Everything is evidence-based.

“We either identify gaps in the literature and data or hear from our own partners. If we need to develop specific resources, there is also TEACH training and tools to assist patients.” TEACH is also led by another member of DFCM, Rosa Dragonetti. It is an award-winning program with a community of practice that has demonstrated the impact of this training model on patient level outcomes.

Dr. Selby says that a sound learning health system can help planners make health care service decisions. He and his team are currently collaborating with Diabetes Action Canada to determine how the model can provide integrated mental and physical health care to people with diabetes.

“A good learning health system that is designed for the patients and clinicians should make a difference in health system planning and evaluation,” he notes. “It connects various siloes and gets them to work together on an alignment of purpose, and family medicine should be at the centre of a good learning health system, since family physicians co-ordinate whatever patients need.”

10% of Canadians report smoking cigarettes on a regular basis.

Vaping is more prevalent among younger adults than older age groups.

Smoking is more prevalent among men than women, with 12% of men reporting they were current smokers compared with 9% of women.

23 2023 Family Medicine Report

Source: Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, 2021

24 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

Dr. Don Melady (right), an Associate Professor at DFCM and an emergency medicine physician, reviews a CT head scan with a resident, prior to digitization of diagnostic imaging.

‘WE WATCH TEACHERS GROW’ LEARNING PARTNERSHIP WITH ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY YIELDS ETHIOPIAN LEADERS IN EMERGENCY MEDICINE

By Elaine Smith

Dr. Whynot was in Ethiopia’s capital city for an elective during her emergency medicine fellowship with the University of Toronto’s Department of Family and Community Medicine (DFCM).

“We learned to work around issues like these,” says Dr. Whynot. “Working as part of the Toronto Addis Ababa Academic Collaboration in Emergency Medicine (TAAAC-EM) was eye-opening. I got so much out of it, but first and foremost was insight into what emergency medicine looks like and how things work in a resource-limited setting.”

TAAAC-EM began in 2010, as one of the many offshoots of an initial collaboration with Addis Ababa University (AAU) begun in 2003 under the leadership of Dr. Clare Pain, an associate professor of psychiatry at U of T, and psychiatrists at AAU. Drs. Megan Landes, head of DFCM’s Division of Emergency Medicine, and James Maskalyk, a TAAAC-EM strategic director, were the inaugural co-directors of the program.

“Addis Ababa University approached U of T with several priority areas for expansion and one of the first was emergency medicine,” says Dr. Landes. “James and I worked really closely with Clare to ensure we were implementing a partnership built on an ethical, thoughtful way of engaging across the North-South divide. We’d seen partnerships elsewhere, some done well and some done poorly, and we wanted to make our partnership a model of how you can engage in a truly bilateral fashion.”

At the time, Ethiopia had no training available for an emergency medicine specialty, and TAAAC-EM was created to meet that need by assisting AAU in building its own emergency medicine residency program. Faculty from the Division of Emergency Medicine at the DFCM and Department of Medicine (DOM) travelled to Addis Ababa three times a year, for a month at a time, to hold training sessions for residents. Teaching trips covered a longitudinal, three-year curriculum through didactic teaching sessions, practical seminars,

25 2023 Family Medicine Report – Leadership

While working in an Addis Ababa emergency room, Dr. Sarah Whynot recalls being shocked to discover that there was a shortage of paper for the ECG machine.

point-of-care ultrasound, simulation and bedside clinical supervision. One or two emergency residents from DFCM or DOM with an interest in global health joined the trips as one of their residency electives, working in the emergency room alongside AAU residents and/or assisting with teaching.

The original goal of TAAAC-EM was to assist in the graduation of a self-sustaining critical mass of emergency medicine leaders at AAU who would continue to train future generations of Ethiopians, and spread emergency medicine expertise throughout the country and East Africa.

“For the first three-to-five years, U of T faculty did the bulk of the training,” says Dr. Eileen Cheung, a family and emergency medicine physician who travelled to Addis Ababa in 2014 as a resident and has since been there twice as a faculty member. She is now the program’s director of education and programming, working closely with Dr. Jennifer Bryan, TAAAC-EM’s director of operations.

