6 minute read

Ab urbe condita

Ab urbe condita

Most ancient cities derive their fortune from the uniqueness of their geographical position: rivers, hills, islands and natural resources play a key role in shaping the future development of any urban settlement. However, very few cities share the historical and cultural destiny of the City of Rome, where geographical factors, along with the powerful impetus of the determination of its citizens and their primitive but effective technologies, helped place this urban area at the base of Western civilisation. Notwithstanding various hagiographic reconstructions and mythical accounts, it is impossible to establish the exact date of the foundation of Rome, although most modern historians and archaeologists agree that the first human settlements on the Palatine Hill date to around 5000 years ago55 . The site of the foundation of Rome has several crucial characteristics. One of the main crossing points of the river Tiber was located downstream from the Tiber Island. Around the 9th-8th century B.C. tuffaceous hills having the typical morphology of a paleo-volcanic area formed the landscape of the site of Rome56. The hills dominated the lower course of the river, separated by semi-swampy little valleys and crossed by small seasonal streams or Marrane57 that then opened out into a large alluvial plain

Lawler, A. 2007. Raising Alexandria, in «Smithsonian Magazine», April, pp. 3-11. 55 Heiken G., Funiciello R., De Rita D. 2005, The Seven Hills of Rome: A Geological Tour of the Eternal City, Princeton University Press, Princeton. 56 Central Italy, particularly the region surrounding Rome, was a highly volcanic area around 600 000 years ago, dominated by the Albano crater. 57 Marrana (or marana) s. f. [voice of Mediterranean origin], Roman. -

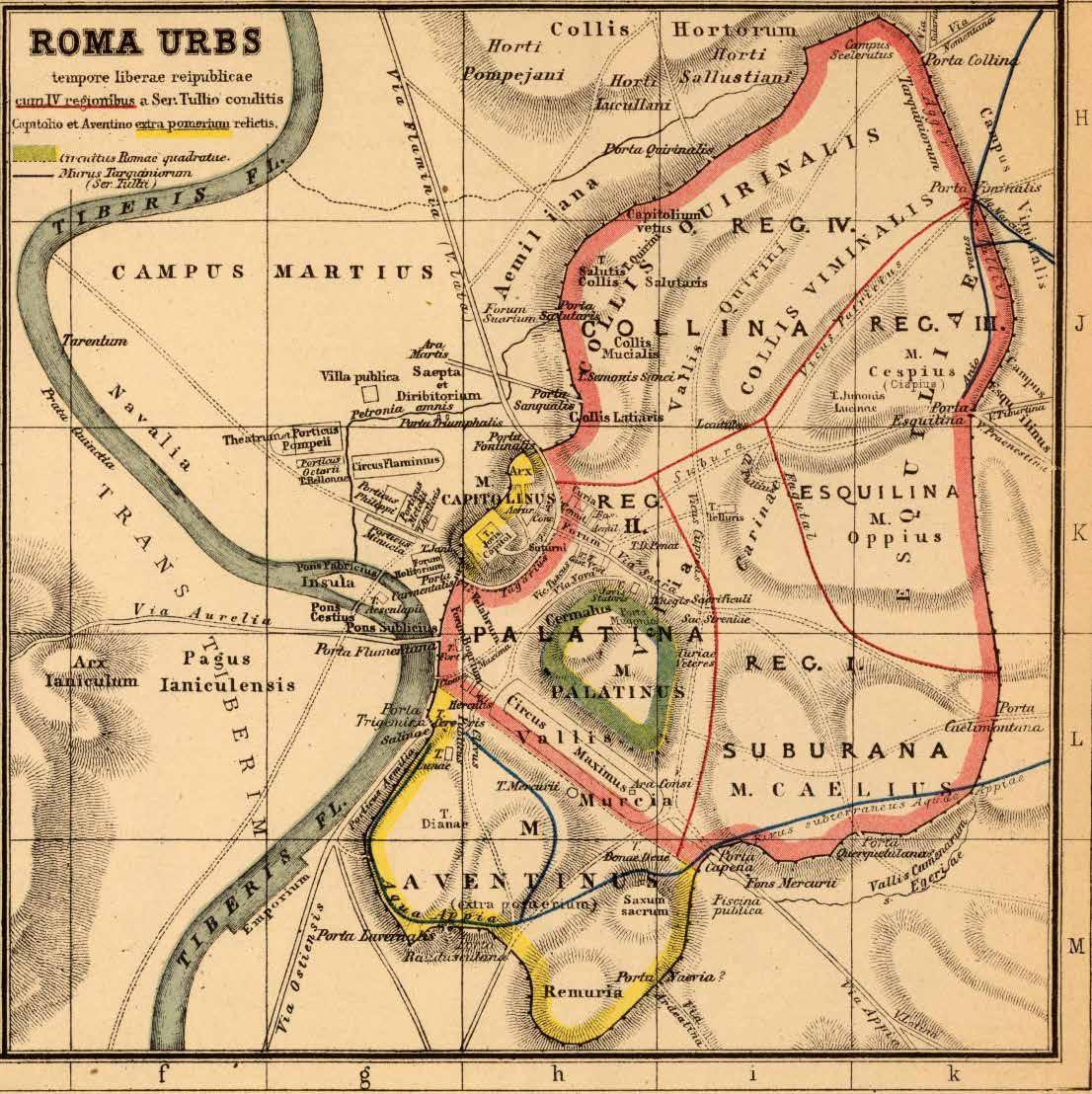

Fig. 12 The ancient plan of Rome. In green in the middle, the so-called Romae Quadratae (Squared Rome, 9th-8th century B.C.) and in light red and yellow the perimeters of the Servian walls (6th-4th century B.C.) (Heinrich_Kiepert (1818 - 899) Roma urbs tempore liberae Republicae, Source: Wikimedia Commons ®)

towards the sea. The transformation of the Capitoline and Palatine hills into small fortresses did not require much effort, considering their natural shape as flat-topped hills with steep and easily defensible slopes. They became the heart of the so-called Roma Quadrata (Fig. 12).

