6 minute read

More than a Festival

from DIG MAG Summer 2021

by DIG MAG LB

California State University, Fullerton student Ang Cruz shares their experience attending Pride for the first time.

Advertisement

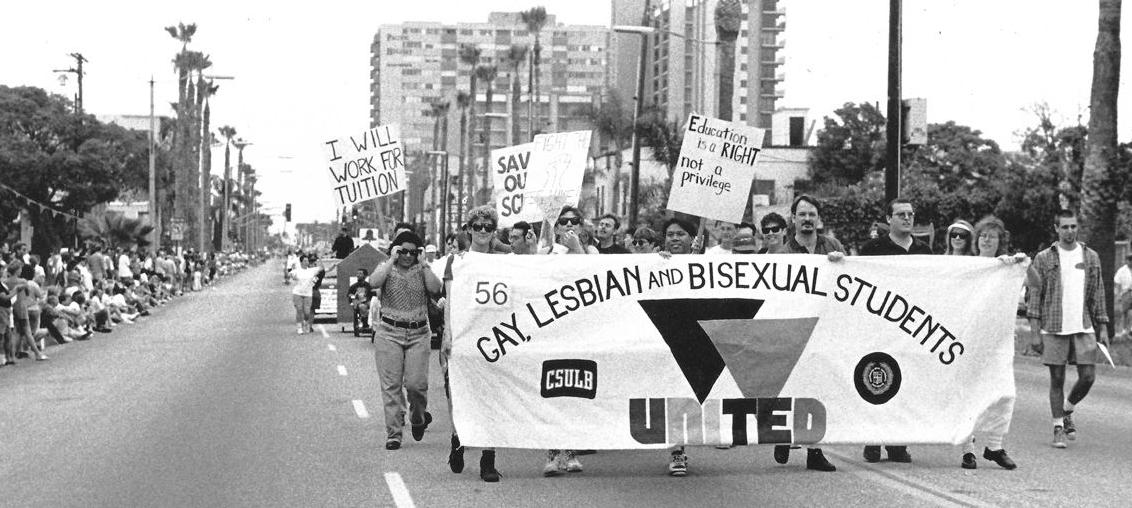

Long Beach Pride in 1994. Photo courtesy of USC Library.

STORY BY

JOEY HARVEY

Another year of Pride event cancellations leave the queer community re-evaluating the meaning behind the festivities.

SHE stood in a crowd of people along the curbside of Santa Monica Boulevard where there wasn’t a single frown in sight. She was with her best friend and the two held hands since they were both anxious, but the smiles from strangers are welcoming. Everyone was happy, and nothing but cheers and applause could be heard as decorative parade floats of every color imaginable slowly made their way down the street.

People marched with rainbow flags in their hands as they waved back to the cheering crowds. It was as if glitter had fallen from the air and into the crowd of that year’s Los Angeles LGBTQ+ Pride parade. It was euphoric for California State University, Fullerton student Ang Cruz. But most important, she felt seen.

“It just felt like I was with a bunch of people who kind of felt the same way I did. Feeling this pride, feeling this moment to reflect on our culture and our history. It was just special to see everyone’s excitement,” Cruz said.

That was Cruz’s first Pride experience, a right of passage for many young queer folks.

However, due to COVID-19 and with the concerns of the health and safety of attendees, many of last year’s LGBTQ+ Pride festivities were canceled, postponed, or converted to online platforms.

According to information provided by the European Pride Organizers Association, over 400 Pride events globally had committed those cancelations or changes in response to COVID-19.

Though some were left disappointed of last year’s cancellations, many queeridentifying individuals realized that there is much more to the message and meaning behind Pride than the scheduled summer month festivities.

In an open letter to the public regarding last year’s festivities, the communications team of Los Angeles Pride, Christopher Street West Association, expressed their reasons for postponing their highly attended Pride festivities. “We understand that you’re disappointed. But please try to see the silver lining in the gravity of this decision: we’re ultimately doing what’s best for our community as a whole,” the Association stated.