“Now, the graduates of the residency program have assumed larger teaching roles.

“We had planned to make that transition and our inability to travel during the COVID-19 pandemic sped some things up and slowed some things down. Our Ethiopian colleagues now do the didactic teaching, but we haven’t handed over all the teaching. On our trips now, we run workshops and simulations and the faculty want continuing professional development, which would be the logical next step,” says Dr. Cheung.

Dr. Landes adds, “TAAAC-EM is a true expression of what we do as educators; we watch teachers grow.”

The collaboration began with a class of just six Ethiopian physicians. The current class of TAAAC-EM residents has 25 physicians. In addition, graduates of the residency program have started at least three similar programs in other Ethiopian hospitals, says Dr. Cheung. To date, there are 82 graduates of the emergency medicine residency practising in 13 hospitals across Ethiopia and there are 42 others in training. There are also graduates employed in high-level positions in Ethiopia’s Ministry of Health.

Suturing workshop with AAU EM residents using pigs’ feet.

26 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

(Left to right:) DFCM Associate Professor Dr. Dominick Shelton with Dr. Tilahun Jiru and Dr. Woldesenbet Waganew.

“There is a more than 95 per cent retention rate of these physicians in Ethiopia’s public medicine system,” Dr. Cheung notes. “That’s unprecedented. It speaks volumes.

“The key to building capacity at this level is providing in-country training to avoid a brain drain. I am continually blown away by the capacity of Ethiopian physicians. It’s interesting how far things have come, since Ethiopia didn’t have an emergency medicine specialty at all before TAAAC-EM.”

She anticipates the TAAAC-EM partnership will continue to change as the needs at AAU change.

“TAAAC-EM is a model that can be replicated elsewhere. Queen’s University is now with Haramaya University and the University of Calgary is involved in Uganda. Ethiopians are now seen as emergency medicine leaders in East Africa. The first two South Sudanese TAAAC-EM residents have just graduated in Ethiopia with the idea of returning home to have an impact. AAU can now be their own experts in helping other African countries build emergency care capacity and U of T could facilitate and mentor other universities in becoming engaged.”

Notes Dr. Landes, “There is still a role for the partnership, but it will change over time. A lot of us feel we have created deep friendships as a result.”

Dr. Cheung is very proud of the program’s success.

“It is rewarding to see the growth in emergency medicine in Ethiopia and how it has evolved differently than it has in

Canada; the pathology and structure are so different,” she says. “Meanwhile, we are also building a cadre of Canadian instructors who understand global health engagement in a longitudinal model. I love the model and medical education in general.”

Dr. Landes believes the TAAAC-EM program emphasizes humility in global health.

“There are often a lot of colonial overtones to global engagement, but so much bi-directional learning has happened through TAAAC-EM,” Dr. Landes says. “Our Canadian residents and physicians learn to practise in a different context, understand complex disease management, learn to work in a low-resource setting and to teach across different cultures. It makes us better physicians and we bring these lessons back to our own emergency departments.”

Seven DFCM residents have participated to date, along with 25 DFCM faculty members, and Dr. Whynot confirms that learning during a TAAAC-EM residency goes both ways.

“I was both a learner and a teacher,” says Dr. Whynot. “It is hard to be engaged in global health work without understanding the day-to-day issues. I learned a lot clinically from the Ethiopian physicians because they see diseases we don’t see here and I improved my own skills as a teacher in teaching simulations and getting feedback.

“It was a helpful growth experience and increased my desire to be part of global health initiatives throughout my own career.

82

25 DFCM faculty members have participated in the TAAAC-EM program.

graduates of TAAAC-EM practicing in 13 hospitals across Ethiopia

27 2023 Family Medicine Report – Leadership

COMM UNITY

28 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

SPEAKING THEIR LANGUAGE CREDIT VALLEY FAMILY HEALTH TEAM MEETS COMMUNITY’S URGENT NEED FOR PRIMARY CARE IN FRENCH

By Alisa Kim

Research shows people do better when they receive medical care in their primary language.

Astudy published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal in 2022 shows people who speak languages other than English are up to 54% less likely to die or have other severe health outcomes when cared for by a doctor who speaks the same language as them.