Small brook or ditch with water: up to where the hillock descends in the network of maranas and drains (Luzi); it is a recurring element in various place names around Rome: m. della Caffarella; m. di Grotta Perfetta; m. delle Tre Fontane.

Fig. 13 Plan of the city of Rome in the imperial age (I-III century A.D.) Noveau Larousse Ilustré (Larousse XIXs. 1866-1877).

A fundamental distinction must be made between the urban structure of the city of Rome and that of the cities newly founded or conquered and transformed in the course of the expansion of the Roman Empire. The description of archaic Rome as ‘square’ should perhaps more properly be ‘tetragonous’, in line with the Greek authors who, when describing the foundation of Rome, used the term Tetragonos (Τετραγώνοs) or ‘quadrilateral’ to describe its initial form58. During all Roman history,

58 Tetragonos is a noun that geometrically describes a quadrangular perimeter, which fits well with the roughly quadrangular shape of the Palatine. Maccari A. 2019, Pomerium, verbi vim solam intuentes, postmoerium interpretantur esse. La critica storica e antiquaria e la manipolazione del passato, «Studi Classici e Orientali», n. 65, Pisa.

this form was reflected both in military camps and in the layout of newly founded cities. The squared form:

in a geometric sense [it] was consciously metabolized and materialized in the urban plans of the Roman colonies, giving a historiographic evidence [of the mentality] of the Roman ruling class59 .

The evolution of Rome’s urban structure, from its foundation to the imperial age, is a history of transformations, some of them major, driven by the need to make the city the stage for the Empire’s triumphs60(Fig. 13). The city grew out of all proportion, sprawling outside the walls of the royal age, which roughly enclosed the seven hills. It was only in the 3rd century [a.D.]. that the Emperor Aurelian surrounded the larger Rome with new walls, establishing the outer edge of the city until the Unification of Italy in 1870. Very few cities share Rome’s unique destiny, where the geomorphologic aspects of the territory, combined with the primitive but effective technologies employed since its origin, continue to contribute to its long life and fortune61 . These technologies are essentially based on masonry, i.e. linked to the consolidation of the Palatine and Capitoline hills in the form of the first fortifications, and the excavation

59 Ivi, pag. 143. 60 “Rome was not equal to the grandeur of the Empire and was exposed to floods and fires, but he embellished it to such an extent that he rightly boasted of leaving the city he found made of bricks in marble. He also made it safe for the future, as far as he could provide for posterity”, Suetonius, Divus Augustus, L. 2, paragraph 28. 61 Cinquepalmi F. 2019, Rome before Rome: the role of landscape elements, together with technological approaches, shaping the foundation of the Roman civilization, in «RI-VISTA: Research for Landscape Architecture. Digital semi-annual scientific journal», Firenze University Press, Firenze, pp. 168-183.

of the Cloaca Massima. Both these infrastructures, as well as the archaic perimetral consolidation of the Tiber Island, are in stone masonry, polygonal (Opus Siliceum)62 and square (Opus Quadratum)63. From the point of view of technological innovation the Cloaca Massima is perhaps the most interesting element of archaic Rome. Excavated essentially to drain the waters of the marshy plain of Velabrum and mentioned by almost all ancient literary sources that discuss the origins of Rome, it is described as a masterpiece of hydraulic engineering and attributed to the will of the Etruscan king Lucius Tarquinius Priscus. The conduit was enormous and its main purpose was to rapidly drain the stagnant water left when the Tiber flooded as well as seasonal streams in the area64 65. The next technological element of great impact for the birth and consolidation of Roman power was the construction of the Ponte Sublicio (Pons Sublicius). Located since the origins of Rome downstream from the Tiber Island, at the point where a seasonal ford presumably stood, it was probably built on pairs of piles,

62 Polygonal masonry (Opus Siliceum) widespread in central Italy between the 6th and 2nd centuries B.C. consisted of superimposing unworked stone boulders, even of considerable size, without the aid of binders, grapples or pins. This system was mainly used for terracing and retaining walls. Cinquepalmi, Rome, Op. cit., p. 173. 63 The opus quadratum masonry (Opus quadratum) consisted of the superimposition of square parallelepiped-shaped blocks of uniform height, arranged in homogeneous rows with continuous supporting surfaces. In the Roman area, the technique was already widespread in the 6th century B.C. and was later improved with more regularity of cut and a more articulated arrangement of the blocks. Ibidem, p. 173. 64 Ivi, pp. 175-176. 65 The material of choice was a type of soft-grained tuff, commonly called ‘Cappellaccio’, cut into stones 90 cm long (= 3 feet), 60 cm wide (= 2 feet) and 25 to 30 cm high. Ibidem.