They later reiterated that though the festivities would not be going forward, gay pride and gay liberation are a daily

Though some were left disappointed, many queeridentifying individuals realized that there is much more to the message and meaning behind Pride rather than the scheduled summer month festivities.

Robert Cano (right) celebrates with a friend at the Long Beach Pride festival in the late 1990s. Photo courtesy of Robert Cano

occurrence for queer folks. The meaning behind Pride is still and always will be present.

“Pride is more than just one weekend in a year. Or even a month. Pride is something that we live and breathe every day. Whether we celebrate L.A. Pride in mid-June (as we’ve done for the last 49 years) or, for this one specific year, decide to move it to another weekend, our celebration, our voices, our struggles, our triumphs, and our never-ending message for equality never stops.”

Though the annual Pride festivities can provide a safe physical space for queer folk, many argue that the global celebration events have become quite corporate over the years.

In 2019, L.A. Pride had more than 80 sponsors, such as Verizon Wireless, M.A.C. Cosmetics, Bud Light and Skyy Vodka.

Because of this assimilation, many agree that the spaces aren’t as queer as stated. Even before last year’s cancellations, some in the community had stopped attending the festivals and parades altogether. One of these individuals was CSULB women’s, gender and sexuality studies professor Dr. Melissa Hidalgo.

“I think that very often pride kind of gets misconstrued, and especially the one thing about the festival is that it’s just one big party, right? Rainbow capitalism. Corporations are slapping rainbows everywhere, and it’s just another way to make money for capitalists,” Hidalgo said.

Because of this increase in corporatization, Hidalgo argues that the initial origins and histories of Pride have been lost.

“When I think about Pride, I think [about how] there are these histories of protests against police violence, and I think that gets lost I know it gets lost when you see the corporatization of Pride. As long as Pride is corporate, I’m not sure how queer of a space it is anymore,” Hidalgo said.

These origins entail the historical turning points in the gay liberation movement from the Stonewall riots, the Black Cat riots and the riot at Compton’s in the Tenderloin District. These were all

against police brutality, which is why some also feel that federal officials don’t belong at Pride events, because of their historical harms that caused traumas within queer spaces.

Another historical turning point would be the AIDS pandemic, where millions of lives were lost due to the infectious disease and the lack of immediate treatment and response from the federal government. During this time Pride, was a fight to be heard and not even in death would come acknowledgement that these individuals needed aid.

An individual who lived through this was the founder and programmer of the Long Beach Q film festival, Robert Cano.

Though Cano has spent some of his Pride events marching and fighting for visibility and aid, he remembers his first time attending a Pride event and how cathartic the feeling was to see his community so glorious and fluorescent as they came together like kindred spirits.

“When I saw so many people there, I started crying. I was overcome with emotion. Because I had lived so isolated in a bubble and I saw so many people.. whites, Blacks, Asians, and they’re all mixed up. And I saw gay Latinos who were my age. And I just thought, wow, I am not the only one out there. So it was very emotional,” Cano said.

This year, many Pride events are expected to resume in-person, including the festivities in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Others will remain online, like they were last year. As of press time, Long Beach Pride had not determined whether its event would be in person or virtual.

No matter whether the festivities are online or in-person, though, many queer folk agree that it’s all about commemorating the losses and triumphs in the community, celebrating visibility, and coming together.

Cal State Fullerton student Tim Luna, for one, is grateful for Pride events in whatever form they exist.

“I’m so thankful for [virtual Pride events] because in a time like this, I get to interact with friends, and it’s instantaneous, and if this didn’t exist, then I’d go crazy.” Luna said. “I’d say utilize it. Find a queer space online. The beauty of online is that you can be [as] anonymous as you want. You can celebrate that pride, and it doesn’t mean you have to post a pic of yourself in a rainbow shirt, but you know you still get to be among people in your community and culture in any way you choose.”

Cal State Fullerton student Tim Luna enjoys L.A. Pride 2019 with his boyfriend, Uly. Photo courtesy of Tim Luna

— Tim Luna