“There are many benefits to patients’ health when they are served in their first or maternal language,” says Dr. Kerrie Shaw, a faculty member of the Department of Family and Community Medicine (DFCM) and a physician at the Credit Valley Family Health Team’s bilingual site which cares for Francophone patients.

L’Équipe de Santé Familiale Credit Valley was established in 2012 to serve French-speaking residents of Ontario’s Peel and Halton regions. Under the French Language Services Act, these are designated areas in which access to primary health care in French is guaranteed.

Being attached to a Family Health Team has significant benefits. Family health teams specialize in proactively managing chronic conditions like depression, asthma, diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder. They are recognized for their expertise in health promotion including weight management, smoking cessation and newborn wellness.

Dr. Paul Cheung, who is also a faculty member of DFCM and a family doctor at the Credit Valley Family Health Team’s bilingual site, says the clinic serves about 2,100 patients. It is one of just a few Francophone Family Health Teams in Ontario Health’s Central Region, an area that serves more than five million people. Dr. Cheung notes some of his patients come from as far away as Hamilton or Belleville to receive primary care services in French because it is an urgent need. The interprofessional team includes three family physicians, a nurse practitioner, registered nurses, a dietician, social worker and a diabetes specialist team—all of whom speak French.

29 2023 Family Medicine Report – Community

Dr. Cheung, who was born and raised in Quebec and did his medical training in French, notes patients of the bilingual site have diverse backgrounds; many are Canadians, but they also hail from Europe, Africa and the Caribbean. “Our patients describe their care as ‘one-stop shopping,’” he says. “We are bringing everything we’ve done well in team-based primary care in French. Our patients benefit from a team of bilingual health care providers who promote wellness and manage chronic disease together in our journey to offer high quality comprehensive care to the Francophone population.”

Dr. Sandra Toutounji is the clinic’s third family physician. She completed her residency at DFCM in 2020 while working at the Credit Valley Family Health Team’s bilingual site. She, like other residents and clerks, was drawn to the site for clinical training in French. For Dr. Toutounji, who grew up in Mississauga and attended French elementary and high schools in the area, working there as a staff physician is a full-circle moment. “I love this community. I find it’s a rewarding patient population. They’re quite appreciative for the care in their primary language. It’s special to be able to provide that care,” she says.

Dr. Toutounji’s former teachers and other staff of her high school are also patients of the clinic, which speaks to its connections to the local Francophone community. “Whenever new immigrants get here, they’ll choose a francophone school for their kids. The principals or leadership of the school board know us and direct them to us to get their

vaccines updated and health care needs taken care of,” says Dr. Cheung.

He recalls one patient in particular—a pregnant single mother who was a refugee. She was referred to the clinic by the principal of her children’s French school. Over time, the patient was able to set down roots, trained as an early childhood educator and now works as a teacher. “We managed her medical care and helped her settle in the community in collaboration with our team and social services agencies. Our patients feel safe here and they feel like they get complete care,” says Dr. Cheung.

In addition to the clinic’s ties with the local French school boards, it also works closely with community organizations. For example, staff at the clinic refer patients to Oasis Centre des Femmes, a Francophone organization that helps women and children experiencing domestic violence. In turn, the centre refers its clients who are in need of a family doctor to the clinic. “I think because the francophone resources and services that exist are so sparse, you really do have to work as a community to maximize what’s out there,” says Dr. Shaw. “We can provide preventive care, update vaccinations, screen for diabetes and all the great stuff family doctors do, but we also have to be mindful of the social determinants of health and whether this person is connected with different community resources, or their kids are in school. Everything we do is at the level of the community because it is very hard to find services in French.”

30 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

[Left to right:] DFCM faculty members Drs. Sandra Toutounji, Kerrie Shaw and Paul Cheung are physicians at the Credit Valley Family Health Team’s bilingual site, which offers primary care services in French to the clinic’s 2,100 patients.

