5 minute read

At the Frontier of Hope: Brister Freeman

BY ALIDA ORZECHOWSKI

When you hear the words ‘Walden Pond’ you probably think of Henry David Thoreau and his cabin in the woods. If you’ve been here, you might also think of the many hiking trails and sandy little coves surrounding the gin-clear water of the pond where tens of thousands of people enjoy swimming and walking each season.

What you might not think about is the community of formerly enslaved people who once lived near Walden. Not because it was the beautiful, tranquil scene we flock to today, but because it was considered an infertile, out of the way, undesirable piece of land to Concord’s white population.

As Elise Lemire writes in her excellent book Black Walden, as many as fifteen formerly enslaved people ‘made a life for themselves in Walden Woods, enough that Henry David Thoreau could describe their Codman Estate community as a “small village.”’

One of the members of that community was Brister Freeman, who, for a short time, would become Concord’s second formerly enslaved black landowner. (The first was John Jack, he of the famed epitaph whose grave you can visit in Old Hill burial ground.) Freeman’s story is just one of many that make up the African American experience in Concord, but it is an encompassing place to start.

Before we embark on our journey with Brister it should be noted that although there is a fair amount written on slavery in New England, nearly all of it is from the white perspective. First person accounts of what it was like to live as an enslaved person in pre-Revolutionary Massachusetts are almost nonexistent. What little we know of their personal lives comes almost exclusively through the dispassionate and callous lens of slave owners, tax records, and offhand observations like Henry’s description in Walden that are but footnotes in an otherwise white world.

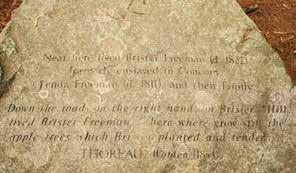

Marker at Brister Hill

©baycolonymedia.com

What has been pieced together, thanks to the herculean efforts of authors like Lemire, is that Brister was probably the fifth and last child of Lincoln and Zilpah. At the time of their youngest son’s birth in 1744, the married couple was enslaved by Chambers Russell, a justice of the peace and wealthy landowner of what is now the Codman Estate on the Lincoln, MA side of Walden Pond.

While there’s no hard evidence, such as a bill of sale, of Brister being subsequently taken from his family and given to Timothy Wesson, it’s circumstantially logical that this was the same Brister that Wesson then gifted his ambitious son-in-law, Dr. John Cuming, and daughter Abigail on the occasion of their wedding in 1753.

Codman Estate

©baycolonymedia.com

Brister was nine years old when he was enslaved by the prominent Cuming family in Concord, and he would remain so for the next 25 years. That John Cuming’s gravestone would later describe him with words like pious, compassionate, and generous, simply underscores the persistent but false notion of ‘good’ slave owners, as no amount of benevolence - short of liberating Brister - should be seen as anything less than the monstrous act it was.

Fortunately for Massachussetts, the American War for Independence would lead to the relatively early abolition of slavery here, though it was more an unintended consequence rather than any kind of collective moral stand on the part of white colonists. African Americans across the Bay Colony deftly took advantage of the political and social upheaval and began gaining their freedom well before the new law was passed in 1783.

Brister served three enlistments in the war and by the last one in 1779, had begun referring to himself as Brister Freeman, a powerful declaration of his own independence. Six years later he would gain the additionally coveted title of landowner. By pooling his limited financial resources with another freed black veteran, Charlestown Edes, the men were able to purchase just over an acre near Walden Pond, across from what is today the high school. They split the occupancy of a two-room house, where Brister dwelt with his wife Fenda and three children, in the heart of the “small village” within Walden Woods.

Other residents of this remarkable village include Brister’s older sister Zilpah (abandoned by the Russell family) who eked out a living for herself via spinning wheel in a tiny shanty where the town allowed her to stay as a squatter. Cato Ingraham (formerly enslaved to Captain Duncan Ingraham) and his wife Phyllis (formerly enslaved to the Bliss-Emerson family) would also become neighbors. Brister’s son Amos would marry Love Oliver and thus connect the Freemans to another black community in Concord out by Great Meadows, the Robbins-Garrisons.

Cuming House

©baycolonymedia.com

This burgeoning society was at the very frontier of hope, and Brister Freeman was determined to keep breaking new ground.

The cards were overwhelmingly stacked against all of Concord’s black population, however. Neither the town, nor the country as a whole, was yet able to accept the full citizenship of the very people who helped build it, and, in most cases, would work actively against that realization of equality.

A combination of poverty, sickness, and malnutrition would see the last descendant of Brister Freeman die in 1822, thus ending the family’s presence here. The Robbins- Garrison line would continue near Great Meadows a bit longer. Ellen Garrison, born in what is now the Robbins House, would go on to be recognized as ‘Concord’s Rosa Parks’ for her courageous and very public stand against segregation in 1866. She devoted her life to activism and education for the newly freed black people across America.

History is often mistakenly thought of as a static thing, permanent and fixed. But if “all history is biography” as Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, then uncovering the lives of Concord’s African Americans should necessarily change what we think we know about our collective past. If we’re open to what their stories have to teach us, then perhaps we can allow our ever-evolving and dynamic history to guide us towards a more honest and justice-driven future.

Alida Vienna Orzechowski has served as the Director of Marketing and historic interpreter at The Old Manse, Board Member of Thoreau Farm Trust, and a member of the Concord Historical Collaborative. She is the founder of Concord Tour Company and is a licensed Concord guide.

If you’d like to know more about the history of Concord’s African Americans, visitwww.robbinshouse.org for a comprehensive list of books and interpretive resources.

We also highly recommend “Black Walden: Slavery and Its Aftermath in Concord, Massachusetts” by Elise Lemire, which can be purchased locally at The Concord Bookshop and Barrow Bookstore.

Additionally, Concord Tour Company has created an in-depth and interactive walking tour, “Black History Matters: Uncovering the African American Experience and the Myth of Benevolence in Concord, Massachusetts.” Tours can be booked by visiting www.concordtourcompany.com. Five percent of all tour proceeds will be donated in support of The Robbins House, the only museum dedicated to Concord’s African American history.