4 minute read

Wine: The white privilege in the wine industry

The inherent white privilege in the wine industry

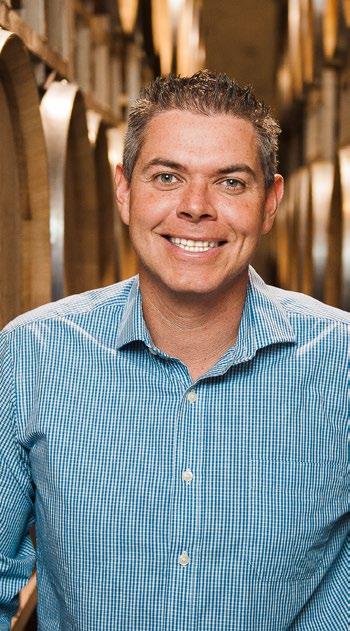

Tristan BragagliaMurdock

Advertisement

Wine is complex . For fruit that goes through fermentation naturally, it sure does have a lot of hang-ups .

Buried under its generations of pretension lies the root issue: racism . At its core, wine holds an overwhelming amount of underlying white privilege, namely land ownership, winemaking, farming and fine dining .

I spoke with industry professionals — Black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC) — who operate their own wineries as well as some from a top Canadian restaurant, about racism, operating within a white-dominant industry and about the steps required to bring about equality and change .

“Racism exists in our industry and it comes from guests as well as colleagues,” says Bernard Joseph-Lemoyne, sommelier at Ottawa’s exclusive fine-dining restaurant, Atelier . A first-generation immigrant from Zambia, he’s been working in restaurants for 15 years and has focused on wine for the past eight years .

Having a position in management has helped in defusing racially ignorant or aggressive situations . Overt displays aren’t the only issue, he says . Rather, it’s the subtle, constant reminders; many times at wine events or seminars, he is the sole Black wine professional . Embracing his position, he aims to make necessary changes to move BIPOC into visible positions within restaurants, be it chef, sommelier or owner .

Rajen Toor, winemaker at Ursa Major in B .C .’s South Okanagan, has grown up surrounded by vines . His family has been farming the Black Sage Bench region for the past 25 years and recently he’s started his own project . He’s candid in saying that he’s still figuring out his style, though his aim is to “tiptoe the very fine line between creative artistry, balance and elegance . ”

Nk'Mip Cellars, North America's first Aboriginal-owned and operated winery, is located on the traditional territory of the Osoyoos Indian Band. Below, Justin Hall is a winemaker and member of the Osoyoos Indian Band.

Toor notes that much of the fieldwork is done by labourers from abroad, though he hopes to see more BIPOC in winemaking and lab roles —“predominantly white jobs”— rather than in the fields tending to vines .

Toor is looking to grow the industry beyond his own needs, knowing that diversification will bring innovation . Volunteering with Vinica, a mentorship program that focuses on diversifying the wine industry for people facing systemic barriers, he hopes to guide and share his experiences in the B .C . wine industry in hopes of diversifying the community and raising the bar .

Further south, around Osoyoos Lake, lies Nk’Mip Cellars, North America’s first Aboriginal-owned and operated winery . Endowed with awards throughout the years, the winery is located on the traditional territory of the Osoyoos Indian Band (OIB) . Nk’Mip’s winemaking focus has been on land stewardship, reflected in its vineland and the effort put into each bottle .

“Businesses thrive here because of our

sets you back as a business .”

location, the richness of our land, and because we want to do business with the world,” states the OIB’s mandate online . “We strengthen our future by protecting our past .” Historically, agriculture in the area focused on tobacco and cattle . Currently, national acclaim for their wines is a driving force for their community and regional tourism .

In Ontario, low-intervention wine- and cider-maker Tariq Ahmed (full disclosure: my boss) says his main concern is regardchallenge; Revel Cider and iBi Wines were built on a lean business model .

“Historically, people of colour have not had the same access to capital .” Ahmed explains further: “Our highest-margin revyou don’t have access to capital, you can’t own land and then you’re stuck selling in the lowest margin revenue streams, which

Despite the lean business model and small staff, Ahmed has promised a donation of $500 with every new bottle release in order to help combat racism and other issues affecting BIPOC . On Revel’s Instagram page, he states: “Systemic racism is not something that disappears next week . If we can afford this as a tiny operation eking out an existence, I know that a lot of the rest of you can, too . ”

Barriers are being torn down and doors are opening for wine professionals of colour across Canada, thanks to the efforts of the small group of driven professionals

Rajen Toor, winemaker at Ursa Major in B.C.’s South Okanagan, has grown up surrounded by vines. His family has been farming the Black Sage Bench region for the past 25 years. One of his wines is pictured below.

ing land ownership . Access to capital is a

enue stream is attached to having land . If using their influence to make change .

Wine- and cider-maker Tariq Ahmed says his main concern about wine's inherent white privilege is land ownership.

“We are seeing it in vineyards and restaurants across South Africa,” says JosephLemoyne . “If the most racialized country in Africa can do it, so can we . ”

Ursa Major, Revel Cider and iBi wines can be ordered online from www .ursamajorwinery .com and www .revelcider .ca respectively . Nk’Mip can often be found in the LCBO’s Vintages section . Visit www . vinica .ca for more information on Vinica .

Tristan Bragaglia-Murdock is co-founder of Jabberwocky Bar in Ottawa . He currently works on the production floor and cellar of Revel Cider and iBi Wines in Guelph .