Caring for patients in their primary language is gratifying, but can also be tricky at times, says Dr. Shaw. “It definitely adds a layer of challenge—oftentimes patients may not understand specialists’ recommendations. You have to spend more time explaining things,” she says. For Dr. Toutounji, who did not do medical school in French, taking care of Francophone patients was initially daunting. Still, she encourages trainees who speak French—even if they are rusty—to pursue clinical opportunities working with Francophone patients as the experience is deeply rewarding. “Patients are so appreciative. Even in those tough conversations where I’ve had trouble finding the words, they’re able to get their feelings across so much more easily and feeling heard in their language means so much to them. Even when I have to use the odd English word here or there—I struggle a bit more with those conversations—it still goes a long way. It’s normal for people to feel anxious if French is not their first language, but I would encourage them to pursue it.”

Where

were

French-Speaking Immigrants in Ontario born?

622,415

Ontario has the largest Frenchspeaking minority community in Canada

2,100

Francophone patients cared for by the Credit Valley Family Health Team’s bilingual clinic

French is the mother tongue of 4% of Ontario’s population Americas Africa Europe Asia 17% 37% 27% 20%

Source: Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages

31 2023 Family Medicine Report – Community

HAVE A HEALTH CONCERN? CALL AUNTIE

By Alicia Fung

By Alicia Fung

32 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

When

You might turn to your family doctor—a trusted primary care provider with whom you have built a relationship over time and knows your specific health needs. But what happens when you don’t have a family doctor you trust? Or crucially, what happens when you can’t trust the health care system as a whole? This is the case for many Indigenous people in Canada.

Indigenous people regularly experience racism, stigma, stereotyping, and discrimination in health care. An independent investigation performed in the B.C. health care system in 2020 found that 84% of Indigenous people surveyed reported experiencing some form of discrimination in health care. The same investigation also found more than one-half of the Indigenous health care workers surveyed reported they had personally experienced racism in their work environment because of their Indigenous identity.

But this isn’t unique to B.C. According to the Our Health Counts Toronto research project, more than one in four Indigenous adults reported that they have been treated unfairly by health care professionals because of their Indigenous identity. Of the Indigenous adults who have reported unfair treatment, 72 per cent indicated that it had occurred more than once in the past five years.

These harmful experiences have turned many Indigenous people away from accessing the health care they need, says Dr. Suzanne Shoush, a First Nations and Black family physician, and the inaugural Indigenous Health Faculty Lead at the University of Toronto Department of Family and Community Medicine. “We know that anti-Indigenous racism is prevalent. The Our Health Counts data shows that 71% of Indigenous adults in Toronto have said that experiences of racism from a health care provider have either stopped, prevented, or delayed them from seeking follow-up health care,” she explains.

But this comes as no surprise—when negative experiences in the health care system outweigh positive ones, it’s unlikely that you will go to get the care you deserve.

you have a health issue, whom do you go to for help?

33 2023 Family Medicine Report – Community

DFCM faculty Dr. Suzanne Shoush co-founded the Call Auntie Clinic, which provides primary care grounded in Indigenous ways of knowing and being.

“Primary health care is a great concept and model, but the way that it currently exists can be very uncomfortable for people who have been treated poorly by institutions— which is a common experience for Indigenous people,” says Cheryllee Bourgeois, a Métis midwife at Seventh Generation Midwives Toronto.

All of these negative experiences accumulate over time, inducing the systemic exclusion of Indigenous people from the health care system—an exclusion that became much clearer and more profound when COVID-19 hit. But that’s not all. Health disparities experienced by Indigenous communities were also magnified in the pandemic, and it was clear that this was a group who would face more dire consequences from COVID than others.

“Whenever there are gaps in health care or a crisis impacting health care, it will always impact Indigenous communities disproportionately. So, when there was an abrupt shutdown of public health care services due to COVID, we were very worried. These are communities that already have less access to primary care than others and often have no health care provider whatsoever. So, we were worried about the disproportionate exclusion, about stigma, about barriers to accessing testing and information, about social isolation—the list goes on. And there was this heightened fear among the Indigenous community during the pandemic about where it was safe to go, what to do, and who to turn to,” says Dr. Shoush.

Data from the Our Health Counts survey speak to inequitable access to primary care. Results show 63% of Indigenous adults in Toronto have a regular family doctor or nurse practitioner compared to 90% of adults in Toronto who have a regular physician.

To address this exclusion during a critical time, Ms. Bourgeois and Dr. Shoush started the Call Auntie COVID-19 Indigenous Pathways Hotline in April 2020, a COVID information hotline focused on supporting Indigenous communities staffed by Indigenous health experts called “aunties.” The hotline’s name comes from the cultural concept of calling your auntie: a trusted relative —whether blood-related or not—who you can turn to whenever you’re facing difficulty.

“In the Indigenous community, when you’re in trouble, trying to figure something out, or just don’t know what to do next, you call your auntie—somebody you can actually trust. Somebody you know is reliable, consistent, available, and will drop everything to help you,” says Ms. Bourgeois.

Initially, the hotline was meant to be a COVID information resource for Indigenous people and their families who were having trouble navigating the healthcare system. They could “Call Auntie,” and the aunties would provide expert advice about COVID and how they could protect their health and that of their families. But soon, people began calling the aunties for more than just pandemic information.

“People started calling us for things like, ‘I can’t get birth control,’ ‘I can’t get my blood pressure medication,’ or ‘I’m having a mental health crisis’—things that were so bread and butter primary care, that we ended up saying, ‘Ok, let’s open an in-person clinic,’” says Dr. Shoush.

In September 2020, Call Auntie expanded their services to include the full scope of primary care for Indigenous people and their families. But, unlike other primary care clinics in the city, the Call Auntie Clinic takes an Indigenous kinship approach to providing primary care.

34 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

“People started calling us for things like, ‘I can’t get birth control,’ ‘I can’t get my blood pressure medication,’ or ‘I’m having a mental health crisis’—things that were so bread and butter primary care, that we ended up saying, ‘Ok, let’s open an in-person clinic.”

“This idea of kinship care pulls from teachings and kinship systems that already exist in Indigenous communities to support community wellbeing. It’s this idea of shared responsibility for caring for the community because it doesn’t always make sense to have one person who is the expert at meeting the needs of every other person,” says Ms. Bourgeois.

This shared responsibility of care means that the Call Auntie Clinic is a truly team-based model: every auntie on the team is an equal provider and patients can choose who they feel safest with as their pathway to care. Patients can come to receive any primary health care service including reproductive health, harm reduction, pregnancy and postpartum support; they can also come in for food, traditional medicines or for advice around difficult family or community situations.

“The lack of culturally safe care is the largest barrier to healthcare for Indigenous people, so creating these community-based Indigenous-led safe spaces as entry points to care are essential in lowering barriers and creating a for-us, by-us existence within medicine. With Call Auntie, you could come into a very safe space that was very different from hospital spaces and hospital clinics—different from a lot of the way primary care exists in the city. The

More than 1 in 4 Indigenous adults have reported that they have been treated unfairly by health care professionals because of their Indigenous identity

Of the Indigenous adults who have reported unfair treatment, 72% indicated that it had occurred more than once in the past five years.

71% of Indigenous adults in Toronto have said that experiences of racism from a health care provider have either stopped, prevented, or delayed them from seeking follow-up health care

centre of care is the patient, and they can come in and speak to anyone on the team as an entry point into care. Patients can come at a time that works for them and they’re not turned away if they’re ‘late.’ They can come and get traditional medicine. They can come just to get food or a drink if they want—because care doesn’t only mean caring for physical health,” Dr. Shoush explains.

Two years later, the Call Auntie Clinic has a small but mighty team of nine aunties and continues to provide culturally safe care to Indigenous communities across Toronto, improving access to primary health care for a group that has great unmet need.

“By using the systems of culture we know and are used to, we can create entryways and lower barriers to access for a community that we know doesn’t engage in health care in the same way,” says Ms. Bourgeois. “It’s not enough to assume that people don’t have family doctors and having one is the solution. You have to get people to the point where they’re even willing to consider having a relationship with a family doctor—and sometimes that can take a little work. So, our goal is to try and create spaces where people can practice being involved in primary care in a way where they feel comfortable.”

Cheryllee Bourgeois, a Métis midwife and co-founder of the Call Auntie Clinic, examines a pregnant patient.

35 2023 Family Medicine Report – Community

Source: Our Health Counts Toronto

BRINGING THE WINDS OF CHANGE TO TORONTO’S PRIMARY CARE ‘DESERT:’ HUMBER RIVER HOSPITAL JOINS DFCM AS THEIR NEWEST TEACHING HOSPITAL SITE

By Alicia Fung

By Alicia Fung

For some Torontonians, the most notable thing about the northwest region of the city is Yorkdale Mall, a two million square foot shopping centre that is home to an exclusive lineup of luxury brands and boasts itself as “Toronto’s ultimate shopping destination.” Yorkdale attracts both local and international visitors to Toronto’s northwest and even has a subway station named after it.

But don’t let the extravagance fool you—the same neighbourhoods that house one of Canada’s largest collections of designer brands also houses some of the city’s most socially and economically disadvantaged populations. Over the years, the residents of Toronto’s northwest neighbourhoods have been identified by several reports from Public Health Ontario and the City of Toronto as some of the most impoverished and materially deprived neighbourhoods in the city. These regions also have an aging population with a higher proportion of racialized groups, greater housing density, as well as some of highest rates of crime and lowest rates of post-secondary education completion.

These intersecting inequities have a compounding effect on health. Studies have shown that social and economic factors—also known as the social determinants of health—account for anywhere between 80 to 90 per cent of health outcomes. Health is about more than just access to health care services; the environment and circumstances in which we are born, live and work greatly impact our health and wellbeing. Family physicians can look to their own practices to see clear evidence of this.

“Throughout my practice in the Jane and Finch neighbourhood I have witnessed how social determinants of health impact patient care. It is a challenge for some patients to afford medication, physiotherapy, or even take time off work for specialists’ appointments,” says Dr. Ryan Banach, a family physician practicing in Toronto’s northwest and the Family Medicine Health Human Resources Lead in the Office of Health System Partnership at the University of Toronto Department of Family and Community Medicine (DFCM).

Given that Toronto’s northwest communities face some of the most inequitable outcomes in the city, it comes as no surprise that they were also among the hardest hit by COVID-19. At the start of the pandemic, the rate of COVID-19 was more than 10 times higher in these neighbourhoods than in the least-affected Toronto neighbourhoods. Moreover, despite being disproportionately affected by the pandemic, vaccine rollout in these neighbourhoods was much slower than other areas of the city.

36 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

On top of this, Toronto’s northwest has also been described as a primary care desert: there is clearly a great need for primary care in the region, but there are a low number of primary care physicians available to address those needs. Dr. Banach notes this may be due to a rising share of family physicians who are now retiring or near-retirement age.

“I have noticed recently that more physicians in our area are retiring, leaving many patients looking for new family physicians. Most of the family physicians I know in my area have been practicing for 30 to 40 years and are generally older physicians,” he says.

“There isn’t a lot of interest from new family physicians to move into this community,” says Dr. Art Kushner, Chief of the Department of Family and Community Medicine at Humber River Hospital (HRH), one of the hospitals serving the northwest communities of Toronto. “And as family physicians retire, attachment rates will decrease.”

Only between 11 and 25 per cent of the patient population in the area are attached to a family doctor or family health team. Between low attachment rates, low supply of incoming physicians, and retiring physicians, patients in the area are now finding themselves struggling to access comprehensive primary care.

To address what is quickly becoming a dire situation in primary care in the area, HRH recently joined DFCM as their newest teaching hospital site. The hope is that incoming residents would become a continuous source of new doctors for Toronto’s northwest communities.

“Studies have shown that physicians are more likely to set up their practice in the communities they were educated and trained in. Since they become familiar with the community, the patients, the hospital and the specialists, it’s more comfortable for them to set up practice there after they graduate,” says Sudha Kutty, Vice-President of Strategy and External Relations at HRH.

Humber River Hospital will welcome the first cohort of family medicine residents at their Wilson site in July 2023. Residents can expect to learn from award-winning physicians and experience working in a diverse community—both in their needs and their makeup, says Upasana Saha, Director of Integrated Health Systems and Partnership at HRH.

“This is clearly an equity-deserving population, but that’s not all there is to it. Beyond that is a vibrant community that comes alive through its diversity, and there are a lot of great opportunities for residents to get exposure to many different patient populations and learn how they can serve them better,” says Ms. Saha.

Residents can also expect to work with leading edge technologies. Humber River Hospital prides itself on being North America’s first digital hospital and is consistently at the forefront of innovation. For example, its department of surgery makes use of robotics, which have allowed the hospital to treat more patients in less time with better outcomes. Additionally, its state-of-the-art command centre allows for real-time analytics and tracking of patient care. Residents will have the opportunity to learn and practice with these technologies during their rotations.

Innovation is embedded in HRH’s mindset, and the hope is that incoming residents will embrace this culture of innovation. Dr. Abhimanyu Sud is the Research Chair in Primary Care and Population Health Systems at HRH, a role that creates an important link to scholarship and aligns with DFCM’s interest in community research.

“Our communities need residents and their support,” says Ms. Kutty. “So we’re hoping that incoming residents will take an active role in helping us shape the future of family medicine education and primary care at Humber River.”

37 2023 Family Medicine Report – Community

Gaps in Primary Care Areas of the city with higher primary care needs but surrounded by lower physician supply are clustered in the northwest.

PRESCRIBING BETTER “PILLS” TO SWALLOW

By Alicia Fung

38 Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto

Avisit to your family doctor may end with a prescription for medication. But what if, instead of medication, you were prescribed a choir class?

This was one of the unconventional prescriptions that Nafisa Nezam Omar had received from her family doctor at Rexdale Community Health Centre (CHC). But perhaps an unconventional prescription was just what Nafisa needed, considering her journey in coming to Toronto.

Nafisa and her daughter came to Canada from Kabul as asylum seekers in 2017. After losing her sister and her home to a rocket attack, her brother to gunfire, and her husband to a heart attack, she packed her life into one suitcase and fled the country with her daughter. The grief of losing her loved ones and everything she once knew, compounded with the stress of starting anew in an unfamiliar country, took a heavy toll on Nafisa’s health.

“A few weeks after I came to Canada, I found this small space in the basement of a bungalow house. There weren’t any bedrooms—it was just a small room. I looked at what I had compared to what I had in Kabul, and I missed my parents, my brothers and sisters, my loving husband, my job—everything. And after living in Toronto for 10 months, I lost 15 kilograms of weight. My family doctor was really concerned, sending me for every kind of examination thinking that it was possibly cancer,” says Nafisa.

After several consultations and examinations, Nafisa was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. She was prescribed anti-anxiety medication, antidepressants and sleeping pills, among other medications to help her manage her health. Despite this, nothing seemed to help. In fact, to Nafisa, it seemed that the medicines were making her feel worse, making it even more difficult for her to provide for herself and her young daughter in a new country.

“I was taking so many medicines and each one of them has its own side effects. I put them all in front of me and just looked at them, thinking that although I’m living with the

help of all these medicines, it’s giving me more pain and depression,” she says. “But it wasn’t just me having a hard time—all of this really affected my daughter as well. She was only 10 years old when we came to Canada and she was also suffering. She was being bullied in school, her marks were bad, and she was looking to me for support but I couldn’t help her because of my health.”

In 2018, Nafisa finally received a prescription that made all the difference. It wasn’t a prescription for more medication, but rather, a social prescription. But what exactly is a social prescription?

Health is not only influenced by genetics, biology, and lifestyle, but also by a broad range of social, environmental and economic factors. These factors are collectively known as the social determinants of health. Research has shown that the social determinants of health can have a greater impact on health than individual biology, driving between 80 to 90 per cent of health outcomes. Yet, while many primary care professionals are aware of this fact, it can seem difficult to address social needs in clinical practice. Social prescribing helps health professionals support their patients by giving them the tools to formally connect social care and clinical care. By meaningfully “prescribing” social services and resources as they would medicine, primary care professionals can practically address the social needs of people in their practices.

39 2023 Family Medicine Report – Community

“Primary care professionals are in a position to recommend community and social services that can help to improve their patient’s health.”